Abstract

Cities around the world are facing growing challenges related to climate change, urban sprawl, infrastructure strain, and digital transformation. In response, smart and sustainable urban development has become a global focus, aiming to integrate technology and environmental stewardship to improve the quality of life. The smart and sustainable city concept is typically applied at the city scale; however, its impact is most tangible at the neighborhood level, where residents interact directly with infrastructure, services, and community spaces. A variety of global frameworks have been developed to assess sustainability and technological integration. However, these models often fall short in addressing localized needs, particularly in regions with distinct environmental and cultural contexts. In Saudi Arabia, Vision 2030 emphasizes livability, sustainability, and digital transformation, yet there remains a lack of tailored tools to evaluate smart and sustainable progress at the neighborhood scale. This study develops HayyScore, a localized evaluation framework and prototype digital platform developed to assess neighborhood performance across five core categories: (i) Environment and Urban Resilience, (ii) Smart Infrastructure and Governance, (iii) Mobility and Accessibility, (iv) Quality of Life and Social Inclusion, and (v) Economy and Innovation. The HayyScore platform operationalizes this framework through an interactive web-based tool that allows users to input data through structured forms, calculate scores, receive category-based and overall certification levels, and view results through visual dashboards. The methodology involved a comprehensive review of global frameworks, expert input to define localized indicators, and iterative prototyping of the platform using Python 3.13.5 and Streamlit 1.45.1. To demonstrate its practical application, the prototype was tested on two Saudi neighborhoods: King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center (KAPSARC) and King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals (KFUPM). Key platform features include automated scoring logic, category weighting, certification generation, dynamic performance charts, and a rankings page for comparing multiple neighborhoods. The platform is designed to be scalable, with the ability to add new indicators, support multilingual access, and integrate with real-time data systems in future iterations.

1. Introduction

The rapid growth of urban regions has elevated environmental, social, and economic stresses [1], making it essential to establish frameworks for urban planning and development. Issues such as unsustainable energy consumption, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, air and water pollution, insufficient mobility systems, and social inequality already affect existing built environments [2]. These challenges are intensified by the presence of outdated, non-digital infrastructures that limit the effective operation and management of urban systems [3].

In response to these complexities, the concept of smart and sustainable cities has emerged as a fundamental approach to urban development by integrating technology, sustainability, and efficient resource management to enhance the quality of life [2]. Sustainable cities prioritize environmental stewardship, energy efficiency, and community well-being, while smart cities leverage digital technologies, data analytics, and Internet of Things (IoT) solutions to optimize urban services [4]. Combining the principles of sustainable cities and smart cities will ensure that the needs of current and future generations are met [5]. As these cities continue to grow, neighborhoods become essential units in translating larger urban sustainability initiatives into practical and localized action [6]. By applying these principles at the neighborhood scale, smart and sustainable neighborhoods ensure that urban growth aligns with long-term ecological and socio-economic goals. These neighborhoods play a crucial role in advancing urban sustainability by addressing environmental challenges, conserving resources, and promoting social inclusivity [7].

Saudi Arabia is currently undergoing a transformative phase under Vision 2030, which prioritizes sustainable urban development and the integration of smart city concepts [8]. This makes it crucial to create a framework that ensures smart and sustainable development [9]. The nation’s commitment to technology-driven and environmentally responsible urbanization is evident in large-scale initiatives such as the NEOM megacity, the Red Sea Project, ROSHN’s residential developments, and the Saudi Green initiative [10]. These projects aim to redefine urban living by incorporating cutting-edge technologies and sustainable design principles.

Despite the Kingdom’s efforts, there is a lack of standardized frameworks for assessing and benchmarking smart and sustainable city development in Saudi Arabia. Existing rating systems, such as Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design Neighborhood Development (LEED-ND) [11,12], Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Methodology (BREEAM) Community [13], Qatar Sustainability Assessment System (QSAS), and MOSTADAM, primarily focus on sustainability without fully accounting for the country’s unique cultural, environmental, and urban characteristics. For instance, MOSTADAM, Saudi Arabia’s national rating system, evaluates sustainability performance mainly at the building scale but lacks indicators for digital infrastructure, data-driven governance, or smart mobility. Similarly, many urban projects, including Vision 2030 giga projects, are guided by global sustainability benchmarks rather than standardized smart and sustainable benchmarks.

While models like the Smart City Index and ISO 37122 [14] provide valuable global benchmarks, they do not sufficiently align with the distinct urban and socio-economic context of Saudi Arabia. Consequently, Saudi neighborhoods are evaluated inconsistently, relying on fragmented criteria that overlook the integration of smart technologies and localized sustainability priorities. Currently, there is no comprehensive, localized framework that evaluates both the smartness and sustainability of neighborhoods within the Saudi context.

This study aims to address this problem by developing a comprehensive platform that evaluates smart and sustainable neighborhoods in Saudi Arabia. The objectives of this study are to:

- Develop a localized framework for assessing smart and sustainable neighborhoods.

- Design a user-friendly platform to evaluate and rank neighborhoods based on their performance.

By focusing on the neighborhood scale, this research provides a more detailed and practical approach to urban development and ensures that projects align with Vision 2030’s sustainability and smart city goals. The proposed platform will serve as a standardized assessment tool, enabling policymakers, real estate developers, and urban planners to make informed, data-driven decisions. It will integrate key environmental, technological, and socio-economic factors to ensure that urban developments are both smart and sustainable.

This study addresses a significant gap in the field of urban planning in Saudi Arabia. This study offers urban planners, developers, and government officials a structured methodology for guiding future developments by creating an evaluation model tailored to the region. The framework will aid in enhancing resource efficiency, upgrading digital infrastructure, and encouraging sustainable growth, ensuring that new neighborhoods align with Saudi Arabia’s evolving urban priorities.

This research not only impacts the nation but also adds to the worldwide conversation about smart and sustainable cities by providing a framework that can be adapted to other Gulf and Middle Eastern nations facing similar urbanization issues. It also aligns with international sustainability goals, such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), specifically Goal 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities. By bridging the gap between sustainability and smart city development, this study promotes data-driven, technology-enabled urban planning, encouraging more resilient, efficient, and livable communities in Saudi Arabia.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the literature on smart and sustainable neighborhoods, analyzing existing rating systems and their applicability to Saudi Arabia. Section 3 outlines the research methodology, framework development, and the design of the proposed digital platform. Section 4 presents the development of the HayyScore framework and platform, including indicator selection, evaluation methods, and the certification system. Section 5 discusses the findings in relation to existing literature and highlights the framework’s relevance, strengths, and potential applications. Finally, Section 6 concludes the study.

2. Literature Review

This literature review examines smart and sustainable urban development, focusing on the integration of digital technologies and sustainable design to address urbanization challenges. This review aims to thoroughly assess existing global and regional frameworks, identify their limitations, and justify the development of a new model aligned with the objectives of Saudi Vision 2030.

2.1. Smart and Sustainable Neighborhoods

The concept of smart and sustainable cities is most effectively applied at the neighborhood scale, given its manageable size, its potential for experimenting with sustainability initiatives, and a high level of interaction between residents [15]. Neighborhoods are where people truly experience urban life through living, working, and interacting with their communities. As such, smart and sustainable neighborhoods represent smaller, more focused reflections of what entire cities aim to achieve. Smart neighborhoods use technological tools to improve the functionality of daily services and infrastructure. These tools help monitor and manage systems like energy, mobility, and waste to make neighborhoods more efficient and responsive. In contrast, sustainable neighborhoods prioritize long-term environmental health, social equity, and community well-being [16]. This is evident in strategies promoting renewable energy use, emissions reduction, and walkability. When combined, these two dimensions work together to create livable, resilient, and adaptable neighborhoods that are supported by digital tools and focused on environmental, social, and economic sustainability goals.

2.1.1. Sustainable Neighborhoods

Sustainable neighborhoods represent a vital building block in the pursuit of urban sustainability. They serve as localized models where environmental, social, and economic considerations intersect at a scale that is manageable and impactful. These neighborhoods focus on greener spaces and energy-efficient buildings while fostering inclusive communities, promoting health and well-being, and encouraging civic participation. As cities worldwide deal with the consequences of climate change, resource scarcity, and urban inequality, neighborhoods are seen as a key place for transformative action [17,18].

At the core of sustainable neighborhood planning is the integration of the three pillars of sustainability: environmental, social, and economic factors, with a growing recognition of a fourth, i.e., institutional pillar, which emphasizes governance, transparency, and stakeholder inclusion [17,19]. These neighborhoods strive to balance livability and resilience by encouraging mixed land uses, walkability, local economic vitality, access to public spaces, and infrastructure that supports ecological goals. Moreover, they often promote innovation in mobility, renewable energy integration, waste management, and community engagement [20].

Despite broad agreement on what sustainability means in theory, real-world implementation remains fragmented. As several studies indicate, sustainable neighborhood initiatives often reflect the priorities of the developers or municipalities behind them. This may lead to an overemphasis on certain aspects, such as urban form or green technologies, at the expense of social inclusion or participatory governance [17,21]. For instance, large-scale developments may prioritize energy efficiency and architectural esthetics, while smaller, community-led projects are more likely to incorporate local participation and social cohesion. This divergence reveals a gap between the ideals of sustainability and what is achieved in practice.

Another challenge is the expansion of frameworks and terminologies, such as eco-neighborhoods, green developments, and resilient communities, each highlighting different sustainability goals without always achieving a comprehensive balance [22,23]. Some rely heavily on certification systems like LEED-ND or BREEAM, which provide useful standards but may not fully address the cultural, economic, or climatic contexts in which neighborhoods exist [24]. As a result, the success of sustainable neighborhoods often depends on how well these principles are adapted to local conditions, with a focus on stakeholder engagement and long-term impact [16].

2.1.2. Smart Neighborhoods

Smart neighborhoods are a growing area of interest in both research and real-world urban development. These neighborhoods bring together technology, sustainability, and community engagement at the scale where people experience city life most directly. At their foundation, smart neighborhoods are urban areas where digital tools like sensors, connected infrastructure, mobile applications, and data platforms are integrated to improve everyday living, environmental efficiency, service delivery, and local governance [25].

However, smart neighborhoods are not just about being technologically advanced. Their true value lies in how well they serve the people who live in them. A smart neighborhood uses innovation not only to optimize infrastructure, but also to promote inclusion, safety, sustainability, and participation [26]. Technology becomes a tool—not an end goal—for enhancing social connection, improving access to services, and fostering a stronger sense of place.

Recent research highlights how residents themselves are key to making neighborhoods smart. In a study conducted in Hong Kong [26], the author found that even simple digital tools such as neighborhood apps or group messaging platforms can play a transformative role when used to coordinate activities, share local news, or strengthen social ties. This process reflects how people actively shape smartness through everyday interactions, rather than relying only on top-down technology deployments.

To guide implementation and track progress, researchers have begun developing evaluation frameworks. Another study [27], for example, proposes a practical method for measuring neighborhood-level smartness based on key performance indicators (KPIs) that include digital infrastructure, environmental performance, resident satisfaction, and governance. His work also introduces a five-level maturity scale, which allows planners to evaluate where a neighborhood stands and what improvements are needed. This kind of structure helps move smart neighborhoods from abstract vision to measurable reality.

The environmental role of smart neighborhoods is also receiving increasing attention. Neighborhoods are found to be ideal spaces for promoting low-carbon lifestyles through smart mobility, energy-efficient buildings, and real-time monitoring of resources [7]. But these outcomes are most likely to succeed when residents feel a strong sense of ownership over their neighborhood. Factors like community trust, local pride, and place attachment are just as important as the presence of advanced technology [28].

Despite these advances, the field of smart neighborhoods is still developing. The current smart city research focuses on city-wide strategies, with fewer frameworks specifically designed for neighborhoods [29]. Additionally, the lack of a universal definition of “smart” continues to create confusion in both academia and policy circles. Many smart initiatives remain pilot projects or isolated experiments, with limited integration into broader urban planning systems.

2.2. Urban Sustainability Rating Systems

Urban sustainability rating systems have become essential tools for guiding and evaluating the environmental and social performance of neighborhoods and cities. These systems are built upon the three core pillars of sustainability: environmental protection, social inclusion, and economic development [30]. They provide structured frameworks and standardized indicators that enable evidence-based decision-making to support long-term sustainable development [31]. The most prominent rating systems include:

2.2.1. Global Urban Sustainability Rating Systems

LEED for Neighborhood Development (LEED-ND)

Developed by the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC), LEED-ND is among the most widely recognized sustainability evaluation systems for neighborhoods. It assesses urban developments based on various criteria, such as smart location, neighborhood design, and green infrastructure [31]. While LEED-ND offers a comprehensive sustainability assessment, it does not fully incorporate smart technology indicators such as IoT, AI, and real-time data monitoring, which are crucial for modern smart neighborhood evaluations [24]. There have been efforts to digitize LEED-ND, with tools such as the LEED online platform that help users track projects, submit documentation, and gain certification. However, the system still predominantly focuses on sustainability, with little integration of the technological advancements needed for smart city evaluations.

BREEAM Communities

BREEAM communities, developed in the UK, provide a sustainability assessment method focusing on community design, environmental performance, and resource efficiency. It promotes low-carbon development, biodiversity conservation, and sustainable transportation [32]. Though it is extensively utilized in Europe and elsewhere, its emphasis is primarily on environmental sustainability, with minimal incorporation of smart technologies or sophisticated digital solutions. BREEAM Communities, similar to LEED-ND, has worked to implement digital processes. With the introduction of the BREEAM online platform, users can digitally monitor their projects, access resources, and submit documentation. Nonetheless, the system continues to prioritize sustainability criteria, with no formal assessment of digital infrastructure, data integration, or smart service delivery [13].

2.2.2. Gulf Urban Sustainability Rating Systems

QSAS

QSAS is a sustainability rating system developed specifically for the Gulf region, and it is particularly relevant for Saudi Arabia due to its emphasis on the climatic and socio-economic challenges faced by Gulf countries. QSAS evaluates sustainability based on multiple criteria, including energy efficiency, water conservation, and urban connectivity. It is designed for the hot desert climate of the region and seeks to enhance the environmental performance of buildings and neighborhoods in a context that is culturally and environmentally specific [21]. QSAS, however, lacks the integration of advanced technologies like IoT and real-time monitoring, which are essential for assessing smart neighborhoods within the framework of contemporary urbanization. The system’s paper-based format limits its adaptability and responsiveness to dynamic urban data flows.

MOSTADAM

MOSTADAM is Saudi Arabia’s localized sustainability rating system, developed to align with the urban development objectives of Vision 2030. Launched with support from the Ministry of Housing and the Cleantech consulting firm Alpin, MOSTADAM aims to improve water and energy sustainability across the country [33]. It is specifically designed to address Saudi Arabia’s regional needs, local climate, and environmental conditions [34]. However, MOSTADAM has not yet incorporated smart technologies into its evaluation framework. Its main focus is on environmental sustainability, resulting in a significant gap in the evaluation of smart urban development. The absence of digitalization and urban data management tools limits its usefulness in guiding the smart transformation of neighborhoods.

Pearl Rating System

The Pearl Rating System is the United Arab Emirates (UAE)’s sustainability framework for buildings and communities. It emphasizes resource efficiency, cultural identity, and livability in arid environments. The system includes requirements for water, energy, and material conservation, but similar to QSAS and MOSTADAM, it does not incorporate smart technology benchmarks or real-time monitoring mechanisms [35].

2.3. Smart City Tools

While numerous frameworks have been developed to assess the sustainability of neighborhoods, there is still a lack of comprehensive frameworks specifically designed to evaluate or implement neighborhood-level smartness [27]. Sustainability rating systems have long been used to measure environmental and urban performance, but smart city assessment frameworks have emerged more recently to capture how cities leverage technology, data, and innovation to enhance urban living. The smart city concept is still evolving, and there is no universally accepted definition. However, it is broadly understood that smart cities employ information and communication technologies (ICT) to improve service delivery, enhance citizen well-being, promote sustainability, and drive economic development [36]. The most widely used smart city assessment tools and frameworks include:

2.3.1. Smart City Index

The Smart City Index (SCI), developed by the Institute for Management Development (IMD) and the Singapore University of Technology and Design, evaluates cities based on their smart infrastructure and technological integration. It assesses smart city development across key areas such as mobility, health and safety, governance, environment, and economic opportunities [37]. The ranking is based on both hard data and residents’ perceptions of how technology improves their quality of life. While the SCI provides a broad assessment of smart city capabilities, it primarily focuses on cities rather than neighborhoods [29]. Moreover, it does not account for region-specific sustainability challenges, making it less applicable as a standalone tool for evaluating smart and sustainable neighborhoods in Saudi Arabia.

2.3.2. ISO 37122: Indicators for Smart Cities

ISO 37122 [14] was developed by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and provides a set of indicators to evaluate the smartness of cities. It focuses on elements like governance, infrastructure, mobility, economic growth, and environmental sustainability. ISO 37122 [14] aims to assist cities in measuring and enhancing their smart city initiatives by offering a clear framework for evaluating urban services and systems [29]. ISO 37122 [14] offers useful insights into the smartness of urban areas, but it lacks a specific framework for neighborhoods and is primarily focused on city-wide infrastructure and policies rather than localized, neighborhood-scale assessments.

2.4. Comparison of Global and Local Rating Systems

The review of existing rating systems presented in Table 1 shows a divide between sustainability- and technology-oriented frameworks. While global rating systems provide valuable insights, none address both dimensions at the neighborhood level, nor do they accommodate Saudi Arabia’s cultural or climatic context. This research seeks to add to the ongoing conversation around smart and sustainable urbanization in Saudi Arabia by presenting a tailored model that addresses the gap between global practices and local needs.

Table 1.

Comparison of global and local rating systems.

2.5. Cultural Context and Adaptation of Rating Systems in Saudi Arabia

The unique cultural, environmental, and socio-economic context of Saudi Arabia plays a significant role in shaping urban development within the country. In Saudi society, traditional values, family structures, and social cohesion are of utmost importance, and urban planning frameworks must reflect these priorities. Saudi Arabia’s rapid urbanization and commitment to Vision 2030 also bring forth new challenges that necessitate the adaptation of global rating systems to better align with local needs.

The current rating systems frequently overlook the unique cultural and environmental conditions present in Saudi Arabia. For instance, family-centric urban spaces, community engagement, and public safety are critical components that should be incorporated into the evaluation of smart and sustainable neighborhoods in Saudi Arabia. The desert climate, which brings extreme heat, limited water resources, and high energy demand, also requires a customized approach to energy efficiency and resource conservation.

Any rating system adopted in Saudi Arabia must also address the nation’s rapid technological advancements, which are central to Vision 2030. The digitalization of public services and the integration of smart technologies into daily life must be incorporated into these frameworks to ensure that smart city initiatives align with the needs and aspirations of Saudi citizens. This includes the integration of IoT, digital connectivity, and real-time data collection into the assessment of neighborhoods, allowing for a more dynamic and adaptable urban planning process.

3. Methodology

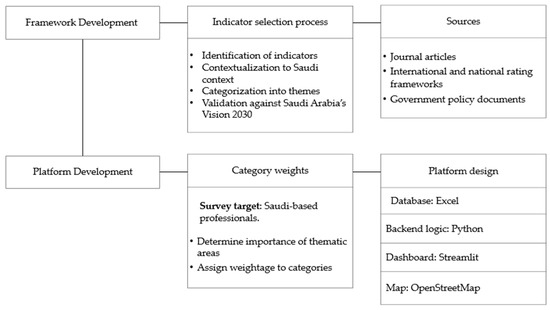

This section outlines the research design and methodology employed in developing a smart and sustainable neighborhood rating system. The section is divided into two main components: (i) the research methodology used to construct and refine the rating framework, and (ii) the platform development methodology to translate the framework into a functional assessment tool. Figure 1 is the graphical illustration of this study’s research approach.

Figure 1.

Research Approach.

3.1. Research Methodology

3.1.1. Research Design

This study follows a qualitative, exploratory approach. Since smart and sustainable urban development is still an emerging field in Saudi Arabia, this method allows for an in-depth exploration of international best practices and how they might be adapted to the Kingdom’s unique environmental, cultural, and regulatory context.

3.1.2. Data Collection

Data for indicator identification and framework development were collected from (i) Journal articles [38,39,40,41], (ii) International rating frameworks (e.g., LEED-ND, BREEAM Communities, ISO 37122 [14]), and (iii) Government policy documents (e.g., Saudi Vision 2030). Triangulation was achieved by analyzing the frequency, relevance, and adaptability of indicators across multiple sources for comparison and validation.

A structured indicator development process was adopted, comprising the following steps:

- Identification: Gathering of indicators from established international frameworks for smart and sustainable neighborhoods.

- Contextualization: Adaptation of indicators based on relevance to the Saudi Arabian context, using local planning policies and climate considerations as filters.

- Categorization: Organization of indicators into dimensions such as mobility, environment, governance, and livability.

- Validation: Indicators were validated against local documents and sustainability targets outlined in Vision 2030.

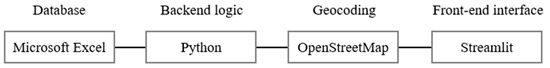

3.2. Platform Development Methodology

3.2.1. Development Strategy

The development of the platform utilized an integrated set of technologies, with each component serving a specific function in the overall system architecture, as shown in Figure 2. At the foundation, Excel was used to store indicator benchmarks and input data. Python served as the core processing engine, handling the scoring logic and data flow. To enable spatial visualization, geocoding was applied to map each neighborhood to its exact location using OpenStreetMap. Streamlit was implemented as the front-end interface to deliver a user-friendly web application.

Figure 2.

Tools used in the platform development.

3.2.2. Scoring System Design

Expert Survey

To ensure that the platform reflects local priorities and contextual relevance, an expert survey process was undertaken. This is to ensure that the selected categories and indicators are conceptually sound and contextually appropriate for application within Saudi Arabia. In addition to validating the framework, the survey aimed to derive the importance and relative weight of each category. This ensured that the scoring reflects the priorities relevant to the local context. Experts were selected based on their knowledge in fields directly related to smart and sustainable urban development. The inclusion criteria required: (i) Professional or academic experience in disciplines such as urban planning, sustainable architecture, smart city technologies, or environmental policy; (ii) familiarity with Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 framework and its implications for urban development. The expert validation was conducted through an individual online survey rather than group consultations, in order to capture independent assessment. A structured questionnaire was distributed to participants, which required them to evaluate: (i) the importance of categories and indicators within the rating system, (ii) potential revisions, removals, or additions to better align the framework with Saudi conditions. In total 35 experts participated in the validation process. The panel was multidisciplinary in nature comprising:

- Urban planners and designers from academic institutions and consultancy firms

- Architects and engineers with expertise in sustainable building practices

- Representatives from government and private sector entities engaged in housing, infrastructure and mobility development.

The participants were recruited through academic affiliations and targeted outreach to governmental agencies. This survey process aimed to strengthen the validity and reliability of the results by engaging a diverse pool of professionals with direct experience in Saudi Arabia’s urban development sector. Although the sample size is modest, the emphasis on the quality and relevance of participants’ expertise ensured that the findings were informed by context-specific knowledge.

Deriving Category Weights

Survey respondents rated different principles on a five-point Likert scale (1 = “Not important,” 5 = “Extremely important”), and the average ratings were used to derive the weights applied to each category in the scoring system.

For each principle, the mean score across all respondents was calculated:

where

= average score for principle i

= rating given by expert j to principle i

= number of respondents (35)

The mean scores of principles were then grouped under their respective categories (e.g., Environmental sustainability → Environment and Urban Resilience). The category mean was computed as the average of its indicators.

The weights were then derived by converting category means into percentages:

where

= weight of category c

= average of principle scores within category c

The final category weights are contained in Table 2. The detailed final indicators data for the two real-life neighborhoods in Saudi Arabia are contained in Table A2.

Table 2.

Final Category Weights.

Scoring Logic

The indicators in the framework were assigned a benchmark score to provide a reference point for evaluating neighborhood performance. Benchmark values were derived from a combination of international and national sources, including global organizations such as the United Nations, World Health Organization, and Saudi Arabian government data/reports on urban development, infrastructure, and social services. The scoring for the indicators is binary:

1 point = benchmark met or exceeded

0 points = benchmark not met

For each category, the indicator scores are averaged to produce a category performance score:

The category score is then multiplied by its category weight from the Table 2

The final score is obtained by summing the weighted scores across all categories

The final score determines the certification level according to the predefined threshold.

4. Results

4.1. Framework

4.1.1. Framework Formulation

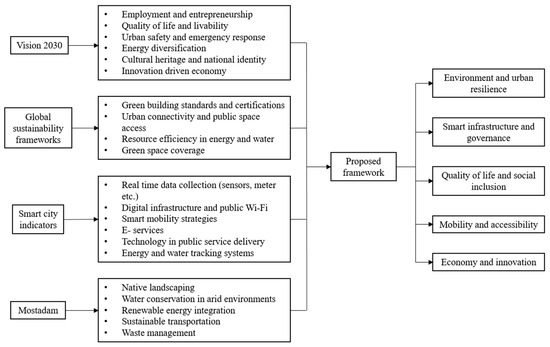

The categories and indicators used in this smart and sustainable neighborhood rating system were derived through a structured synthesis of both global best practices and national strategic priorities. International and local sustainability frameworks provided foundational guidance on environmental performance, green buildings, and community well-being. Smart city dimensions were integrated to emphasize digital infrastructure, real-time monitoring, and technology-enabled services. Importantly, the framework was localized by aligning with Saudi Vision 2030, incorporating themes such as livability, innovation, economic diversification, and digital governance. Figure 3 illustrates the conceptual foundations derived from each framework. The result is a cohesive, category-based structure that reflects both international standards and local development goals, ensuring the framework is globally informed and contextually relevant. It consists of five main categories representing the pillars of a smart and sustainable neighborhood: (i) Environment and Urban Resilience, (ii) Smart Infrastructure and Governance, (iii) Mobility and Accessibility, (iv) Quality of Life and Social Inclusion, and (v) Economy and Innovation.

Figure 3.

Conceptual derivation of smart and sustainable neighborhood indicators from international frameworks and national priorities.

These categories provide a basis for assessing neighborhood performance across physical, technological, social, and institutional dimensions.

4.1.2. Proposed Framework

The final framework includes 54 indicators across the five categories, each accompanied by a measurable criterion. The indicators serve as the backbone of the rating system, enabling an objective assessment of a neighborhood’s smartness and sustainability.

- Environment and Urban Resilience: The preservation of the environment and natural resources is both a moral responsibility and a strategic objective outlined in Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030. The Environment and Urban Resilience category aligns with this national agenda by promoting neighborhood-level practices that support ecological health, environmental quality, and climate adaptability. It highlights the importance of integrating green building principles and passive design strategies to address environmental challenges such as extreme heat, flooding, desertification, and pollution. This category aims to foster neighborhoods that are healthy and capable of withstanding long-term environmental stresses, thereby contributing to the Kingdom’s broader goals of sustainability. The selected indicators for the Environment and Urban Resilience category are outlined in Table 3.

Table 3. Indicators for evaluating the Environment and Urban Resilience category.

Table 3. Indicators for evaluating the Environment and Urban Resilience category. - Smart Infrastructure and Governance: Vision 2030 envisions a digitally advanced and efficiently governed nation, where technology plays a key role in enhancing urban life. The Smart Infrastructure and Governance category supports these goals by encouraging neighborhoods to adopt intelligent systems that improve service delivery, connectivity, and urban management. This includes the integration of digital tools for energy and water efficiency, real-time data monitoring, and responsive infrastructure capable of addressing residents’ needs. This category contributes to the national goal of building smarter, more resilient, and future-oriented communities by fostering digital readiness and innovation at the neighborhood level. The selected indicators for the Smart Infrastructure and Governance category are presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Indicators for evaluating the Smart Infrastructure and Governance category.

Table 4. Indicators for evaluating the Smart Infrastructure and Governance category. - Mobility and Accessibility: This category focuses on creating neighborhoods that are inclusive, well-connected, and easy to navigate. It promotes a shift toward more sustainable and people-centered modes of transportation by encouraging walkability, safe cycling infrastructure, and access to reliable transit options. Reducing dependence on private vehicles helps to minimize traffic congestion and environmental impact, while improving public health and overall quality of life. This category supports the development of urban environments that prioritize accessibility, safety, and efficiency for all residents, regardless of age, ability, or socioeconomic background. The selected indicators for the Mobility and Accessibility category are presented in Table 5.

Table 5. Indicators for evaluating the Mobility and Accessibility category.

Table 5. Indicators for evaluating the Mobility and Accessibility category. - Quality of Life and Social Inclusion: This category emphasizes the creation of inclusive, safe, and engaging neighborhood environments that enhance the well-being of all residents, aligning with the “vibrant society” pillar of Vision 2030. It reflects the Kingdom’s commitment to strengthening social cohesion, promoting cultural heritage, and improving access to essential services such as education, healthcare, and public safety. The category supports the preservation of national identity through the protection of heritage sites and the organization of cultural events that celebrate Saudi traditions. It also encourages community engagement in local decision-making, the integration of digital platforms for civic participation, and universal accessibility for people of all abilities. This category contributes to building connected and resilient neighborhoods that embody the values of compassion, inclusion, and cultural pride envisioned in Vision 2030. The selected indicators for the Quality of Life and Social Inclusion category are outlined in Table 6.

Table 6. Indicators for evaluating the Quality of Life and Social Inclusion category.

Table 6. Indicators for evaluating the Quality of Life and Social Inclusion category. - Economy and Innovation: This category supports Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 objective to build a thriving economy driven by innovation, entrepreneurship, and local opportunity. It emphasizes the importance of fostering economic activity at the neighborhood level by promoting access to employment, encouraging small businesses, and supporting digital and creative industries. The category recognizes the role of local innovation hubs, co-working spaces, and digital infrastructure in attracting talent and enabling knowledge-based growth. It also encourages the integration of emerging technologies and entrepreneurial initiatives that align with national strategies for economic diversification. By embedding innovation into the fabric of neighborhood development, this category contributes to creating dynamic, future-ready communities that support both economic resilience and social advancement. The selected indicators for the Economy and Innovation category are presented in Table 7.

Table 7. Indicators for evaluating the Economy and Innovation category.

Table 7. Indicators for evaluating the Economy and Innovation category.

4.2. Proposed Platform (HayyScore)

Based on the smart and sustainable neighborhood assessment framework formulated in Section 4.1, the HayyScore platform was developed. Hayy, meaning “neighborhood” in Arabic, serves as the inspiration behind the platform’s name. This platform serves as a practical tool to translate the framework into an interactive, user-friendly digital solution. The platform is designed to support urban stakeholders, such as planners, consultants, and developers, in evaluating neighborhood performance across key sustainability and smartness dimensions. HayyScore allows users to input data through structured forms or dropdown selections, which are then processed to assign scores to each indicator based on predefined qualitative and quantitative criteria. These scores are aggregated across categories, generating an overall score that determines the neighborhood’s certification level.

The results are visually displayed through charts, feedback summaries, and certification badges, while a dashboard interface enables users to compare and rank multiple neighborhoods. In this prototype version of HayyScore, 15 representative indicators were selected from the full framework to demonstrate the core scoring and certification logic in a streamlined and time-efficient manner. However, the platform is fully scalable and capable of integrating the complete set of indicators to provide a comprehensive assessment in future iterations.

The 15 indicators were systematically selected from the full set of 54 based on their relevance to the Saudi context, the availability of benchmark data, and the corresponding data from the neighborhood being assessed. This selective approach ensured that the prototype platform could effectively demonstrate its scoring and evaluation process using measurable and contextually valid indicators, while the remaining indicators are retained for inclusion in future iterations as data accessibility improves.

Platform Walkthrough

To demonstrate how the HayyScore platform functions in practice, this section walks through each page, evaluating two neighborhoods in Saudi Arabia—KAPSARC and KFUPM. The walkthrough below highlights how the user interacts with each section of the platform, from starting the assessment to inputting data, viewing dashboard outputs, and exploring rankings.

- Landing Page: The platform opens a landing page with the platform’s name, HayyScore (Figure 4), at the center of the screen and a single button labeled “Start Assessment”.

Figure 4. HayyScore landing page.

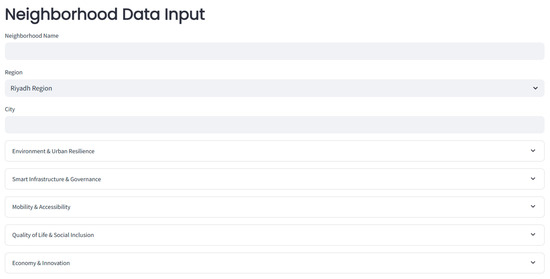

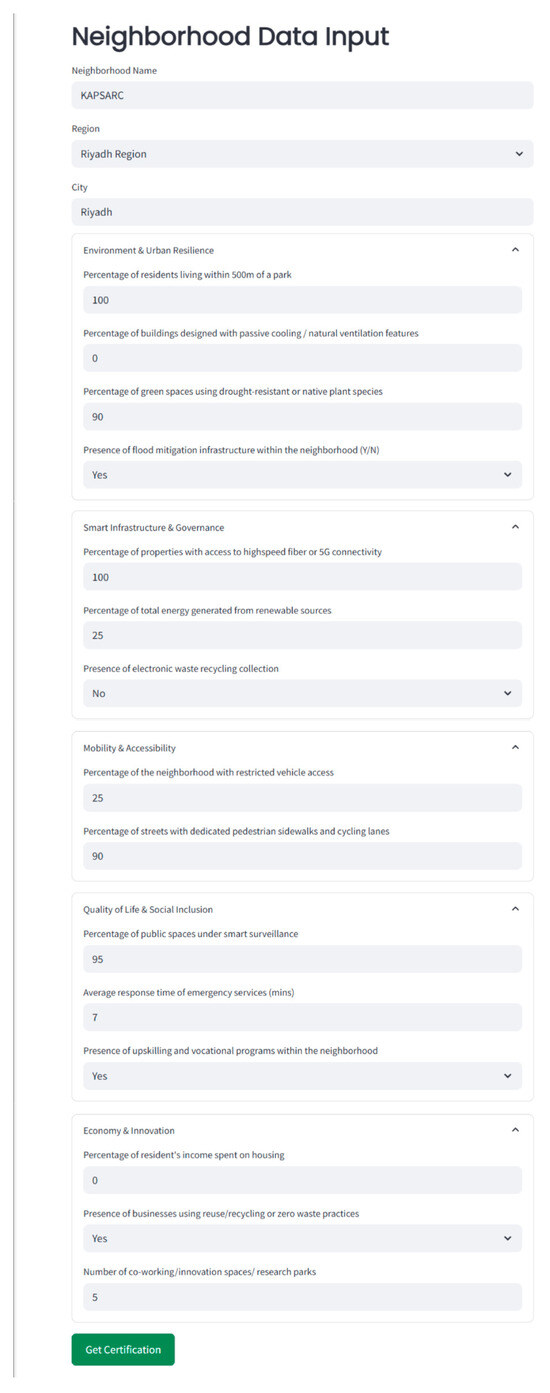

Figure 4. HayyScore landing page. - Submitting Neighborhood Data: After clicking the start assessment button, the user is directed to the input page, where they are asked to provide neighborhood details and indicator data. At the top of the page (Figure 5), the user enters: Neighborhood Name: KAPSARC, Region: Riyadh Province (selected from a dropdown menu), City: Riyadh (typed manually).

Figure 5. Completed input page sample neighbor Neighborhood input page.

Figure 5. Completed input page sample neighbor Neighborhood input page.

Below (Figure 6), the page is divided into five sections, representing the main categories: (i) Environment and Urban Resilience, (ii) Smart infrastructure and Governance, (iii) Mobility and Accessibility, (iv) Quality of life and Social Inclusion, and (v) Economy and Innovation. Each section includes a set of indicators with descriptions and fields to enter either numeric values or yes/no selections. These inputs form the basis for the neighborhood’s performance evaluation.

Figure 6.

Completed input page sample neighborhood data entered.

In this example, the user inputs data reflecting KASPSARC’s current urban development characteristics. Once all required fields for the indicators are completed, the form is submitted to trigger the scoring and visualization process.

- 3.

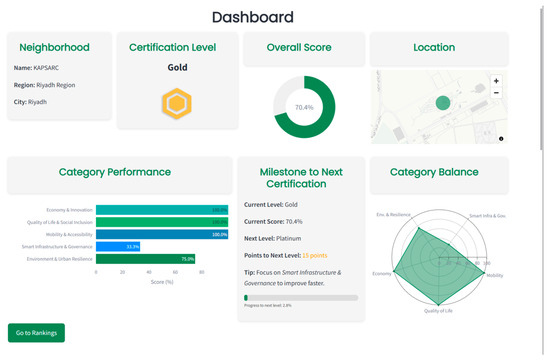

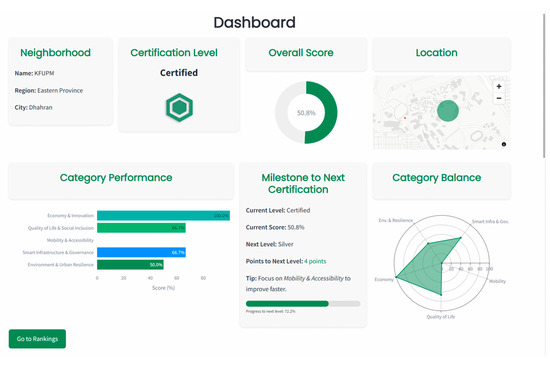

- Dashboard Page: After submission, the user is redirected to the neighborhood’s dashboard. This page provides (see Figure 7 and Figure 8) an immediate and comprehensive visual summary of the neighborhood’s performance: (i) A header displays the neighborhood’s name, region, and city, (ii) A donut chart highlights the total score (83.3/100) and certification level (Gold), (iii) A bar chart shows individual category scores, helping identify strengths and areas for improvement, (iv) An interactive map, using OpenStreetMap, visualizes the location based on user inputs.

Figure 7. Dashboard displaying overall neighborhood KAPSARC performance.

Figure 7. Dashboard displaying overall neighborhood KAPSARC performance. Figure 8. Dashboard displaying overall neighborhood KFUPM performance.

Figure 8. Dashboard displaying overall neighborhood KFUPM performance. - 4.

- Scoring System: The smart and sustainable neighborhood rating system in this prototype employs a weighted, points-based method to evaluate neighborhood performance across the five categories, using a simplified set of 15 representative indicators. These indicators were selected from the full 54-indicator framework to demonstrate the platform’s scoring and certification logic in a manageable and time-efficient manner.

Each of the 15 indicators contributes 1 point if fulfilled, resulting in a maximum raw score of 15 points. To ensure that the evaluation reflects both expert judgment and local development priorities, the platform applies category weights derived from a stakeholder survey. Experts rated the relative importance of each category, and their responses were converted into proportional weights to give more influence to categories deemed most critical, as shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Category weight distribution.

When users input data for each indicator, the platform evaluates each value against predefined benchmarks, drawn from a mix of international and local standards. Each indicator is then scored from 0 to 100, reflecting its performance.

The scoring process follows three key steps:

- Normalize indicator scores based on benchmark alignment (0–100 scale)

- Calculate the average score per category

- Apply category weights to compute the final score: weighted score = ∑ (category score × category weight)

The result is a total score out of 100, which forms the basis for certification and ranking. In KAPSARC’s case, the platform calculated a total score of 70.4, which is a weighted average of all category-level scores.

- 5.

- Certification Levels: The platform translates the total weighted score into a certification level using a five-tiered system. Each tier reflects a range of performance aligned with the overall objectives of smart and sustainable development, as shown in Table 9.

Table 9. Certification Levels.

Table 9. Certification Levels.

To promote continuous progress, the platform also calculates the additional points needed for a neighborhood to reach the next tier, encouraging stakeholders to set performance improvement goals. KAPSARC’s score of 70.4% places it in the gold tier, indicating it meets many of the standards but still has notable room for improvement, particularly in infrastructure and governance, which could be enough to achieve platinum certification.

- 6.

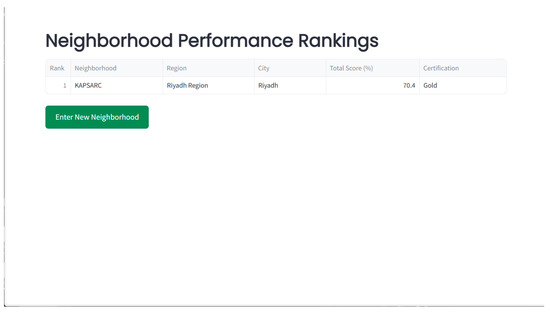

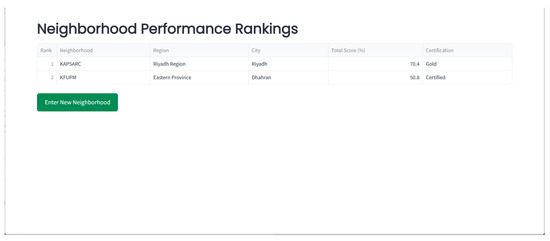

- Ranking Page: Finally, the user visits the rankings page (Figure 9), where the evaluated neighborhood is listed in a sortable table. Each entry includes the neighborhood name, region and city, score, and certification level.

Figure 9. Ranking page.

Figure 9. Ranking page.

The user can stop here or enter a new neighborhood. This feature allows multiple neighborhoods to be entered and compared based on the ranking (see Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Ranking page showing multiple neighborhoods.

5. Discussion

This section interprets the findings presented in Section 4 in light of the comprehensive literature review. It evaluates the strengths of the proposed framework and HayyScore platform, critically reflects on its alignment with global and local practices, and explores the practical potential for implementation in Saudi Arabia.

5.1. Localizing Global Framework

Developing the smart and sustainable neighborhood framework is an important step toward aligning global best practices with the unique priorities of Saudi Arabia. As highlighted in the literature [15,29], adaptation to local spatial, cultural, and governance contexts is essential for the success of smart city and neighborhood initiatives.

The five-category structure of the framework reflects a well-rounded view of what contributes to smart and sustainable neighborhoods, in line with approaches discussed in the literature [25,27]. Instead of concentrating on a single aspect, it thoughtfully combines environmental, social, technological, and economic factors into an integrated model. This helps overcome the limitations seen in systems like QSAS and MOSTADAM, which often overlook the importance of smart technologies in urban development [21,33].

By embedding indicators that respond specifically to Saudi Arabia’s climatic challenges, cultural traditions, and rapid digital transformation ambitions under Vision 2030, HayyScore delivers a framework that is not only globally informed but contextually relevant. It aligns with calls for neighborhood-scale assessments that consider institutional and governance pillars alongside environmental and social factors [17,27].

5.2. Advantage over Existing Tools

A significant contribution of HayyScore is its integration of smart technology indicators that are often missing in traditional sustainability rating systems [13,24]. The framework moves beyond the smart-versus-sustainable debate by offering a synthesis that captures the dynamic interplay between technology and sustainability at the neighborhood level. Furthermore, HayyScore includes socio-cultural dimensions, recognizing that the success of smart neighborhoods depends on resident participation, cultural preservation, and social cohesion, which are often overlooked in international tools [26,42]. This focus resonates with Vision 2030’s Vibrant Society pillar, emphasizing family values, heritage, and community engagement. The framework’s attention to climate-specific challenges, such as heat mitigation, water scarcity, and desert-adapted landscaping, also addresses environmental realities unique to Saudi Arabia, which many global systems fail to incorporate [21].

Unlike existing tools such as LEED-ND or BREEM communities, which primarily emphasize environmental performance, HayyScore integrates smart infrastructure, governance, and cultural adaptability within a unified evaluation model. It also bridges the gap between international best practices and local policy frameworks, enabling a more contextually grounded and operationally relevant assessment for Saudi neighborhoods.

5.3. Implementation in Saudi Arabia

The implementation of HayyScore has significant implications for urban policy and real estate field in Saudi Arabia. It offers a practical tool that urban consultants and developers can use to guide design decisions and monitor progress. Its alignment with Vision 2030 reinforces its relevance, particularly in relation to national goals for smart governance, sustainable development, and regional equity.

In this prototype version of HayyScore, 15 representative indicators were selected from the full framework to demonstrate the core scoring and certification logic in a streamlined and time-efficient manner. However, the platform is fully scalable and capable of integrating the complete set of 54 indicators to provide a comprehensive assessment in future iterations. This scalability ensures that HayyScore can evolve alongside emerging data availability and stakeholder needs. In addition to that, by integrating culturally relevant indicators such as heritage site preservation and community event participation, the platform supports the social fabric of Saudi neighborhoods. This addresses critiques that many global smart frameworks neglect local values, traditions, and informal dynamics [26,42].

While the research presents a practical contribution to urban evaluation in the Saudi context, certain limitations must be acknowledged. The framework was developed using secondary sources, expert surveys, and testing the platform across multiple neighborhoods. These steps provided an initial level of empirical validation, ensuring that the indicators and scoring logic are grounded in both theory and practice. However, broader empirical testing remains necessary to further validate and refine the framework’s applicability across diverse urban contexts in Saudi Arabia.

Additionally, the platform currently relies on user-submitted data, which introduces risks related to accuracy, consistency, and potential bias. Without a built-in verification mechanism, the results may be skewed. Future research should focus on expanding the application of HayyScore by integrating real-time data collection methods, such as IoT sensors and GIS platforms, to improve the accuracy and timeliness of assessments while reducing reliance on manual input. Additionally, the platform’s policy relevance would be strengthened by developing third-party verification processes, establishing minimum baseline criteria for certification, and integrating the framework within municipal planning systems. The following roadmap outlines key areas of advancement:

- Expansion of indicators:

- Gradually integrate the remaining indicators to move from the current 15 toward the full set of 54.

- Improved data collection:

- Reduce reliance on manual user inputs by integrating IoT sensors, GIS platforms, and open data sources.

- Develop mechanisms for real-time monitoring of environmental, mobility, and infrastructure metrics.

- Verification and certification:

- Implement third-party verification to strengthen credibility

- Define minimum baseline thresholds for certification to ensure that neighborhoods meet fundamental sustainability and smartness criteria before being ranked.

- Explore institutional partnerships to align HayyScore with municipal planning systems.

- Platform design

- Provide tailored feedback and recommendations for each neighborhood

6. Conclusions

This study set out to address a growing gap in the evaluation of smart and sustainable urban development at the neighborhood level within Saudi Arabia. Global sustainability frameworks and smart city assessment tools offer useful foundations for evaluating environmental and technological performance. However, they often fail to address the spatial, climatic, and cultural realities of specific national contexts. In Saudi Arabia, the combination of rapid urban expansion, extreme environmental conditions, and an ambitious national digital transformation agenda necessitates the creation of a localized and adaptable framework that measures sustainability and also captures the evolving smartness of neighborhoods.

To respond to this need, the research developed an evaluation framework designed specifically to assess the smart and sustainable performance of Saudi neighborhoods. The framework consists of five categories: (i) Environment and Urban Resilience, (ii) Smart Infrastructure and Governance, (iii) Mobility and Accessibility, (iv) Quality of Life and Social Inclusion, and (v) Economy and Innovation. Within these categories, the indicators were selected to evaluate a range of physical, technological, social, and institutional factors that together define the performance of a smart and sustainable neighborhood. The framework was operationalized through the development of the HayyScore platform, which features automated dashboards, ranking systems, and category-level breakdowns to facilitate comparative analysis and decision making.

In conclusion, this study offers a step towards operationalizing smart and sustainable neighborhood assessment in Saudi Arabia. By combining global frameworks with local priorities and providing a scalable digital platform, it lays the groundwork for more informed, inclusive, and future-ready urban development in the Kingdom.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.D. and H.M.A.; methodology, S.D.; software, S.D.; validation, S.D., H.M.A. and Y.A.A.; formal analysis, S.D.; investigation, S.D., H.M.A. and Y.A.A.; resources, S.D., H.M.A. and Y.A.A.; data curation, S.D.; writing—original draft preparation, S.D.; writing—review and editing, S.D., H.M.A. and Y.A.A.; visualization, S.D.; supervision, H.M.A. and Y.A.A.; project administration, H.M.A. and Y.A.A.; funding acquisition, Y.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by the King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was exempted by the Academic Research Ethics Committee, School of Education, City University of Macau.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection.

Data Availability Statement

Additional data will be made available based on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledged the support of the King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals, Dhahran, Saudi Arabia for providing state of the art facilities and an enabling environment for this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| KPIs | key performance indicators |

| USGBC | U.S. Green Building Council |

| BREEAM | Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Methodology |

| QSAS | Qatar Sustainability Assessment System |

| ICT | information and communication technologies |

| SCI | Smart City Index |

| IMD | Institute for Management Development |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| UAE | United Arab Emirates |

Appendix A. Research Survey: Smart and Sustainable Neighborhoods

Smart and sustainable neighborhoods are neighborhoods that combine environmentally responsible design with smart technologies to create livable, efficient, and future-ready communities that support well-being, mobility, and resilience.

In this short survey, you will help evaluate the importance of key categories and indicators that contribute to a smart and sustainable neighborhood. Please be assured that your responses will remain completely anonymous and will be used solely for academic research purposes.

Thank you for your valuable contribution.

- What is your main field of expertise?

(Select all that apply)

- Urban planning

- Sustainability

- Smart city development

- Architecture

- Environmental engineering

- Academia/Research

- Other

- 2.

- In which region or city are you currently based?

(Select the one that applies most)

- Riyadh Region

- Makkah Region

- Eastern Province

- Madinah Region

- Asir Region

- Qassim Region

- Tabuk Region

- Northern Borders Region

- Hail Region

- Jazan Region

- Najran Region

- Al-Jouf Region

- Al-Baha Region

- 3.

- Based on your expertise, please rate the importance of each principle in achieving successful smart and sustainable neighborhoods:

(Rate each from 1 = Not Important to 5 = Extremely Important)

| Principle | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Environmental sustainability (resource efficiency, protecting the natural environment, water and waste management) | |||||

| Smart mobility and transport systems (public transport, electric vehicles, traffic management) | |||||

| Good governance and digital services (online services, transparency, participatory governance) | |||||

| Quality of living and community well-being (health, safety, inclusivity, education) | |||||

| Economic opportunities (job creation, local entrepreneurship) | |||||

| Innovative projects | |||||

| Technology integration (smart infrastructure, real-time sensors) |

- 4.

- In your opinion, what are the top challenges that Saudi cities and neighborhoods currently face in becoming smart and sustainable?

(Please describe any social, environmental, technological, or policy-related challenges you consider significant)

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

- 5.

- Thinking ahead, please rate the following strategies in order of priority for developing new neighborhoods:

(Rate each from 1 = Not Important to 5 = Extremely Important)

| Strategy | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Green and resilient infrastructure (energy systems, cooling, shading) | |||||

| Advanced mobility (public transport, electric vehicles, AI traffic systems) | |||||

| Smart buildings and homes (energy-efficient, digitally connected) | |||||

| Sustainable water management (leak detection, recycling systems) | |||||

| Community engagement and inclusion platforms | |||||

| Digital governance and open data systems | |||||

| Local entrepreneurship and digital economy hubs | |||||

| Health, education, and social services proximity | |||||

| Cultural heritage preservation and integration | |||||

| Innovation hubs (startup accelerators, tech centers) |

- 6.

- Any comments, recommendations, or additional indicators you suggest for designing future smart and sustainable neighborhoods?(Open-ended)

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

Thank you for supporting this research effort!

Appendix B. Research Survey Results

A total of 35 responses were collected. Each respondent rated 18 indicators across thematic areas. These indicators were grouped into five main categories for analysis:

Table A1.

Categories and their associated indicators.

Table A1.

Categories and their associated indicators.

| Category | Associated Indicators |

|---|---|

| Environment and Urban Resilience |

|

| Smart Infrastructure and Governance |

|

| Mobility and Accessibility |

|

| Quality of Life and Social Inclusion |

|

| Economy and Innovation |

|

To derive the final category weights:

- Individual responses for each indicator were averaged across all 35 experts.

- For each category, the mean of its corresponding indicators was computed.

- These category means were then normalized so that the sum of all category weights equaled 100%.

- The resulting percentage weights were then rounded to make them easier to apply in practice.

Table A2.

Data for KAPSARC and KFUPM.

Table A2.

Data for KAPSARC and KFUPM.

| Indicator | KAPSARC | KFUPM |

|---|---|---|

| Residents living within 500 m of a park or green space (%) | 100% | 100% |

| Buildings designed with passive cooling or natural ventilation features (%) | 0% | 20% |

| Green spaces using drought-resistant or native plant species (%) | 90% | 30% |

| Presence of infrastructure designed for flood risk reduction (Y/N) | Yes | Yes |

| Properties in the neighborhood with access to high-speed fiber or 5G connectivity (%) | 100% | 100% |

| Total energy generated from renewable sources (%) | 25% | 15% |

| Presence of electronic waste recycling points or drop-off boxes (Y/N) | No | Yes |

| Area with restricted vehicle access (%) | 25% | 15% |

| Streets with pedestrian sidewalks and cycling lanes (%) | 90% | 50% |

| Public spaces under smart surveillance (%) | 95% | 90% |

| Average response time of emergency services (minutes) | 7 | 8 |

| Availability of upskilling or vocational programs within the neighborhood (Y/N) | Yes | Yes |

| Percentage of residents’ income spent on housing | 0% (employer provided housing) | 0% (employer provided housing) |

| Presence businesses using reuse/recycling or zero waste practices (Y/N) | Yes | Yes |

| Number of co-working/innovation spaces/research parks | 5 | 5 |

References

- Hafiz, A.A.; Usman, F.; Hidayat, A.R.R.T.; Zakiyah, D.M. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Urban Sprawl Types in the Peri-Urban Area of Malang Municipality, Indonesia. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibri, S.E.; Krogstie, J. Smart sustainable cities of the future: An extensive interdisciplinary literature review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 31, 183–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colldahl, C.; Frey, S.; Kelemen, J. Smart Cities: Strategic Sustainable Development for an Urban World. Master’s Thesis, Blekinge Institute of Technology, Karlskrona, Sweden, 2013. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:832150/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Alshemerty, M.A.; Albasri, N.A.H. Smart neighborhood as a sustainable neighborhood: A comparative study of Al-Ghadeer village (Najaf-Iraq). IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1129, 012019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsabt, R.; Adenle, Y.A.; Alshuwaikhat, H.M. Exploring the Roles, Future Impacts, and Strategic Integration of Artificial Intelligence in the Optimization of Smart City—From Systematic Literature Review to Conceptual Model. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugisha, J.; Uwayezu, E.; Babere, N.J.; Kombe, W.J. Fostering Neighbourhood Social–Ecological Resilience Through Land Readjustment in Rapidly Urbanising Cities in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Case of Nunga in Kigali, Rwanda. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottini, L. The future of smart cities and the role of neighborhoods in influencing sustainable behaviors: A general overview. Fuori Luogo 2023, 17, 89–98. Available online: https://boa.unimib.it/retrieve/861ffdfc-0698-4ad6-a96c-60159efb2b57/Bottini-2023-Fuori%20luogo-VoR.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Saudi Vision 2030. 2016. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/media/rc0b5oy1/saudi_vision203.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- HAlshuwaikhat, M.; Adenle, Y.A.; Almuhaidib, T. A Lifecycle-Based Smart Sustainable City Strategic Framework for Realizing Smart and Sustainability Initiatives in Riyadh City. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfehaid, F.; Omri, A.; Altwaijri, A. Impact of ICT diffusion and opportunity entrepreneurship on environmental sustainability in Saudi Arabia. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darabi, N.; Masoud, M.; Abtahi, S.M. Measuring the sustainability of neighborhood by applying LEED-ND model In order to reduce energy consumption. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2022, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- de Siqueira, A.C.H.; Najjar, M.K.; Hammad, A.W.A.; Haddad, A.; Vazquez, E. Sustainable Urban Development in Slum Areas in the City of Rio de Janeiro Based on LEED-ND Indicators. Buildings 2020, 10, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantry, W.; Turcu, C. Sustainability power to the people: BREEAM Communities certification and public participation in England. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 37122; Sustainable Cities and Communities—Indicators for Smart Cities. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Sharifi, A.; Dawodu, A.; Cheshmehzangi, A. Neighborhood sustainability assessment tools: A review of success factors. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 125912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, F.; Guimarães, C.M.; Amorim, V. Exploring the Differences and Similarities between Smart Cities and Sustainable Cities through an Integrative Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanguy, A.; Breton, C.; Blanchet, P.; Amor, B. Characterising the development trends driving sustainable neighborhoods. Build. Cities 2020, 1, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Surveyer, A.; Elmqvist, T.; Gatzweiler, F.W.; Güneralp, B.; Parnell, S.; Prieur-Richard, A.-H.; Shrivastava, P.; Siri, J.G.; Stafford-Smith, M.; et al. Defining and advancing a systems approach for sustainable cities. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2016, 23, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R.B. Beyond the pillars: Sustainability assessment as a framework for effective integration of social, economic and ecological considerations in significant decision-making. J. Environ. Assess. Policy Manag. 2006, 08, 259–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A. From Garden City to Eco-urbanism: The quest for sustainable neighborhood development. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2016, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferwati, M.S.; Al Saeed, M.; Shafaghat, A.; Keyvanfar, A. Qatar Sustainability Assessment System (QSAS)-Neighborhood Development (ND) Assessment Model: Coupling green urban planning and green building design. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 22, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, M.; Joss, S.; Schraven, D.; Zhan, C.; Weijnen, M. Sustainable-smart-resilient–low carbon-eco-knowledge cities; Making sense of a multitude of concepts promoting sustainable urbanization. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 109, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yung, E.; Chan, E. Towards Sustainable Neighborhoods: Challenges and Opportunities for Neighborhood Planning in Transitional Urban China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardi, U. Sustainability Assessment in the Construction Sector: Rating Systems and Rated Buildings. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 20, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubizarreta, I.; Seravalli, A.; Arrizabalaga, S. Smart City Concept: What It Is and What It Should Be. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2016, 142, 04015005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. Making older urban neighborhoods smart: Digital placemaking of everyday life. Cities 2024, 147, 104814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoghi, M.; Ferrari, S.; Paganin, G.; Dall’O’, G. A novel framework to measure and promote smartness in neighborhoods. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 101, 105206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloni, A.; Fornara, F.; Carrus, G. Predicting pro-environmental behaviors in the urban context: The direct or moderated effect of urban stress, city identity, and worldviews. Cities 2019, 88, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidou, M. Smart city policies: A spatial approach. Cities 2014, 41, S3–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komeily, A.; Srinivasan, R.S. A need for balanced approach to neighborhood sustainability assessments: A critical review and analysis. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2015, 18, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A.; Murayama, A. A critical review of seven selected neighborhood sustainability assessment tools. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2013, 38, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BREEAM. About BREEAM, (n.d.). Available online: https://breeam.com/ (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Al-Surf, M.; Balabel, A.; Alwetaishi, M.; Abdelhafiz, A.; Issa, U.; Sharaky, I.; Shamseldin, A.; Al-Harthi, M. Stakeholder’s Perspective on Green Building Rating Systems in Saudi Arabia: The Case of LEED, Mostadam, and the SDGs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balabel, A.; Alwetaishi, M. Towards Sustainable Residential Buildings in Saudi Arabia According to the Conceptual Framework of “Mostadam” Rating System and Vision 2030. Sustainability 2021, 13, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Abu Dhabi. The Pearl Rating System for Estidama Building Rating System. Abu Dhabi. 2010. Available online: https://jawdah.qcc.abudhabi.ae/en/Registration/QCCServices/Services/STD/ISGL/ISGL-LIST/DP-306.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Batty, M.; Axhausen, K.W.; Giannotti, F.; Pozdnoukhov, A.; Bazzani, A.; Wachowicz, M.; Ouzounis, G.; Portugali, Y. Smart cities of the future. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2012, 214, 481–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giffinger, R.; Fertner, C.; Kramar, H.; Kalasek, R.; Pichler-Milanović, N. Smart Cities—Ranking of European Medium-Sized Cities. 2007. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/261367640_Smart_cities_-_Ranking_of_European_medium-sized_cities (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Al Qurashi, R.; Almnjomi, M.; Alghamdi, T.; Almalki, A.; Alharthi, S.; Althobut, S.; Alharthi, A.; Thafar, M. Smart Waste Management System for Makkah City Using Artificial Intelligence and Internet of Things. 2025. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2505.19040 (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Shawly, H. Evaluating Compact City Model Implementation as a Sustainable Urban Development Tool to Control Urban Sprawl in the City of Jeddah. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addas, A. Exploring the pattern of use and accessibility of urban green spaces: Evidence from a coastal desert megacity in Saudi Arabia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 55757–55774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, I.; Helmi, M.; Qurnfulah, E.; Maddah, R.; Ibrahim, H.S. Global trends in sustainability rating assessment systems and their role in achieving sustainable urban communities in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2021, 16, 882–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaharevic, A.; Wihlborg, E. Whose Future is Smart?: A Systematic Literature Review of Smart Cities and Disadvantaged Neighborhoods. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, Pretoria, South Africa, 1–4 October 2024; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).