Abstract

This study offers, by an empirical analysis, another perspective on post-socialist development, highlighting the role of the urban–rural interface in regional dynamics. The current literature on the relationships between both issues is not too rich and our paper analyzes the relationships between core cities, their peri-urban areas, and their regions, through a comparative overview of their growth over the last three decades. Romania, as a special case study for a contradictory transition, due to the great step from a drastic dictatorial regime to a democracy and a market economy, is a good example to test these complex relationships. Considering the new development trend at the urban–rural interfaces, our key idea was to depict their contribution to regional development (NUTS 3) compared to city cores. The second question was how this differentiated contribution can be measured, using the simplest tool. The starting point was the fact that population dynamics reflect all changes in the city core and at the urban–rural interface, and less so at a regional level. Consequently, we selected the dynamics of the number of inhabitants for the first two, as well as the dynamics of GDP per capita at the regional level. We found higher and significant correlations between GDP per capita and urban–rural interfaces, but no significant correlations in the case of city cores. Our conclusion is that, in the transition period, the dynamics of urban–rural interfaces influenced more regional development dynamics, than those of city cores. This means that urban–rural interfaces amplify the development coming from cities, adding their own contribution and then dissipating it regionally. Future research should identify what the urban–rural interface offers to regions, in addition to the city core.

1. Introduction

Forecasts regarding the growth of the world’s urban population show that it will reach 68 per cent of the total world population by 2050 [1], which means that urban–rural interfaces will continue to develop at least at the same rate as urban population, both spatially and demographically. The rural exodus that has mostly characterized the last century has determined the growth of urban population. The latter, becoming more demanding with the urban conditions influencing quality of life, moved to suburban and peri-urban areas [2]. Despite the geographical reality, the world literature continues to approach the city and village separately, without taking into account the relations between them; the urban–rural relationship is still poorly described [3] or insufficiently addressed, at least at the level of the urban–rural interface [4].

The city, under human pressure and the impact of increasing population demands, needs space and resources and its most convenient partner is the nearby rural area [5]. The rural area, on the other hand, is in a big dilemma regarding its choices. On the one hand, it needs financial resources, investments, and infrastructure improvement, including housing; on the other hand (although less often acknowledged), excessive development may lead to negative effects on the quality of life [6], including the loss of its identity [7]. Because the modernization of services and infrastructure is more attractive than preserving local specificity, rural areas usually prefer the first strategy, transforming themselves almost completely [8].

Most often, studies are limited only to strict analyses of the relations between the city itself (core city) and the surrounding rural area, revealing, on the one hand, the multitude of mutual flows of population, resources, material goods, services, and information [9] and, on the other hand, illustrating the environmental interactions between urban and rural areas [10]. Examining the complex relationship of peri-urban, urban, and agricultural rural areas, Brinkley [11] makes an interesting analogy between coral reef roughness and the configuration of city perimeters, showing the difference in the process of urban–rural integration of high roughness. In parallel with the development and implementation of the smart city concept, there are some concerns drawing attention to the fact that this type of city cannot function in isolation from its environment, requiring the almost simultaneous development of an intelligent urban–rural interface [12].

The key question in our research is the following: is it possible to analyze and identify the role of the urban–rural interface in regional development, at an NUTS3 level, using only two relevant indicators? The proposed indicators are the population dynamics of the core city and the urban–rural interface, on the one hand, and the GDP/inhabitant dynamics at the regional level, on the other hand. Our approach, relatively simple and empirical, falls within what Wu et al. [13] demonstrated, by defining the rural–urban interface, as an interesting analysis framework for the interaction between urban and regional economies, as well as the relationship between environmental and resource economies. The NUTS (Nomenclature of territorial units for statistics) classification is used by Eurostat as a hierarchical system for dividing the European territory, with NUTS3 referring to sub-regional units, which have administrative status in some countries—for example, Italian provinces.

The spatial projection of the city–countryside relationship can be found in different concepts, such as the urban–rural interface, suburban, peri-urban, urban sprawl, area of influence, etc. [14,15]. All these spatially designed concepts intersect epistemologically, without totally overlapping, while expressing, in different forms, the accelerated dynamics of this highly complex space [16]. At the same time, it is demonstrated that an urban–rural continuum can be defined between the city and its surrounding area [17,18], from the viewpoint of decreasing intensity of flows, landscape fragmentation, and as a space where segments, such as the urban–rural interface, can be individualized [18].

An important aspect of analyzing the urban–rural interface brings into debate the relationship between the concepts of urbanity and rurality [19], which shows the complex behaviors of communities and their inhabitants [20], in addition to the complex structure and functionality of this interface. For example, “a place-oriented approach” is defined in the study of urban–rural relations, showing the importance of individual decisions made by those who are emotionally connected to the place [20].

Hiner [21], as a synthesis of the above, considers that the rural–urban interface has two categories of elements, as follows: the first represents the place with all its characteristics, while the second is the social–political environment. In addition to these, the new cleavage that appeared between urban and rural, in relation to the tolerance towards the progressive values promoted by the city [22], calls for a permanent update of urban and regional development policies.

The extremely diverse approaches to the extent, characteristics, and dynamics of urban–rural interfaces seem to have less importance than the impact that the latter can have on intra-regional development and governance, implicitly on rural economies and societies [23]. Noting that there are few studies focused on the rural hinterland of small towns in relation to that of large cities, Bowen and Webber [24] reveal the former’s disregard in regional policies, which leads to the marginalization of rural areas and their disconnection from development processes.

In cohesive regional development policies, place identity plays an important role, which is stronger at the periphery of the urban–rural interface, in rural areas, as shown by the study undertaken by Belanche et al. [25]. This study focuses on the comparison of rural and urban dwellers regarding place attachment, but also provides an important argument for in-depth research on the interface between the two environments. Such an analysis could lead to the detection of the mechanisms of the loss of local identity, including their perennial values [26].

An interesting distinction is made by Pryor [27] regarding the use of the terms ‘urban–rural fringe’ and ‘rural–urban fringe’, in relation to the average house density. In the first case, housing density is above average, while in the second case, it is below average [28]. Vaz and Nijkamp [29] noted that “the impacts of the rate of growth of different cities in the same region, and the resulting impacts on urban sprawl given their regional interactions, have not yet been explored. Land-use comparison at multiple points in time by means of regional land use inventories could enable us to make a better assessment of these urban interactions”. Other authors go further in search of the city’s identity and its relationships with the environment throughout history, resorting to archaeological methods [30].

After 2000, numerous scientific works developed the concept of the smart city, trying to more clearly define the compatibility between the high rates of urbanization and the associated environmental challenges [31]. At the same time, some researchers have noticed the excessive attention paid to the smart city, neglecting their supporting space, concluding that its development requires an equally intelligent urban–rural interface. At this stage, it is important to stress that, from an ecological standpoint, urban fringes [32] and, by extension, the urban–rural interference area are ecotone areas and are, thus, responsible for the dynamics and even productivity of the two systems they separate [33], hence their role as a supporting space for the city. The integrated analysis of the smart development of the city and its urban–rural interface allows for the subsequent definition of the main drivers for the diffusion of the new type of development at the regional level [12].

In the context of a complex structure of these urban–rural interfaces, we also took into consideration small towns located in peri-urban areas, revealing, where appropriate, their rapid growth and gradual integration into metropolitan areas [34]. After 2000 and the accession of Romania to the European Union, the generalized rural–urban exodus from the communist period, which continued in the first part of the transition to a market economy, was replaced by the opposite phenomenon (an urban–rural shift), noticed earlier in developed countries. This change was to the economic benefit of rural areas in the hinterland of large and medium-sized cities, which took advantage of the easy access to urban services [35] and the relocation of some urban production or logistic activities [36]. For a stronger cohesion between cities and the region, urban–rural interfaces have a significant role in accelerating the mitigation of territorial imbalances, as Korcelli-Olejniczak [37] emphasized, by analyzing the complexity of relations between the city and region, proposing the concept of an “urban–rural region”.

2. Materials and Methods

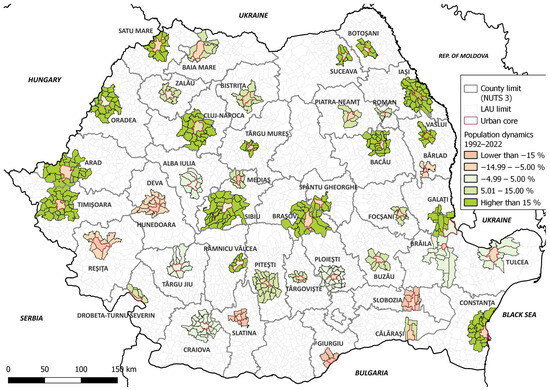

Romania is located in Eastern Europe, at the eastern border of the European Union. Its administrative structure includes 41 counties and Bucharest, the capital city (Figure 1). The territorial development policy in the communist period was based on the extensive industrialization and control of the settlement system [38]. The housing policies, lack of private property and land market, as well as the centralized planning system are elements that explain why, during the communist period, there was no real process of suburbanization, as witnessed in all former socialist countries [39,40,41]. The peculiarities of Romania emerge from the impact of certain legislative measures adopted during the Communist era, as follows:

Figure 1.

Romanian regions (NUTS 3) and their population dynamics (1992–2022).

- The restrictions imposed on immigration in cities with over 100,000 inhabitants;

- The definition of smaller buildable perimeters than actual built-up areas, through the law on systematization (spatial planning);

- The obligation of higher education graduates to carry out internships in other settlements than the big cities;

- Priority given to some mega-projects over the definition and functionality of urban–rural interfaces, which would have reduced the city–countryside discontinuities.

These peculiarities make Romania an interesting territory for analyzing the urban–rural interface and justify its selection as a case study. At the same time, these inherited considerations from the communist period, added to the late reaction of local authorities in terms of urban planning in the years after the fall of communism, explain why uncontrolled suburbanization in Romania has become a feature of the urban–rural landscape [42].

Despite the urban development and regeneration processes in big cities, the growth was stronger at the level of urban–rural interfaces. The new dimensions of suburbanization and the revitalization of nearby peri-urban villages were the effect of the shrinking of large cities and a relatively sudden change in the direction of migration from rural–urban to urban–rural [43]. Under these conditions, even if the big cities remained the main engines of urban development, the spectacular growth of urban–rural interfaces should be highlighted [44]—see Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Urban cores and population dynamics, by their urban–rural interfaces (1992–2022).

The impact of this growth on regional development is of great interest; because of the transition to a market economy, territorial gaps at the regional level have increased a lot, compared to the communist period. For example, the GDP per inhabitant ratio between the wealthiest and poorest region was about 1.8 in 1994 (Bucharest and Giurgiu), increasing to 4.5 in 2020 (Bucharest and Olt). In other words, throughout the transition period, regional development policies were aimed at increasing the macro-regional role of competitive regions acting as development engines, but less focused on achieving regional convergence from an economic, infrastructural, social, and cultural point of view.

Our main working hypotheses are as follows: (a) regional GDP growth is determined more so by the process of population concentration in urban centers than exurbanization; (b) the dynamics of population at the urban–rural interface certifies its role as a relay in amplifying urban impulses to the entire region; and (c) the more pronounced dynamics of population at the urban–rural interface justifies the phrasing of distinct policies, in the effort to reduce intra-regional gaps.

The inconsistency of data and information for a comparative analysis of the potential impact of urban–rural interfaces on various regions led us to resort to the two indicators mentioned in the previous section—the dynamics of the number of inhabitants of the city and of the urban–rural interface, respectively, and the GDP per inhabitant for each region. All these data, provided by the National Institute of Statistics, have been processed and correlated with other data and information provided by some local statistics and specialized publications.

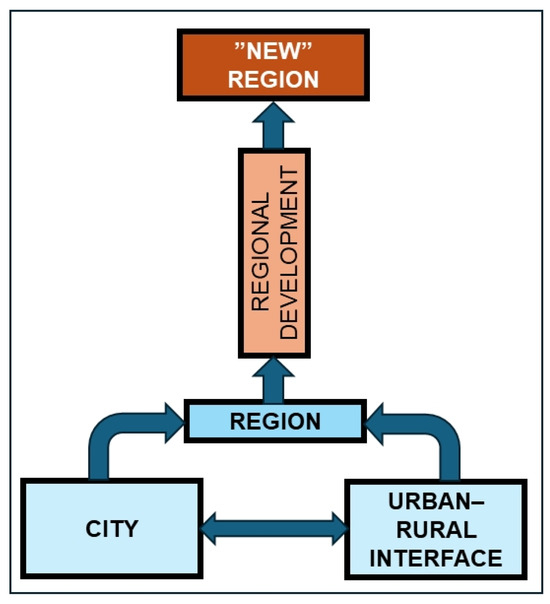

We have chosen to study the dynamics of the number of inhabitants, since, if the population of a city and the urban–rural interface is continuously increasing, this means that the two entities are attractive and their development is reflected in the influence and development of the region. The territorial extension of regions is compatible with the impact that cities and their urban–rural interface can have, illustrating the relevance of analyzing the cause–effect relationship between the dynamics of the two entities (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

How the city and the urban–rural interface change the initial region.

To demonstrate the impact of urban–rural interaction at the regional level, we selected all the cities with over 50,000 inhabitants, considered to be capable of shaping such a functional interface, and analyzed them in the context of the regions of the mentioned level. As mentioned by Rodríguez-Pose ([45], pp. 1025–1026), These nodes of human activity tend to coincide with relatively large cities or with systems of medium-sized cities in close geographical proximity, that articulate the economic and social developments of suburban, periurban, and rural hinterlands. This interaction between an urban core and its semi-urban and rural hinterland is the essence of the city-region.

Considering the disruptive effect that the inclusion of Bucharest and its urban–rural interface, represented by the Ilfov County (both NUTS 3), introduces into such an analysis, we resorted to their elimination. At the same time, we found out that, among all regions of the country, the Harghita and Teleorman counties do not have any cities with more than 50,000 inhabitants and their inclusion in the analysis of GDP per inhabitant dynamics would not have made sense. Therefore, out of the 42 regions, 38 were analyzed, all having at least one medium-sized city, capable of having an urban–rural interface that is significant in detecting its impact at a regional level (see Figure 2). Except for three regions (Hunedoara, Sibiu, and Vaslui), all others have only one large or medium-sized city with over 50,000 inhabitants.

The urban–rural interface of each large and medium-sized city was determined by merging all LAU-type administrative units in a direct relationship with the respective cities that marked population increases. LAU refers to local administrative units, usually the lowest level of local administration—the municipalities and commune—in a European country. In the process of individualizing the urban–rural interface, the value of the rural development index, determined by D. Sandu [46], recorded by the communes adjacent to the selected cities, was also considered. We must mention that the process of rural depopulation in all regions of Romania was very accentuated after the collapse of the communist system, except for communes near large cities and some medium-sized cities.

To capture the general dynamics of the number of inhabitants of the urban–rural interface, and of GDP per inhabitant, we selected population data from the National Institute of Statistics online database (for the 1st of January 1992, 2002, 2022), considered significant for the analyzed period (1992–2022), as well as available regional GDP data. Regarding the latter, in two situations we resorted to the use of other reference years for GDP—1994 instead of 1992 and 2020 instead of 2022.

In measuring the impact of the urban–rural interface on the region, we used the Pearson correlation coefficient to test the existence of a relationship between population growth within the urban–rural interface and the level of regional development. The large differences between the values of indicators made us use logarithmic values, which are more relevant for graphical illustration. We have associated empirical analyses and observations on current differentiations between the uneven growth of cities and their urban–rural interfaces to the collected and processed data.

3. Results

3.1. The Ratio between City Growth and Urban–Rural Interface Growth

The comparative analysis of the population dynamics of cities and their urban–rural interfaces highlights some relevant findings, which can be observed in Table 1. Between the two periods, a major difference is observed, closely linked to the dominant socio-economic development processes of the rapid transition period from a planned economy to a market economy, characterized by new conditions generated by new reforms, but also to changes in the population’s behavior.

Table 1.

Ratio between city core and urban–rural interface population.

The ratio between the population of the polarizing city and the population of urban–rural interfaces illustrates a clear stability in the first decade of transition, its values oscillating in 2002 around those recorded at the beginning of transition. The big change takes place after Romania’s integration into the Euro-Atlantic structures, when the effects of the adopted reforms can be seen in the Romanian economy, as the restrictions on the movement of people and goods at a European level were eliminated and foreign capital, alongside domestic capital, was invested at a national level, but differentiated within the territory. This differentiation emerges from the values recorded using the analyzed ratio between the years 2002 and 2022. While this second period covers two decades, the change is fundamental and in the opposite direction to that of the previous period.

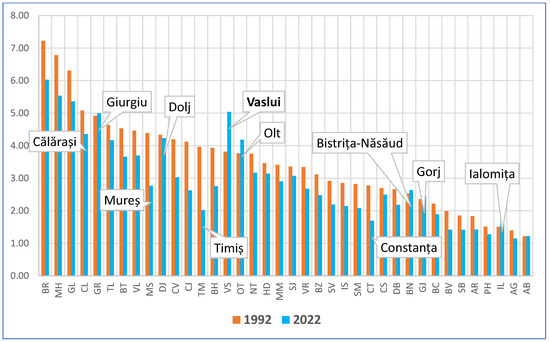

Synthetically, the different dynamics of cities in relation to their urban–rural interface can be observed by analyzing the values registered in 1992 and 2022 (Figure 4). In relation to the values ranked in 1992, it is found that the dynamics of this ratio in 2022 are extremely different, against the general background of a stronger growth in the number of inhabitants at the urban–rural interfaces, compared to their respective cities. This means that exurbanization was and is present as an important feature of settlement systems centered on large and medium-sized cities.

Figure 4.

Variation of the ratio between cities and urban–rural interface population (1992 and 2022).

Overall, there are seven positive anomalies defined by the cases where the population dynamics of the cities exceeded that of the urban–rural interfaces at a regional level, with only four cases where the ratio registers much lower values in 2022 than in 1992.

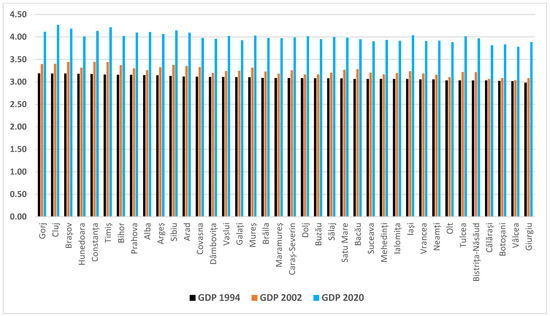

3.2. National GDP Dynamics Maintaining the Regional Hierarchy

The dynamics of GDP per inhabitant showed a significant increase, especially since 2007, after the accession of Romania to the European Union (see Table 2). The growth was exponential, with a strong disruption generated by the economic–financial crisis from 2010 to 2012, with an extension until 2016, and another smaller disruption generated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The positive trajectory is also reflected in the dynamics of GDP per capita at the regional level. For the latter, we selected data close to the main population censuses, in 1994, 2002, and 2020, which we found relevant for testing our hypotheses, regarding the possible impact of urban–rural interfaces on regional development.

Table 2.

Dynamics of GDP per capita in Romania (1990–2022).

Since the differences between the GDP per capita values in the analyzed interval are considerable, we used their logarithm for their graphical representation (Figure 5). In relation to the hierarchy in 1994, we observed the changes in the hierarchies and intensity of the development of each region.

Figure 5.

GDP (log) variation by regions: 1994, 2002, and 2020.

It can be observed that, in 1994, there were no clear differences between the regions. In 2002, the regional distribution of values showcases the regular tendency of some regions to be clearly differentiated from others. The comparison of the general distribution between the years 2002 and 2022 shows that, overall, the GDP growth was generalized and the gaps between regions observed in 2002 were maintained.

3.3. The Differential Correlation of GDP per Capita between Cities and Urban–Rural Interfaces, at the Regional Level

The analysis of these correlations in these three important moments throughout the post-socialist period reveals a differentiated increase in values starting from 1992. Thus, the value of Pearson’s coefficient is lower for the correlation between GDP per capita and the population of cities, compared to the one between GDP per capita and the population of urban–rural interfaces (Table 3).

Table 3.

Pearson’s correlation between GDP per capita with city core and urban–rural interface population.

To demonstrate the differences, we selected only the values from the first and the latest available years. Thus, for the evolution of the correlation coefficient between GDP per capita and the number of inhabitants of the city, we selected only the years 1992 and 2022, revealing some increases in this connection, which are not strong in terms of statistical significance (R2), however.

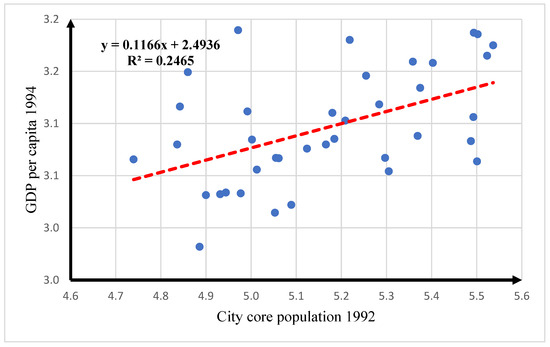

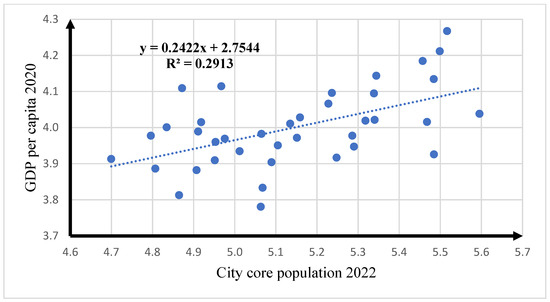

As shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7, the R2 values are close, but both have a low statistical significance, which means that the growth of GDP per capita depended very little on the growth of the population of cities, but probably stronger on their economy.

Figure 6.

Correlation between GDP per capita (1994) and city core population (1992), by regions.

Figure 7.

Correlation between GDP per capita (2020) and city core population (2022), by regions.

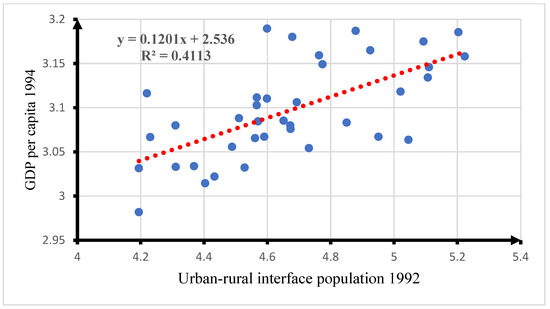

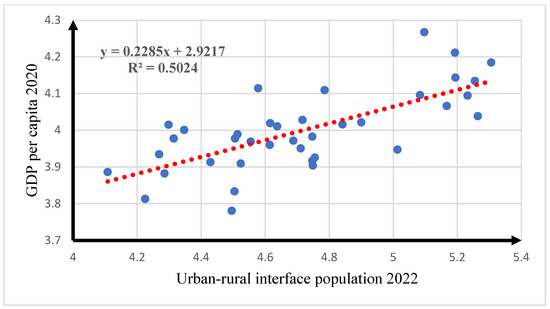

Following the same logic of the approach, we wanted to observe if this relationship is maintained at the same level of statistical significance between the number of inhabitants at the urban–rural interface and the level of GDP per capita, for the same reference years (Figure 8 and Figure 9).

Figure 8.

Correlation between GDP per capita (1994) and urban–rural interface population (1992), by regions.

Figure 9.

Correlation between GDP per capita (2020) and urban–rural interface population (2022), by regions.

Two findings are noted, as follows: (a) the level of correlation is different, in terms of significance, for the two moments analyzed, respectively, 1992 (1994) and 2022 (2020); and (b) there is a stronger statistical significance between the urban–rural interface and GDP per capita at the regional level, than in the case of the possible relationship with the core city.

4. Discussion

The obtained results allow for a detailed analysis of the relationship between urban and regional development in the post-socialist development of a country like Romania. The result of the balanced development policy during the socialist period revealed a relatively stable regional hierarchy of the territorial distribution of GDP per capita. Three decades after the collapse of the communist regime, there is a rearrangement of the territorial economy, in relation to the natural potential for regional development.

4.1. An Overview on the Comparative Ratio between the Population of City Core and Urban–Rural Interface at the Regional Level

The post-socialist evolution determined a change in the meaning of migration from rural–urban to urban–rural, accompanied by the resumption of economic growth in cities and their surroundings [42]. This led us to the idea that there is also a different dynamic of the ratio between the population of the city and the population of its urban–rural interface.

Analyzing this ratio at the level of regions with at least one city of over 50,000 inhabitants, different values can be distinguished in the transition period prior to Romania’s accession to the Euro-Atlantic structures (1990–2002), compared to the post-socialist development period (2002–2022). The inertia of previous urban growth processes based on rural input continued in the first decade, resulting in a continuation of population growth in large and medium-sized cities, at the expense of peri-urban areas. Thus, in 2002, in 63% of the regions, cities in the mentioned categories continued to grow compared to their urban–rural interfaces. The highest values were found in the regions of Cluj, Bihor, Botoșani, Vâlcea, and Galați, and the lowest values were found in some highly developed urban areas such as Brașov and Constanța, which have been declared National Growth Poles during the 2007–2013 EU programming period and have benefitted from a larger allocation of structural funds within their metropolitan area, in comparison to other cities.

The period from 2002 to 2022 was marked by a drastic reduction in the ratio between the core city and its urban–rural interface in almost all regions of the country, but especially in those regions where large cities are predominant (Cluj, Bihor, Timiș, Galați, Botoșani, and Mureș). The regions that witnessed an increase in the ratio between the city’s population and the urban–rural interface are among the poorest in the country (Vaslui, Ialomița, Bistrița-Năsăud, and Olt). In the case of the Vaslui region, the cities Vaslui (first and foremost) and Bârlad had a spectacular increase in their population through external migration (population from the Republic of Moldova, who obtained dual citizenship and preferred moving to these two cities due to the lower real estate costs).

4.2. Testing the Working Hypotheses

Our study answered a question related to the possibility that, by only analyzing the population dynamics in the urban–rural interface of large and medium-sized cities, we can make a direct connection with the dynamics of territorial development processes, measured only by GDP per capita. We answer this question by testing the working hypotheses, phrased in Section 2.

H1.

Regional GDP Growth Is Determined More by the Process of Population Concentration in Urban Centers than by Exurbanization

The comparative analysis of correlations between the population of cities generating active urban–rural interfaces and GDP per capita at the regional level shows that their statistical significance is very low, which leads us to the idea that this indicator is not relevant for explaining regional differences. Even if R2 increases slightly in the analyzed interval, from 0.2466 (1992/1994) to 0.2913 (2022/2020), its values do not place it among the direct drivers of the growth of GDP per capita. Certainly, in this case, economic indicators better highlight the contribution of large and medium-sized cities to the regional GDP.

In the period from 1990 to 2002, cities continued to concentrate part of internal rural–urban migrations, but their differentiated evolution did not influence the radical change of the hierarchical configuration of GDP per capita. However, the decrease in the ratio between their population and the population of urban–rural interfaces in the following period emphasized the increase in GDP per capita, widening regional gaps.

The correlations between the population of urban–rural interfaces and GDP per capita did not have significant values for the years 1992/1994 and 2002. However, in the last reference year (2022/2020), the correlation was significant, with an R2 of 0.502. This means that there is a much stronger relationship between population dynamics at urban–rural interfaces and GDP per capita growth than the one generated by the concentration of population in generating cities. At the same time, this finding confirms the fact that, unlike other suburbanization processes in Eastern Europe [47], this process was delayed in Romania by at least a decade. Therefore, in a nutshell, the first hypothesis is not verified.

H2.

The Population Dynamics in the Urban–Rural Interface Certify Its Role as a Relay in the Amplification of Urban Impulses to the Entire Region

Given that we globally accept a certain relation between the urban–rural interface and regional development, as measured by GDP per capita, and that this interface has developed progressively as the city has delocalized some of its activities, we can anticipate that this has the role of amplifying the development from big/medium cities to small ones, especially to the rural areas and then at the level of the entire region [48]. Our case studies, previously carried out in communes from urban–rural interfaces, confirm their role as relays in the diffusion of services and goods from the city to the periphery of regions [36]. Thus, accessibility from the rural areas to a job in the settlements of this interface is preferable to some offered by the city core. This is the case of settlements in the urban–rural interface belonging to large cities such as Timișora (Giarmata) or Cluj-Napoca (Florești), which experienced a spectacular increase in the number of inhabitants, but also a special economic development. Most of the labor force in these communes prefers to work in the nearby city, which offers them more consistent wages. The deficit in the local economy is filled by the surplus of rural areas. The conclusion is that this transitional space acts as a relay in transmitting “development” to the regional peripheries, confirming our initial hypothesis.

H3.

The More Pronounced Dynamics of the Population in the Urban–Rural Interface Justifies the Definition of Distinct Policies in the Effort to Reduce Regional Gaps

Disregarded in territorial development policies for a long time or treated as an annex to the development of the city, providing it with space for expansion and a “bedroom” for the urban workforce, the urban–rural interface deserves to be treated as a territorial system in the process of consolidating its identity. Emphasizing its role in regional development cannot be a chaotic process, but one that should have adequate planning, ensuring the necessary levers to reduce intra-regional gaps and establish a real spatial justice for the peripheries, which are usually neglected in the development processes of each region.

As part of a whole, regional development policies pay special attention to metropolitan areas, including the urban–rural interface [49]. Regarding the flows generated by the city and their concentration in certain points within the territory, the urban–rural interface should benefit from distinct policies. These policies must address some issues concerning the original identity of places, fragmentarily preserved until now, creating a specific identity for the urban–rural interface.

For the current and future research on these issues, emphasis could be placed on providing answers for the following two key questions: does the urban–rural interface make a greater contribution to regional development than the city that generates it? If so, what does the urban–rural interface offer, in addition to the city core?

5. Conclusions

The human and economic potential of the urban–rural interface, which depends largely on the urban center around which it takes shape and the various resources used by it, contributes to the dimensioning of territorial flows at the regional level. Our study, starting from the complexity of relations between this space and the urban and regional ones, demonstrates that there is a relationship between the population dynamics of urban–rural interfaces and the dynamics of GDP per capita, as the most convenient indicator of regional development.

A country in transition from a centralized to a market economy, such as Romania, offers a framework for the correlative analysis of the dynamics of these simple indicators, while also highlighting several particularities for post-communist development, outlined in the following two stages: one of deep reforms and the other focused on consolidating the market economy.

The population dynamics of the urban–rural interface are connected to the population dynamics of the polarizing (core) city. In the first period, the city had an inertial course, with a growing population, determined by the continuation of rural–urban migration from the communist period, while the urban–rural interface underwent stagnation or slight growth. In the second period, with the restructuring of urban economies, a phenomenon of shrinking cities can be observed, while the urban–rural interface registers an almost explosive growth. All this is evident from the analysis of the ratio between the city population and the urban–rural interface in the two periods (1992/2002 and 2002/2022).

The correlations between the population of cities in the analyzed periods and the recorded values of GDP per capita at the regional level are insignificant. However, the correlation between the population of urban–rural interfaces and GDP per capita, at the end of the analyzed interval, has a high degree of significance. As a result, regional development seems to be more strongly related to the process of exurbanization than to the concentration of population in large and medium-sized cities.

Considering the role that the urban–rural interface has in the process of development diffusion to rural areas, we suggest that, in correlation with urban and regional development policies, this area deserves to have distinct policies that facilitate the fulfillment of its relay role in the process of mitigating intra-regional discrepancies.

This study has certain limits related to the reductionist approach of complex relationships, but offers the possibility to continue the research by adding other indicators considering the impact that urban–rural interfaces could have in the process of sustainable regional development. These indicators could illustrate territorial dynamics related to economic factors (employment rate), socio-demography (population decline and ageing), land use changes (spatial extension of built-up areas), or infrastructure development.

To our knowledge, this is the first study which aims to distinguish between the role of the city and that of its urban–rural interface in regional development, using only two essential indicators (population dynamics and GDP per capita). We strongly believe that our results should be compared to those in other post-socialist countries and consider extending our research with colleagues from other Central-Eastern European countries, in order to validate these results. Consequently, this study opens new research avenues regarding possible comparative analyses considering other post-socialist countries, which could aid in the development of tailored policies considering the common challenges faced by Central-Eastern European countries.

For an unprecedented period, one of transition from the effects of communist ideology on space structuring to a capitalist development through massive processes of privatization and economic restructuring, we appreciate that the comparative analysis of the dynamics of the relationship between urban shrinking and exurbanization, on the one hand, and the evolution of GDP per capita at the regional level, on the other hand, can be encouraging for the refinement of territorial development policies in general.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.I., R.-M.C. and A.-I.P.; methodology, I.I.; software, I.I. and R.-M.C.; validation, I.I., R.-M.C. and A.-I.P.; formal analysis, I.I.; investigation, I.I.; resources, I.I. and R.-M.C.; data curation, I.I. and R.-M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, I.I., R.-M.C. and A.-I.P.; writing—review and editing, I.I., R.-M.C. and A.-I.P.; visualization, I.I. and R.-M.C.; supervision, I.I.; project administration, I.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available data were analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments which aided us in improving this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects 2018: Highlights; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Giménez García, R.; García Marín, R.; Serrano Martínez, J.; Pulido Fernández, M. Peri-urban Dynamics in Murcia Region (SE Spain): The Successful Case of the Altorreal Complex. Urban Sci. 2018, 2, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baffoe, G. Rural-urban studies: A macro analyses of the scholarship terrain. Habitat Int. 2020, 98, 102156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N. Geographical articulations of rurality at the rural-urban interface. Geogr. Compass 2023, 17, e12721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, T. The continuing urban-rural population movement in Britain: Trends, patterns, significance. Espace Pop. Soc. 2001, 19, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oueslati, W.; Alvanides, S.; Garrod, G. Determinants of urban sprawl in European cities. Urban Stud. 2015, 52, 1594–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janečková Molnárová, K.; Skřivanová, Z.; Kalivoda, O.; Sklenička, P. Rural identity and landscape aesthetics in exurbia: Some issues to resolve from a Central European perspective. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2017, 25, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianoş, I.; Jones, R. Local aspects of change in the rural-urban fringe of a metropolitan area: A study of Bucharest, Romania. Habitat Int. 2019, 91, 102026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdick-Will, J.; Logan, J.R. Schools at the rural-urban boundary: Blurring the divide? Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2017, 672, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castán Broto, V.; Allen, A.; Rapoport, E. Interdisciplinary perspectives of urban metabolism. J. Ind. Ecol. 2012, 16, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkley, C. Cities as Coral Reefs: Using Rugosity to Measure Metabolism across the Urban Interface. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2019, 109, 1541–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianoș, I.; Cercleux, A.L.; Cocheci, R.M.; Tălângă, C.; Merciu, F.C.; Manea, C.A. Smart City needs a Smart Urban-Rural Interface. An Overview on Romanian Urban Transformations. In Handbook of Smart Cities; Augusto, J.C., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Weber, B.; Partridge, M. Rural-urban interdependence: A framework integrating regional, urban and environmental economic insights. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2016, 99, 464–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brueckner, J.K. Urban Sprawl: Diagnosis and Remedies. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2000, 23, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, M.; Chenal, J.; Joost, S. Addressing Urban Sprawl from the Complexity Sciences. Urban Sci. 2019, 3, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santasusagna Riu, A.; Úbeda Cartañá, X. Urban interfaces: Combining social and ecological approaches. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 772, 145625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cromartie, J. Appendix B: Historical development of ERS Rural-Urban classification systems. In Rationalizing Rural Area Classifications for the Economic Research Service: A Workshop Summary; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 145–164. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, M.; Heley, J. Conceptualisation of Rural-Urban Relations and Synergies. ROBUST Project, Financed by European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Grant Agreement No 727988. 2017. Available online: https://rural-urban.eu/publications/conceptualisation-rural-urban-relations-and-synergies (accessed on 17 February 2024).

- Garner, B. ‘Perfectly positioned’: The blurring of urban, suburban and rural boundaries in a southern community. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2017, 672, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castle, E.; Wu, J.; Weber, B. Place orientation and rural-urban interdependence. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2011, 33, 179–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiner, C.C. Beyond the edge and in between: (re)conceptualizing the rural-urban interface as meaning-model-metaphor. Prof. Geogr. 2016, 68, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luca, D.; Terrero-Davila, J.; Stein, J.; Lee, N. Progressive cities: Urban-rural polarisation of social values and economic development around the world. Urban Stud. 2023, 60, 2329–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichter, D.T.; Ziliak, J.P. The rural-urban interface: New patterns of spatial interdependence and inequality in America. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2017, 672, 6–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, R.; Webber, D.J. Do city region policies neglect rural areas? J. Rural Stud. 2024, 106, 103207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanche, D.; Casaló, L.V.; Angeles, R.M. Local place identity: A comparison between residents of rural and urban communities. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 82, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianoș, I.; Saghin, I.; Stoica, I.V.; Zamfir, D. Perennial values and cultural landscapes resilience. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 122, 225–229. [Google Scholar]

- Pryor, R.J. Defining the rural-urban fringe. Soc. Forces 1968, 47, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoggart, K. Convergence and divergence in European city hinterlands: A cross-national comparison. In The City’s Hinterland: Dynamism and Divergence in Europe’s Peri-Urban Territories; Hoggart, K., Ed.; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2005; pp. 155–170. [Google Scholar]

- Vaz, E.; Nijkamp, P. Gravitational forces in the spatial impacts of urban sprawl: An investigation of the region of Veneto, Italy. Habitat Int. 2015, 45, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntoshi, J.; Marques, B.; Martinez Almoyna, C.; Campays, C. Searching for identity: Finding the expression of place underground. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemak. Urban Sustain. 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanseverino, E.R.; Sanseverino, R.R.; Anello, E. A Cross-Reading Approach to Smart City: A European Perspective of Chinese Smart Cities. Smart Cities 2018, 1, 26–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stan, A.I. Landscape of Urban Fringes: Landscape Revival of Peripheral Areas; Ion Mincu University Press: Bucharest, Romania, 2009. (In Romanian) [Google Scholar]

- Petrişor, A.I. Comparative critical analysis of the systemic approach to the organization of the environment from the perspective of ecology, geography and spatial planning. Geopolit. Hist. Int. Relat. 2012, 4, 289–303. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter, D.T.; Brown, D.L.; Parisi, D. The rural–urban interface: Rural and small town growth at the metropolitan fringe. Popul. Space Place 2020, 27, e2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, P.; Kahsai, M.; Jackson, R.W. Beyond the Rural−Urban Dichotomy: Essay in Honor of Professor A. M. Isserman. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2013, 36, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocheci, R.M. Suburbanization in Romanian Metropolitan Areas. A Spatial Planning Perspective; Ion Mincu University Press: Bucharest, Romania, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Korcelli-Olejniczak, E. On City-Region Relations. Towards the Urban-Rural Region of Warsaw. Mitt. Österr. Geogr. Ges. 2015, 157, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Săgeată, R. The role of political factors in the urbanisation and regional development of Romania. J. Urban Reg. Anal. 2010, 2, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichler-Milanović, N.; Gutry-Korycka, M.; Rink, D. Sprawl in the post-socialist city: The changing economic and institutional context of central and eastern European cities. In Urban Sprawl in Europe: Landscapes, Land-Use Change & Policy; Couch, C., Leontidou, L., Petschel-Held, G., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 102–135. [Google Scholar]

- Dumitrache, L.; Zamfir, D.; Nae, M.; Simion, G.; Stoica, I.-V. The Urban Nexus: Contradictions and Dillemas of (Post) Communist (Sub) Urbanization in Romania. Hum. Geogr. J. Stud. Res. Hum. Geogr. 2016, 10, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanilov, K.; Sykora, L. Confronting Suburbanization: Urban Decentralization in Postsocialist Central and Eastern Europe; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ianoș, I. Causal relationships between economic dynamics and migration. Romania as case study. In Global Change and Human Mobility; Advances Geographical and Environmental Sciences; Dominguez-Mujica, J., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 303–322. [Google Scholar]

- Pászto, V.; Brychtová, A.; Tuček, P.; Lukáš, M.; Burian, J. Using a fuzzy inference system to delimit rural and urban municipalities in the Czech Republic in 2010. J. Maps 2015, 11, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbac-Cotoara-Zamfir, R.; Ferreira, C.S.S.; Salvati, L. Long-Term Urbanization Dynamics and the Evolution of Green/Blue Areas in Eastern Europe: Insights from Romania. Sustainability 2021, 13, 14068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. The Rise of the “City-region” Concept and its Development Policy Implications. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2008, 16, 1025–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandu, D. Updating Local Human Development Index Why How and with What Results. 2018. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/352560175_Actualizarea_indicelui_dezvoltariiumane_locale_de_ce_cum_si_cu_ce_rezultate_Updating_local_human_development_index_why_howand_with_what_results (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Bernt, M.; Volkmann, A. Suburbanisation in East Germany. Urban Stud. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyytiä, N. Rural-urban multiplier and policy effects in Finish rural regions: An inter-regional SAM analysis. Eur. Countrys. 2014, 6, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, H.; Habersetzer, A.; Meili, R. Rural-Urban Linkages and Sustainable Regional Development: The Role of Entrepreneurs in Linking Peripheries and Centers. Sustainability 2016, 8, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).