Abstract

The 15-minute city (15MC) model has gained increasing attention as a framework for promoting sustainable urban living by ensuring that essential services, including urban green spaces (UGSs), are accessible within short walking or cycling distances. UGSs play a vital role in public health, social interaction, and environmental resilience, yet questions remain about how equitably they are distributed and accessed in cities. This study assesses proximity and accessibility to UGSs in Porto, Portugal, through the lens of the 15MC. The methodology combined a GIS-based spatial analysis of walking and cycling catchments with a complementary questionnaire to capture user perceptions and travel behaviors. Results show that, while 84% and 100% of residents live within a 15-minute walking and cycling distance of a UGS, respectively, accessibility remains uneven, particularly for walking. Large peripheral parks contribute significantly to provision but remain less accessible to central neighborhoods, and cycling to UGSs is marginal due to fragmented and insufficient infrastructure, and residual cycling use. Subjective findings mirrored the spatial analysis, highlighting dissatisfaction with cycling conditions and only moderate satisfaction with pedestrian environments. The study emphasizes the need for integrated planning that improves local connectivity, infrastructure quality, and spatial equity to fully realize the 15MC vision.

1. Introduction

This Introduction provides an overview of the 15-minute city (15MC) concept, highlighting the role of urban green spaces (UGSs), their benefits, and key issues related to size and accessibility. It also identifies current research gaps and concludes with the aims and objectives of the present study.

1.1. The 15-Minute City Concept

The 15MC has emerged as a transformative model for sustainable and equitable urban development, emphasizing accessibility to essential services within a short timeframe through active transportation modes such as walking and cycling [1,2]. Proposed by Carlos Moreno in 2016 [3], the concept builds upon earlier planning paradigms, namely, (i) Clarence Perry’s neighborhood unit (1929), which defined compact residential neighborhoods where the proximity between services and homes fostered a sense of community belonging [4], and (ii) Ebenezer Howard’s garden city model (1898), which aimed to create livable, mixed-use communities that merged the urbanism of the city with the greenery of the countryside [5,6]. The 15MC relies on principles of urban proximity, densification, diversification, and digitalization, achieved through the spatial redistribution of six key urban functions: living, working, commerce, healthcare, education, and entertainment [3,7]. In recent years, this concept has garnered significant attention as a model for sustainable and equitable urban development, addressing two major global challenges: climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic [1,2].

Walking and cycling are the primary travel modes that define the 15MC [8]. Both are free of carbon emissions, do not produce air pollutants or noise, and require minimal consumption of non-renewable resources, with limited spatial and infrastructural impact. In addition, they are active modes of transportation that offer significant health benefits by mitigating the effects of sedentary lifestyles [9,10]. The popularity of the 15MC increased substantially during the COVID-19 pandemic, which dramatically altered travel habits [11]. Fear of contagion, lockdowns, and mobility restrictions led to a marked shift toward private and active modes of transport, while demand for public transportation declined sharply [12]. In response, governments worldwide implemented measures to support active travel, such as pedestrianizing streets and expanding cycle lanes [13], thereby accelerating interest in the 15MC as urban planners sought to create self-sufficient neighborhoods where residents could meet their daily needs locally through active travel [1,14]. Cities including Barcelona, Paris, Utrecht, Montreal, Shanghai, and Melbourne, among many others, have actively pursued implementation of the 15MC model [1,2].

1.2. Urban Green Spaces in the 15-Minute City: Benefits and Key Issues

Urban green spaces (UGSs) are considered essential amenities within the 15MC concept [15]. Their provision is part of two key urban functions (living and entertainment) and represents an ecological dimension of the 15MC that enhances urban sustainability and quality of life [3,14,16]. UGSs offer a wide range of environmental, social, and economic benefits, making them vital for the development of sustainable cities [17]. Environmentally, they help regulate urban climate by mitigating the heat island effect through shade and evapotranspiration, thereby moderating temperatures and contributing to energy savings [18]. They also play a crucial role in carbon sequestration, air purification, and noise reduction, while supporting biodiversity and ecosystem services such as flood and erosion control [17,19]. Socially, UGSs foster interactions and strengthen community ties by providing recreational and aesthetic value [12,16]. They also promote physical and mental well-being by encouraging exercise and reducing stress, benefits that, alongside improved environmental quality, support healthier lifestyles and overall public health [20,21]. For instance, a recent study on the role of UGS during the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated their importance in promoting mental and physical well-being, reducing stress, and enhancing urban resilience [22]. Economically, proximity to UGS can increase property values, attract investments and businesses, promote local tourism, and generate indirect savings in healthcare and energy costs [23,24]. These benefits underscore the need for equitable access to UGS, in line with the 15MC principle of ensuring active travel access to essential services, including green areas, within a short distance of residences. Ensuring such equitable and convenient access is therefore crucial for reducing social disparities and strengthening cities’ preparedness for future public health crises [22].

UGSs are a component of green infrastructure that encompasses various types of spaces differing in size, structure, and use, including both formal and informal areas such as street greenery, private and public gardens, urban parks, sports grounds, cemeteries, burial sites, urban forests, road verges, and horticultural areas, among others [17,25,26]. This study focuses on public UGSs, as they are free of charge, accessible to all citizens, and used for a wide range of purposes. Public UGSs are defined as openly accessible areas that may include individual trees, small designed sites, or larger nature-like settings connected to built-up areas [27]. They are typically classified by size into small green spaces, including pocket parks with less than 2 hectares (ha); medium-sized green spaces (2–10 ha); and large green spaces (>10 ha), which may be further categorized into district parks (up to 20 ha) and regional parks (>60 ha) [24,28]. While there is no universal consensus in the literature regarding the optimal size of UGS [29], the generally accepted Western standard suggests that city residents should have access to UGS of at least 2 ha located within the buffered urban built-up area [30,31]. Larger UGSs (>2 ha) are particularly important due to their enhanced environmental, social, and health benefits, and are often regarded as the smallest size that people are regularly willing to visit [32,33]. There is also evidence of a positive association between UGS size and levels of physical activity [34,35,36]. For example, Schipperijn et al. [34] reported that green spaces between 5 and 10 ha significantly increase the likelihood of being physically active compared to smaller UGSs (<1 ha). Environmentally, studies have shown that UGSs under 2 ha generally lack cooling effects and may even be warmer than surrounding areas [37].

Distance to UGS is another critical parameter influencing their accessibility [38]. Research has consistently shown that shorter distances to UGS are associated with greater levels of physical activity and higher visitation frequency [30,39]. These findings align with international recommendations from the World Health Organization (WHO) [40] and the European Environment Agency, which suggest that residents should have access to UGS within a 15-minute walk, approximately 900–1000 m [41]. Such guidelines are consistent with the principles of the 15MC, which emphasize ensuring that UGSs are accessible within a short walk or cycle for all citizens, thereby promoting spatial equity, health and well-being [11]. For example, Cardinali et al. [39] found that green spaces and green corridors within 800–1000 m were significantly associated with higher physical activity and indirect health benefits, while Ståhle [42] also proposed 1000 m as a reasonable walking distance threshold. Proximity strongly influences visitation rates too. For instance, Grahn and Stigsdotter [38] observed that UGSs within 300 m were visited an average of 2.7 times per week, whereas those at 1000 m were visited only once weekly. Nonetheless, a recent study in three European cities reported that people often travel beyond these recommended distances, with median travel distances ranging from 1.4 to 1.9 km [34]. Several guidelines consider both size and accessibility: the WHO recommends that small UGS (0.5–1 ha) be located within 300 m of all residences, equivalent to about a 5-minute walk [43]; in Berlin, planning guidelines specify 500 m (5–10 min on foot) to UGS of at least 0.5 ha, and 1–1.5 km to larger UGS [44]. It should be noted, however, that optimal distances can vary depending on multiple UGS characteristics, including size and available facilities. Moreover, the notion of accessibility extends beyond distance and formal access rights, encompassing social and perceptual dimensions. Related studies have shown that UGSs are not equally accessible to all, with lower levels of engagement often observed among vulnerable groups such as older adults, ethnic minorities, immigrants, and populations with lower educational or income levels [16,45].

1.3. Research Gaps

Despite the growing interest in the 15MC as a planning model, several research gaps persist. First, the number of 15MC initiatives is continuously increasing, which makes existing overview studies quickly outdated. Consequently, there remains a significant lack of clarity about the complex global landscape of how the 15MC is defined and implemented in practice, including its strategies, tools, policy applications, and the emerging research and innovation challenges associated with its development [46]. This gap is particularly evident in Portugal, where scientific research on the 15MC remains scarce and fragmented, largely due to a delayed adoption of the concept, driven by the absence of national strategic guidelines [7]. Furthermore, it is recognized that policymakers, urban planners, and communities must focus on concrete actions to effectively implement the 15MC model [47]. This is especially relevant for promoting urban green equity and sustainable urban development, given the persistent inequities in access to green spaces within the 15MC framework [1,48]. Moreover, applying the 15MC as a planning tool requires considering the quality of active mobility infrastructure, often overlooked in proximity analyses, as well as local preferences, since people have diverse priorities and needs. Individuals do not perceive the built environment identically, but the role of these preferences and perceptions in the context of the 15MC has yet to be fully disentangled [49]. Finally, in the case of Porto, the applicability of the 15MC model remains largely underexplored [50].

1.4. Aims and Objectives of the Study

To address the mentioned research gaps, this study assesses the availability and accessibility of UGS in Porto, Portugal, for both walking and cycling, through the lens of the 15MC model. Methodologically, it adopts a mixed approach that integrates objective and subjective components. The objective component consists of a Geographic Information Systems (GIS) analysis using the road network to delineate service areas around each UGS within a 15-minute travel time. The Gini coefficient was used to assess the spatial equity of pedestrian and cycling access to UGS. The subjective component involves a questionnaire administered to capture citizens’ perceptions regarding green space availability and the quality of walking and cycling routes for accessing these spaces. This component serves a complementary role, providing qualitative insights that enrich the GIS-based analysis. By combining both components, the study not only addresses key gaps in the literature but also offers a practical tool to guide the implementation of the 15MC concept in Porto, identifying priority areas for improving UGS access through active travel.

2. Materials and Methods

This study adopts a mixed-methods approach to assess the availability of UGSs larger than 2 ha in the city of Porto, as well as their proximity, and accessibility by walking and cycling, in line with the 15MC concept. This section describes the methodological steps undertaken in both the objective and subjective components to achieve these aims.

2.1. The Case of Porto

With 231,800 residents [51], Porto is the largest city in Northern Portugal. Its historic core, classified as a UNESCO World Heritage site, features narrow, winding streets and dense urban fabric. Porto has a temperate Csb climate, with an average annual temperature of 15.3 °C and total annual precipitation of approximately 1147 mm [52]. Summers are mild and dry, while winters are mild and wet, which may influence outdoor activities, including the frequency of walking and cycling to UGS. Topographically, the city is generally low-sloped, particularly in the north and west, where most slopes are below 3% [53]), making these areas very suitable for walking [54] and cycling [10]. Some areas have slopes between 3% and 6%, which are less favorable but still acceptable for walking and cycling [10,54]. Steeper areas are mainly located along the margins of the Douro River and the Tinto and Torto rivers in the eastern part of the city (Campanhã), as well as in parts of the historic center, corresponding to low-density residential areas.

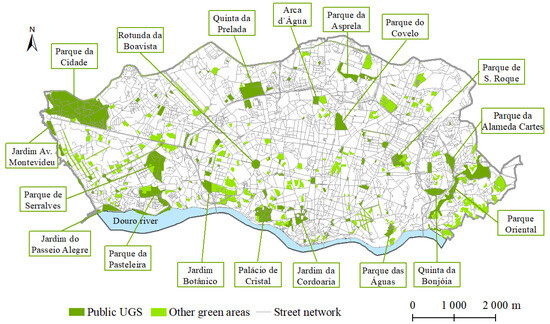

Studies on green spaces have documented a significant reduction of approximately 60% in the city’s green areas over the last century, which have also become increasingly fragmented as a result of urbanization [55,56]. According to the Municipal Master Plan, and as shown in Figure 1, the city’s existing ecological system comprises (i) publicly accessible UGS, including major parks such as Parque da Cidade (the largest in the country), riverside promenades, and smaller pocket parks dispersed across neighborhoods. The city currently has 91 publicly accessible UGSs [57], totaling 233 ha.

Figure 1.

Green ecological infrastructure of Porto. Source: Based on Municipal Master Plan of Porto [58].

However, when including proposed and currently requalification parks, this figure increases to 379 ha, and (ii) other green areas of ecological value, including private properties and green spaces within public facilities such as hospitals and schools, totaling 191 ha. Therefore, the existing ecological system of the city totals 424 ha, corresponding to approximately 10% of the urban area. Of the 91 publicly accessible UGSs, the 18 shown in Figure 1 are larger than 2 ha and were included in this study’s analysis.

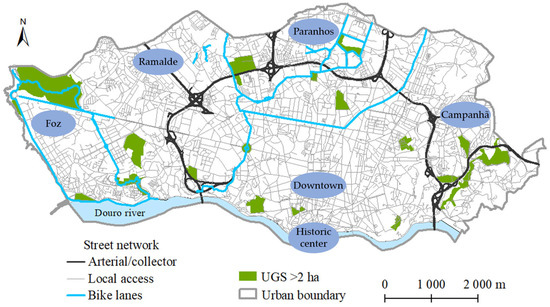

The infrastructure dedicated to active mobility in Porto is shown in Figure 2. It comprises the street network, which includes arterial and collector roads, as well as local access streets, and the network of bike lanes. As pedestrians and cyclists are not permitted to use arterial and collector roads, these were excluded from the analysis. Local access streets were included, as they allow pedestrian movement via sidewalks and bicycle use in traffic lanes. In recent years, the city has created bike lanes to enhance cyclist safety and comfort, connecting specific facilities, including UGS such as Parque da Cidade. However, these lanes do not yet form an integrated cycling network. Their current total length (32 km) remains significantly shorter than the length of local access roads in the city (665 km). For commuting, Porto’s population primarily relies on private motorized vehicles (55%), followed by public transport (22%). Among active modes, 22% of commuters walk, while only about 1% cycle [51]. Given this minimal cycling modal share and the current extent of infrastructure, Porto can be classified as a “starter cycling city” [10].

Figure 2.

Street network and cycling infrastructure in Porto. Source: Based on Municipal Master Plan of Porto [59].

In terms of transport policies, Porto has been promoting active modes of travel to reduce the impact of motorized traffic, particularly in the city center. Through initiatives such as “Zonas XXI,” the city aims to enhance public spaces and encourage multimodal transport in key areas. Measures include widening sidewalks, often by removing car parking in high-footfall locations, creating pedestrian-only or shared streets in the city center, and restricting car access in certain zones. New bike lanes are being constructed to connect residential areas with major hubs, and bicycle parking facilities are being expanded.

Porto currently lacks a formal plan to adopt the 15MC framework, although the concept is already being pursued in other Portuguese cities, such as Lisbon through the project “There’s Life in My Neighbourhood” [46]. Nevertheless, this study illustrates how 15MC principles can provide a valuable analytical lens for assessing and guiding improvements in the proximity and accessibility of UGS by active modes in Porto, where comparable goals are being pursued through different planning approaches.

2.2. Objective Approach

The objective component of this study involved spatial and geostatistical analyses using GIS, specifically ArcGIS 10.5. Most geographic data were sourced from Porto’s open geodata portals (https://opendata.porto.digital, https://mapas.cm-porto.pt/, accessed on 9 June 2025). UGS were digitized as polygons by georeferencing the Porto Municipal Ecological Map against high-resolution online satellite imagery. Only publicly accessible UGSs larger than 2 ha were considered, given their greater environmental, social, and health benefits. These UGSs were then visited in the field to record the coordinates of all formal access points (entrances/exits). In the absence of formal entries, as in the case of open spaces, the polygon centroid was used as the trip origin.

Proximity and accessibility to UGS were assessed using the network distance method. As noted by Papadopoulos et al. [60], network analysis is the most widely used approach for evaluating accessibility within the 15MC framework, as it produces more realistic and accurate results than straight-line methods. Because mobility follows the street network rather than direct paths, network distance better reflects the actual distances people must walk or cycle to reach their destinations [61]. As previously mentioned, street network data, including walking and cycling infrastructure, were obtained from Porto’s open geodata portals. These data underwent topological validation and repair to ensure the geometry was free from errors, such as duplicate lines or segments that do not properly connect, which can lead to incomplete or inaccurate network analyses. All corrections were performed using ArcGIS’s Topology tool. Next, UGS access points and centroids were set as trip origins in ArcGIS Network Analyst. Service areas were generated using network distances to identify all locations reachable within a 15-minute walk or bike ride from each UGS. These service areas were further classified into three travel-time bands: under 5 min, 5–10 min, and 10–15 min. Travel times were calculated using average speeds slightly below those commonly adopted in other studies, in order to reflect slower mobility among seniors and to partially account for Porto’s hilly topography, particularly in the eastern areas and historic center. Specifically, an average walking speed of 4.5 km/h was applied, compared to the 5 km/h often used in other studies [62,63], and an average cycling speed of 15 km/h was used, compared to higher speeds reported in other referential studies [64]. It was assumed that pedestrians and cyclists could use all streets except where access is explicitly prohibited, such as highways, expressways, and their associated ramps, such as the A20/VCI and its accesses. Walking and cycling travel times to UGS were calculated in ArcGIS using the network distance and the mentioned average speeds, according to Equation (1):

where Tmin is the travel time in minutes, L is the segment length in kilometers, and S is the average speed in kilometers per hour.

The population living within 15-minute walking and cycling service areas was estimated using the most detailed and recent Census data [51]. In ArcGIS, service-area polygons were overlaid on statistical tracts using the “Select by Location” tool to identify those intersecting each service area. The populations of these tracts were then summed to determine the number of residents living within a 15-minute walk or bike ride of a UGS. Based on these totals, the city’s overall service-to-population ratio was calculated.

Finally, the Gini coefficient was employed to assess the spatial equity of pedestrian and cycling access to UGS, weighted by population. Although originally developed in economics to measure income inequality, the Gini coefficient has been increasingly applied in transport and urban studies to evaluate the distribution of accessibility, including access to green spaces [65,66]. The index ranges from 0 to 1, where 0 indicates perfect equality and 1 reflects maximum inequality. It was calculated using Equation (2):

where G is the Gini coefficient, pi, the population, xi, the accessibility value for area i, μ, the population-weighted mean.

2.3. Subjective Approach

The subjective component aims to complement the objective analysis by capturing citizens’ perceptions of green space availability and the quality of walking and cycling routes to UGS. To this end, a questionnaire was administered, an approach widely recognized as effective for assessing pedestrians’ and cyclists’ experiences with active mobility infrastructure [67]. Participation was open to individuals aged 15 and older who either reside in or commute to Porto. This age threshold was chosen because individuals in this group generally have independent mobility patterns and make autonomous choices about accessing UGS. Including respondents from 15 years onwards also allowed us to capture the perspectives of younger users of UGS, while avoiding the ethical issues associated with surveying children under 15 without parental consent.

The questionnaire combined single-choice, multiple-choice, ranking, and open-ended questions, structured into four main sections. The first section collected demographic information, including gender, age, education level, and place of residence. The second section asked respondents to identify the green spaces they visit in Porto, their frequency of visits, reasons for visiting, and modes of transportation used. Non-regular visitors were also invited to suggest measures that could encourage more frequent use in the future. The third and fourth sections focused on evaluating walking and cycling conditions to UGS, respectively. Participants rated these conditions on a five-point Likert scale (1 = “very bad”, 2 = “bad”, 3 = “neither bad nor good”, 4 = “good”, and 5 = “very good”). The evaluation covered attributes known to influence safety and comfort, such as infrastructure quality, traffic safety, personal security, environmental conditions, and other relevant factors [9,10]. To enable comparative analysis across issues, the average evaluation score for each item was calculated based on participants’ Likert-scale responses, using Equation (3):

where is the average score, xi is Likert scale score, wi is the number of responses for each score xi, and n corresponds to the total number of score categories.

Prior to administering the questionnaire, a pilot test was conducted with a small group to identify confusing or ambiguous wording, comprehension issues, and unclear instructions. Feedback from these participants was used to refine and improve the instrument before full deployment. The stated-preference data were then collected through an online and in-person survey administered between 13 May and 12 August 2024.

Data collection was carried out in two stages. In the first stage, the online questionnaire was disseminated via social media, university mailing lists (University of Minho and University of Porto), and QR codes displayed at UGS entrances. As these are open public spaces, no formal authorization was required for displaying the QR codes.

This online format offered several advantages, including broad accessibility, the convenience for respondents to complete it at their own pace, and the potential to engage participants with strong opinions on the topic. However, older individuals are often harder to reach through online surveys [68]. To address this limitation and ensure adequate representation of older age groups, the second stage involved in-person surveys conducted in areas adjacent to UGS. In total, 18 paper surveys were collected, complementing 119 valid online responses, for a total of 137 valid questionnaires.

3. Results

3.1. Objective Evaluation

This section presents the results of the objective ArcGIS-based evaluation, assessing the accessibility of Porto’s UGS within a 15-minute walking or cycling distance and estimating the population residing within these service areas.

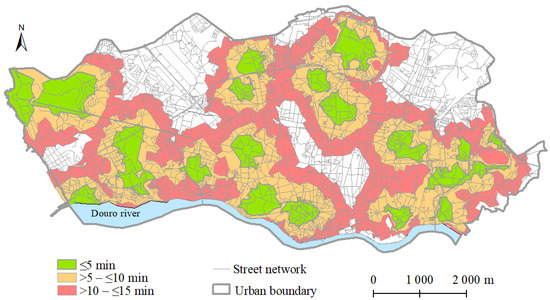

3.1.1. Pedestrian Accessibility to Urban Green Spaces

Pedestrian accessibility to the 18 UGSs measuring ≥2 ha was evaluated using the Service Area tool in ArcGIS Network Analyst. Isochrone maps were generated with each UGS serving as an origin point, calculating the travel “cost” for each segment of the pedestrian network. Three benchmark travel times (5, 10, and 15 min) were used to delineate catchment areas. Accordingly, each network-based service area represents the portions of the street network reachable within a 5-, 10-, or 15-minute walk from the respective UGS. The resulting accessibility patterns are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

15-minute walking accessibility to urban green spaces in Porto.

The results show that 74% of the urban area lies within a 15-minute walking distance of a UGS larger than 2 ha. However, as illustrated in Figure 3, accessibility to UGS varies significantly across the city. Notably, some residential areas, particularly in the northern sectors such as Paranhos and Ramalde, as well as parts of the downtown and Foz, are located beyond a 15-minute walking distance from the nearest UGS. To estimate the number of residents living within this range, a spatial analysis was carried out by overlaying the pedestrian service areas with the 2021 Census blocks. The results of this analysis are shown in Table 1. The results indicate that 84% of Porto’s population lives within a 15-minute walking distance of a UGS larger than 2 ha. However, the breakdown across the three time intervals reveals significant variation. Only 14.1% of residents are within a 5-minute walk, indicating that immediate proximity to UGS is limited for most of the population. The largest share (42.4%) lives within 10–15 min, suggesting that access for many requires a longer walk, while 27.2% reside within 5–10 min, reflecting moderate accessibility. Notably, 16.3% of residents live outside the 15-minute walking service areas, which represents a considerable proportion of the population.

Table 1.

Population coverage and cumulative UGS area within walking and cycling distances.

The Gini coefficient of 0.29 indicates moderate spatial inequity in walking access to UGS, with notable disparities in travel times persisting, namely in the areas previously identified as lying beyond a 15-minute walking distance.

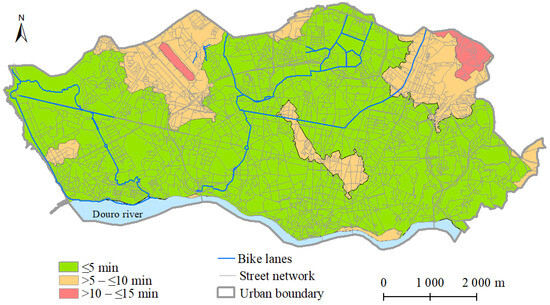

3.1.2. Cycling Accessibility to Urban Green Spaces

Cycling accessibility to the 18 UGSs was assessed using ArcGIS Network Analyst, considering travel times of 5, 10, and 15 min along the general street network. The resulting isochrone map, illustrating areas reachable by bicycle within these timeframes, is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

15-minute cycling accessibility to urban green spaces in Porto.

The analysis reveals that the entire city lies within a 15-minute cycling distance of a UGS larger than 2 ha. Notably, 76% of the urban area falls within the 5-minute cycling catchment of at least one UGS, while only 1.7% of the area, mainly in neighborhoods such as Paranhos and Ramalde, lies within the 10–15-minute catchment. However, these service areas were calculated using the general street network rather than dedicated cycling infrastructure. As shown in Figure 2, Porto’s bike lane network is fragmented, with only a few disconnected segments totaling 32 km, and just five UGS connected to them. Thus, it was not feasible to compute service areas based solely on dedicated cycling infrastructure. Although most urban areas fall within the 15-minute cycling catchment, cyclists must rely on the general road network, raising concerns regarding safety and comfort.

To estimate the population living within a 15-minute cycling distance of UGS, the cycling service areas were overlaid with the 2021 Census blocks. The results indicate that 78% of residents live within a 5-minute cycling distance, 21.5% reside within 5–10 min, and only 0.5% are located between 10 and 15 min away (Table 1).

The Gini coefficient for cycling accessibility to UGS is 0.13, reflecting relatively equitable access. This low Gini value indicates that cycling accessibility is relatively balanced across the population, with all areas falling within the 15-minute cycling catchment. This contrasts with walking accessibility, where greater disparities are observed, and underscores cycling’s potential as a key mode for promoting equitable access to UGS in Porto.

3.2. Complementary Subjective Evaluation

To complement the objective analysis, this section presents the results of the questionnaire survey, which was designed to capture citizens’ views on green space provision and the conditions for accessing these spaces on foot or by bicycle in Porto.

3.2.1. Sample Description

Table 2 presents the demographic profile of the participants. In total, 137 individuals completed the questionnaire. Most respondents were women, aged either 15–24 or 25–64 years, and were employed or studying in the city. While this sample yields a confidence level of approximately 95% with a margin of error of ±8.5%, it is relatively small and not fully representative of Porto’s population. As noted in the Introduction, the questionnaire was implemented as an exploratory and complementary tool to the GIS-based analysis, to provide qualitative insights into citizens’ perceptions of UGS provision and access rather than definitive, city-wide estimates.

Table 2.

Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents.

3.2.2. Usage of Urban Green Spaces and Preferences

This section examines the frequency of visits to UGS, the main reasons for these visits, the most frequently visited spaces, and participants’ suggestions for encouraging greater future use, based on the complementary questionnaire results.

When asked about visit frequency, the largest share of respondents (41.6%) reported visiting UGS weekly. Smaller proportions reported visiting daily (10.9%), every two weeks (14.6%), monthly (16.8%), or more rarely (16.1%). These figures suggest that most participants engage with UGS on a regular basis.

As shown in Table 3, walking emerged as the most frequently reported reason for visiting UGS (27%), followed by resting or relaxing (19%), spending time with friends or family (17%), and enjoying the view (13%), among others. These findings highlight the importance of UGSs as spaces for physical activity, leisure, and social interaction, underscoring their multifaceted role in urban life.

Table 3.

Reasons for visiting green spaces and actions to increase more regular use.

According to the complementary questionnaire, the three most frequently visited UGSs in Porto are Parque da Cidade, Palácio de Cristal, and Rotunda da Boavista, which together account for 50% of all responses. These are followed by Jardim da Cordoaria, Parque do Covelo, Parque de Serralves, and Jardim Botânico, each mentioned by 5–10% of respondents. The remaining green spaces were cited by fewer than 4%, suggesting more occasional or localized use. This concentration of visits in a small number of sites points to potential disparities in proximity, accessibility, or overall attractiveness across the UGS network.

Respondents who do not visit UGS regularly (i.e., less than weekly) were also asked to identify measures that could encourage more frequent use. As shown in Table 3, the most frequently cited factor was improved proximity to green spaces (23.6%), underscoring the importance of spatial distribution and its alignment with the 15MC concept. Other mentioned measures included organizing more events (16.8%) and adding facilities (14.0%), reflecting the influence of functional and social enhancements in attracting users.

3.2.3. Travel Experiences and Perceptions

This section examines the modes of transport used to reach UGS, perceived travel times, and respondents’ evaluation of walking and cycling conditions.

When considering transport modes, walking emerged as the most frequently reported option (42.3%), followed by private cars (30.0%) and public transport (20.5%). Other modes, such as cycling (2.9%), combined modes (3.6%), and alternatives like e-scooters, were reported by only a small share of respondents. Although the objective GIS analysis suggested that all residents can access a UGS within 15 min by bicycle, the questionnaire confirmed that cycling remains among the least used options. In contrast, walking stands out as the most common choice, despite the fact that the objective analysis also showed that not all areas of the city provide access to UGS within a 15-minute walk.

Regarding perceived travel times, the majority of respondents (57.7%) indicated that they can reach a UGS within 15 min, which aligns with the core principle of the 15MC. However, a substantial share (42.3%) reported longer travel times, highlighting challenges to the 15MC goal of equitable access to green spaces. Among respondents who walk to a UGS, 67% reported travel times of up to 15 min. Interestingly, all participants who cycle indicated travel times between 5 and 10 min.

Another goal of the complementary questionnaire was to evaluate the conditions experienced by pedestrians and cyclists when traveling to UGS. Respondents rated various attributes affecting the comfort and safety of walking and cycling using a 5-point Likert scale. To aid interpretation, a weighted average (Equation (3)) was calculated for each parameter. The assessed attributes, along with their corresponding average scores and variability, are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Evaluation of walking and cycling accessibility to urban green spaces.

Overall, participants rated the walking conditions to UGS positively, with most attributes scoring slightly above 3 on a 5-point scale. Notably, environmental quality, including factors such as noise, fumes, and air pollution at sidewalk level, was the only attribute with an average score below 3, indicating a common concern among respondents. In contrast, traffic safety and sidewalk continuity received the highest ratings, both exceeding 3.3. Although all attributes were rated across the full 1–5 scale, the relatively low standard deviations suggest a moderate consistency in participants’ perceptions.

Regarding cycling conditions, participants rated them significantly lower than walking conditions. All cycling attributes received average scores below 3, highlighting notable limitations in the city’s cycling infrastructure and overall conditions. The lowest-rated attribute was the continuity of cycle lanes, closely followed by the availability and quality of the lanes themselves, indicating that fragmentation and inadequate infrastructure are perceived as key barriers to cycling. Bicycle parking and environmental quality received relatively higher, though still modest, ratings. Despite some variability in responses, standard deviations were relatively low, suggesting consistent perceptions among participants, particularly regarding traffic safety and cycle lane continuity.

4. Discussion

This section presents a comprehensive discussion of the findings, focusing on the results obtained with the objective and subjective evaluations and on the relationship between them along with extent to which Porto is a 15MC.

4.1. Discussion of the Objective Evaluation

Urbanization has led to an estimated 60% reduction in Porto’s green space over the past century [55]. Currently, the city provides 18.3 m2 of green space per capita, a value that exceeds the World Health Organization’s minimum of 9 m2 per inhabitant but falls short of the ideal 50 m2 per capita [69,70]. This green space ratio is higher than the typically low values reported for southern European cities [41] and is comparable to that found in Barcelona and Amsterdam [69,70], which are renowned for their urban livability and green infrastructure. However, this metric is inflated by large peripheral parks, like Parque da Cidade (80 ha) and Parque Oriental (20 ha). Since these spaces are distant from the city center and most residential areas, they are car-oriented and difficult to reach on foot. Consequently, even though urban studies show residents are often willing to travel beyond 300–500 m for UGS, this often leads to the use of motorized transport [71].

The spatial analysis revealed that 84% of Porto’s population falls within a 15-minute walking distance of a UGS, and the entire city is within a 15-minute cycling distance, generally aligning with the concepts of the15MC. It is important to note that these figures represent theoretical maximum catchment areas, calculated based on the street network and average travel speeds. Focusing specifically on walking access, the analysis highlights a significant accessibility gap: 16% of residents, primarily in Paranhos and Ramalde, live outside the 15-minute walking threshold. Furthermore, only 14% of the total population is within a 5-minute walk (approximately 300 m) of a UGS. This low proximity is a concern, as established literature suggests residents should be within 300 m of a UGS (≥2 ha), given that close proximity can increase visit frequency up to threefold [61,72]. The recent 3–30–300 rule further reinforces this, recommending that homes, schools, and workplaces should have a view of at least 3 trees, be located in neighborhoods with over 30% tree canopy cover, and be within 300 m walking distance of a park [73]. Compared to other European cities, Porto performs poorly on this measure: for example, 59% of Berlin’s residents and 62% of Barcelona’s residents live within 300 m of a UGS [41,74].

The 15MC framework defines walking time limits based on people with normal mobility [75]. To better accommodate vulnerable groups, specifically children, the elderly, and disabled individuals, who typically walk slower, some authors have proposed more stringent 5-minute and 10-minute city concepts [76]. This refined consideration is particularly critical in Porto, where 26.0% of the population is over 65 years old, a figure exceeding the national average of 23.7% [51]. Therefore, while the majority of residents are within the 15-minute threshold, the severely limited coverage within the 5-minute range strongly suggests that walking access to UGS is far from optimal for these groups. Furthermore, the Gini coefficient revealed a moderate spatial inequity in walking access to UGS, reflecting disparities both within the 15-minute catchment area and the persistence of areas that fall entirely outside this maximum limit.

Regarding cycling access, the analysis showed that the entire population of Porto is within a 15-minute cycling distance of a UGS, and the Gini coefficient confirms a lower spatial inequity compared to walking access. Nonetheless, this widespread potential is not reflected in mobility patterns. Official statistics report that cycling accounts for only 1% of commuting trips in the city [51]. Like many Portuguese cities, Porto can be classified as a ‘starter’ cycling city [10] or a city with low cycling maturity [77], where cycling is not yet recognized as a legitimate mode of transportation. This low uptake is attributable to a confluence of factors [78], such as fragmented and inadequate cycling infrastructure, prevalent safety concerns, and a deeply entrenched car-oriented culture common in southern European contexts [78]. Moreover, the existing infrastructure predominantly serves recreational routes along the Douro River and Atlantic coast, leaving central and eastern neighborhoods severely deficient in continuous, safe cycling infrastructure.

This study also highlights the inherent challenge of implementing the 15MC in a compact and historically dense city like Porto. The city’s morphology, characterized by narrow streets, irregular layouts, and a car-oriented culture, combined with insufficient active mobility infrastructure and the location of large urban parks on the periphery, creates a significant barrier. While GIS analysis suggests a high potential for active accessibility, these urban characteristics and established cultural travel habits result in a spatial configuration that impedes both the implementation of the 15MC and the promotion of equitable active access to UGS. Consequently, despite the GIS findings that the majority of the population is within a 15-minute range, actual usage may be suppressed by multiple factors, including perceived travel distance, as suggested by the questionnaire data. Promoting more equitable and inclusive active access to UGS therefore requires an integrated planning approach that directly addresses these local specificities. In this regard, four planning measures appear particularly relevant to address the unique challenges observed in Porto:

- (i)

- Expanding and strategically locating green spaces: new UGSs should be created and existing ones expanded, prioritizing residential areas currently outside walking catchment zones. Such interventions should be carefully planned to mitigate green gentrification, a phenomenon that can significantly raise land and housing prices, particularly in the case of large-scale projects [24];

- (ii)

- Improving active mobility infrastructure and connections: pedestrian and cycling connections between UGS and residential areas, should be improved, preferably through safe, direct, and comfortable green corridors. This is crucial for vulnerable users (seniors, children) but also benefits the general population, as evidence shows cyclists prefer tree-lined routes that offer attractive landscapes and reduce exposure to pollution and noise [79]. To counter the rainy winter conditions that discourage active modes, infrastructure should be weather-resilient, including sheltered paths and permeable pavements. Cycling must be supported through an expanded and better-connected network, complemented by adequate facilities like secure bicycle parking near UGS and transport nodes. Finally, the barrier posed by steeper gradients in parts of the city (historic center and eastern zones) should be mitigated through alternative routes, improved public transport connections, or mechanical aids such as elevators;

- (iii)

- Addressing cultural reliance on private vehicles: the strong cultural reliance on private vehicles, which fundamentally shapes accessibility patterns, must be progressively addressed. This can be achieved through awareness and educational campaigns, as well as incentives for active travel, particularly cycling, since these measures have proven effective in encouraging behavioral change [15];

- (iv)

- Integrating needs through participatory planning: it is essential to incorporate population needs and preferences into planning through participatory approaches, ensuring that policies are understood as supportive rather than restrictive. This is particularly important given recent misinterpretations of the 15M model, which has been portrayed in some public debates as anti-car or limiting personal freedom [80]. In reality, the 15MC framework seeks to broaden opportunities for all by integrating multiple transport modes and enhancing local accessibility, thereby promoting inclusive and sustainable mobility.

4.2. Discussion of the Complementary Subjective Evaluation

The questionnaire results, though exploratory, provide valuable complementary insights to the GIS-based accessibility analysis. Participants reported regular visits to UGS, with 42% indicating weekly attendance. This visitation frequency is comparable to previous studies conducted in Porto (ranging from 37% to 56%) [81,82], yet it remains lower than rates observed in Lisbon [82] and in some northern European cities [20,83]. A key factor behind this lower frequency appears to be proximity and size. Higher visitation rates in northern cities, for example, are linked to a greater proportion of residents living within the 300 m threshold. This size preference is likely driven by the broader range of activities, amenities, and event opportunities offered by larger spaces, a finding that aligns with literature showing that larger green spaces are positively associated with higher frequencies of walking, exercising, and relaxing [84].

Overall, participants value UGS primarily for physical activity, social interaction, and contact with the surrounding landscape. Consistent with previous studies [20,85], walking was reported as the main reason for visiting UGS. Other frequent motives, such as relaxing, socializing, and enjoying the view, also align with key drivers identified in the literature for using these spaces [86,87].

Distance was the most frequently reported barrier to regularly visiting UGS. This challenge is partly rooted in the city’s compact urban structure, which limits the availability of large green spaces. Addressing this requires strategic action, such as the creating of a network of community or pocket parks. Although these smaller parks may offer fewer benefits than larger spaces (over 2 ha), they can still provide more accessible and nearby green areas, while also helping to mitigate the risk of gentrification often associated with large-scale projects [24,26]. Beyond distance, the findings suggest that enhancing UGS attractiveness has significant potential to boost regular visits. This enhancement could be achieved through organizing more public events, providing additional facilities, and improving both maintenance and safety of existing spaces.

Regarding travel experiences and perceptions, 42% of survey participants accessed UGS on foot. Although walking was the most preferred mode, this share suggests a lower reliance on walking than reported in other cities: for instance, walking accounts for at least 60% of park access in Lisbon [86], 79% in Spain [88], and 50% in Bucharest [79]. Cycling remains a marginal option at just 2.9% of access modes, slightly above the local commuting average but far below levels reported in other European cities [89,90]. Conversely, the reported reliance on cars is significant at 30%. The low walking share and high car use are likely rooted in several factors: the uneven distribution of large UGSs across the city, adverse weather conditions (especially rainy winters), the presence of hilly streets (particularly in the eastern and historic center), and cultural habits that discourage active mobility. For example, a recent study in Porto confirmed that adverse weather is among the most disliked aspects of walking in the city [68].

In this study, 58% of participants reported being able to access a UGS within 15 min. This aligns closely with the objective analysis, which indicated that the majority of residents live within a 15-minute walking or cycling distance of such spaces. Notably, this proportion is higher than in Lisbon, where only 35% of participants reported similar results [86]. This difference in perceived access likely stems from Porto’s smaller size and more compact urban structure.

The subjective evaluation of active travel conditions for accessing UGS reveals a stark difference in perception between cycling and walking. Cycling conditions received a substantially low average score of 2.27 on the 5-point Likert scale, with availability and continuity of cycling lanes, alongside traffic safety, receiving the poorest ratings. This poor perception directly supports the objective GIS analysis, which showed the cycling network is limited and fragmented. The key implication is that despite the entire city being objectively within a 15-minute cycling distance of UGS, the perceived poor quality and discontinuity of the infrastructure likely reduces practical uptake. Previous research confirms that such deficiencies deter cycling in general by forcing riders onto unsafe, mixed-traffic streets, which can be intimidating [10,89], and specifically discourage cycling to UGS [79]. The residual cycling share reported in official statistics and confirmed in the questionnaire, is consequently an outcome of both infrastructural deficits and safety concerns, underscoring the necessity of substantial investment in connecting UGS to residential areas and urban hubs. Pedestrian access conditions were perceived more favorably (average score of 3.19), indicating a basic level of adequacy for walking. However, improvements are needed concerning sidewalk surface quality, street trees, shaded pathways, and general environmental conditions, as these factors are crucial for enhancing pedestrian safety and comfort [91].

4.3. Future Research and Limitations

This study provided a comprehensive assessment of access to UGS in Porto by walking and cycling within the framework of the 15MC, combining spatial analysis with a complementary user questionnaire. Despite its contributions, several limitations highlight important opportunities for future research.

First, the objective analysis simplified real-world conditions in several ways. It did not explicitly consider the quality of UGS (e.g., available facilities, amenities), which is known to strongly influence use and visitation frequency. Furthermore, the analysis assumed uniform walking and cycling speeds, neglecting numerous factors that can reduce actual travel speeds, such as slopes in some parts of the city. Similarly, crucial aspects affecting the safety and comfort of active travel, like sidewalk surface quality, traffic exposure, and weather conditions, were not evaluated. Future research should incorporate these variables to provide a more nuanced and realistic understanding of active accessibility to UGS.

Second, the complementary subjective evaluation relied on a relatively modest sample of 137 responses, which limits the generalizability of the survey results and does not fully represent the city’s diverse population. Nevertheless, the questionnaire was implemented as an exploratory tool to provide targeted, qualitative insights into citizens’ perceptions of UGS provision and accessibility, complementing the objective GIS analysis. Future studies should aim to expand the sample size and ensure a more balanced distribution across gender, age, and other relevant factors to enhance representativeness. Additionally, the questionnaire was conducted during the spring and summer, meaning participants’ perceptions may primarily reflect seasonal conditions rather than year-round experiences. Longitudinal studies covering different seasons and times of day would be beneficial for capturing temporal variations in UGS access. Furthermore, as with all self-reported data, the responses inherently carry the risk of biases related to individual interpretation and recall errors.

Finally, the scope of this study was exclusively focused on Porto. While the methodology is reproducible, applying this integrated approach in other urban contexts would allow for robust cross-city comparisons. Such comparative analysis could identify best practices and provide crucial insights into structural patterns that either facilitate or impede equitable and active access to UGS under the 15MC framework.

5. Conclusions

Close and equitable access to UGS is essential for ensuring environmental quality and promoting urban livability. Given their role in supporting public health, social interaction, and environmental resilience, UGSs are a fundamental element of the 15MC model. This study utilized the 15MC framework to assess UGS proximity and active accessibility in Porto, combining objective spatial analysis with subjective user perceptions. The results highlight a critical finding: despite the city’s relatively good spatial provision of green areas, achieving equitable active access remains challenging. This is evidenced by the Gini coefficient, which indicates a moderate degree of spatial inequity in walking access. Specifically, the positive overall provision is skewed by large peripheral parks like Parque da Cidade and Parque Oriental. These sites, while contributing substantial green area, are poorly connected for pedestrians from central and residential neighborhoods, thus perpetuating spatial disparities.

The analysis revealed a contradiction between potential and reality: while a significant proportion of the population (84%) is within a 15-minute walking distance of UGS, and the entire city is within a 15-minute cycling range, these results are counterbalanced by notable gaps in infrastructure and spatial equity. Cycling, despite the city’s compact urban structure, remains a marginal mode due to limited and fragmented infrastructure, safety concerns, and a low cycling culture. The objective findings were mirrored by the complementary subjective component, which indicated strong dissatisfaction with cycling conditions and only moderate satisfaction with pedestrian environments.

These findings carry important implications for urban planning in Porto. Local planning instruments, such as the Municipal Master Plan, must integrate the core principles of the 15MC as a central strategy aligned with broader sustainable development objectives. It is vital to implement these principles (proximity along with diversity, density, and digitalization) in a way that prevents spatially selective benefits and effectively reduces the measured inequities in access to UGS through active modes of transport, particularly for walking. To achieve this, policy and planning efforts must focus on enhancing local connectivity, expanding existing UGSs, creating new ones in underserved neighborhoods, and investing in safe, continuous cycling and walking green corridors that link UGSs across the city. Achieving this vision requires moving beyond the simple provision of green space towards a more holistic approach that considers spatial equity, infrastructure quality, and user perceptions. Strengthening these dimensions will ensure that UGSs contribute more effectively to urban livability, inclusivity, and sustainability, in line with the goals of SDG 11.7.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J.A. and F.F.; methodology, M.J.A.; software, M.J.A.; validation, M.J.A. and F.F.; formal analysis, M.J.A.; investigation, M.J.A.; resources, M.J.A. and F.F.; data curation, M.J.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.J.A. and F.F.; writing—review and editing, F.F.; visualization, M.J.A.; supervision, F.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to its compliance with the ethical guidelines of the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Minho (CEC-UMinho V3, 2025), specifically Articles 17 and 18 on scientific research ethics. The study used anonymous questionnaires for Porto residents and visitors, collecting only non-identifiable socio-demographic data (e.g., age group, gender) and opinions on urban mobility and green space accessibility—no personal identifiable information was gathered, and responses were processed and reported aggregately. Participation was voluntary, with respondents informed of the study’s academic purposes beforehand. These characteristics meet the exemption criteria under the University of Minho’s ethical framework, and the research also complies with national and European data protection and human research ethics regulations.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to privacy restrictions, the data are not publicly available.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the staff from their respective organizations who contributed to this work, as well as all participants who voluntarily took part in the questionnaire survey.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 15MC | 15-minute city |

| GIS | Geographic Information Systems |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| UGS | Urban Green Space |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Shakeri, S.; Motieyan, H.; Azmoodeh, M. Comparative analysis of 15-minute neighborhoods through different cumulative-based accessibility measures. GeoJournal 2024, 89, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Kwan, M.; Wang, J. Developing the 15-minute city: A comprehensive assessment of the status in Hong Kong. Travel Behav. Soc. 2024, 34, 100666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C.; Allam, Z.; Chabaud, D.; Gall, C.; Pratlong, F. Introducing the “15-minute city”: Sustainability, resilience and place identity in future post-pandemic cities. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaglione, F.; Gargiulo, C.; Zucaro, F.; Cottrill, C. Urban accessibility in a 15-minute city: A measure in the city of Naples, Italy. Transp. Res. Proc. 2022, 60, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprotti, F.; Duarte, C.; Joss, S. The 15-minute city as paranoid urbanism: Ten critical reflections. Cities 2024, 155, 105497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khavarian-Garmsir, A.; Sharifi, A.; Hajian, M.; Moradi, Z. From garden city to 15-minute city: A historical perspective and critical assessment. Land 2023, 12, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, B.; Chamusca, P. The 15-minute city in Portugal: Reality, aspiration, or utopia? Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K. Time to challenge the 15-minute city: Seven pitfalls for sustainability, equity, livability, and spatial analysis. Cities 2024, 153, 105274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, F.; Ribeiro, P.; Conticelli, E.; Jabbari, M.; Papageorgiou, G.; Tondelli, S.; Ramos, R. Built environment attributes and their influence on walkability. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2022, 16, 660–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, F.; Ribeiro, P.; Neiva, C. A planning practice method to assess the potential for cycling and to design a bicycle network in a starter cycling city in Portugal. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, A.; Nazir, H.; Qazi, A. Exploring the 15-minutes city concept: Global challenges and opportunities in diverse urban contexts. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapiador, L.; Gomez, J.; Vassallo, J. Exploring the relationship between public transport use and COVID-19 infection: A survey data analysis in Madrid Region. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 104, 105279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, R.; Akaraci, S.; Wang, R.; Reis, R.; Hallal, P.; Pentland, S.; Millett, C.; Garcia, L.; Thompson, J.; Nice, K.; et al. City mobility patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic: Analysis of a global natural experiment. Lancet Public Health 2024, 9, e896–e906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akrami, M.; Sliwa, M.; Rynning, M. Walk further and access more! Exploring the 15-minute city concept in Oslo, Norway. J. Urban Mobil. 2024, 5, 100077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, C. Accessibility and Availability of Urban Green Areas Within the 15-minute City Scope: Lisbon Case Study. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, Y.; Jung, S. Spatial equity of urban park distribution: Examining the floating population within urban park catchment areas in the context of the 15-minute city. Land 2024, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.; Fonseca, F.; Pires, M.; Mendes, B. SAUS: A tool for preserving urban green areas from air pollution. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 46, 126440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, F.; Silva, L.; Martins, S.; Almeida, M.; Reis, C.; Lopes, H. The role of vegetation in attenuating the urban heat island (UHI): A case study in Guimarães, Portugal. In Studies in Systems, Decision and Control; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 230, pp. 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.; Lopes, H.; Silva, J.; Reis, C.; Fonseca, F. The nexus of nature-based solutions and sustainability in cities: Vegetation’s impact on particulate matter capture and traffic noise reduction. In Studies in Systems, Decision and Control; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 230, pp. 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.; Zanocco, C. Assessing public attitudes towards urban green spaces as a heat adaptation strategy: Insights from Germany. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 245, 105013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F. Spatial equity analysis of urban green space based on spatial design network analysis (sDNA): A case study of central Jinan, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 60, 102256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Marín, A.; Garrido-Cumbrera, M. Did the COVID-19 pandemic influence access to green spaces? Results of a literature review during the first year of pandemic. Landsc. Ecol. 2024, 39, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolimenakis, A.; Solomou, A.; Proutsos, N.; Avramidou, E.; Korakaki, E.; Karetsos, G.; Maroulis, G.; Papagiannis, E.; Tsagkari, K. The socioeconomic welfare of urban green areas and parks; a literature review of available evidence. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, L.V.; Pereira, P. Relevant landscape components in a large urban green space in Oporto (Portugal). Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 99, 128421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L.; Hochuli, D. Defining greenspace: Multiple uses across multiple disciplines. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 158, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Qureshi, S.; Haase, D. Human-environment interactions in urban green spaces—A systematic review of contemporary issues and prospects for future research. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2015, 50, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fors, H.; Molin, J.; Murphy, M.; van den Bosch, C. User participation in urban green spaces–For the people or the parks? Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 722–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fagerholm, N.; Skov-Petersen, H.; Beery, T.; Wagner, A.; Olafsson, A. Shortcuts in urban green spaces: An analysis of incidental nature experiences associated with active mobility trips. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 82, 127873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Bosch, M.; Egorov, A.; Mudu, P.; Uscila, V.; Barrdahl, M.; Kruize, H.; Kulinkina, A.; Staatsen, B.; Swart, W.; Zurlyte, I. Development of an urban green space indicator and the public health rationale. Scand. J. Public Health 2016, 44, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, P.; Xu, L.; Yue, W.; Chen, J. Accessibility of public urban green space in an urban periphery: The case of Shanghai. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 165, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comber, A.; Brunsdon, C.; Green, E. Using a GIS-based network analysis to determine urban greenspace accessibility for different ethnic and religious groups. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 86, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Jim, C.; Wang, H. Assessing the landscape and ecological quality of urban green spaces in a compact city. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 121, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mears, M.; Brindley, P.; Maheswaran, R.; Jorgensen, A. Understanding the socioeconomic equity of publicly accessible greenspace distribution: The example of Sheffield, UK. Geoforum 2019, 103, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipperijn, J.; Bentsen, P.; Troelsen, J.; Toftager, M.; Stigsdotter, U. Associations between physical activity and characteristics of urban green space. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Broomhall, M.; Knuiman, M.; Collins, C.; Douglas, K.; Ng, K.; Lange, A.; Donovan, R. Increasing walking: How important is distance to, attractiveness, and size of public open space? Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaczynski, A.; Potwarka, L.; Saelens, P. Association of park size, distance, and features with physical activity in neighborhood parks. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 1451–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Onishi, A.; Chen, J.; Imura, H. Quantifying the cool island intensity of urban parks using ASTER and IKONOS data. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 96, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahn, P.; Stigsdotter, U. Landscape planning and stress. Urban For. Urban Green. 2003, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinali, M.; Beenackers, M.; van Timmeren, A.; Pottgiesser, U. The relation between proximity to and characteristics of green spaces to physical activity and health: A multi-dimensional sensitivity analysis in four European cities. Environ. Res. 2024, 241, 117605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Healthy cities for building back better. Political statement of the WHO European Healthy Cities Network; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kabisch, N.; Strohbach, M.; Haase, D.; Kronenberg, J. Urban green space availability in European cities. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 70, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ståhle, A. More green space in a denser city: Critical relations between user experience and urban form. Urban Des. Int. 2010, 15, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Urban Green Spaces: A Brief for Action; WHO: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency. Who Benefits from Nature in Cities? Social Inequalities in Access to Urban Green and Blue Spaces Across Europe (Briefing No. 15/2021); EEA: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, E.; Kabasinguzi, I.; Randhawa, G.; Ali, N. Factors influencing urban greenspace use among a multi-ethnic community in the UK: The Chalkscapes Study. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 92, 128210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büttner, B.; Seisenberger, S.; McCormick, B.; Silva, C.; Teixeira, J.; Papa, E.; Cao, M. Mapping of 15-minute city practices overview on strategies, policies and implementation in Europe and beyond. Report from DUT’s 15-minute City Transition Pathway; Driving Urban Transitions. Vienna, Austria, 2024. Available online: https://dutpartnership.eu/news/new-publication-mapping-15-minute-city-practices (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Shoina, M.; Voukkali, I.; Anagnostopoulos, A.; Papamichael, I.; Stylianou, M.; Zorpas, A. The 15-minute city concept: The case study within a neighbourhood of Thessaloniki. Waste Manag. Res. 2024, 42, 694–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Zhai, S.; Song, G.; He, X.; Song, H.; Chen, J.; Liu, H.; Feng, Y. Assessing inequity in green space exposure toward a “15-minute city” in Zhengzhou, China: Using deep learning and urban big data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, L.; Oviedo, D.; Cantillo-Garcia, V. Is proximity enough? A critical analysis of a 15-minute city considering individual perceptions. Cities 2024, 148, 104882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, H.; Ferreira, S. Advancing sustainable urban mobility: An empirical travel time analysis of the 15-minute city model in Porto. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2025, 21, 101551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Portugal. Census 2021; Statistics Portugal: Lisbon, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Portuguese Institute for Sea and Atmosphere. Climate normal of Porto (1991–2020); IPMA: Lisbon, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Municipality of Porto. Municipal Master Plan of Porto (Strategy for a network of cycle routes for the Greater Porto Area: The case of Porto). Available online: https://pdm.cm-porto.pt/documents/44/Rede_de_circuitos_ciclaveis_Caso_do_Porto_2014.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Alves, F.; Cruz, S.; Ribeiro, A.; Silva, A.; Martins, J.; Cunha, I. Walkability index for elderly health: A proposal. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, H.; Vidal, D.; Cherif, N.; Silva, L.; Remoaldo, P. Green infrastructure and its influence on urban heat island, heat risk, and air pollution: A case study of Porto (Portugal). J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 376, 124446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madureira, H.; Andresen, T.; Monteiro, A. Green structure and planning evolution in Porto. Urban For. Urban Green. 2011, 10, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, P.; Alves, P.; Fernandes, C.; Guilherme, F.; Gonçalves, C. Revision of the Municipal Master Plan of Porto: Biophysical Support and Environment. Ecological Structure and Biodiversity. Characterization and Diagnosis Report; Municipality of Porto: Porto, Portugal, 2018. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Municipality of Porto. Municipal Master Plan of Porto (Urban Parks and Gardens). Available online: https://portalgeo.cm-porto.pt/arcgis/apps/sites/#/mapas-do-porto/apps/da2e7cbb6f384514856211466bf68609/explore (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Municipality of Porto. Municipal Master Plan of Porto (Mobility). Available online: https://portalgeo.cm-porto.pt/arcgis/apps/sites/#/mapas-do-porto/apps/507724d6cfeb4038b19e862b6ca8cb1f/explore (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Papadopoulos, E.; Sdoukopoulos, A.; Politis, I. Measuring compliance with the 15-minute city concept: State-of-the-art, major components and further requirements. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 99, 104875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, B.; Pereira, A. Index for evaluation of public parks and gardens proximity based on the mobility network: A case study of Braga, Braganza and Viana do Castelo (Portugal) and Lugo and Pontevedra (Spain). Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 34, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, P.; Fonseca, F. Students’ home-university commuting patterns: A shift towards more sustainable modes of transport. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2022, 10, 954–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.; Moudon, A.; Hurvitz, P.; Saelens, B. Differences in behavior, time, location, and built environment between objectively measured utilitarian and recreational walking. Transp. Res. D 2017, 57, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkin, J.; Rotheram, J. Design speeds and acceleration characteristics of bicycle traffic for use in planning, design and appraisal. Transp. Policy 2010, 17, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Zhong, M.; Akuh, R.; Safdar, M. Public transport equity with the concept of time-dependent accessibility using Geostatistics methods, Lorenz curves, and Gini coefficients. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2023, 11, 100956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.; Liu, D.; Kwan, M.-P. Evaluating spatial variation of accessibility to urban green spaces and its inequity in Chicago: Perspectives from multi-types of travel modes and travel time. Urban For. Urban Green. 2025, 104, 128593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, F.; Rodrigues, A.; Silva, H. Pedestrian perceptions of sidewalk paving attributes: Insights from a pilot study in Braga. Infrastructures 2025, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, F.; Papageorgiou, G.; Conticelli, E.; Jabbari, M.; Ribeiro, P.; Tondelli, S.; Ramos, R. Evaluating attitudes and preferences towards walking in two European cities. Future Transp. 2024, 4, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboulnaga, M.; Ashour, F.; Elsharkawy, M.; Lucchi, E.; Gamal, S.; Elmarakby, A.; Haggagy, S.; Karar, N.; Khashaba, N.; Abouaiana, A. Urbanization and drivers for dual capital city: Assessment of urban planning principles and indicators for a ‘15-minute city’. Land 2025, 14, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiu, D.; Iojă, C.; Pătroescu, M.; Breuste, J.; Artmann, M.; Niță, M.; Grădinaru, S.; Hossu, C.; Onose, D. Is urban green space per capita a valuable target to achieve cities’ sustainability goals? Romania as a case study. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 70, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, M.; Le Texier, M.; Caruso, G. How far do people travel to use urban green space? A comparison of three European cities. Appl. Geogr. 2022, 141, 102673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handley, J.; Pauleit, S.; Slinn, P.; Barber, A.; Baker, M.; Jones, C.; Lindley, S. Accessible natural green space standards in towns and cities: A review and toolkit for their implementation. Engl. Nature Res. Rep. 2003, 526, 98. [Google Scholar]

- Croeser, T.; Sharma, R.; Weisser, W.; Bekessy, S. Acute canopy deficits in global cities exposed by the 3-30-300 benchmark for urban nature. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; Dadvand, P.; Márquez, S.; Bartoll, X.; Barboza, E.; Cirach, M.; Borrell, C.; Zijlema, W. The evaluation of the 3-30-300 green space rule and mental health. Environ. Res. 2022, 215, 114387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, B.; Ko, C.; Im, D.; Kang, W. Network-based assessment of urban forest and green space accessibility in six major cities: London, New York, Paris, Tokyo, Seoul, and Beijing. Urban For. Urban Green. 2025, 107, 128781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staricco, L. 15-, 10-or 5-minute city? A focus on accessibility to services in Turin, Italy. J. Urban Mobil. 2022, 2, 100030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix, R.; Moura, F.; Clifton, K. Maturing urban cycling: Comparing barriers and motivators to bicycle of cyclists and non-cyclists in Lisbon, Portugal. J. Transp. Health 2019, 15, 100628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, R.; Bandeira, J.; Vilaça, M.; Rodrigues, M.; Fernandes, J.; Coelho, M. Introducing new criteria to support cycling navigation and infrastructure planning in flat and hilly cities. Transp. Res. Proc. 2020, 47, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoia, N.; Niţă, M.; Popa, A.; Iojă, I. The green walk—An analysis for evaluating the accessibility of urban green spaces. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 75, 127685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlahov, D.; Kurth, A. The “15-Minute City” Concept in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Climate Change. J. Urban Health 2024, 101, 669–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madureira, H.; Nunes, F.; Oliveira, J.; Cormier, L.; Madureira, T. Urban residents’ beliefs concerning green space benefits in four cities in France and Portugal. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madureira, H.; Nunes, F.; Oliveira, J.; Madureira, T. Preferences for urban green space characteristics: A comparative study in three Portuguese cities. Environments 2018, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipperijn, J.; Ekholm, O.; Stigsdotter, U.; Toftager, M.; Bentsen, P.; Kamper-Jørgensen, F.; Randrup, T. Factors influencing the use of green space: Results from a Danish national representative survey. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 95, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozalo, G.; Morillas, J.; González, D. Perceptions and use of urban green spaces on the basis of size. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 46, 126470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuvonen, M.; Sievänen, T.; Tönnes, S.; Koskela, T. Access to green areas and the frequency of visits–A case study in Helsinki. Urban For. Urban Green. 2007, 6, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viebrantz, P.; Fernandes-Jesus, M. Visitors’ perceptions of urban green spaces: A study of Lisbon’s Alameda and Estrela Parks. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 755423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romelli, C.; Anderson, C.; Fagerholm, N.; Hansen, R.; Albert, C. Why do people visit or avoid public green spaces? Insights from an online map-based survey in Bochum, Germany. Ecosyst. People 2025, 21, 2454252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egea-Cariñanos, P.; Calaza-Martínez, P.; Roche, D.; Cariñanos, P. Uses, attitudes and perceptions of urban green spaces according to the sociodemographic profile: An exploratory analysis in Spain. Cities 2024, 150, 104996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žlender, V.; Thompson, C. Accessibility and use of peri-urban green space for inner-city dwellers: A comparative study. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 165, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalón, S.; Chiabai, A.; Mc Tague, A.; Artaza, N.; Ayala, A.; Quiroga, S.; Kruize, H.; Suárez, C.; Bell, R.; Taylor, T. Providing access to urban green spaces: A participatory benefit-cost analysis in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, H.; Fonseca, F.; Rodrigues, A.; Palha, C. Engineering-based evaluation of sidewalk pavement materials: Implications for pedestrian safety and comfort. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]