Artistic Interventions as Urban Planning Tools: A Systematic Review of Community-Based Cultural Tourism in Cities

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Outcome-focused rather than process-oriented research: Current research tends to focus primarily on economic impacts or visitor satisfaction metrics [4], with insufficient examination of how community-led artistic initiatives contribute to cultural preservation and heritage transmission. Most studies emphasize outcomes rather than processes, failing to analyze the mechanisms through which resident-controlled art activities maintain cultural authenticity while accommodating tourism development [5].

- Inadequate understanding of community relationships: Existing research does not adequately address the complex interactions among environmental contexts, community relationships, collaborative methodologies, and development outcomes. The integration of artistic interventions within community-controlled heritage management frameworks requires systematic analysis to identify effective processes that ensure genuine cultural exchange while preserving community agency in cultural representation [11,12].

- Cultural commodification and authenticity loss: Challenges persist in integrating art into community contexts sustainably without leading to the commodification of culture or the loss of authenticity that often arises from externally driven projects lacking genuine community involvement [10]. This research responds to the need for a comprehensive understanding of collaborative art processes that enable authentic tourist–resident interactions without compromising heritage integrity or community empowerment.

- To systematically analyze the current state of research on artistic interventions in urban planning and their impact on community participation (2015–2025).

- To identify key thematic clusters and gaps in the integration of creative practices within urban development strategies.

- To develop a theoretical framework—the Arts-led Cultural Interaction and Sustainable Community Development (ACSC) framework—that operationalizes the relationship between artistic interventions and sustainable urban planning.

2. Conceptual Background

2.1. Artistic Interventions as Urban Planning Tools

2.2. Community-Based Cultural Tourism

2.3. Theoretical Interrelationships: Art, Planning, and Tourism

- Internal function: They visualize and reinforce local identity, making intangible heritage tangible for the community [23].

3. Methods

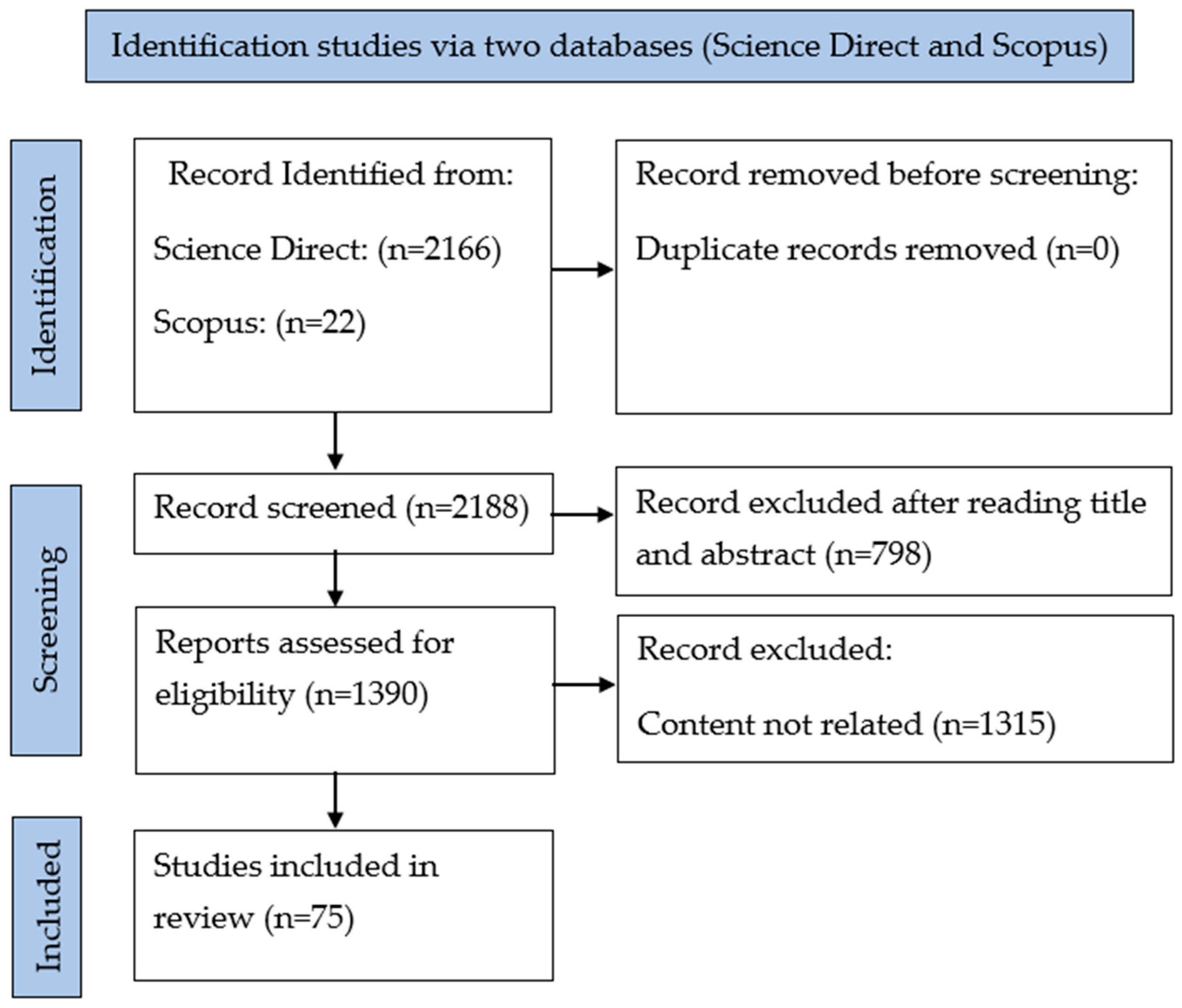

3.1. Literature Review Methodology

3.2. Systematic Literature Review

3.3. Case Studies

3.4. Data Analysis

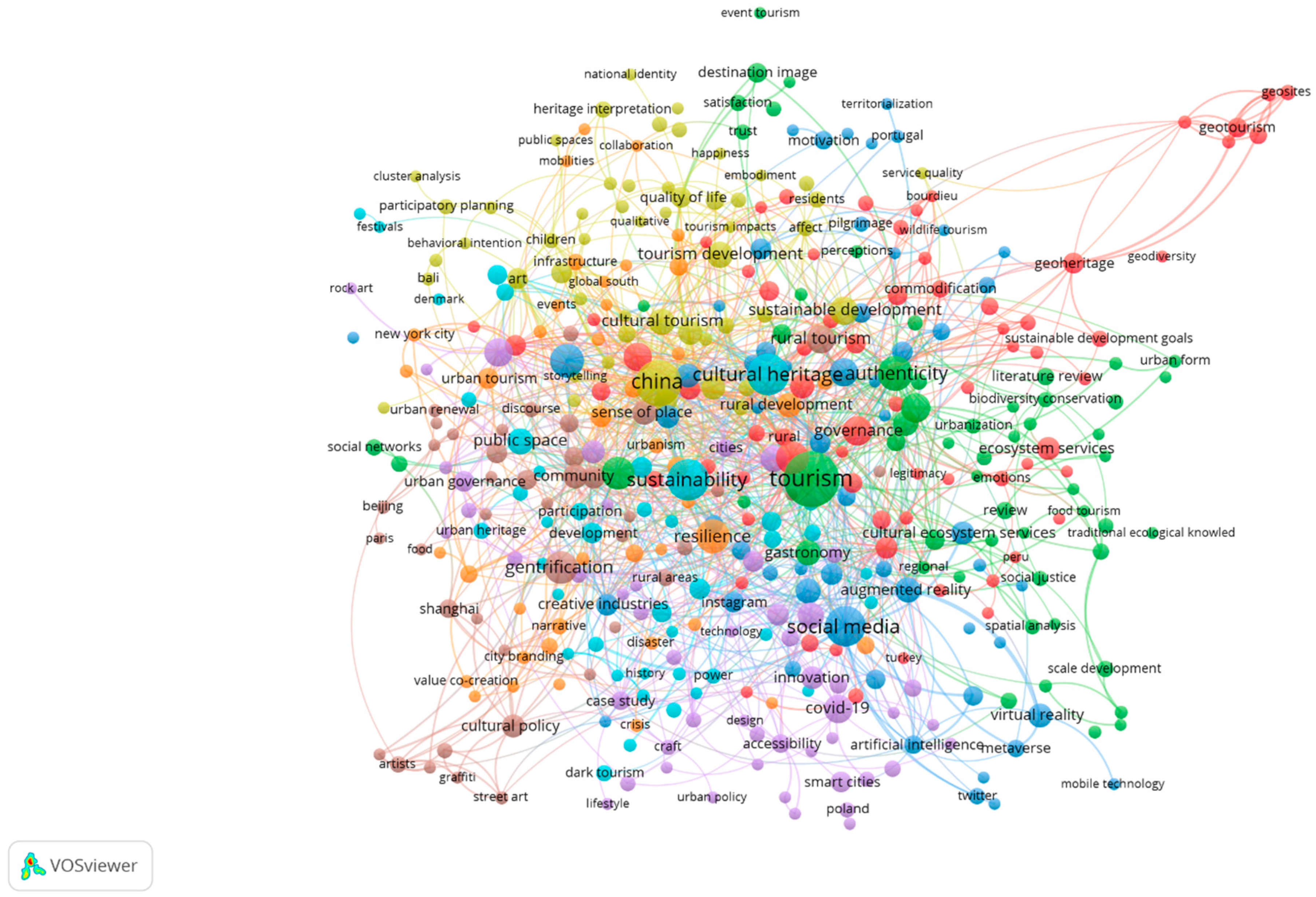

4. Results

- Cluster 1: Community Engagement/Cultural Landscape

- Cluster 2: Social–Ecological Systems/Green Spaces

- Cluster 3: Communication/Social Media

- Cluster 4: Co-creation/Residents

- Cluster 5: Design/Innovation

- Cluster 6: Artistic Interventions/Social Sustainability

- Cluster 7: City Branding/Rural Revitalization

- Cluster 8: Artists/Sharing Economy

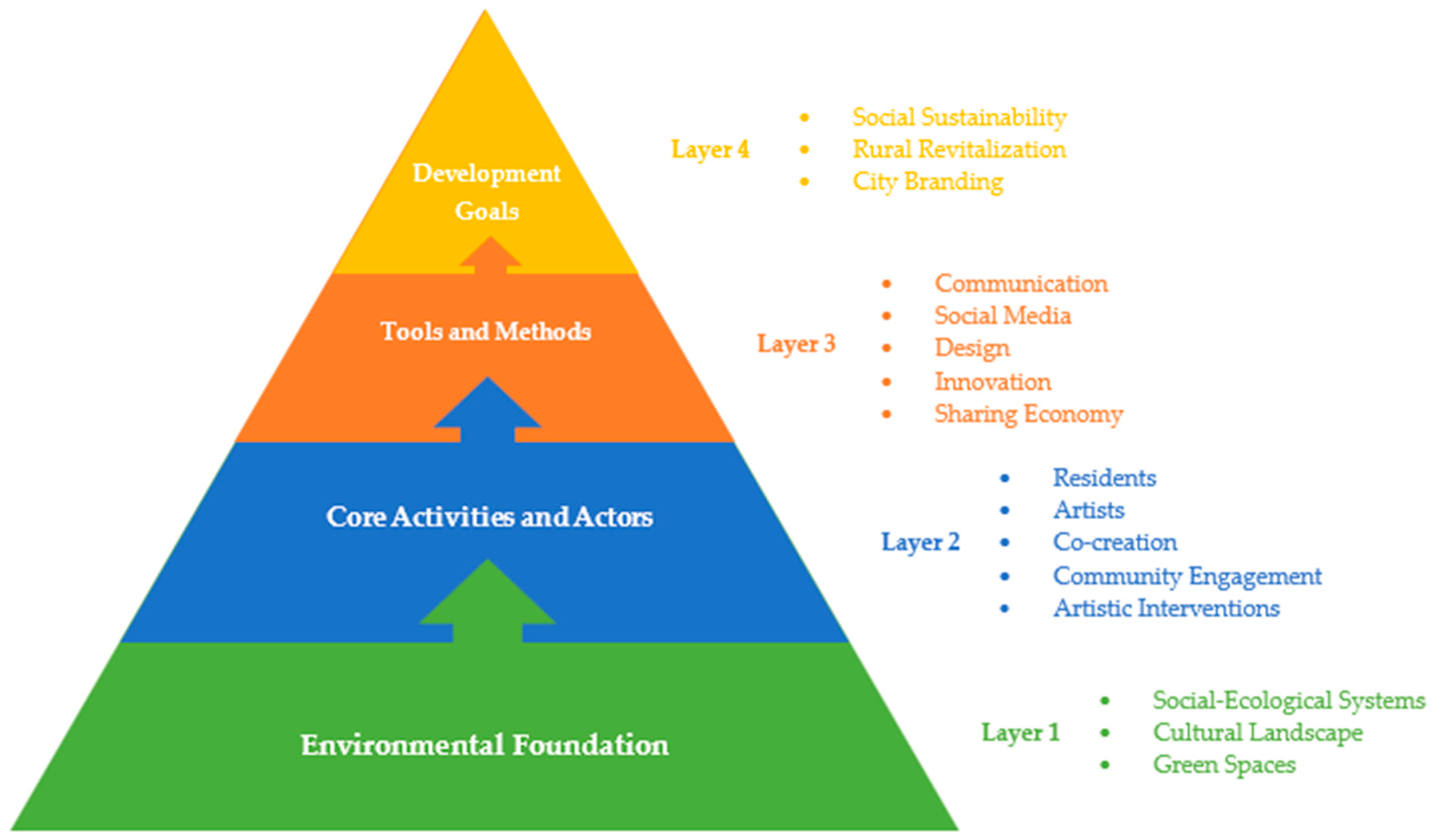

5. Development of the Arts-Led Cultural Interaction and Sustainable Community Framework

- Layer 1: Environmental Foundation

- Layer 2: Core Activities and Actors

- Layer 3: Tools and Methods

- Layer 4: Development Goals

6. Discussion

6.1. Critical Challenges: Navigating Power Dynamics and Displacement Risks

- A primary risk is the co-optation of local culture to fuel real estate speculation. To mitigate this, the framework must be paired with anti-displacement policies, ensuring that economic benefits from art tourism directly support residents—for example, through affordable housing protections or community land trusts.

- The framework also emphasizes avoiding tokenism. Governance structures should explicitly prioritize local voices, transferring decision-making authority over funding, aesthetic choices, and narrative construction from external experts to community councils. Addressing these power dynamics is crucial for ensuring that community-controlled tourism is substantive rather than merely rhetorical.

6.2. Translating Rural Insights to High-Density Urban Contexts

- Rural interventions frequently use monumental scale to create destination awareness across expansive landscapes. Urban interventions, by contrast, must navigate spatial scarcity and visual clutter. Translating rural insights to cities therefore involves shifting the focus from “monumentality” to “connectivity,” using art to weave together fragmented urban fabrics rather than standing in isolation.

- Rural revitalization typically aims to attract external visitors to stimulate local economies (economic focus). Urban artistic planning, however, often prioritizes social cohesion among dense, diverse populations (social focus). While the form of art may be similar, success metrics differ: rural projects measure success by visitor numbers, whereas urban projects should emphasize resident retention and the strength of community networks. Furthermore, operationalizing social sustainability in the context of artistic interventions requires moving beyond purely qualitative indicators. In practice, researchers and practitioners should integrate quantitative metrics to measure these outcomes effectively. This could include tracking community participation rates in local art initiatives, measuring the distribution of economic benefits within the community, and utilizing Social Network Analysis (SNA) to map the strengthening of social cohesion and local stakeholder connectivity. By combining these quantitative tools with traditional qualitative assessments, future initiatives can provide a more comprehensive, measurable, and objective evaluation of social sustainability.

7. Conclusions

7.1. Practical Implications

- Academic Research and Higher Education

- Cultural Tourism Authorities

- Urban Planners

- Urban Tourism Management

7.2. Study Limitations

7.3. Future Research

- Future research should examine the intersection of Cluster 8 and Cluster 6, focusing on how sharing economy platforms affect the long-term financial resilience of local artists.

- A disconnect was observed between Cluster 3 (Communication, Social Media) and Cluster 2 (Social–Ecological Systems). Researchers should explore how digital platforms can be used not only for promotion but also for monitoring and preserving urban green spaces and ecological assets in high-traffic tourist areas.

- There is a need for robust metrics to quantify the social sustainability outcomes identified in Cluster 6, moving beyond qualitative descriptions toward standardized indicators suitable for policy evaluation.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Richards, G.; Wilson, J. Developing creativity in tourist experiences: A solution to the serial reproduction of culture? Tour. Manag. 2005, 27, 1209–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molz, J.G. Travel Connections; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woosnam, K.M.; Norman, W.C.; Ying, T. Exploring the Theoretical Framework of Emotional Solidarity between Residents and Tourists. J. Travel Res. 2009, 48, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishinaka, M.; Masuda, H.; Frochot, I. Exploring the perceptions and attitudes of residents at modern art festivals: The effect of social behavior on support for tourism. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2023, 30, 100818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moayerian, N.; McGehee, N.G.; Stephenson, M.O. Community cultural development: Exploring the connections between collective art making, capacity building, and sustainable community-based tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2022, 93, 103355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M. Rural Geography: Processes, responses and experiences in rural restructuring. Rural. Geogr. 2004, 21, 375–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, E. Art and intimacy: How the arts began. Choice Rev. Online 2000, 38, 38–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicks, B. Culture on Display: The Production of Contemporary Visitability; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2004; Available online: http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA66952575 (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Qu, M.; Zollet, S. Neo-endogenous revitalisation: Enhancing community resilience through art tourism and rural entrepreneurship. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 97, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, E.; Johanson, K.; Molan, D. Activating rural infrastructures in regional communities: Cultural funding, silo art works and the challenge of local benefit. J. Rural. Stud. 2024, 106, 103239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dredge, D.; Jamal, T. Progress in tourism planning and policy: A post-structural perspective on knowledge production. Tour. Manag. 2015, 51, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity|UNESCO. 2 November 2001. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/legal-affairs/unesco-universal-declaration-cultural-diversity (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Wang, S.; Imbaya, B.; Matiku, S.; Nthiga, R.; Rop, W. Community-Based Tourism: Global perspectives, benefits, challenges, and research frameworks for sustainable development. Events Tour. Rev. 2025, 8, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vujko, A.; Knežević, M.; Arsić, M. The future is in sustainable urban tourism: Technological innovations, emerging mobility systems, and their role in shaping smart cities. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M. One Place After Another; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebracki, M. Engaging geographies of public art: Indwellers, the ‘Butt Plug Gnome’ and their locale. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2012, 13, 735–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, C. The Creative City; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courage, C. Arts in Place; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, F.; Jackson, B. Zealous nut: A conversation with Project for Public Spaces founder Fred Kent. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2016, 9, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.; Richards, G. (Eds.) Tourism and Sustainable Community Development; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C. Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 613–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N. Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grodach, C. Art spaces in community and economic development: Connections to neighborhoods, artists, and the cultural economy. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2010, 31, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M. From city marketing to city branding: Towards a theoretical framework for developing city brands. Place Brand. 2004, 1, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G. Hard-branding the cultural city–from Prado to Prada. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2003, 27, 417–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, W-65–W-94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhou, X.; Wang, M. Analyzing and visualizing the spatial interactions between tourists and locals: A Flickr study in ten US cities. Cities 2018, 74, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Criado, A.R. The art of writing literature review: What do we know and what do we need to know? Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 29, 101717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Weiler, B.; Smith, L.D.G. Place attachment and pro-environmental behaviour in national parks: The development of a conceptual framework. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 20, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Cros, H. A new model to assist in planning for sustainable cultural heritage tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2001, 3, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, G.; Rajabifard, A. Sustainable development and geospatial information: A strategic framework for integrating a global policy agenda into national geospatial capabilities. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2017, 20, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selman, P. Community participation in the planning and management of cultural landscapes. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2004, 47, 365–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, F.M. City branding: Theory and cases. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2011, 7, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F.; Folke, C.; Colding, J. Linking social and ecological systems: Management practices and social mechanisms for building resilience. Choice Rev. Online 1998, 36, 36–0288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. A General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilgrim, S.; Pretty, J.; Adams, B.; Berkes, F.; De Athayde, S.F.; Dudley, N.; Hunn, E.; Maffi, L.; Milton, K.; Rapport, D.; et al. The intersections of biological diversity and cultural diversity: Towards integration. Conserv. Soc. 2009, 7, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plieninger, T.; Bieling, C.; Fagerholm, N.; Byg, A.; Hartel, T.; Hurley, P.; López-Santiago, C.A.; Nagabhatla, N.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Raymond, C.M.; et al. The role of cultural ecosystem services in landscape management and planning. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2016: Monitoring Health for the Sustainable Development Goals SDGs; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, M. Public Places Urban Spaces; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.W. Activity, exercise and the planning and design of outdoor spaces. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, O.; Lennon, M.; Scott, M. Green space benefits for health and well-being: A life-course approach for urban planning, design and management. Cities 2017, 66, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennell, D.A. Tourism Ethics; Channel View Publications, Ltd.: Bristol, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.; Twining-Ward, L. Monitoring for a sustainable tourism transition. In Surrey Open Research Repository (University of Surrey); CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2005; Available online: https://openresearch.surrey.ac.uk/esploro/outputs/book/Monitoring-for-a-sustainable-tourism-transition/99513714402346 (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Redman, C.L.; Grove, J.M.; Kuby, L.H. Integrating Social Science into the Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) Network: Social Dimensions of Ecological Change and Ecological Dimensions of Social Change. Ecosystems 2004, 7, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.N. Agri-culture: Reconnecting people, land and nature. Choice Rev. Online 2003, 40, 40–4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeanrenaud, S.; Adams, W. Transition to Sustainability: Towards a Humane and Diverse World; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, R.E.; Schramm, W. The process and effects of mass communication. Am. Cathol. Sociol. Rev. 1955, 16, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, S.J. Introduction to Mass Communication: Media Literacy and Culture. 2008. Available online: http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA80217754 (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Setiawan, A.R. Tourism and Intercultural Communication: A theoretical study. J. Komun. 2023, 17, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2009, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, T. What is Web 2.0: Design Patterns and Business Models for the Next Generation of Software. MPRA Paper. 2007. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/pra/mprapa/4578.html (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Xiang, Z.; Gretzel, U. Role of social media in online travel information search. Tour. Manag. 2009, 31, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Sigala, M.; Xiang, Z.; Koo, C. Smart tourism: Foundations and developments. Electron. Mark. 2015, 25, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munar, A.M.; Jacobsen, J.K.S. Motivations for sharing tourism experiences through social media. Tour. Manag. 2014, 43, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Yao, Y. How tourist power in social media affects tourism market regulation after unethical incidents: Evidence from China. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 91, 103296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S.; Thal, K. The impact of social media on the consumer decision Process: Implications for tourism marketing. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasemsarn, K. Applying Classic Literature to Facilitate Cultural Heritage Tourism for Youth through Multimedia E-Book. Heritage 2024, 7, 5148–5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasemsarn, K.; Sawadsri, A. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) in Heritage Education: A Multimedia Approach to ‘Phra Aphai Mani’. Heritage 2024, 7, 5907–5931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Mediating tourist experiences. Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 36, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. The future of competition: Co-creating unique value with customers. Choice Rev. Online 2004, 41, 41–6635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Institutions and axioms: An extension and update of service-dominant logic. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 44, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.I.; Gilmore, J.H. The experience economy: Work is theatre & every business a stage. Choice Rev. Online 1999, 37, 37–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Collaborative destination marketing: A case study of Elkhart county, Indiana. Tour. Manag. 2006, 28, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M.J. Basic Concepts of Intercultural Communication: Selected Readings. 2013. Available online: http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA38876763 (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Jamal, T.; Camargo, B.A. Tourism governance and policy: Whither justice? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 25, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCTAD. Creative Economy Outlook 2024; UNCTAD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://unctad.org/publication/creative-economy-outlook-2024 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Dickinger, A.; Kolomoyets, Y. Value co-creation in tourism living labs. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 183, 114820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maziliauske, E. Innovation for sustainability through co-creation by small and medium-sized tourism enterprises (SMEs): Socio-cultural sustainability benefits to rural destinations. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2023, 50, 101201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, D.; Saxena, G. Participative co-creation of archaeological heritage: Case insights on creative tourism in Alentejo, Portugal. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 79, 102790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woosnam, K.M. Using Emotional Solidarity to Explain Residents’ Attitudes about Tourism and Tourism Development. J. Travel Res. 2011, 51, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalager, A. 100 innovations that transformed tourism. J. Travel Res. 2013, 54, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzini, E. Design, When Everybody Designs; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, D. The Design of Everyday Things; Vahlen: Munich, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramsch, C. The multilingual subject. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 2006, 16, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidd, J.; Bessant, J.; Pavitt, K. Managing Innovation: Integrating Technological, Market and Organizational Change; University of Maribor Digital Library (University of Maribor): Maribor, Slovenia, 1997; Available online: https://dk.um.si/IzpisGradiva.php?id=28226 (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Bennett, M.J. Constructing the capacity for viable multicultural organizations. In Relational Economics and Organization Governance; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Okazaki, E. A Community-Based Tourism Model: Its conception and use. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheer, J.M.; Belhassen, Y.; Kujawa, J. The search for spirituality in tourism: Toward a conceptual framework for spiritual tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 24, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R. Promoting Women’s Empowerment Through Involvement in Ecotourism: Experiences from the Third World. J. Sustain. Tour. 2000, 8, 232–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappeller, R. Artistic interventions for urban innovation. Cities 2024, 147, 104792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froidevaux, S. “60×60”: From architectural design to artistic intervention in the context of urban environmental change. City Cult. Soc. 2013, 4, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoop, M.; Kirchberg, V.; Kaddar, M.; Barak, N.; De Shalit, A. Urban artistic interventions: A typology of artistic political actions in the city. City Cult. Soc. 2022, 29, 100449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikuni, J.; Dehove, M.; Dörrzapf, L.; Moser, M.K.; Resch, B.; Böhm, P.; Prager, K.; Podolin, N.; Oberzaucher, E.; Leder, H. Art in the city reduces the feeling of anxiety, stress, and negative mood: A field study examining the impact of artistic intervention in urban public space on well-being. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2024, 7, 100215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanardi, M.; Lucarelli, A.; Pasquinelli, C. Towards brand ecology. Mark. Theory 2013, 13, 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyara, G.; Jones, E. Community-based tourism Enterprises development in Kenya: An exploration of their potential as avenues of poverty reduction. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 628–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grodach, C.; Foster, N.; Murdoch, J. Gentrification, displacement and the arts: Untangling the relationship between arts industries and place change. Urban Stud. 2016, 55, 807–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orum, A.M. The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Urban and Regional Studies; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, B. Sustainable rural tourism strategies: A tool for development and conservation. J. Sustain. Tour. 1994, 2, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Tourism and Social Marketing; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillip, S.; Hunter, C.; Blackstock, K. A typology for defining agritourism. Tour. Manag. 2009, 31, 754–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telfer, D.J.; Sharpley, R. Tourism and Development in the Developing World; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Braun, E.; Petersen, S. Branding the destination versus the place: The effects of brand complexity and identification for residents and visitors. Tour. Manag. 2016, 58, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J. Creating Selves; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.K.; Diekmann, A. Tourism and wellbeing. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 66, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. You are what you can access: Sharing and collaborative consumption online. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 67, 1595–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Zhang, G. When Western hosts meet Eastern guests: Airbnb hosts’ experience with Chinese outbound tourists. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 75, 288–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P. Factors of satisfaction and intention to use peer-to-peer accommodation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 55, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botsman, R.; Rogers, R. What’s Mine Is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption. 2010. Available online: http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB04496306 (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Ramaano, A.I. Toward tourism-oriented community-based natural resource management for sustainability and climate change mitigation leadership in rural municipalities. J. Humanit. Appl. Soc. Sci. 2024, 7, 107–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Sanz-Hernández, A.; Hernández-Muñoz, S.M. Artistic Interventions in Urban Renewal: Exploring the social impact and contribution of public art to sustainable urban development goals. Societies 2024, 14, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Peer-reviewed journal articles | Non-peer-reviewed sources (e.g., blogs, non-reviewed reports) |

| Publications in English | Non-English publications |

| Journals and conference papers | Working papers and organizational websites |

| Categories: Social sciences; arts and humanities | Categories outside the selected fields. |

| Database | Search Term (Titles, Abstracts, and Keywords) 2020–2025 | Total |

|---|---|---|

| ScienceDirect | Art, Community, Tourist, Interaction, Local | 2166 |

| Scopus | 22 |

| Cluster | Keywords |

|---|---|

| 1 | Community Engagement/Cultural Landscape |

| 2 | Social–Ecological Systems/Green Spaces |

| 3 | Communication/Social Media |

| 4 | Co-creation/Residents |

| 5 | Design/Innovation |

| 6 | Artistic Interventions/Social Sustainability |

| 7 | City Branding/Rural Revitalization |

| 8 | Artists/Sharing Economy |

| Journals/Authors | Details | Framework Connection |

|---|---|---|

| Activating rural infrastructures in regional communities: Cultural funding, silo art works, and the challenge of local benefit [10] | City-centric rural cultural policy often fails to meet local needs. This study, using narrative inquiry, analyzes Australian rural silo art (e.g., Silo Art Trail) to understand its economic, social, and cultural impacts on revitalization, aiming to inform context-responsive policy. It reveals that diverse creative objectives yield varied outcomes. | Validates Clusters 6–7 (Artistic Interventions/Rural Revitalization) by showing how public art transforms rural infrastructure into cultural assets. Supports community-responsive approaches yielding outcomes dependent on local engagement levels. |

| Exploring the perceptions and attitudes of residents at modern art festivals: The effect of social behavior on support for tourism [4] | Tourism research often overlooks resident social behaviors. This study surveyed 1207 residents on 12 Japanese islands following the 2016 Setouchi Triennale to understand perceptions of tourism and inform strategic planning. Results categorized residents into four exchange/support groups: high positive, high exchange/low support (due to negative experiences), smallest/negative, and low exchange/high support (economic understanding). | Provides empirical evidence for Clusters 1 and 4 (Community Engagement/Co-creation) through resident attitude analysis. Identifies four resident response categories, validating the importance of community perspectives in art-mediated tourism development. |

| Neo-endogenous revitalization: Enhancing community resilience through art tourism and rural entrepreneurship [9] | Global rural communities face decline, with limited research on cultural revitalization via arts festivals. This mixed-methods study on Setouchi Triennale islands explored how socially engaged art revitalizes communities, focusing on neo-endogenous mechanisms and small business roles. It found external art festivals spark diverse internal community responses, and successful revitalization requires long-term collaborative creativity between external art development and internal community operations. | Supports Clusters 2 and 6 (Social–Ecological Systems/Social Sustainability) by examining how art festivals create community development mechanisms. Demonstrates external art initiatives sparking internal community responses and long-term collaborative relationships. |

| Community cultural development: Exploring the connections between collective art making, capacity building, and sustainable community-based tourism [5] | Many industrial cities lack community-led sustainable tourism practices, risking resource extraction. This research explored cultural processes via interviews in Central Appalachia to develop a community representation model and policy approaches fostering shared identity. Findings confirm that community culture development enhances tourism potential and sustainability through increased local participation, partnerships, ownership, and dialogue. | Validates Clusters 4 and 6 (Co-creation/Artistic Interventions) by confirming that community culture development enhances tourism through increased local participation and ownership. Emphasizes collective art making and capacity building for sustainable tourism. |

| Analyzing and visualizing the spatial interactions between tourists and locals: A Flickr study in ten US cities [28] | Urban tourism creates shared spaces, but tourist–resident interaction patterns are unclear. This study used Flickr data (YFCC100M) in 10 major US cities to map spatial patterns and interactions. Results: tourists outnumbered residents 3–8×, yet residents uploaded more photos (NYC, San Francisco led). Photo volume correlated with attractions, and activity density varied significantly across urban areas for both groups. | Supports Clusters 3 and 5 (Communication/Innovation) by demonstrating digital platform applications for mapping tourist–resident interactions. Validates systematic analysis approaches for understanding collaborative processes in cultural tourism contexts. |

| Theories and Authors | Details |

|---|---|

| Value Co-creation [64] |

|

| Value Co-creation in Tourism Living labs [70] |

|

| Co-creating in Innovation for Sustainability [71] |

|

| Participative Co-creation [72] |

|

| Theories and Authors | Details |

|---|---|

| Artistic Interventions for Urban Innovation [84] |

|

| Artistic Intervention as Citizen Empowerment [85] |

|

| The Typology Theory of Political Artistic Interventions [86] |

|

| Artistic Intervention for Urban Emotional Well-Being [87] |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hanchotiphan, P.; Kasemsarn, K. Artistic Interventions as Urban Planning Tools: A Systematic Review of Community-Based Cultural Tourism in Cities. Urban Sci. 2026, 10, 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10020079

Hanchotiphan P, Kasemsarn K. Artistic Interventions as Urban Planning Tools: A Systematic Review of Community-Based Cultural Tourism in Cities. Urban Science. 2026; 10(2):79. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10020079

Chicago/Turabian StyleHanchotiphan, Pichamon, and Kittichai Kasemsarn. 2026. "Artistic Interventions as Urban Planning Tools: A Systematic Review of Community-Based Cultural Tourism in Cities" Urban Science 10, no. 2: 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10020079

APA StyleHanchotiphan, P., & Kasemsarn, K. (2026). Artistic Interventions as Urban Planning Tools: A Systematic Review of Community-Based Cultural Tourism in Cities. Urban Science, 10(2), 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10020079