Bridging the Gap: The Gendered Impact of Infrastructure on Well-Being Through Capability and Subjective Well-Being Approaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- The present study seeks to explore the manner in which access to infrastructure influences subjective well-being and the development of capabilities for both women and men.

- (2)

- The second research question concerns the question of whether these effects are conditioned by the type of infrastructure and the size of the municipality.

- (3)

- With regard to public policy, what implications can be deduced from these differentiated effects?

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Conceptualizing Well-Being: Theoretical Foundations

2.2. Gendered Everyday Life Infrastructure

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Measurement Variable and Data Collection

- General background information, including details such as gender, age, place of residence, employment status, and other relevant factors. 2. Factors such as living arrangements (independent or dependent), time use, education level, income, and other personal circumstances are also considered.

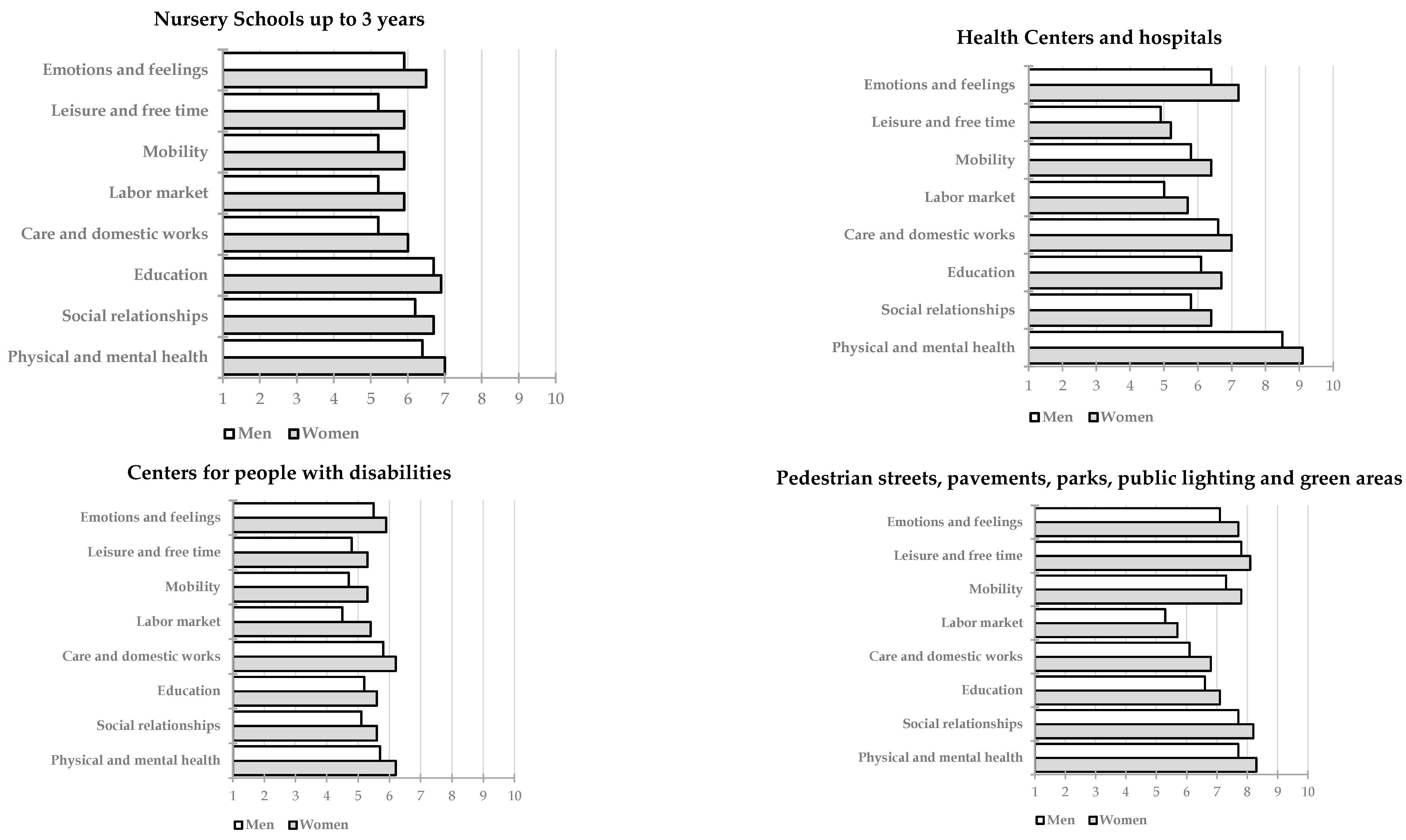

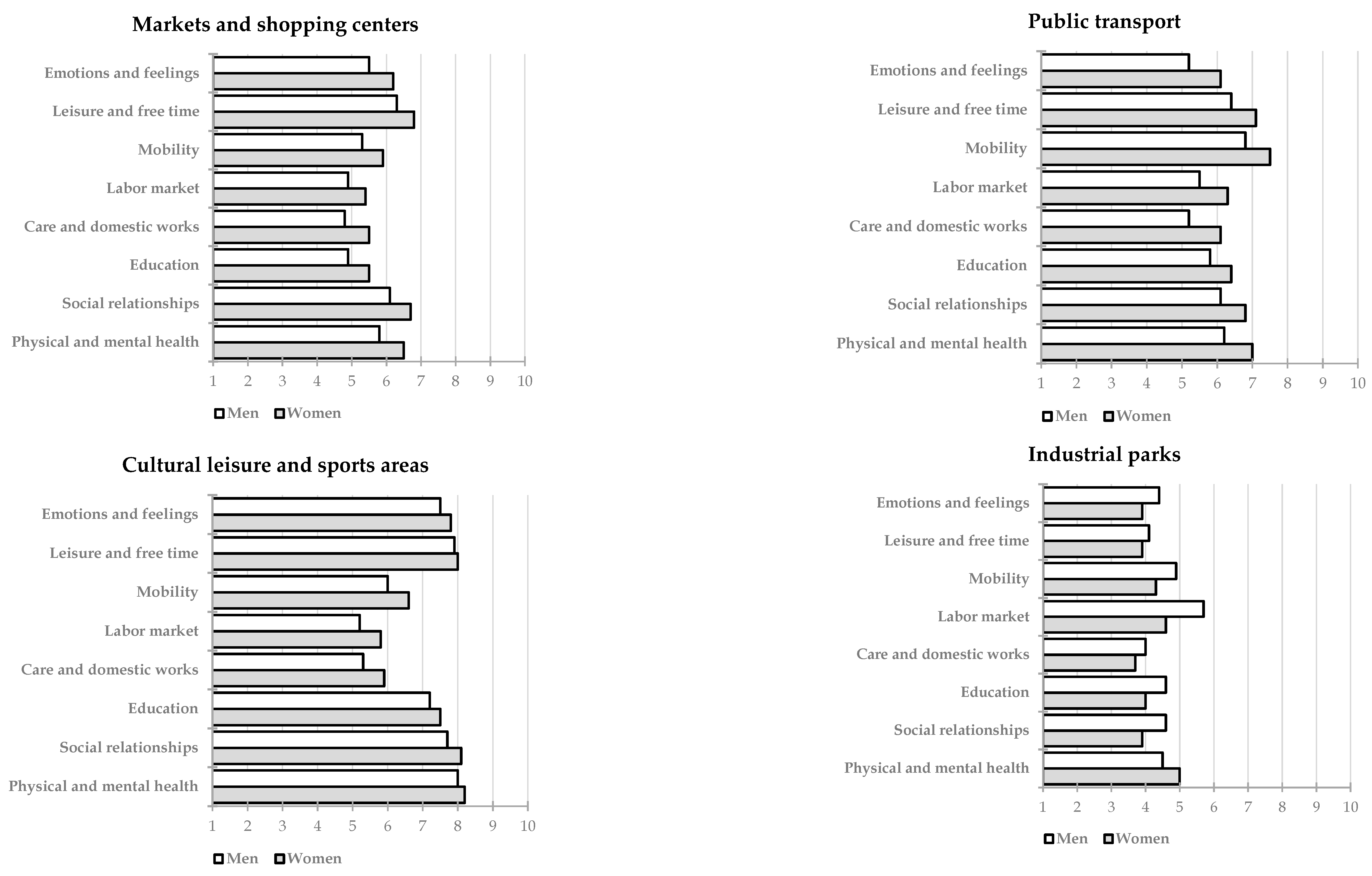

- Perceived accessibility of infrastructure: Participants share their views on how accessible they find the following types of infrastructure: (1) nursery schools for children aged up to three years; (2) health centres and hospitals; (3) pavements, pedestrian paths, street lighting, parks and green spaces; (4) care centres for dependent people (nursing homes, day centres and centres for people with disabilities); (5) markets and shopping centres; (6) public transport for local travel and daily commuting; (7) leisure and cultural facilities (theatres, cinemas and exhibition halls); (8) sports facilities (swimming pools, gyms and fitness centres); (9) industrial parks.

- The Role of Infrastructure in Key Well-Being Capabilities

- 4.

- Subjective well-being. Respondents assess various aspects of subjective well-being, including their overall life satisfaction and how well their current life circumstances align with their personal aspirations.

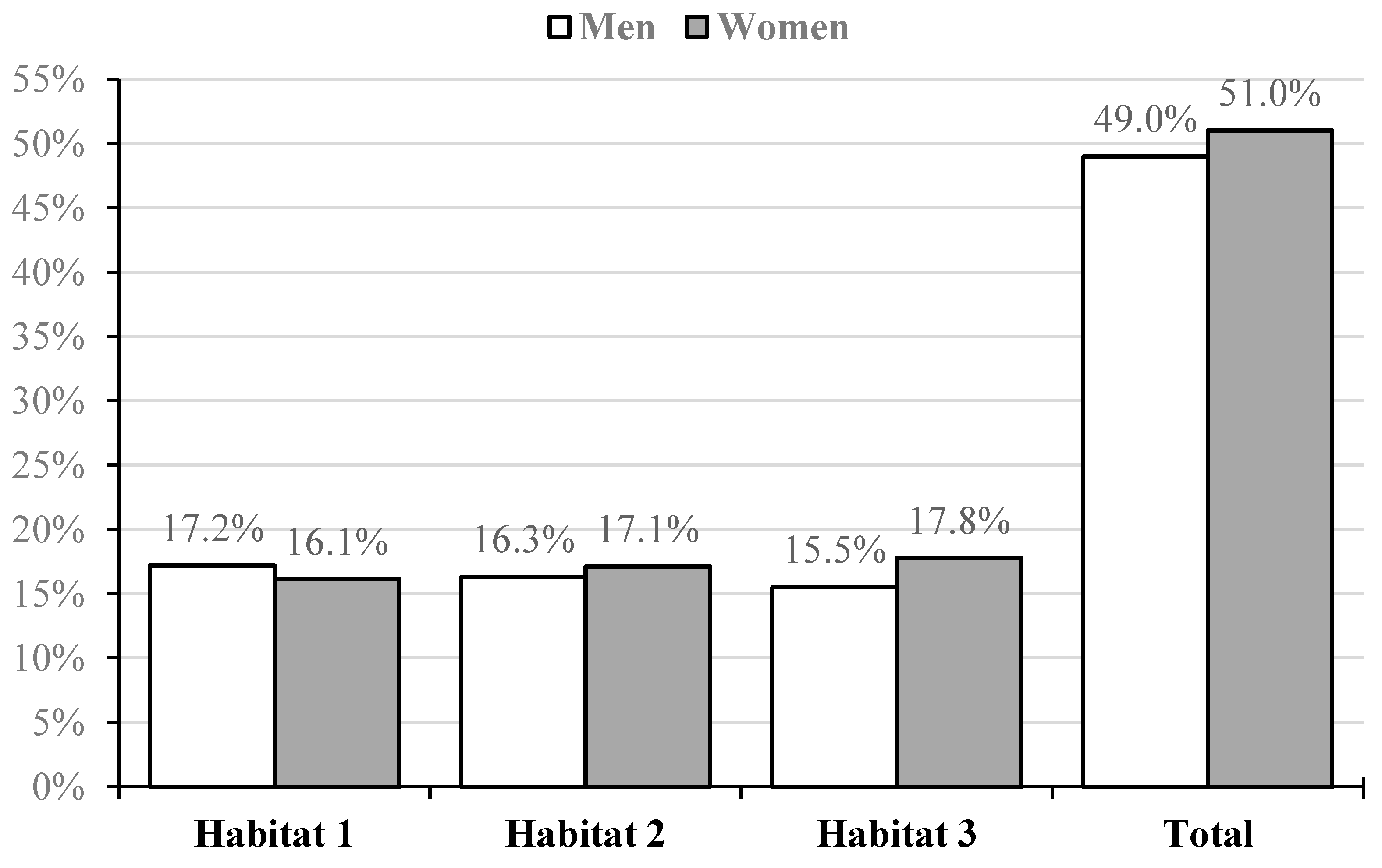

3.2. Demographic Information of the Data

3.3. Methodology. The Well-Being and Infrastructure from a Gender Perspective Index

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNDP. Human Development Report 2009: Overcoming Barriers: Human Mobility and Development; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Available online: http://hdr.undp.org (accessed on 8 January 2024).

- UNDP. Human Development Report 2010: The Real Wealth of Nations: Pathways to Human Development; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2010; Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/human-development-report-2010-complete-english.human-development-report-2010-complete-english (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- OECD. How’s Life? 2013: Measuring Well-Being; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Measuring Well-Being for Development; Global Forum on Development Discussion Paper for Session 3.1; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Economic Policy Making to Pursue Economic Welfare; OECD Report for the G7 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Capability and well-being. In The Quality of Life; Nussbaum, M., Sen, A., Eds.; OUP: Oxford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom; Alfred Knopf: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, M.C. Women and Human Development: The Capabilities Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, M.C. Creating Capabilities; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahneman, D.; Krueger, A.B. Developments in the measurement of subjective well-being. J. Econ. Perspect. 2006, 20, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, M.; Veenhoven, R. Cognitive and affective factors in subjective well-being assessments. J. Happiness Stud. 2010, 11, 17–38. [Google Scholar]

- Comim, F. Capabilities and happiness: Potential synergies. Rev. Soc. Econ. 2005, 63, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, C.; Nikolova, M. Bentham or Aristotle in the development process? An empirical investigation of capabilities and subjective well-being. World Dev. 2015, 68, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muffels, R.; Headey, B. Capabilities and choices: Do they make Sen’se for understanding objective and subjective well-being. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 110, 1159–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón-García, G. Las infraestructuras para la vida cotidiana. Impregnar los presupuestos públicos de la perspectiva de género feminista e interseccional. In Economía, Política y Ciudadanía; Fabra Ultray, J., González, A., Muro, I., Eds.; Los Libros de la Catarata: Madrid, Spain, 2023; pp. 211–227. [Google Scholar]

- Alarcón, G.; Colino, J. La perspectiva de género en los gastos en infraestructuras públicas: Los equipamientos educativos y deportivos en el FEIL. Presup. Gasto Público 2011, 64, 155–178. [Google Scholar]

- Waring, M. Appreciation: Talking to Ailsa. In Feminist Economics and Public Policy: Reflections on the Work and Impact of Ailsa McKay; Campbell, J., Gillespie, M., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2016; pp. 89–96. ISBN 978-1-13-895085-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Poor relatively speaking. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 1983, 35, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, M.C. Capabilities as Fundamental Entitlements: Sen and Social Justice. Fem. Econ. 2003, 9, 33–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, M.C. Creating capabilities: The human development approach and its implementation. Hypatia 2009, 24, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robeyns, I. The Capability Approach: A theoretical survey. J. Hum. Dev. 2005, 6, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.M. Culture and Subjective Well-Being; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. Por qué las sociedades necesitan la felicidad y cuentas nacionales de bienestar? In Ranking de Felicidad en México 2012; Manzanilla, F., Ed.; Universidad Popular Autónoma del Estado de Puebla: Puebla, Mexico, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin, R.A. Bienestar subjetivo y políticas públicas. In Ranking de Felicidad en México 2012; Manzanilla, F., Ed.; Universidad Popular Autónoma del Estado de Puebla: Puebla, Mexico, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Hunter, J. Happiness in everyday life: The uses of experience sampling. J. Happiness Stud. 2003, 4, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, M. The complexity of well-being: A life-satisfaction conception and a domains-of-life approach. In Researching Well-Being in Developing Countries: From Theory to Research; Gough, I., McGregor, A., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; pp. 259–280. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, M. Experienced poverty and income poverty in Mexico: A subjective well-being approach. World Dev. 2008, 36, 1078–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, M. Hacia Una Sociedad con Alta Calidad de Vida: Una Propuesta de Acción. Serie Documentos Estratégicos CIIE-UPAEP, No. 4. 2012. Available online: https://upaep.mx/micrositios/investigacion/CIIE/assets/docs/doc00034.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2024).

- Upasna, J. Subjective well-being by gender. J. Econ. Behav. Stud. 2010, 1, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenhoven, R. Questions on Happiness: Classical Topics Modern Answers Blind Spots. In Subjective Well-Being an Inter-Disciplinary Perspective; Strack, F., Argyle, M., Schwarz, N., Eds.; Pergamon Press: London, UK, 1991; pp. 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Veenhoven, R. Developments in satisfaction research. Soc. Indic. Res. 1996, 37, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addabbo, T. Gender budgeting in the capability approach: From theory to evidence. In Feminist Economics and Public Policy: Reflections on the Work and Impact of Ailsa McKay; Campbell, J., Gillespie, M., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gunluk-Senesen, G. In Search of a Gender Budget with “Actual Allocation of Public Monies”: A Well-being Gender Budget Exercise. In Feminist Economics and Public Policy: Reflections on the Work and Impact of Ailsa McKay; Campbell, J., Gillespie, M., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Arita Watanabe, B.Y. La capacidad y el bienestar subjetivo como dimensiones de estudio de la calidad de vida. Rev. Colomb. De Psicol. 2005, 14, 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Arita Watanabe, B.Y. La calidad de vida en Sinaloa, México:reflexiones en torno a la aplicación del International well-being index y laescala de creencia de capacidad (2002–2012). Hologramática 2018, 27, 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hovi, M.; Laamanen, J.P. Adaptation and loss aversion in the relationship between GDP and subjective well-being. BE J. Econ. Anal. Policy 2021, 21, 863–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elson, D. Gender awareness in modeling structural adjustment. World Dev. 1995, 23, 1851–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón-García, G.; Fernandez-Sabiote, E. Gender, well-being, budgeting and public infrastructures. In Proceedings of the International Conference: Gender Responsive Budgeting: Theory and Practice in Perspective, Vienna, Austria, 6–8 November 2014; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Small, S.F.; van der Meulen Rodgers, Y. The gendered effects of investing in physical and social infrastructure. World Dev. 2023, 171, 106347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarnert, L.V. Migration, congestion and growth. Macroecon. Dyn. 2019, 23, 3035–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarnert, L.V. Population Sorting and Human Capital Accumulation. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 2023, 75, 780–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horelli, L.; Vepsä, K. In search of supportive structures for everyday life. In Women and the Environment; Altman, I., Churchman, A., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 201–226. [Google Scholar]

- Gilroy, R.; Booth, C. Building infrastructure for everyday lives. Eur. Plan. Stud. 1999, 7, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, D. What would a non-sexist city be like? Speculations on housing, urban design, and human work. Signs J. Women Cult. Soc. 1980, 5, 170–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, D. The Grand Domestic Revolution; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Hayden, D. Redesigning the American Dream. The Future of Housing, Work, and Family Life; WW Norton Company: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez de Madariaga, I. Infraestructuras para la vida cotidiana y la calidad de vida. Ciudades 2004, 8, 101–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bofill Levi, A. De la Ciudad Actual a la Ciudad Habitable. 1998. Available online: https://bibliobuscador.uah.es/discovery/fulldisplay?docid=alma991000951979704214&context=L&vid=34UAH_INST:34UAH_VU1&lang=es&adaptor=Local%20Search%20Engine&tab=Everything&query=any,contains,991000951979704214 (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Carpio-Pinedo, J.; De Gregorio, S.; Sánchez de Madariaga, I. Gender mainstreaming in urban planning: The potential of geographic information systems and open data sources. Plan. Theory Pract. 2019, 20, 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez de Madariaga, I. Urbanismo con Perspectiva de Género; Consejería de Economía y Hacienda; Sevilla Instituto Andaluz de la Mujer: Sevilla, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez de Madariaga, I. Urbanismo con Perspectiva de Género; Instituto Andaluz de la Mujer: Sevilla, Spain, 2006; Available online: http://www.juntadeandalucia.es/institutodelamujer/institutodelamujer/ugen/sites/default/files/documentos/98.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2012).

- Sánchez de Madariaga, I.; Novella, I. A new generation of gender mainstreaming in spatial and urban planning under the new international framework of policies for sustainable development. In Gendered Approaches to Spatial Development in Europe; Zibell, B., Damyanovic, D., Sturm, U., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019; pp. 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera, L.; Castellaneta, M. Women and cities. The conquest of urban space. Front. Sociol. 2023, 8, 1125439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bofill Levi, A. Hacia Modelos Alternativos de Ciudad Compatibles con una Sociedad Inclusiva. In Estudios Urbanos, Género y Feminismos. Teorías y Experiencias; Gutiérrez, B., Ciocoletto, A., Eds.; Col·lectiu Punt 6: Barcelona, Spain, 2012; Available online: http://punt6.files.wordpress.com/2011/03/estudiosurbanosgenerofeminismo.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Alarcón-García, G.; Buendía-Azorín, J.D.; Sánchez-de-la-Vega, M.D.M. Infrastructure and Subjective Well-Being from a Gender Perspective. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón-García, G.; Ayala-Gaytan, E. Índice de Bienestar e Infraestructura Desde una Perspectiva de Género, WIGI. La Metodología de Construcción del Índice del Observatorio Fiscal: Análisis de las Políticas Públicas. 2018. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334002240_Indice_de_Bienestar_e_Infraestructura_desde_una_perspectiva_de_Genero_WIGI_La_metodologia_de_construccion_del_Indice?showFulltext=1&linkId=5d129e3292851cf4404c2678 (accessed on 14 December 2021).

| THEORY | CAPABILITY APPROACH | SUBJECTIVE WELL-BEING |

|---|---|---|

| Well-Being Type | Eudaimonic Well-Being | Hedonic Well-Being |

| Well-being Concept | Well-being is associated with the concept of individual autonomy, specifically in relation to the selection of that which is held in high esteem. It is therefore evident that well-being is shaped by the extent to which individuals are able to fulfil their diverse needs and achieve their objectives. For instance, it is imperative to recognise that attaining a certain level of health and education is necessary to ensure a comfortable standard of living and/or a good job. The concept of well-being can be represented by the objective assessment of a society’s capabilities. | Well-being is derived from subjective, frequently self-reported, feelings of happiness, as well as positive and negative emotions and life satisfaction judgements. |

| Operationalisation | The contributions of Nussbaum and Robeyns’ lists of functionings have identified the dimensions of everyday life that contribute to individual well-being. Nevertheless, while these approaches offer significant insights, they do not operationalise these dimensions with specific proposals or applications to measure well-being. | Depending on the focus and data collection method, a range of metrics may be applied. Nevertheless, there is a consensus among scholars that well-being is an individual state of mind and is, therefore, hedonic. Diener et al. [5] are recognised as the pre-eminent exponents of the methodologies employed within this framework. |

| Institutionalisation | The United Nations’ “Human Development Index” (HDI) integrates per capita income with education and health. | Supported by the OECD in its most recent reports [12]. |

| Literature | [1,2,3,4,18,19,20,21,22] | [6,7,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] |

| Variable | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum | Number Obs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1.51 | 0.50 | 1 | 2 | 1502 |

| Age | 50.10 | 17.10 | 18 | 94 | 1502 |

| Education | 4.74 | 1.38 | 1 | 6 | 1499 |

| Subjective Well-being | 7.79 | 1.65 | 1 | 10 | 1501 |

| Labour situation | 4.48 | 1.69 | 1 | 9 | 1501 |

| Income | 4.68 | 1.92 | 1 | 9 | 1343 |

| Variable | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum | Number Obs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective Well-being | 6.9 | 2.1 | 1 | 10 | 1502 |

| Access to nursery schools up to 3 years | 7.11 | 2.90 | 1 | 10 | 1461 |

| Access to health centers and hospitals | 7.56 | 2.34 | 1 | 10 | 1502 |

| Access to centers for people with disabilities | 5.64 | 3.07 | 1 | 10 | 1450 |

| Access to sidewalks and pedestrian paths, street lights and parks and green areas | 7.66 | 2.21 | 1 | 10 | 1502 |

| Access to markets and shopping centers | 7.10 | 2.61 | 1 | 10 | 1500 |

| Access to public transport | 6.47 | 2.99 | 1 | 10 | 1494 |

| Access to cultural leisure and sports areas | 6.86 | 2.47 | 1 | 10 | 1500 |

| Access to industrial parks | 5.72 | 3.00 | 1 | 10 | 1491 |

| Infrastructure | Men | Women | Difference (pp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nursery Schools up to 3 years | 85.98 | 113.51 | 27.53 |

| Health Centers and hospitals | 91.51 | 108.37 | 16.86 |

| Centers for people with dependencies | 86.87 | 113.09 | 26.22 |

| Pedestrian streets, pavements, parks, public lighting and green areas | 90.39 | 109.16 | 18.77 |

| Markets and shopping centers | 85.96 | 113.89 | 27.93 |

| Public transport | 85.95 | 113.89 | 27.94 |

| Cultural leisure and sports areas | 91.46 | 107.81 | 16.35 |

| Industrial parks | 110.68 | 86.64 | −24.04 |

| Average | 91.10 | 108.30 | 17.20 |

| Habitat 1 | |||

| Infrastructure | Men | Women | Difference (pp) |

| Nursery Schools up to 3 years | 132.48 | 170.91 | 38.43 |

| Health Centers and hospitals | 141.86 | 161.12 | 19.26 |

| Centers for people with dependencies | 139.27 | 174.52 | 35.25 |

| Pedestrian streets, pavements, parks, public lighting and green areas | 138.70 | 152.90 | 14.20 |

| Markets and shopping centers | 127.65 | 152.26 | 24.62 |

| Public transport | 121.05 | 141.92 | 20.87 |

| Cultural leisure and sports areas | 141.10 | 148.19 | 7.09 |

| Industrial parks | 199.42 | 131.28 | −68.15 |

| Average | 142.69 | 154.14 | 11.45 |

| Habitat 2 | |||

| Infrastructure | Men | Women | Difference (pp) |

| Nursery Schools up to 3 years | 44.49 | 72.81 | 28.32 |

| Health Centers and hospitals | 44.73 | 64.70 | 19.97 |

| Centers for people with dependencies | 39.04 | 71.78 | 32.74 |

| Pedestrian streets, pavements, parks, public lighting and green areas | 38.69 | 67.99 | 29.30 |

| Markets and shopping centers | 35.92 | 70.12 | 34.20 |

| Public transport | 34.27 | 76.86 | 42.59 |

| Cultural leisure and sports areas | 41.26 | 66.90 | 25.64 |

| Industrial parks | 53.13 | 57.49 | 4.36 |

| Average | 41.44 | 68.58 | 27.14 |

| Habitat 3 | |||

| Infrastructure | Men | Women | Difference (pp) |

| Nursery Schools up to 3 years | 89.53 | 121.31 | 31.78 |

| Health Centers and hospitals | 107.34 | 123.57 | 16.23 |

| Centers for people with dependencies | 96.86 | 119.05 | 22.19 |

| Pedestrian streets, pavements, parks, public lighting and green areas | 104.87 | 127.76 | 22.88 |

| Markets and shopping centers | 103.56 | 141.23 | 37.68 |

| Public transport | 115.06 | 140.98 | 25.92 |

| Cultural leisure and sports areas | 104.76 | 128.36 | 23.60 |

| Industrial parks | 106.50 | 96.07 | −10.43 |

| Average | 103.56 | 124.79 | 21.23 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alarcón-García, G.; Buendía-Azorín, J.D.; Sánchez-de-la-Vega, M.d.M. Bridging the Gap: The Gendered Impact of Infrastructure on Well-Being Through Capability and Subjective Well-Being Approaches. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9110459

Alarcón-García G, Buendía-Azorín JD, Sánchez-de-la-Vega MdM. Bridging the Gap: The Gendered Impact of Infrastructure on Well-Being Through Capability and Subjective Well-Being Approaches. Urban Science. 2025; 9(11):459. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9110459

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlarcón-García, Gloria, José Daniel Buendía-Azorín, and María del Mar Sánchez-de-la-Vega. 2025. "Bridging the Gap: The Gendered Impact of Infrastructure on Well-Being Through Capability and Subjective Well-Being Approaches" Urban Science 9, no. 11: 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9110459

APA StyleAlarcón-García, G., Buendía-Azorín, J. D., & Sánchez-de-la-Vega, M. d. M. (2025). Bridging the Gap: The Gendered Impact of Infrastructure on Well-Being Through Capability and Subjective Well-Being Approaches. Urban Science, 9(11), 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9110459