As Wüster et al. [1] point out, identifying the snakes responsible for bites is crucial information for improving our understanding of the epidemiology of snakebites and the clinical symptoms of each venomous species. However, snake identification is a complex process that only a few specialists can perform, and even they disagree when identifying specimens, especially from poor-quality photos. Furthermore, since photographers are usually neither herpetologists nor naturalists, their photos often fail to capture the distinguishing features necessary for identification, which vary by species.

In fact, only about one-third of victims bring in the snake responsible for the bite, and identification is not usually performed at primary care facilities, which treat nearly all patients [2]. Therefore, clinical examination is the main guide for healthcare personnel, as biological tests are not always feasible. Antivenoms are usually polyvalent, providing coverage for as many venomous species as possible in the region where they are used.

We are grateful to Wüster et al. for drawing attention to this issue, enabling us to overcome long-standing challenges associated with identifying incomplete, damaged or poorly photographed specimens.

Wüster et al. reported errors in identifying some of the specimens responsible for envenomation, which are shown in our article [3].

The first issue relates to the Naja species shown in Figure 7 of the article [3]. The bite occurred in Tokombéré, a town located in Cameroon’s Far North Region close to the Nigerian border. We attributed this to N. haje, but they believe it to be N. nigricollis.

As one of the authors of this commentary rightly points out, “N. haje can usually be distinguished from other African cobras by examination of the headscales (Broadley, 1968) [4]. The eye is usually separated from the upper lip scales by a row of small scales, but in some specimens, including the snake which bit Case 1, the third upper lip scale may enter the orbit causing confusion with the forest cobra (N. melanoleuca) and N. nigricollis (Anderson, 1898)” [4]. The specimen shown in Figure 7 [3] does not have any upper labial plates in contact with the eye, which is characteristic of N. haje. To our knowledge, one upper labial always enters the eye in N. nigricollis. Regardless of how the specimen in Figure 7 [3] is identified, abnormalities can be seen in the scales surrounding the eye. According to Roman, in N. haje, “the eye is separated from the labials by suboculars that are sometimes very small in 38 specimens; in one specimen, a labial on each side touches the eye; and in two other specimens, the labial touches the eye on only one side. There is one preocular in 29 specimens, two on one side of the head in six specimens and two preoculars in the remaining three specimens” [5]. In other words, out of 41 N. haje specimens, Roman identified 9–12 with an anomaly in the scales bordering the eye, accounting for at least 22% of the total. However, Roman found no such abnormalities in the scales bordering the eye, nor any subocular scales on either side of the head, in 100 N. nigricollis specimens. Additionally, two subocular scales were present without any contact with the anterior temporal scales, distinguishing them from postoculars. Therefore, it is more likely that the pre-ocular scale fuses with a subocular scale in N. haje than that two subocular scales are present in N. nigricollis. Furthermore, N. haje has one anterior temporal scale, like our specimen, whereas N. nigricollis has two [6]. It is possible that the large scale under the anterior temporal is not an upper labial, as we thought, but a second anterior temporal. However, the fact that it is difficult to count the upper labials, and, in particular, to visualize the fourth and fifth ones, makes it impossible to settle the question. Table 1 summarizes the data from the cephalic scales. We have therefore identified this specimen as N. haje.

Table 1.

Summary of the characteristics of the cephalic scales of N. haje, N. nigricollis, and N. melanoleuca.

We agree that the clinical presentation is more consistent with envenomation by N. nigricollis. However, this does not rule out N. haje being the cause. As Warrell et al. reported [4], envenomation by N. haje can present as cytotoxic envenomation. Neurotoxic effects are often present but may be absent. For instance, Wüster et al. did not consider N. melanoleuca bites in our study: of the five cases of envenomation, three patients presented symptoms of cytotoxicity without neurotoxic signs. As N. melanoleuca bites are more frequent than N. haje bites, this could explain why this type of exception has been noted for N. melanoleuca envenomation, but not for N. haje envenomation.

Wüster et al. then refute the identification of the specimen in Figure 8 [3], which they attribute to N. nigricollis rather than N. katiensis. The bite also occurred in Tokombéré.

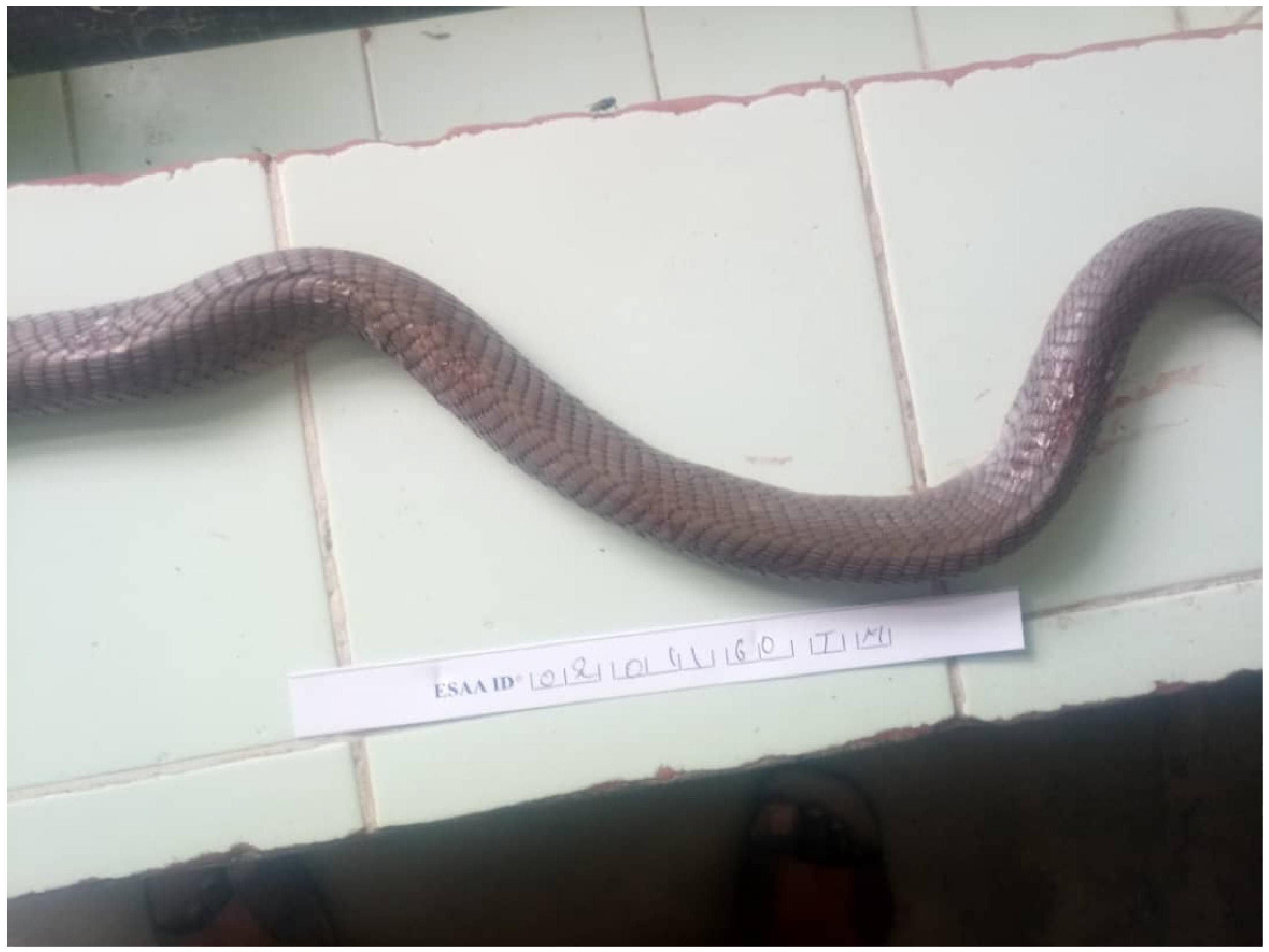

The coloration of N. nigricollis differs from that of N. katiensis [5,6]. In N. nigricollis, the belly is dark with more or less light transverse bands and the first ventral scales are black, which is not the case with our specimen. In contrast, the belly of N. katiensis is light with one or two dark bands at the neck, and the first ventral scales are light. In addition, the dorsal scales “have a dark border near the edge” [5]. Photos of the belly and back of the same specimen reveal that (a) the belly is entirely light in color (Figure 1), except for the dark band on the neck shown in the photo in the article, and (b) the dorsal scales are edged with a dark border (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Ventral side of the specimen.

Figure 2.

Dorsal side of the specimen.

Finally, Wüster et al. dispute the identification of the three specimens shown in Figure 11 [3].

Figure 11A [3] shows D. jamesoni, not D. viridis. This is not an identification error, but rather a slip of the pen. We never mentioned D. viridis elsewhere in this article, as it is absent from Cameroon, but we always referred to D. jamesoni. Unfortunately, we did not spot this error, and neither did the reviewers.

Figure 11B [3] shows a species of the genus Causus. This identification is possible, though not certain, given the poor condition of the specimen and its worn skin.

We agree that the specimen in Figure 11C [3] is Bitis arietans. We apologize for this gross misidentification.

We acknowledge—and apologize for—one misidentification (Figure 11C [3]). The identifications by Wüster et al. in Figures 7, 8, and 11B [3] are disputable. The identification in Figure 11A [3] was a slip of the pen.

However, it is incorrect to extrapolate the error rate of the 12 snakes shown in photos in the paper to the 151 snakes identified in this study. This study is ancillary to a clinical study that aimed to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of an antivenom under real-life conditions. Identifying the snakes responsible for the bites was not the initial intention. It was also not planned to preserve the specimens. In most cases, identification is possible based on photographs. However, identifying the snake may be uncertain or controversial in a few circumstances when only poor-quality photos are available.

In general, snakebites in sub-Saharan Africa have a significant impact on morbidity and mortality. Healthcare workers in decentralized areas are on the front line. Progress in developing appropriate management strategies in this context has been modest in recent years. Therefore, open dialogue and patient-centered solutions should be prioritized to effectively address this issue.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-P.C. and F.T.; methodology, J.-P.C.; validation, J.-P.C. and F.T.; resources, J.-P.C.; data curation, J.-P.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-P.C.; writing—review and editing, J.-P.C. and F.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wüster, W.; Warrell, D.A.; Williams, D.J. On the Importance of Correct Snake Identification. Comment on Chippaux et al. Snakebites in Cameroon by Species Whose Effects Are Poorly Described. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2024, 9, 300. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2026, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolon, I.; Durso, A.M.; Botero Mesa, S.; Ray, N.; Alcoba, G.; Chappuis, F.; Ruiz de Castañeda, R. Identifying the snake: First scoping review on practices of communities and healthcare providers confronted with snakebite across the world. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chippaux, J.-P.; Madec, Y.; Amta, P.; Ntone, R.; Noël, G.; Clauteaux, P.; Boum, Y., II; Nkwescheu, A.S.; Taieb, F. Snakebites in Cameroon by Species Whose Effects Are Poorly Described. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2024, 9, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warrell, D.A.; Barnes, H.J.; Piburn, M.F. Neurotoxic effects of bites by the Egyptian cobra (Naja haje) in Nigeria. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1976, 70, 78–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roman, B. Les Naja de Haute-Volta. Rev. Zool Bot. Afr. 1969, 79, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Trape, J.F. Guide Des Serpents d’Afrique Occidentale, Centrale et d’Afrique du Nord; IRD: Marseille, France, 2023; ISBN 978-2-997099-2974-5. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.