Abstract

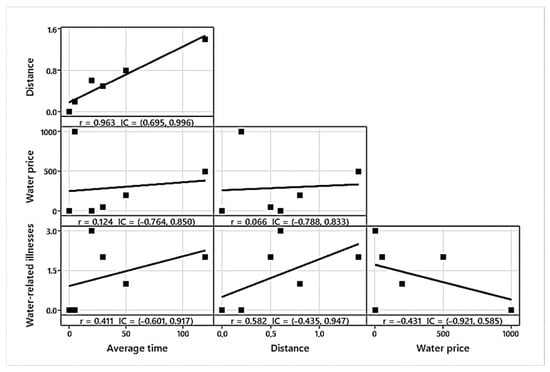

This study evaluates urban growth and access to drinking water in Bukavu from 1980 to 2024, combining diachronic Landsat image analysis, demographic and geospatial data, and household surveys. Bukavu’s population rose from 280,000 to over 2 million, with an annual growth rate of 4.57%, doubling every 16 years. The urbanized area expanded from 17 km2 in 1984 to nearly 50 km2 in 2024, with progressive densification in risk-prone zones such as steep slopes and wetlands. Theoretical access to drinking water is 61%, falling below 20% in informal neighborhoods. REGIDESO produces 25,000–30,000 m3/day, while the estimated demand is 70,000–72,000 m3/day, creating a deficit of over 30,000 m3/day. Households rely on public standpipes (45%), unimproved sources (33%), and the parallel market (44%), with average collection times of 45 min. High-density areas show elevated health risks, with 57% of water samples contaminated by Salmonella and 36% contaminated by E. coli. Land tenure insecurity affects 29.7% of households. Statistical analysis indicates strong correlations between distance and collection time (r = 0.963) and moderate correlations with disease occurrence (distance r = 0.582; time r = 0.411). These findings demonstrate that rapid urban sprawl, informal settlement, and weak institutional capacity significantly constrain water access, contributing to health risks and highlighting broader implications for African cities experiencing similar growth patterns.

1. Introduction

The world’s population, and particularly that of developing countries, has grown remarkably over the past few decades [1,2]. In 2000, there were more than 6 billion people on the planet, and the United Nations population projections for 2030 predict a global population of around 8.2 billion, with 6.9 billion living in developing countries [3]. In 2030, 3.9 billion people will live in urban areas in the Global South [4]. In less than thirty years, 1.8 billion people will migrate from rural areas to cities or be born in urban areas [5,6]. As a result, cities, as large agglomerations, the inhabitants of which have diverse professional activities, are subject to the process of urban sprawl [7,8]. Urban sprawl, which occupies an important place in the debate on territorial development, is gradually transforming the areas surrounding cities [9,10]. Urban sprawl and its impact on access to water are well-documented challenges in developing countries [11,12]. Globally, urban areas are expected to absorb all of the world’s population growth in the coming decades, with the majority of city dwellers living in overcrowded, unplanned settlements with inadequate water and sanitation services [13,14]. In sub-Saharan Africa, the situation is particularly worrying, with a growing number of people deprived of access to safe drinking water [4,15,16]. The DRC, despite having more than 50% of the African continent’s water reserves, has one of the lowest rates of access to safe drinking water and adequate sanitation, with only 52% of the population having access to an improved water source [17,18]. Urban sprawl, characterized by the uncontrolled expansion of urban areas, poses significant challenges to sustainable development, particularly in terms of access to essential services such as drinking water [13,19]. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, this problem is particularly acute in cities such as Bukavu. With a population exceeding 2 million, Bukavu is undergoing rapid urbanization, fueled by immigration, conflict, and economic opportunities [20,21,22]. Bukavu, the second largest city in Eastern DR Congo, has an average intercensal natural growth rate of 4.2% per year, meaning that the population could double every 16 years [23,24]. Its population has grown from 383,934 inhabitants in 1984 to 2,013,683 inhabitants in 2023. Characterized by recurrent water shortages due to geological and geomorphological conditions [25,26], access to drinking water has become a daily concern for the population [27,28]. According to REGIDESO [29], the access rate is around 61%, or approximately 16 L/day per person, which is well below requirements. In 2024, the average daily water production for the city was around 32,000 m3/day [29] for an estimated population of over 2,000,000 inhabitants.

In Bukavu, neighborhoods are exposed to different water supply problems depending on their geographical location, morphology, and the standard of living of their inhabitants [30]. Despite the involvement of development actors (NGOs, donors, institutional actors, private operators), the proportion of city dwellers who do not have access to water services is still significant [31,32]. This is attributable to the fact that urban water and sanitation services are still designed according to a conventional “top-down” model [33,34]. This system has not enabled universal access to water for all [19,35]. Indeed, the network model in question is unsuitable for guaranteeing access to water services for all in the current context of urban sprawl through housing developments and the establishment of informal settlements in cities in the “global South” [36,37,38]. Today, with even more widespread and rapid urban growth coupled with uncontrolled construction in Bukavu, people are developing other strategies to access water services through various means. Previous studies have addressed issues related to land rights and conflicts, land grabbing in the city of Bukavu, urban growth and environmental change, and the assessment of wastewater and excreta management in Bukavu [39,40,41,42]. These studies did not specifically address the issue of water stress as a direct consequence of uncontrolled urban growth in Bukavu. Other studies have focused on uncontrolled urbanization, wastewater and excreta management, basaltic lava flows and population growth in some neighborhoods of Bukavu [43,44,45]. None of these studies emphasized the role of state policies in urban planning in understanding the problem of access to drinking water in Bukavu. In fact, the urban sprawl of the city has consequences for the conventional provision of water services in terms of cost [46,47,48] and environmental preservation [49]. This urban sprawl means that the main actors (REGIDESO, SNEL, etc.) involved in the provision of water and electricity services are unable to meet the needs of the population, particularly those in the outlying districts of Bukavu [50]. As a result, the inhabitants of these outlying districts have to wait several years to benefit from a hypothetical extension of the water supply network. Faced with this situation, we are seeing the emergence of strategies for accessing water. This observation requires a systemic analysis that takes into account the various manifestations of urban sprawl on water services, particularly urban governance and the alternative solutions offered by institutional and non-institutional actors in Bukavu. This study, therefore, aims to analyze the impacts of urban sprawl on the water network service in terms of satisfaction, consequences, and alternatives on the one hand, and the actors involved in supply on the other. The theoretical framework, characteristics of the study area, methodology, study results, discussion, and conclusion are presented in succession. Research on this topic provides us with answers to the impacts of urban sprawl on water services in the city of Bukavu.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.1.1. Geographic Location

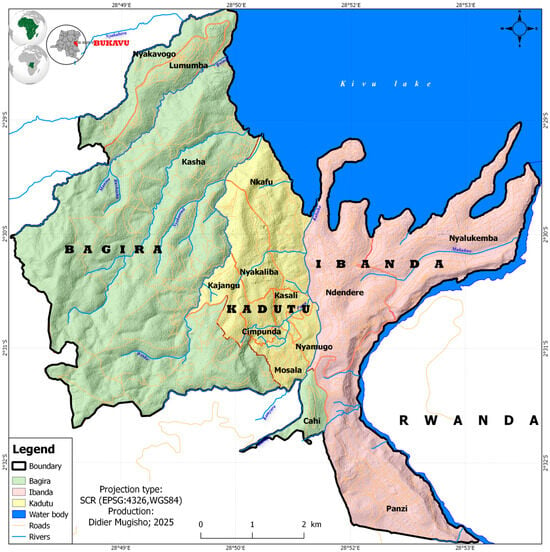

The city of Bukavu is located between 2°46′ and 2°45′ south latitude and 28°89′ and 28°79′ east longitude. Situated at an altitude of over 1600 m, it is the highest city in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Separated from Rwanda by Lake Kivu and the Ruzizi River, it is administratively subdivided into three communes: Bagira (23.3 km2), Ibanda (13.3 km2), and Kadutu (6.4 km2) (Figure 1). With more than 2 million inhabitants, it is the seventh largest city in the country in terms of population after Kinshasa, Lubumbashi, Kisangani, Mbuji-Mayi, Kananga, and Likasi [51]. The city of Bukavu covers an area of approximately 62.88 km2, of which 43.17 km2 is land and 19.71 km2 is occupied by Lake Kivu. The municipality of Bagira has four districts: Cahi (0.17 km2), Kasha (20.2 km2), Lumumba (1.5 km2), and Nyakavogo (1.6 km2). The municipality of Ibanda is subdivided into three districts: Ndendere (4.2 km2), Nyalukemba (4.7 km2) and Panzi (4.4 km2). The municipality of Kadutu is the smallest but most densely populated, accounting for about half of the city’s population. It comprises the districts of Cimpunda (0.4 km2), Kajangu (0.9 km2), Kasali (0.4 km2), Mosala (0.7 km2), Nkafu (2.2 km2), Nyakaliba (1.5 km2) and Nyamugo (0.3 km2) [24].

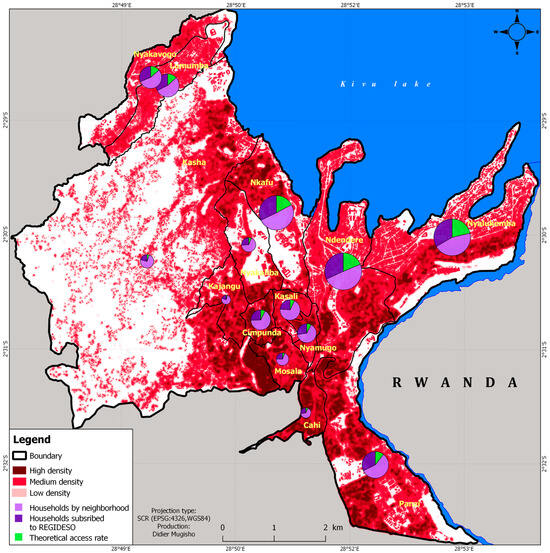

Figure 1.

The city of Bukavu and its communes and neighborhoods. The city is located in South Kivu Province, in the eastern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

2.1.2. Climate, Soil, and Vegetation

The city is located within the western branch of the East African Rift, a seismically active region crossed by numerous faults [52,53] and known to be prone to landslides [54,55,56]. With its steep slopes, mountainous terrain, deep clayey regoliths and Nitisols, alternating layers of basaltic rock that have undergone varying degrees of weathering, and a humid tropical climate, Bukavu is prone to numerous natural landslides [53,55,57].

The seasonal alternation between wet and dry seasons, combined with sometimes contrasting vegetation cover and anthropization of the territory, promotes soil erosion, which manifests itself in the form of large ravines with often unstable slopes [55,58,59]. The topography influences underground flows from the bedrock aquifers and surface water [43,59,60]. The terrain slopes from northwest to southeast. The city has high-altitude areas of over 2300 m near Comuhini and Ciriri and low-altitude areas of around 1460 m near the Mukukwe Valley and along Lake Kivu.

The climate in Bukavu is tropical and humid, with two distinct seasons: a rainy season from September to June and a dry season from July to August, characterized by temperatures not exceeding 27 °C. Rainfall varies between 1500 and 1000 mm/year. November is generally the wettest month, sometimes accounting for more than 40% of the total annual rainfall. Rainfall records taken over several decades at the Bukavu station show, in addition to significant interannual fluctuations, a general downward trend. The city of Bukavu is crossed by an extensive hydrographic network [61,62]. In addition to the rivers draining the watersheds, Lake Kivu provides the city with nearly 20 km2 of surface water.

2.1.3. Socio-Economic Situation in Bukavu

There is a diverse population in the city of Bukavu. All tribes and ethnic groups from the province of South Kivu, if not the entire country, can be found in Bukavu. However, the majority are the Bashi and the Rega [43]. In addition to the Bashi from neighboring territories (Walungu and Kabare), the Rega, the Bembe (Mwenga, Shabunda, and Fizi), the Havu from Idjwi and Kalehe, the Bavira (Uvira), the Nyindu, and the Batwa are part of the population of the city of Bukavu. Added to this population are all the other tribes from all corners of the country, foreigners, often from neighboring countries such as Rwanda and Burundi, and tourists and expatriates [63]. This often uncontrolled settlement is characterized by increasing pressure on resources (state houses, roads, bridges, green spaces, etc.) [25]. This dynamic has contributed to the emergence of informal settlements on steep, often unstable terrain, exacerbating environmental risks (landslides, flooding, erosion) [41,61,62]. Economically, Bukavu is dominated by a very active informal sector. Small businesses, urban transport (motorcycle taxis), crafts, and peri-urban agricultural activities form the basis of household income. However, the multidimensional poverty rate remains alarming: more than 70% of the population lives on less than $1.40 per day [50,64,65]. Structural unemployment, particularly among young graduates, affects nearly 45% of young people between the ages of 18 and 35. The informal employment rate exceeds 85% [66]. In terms of population, the urban part of the city has approximately 2,013,683 inhabitants [67]. It is characterized by a high proportion (60%) of young people under the age of 25. Demographically, the city has a relatively higher number of women (54%) than men (46%).

2.1.4. Water Organization and Service in the City of Bukavu

A more in-depth analysis reveals that the apparent unity of the city of Bukavu is reflected in such diversity that one might say that every city is made up of several cities. This is also the opinion of many authors. The city is a heterogeneous space, structured by different social groups, customs, and temporalities, which translates into polycentricity and urban multiplicity [68].

In Bukavu, all these elements tend to group together by affinity into individualized clusters that form strata. Thus, the city of Bukavu is characterized by central administrative subdivisions that were developed between 1928 and 1940 (1); the old planned cities or Extra-Customary Centers developed between 1947 and 1958 (2); the peripheral adobe neighborhoods that appeared between 1959 and after 1960 (3); unplanned peripheral areas of self-built housing dating from 1975 and recent spontaneous peripheral neighborhoods located in the city’s fourth ring. Although Bukavu is not a grid city based on Burgess’s theory, which distinguishes four concentric strata at the city level [69], its organic structure allows us to identify five strata based on neighborhoods. A neighborhood is defined as a clearly delineated geographical space with a main function (residential, commercial, or industrial), a social content (bourgeois, white, indigenous, mixed, etc.), an external appearance (old, modern, traditional, collective, spontaneous, etc.), a pace of life linked to its location (lively, central, peripheral, quiet), a parcel structure (formal, informal subdivision), and finally an administrative criterion (whether or not it has a neighborhood leader) [70].

With regard to the city’s water supply, the water distributed by REGIDESO comes mainly from the Murhundu plant through 10 reservoirs spread across the city’s three municipalities. This plant is the main drinking water collection and treatment station for the city of Bukavu. It dates back to the 1950s.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Sampling Campaign

Field visits consisted of observing city neighborhoods to learn about housing types and drinking water infrastructure. Next, the Murhundu facilities were visited, including storage tanks, pumping stations, springs, and standpipes. Information on the drinking water distribution network and methods, and on water supply coverage in the context of urban sprawl, was gathered from REGIDESO officials and public authorities. Subsequently, semi-structured questionnaires were administered to household heads, covering demographics, water sources, collection time and costs, and perceptions of water quality. Blocks were selected based on urbanization level, population density, and diversity of water supply sources. All interviews were carried out in French or the local language, according to respondent preference, following questionnaire translation and pre-testing. Households surveyed had an average size of 6.8 people. A total of 655 households were sampled in 67 blocks for the survey. The overall sample size was calculated to ensure an absolute error slightly above 0.05 with a 95% probability. The following formula was used to obtain the minimum sample size:

where

- n represents the total number of households to be surveyed;

- t(a) is the value of the reduced centered normal distribution with a confidence threshold of 1.96 for 95%;

- p is the proportion constituting a variable of interest in the survey, set at 0.4, with p (1 − p) = 0.24;

- d represents the sampling effect equal to 1.5;

- ma = 0.062, the margin of error of the estimate;

- k is the non-response rate set at 0.1 (10%).

Thus, the overall sample size for all neighborhoods drawn is 655 households using Formula (1). The survey was conducted in 67 blocks across the city’s 14 districts. At least four blocks with at least six households were selected in each district. The 655 households were distributed across the following districts: 17 in Cahi, 40 in Cimpunda, 39 in Kajangu, 50 in Kasali, 23 in Kasha, 40 in Lumumba, 44 in Mosala, 106 in Ndendere, 40 in Nkafu, 31 in Nyakaliba, 54 in Nyakavogo, 63 in Nyalukemba, 38 in Nyamugo, and 70 in Panzi. The sample from each neighborhood is distributed evenly according to the number of blocks in the neighborhood. All households in each block are surveyed. In each household, the head of the household is interviewed if present. If not, another member of the household over the age of 15 is interviewed. Overall, 62% of respondents are male heads of household and 38% are female.

2.2.2. Determination of Spatial Evolution and Urban Settlement Islands in the City of Bukavu

Determining the spatial evolution of Bukavu was facilitated by analyzing multi-temporal Landsat satellite images obtained from the USGS website [71] for the years 1984, 1989, 2000, 2011, and 2024. Using QGIS (v3.44.2) tools, it was possible to detect, classify, and map urbanized areas according to different periods by visualizing the extent of built-up areas. Urban settlement clusters were determined using QGIS tools, including Raster Calculator (integrated in QGIS 3.44.2), GRASS r.clump (GRASS GIS v7.9), SAGA Cluster Analysis for Grid (SAGA GIS v8.4.0), and OBIA (Object-Based Image Analysis)(integrated in QGIS 3.44.2). To define the population clusters themselves, supervised classification was used to calculate the urban density index, facilitated by QGIS extensions such as Urban Sprawl Metric and Shannon’s Entropy Index, and supported by the NDBI (Normalized Difference Built-up Index) tools used in GoogleEngine (v0.1.5) [72]. All these tools enabled us to vectorize built-up areas in order to extract population clusters and highlight them on the map.

2.2.3. Determination of the Topographical Characteristics of the City

Various GIS (Geographic Information System) tools were used to determine the characteristics of the terrain in the city of Bukavu. To determine the slopes (in %) and elevation of the terrain (in m), a 30 m spatial resolution SRTM digital elevation model downloaded from the Open Topography website [73] was used. Quantum GIS 3.6.1 software was used to extract the study area (Bukavu) from a masking layer of the city’s outline. The slopes were then calculated and classified (from ≥5% to >30%) and the different altitudes (from ≥1460 m to >2300 m). The detection of landslide scars, susceptibility assessment, and risk evaluation were made possible through QGIS extensions such as SCP, SAGA, GRASS, and InaSAFE. Roads, rivers, and the lake were extracted from existing shape files for the DRC. The locations of various reservoirs in the city and water sources were collected using an Etrex 64 GPS (Garmin Ltd., Olathe, KS, USA). The pipe routes were obtained through georeferencing and digitization of REGIDESO distribution plans.

2.2.4. Assessment of Accessibility and Costs of Access to Water in Bukavu

The assessment of household accessibility to water points was based on the use of a Pléiades image of Bukavu acquired via the National Institutional System for Shared Access to Satellite Imagery (DINAMIS) [74]. This image provided the basic data for characterizing urban morphology. First, the urban morphology was analyzed using the Urban Sprawl Metric Toolset extension of Quantum GIS, which allows urban strata to be distinguished according to build density, compactness, and spatial fragmentation. Secondly, actual accessibility to water points was modeled using cost distance, which takes into account not only physical distances but also topography, building structure, and traffic routes. Unlike a conventional Euclidean measurement, this approach is based on recursive graph optimization, defined by the following equation:

where

- d(n,x,y) is the distance between cells.

- Fric(x,y) and Fric(n) are the friction values representing movement difficulty.

- N(x,y) denotes the neighboring cells of (x,y).

- (Fric(n) + Fric(x,y))/2 corresponds to the average friction between two cells.

Equation (2) was used to convert the spatial structure and morphology of neighborhoods into values for time and cost of access to water. The results aggregated by urban stratum obtained using this method are presented in Section 3.

2.3. Tools, Data Processing, and Analysis

The survey database was analyzed using Microsoft Excel 2016, Minitab (v22.4.0), and version 3.4.3 of R. This software also enabled us to produce graphs and tables. Logistic regression was performed to assess the dependence of water stress on various spatial, demographic, and physical factors. A significant effect was assessed at a probability threshold of 0.06.

The variables studied concerned spatial change and its impacts, the role of the various actors involved in the provision of drinking water services, and households’ strategies for accessing these services. This information was supplemented by semi-structured interviews using six interview guides. Spatial analyses were performed using Quantum GIS software versions 3.6.1 and 3.26. The SCP (Semi-Automatic Classification), Cluster Analysis, Spatial Analyzer, CDU Creator, USM toolset (Urban Sprawl Metric toolset), Area Weighted Average, and other extensions facilitated image classification, centrality assessment, and stratum delimitation. In summary, the main tools and software used for spatial analysis and image processing, statistical analysis, graphing, and logistic regression are, respectively: Quantum GIS 3.6.1 and 3.26 (1), Microsoft Excel 2016 (2), Minitab (3), RStudio (v2025.09.2) and R 3.4.3 (4). All shapefile layers and Landsat datasets supporting this analysis are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

3. Results

3.1. Population Growth, Urban Sprawl, and Evolution of Planning Tools

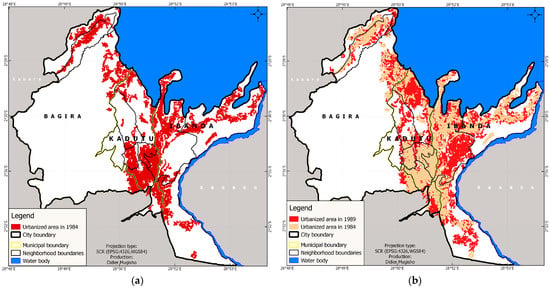

The city of Bukavu has experienced rapid population growth for several decades, leading to uncontrolled urban sprawl. Between 1980 and 2024, Bukavu’s population grew from 280,000 to over 2 million, representing an average annual growth rate of 4.57% (Table 1, Figure 2a,f). The urbanized area of Bukavu has expanded considerably, from less than 17 km2 in 1984 to nearly 50 km2 in 2024, exceeding the administrative boundaries of the city as revised in 2014 (Figure 2f). This expansion was associated with a progressive densification of the built environment throughout the different temporal intervals analyzed (Figure 2a–f).

Table 1.

Evolution of land use in the city of Bukavu (1980 to 2024).

Figure 2.

Evolution of urbanized space in the city of Bukavu: 1984 (a); 1984 to 19 (b); 1989 to 2000 (c); 2000 to 2011 (d); 2011 to 2015 (e); 2015 to 2024 (f).

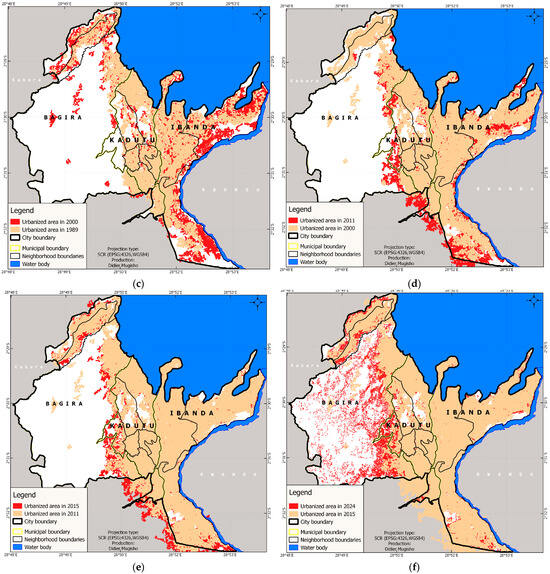

Diachronic analysis reveals that several periods of urban expansion are associated with massive population movements linked to armed conflicts since the 1990s (Figure 2c,d). Bukavu’s administrative, educational, health, and commercial functions as the provincial capital also contribute to its strong migratory appeal. The demographic data collected indicate a birth rate of 3.8% in Bukavu. Over the same period, the annual population growth rate reached 4.57%, which means that the total increase observed is greater than the natural increase alone. This indicates a significant contribution from net migration and demographic momentum. Such a growth rate represents a doubling of the population approximately every 16 years. Spatial data show an expansion of settlements towards slopes, steeply sloping areas, and certain marshy areas. The urban sprawl observed over the last three decades has led to an increase in the areas exposed to landslides, erosion, and flooding (Figure 3a,b), also affecting essential infrastructure, including water and electricity networks. The results indicate a theoretical access rate to drinking water of approximately 61%, with lower levels in peripheral areas and spontaneously urbanized neighborhoods, as shown in Figure 3d.

Figure 3.

Historical landslides: A: Landslide relative age; B: Shallow landslides; C: Reactivation; D: Landslide dynamics (a) and geomorphological constraints in the urban area of Bukavu: Altitudes (b), Slopes (c), and Land use (d).

The data collected highlights a set of urban planning documents produced at various key periods. The urban archives include an initial plan drawn up in 1927, followed by a second document in 1947, and then other versions published in 1953, 1980, 1997, 2013, and 2021, respectively. A chronological analysis of these instruments reveals a succession of regulatory frameworks aimed at spatial organization and urban development guidance. Each document has its own structure, incorporating elements such as the division of urban areas, land reserves, infrastructure proposals, land use principles, and territorial expansion forecasts. The results also show that these different tools are characterized by varying methodological approaches depending on the period. The oldest plans (1927, 1947, 1953) are based mainly on zoning principles and the functional hierarchy of neighborhoods, while the more recent versions (1980, 1997) incorporate more technical data on densification, the polar organization of the city, and population growth prospects. The 2013 document introduces new components related to structural infrastructure, natural risks, and the management of sensitive areas. The 2021 plan is the most recent tool identified in the corpus; it includes updated data on growth trends, priority development areas, technical networks, and environmental constraints. Alongside these documents, several institutional initiatives have been observed in recent years. The available data indicate the existence of an Urban Development Master Plan (SDAU) and an Urban Reference Plan (PUR) developed for the city of Bukavu. These two tools constitute operational frameworks designed to organize the spatial development of the city, particularly with regard to the location of facilities, the structuring of road networks, the management of residential areas, and the integration of water, sanitation, and electricity networks. The information collected also highlights the existence of several recent programs for the rehabilitation or improvement of urban infrastructure. These interventions include the partial modernization of the road network, the rehabilitation of drainage sections, the upgrading of certain hydraulic installations, and the restoration of priority urban areas [17,66]. The data indicate that these programs were initiated by various actors: central government, local administration, technical partners, internationally funded projects, or public–private partnerships. The sectors concerned vary according to the interventions, ranging from water and sanitation services to community facilities and mobility infrastructure. In general, there has been a continuous succession of planning tools and development initiatives over the last few decades, documenting changes in Bukavu’s urban framework and the various technical interventions expected in the city.

3.2. Physical Conditions and Spatial Distribution of Water Services in Bukavu

The distribution of drinking water services in Bukavu is highly heterogeneous in spatial terms. Municipal areas located in regions that are vulnerable due to geological and geomorphological conditions have lower levels of service (Figure 4). Observations indicate that certain parts of the urban area are exposed to phenomena such as earthquakes, landslides, erosion, or volcanic activity, consistent with the level of tectonic activity documented in the region (Figure 3). In several urban areas, buildings are located on steep slopes or in marshy areas, as indicated by elevation, slope, and land cover maps (Figure 3b–d).

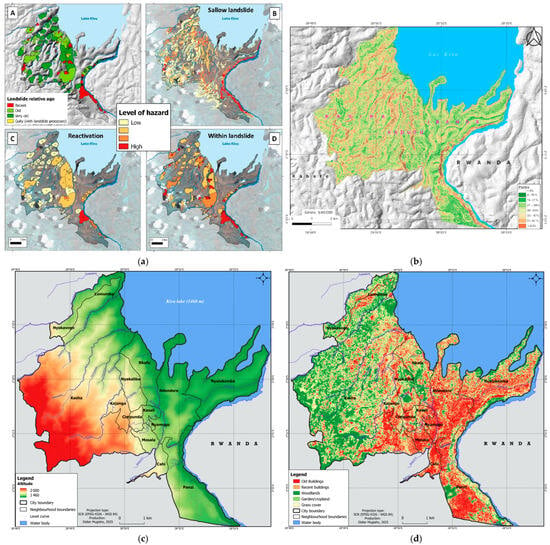

Figure 4.

Population clusters and water service by neighborhood in Bukavu.

Statistical analysis reveals a significant negative correlation between distance from the city center and drinking water service coverage (r = −0.42, p < 0.05). Central neighborhoods, notably Nyawera, Labotte, Mukukwe, and Pageco, have connection rates above 60%, while peripheral neighborhoods such as Cahi, Cimpunda, Nyakaliba, Kajangu, and Ciriri have rates below 20% in several cases (Figure 4). Field observations also reveal that the distribution of water infrastructure is denser in areas close to the city center.

In Figure 4, consolidating spatial data shows that certain population centers are characterized by high building density and unplanned urbanization, particularly in sloping areas. These areas coincide with zones where landslides have been recorded (Figure 3a,c). In several cases, the historical landslides identified show a high recurrence in steeply sloping areas (Figure 3a,b). The city is also located on the shore of Lake Kivu, whose deep waters contain significant concentrations of dissolved gases, notably carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) [75,76]. Studies conducted on water quality in Bukavu indicate that the chemical stability of Lake Kivu is a factor that may influence the groundwater in Bukavu and Goma [77]. The results of analyses suggest that, in some cases, geophysical or chemical disturbances in the lake could have a dangerous impact on groundwater resources, which is particularly relevant given that these resources account for a significant proportion of the urban water supply.

3.3. Governance Challenges, Structural Limitations of the Service, and Alternatives for Access to Water in Bukavu

The city of Bukavu faces several institutional constraints that directly affect the quality and continuity of water services. The data collected reveal a lack of operational coordination between local, provincial, and national levels of governance, which limits urban planning and the implementation of interventions related to water and basic infrastructure. The departments responsible for land registry, urban planning, and housing have limited material and financial resources. Testimonies collected report that several housing developments are created without prior study or integration into an updated master plan. This situation complicates the anticipation of water infrastructure needs. Procedures for issuing land titles and building permits appear to be unsystematic, and exchanges between technical services remain limited. The institutional officials interviewed pointed to the lack of an operational urban policy framework to implement the strategies announced at the national level. The data collected indicate that local financial allocations remain insufficient to ensure regular maintenance of water infrastructure (Figure 5c,d) and to initiate projects that keep pace with the city’s growth.

Figure 5.

Vulnerability of the REGIDESO network: DN 300 pipe damaged by construction in Nfafu (a); DN 450 pipe broken by landslide in Funu (b); butterfly valve clogged with debris in Nya-kavogo (c); and secondary pipe destabilized by erosion in Kasha (d).

Nevertheless, there are notable community initiatives active in several neighborhoods. These initiatives focus on improving access to water, installing sanitation facilities, and certain housing-related actions. These actions are present in several densely populated areas and are led by local committees, neighborhood associations, or resident groups.

In the city of Bukavu, there are recurring delays in the maintenance of existing facilities and a low capacity to meet growing needs, particularly in expanding neighborhoods (Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 2.

Access, main source, and frequency of distribution by municipality.

Data provided by REGIDESO indicates that the Murhundu plant, built in the 1950s with an initial capacity of 6000 m3/day, currently produces between 25,000 and 30,000 m3/day. This production is still below urban needs, estimated at between 70,000 and 72,000 m3/day, generating a deficit of more than 30,000 m3/day. In 2024, daily readings show a decrease in production from 32,000 m3 to 20,000 m3 [29]. Interviews confirm that various technical measures have been considered, including expanding the plant, replacing outdated pipes, and increasing supplies from secondary stations. The information gathered also mentions a project to capture water from the Mpungwe River, financed by the AFD, which is expected to provide an additional 25,000 m3/day.

Faced with the persistent shortcomings of the public water distribution network, largely inherited from colonial infrastructure, households in Bukavu are mobilizing a diverse set of alternatives to meet their daily needs. Household surveys reveal that 45% of them depend on public standpipes (Table 2), with an average collection time of 45 min (Table 3). Seasonal variations have been recorded, with the dry season marked by lower pressure and longer collection times. Thirty-two-point-eight percent of households obtain their water mainly from unimproved sources, rivers, lakes, or rainwater (Table 2). At the same time, 43.7% say they use the parallel market, which is dominated by the sale of mineral water, ice water in bags or used bottles, and distribution from cisterns or private sources. Prices vary depending on the method of supply: a 20 L canister sells for around 200 FC, while a used bottle of ice water costs between 200 and 300 FC, with prices rising during the dry season (Table 3). So-called “mineral” water is sold at around 2000 FC for a 1.5 L bottle, while a 20 L jerry can cost 45,000 FC, including the cost of the container, estimated at 40,000 FC; subsequent refills are charged at an average of 6000 FC. The results also show that most of this “mineral” water is imported from neighboring countries (67%), followed by products bottled within the city (8%), in the Kabare territory (15%), and in the city of Goma (10%). Domestic strategies also include harvesting rainwater. This practice is particularly widespread in Ndenedere (45%), Nyalukemba (23%) and Nkafu (12%), where households have tanks that provide a few days’ worth of water during periods of shortage. In other neighborhoods, such as Panzi, Bagira, Cimpunda, Kasha, and Ciriri, access to water relies largely on collective use or sharing of community water fountains.

Table 3.

Distance, time, price, and related diseases.

3.4. Organic Urban Fabric, Land Insecurity, and Spatial Constraints on Households

The city of Bukavu is undergoing urbanization marked by informal development, producing an organic urban fabric (Figure 4). Peripheral neighborhoods such as Cimpunda, Panzi, Nguba, Karhale, Binamé, Mulengeza, Chai, etc., have an irregular configuration characterized by unregistered plots, the absence of functional zoning, and a poorly structured road network. This dense and fragmented urban morphology limits vehicle and public service accessibility and complicates the extension or maintenance of water networks (Figure 5a,c). In the field, several documented cases show that unregulated construction and occupation of unstable sites have contributed to the destabilization of REGIDESO pipes (Figure 5b,d).

The data collected indicate close interactions between land tenure insecurity and conditions of access to water. Customary, administrative, and informal land tenure systems overlap, leading to situations of parallel title holdings and persistent land conflicts. These inconsistencies hinder urban planning and complicate the installation of drinking water infrastructure. Poor regular connection to the drinking water network has been recorded in areas where most households lack formal land titles. These households represent 68% of dwellings located on the urban periphery and 74% of those established in informal neighborhoods. These areas also have the highest population densities and the lowest rates of water infrastructure coverage. Surveys indicate that 29.74% of households have not established land titles for their plots. The main reasons cited are inheritance of the land, the cost of the procedures, and administrative burdens. In addition, 4.03% of the land declared has at least two parallel land titles, often associated with expropriation or multiple sales. The results relating to occupancy status show a predominance of owners (61.23%), followed by tenants (32.57%), co-owners (4.56%), and tenants living rent-free (1.64%). Among tenants, surveys report frequent disagreements over the payment of water bills, leading in some cases to the temporary disconnection of homes when bills are not paid.

Statistical analysis of the measured variables reveals several significant relationships. The correlation matrix (Figure 6, Table 3) indicates a very strong correlation between distance traveled and average time to access water (r = 0.963), reflecting a simultaneous increase in these two variables. On the other hand, the two correlations between distance and price (r = 0.066) and between access time and price (r = 0.124) are weak, suggesting a weak association between these dimensions. Health indicators show a moderate positive correlation with distance (r = 0.582) and collection time (r = 0.411), while the correlation between water price and the frequency of waterborne diseases is negative (r = −0.431) (Figure 6, Table 3).

Figure 6.

Correlation matrix—distance, time, price, and related diseases.

These results describe the statistical organization of water access conditions in different neighborhoods of the city and highlight the measured relationships between supply modalities, spatial constraints, and health indicators.

Spatial analysis also revealed a dense urban fabric (Figure 5), composed of irregular plots where the land use coefficient is often equivalent to the footprint coefficient (Figure 3). In these informally urbanized areas, water supply relies mainly on individual connections to pipes located along tertiary roads. This type of organization is one of the main supply mechanisms observed in these neighborhoods.

3.5. Health Impacts Related to the Lack of Drinking Water

In an urban context strongly marked by rapid population growth and unplanned urbanization, the city of Bukavu is facing increasingly severe water stress. This phenomenon, defined as a situation where water demand exceeds available resources in terms of quality and quantity, has worsened in this lakeside city despite its immediate proximity to Lake Kivu and numerous natural sources. The degradation of these resources, combined with inadequate water infrastructure and institutional vulnerability, has had profound health consequences, mainly affecting populations living in informal peripheral neighborhoods [78,79]. The first manifestations of this water stress in the city are reflected in a chronic shortage of drinking water. The results of this study showed that nearly 60% of households in Bukavu do not have direct access to a source of drinking water within a 500 m radius. This situation forces them to draw water from unsanitary sources, such as polluted rivers, untreated lake water, or rainwater, exposing populations to serious waterborne diseases.

Diarrheal diseases are now one of the leading reasons for visits to health centers in the city [80,81,82]. This high prevalence of waterborne diseases is due not only to the poor quality of the water consumed but also to the lack of water for hygiene purposes. Our household surveys show that hygiene practices such as hand washing, cleaning utensils, and bathing are often sacrificed in favor of vital needs such as drinking and cooking. This trade-off greatly increases the risk of transmission of microbes responsible for waterborne diseases [83]. Water stress in the city of Bukavu also has significant implications for reproductive and maternal health. Pregnant women, faced with high water loads, see their health deteriorate, and the risks of obstetric complications are increased by the consumption of contaminated water. Children, who are particularly vulnerable, suffer from chronic complications linked to repeated infections caused by unsafe water. In 2024, the city of Bukavu faced a significant resurgence of waterborne diseases, particularly cholera. According to consolidated data from provincial health facilities, the entire city was affected. In Kadutu, a total of 1096 cases of cholera were recorded, with 17 deaths, representing a fatality rate of 1.55%. The Ibanda health zone recorded 427 cases and 8 deaths (1.33% fatality rate), while the Bagira health zone recorded 209 cases and 3 deaths (1.43%). Across the city of Bakavu, this represents a total of 1732 confirmed cases and 28 deaths, for an average case fatality rate of 1.61%.

Microbiological analysis of water sources, carried out in 2025 by local environmental health teams, revealed alarming contamination in the outlying districts. Of 104 water samples analyzed, 57.1% showed traces of Salmonella enterica, while 35.7% were positive for Escherichia coli (E. coli) [83,84]. These were mainly located in unprotected natural sources commonly known as “Bisola,” especially in the Nyamugo, Cimpunda, Panzi, Cariri, and Nguba neighborhoods. These densely populated areas are characterized by the absence or weakness of REGIDESO coverage, forcing the population to obtain water under precarious conditions. The frequent proximity of latrines to sources, lakes, or rivers, sometimes less than 10 m away, is a factor that aggravates fecal contamination of water [81,84]. The local health system, already fragile, becomes overwhelmed during epidemic outbreaks. Surveys have shown that cholera often resurges during the dry season. The considerable decline in supply forces the population to resort to untreated water from lakes or springs.

4. Discussion

4.1. Uncontrolled Urbanization and Inequalities in Access to Drinking Water

The distribution of drinking water in Bukavu illustrates a deep socio-spatial divide, reflecting both the legacy of post-colonial infrastructure and the contemporary effects of informal urban sprawl [78]. Some planned central neighborhoods benefit from a relatively stable supply thanks to recently modernized infrastructure [79,85]. In contrast, peripheral and informal areas remain largely excluded from the official network, relying on natural sources, unprotected wells, or community fountains [42,86]. This inequality of access, which makes supply unpredictable and seasonal, is not specific to Bukavu. Studies conducted in Kinshasa, Nairobi, and Dar es Salaam have shown similar dynamics, where informal neighborhoods face intermittent supplies, often contaminated water sources, and high collection costs for households [17,87]. The socioeconomic implications are comparable to those observed in other African cities experiencing rapid urban growth. The time and effort spent collecting water particularly affects women and children, reducing school enrollment and household economic participation. Households on steep slopes, ravines, or swamps, and informal settlements face major logistical challenges in accessing water [78,88]. Dependence on community water points and unsafe sources leads to conflicts of use and a sense of injustice, weakening the social fabric and trust in the authorities.

Informal urban sprawl in Bukavu complicates the technical and financial viability of the REGIDESO network, a situation similar to that of water networks in the outskirts of Maputo and Abidjan [11,68]. Investments remain concentrated in central and formal areas, while expansion to peripheral neighborhoods is limited by high costs, non-payment by subscribers, and lack of maintenance [66]. The effects of water scarcity in the city of Bukavu confirm the findings of similar studies [11,12,38]. These studies state that water scarcity in all its forms has a local impact on small processing, catering, and construction businesses, which struggle to find the necessary volumes of water, thereby hindering their development. Even initiatives to modernize the network and emergency interventions, such as support from the ICRC, have a limited spatial impact, leaving peripheral populations dependent on precarious and often contaminated supplies [82,83,84]. This situation highlights the need for an integrated approach to urban water management, similar to what has been successfully attempted in Ougadougou and Lubumbashi, where Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) is used to plan distribution and protect sources [89,90]. Dependence on community water points and unsafe sources leads to conflicts of use and a sense of injustice, weakening the social fabric and trust in the authorities. However, in Bukavu, implementation is limited by institutional constraints and the difficulty of including informal areas. The use of tools such as hydraulic modeling coupled with GIS could help optimize the network and plan its expansion, but their application remains insufficient. The indirect consequences of water stress are significant and multidimensional: impacts on public health, food security, education, gender, and the local economy. These effects reinforce a vicious circle of social exclusion and compromise the city’s prospects for sustainable development.

In conclusion, the situation in Bukavu is not unique, but it illustrates the challenges common to cities in the Global South: inadequate infrastructure, informal urban expansion, institutional weakness, and socio-spatial inequalities. Sustainable solutions require targeted infrastructure investment, source protection, neighborhood inclusion, and focused collective action.

4.2. Physical Constraints and Limited Spatial Reliability of the Drinking Water Network

The inability of the drinking water network to keep pace with rapidly growing demand in Bukavu is the result of a complex combination of physical, historical, and institutional factors. The horizontal expansion of the city, characterized by unplanned informal urbanization, has gradually distanced households from the supply network. This situation is particularly pronounced in peripheral neighborhoods, where public network pipes are poorly protected and exposed to erosion risks. This phenomenon is also observed in other fast-growing African cities such as Yaoundé and Bangui, where studies have shown that informal urban sprawl complicates water distribution, increases losses, and reduces network efficiency [91,92]. The topography of the city is an aggravating factor. Peripheral neighborhoods located on unstable hillsides, wetlands, or swamps require adapted pumping and pressure systems to ensure sufficient flow. Pipes must also be secured against the risks of erosion and landslides [30,54,55]. In Bukavu, several informal areas, notably Ciriri and Panzi, illustrate these difficulties, where access to drinking water remains limited not only by distance but also by the fragility of the infrastructure. Similar situations have been observed in Addis Ababa, Bujumbura, and Zinder, where the combination of complex terrain and rapid urbanization has contributed to the deterioration of services and the contamination of water sources [93,94,95].

This structural mismatch between the existing network and the urban growth model observed in Bukavu is reinforced by historical legacy [78,96]. The infrastructure, designed during the colonial era, was sized for a population concentrated in planned central neighborhoods. Population growth and the proliferation of informal neighborhoods have therefore created a structural imbalance, with demand far exceeding distribution capacity. This situation is exacerbated by the gradual deterioration of pipes, leaks, lack of maintenance, and low subscriber solvency, limiting the resources available to maintain and expand the network. In this context, the populations of peripheral neighborhoods remain marginalized and exposed to health and environmental risks, such as landslides and flooding. These disparities create a growing territorial divide between planned areas and informal neighborhoods, with differing effects on the quality of life of residents. In well-served areas, households can devote more time to productive activities and enjoy a healthy environment. Integrated water resource management, promoted by the DRC’s Water Code, provides a relevant framework for coordinating these efforts, but its implementation remains limited by institutional constraints and the complexity of informal urbanization [22,59,87]. The active involvement of communities in local management and securing alternative water sources also appears essential to improving equity of access and strengthening urban resilience. In short, the network’s inability to absorb growing demand is the result of a combination of technical constraints, historical choices, and institutional limitations. Comparisons with other African cities confirm that these challenges are structural and require multi-scale solutions combining planning, investment, resource protection, and citizen participation. Without these measures, peripheral populations will remain vulnerable and prospects for sustainable development will continue to be compromised.

4.3. Institutional Governance, Operational Precariousness, and Low Service Resilience

Water sector governance in Bukavu appears to be one of the weakest links in the urban water system. However, in the context of the city of Bukavu, demographic pressure and unplanned urbanization would, on the contrary, require greater coordination. Institutional fragmentation is a major obstacle. Responsibilities for resource management, monitoring, planning, and protection are scattered among several structures that often operate in parallel rather than complementarily. REGIDESO, as the main service operator, operates in an environment where local authorities, provincial services, community actors, and technical partners intervene without a stable framework for consultation. This lack of coordination leads to a dispersion of efforts and, consequently, a lack of coherence in the actions undertaken. Studies conducted in cities such as Goma, Kinshasa, and Bujumbura show that this fragmentation of governance is a recurring factor in the inefficiency of urban water management, especially when cities are experiencing rapid and uncontrolled growth [17,97]. In this uncertain institutional framework, the operational precariousness of the service is an additional constraint. Financial resources remain well below what is needed, both to ensure regular maintenance of the network and to anticipate failures or improve existing equipment [66,85]. Allocated budgets are often absorbed by emergency interventions to plug leaks, repair broken pipes, or restore distribution during severe shortages. The lack of multi-year planning and sustainable financing keeps the service in a recurring cycle of short-term management, where corrective actions systematically replace preventive approaches. These findings corroborate the results of studies conducted in several other parts of the DRC, notably Lubumbashi and Kinshasa, where the structural investment deficit prevents public operators from engaging in ambitious technical and organizational reforms, widening the gap between demand growth and distribution capacity [17,90,98]. This dynamic is accentuated by the weak technical and organizational capacities of the local operator [99]. The lack of qualified personnel, the limited availability of suitable equipment, and the absence of a modernized management system slow down incident resolution and complicated network supervision [78,100]. Digital monitoring tools, which are essential in complex and extensive networks, are still underused, limiting the ability to anticipate outages and preventing the implementation of predictive management strategies. In other African cities such as Kigali and Addis Ababa, the gradual integration of smart management technologies, even on a small scale, has had a positive impact on reducing losses and improving performance [93,101,102]. Their absence in Bukavu widens the gap between the growing demand for reliable service and the actual capacity to provide it.

At the same time, land governance is a major obstacle to planning network extensions. In informal settlements, the lack of a land registry, irregular plot sizes, and complex occupancy statuses make it difficult to secure the right-of-way necessary for installing pipes. This reality exposes infrastructure to the risk of destruction, private appropriation, or illegal resale, creating an environment of great uncertainty for the operator [66,88]. Local authorities, for their part, find themselves limited in their ability to enforce urban planning standards, both because of political constraints and the influence of non-state actors present in certain neighborhoods. In many other cities, such as Ouagadougou, Niger, and Nairobi, these land tensions have been identified as one of the main obstacles to the expansion of public services in urbanized peripheries without a master plan [13,103,104]. However, weak governance is not only administrative or technical in nature; it is also part of a context of institutional vulnerability. Stable structures, continuity of public policy, clarification of responsibilities, and effective enforcement of regulations are fundamental conditions for ensuring the resilience of an urban water service [104,105]. The system’s low resilience is thus apparent in its vulnerability to environmental, political, or health crises. Episodes of drought or falling river levels, such as those documented in Bukavu in 2024, have shown that the network can quickly come under strain without emergency mechanisms in place to ensure minimal service continuity. Similarly, cholera outbreaks have highlighted the excessive dependence on ad hoc humanitarian interventions, which, although essential, cannot replace a structured public policy. In a similar context, cities such as Lusaka and Harare have demonstrated that institutional resilience depends as much on the strength of infrastructure as on coordination capacity, reliable planning, and the availability of stable financial resources [105,106].

Overall, institutional governance, operational precariousness, and low service resilience are major obstacles to sustainable improvement in access to drinking water in Bukavu. These factors, in close interaction with rapid urbanization and population growth, create a system marked by vulnerability, reactivity rather than anticipation, and fragmented decision-making that limits the capacity for long-term planning.

4.4. A Complex Relationship Between Urban Form, Land Tenure, and Health Risks

Health vulnerability in Bukavu is closely linked to the combination of urban morphology, land dynamics, and water constraints. While the built density and irregular configuration of plots have been described above, it is worth examining here how these factors modulate the health exposure of populations and the resilience of the water network.

Peripheral areas, where urban planning is virtually non-existent and plots are informally arranged, are where health risks are concentrated. Households located on steep slopes or in hydromorphic areas are not only more exposed to natural hazards (landslides, erosion) but also depend on vulnerable water sources. Frequent interruptions to the network force people to resort to water from lakes, rivers, or untreated rainwater, which increases the prevalence of diarrheal and enteric diseases. Recent health data from 2024 show that these outlying neighborhoods are particularly affected: of 1732 confirmed cases of waterborne diseases in the city, the majority are concentrated in Nyamugo, Cahi, Ciriri Mosala, Nguba, Panzi, and Lumumba, with fatality rates ranging from 1.33 to 1.55% [80,81,82]. This spatial concentration of disease reflects a cumulative phenomenon: high building density, poor infrastructure, and exposure to contaminated sources. This situation is exacerbated by the frequent proximity of latrines and the lack of treatment or protection of water sources, creating a high-risk sanitary environment. Droughts reinforce this vulnerability: the drop in the level of rivers supplying water production facilities, particularly in Murhundu, leads to prolonged periods without running water in several neighborhoods, forcing populations to resort to risky practices.

Beyond individual exposure, this situation reveals institutional and organizational shortcomings. The fragmentation of responsibilities between distribution authorities, land authorities, and health services limits the ability to anticipate risks and intervene effectively [107]. Urban planning and land management, if they do not incorporate the technical requirements of the water network, create a vicious circle in which informal urbanization exacerbates health risks and isolated technical interventions have limited and often temporary effects [108,109,110]. Thus, health inequalities are not only a function of exposure to contaminated sources but also of the institutional and organizational context, which shapes the resilience or fragility of infrastructure and populations. The most vulnerable groups—children, pregnant women, and precarious households—suffer the most severe effects [111,112]. Water stress reduces the amount of water available for domestic hygiene, leading to compromises where hand washing and washing utensils are limited in favor of direct consumption [109,113,114]. In children, this situation results in repeated infections and nutritional complications, confirming the correlations established in other African cities between urban density, diarrheal diseases, and child malnutrition [109,111]. Women, for their part, bear increased burdens for water collection, with direct consequences for their reproductive and obstetric health. This analysis also highlights the need for a multidimensional approach to strengthen health resilience. Infrastructure improvements must be accompanied by land tenure security and spatial planning, protection of water sources, and the strengthening of hygiene practices. Interventions targeting vulnerable populations, particularly children and women, are essential to reduce the impact of waterborne diseases. In addition, inter-institutional coordination, involving local authorities, distribution agencies, NGOs, and communities, is essential to create a governance system capable of responding to crises and reducing inequalities in access.

Ultimately, water stress in Bukavu cannot be understood in isolation. It is the result of a complex interplay between unplanned urbanization, land fragmentation, environmental constraints, and institutional shortcomings, which translates into health impacts concentrated in the most vulnerable areas. The adoption of integrated strategies, combining urban planning, land tenure security, resource protection, and strengthened health governance, is imperative to stabilize access to water and sustainably reduce risks to the population’s health. As the WHO, the UN [32,110], the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and other health standards [90,115,116] point out, access to safe water is not only a basic service but also an essential determinant of human health.

5. Conclusions

The objective of this study is to understand the link between urban sprawl and drinking water services in the city of Bukavu in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The methodology used is based on direct field observation and the collection of quantitative data at the household level as well as qualitative data. Statistical analyses and GIS were used to process the data. This study shows that urban sprawl has major impacts on access to drinking water in Bukavu. The population now doubles every 16 years, while the city continues to expand into high-risk areas. Marked inequalities persist between central and peripheral neighborhoods, with access rates falling below 20% in informal areas. REGIDESO’s production remains far below demand, forcing many households to use standpipes, unprotected sources, or the parallel water market. Average collection times reach 45 min. Health risks increase in densely built and informal zones, where land tenure insecurity and weak institutional capacity further aggravate vulnerability. Contamination by Salmonella and E. coli confirms the severity of these risks. Statistical analyses also reveal strong links between distance to water points, time spent fetching water, and disease occurrence, highlighting the combined effects of spatial constraints and service gaps on public health. Methodological limitations, including reliance on self-reported data, exclusion of some peripheral areas, limited geospatial resolution, and incomplete access to technical and cadastral data, constrain the generalizability of the results. Nevertheless, the findings provide valuable insights for improving knowledge and management of drinking water access in rapidly and informally urbanizing contexts. Future research should integrate field data, remote sensing, hydrological modeling, and innovative technologies, while strengthening urban planning and land management instruments. Promoting integrated, multisectoral, and participatory strategies is essential to ensure equitable and sustainable access to drinking water and reduce health vulnerabilities in the city.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/urbansci9120525/s1. Figure S1: Children_fetching_water in _Bukavu City; Figure S2: Damaged_water_pipes_1_Bukavu; Figure S3: damaged_water_pipes_2_Bukavu; Figure S4: damaged_water_pipes_3_bukavu; Figure S5: Damaged_water_pipes_4_bukavu; Figure S6: Water_reservoir_exterior_Bukavu; Figure S7: Water_reservoir_interior_Bukavu; Figure S8: Sentinel2_Bukavu_l2a_b12.tif; Figure S9: Sentinel2_Bukavu_l2b_b12.tif; Table S1: Methodology_flowchart_Bukavu.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M.N. and J.B.N.M.; Methodology, S.K.M.; Software, D.M.N., P.B. and S.K.M.; Validation, D.M.N., P.B. and J.B.N.M.; Formal analysis, J.B.M.M., P.B. and J.K.K.; Resources, J.B.M.M. and J.K.K.; Data curation, D.M.N., P.B. and S.K.M.; Writing—original draft preparation, D.M.N. and J.B.N.M. and; writing—review and editing, J.B.N.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors are grateful to the Cape Peninsula University of Technology (Cost Code: Y251), in Cape Town, South Africa, for its financial support.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study by the Institution Committee due to Law no. 18/035 of 13 December 2018 in the Democratic Republic of Congo (Articles 70–75) (establishing the fundamental principles relating to the organization of public health) and Guidelines for the Ethical Evaluation of Research Involving Human Subjects in the Democratic Republic of Congo (Directives 1 and 24). (This study did not involve any experimentation on humans tissues and/or animals, nor did it include the collection of sensitive or personally identifiable data. The research relied primarily on spatial datasets, satellite imagery, archival materials, and urban field observations. Anonymous interviews addressed only non-sensitive topics related to water access and urban dynamics.).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this study, the authors used ChatGPT 5.1 for the purposes of grammar corrections, spelling, and style refinement. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. In addition, we are delighted to express our gratitude to the Department of Geography and Environmental Management at ISP-Bukavu and the Science and Technology Section for their invaluable administrative assistance in data collection. We are also extremely grateful to the municipal authorities and the heads of state technical services who kindly agreed to take part in our interviews for data collection. The authors are extremely grateful to the reviewers who provided invaluable feedback, helping to enhance the clarity and quality of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dramani, L. Impact of the Demographic Dividend on Economic Growth in Senegal. Afr. Pop. Stud. 2016, 30, 2832–2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mberu, B.; Béguy, D.; Ezeh, A.C. Internal migration, urbanization, and slums in Sub-Saharan Africa. In Africa’s Population: In Search of a Demographic Dividend; Groth, H., May, J.F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 315–332. ISBN 978-3-319-46889-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP. Human Development Report. In Sustainability and Equity: A Better Future for All; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Debela, B.K.; Bouckaert, G.; Troupin, S. Access to drinking water in sub-Saharan Africa: Is the doctrine of the promoter state relevant? Rev. Int. Des. Sci. Adm. 2022, 88, 411–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morange, M.; Spire, A. Report on the Round Table Discussion “Spatial Justice in Cities of the South”: CNFG Symposium “The Competitive City, at What Price?”; University of Paris-Ouest Nanterre: Nanterre, France, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochot, A. Rurality, nature, and the environment. In Rurality, Nature, and The Environment; Érès: Toulouse, France, 2017; pp. 133–148. ISBN 978-2-7492-5392-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Cunha, A. Metropolization, international migration, and the plurality of social spaces: Swiss agglomerations facing the challenge of integration. Geogr. Helv. 2005, 60, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rufin, C. Governance Innovations for Access to Basic Services in Urban Slums. SSRN J. 2016, SSRN 2742424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Méo, G. Peripheral Growth of Urban Areas: Small and Medium-Sized Towns in Southern Aquitaine; Maison des Sciences de l’Homme d’Aquitaine: Pessac, France, 1986; ISBN 978-2-85892-098-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, I.A.; Adam, E. Urbanization in Sub-Saharan Cities and the Implications for Urban Agriculture: Evidence-Based Remote Sensing from Niamey, Niger. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyika, J.; Dinka, M.O. Water Challenges in Rural and Urban Sub-Saharan Africa and Their Management; SpringerBriefs in Water Science and Technology; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; ISBN 978-3-031-26270-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Curiel, R.; Luengas-Sierra, P.; Borja-Vega, C. Urban Sprawl Is Associated with Reduced Access and Increased Costs of Water and Sanitation. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaldo, A.G.; Nocentini, M.G.; Lemes De Oliveira, F.; Mahmoud, I.H. Nature-based solutions and urban planning in the Global South: Challenge orientations, typologies, and viability for cities. Land Use Policy 2025, 150, 107439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Democratic Republic of Congo Urbanization Review: Productive and Inclusive Cities for an Emerging Democratic Republic of Congo; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-4648-1203-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terefe, B.; Jembere, M.M.; Assimamaw, N.T. Access to drinking safe water and its associated factors among households in East Africa: A mixed effect analysis using 12 East African countries recent national health survey. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2024, 43, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaglin, S. Urban governance and access to drinking water in Morocco: Public-private partnerships in Casablanca and Tangier-Tetouan, Claude de Miras and Julien Le Tellier, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2005, 275 p. Flux 2008, 70, III. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbongo Mbuli, E. Political mentality and good governance in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Survey conducted in the city of Kinshasa. Cridupn 2024, 100, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibbrandt, M.; Finn, A.; Oosthuizen, M. Poverty, Inequality, and Prices in Post-Apartheid South Africa. In Growth and Poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa; Arndt, C., McKay, A., Tarp, F., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 393–418. ISBN 978-0-19-874479-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decoupigny, F. Spatial occupation, densification, and urban sprawl. L’Espace Géographique 2023, 51, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmé, M.; Walsh, A. Corruption Challenges and Responses in the Democratic Republic of Congo; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büscher, K. Violent Conflict and Urbanization in Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo: The City as a Safe Haven. In Cities at War; Kaldor, M., Sassen, S., Eds.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 160–183. ISBN 978-0-231-54613-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büscher, K. Urbanization and the Political Geographies of Violent Struggles for Power and Control: Boomtowns in Eastern Congo. Int. Dev. Policy 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masumbuko, D.R.; Kakira, M.L.; Kalungwe, B.S.; Mweze, R.D.; Zamukulu, P.M.; Mushagalusa, G.N. Uncontrolled construction and environment management issues of the septic tanks in Bukavu city, eastern D.R. Congo. Discov. Environ. 2025, 3, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michellier, C. Contributing to the Prevention of Geological Risks: Context of Data Scarcity: The Cases of Goma and Bukavu (DR Congo); Université Libre de Bruxelles: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ndyanabo, S.; Vandecasteele, I.; Moeyersons, J.; Ozer, A.; Ozer, P.; Dunia, K.; Cishugi, B. Development of the city of Bukavu and mapping of vulnerabilities. Ann. Sci. Sci. Appliquées L’université Off. Bukavu 2010, 2, 120–127. Available online: https://orbi.uliege.be/handle/2268/82774 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Sandao, I.; Babaye, M.S.A.; Ousmane, B.; Michelot, J.L. Contributions of natural water isotopes to the characterization of aquifer recharge mechanisms in the Korama basin, Zinder region, Niger. Int. J. Bio. Chem. Sci. 2018, 12, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenmark, M. Rapid Population Growth and Water Scarcity: The Predicament of Tomorrow’s Africa. Popul. Dev. Rev. 1990, 16, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenmark, M. Water Scarcity and Food Production in Africa. In Food and Natural Resources; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1989; pp. 163–190. ISBN 978-0-12-556555-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- REGIDESO. Urban Drinking Water Supply Project. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/776981435/Rapport-de-la-REGIDESO-pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Nshokano Mweze, J.-R.; Muhigwa, M. Intensification of the Built-Up Zone in the Riparian Area of Bukavu City: Impact on Population Vulnerability in the Context of Urban Natural Hazards. In Proceedings of the 5th International Young Earth Scientists (YES) Congress “Rocking Earth’s Future”, Berlin, Germany, 9–13 September 2019; pp. 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouaceur, Z. The resilience of Sahelian cities to climate change: A case study of the city of Nouakchott (Mauritania). In Multidimensão e Territórios de Risco; Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 2014; pp. 371–375. ISBN 978-989-96253-3-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Planning and implementing actions to ensure equitable access to water and sanitation. In Human Rights to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation in Practice; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 26–32. ISBN 978-92-1-004638-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutard, O.; Rutherford, J. Networks transformed by their margins: Development and ambivalence of “decentralized” techniques. Flux 2009, 76–77, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monstadt, J.; Schramm, S. Toward The Networked City? Translating Technological Ideals and Planning Models in Water and Sanitation Systems in Dar es Salaam. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2017, 41, 104–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamé, E. Intercultural Sustainable Urbanism for the African City of Tomorrow; ISTE Group: London, UK, 2022; ISBN 978-1-78405-862-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisse, M.; Dagno, B.; Togo, A. Urban management and planning in Mali: The challenges of controlled urban space management in Bamako. RKF 2024, 3, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hounmenou, B.G. Drinking water governance and local dynamics in rural areas in Benin. Développement Durable 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grelle, M.H.; Kabeyne, K.; B.V.; Kenmogne, K.; G.-R.; Tatietse, T.; Ekodeck, G.E. Access to drinking water and sanitation in cities in developing countries: The case of Basoussam (Cameroon). Vertigo 2006, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Saint Moulin, L. Conjunctures of Central Africa 2018, Cahiers africains n° 92, Tervuren/Paris, Royal Museum for Central Africa. Congo-Afrique 2025, 58, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisoka, A.N.; Ansoms, A.; Thomson, S. (Eds.) Field Research in Africa: The Ethics of Researcher Vulnerabilities; Boydell: Suffolk, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-1-80010-156-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cléophace, B.; Jean-Paul, B.; André, N.; Léonard, M.; Lucien, W.; Léon, B. Contribution to the Study of Urban Growth and the Evolution of the Environmental Situation. Case of the City of Bukavu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo. Int. J. Progress. Sci. Technol. 2021, 27, 190–202. Available online: https://ijpsat.org/index.php/ijpsat/article/view/3297 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Kishota, P.M.; Bigumandondera, P.; Manirakiza, N.; Faby, J.A.; Tabou, T.; Aleke, A. Assessment of Wastewater and Excreta Management in the City of Bukavu, Democratic Republic of Congo. Available online: https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation?paperid=141836 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Birhenjira, M.E. New contraints on the eruption of cenozoic basaltic flows in N-W Bukavu city. Geol. Soc. Am. 2017, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trefois, P.; Moeyersons, J.; Lavreau, J.; Alimasi, D.; Badryio, I.; Mitima, B.; Mundala, M.; Munganga, D.O.; Nahimana, L. Geomorphology and urban geology of Bukavu (D.R. Congo): Interaction between slope instability and human settlement. SP 2007, 283, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshimbalanga, A.; Zamukulu, P.M.; Chirhalwirwa, L.; Karume, K. Rapid Urbanization and Environment Management in Nkafu Municipality, Eastern DR Congo. GEP 2023, 11, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diabagaté, A.; Konan, G.H.; Koffi, A. Stratégies d’approvisionnement en eau potable dans l’agglomération d’Abidjan (Côte d’Ivoire). GEO-ECO-TROP 2016, 4, 345–360. Available online: http://geoecotrop.be/uploads/publications/pub_404_08.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Jaglin, S. Participation in the service of neoliberalism? Users in water services in sub-Saharan Africa. In Local Management and Participatory Democracy; La Découverte: Paris, France, 2005; pp. 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, R.R. Urbanization as a Determinant of Health: A Socioepidemiological Perspective. Soc. Work Public Health 2014, 29, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretagnolle, V. Conflicts over natural resources in rural areas. In Sustainable Development Uncovered; Euzen, A., Eymard, L., Gaill, F., Eds.; CNRS Éditions: Paris, France, 2013; pp. 130–131. ISBN 978-2-271-07896-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wa Rusaati, N.T.; Espoir, L.K. Electricity Access in Goma and Bukavu City, Democratic Republic of Congo. IJPSAT 2023, 39, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Saint Moulin, L. Cities and Spatial Organization in the Democratic Republic of Congo-L’Harmattan-Torrossa. Available online: https://www.torrossa.com/en/resources/an/5114965 (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Higgins, M.; Wdowinski, S. InSAR Detection of Slow Ground Deformation: Taking Advantage of Sentinel-1 Time Series Length in Reducing Error Sources. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delvaux, D.; Mulumba, J.-L.; Sebagenzi, M.N.S.; Bondo, S.F.; Kervyn, F.; Havenith, H.-B. Seismic hazard assessment of the Kivu rift segment based on a new seismotectonic zonation model (western branch, East African Rift system). J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2017, 134, 831–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewitte, O.; Michellier, C.; Mugaruka Bibentyo, T.; Kulimushi Matabaro, S.; Kadekere, I.; Nzolang, C.; Kervyn, F. Operational assessment of landslide risks in the sprawling city of Bukavu (DR Congo). In Proceedings of the EGU General Assembly 2023, Vienna, Austria, 24–28 April 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki Mateso, J.-C.; Bielders, C.L.; Monsieurs, E.; Depicker, A.; Smets, B.; Tambala, T.; Bagalwa Mateso, L.; Dewitte, O. Characteristics and causes of natural and human-induced landslides in a tropical mountainous region in the eastern part of the African Rift Valley: The rift flank west of Lake Kivu (Democratic Republic of the Congo). Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 23, 643–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobile, A.; Dille, A.; Monsieurs, E.; Basimike, J.; Bibentyo, T.M.; D’Oreye, N.; Kervyn, F.; Dewitte, O. Multi-Temporal DInSAR to Characterize Landslide Ground Deformations in a Tropical Urban Environment: Focus on Bukavu (DR Congo). Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilunga, L. Some Physical and Human Aspects of the Development of the Kadutu Area (Bukavu). 1990. Available online: https://www.persee.fr/doc/payen_0989-6007_1990_act_3_1_865 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Moeyersons, J.; Tréfois, P.; Lavreau, J.; Alimasi, D.; Badriyo, I.; Mitima, B.; Mundala, M.; Munganga, D.O.; Nahimana, L. A geomorphological assessment of landslide origin at Bukavu, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Eng. Geol. 2004, 72, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakweya, G. How urbanization accelerates landslides in the DRC. Nat. Afr. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butara, S.; Fiama, S.; Mugisho, B.E.; Mongane, A. Susceptibility to landslides: The case of the Ibanda/Bukavu/Democratic Republic of Congo municipality. Int. J. Innov. Appl. Stud. 2015. Available online: https://search.proquest.com/openview/5a5c017f8e44089f6b4353b1ea5cffa1/1?pqorigsite=gscholar&cbl=2031961 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Kulimushi, M.S.; Mugaruka, B.T.; Muhindo, S.W.; Michellier, C.; Dwitte, O. Landslides and Elements at Risk in the Wesha Watershed (Bukavu, DR Congo). Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321889250 (accessed on 29 August 2025).