On the Importance of Correct Snake Identification. Comment on Chippaux et al. Snakebites in Cameroon by Species Whose Effects Are Poorly Described. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2024, 9, 300

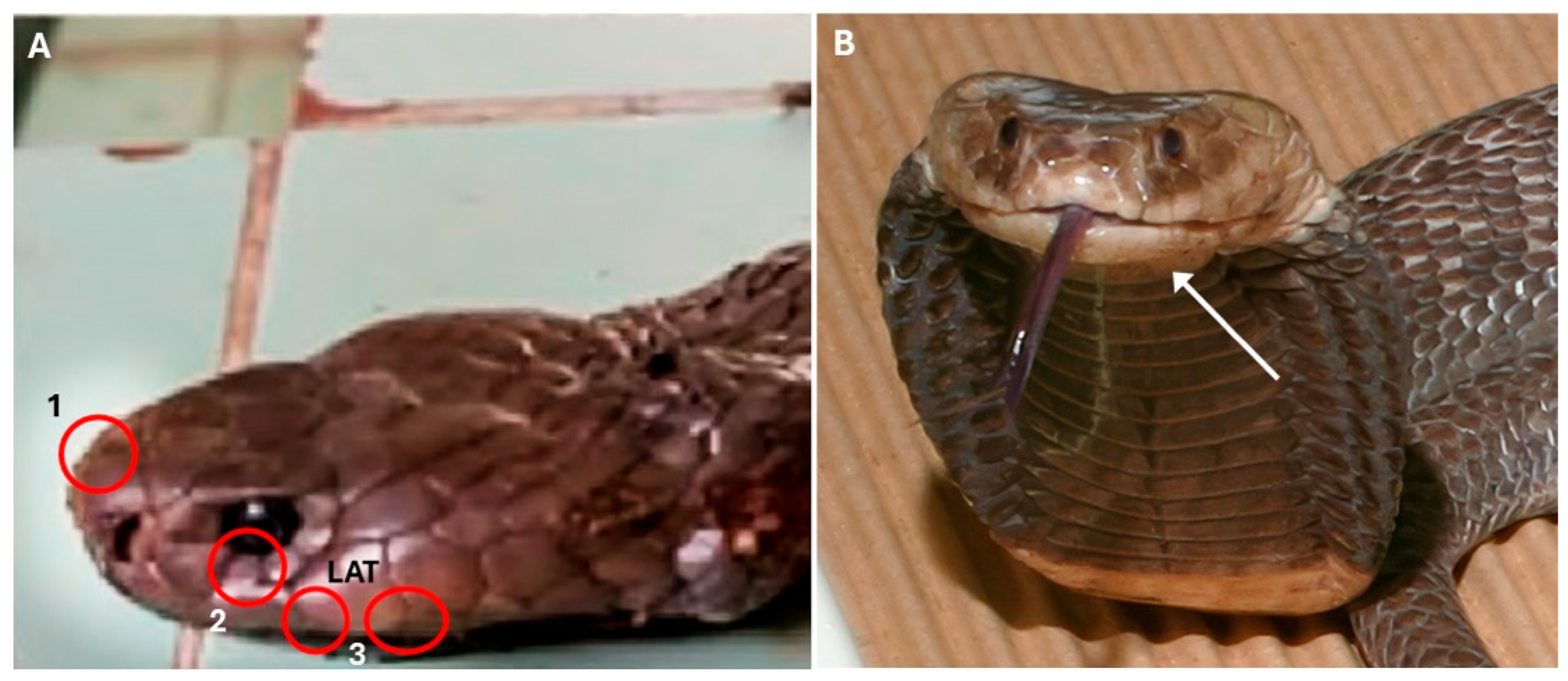

- Figure 7 [1]: the snake shown is unquestionably a Naja nigricollis, not a N. haje. An enhanced version of the Figure is shown in our Figure 1A. Its identity is evident from the clearly visible second (lower) preocular, the contact between the 3rd supralabial and the eye (Figure 1A—the scale contacting the eye is clearly contiguous with the 3rd supralabial, although there may be a small surface irregularity conveying an impression of partial separation), and the small penultimate supralabial, all characters that distinguish African spitting cobras (subgenus Afronaja) from the Naja haje group (subgenus Uraeus) [2,3,4]. The temporal and supralabial scalation is more challenging to discern. Superficial examination gives the impression of a single anterior temporal, bordered below by a high supralabial that is also in broad contact with the postoculars. However, closer inspection suggests that the lower supralabial edges are curled inwards towards the mouth, and that what looks like a high supralabial is in fact a lower temporal, bordered below by the typical low 4th and 5th supralabials of Afronaja spp. that are, in this photo, largely hidden by the overhanging temporal region (Figure 1A). A corner of the low 4th supralabial is just about visible between the posterior edge of the third supralabial, the anterior edge of the lower anterior temporal and the edge of the mouth. Additionally, the illustrated specimen has approximately square internasals in broad contact with each other and a low rostral scale, whereas in N. haje, the rostral is high and separates the anterior inner edges of the internasals from each other. This identification is also supported by the clinical syndrome of envenoming that consisted of massive swelling of the entire bitten arm with large blisters on the dorsum of the hand, in the absence of any neurotoxic signs. The patient died 30 h after the bite, possibly from hypovolaemic shock as there is no mention of fluid replacement being given. This clinical picture is consistent with N. nigricollis but not with N. haje envenoming, which entails significant neurotoxicity that can sometimes be accompanied by local swelling and minor blistering, but not cytotoxicity without neurotoxic signs [5,6].

- Figure 8 [1]: the snake shown is almost certainly a Naja nigricollis. In N. katiensis, the underside of the head and the first 8–15 ventral scales are uniformly light, followed by 1–2 narrow dark bands, followed by an immaculate light belly, whereas the overwhelmingly dark throat and chin and the numerous black markings on otherwise light ventral scales in the snake in Figure 8 are indicative of N. nigricollis. In many western and central African N. nigricollis, the head and throat are entirely black, but in some, including in northern Cameroon (Figure 1B), the underside of the head and the first few ventrals can be light. The width of the first dark ventral band is an additional distinguishing character: in 13 published [3,4,8,9,10,11,12] or Internet photographs of N. katiensis, the width of the first band ranged from 4–8 ventrals compared to the 11 ventrals in Chippaux et al.’s Figure 8. In addition, N. katiensis has more numerous dorsal scale rows (typically 25) compared to N. nigricollis (typically 21) [4,13,14,15], resulting in a smoother, shinier appearance than N. nigricollis. This is clearly not the case in the snake depicted in Figure 8. The dark edges of the dorsal scales mentioned by Roman [14] for N. katiensis are not visible in any widely available published photo [3,4,8,10,11,12,16]. Finally, the frontal scale of the specimen in Figure 8 is approximately as broad as long, corresponding to the typical condition in N. nigricollis, whereas in N. katiensis, it is typically much longer than broad [3,14]. Unfortunately, details of the temporal and infralabial scalation of the specimen are not discernible due to the poor resolution of the photo in the published article. The largely light belly of the specimen in Figure 8 is somewhat unusual for N. nigricollis. However, given the dark rectangular markings along the belly and the numerous features listed above, we argue confidently that this specimen is N. nigricollis.

- Figure 11 [1]: there are multiple misidentifications in this Figure.

- ○

- ○

- Figure 11B [1] depicts a Causus sp., certainly not Bitis arietans; the specimen displays none of the typical pattern elements of B. arietans, such as the series of light chevrons along the back. The narrow, angular dark marks suggest C. resimus, which is not normally green in this part of its distribution [4].

- ○

- Figure 11C [1] depicts Bitis arietans, not Echis romani, as it lacks the characteristic vertebral blotches and lateral ocelli of the latter, but displays typical pattern elements of B. arietans.

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chippaux, J.-P.; Madec, Y.; Amta, P.; Ntone, R.; Noël, G.; Clauteaux, P.; Boum, Y., II; Nkwescheu, A.S.; Taieb, F. Snakebites in Cameroon by Species Whose Effects Are Poorly Described. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2024, 9, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallach, V.; Wüster, W.; Broadley, D.G. In Praise of Subgenera: Taxonomic Status of Cobras of the Genus Naja Laurenti (Serpentes: Elapidae). Zootaxa 2009, 2236, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chippaux, J.-P.; Jackson, K. Snakes of Central and Western Africa; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Trape, J.-F. Guide des Serpents d’Afrique Occidentale, Centrale et d’Afrique du Nord; IRD Editions: Marseille, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Warrell, D.A.; Greenwood, B.M.; Davidson, N.M.; Ormerod, L.D.; Prentice, C.R.M. Necrosis, Haemorrhage and Complement Depletion Following Bites by the Spitting Cobra (Naja nigricollis). QJM Int. J. Med. 1976, 45, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrell, D.A.; Barnes, H.J.; Piburn, M.F. Neurotoxic Effects of Bites by the Egyptian Cobra (Naja Haje) in Nigeria. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1976, 70, 78–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wüster, W.; Crookes, S.; Ineich, I.; Mané, Y.; Pook, C.E.; Trape, J.-F.; Broadley, D.G. The Phylogeny of Cobras Inferred from Mitochondrial DNA Sequences: Evolution of Venom Spitting and the Phylogeography of the African Spitting Cobras (Serpentes: Elapidae: Naja nigricollis Complex). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2007, 45, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spawls, S.; Branch, B. The Dangerous Snakes of Africa; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Warrell, D.A.; Ormerod, L.D. Snake Venom Ophthalmia and Blindness Caused by the Spitting Cobra (Naja nigricollis) in Nigeria. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1976, 25, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobiey, M.; Vogel, G. (Eds.) Venomous Snakes of Africa/Giftschlangen Afrikas; Terralog; Chimaira: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Trape, J.-F.; Mané, Y. Guide des Serpents d’Afrique Occidentale: Savane et Désert; IRD Éd: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chirio, L.; LeBreton, M. Atlas des Reptiles du Cameroun; Patrimoines Naturels; Publications Scientifiques du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle IRD: Paris, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wüster, W.; Broadley, D.G. Get an Eyeful of This: A New Species of Giant Spitting Cobra from Eastern and North-Eastern Africa (Squamata: Serpentes: Elapidae: Naja). Zootaxa 2007, 1532, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, B. Les Naja de Haute-Volta. Rev. Zool. Bot. Afr. 1969, 74, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Roman, B. Vipéridés et Elapidés de Haute-Volta. Notes Doc. Voltaïques 1973, 6, 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Roman, B. Serpents de Haute-Volta; Centre Nationale de Recherche en Sciences et Technologie (CNRST): Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Durso, A.M.; Bolon, I.; Kleinhesselink, A.R.; Mondardini, M.R.; Fernandez-Marquez, J.L.; Gutsche-Jones, F.; Gwilliams, C.; Tanner, M.; Smith, C.E.; Wüster, W.; et al. Crowdsourcing Snake Identification with Online Communities of Professional Herpetologists and Avocational Snake Enthusiasts. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2021, 8, 201273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolon, I.; Durso, A.M.; Botero Mesa, S.; Ray, N.; Alcoba, G.; Chappuis, F.; Ruiz De Castañeda, R. Identifying the Snake: First Scoping Review on Practices of Communities and Healthcare Providers Confronted with Snakebite across the World. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wüster, W.; Warrell, D.A.; Williams, D.J. On the Importance of Correct Snake Identification. Comment on Chippaux et al. Snakebites in Cameroon by Species Whose Effects Are Poorly Described. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2024, 9, 300. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2026, 11, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed11010031

Wüster W, Warrell DA, Williams DJ. On the Importance of Correct Snake Identification. Comment on Chippaux et al. Snakebites in Cameroon by Species Whose Effects Are Poorly Described. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2024, 9, 300. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2026; 11(1):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed11010031

Chicago/Turabian StyleWüster, Wolfgang, David A. Warrell, and David J. Williams. 2026. "On the Importance of Correct Snake Identification. Comment on Chippaux et al. Snakebites in Cameroon by Species Whose Effects Are Poorly Described. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2024, 9, 300" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 11, no. 1: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed11010031

APA StyleWüster, W., Warrell, D. A., & Williams, D. J. (2026). On the Importance of Correct Snake Identification. Comment on Chippaux et al. Snakebites in Cameroon by Species Whose Effects Are Poorly Described. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2024, 9, 300. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 11(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed11010031