Abstract

The integration of electric vehicles into urban life is currently being implemented rapidly. However, the excessive integration of electric cars into urban environments creates several risks that impede their sustainable development. In this regard, it is relevant to systematize the integration processes of electric cars supported by smart city tools. This study proposes a methodology for the sustainable development ecosystem of smart cities, enabling the measurement of both positive and negative results from the integration of electric cars, which can inform rational managerial decisions. This study utilized scientific abstraction approaches to establish a management framework for integrating electric vehicles into the smart city ecosystem. Comparative analyses of the impact of counterbalancing factors were conducted, and based on this, methodological approaches for determining the boundaries of the use of electric vehicles in smart cities were proposed.

1. Introduction

The lack of comprehensive urban planning, including smart city policies, is seriously undermining the quality of life of city dwellers [1]. Despite efforts to promote sustainable urban transport through electric vehicles, other factors have continued to affect urban living conditions [2]. In particular, Yerevan, a city of about one million people, has seen unprecedented construction of new residential buildings over the past ten years, and the prices, especially in the city center, have initially increased sharply due to high demand [3]. However, over the past two years, the rate of growth slowed significantly, and in some districts even a downward trend in prices has been recorded [4]. Currently, owners of apartments in the city center are trying to sell their apartments and move to more comfortable areas. Why has this happened, and what factors have contributed to this?

Transport emissions and traffic jams, lack of parking lots, and very loud traffic noise are significant contributors to poor air quality and high urban stress [5]. Moreover, in the last year, real estate taxes in central Yerevan have increased sharply, followed by an increase in municipal garbage collection fees [6], which are an additional burden on city dwellers.

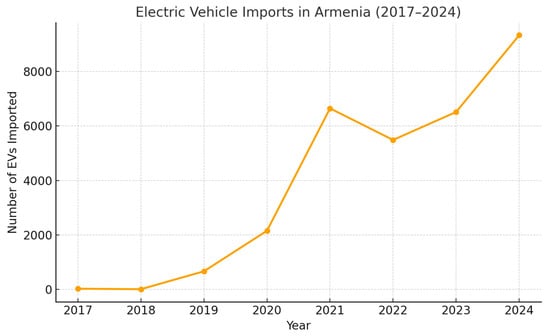

The cumulative pressures of traffic congestions, urban noise, and high living costs illustrate the challenges faced by Yerevan’s residents. Even initiatives to promote electric vehicle adoption—including free parking and import duty exemptions—according to which the number of electric vehicles in 2024 increased by 22% compared to the previous year [7], have not significantly improved the situation. This indicates that, without comprehensive smart city planning, these initiatives alone cannot sufficiently improve residents’ quality of life or the overall state of the city.

Management of sustainable urban development currently requires not only the use of ESG (environmental, social, governance) tools but also the maintenance of conceptual approaches to the formation of a smart city, which does not exclude the integration of electric vehicles into urban life [8]. If we theoretically imagine that a miracle occurs and urban transport is completely switched to electric engines, it would not solve the problems of sustainable urban development; instead, new issues would arise within the ESG framework, particularly regarding the insufficiency of the charging network, lack of parking lots, additional electricity supplies, and other factors [9]. The integration of electric vehicles into the urban environment requires special management approaches, considering the perspective of smart city management and the requirements of continuous sustainable development [10]. Moreover, shared management is implemented by including various groups of beneficiaries; an appropriate ecosystem is formed for this purpose, and the validity of decision-making aimed at the sustainable development of the urban environment with electric vehicles significantly increases [11].

The research is guided by the following central question: how can the integration of electric vehicles into the urban environment be systematically managed through a smart city ecosystem framework to balance their positive and negative impacts on sustainable development?

2. Materials and Methods

The economic effect of integrating electric cars is perceived differently in the professional literature. Some authors believe that, in this way, environmental problems are solved, greenhouse gas emissions and harmful waste from gasoline processing are reduced, and environmental damage from oil extraction is reduced [12]. However, even the professional literature emphasizes that electric cars are unable to solve the environmental problems completely; on the contrary, they create new environmental challenges [13]. And it turns out that in the case of large-scale use of electric cars, the problem of balancing the socio-economic consequences arises from it [14].

Moreover, the integration of electric cars into the traditional transport flow raises not only economic but also social issues, since in this case, drivers are offered several privileges by local authorities [15]. Thus, parking lots are offered free of charge for electric cars in many cities, and electric cars are allowed to enter some urban resort areas, since they do not emit greenhouse gases and are quiet [16]. There are also some privileges regarding financial obligations for the value-added tax when importing electric cars; in practice, privileges are also established for property taxes on electric cars [17]. Therefore, the widespread use of electric cars in the public sector may give rise to some social discontent [18].

The issue of supplying additional electricity required for charging electric vehicles is also a cause for discussion. If mass exploitation of electric cars happens, the demand for batteries of electricity supply will increase sharply [19]. And this, in turn, requires additional capacities of thermal power plants and therefore leads to additional emissions of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere from electricity production [20].

In the professional literature, the authors also point out that the production of electric cars for electric car exploitation requires additional amounts of non-ferrous metal mining, which directly has a negative impact on the environment, forming tailings and eroded land [21].

Therefore, the harm to the environment offsets the environmental benefits of electric car exploitation [22]. In this regard, the authors emphasize the importance of systematic assessments of the positive and negative socio-economic results of integrating electric cars into traditional vehicles [23]. Moreover, there is currently a need to make the process of integrating electric vehicles manageable, the capabilities of which are most evident in smart cities [24,25].

Thus, the authors believe that effective management of the process of integrating electric vehicles becomes more possible, especially in smart cities, since the issue of the measurability of monitoring indicators is solved here [26]. In smart cities, a system for controlling air pollution is continuously operated, and continuous information flows are ensured in this regard. With the same approach, the noise generated as a result of the exploitation of urban transport becomes measurable [27]. For smart cities to operate effectively, they require access to real-time or near real-time data generated from various urban systems, including street lighting, traffic signals, public transportation platforms, parking facilities, and congestion monitoring networks [28]. Smart intersections provide information on the density of transport flows and the need for measures to regulate congestion and offer solutions to unload the overloaded routes [29]. In this regard, the issues of managing the process of integrating electric vehicles in smart cities become not only necessary but also effectively feasible.

The research methodology was formed in a multi-layered manner. First of all, an analysis of the source literature related to urban sustainable management was carried out, aimed at recording the characteristics of such a direction of smart city regulations. Then, statistical information related to Yerevan city for the past few years was collected and analyzed to identify the risk indicators for urban life development from a sustainability viewpoint. Sociological surveys were also conducted among the beneficiaries of the urban life organization, from which the strengths and weaknesses of the city’s sustainability management were recorded by summarizing the collected information on integrating electric vehicles. A method to measure the beneficiaries’ expectations for the city’s sustainable management was developed and applied, which substantiated the effectiveness of developing urbanization through the integration of electronic vehicles.

- Current condition review

Integrating electric vehicles (EVs) into the transportation system is a key approach to sustainable development, offering significant environmental benefits like reduced emissions and fossil fuel dependence [30] while also contributing to economic growth through job creation and innovation [31]. The Republic of Armenia has no fossil fuel reserves; therefore, its energy demand is largely met by imported natural gas and liquid fuels. Nuclear energy accounted for more than 36% of the total electricity production in the republic. As of 2019, Armenia’s electricity is mainly produced in three types of plants: nuclear, hydro, and thermal, of which about 39% is in nuclear plants, with the remaining 60% almost equally in hydro and thermal plants.

Until 2028, Armenia plans to abandon thermal power plants and increase the share of hydropower to 40% (as a result of the construction of two large hydroelectric power plants: Shnogh on the River Debed and Meghri on the River Araks). During the same period, the share of nuclear energy is planned to increase to 40–42%. The remaining 18–20% is planned to be allocated to alternative energy sources, such as wind, solar, and biogas.

In the field of atmospheric air protection in the Republic of Armenia, the tax exemption for the import of vehicles with electric motors can be considered as a material incentive measure. Within its framework, from 1 July 2019, the import and alienation of vehicles with electric motors are exempt from VAT. From 17 March 2022, a customs privilege was established for the import of electric vehicles into the territory of the Republic of Armenia without paying the import customs duties. Electric cars in Yerevan are also exempt from local parking fees. Notably, parking fees for conventional cars have increased from the previous USD 24 to USD 415 in 2024. This is an additional economic incentive for society to give preference to EVs. As a result, from 2018 to 2024, 22,076 electric vehicles were imported into Armenia. According to the State Revenue Committee [32], in 2023, 86,531 vehicles were imported, of which 9635 were electric vehicles and in 2024, 31,955 vehicles were imported, of which 11,793 were electric vehicles.

In parallel, from April 2020 to 31 December 2021, by the decision of the EEC Council, the import customs duty rate of the Eurasian Economic Union’s Common Customs Tariff for certain types of vehicles with electric motors was zeroed. The above-mentioned VAT exemption period in the Republic of Armenia has been extended until 31 December 2026 [33]. The extension of the tax exemption is officially justified by the fact that it will contribute to ensuring the continuity of the recorded positive results and reducing air pollution, which is consistent with the goals of the green economy [34], as evidenced by the rapid growth of electric mobility in Armenia: the import of electric vehicles increased by more than 17 times between 2019 and 2024, as well as the national climate and energy goals aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 40% by 2030 and increasing the share of renewable and zero-carbon electricity to about 50% by 2030, where transport accounts for about 20% of national emissions, and the costs of air pollution are estimated at more than 10% of GDP [35].

In addition to reducing air pollution, the economic promotion of acquiring and operating electric vehicles is also important for the Republic of Armenia to implement its international obligations, in particular, the decision “On Approval of the National Actions of the Republic of Armenia for 2021–2030 under the Paris Agreement” [36], according to which the Government of the Republic of Armenia has committed to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions by 40 percent by the year 2030 compared with 1990.

Studies and analyses conducted by international organizations state that operating an electric vehicle, unlike vehicles with gasoline or diesel fuel, reduces CO2 emissions by an average of 4.6 tons per year [37].

Transport is a major contributor to global greenhouse gas emissions, accounting for approximately 12–15% of total emissions, with road transport accounting for the largest share within the sector, making it a significant polluter compared to other modes of transport [38]. The share of motor transport in atmospheric air pollution in the Republic of Armenia is reaching a fairly high level and has fluctuated around 70% recently. In 2017, Armenia’s total greenhouse gas emissions were approximately 10.2 Mt CO2-eq., of which 66.7% was the share of the energy sector, and greenhouse gas emissions from road transport amounted to 24.8% of the total emissions [39]. Projections show that greenhouse gas emissions from the transport sector will continue to grow until 2030, and if current trends persist, the transport sector will become one of the largest sources of energy-related emissions [40].

As of 1 September 2025, there were 953,965 registered motor vehicles in the Republic of Armenia, of which about 36% are in the capital. Moreover, out of 343,220 vehicles registered in Yerevan, about 88% are light passenger vehicles. That is, about 36% of the total vehicle fleet registered in the Republic of Armenia are light passenger vehicles, and they are in the capital [41].

According to the information provided by the RA Traffic Police, regular- or fast-charging points are installed in or near the registered settlements of about 90 percent of electric vehicles (3119 units). According to plugshare.com, the total number of charging points installed in Armenia as of January 2024 is 198 (159 (80%) regular, 39 (20%) fast). The number of charging stations installed in places accessible to the public is 177 (138 (78%) regular, 39 (22%) fast); only 68 (51 (75%) regular, 17 (25%) fast) are in the capital. On average, one charging point in the places accessible to the public in Armenia accounts for 22 electric vehicles. If we take into account only the fast-charging points, this figure is equal to 138. The number of registered electric vehicles in the Kentron and Arabkir administrative districts alone is 579 and 430 units, respectively, and the number of charging points in public places is 19 (8 are quick) and 8 (1 is quick). Therefore, it is estimated that there are approximately 31 electric vehicles per charging point in the Kentron district and 54 electric vehicles per charging point in the Arabkir district. It should be noted here that, according to surveys (see Appendix A), owners of electric vehicles mainly charge their cars at home; on the one hand, it is economically beneficial, but on the other hand, public charging points are insufficient, especially in settlements outside the capital.

To date, there are no legislative and legal regulations on the installation and operation of charging infrastructure or technical and safety requirements [42], while the import of electric cars to Armenia has been recording unprecedented growth in recent years (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Growth of electric vehicle imports in the Republic of Armenia (RA). Source: Armenian Statistical Yearbooks; 2018–2025 [43].

It is noteworthy that in the context of the Armenian vehicle market, electric vehicles, even with current VAT and customs duty exemptions, remain more expensive than comparable internal combustion engine vehicles. A recent analysis shows that new electric models are approximately USD 10,000–12,000 more expensive than similar conventional vehicles, and current market prices typically range from USD 20,000 to USD 45,000, depending on the make and condition, reflecting the ongoing gap in upfront costs despite financial incentives [44]. On the other hand, most licensed car dealers in Armenia still do not have an official license to sell and service electric vehicles, making the prices offered by individuals relatively competitive in the market [45].

3. Results

About one-third of the 3 million population of the Republic of Armenia is concentrated in the city of Yerevan, and the city center is considered the most densely populated territorial unit (see Table 1). Naturally, the high population density creates challenges for city management, particularly regarding sustainable development, as it leads to increased motor transport use, higher air pollution from carbon emissions, more traffic jams, and elevated street noise.

Table 1.

Overall characteristics of district communities in Yerevan for 2023 *.

Statistics show that Yerevan city accounts for about 50% of the Republic’s freight transportation, 75% of road transport, and 62% of the total truck mileage (see Table 2), which makes it relevant to manage the movement of motor vehicles using smart city conceptual approaches in such a way that does not disrupt the sustainable development of urbanization.

Table 2.

Dynamics of transportation delivery indicators in the city of Yerevan *.

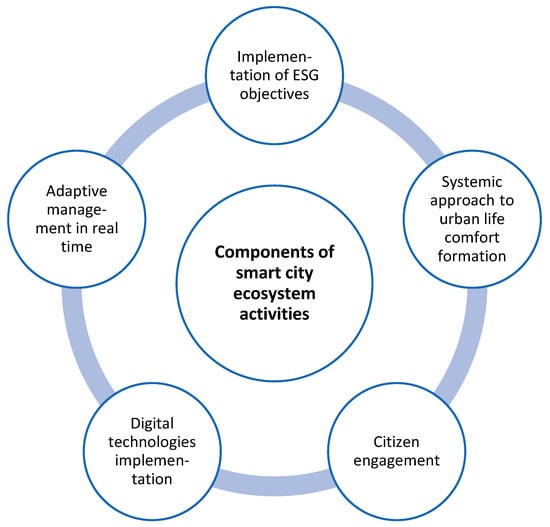

Urbanization management with sustainable development approaches implies first the definition of the components of smart city activities and clarification of operational objectives within the framework of the ecosystem (see Figure 2). The ecosystem is important here, since the key components of a smart city must operate in a coordinated and harmonized manner within the framework of the system, establishing a balance in a sustainable development environment with their positive and negative impacts [47].

Figure 2.

Key directions for the formation and operation of a smart city ecosystem.

A smart city works by integrating digital technology, particularly the Internet of Things (IoT) and artificial intelligence (AI), to collect and analyze real-time data from the sensors across the urban environment. This data is used to optimize city functions like traffic, energy management, and waste disposal, improving the efficiency, sustainability, and overall quality of life for residents [48]. The process involves data collection, analysis to gain insights, communication of these findings, and taking action to enhance services and infrastructure.

Thus, the development of urbanization cannot fail to take into account additional emerging environmental problems (sorting and recycling of household waste, prevention of motor vehicle congestion, use of alternative energy, effective organization of water supply and drainage, etc.), which are solved by the use of electronic monitoring technologies and adaptive management in real time [49]. Electronic sensors and the recording devices installed in every corner of the city provide information on congestion at intersections, the state of garbage collectors, traffic jams, parking lot capacity, street noise, and air pollution, which receive real-time adjustments from adaptive management (see Figure 2).

This process also includes solutions to the integration problems of electric cars when additional charging points are required, thus adding electricity supplies to the city [50]. Here, the importance of meeting the requirements of a smart city in the management ecosystem is also emphasized when conditions are created for charging electric cars in apartment parking lots, which is a serious problem, especially in Yerevan, since the parking lots allocated to the newly built residential buildings are not adequate to satisfy the demand of the inhabitants, and the old buildings do not have parking lots at all. That is why charging electric cars currently creates a certain inconvenience among drivers, which contradicts the principles of a smart city. To substantiate this claim, a survey was conducted within the framework of the research, the purpose of which was to identify the real motives for buying electric cars (see Appendix A). Thus, about 87 citizens participated in the survey, 67 of whom drive electric cars. Out of 67 citizens, 59 charge their cars at home. This data indicates that charging cars at charging points is about four times more expensive than at home; in addition, charging points are insufficient both in Yerevan and outside the city. The primary motivation for purchasing an electric car was economic factors, particularly fuel economy (cited by about 90% of respondents) and state incentive programs (mentioned by 45%), while only 35% cited environmental protection as a reason. This fact states that the level of green thinking among the population is quite low.

It should also be noted that the integration of electric vehicles in Yerevan is currently being carried out mainly as personal vehicles, bypassing public transport, which creates an additional social problem in sustainable development. It is not a secret that the acquisition of electric vehicles is nowadays relatively expensive compared to traditional transport vehicles, and commuting by trams, trolleybuses, and electric buses requires fairly cheap fares. Thereby, monitoring of electric and traditional vehicles in a smart city should be conducted not only to optimize the flow of passenger transport but also to improve the social condition of city residents.

The management of the ecosystem of a smart city should balance the environmental damage of the electricity production consumed by electric engines with the generated eco-benefits. If the electricity supplied to the city is produced with fuel oil or coal, the thermal power plants produce more greenhouse gases and cause more harm to the environment than the benefits of preventing air pollution from the operation of electric cars [51]. Therefore, in the smart city management ecosystem, the direct environmental benefits and indirect harms arising from the use of electric cars are monitored by the implementation of digital technologies (IoT).

Moreover, non-ferrous metals are used in the production of electric car batteries; their intense extraction causes significant harm to the environment, since mining is carried out in an open way [52]. Consequently, producing non-ferrous metals for electric cars leads to the creation of tailings dumps and land desertification, both of which are indirect harms associated with electric vehicles [53].

In smart cities, a similar monitoring requirement arises concerning the waste related to the operation of electric cars. Disused electric batteries are harmful waste for the environment and require ecosystem management. Therefore, we should also consider the feasibility of operating electric cars in smart cities from the perspective of waste management [54].

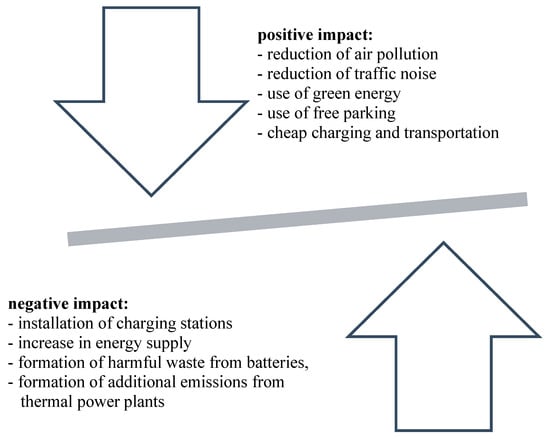

Thus, the integration of electric vehicles in smart cities requires an ecosystem approach to management, balancing the opportunities for sustainable city development resulting from the use of electric cars and the risks counteracting them [55]. In this regard, it is relevant to balance the obstacles and opportunities for smart city sustainable development from using electric cars (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Counterbalancing factors of positive and negative impact of electric cars on sustainable development of urban environment.

Problems also arise when evaluating the effects of these obstacles and opportunities with specific indicators (see Table 3). Smart cities use digital technologies, combining Internet of Things (IoT) and artificial intelligence (AI) systems, to provide the results of such an evaluation. Moreover, depending on the management goals of the smart city, these indicators of opportunities and obstacles may undergo revisions over time, either increasing or decreasing.

Table 3.

Directions and nature of the impact of electric vehicles on the sustainable development of a smart city.

We propose a method to assess the outcomes of integrating electric vehicles into the sustainable development ecosystem of urban environments, making both the feasibility and speed of this integration measurable.

Thus, smart cities provide a way to measure the real-time impact of specific factors on sustainable development, whether that impact is positive or negative. And if the sum of positive impacts exceeds the sum of negative impacts (ΣA/ΣD > 1.0), progress in the development of sustainability is recorded, and vice versa (see Table 3). And it is not necessary that the number of positive and negative factors is always equal; what is more important here is that the sum of the effects of positive factors ΣA exceeds the sum of the effects of negative factors ΣD.

Thus, the proposed approach to assessing the integration of electric vehicles for sustainable development in the long run represents the speed of this process, which is an important indicator in managing the development of smart cities. If the ΣA/ΣD index shows a yearly trend with values of 1.1, 1.15, and 1.2, it indicates an acceleration in the impact of electric vehicles on the sustainable development of the city. Conversely, if the ΣA/ΣD index continuously decreases from year to year over time, as a result, a regress of sustainability is recorded.

Some limitations must be applied, taking into account the vehicle capacity of the smart city streets, which is considered in terms of the urban population (S) and the number of vehicles associated with it (Q). If we assume that a city can have a maximum of 600 private cars per 1000 residents, then the following functional requirements should be met: the positive overall outcomes of electric vehicle operation should outweigh the negative outcomes to the greatest extent possible.

- -

- The number of electric vehicles (Q) should be limited to 600 cars per 1000 residents.

The results obtained will play an important role in regulating the processes of integration of electric vehicles in terms of smart city ecosystem management in such a way that the risks hindering sustainable development are prevented as much as possible and the benefits from the exploitation of green transport are maximized. Thus, in practice, the F function cannot be maximized indefinitely because increasing electric vehicles on city streets may have limitations. Most importantly, they exhibit minimal indirect negative effects that cannot be completely neutralized. However, the integration of electric vehicles becomes manageable from a sustainable development perspective because the parameters a, d, and S continuously change based on signals from the smart city. This constant monitoring of the F function’s value necessitates urgent management decisions when decreasing trends are recorded. Thus, certain requirements can be presented for the positive and negative aspects of the exploitation of electric vehicles, such as

- -

- ESG requirement per unit of electric vehicle

- -

- City planning objective taking into account the ESG requirement: integrate at least 0.5 million vehicles

Or

from which

Considering the components of ecosystem management, we will have the following system of inequalities, by which the min and max limits of the integration of electric vehicles will be calculated:

If the smart city changes ESG requirements regarding a unit electric car like this

And also, the municipality proposed to review its goals in this direction

then the minimum point will shift to the left because the parameters of the inequality system will change, and adaptive management will adjust the integration limit for electric vehicles.

4. Discussion

The need for ecosystem management regarding the integration of electric vehicles into urban environments arises from the objectives of sustainable development. Moreover, the management of integration processes is most effectively implemented, especially in the conditions of a smart city, when management decisions are made not only promptly, on a real-time basis, but also as a result of complex analysis.

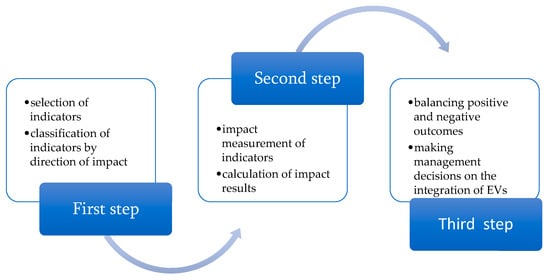

We propose to implement decision-making on the integration of electric vehicles in a regulated stepwise manner (see Figure 4). The first step is to select indicators that relate to the causal results of the integration of electric vehicles. Moreover, the scope of the selection of indicators can be diverse, covering various aspects related to environmental, social, and sustainable development. The passage also emphasizes how these indicators characterize the process of sustainable development in cities related to the integration of electric vehicles. Therefore, we classify the selected indicators at this stage of the management process based on their positive and negative impacts on sustainable development.

Figure 4.

Decision-making process for electric vehicle integration.

When making management decisions related to the process of integrating electric vehicles, it is important to implement reasonable measurements of indicators included in the framework of ecosystem management (see Figure 4). These measurements are based on the collection and processing of data from the smart city monitoring tools, as well as the results of the assessment of AI’s extraction. The measurements rely on quantitative data regarding the integration of electric vehicles, as well as qualitative indicators that emerge from their operation in relation to the city’s sustainable development.

We propose to conduct the final stage of the decision-making process regarding the integration of electric vehicles by weighing positive and negative outcomes for the sustainable development of cities, based on functionally related assessments of both the effectiveness of this integration and its timely acceleration. Such an approach makes the process of integrating electric vehicles in the smart city environment manageable, which in turn plays a decisive role in the favorable course of the sustainable development of the city.

5. Conclusions

The importance of integrating electric vehicles into urban transport needs to be assessed in a comprehensive manner, especially when it occurs in smart cities.

First, the operation of electric vehicles should not be considered solely as a sustainable development tool, as it is also accompanied by negative environmental and social consequences. Therefore, especially in smart cities, it is possible to obtain an information base that will allow measurements to be made of both negative and positive results arising from the operation of electric vehicles.

Second, the process of operating electric vehicles is accompanied by quantitative limitations, which should also be taken into account when assessing the efficiency of the operation of these vehicles. Therefore, it becomes advisable, especially in smart cities, to use decision-making mechanisms with comprehensive information sources that will contribute to the effective integration of electric vehicles into the urban transport system.

Third, the integration of electric vehicles also requires monitoring of various results arising from their operation, which can also be implemented in the case of smart cities. In the case of monitoring, counterbalances are created for the various consequences of the operation of electric vehicles, which makes it possible to regularly improve the integration process.

Limitations

We would also like to state that our methodology for managing the integration of electric vehicles into the urban environment cannot be considered complete, and it needs further research in improved directions. First of all, it is important to develop a methodology for substantiating the framework of indicators for assessing integration. Here, a special toolkit for the complex analysis of urban environment changes is required (for example, Urban Design Climate Workshop (UDCW) toolkits which can be applied to evaluate the impacts of interventions such as electric vehicle adoption as part of broader sustainability strategies [56]) to ensure the recording of changes in the sustainable development of the city due to the use of electric vehicles.

In addition, the validity of the measurements of the selected indicators is important, since they have both an environmental and economic and social nature [57]. Therefore, here too, a special algorithm should be developed for artificial intelligence so that the latter can timely and correctly perceive the resulting consequences of the integration of electric vehicles on the process of sustainable development of a smart city. Therefore, the effective implementation of AI tools requires not only technological capabilities but also robust governance mechanisms [58].

Finally, further research is needed to create an ecosystem management framework that integrates electric vehicles into the urban environment and clarifies the centers of responsibility for management decisions, ensuring they work harmoniously together in alignment with the goals of the public, the state, and private beneficiaries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.K. and A.T.; methodology, A.T. and A.H.; formal analysis, N.M.; resources, N.K. and A.H.; data curation, I.A. and N.M., writing—original draft preparation, N.K. and A.T.; writing—review and editing, N.K. and A.T.; visualization, I.A.; supervision, N.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study by the Faculty of Economics and Management of Yerevan State University given the non-sensitive nature of the questions and the explicit ethical and confidentiality safeguards provided to participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. The survey link is as follows: https://forms.gle/wzQqLcsw7Tx8BcHVA (accessed on 20 August 2025).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript the authors used ChatGPT powered by GPT-5.2; Open AI (San Francisco, CA, USA, 2026; Available online: https://chat.openai.com, accessed on 6 January 2026) for the purposes of grammatical correction and stylistic improvement of select text fragments, and for finding the most relevant articles for our research. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. The authors thank the editors and reviewers for their valuable comments, which led to the improvement of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

- Survey

This survey is conducted within the framework of a scientific research study and aims to examine the motivations behind automobile purchases, as well as to identify potential issues arising during their use and maintenance.

We inform you that the survey results will be used exclusively for scientific purposes and will be published in an international scientific journal, with strict adherence to the principles of research ethics, as well as the confidentiality and anonymity of participants’ personal data. If you agree with these conditions, please proceed to answer the questions.

Thank you for your time, participation, and support!

- Questions:

- Age group.

- How many people live in your household (including yourself)?

- How many children do you have under your care?

- How many members of your household work?

- Place of permanent residence.

- Place of your work.

- Education level.

- Your field of employment

- If you choose other, please specify.

- What is your family average monthly income?

- What type of housing do you live in?

- What engine do you drive?

- How many kilometers do you drive on average per month?

- Is it possible that your next vehicle will be electric or hybrid?

- What was the main motivation for purchasing petrol or diesel vehicle (you can choose several options)?

- “If you drive a petrol or diesel vehicle, please do not continue answering the following questions, as they are intended for electric or hybrid vehicle owners. Kindly scroll to the bottom of the page and click ‘Submit’ to record your responses. Thank you for your support!”

- What was the main motivation for purchasing an electric or hybrid car (you can choose several options)?

- What price range is your electric or hybrid car in?

- Where do you usually charge your car?

- How do you estimate the operating costs of your car?

- What difficulties have you encountered when using an electric or hybrid car (you can choose several options)?

References

- Chang, S.; Smith, M.K. Residents’ Quality of Life in Smart Cities: A Systematic Literature Review. Land 2023, 12, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilly, N.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Degimenci, K.; Paz, A. How sustainable is electric vehicle adoption? Insights from a PRISMA review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 117, 105950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manukyan, A. Analysis of the Real Estate Market in Armenia 2025. Grant Thornton Armenia. 2025. Available online: https://www.grantthornton.am/insights/articles/analysis-of-the-real-estate-market-in-armenia-2025/ (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- ARKA News Agency. Armenian real estate market records slower price growth in December 2024—Ministry of Finance. ARKA News Agency. 4 February 2025. Available online: https://arka.am/en/news/economy/armenian-real-estate-market-records-slower-price-growth-in-december-2024-ministry-of-finance/ (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Morawetz, U.B.; Klaiber, H.A.; Zhao, H. The impact of traffic noise on the capitalization of public walking area: A hedonic analysis of Vienna, Austria. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 353, 120060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ARKA. Yerevan Residents Exempted from Fines for Late Payment of Garbage Collection Fees in January–April—City Hall. ARKA News Agency. 2025. Available online: https://arka.am/en/news/economy/yerevan-residents-exempted-from-fines-for-late-payment-of-garbage-collection-fees-in-january-april-c/ (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Armenpress Armenian News Agency. Armenia Extends VAT Exemption as Electric Vehicle Imports Continue to Surge. Armenpress. 16 October 2025. Available online: https://armenpress.am/en/article/1232286 (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Shao, J.; Min, B. Sustainable development strategies for Smart Cities: Review and development framework. Cities 2025, 158, 105663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo-Bosch, F.; Pujadas, P.; Morton, C. Sustainable deployment of an electric vehicle public charging infrastructure network from a city business model perspective. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 71, 102957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apata, O.; Bokoro, P.N.; Sharma, G. The Risks and Challenges of Electric Vehicle Integration into Smart Cities. Energies 2023, 16, 5274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulhim, A.I.; Yigitcanlar, T. Understanding Smart Governance of Sustainable Cities: A Review and Multidimensional Framework. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirmana, V.; Alisjahbana, A.S.; Yusuf, A.A.; Hoekstra, R.; Tukker, A. Economic and environmental impact of electric vehicles production in Indonesia. Clean. Techn. Environ. Policy 2023, 25, 1871–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmiroli, B.; Messagie, M.; Dotelli, G.; Van Mierlo, J. A review of the life cycle assessment of electric vehicles: Environmental impact and challenges. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 814, 152870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Kumar, L.; Islam, M. A comprehensive review on the integration of electric vehicles for sustainable development. J. Adv. Transp. 2022, 2022, 3868388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajepour, A.; Song, J. A comprehensive review of the key technologies for pure electric vehicles. Energy 2019, 182, 824–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witlox, F.; Wang, Y. Global trends in electric vehicle adoption and the impact of environmental awareness, user attributes, and barriers. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 1125–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Ou, R.; Xiao, X. Regional comparison of electric vehicle adoption and emission reduction effects in China. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 149, 714–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Magee, C. Technological development of key domains in electric vehicles: Improvement rates, technology trajectories and key assignees. Appl. Energy 2020, 260, 114264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ma, M.; Zhou, N.; Deng, Y.; Liu, J. Impact of electric vehicle charging demand on clean energy regional power grid control. Energy Inform. 2025, 8, 83. [Google Scholar]

- Gai, Y.; Wang, A.; Pereira, L.; Hatzopoulou, M.; Posen, I.D. Marginal greenhouse gas emissions of Ontario’s electricity system and the implications of electric vehicle charging. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 7903–7912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Ismael, M.; Reed, M.; Elkarmoty, M. Overview on the Mining Environmental Impact of Electric Vehicles Batteries Production. Min. Rev. 2025, 31, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Saad Alam, M.; Saad Alsaidan, I.; Shariff, S.M. Battery swapping station for electric vehicles: Opportunities and challenges. IET Smart Grid 2020, 3, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacenti, E.; Perboli, G.; Musso, S. A Systematic Review on Sustainability Assessment of Electric Vehicles: Knowledge Gaps and Future Perspectives. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 97, 106867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, L.; Tribioli, L.; Cozzolino, R.; Bella, G. Comparative environmental assessment of conventional, electric, hybrid, and fuel cell powertrains based on LCA. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2017, 22, 1989–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nienhueser, I.A.; Qiu, Y. Economic and environmental impacts of providing renewable energy for electric vehicle charging—A choice experiment study. Appl. Energy 2016, 180, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, M.; Handschuh, N.; Rieke, C.; Kuperjans, I. Contribution of country-specific electricity mix and charging time to environmental impact of battery electric vehicles: A case study of electric buses in Germany. Appl. Energy 2019, 237, 618–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Khan, Z.A.; Saad Alam, M.; Khateeb, S. A review of the electric vehicle charging techniques, standards, progression and evolution of EV technologies in Germany. Smart Sci. 2018, 6, 6–53. [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo, V.; Baptista, G. Electric Vehicles Sustainability and Adoption Factors. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, A.; Wei, Y.; Chen, W.; Peng, N.; Peng, L. Life cycle environmental impacts and carbon emissions: A case study of electric and gasoline vehicles in China. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 65, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umair, M.; Hidayat, N.M.; Abdullah, E.; Hakomori, T.; Ahmad, A.S.; Nik Ali, N.H. A review on electric vehicles: Technical, environmental, and economic perspectives. J. Sustain. Dev. Energy Water Environ. Syst. 2025, 13, 1130568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefin, A.A.; Meraj, S.T.; Lipu, M.S.H.; Rahman, M.S.; Rahman, T.; Hasan, K.; Sarker, M.R.; Muttaqi, K.M. Societal, environmental, and economic impacts of electric vehicles towards achieving sustainable development goals. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 107060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Revenue Committee of the Republic of Armenia. Vehicle Imports to the Republic of Armenia in 2023. Association of Official Representatives of Automakers (AORA). Available online: https://www.aora.am/en/news/103 (accessed on 8 January 2026).

- ARKA News Agency. Armenia Extends Tax Exemptions for Newly Imported Electric Vehicles. 16 October 2025. Available online: https://arka.am/en/news/business/armenia-extends-tax-exemptions-for-newly-imported-electric-vehicles/ (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Framework Action Programme for the Development of Green, Sustainable and Circular Economy (Until 2030). Prime Minister’s Decision No. 1028-Լ, Armenian Legal Information System (ARLIS). Available online: https://www.arlis.am (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- World Bank. Climate Action in Armenia Can Deliver Cleaner Air, Healthier Communities, and Stronger Economic Growth. 2024. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Republic of Armenia. Nationally Determined Contribution of the Republic of Armenia for 2021–2030. UNFCCC. 2021. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/NDC/2022-06/NDC%20of%20Republic%20of%20Armenia%20%202021-2030.pdf?utm (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- EPA. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from a Typical Passenger Vehicle; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/greenvehicles/greenhouse-gas-emissions-typical-passenger-vehicle (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Statista Research Department. Transportation emissions Worldwide–Statistics & Facts; Statista: New York, NY, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/7476/transportation-emissions-worldwide (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Sekoyan, T. Greenhouse Gas Emission Dynamics in Different Spheres of Economy in Armenia; EcoLur: Yerevan, Republic of Armenia, 2021; Available online: https://www.ecolur.org/en/news/climate-change/13056 (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- UNECE. Scenario Highlights for the Republic of Armenia. Draft. 2024. Available online: https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2024-05/NEXSTEP%20Armenia%20Scenario%20Highlights%20Draft.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2026).

- Gharabegian, A. Transportation Modes in Armenia; Armenian National Committee of America: Glendale, CA, USA, 2015; Available online: https://anca.org/transportation-modes-in-armenia/ (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Chambers and Partners. Sustainability Developments in Armenia: Armenia’s Quest for Green E-Mobility; Chambers Expert Focus: London, UK, 2025; Available online: https://chambers.com/legal-trends/armenias-quest-for-green-e-mobility (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Statistical Committee of the Republic of Armenia. Statistical Yearbook of Armenia 2025; Retrieved 17 January 2026. Available online: https://armstat.am/en/?nid=586&year=2025 (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Global Environment Facility. CEO Endorsement Request: Transition Towards Electric Mobility in Armenia; Global Environment Facility: Washington, DC, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.thegef.org/sites/default/files/documents/10280_CEO_Endorsement_request.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Mgdesyan, A. Armenia approves duty-free import quotas for electric vehicles in 2025. Business Media. 28 November 2024. Available online: https://bm.ge/en/news/armenia-approves-duty-free-import-quotas-for-electric-vehicles-in-2025 (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Statistical Committee of the Republic of Armenia. Yerevan City of the Republic of Armenia in Figures. 2024. Available online: https://armstat.am/file/doc/99553323.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Onat, N.C.; Kucukvar, M.; Aboushaqrah, N.M.; Jabbar, R. How sustainable is electric mobility? A comprehensive sustainability assessment approach for the case of Qatar. Appl. Energy 2019, 250, 461–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, H.; Zhu, L. Factors influencing the economics of public charging infrastructures for EV—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 94, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanaki, E.A.; Koroneos, C.J. Comparative economic and environmental analysis of conventional, hybrid and electric vehicles—The case study of Greece. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 53, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagcitekin, B.; Uzunoglu, M.; Karakas, A.; Erdinc, O. Assessment of electrically-driven vehicles in terms of emission impacts and energy requirements: A case study for Istanbul, Turkey. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 96, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Ahmad, A.; Shafaati Shemami, F.; Saad Alam, M.; Khateeb, S. A comprehensive review on solar powered electric vehicle charging system. Smart Sci. 2018, 6, 54–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.; Ahmad, F.; Panigrahi, B.K.; Al-Fagih, L. A comprehensive review on advanced charging topologies and methodologies for electric vehicle battery. J. Energy Storage 2022, 53, 105084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, S.; Kamran, M.; Rashid, U. Impact analysis of vehicle-to-grid technology and charging strategies of electric vehicles on distribution networks—A review. J. Power Sources 2015, 277, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, H.S.; Rahman, M.M.; Li, S.C.W.; Tan, C. Electric vehicles standards, charging infrastructure, and impact on grid integration: A technological review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 120, 109618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, C.Q.; Keyvan-Ekbatani, M.; Ngoduy, D.; Watling, D. Dynamic wireless charging lanes location model in urban networks considering route choices. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2022, 139, 103652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, J.; Smith, L.; Chen, M.; Patel, R. Urban design climate workshop: Toolkits to bridge climate science, governance, and community needs. Front. Sustain. Cities 2025. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/sustainable-cities/articles/10.3389/frsc.2025.1666752/full (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Zheng, J.; Sun, X.; Jia, L.; Zhou, Y. Electric passenger vehicles sales and carbon dioxide emission reduction potential in China’s leading markets. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkhitaryan, K.H.; Sanamyan, A.; Mnatsakanyan, M.; Kirakosyan, E.; Ratner, S. Integrating AI and Geospatial Technologies for Sustainable Smart City Development: A Case Study of Yerevan. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.