Abstract

Australia’s National Housing Accord commits governments to delivering 1.2 million well-located homes by 2029, a target that has redefined housing strategy around scale and speed. Yet this quantitative focus risks overlooking the social and cultural dimensions of adequacy. This paper argues that housing policy framed solely around affordability and supply cannot deliver sustainable or inclusive outcomes in a nation as culturally diverse as Australia. Therefore, we introduce the concept of cultural adaptability as the capacity of housing systems to recognise and accommodate diverse household structures, spatial practices, and community values as a structural dimension of ‘adequacy’. Furthermore, this paper conceptualises a multi-level framework spanning strategic, regulatory, and delivery systems to guide the integration of cultural adaptability within Australia’s housing agenda. The paper concludes by recommending pathways for empirical, analytical, and institutional research to improve cultural adaptability within the Australian housing system.

1. Background

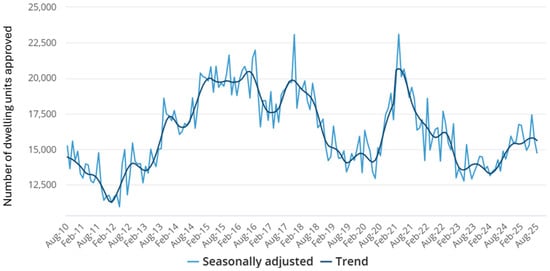

Australia’s housing strategy is now defined by scale and speed. Through National Cabinet, governments committed to deliver “1.2 million well-located homes” between 1 July 2024 and 30 June 2029, a target deliberately framed to break supply bottlenecks and moderate price pressures [1]. To facilitate this, the National Cabinet approved the Commonwealth’s allocation of $3.5 billion in funding to state, territory, and local governments [1]. Despite these commitments, evidence indicates that the industry is unlikely to meet the target [2]. National dwelling approvals have trended down across 2024–2025, with multi-unit approvals especially weak, pushing delivery risk to the back end of the target window and compounding cyclical headwinds in financing and construction capacity (Figure 1) [3]. Aligned with this, industry forecasts now question the target’s feasibility. Master Builders Australia estimates completions will fall short of 1.2 million on current settings, citing labour shortages, elevated input costs, and prolonged approvals as binding constraints [4]. This is consistent with findings from the State of the Housing System 2025 report [2], which projects that only 938,000 dwellings will be delivered under current policy settings, representing a shortfall of around 262,000 homes relative to the Accord’s target, largely due to persistent capacity constraints, high construction costs, and limited project feasibility. This shortfall underscores a supply-side crunch emerging amid sustained demand pressures from population growth, smaller households, and migration.

Figure 1.

A demonstration of total number of dwellings approved in Australia. Sourced from 3. Australian Bureau of Statistics [3].

In response to the ever-increasing demands for housing in Australia, the Commonwealth’s Migration Strategy and subsequent budget settings aim to roughly halve net overseas migration (NOM) from the 2022–2023 peak toward ~260,000 by 2024–2025 [5]. This policy reflex to turn down migration has its own macro- and micro-risks. The full implementation could dampen housing demand at the margin, yet it would also withdraw labour including construction and allied trades from the very sectors needed to build the target, and risk procyclical drag if housing-sensitive activity stalls. This should also be noted that Australia is already facing a significant labour shortfall, with the residential construction sector projected to require an additional 116,700 workers to meet the National Housing Accord target by 2029 [6]. These structural pressures highlight that Australia’s housing response is being driven by urgency and scale, mobilising every policy lever to meet the 1.2 million-home goal despite significant delivery risks. Yet, in the pursuit of quantity, the deeper question of quality—of what kind of housing is being produced and for whom—has received far less attention. The challenge now is not only how many homes can be built, but whether the housing being delivered can meet the diverse social and cultural needs of Australia’s growing population.

As Australia continues to grow and diversify, the homes built under the Accord will shape the social and cultural character of future neighbourhoods. A large portion of the 1.2 million homes now planned will, by design or by default, accommodate newly arrived and culturally diverse communities. Mass development at this scale must therefore be planned not only for efficiency and cost but also for inclusivity and adaptability, making sure that the physical expansion of housing aligns with the social realities of a multicultural nation. In other words, the debate is not just about whether the target can be met, but about what kind of housing is being delivered, for whom, and whether it can genuinely support settlement and participation. UN housing norms are explicit that ‘adequacy’ extends beyond ‘four walls and a roof’ to include security of tenure, services, affordability, habitability, location, accessibility, and even more critically, the cultural adequacy which translates to the ability of housing to respect and enable cultural identity and practices [7]. A supply programme that fails to account for these criteria risks producing stock that is formally ‘delivered’, yet substantively unfit for many residents.

Another consideration is whether the dwellings delivered under this programme reflect the way ‘home’ is understood and lived in Australia. The retrospective research on domestic life shows that the Australian idea of home has been shaped by expectations of privacy, autonomy, and the nuclear-family household, often centred on detached suburban living [8]. These norms are embedded not only in cultural practice but in the planning and design assumptions that guide mainstream development. Yet many communities, particularly newly arrived, multigenerational, or culturally diverse households create and sustain home through distinct spatial and social logics such as shared routines, collective care, or flexible use of space which do not align with the conventional assumptions embedded in standard housing models [9]. Recognising these varied forms of homemaking is essential if large-scale delivery is to support settlement, belonging, and everyday living, rather than reproduce a narrow template of domestic life.

Evidence from Australia’s refugee and asylum-seeker literature shows how ‘culture-blind’ provision undermines integration and health through housing’s social and spatial qualities. Studies in South Australia demonstrate that neighbourhood satisfaction, characterised by proximity to social ties, services and co-ethnic supports, is more predictive of resettlement satisfaction than dwelling attributes per se [10,11]. Participants repeatedly tie wellbeing to bridging and bonding networks with neighbours and co-ethnic communities. When new arrivals are placed in cheaper but socially misaligned suburbs, those networks do not develop, and their sense of ontological security begins to weaken, which in turn may affect their both mental and physical health [10,11,12]. These findings recast ‘location efficiency’ to include cultural infrastructure (e.g., faith spaces, shops, language networks), alongside transport or jobs access.

Qualitative work reaches the same conclusion from another angle: sense of home hinges on the capacity to express identity, host and be hosted, and practice daily routines capabilities that are mediated by both the dwelling layout and the surrounding social fabric [13]. Cooperative-housing research in Melbourne also shows autonomy to modify spaces and participate in community governance strengthens personal and social ‘home’, with residents explicitly linking modifiability and shared spaces to wellbeing [13]. In a study, Fozdar and Hartley [14] examined refugee housing in Western Australia, showing that housing, employment, and health outcomes are closely linked to social connections and cultural understanding and are undermined when housing is insecure, poorly located, or culturally misaligned.

Current Australian scholarship on migrant housing aspirations underscores the policy gap. Stone et al. [15] argue that as Australia diversifies, the adequacy of existing stock and new supply to meet culturally differentiated aspirations becomes a central planning test, yet present development logics tend to homogenise preferences, especially in high-volume delivery contexts. They highlight the unresolved tension between assimilation into prevailing housing forms versus enabling culturally meaningful modifications, tensions that are largely invisible in headline targets and generic affordability debates [15,16]. Lozanovska’s work goes further, documenting how negative attitudes toward ethnic-minority architectural expression can push cultural practices inside the home (curtains for privacy, guest reception rooms, ablution arrangements), where dwelling typologies may not accommodate them, nudging residents toward costly after-the-fact alterations [16]. Collectively, these studies reveal that when housing design fails to accommodate cultural norms around privacy, or hosting, residents tend to adapt through informal renovation responses that may potentially lead to waste generation, regulatory conflict, and environmental cost, and thus undermining housing efficiency and residents’ wellbeing.

International human-rights frameworks provide an important normative foundation for housing policy, recognising cultural adequacy and participation as essential elements of the right to adequate housing. The UN’s adequacy criteria (including cultural adequacy and location) are not aspirational add-ons; they are part of States’ obligations, with participation by affected communities a core entitlement [7]. Large-scale delivery done without structured consultation and cultural due diligence is exactly what the UN guidance warns against, i.e., projects ‘carried out with little or no consultation’ that later require disruptive correction. Embedding these principles into Australia’s housing agenda would reframe adequacy as both a social and cultural commitment, aligning large-scale delivery with the lived realities and rights of the communities it aims to serve.

Motivation for This Study

This paper addresses an underexplored dimension of Australia’s housing agenda which is the absence of mechanisms that recognise and operationalise cultural adaptability within housing policy and delivery. Although the National Housing Accord and related frameworks prioritise supply, affordability, and system performance, they remain largely silent on how housing design and governance can reflect the social and cultural diversity of contemporary Australia. This gap matters because, in a nation built on migration, the inclusiveness and adaptability of housing are integral to both social cohesion and long-term sustainability. The paper therefore aims to reframe adequacy not merely as a matter of quantity or affordability, but as a condition shaped by how well housing supports belonging, participation, and everyday life across diverse cultural contexts. If we fail to account for these in the push to deliver 1.2 million homes, we risk producing units that are quickly remodelled, rapidly churned through, or simply avoided, wasting scarce capital and undermining trust in public programmes.

Against this backdrop, the aim of this paper is to highlight the missing cultural dimension within Australia’s current housing policy agenda and to propose a framework for embedding cultural adaptability across the housing system. The paper argues that housing adequacy must extend beyond affordability and supply to include the social and cultural conditions that shape how people live. It develops a conceptual framework spanning three levels of governance, namely strategic, regulatory, and delivery to demonstrate where and how cultural adaptability can be incorporated within Australia’s housing strategy. The framework is not prescriptive but intended as a foundation for future research, modelling, and policy development that can support housing outcomes which are not only affordable and sustainable, but also inclusive and responsive to Australia’s cultural diversity.

2. Methodological Approach

This paper adopts a conceptual and narrative review approach to examine why cultural adaptability is missing from Australia’s current housing agenda. The work is guided by the study’s aim, which is to show that housing adequacy in a diverse nation like Australia cannot be reduced to targets, supply metrics, or affordability indicators. The motivation behind this paper is to highlight the structural gaps that prevent cultural needs from being recognised in the way housing policy is designed and delivered.

The analysis builds on three bodies of literature. The first relates to housing governance and adequacy in Australia. The second focuses on migrant and refugee housing experiences, particularly the cultural and social factors that shape how people live in their homes and neighbourhoods. The third draws on international examples where cultural or community-led principles have informed the design or governance of housing systems. The international cases are included because they offer clear illustrations of culturally grounded or community-driven approaches. However, it should be acknowledged that these cases are not presented as a comprehensive comparison. Their purpose is to demonstrate that cultural adaptability can be potentially incorporated into real policy settings and is therefore relevant to the Australian context.

This study does not involve new empirical data. Its purpose is to synthesise existing academic and policy evidence and use this synthesis to identify conceptual gaps within Australia’s housing system. The interpretive nature of this approach allows the paper to connect insights from lived experience with the structures and instruments that shape housing delivery. This provides a basis for developing the multi-level framework proposed later in the paper and offers a foundation for future empirical and analytical work.

3. Gaps in Australia’s Housing Policy

Contemporary housing debates in Australia remain dominated by an economic rationality that privileges market efficiency and supply expansion over social purpose. The National Housing Accord illustrates this orientation, positioning quantitative delivery targets as the primary indicator of progress. Such framing reflects what James et al. [17] identify as the structural entrenchment of market-oriented policy mechanisms that equate housing provision with adequacy and obscure the distributional consequences of financialised systems. Policy rhetoric is saturated with imperatives to ‘unlock land supply’ and ‘streamline approvals,’ yet rarely questions for whom this supply is produced or what social outcomes it secures. As Doyon et al. [18] argue, when housing policy is reduced to metrics of growth and fiscal efficiency, it privileges economic throughput at the expense of ecological integrity and community wellbeing. What is sidelined is the understanding of housing as a foundation of health, belonging, and social inclusion.

This market-centred paradigm has generated outcomes that are spatially and socially uneven. Decades of financialisation and the residualisation of public housing have deepened the divide between those who accumulate housing as an investment and those who rely on it as shelter [17]. The result is a geography of inequality that is systemic rather than incidental produced by policy frameworks that treat fiscal restraint as a virtue even when it undermines social resilience. Comparative evidence demonstrates that more inclusive housing regimes, where public and cooperative sectors play a stabilising role, are associated with higher life satisfaction and reduced inequality [19]. Australia’s retreat from social provision and its reliance on speculative private delivery therefore represent not simply a policy imbalance but a conceptual misalignment: the aspiration to deliver ‘housing for all’ through mechanisms that structurally exclude those most in need. The discourse of supply thus functions as a political alibi, legitimising expansion of the private market while masking the withdrawal of the state from its social obligations.

The social consequences of this imbalance are sharply evident in the housing experiences of refugees and asylum seekers. McShane et al. [20] demonstrate that overcrowded, insecure, or culturally inappropriate housing contributes directly to psychological distress and impedes long-term settlement. Similarly, Ziersch et al. [10] show that successful resettlement depends not only on the physical quality of dwellings but on neighbourhood belonging, access to community networks, and the capacity to sustain culturally meaningful daily practices. Even when formal adequacy criteria such as affordability, amenities, and safety are met, the absence of cultural and spatial fit produces hidden exclusion. Many households respond through informal modification or relocation, adaptive strategies that express resilience but expose systemic failure. These unmeasured adjustments carry financial, environmental, and social costs that rarely appear in official evaluations of housing performance yet cumulatively undermine the efficiency that current policy frameworks claim to pursue.

A transition toward sustainable and equitable housing futures therefore requires reconceptualising ‘adequacy’ as a socially embedded condition rather than a numeric benchmark. International guidelines, including the United Nations’ criteria for Adequate Housing, emphasise that cultural adequacy, habitability, and locational appropriateness are integral to the right to housing [21]. Integrating these dimensions into national policy would not dilute economic goals, rather it would enhance them by reducing retrofit waste, stabilising communities, and improving wellbeing and productivity through inclusion. As Doyon et al. [18] describe this shift as reframing housing as relational infrastructure that supports social and environmental systems. Recent studies on collaborative and cooperative housing provide insight into how adequacy is shaped by the institutional conditions in which housing is organised. Work mapping variation in tenure arrangements, governance structures and shared values shows that these elements influence how households negotiate everyday living and interpret cultural and social fit within their homes [22]. Research on cooperative models also demonstrates that affordability and cultural adequacy can be integrated through participatory and non-speculative governance, offering a view of housing systems where social purpose is embedded in institutional design rather than added as a secondary consideration [23]. There is also research [24] suggesting that conventions around privacy, hosting and everyday spatial modification are formed through social practice and gradually embedded within property norms. Zhang [25] also proposed reconceptualizing tenure beyond the owning–renting divide further show that hybrid and culturally shaped occupancy arrangements influence how households meet their housing needs across diverse contexts.

The challenge for Australia’s 1.2 million-home agenda is therefore not only quantitative but qualitative, ensuring that the homes delivered contribute to social cohesion, wellbeing, and cultural vitality, and reflect the diverse ways Australians live and belong.

4. Cultural Diversity and Housing Futures

Housing is more than a built product; it is a social and cultural infrastructure that mediates belonging, identity, and collective wellbeing. Across Australian and international literature, scholars have shown that migrants’ experiences of housing are shaped less by the physical adequacy of dwellings than by their social and cultural legibility within everyday life. Studies by Ziersch et al. [10] and Fozdar and Hartley [14] reveal that refugees and migrants interpret housing as a domain through which stability, privacy, and continuity of cultural practice are negotiated in a new environment. Neighbourhood belonging, proximity to community networks, and freedom to organise domestic space consistently emerge as stronger predictors of satisfaction than structural dwelling features. Comparative evidence from Europe and Canada shows that neighbourhoods designed to support social cohesion, multigenerational living, and community belonging tend to improve migrant integration and housing satisfaction [11,26,27]. These findings suggest that housing adequacy cannot be detached from cultural adequacy; each reinforces the other as a condition of meaningful settlement.

The notion of cultural mismatch provides a useful conceptual lens to understand why standardised housing typologies often fail to meet the lived needs of diverse populations. In her work on migrant housing, Lozanovska [16,28] demonstrates that dominant suburban and apartment forms in Australia embed specific cultural assumptions about family structure, privacy, and gendered use of space. These design conventions, inherited from Eurocentric planning traditions, reproduce a singular understanding of domestic life that excludes alternative ways of dwelling. Stone et al. [15] further highlight that the persistent misalignment between cultural practices and spatial design reflects entrenched institutional path-dependencies in Australia’s housing system, where migrant aspirations remain largely excluded from mainstream planning and development processes. Migrant households frequently respond through informal adaptation, e.g., partitioning interiors, converting garages, or sharing dwellings across extended family networks in order to reconcile their social practices with rigid architectural templates. This tendency is consistent with evidence showing that migrants, drawing on pre-migration housing experiences, frequently seek to modify or enhance their homes to align with familiar lifestyles and cultural expectations, such as increasing spatial separation and incorporating additional privacy features [29,30]. Rather than anomalies, these modifications expose a persistent tension between housing as designed and housing as lived. The mismatch, therefore, should be read not as personal preference but as a structural symptom of a policy environment inattentive to cultural plurality.

Ignoring these cultural dimensions carries significant social, economic, and environmental costs. Socially, culturally misaligned housing has been shown to undermine mental health and weaken settlement outcomes. McShane et al. [20] found that overcrowding, instability, and lack of culturally suitable housing contribute directly to psychological distress among refugees, compounding the challenges of resettlement. Economically, these inadequacies translate into inefficiencies: when households must remodel or relocate to achieve cultural fit, resources are diverted toward retrofitting rather than sustainable design. As Doyon et al. [18] observe, the environmental burden of such retrofits through material waste and shortened building lifespans contradicts the objectives of sustainable housing policy. Within the context of Australia’s 1.2 million-home target, these oversights risk producing a volume of housing that is formally compliant yet functionally deficient, exacerbating both inequality and ecological impact. A culturally inattentive housing strategy thus undermines its own efficiency by externalising social and environmental costs that could have been mitigated through inclusive design.

Cultural diversity should not be treated as a challenge to housing policy but as a foundation for innovation. Recognising cultural variation in domestic life expands the repertoire of design solutions and strengthens the resilience of urban systems. International frameworks, including the UN-Habitat agenda on inclusive urban transformation [21], advocate for participatory design and co-production as mechanisms to align housing delivery with community needs. Embedding these principles within Australia’s housing agenda would enable the system to move beyond its reactive supply orientation toward a proactive model of social infrastructure development. The cultural dimension of housing, therefore, is not an adjunct concern but a strategic asset: it generates more adaptive, enduring, and equitable forms of urban living. Building for diversity means building for sustainability, making sure that the homes constructed today remain liveable, inclusive, and meaningful for the communities that will inhabit them tomorrow.

5. Towards Culturally Responsive Housing Policy

Australia’s National Housing Accord embodies an economic and technocratic conception of housing delivery, where success is measured through numerical targets, affordability ratios, and streamlined planning approvals. These priorities are necessary yet reflect a narrow understanding of ‘adequacy’—one that reduces housing to a physical product or market commodity rather than recognising it as a social and cultural institution. To a large extent, this approach perpetuates a post-war policy legacy in which the state’s role was limited to coordinating production instead of shaping the lived meaning of home [31].

Building on UN-Habitat’s recognition of cultural adequacy as a component of the right to housing [21], this paper redefines ‘adequacy’ for the Australian context as cultural adaptability: the capacity of housing systems to recognise and accommodate diverse household structures, domestic practices, and social values. This reinterpretation extends existing adequacy frameworks beyond their material and economic dimensions, positioning housing as a cultural infrastructure essential to sustainable and inclusive urban futures.

Cultural adaptability does not imply designing separately for each cultural group but rather designing flexibly for diversity. It involves providing dwellings and neighbourhoods that can accommodate variations in spatial use, privacy expectations, family composition, and community interaction. In Australia, current housing typologies largely remain built around a narrow model of the ‘standard household’, reproducing Eurocentric assumptions of the nuclear family and individualised living arrangements. Align with this argument, previous studies like Lozanovska [16] and Stone and Parkinson [15] have also shown that these inherited typologies systematically marginalise alternative ways of dwelling, constraining the everyday agency of culturally diverse households. Therefore, embedding adaptability at the level of policy and design would allow the built environment to evolve with social change rather than resist it.

International precedents demonstrate that cultural adequacy can be embedded within national housing frameworks. UN-Habitat’s Adequate Housing criteria explicitly recognise cultural adequacy as a core dimension of the right to housing [21]. Several national strategies have operationalised this principle to varying degrees. Canada’s National Housing Strategy adopts a rights-based approach, integrating Indigenous-led and community-driven design streams, while New Zealand’s Kāinga Ora and Whai Kāinga Whai Oranga programmes advance Māori-led housing initiatives that connect cultural identity with spatial planning. Similarly, community-led housing models in the Netherlands and Scotland (Table 1) reveal that participatory design and local governance can strengthen social cohesion and long-term settlement outcomes. Collectively, these examples show that acknowledging cultural difference in housing policy is not an abstract ideal but a pragmatic condition for social sustainability.

Table 1.

International housing frameworks incorporating culturally grounded or community-led design principles.

In contrast, Australia’s housing policy architecture lacks the institutional mechanisms to translate social and cultural needs into measurable design and planning standards. Although ‘social inclusion’ has become a recurring motif across housing and urban policy rhetoric, it remains inconsistently defined, rarely measured, and largely detached from the actual instruments governing housing delivery. The National Housing Accord continues to rely on market-led production, supply-side incentives, and aggregated delivery targets, with limited capacity to evaluate ‘who’ benefits from these homes and ‘how’ they align with lived social realities. The absence of metrics for cultural adequacy such as adaptability, spatial flexibility, or resident participation, means that inclusivity is treated as a rhetorical value rather than a performance criterion.

Research on urban governance shows that metropolitan housing systems rarely operate through coherent or unified control. Galès and Vitale [43] describe these systems as fragmented, negotiated and often incomplete, with policy outcomes shaped by coordination under constraint rather than through top-down design. This perspective aligns with the way this paper understands decision-making in Australia and supports the idea that cultural adaptability can emerge within existing institutional arrangements. The framework proposed in this paper is grounded in the structural reality of Australia’s housing governance and informed by conceptual and international precedents. Housing delivery in Australia is inherently multi-level. The Commonwealth establishes national policy direction and funding mechanisms. States and territories define regulatory settings through planning, design and construction codes. Local governments and delivery agencies implement projects on the ground. Addressing cultural adaptability within such a system requires coordination across these layers, since decisions at each level influence design, location and social outcomes.

Conceptually, the framework builds on insights from housing adequacy literature and governance studies that emphasise the relational nature of housing that is, its role as social, cultural, and environmental infrastructure rather than merely a physical asset. Previous studies [10,11,12,18,20,44] have shown that inclusive housing systems depend on institutional alignment, where policy, regulation, and practice reinforce one another to support social and cultural wellbeing. This view is consistent with international approaches such as Canada’s National Housing Strategy and New Zealand’s Kāinga Ora programmes, both of which incorporate culturally grounded design principles through multi-level governance structures.

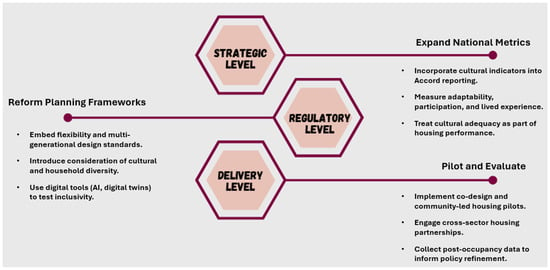

Drawing on these foundations, the framework presented here identifies three interdependent domains including strategic, regulatory, and delivery through which cultural adaptability can be embedded in the Australian housing system (Figure 2). Each domain represents a point of leverage where cultural and social considerations can be integrated into decision-making, from the definition of national housing objectives to the planning instruments that regulate design, and the delivery processes that shape lived experience.

Figure 2.

Multi-level framework for cultural adaptability in housing.

- At the strategic level, current national frameworks such as the National Housing Accord [1] and the National Housing Supply and Affordability Council (NHSAC) [45] predominantly focus on supply, affordability, and system performance. Their definitions of adequacy, emphasising housing that is ‘affordable, fit for purpose, and secure for all households’ are essential but remain largely functional, referring to suitability across life stages, accessibility, and geographic distribution rather than cultural or social dimensions. The NHSAC’s State of the Housing System 2025 [2] report reinforces this orientation, framing the national housing vision around affordability, security, and fitness for purpose. The report identifies several critical reform domains such as planning efficiency, productivity, and rental security but its scope remains primarily economic and technical.

- Building on this foundation, the framework calls for a redefinition of adequacy at the strategic level to include cultural adaptability as a structural dimension of housing performance. This reframing recognises that long-term housing outcomes depend not only on the volume and cost of supply but on how well housing supports inclusion, social cohesion, and lived quality. The strategic architecture could therefore evolve to incorporate three complementary dimensions, namely adaptability, participation, and post-occupancy experience as benchmarks for assessing the effectiveness of national housing policy. Adaptability reflects the system’s capacity to accommodate diverse household structures and cultural practices; participation ensures that planning and decision-making processes actively involve affected communities; and post-occupancy experience captures how residents interact with and modify their living environments over time. Together, these dimensions create a more holistic understanding of adequacy that links policy intent to lived outcomes. Further research is needed to operationalise these dimensions through measurable indicators and evaluative tools so that future housing strategies can integrate cultural and social objectives with the same rigour applied to economic and environmental ones.

- At the regulatory level, planning and design systems administered by state and territory governments determine how national objectives are translated into built outcomes. These frameworks include instruments such as state planning policies, design guides, and the National Construction Code, which collectively shape the standards for housing form, density, and quality. At present, these mechanisms pay limited attention to cultural adaptability or multi-generational design. Incremental progress has been made, particularly in New South Wales and Victoria where planning frameworks have begun to integrate universal design and adaptable housing provisions. For instance, the NSW Apartment Design Guide (under the State Environmental Planning Policy—Housing 2021) [46] includes requirements for universal design and adaptable housing focused on accessibility and ageing in place, while Victoria’s Better Apartments Design Standards [47] mandate compliance with Liveable Housing Design Guidelines to enhance physical usability.

- These initiatives, however, remain narrowly framed around physical access and mobility. This limitation reflects a long-standing compliance orientation within the regulatory system, where design performance is assessed mainly through technical conformity rather than social or cultural responsiveness. Expanding this perspective would enable adaptability to be understood not only as a functional quality but also as the capacity of housing to accommodate diverse ways of living. Future planning and design frameworks could embed this broader understanding by requiring cultural impact assessments, inclusive design modelling, and feedback loops that translate post-occupancy insights into continuous policy refinement. Studies of incentive-based regulation [48] showed that planning systems can steer development outcomes by adjusting rewards and conditions attached to design codes and funding mechanisms, which provides a practical pathway for promoting culturally adaptive housing within existing regulatory settings.

- In addition, emerging analytical tools, such as parametric urban modelling, digital twins [49,50], and AI-assisted spatial analysis, can also facilitate this shift by testing how different cultural and household configurations perform within standardised housing typologies, providing a stronger, data-informed foundation for regulatory innovation.

- At the delivery level, the opportunity lies in testing these ideas through practice. The Accord’s implementation structure, anchored in partnerships between Housing Australia [51], community housing providers, and private developers could host pilot initiatives that demonstrate how cultural responsiveness can improve housing performance and resident wellbeing. Community-led housing projects, co-design panels, and living laboratories would provide evidence on how inclusive design processes translate into measurable outcomes. Existing data and knowledge infrastructures, such as Housing Australia’s dashboards [52] and related research partnerships could evolve into participatory digital platforms that capture post-occupancy feedback and support continuous learning.

- Demonstration projects that combine community participation with smart-technology monitoring provide tangible pathways to test how cultural adequacy, sustainability, and affordability can coexist within scalable housing models. Equally important is the exploration of construction methods and technologies such as modular and prefabricated systems that allow internal layouts and building components to be reconfigured with minimal structural intervention. These approaches can extend the lifespan and adaptability of housing, enabling residents to modify spaces in response to evolving household structures or cultural needs without resorting to disruptive renovation or demolition. Policy support for such adaptable delivery models would not only reduce material waste but also strengthen the alignment between housing design, resident agency, and long-term sustainability. Crucially, insights derived from these pilots should inform future iterations of policy and regulation, completing a feedback loop between delivery and governance. Embedding this learning process would position the delivery stage not merely as the end of the pipeline but as a dynamic interface, where lived experience actively shapes housing policy, ensuring that inclusivity and adaptability are sustained over time.

Institutionalising cultural adaptability within Australia’s housing system is not only a matter of administrative reform. It represents a gradual shift in how housing is understood, governed and assessed. When pursued through existing policy and planning frameworks, this shift can emerge through the realignment of priorities, incentives and design expectations rather than through structural overhaul. It enables housing institutions to recognise that adequacy is shaped by the social and cultural conditions of everyday life, and that meaningful policy outcomes depend on sustained interaction between governance, design practice and community experience. This approach strengthens the capacity of institutions to respond to demographic change, diverse household forms and evolving cultural expectations. Over time, it can support a housing ecosystem that learns from the lived experiences of its residents and uses that knowledge to guide planning and design decisions. The broader implication is that cultural adaptability becomes a marker of social equity and an element of resilient housing governance, turning housing supply into an ongoing process of cultural learning and civic responsiveness.

6. Future Directions for Research, Policy and Practice

Improving cultural adaptability in housing requires moving beyond conceptual acknowledgment toward an evidence-driven and institutionally embedded agenda. The multi-level framework proposed in this paper offers a foundation for such progression, yet its full implementation still requires a thorough coordinated research effort that cuts across disciplines, governance tiers, and industry boundaries. Future inquiry must generate the empirical, analytical, and policy insights necessary to operationalise this framework, transforming it from a conceptual structure into a living methodology that informs both decision-making and design. This calls for approaches capable of bridging lived experience and spatial analytics, community practice and governance reform, qualitative depth and computational precision. As recent housing research has emphasised (e.g., Ziersch et al. [10,11]; Lozanovska [16]), the challenge is not merely to describe cultural diversity, but to translate it into measurable forms of design intelligence and policy performance. In this light, future works must treat cultural adaptability not as an abstract social goal, but as a methodological and institutional frontier—one that redefines how housing adequacy is studied, modelled, and governed in Australia. To this end, the current study offers the following recommendations.

- Building a culturally adaptive housing agenda requires a stronger empirical foundation that captures how people actually live, modify, and interpret their dwellings within diverse cultural contexts. Much of the existing evidence base focuses on affordability, accessibility, and perceived adequacy, yet remains silent on how cultural identity, spatial norms, and intergenerational dynamics shape the lived performance of housing [10,11,16]. Future research must therefore move beyond attitudinal surveys and adopt methods capable of revealing the processes through which cultural adaptation occurs. Ethnographic case studies, participatory mapping, and longitudinal post-occupancy evaluations could document how residents negotiate privacy, domestic roles, and community interaction within standardised housing typologies. This could be coupled with carrying out comparative investigations across urban and regional settings to help identify whether current design and policy assumptions support or suppress these everyday practices.

- Importantly, empirical inquiry should not only describe difference but seek to generate translatable evidence such as metrics, typologies, and behavioural insights that can inform planning instruments and housing assessment frameworks. This shift demands collaboration between social scientists, planners, and designers to co-develop mixed-method protocols that bridge qualitative depth with policy relevance. By grounding cultural adaptability in lived experience, empirical research can transform it from an aspirational concept into an observable and measurable feature of housing performance.

- Translating cultural adaptability into actionable design and policy insights requires analytical frameworks capable of testing how cultural, social, and spatial variables interact within the built environment. Existing modelling practices in housing whether in urban analytics, energy optimisation, or density forecasting rarely account for cultural or behavioural diversity. They tend to treat households as uniform units, optimising for efficiency rather than adaptability. Future research should challenge this bias by developing modelling approaches that integrate cultural parameters into the computational evaluation of housing performance.

- Parametric design, agent-based simulation, and digital twin [49,53,54] environments can be extended to model how diverse household compositions, privacy expectations, and spatial routines influence dwelling functionality and neighbourhood cohesion. Such tools could also test the regulatory implications of key planning decisions before they are implemented, allowing planners to evaluate how flexible or restrictive a policy might be under varying cultural assumptions. The critical task is to move from modelling the physical efficiency of housing to modelling its social intelligence, creating data environments that capture adaptability, interaction, and lived use patterns as part of design optimisation. Integrating these tools with empirical evidence from post-occupancy studies would provide a feedback loop between lived reality and computational prediction, advancing an evidence-based framework for culturally responsive planning and regulation.

- Embedding cultural adaptability within Australia’s housing system ultimately depends on how empirical and analytical insights are institutionalised within governance and policy structures. Current housing policy frameworks, including the National Housing Accord and related state-level strategies, remain primarily oriented toward supply delivery and affordability metrics, with little capacity to measure how housing performs as a social or cultural system. Future research and policy collaboration must therefore focus on developing mechanisms that can translate evidence into governance practice. This includes creating new indicators of cultural adequacy such as measures of spatial flexibility, intergenerational living capacity, and participatory design engagement that can be integrated into existing monitoring instruments like the National Housing Data Dashboard.

- Pilot programmes and policy experiments could test these indicators in partnership with planning authorities, developers, and community housing organisations, demonstrating how social and cultural value can be quantified alongside cost and emissions performance. Over time, these initiatives would help establish a national framework for assessing housing outcomes through a more holistic lens one that recognises inclusivity, belonging, and adaptability as core dimensions of adequacy. For institutional impact, funding bodies and regulatory agencies must treat cultural adaptability not as an optional design attribute but as a measurable policy objective embedded within performance reporting, incentive structures, and procurement criteria. In doing so, Australia’s housing governance could evolve from a model of production and compliance to one of learning and responsiveness, where policy continually adapts to evidence drawn from lived experience. Beyond indicator development, culturally informed evidence becomes actionable only when institutions have the capacity to interpret and apply it. Intermediary bodies such as local councils, housing authorities, design review panels and community development organisations often act as the practical sites where cultural preferences are translated into planning conditions, assessment criteria or design revisions. Strengthening these institutional pathways would allow cultural intelligence generated through research and post-occupancy insight to inform regulatory decisions without creating additional bureaucratic layers.

Collectively, these research and policy pathways signal the need for a paradigm shift in how housing systems are studied, designed and governed. Embedding cultural adaptability is not simply a matter of refining design practice or expanding policy metrics. It requires rethinking housing as a form of social infrastructure that learns from its occupants and evolves with demographic and cultural change. The multi-level framework proposed in this paper provides a structure for this transformation by linking empirical observation, analytical modelling and institutional reform in a continuous cycle of evidence and feedback. As part of this evolution, indicators such as spatial flexibility, intergenerational living capacity and participatory design engagement can be incorporated into existing planning tools, procurement processes and housing quality assessments. This offers practical mechanisms for embedding cultural intelligence within mainstream governance settings and supports more systematic evaluation of social and cultural performance alongside cost, density and environmental targets. The full development of this agenda will require long-term collaboration between researchers, planners, digital technologists and policymakers, supported by funding mechanisms that prioritise integration across these domains. In this sense, cultural adaptability becomes both a research frontier and a governance challenge and represents an opportunity to create a housing system that is not only efficient and affordable but also reflexive, inclusive and resilient to the social transformations that define twenty-first century Australia.

7. Conclusions

This paper has demonstrated that addressing Australia’s 1.2 million-home target demands more than increasing supply; it requires rethinking the social and cultural logic that underpins housing provision. Recognising cultural diversity within housing does not imply designing for separation or marginalised enclaves but making sure that homes and neighbourhoods remain flexible enough to accommodate the realities of a multicultural society. By introducing the concept of cultural adaptability, the study redefines adequacy as a living and relational condition shaped by how people inhabit, modify, and find belonging within their dwellings. The multi-level framework developed here, spanning strategic, regulatory, and delivery systems provides a structured pathway for embedding this principle into housing governance, planning, and design. In doing so, the paper positions cultural adaptability not as an ancillary concern but as a foundation for integration, sustainability, and long-term system resilience. The following key insights consolidate the conceptual and practical contributions advanced through this research.

- Reframing housing adequacy: the study establishes that adequacy must extend beyond quantitative metrics of affordability and supply to incorporate lived and cultural performance. This reframing exposes how current housing systems overlook aspects of identity, belonging, and community connection dimensions that underpin social sustainability. Recognising housing as a cultural infrastructure challenges standardised design templates and underscores that inclusivity and environmental efficiency can coexist through adaptable design and planning.

- Embedding adaptability within governance structures: the framework demonstrates that cultural responsiveness can be achieved without creating new bureaucratic entities or marginal systems. By recalibrating existing mechanisms such as the National Housing Accord, state planning codes, and community delivery models, governance can integrate cultural and social indicators into decision-making and evaluation. This turns inclusion into a measurable policy objective rather than a symbolic aspiration, aligning housing delivery with broader national commitments to equity and cohesion.

- Bridging empirical and analytical evidence: the paper identifies a critical research frontier: developing empirical and computational evidence that links lived experience with design and policy evaluation. Through ethnographic inquiry, parametric modelling, and digital-twin simulations, future research can test how housing typologies and regulatory decisions perform across diverse cultural and household contexts. This integration of qualitative and analytical insight creates an evidence base for housing systems that can learn and evolve alongside the populations they serve.

- Guiding future policy and practice: cultural adaptability should inform the next generation of housing strategies as a central performance measure—comparable to affordability, sustainability, and emissions outcomes. Embedding adaptability ensures that housing policy evolves from a production-focused model to one centred on social and ecological outcomes. By fostering inclusivity, reducing retrofit waste, and enabling long-term community resilience, culturally adaptive housing can advance both environmental stewardship and social integration within Australia’s increasingly diverse urban and regional landscapes.

Although this study is situated within the Australian housing landscape, its implications extend well beyond the 1.2-million-home agenda. Large-scale housing programmes in any national context face similar pressures to deliver quickly, uniformly and at volume, often at the expense of the social and cultural realities of the communities they intend to serve. The framework developed in this paper highlights that cultural adaptability is not unique to Australian concern but a structural requirement for any mass housing system that seeks to support settlement, belonging and long-term liveability. Treating cultural diversity as a design and governance parameter rather than an afterthought offers a pathway for other countries undertaking rapid or large-scale development to avoid the social, environmental and economic costs of culturally mismatched housing. In this sense, the paper contributes a broader conceptual lens for rethinking how housing systems can remain responsive in increasingly diverse societies.

While the framework proposed in this paper offers a conceptual foundation for embedding cultural adaptability within Australia’s housing system, it remains an exploratory model that will require further empirical development. Future research will need to establish clearer criteria for evaluating the effectiveness of culturally adaptive approaches, develop methodological tools for assessing cultural needs across diverse communities, and design validation strategies that can test how cultural indicators perform in practice. These tasks fall beyond the scope of the present work, which sets out the conceptual pathway rather than its technical instrumentation. Dedicated research and funding will be essential to translate this foundation into operational tools capable of guiding policy and design. The aim of this paper is to stimulate collaboration between policymakers, researchers and industry partners to advance the understanding and application of cultural adaptability in housing. The framework presented here should therefore be seen not as a final statement but as an evolving basis for reimagining how Australia’s housing system can reflect and sustain the diversity of its people.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-5, 2025) for the sole purpose of improving the English expression and readability of the text. The author has reviewed and edited all output and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- National Housing Accord. Delivering the National Housing Accord. Available online: https://treasury.gov.au/policy-topics/housing/accord (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- National Housing Supply and Affordability Council (NHSAC). State of the Housing System. 2025; Australian Government, Department of the Treasury: Canberra, Australia, 2025. Available online: https://share.google/zYrbqg9dqeGXVfGj6 (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Building Approvals, Australia. 2025. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/industry/building-and-construction/building-approvals-australia/latest-release (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Master Builders Australia. Builders Warn Housing Target Slipping Further Out of Reach as Forecasts Downgraded. 2025. Available online: https://masterbuilders.com.au/builders-warn-housing-target-slipping-further-out-of-reach-as-forecasts-downgraded/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Department of Home Affairs. The Administration of the Immigration and Citizenship Programs (13th ed.). 2024. Available online: https://immi.homeaffairs.gov.au/programs-subsite/files/administration-immigration-programs-13th-edition.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- BuildSkills Australia. Housing Workforce Capacity Study Report 2024; BuildSkills Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2024; Available online: https://buildskills.com.au/housing (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- United Nations. Fact Sheet No. 21 (Rev. 1): The Right to Adequate Housing. 2009. Available online: https://share.google/S8215liOVzFcM9Bhi (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Allon, F. At home in the suburbs: Domesticity and nation in postwar Australia. Hist. Aust. 2014, 11, 13–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easthope, H.; Liu, E.; Judd, B.; Burnley, I. Feeling at home in a multigenerational household: The importance of control. Hous. Theory Soc. 2015, 32, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziersch, A.; Due, C.; Walsh, M. Housing in place: Housing, neighbourhood and resettlement for people from refugee and asylum seeker backgrounds in Australia. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2023, 24, 1413–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziersch, A.; Walsh, M.; Due, C. ‘Having a good friend, a good neighbour, can help you find yourself’: Social capital and inte-gration for people from refugee and asylum-seeking backgrounds in Australia. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2023, 49, 3877–3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Due, C.; Ziersch, A.; Walsh, M.; Duell-Piening, P.; Peters, D. Housing and health for people with refugee- and asylum-seeking backgrounds: A photovoice study in Australia. Hous. Stud. 2022, 37, 1598–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guity-Zapata, N.A.; Stone, W.M.; Nygaard, C. The collective meaning of “sense of home”: Experiences from a rental housing cooperative in Melbourne, Australia, and Choluteca, Honduras. Hous. Theory Soc. 2025, 42, 571–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fozdar, F.; Hartley, L. Housing and the creation of home for refugees in Western Australia. Hous. Theory Soc. 2014, 31, 148–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, W.M.; Nygaard, C.; Guity-Zapata, N.A.; Rowley, S. Understanding migrant-inclusive urban transitions in Australia via a ‘housing aspirations’ lens. In Migration and Urban Transitions in Australia; Nygaard, C., Rowley, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 149–171. [Google Scholar]

- Lozanovska, M. Migrant housing and urban transition futures. In Migration and Urban Transitions in Australia; Nygaard, C., Rowley, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 221–241. [Google Scholar]

- James, L.; Phibbs, P.; Rowley, S.; Slatter, M. Housing inequality: A systematic scoping review. Hous. Stud. 2024, 39, 1264–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyon, A.; Moore, T.; Crabtree, L.; Legacy, C.; March, A. The housing we need by 2050 for a sustainable and equitable future. Plan. Theory Pract. 2025, 26, 423–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.R.; Seo, B.K.; Baker, E. Housing systems, housing insecurity, and life satisfaction: A multilevel analysis of 158,765 individuals in 32 countries. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2024, 25, 914–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McShane, S.; Due, C.; Ziersch, A.; Walsh, M. Beyond shelter: A scoping review of evidence on housing in resettlement countries and refugee mental health and wellbeing. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2025, 60, 1541–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat). World Cities Report 2023: Enabling Living for All through Inclusive Urban Transformation; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2023; Available online: https://unhabitat.org/programme/inclusive-communities-thriving-cities (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Griffith, E.J.; Jepma, M.; Savini, F. Beyond collective property: A typology of collaborative housing in Europe. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2024, 24, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barenstein, J.D.; Koch, P.; Sanjines, D.; Assandri, C.; Matonte, C.; Osorio, D.; Sarachu, G. Struggles for the decommodification of housing: The politics of housing cooperatives in Uruguay and Switzerland. Hous. Stud. 2022, 37, 955–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbot, M. When the history of property rights encounters the economics of convention. Some open questions starting from European history. Hist. Soc. Res. Hist. Sozialforschung 2015, 40, 78–93. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B. Re-conceptualizing housing tenure beyond the owning-renting dichotomy: Insights from housing and financialization. Hous. Stud. 2023, 38, 1512–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillimore, J.; Goodson, L. Making a place in the global city: The relevance of indicators of integration. J. Refug. Stud. 2008, 21, 305–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdie, R.A. Pathways to housing: The experiences of sponsored refugees and refugee claimants in accessing permanent housing in Toronto. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2008, 9, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozanovska, M. Migrant Housing: Architecture, Dwelling, Migration; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M. Cultural Adaptation and Housing Choices of Migrants in Australia. Ph.D. Thesis, Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Karmaker, M. Housing pathways of Bangladeshi migrants during the process of settling in Australia. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dufty-Jones, R. A historical geography of housing crisis in Australia. Aust. Geogr. 2018, 49, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada. National Housing Strategy. 2017. Available online: https://housing-infrastructure.canada.ca/housing-logement/ptch-csd/about-strat-apropos-eng.html (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Government of Canada. Urban, Rural and Northern Indigenous Housing Strategy. 2022. Available online: https://www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/professionals/project-funding-and-mortgage-financing/funding-programs/indigenous/urban-rural-northern-indigenous-housing-strategy (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Government of Canada, Indigenous Services Canada. Funding for Unmet Indigenous Housing Projects in Urban, Rural, and Northern Areas. 2023. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/indigenous-services-canada/news/2023/06/funding-for-urgent-unmet-indigenous-housing-projects-in-urban-rural-and-northern-areas-to-be-distributed-through-the-national-indigenous-collaborat.html (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Canadian Housing and Renewal Association (CHRA), Indigenous Caucus. For Indigenous, By Indigenous: A National Housing Strategy. 2018. Available online: https://chra-achru.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/2018-06-05_for-indigenous-by-indigenous-national-housing-strategy.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Kāinga Ora Act. Section 14(1)(ii) and Section 13 Functions of Decision-Making with Māori Perspectives. 2019. Available online: https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2019/0050/latest/whole.html (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Housing New Zealand. Kāinga Ora Māori Strategy 2021–2026: Housing Aspirations for Iwi and Rōpū Māori; Housing New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand, 2021; Available online: https://coilink.org/20.500.12592/k2crn5 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Ministry of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Housing by Māori, for Māori, and with Māori. 2025. Available online: https://www.hud.govt.nz/our-focus/housing-for-by-and-with-maori (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Groot, J.; Ronald, R. Integrating refugees through ‘flexible housing’ policy in The Netherlands. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2025, 25, 806–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czischke, D.; Huisman, C.J. Integration through collaborative housing? Dutch starters and refugees forming self-managing communities in Amsterdam. Urban Plan. 2018, 3, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Improvement Service. Place-Based Investment Programme—Interim Report; Improvement Service Scotland: Livingston, UK, 2022; Available online: https://www.improvementservice.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0034/46888/Place-Based-Investment-Programme-Interim-Report.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Scottish Government. Rural and Islands Housing Action Plan. 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/publications/rural-islands-housing-action-plan/pages/8/ (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Le Galès, P.; Vitale, T. Governing the Large Metropolis. A Research Agenda; Spire Missouri Inc.: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ziersch, A.; Walsh, M.; Due, C. Housing and health for people from refugee and asylum-seeking backgrounds: Findings from an Australian qualitative longitudinal study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Housing Supply and Affordability Council (NHSAC). State of the Housing System 2025; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2025. Available online: https://nhsac.gov.au/news/release-state-housing-system-report-2025 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- New South Wales Department of Planning, Housing and Infrastructure (NSW DPI). Apartment Design Guide: Tools for Improving the Design of Residential Apartment Development; Government of New South Wales: Sydney, Australia, 2024. Available online: https://www.planning.nsw.gov.au/policy-and-legislation/housing/apartment-design-guide (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Department of Transport and Planning (Victoria). Better Apartments Design Standards; Victorian Government: Melbourne, Australia, 2021. Available online: https://www.planning.vic.gov.au/guides-and-resources/guides/all-guides/better-apartments (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Vitale, T. Regulation by incentives, regulation of the incentives in urban policies. Transnatl. Corp. Rev. 2010, 2, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omrany, H.; Al-Obaidi, K.M. Application of digital twin technology for Urban Heat Island mitigation: Review and conceptual framework. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omrany, H.; Mehdipour, A.; Oteng, D.; Al-Obaidi, K.M. The uptake of urban digital twins in the built environment: A pathway to resilient and sustainable cities. Comput. Urban Sci. 2025, 5, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Housing Australia. Housing Australia. 2025. Available online: https://www.housingaustralia.gov.au/ (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Australian Government. AIHW Housing Data Dashboard: Housing Data. 2025. Available online: https://www.housingdata.gov.au/ (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Omrany, H.; Al-Obaidi, K.M.; Ghaffarianhoseini, A.; Chang, R.D.; Park, C.; Rahimian, F. Digital twin technology for education, training and learning in construction industry: Implications for research and practice. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omrany, H.; Mehdipour, A.; Oteng, D. Digital twin technology and social sustainability: Implications for the construction industry. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).