Abstract

Culture-led urban regeneration represents a potent strategy for revitalizing post-industrial cities but necessitates navigating complex property rights fragmentation and competing stakeholder interests. This research interrogates how different institutional arrangements mediate this process, balancing economic development with cultural preservation and social sustainability. Through a comparative case study of two seminal projects in Xi’an, China—the Yisu Opera Society and the Old Food Market—this paper examines the divergent outcomes of two property rights reconfiguration strategies: land assembly and rights subdivision. Findings reveal a fundamental trade-off: while the land assembly model facilitates efficient, large-scale redevelopment and economic revitalization, it often precipitates gentrification and the erosion of socio-cultural fabric. Conversely, the rights subdivision approach, though incurring higher ongoing transaction costs, fosters more equitable and embedded regeneration by preserving community networks and authentic character. Grounded in Property Rights and Transaction Cost theories, this study con-structs an analytical framework to evaluate how governance structures, stakeholder dynamics, and contextual factors shape project outcomes. The research concludes that there is no universal solution; the optimal pathway depends on the specific heritage context and social embeddedness of a site. It contributes to urban scholarship by highlighting the critical role of flexible, hybrid governance models in managing urban complexity and offers practical policy insights for designing regeneration frameworks that can more equitably distribute the benefits of urban development.

1. Introduction

Urban regeneration is a complex socio-spatial process that mediates competing economic, cultural, and policy priorities. As established in the literature, this process fundamentally involves negotiated interactions among governmental agencies, private capital, and local communities [,]. While regeneration projects can produce significant benefits, such as improved land use efficiency and enhanced living standards [,], they also entail substantial risks, including the displacement of vulnerable populations through gentrification, the reduction in affordable housing stock [], and the potential erosion of a city’s historic fabric []. Consequently, a critical challenge for contemporary practice is to develop governance frameworks that can equitably balance economic development with cultural preservation and social sustainability [,,].

Over the past decade, culture-led regeneration has emerged as a significant catalyst for urban transformation across diverse contexts, from European port cities [] and historic urban centers [] to China’s industrial municipalities [,]. This paradigm represents a fundamental rethinking of urban development priorities, particularly in regions undergoing post-industrial transitions. Adaptive reuse has become central to this approach, which moves beyond the mere preservation of heritage building to reconceptualize revitalization as a dynamic process of cultural transmission and continuous urban evolution [,]. Rather than pursuing large-scale demolition, this strategy emphasizes incremental improvements to the existing urban fabric, recognizing the value of accumulated history and layered urban identity.

On one hand, European case studies demonstrate successful conversions of heritages into cultural districts and mixed-use developments, though these transformations frequently contribute to gentrification [,,]. On the other hand, though economic analyses indicate that adaptive reuse projects can stimulate local economies while preserving cultural memory, financial viability remains a persistent challenge []. Moreover, tensions still persist between preservation integrity and functional adaptation, particularly regarding structural modifications and energy efficiency improvements []. Facing these practical challenges, institutional analysis demonstrates that participatory approaches, particularly the substantive community engagement, are critical for enhancing social cohesion in reuse projects []. These issues underscore the complex governance dilemmas inherent in balancing economic imperatives with social justice and environmental sustainability in contemporary urban regeneration.

As the world’s largest developing economy undergoing a rapid post-industrial transition, China faces distinct challenges in its urban regeneration dynamics due to its unique fusion of public land ownership system, rapid economic development, and deep historical consciousness. Specifically, China uniquely blends two predominant regeneration narratives: (1) industrial heritage reuse and (2) historical and vernacular revival. Although preserving culture is a stated goal, the primary driver is often economic restructuring and urban branding []. Consequently, culture has been instrumentalized as a governance tool to achieve socio-economic objectives. Moreover, rapid post-industrial transformation has gradually rendered many state-owned industrial zones (danwei) obsolete, creating complex property rights structures through partial privatization and fragmented asset sales []. Therefore, China’s culture-led regeneration initiatives must simultaneously address three interrelated challenges: (1) stimulating market investment [], (2) resolving intricate ownership legacies [], and (3) preserving the embedded socio-cultural value of the danwei community [].

To address these challenges, property rights reconfiguration is a viable institutional solution, yet it receives scant scholarly attention globally. The predominant discourse has focused on its gentrification impacts [], participatory planning methodologies [], green infrastructure priorities [], and digital governance []. Within the existing literature, land assembly is identified as a common strategy. This process consolidates multiple separate parcels under fragmented ownership into a single, larger parcel controlled by one entity, typically a developer or public authority [,]. This approach can resolve fragmentation issues to create a site sufficiently large for comprehensive, master-planned redevelopment, which can incorporate public benefits such as cultural parks, infrastructure, and mixed-use buildings. However, it also risks the “holdout” problem and inheritance disputes that obscure clear ownership []. In contrast to land assembly, this paper identifies an alternative strategy focused on the subdivision of property rights, which respects the separate titles of multiple holders and facilitates the participation of all rights-holders in the planning process.

To facilitate a comprehensive comparison of these two property rights arrangements, this paper addresses two research questions: (1) Under what circumstances is each arrangement adopted in practice? (2) How does each arrangement reduce transaction costs and maximize value creation across multiple dimensions? To answer these questions, this study selects two typical culture-led regeneration projects in Xi’an and compares them across three fundamental dimensions that collectively determine project processes and outcomes: (1) the regeneration project contexts that determine the property rights arrangements; (2) the property rights configurations and their consequent impact on stakeholder roles; and (3) the project performances in cultural preservation and social sustainability. Through this comparative institutional analysis, the study makes dual contributions to contemporary urban scholarship. Theoretically, it advances the understanding of property rights reconfiguration in the unique context of post-industrial communities under a public land ownership system. Practically, it yields actionable policy insights for balancing heritage conservation with redevelopment needs through contrasting property rights arrangements.

2. Theoretical Framework and Methodology

To address the practical challenges in culture-led urban regeneration, particularly within China’s public land ownership system, this study aims to propose viable institutional solutions for managing fragmented property rights. Both the assembly and subdivision of property rights have been observed in various regeneration projects in Xi’an. Fundamentally, these two approaches aim to establish an optimal balance among three core dimensions of culture-led urban regeneration: economic viability, social equity, and cultural preservation. To compare the application conditions of these two institutional choices and their multifaceted impacts, this paper integrates Property Rights Theory and Transaction Cost Theory into the traditional Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) framework.

2.1. Theoretical Framework

2.1.1. Comparative Institutional Analysis Framework

Culture-led regeneration possesses a dual nature, functioning as both a private asset and a public good. This duality makes it a compelling case for the comprehensive examination of property rights arrangements, particularly within complex institutional settings []. Grounded in Property Rights Theory [], our research systematically analyzes the interactions between ownership, usage, and disposition rights in urban renewal. According to Alchian, a property right can be defined as a socially enforced mechanism for governing economic resources []. In urban regeneration, land ownership can further be regarded as a “bundle of rights,” which includes the rights of disposition, use, profit, and transfer. Based on this framework, this paper aims to analyze how specific property arrangements influence stakeholders’ actions and create multiple values [,].

When faced with two institutional options in urban regeneration, how should the most appropriate one be selected? Transaction Cost Economics (TCE) provides a viable criterion, as it uses transaction costs to assess the process efficiency of various institutional arrangements [,,]. Specifically, transaction costs—which encompass search, negotiation, and enforcement expenses—are determined by key transaction attributes: asset specificity, uncertainty, and frequency []. Furthermore, the level of transaction costs determines the extent of rent dissipation, which in turn influences project performance, including resource utilization efficiency and wealth distribution outcomes []. Transaction Cost Economics (TCE) provides a valuable analytical framework for evaluating governance structures, though its application to public sector contexts presents unique challenges. While Williamson’s foundational work established robust theoretical frameworks for private sector governance, scholars such as Ruiter [] have sought to adapt these principles to public institutions by addressing critical issues. These include the methodological constraints of applying TCE to public institutions, the influential role of legal frameworks and regulatory regimes, and the challenges of matching governance structures to specific transactions. Urban regeneration represents a distinct institutional challenge for conventional urban governance, as it involves navigating both the property rights problems typical of the private sector and the administrative regulations inherent to the public sector. Consequently, controlling transaction costs in urban regeneration requires detailed institutional solutions and innovations.

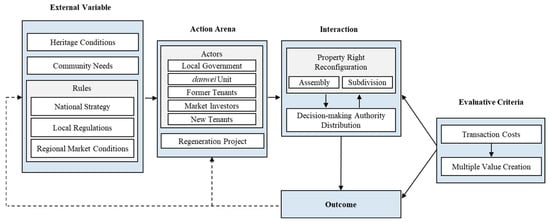

Applying these theoretical foundations to Ostrom’s (1990) IAD framework [], this paper models culture-led regeneration as a dynamic bargaining process centered on property rights reconfiguration. This process operates through three interconnected institutional dimensions: (1) project contexts determine property rights arrangements; (2) various types of property rights reconfiguration determine the distribution of decision-making authority among stakeholders; and (3) these institutional arrangements collectively determine multifaceted project outcomes. More specifically, within the national urban regeneration strategy, the bargaining dynamics are mediated by four key contextual factors: local regulatory environments, regional market conditions, industrial heritage conditions, and community needs. These factors collectively determine how rights reconfiguration achieves four primary objectives: transaction cost minimization, optimal utilization of existing development space, rational profit distribution among stakeholders, and balanced economic–cultural value creation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Institutional analysis framework grounded in property right theory.

Figure 1 directly structured our empirical investigation by providing a diagnostic lens to analyze the two cases. Specifically, we applied this framework by treating each case as a distinct institutional arrangement and asking a specific set of questions: (1) How did the external variables determine the stakeholders and the property right reconfiguration strategy in urban regeneration projects? (2) What were the primary transaction costs generated by this reconfiguration? And, (3) how did this rights-and-costs structure ultimately determine the project outcomes in terms of value creation (economic/cultural) and distribution (equity/efficiency)? By systematically comparing the Yisu and Old Food Market cases through this lens, we move beyond description to explain why their pathways diverged, thus directly linking specific property rights choices to tangible socio-economic outcomes. The complexity of these interactions suggests the need for further investigation into adaptive governance models capable of upholding equity and sustainability principles amidst dynamic urban regeneration practices.

Three key applications demonstrate the framework’s explanatory power in urban regeneration studies: (1) its capacity to address urban complexity through property rights titling [], (2) its relevance to public space planning [], and (3) its demonstrated impacts on transaction cost reduction and land use efficiency []. Chinese case studies further validate the framework’s practical utility, showing how various property rights arrangements can simultaneously address socio-economic and preservation objectives []. Thus, the framework’s principal theoretical contribution lies in its conceptualization of the resulting property right arrangements as an institutional equilibrium that reconciles competing interests while addressing feasibility, participation, and sustainability requirements.

2.1.2. Complexity in China’s Culture-Led Regeneration Practice

China’s urban–rural dual land system is a fundamental characteristic of its socialist market economy, establishing distinct governance regimes for state-owned urban land and collectively owned rural land. As the manager and sole supplier of urban construction land, local government has a fundamental economic incentive to improve the utilization efficiency of urban land resources, a role that defines its entrepreneurial character in urban development []. Consequently, in China’s urban regeneration, local government plays a more central role than in other countries. When leading regeneration projects, land assembly is the most common strategy adopted by local governments, due to its inherent advantages in land titling and planning.

Currently, two national strategies significantly influence China’s urban regeneration practices: cultivated land protection strategy and “micro-regeneration” strategy. On one hand, pressure to protect cultivated land has driven China toward a more intensive urbanization path over the past two decades, making the improved utilization efficiency of existing construction land crucial for supporting continued urbanization []. On the other hand, when promoting comprehensive urban renewal projects, China’s central government has recently advocated for a “micro-regeneration” strategy to replace the earlier model of “large-scale demolition and construction [].” This approach aims to improve living environments and preserve urban memory through small-scale, localized transformations of existing urban spaces. Under this strategy, China faces practical challenges in areas such as funding and project sustainability, long-term community governance and improvement, and balancing modernization with historical heritage preservation [,].

Moreover, two contextual factors render urban regeneration in China more complex than in other countries. The first is the nation’s tremendous heritage resources—encompassing both cultural and industrial heritage—and their deep embeddedness within local communities. China’s approach to urban heritage preservation has evolved from a focus on monumental architecture to a more holistic model that integrates history, culture, and modern urban life. Consequently, the preservation of both cultural and industrial heritage has become a rapidly growing field in urban China, representing an evolving effort to manage layered histories, particularly amid rapid post-industrial transformation. In conserving historic districts or traditional urban landscapes, there is a growing emphasis on the adaptive reuse of heritage buildings. However, as heritage fulfills multiple uses and carries conflicting meanings simultaneously, it is intrinsically dissonant []. The social constructions intertwined with urban heritage add a further layer of complexity [,].

The second factor is the ambiguous nature of state-owned land property rights, which increases transaction costs in urban land development projects []. Historically, the danwei (work unit) system served as the primary mechanism for urban land allocation during the planned economy era (1949–1978), characterized by three defining features: (1) administrative land grants to state-owned enterprises and public institutions without market transactions; (2) comprehensive land use for production, housing, and social services, creating self-contained communities; and (3) perpetual land tenure without lease payments, reflecting socialism’s non-commodified land values. Although market mechanisms now dominate urban land distribution, danwei—inherited land use patterns continue to influence contemporary urban landscapes, creating unique path dependencies for the renewal of industrial and cultural heritage sites. Amid the decay of heritage sites, danwei often rent separate parcels to small retailers or market stallholders through short-term, informal contracts. By providing livelihoods for the surrounding community—which consists mainly of former danwei employees—these tenants play a significant role in sustaining local social life. However, the property rights, interests, and roles of these stakeholders have been largely neglected in the existing literature.

Consequently, the culture-led urban regeneration during its transitional period is facing unique complexities: (1) rights transition complexity when converting informal tenancy arrangements to formal contracts while preserving cultural authenticity; (2) value distribution complexity over redevelopment premiums and tensions between social welfare and profit motives; and (3) institutional constraints including ambiguous historical usage rights, lack of standardized valuation methods for cultural assets, and policy limitations on transfer of incomplete property rights. These factors collectively create an environment characterized by unequal bargaining power and conflicting priorities among five primary stakeholder groups (Table 1). Local governments, as urban land managers, hold ultimate ownership rights while pursuing land value maximization and comprehensive urban development objectives. The original danwei units maintain historical usage rights of land and residual claims on properties, often seeking compensation for relinquished assets. Traditional tenants, typically comprising small vendors and workshops embedded in local communities, operate under informal or short-term lease arrangements that reflect the area’s cultural identity. Market investors provide essential capital and modernization expertise while seeking returns from redevelopment premiums. New commercial tenants represent modern businesses with greater rent capacity that drive economic upgrading but may disrupt existing social networks.

Table 1.

Stakeholder landscape in China’s culture-led urban regeneration projects.

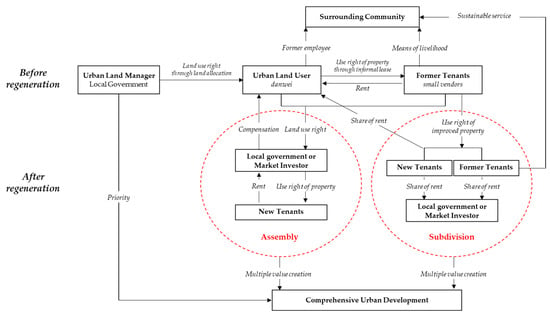

Generally speaking, cultural-led heritage regeneration generates value through three primary mechanisms. First, significant price differentials between reconstruction costs and potential leasing income create strong redevelopment incentives, particularly for market investors. Second, land values appreciate through functional upgrading and improved infrastructure. Third, the cultural capital embedded in heritage buildings can be strategically leveraged for commercial and social benefits. As this value creation process involves the interests of administrative agencies, market investors, holders of land property rights (usually the danwei units), former tenants, and new tenants, these economic dynamics must be carefully balanced. When introducing market investment into heritage sites with fragmented property rights, two distinct property rights arrangements can be theoretically identified: (1) land assembly, which consolidates land use rights in the hands of public or private investors for subsequent transfer to new tenants; and (2) rights clarification, which involves clarifying all subdivided property rights for both land users and traditional tenants, encouraging their efficient participation in project planning and implementation, and improving infrastructure conditions for all stakeholders (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Two rights transfer pathways in China’s industrial heritage regeneration.

Based on an original analytical framework, this paper aims to compare institutional arrangements, stakeholder interactions, and their impacts on value creation between two urban regeneration cases. Specifically, this framework analyzes three critical dimensions (Figure 1): (1) property rights reconfigurations to address fragmentation; (2) governance mechanisms for reducing transaction costs; and (3) project values and externalities, particularly focusing on social sustainability and cultural preservation.

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Research Area

Xi’an presents a compelling case study in culture-led urban regeneration. As one of the world’s most famous ancient capitals, the city faces the unique challenge of balancing its magnificent imperial heritage with the legacy of recent industrial past. Within Xi’an, most of the culture-led regeneration projects are located inside the City Wall. Built in the 14th century, the City Wall of Xi’an is the most complete surviving ancient city wall in China. With the length of 13.7 km, it encompasses the urban core area with formidable defensive structures. The wall system incorporates numerous well-preserved architectural elements, including monumental gates, watchtowers, and an intact moat, collectively constituting one of China’s most important medieval military heritage sites.

To protect this Ming Dynasty monument, municipal authorities have established a robust institutional framework []. First, legislative measures, including the Xi’an City Wall Protection Ordinance, provide legally enforceable safeguards—most notably, the prohibition of construction within 50 m inside the wall’s perimeter. Second, advanced technological interventions employ state-of-the-art monitoring and conservation techniques to maintain the wall’s structural integrity. Third, cultural programming initiatives enhance public engagement and appreciation of the historic monument. To compare the two property right arrangements under the same local policy context, this research selects two representative culture-led urban regeneration projects within the City Wall of Xi’an: Yisu Opera Society (Case A) and Old Food Market (Case B).

- (1)

- Case A: Yisu Opera Society

Nestled in the center of City Wall, the Yisu Opera Society stands as a prestigious cultural institution with a profound historical legacy. Originally established in 1912 under the name “Shaanxi Lingxue Society,” it holds the distinction of being China’s first arts organization dedicated to integrating the performance and formal education of Qinqiang opera, one of the oldest and most classical forms of Chinese musical theater. Its core is the historically significant Yisu Theatre, a nationally protected monument that functions not only as a performance venue but also as an educational facility.

The Yisu Opera Society was established as a theater, as well as an instrument for promoting democratic ideals and critiquing feudal practices through its new operas. Owing to its profound artistic significance and social influence, it earned the global recognition. As one of the “World’s Three Great Theatres,”, it continues to play an indispensable role in preserving and innovating Qin Opera, recognized as an Intangible Cultural Heritage by UNESCO.

The development of the Yisu Opera Society has experienced five distinct phases. From 1912 to 1916, the Society displayed a clear revolutionary spirit. By combining performances with a formal school system, the Society elevated Qin Opera from a rural tradition to a stable, theater-based art form. From 1917 to 1948, the Society entered a subsequent growth stage. During this period, it has trained more than 600 artists, which has significantly solidified its reputation. Following the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, the society entered a state-managed era. From 1949 to 1990, it has gradually transformed into a state-owned troupe that gained national fame. Since 1991, the Society began to operate under the supervision of Xi’an Performing Arts Group, and then faced the challenge to strategically balance commercial enterprise with cultural preservation. In 2020, the culture-led regeneration further transformed the surrounding area into a hub for cultural heritage as well as contemporary urban life.

- (2)

- Case B: Old Food Market

Nestled in close proximity to the ancient City Wall of Xi’an, The Old Food Market stands as a celebrated example of urban regeneration. Originally known as the Jianguomen Comprehensive Market, it now occupies the adaptively reused structures of the former Xi’an Velveteen Factory, representing a successful transformation from a state-owned industrial plant into a vibrant cultural and creative district. Its location presents unique planning challenges, as the site is separated from the historic fortification by only a narrow roadway and falls entirely within a zone where new construction is prohibited.

The evolution of this site reflects a thoughtful journey from utilitarian manufacturing to community-oriented cultural space, which can be summarized in three distinct phases. During its initial phase as a State-Owned Industrial Operation (1950s–1988), the site functioned as a typical socialist-era factory under exclusive state ownership. Its architecture was purely utilitarian, designed for the production of textiles, particularly velveteen fabrics. Following the decline of manufacturing, the site entered a period of Adaptive Reuse as an Agricultural Market (2000–2016). During this time, the underutilized factory buildings were creatively repurposed into a comprehensive public market. This approach preserved the original industrial structures while modifying the interiors, successfully reactivating the site to serve local community needs without major demolition. In its current incarnation as a Mixed-Use Cultural-Creative District (2017–Present), the market operates under a hybrid model. The ground floor retains its popular and lively market function, preserving the site’s essential social role within the community. The upper floors, developed through private investment, now host a variety of cultural and creative businesses.

Both the Yisu Opera Society and the Old Food Market represent quintessential examples of China’s culture-led urban regeneration. Collectively, they illustrate the characteristic challenges as well as innovative solutions within China’s urban transformation, which evolves from state-planned production to adaptive reuse. On one hand, both of these two cases exhibit complex property rights structures involving multiple entities (see Section 3.1). On the other hand, each case also demonstrates layered land use arrangements, where formal state ownership coexists with informal tenancy. These informal institutions have cultivated significant community value, so they pose distinct governance challenges for balancing legal frameworks with socially embedded practices. Moreover, compounded by the pressures of financial sustainability and the historical preservation, this tension, common in regeneration projects globally, is particularly acute in China due to its public ownership system as well as rapid urbanization.

Moreover, the selection of these two cases within Xi’an’s city wall provides a representative contrast in both regeneration scale and property rights strategy, offering critical insights into China’s urban transformation. First, the cases represent a major dichotomy in China’s urban regeneration approach over the past two decades. The Yisu Opera Theatre exemplifies a state-led, large-scale redevelopment model characterized by significant demolition and reconstruction. This strategy used to be widespread in China’s urban regeneration practice. Conversely, the Old Food Market exemplifies a micro-regeneration model focused on minimal demolition and adaptive reuse, which has become a predominant urban redevelopment strategy in contemporary China. Similar cases can be found in 798 Art Zone of Beijing, as well as Xiaoxihu-Laomendong District of Nanjing. Second, the cases illustrate two distinct property rights reconfiguration methods for addressing fragmentation. The Yisu Opera Theatre project employed a conventional property rights assembly strategy, consolidating highly fragmented land use rights through economic compensation and the resettlement of existing residents and danwei. In contrast, the Old Food Market employed a property rights subdivision strategy, navigating its complex, multi-owner structure through innovative legal and financial instruments.

2.2.2. Data Source and Methods

This study employed a comprehensive mixed-methods approach to examine the urban regeneration processes of two distinct cases, with a particular focus on property rights reconfiguration and governance dynamics. The research design combines the planning documents, project acceptance documents and qualitative methods to capture multifaceted dimensions of the regeneration process from diverse stakeholder perspectives.

The investigation engaged three primary participant groups representing key stakeholders in the regeneration initiatives. First, semi-structured interviews, averaging 60 min each, were conducted with seven essential stakeholders: one official from the Natural Resources and Planning Bureau of Xincheng District (relevant to Case A) in chief of planning, one official from Beilin District (Case B) responsible for project supervision and coordination, one officer from the planning institute leading Case A, manager from Xi’an Century Window Industrial Park Investment Management Co., Ltd. (the investor for Case B), two leaders representing former danwei (land users of Case A), and one community officer representing the original property rights holder (Case B). These semi-structured interviews provided critical insights into policy implementation frameworks, negotiation mechanisms, and regulatory challenges. Second, a semi-structured survey was administered to 15 current tenants in Case A, along with current and former market tenants in Case B, including small vendors, commercial operators, and cultural entrepreneurs. This survey assessed the practical impacts of property rights arrangements on business operations, spatial usage patterns, and community dynamics. Third, a separate survey was conducted with 12 citizens and 12 tourists at each site to evaluate public perceptions of the projects’ cultural significance and preservation outcomes.

Participant selection was designed to capture the full spectrum of stakeholders involved in and affected by the urban regeneration process, thereby ensuring a holistic understanding of institutional arrangements, transaction costs, and social outcomes. The selection of participants for both in-depth interviews and broader surveys was guided by stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria to incorporate a comprehensive range of stakeholder perspectives. For the in-depth investigation group (e.g., government officials, investors, property holders), inclusion was contingent upon direct decision-making authority and hands-on involvement in the regeneration projects. This criterion ensured that insights were derived from individuals occupying strategic roles in planning, financing, or implementation. Those with only peripheral or indirect involvement were excluded to maintain analytical depth and relevance. For survey respondents (e.g., tenants, residents, tourists), inclusion required an active operational presence or direct experiential connection to the sites. Commercial vendors and business operators were required to be actively managing an enterprise within the regenerated area; a further distinction was made between original and new tenants. Citizens and visitors were included based on having firsthand experience with the sites. Employees and non-operational owners were excluded to ensure that respondents could provide accurate data on economic metrics and nuanced perceptions of change. Furthermore, data triangulation was employed to corroborate qualitative findings with quantitative metrics—including changes in rent, figures on displaced residents, and business performance indicators across both cases.

The semi-structured survey employed a mixed-methods approach utilizing four primary question types to gather both quantitative and qualitative data. Closed-ended questions were used to collect measurable, comparable data on demographics, business types, rental costs, customer counts, attitudes, and future investment plans, enabling statistical analysis across stakeholder groups. To capture rich, contextual insights, open-ended questions elicited detailed responses on challenges, benefits, and changes in community character, uncovering the underlying reasons behind numerical trends.

All research data were systematically processed and analyzed using standardized protocols. Interview recordings were professionally transcribed and thematically coded to identify recurring patterns and salient themes. The research team maintained meticulous documentation of participant demographics, interaction durations, and substantive content coverage, with comprehensive methodological details provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Semi-structured interviews with various stakeholders.

The qualitative interviews provide nuanced understanding of institutional decision-making processes and governance structures (Table 3). Tenant surveys reveal grassroots impacts of property rights reallocation on business operations and community networks. Public perception data offer insights into cultural values and social acceptance of regeneration outcomes. Together, these data sources enable comprehensive analysis of the complex interplay between formal institutions and informal practices in China’s urban transformation context.

Table 3.

Semi-structured interviews with various stakeholders.

3. Results

3.1. Physical and Ownership Conditions

3.1.1. Case A: Yisu Opera Society

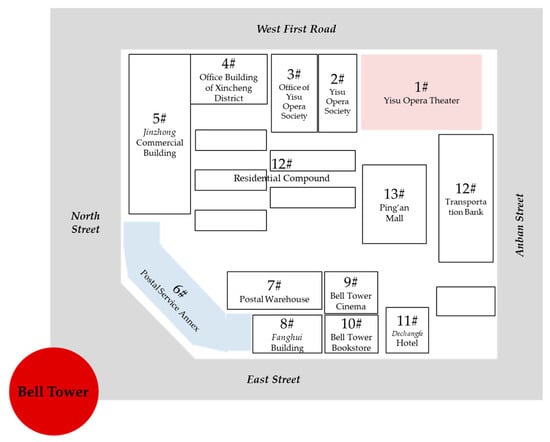

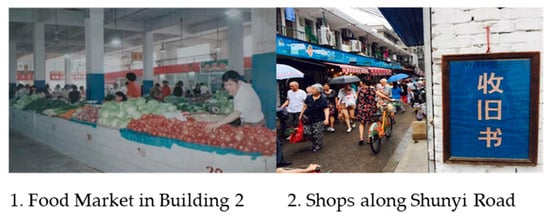

The project area is delineated by Anban Street to the east, East Street to the south, North Street to the west, and West First Road to the north, encompassing a total land area of approximately 87 mu (roughly 5.8 hectares). The block involves more than 10 institutional danwei, reflecting a complex mosaic of ownership and land use types (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Physical Configuration of Yisu Opera Society and Ownership Conditions.

At its cultural heart lies the Yisu Opera Theater, designated as a National Cultural Heritage Site in the sixth batch of national monuments in 2006. This Republican-era theater building exhibits typical architectural styles from the Ming and Qing dynasties and continues to operate as a vital venue for Qin Opera performances, offering an important case study in the evolution of modern theater architecture in China.

Adjacent to the theater is a residential compound built in the 1980s to house Yisu staff and postal staff. The compound currently suffers from a notable lack of recreational spaces, designated parking facilities, greenery, and other essential supporting infrastructure. Surrounding auxiliary buildings are primarily low-rise structures. Some feature temporary additions of poor construction quality, presenting potential safety hazards. Particularly, the office building of the Bell Tower Branch of the Xi’an postal service annex was designated as a Provincial-Level Cultural Heritage Protection Unit by Shaanxi Province in 2014.

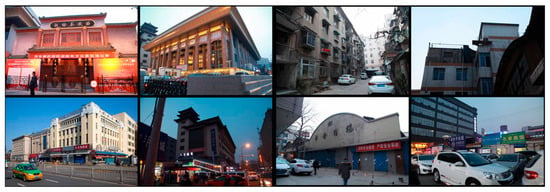

Furthermore, the Bell Tower Cinema and the Defachang Hotel also contributed to the area’s uneven urban fabric. These multi-story structures possess large volumetric footprints, and their architectural styles clash with the surrounding historical environment (Figure 4). Internally, their spaces are cramped, and their commercial offerings are limited and predominantly low-end. This condition stands in stark contrast to the area’s prime location and cultural significance.

Figure 4.

Former state of project area in Case A.

Comprehensively speaking, the community’s population historically comprised five primary categories of occupants. The first consisted of residents living in the residential compounds of the Yisu Opera Theater and the Postal Service Annex of Xi’an. The second category was consumers drawn to the area by the 38 cellphone shops concentrated in its commercial buildings. Reflecting a broader trend of urban center depression, the resident population was predominantly composed of tenants, accounting for more than 90% of the total. The third category included administrative and artistic staff working at the Yisu Opera Theater. The fourth encompassed junior students attending the nearby Xiyilu Primary School and the Children’s Palace of Xincheng District, both located approximately 600 m from the community. The final category was tourists, whose numbers had declined dramatically due to the diminishing popularity of traditional Qin Opera.

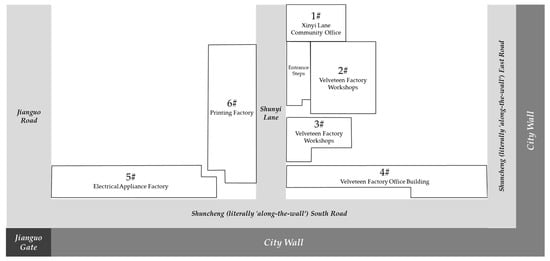

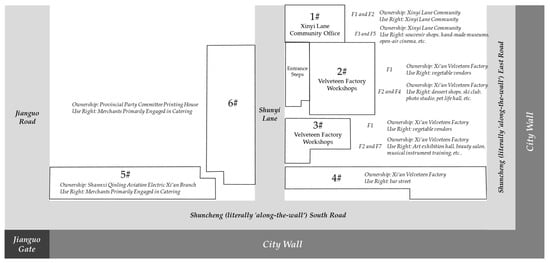

3.1.2. Case B: The Xi’an Old Food Market

The project area comprises six distinct buildings with a complex ownership history (Figure 5). The site includes Building No. 1 (Community Office Building), Building No. 2 and No. 3 (both former Velveteen Factory Workshops), Building No. 4 (Velveteen Factory Office Building), Building No. 5 (Former Electrical Appliance Factory Site), and Building No. 6 (Former Printing Factory Site). The market is located within the original industrial buildings, notably Building No. 2 (a production facility) and Building No. 3 (an administrative building). The food market was housed within the original industrial buildings of the former velveteen factory, primarily occupying Buildings No. 2 and No. 3. A significant number of its tenants are former employees of the factory who lost their jobs during China’s period of economic restructuring and state-owned enterprise reform.

Figure 5.

Physical configuration of “Old Food Market” and ownership conditions.

This physical configuration reflects the site’s layered industrial history and subsequent adaptive reuse as a marketplace. For a long time, the ground-floor market maintains a familiar, affordable, and essential gathering place for long-time residents, fostering daily social interaction and preserving the neighborhood’s character (Figure 6). The property rights situation presents significant complexity, with land use rights and building ownership divided among four principal entities. This fragmented ownership structure is further complicated by existing lease arrangements, where portions of the buildings have been sublet to market vendors for commercial operations or residential purposes. These overlapping claims create a web of legal relationships that must be carefully navigated during any redevelopment effort.

Figure 6.

Former State of Project Area. (The meaning of the non-English term in the figure: Recycle the old books).

3.2. Property Rights Arrangements and Space Restructure

The adaptive reuse of Yisu Opera Society and Old Food Market exemplifies successful organic regeneration of urban heritage, demonstrating how rational property right configuration can preserve historical character while meeting contemporary needs.

3.2.1. Case A: Yisu Opera Society

This regeneration project was formally approved by the Xi’an Development and Reform Commission and organized by Xi’an Qujiang Yisu Cultural Investment Co., Ltd. (Xi’an, Shaanxi Province, China), the project owner. As a state-owned platform enterprise controlled by the Management Committee of Qujiang New District, the project owner adopted a comprehensive strategy of preservation, renovation, and selective demolition to address the area’s disordered spatial utilization and fragmented property rights.

First, as vital carriers of urban historical memory, older buildings demand rational and adaptive reuse to prevent the loss or waste of valuable urban resources. Adhering to the original urban fabric and spatial order, the project team integrated contemporary functional requirements, project objectives, and cultural positioning to implement innovative design strategies for the exterior transformation of several key buildings, including the following: Yisu Opera Theater, Jinzhong Commercial Building, Fanghui Commercial Building, Bell Tower Bookstore, Transportation Bank Building, and Office Building of Xincheng District. The renovation work encompassed structural reinforcement, facade upgrades, interior refurbishment, and functional enhancements. Through these efforts, the project has successfully infused these historic structures with new green qualities and revitalized their social and economic vitality, ensuring their continued relevance within the modern urban environment.

Second, since the project site contains a significant number of buildings constructed in the 1980s, primarily featuring brick-concrete structures along with various temporary additions, many of them exhibit aging infrastructure that present clear safety hazards. Furthermore, the existing floor area ratio and building density fail to meet current regulatory standards. In addition, these issues are compounded by inadequate supporting facilities, incomplete urban functionalities, and substandard fire safety conditions. Indeed, for those older structures that no longer meet the demands of contemporary urban development or modern residential standards, the project plan entails the demolition of several specific buildings, including the residential compound for Yisu staff, the postal service residential compound, Ping’an Mall, Bell Tower Cinema, Defachang Hotel, and a number of auxiliary buildings. Through economic compensation and resettlement offered to affected residents and involved danwei (work units), the project owner successfully consolidated the land use rights for the inner area of the development site.

Third, following the demolition of the old buildings and internal structures, new hotels, museums, and commercial facilities have been developed within the inner area (Figure 7). These new constructions are designed to maintain architectural consistency with the original stylistic character of the district while incorporating contemporary elements and modern features. In terms of infrastructure, the project entails comprehensive reintegration and strategic planning of the entire land parcel. By leveraging existing commercial roads in the surrounding area, the design establishes multiple access points interconnected through a multi-layered circulation system. This system includes newly built pedestrian walkways, a central square, an underground pedestrian street, underground vehicle passages, underground parking facilities, an underground activity plaza, connections to underground rail transit, aerial corridors, and rooftop gardens. This integrated spatial strategy aims to achieve seamless connectivity and efficient three-dimensional utilization of all above- and below-ground spaces.

Figure 7.

New construction within the inner area.

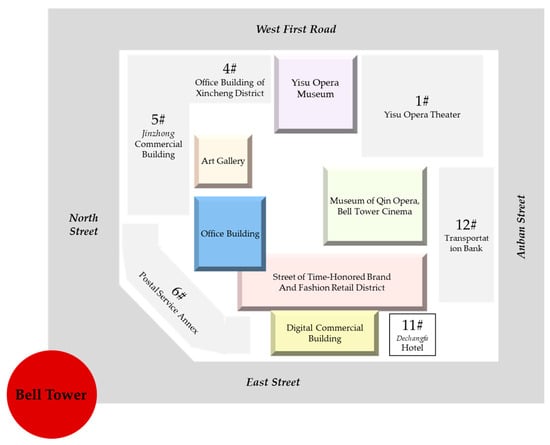

3.2.2. Case B: The Xi’an Old Food Market

In the regeneration of the Old Food Market, the design team adopted a conservation-first approach, rigorously preserving the site’s industrial character. Original facades, structural systems, and spatial layouts were retained in compliance with strict heritage standards, ensuring the historical authenticity of the buildings. Special emphasis was placed on conserving distinctive architectural features of the former velveteen factory, with all proposed modifications undergoing thorough heritage impact assessments. This methodology successfully safeguarded the site’s architectural integrity while allowing for necessary functional enhancements.

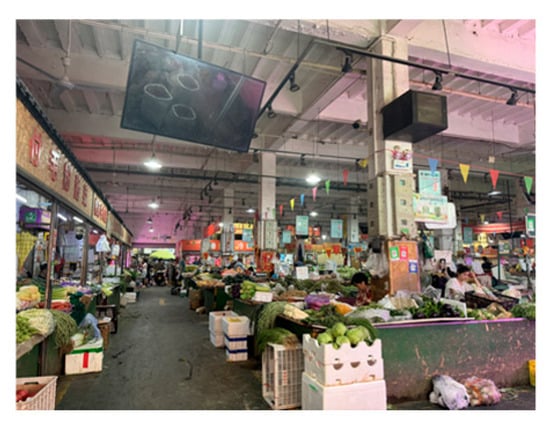

Comparing to Case A, the regeneration project of Old Food Market took more efforts in maintaining the operation of the ground floor as a bustling traditional food market. Through this way, this initiative kept the architectural characteristics of traditional industrial buildings, and maintained its vital social function as a neighborhood anchor (Figure 8). By safeguarding vendors’ livelihoods and residents’ daily routines, this regeneration project successfully preserved the community’s traditional rhythms. At the same time, this project also incorporated some comprehensive upgrades to the existing space. For instance, the old entrance steps and adjoining square were redesigned into a multi-level community stage, creating a flexible venue for both casual meetups and special events.

Figure 8.

Preserved traditional food market at the ground floor (Building 2, 3, 6).

It is notable that unlike conventional regeneration project, this initiative employed an innovative strategy focusing on subdivided property rights. Specifically, the upper floors of Building 1, 2, and 3 were adaptively reused as creative offices for design firms and tech startups. Along with street (Building 4 and Building 5), specialty dining venues were introduced to diversify culinary offerings and attract young tourists. There are also some flexible spaces preserved for cultural experience and showcase local heritage. Through this layered programming, the Old Food Market witness a vibrant coexistence of traditional and contemporary uses. Behind the space restructure, the multi-layered property rights framework is of great significance in maintaining the negotiated balance between preservation imperatives and redevelopment objectives (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Property right subdivision of Old Food Market.

3.3. Innovative Governance and Transaction Costs

3.3.1. Case A: Yisu Opera Society

The regeneration of the Yisu Opera Society was driven by a structured multi-stakeholder governance framework, strategically designed to minimize transaction costs and accelerate the transformation of the historic site into a modern cultural–commercial destination. Rather than merely focusing on cultural preservation, the project emphasized physical redevelopment, operational modernization, and commercial sustainability, requiring tight coordination between public and private actors.

Government entities played a central role in facilitating the regeneration. The Management Committee of Qujiang New District provided overarching policy direction, regulatory support, and financial incentives such as tax reductions and development grants. It supervised the institutional transition of the Yisu Opera Society from a public institution to a state-owned enterprise under the Xi’an Performing Arts Group in 2019, a reform critical to introducing market discipline and operational flexibility. Meanwhile, various departments of the Xincheng District Government handled localized administration—public security, sanitation, and urban management—and supported community outreach to smooth the transition process and align public services with the new urban development agenda.

State-owned enterprises (SOEs) played a pivotal role in project implementation. As the primary investor and developer, Xi’an Qujiang Yisu Cultural Investment Co., Ltd. (Xi’an, Shaanxi Province, China). channeled RMB 1.5 billion into the comprehensive upgrades of public infrastructure and modern commercial amenities, and then raised additional RMB 1.8 billion through the financial market. Simultaneously, the Xi’an Performing Arts Group also help promote the operational transition to enhance efficiency and market responsiveness, mainly through enhanced salary incentives, improved recruitment systems, and corporate management models.

Moreover, the interaction among these actors can also reduce the inefficiencies and negotiation costs. For instance, the government introduced differentiated lease models for commercial and cultural zones, which mitigated fragmented property rights and regulatory constraints. Flexible tenancy arrangements and revenue-sharing mechanisms also helped attract and retain vendors, thereby accelerating commercial revitalization.

3.3.2. Case B: The Xi’an Old Food Market

This project was characterized by a collaborative governance model that integrated private investment, public oversight, and community participation. First of all, the private sector (Investment Company B) served as the project leader and reconfiguration agent. It leveraged its market expertise to design and implement a phased regeneration strategy. Crucially, it established innovative partnership models to encourage a broader community participation, such as the rent reduction schemes for graduated, revenue-sharing programs with the tenants, and build-operate-transfer (BOT) agreements with land users. These models distributed risks, reduced initial capital outlays, and aligned the interests of the various property holders.

The local government, mainly including the Natural Resources and Planning Bureau of Xi’an Municipality, acted as a supervisory and coordinative body. Different from Case A, its role in this project was to enforce heritage preservation regulations, provide policy-based financial solutions, and mediate negotiations among parties. These actions can ensure the project adhered to legal frameworks, while balancing economic and conservation goals.

Traditional tenants and surrounding residents were also engaged as active participants in project planning and implementation. Specifically, the retention of tenancy rights has effectively ensured business continuity and enhanced the cultural authenticity. The community also played a role in ensuring transparency and accountability.

Transaction costs were primarily high due to fragmented property ownership and stringent regulatory constraints. Ownership was dispersed across several former industrial factories (e.g., Velveteen Factory, Printing Factory), which led to significant coordination and negotiation complexities. An initial attempt to consolidate property rights through acquisition failed due to owners demanding high prices. Regulatory barriers, specifically the prohibition against demolishing historically significant structures, further increased costs by necessitating expensive restoration instead of new construction. To mitigate these costs, the project employed flexible leasing arrangements as an alternative to full acquisition. These included temporary rent reductions, performance-linked rents, and revenue-sharing mechanisms. However, these solutions introduced secondary negotiation costs, such as addressing merchant anxieties about future rent increases and demands for lease exit clauses.

3.4. Multiple Value Creation

3.4.1. Case A: Yisu Opera Society

The regeneration of the Yisu Opera Society cultural block created multi-dimensional value and generated significant positive externalities, though it also introduced socio-economic trade-offs. In terms of value creation, the project achieved notable economic, cultural, and social outcomes. Economically, it unlocked new business opportunities and attracted multiple investments, transforming the area into a vibrant urban destination with diversified revenue streams. Prior to redevelopment, the area was centered around the Yi Su Opera Society’s Qin Opera performances, supplemented by a limited number of low-end retail stores—such as those selling hardware and groceries—and traditional snack shops catering to local residents. Following regeneration, a composite “culture + dining + retail + entertainment” model has been established: (1) Cultural experiences (approx. 30%) are provided primarily by the Yi Su Opera Theater, Qin Opera Museum, Chinese Qin Opera Art Museum, and open-air stages; (2) dining and cuisine (approx. 50%) are offered by a wide range of time-honored Xi’an restaurants, trendy eateries, cafes, and modern tea shops; (3) retail and leisure (approx. 20%) are supported by stores selling cultural and creative products, trendy toy shops, specialty gift stores, and domestic youth-focused brands. To service its 3.3 billion yuan loan, the investor raised rents from the lowest levels in the Bell Tower area to the highest in the municipality—an increase of nearly tenfold. Official statistics indicate that the opening day attracted over 200,000 visitors. On regular weekdays, customer flow remains stable, while on weekends and holidays, daily foot traffic consistently exceeds 100,000.

Culturally, it blended traditional Qin Opera performances with modern cultural offerings—such as museums, exhibition halls, and creative retail—effectively bridging heritage and contemporary appeal. Moreover, this project also established a dedicated zone which integrates the traditional art with some contemporary art formats, such as comedy clubs and live music. Through this integration, this area can attract younger demographics to contact Qin Opera and strengthen the identity of this antient city.

Socially, nearly all interviewed tenants and residents confirmed that the regeneration project has substantially upgraded public infrastructure, a development expected to attract tourism and stimulate commerce for the broader district’s benefit. The enhanced district now fosters greater public interaction and serves as a civic showcase, offering new spaces for leisure and social activities. However, these outcomes are accompanied by significant social costs. For instance, over 67% of respondents argued that rising commercial rents and consumer prices have reduced affordability for original residents, thereby accelerating gentrification. One resident poignantly stated, “the only thing we can afford now are the steamed buns in Wuyi Restaurant.” More specifically, as the area increasingly caters to tourists and high-end consumers, its historical role in everyday community life has diminished. This shift has marginalized low- and middle-income locals, with 75% of interviewed residents reporting they visit the area less frequently now than during its initial opening. Furthermore, nearly all tenants believe tourist footfall has decreased dramatically, prompting some tenants in the underground commercial street to attempt terminating their leases. Moreover, an over-reliance on premium services risks cultural homogenization, which further undermines authentic local participation and raises concerns regarding long-term social sustainability.

3.4.2. Case B: The Xi’an Old Food Market

Based on a socially conscious strategy, the regeneration project of Old Food Market has successfully transformed a declining industrial area into a vibrant community hub with commercial appeal.

Economically, through tiered leasing models, professional management, and entrepreneurial support for vendors, this project diversified its revenue streams beyond basic stall rentals. Specifically, the area forms a unique blend of “everyday market atmosphere and artistic trendiness.” This is achieved through several key features. First, the original wet market function is retained on the first floor and in peripheral areas, preserving the local lively vibe. Second, new additions have been introduced on the rooftop, in street-front shops, and in nearby buildings, comprising the following: (1) boutique dining (approx. 40%), including trendy cafes, pubs, Western restaurants, and specialty eateries; (2) creative studios (approx. 30%), such as independent designer brands, vintage clothing stores, florists, handicraft studios, and galleries; and (3) cultural spaces (approx. 20%), including rooftop art zones, exhibition areas, stand-up comedy venues, and co-working spaces.

Moreover, the strategic cultural programming has also broadened the market’s appeal and attracted visitors across the city, such as artist-led installations and public events. Collectively, these actions optimized the space utilization, elevated the market brand, and sustained the local economy. The regeneration project has yielded two principal outcomes. First, it achieves comprehensive scenario coverage, extending from daily shopping to leisure and social activities. This has significantly increased the average dwell time of visitors from 15 to 30 min to 2–4 h. Second, a differentiated rental pricing strategy has been implemented for various business types. To ensure the continuity of essential public services, the rent increase for the wet market area remains relatively moderate. In contrast, the rents for newly introduced creative retail stores have surged, now approaching or matching those of high-quality street-front retail spaces in Xi’an, with an estimated increase in three to five times or more.

Culturally, the renovation process employed sensitive micro-regeneration techniques that carefully balanced preservation with modernization. This approach maintained the market’s historical authenticity while introducing thoughtful improvements to functionality and visitor experience. Physical interventions respected the existing architectural character, preserving the market’s familiar visual identity that held meaning for long-time patrons and area residents.

By addressing historical inequities and preserving community infrastructure, this project also delivered substantial social benefits. First of all, it provided essential services to over 100,000 residents and secured employment and pensions for approximately 700 laid-off workers. Moreover, almost all the interviewed tenants believe the regeneration project has drastically improved the physical conditions of the industrial buildings, while more than 75% of the interviewed residents stated that this project also preserved their sense of familiarity and belonging. Other positive externalities have also been generated in this project, including the enhanced public health and safety and increased local economic activity.

In summary, this project exemplifies a holistic approach to transform a struggling public asset into a sustainable and inclusive node of community life. Through the combination between economic innovation with social responsibility, this case demonstrates how strategic institutional arrangements create shared value without erasing local character.

The following matrices synthesize the core characteristics, strategies, and outcomes of the Yisu Opera Society and the Xi’an Old Food Market regeneration projects, highlighting their contrasting approaches (Table 4).

Table 4.

Governance and outcome comparison.

4. Discussion

This study acknowledges the significant influence of China’s unique land ownership system on urban regeneration mechanisms. Specifically, under the dual land system, local governments act as both urban land administrators and primary land suppliers. This arrangement enables strong centralized coordination for redevelopment, but brings a huge challenge for the participatory governance in urban transformation. In this regard, these structural characteristics highlight the need for ongoing policy innovation, in order to enhance market mechanisms and community engagement in urban redevelopment.

Our comparative analysis of the Yisu Opera Society and Old Food Market projects clarifies the critical interplay among property rights reconfiguration, transaction costs, and project outcomes. The findings demonstrate that on one hand, the decision between land assembly and rights subdivision should be made according to heritage conditions, institutional environments, and development priorities. On the other hand, the choice of institutional arrangement will profoundly shape the governance process, value creation, and socio-economic externalities.

The regeneration project of Yisu Opera Society adopted land assembly, which consolidated the fragmented parcels under a single state-owned entity. Generally speaking, this approach can facilitate large-scale redevelopment, enable comprehensive planning, reduce coordination costs, and bring economic and cultural benefits. However, these gains came at the expense of social sustainability. As the original residents and traditional tenants were displaced by rising costs, this project will gradually face the loss of community embeddedness.

In contrast, the Old Food Market employed a rights subdivision strategy, which recognizes and formalizes the informal claims of former tenants. On one hand, this approach preserved socio-cultural continuity, maintained community identity, and achieved a more equitable distribution of benefits. On the other hand, it also incurred higher ongoing negotiation costs. This divergence underscores a core trade-off between the efficiency, which is derived from centralized control, and the equity, which is achieved through participatory governance.

The comparison further reveals that the context determines the effectiveness of each strategy. Due to the strong alignment between state and capital can prioritize scalability and control, land assembly has more advantageous for monumental heritage sites, such as Yisu Opera Society in this research. Conversely, rights subdivision was more appropriate for the sites characterized by high social embeddedness and a complex informal economy, such as the Old Food Market. However, both cases highlight the necessity of hybrid governance models in urban governance, which combines top-down supports with bottom-up initiatives. In addition, flexible institutional arrangement can also help mitigate transaction costs and align competing interests, such as graduated rent schemes, revenue-sharing agreements, and phased implementation.

These cases offer valuable lessons for policymakers and planners. First, the choice of property rights strategy is determined by the nature of the heritage asset and the social fabric of the community should guide. Second, effective urban regeneration requires adaptive governance frameworks that accommodate multifaceted objectives. Third, stakeholders can manage transaction costs through innovative instruments to distribute risks and rewards, which is vital to the inclusive development.

Based on the preceding analysis, we propose a series of concrete policy recommendations for urban regeneration to mitigate the inherent trade-offs between development efficiency and socio-economic equity, thereby fostering more inclusive and sustainable outcomes. First, to ensure community interests are central to the planning process, we recommend the formalization of community participation mechanisms. Specifically, the establishment of legally mandated Binding Neighbourhood Councils for major projects would institutionalize community engagement. Second, to protect existing tenants from market pressures and prevent gentrification, municipalities must develop and enforce differentiated lease and ownership schemes. For example, creating Community Equity Funds would allow residents and vendors to acquire collective equity shares in the redeveloped project, ensuring they benefit from the value they helped create and avoiding outright displacement. Third, local governments should employ targeted fiscal and cultural incentives to align private investment with the public good. For instance, issuing Cultural Subsidy Vouchers would enable residents to support traditional cultural performances and legacy businesses directly. This provides a fiscal tool to counter cultural homogenization and ensure the economic viability of authentic practices. Finally, to address the high transaction costs associated with fragmented ownership, public agencies should promote innovative financial instruments. Flexible acquisition models, for example, can allow multiple owners to voluntarily consolidate parcels for unified redevelopment in exchange for a share of future profits or space.

Situating these cases within a global context underscores that sustainable regeneration universally requires innovative hybrid governance models. The Yisu case, achieved through land assembly and substantial government investment, created a monumental cultural space but triggered gentrification and social displacement. This outcome echoes the limitations of entrepreneurial models seen in Europe [,]. Conversely, the Old Food Market’s strategy of rights subdivision and its use of community-focused instruments—such as affordability covenants and equity funds—preserved socio-economic continuity. This approach aligns with socially conscious strategies in Latin America and Europe []. Ultimately, effective models must strategically blend state capacity with community agency. By drawing on international best practices like Community Land Trusts and participatory budgeting, cities can better navigate property rights complexities to achieve outcomes that are economically vibrant, culturally authentic, and socially inclusive.

Theoretically, this research advances Property Rights Theory and Transaction Cost Economics. It applies them to urban regeneration under China’s public land ownership, which proves their explanatory power in complex transactions. Moreover, our study provides a nuanced understanding of institutional solutions to address fragmentation problems and mediate competing priorities. Furthermore, applying the IAD framework to culture-led regeneration, this research offers a robust analytical tool for examining the multiple-layered interactions among heritage conditions, institutions, and value creation in urban regeneration.

5. Conclusions

Our comparative study demonstrates that property rights reconfiguration is a fundamental mechanism for mediating competing economic, social, and cultural priorities in urban transformation. The divergent pathways of Yisu and the Market underscore a central tension: the land assembly model achieves rapid modernization and monumental redevelopment at the cost of socio-cultural displacement, while the rights subdivision strategy fosters inclusive growth and preserves embedded social value at the expense of higher coordination costs. The success of either approach hinges on context-sensitive institutional arrangements that align with the specific profile of the heritage site and its community.

For sites of high symbolic value and monumental heritage (e.g., the Yisu Opera Theatre), where preservation and large-scale cultural branding are priorities, a state-led land assembly model is often most effective. The state’s power of eminent domain and capacity for large capital investment are crucial for comprehensive planning and infrastructure integration. However, this model must be tempered with inclusive mitigation instruments, such as formal resettlement compensation, priority leasing for displaced businesses in the new development, and cultural subsidy vouchers to ensure original residents can still access the transformed space.

For sites characterized by high community embeddedness and active local economies (e.g., the Old Food Market), where social fabric is the primary heritage value, a rights subdivision and negotiated governance model is imperative. The goal should be incremental improvement, not wholesale redevelopment. Key instruments here include Commercial Affordability Covenants (e.g., graduated rent schemes), the establishment of Community Land Trusts or Right-to-Manage Trusts to protect against gentrification, and formal Binding Neighbourhood Councils with real decision-making power to ensure community interests guide the process.

Ultimately, these findings confirm that effective regeneration requires not only the technical solutions to physical upgrades, but also sophisticated governance frameworks to balance public and private interests. Moreover, this research argues that property rights are not merely legal entitlements but the framework for a dynamic equilibrium among competing priorities. Specifically, this research proposes another property right solution for complex urban regeneration practice different from the conventional land assembly. Moreover, it argues that choice between the two property right strategies must be guided by diagnostic assessment: assembly for symbolic monumental sites, subdivision for socially embedded communities. In practice, most projects will require a hybrid approach, integrating top-down policy support with bottom-up engagement. By adopting this nuanced, context-driven framework, planners and policymakers can craft sophisticated governance solutions that not only achieve physical renewal but also safeguard the social sustainability and historical continuity that define authentic urban place.

To advance these findings, a concrete future research agenda is essential. First, longitudinal studies are needed to track the long-term socio-economic outcomes of different regeneration models over 5–10 year periods. Second, insights derived from China’s public land ownership system should be tested within contexts characterized by different property regimes. Such comparative work would elucidate how the mechanisms of land assembly and rights subdivision function vary across institutional settings and what hybrid models emerge when state power is more circumscribed and private property rights are more dominant. Third, research should investigate the long-term effectiveness and sustainability of specific hybrid governance instruments in preserving socio-economic equity. Finally, studies must explore the transferability and contextual adaptation of these policy instruments. This line of inquiry will contribute to a global toolkit of adaptable, evidence-based policies for inclusive and sustainable urban regeneration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S.; Methodology, C.S.; Formal analysis, L.S.; Investigation, L.S.; Resources, C.S.; Writing—original draft, L.S.; Writing—review and editing, C.S.; Supervision, C.S.; Project administration, C.S.; Funding acquisition, C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Humanities and Social Science Foundation of Ministry of Education of China (Grant No. 20YJC630119).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by School of Public Policy and Administration, Xi’an Jiaotong University (2024112801) on 28 November 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We extend our thanks to Wenwei Guo, Jiren Zhou, Tianqi Zhang, Jinyue Lan, and Mocheng Yang for their detailed investigation. We are also grateful to anonymous referees for their helpful comments and suggestions, which greatly improved the article. Any errors are the authors’ responsibility.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- He, S.; Wu, F. China’s emerging neoliberal urbanism: Perspectives from urban redevelopment. Antipode 2009, 41, 282–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.X.; Wu, G.D. The network governance of urban renewal: A comparative analysis of two cities in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 106, 105448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlfeldt, G.M.; McMillen, D.P. Tall buildings and land values: Height and construction cost elasticities in Chicago, 1870–2010. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2018, 100, 861–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yu, F.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Li, P. Assessing urban renewal efficiency via multi-source data and DID-based comparison between historical districts. Npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatz, G. Can public subsidized urban renewal solve the gentrification issue? Dissecting the Viennese example. Cities 2021, 115, 103218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Parra, I.; Cordero, A.H. Gentrification studies and cultural colonialism: Discussing connections between historic city centers of Mexico and Spain. J. Urban Aff. 2024, 46, 1110–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.J.; Casanovas, M.M.; González, M.B.; Sun, S.J. Revitalizing heritage: The role of urban morphology in creating public value in China’s historic districts. Land 2024, 13, 1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.F.; Zhou, X.P.; Weng, F.F.; Ding, F.Z.; Wu, Y.J.; Yi, Z.X. Evolution of cultural landscape heritage layers and value assessment in urban countryside historic districts: The case of Jiufeng Sheshan, Shanghai, China. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.X.; Wu, S.S.; Zhang, Y.J. Exploring the key factors influencing sustainable urban renewal from the perspective of multiple stakeholders. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommarchi, E.; Jonas, A.E.G. Culture-led regeneration and the contestation of local discourses and meanings: The case of European maritime port cities. Urban Geogr. 2024, 46, 632–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crobe, S.; Giubilaro, C.; Prestileo, F. Can culture save us? Rethinking culture-led touristification from Palermo (Italy). Cities 2025, 167, 106331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.H.; Lin, G.C.S. The drunkard’s intention lies not on the wine: Reinterpreting culture-led urban redevelopment in China amidst profound regime changes. Environ. Plan. A—Econ. Space 2025, 57, 241–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Zhou, Y.M. Conducting heritage tourism—led urban renewal in Chinese historical and cultural urban spaces: A case study of Datong. Land 2022, 11, 2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.F.; Bai, X.H.; Wang, X.C.; Chen, Y.L.; Huang, G.S.; Xie, D.X. Case study on cultural industry empowerment in urban renewal: A focus on Guangzhou, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, L.; Colding, J. Placing urban renewal in the context of the resilience adaptive cycle. Land 2024, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merciu, F.C.; Cercleux, A.L.; Peptenatu, D. Roșia Montană, Romania: Industrial heritage in situ, between preservation, controversy and cultural recognition. Ind. Archaeol. Rev. 2015, 37, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, M.J.; Jiménez-Morales, E.; Rodríguez-Ramos, R.; Martínez-Ramírez, P. Reuse of port industrial heritage in tourist cities: Shipyards as case studies. Front. Archit. Res. 2024, 13, 164–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownill, S.; O’Hara, G. From planning to opportunism? Re-examining the creation of the London Docklands Development Corporation. Plan. Perspect. 2015, 30, 537–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Munday, M. Blaenavon and United Nations World Heritage Site status: Is conservation of industrial heritage a road to local economic development? Reg. Stud. 2001, 35, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miran, F.D.; Husein, H.A. Introducing a conceptual model for assessing the present state of preservation in heritage buildings: Utilizing building adaptation as an approach. Buildings 2023, 13, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerin, R.; Hernández, R.C. What factors guide the recent Spanish model for the disposal of military land in the neoliberal era? Land Use Policy 2023, 134, 106911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J. From land use right to land development right: Institutional change in China’s urban development. Urban Stud. 2004, 41, 1249–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Hou, C.X. Driving mechanisms of green regeneration in old industrial areas under ecological security constraints: Evolutionary Game Theory oriented toward public satisfaction. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2024, 150, 04024008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.M.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.Y. A review of researches on urban renewal in contemporary China and the future prospect: Integrated perspectives of institutional capacity and property rights challenges. Urban Plan. Forum. 2021, 5, 92–100. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shadar, H.; Shach-Pinsly, D. Maintaining community resilience through urban renewal processes using architectural and planning guidelines. Sustainability 2024, 16, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uitermark, J.; Duyvendak, J.W.; Kleinhans, R. Gentrification as a governmental strategy: Social control and social cohesion in Hoogvliet, Rotterdam. Environ. Plan. A—Econ. Space 2007, 39, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manupati, V.K.; Ramkumar, M.; Samanta, D. A multi-criteria decision making approach for the urban renewal in Southern India. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 42, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozer, L.; Höerschelmann, K.; Anguelovski, I.; Bulkeley, H.; Lazova, Y. Whose city? Whose nature? Towards inclusive nature-based solution governance. Cities 2020, 107, 102892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praharaj, S. Area-Based Urban renewal approach for smart cities development in India: Challenges of inclusion and sustainability. Urban Plan. 2021, 6, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louw, E. Land assembly for urban transformation—The case of ‘s—Hertogenbosch in The Netherlands. Land Use Policy 2008, 25, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansel, C.B. Reproducing authoritarian neoliberalism in Turkey: Urban governance and state restructuring in the shadow of executive centralization. Globalizations 2019, 16, 320–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]