Abstract

Urban areas across the globe face increased pressures to adapt to variations in energy demands and increased impacts of urban heat islands (UHIs). Urban form links closely to both energy consumption and microclimate, with factors such as density and sky view factors having a marked impact on wind reduction, surface temperatures, and outdoor comfort. Although both relationships have been widely studied independently, emerging research highlights important trade-offs between outdoor thermal comfort and energy performance. It also shows that the impacts of urban form vary significantly by climate and context. This has led to calls for a more standardized analysis approach, with some authors advocating for multi-objective optimization implementations. In hot climates, where UHI impacts are expected to be more pronounced under climate change, identifying trade-offs is challenging due to a lack of data covering urban morphology and energy modelling. This paper presents a standardized analysis method combining key urban morphology, microclimate, outdoor comfort, and energy indicators. The method’s potential to reveal relationships between urban form and performance indicators and its suitability for integration with multi-objective optimization are evaluated. For this purpose, a comparative analysis of three hot climate case studies is conducted: Al Fahidi (Dubai, UAE), Al Balad (Jeddah, SA), and Masdar City (Abu Dhabi, UAE). The analysis integrates spatial mapping of wind and surface temperature patterns, capturing day–night variations and interactions between three-dimensional form, spatial wind, surface temperature, and outdoor comfort patterns.

1. Introduction

In the context of current and predicted climatic changes, urban areas across the globe face increased pressures to respond and adapt to the resulting variations in energy demands and increased impacts of urban heat island (UHI) effects. UHI effects are directly linked to the morphology of urban areas, with local temperature and other climatic conditions varying greatly due to the specific material qualities, overall urban geometry, and orientation relative to sun path and prevailing winds [1,2]. Urban microclimates not only impact thermal comfort but can increase cooling loads by up to 74% [3], with urban morphology, comfort, and energy performance being closely interlinked [4].

For hot climates, models accounting for the rise in global temperatures show a significant increase in cooling energy demand [5,6], as well as a decrease in overall outdoor thermal comfort [7]. Thus, planning for and mitigating impacts on cooling energy demand and outdoor comfort are key considerations for achieving sustainable urban development in the long term.

1.1. Existing Approaches

While there is a consensus that urban form, microclimate/outdoor comfort, and energy performance are interconnected and should be concomitantly considered in urban planning and design processes, significant barriers remain in terms of establishing optimal urban form parameter ranges that improve both energy and microclimate/outdoor comfort performance. In particular, conflicting results across different studies create difficulties in generalizing findings and translating research outcomes into tangible design and policy approaches.

Approaches for tailoring urban form to improve microclimate and energy performance can be grouped into two main, intertwined research areas: coupled microclimate-energy (CME) models and spatial multi-objective optimization (SMO) approaches. CME approaches primarily focus on the relationship between energy performance and microclimate, with less emphasis on urban form, while SMO approaches place urban form in a central role, with microclimate and energy performance used as optimization objectives.

Dynamic (bidirectional) coupling used in conjunction with computational fluid dynamics (CFD) microclimate models in CME is recognized for most accurately representing the interaction between microclimate and building energy modelling parameters [3,8]. These methods, however, remain computationally intensive [3,8] with a range of CME approaches (type ii coupling approaches of Waly et al. [9] review selection) ignoring urban form parameters. Recent advances include the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning, which reduce processing times but may lack transparency in decision-making and are constrained by limitations in data availability for training models (requires large datasets), as well as spatially distributed meteorological data [10,11].

SMO approaches are design-based processes and offer more flexibility in terms of computational intensity, which depends on the complexity and formulation of the design problem. Based on a review of 94 relevant papers, Castrejon-Esparza et al. [12] highlight SMO approaches as effective tools for the design of urban forms that enhance both energy and microclimate/outdoor comfort performance. This aligns with Waly et al. [9], who also underscore the benefits of employing SMO algorithms for improved sustainable urban design and planning. Additionally, the subset of evolutionary multi-objective optimizations relies on iterative processes that allow testing of a variety of urban form scenarios based on a single input dataset [12].

The above CME and SMO reviews span extensive research on urban form–microclimate–energy relationships. Both CME and SMO literature highlight the need for standardized methods, urban form, and performance metrics. Additionally, CME literature reveals conflicting findings—both in the direction (polarity) of key relationships and in the reported magnitude of influence for specific urban-form parameters. Waly et al. [9] highlight conflicting findings in the correlation of outdoor thermal comfort and energy performance, attributing this to trade-offs between the two performance metrics. Manapragada and Natanian [8] note “non-linear and context-dependent” relationships between microclimate and urban form/fabric. Marey et al. [11] attribute conflicting findings to a lack of standardization in terms of methodologies and parameters, highlighting that the impact of urban morphology on microclimate parameters varies seasonally and is context-dependent. This also aligns with research exploring urban form-energy relationships, where a review of 54 studies by Quan and Li [13] also found conflicting results, which were attributed to differences in methodology, climate zones, urban form, and performance metrics.

Lastly, the literature reveals that hot arid climates are underrepresented in the literature, with a limited number of papers exploring implications for Bwh Koppen climate zones [9,12,13].

1.2. Study Aims and Contributions

This paper addresses some aspects of the method and parameter standardization gap by testing a hybrid multi-objective model with coupled components. The method is a novel approach that integrates a selected set of urban form and performance metrics that were highlighted as most influential and proposed as standard metrics in the literature [11,12,13]. The selection of metrics also takes real-world applications into account, tailoring outputs to match those commonly used within planning practice and policies.

The paper focuses on evaluating the potential and limitations of the proposed analysis method in terms of (1) potential to reveal relationships between urban form, outdoor comfort/microclimate, and energy; and (2) potential for integration with multi-objective optimization.

Although a consensus regarding the reasons behind past conflicting results and how the impact and magnitude of specific parameters vary is yet to be reached, the literature identifies climate zones, analysis scale, resolution, and urban typology (context) as factors that may alter the relationships between urban form and performance parameters [11,13]. These findings were considered both in the development of the method and the method test set-up presented.

The model links validated microclimate and energy simulation tools with parametric 3D modelling, combining several commonly employed tools within the 3D modelling software Rhinoceros and its integrated algorithmic modelling interface Grasshopper (see Section 2). The choice of tools matches those most frequently employed in SMO, aiming to arrive at a standardized analysis method that is compatible with SMO approaches. A proprietary script is used to align inputs (analysis periods, geometry, basic assumptions for performance metric assessment) and group analysis grids and outputs by four typologies: public squares, private courtyards, N-S canyons, and E-W canyons. The proprietary script includes semi-automated visualization components that allow for a robust comparison of the different cases and may reveal localized impacts not captured in standard indicators.

We test the proposed method using three case study sites with comparable cooling degree days (CDD) within a single Koppen climate zone. The case study sites of Al Fahidi (Dubai, UAE), Al Balad (Jeddah, SA), and Masdar City (Abu Dhabi, UAE) are located in the Koppen hot desert (Bwh) climate zone and were selected to represent a range of strategies from both traditional and modern urban configurations. The analysis areas are comparable in scale, and the sites were modelled using the same level of detail.

Overall, the paper provides the following key contributions:

- A standardized analysis method that is compatible with SMO approaches and combines relevant parameters highlighted in both CME and SMO literature.

- Additional data for the Bwh Koppen climate zone, which was identified as underrepresented in the literature.

- An evaluation of opportunities and limitations of the method in terms of its potential integration with SMO approaches and potential to reveal relationships between urban form and performance metrics.

The key methods, algorithm components, and assumptions are described in Section 2, followed by an evaluation of trade-offs and comparative analysis of the results (Section 3). Section 4 discusses the method’s advantages in relation to prior work, and Section 5 outlines limitations and future research needs.

2. Materials and Methods

To connect geometry, microclimate, energy, and comfort analysis, a proprietary script linking preexisting analysis tools has been developed. The 3D modelling software Rhinoceros v. 6 and its integrated algorithmic modelling interface Grasshopper build 1.0.0007 were used for geometry modelling and script development due to the accuracy of the 3D modelling module and the ability of Grasshopper to connect with a series of robust and time-tested analysis tools. Additionally, SMO literature highlights these platforms as most frequently utilized in conjunction with various multi-objective optimization algorithms [12].

We reviewed and ran initial tests for microclimate and energy simulation packages and selected analysis tools based on the following two criteria:

- Interface allows model expansion and can support the inclusion of water efficiency, carbon footprints, etc., in future iterations.

- Reduced calculation times to allow potential future use of the script as part of optimization algorithms.

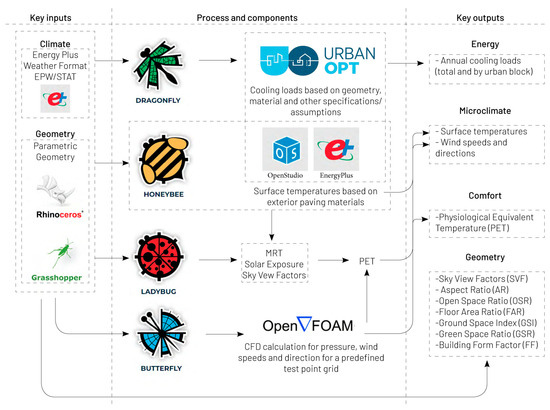

Based on these criteria, we selected the Ladybug Tools v 1.8 package, which includes both microclimate comfort and energy modelling. These tools are frequently used within multi-objective approaches [12]. Figure 1 shows a breakdown of the Ladybug subroutines, the analysis software that they connect to, and key inputs and outputs of the script.

Figure 1.

Proposed method summary showing script inputs/outputs, main Ladybug components, and analysis software for each calculation step.

For energy calculations, we utilize the EnergyPlus v 23.2 [14] via OpenStudio v 3.7.0 [15] and UrbanOpt v 0.11.1 [16] workflows, which are geared towards district-scale energy modelling and are well-established and validated calculation methods.

For comfort and microclimate analysis, we utilize the Ladybug Tools Honeybee package, which employs EnergyPlus to determine ground surface temperatures (via the Honeybee UTCI map component), and the Butterfly v. 0.0.05 package, which employs the OpenFoam (blueCFD-Core 2017-2) [17] algorithm for CFD. Mean radiant temperatures (MRT) and Physiological Equivalent Temperature (PET) values are determined using the integrated Ladybug calculations, which are based on current literature and have been shown to yield comparable results to other, more detailed but more computationally intensive software such as ENVImet [18]. As Ladybug tools offer several variants for calculating MRT, a test using the same climate file and analysis period for the Al Fahidi site was conducted using ENVImet v. 5.6.1. The Ladybug workflow outputs were compared to ENVImet results, and the workflow with outputs closest to the ENVImet result range was selected.

The proprietary part of the algorithm handles selection of the analysis period (Section 2.2), selection of geometry within the analysis area, alignment of sensor grid points across components, calculation of geometry metrics, compilation of outputs by typology, and semi-automated visualization. Visual checks were performed for each case study to ensure correct geometry selection and accurate typology-based result assignment, noting that both typology and analysis areas are defined manually. Aspect Ratio (AR) calculations use a proprietary component that calculates AR values for individual section planes along canyon or square axes, allowing manual verification. A random sample of sections was tested to validate AR outputs.

The semi-automated visualization components combine the key script outputs (Figure 1) into graphical outputs, focusing on the following four categories:

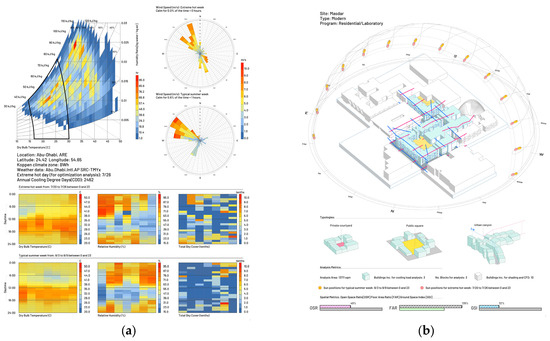

- Environmental Factors: Climate data, including annual psychrometric chart and wind, temperature, humidity, and cloud cover graphs for the extreme hot and typical summer weeks analysis periods (Figure 2a).

Figure 2. Example of script visualization outputs for (a) Environmental Factors and (b) Geometry metrics.

Figure 2. Example of script visualization outputs for (a) Environmental Factors and (b) Geometry metrics. - Geometry: Basic geometry massing, the resulting Open Space Ratio (OSR), Floor Area Ratio (FAR), Ground Space Index (GSI), orientation relative to sun path, and identification of the four urban typologies discussed. Analysis metrics such as total area, number of blocks, and buildings considered are also included (Figure 2b).

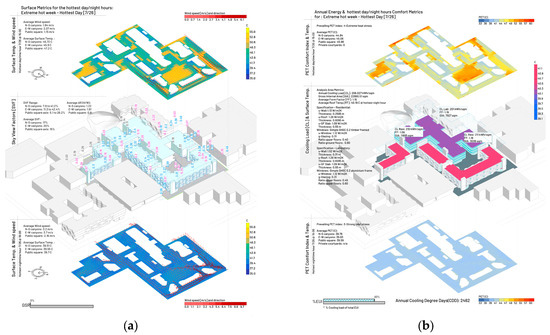

- Surface: Includes microclimate outputs and linked geometry parameters. Wind speeds (Ws), wind directions (Wd), and surface temperatures (ST) are shown for each grid point and averaged across each typology, with Sky View Factors (SVF) and AR values calculated along the main axes (Figure 3a).

- Comfort: Includes comfort, energy outputs, and linked geometry parameters. Annual cooling loads (CL) and averaged building form factors (FF) are shown for each block and averaged across the analysis region. PET is visualized for each grid point and averaged across each typology (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Example of script visualization outputs for (a) surface and (b) comfort metrics.

An initial selection of output parameters and their definitions was based on the literature review of metrics relevant for hot climates by Ottmann [19]. In the first instance, the parameter list was reduced to avoid duplicating descriptors, especially in relation to geometry metrics, where some parameters overlapped or described the same urban characteristic. Secondly, the list was adjusted to match outputs that can be delivered using less computationally intensive tools that can be used in conjunction with iterative optimization. For example, no adequate tools that can account for the impact of large water bodies or green area evapotranspiration effects were identified. As such, blue space ratios were omitted, although the impact on microclimate has been established in the literature. The resulting output lists were then checked against the classifications and standardized definitions identified by Marey et al. [11] in relation to microclimate, Quan and Li [13] in relation to energy, and Castrejon-Esparza et al. [12] in design variable and optimization fitness criteria. With the exceptions noted above, all relevant parameters were represented in the model, although not all the metrics are integrated as numeric outputs. Considering that the frameworks proposed different classifications and metric denominations, we retain nomenclatures and units of measure that are most common in practice rather than adopting the view of any particular standardization proposal.

All microclimate and comfort metrics were analyzed using a 3 by 3 m grid, with PET, ST, MRT, Ws, and Wd calculated for each grid point. Geometry metrics such as SVF and AR were calculated at the centre point of courtyards and along several points (minimum 5) of square and canyon axis lines.

For microclimate and comfort metrics, the analysis focuses on the worst-case scenario (hottest hour with the lowest wind speeds) for day and nighttime conditions during extreme hot and typical summer weeks (see Section 2.2). Cooling loads, however, are calculated on an annual basis and expressed per surface area, as these metrics are commonly used in planning policy and building regulation targets.

Section 2.1, Section 2.2, Section 2.3 and Section 2.4 introduce the case study sites and detail the specific assumptions for Environmental Factors, Surface, and Comfort categories following the grouping of the visualizations.

2.1. Case Study Sites

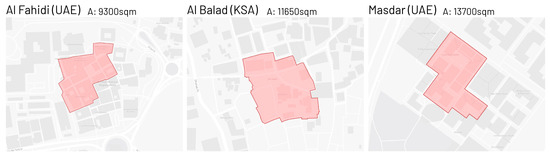

The selected site areas (Figure 4) encompass key typologies and cover urban areas of around 1 ha. The two historical sites (Al Fahidi and Al Balad) represent low- and medium-rise traditional configurations, while the Masdar site introduces modern design strategies such as raised open ground level covered by cantilevered main building volumes.

Figure 4.

Case studies, location, and analysis areas.

The geometry model for the Al Fahidi case study was based on Google, Yandex Maps, and street views, as more accurate plans were not available. Al Balad was remodelled as a massing model based on a detailed 3D survey scan of the area. Masdar was modelled based on the architect’s drawings and Google Street View, and maps. In spite of the differences in initial data, the overall level of detail of the base input geometries was aligned through the modelling process. The level of accuracy is higher for Masdar and Al Balad, but the impact on the overall geometry metrics, as well as comfort and microclimate parameters, is likely minimal (see Section 2.4 for energy implications).

2.2. Environmental Factors

Weather data was collected from the OneBuilding database [20], including the key script inputs for EnergyPlus Weather (EPW) and Expanded EnergyPlus Weather Statistics (STAT) files. For all three sites, we selected the most recent typical meteorological year data (TMY), covering the 2009–2023 period. This allows for more accurate results, as older datasets cover several decades, resulting in much lower typical air temperatures than currently experienced during the summer season.

Extreme hot and typical summer weeks data are selected from the EPW according to the periods included in the EnergyPlus STAT file. The extreme hot week is a selected week from the EPW data where temperatures are nearest to the maximum summer value. The typical summer week is a selected week from the EPW data where temperatures are nearest to the average summer value. For each week, the hottest day is first determined based on the average temperature. The script then selects the two worst-case day/night hours of the hottest extreme hot and typical summer days. The hottest hour is identified based on maximum air temperature, and, in cases where the same air temperature is experienced at multiple hours, the hour with the lowest wind speed is selected as the worst case for the analysis.

2.3. Surface

Ground materials and their properties have a significant impact on the resulting MRT and STs, further influencing PET and comfort levels. Surface temperatures are calculated for each grid point and averaged for the four typologies. Table 1 shows the key assumptions and ground material characteristics for each case study site.

Table 1.

Ground material assumptions and their properties for the three case study sites.

For Al Fahidi, the Al Mangabi stone specifications for thickness and conductivity were based on [21], with the other parameters assumed similar to brick layers described in the 2015 CIBSE Appendix A [22] material properties tables. The Al Balad site ground materials contain a mix of basalt, granite, and marble cobblestone. We utilized the average CIBSE [22] value between the three materials for each parameter. Masdar concrete paver parameters were adopted from the incorporated Ladybug/Honeybee material libraries.

2.4. Comfort

For the PET calculation, air temperatures and relative humidity are based on the EPW files, with MRT and wind speeds calculated for each of the 3 × 3 m grid points. The MRT calculation uses the Ladybug ‘Outdoor Solar MRT’ component, which applies the SolarCal model of ASHRAE-55 and the simple sky exposure method to determine MRT. The ground STs calculated in the previous step are incorporated here.

The energy calculation provides an estimate of cooling loads based on typical material build-ups and approximate window ratios. To allow for a clear comparison and identification of the impact of urban form and materiality, program types and loads other than cooling have been normalized across the case studies, although some sites include other programs such as retail, religious buildings, or laboratory buildings. As the majority of the sites are residential, we assume the same occupation and other load assumptions (e.g., equipment, lighting, etc.) based on a typical mid-rise apartment for all buildings analyzed. Table 2 summarizes the main assumptions for material build-ups and u-values for each case.

Table 2.

Building materials and u-values assumed for energy calculations in the three case study sites.

Both Al Fahidi and Al Balad use Al Mangabi stone as the main construction material. Specific construction details were not available for the Al Fahidi site; hence, the same build-up based on descriptions provided by Nyazi and Sağıroğlu [23] and Bagader and Mohamed [21] was used for both cases. The window openings in the historical buildings of Al Fahidi and Al Balad often did not include glazing. We assume a timber-framed single-glazed window with a timber shading lattice to enable comparison of cooling loads.

The Masdar site encompasses two building façade types for the residential and laboratory buildings. While build-ups are an estimate based on available plans and other online information, resulting u-values for Masdar align with values stated in the available Masdar documentation.

In terms of window openings, the Al Fahidi and Al Balad opening ratios were calculated based on typical façade photographs of each site. Masdar window openings were modelled more accurately as building plans and sections were available for this project.

As both material build-up and window orientation and sizing have a strong impact on cooling loads, Masdar cooling loads will likely be more accurate due to accurate window positioning and less variation in build-up compared to the other two cases. However, the cooling load calculations aim to provide an indication of the cooling load order of magnitude rather than precise values. This is a common limitation of performing energy assessments on a large scale, where it is not possible to model precise build-ups and/or detailed window placements for each individual building.

3. Results

The proprietary script described above was tested on the three cases, yielding a range of data that can help establish correlations and inform design strategies to increase outdoor thermal comfort and decrease energy consumption. The following results summary is divided based on the four categories of data generated.

3.1. Climate and Design Conditions

Based on the EPW and STAT file inputs, the script selected the worst-case day and night hours during the hottest day of the extreme hot and typical summer weeks. Table 3 shows dry bulb air temperatures (T), relative humidity (RH), cloud cover (Cc), and wind speeds (Ws) for the dates and times analyzed.

Table 3.

Climatic conditions for selected worst-case day and night analysis hours and weekly averages for extreme hot and typical summer weeks. The hottest night hours are highlighted in grey.

Of the three sites, Al Fahidi has the most challenging climatic conditions, having the highest temperatures and lowest wind speeds, followed by Masdar and Al Balad. In terms of average weekly temperatures, the sites have comparable climates with a maximum 4 °C difference in the extreme hot week temperatures, comparable overall humidity range, cloud cover, and wind speeds. The selected worst-case scenario hours, however, show a much larger variation, with approximately 7 °C difference between the worst-case day temperature of Al Balad and that of Al Fahidi. Both Al Fahidi and Masdar experience low relative humidity outside of the typical 40–60% comfort range. The lowest overall wind speeds are recorded for Al Fahidi, with no wind in Al Balad’s worst-case hour of the typical week.

Design conditions typically take mean dry bulb temperatures into account. It is, however, important to understand the range of conditions experienced. As seen in Table 3, worst-case temperatures in both the extreme hot and typical summer weeks exceed the average by up to 9.4 °C. Considering that the typical week is representative of the summer season, a similar difference (between 2 and 9.4 °C over average) throughout the summer months could lead to a significant increase in cooling load and reduction in outdoor comfort compared to a design scenario based on averages. Conversely, considering worst-case scenario conditions at the design phase may lead to an increase in performance throughout the hot season.

While air temperatures during the day can be higher in the typical week, the nighttime temperature is consistently lower, indicating more effective radiative cooling in the typical summer weeks and prolonged uncomfortable conditions in the extreme hot week. The following analysis of surface and comfort metrics (Section 3.3 and Section 3.4), therefore, focuses on the extreme hot week as the worst-case scenario.

3.2. Geometry Metrics

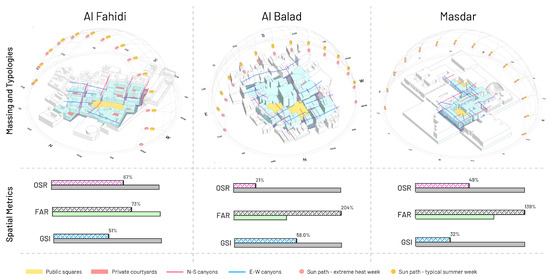

In terms of geometry configurations, the three sites represent different urban morphologies. The historical neighbourhoods encompass a large number of buildings (40 in Al Fahidi and 70 in Al Balad), while Masdar only includes 3 buildings with very large footprints. Height regimens also vary, from 1 to 2 storeys (up to 8 m in total) for Al Fahidi to a mix of buildings with 1–7 storeys (up to 34 m) for Al Balad, and 4-storey (15 m) buildings in Masdar. All three sites include public square, N-E, and E-W canyon typologies, with a preponderance of private courtyards in Al Fahidi, a single courtyard in the Al Balad analysis area, and no courtyards for Masdar. In all three cases, orientation relative to the sun path impacts canyon length, with shorter, more exposed E-W canyons and longer N-S canyons. Figure 5 shows the main massing for each case, alongside key typologies, orientation, and geometry/spatial metrics outputs.

Figure 5.

Geometry massing, orientation, typologies, and spatial metrics for each case study.

The spatial ratios analyzed (FAR, GSI, OSR) are linked to urban density and indirectly influence both outdoor comfort and cooling loads through their impact on urban form. Commonly used to describe morphology in urban planning, the combination of FAR, GSI, and OSR determines SVFs and ARs, which in turn affect the degree of daytime solar exposure and capacity for night radiative cooling. Higher FAR, GSI, and lower OSRs indicate denser contexts, which can have both positive and negative impacts on UHI effects [24] and energy consumption [25]. Positive impacts may include increased daytime shading and more compact building shapes with lower energy consumption, while negative impacts may include reduced night radiative cooling, wind speeds, and increased air pollution. From an economic and livability perspective, higher FAR and OSR are often preferred. An ideal scenario, therefore, would entail achieving the highest FAR and OSR while maintaining a positive correlation with outdoor comfort and a negative correlation with cooling load.

Of the three sites, Al Fahidi has the lowest FAR (0.73) and highest OSR (67%), followed by Masdar with a high FAR (1.39) and medium OSR (49%), and Al Balad with the highest FAR (2.04) and lowest OSR (21%).

In terms of GSI, UN-Habitat recommends 45–50% or above public open space cover [26], equivalent to 50-55% or below GSI. The Al Fahidi site falls within the recommended range, with Al Balad slightly over at 58% and a very low 32% GSI in Masdar. The combination of high FAR, medium OSR, and very low GSI in Masdar highlights the impact of the reduced ground building footprints achieved by elevating the main building volumes. This is a key feature of the Masdar design, which not only improves OSR but also has a positive impact on wind speeds and shading (see Section 3.3 and Section 3.4).

3.3. Surface Metrics

To understand the correlations between PET results and urban form, we explore the impact of urban geometry via density on wind and via SVF and AR on surface temperatures first. The SVF and AR account for building height regimens, canyon, and square widths. Table 4 summarizes results by typology for each case study.

Table 4.

Average day and night surface temperature (ST) and wind speed (Ws) in relation to sky view factor (SVF) and aspect ratios (AR) by urban typology. Nighttime values are highlighted in grey.

Overall, Al Fahidi experiences the highest STs, with a maximum of 59.5 °C in the public square during the extreme hot week. Masdar experiences the lowest STs, with ground surfaces up to 6.6 °C and 12.2 °C cooler compared to Al Balad and Al Fahidi, respectively. The difference between the vernacular cases is smaller, with Al Balad surfaces 2.7 and 5.7 °C cooler in N-S and square areas and 0.3 and 2.7 °C hotter for E-W canyons and courtyards. The largest differences across all cases occur in the public square, which is the most exposed to solar radiation. Both Al Fahidi and Masdar show increased surface temperatures in the typical week, which is likely due to decreased cloud cover (Al Fahidi) and increased air temperature (Masdar).

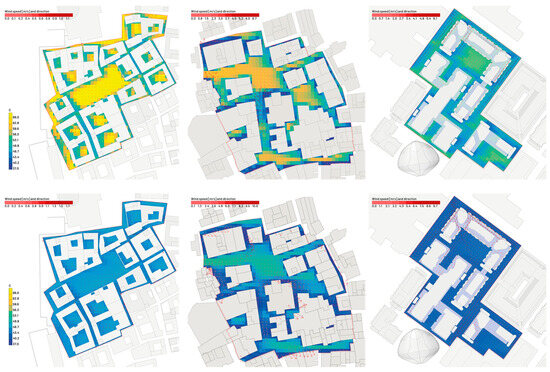

In terms of individual typologies, for the traditional cases, during daytime, there are much larger variations in surface temperature with canyons and courtyards up to 14 °C cooler than the main public squares. At night, however, there is a much smaller (up to 5 °C) difference, indicating more effective night radiative cooling in the squares. Interestingly, the Masdar site does not show similar variation, with a mere 1–2 °C variation between typologies for both day and night. This highlights the impact of the shading strategy and open ground floor design. For all cases, the N-S canyon has lower temperatures than E-W, reflecting the impact of orientation relative to the sun path. The reduced E-W canyon lengths, therefore, have a positive impact by limiting canyon areas with high solar exposure. Figure 6 shows the spatial distribution of ST, wind speeds, and directions for the hottest day and night hours of the extreme hot week.

Figure 6.

Extreme hot week spatial distribution of hottest day (top) and night (bottom) hour surface temperatures, wind speeds, and directions. Al Fahidi, Al Balad, and Masdar cases from left to right.

ARs and SVFs are some of the most relevant urban form metrics that link directly to solar exposure and STs. A higher AR (height-to-width ratio) indicates more shading due to greater building heights, a plus for daytime heat reduction. This also correlates with lower SVFs, which may inhibit nighttime radiative cooling. In Al Balad, although N-S canyons are narrower than E-W, the key impact for shading is due to the vertical configuration with higher AR resulting in temperature reductions. The SVF is closely interlinked with AR and needs to be balanced out with day and nighttime impacts, as a low SVF is generally beneficial during the day but may prevent heat from dissipating at night. This effect is evident for the historical sites, where the public squares with high SVF experience both the highest temperatures during the day and the most pronounced cooling at night. The Masdar site introduces an alternative solution, having the lowest ST, SVF, and the highest AR for the public square typology. Opposed to traditional configurations, the open ground floor, narrow upper canyon levels, and covered public square areas provide both ample space (ground floor width), shading, and increased wind access. This indicates that high AR public squares can perform well when coupled with low GSI and SVF.

Average wind speeds in all cases are lower than the initial conditions in Table 3. Wind speeds are lowest in Al Fahidi, followed by Al Balad and Masdar. For all cases, the greatest speed reductions are felt in the square areas. This is likely due to the lack of Venturi effect. Based on the simulation results for the Al Balad no wind scenario, we estimate an error margin of approximately 0.3 m/s, equivalent to 6.5% of the average of all the initial wind speeds. Table 5 shows the reduction relative to the initial speed for each of the calculated values. We find that, at the given initial speeds, the relative reduction percent depends linearly on initial speed, with an average absolute deviation well below the 6.5% error limit for Al Balad and Al Fahidi. Masdar shows a slightly higher deviation, but several data points are not applicable in this case.

Table 5.

Relative wind speed reduction (Rr) percentage and absolute deviation based on initial and calculated wind speeds (m/s) by typology. Nighttime values are highlighted in grey.

These findings highlight the strong wind speed reduction impact of dense vernacular contexts, with comparable 80% and 82% average relative reduction in Al Balad and Al Fahidi. The decreased ground floor footprint, as well as curved ground floor geometries in Masdar, have a marked positive impact, with an average relative reduction of only 59%. Given the low SVF in Masdar, this is a critical aspect that enables night radiative cooling.

3.4. Comfort Metrics

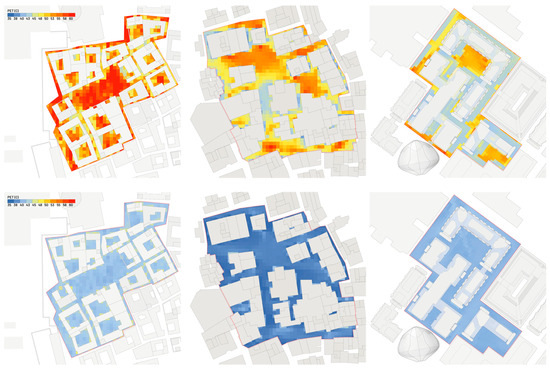

Using the above ST and wind speeds, PET was calculated and averaged by typology, as shown in Figure 7 and Table 6. Overall, PET comfort values align with ranges identified in other studies focusing on Bwh climates and traditional settlements. Mahdavinejad et al. [27] explore courtyard typologies in a Bwh climate type, showing a similar range of values to those in the Al Fahidi site. Matallah et al. [28] perform calculations for a historical site with similar climatic conditions to Al Balad, with results showing a similar range of PET values as those identified in this study. While these comparisons provide a rough confirmation, in future work, we aim to validate these results through field-testing.

The Al Fahidi site is the least comfortable, followed by Al Balad and Masdar, with extreme hot average daytime PET of 52 °C, 48 °C, and 46 °C, respectively. Al Balad had the lowest nighttime average PET, with extreme hot nighttime average PETs of 36 °C, 40 °C, and 41 °C for Al Balad, Masdar, and Al Fahidi, respectively. While Al Balad had the most favourable initial conditions, the Masdar site configuration yields better comfort levels, considering higher initial temperature and lower wind speeds.

Figure 7.

Extreme hot week spatial distribution of the hottest day (top) and night (bottom) hour PET. Al Fahidi, Al Balad, and Masdar cases from left to right.

The day/night PET difference is significant and, in the extreme hot week, shows an average drop of 12, 11, and 6 °C for Al Balad, Al Fahidi, and Masdar. In the typical week, this difference increases to 16, 14, and 12 °C. This underlines that extreme hot periods are not simply defined by punctual peaks but are characterized by prolonged heat periods that do not allow for adequate nighttime cooling.

Table 6 explores the relative outdoor comfort performance for each case study and typology. Calculated PET values are compared to initial air temperatures to determine the percent of perceived temperature rise or fall. During the hottest daytime hours of the extreme hot week, all three case studies show a perceived increase in temperature. Perceived temperature increase is above 12% for both vernacular cases, with Al Balad exceeding that of Al Fahidi. Masdar performs exceedingly well, with all daytime perceived increases below 5%. During the hottest nighttime hours of the extreme hot week, all sites show decreases in perceived temperature of up to 6%, 4.8% and 5.7% for Al Fahidi, Al Balad, and Masdar. The average across typologies and day/night conditions in the extreme hot week shows that Masdar is the only case study that has an overall 1.3% perceived decrease in temperature, while Al Balad and Al Fahidi show increases of 11.6% and 5.6%. Both Al Balad and Al Fahidi had worst initial conditions in the typical week (less cloud cover and less wind), with perceived temperature increase rising by 0.9% and 4.2%. Masdar, however, shows improvements in the typical hottest hours, with perceived temperature decreasing by 1.2%. This underscores the value of considering worst-case design scenarios and the additional gains that can be achieved in the typical summer season when conditions are more favourable.

Table 6.

PET and percent perceived increase or decrease in temperature (R+) compared to initial dry bulb temperatures (T) by typology. Nighttime values are highlighted in grey.

Table 6.

PET and percent perceived increase or decrease in temperature (R+) compared to initial dry bulb temperatures (T) by typology. Nighttime values are highlighted in grey.

| Case and Typology | Al Fahidi | Al Balad | Masdar | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | PET | R+ | T | PET | R+ | T | PET | R+ | ||

| Hottest hour of extreme hot week | N-S | 45 | 50.5 | 12.2% | 38.2 | 44.9 | 17.5% | 44 | 44.8 | 1.8% |

| E-W | 50.4 | 12.0% | 49.5 | 29.6% | 45.0 | 2.3% | ||||

| Sqr. | 56.7 | 26.0% | 50.5 | 32.2% | 46.0 | 4.5% | ||||

| Crt. | 51.5 | 14.4% | 47.0 | 23.0% | n/a | |||||

| N-S | 43 | 40.9 | −4.9% | 37.2 | 35.4 | −4.8% | 42 | 39.8 | −5.2% | |

| E-W | 41.1 | −4.4% | 36.4 | −2.2% | 39.8 | −5.2% | ||||

| Sqr. | 40.4 | −6.0% | 36.4 | −2.2% | 39.6 | −5.7% | ||||

| Crt. | 41.0 | −4.7% | 37.0 | −0.5% | n/a | |||||

| Average | 5.6% | 11.6% | −1.3% | |||||||

| Hottest hour of typical summer week | N-S | 43.8 | 50.6 | 15.5% | 40 | 49.3 | 23.3% | 45.4 | 46.7 | 2.9% |

| E-W | 52.7 | 20.3% | 50.0 | 25.0% | 46.1 | 1.5% | ||||

| Sqr. | 56.8 | 29.7% | 56.3 | 40.8% | 47.4 | 4.4% | ||||

| Crt. | 52.8 | 20.5% | 50.5 | 26.3% | n/a | |||||

| N-S | 40 | 39.4 | −1.5% | 37 | 34.7 | −6.2% | 38 | 35.0 | −7.9% | |

| E-W | 39.4 | −1.5% | 36.7 | −0.8% | 35.0 | −7.9% | ||||

| Sqr. | 38.8 | −3.0% | 36.2 | −2.2% | 34.9 | −8.2% | ||||

| Crt. | 39.4 | −1.5% | 34.7 | −6.2% | n/a | |||||

| Average | 9.8% | 12.5% | −2.5% | |||||||

The results of the annual cooling load calculation are shown in Table 7 alongside relevant geometry and climate parameters. In terms of cooling loads, Masdar performed best at an estimated 206 kWh/sqm per year, followed by Al Balad at 226 kWh/sqm per year and Al Fahidi at 320 kWh/sqm per year. The differences can be attributed to multiple factors, the most important of which are climate/microclimate, building FF, and material specifications.

Table 7.

Cooling degree days (CDD), annual cooling loads (CL), gross internal areas (GIA), and form factors (FF) for each case.

In terms of initial climate differences, Al Fahidi has the highest CDD at 2634 CDD, with Al Balad having 138 and Masdar having 172 fewer CDD. Additionally, FF affects energy consumption with lower FF, generally leading to lower energy consumption. Among the three cases, Masdar had the lowest FF (1.2), followed by Al Balad (1.5) and Al Fahidi with a more than double FF ratio of 3.3. Considering that the two vernacular sites were modelled with the same material specification, the large difference in energy performance cannot solely be attributed to the additional CDD. FF therefore contributes to the poor energy performance of Al Fahidi. The Masdar case utilizes modern material build-ups (inc. insulation and good performance windows) which, in conjunction with the low FF and successful reduction in microclimate impacts, lead to a reduction in cooling loads. Comparison with the Al Balad case is most relevant, as the difference in climate is only 34 CDD. Therefore, the performance increase in Masdar can be attributed almost entirely to improved materials, FF, and microclimate impact reduction.

While there is little data regarding cooling loads for historical buildings, measured data for the Masdar residential buildings were available for the year 2015, showing an overall energy demand (including cooling) of 237.17 kWh/sqm (see Lee et al. Masdar Institute buildings 1A and 1B [29]). This aligns with our calculations, as the cooling load was estimated at around 83% of the total energy demand.

4. Discussion

The analysis above reveals complex interactions between urban form, microclimate, and energy demands. Urban morphology impacts microclimate and overall thermal comfort, creating opportunities for reducing UHI effects through factors such as orientation, density, SVF, and AR. This has a direct effect on cooling demands, which can be reduced or increased depending on the performance of the geometry configuration in mitigating UHI effects. The use of materials with high thermal performance in conjunction with more compact building shapes can further decrease cooling loads. To achieve the best outcomes, urban designs should consider energy consumption and outdoor comfort concomitantly. Additionally, the analysis of worst-case climatic conditions indicates that urban designs for heat mitigation that respond to worst-case scenarios, such as extreme hot week conditions, can have a magnified impact throughout the entire summer season, where initial conditions are more favourable.

Based on the case study analysis, in relation to microclimate, the geometries of principal typologies should be treated differently. For canyons, the comparative analysis highlights that traditional strategies for reducing E-W canyon width are only marginally effective when not coupled with a high AR, implying that greater height variation and regimens are beneficial for reducing UHI effects. This can also aid in reducing cooling loads, as verticality also implies higher FAR and implicitly lower FF, but should be considered in relation to outdoor nighttime radiative cooling performance. Additionally, the strategy of increased canyon widths at ground floor with narrow upper-level sections applied in the Masdar case proved most efficient in reducing UHI impacts while contributing to an increase in OSR. All three cases exhibit shorter E-W canyons, a strategy that helps reduce areas of high solar exposure.

For public squares, the requirements for open space result in decreased daytime comfort levels but increased nighttime cooling capacity. The daytime impacts can be balanced through higher AR, lower SVF, and wind-catching designs. While traditional public square configurations, such as those seen in Al Fahidi and Al Balad, are effective for nighttime cooling, PET values during the day are excessively high, limiting the use of the space. The Masdar example provides an interesting solution through its raised upper floor volumes, curved ground floor building shapes, and partially covered square areas. The configuration leads to a low SVF, which improves PET during the day and maximizes the use of wind for cooling. Compared to the historical cases, the low GSI and curved building shapes help mitigate the reduction in initial wind speeds, which is essential for maintaining day PET levels and for enabling adequate nighttime cooling, otherwise difficult to achieve given the low SVF. In terms of energy consumption, the analysis highlights the marked impact that combined material performance, FF, and UHI mitigation measures can have on cooling loads. Reduced FF is linked to FAR and overall urban density, and, in conjunction with the verticality aspects discussed above, the results suggest that denser contexts can have positive impacts on both cooling loads and UHI effect mitigation. These aspects should, however, be considered in relation to the resulting GSI and OSR to decrease trade-offs with PET and comfort.

While planning policy often prescribes energy performance targets, OSR, FAR, or GSI ratios, metrics such as SVF or AR, and outdoor comfort performance criteria are generally omitted, with little consideration given to the different urban typologies. The proposed method could be applied to determine overarching context- and typology-based strategies. Analyses of vernacular cases can be employed to explore retrofit options for existing sites, but successful strategies such as the narrow canyon widths and reduced E-W canyon lengths can also inform new designs. The Masdar case study sets a good example for how such strategies might be adapted to the altered requirements, socio-economic conditions, and use of different typologies in modern contexts. The modern requirements for providing vehicular access especially limit possible canyon widths. In the case of Masdar, vehicular access is provided at an underground level, with pedestrian-only access above. Alternative options may consider networks of walkable areas, vertical layering of urban functions, mobility, and infrastructure.

4.1. Method Potential-Revealing Trade-Offs and Interactions

Overall, the method implementation test showed promising results that align with other research findings. The preliminary comparative analysis conducted in this paper revealed several interactions between urban form, microclimate, comfort, and energy consumption. Compared to other studies [25,30,31] that use similar tools and workflows, the method provides a more detailed approach to microclimate impacts via wind and surface temperature analysis, a standardized approach that could be implemented in both retrofit and new design scenarios, and a compact but comprehensive set of urban form metrics.

Murathan and Manioğlu [25] develop several hypothetical urban block configurations at a slightly smaller scale (60 × 60 m analysis area) and use a coarser 10 × 10 m grid for outdoor comfort assessment. The study focuses on assessing the impact of different densities, considering FAR, road widths, window ratios, and building typology for geometry parameters and Universal Thermal Comfort Index (UTCI) and total energy use intensity (EUI) as performance criteria.

Abdollahzadeh and Biloria [30] develop a series of hypothetical urban geometries encompassing a larger area with six 200 m2 building blocks and a 16-metre road and sidewalk area. A finer 2 × 2 m grid is used to evaluate outdoor comfort, but this is limited to a 20-metre-long strip of street. Performance criteria include PET for outdoor thermal comfort and cooling and heating loads for energy. Urban form indicators consider building program and typology, urban grid rotation, AR, and window ratios.

Bian et al. [31] introduce a multiscale approach that integrates mesoscale and urban block scale analysis. Performance criteria at the mesoscale included land surface temperature and UHI intensity, while the block scale employed total EUI, cooling load, UTCI, and daylight autonomy. The study includes multiple urban form indicators, of which FAR, SVF, AR, and compactness are completely aligned with our study. Indicators for building density, height, footprint, site coverage, and orientation have a slightly different plot-by-plot approach to describing the geometry. Additional parameters that are not included in our study are vegetation cover ratios and material albedos.

In terms of performance criteria, both energy and outdoor comfort metrics at the block scale align between the present and reference studies. Given the focus on hot climates dominated by cooling loads, heating loads were omitted in our study, as the contributions to the total EUI are minimal. Although two of the reference studies utilize UTCI for outdoor comfort, both PET and UTCI are well-established metrics for outdoor comfort evaluation.

Geometry metrics vary greatly, with the approach proposed by Bian et al. [31] aligning more closely with our study. The plot-by-plot approach, while equivalent to the present study, places emphasis on building character rather than overall urban configuration, increasing the number of urban form parameters. The proposed method provides a more concise description of the overall urban conditions while considering the same building features, and may be more easily accessible to broader audiences, such as policy and decision-makers. The other two reference studies [25,30] focus on particular aspects of urban geometry but ignore key parameters such as SVF, which was identified as one of the more influential geometry indicators in the review by Marey et al. [12]. The studies, therefore, do not integrate a holistic view of how urban form impacts outdoor comfort and energy performance.

The key advantages of the proposed method are the integration with CFD and spatial mapping of Ws, Wd, ST, and SVF, as well as the distinction between key urban typologies. The reference studies utilize the Urban Weather Generator tool to modify EPW climate input data and represent the urban microclimate. However, the tool is a highly simplified model that does not generate spatial data. Bian et al. [31] use a similar workflow to generate STs, but the results are not analyzed spatially and form an intermediary step rather than a key output. Furthermore, none of the three studies distinguishes between day and night patterns or different typologies (e.g., canyons, squares, courtyards), with SVF and other factors expressed as averages for the entire analysis area.

The results of this study show that the relationships and impacts on wind, ST, and PET vary greatly between day and night and across typologies. This is supported by recent reviews that identify conflicting previous findings, highlighting that polarity and influence magnitude are context-dependent [9,11,13]. The proposed method, therefore, integrates an additional level of detail, which should enable robust analyses of the complex relationships between three-dimensional urban form, microclimate, outdoor comfort, and energy performance. Additionally, spatial visualization of wind and ST data allows for identifying impacts of specific geometry features that may not be captured in the standardized metrics. An example is the wind impact of Masdar’s rounded ground-level geometry. A limitation of this detailed approach is that wind CFD and ST results could not be integrated with the energy analysis due to the large timeframe (annual calculation), number of sensor grid points, and associated computational intensity. While context shading and materiality are considered in the energy calculation, UHI impacts on air temperature and wind speeds are not yet linked with the energy outputs.

The test implementation of the method for the three case studies allowed for identifying general patterns and design strategies. However, the punctual nature of the case study approach makes it difficult to quantify polarities and impact magnitudes for each parameter. A larger dataset of case studies or hypothetical configurations based on each case would be required to enable analyses such as the linear regressions included in the reference studies. The density metrics (FAR, GSI, OSR) provide a clear example, where each case has a single output value. Given the data availability issues for the Bwh region, where large areas are missing basic geometry data, the method was tailored for integration with SMO approaches, which could be used to generate hypothetical scenarios, thereby diversifying and expanding the output database.

4.2. Method Potential Integration with Multi-Objective Optimization

Waly et al. [9] propose an integrated framework where multi-objective optimization is used to manage trade-offs, improve outdoor comfort, and improve the energy performance of urban designs. Microclimate modelling is, however, complex and computationally intensive, making such approaches challenging to implement in day-to-day practice. Comparatively, the interlinked urban morphology metric calculations are far less intensive and can be understood by a broader range of decision-makers. Given the strong linkage between morphology, energy, and comfort performance, there is an opportunity for optimization algorithms to focus on identifying optimal target ranges for the most relevant geometry parameters.

This links in with data availability issues noted in previous sections and provides opportunities to test various design configurations based on a single real-world data input scenario (e.g., climate and original geometry). Iterative optimization algorithms, such as genetic algorithms, are tailored for multi-objective problem-solving and generate a diverse range of intermediary solutions. Iterative SMO approaches can, therefore, be used to generate a bigger dataset of PET, cooling load, and microclimate parameter linkage examples that allow correlation and regression analysis. For example, the perceived temperature change percentages utilized to compare PET results for the three case studies could be stored at each iteration alongside the geometry metrics discussed in this paper. Correlation or regression analysis could then be conducted on an adequately sized dataset.

Several simplifications have been implemented to reduce complexity and computation times. This is a limitation in terms of data output accuracy, but the approach should enable the integration of the model with iterative SMO algorithms. Additional aspects that should be considered include the formulation of the design problem and the selection of fitness criteria. Depending on the context and whether the application aims to identify solutions for retrofit or new designs, formulating the design problem may require extracting additional geometry information from the case studies. This may include averaging canyon lengths, widths, and orientations, defining building height or footprint ranges to inform the development of a typical block for optimization. As suggested by Castrejon-Esparza et al. [12], the approach for determining simulation parameters should also be defined.

For any subsequent regression and correlation analyses that may be used to establish parameter ranges for policy and design recommendations, the grouping and resolution of the data should first be tested. While the script can output detailed data for each of the 3 × 3 grid cells, it is possible that utilizing the data generated along canyon and square axes or the overall typology averages will yield clearer results (e.g., less noise and cleaner data) in the context of regression analysis. At the same time, testing should be conducted to evaluate whether day, night, hot, and typical week data should be analyzed separately. Similarly, regression and correlation applied to different cases within the same Koppen climate zone should be compared to identify if the relationship polarity and intensity vary when applying a standardized analysis method.

5. Limitations and Future Work

The key limitations of the method revolve around: simplifications used to reduce calculation times and permit form impact assessment; omission of some parameters that cannot currently be modelled using computationally efficient tools; and qualifying the relationships between form and performance metrics.

Model simplifications refer to the energy calculations, where loads other than cooling are assumed equal for all buildings, window placements have been approximated, and typical material build-ups are applied. While these measures aim to facilitate a robust analysis of the impact of urban form, they also entail less accurate numeric results. Furthermore, due to the computational intensity of the process, the detailed CFD and surface temperature results are not yet integrated with the energy model. The numerical cooling loads presented in the study should therefore be interpreted as indicative of the order of magnitude and not precise demand values.

Two key parameters, which are known to impact outdoor comfort and microclimate, have been omitted from this study. The impact of water bodies was not considered or included as an indicator (e.g., blue ratio). This is due to the fact that no computationally efficient tools that could model these impacts were identified. Green space ratios and impacts of vegetation are omitted in this study, as none of the cases included significant areas of vegetation. The model can, however, account for the shading impact of trees, with a green space ratio indicator calculator included in the script. No computationally efficient tools that account for the evapotranspiration impacts of vegetation were identified.

While the method employs validated calculation methods for each performance and microclimate indicator, there was limited data availability for the Bwh climate zone. In some instances, it was not possible to verify outputs against other research studies or field data capturing actual energy consumption, spatial wind, or surface temperature results for the case studies. Future work will, therefore, include further output validation using field-testing.

The proprietary script developed for case study analysis provides a good basis for comparison, having already allowed for preliminary identification of relationships and trade-offs. To qualify relationships, however, a larger dataset that is suitable for analyses like regression or correlation is required. Future research will therefore focus on the integration of the analysis script with optimization algorithms to generate an appropriately sized hypothetical urban form configuration dataset. Based on this expanded dataset, analyses such as regression and correlation can be applied to identify target ranges, polarities, and impact magnitudes for each urban form indicator.

6. Conclusions

This study presents a standardized analysis method combining urban morphology metrics, validated microclimate and energy simulation tools, and typology-specific spatial analysis to examine how urban form affects outdoor comfort and energy performance in hot climates. The method was tested on two vernacular and one modern case study in the Bwh Koppen climate zone, with a focus on evaluating its potential to reveal form–performance relationships and its suitability for integration with multi-objective optimization.

Unlike prior approaches that focus on individual geometry parameters or produce averaged metrics, this method integrates CFD-based wind and surface temperature spatial mapping and typology-specific analysis, capturing day–night variations and detailed interactions between three-dimensional urban form, outdoor comfort, and cooling energy demand.

A comparative analysis of the urban form, microclimate, outdoor comfort, and energy parameters of the three cases revealed that urban typologies such as canyons, squares, and courtyards should be addressed separately due to the varying impact of urban form factors. Several design strategies and trade-offs between daytime and nighttime impacts of the six urban form indicators were identified across the four typologies.

Future work could use the proposed analysis method, which is tailored for and suitable for integration with SMO, to further qualify the magnitude and polarity of form-performance indicator relationships. Iterative approaches, such as genetic algorithms, could be leveraged to produce larger datasets suitable for regression and correlation analysis for sites with limited data availability. Careful grouping by typology, temporal resolution, and site context will support regression analyses that could inform evidence-based design guidance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.C.G. and D.A.O.; methodology, I.C.G. and D.A.O.; software, I.C.G.; validation, I.C.G.; formal analysis, I.C.G.; data curation, I.C.G.; writing—original draft preparation, I.C.G.; writing—review and editing, I.C.G. and D.A.O.; visualization, I.C.G.; supervision, D.A.O.; project administration, I.C.G. and D.A.O.; funding acquisition, D.A.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by Zayed University: Activity Code: R21105; Bond University, Faculty of Society and Design: Article Processing Charge (APC).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Fernanda Parnenzini and Byron Runde for their assistance with creating the 3D geometry models for the Al Balad and Masdar sites.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Deilami, K.; Kamruzzaman, M.; Liu, Y. Urban Heat Island Effect: A Systematic Review of Spatio-Temporal Factors, Data, Methods, and Mitigation Measures. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2018, 67, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Xu, X.; Huang, W.; Zhang, R.; Kong, L.; Wang, X. A Multi-Objective Optimization Framework for Designing Urban Block Forms Considering Daylight, Energy Consumption, and Photovoltaic Energy Potential. Build. Environ. 2023, 242, 110585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezer, N.; Yoonus, H.; Zhan, D.; Wang, L.; Hassan, I.G.; Rahman, M.A. Urban Microclimate and Building Energy Models: A Review of the Latest Progress in Coupling Strategies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 184, 113577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzabeigi, S.; Razkenari, M. Design Optimization of Urban Typologies: A Framework for Evaluating Building Energy Performance and Outdoor Thermal Comfort. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 76, 103515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutty, N.A.; Barakat, D.; Darsaleh, A.O.; Kim, Y.K. A Systematic Review of Climate Change Implications on Building Energy Consumption: Impacts and Adaptation Measures in Hot Urban Desert Climates. Buildings 2023, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khourchid, A.M.; Al-Ansari, T.A.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Cooling Energy and Climate Change Nexus in Arid Climate and the Role of Energy Transition. Buildings 2023, 13, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matallah, M.E.; Mahar, W.A.; Bughio, M.; Alkama, D.; Ahriz, A.; Bouzaher, S. Prediction of Climate Change Effect on Outdoor Thermal Comfort in Arid Region. Energies 2021, 14, 4730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manapragada, N.V.S.K.; Natanian, J. Urban Microclimate and Energy Modeling: A Review of Integration Approaches. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waly, N.M.; Hassan, H.; Murata, R.; Sailor, D.J.; Mahmoud, H. Correlating the Urban Microclimate and Energy Demands in Hot Climate Contexts: A Hybrid Review. Energy Build. 2023, 295, 113303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Bibi, S. Advancements in Coupling Strategies for Urban Microclimate and Building Energy Models. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 218, 115790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marey, A.; Zou, J.; Goubran, S.; Wang, L.L.; Gaur, A. Urban Morphology Impacts on Urban Microclimate Using Artificial Intelligence—A Review. City Environ. Interact. 2025, 28, 100221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrejon-Esparza, N.M.; González-Trevizo, M.E.; Martínez-Torres, K.E.; Santamouris, M. Optimizing Urban Morphology: Evolutionary Design and Multi-Objective Optimization of Thermal Comfort and Energy Performance-Based City Forms for Microclimate Adaptation. Energy Build. 2025, 342, 115750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, S.J.; Li, C. Urban Form and Building Energy Use: A Systematic Review of Measures, Mechanisms, and Methodologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 139, 110662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawley, D.B.; Lawrie, L.K.; Pedersen, C.O.; Winkelmann, F.C. EnergyPlus. Ashrae J. 2000, 42, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmetti, R.; Macumber, D.; Long, N. OpenStudio: An Open Source Integrated Analysis Platform; NREL: Golden, CO, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- El Kontar, R.; Polly, B.; Charan, T.; Fleming, K.; Moore, N.; Long, N.; Goldwasser, D. URBANopt: An Open-Source Software Development Kit for Community and Urban District Energy Modeling; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2020; NREL/CP-5500-76781. Available online: https://docs.nrel.gov/docs/fy21osti/76781.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Jasak, H. OpenFOAM: Open Source CFD in Research and Industry. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2009, 1, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, Y.I.; Kershaw, T.; Shepherd, P. A Methodology For Modelling Microclimate: A Ladybug-Tools and ENVI-Met Verification Study. In Proceedings of the Planning Post Carbon Cities: 35th PLEA Conference on Passive and Low Energy Architecture, Coruna, Spain, 1–3 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ottmann, D.A. Oasis by the Sea: Design Matrix for Shaping Microclimates in Hot Coastal Cities. In Amphibious Concepts at the Edge of the Sea; Baumeister, J., Giurgiu, I.C., Ottmann, D.A., Eds.; Cities Research Series; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 163–190. ISBN 978-981-96-0356-5. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrie; Linda, K.; Drury, B. Crawley Development of Global Typical Meteorological Years (TMYx). Available online: https://climate.onebuilding.org/ (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Bagader, M.; Mohamed, M. A Comparison Study for the Thermal and Physical Properties between “Al-Mangabi” and the Available Building Materials for the External Walls in Jeddah. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2020, 13, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIBSE. Guide A Environmental Design; Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nyazi, G.; Sağıroğlu, Ö. The Traditional Coral Buildings of the Red Sea Coast: Case Study of Historic Jeddah. Gazi Univ. J. Sci. Part B Art Humanit. Des. Plan. 2018, 6, 159–165. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, L.; Liao, W.; Li, P.; Luo, M.; Xiong, X.; Liu, X. Drivers of Global Surface Urban Heat Islands: Surface Property, Climate Background, and 2D/3D Urban Morphologies. Build. Environ. 2023, 242, 110581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murathan, E.K.; Manioğlu, G. Impact of Urban Form on Energy Performance, Outdoor Thermal Comfort, and Urban Heat Island: A Case Study in Istanbul. Energy Build. 2025, 345, 116109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Habitat. Healthier Cities and Communities Through Public Spaces; UN Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Mahdavinejad, M.; Shaeri, J.; Nezami, A.; Goharian, A. Comparing Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI) with Selected Thermal Indices to Evaluate Outdoor Thermal Comfort in Traditional Courtyards with BWh Climate. Urban Clim. 2024, 54, 101839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matallah, M.E.; Alkama, D.; Teller, J.; Ahriz, A.; Attia, S. Quantification of the Outdoor Thermal Comfort within Different Oases Urban Fabrics. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.E.; Braithwaite, P.; Leach, J.M.; Rogers, C.D.F. A Comparison of Energy Systems in Birmingham, UK, with Masdar City, an Embryonic City in Abu Dhabi Emirate. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 65, 1299–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahzadeh, N.; Biloria, N. Urban Microclimate and Energy Consumption: A Multi-Objective Parametric Urban Design Approach for Dense Subtropical Cities. Front. Archit. Res. 2022, 11, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, C.; Lee, C.C.; Chen, X.; Li, C.Y.; Hu, P. Quantifying the Thermal and Energy Impacts of Urban Morphology Using Multi-Source Data: A Multi-Scale Study in Coastal High-Density Contexts. Buildings 2025, 15, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).