Abstract

Highway under-bridge areas represent a valuable land resource while simultaneously constituting a sensitive ecological zone. Achieving a balance between its redevelopment and ecological preservation constitutes a critical challenge within the field of ecological engineering. Although prior research has addressed urban elevated underbridge space, investigations specifically focusing on highway underpasses remain limited. The absence of standardized criteria for assessing the suitability of these spaces has resulted in uncoordinated and fragmented utilization. In response, this study proposes a comprehensive evaluation framework that integrates multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) methodologies with optimized backpropagation neural networks, specifically genetic-algorithm-optimized BP (GA-BP) and particle-swarm-optimization-optimized BP (PSO-BP). The model incorporates indicators spanning physical characteristics, environmental factors, safety considerations, and accessibility metrics, and is applied to an empirical dataset comprising 134 highway bridge underpasses in Fuzhou City. The results indicate that (1) both the GA-BP and PSO-BP models enhance convergence speed and classification accuracy, with the GA-BP model demonstrating superior stability and suitability for classifying underpass suitability; (2) the principal determinants of suitability include traffic accessibility, safety parameters, and spatial relationships with adjacent water bodies and agricultural lands; and (3) underpasses characterized as hub-type, single-sided road-adjacent, and cross-connection configurations exhibit greater potential for redevelopment. This investigation represents the first integration of MCDM and optimized neural network techniques in this context, offering a robust tool to support the scientific planning and ecological conservation of underbridge space environments.

1. Introduction

In 1986, Trancik proposed the concept of “Lost Space”, pointing out that infrastructure like highways disrupts the urban–rural fabric, negatively affecting both the quality of life and the environment [1,2]. As a result, improving the ecological function and functional reuse of spaces beneath bridges and integrating them into the broader ecological and urban landscape have become key issues in space management.

In recent years, research on the underbridge space has expanded from focusing on structural safety and space utilization to include aspects like ecological improvements, microclimate regulation, and remote sensing applications. In terms of the ecological environment, the area under elevated bridges acts as a unique “sub-microclimate unit,” with a shading effect that reduces surface radiation flux [3,4,5]. However, the reduction in turbulence intensity by around 60% may increase pollutant retention time [6]. Sobrino JA et al. utilized remote sensing technology to reveal the impact of elevated bridges on the urban surface temperature and explored their potential role in regulating the thermal environment [7]. Since 2023, with the advent of new technologies such as satellite remote sensing and digital twins, researchers have started combining remote sensing images, GIS, and landscape indices to explore the interaction between highway networks and regional ecological environments. This approach provides valuable insights for building green infrastructure and promoting sustainable urban development [8,9,10].

International practices further demonstrate diversified development paths for under-bridge renovation. In Europe and North America, ecological suitability assessment systems have matured. For example, Norway’s Opps Tadåa highway bridge incorporated life-cycle assessment (LCA) into its renovation, forming a “material selection–ecological benefits–functional requirements” framework that reduces carbon emissions while ensuring structural safety [11]. North American cities emphasize ecological connectivity and habitat restoration under the principle of “ecological function first,” supported by refined evaluation indicators and targeted ecological measures [11]. New York City, managing 700 miles of elevated structures, has advanced a replicable model through phased steps, including research, pilot projects, and design toolkits [12]. In Toronto, the Gardiner Expressway renovation transformed fragmented and isolated parcels into an “ecology–living” composite corridor that reconnects divided communities and converts former grey spaces into active public realms [13].

In practice, the renovation of underbridge space has two main directions: One is to transform gray areas into multifunctional public spaces that integrate transportation, recreation, and commercial uses [14,15,16]. For instance, in cities like Hangzhou, Chongqing, Shenyang, and Xi’an, some underpass spaces have been utilized as parking lots; in the Taiwan Province of China and Germany, bicycle greenways that combine commuting and fitness functions have been constructed. In terms of leisure and recreation, the underpass park in Toronto, Canada, is a highly praised success story; commercial development is exemplified by the spaces under elevated structures in Nakameguro, Japan, as well as practices in Brazil and France, among others. The second aspect involves constructing ecological corridors to connect fragmented habitats, thereby promoting the restoration of urban biodiversity and enhancing ecosystem services [17,18,19,20]. As a “garden city”, Singapore has implemented vertical greening on the facades of elevated bridges, as well as in the areas beneath and at the base of the bridges. However, many bridge renovations still face challenges, such as low pedestrian traffic, limited commercial potential, difficulties in implementing green spaces, and interference with traffic flow [21].

Existing research has focused mainly on urban elevated bridges, with little attention given to highway underpasses. At the same time, an appropriate renovation method is one of the key factors for the success of the renovation of the bridge under space. Furthermore, a lack of unified, scientific criteria for evaluating the suitability of renovations complicates the decision-making process.

This study proposes a new framework for evaluating the suitability of underpass space renovations by combining MCDM and optimized BP neural networks (including GA-BP and PSO-BP). MCDM helps integrate various data sources and balance trade-offs between multiple evaluation criteria. While MCDM has been widely used in land use and ecotourism evaluations [22,23,24,25], it relies heavily on expert judgment to assign weights, which may fail to capture complex nonlinear relationships. To address these limitations, this study incorporates BP neural networks, which are well-known for their ability to learn and perform well in tasks like land suitability assessments, ecological evaluations, and traffic predictions [26,27,28,29]. However, their initial weights and thresholds are usually randomly generated, which can easily lead to slow convergence speed and getting trapped in local optima. The research further enhances the BP network with genetic (GA) and particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithms to improve prediction accuracy and efficiency. The genetic algorithm (GA) optimizes the network parameters through selection, crossover, and mutation operations, enhancing the global search ability; the particle swarm algorithm (PSO) accelerates convergence by relying on the group intelligence mechanism and performs well in continuous optimization problems. The BP neural network integrated with optimization algorithms has achieved good results in ecological monitoring, resource assessment, and spatial planning. To ensure the reliability of the optimization process, the key parameters of the GA and PSO algorithms—such as population size, crossover settings, and inertia weight—were selected following a systematic tuning procedure. Initial values were assigned based on commonly recommended ranges in the literature, after which multiple trial runs were conducted to compare model convergence speed, stability, and prediction accuracy under different parameter configurations. In addition, a structural sensitivity analysis was performed by perturbing these core parameters to assess their impact on model performance. The results confirm that the final GA/PSO parameter settings are robust and produce consistent optimization outcomes, demonstrating that the parameter selection is both justified and reliable.

The method is tested using 134 highway underpasses in Fuzhou City to evaluate their suitability for renovation. The findings aim to provide a practical basis for the ecological restoration and functional development of underpass spaces and offer guidance for the sustainable use of highway underpasses across China.

2. Method

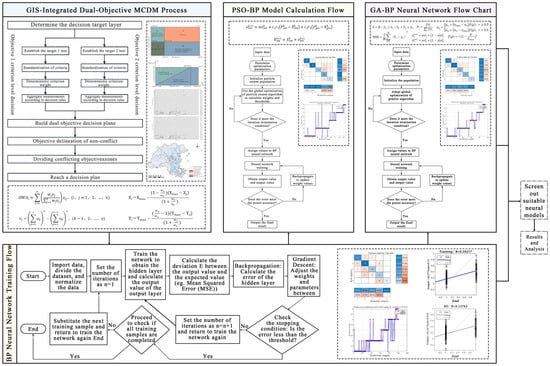

To scientifically assess the functional development potential and ecological protection value of the space beneath highway bridges, this study has established a technical route of “multi-criteria decision analysis—intelligent optimization model—GIS spatial expression” (Figure 1). The process involves three main stages: multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDM), classification using an intelligent optimization model, and model selection and result analysis. The analysis utilizes ArcGIS10.7 and TerrSet2020 software for spatial data standardization, visualization, and mapping.

Figure 1.

Research Flowchart.

2.1. Construction of Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Model

The multi-criteria decision-making model involves selecting relevant indicators and calculating their weights. The Ordered Weighted Averaging (OWA) method is used to normalize and combine the indicators, resulting in a suitability score for each underpass based on two objectives: functional development and ecological protection. This approach identifies areas of conflict by constructing a dual-objective decision plane and determines the preliminary suitability of each underpass space.

2.1.1. Establishment of the Indicator System and Determination of Weights

Through literature research, expert consultation, and field investigation, an evaluation index system covering both functional development and ecological protection was established, and the weights were obtained using the AHP method. The data sources included statistical data, remote sensing images, on-site measurements, and questionnaire surveys.

2.1.2. Data Standardization

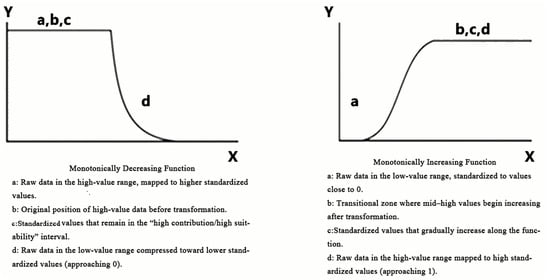

To account for varying units of measurement, the linear normalization method was applied to standardize each indicator within the range of [0, 1]. Positive correlation indicators were assigned increasing functions, while negative correlation indicators, such as noise, distance to water systems, and basic farmland, were assigned decreasing functions. These standardized values served as inputs for subsequent aggregation and modeling (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Monotonically decreasing and monotonically increasing functions of data standardization (Image source: Self-drawn by the author).

2.1.3. OWA Aggregation Criterion Layer

The ordered weighted averaging (OWA) method was used to aggregate the indicators and calculate the suitability scores for the functional development and ecological protection goals. The formula for aggregation is as follows:

In the formula, wj represents the weight of each criterion; vj is the ordinal weight; zij is the attribute value of the criterion.

The calculation formula for the ordinal weight vj is as follows:

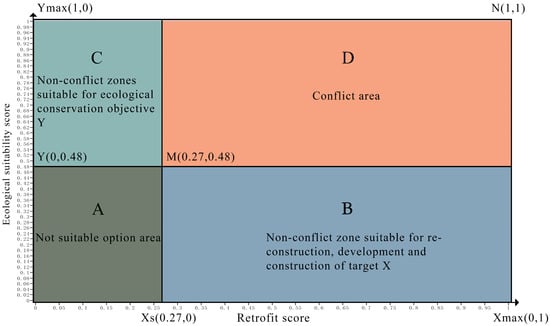

2.1.4. Dual-Objective Decision Plane

A dual-objective decision plane was constructed using the suitability scores for both functional development and ecological protection. The X-coordinate corresponds to the development goal, and the Y-coordinate corresponds to the ecological protection goal. The range for both scores is [0, 1], meaning the values of and are 1. The equilibrium point of the system was identified as the point M(), which serves as the reference point for identifying conflict areas. The target conflict area D is divided accordingly. Currently, for the division of the D area, it is mainly based on the determination of the conflict area D area by the line passing through the conflict area origin (point M) and the angle of the tangent value with the horizontal coordinate, as proposed by Eastman.

Step 1, Initial Division of Decision Plane: The minimum total score required for each indicator was calculated for both functional development and ecological protection goals, which will be the M() of the appropriate scoring interval.

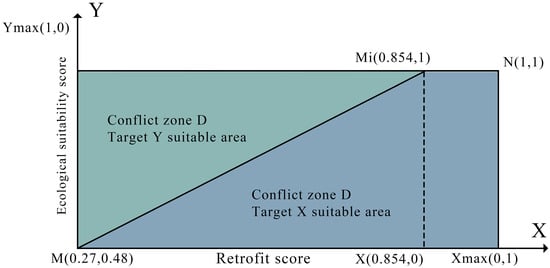

Step 2: Based on the target, determine the positions of the lines and the conflict zones, and calculate the coordinates of the point . Also, define the positions of the conflict zone dividing lines [30].

In the first case, the weight of target X is greater than that of target Y. The calculation formula is as follows:

In the formula: and correspond to the maximum and minimum values of the X coordinate of the conflict area; and are the target weights for X and Y, respectively.

In the second case, if the weights of target Y and target X are equal, then Mi = (1,1).

In the third case, the weight of target Y is greater than that of target X. The calculation formula is as follows:

In the formula: Ymax and correspond to the maximum and minimum values of the X coordinate in the conflict area; and are the target weights for X and Y, respectively.

2.2. Neural Network Optimization Model

Based on the MCDM results, the BP neural network was used to classify and predict the suitability of highway bridge underpass spaces based on the results from the MCDM analysis. The network was optimized using genetic algorithms (GA) and particle swarm optimization (PSO) to improve convergence speed and prediction accuracy. By comparing the initial classification results, the model that is most suitable for the classification of the suitability for the renovation of the space under the highway bridge is selected.

2.2.1. BP Neural Network

The Backpropagation Neural Network (BP) consists of an input layer, a hidden layer, and an output layer. The normalized data was input into the network, where the hidden layer performed nonlinear mapping based on weights, thresholds, and activation functions. The output layer compared predicted results with actual values and adjusted weights through backpropagation until the network achieved the desired accuracy, thereby achieving the prediction and classification of the suitability of the under-bridge space.

2.2.2. GA-BP Neural Network

To address the slow convergence and local optima issues of the BP network, the genetic algorithm (GA) was incorporated to optimize the network’s initial weights and thresholds. GA enhances the global search ability through selection, crossover, and mutation operations, and significantly improves the prediction accuracy and stability. The optimization process includes initializing the population, selecting the best individuals, and performing crossover and mutation. The formulas are as follows:

R, and represent the number of neurons in the input layer, hidden layer, and output layer, respectively.

In the formula, n represents the number of training samples; is the predicted value on the test set; is the corresponding true value.

where represents the fitness value of the i-th individual.

α is a random number within the range of [0, 1].

represents the upper bound of the gene; represents the lower bound of the gene; represents the current iteration number; represents the maximum number of evolutionary iterations; and are both random numbers within the range of [0, 1].

2.2.3. PSO-BP Neural Network

The particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm was used to optimize the BP neural network by iteratively adjusting velocity and position. PSO enhances convergence efficiency and computational accuracy. Compared to GA, PSO performs better in terms of global search speed and is ideal for large datasets. The specific update formulas for the PSO algorithm are as follows:

In the formula: n = 1, 2, 3, …, N; m = 1, 2, 3, …, M; k represents the number of iterations, w is the inertia weight; and are acceleration coefficients; and are random values between 0 and 1.

2.3. GIS Spatial Analysis and Visualization

Firstly, after Xi or Yi is determined, the position of the conflict zone demarcation line is determined to achieve the complete allocation of the conflict targets through the decision-making plane. Once the demarcation line is located, the visual allocation of the dual-target spatial resources can be realized through the ArcGIS scatter plot tool.

2.4. Empirical Region Selection

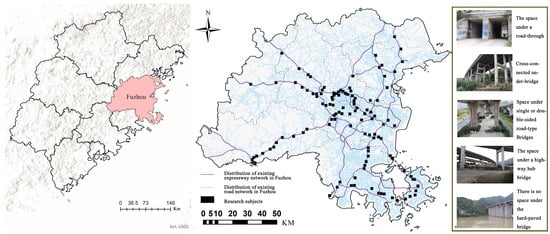

Fuzhou City, Fujian Province (25°15′–26°39′ N, 118°08′–120°31′ E), has a subtropical monsoon climate. Prior research shows that shading and impeded ventilation under elevated structures generate distinct “sub-microclimate units,” featuring reduced radiation and localized cooling but increased humidity and pollutant retention, which affect thermal comfort and ecological stability [31]. These climatic influences make regional environmental conditions a key determinant of under-bridge suitability.

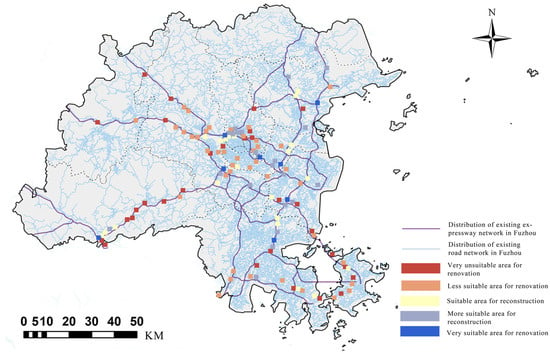

As a rapidly developing provincial capital, Fuzhou has formed a “ring + radial” highway network that produces a large number of under-bridge spaces. Recent policies—such as the Fuzhou Urban Renewal Plan (2021–2025) and the Ecological Fuzhou Construction Outline (2023–2035)—explicitly identify these spaces as important stock resources, encouraging their reuse as green infrastructure, ecological corridors, or multifunctional public spaces.

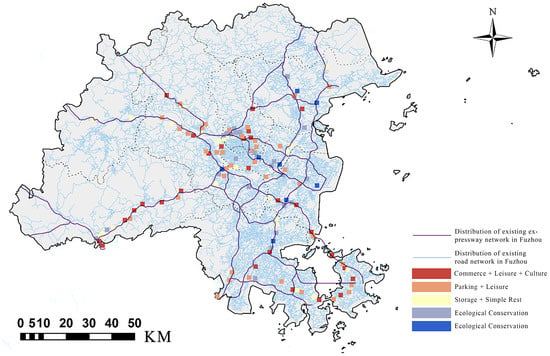

Based on prior field investigations, this study identified 134 highway underpass spaces across urban, suburban, and peri-urban areas in Fuzhou (Figure 3). These samples include five types. Highway hub underpasses are located at major interchange nodes, characterized by elevated structures, sufficient natural light, and low traffic beneath, making them well-suited for multifunctional redevelopment. Cross-connected underpasses, situated at intersections with urban roads or ecological corridors, offer moderate lighting and multidirectional accessibility, with suitability largely shaped by adjacent land use. Single- and double-sided road-facing spaces run parallel to urban roads and form linear, visible, and relatively safe environments, enabling a wide range of potential public uses. Road-penetration spaces feature continuous vehicular flows and poor lighting, constraining their potential for human-oriented activities. Poor-accessibility ecological spaces are typically adjacent to natural landscapes and experience minimal disturbance, thus holding greater ecological value than development potential.

Figure 3.

Comprehensive Urban Transportation Plan of Fuzhou City.

3. Research Results

3.1. Preliminary Evaluation Results of Dual-Objective MCDM

3.1.1. Calculation of Indicators and Weights

Based on the AHP method, an evaluation index system for the suitability of the space under highway bridges was constructed. This system includes functional development goals (such as suitability for redevelopment, environmental quality, and safety) and ecological protection goals (such as water system distribution and vegetation coverage). After conducting two rounds of expert questionnaires and consistency checks, 52 valid responses were obtained, and the weights of each index were calculated (Table 1). Some qualitative indicators were converted into quantitative measures through scoring, and others, such as traffic accessibility and safety, were standardized using the maximum-minimum method.

Table 1.

Valuation index of space suitability under urban highway bridge.

3.1.2. Aggregated Results of the Criterion Layer

In the evaluation of functional development suitability, this study considered ecological factors like the distribution of water systems, basic farmland, and vegetation coverage. Additionally, 11 indicators, including suitability for transformation, environmental aesthetics, and convenience and safety, were used as constraints to ensure that the development process incorporates ecological protection (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Modify the OWA collection result of the development target (Image source: Self-drawn by the author).

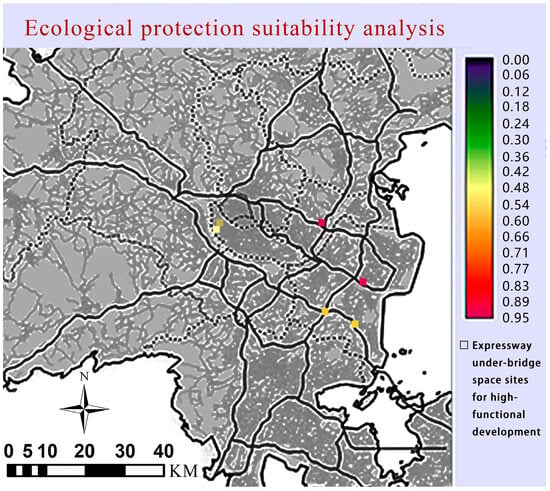

In the ecological protection evaluation, the core factors were the distribution of water systems, basic farmland, and the protection value of vegetation, while the functional development indicators served as constraints. These were aggregated using the ordered weighted averaging (OWA) method (Figure 5). The results showed that only a small number of under-bridge spaces scored high for ecological protection suitability, indicating the limitations of ecological protection in the renovation process.

Figure 5.

Modify the OWA collection result of ecological conservation targets (Image source: Self-drawn by the author).

3.1.3. Decision Analysis and Characteristics of the Underground Space Under the Fuzhou Highway Bridge

- Systematic Division Based on the Dual-Objective Decision Plane

Based on the preliminary data collection, using the indicators of the Fuzhou highway and applying the maximum-minimum method and quantile threshold, the “function development suitable range” (0.27–1) and the “ecological protection suitable range” (0.48–1) were determined. The decision plane was constructed using a geometric driving model to separate the conflict zones and equilibrium points (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Preliminary division of development-protection target decision plane (Image source: Self-drawn by the author).

The results revealed that the conflict zone dividing point was located at (0.854, 1), effectively dividing the decision plane into areas focused on either ecological protection or functional development (Figure 7). The conflict boundary method established based on the ratio of point position to area has achieved the scientific positioning of the dual-objective conflict zone, laying the foundation for subsequent spatial visualization allocation.

Figure 7.

Decision plane conflict zone division (Image source: Self-drawn by the author).

- 2.

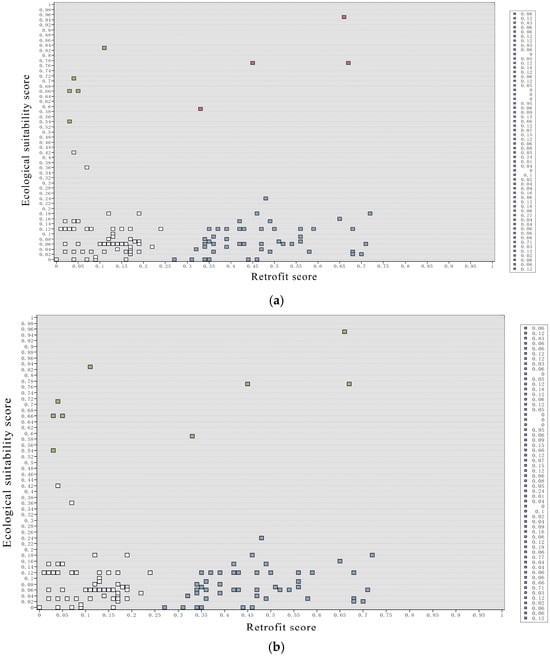

- GIS Scatter Plot Division

To avoid classification deviations caused by imbalanced weight configurations, the ArcGIS scatter plot tool was used to visualize the decision plane. The results show that the dual-objective spatial governance presents a gradient pattern of “functional activation priority zone—ecological conservation core zone—conflict game zone” (Figure 8). Each zone was represented with different colors, such as white for inappropriate areas, blue for development zones, green for conservation zones, and red for conflict areas.

Figure 8.

Scatter plot of spatial function development and ecological protection target suitability of highway under bridge in Fuzhou City (Image source: Self-drawn by the author). (a) Step 1: Initially draw a scatter plot on the decision plane. (b) Step 2: Dispersed Point Map for Conflict Area Division in the Decision Plane. Note: The color of the square blocks in the figure corresponds relatively to the color of the area division in Figure 6.

3.1.4. Preliminary Assessment of Overall Suitability

Finally, by comparing the aggregation results of the ordered weighted averaging method (OWA) with the scores given by 10 experts, it was found that the error was within 10%, which indicates that the preliminary classification method is feasible. The aggregated results were also visualized, providing a comprehensive evaluation of the suitability of under-bridge spaces for functional development (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Preliminary evaluation and analysis of comprehensive suitability of spatial function development under Bridges of Fuzhou highway (Image source: Self-drawn by the author).

3.2. Optimization of Neural Network Model

3.2.1. Model Prediction Results

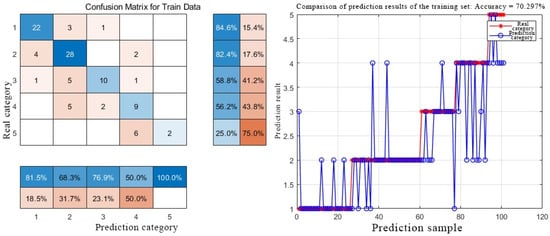

Based on the preliminary MCDM evaluation, this study further employed a BP neural network for suitability prediction. To ensure the reliability of the results, the dataset was divided into a 70% training set and a 30% testing set, with the testing portion serving as unseen data to evaluate the models’ generalization ability.

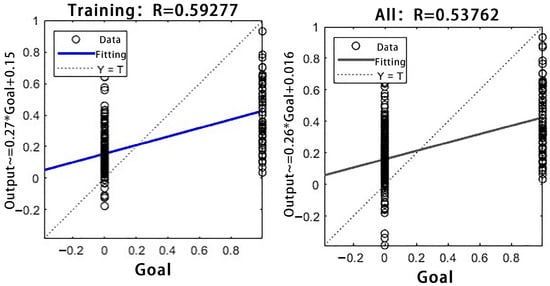

For the traditional BP model, the overall accuracy on the training set was 70.3%, and several high-scoring samples were misclassified (Figure 10). On the unseen testing data, the BP model achieved an accuracy of 68.5%, indicating limited generalization performance.

Figure 10.

BP neural network model training dataset accuracy analysis diagram (Image source: Self-drawn by the author).

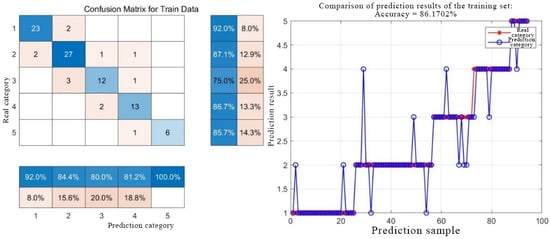

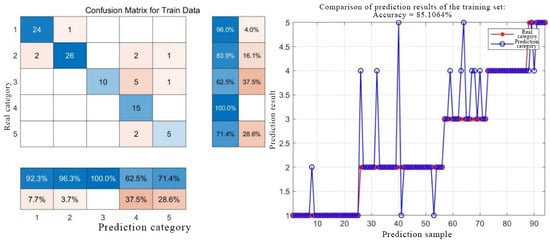

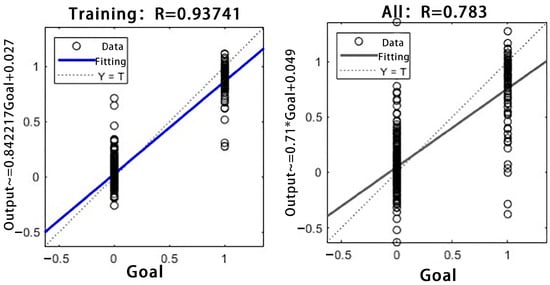

After optimization with the genetic algorithm (GA), the GA-BP model achieved a training accuracy of 86.17%, substantially outperforming the traditional BP model (Figure 11). On the testing set, the GA-BP model reached an accuracy of 82.4%, demonstrating a clear improvement in generalization. The PSO-BP model also achieved strong performance, with a testing accuracy of 79.3%, though slightly lower and computationally less efficient compared with GA-BP (Figure 12).

Figure 11.

GA-BP genetic neural network model training dataset accuracy analysis diagram (image source: self-drawn by the author).

Figure 12.

PSO-BP particle swarm neural network model training dataset accuracy analysis diagram (image source: self-drawn by the author).

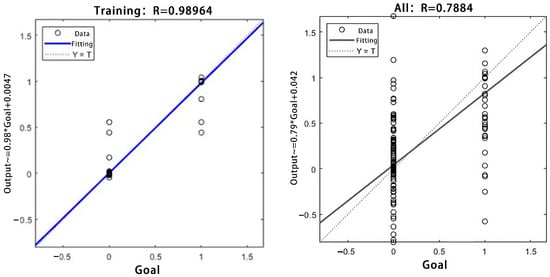

Linear regression analysis further confirms that all models exhibit positive correlations between predicted and observed values, with R coefficients exceeding 0.75. Among them, the GA-BP model performed the best, achieving an R value of 0.9864 on the training set and an overall R of 0.7884, indicating superior predictive accuracy and convergence efficiency.

3.2.2. Comparison Between Single Model and Combined Model

The regression coefficient R reflects the degree of correlation between the predicted values of the model and the actual values. The closer the R value is to 1, the more accurate the prediction results are. When the R value is close to 0, the correlation is weak, and when it is close to −1, there is a negative correlation. The regression analysis results of the three types of models are all positively correlated. After optimization, the correlation coefficient R for all models was above 0.75, indicating good prediction accuracy. Among them, the GA-BP model has the best accuracy and operational efficiency (Figure 13, Figure 14 and Figure 15).

Figure 13.

BP neural network linear regression analysis diagram (image source: self-drawn by the author).

Figure 14.

PSO-BP neural network linear regression analysis diagram (image source: self-drawn by the author).

Figure 15.

GA-BP neural network linear regression analysis diagram (image source: self-drawn by the author).

The optimization algorithms (GA and PSO) significantly improved the BP model by enhancing its global search ability and training efficiency. Among the models, the GA-BP model demonstrated the highest training fit (R = 0.9864) and overall accuracy (R = 0.7884), making it the best model for predicting the suitability of underpass space renovation.

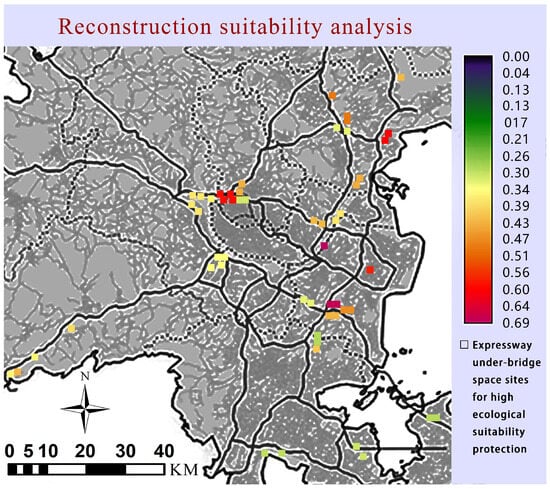

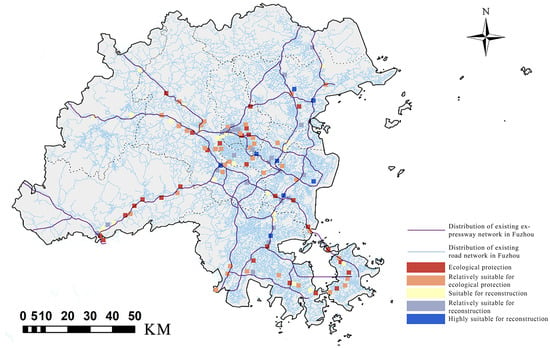

3.3. Comprehensive Suitability Assessment

Based on the optimized GA-BP neural network model, this study performed a comprehensive assessment of the suitability for renovation of 134 underpass spaces along expressways in Fuzhou City. The closer the score is to 1, the higher the suitability for renovation. Combined with the reclassification function of ArcGIS, the results were classified into five categories: “5—very suitable for renovation; 4—relatively suitable for renovation; 3—suitable for renovation; 2—more suitable for ecological protection; 1—ecological protection”. A suitability evaluation map for functional development was generated (Figure 16). At the same time, the renovation characteristics and quantitative indicators of different types of bridge underspaces were summarized (Table 2), providing a scientific reference for subsequent space renovation.

Figure 16.

GA-BP neural network under bridge spatial function development comprehensive suitability evaluation analysis diagram (image source: self-drawn by the author).

Table 2.

Characteristic table of a suitable degree of space reconstruction under highway bridges in Fuzhou City.

By comparing the prediction results of the GA-BP model with the previous suitability analysis map based on Terrset2020, it was found that the GA-BP model is more detailed in judging the suitability of land use transformation: some “relatively suitable for transformation” areas were downgraded to “suitable for transformation”, some “ecological protection” areas were adjusted to “less suitable”, and the overall assessment results were closer to the median value, which conforms to the normal distribution law of numerical judgment. This indicates that, based on the combination of spatial elements and traditional experience, the GA-BP model has achieved a more objective and refined prediction and classification of the suitability of urban highway underpass space transformation, and has improved the scientificity and operability of spatial decision-making.

- Very suitable for renovation (accounting for 6%)

Mainly consisting of under-road spaces of highway hubs, and cross-connecting types, equipped with night lighting, with rich cultural landscapes around (such as temples, traditional villages), low levels of space pollution and noise, high activity enjoyment, convenient transportation and strong safety.

- 2.

- Highly suitable for renovation (accounting for 12%)

The majority are of the cross-connected type and single-sided or double-sided road-facing type. Some have excellent night lighting and cultural resources, and offer good enjoyment and safety during activities. The service radius ranges from 1 to 12 km. These types of spaces are mostly located near residential areas or industrial zones, and have great potential for renovation.

- 3.

- Generally suitable for renovation (accounting for 26.1%)

Most of them are of the cross-connection type. The lighting conditions at night are generally poor. The surrounding cultural resources are scarce. The activity enjoyment level is relatively low. The service range is 1–8 km. The traffic volume is moderate, and the safety is acceptable.

- 4.

- More suitable for ecological protection (accounting for 30.6%)

The more suitable option for ecological protection (accounting for 30.6%) is the underpass space with roads running through it. The lighting at night is poor. Most of these are village side roads, with heavy traffic and a narrow space, resulting in low safety and great difficulty in renovation. Moreover, the surrounding ecological environment is better, making it more suitable for ecological protection.

- 5.

- Ecological protection (accounting for 25.3%)

Mostly located beneath mountains or bodies of water, with poor transportation accessibility, little human interference, and high ecological protection value. Such spaces are mostly classified as ecological protection targets in the model and are not easily developed.

4. Discussion

4.1. Quantitative Model for Assessing the Suitability of Space Renovation Under Bridges

Underpass spaces beneath highways and other infrastructure have long been considered “gray zones,” with no systematic evaluation framework to address the tension between ecological protection and functional development. This study improves suitability evaluations by incorporating intelligent optimization algorithms into the process. The combination of multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) and optimized BP neural networks allows for more precise and comprehensive assessments, filling the gap where traditional methods fall short. The results confirm that the GA-BP model outperforms the traditional BP model, particularly in terms of global search ability and prediction accuracy. The GA-BP model can effectively avoid the problem of getting stuck in local optima, improving the reliability of classification and suitability evaluation in complex index systems [47,48,49]. This enhancement is in line with previous studies, which show that optimized neural networks, such as those enhanced by genetic algorithms, offer superior performance in various environmental and spatial assessments. The PSO-BP model also performed well in terms of convergence speed and computational efficiency, particularly in large datasets. It is more suitable for scenarios with high computational demands and large-scale data [50,51,52]. Finally, an innovative GA-BP neural network model was proposed, which is more suitable for the suitability evaluation model of the under-bridge space. This model fills the gap in the under-bridge space renovation process, where there is a lack of systematic coupling analysis between “ecological constraints and functional driving forces”.

4.2. Evaluation of the Suitability of Space Renovation Under Bridges

The underpass spaces close to water systems, mountains, and farmlands are more suitable for ecological protection. These areas have higher vegetation coverage and provide essential habitat value, making them ideal candidates for ecological restoration [53]. The results reaffirm the principle of “prior protection and moderate development” in urban planning and ecological engineering. The tension between space utilization for transportation and urban development, versus ecological preservation, must be carefully managed [54]. The results of this study highlight key factors influencing the suitability of underpass spaces for renovation. These results are consistent with previous findings, where high traffic volumes and advantageous locations make underpass spaces highly adaptable for commercial, recreational, and green infrastructure uses [37,40,55]. Furthermore, this study also shows that the adaptability of transformation, environmental quality, and safety are positively correlated with functional development goals but negatively correlated with ecological protection goals. This reflects the inherent conflict between maximizing space utilization for human activities and maintaining ecological balance. It is essential to consider both aspects when planning the renovation of underpass spaces to ensure sustainable and balanced development.

4.3. Differential Utilization Potentials of Under-Bridge Space Typologies

The spatial morphology, traffic context, and surrounding land use attributes of different under-bridge space typologies fundamentally shape their potential for functional redevelopment or ecological restoration. Under-bridge spaces classified as “moderately suitable,” “highly suitable,” or “very suitable”—such as expressway hub-type, cross-connected, and single- or double-sided roadside types—typically possess favorable spatial dimensions, accessibility, and adjacent facilities, thus providing a solid basis for multifunctional redevelopment [56]. In such areas, planning strategies may incorporate the needs of nearby residential or industrial communities by improving nighttime lighting and surveillance, optimizing traffic organization, and enhancing pedestrian and slow-traffic accessibility. These measures can support the creation of community fitness areas, convenient parking facilities, or integrated greenways. At the same time, considering that under-bridge environments are often constrained by noise, vehicle emissions, and airborne particulates, reinforced noise mitigation and pollution control measures are essential to ensure safety and comfort in public activities [57].

In contrast, under-bridge spaces classified as “more suitable for ecological protection”—often characterized by linear road-through configurations with limited lighting, heavy traffic volumes, constrained spatial scale, and low pedestrian presence—face greater challenges for functional redevelopment and should prioritize ecological restoration and green infrastructure. Strategies may include planting native shade-tolerant and pollution-resistant vegetation to establish ecological buffer zones [58], installing sound barriers to reduce traffic noise, preserving existing ecological substrates, and modestly enhancing pedestrian accessibility without large-scale hardscape interventions [59]. For areas with poor accessibility and high ecological sensitivity, ecological value should be prioritized by incorporating these spaces into urban or regional ecological corridors, strictly limiting development activities, and establishing ecological monitoring nodes to minimize human disturbance and reinforce biodiversity conservation functions [60].

This differentiated approach to utilization and protection helps avoid uniform, undifferentiated redevelopment and instead respects the intrinsic environmental attributes of each spatial type. Under the context of rapid urban expansion and increasingly dense transportation infrastructure, typology-based spatial management offers a more efficient and sustainable model for under-bridge space governance, enabling targeted functional renewal or ecological restoration tailored to site-specific conditions (Figure 17).

Figure 17.

Suggested classification map for spatial planning under highway bridges.

4.4. Planning Implications

The evaluation framework and renovation strategies proposed in this study can be integrated with national low-carbon policies, with practical value enhanced by quantifying carbon sequestration under bridges. Ecologically protected spaces can increase vegetation cover through soil improvement and native shade-tolerant plants, while artificial wetlands near water bodies provide combined benefits for carbon storage and water quality [61,62]. Functionally redeveloped spaces can adopt green building principles, low-carbon materials, and energy-efficient facilities, complemented by bicycle and pedestrian networks connected to public transport to support low-carbon mobility.

Under the principle of maximizing existing urban space, under-bridge planning should follow “intensive use and functional integration.” Experiences from the Zhonghuan Bridge renovation in Shanghai [62] show that fragmented areas can be consolidated into composite public service nodes combining leisure, parking, and sports. Collaborative governance mechanisms combining governmental coordination and multi-stakeholder participation [63] can ensure alignment with broader urban renewal strategies, prevent fragmented development, and enhance spatial coherence.

As the research on the space beneath urban elevated bridges has been on the rise, this study innovatively takes the space beneath highway bridges as the research object. Through actual investigations and model verification, it classifies the space beneath highway bridges that can be developed for functions and ecological protection. The research results show that the bridge spaces at highway hubs, single or double-sided bridge approaches, and cross-connection types have better development conditions and are suitable for accommodating diverse functional renovation demands. These spaces have high activity enjoyment, convenient transportation, and strong safety. They are mostly located near residential areas or industrial zones and have great potential for renovation. The results of this study link the types of highway bridge spaces with functional renovations and ecological protection for the first time, providing a research basis for the further functional division of the space beneath highway bridges in the future.

5. Conclusions

This research established an integrated assessment framework for highway bridge underpass environments by integrating multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) methodologies with backpropagation (BP) neural networks enhanced through genetic algorithms (GA) and particle swarm optimization (PSO) techniques. Employing 134 highway bridge underpass in Fuzhou City as empirical examples, the study derived the following key findings:

(1) The model with the best performance is the GA-BP model.

Among the models tested, the GA-BP model yielded the highest classification accuracy. It should be noted, however, that this result merely indicates that GA-BP is the most suitable approach for the specific classification task in this study, rather than implying broader or universal superiority. This model was therefore selected for subsequent analysis to ensure that the evaluation results align with the characteristics of the dataset and the objectives of the classification framework.

(2) Suitability is jointly influenced by transportation accessibility, safety and ecological background.

The space under bridges with good accessibility and geographical advantages is more suitable for commercial, leisure and green space construction, while areas close to water bodies, mountains and farmlands are more suitable for ecological protection and restoration. Functional orientation indicators are positively correlated with suitability, while ecological protection goals show a significant negative correlation, reflecting the need for a careful balance between development and ecology.

(3) Different types of spaces have differentiated utilization potential.

The under-bridge spaces of hub-type, single-sided/double-sided approach bridge types and cross-connection-type bridges have favorable development conditions. This study simultaneously proposes quantitative threshold indicators for functional development and ecological protection, providing a reference for the classified utilization and scientific management of the space under Bridges.

This research represents the inaugural systematic application of GA-BP and PSO-BP neural network models in assessing the suitability of spaces beneath highway bridges. It conducts a comparative analysis to validate the enhancement effects of these optimization algorithms on prediction accuracy and convergence efficiency, thereby overcoming the constraints of conventional multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) approaches in classification accuracy. Furthermore, the study establishes quantitative critical thresholds for functional development, offering a more practical foundation for the scientific utilization of under-bridge spaces.

Future research should integrate dynamic ecological process models and multiscale ecological network analyses, combining scenario simulations and policy experiments to explore the interactions between under-bridge space renovation and ecosystem service evolution. A “seasonal dynamics” framework could be employed to quantify the influence of seasonal factors—such as precipitation, temperature, vegetation cover, pollutant dispersion, and human activity patterns—on suitability levels and transition thresholds. Additionally, functional typologies could be refined according to surrounding land use and demand (e.g., commercial, recreational, or ecological park uses), thereby enhancing the contribution of under-bridge spaces to green infrastructure, ecological corridors, and urban resilience, and providing forward-looking guidance for sustainable urban ecological planning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.H. (Yiwei Han); methodology, S.Z.; software, S.Z., X.Z. and Y.C.; validation, S.H.; formal analysis, Y.H. (Yiwei Han) and S.H.; investigation, S.H., S.Z., X.Z. and Y.C.; resources, Y.H. (Yuanhao Huang) and Z.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.H. (Yiwei Han); writing—review and editing, Y.H. (Yiwei Han) and S.H.; supervision, W.R.; project administration, D.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fujian Provincial Department of Transport and Fujian High-speed Group (Grant No. JC202324 and 202316GS) and the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Youth Foundation, Ministry of Education, China (Grant No. 20YJC760079).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Committee of the College of Landscape Architecture and Art, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University (protocol code JC202324 and 10 June 2024 of approval).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Zhenhai Wu and Yuanhao Huang were employed by the company Fujian Provincial Department of Transport and Fujian High-speed Group. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Trancik, R. Finding Lost Space: Theories of Urban Design; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.J.; Zhang, W.H.; Zhang, S.Z.; Zhu, Y.X. Analysis on Three Ways for the Reuse of Urban Corner Space under Viaduct. Urban. Archit. 2023, 20, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.N. Study on the Landscape Construction Under the South Approach Bridge of Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge Basedon the Concept of Landscape Ecology. Master’s Thesis, Hebei University of Architecture and Engineering, Zhangjiakou, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Z.W.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.Z. The influence of urban elevated bridges on the dispersion and distribution of particulate matter. China J. Highw. Eng. 2022, 35, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobrino, J.A.; Oltra-Carrió, R.; Sòria, G.; Bianchi, R.; Paganini, M. Impact of spatial resolution and satellite overpass time on evaluation of the surface urban heat island effects. Remote Sens. Environ. 2011, 117, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.J. Numerical Simulation of the Air Environment in the Street Canyon at the Crossroads Of Urban Roads with Viaducts. Master’s Thesis, Taiyuan University of Technology, Jinzhong, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vlassova, L.; Perez-Cabello, F.; Nieto, H.; Martín, P.; Riaño, D.; Riva, J.d.l. Assessment of Methods for Land Surface Temperature Retrieval from Landsat-5 TM Images Applicable to Multiscale Tree-Grass Ecosystem Modeling. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 4345–4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.-W.; Zhang, Y.-H. Reserch on Vegetation Change in Su-Hua Expressway based on GF-1 Remote Sensing Data. Highway 2024, 69, 372–378. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, X.; Shao-huai, Y.; Fei, Y. Monitoring and Analysis of Typical Vegetation Parameters in Expressway Road Area Based on Time Series Sentinel-2 images. Highway 2023, 68, 344–354. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, L.; Li, B.S.; Pu, F.C.; Gu, X.F.; Wang, X.W. Evaluation of DynamicL and Scape Along Jiuzhi-Maerkang Expressway Based on Digital Twin Scenari. Highway 2024, 69, 205–213. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Seven Cases of Renovation and Upgrading of Bridge Underspace Abroad. Available online: https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_8574101 (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Anonymous. Under Bridges Vol. 2: What Can a City Do with Four Spaces the Size of Central Parks Under Bridges? Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1808689325204881466&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Anonymous. Under the Bridge Space Vol.3: Skating, Boating, Running, Daydreaming. Can These Happen in the Space Under the Bridge? Available online: https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_8676960 (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Yin, W. “Scrap Materials” Reimagining the Urban Landscape: A Study on Micro-Updates in Urban Design—The Case of the Underground Space Under the Garden Bridge in Xinchanggang Central Area. Housing 2023, 163, 149–151. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Y. The Research on Innovative Commercial Space and Landscape Under Urban Viaduct. Master’s Thesis, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.M.; Zhou, H.L.; He, Y.Q. Study on the Renewal of the Space Under the Bridge Based on Behavioral Requirements—Taking the Chengdu Fuqing Sports Space as an Example. Intell. Build. City Inf. 2023, 1, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, M.; Matthews, K.; Jones, D. Vegetated Fauna Overpass Disguises Road Presence and Facilitates Permeability for Forest Microbats in Brisbane, Australia. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 5, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatriz, P.D.A.; Thiago, S.F.S. Beyond the park and city dichotomy: Land use and land cover change in the northern coast of São Paulo (Brazil). Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 189, 352–361. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, M.E.; Wilson, S.K.; Jones, D.N. Vegetated fauna overpass enhances habitat connectivity for forest dwelling herpetofauna. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2015, 4, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardi, R.; Mittermeier, J.C.; Roll, U. Combining culturomic sources to uncover trends in popularity and seasonal interest in plants. Conserv. Biol. 2021, 35, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.H. Space Utilization and Landscape Under Urban Elevated Bridges (Revised Edition); Huazhong University of Science and Technology Press: WuHan, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Akbarian Ronizi, S.R.; Mokarram, M.; Negahban, S. Investigation of Sustainable Rural Tourism Activities with Different Risk: A GIS-MCDM Case in Isfahan, Iran. Earth Space Sci. 2023, 10, e2021EA002153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.; Paul, I.; Sarkar, B. Geotourism site suitability assessment by a novel GIS-based MCDM method in the Eastern Duars region (Himalayan foothill) of West Bengal, India. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Mondal, M.; Sarma, U.S.; Podder, S.; Gayen, S.K. Tourism Suitability Assessment in Malbazar Block using principal component analysis and analytical hierarchy process. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, K.H.; Woldemariam, G.W. GIS-based ecotourism potentiality mapping in the East Hararghe Zone, Ethiopia. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.L.; Wang, Q.; Wei, D.J. A Novel Hybrid Model Combining BPNN Neural Network and Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2024, 17, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.L.; Guo, X. Ecological environment value assessment and ecological civilization in the Changjiang River basin. Water Environ. J. 2024, 38, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, K.; Han, Y. Ecological security assessment of urban park landscape using the DPSIR model and EW-PCA method. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 31301–31321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Wen, X.; He, P. Surface Soil Moisture Estimation Using a Neural Network Model in Bare Land and Vegetated Areas. J. Spectrosc. 2023, 2023, 5887177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, L.; Qian, X.; Jian, D. Research and application of GIS-based multiple-criteria decision making method for dual objectives. J. Chongqing Univ. 2021, 44, 161–170. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Li, Q.; Guo, L.; Ding, G. Research on the Summer Micro-Environment and Human Comfort under Elevated Bridges in Hot and Humid Area. J. Xi’an Univ. Archit. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, X.H. Potential Tapping and Utilization of Remaining Space in the Process of Urban Renewal: A Case Study of Underbridge Space. Landsc. Archit. 2023, 30, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, J.W. Study on Humanize Design of Urban Overpass Accessory Space. Master’s Thesis, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, M. Research on the Spatial Landscape Planning and Design of the Urban Expressway Viaduct—Take Xi’an as an Example. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Han, C.P.; Gao, L.; Zhao, J.J.; Bu, T.M. Analyzing Landscape Preference in Under-Bridge Spaces Based on Different Travel Modes: A Study on Urban Viaduct Landscapes in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2025, 19, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangkoog, N.A.M.; Kyu, L.J. A study for utilization of under space of urban bridge. J. Korea Intitute Spat. Des. 2012, 7, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, J.; Xu, H.; Zheng, J.; Luo, M.; Zhou, X. Commercial Value Assessment of “Grey Space” under Overpasses: Analytic Hierarchy Process. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2018, 2018, 4970697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Jin, F.J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, W. Distance-decay pattern and spatial differentiation of expressway flow:An empirical study using data of expressway toll station in Fujian Province. Prog. Geogr. 2018, 37, 1086–1095. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, L.; Tong, L. Research on residents activity survey and satisfaction evaluation on public open space of rural areas in severe cold regions. China Sci. 2015, 10, 1741–1747. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.T.; Wang, J.Y.; Zhao, D.W.; Rong, J.H. Research on Under-Bridge and its Public Demand Evaluation in Mega City Based on Multi-Source Data: A Case Study of Beijing. J. Hum. Settl. West China 2023, 38, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Study on the Quality of Urban Overhead Visual Space. Master’s Thesis, Hefei University of Technology, Hefei, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, K.Y.; Cinn, E. A Study on the Strategies for the Vitalization of the Spaces under Han River Bridges. J. Korea Intitute Spat. Des. 2019, 14, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.Y.; Li, S.Y.; Liu, C. Challenges and Potentials: Environmental Assessment of Particulate Matter in Spaces Under Highway Viaducts. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Cai, C.X.; Min, L.; Peng, X.-L. Study on methodology of ecological suitability assessment ofvurban landuse: An example of Pingxiang. Geogr. Res. 2007, 26, 782–788+859. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Z.F.; Huang, H. Evaluation and Characteristics Analysis of the Production living-ecological Space Suitability in Chenzhou Prefecture. Land Resour. Her. 2023, 20, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, F.F.; Wu, N.Y.; Yangjian, H. Land Suitability Evaluation and Development Planning in Lingnan Hilly Areas: A Case Study of the Large Scientific Facilities Cluster in Guangming Science City. Intell. City 2022, 8, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.W.; Liu, C.; Tang, Y.; Gong, C. A GA-BP Neural Network Regression Model for Predicting Soil Moisture in Slope Ecological Protection. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Cao, J.; Chao, L.; Li, Y. Study on Comprehensive Assessment of Water-Resource Safety Based on Improved TOPSIS Coupled with GA-BP. J. Coast. Res. 2020, 105, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Yang, X.; Wu, Y.; Fang, K. Adaptability assessment of the Enning road heritage district in China based on GA-BP neural network. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.J.; Fan, Z.Y. Evaluation of urban green space landscape planning scheme based on PSO-BP neural network model. Alex. Eng. J. 2022, 61, 7141–7153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z. WSN Localization Technology Based on Hybrid GA-PSO-BP Algorithm for Indoor Three-Dimensional Space. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2020, 114, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Peng, F. Network traffic prediction algorithm research based on PSO-BP neural network. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Systems Research and Mechatronics Engineering (ISRME), Zhengzhou, China, 11–13 April 2015; pp. 1239–1243. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Qin, D.; He, X.; Wang, C.; Yang, G.; Li, P.; Liu, B.; Gong, P.; Yang, Y. Spatial and Temporal Changes in Land Use and Landscape Pattern Evolution in the Economic Belt of the Northern Slope of the Tianshan Mountains in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafieian, M.; Kianfar, A. Guiding public policy in gray spaces: A meta-study on land ownership conflicts (1987–2022). Cities 2024, 147, 104803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Xu, X.; Lu, Y.; Li, L. Research of Interaction Mechanism between Comprehensive Transport and Territorial Space. Railw. Transp. Econ. 2025, 47, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pochop, M.; Konecna, J.; Podhrazska, J.; Kyselka, I. Support of Development of Landscape Not-Production Functions in Spatial Planning and Land Consolidation. In Proceedings of the Conference on Public Recreation and Landscape Protection—With Nature Hand in Hand, Krtiny, Czech Republic, 1–3 May 2016; pp. 249–256. [Google Scholar]

- Komarzyńska-Świeściak, E.; Kozlowski, P. The acoustic climate of spaces located under overpasses in the context of adapting them for outdoor public events—A pilot case study. Bud. I Archit. 2021, 20, 63–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, J.; Gochfeld, M.; Brown, K.G.; Ng, K.; Cortes, M.; Kosson, D. The importance of recognizing Buffer Zones to lands being developed, restored, or remediated: On planning for protection of ecological resources. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health-Part A-Curr. Issues 2024, 87, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K. Research on the Ecological Strategies in Landscape Design and Planning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Green Building, Materials and Civil Engineering (GBMCE 2011), Shangri La, China, 22–23 August 2011; pp. 1805–1808. [Google Scholar]

- Sobhani, P. Analysis of ecological network structure and biological function continuity in Jajrud Protected Area. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 27, 100741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Du, X. Green Renewal Strategies for Urban Elevated Grey Transportation Infrastructure: A Case Study of the Space Under the Ningbo-Dongguan Expressway in Wenzhou. Cent. China Archit. 2025, 43, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, S. Exploration of Underground Space Development and Utilization from the Perspective of Urban Renewal: A Review of “Urban Renewal and Planning and Design of Underground Space Expansion and Renovation”. Mod. Urban Stud. 2025, 4, 123. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, Y. Renewal Strategies and Practices of Urban Infrastructure under the Concept of Green Development. Planner 2025, 41, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).