Functional or Neglected Border Regions? Analysis of the Integrated Development Plans of Borderland Municipalities in South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Borderlands as Everyday Functional Spaces

1.2. Planning Policies in Border Regions and Border Regions in Planning Policies

1.3. Case of South Africa: Borderland Municipalities’ Strategic Plans

2. Materials and Methods

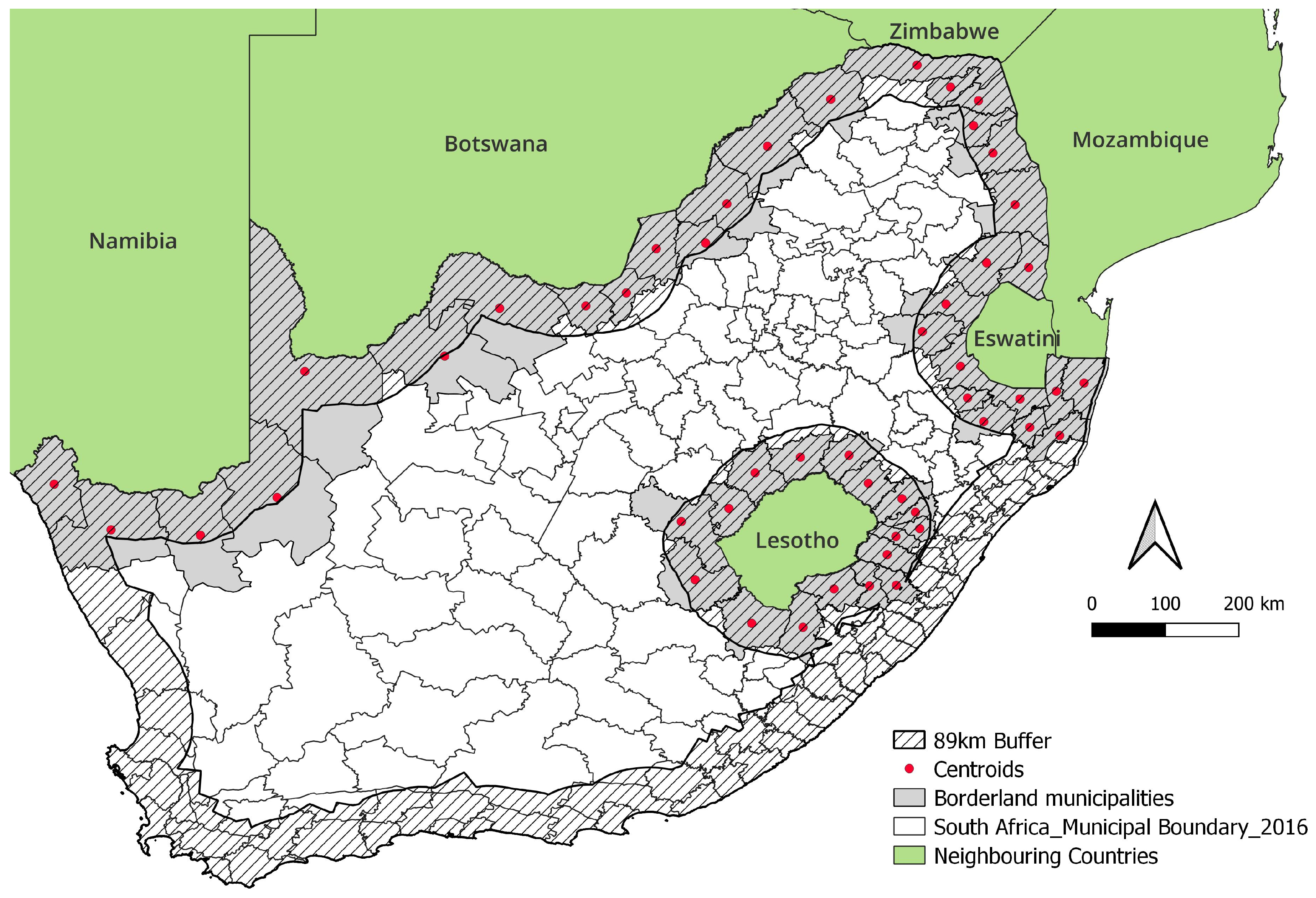

2.1. Spatial Analysis

2.2. Geographic Scope

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Thematic Coding

- The pre-determined keyword ‘border’ was searched in the IDPs to analyse the context in which each word appeared;

- Sentences that contained the keyword were retrieved for the text coding process. Words containing prefixes and suffixes were also included, while paragraph titles were excluded;

- If the context of the keyword border was related to the South African internal boundary instead of the international boundary, these words were not included in the text coding process. For example, Setsoto Local Municipality is bordered by Mantsopa Local Municipality;

- Coding emerging themes from the extracted sentences for each municipality and categories were formulated.

3. Results

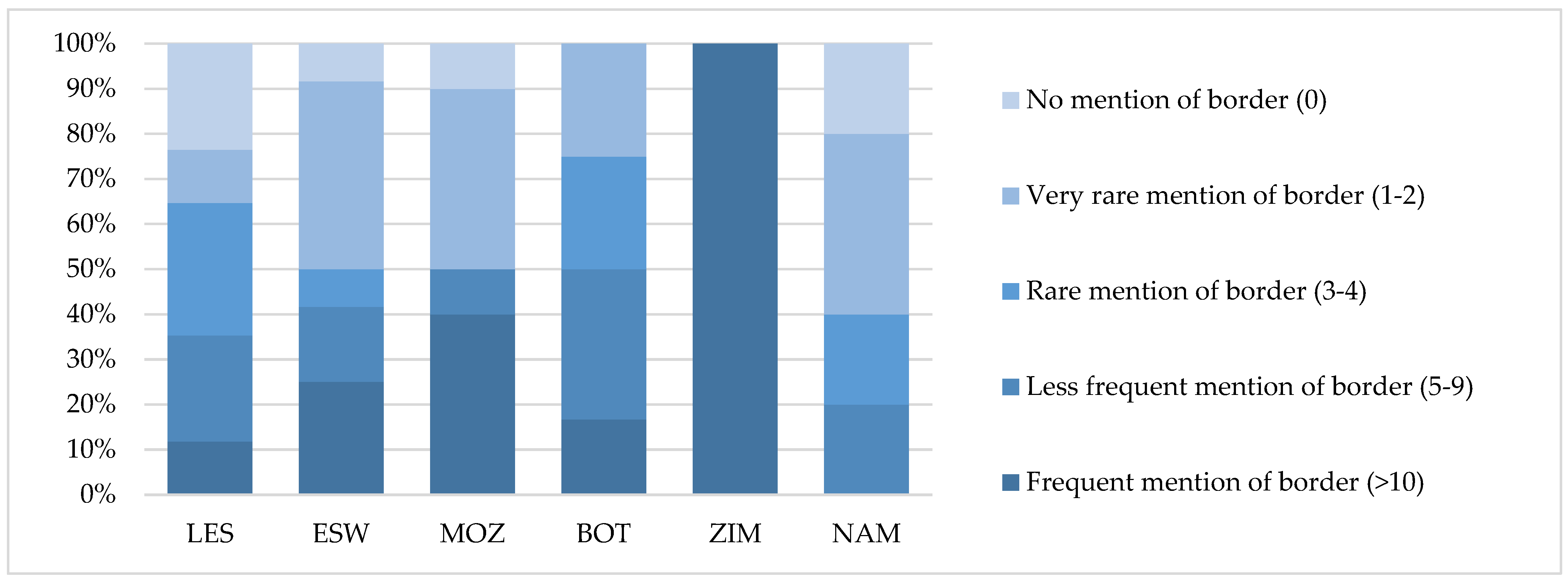

3.1. Word Analysis Approach: Frequency of Mentioning the Keyword Border

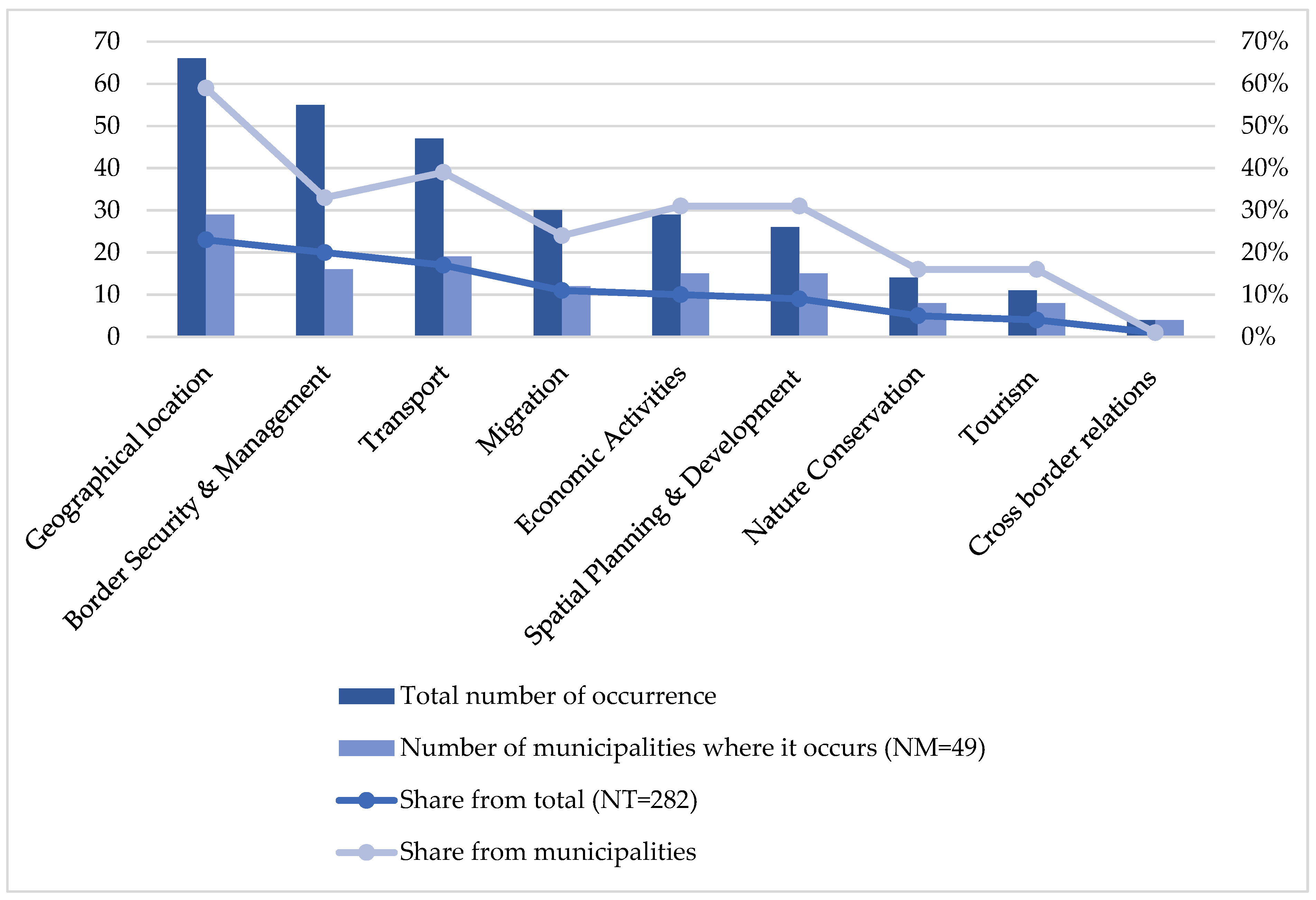

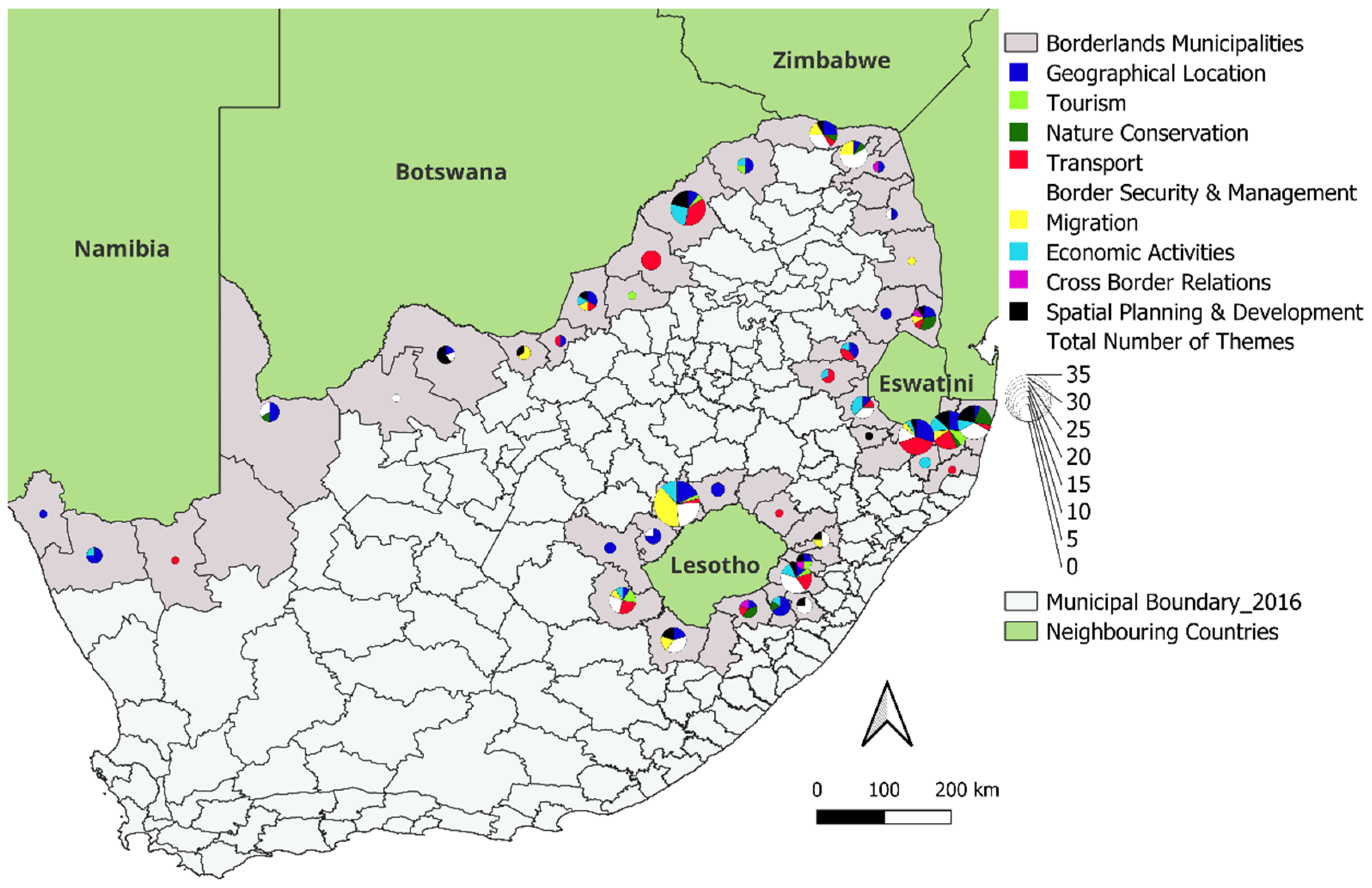

3.2. Thematic Analysis Approach: Emerging Themes Related to Border

- Group 1a: Less attention to the border with specific focuses—Neglected border regions

- Group 1b: Emerging awareness of border: on the edge—Gaining or losing interest in the future

- Group 2: Growing interest in border regions—Potential cross-border cooperations

4. Conclusions

- The frequency of the mentioning of the keyword border shows a close relation with the differences in municipality concentration along the borders, as well as with the area and population size of the border municipalities;

- As expected, the keyword border is mentioned concerning the geographical description of over 50% of the municipalities along every border section of South Africa. In the case of Zimbabwe and Namibia, they occur in the IDPs of every border municipality;

- ‘Border’ is least frequently mentioned in terms of three thematic considerations: Spatial Planning and Development, Tourism and Cross-border Relations. In Europe, tourism is the leading theme in cross-border projects, and regional planning and development is also the most frequently named element of cross-border projects (10th out of 42) [45].

- Nature conservation is a theme pursued by at least 50% of the municipalities along the borders with three neighbours (Mozambique, Zimbabwe and Namibia). In Greater Giyani Local Municipality, which shares a very short border with Mozambique, the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park could generate a common source of interest in the future.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fricke, C. Spatial Governance across Borders Revisited: Organizational Forms and Spatial Planning in Metropolitan Cross-border Regions. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 849–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasi, A.; Zimmerbauer, K. Penumbral borders and planning paradoxes: Relational thinking and the question of borders in spatial planning. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2016, 48, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, F. Challenges of Cross-Border Spatial Planning in the Metropolitan Regions of Luxembourg and Lille. Plan. Pract. Res. 2014, 29, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellano, F.; Kurowska-Pysz, J. The Mission-Oriented Approach for (Cross-Border) Regional Development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, N.; Adair, A.; Bartley, B.; Berry, J.; Creamer, C.; Driscoll, J.; McGreal, S.; Vigier, F. Delivering cross-border spatial planning: Proposals for the island of Ireland. Town Plan. Rev. 2007, 78, 485–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, C.; Knieling, J. Creating a Space for Cooperation: Soft Spaces, Spatial Planning and Territorial Cooperation on the Island of Ireland. In Proceedings of the Planning for Resilient Cities and Regions, AESOP-ACSP Joint Congress, Dublin, Ireland, 15–19 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Decoville, A.; Durand, F. Challenges and Obstacles in the Production of Cross-Border Territorial Strategies: The Example of the Greater Region. Trans. Assoc. Eur. Sch. Plan. 2017, 1, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plangger, M. Exploring the role of territorial actors in cross-border regions. Territ. Politics Gov. 2019, 7, 156–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, F.; Decoville, A. A multidimensional measurement of the integration between European border regions. J. Eur. Integr. 2020, 42, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. Spatial planning in cross-border regions: A systems-theoretical perspective. Plan. Theory 2016, 15, 68–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, S.; Durand, F. Mobility planning in cross-border metropolitan regions: The European and North American experiences. Territ. Politics Gov. 2022, 10, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, E. Spatial Planning, Territorial Development, and Territorial Impact Assessment. J. Plan. Lit. 2019, 34, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrechts, L. Strategic (Spatial) Planning Reexamined. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2004, 31, 743–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. Collaborative Planning; Macmillan Education: London, UK, 1997; 338p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. In Search of the “Strategic” in Spatial Strategy Making. Plan. Theory Pract. 2009, 10, 439–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrón, M.A.; Greybeck, B. Borderlands Epistemologies and the Transnational Experience; Fronteras Epistemológicas y la Experiencia Transnacional. GiST Educ. Learn. Res. J. 2014, 8, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasi, A. Inclusion, exclusion and territorial identities. The meanings of boundaries in the globalizing geopolitical landscape. Nord. Samhallsgeografisk Tidskr. 1996, 23, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, D. Contemporary Research Agendas in Border Studies: An Overview. In The Ashgate Research Companion to Border Studies; Wastl-Walter, D., Ed.; Ashgate: Farnham, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, C.; Jones, R.; Paasi, A.; Amoore, L.; Mountz, A.; Salter, M.; Rumford, C. Interventions on rethinking “the border” in border studies. Political Geogr. 2011, 30, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, K.D. The Alignment of Local Borders. Territ. Politics Gov. 2014, 2, 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaumik, S. Everyday Lives in Peripheral Spaces: A Case of Bengal Borderlands. Bord. Glob. Rev. 2021, 3, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wastl-Walter, D. Borderlands. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, 1st ed.; Kitchin, R., Thrift, N., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 332–339. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, G. Bordering and Ordering the Twenty-First Century: Understanding Borders; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers: Lanham, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, O.J. The dynamics of border interaction: New approaches to border analysis. In Global Boundaries; Schofield, C.H., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1994; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Paasi, A. Examining the persistence of bounded spaces: Remarks on regions, territories, and the practices of bordering. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2022, 104, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, W.; Alizadeh, T.; Eslami-Andargoli, L. Planning across borders. Aust. Plan. 2013, 50, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haselsberger, B. Decoding borders. Appreciating border impacts on space and people. Plan. Theory Pract. 2014, 15, 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasi, A. A Border Theory: An Unattainable Dream or a Realistic Aim for Border Scholars? In The Ashgate Research Companion to Border Studies; Wastl-Walter, D., Ed.; Ashgate: Farnham, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 11–31. [Google Scholar]

- Pallagst, K.; Hartz, A. Spatial planning in border regions: A balancing act between new guiding principles and old planning traditions? In Border Futures—Zukunft Grenze—Avenir Frontière: The Future Viability of Cross-Border Cooperation; Pallagst, K., Hartz, A., Caesar, B., Eds.; Verlag der ARL: Hannover, Germany, 2022; pp. 77–95. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, R.; Marais, L.; Etienne, N. Secondary Cities in South Africa. In Urban Geography in South Africa; Perspective and Theory, 1st ed.; Massey, R., Gunter, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Germany, 2019; pp. 121–137. [Google Scholar]

- Maylam, P. Explaining the Apartheid City: 20 Years of South African Urban Historiography. J. South. Afr. Stud. 1995, 21, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, A.J. Towards the post-apartheid city. L’Espace Géographique 1999, 28, 300–308. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44382626 (accessed on 10 January 2024). [CrossRef]

- Binns, T.; Nel, E. Devolving Development: Integrated Development Planning and Developmental Local Government in Post-apartheid South Africa. Reg. Stud. 2002, 36, 921–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pycroft, C. Integrated development planning or strategic paralysis? Municipal development during the local government transition and beyond. Dev. South. Afr. 1998, 15, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odendaal, N.; McCann, A. Spatial planning in the global South: Reflections on the Cape Town Spatial Development Framework. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2016, 38, 405–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wastl-Walter, D. Borderlands. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, 2nd ed.; Kobayashi, A., Ed.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 373–379. [Google Scholar]

- Nshimbi, C.C.; Moyo, I.; Oloruntoba, S.O. Borders, Informal Cross-Border Economies and Regional Integration in Africa. Afr. Insight 2018, 48, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Horváth, E. A földrajzi centrum és periféria lehetséges lehatárolásai. (Possible methods for demarcating core and periphery areas in geography). Tér Társadalom (Space Soc.) 2007, 21, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, B.L.; Lune, H. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences, 9th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2017; 251p. [Google Scholar]

- Kibiswa, N. Directed Qualitative Content Analysis (DQlCA): A Tool for Conflict Analysis. Qual. Rep. 2019, 24, 2059–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, R.P. Basic Content Analysis, 2nd ed.; Sage University Papers Series; Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences; McElroy, S., Ed.; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Municipalities of South Africa. Available online: www.municipalities.co.za (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Statistical Data of South Africa. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/ (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- South African National Parks. Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park. Available online: https://www.sanparks.org/conservation/transfrontier/great-limpopo/overview (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Aggregated Data Regarding Projects and Beneficiaries of European Union Cross-Border, Transnational and Interregional Cooperation Programmes. Available online: https://keep.eu/statistics (accessed on 12 January 2024).

| A | B | C | D | E |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Length of Border (km) | Number of Municipalities | Length of Border per Municipalities (km) (B/C) | Municipality Concentration by Border (C/B) |

| Eswatini | 430 | 12 | 35.8 | 2.79 |

| Mozambique | 491 | 10 | 49.1 | 2.03 |

| Lesotho | 909 | 17 | 53.5 | 1.87 |

| Zimbabwe | 225 | 2 | 112.5 | 0.89 |

| Botswana | 1840 | 11 | 167.3 | 0.59 |

| Namibia | 967 | 5 | 193.4 | 0.52 |

| Direct Border Location | Indirect Border Location | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequent mention of border (>10) | 7 | 1 | 8 |

| Less frequent mention of border (5–9) | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| Rare mention of border (3–4) | 8 | 2 | 10 |

| Very rare mention of border (1–2) | 10 | 5 | 15 |

| No mention of border (0) | 5 | 2 | 7 |

| Total | 39 | 10 | 49 |

| A | F | G | H | I | J |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Total Area of Municipalities (km2) | Average Area of Municipalities (km2) | Smallest Municipality (km2) | Largest Municipality (km2) | Standard Deviation |

| Eswatini | 51,828 | 4319 | 1943 | 7152 | 1553.4 |

| Mozambique | 60,249 | 6025 | 2642 | 10,347 | 2691.5 |

| Lesotho | 75,264 | 4427 | 1521 | 9886 | 2387.5 |

| Zimbabwe | 12,989 | 6495 | 2642 | 10,347 | 5448.3 |

| Botswana | 154,856 | 14,078 | 3646 | 44,399 | 11,846.2 |

| Namibia | 113,948 | 22,790 | 9608 | 44,399 | 13,469.3 |

| Total | 469,134 | 9689 | 1521 | 44,399 | 7714.6 |

| A | K | L | M | N | O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Total Population Size of Municipalities (Capita) | Average Population Size of Municipalities (Capita) | Lowest Population Size (Capita) | Highest Population Size (Capita) | Standard Deviation |

| Eswatini | 2,821,555 | 235,129 | 89,614 | 695,913 | 165,847.5 |

| Mozambique | 3,425,611 | 342,561 | 132,009 | 695,913 | 190,556.7 |

| Lesotho | 2,912,739 | 171,338 | 29,526 | 787,803 | 178,667.7 |

| Zimbabwe | 629,246 | 314,623 | 132,009 | 497,237 | 258,255.2 |

| Botswana | 1,656,807 | 150,618 | 84,021 | 314,394 | 70,726.9 |

| Namibia | 247,422 | 49,484 | 12,333 | 107,161 | 40,195.0 |

| Total | 9,347,852 | 190,772.5 | 12,333 | 787,803 | 162,025.4 |

| A | P | Q | R | S | T |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Population Density (Capita/km2) | Average Population Density (Capita/km2) | Lowest Population Density (Capita/km2) | Highest Population Density (Capita/km2) | Standard Deviation |

| Eswatini | 54.44 | 54.49 | 27.42 | 97.30 | 25.31 |

| Mozambique | 56.86 | 68.32 | 12.76 | 188.20 | 49.69 |

| Lesotho | 38.7 | 39.9 | 4.08 | 81.48 | 25.94 |

| Zimbabwe | 48.44 | 100.48 | 12.76 | 188.20 | 124.06 |

| Botswana | 10.7 | 21.14 | 2.41 | 86.23 | 24.44 |

| Namibia | 2.17 | 1.94 | 0.78 | 2.63 | 0.85 |

| Total | 40.15 | 47.71 | 0.78 | 188.2 | 35.31 |

| Maluti-a-Phofung | Elundini | Inkosi Langalibalele | Greater Giyani | Kai !Garib | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neighbouring country | Lesotho | Lesotho | Lesotho | Mozambique | Namibia |

| Transport connection | National roads (N5 and N3) | Provincial roads (R396 and R56) | National roads (N3), Provincial roads (R103 and R74) | Provincial roads (R81, R529 and R578) | National roads (N10 and N14) |

| Population size (2016) | 353,452 | 144,929 | 215,182 | 256,127 | 68,929 |

| Growth rate (2001–2011) | −0.71% | 0.05% | 1.30% | 0.14% | 1.16% |

| Per capita income | R 32,400 (2019) | R 26,600 (2016) | R 30,000 (2011) | R 30,000 (2011) | R 15,000 (2011) |

| Economically active population | 34% (2019) | 18.5% (2011) | n.a. | n.a. | 71.65% (2016) |

| Dependency ratio per 100 (15–64 years) | 62.6 (2016) | 75.7 (2016) | 67.8 (2016) | 74.72 (2011) | 38 (2016) |

| Rural population proportion (2016) | 62.5% | 67.1% | 65.9% | 86.6% | 23.8% |

| Unemployment rate (2011) | 41.8% | 44.4% | 42.7% | 47% | 10% |

| Youth unemployment rate (15–34 years) (2011) | 53% | 52.8% | 52.8% | 61.2% | 10% |

| Ratio of the population under the poverty line * | 73.09% (2019) | 69.48% (2016) | 76% (2011) | 82.9% (2013) | 51.92% (2018) |

| Eswatini | Mozambique | Lesotho | Zimbabwe | Botswana | Namibia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geographical Location | 7 | 8 | 10 | 2 | 7 | 3 |

| Border Security and Management | 3 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| Transport | 8 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| Migration | 3 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| Economic Activities | 7 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Spatial Planning and Development | 5 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 0 |

| Nature Conservation | 3 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Tourism | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Cross-border Relations | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Number of municipalities * | 12 | 10 | 17 | 2 | 11 | 5 |

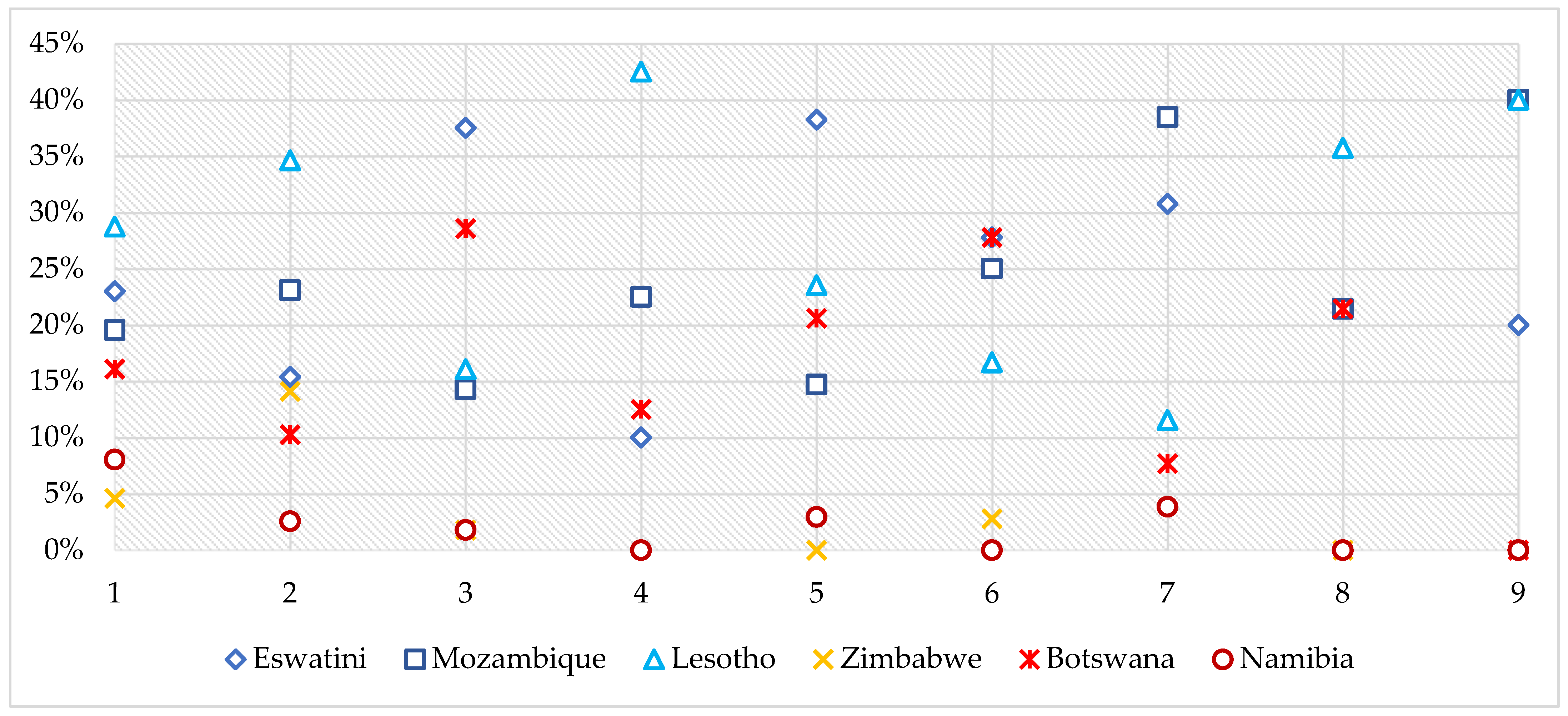

| Theme * | Eswatini | Mozambique | Lesotho | Zimbabwe | Botswana | Namibia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| 3 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 3 |

| 4 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 5 | |

| 5 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 3 | |

| 6 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 3 | |

| 7 | 6 | 3 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 3 |

| 8 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 7 | ||

| 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maila, T.L.; Czimre, K. Functional or Neglected Border Regions? Analysis of the Integrated Development Plans of Borderland Municipalities in South Africa. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci8020046

Maila TL, Czimre K. Functional or Neglected Border Regions? Analysis of the Integrated Development Plans of Borderland Municipalities in South Africa. Urban Science. 2024; 8(2):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci8020046

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaila, Thato L., and Klára Czimre. 2024. "Functional or Neglected Border Regions? Analysis of the Integrated Development Plans of Borderland Municipalities in South Africa" Urban Science 8, no. 2: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci8020046

APA StyleMaila, T. L., & Czimre, K. (2024). Functional or Neglected Border Regions? Analysis of the Integrated Development Plans of Borderland Municipalities in South Africa. Urban Science, 8(2), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci8020046