Abstract

e-Games have become increasingly important in supporting the development of children with language delays. However, most existing educational games were not designed using usability guidelines tailored to the specific needs of this group. While various general and game-specific guidelines exist, they often have limitations. Some are too broad, others only address limited features of e-Games, and many fail to consider needs relevant to children with speech and language challenges. Therefore, this paper introduced a new collection of usability guidelines, called eGLD (e-Game for Language Delay), specifically designed for evaluating and improving educational games for children with language delays. The guidelines were created based on Quinones et al.’s methodology, which involves seven stages from the exploratory phase to the refining phase. eGLD consists of 19 guidelines and 131 checklist items that are user-friendly and applicable, addressing diverse features of e-Games for treating language delay in children. To conduct the first validation of eGLD, an experiment was carried out on two popular e-Games, “MITA” and “Speech Blubs”, by comparing the usability issues identified using eGLD with those identified by Nielsen and GUESS (Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale) guidelines. The experiment revealed that eGLD detected a greater number of usability issues, including critical ones, demonstrating its potential effectiveness in assessing and enhancing the usability of e-Games for children with language delay. Based on this validation, the guidelines were refined, and a second round of validation is planned to further ensure their reliability and applicability.

1. Introduction

The ability of a child to speak is one of the most crucial stages of language development in early childhood. Language development is considered a very important aspect of a child’s life and one of the best indicators of educational achievement [1]. A “delay in language” describes the proper sequence of speech and language development that occurs at a slower rate than expected [2]. Children with language delays experience delays in the speaking process when compared to other children in their age; children who experience language delays will exhibit difficulties with letter-arrangement completeness, articulation, sound, and fluency [3]. There are factors that cause language delay in children, such as psychological factors, which include meeting the child’s needs without verbal interactions or the child living in a quiet environment without much communication with others. Other causes of language delay could be related to intrinsic factors such as autism, hearing loss, or mental disability [4]. Language delays among children are a serious problem that requires immediate attention. It is one of the most common causes of developmental disorders in children [5]. A delay in treating this problem may cause the child to become frustrated, withdraw from social relationships, and isolate. It may also have a negative impact on the child’s academic achievements and quality of life [4]. When a child reaches the age of one year and cannot pronounce their first words, or their speech is unclear, or they lag behind their peers, fears arise among parents and those around him, who begin searching for the appropriate evaluations and treatments to address the problem [6]. Traditional treatment methods that are followed in therapeutic sessions to improve communication skills in children include group language intervention, individual speech and language therapy, language intervention implemented by parents, and main intervention techniques such as observation, waiting, listening, paraphrasing, focused stimulation, and visual input use [7]. However, the numerous treatment sessions and the extended duration of therapy can make the child feel bored and as if they are not having fun. Therefore, the use of modern technology to treat linguistic delay in children leads to an ideal and satisfactory result [8]. Nowadays, technical solutions and modern techniques are used in the form of e-Games or applications created specifically to treat language delay in children [4]. The therapeutic approach through e-Games has garnered great interest from healthcare practitioners and has proven its effectiveness when integrating e-Games and therapeutic goals [8], which has a positive impact on learning through motivation and engagement development [9]. Therefore, researchers confirm that combining therapeutic content with e-Games leads to the creation of engaging and stimulating therapeutic environments, and that e-Games have great potential in stimulating the cognitive capacities of various target groups. e-Games also find excellent acceptance among people with special needs because they feel safe and comfortable exploring the virtual world and receiving prompt feedback, free from concerns about social exclusion [10].

Despite the rise in recent research on the utilization of therapeutic e-Games to stimulate language abilities, there is a gap in modern research in the field of e-Games. This gap is related to the fact that existing e-Games used to treat linguistically delayed children are not based on any treatment or design guidelines [10], which prevents these e-Games from achieving the intended therapeutic outcomes effectively.

We hypothesize that the proposed eGLD guidelines will detect a higher number of and more critical usability issues than existing guidelines such as Nielsen and GUESS, particularly when applied to therapeutic e-Games for children with language delay. This study aims to close this gap by outlining a comprehensive set of guidelines for e-Games, which will aid future designers and developers in creating e-Games specifically for children with language delays, titled eGLD, and will also support evaluating existing e-Games; eGLD guidelines meet the following criteria:

- Simple to follow and understand for designers, developers, and evaluators.

- Suitable for all users, especially children with linguistic delays.

- Specialized in designing and evaluating e-Games that support language development and incorporate diverse interactive game and therapy features to enhance learning and engagement.

This study has two primary objectives. The initial objective is to create eGLD using Quinones et al.’s methodology [11]. The second objective is to assess the effectiveness of eGLD as part of the first stage of validation, according to the Quinones methodology, by comparing it with the well-known Nielsen and GUESS guidelines. This comparison was carried out in Saudi Arabia using two popular e-Games designed for language development in children: “MITA” and “Speech Blubs”.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides background information and a literature review on language delay, usability guidelines, and the methodology for developing new heuristics. Section 3 describes the development of eGLD. Section 4 presents the results of developing and validating the proposed guidelines. Section 5 discusses the key findings, while Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines future work.

2. Background Information and Related Work

Children often begin to pronounce their first words at the age of 12 months and then start combining words to form sentences before the age of two years [12]. These periods are considered sensitive for language development in children, and those who fail to achieve linguistic development in their early years are vulnerable to problems in receptive and expressive language during school age and beyond [12]. Children who have a language delay suffer from a delay in the speaking process compared to healthy children of the same age [3]. The affected children will show limitations in voice, speech, letter order, and fluency. Language delay can also be described by the children’s inability to express or speak clearly, limited vocabulary, difficulty engaging in conversations with parents, and difficulties in understanding spoken words [3].

Two basic factors affect Speech and language abilities: intrinsic factors and psychosocial factors. Intrinsic factors include innate conditions such as the physiology of the organs involved in language and speech skills, including cognitive impairment, hearing loss, autism, selective mutation, cerebral palsy, and abnormalities in the speech organs. Psychosocial factors can take the form of stimuli surrounding the child, such as a quiet environment, twins, bilingualism, incorrect teaching methods, and television viewing patterns [5].

2.1. Usability and Guidelines

Usability is considered one of the important areas in human–computer interaction (HCI), and it is an essential feature because it is necessary and important for the system to be well designed and highly usable [8,13]. In 2016, the ISO updated the standard 9241-11, which focuses on ergonomics in human–system interactions. This standard defines usability as how well a system, product, or service helps specific users achieve their goals effectively, efficiently, and satisfactorily within a given context [14]. This standard was reviewed and confirmed in 2023 [15].

Usability can be improved and tested by following specific guidelines. These guidelines are helpful because they can be used early in the design process to evaluate and discover problems before the app is released [16]. Nielsen’s principles are some of the first and most well-known usability guidelines. They were created by Nielsen and Molich in 1990, and these guidelines are widely applicable to most user interfaces [17]. However, traditional usability rules might not assess unique features for specific domains. Because of this, some experts have created new usability rules by updating Nielsen’s guidelines or adding new ones to better fit specific needs [11]. Moreover, M. Muhanna et al. [18] proposed that Nielsen’s criteria are insufficient for evaluating games—especially Arabic mobile games—because they are general and do not cover all aspects of the game. Therefore, we need specific criteria for e-Games to ensure that important aspects are not overlooked when evaluating game usability and enjoyment.

Usability guidelines often come with a checklist that helps in assessing applications tailored to specific domains [11]. The checklist items can add value to categorization and evaluation by identifying unique game characteristics and guiding the design process. They provide a structured approach for developers to ensure all essential features are met, define requirements, and support more effective communication and discussion among game developers about game design. This shared language fosters collaboration across teams and across the various disciplines involved in game development [19].

Several studies have used different guidelines to design and evaluate e-Games. Nielsen’s principles [20] comprise ten usability guidelines, which are:

- Visibility of system status.

- Similarity between the system and the real world.

- User control and freedom.

- Consistency and standards.

- Error prevention.

- Recognition rather than recall.

- Flexibility and efficiency of use.

- Aesthetic and minimalist design.

- Help users recognize and recover from errors.

- Help and documentation.

J. Phan et al. [21] developed and validated the GUESS, with 9 guidelines and 55 checklist items for gauging video-game satisfaction. Overall, the GUESS was shown to have satisfactory convergent and discriminant validity, as well as good content validity and internal consistency. Additionally, the GUESS was created and verified using evaluations of more than 450 distinct video-game titles from a variety of well-known genres (such as action adventure and role-playing). The GUESS comprises nine usability guidelines, which are:

- Usability/playability.

- Narratives.

- Play engrossment.

- Enjoyment.

- Creative freedom.

- Audio aesthetics.

- Personal gratification.

- Social connectivity.

- Visual aesthetics.

The results showed that the GUESS can be applied to video-game players with different levels of experience (e.g., novice, professional, expert) who play different kinds of games. To generalize the GUESS to further gaming genres, more investigation is also required. In particular, the majority of the games assessed in studies were commercial games created just for entertainment purposes. Furthermore, most of these games were enjoyed by players rather than disliked [21,22]. This means that GUESS might not cover all the important usability points when it comes to serious or therapeutic e-Games. These types of e-Games have different goals and need to be looked at in a different way. So, using GUESS alone might not be enough for e-Games made for learning or therapy.

2.2. Developing New Usability Guidelines

Guidelines are the set of important concepts and rules for user interface (UI) design. These guidelines are based on the human psyche [10]. To create a new set of usability guidelines, specific methodologies must be followed that are systematic and formal such as Quinones [23]. Quinones’ methodology is divided into seven primary phases, which include:

- Exploratory stage: gathering information from previous research about the application domain for which a new set of heuristics will be created, the application’s features and attributes.

- Descriptive Stage: highlighting the most important information collected from the previous stage to formulate the main concepts of the research.

- Correlational stage: identify specific features of the application that require evaluation using usability heuristics.

- Selection stage: determine the process used for each guideline. Using the existing heuristics collected, you have the option to retain, modify, or remove the heuristics, or develop new guidelines.

- Specification stage: formally define the new set of proposed guidelines using a standard template.

- Validation stage: validation of the guideline set through multiple experiments.

- Refinement stage: after obtaining feedback from the previous phase, the new set of guidelines is improved.

The benefit of using Quinones et al.’s method is that it gives a clear and organized way to explain each guideline. Quinones et al.’s method includes details such as the guideline’s ID, priority, name, definition, application features, where it can be used, examples, benefits, checklists, and usability features. Additionally, you can repeat and improve different parts as many times as needed to make the guidelines better or to improve how experiments are carried out during testing [23].

Validating Usability Guidelines

In Quinones et al.’s [23] methodology, there are three ways to verify the methodology.

- Guideline evaluation: to check the proposed guidelines against traditional or specialized guidelines in terms of the number of usability issues detected (as recommended by Quinones).

- Expert judgment: use a questionnaire that assesses the perceptions and opinions of evaluators and experts of the proposed usability guidelines (to obtain additional feedback).

- User testing: to obtain user opinions about a set of usability guidelines (to receive additional feedback).

This study applied the first type of validation by comparing eGLD with existing guidelines to assess its effectiveness. The findings are presented below. We plan to use the remaining two methods, expert judgment and user testing, in future work to further enhance the guidelines.

3. Materials and Methods

This section outlines the process for developing and creating the eGLD guidelines, as well as the procedures for validating the results from the first stage.

3.1. Developing eGLD

The literature review identified several usability guidelines that are used to assess e-Games and applications. Some of these guidelines, such as Nielsen’s usability heuristics [20], are universally applicable and used in a variety of fields, including e-Games. Others, like GUESS [21], are designed especially to evaluate user experience and satisfaction in video games, emphasizing important elements like fun, involvement, and creative freedom. As discussed in Section 2, each of these sources has limits even though they all offer insightful information about usability and user experience.

Inspired by these earlier researches, we created a comprehensive set of usability guidelines known as eGLD that are specifically designed to evaluate and guide the development of e-Games for children with language delays. Nielsen’s heuristics, GUESS, and the results of pertinent e-Game experiments were among the well-established studies from which the eGLD guidelines and checklist items were derived. In order to guarantee a structured and systematic development process, we used the formal approach suggested by Quiñones et al. [23], which was previously discussed in Section 2.

3.1.1. Stage 1: Exploratory Stage

In this stage, a systematic literature review was carried out to obtain relevant information pertinent to the design and evaluation of e-Games for children with language delays. The review aimed to identify critical gaming features, usability attributes, and design guidelines that promote effective learning for children with language delays. To perform the review, we searched for the following sets of keywords:

- For features: (“e-Games” OR “mobile game”) AND “features”;

- For attributes: (“e-Games” OR “mobile game”) AND “usability attributes”;

- Guidelines and recommendations: (“e-Games” OR “mobile game”) AND (“usability guidelines” OR “usability principles”).

We looked for relevant material published between 2017 and 2024 in several academic databases, including IEEE, Springer Link, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar.

The inclusion criteria for choosing studies are as follows: (1) focus on e-Games; (2) detailed descriptions of relevant characteristics, attributes, guidelines, or suggestions; (4) publicly available full-text studies; and (5) English-language articles. The exclusion criteria were studies (1) without complete text, (2) articles unrelated to e-Games, (3) papers lacking an extensive explanation of essential design features, and (4) broad survey papers with no specific conclusions.

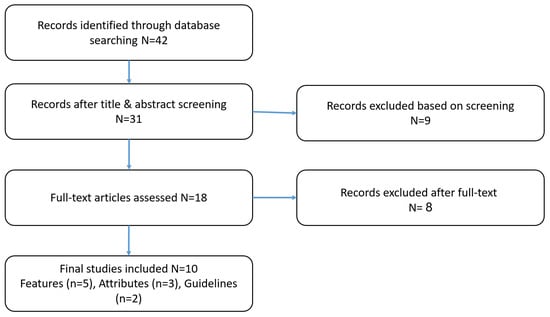

As shown in Figure 1, a total of 42 records were identified through database searching. After title and abstract screening, 31 records were retained, while 9 were excluded based on the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Then, 18 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, and 8 were excluded according to the same criteria. In the end, 10 studies were included in the final analysis: 5 studies focused on features, 3 on usability attributes, and 2 on design guidelines.

Figure 1.

A flowchart of the systematic literature review selection for eGLD.

The information gathered from this stage is displayed below.

- Features: Features refer to the unique functions or capabilities of an application that distinguish it from other types of apps. These features are particularly relevant for design e-Games for children with language delay or disabilities [10,24,25,26,27], and will be examined in the next stage.

- Usability attributes: Attributes are the criteria used to evaluate the quality of mobile applications during usability testing, using specific usability metrics. Which include:

- –

- Nielsen’s attributes: learnability, efficiency, memorability, errors and satisfaction [28].

- –

- ISO attributes: effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction) [29].

- –

- PACMAD (People At the Centre of Mobile Application Development) attributes: combine elements from both ISO and Nielsen usability models, while also adding the cognitive load aspect. These attributes include effectiveness, efficiency, learnability, memorability, errors, satisfaction, and cognitive load [30].

- Usability guidelines: These serve as the basic principles, and include:

- –

- Nielsen’s usability heuristics [20].

- –

- GUESS guidelines for the evaluation of e-Games [21].

3.1.2. Stage 2: Descriptive Stage

- For features: We collected all the features from [10,24,25,26,27]. We added four language delay-specific features, combining them with the existing ones to create a comprehensive list of 28 integrated features, as shown below:

- Identification with the game [10].

- Interface design [10].

- Layout [10].

- Demonstrations [10].

- Reward/encouragement [10,25,26,27].

- Performance feedback and guidance [10,24,25,26,27].

- Personalization [10].

- Adaptive games and challenges [10,26,27].

- Social interaction [10].

- Mobility [10].

- Time management/restriction [10].

- Repetition and rehearsal of skills [10].

- Motivation and engagement [10,24].

- Motor skill [10].

- Cognitive development [10].

- Speech recognition [24].

- Emotional attachment [24].

- Animation and engaging graphics [25].

- Background music and sound effects [25].

- Points [26,27].

- Story or theme [26].

- Show progress [26].

- Provides badges for achievements [26].

- Provides clear goals [26].

- Gradual language complexity.

- Review of previous words.

- Play-based therapy.

- Syntax and sentence formation.

- Usability attributes: We focused exclusively on attributes defined by PACMAD attributes [30]. Below are the definitions of each attribute [30].

- –

- Effectiveness: the capacity to accomplish the intended results.

- –

- Efficiency: minimizing wasted time, effort, money, and resources.

- –

- Satisfaction: meeting the user’s expectations and making them feel fulfilled.

- –

- Learnability: how quickly and easily users can figure out how to use the app.

- –

- Memorability: how well users can remember how to use the app after not using it for a while.

- –

- Errors: reducing the user’s error rate when using the program.

- –

- Cognitive load: the capacity to operate a mobile application while carrying out daily tasks.

- For usability guidelines: We divided the relevant research into two categories: main guidelines, which will serve as the basic principles for the next stages, and checklist items, which will customize the main guidelines more particularly to e-Games for children with language delay.

- –

- Main guidelines: we selected all Nielsen’s usability heuristics [20], and all GUESS guidelines [22].

- –

- Checklist items: we selected all the checklists for designing e-Games for children with language delays [10].

3.1.3. Stage 3: Correlational Stage

Table 1 presents how the identified features, attributes, and key usability guidelines were aligned during this stage. This step aims to define the unique features clearly and attributes of eGLD that should be evaluated using the main set of guidelines [23]. The matching process is feature-driven, meaning we first matched attributes that can measure each feature, then chose the relevant main guidelines (from Nielsen and GUESS) labeled N and G, that relate to those attributes. The codes N1–N10 refer to Nielsen’s ten usability heuristics, and G1–G9 correspond to the GUESS game usability guidelines. Their definitions are as follows:

Table 1.

Mapping between features, attributes, and usability guidelines.

- Nielsen: N1—Visibility of system status; N2—Similarity between the system and the real world; N3—User control and freedom; N4—Consistency and standards; N5—Error prevention; N6—Recognition rather than recall; N7—Flexibility and efficiency of use; N8—Aesthetic and minimalist design; N9—Help users recognize and recover from errors; N10—Help and documentation.

- GUESS: G1—Usability/Reproduction; G2—Narratives; G3—Playing involvement; G4—Pleasure; G5—Creative freedom; G6—Audio aesthetics; G7—Personal gratification; G8—Social connectivity; G9—Visual aesthetics.

As an example, we examined the “Adaptive games and challenges” feature. The most suitable attributes and guidelines that it may be compared to:

- Attributes:

- –

- Cognitive load: to determine if the game adapts its level of difficulty to the player’s skill level, making sure it is neither too easy nor too challenging.

- –

- Satisfaction: to gauge how gratifying and pleasurable the gaming is when the difficulties are suitably distributed.

- Guidelines:

- –

- Similarity between the system and the real world (N2) in Nielsen: guarantees that the game’s complexity and substance are in line with user comprehension and real-world expectations.

- –

- Help users recognize recover from errors (N9): when players are having trouble, the game may gently adapt or provide guidance, turning challenging situations into teaching opportunities rather than frustrating ones.

- –

- Play engrossment (G7), creative freedom (G5), and playing involvement (G3) in GUESS: adaptive gameplay keeps players deeply engaged throughout the game, boosts user motivation, and enables them to make meaningful decisions.

3.1.4. Stage 4: Selection Stage

In this step, we evaluated and categorized every usability guideline found in the previous stage according to how well it addressed the unique features of e-Games designed for children with language delay. Four categories were used for classification [23]:

- Keep: since the guideline was already in accordance with the desired qualities, it was kept exactly as is.

- Adapt: to properly represent the context of e-Game usability, the checklist elements in the guideline were expanded or improved.

- Eliminate: because the guideline was redundant or irrelevant to the target domain, it was eliminated.

- Create: to assess a feature not addressed by the previous rules, a new guideline was developed.

We kept all of Nielsen’s guidelines, but we made some changes to the checklists to make them better fit e-Games, especially games that focus on learning and interaction. From the GUESS guidelines, we only kept the ones that made sense for our project. For example, we kept things like play involvement, pleasure, creative freedom, and internal gratification because they help make games more fun and engaging. But we removed others like narrative and visual aesthetics because they were either too similar to what we already had in Nielsen’s guidelines.

While working on this, we noticed that some important features like gradual language complexity and interactive feedback were not really covered by either Nielsen or GUESS. So, we created five new guidelines to focus on these important areas that help kids learn through games.

Each guideline (whether old or new) was given a priority: (1) useful, (2) important, or (3) critical—depending on how much it helps with the learning goals of the e-Game. The final results of this stage in Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 2.

Choosing guidelines from Nielsen’s.

Table 3.

Choosing guidelines from GUESS.

Table 4.

Newly created guidelines derived from literature review and key features of effective e-Games children with language delay.

3.1.5. Stage 5: Specification Stage

In this stage, a new set of eGLD guidelines was formally defined, comprising 19 usability guidelines with 130 associated checklists. These guidelines were developed through the integration of Nielsen’s and GUESS guidelines, along with an additional newly created guidelines. Furthermore, the eGLD guidelines were adapted and extended by incorporating additional checklists from one study [10] to enhance their relevance and applicability. These checklists were added to better align the main guidelines with the specific features of e-Games designed to support language development in children with language delays. Some of these features are created with therapeutic goals to help improve children’s language skills through interactive and engaging activities. Below are the 19 guidelines of eGLD, including their respective IDs and names (IDs start with eGLD, representing e-Game for Language Delay).

- eGLD1: Visibility of system status.

- eGLD2: Similarity between the system and the real world.

- eGLD3: User control and freedom.

- eGLD4: Consistent and minimalist design.

- eGLD5: Minimize and manage errors.

- eGLD6: Recognition rather than recall.

- eGLD7: Flexibility and efficiency of use.

- eGLD8: Help and documentation.

- eGLD9: Playing involvement.

- eGLD10: Pleasure.

- eGLD11: Creative freedom

- eGLD12: Audio aesthetics.

- eGLD13: Personal gratification.

- eGLD14: Social connectivity.

- eGLD15: Gradual language complexity.

- eGLD16: Interactive feedback.

- eGLD17: Play-based engagement.

- eGLD18: Words review and sentence formation.

- eGLD19: Repetition and rehearsal of skills.

3.2. Validating eGLD

Stage 6: Validation Stage

The validation stage follows the three steps proposed by Quinones et al.’s methodology [23]: (1) guideline evaluation, (2) expert judgment, and (3) user testing. In this study, we completed only the first step, which involved comparing the new eGLD guidelines with Nielsen and GUESS to assess how many usability issues were identified and how severe they were. The expert judgment and user testing steps will be conducted in future work. Below are the details of the first step.

- Experiment design

- –

- Participants: The evaluation was carried out by two of the researchers who worked on this study. The first one, Mrs. Noha Badkook, is a master’s student at the Faculty of Computing and Information Technology (FCIT) at King Abdulaziz University. She has a moderate level of experience with usability testing. The second evaluator is Dr. Duaa Sinnari, an assistant professor in FCIT at King Abdulaziz University, and she has high experience in usability testing and human–computer interaction (HCI).

- –

- Guidelines: Three different sets of guidelines were tested. The first one, eGLD, is a detailed set of 19 usability guidelines that includes 130 checklist items specifically created for apps designed to help with language delay. The second set, Nielsen’s guidelines, is a well-known group of 10 general usability guidelines aimed at improving how apps are designed and used. Lastly, GUESS includes 9 guidelines that focus on evaluating games, especially how engaging and visually appealing they are.

- –

- Applications: We chose two of the most popular games for treating language delay in children, which are “Speech Blubs” and “MITA”, to conduct the experiment. The English language was the default interface and the mobile phone used was running on the iOS system. Reasons for choosing these two apps: Both apps are easy to use, popular, and specifically designed for children’s language development. Figure 2 shows the home screen of the “Speech Blubs” game, and Figure 3 shows the home screen of the “MITA” game.

Figure 2. “Speech Blubs” home screen.

Figure 2. “Speech Blubs” home screen. Figure 3. “MITA” home screen.

Figure 3. “MITA” home screen.

- Experiment Procedure: Each evaluator started by testing the “Speech Blubs” app using the eGLD guidelines and recorded the usability issues they found. This was followed by evaluations using Nielsen’s and GUESS guidelines separately for the same app. Once the “Speech Blubs” app was evaluated, the process was repeated for the “MITA” app, following the same steps. This resulted in six evaluations in total: three for each app using the three sets of guidelines, as shown below:

- List of discovered usability issues on “Speech Blubs” using eGLD.

- List of discovered usability issues on “Speech Blubs” using Nielsen.

- List of discovered usability issues on “Speech Blubs” using GUESS.

- List of discovered usability issues on “MITA” using eGLD.

- List of discovered usability issues on “MITA” using Nielsen.

- List of discovered usability issues on “MITA” using GUESS.

After completing these evaluations, the evaluators combined their findings to create unified lists of usability issues for each app and each set of guidelines. To prioritize which issues needed attention, the evaluators used the Severity Rating Scale (SRS), which ranks problems on a scale from 0 (not a problem) to 4 (critical issue) [31] as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Severity Rating Scale (SRS).

4. Results

This section outlines the results obtained from the development and validation of the eGLD guidelines.

4.1. Results of eGLD Development

The Quinones et al. [23] template offers various elements. It is the discretion of the researcher to decide whether to use the entire template or just specific parts [32]. In our study, we chose to include the ID, priority, name, definition, related features, and checklist items for each guideline, as shown in Table 6. A detailed breakdown of each guideline in eGLD is provided in Appendix A.

Table 6.

The descriptive elements for the eGLD guidelines.

4.2. Results of the eGLD Validation

From the usability results collected during the sixth stage (validation), as outlined in Section 3, the main findings are summarized below:

4.2.1. Usability Issues Among the Three Guidelines

As shown in Table 7, eGLD discovered more usability issues (“MITA”: 96, “Speech Blubs”: 62) than Nielsen (“MITA”: 16, “Speech Blubs”: 13) and GUESS (“MITA”: 39, “Speech Blubs”: 13) across both games.

Table 7.

Numbers of usability issues in both games based on the three guidelines.

4.2.2. Severe Usability Issues Among the Three Guidelines

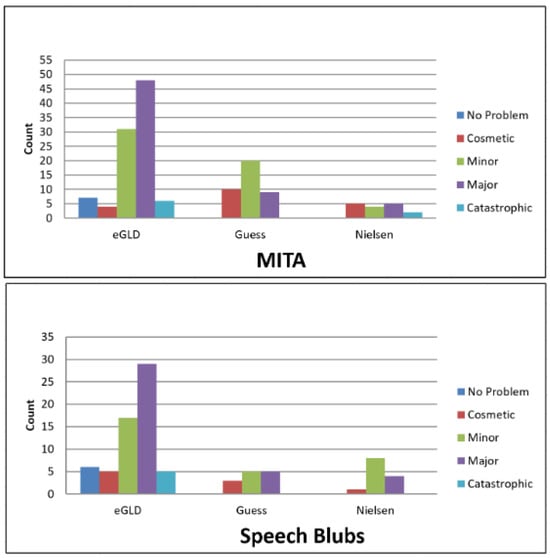

As shown in Table 8 and Figure 4, eGLD discovered more catastrophic issues (“MITA”: 6, Speech Blubs: 5) than Nielsen (“MITA”: 2, “Speech Blubs”: 0) and GUESS (“MITA”: 0, “Speech Blubs”: 0) across both games.

Table 8.

Severity of usability issues in “MITA” and “Speech Blubs” games.

Figure 4.

Severity of issues in the “MITA” and “Speech Blubs” games among the three guidelines.

The comparative results presented in Table 7 and Table 8 clearly demonstrate the superior performance of the proposed eGLD guidelines over Nielsen and GUESS. Specifically, eGLD identified a total of 158 usability issues across both games, compared to only 29 issues using Nielsen and 52 using GUESS. Moreover, eGLD detected 11 critical (catastrophic) issues, while Nielsen identified only two and GUESS none. These metrics quantitatively support the hypothesis that eGLD is more effective in capturing both the quantity and severity of usability problems, particularly those relevant to therapeutic e-Games for children with language delay.

4.2.3. Usability Issues in the eGLD Guidelines

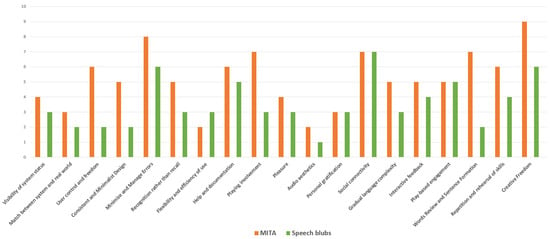

The results in Figure 5 highlight key usability issues in both games, particularly in areas like creative freedom, repetition and rehearsal of skills, and minimizing and managing errors within the “MITA” game. Users may have faced challenges in expressing creativity, reinforcing learned skills, or recovering from errors due to insufficient error management. Similarly, the “Speech Blubs” game revealed notable issues in gradual language complexity, play-based engagement, and social connectivity, suggesting that the applications may not have effectively supported language progression, interactive play, or social interaction. These findings emphasize the need for applications to balance structured learning with creativity, engagement, and social interaction, ensuring that users can progress smoothly while staying motivated.

Figure 5.

Severity of issues in the “MITA” and “Speech Blubs” games among the three guidelines.

eGLD was able to identify a greater number of usability issues, including more severe issues, across both apps. This is because eGLD includes a more comprehensive set of guidelines and checklists specifically designed for educational gaming apps, making it more effective at assessing usability challenges in this context. Based on Quinones methodology [11], we conclude that eGLD demonstrated higher effectiveness than Nielsen and GUESS.

5. Discussion

This section discussed the findings from the development and validation of the eGLD guidelines.

5.1. eGLD Development Discussion

When we compared the eGLD guidelines with those from Nielsen and GUESS, it was clear that eGLD provided a broader set of 19 guidelines, compared to 10 in Nielsen and 9 in GUESS. This is because eGLD was developed using Quinones et al.’s methodology [23], which involved adapting and merging guidelines from both Nielsen and GUESS, and introducing new ones to cover features not addressed by the original sets. Table 9 shows how each eGLD guideline corresponds to those from Nielsen and GUESS.

Table 9.

Connection between eGLD guidelines, Nielsen, and GUESS.

The eGLD guidelines include 131 checklist items, compared to 55 items in GUESS, while Nielsen’s guidelines do not include checklist items at all. This is because Nielsen’s guidelines are general, and only a few of GUESS’s checklist items focus on the general interaction and engagement aspects of e-Games, rather than addressing the specific needs of children with language delays. To fill this gap, eGLD introduced detailed and specialized checklist items designed to evaluate usability and engagement in e-Games created for children with language delays. These items focus on key features that meet the specific needs of this target group and support their language development.

This underlines the major contribution of eGLD, which provides a greater number of guidelines and checklist items than Nielsen and GUESS, as seen in Table 10.

Table 10.

Comparison of guidelines and checklist items across eGLD, GUESS, and nielsen.

5.2. eGLD Validation Discussion

The results of the first experiment to validate eGLD showed that it detected more usability issues than both Nielsen and GUESS across the two games tested. This can be attributed to eGLD’s broader and more customized set of guidelines and checklist items. Interestingly, “MITA” revealed more usability problems than “Speech Blubs” under all three guideline sets, demonstrating that eGLD, like Nielsen and GUESS, can effectively help evaluate which game provides a better user experience. Furthermore, in terms of severity, eGLD also uncovered more critical issues, which is reasonable given that its checklist items are specifically crafted for e-Games designed for children with language delays. Looking deeper into the types of problems, “MITA” had the most difficulties with guidelines such as creative freedom, repetition and rehearsal of skills, and error management. These suggest that players may have struggled to express themselves creatively, reinforce learned content, or recover from mistakes due to limited support within the game. On the other hand, “Speech Blubs” showed key issues in areas like gradual language complexity, play-based engagement, and social connectivity, indicating that the game may not have done enough to support smooth language development, interactive learning, or meaningful social interactions. Collectively, these findings emphasize the need to create e-Games that strike a balance between controlled learning and engaging, creative experiences, as well as encouraging social engagement to maintain children’s engagement and support their developmental progress.

Overall, the validation results highlight the strength of the eGLD framework in detecting a broader range and higher severity of usability issues compared to Nielsen and GUESS. This suggests that eGLD is more tailored to the context of therapeutic e-Games and better aligned with the needs of children with language delay. The presence of more critical and major issues identified by eGLD indicates that general-purpose guidelines may overlook domain-specific challenges, such as cognitive load management and play-based engagement. These insights reinforce the necessity of having a specialized set of heuristics like eGLD, and emphasize that usability evaluation in sensitive therapeutic contexts requires domain-specific depth that generic guidelines may lack.

Based on the results obtained in this study, the initial hypothesis was supported. The eGLD framework successfully identified a greater number and higher severity of usability issues compared to the Nielsen and GUESS guidelines, especially those relevant to therapeutic e-Games. This confirms that eGLD is more effective in evaluating domain-specific usability aspects for children with language delays.

One of the main challenges encountered was the delay in completing phases 2 and 3 of the validation stage. This delay occurred due to pending feedback from speech-language specialists, app developers, and HCI experts who were invited to review the proposed guidelines. Their insights are crucial to ensure the guidelines are practical, relevant, and effective for children with language delays. Pending their input, these phases have been temporarily postponed and will resume in the near future.

6. Conclusions

e-Games have increasingly become a crucial component of learning and therapy, particularly for children with language delay. It is really important that these games are easy to use and helpful. If they are confusing or hard to play, they may fail to achieve their intended therapeutic outcomes.

Therefore, this study developed eGLD, a specialized set of usability guidelines designed to support the design and evaluation of e-Games for children with language delay. It includes 19 guidelines and 131 checklist items, based on established guidelines such as Nielsen and GUESS, but further refined and tailored to meet the needs of this target group.

To verify the validity of the eGLD guidelines, we tested them on two popular games: “MITA” and “Speech Blubs”. We also used Nielsen and GUESS guidelines for comparison. The results showed that eGLD uncovered more usability issues—many of them critical—than the other guidelines. This highlights eGLD’s strength in identifying areas that could directly impact user experience, engagement, and learning outcomes for children with language delays.

Overall, eGLD helps developers, designers, and evaluators to build better, more engaging, and more effective learning e-Games for children who need additional language support. However, it is important to acknowledge some limitations of the current eGLD guidelines. The checklist items, while comprehensive, have not yet undergone large-scale testing with diverse user groups. Additionally, further iterations and broader evaluations are required to enhance the generalizability of the guidelines. In addition, one practical limitation of the current version of eGLD is its length; the large number of checklist items may make the evaluation process time-consuming and challenging to implement consistently. However, this can be addressed through iterative refinement and expert feedback, allowing future versions to be more concise and streamlined.

For future work, we will focus on further validation and enhancement of eGLD by:

- Offering design recommendations based on the usability issues found in “MITA” and “Speech Blubs” and gathering feedback from development teams.

- Involving UX experts, speech-language therapists, and HCI professionals to review the guidelines and contribute expert insights during the refining stage.

- Enhancing a selected game using the refined guidelines and conducting user testing to evaluate the impact of these improvements in real-world use.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.B., D.S. and A.A.; methodology, N.B.; validation, N.B. and D.S.; formal analysis, N.B.; resources, N.B.; writing—original draft preparation, N.B.; writing—review and editing, N.B., D.S. and A.A.; supervision, D.S. and A.A.; project administration, D.S. and A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not involve direct interaction with children or the collection of personal data from minors. Instead, the evaluation was conducted by adult expert reviewers (e.g., usability specialists and HCI experts), who were informed of the study’s objectives and voluntarily participated in the evaluation. Therefore, based on the guidelines of our institution (King Abdulaziz University), formal ethical approval was not required.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| e-Game | Electronic game |

| eGLD | e-Game for Language Delay |

| HCI | Human–computer interaction |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

This appendix shows 19 usability guidelines that were created to help design and evaluate e-Games made for children with language delay (eGLD). Each guideline is explained using a special format from Quinones et al. [23]. For every guideline, we include its ID, name, what it means, which game features it covers, and a checklist to help people evaluate how well the guideline is being used.

Table A1.

Descriptive details for eGLD1: Visibility of System Status.

Table A1.

Descriptive details for eGLD1: Visibility of System Status.

| ID | eGLD1 |

| Priority | (3) Critical |

| Name | Visibility of System Status |

| Definition | Ensure that players can always see their progress and the game status. Show feedback on what is happening in the game in real time. |

| Features | Progress indicators, feedback systems, motivational messages |

| Checklists |

|

Note: Checklist items from 1 to 6 in the following table are derived from [10].

Table A2.

Descriptive details for eGLD2: Similarity Between the System and the Real World.

Table A2.

Descriptive details for eGLD2: Similarity Between the System and the Real World.

| ID | eGLD2 |

| Priority | (2) Important |

| Name | Similarity Between the System and the Real World |

| Definition | Make the game relatable by incorporating real-world tasks, language, and visuals that players recognize. |

| Features | Real-life examples, relatable scenarios |

| Checklists |

|

Note: All checklist items in the following table are derived from [10].

Table A3.

Descriptive details for eGLD3: User Control and Freedom.

Table A3.

Descriptive details for eGLD3: User Control and Freedom.

| ID | eGLD3 |

| Name | User Control and Freedom |

| Priority | (2) Important |

| Definition | Allow players to explore the game freely, retry tasks, and fix mistakes without penalty. |

| Features | Back/Retry buttons, skip features |

| Checklists |

|

Note: All checklist items in the following table are derived from [10].

Table A4.

Descriptive details for eGLD4: Consistency and Standards.

Table A4.

Descriptive details for eGLD4: Consistency and Standards.

| ID | eGLD4 |

| Name | Consistency and Standards |

| Priority | (2) Important |

| Definition | Keep the design, instructions, and interface consistent across the game to make it easier for players to understand. |

| Features | Unified interface elements, consistent visuals |

| Checklists |

|

Note: Checklist items from 1 to 13 in the following table are derived from [10].

Table A5.

Descriptive details for eGLD5: Minimize and Manage Errors.

Table A5.

Descriptive details for eGLD5: Minimize and Manage Errors.

| ID | eGLD5 |

| Name | Minimize and Manage Errors |

| Priority | (3) Critical |

| Definition | Minimizing mistakes made by children while interacting with the game. This is achieved by providing clear instructions, validating their inputs, and guiding them through the correct steps to achieve success. |

| Features | Warnings and alerts for incorrect actions, immediate feedback to correct mistakes, guided steps for error recovery, interactive prompts to clarify actions. |

| Checklists |

|

Table A6.

Descriptive details for eGLD6: Recognition Rather than Recall.

Table A6.

Descriptive details for eGLD6: Recognition Rather than Recall.

| ID | eGLD6 |

| Name | Recognition Rather than Recall |

| Priority | (2) Important |

| Definition | Reduce the cognitive load on children by ensuring that they can recognize options or choices rather than relying on memory. |

| Features | Dropdown menus, visual prompts, consistent and familiar icons across the game |

| Checklists |

|

Table A7.

Descriptive details for eGLD7: Flexibility and Efficiency of Use.

Table A7.

Descriptive details for eGLD7: Flexibility and Efficiency of Use.

| ID | eGLD7 |

| Name | Flexibility and Efficiency of Use |

| Priority | (2) Important |

| Definition | Adapting the game to the player’s speed, preferences, and abilities. It ensures that the game remains accessible to diverse players while maintaining a smooth and efficient experience. |

| Features | Adjustable difficulty settings, progress-tracking tools |

| Checklists |

|

Note: Checklist items from 1 to 3 in the following table are derived from [10].

Table A8.

Descriptive details for eGLD8: Help and Documentation.

Table A8.

Descriptive details for eGLD8: Help and Documentation.

| ID | eGLD8 |

| Name | Help and Documentation |

| Priority | (2) Important |

| Definition | Provide helpful instructions and resources to assist players when they need guidance. |

| Features | Help menus, tutorials |

| Checklists |

|

Table A9.

Descriptive details for eGLD9: Playing Involvement.

Table A9.

Descriptive details for eGLD9: Playing Involvement.

| ID | eGLD9 |

| Name | Playing Involvement |

| Priority | (2) Important |

| Definition | Engage players by including interactive and challenging tasks to maintain their interest. |

| Features | Interactive elements, increasing difficulty levels |

| Checklists |

|

Note: Checklist items from 1 to 8 in the following table are derived from [10].

Table A10.

Descriptive details for eGLD10: Pleasure.

Table A10.

Descriptive details for eGLD10: Pleasure.

| ID | eGLD10 |

| Name | Pleasure |

| Priority | (3) Critical |

| Definition | Make the game enjoyable with rewards and activities that keep players happy and motivated. |

| Features | Rewards, animations, creative tasks |

| Checklists |

|

Table A11.

Descriptive details for eGLD11: Creative Freedom.

Table A11.

Descriptive details for eGLD11: Creative Freedom.

| ID | eGLD11 |

| Name | Creative Freedom |

| Priority | (2) Important |

| Definition | Provide players with opportunities to express creativity and make unique choices to shape their gameplay experience. |

| Features | Customizable gameplay elements, open-ended decision-making, and creative problem-solving tools. |

| Checklists |

|

Table A12.

Descriptive details for eGLD12: Audio Aesthetics.

Table A12.

Descriptive details for eGLD12: Audio Aesthetics.

| ID | eGLD12 |

| Name | Audio Aesthetics |

| Priority | (2) Important |

| Definition | Use sound and music to enhance the gaming experience without distracting players. |

| Features | Background music, sound effects |

| Checklists |

|

Table A13.

Descriptive details for eGLD13: Personal Gratification.

Table A13.

Descriptive details for eGLD13: Personal Gratification.

| ID | eGLD13 |

| Name | Personal Gratification |

| Priority | (2) Important |

| Definition | Reward players for their achievements to make them feel accomplished and motivated. |

| Features | Virtual trophies, leaderboards, progress tracking |

| Checklists |

|

Table A14.

Descriptive details for eGLD14: Social Connectivity.

Table A14.

Descriptive details for eGLD14: Social Connectivity.

| ID | eGLD14 |

| Name | Social Connectivity |

| Priority | (2) Important |

| Definition | The ability of the game to encourage meaningful social interactions among children, their peers, and family members. It promotes collaboration, communication, and relationship-building through engaging activities that require teamwork or shared experiences. |

| Features | Two-way interactive communication tools, multiplayer or cooperative modes, shared progress and achievements |

| Checklists |

|

Table A15.

Descriptive details for eGLD15: Gradual Language Complexity.

Table A15.

Descriptive details for eGLD15: Gradual Language Complexity.

| ID | eGLD15 |

| Name | Gradual Language Complexity |

| Priority | (2) Important |

| Definition | Start with simple words and phrases, gradually introducing more complex language as the player progresses. |

| Features | Increasing difficulty in language tasks |

| Checklists |

|

Table A16.

Descriptive details for eGLD16: Interactive Feedback.

Table A16.

Descriptive details for eGLD16: Interactive Feedback.

| ID | eGLD16 |

| Name | Interactive Feedback |

| Priority | (3) Critical |

| Definition | Provide real-time feedback to guide players, correct mistakes, and encourage learning. |

| Features | Hints, feedback messages, animations |

| Checklists |

|

Table A17.

Descriptive details for eGLD17: Play-Based Engagement.

Table A17.

Descriptive details for eGLD17: Play-Based Engagement.

| ID | eGLD17 |

| Name | Play-Based Therapy |

| Priority | (3) Critical |

| Definition | Incorporate fun elements like games and challenges to make learning enjoyable. |

| Features | Mini-games, animated characters |

| Checklists |

|

Table A18.

Descriptive details for eGLD18: Review of Previous Words.

Table A18.

Descriptive details for eGLD18: Review of Previous Words.

| ID | eGLD18 |

| Name | Words Review and Sentence Formation |

| Priority | (3) Critical |

| Definition | Provide players with opportunities to review and practice vocabulary they have learned previously, and help players move from learning individual words to forming complete sentences with correct syntax. |

| Features | Flashcards, practice games, reminders, sentence-building tasks, visual aids |

| Checklists |

|

Table A19.

Descriptive details for eGLD19: Repetition and Rehearsal of Skills.

Table A19.

Descriptive details for eGLD19: Repetition and Rehearsal of Skills.

| ID | eGLD19 |

| Name | Repetition and Rehearsal of Skills |

| Priority | (3) Critical |

| Definition | Allow repeated practice of key skills to help players reinforce their learning and improve memory. |

| Features | Repeated tasks, varied practice methods |

| Checklists |

|

References

- Manipuspika, Y.S.; Sudarwati, E. Phonological development of children with speech delay. RETORIKA J. Ilmu Bhs. 2019, 5, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltner, C.; Wallace, I.F.; Nowell, S.W.; Orr, C.J.; Raffa, B.; Middleton, J.C.; Vaughan, J.; Baker, C.; Chou, R.; Kahwati, L. Screening for speech and language delay and disorders in children 5 years or younger: Evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2024, 331, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirnawati, M.; Ilahiah, R. Development of Toupic (Touch Picture) Applications to Improve Expressive Language in Speech-Delayed Children. AL-ISHLAH J. Pendidik. 2023, 15, 5067–5077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warmbier, W.A.; Podgórska-Bednarz, J.; Gagat-Matuła, A.; Perenc, L. The Use of the “Talk To Me” Application in the Therapy of Speech Development Delays. Available online: https://repozytorium.ur.edu.pl/items/dec0831d-6893-40aa-af17-be743963a53f (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Akbar, M.A.; Ismail, H. Language acquisition in child who speech delay. J. Xi’an Univ. Archit. Technol. 2021, 13, 392–402. [Google Scholar]

- Diamante, R.E.J. Interactive Learning Tool Using a Neural Network Algorithm for Speech-Delayed Child. Am. J. Agric. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2022, 6, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeij, B.A.; Wiefferink, C.H.; Knoors, H.; Scholte, R.H. Effects in language development of young children with language delay during early intervention. J. Commun. Disord. 2023, 103, 106326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, N.A.A.; Wook, T.S.M.T.; Ahmad, K. A usability testing of ASAH-/for children with speech and language delay. In Proceedings of the 2017 6th International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Informatics (ICEEI), Langkawi, Malaysia, 25–27 November 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gavriushenko, M.; Porokuokka, I.; Khriyenko, O.; Kärkkäinen, T. On developing adaptive vocabulary learning game for children with an early language delay. GSTF J. Comput. 2018, 6, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Zaki, N.A.A.; Wook, T.S.M.T.; Ahmad, K. Therapeutic serious game design guidelines for stimulating cognitive abilities of children with speech and language delay. J. Inf. Commun. Technol. 2017, 16, 284–312. [Google Scholar]

- Otey, D.Q. A methodology to develop usability/user experience heuristics. In Proceedings of the XVIII International Conference on Human Computer Interaction, Cancun, Mexico, 25–27 September 2017; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, J.L.; Frost, S.J.; Mencl, W.E.; Fulbright, R.K.; Landi, N.; Grigorenko, E.; Jacobsen, L.; Pugh, K.R. Early and late talkers: School-age language, literacy and neurolinguistic differences. Brain 2010, 133, 2185–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, E.; Alsaggaf, W.; Sinnari, D. Developing Usability Guidelines for mHealth Applications (UGmHA). Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2023, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietlein, C.S.; Bock, O.L. Development of a usability scale based on the three ISO 9241-11 categories “effectiveness,”“efficacy” and “satisfaction”: A technical note. Accredit. Qual. Assur. 2019, 24, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 9241-11:2018; Ergonomics of Human-System Interaction—Part 11: Usability: Definitions and Concepts. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Reviewed and Confirmed in 2023. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/63500.html (accessed on 21 October 2014).

- Bevana, N.; Kirakowskib, J.; Maissela, J. What is usability. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on HCI, 1991; Citeseer: University Park, PA, USA, 1991; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Quiñones, D.; Rusu, C. How to develop usability heuristics: A systematic literature review. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2017, 53, 89–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhanna, M.; Masoud, A.; Qusef, A. Usability heuristics for evaluating Arabic mobile games. Int. J. Comput. Games Technol. 2022, 2022, 5641486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, L.; Feijó, B.; Leite, J.C. Features and checklists to assist in pervasive mobile game development. In Proceedings of the SBGames 2013, São Paulo, Brazil, 16–18 October 2013; pp. 90–99. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, J. Ten Usability Heuristics. 2005. Available online: http://www.nngroup.com/articles/ten-usability-heuristics (accessed on 14 September 2024).

- Phan, M.H.; Keebler, J.R.; Chaparro, B.S. The development and validation of the game user experience satisfaction scale (GUESS). Hum. Factors 2016, 58, 1217–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, E.A.O.; SILVEIRA, A.C.d.; Martins, R.X. Heuristic evaluation on usability of educational games: A systematic review. Inform. Educ. 2019, 18, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiñones, D.; Rusu, C.; Rusu, V. A methodology to develop usability/user experience heuristics. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2018, 59, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedi, S.; Bouraghi, H.; Seifpanahi, M.S.; Ghazisaeedi, M. Application of digital games for speech therapy in children: A systematic review of features and challenges. J. Healthc. Eng. 2022, 2022, 4814945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommy, C.A.; Minoi, J.L.; Sian, C.S. Pre-School Children with Speech Delay: Case Control Study Based on Guidelines for Game Designs. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Games Based Learning, Sophia Antipolis, France, 4–5 October 2018; Academic Conferences International Limited: Reading, UK, 2018; p. 713-XXI. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudi, E.; Yoo, P.Y.; Chandra, A.; Cardoso, R.; Dos Santos, C.D.; Majnemer, A.; Shikako, K. Gamification in Mobile Apps for Children with Disabilities: Scoping Review. JMIR Serious Games 2024, 12, e49029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammady, R.; Arnab, S. Serious gaming for behaviour change: A systematic review. Information 2022, 13, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J. Usability 101: Introduction to Usability (2012). 2012, Volume 9, p. 35. Available online: http://www.nngroup.com/articles/usability-101-introduction-to-usability/ (accessed on 14 September 2024).

- Iso, W. 9241-11. Ergonomic requirements for office work with visual display terminals (VDTs). Int. Organ. Stand. 1998, 45, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, R.; Flood, D.; Duce, D. Usability of mobile applications: Literature review and rationale for a new usability model. J. Interact. Sci. 2013, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Group, N.N. How to Rate the Severity of Usability Problems. Available online: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/how-to-rate-the-severity-of-usability-problems/ (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Quiñones, D.; Rusu, C. Applying a methodology to develop user eXperience heuristics. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2019, 66, 103345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).