Abstract

The scientific literature has explored the relationship between environmental justice and inequalities in the distribution and access to green spaces. This article analyses the neighbourhood of La Verneda (Barcelona) as one of the most successful cases of ecological urban transformation in Spain. Based on a Communicative Methodology approach that includes five in-depth dialogic interviews with residents and documentation from local institutions, the analysis identifies four core mechanisms driving the transformation: dialogic capacity building (through an adult education school), grassroots coalition-building (VERN and local associations), intergenerational design choices (spaces intentionally designed for mixed-age use), and symbolic place-claims (defense of the name La Verneda). These mechanisms contributed to measurable environmental and social outcomes reported by residents and illustrate how bottom-up processes can reconfigure urban planning trajectories. These findings contribute relevant lessons for contemporary ecological transitions in other urban peripheries.

1. Introduction

Globally, there is an accelerated process of urbanization; it is projected that by 2050, approximately 68% of the world’s population will live in urban areas [1]. This trend highlights the importance of advancing towards Sustainable Development Goal 11, which promotes the development of safe, inclusive, and sustainable cities and human settlements as a crucial strategy for reducing social inequalities and improving health.

From a historical perspective, cities are not neutral or static settings, but rather spaces that have been shaped by political decisions, planning practices, and social processes accumulated over time. Historical patterns of formal and informal segregation have left a legacy that manifests itself, for example, in the unequal distribution of environmental burdens: the location of polluting industries, the presence of urban heat islands, or differential vulnerability to flooding, as in the case of Baltimore [2]. The academic literature has extensively documented how socioeconomic segregation and historical zoning have relegated low-income communities and minorities to live in the most vulnerable areas of the city [3,4,5]. In order to comprehend the manner in which these structural pressures manifest in daily life, it is imperative to transition from the urban scale to the neighbourhood scale. The neighbourhood is the level at which the dynamics of segregation, inequality, and differential access to urban resources materialise in concrete social practices and specific living conditions.

There is no universally accepted definition of what constitutes a neighbourhood. However, some scholars synthesise a range of perspectives and posits that the concept can be understood in three distinct ways: firstly, as a physical space where residents establish a sense of belonging that impacts their social identity and quality of life; secondly, as a community where bonds of solidarity and cohesion are formed around shared interests and practices; and thirdly, as a political unit, conceived both as a forum for consultation in public decision-making processes and as a setting for collective activism in the face of government impositions [6].

Consequently, the concept of a neighbourhood encompasses more than the mere aggregation of its streets and buildings; it constitutes a social ecosystem wherein bonds are forged and collective memories are constructed. A substantial body of research has documented the impact that place of residence has on people’s health and well-being [7,8,9]. In the area of analysis, it can be observed that the determination of quality of life in communities is influenced by various factors, including the availability of services, the quality of infrastructure, community cohesion, and the perception of safety [10].

Given the significant impact that place of residence has on the quality of life of its inhabitants, various urban transformation initiatives have been developed in recent decades to improve the social, environmental, and spatial conditions of cities. These interventions are deployed on different scales: from specific projects on plots of land or in public spaces, such as the conversion of hard plazas into green areas or community meeting places, to more far-reaching plans in neighbourhoods. Notable international examples include the High Line in New York, a 2.3 km linear park built on a former railway line and jointly managed by the city and the community organisation Friends of the High Line [11]; the Atlanta Beltline, which aims to convert over 35 km of railroad tracks into a continuous green belt connecting numerous neighbourhoods by 2030 [12]; and the Superblocks of Barcelona, where traffic reorganisation seeks to reclaim public space by transforming inner neighbourhood streets into pedestrian areas with additional green spaces, playgrounds and benches. This creates an inviting environment for people to socialise and fosters new meeting points for neighbours [13]. Also noteworthy are the EcoQuartiers in France, which transform entire neighbourhoods by incorporating community parks and gardens [14]. These cases demonstrate the increasing investment by cities worldwide in reclaiming hardened urban spaces and reintegrating them into the natural environment.

The benefits associated with urban green spaces have been extensively documented. At the individual level, they promote physical and mental health by reducing stress and encouraging physical activity [15,16]. Furthermore, they act as a safeguard against air pollution, thereby mitigating the risk of respiratory diseases [17,18]. At the community level, these spaces have been shown to have a positive effect on socialisation and well-being [19]. At the environmental level, they mitigate the urban heat island effect [20] and contribute to the climate resilience of cities [21]. The World Health Organization’s report “Urban green spaces and health” summarizes these multiple benefits and, crucially, underscores the importance of ensuring equitable distribution. As part of its recommendations, the WHO proposes that each residence be located within a maximum distance of 300 m from a green space of at least 0.5 hectares to maximize its benefits [22].

Despite the extensive documentation of these benefits, various studies demonstrate that the implementation of urban greening projects does not guarantee social equity. Conversely, these initiatives have the potential to perpetuate or intensify existing disparities. This pattern of inequality is directly linked to purchasing power, which manifests itself as clear environmental injustice. In many cases, the design and implementation decisions follow a top-down approach, driven by municipal authorities, planners, or investors and guided by technical assessments, ecosystem service valuations, public health data, or real estate projections, while bottom-up participation from residents, especially the most vulnerable, remains limited [23]. Such top-down planning often prioritizes economic growth and aesthetic improvements over the lived experiences of long-standing communities.

Projects such as the High Line in New York [24] and the Atlanta Beltline [25] have shown how urban greening can be associated with gentrification processes and an increase in property values, a dynamic that has also been documented in Barcelona [26]. This pattern of inequality is observed in multiple urban contexts worldwide. For instance, in Shanghai, wealthier neighbourhoods have significantly greater access to these spaces [27], whereas in Tartu and Faro, ethnic minorities and residents of older neighbourhoods have reduced access [28]. A similar trend has been observed in Oslo, where environmental risks are unevenly distributed, affecting these communities more [29]. The lack of green spaces in peripheral neighbourhoods exacerbates the effects of the urban heat island, as documented in Khenchela [19]. Furthermore, the current real estate market in cities such as Melbourne [30] also contributes to unequal access to these spaces. In Istanbul, green infrastructure is limited to long-term state-backed projects, which generate cooling benefits primarily for residents of new buildings, while the surrounding areas remain more exposed to urban heat [31].

These cases show that greening policies, far from being universally beneficial, can reinforce existing inequalities. Yet, it is important to remember that green spaces have proven potential to improve health and well-being. The problem lies not in their existence, but in their distribution and accessibility: when they are concentrated in privileged areas, they generate exclusion; when they are public and of high quality, they become a protective resource for the most vulnerable groups [32]. This shows that not only quantity, but also quality, accessibility, and type of green space are crucial to ensuring their social function. However, ensuring these conditions does not depend solely on urban design, but also on the ability of communities to influence planning processes. In this sense, community mobilization, such as that observed in Barcelona’s Casc Antic, becomes a key mechanism for resisting gentrification and promoting more democratic and equitable urban planning, in which the voice of residents is fundamental to revitalization without displacement [33].

However, despite extensive research on environmental justice and urban inequality, a gap remains regarding the dynamics that unfold in historically working-class neighbourhoods that have been excluded from mainstream urban planning debates. Few empirical studies have examined how bottom-up ecological transformations emerge in such contexts or how residents themselves conceptualize environmental justice through their everyday practices. This study directly addresses that gap by exploring La Verneda as a working-class neighbourhood that redefined its environment through collective agency. In this sense, the present case study analyses the ecological transformation of the La Verneda–Sant Martí area, which comprises two neighbourhoods in Barcelona: La Verneda and Sant Martí de Provençals, collectively referred to as La Verneda. Based primarily on qualitative methods, it draws on in-depth interviews with long-term residents. This study examines how La Verneda–Sant Martí Adult School, as a grassroots actor, has contributed to bottom-up urban regeneration by linking environmental demands with broader struggles for social dignity, health, and community cohesion. The aim is to understand how collective agency at the neighbourhood level can shape more inclusive and sustainable urban futures. Accordingly, this article asks: How did the residents of La Verneda reclaim their environment and identity through ecological transformation? What mechanisms enabled them to influence urban planning from below, and what lessons does this offer for sustainable regeneration elsewhere? By exploring these research questions, this study situates itself within international debates on community participation, green gentrification, and bottom-up environmental justice.

2. The Case Study: La Verneda Neighbourhood (Barcelona, Spain)

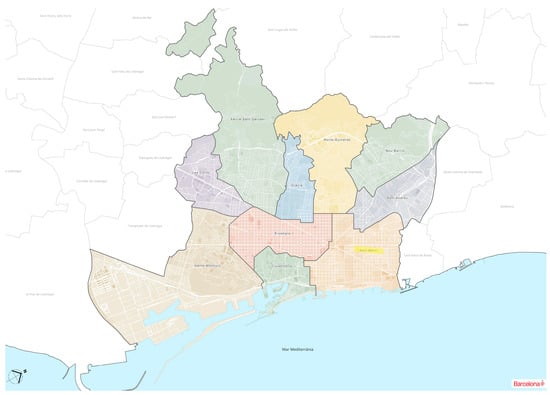

La Verneda refers to the area that today encompasses two neighbourhoods, La Verneda i La Pau and Sant Martí de Provençals, historically known as La Verneda, located within the Sant Martí district of the city of Barcelona (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

City map of Barcelona. Sant Martí District highlighted in yellow, including the area historically known as La Verneda. Source: Ajuntament de Barcelona.

La Verneda represents an urban space whose development is closely tied to the broader urban, social, and cultural transformation experienced by the city over the past century [34]. Prior to the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), the area was predominantly characterized by natural woodland [35], verneda being a Catalan term referring to groves of alder trees (vern), which thrived in the moist, fertile soils of the Barcelona plain. However, in the postwar period, and particularly during the urban boom of the 1960s and 1970s, La Verneda became the target of intense and largely unregulated real estate speculation, resulting in a profound transformation of its territorial configuration [36].

During this period, the area was transformed into a mosaic of concrete blocks, lacking green infrastructure and basic public amenities. “Hard squares”, public urban spaces characterized by the dominance of concrete, asphalt, or stone, with minimal or no presence of vegetation, natural soil, or shaded areas, emerged predominantly in the context of rapid urbanisation in Spain during the mid-20th century, particularly under the Franco dictatorship and the developmentalist policies of the 1960s and 1970s [37]. Much of the La Verneda neighbourhood was developed without proper urban planning, coinciding with the massive influx of migrants from rural regions of Spain. Many of these migrants settled in precarious conditions, often in self-built shanties [38]. As a result, La Verneda was commonly described as a marginal area, characterized by inexpensive housing and low social standing. This perception reinforced stigmas that negatively impacted both property values and the symbolic status of its residents.

Amid these transformations, residents mobilised through grassroots, non-partisan neighbourhood movements inspired by community-based traditions. Initial initiatives, framed as a “neighbourhood dream,” were soon redefined as “popular plans”, emphasising bottom-up community-led transformation. Over time, formal neighbourhood associations took the lead, sometimes aligning with municipal left-wing parties. In most neighbourhoods in Spanish cities this tendency promoted urban interventions such as hard squares and limited ecological priorities [39]. This shift reduced direct resident influence and compromised early ecological goals.

A turning point occurred with renewed community initiatives oriented towards the popular plans conceived at the “neighbourhood dream”. In La Verneda, this orientation was more powerful with the creation of VERN and the Escola de Persones Adultes La Verneda–Sant Martí [40], which were independent of any single association, and collaborated with all of them. These efforts re-centred decision-making in the hands of residents, defending green spaces, resisting hard squares, and reaffirming the neighbourhood’s identity. Over time, the area gradually transforming [34] from a stigmatized periphery, into a vibrant neighbourhood with green infrastructure, educational, social, and cultural facilities, and a strong sense of identity rooted in sustained grassroots organization.

3. Materials and Methods

This study analyses the case of La Verneda as a bottom-up model of green urban regeneration, using the Communicative Methodology. Recognized by the European Commission for its scientific, political, and social impact [41,42], this methodology has been successfully applied in major EU projects, particularly in contexts of social inequality and exclusion. The selection of the Communicative Methodology responds to the need for a participatory and reflexive approach that captures the dialogic character of community transformation. This methodology was chosen because it allows for the incorporation of reflexivity when participants contribute their interpretations, but it goes further: decision-making to avoid bias does not rest exclusively with the research team; rather, the interpretations considered valid are those reached through consensus between the team and the participants. This process takes place not only during the development of the interviews with a dialogic approach, but also in the return of the results to the participants themselves. This enhances reliability and minimizes researcher bias.

The Communicative Methodology is grounded in the principle of egalitarian dialogue between researchers and participants. Rather than positioning researchers as sole interpreters of reality, this approach fosters a co-creation process in which scientific knowledge and lived experience are brought into dialogue. Researchers share existing evidence from previous studies, such as findings on environmental justice, urban inequality, and dialogic education, while participants contribute their own experiences, memories, and reflections. Interpretations are not imposed but agreed upon through dialogue. In this study, the dialogic process was enriched by the long-standing relationships of trust between some of the researchers and the participants. Several authors of this study have been actively involved in the La Verneda–Sant Martí Adult Education School and the neighbourhood’s community life for decades. This shared history created a context of mutual recognition and respect, allowing participants to speak freely and confidently about their experiences and perspectives.

3.1. Data Collection

Data were collected through five open and communicative interviews conducted between July and September 2025, in locations chosen by the participants to foster comfort and trust. Rather than structured interviews with a fixed questionnaire, these were open dialogues focused on the topic under investigation: the transformation of La Verneda and the role of community mobilization in reclaiming green space and neighbourhood identity.

The inclusion criteria focused on individuals who had lived in La Verneda since the 1960s and 1970s, thereby experiencing the neighbourhood’s urban and ecological transformations firsthand. Among those who met this criterion, priority was given to individuals who had actively participated in community mobilizations, particularly those related to the defence of green spaces, public services, and neighbourhood identity.

This study included five participants (four women and one man), aged between 70 and 85 years. Their profiles are summarized in Table 1. Four of the five participants remain actively involved in the La Verneda–Sant Martí Adult Education School and in broader community initiatives. Their continued engagement reflects the neighbourhood’s strong culture of participation and facilitated a dialogic and trust-based research process. The fifth participant also lived in La Verneda during the period of transformation and, although she/he later moved away, her/his mother remained in the neighbourhood until the late 2010s. She/He was selected because of her/his deep knowledge of the neighbourhood’s evolution and her/his accessibility.

Table 1.

Participant profiles.

In line with Communicative Methodology, researchers shared relevant findings from previous studies on urban regeneration, environmental justice, and dialogic education. Participants responded by narrating their own experiences, and together, both parties discussed and agreed on the interpretations that best captured the meaning of those experiences. The strong relationships of trust between some researchers and participants, built over decades of shared involvement in adult school and community initiatives, were essential to fostering open, reflective, and egalitarian dialogue. All interviews were audio-recorded with consent and supplemented by field notes. Transcriptions were reviewed with participants, who were invited to clarify or expand on their statements to ensure accurate representation of their perspectives.

Although the final sample consisted of five participants, this number was not arbitrarily determined but corresponded to the point of theoretical saturation. Each participant represented a different form of involvement in community life: from early neighbourhood activism to intergenerational educational leadership, ensuring diversity of perspective rather than statistical representation. Saturation was confirmed when subsequent interviews produced no new categories or contradictions in the interpretation of the data. Thus, the narratives gathered provided rich insights into the key dimensions of La Verneda’s transformation, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of the processes and values that shaped the neighbourhood.

3.2. Data Analysis

The data analysis was conducted in accordance with the principles of Communicative Methodology, focusing on identifying both exclusionary dimensions (those that reproduce inequalities) and transformative dimensions (those that contribute to overcoming them). The coding process combined both inductive and deductive procedures. Initial categories were derived from the scientific literature on urban inequality, environmental justice, dialogic education, and community-led regeneration, while new subcategories emerged from the narratives shared by participants, which provided situated accounts of the neighbourhood’s transformation, and allowed for dialogic validation. In this sense, the interviews were analysed dialogically: interpretations were discussed with participants to ensure that the resulting themes accurately reflected their perspectives. This procedure ensured reflexivity and coherence between empirical data and theoretical interpretation. Table 2 summarizes the main themes, categories, and subcategories identified:

Table 2.

Themes, categories, and subcategories identified in the analysis.

This thematic structure allowed for a comprehensive understanding of La Verneda’s transformation, highlighting how ecological and social regeneration were deeply intertwined and driven by community agency.

3.3. Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with international guidelines and requirements, including the principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights (CFREU). This study was designed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval by the Ethics Committee of the Community of Researchers on Excellence for All (CREA), with approval number 20250927. Pseudonyms were assigned to ensure anonymity and protect participants’ identities

4. Results

4.1. La Verneda as a Bottom-Up Model of Green Urban Regeneration

The ecological transformation of La Verneda cannot be understood without recognizing the grassroots movement that emerged in the late 1970s and early 1980s. At that time, urban planning in Spain was dominated by technocratic reasoning focused on cost efficiency. Green spaces were considered expensive and difficult to maintain, leading to the widespread construction of plazas duras [hard squares], concrete public spaces devoid of trees or gardens. Environmental concerns, such as air quality or access to nature, were largely ignored in favour of rapid, low-cost urban development. This trend was particularly evident in the peripheral neighbourhoods of large industrial cities, such as Barcelona, which experienced a massive influx of working-class migrants from rural areas of Spain. To accommodate this demographic shift, new high-density neighbourhoods were hastily built on the outskirts of the cities and in nearby municipalities. These areas were often characterized by tall apartment blocks, concrete-dominated landscapes, and a lack of basic infrastructure and green spaces, products of top-down planning that prioritized speed and cost over liveability.

In contrast, La Verneda’s residents organized to reclaim their neighbourhood. Rejecting the dominant postmodernist urban design promoted even by newly democratic city councils, they resisted the minimal-vegetation model and envisioned a return to nature. Their vision was rooted in the historical identity of the area: before the Spanish Civil War, La Verneda had been a forest of verns (alders), and the community sought to restore that legacy through collective action.

La Verneda—Sant Martí Adult Education School became a central space for this movement. Founded in the late 1970s, the school was created to respond to the educational exclusion experienced by many residents, especially women, who had migrated from rural areas to work in Barcelona’s industrial sector. From its inception, the school adopted a dialogic approach to learning, where reading and writing were not treated as mechanical skills but as tools for collective reflection and transformation. Learning took place through egalitarian dialogue, where participants shared their experiences, questioned existing inequalities, and reached agreements on actions to improve their social, cultural, educational, and urban environments.

As Aurora recalled: In class, we used to talk about how important it was to have a green area… so it wouldn’t be all asphalt. Aurora had worked as a manual labourer in the textile industry and learned to read and write through the school’s literacy programs. Almudena added: The school is a space where people come together to fight for those kinds of public spaces. She completed her primary education at the adult school and, like Aurora, became actively involved in neighbourhood mobilizations. This bottom-up approach linked nature with culture, challenging the segmentation of the environmentalist movement that often excluded working-class voices. As Almudena put it: We didn’t have formal education, but we knew, and we wanted, that this neighbourhood wouldn’t be what others wanted it to be, but what we, the people, wanted.

Jimena, who moved to La Verneda 61 years ago from a small town in Andalusia, emphasized the long-standing culture of activism: It’s always been a very activist neighbourhood, and we’ve managed to achieve quite a few things. She added: It has nothing to do with what we have now, honestly. But all of that was achieved thanks to the people in the neighbourhood fighting hard for it. The neighbourhood associations, the adult school, so many people, all of us together. Her testimony reinforces the collective nature of the transformation, where diverse actors came together to reclaim not only green areas but also a liveable neighbourhood. In a district that had already been densely built, the demands focused on halting further construction and recovering open, natural spaces that could bring health, connection, and dignity to everyday life.

One of the most symbolic victories of La Verneda’s grassroots movement was the creation of an elderly residence alongside a square with a children’s playground, filled with trees. Initially, the entire block had been designated for high-density residential development, with plans to construct additional apartment buildings. However, neighbours mobilized to demand a more socially conscious use of the space. Their advocacy led not only to the creation of the residence but also to the preservation of the adjacent area as a green plaza with trees and a children’s playground for intergenerational interaction. As Aurora recalled: That had to be fought for, too. We were there to make sure it wouldn’t all turn into a big block of buildings like they were planning. The residence takes up part of the block, and the other part is the square with a play area for the kids.

The residence was built with large windows that allow natural light to enter and offer views of a plaza filled with trees and a playground where children play. This layout was intentionally conceived so that older residents could sit by the windows and enjoy the vitality of the park, watching children play among the trees and feeling part of the life of the neighbourhood. Aurora emphasized:

So, in the end, they managed to build the elderly residence there, and right next to it they made a square for the kids. From the windows of the residence, you can see the children playing, the grass, and the trees. All of that was achieved thanks to the neighbourhood’s constant demands.

Jimena added a crucial detail about the urban planning: They wanted to build more apartment blocks. But we protested again, and that’s how we got the residence. She also highlighted the importance of architectural choices: Making it with big windows was important too, because people don’t feel so isolated, they can see the kids playing. These reflections demonstrate how the community’s vision extended beyond infrastructure to encompass emotional and social well-being, underscoring the importance of urban planning that is responsive to human needs.

The accounts presented here reveal more than a historical sequence of local struggles; they illustrate a collective epistemology of urban transformation. In this vein, residents did not merely ‘green’ their surroundings but redefined the meaning of public space through dialogic engagement. This analytical layer positions La Verneda’s regeneration not as a linear outcome of activism but as a dialogic co-production of knowledge between citizens and the environment.

4.2. Local Agencies in Shaping Sustainable Cities

The success of La Verneda’s transformation was made possible by strong grassroot citizen movements, including local organizations rooted in the neighbourhood’s social fabric. A key actor was the VERN, the coordinating body of local associations, created in 1978 and officially established in 1987, though its foundations were laid years earlier through collaborative efforts among neighbourhood associations. VERN emerged to strengthen collective action and civic participation, and today it brings together more than 70 entities working to improve the social, educational, cultural, and urban conditions of the area. Among its founding members is the La Verneda—Sant Martí Adult Education School, which has played a particularly transformative role. From its inception, the school adopted a dialogic approach to learning, where reading, writing, and other skills were taught through egalitarian dialogue. This method fostered collective reflection and action, allowing participants to identify and challenge the social, cultural, educational, and urban inequalities surrounding them. As Almudena emphasized: That’s where we learned to stand up for ourselves… your voice has to be heard. She also linked urban planning to health and well-being: Everything we fought for was about making it easier to live together… and it turned out to be really good for people’s health too.

Aurora highlighted how important the school was in helping the community mobilize: They played a big role in getting us out on the streets to demand green spaces and facilities for the neighbourhood, because back then, this was all brand new. There weren’t even proper roads; nothing was in place. Teresa added, highlighting the early struggles for basic services: We neighbours fought first for doctors. In the end, we got the local health centre. Her words reflect how the demand for green spaces was not isolated but deeply connected to broader struggles for public health infrastructure. Residents understood that access to nature and access to healthcare were both essential for a dignified life, and they mobilized collectively to achieve both. Luis offered a complementary perspective, emphasizing the opportunity that came with building a new neighbourhood, especially when compared to older working-class areas: When a new neighbourhood was built, it gave us the chance to have at least some kind of garden: In the older ones, they didn’t even think about trees or green spaces. He pointed out that other newly built areas in the city lacked green spaces, and that La Verneda’s residents were determined to avoid making the same mistake. Their vision was clear: if a new urban space was being created, it should include gardens and trees, not just cement.

These testimonies reflect how local agency in La Verneda was not limited to environmental demands but extended to a holistic vision of urban justice. Residents fought simultaneously for healthcare, green infrastructure, and liveable public spaces, reshaping the neighbourhood through collective action grounded in everyday needs and aspirations.

Importantly, this local movement also addressed a type of conflict that, in other contexts, has often emerged between the environmental movement and working-class communities. In many industrial or working-class neighbourhoods, ecological activism was sometimes viewed as disconnected from, or even in opposition to, local needs, especially when it was perceived as a threat to jobs. In La Verneda, however, the ecological transformation was driven by the people themselves, integrating environmental justice with social dignity. This was made possible in part by the school’s commitment to lifelong learning, which enables neighbours themselves to become the protagonists of their own transformation and that of their neighbourhood. Since its early days, the school has offered pathways for residents to obtain academic qualifications, learn languages, gain digital literacy, and access job training. Operating from Monday to Sunday, from 9 a.m. to 10 p.m., it engages over 100 volunteers alongside contracted educators from the two participant associations that manage the school. Through this sustained educational, cultural, and social work, anchored in dialogic practices and community collaboration, the neighbourhood was able to build the collective capacity needed to shape a more sustainable and inclusive urban future.

Analytically, these testimonies show that dialogic education functions as a civic infrastructure enabling inclusive decision-making. The creation of the Adult School led to learning and negotiating to redefine spatial priorities. Participants’ narratives of the school as a place “where we learned to speak up” underscore how empowerment is not an outcome but a continuous pedagogical process. In this sense, La Verneda’s transformation offers empirical grounding for Freirean theories of conscientization applied to urban regeneration, bridging collective human action with structural change.

4.3. Measurable Improvements in Environmental Quality

One of the most notable achievements of La Verneda’s grassroots movement was the transformation of Carrer de Guipúscoa [Guipúscoa Street], a wide avenue that cuts across the neighbourhood and was originally planned to become part of a traffic ring. That wide unpaved street was meant to continue Aragó Street, one of the city’s major arteries. Residents mobilized to prevent this, demanding instead a pedestrian-friendly space filled with trees and public life. As Aurora recalled: We managed to stop it from turning into a big traffic ring road. Almudena added: It was going to be a wide road, but the neighbourhood fought for it to become a rambla, a tree-lined promenade where people could walk and gather. Teresa described what it used to be like: It was like a highway, with loads of cars. Today, it is a broad, tree-lined boulevard with safe pedestrian crossings, a wide variety of shops and cafés, and access to public transport, including three metro stations, La Pau, Sant Martí, and Bac de Roda, which were also the result of community advocacy. Due to its central pedestrian layout, residents now refer to it informally as Rambla Guipúscoa, adopting the term rambla commonly used in Barcelona to describe wide, tree-lined pedestrian boulevards. Historically, many ramblas were former natural watercourses (rieras) that were later urbanized and transformed into public promenades. Although Carrer de Guipúscoa was never a riera and its official name remains unchanged, the community’s use of the term reflects the symbolic reimagining of the space, from a planned traffic artery into a green, social corridor shaped by community action.

Aurora emphasized the transformation:

Rambla Guipúscoa used to be a really bad street, really bad, there were so many cars going through. They even wanted to turn it into a ring road so even more cars would pass. But thanks to what the people achieved, it became a promenade for the neighbourhood, where people can walk and sit down, there are lots of benches and many different kinds of trees.

Jimena added:

Another great thing we got for the neighbourhood was the Line 2 metro. There were a lot of protests to make it happen, and in the end, we got it. Just look at how much life the metro brings to the neighbourhood.

She highlighted the social impact of these changes:

Now I think it’s like the centre of the neighbourhood, where lots of older people go for a walk, really because of this, because even if you’ve got mobility problems, you can still go out, with a wheelchair, with a walker. And people really socialize a lot on the Rambla, because when you go out walking, you run into lots of folks and you chat with them.

Another emblematic case is Rambla Prim, which was previously a highly degraded area. Teresa recalled: Rambla Prim was a sewer. It used to be known as the Riera d’Horta [a natural channel that carries rainwater to the sea], where all the wastewater ran openly down to the sea. You could see the electric and phone cables hanging, there were loads of mosquitoes, and the smell was awful… Jimena added: There were so many rats; we used to call it the valley of the rats. The riera functioned as an open sewer and informal dumping ground, creating insalubrious conditions right next to residential buildings. Owing to sustained community pressure, Rambla Prim was transformed into a green corridor with gardens, playgrounds, and tree-lined paths that now stretch almost to the sea. As part of this transformation, the sewage and rainwater were also redirected underground into the city’s municipal drainage system, which now channels them to one of Barcelona’s wastewater treatment plants. Aurora described the transformation: They turned it into a rambla with gardens, grass, and lots of trees, where people go for walks, it almost reaches the sea. Jimena added: Rambla Prim, honestly, they made it really beautiful, and now you can walk almost all the way down to the sea.

These transformations have had a direct impact on environmental quality and air health in the neighbourhood. According to municipal data, NO2 levels in Carrer de Guipúscoa and Rambla Prim remain consistently between 20 and 30 µg/m3, well below the EU annual limit of 40 µg/m3, and significantly lower than in more congested areas of the city, such as Carrer Aragó or Via Laietana [43]. This improvement is largely attributed to the dense and continuous tree cover, which acts as a natural barrier against pollution and enhances urban ventilation. These green corridors have become not only healthier but also more inclusive and accessible.

Together, these examples illustrate how bottom-up urban planning can lead to measurable improvements in environmental quality, turning formerly degraded spaces into vibrant, green, and healthy public areas. The presence of vegetation, reduced traffic, and inclusive urban design have contributed not only to cleaner air but also to greater social cohesion and well-being.

Beyond the descriptive dimension, these findings underscore the dialogic articulation between lived experience and measurable environmental outcomes. Residents’ testimonies of “breathing better” correspond to a material reconfiguration of the neighbourhood’s dynamics, where collective agency translates into ecological benefits. In this context, the residents’ sense of environmental restoration is not anecdotal but part of a citizen-scientific validation process that enriches conventional indicators.

4.4. Access to Green Spaces

The community’s advocacy led to the preservation and creation of green spaces throughout the neighbourhood. A key example is the protection of the masies [masia is the traditional Catalan farmhouse], which were scheduled for demolition in the early 1980s. Aurora explained: The neighbourhood started fighting so they wouldn’t tear them down… so they’d restore them and turn the area into a park. When demolition began in 1982, La Verneda—Sant Martí Adult Education School suspended all classes, and everyone left the school and peacefully stood in front of the excavators to stop them. Aurora recalled: We were protesting from the school. When the excavators came in, we stopped the classes and went there. We stood in front of the machines so they wouldn’t knock them down and build more apartment blocks. Owing to this mobilization, Ca l’Arnó [Ca is a shortened form of casa, meaning “house of”], a masia dating back to 1689, was saved and later restored through an international volunteer camp in 1988. In 1992, it was converted into a children’s ludoteca (play centre), becoming a symbol of the neighbourhood’s commitment to education, heritage, and ecological regeneration.

Today, the area is home to the Parque de Sant Martí [Sant Martí Park], a 6.8-hectare green space structured in two zones, with hundreds of trees, restored masies serving as social and educational facilities, and community vegetable plots managed by retired residents. Aurora described the transformation: Now there’s a really nice park, and they planted lots of trees. There are also lots of activities in the park, for kids and for everyone. There’s a lot of green space. One of the masies has a play centre for children. These vegetable gardens not only promote ecological sustainability and food autonomy but also serve as spaces of social interaction and community care. The park also preserves the historical core of Sant Martí de Provençals, formerly an independent municipality that was incorporated into the city of Barcelona in the late 19th century. It includes the medieval church and other masies, such as Can Planas and Can Cadena, now repurposed as public facilities.

Aurora also criticized the urban planning trends of the time:

People were complaining because there was a time in Barcelona when they made all the squares out of concrete, no flowers, no trees. They just wanted to build blocks of flats really close together, and that couldn’t be. We had to preserve the green that was still there and bring back what had been lost.

Luis added historical context: Before they built it, La Verneda was all vegetable gardens and woods.

Another emblematic case is Plaça de La Verneda [La Verneda Square], located at the end of Carrer de Puigcerdà [Puigcerdà Street], which was originally planned for construction. Owing to community resistance, it was preserved as an open green space. Aurora remembered:

I almost forgot about Plaça de La Verneda. I used to go there with my nephews when they were little. There was nothing there, no park for the kids. We managed to get them to build a square with lots of green space, trees, and a playground.

Teresa added: I protested many times for Plaça de La Verneda because my daughters used to play there. It was great; it was the path between where we lived and the school.

When plans to build on the square were announced, mothers in the neighbourhood mobilized:

When they said they were going to build on the square, we mothers didn’t like it. So we started the revolution! In the end, they didn’t build on it. They fixed it up with trees, and now we have a park.

The final design of the public square respected the existing mature trees and created distinct zones for sun and shade. It included planters, wooden benches, and a children’s play area. Importantly, the project was shaped by participatory input from residents.

Jimena summarized the outcome of decades of collective effort: We’ve managed to build a good neighbourhood. First, the streets are fixed up, and then there are lots of trees. Not every neighbourhood has as many trees as we do. She also expressed a wish for continued care: What I’d ask, if possible, is for the government to keep the streets a bit cleaner.

These interventions were not isolated; they were part of a broader movement that linked environmental regeneration with educational and cultural transformation. The neighbourhood’s green spaces are not just aesthetic improvements. They are the result of collective action, rooted in a vision of urban justice, ecological sustainability, and community well-being.

These accounts unveil a process of symbolic repair, exemplified through the residents’ insistence on preserving the name “La Verneda”, as a means to reclaim ownership and assert belonging of their neighbourhood. Thus, naming becomes a vehicle through which the community affirm its visibility and resist erasure. The recovery of identity complements physical regeneration, demonstrating how social memory works as an ecological resource.

4.5. Community Cohesion

The regeneration of La Verneda was not only physical but also deeply social. La Verneda—Sant Martí Adult Education School became a central space for building community cohesion and community engagement. Aurora recalled: When the school started in ’78, the neighbourhood lacked everything. From its inception, the school adopted a dialogic approach to learning, where education was not a mechanical process but a collective, egalitarian dialogue. Through this model, residents reflected on their realities, shared experiences, and organized to transform their social, cultural, educational, and urban environment.

This spirit of dialogue and unity also gave rise to the VERN, rooted in earlier collaborations among citizens and neighbourhood, educational, and cultural associations. For the first time, people with very different, even opposing, political ideologies came together to work toward common goals. As Almudena emphasized: Politically, each of us might have had our own ideas… but when it came to certain things, it was about bringing everyone together for a common goal. This collective spirit was essential in achieving the neighbourhood’s transformation.

The naming of the school itself reflects this inclusive vision. In response to a Council proposal to rename the neighbourhood “Sant Martí”, a name perceived by some as more dignified and institutional, residents resisted the erasure of La Verneda, which had been stigmatized due to its working-class origins and past urban neglect. The school proposed a hybrid identity: La Verneda—Sant Martí, preserving both the cultural legacy of Sant Martí and the ecological memory of La Verneda, whose name comes from the vern (alder tree) that once populated the area.

This openness and inclusive identity have continued over time. The school and the neighbourhood have welcomed new migrant populations from Asia, Africa, and Latin America, integrating them into the educational, cultural, and civic life of the community. A powerful example of this collective effort is the Biblioteca Gabriel García Márquez [Gabriel García Márquez Library], inaugurated in 2022. The public library was the result of years of neighbourhood advocacy, driven by the demand for a new space after the previous library became too small. The name honors the Colombian Nobel Prize-winning author and reflects the growing presence of Latin American residents in the neighbourhood. Today, it is the third-largest library in Barcelona and was named the best new public library in the world by IFLA (International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions) in 2023. Jimena celebrated this achievement: If there was anything missing, now we have it: the big library!

La Verneda is a neighbourhood with a strong sense of community and a vibrant public life. Its ramblas and plazas [tree-lined promenades and public squares] are filled with people of all ages, walking, playing, and socializing. Jimena described this dynamic atmosphere with pride: It’s a neighbourhood I’m proud of. She also highlighted the importance of everyday encounters: No one feels alone when they go out for a walk along Rambla Guipúscoa. These public spaces foster spontaneous interaction and mutual support, especially among older residents. The area has also experienced steady growth in local commerce, featuring a mix of traditional markets, small businesses, and large supermarkets, all of which contribute to a dynamic urban life that maintains its neighbourhood spirit while preserving its identity. Together, these elements, dialogic learning, inclusive identity, cultural infrastructure, and active public life, illustrate how community cohesion has been a driving force behind La Verneda’s transformation into a socially and ecologically sustainable urban space.

Community cohesion in La Verneda fosters everyday cooperation and promotes a diversity that thrives on difference. Testimonies of shared maintenance of green areas and collective festivities reflect a performative continuity of belonging that extends beyond generational lines. While the elder activists embody the original civic ethos, younger residents inherit an infrastructure of solidarity that can be renewed through new participatory formats. This ongoing process confirms that social capital in working-class contexts is not static heritage but dynamic capacity, constantly enforced through dialogue and collaborative management of space.

5. Discussion

The ecological transformation of La Verneda exemplifies how bottom-up urban regeneration can effectively counteract the environmental injustices historically associated with peripheral working-class neighbourhoods. Urban segregation and zoning policies have often relegated vulnerable populations to areas with poor environmental quality [2,5]. In contrast, La Verneda’s residents mobilized to reclaim green space, challenging the dominant planning paradigms of the late 20th century. This case aligns with the conceptualization of the neighbourhood as a physical, social, and political unit [6]. The testimonies of long-term residents reveal how collective identity and community mobilization were central to resisting the imposition of “hard squares” and promoting a liveable environment. The transformation of this urban space demonstrates how community-led planning can lead to measurable improvements in environmental quality, with NO2 levels consistently below EU thresholds [43].

The role of the La Verneda–Sant Martí Adult Education School was pivotal in this process. This school was a key space for advancing dialogic learning rooted in the lived experiences of residents, many of whom had migrated from rural areas and had not previously had access to formal schooling [44,45]. Through literacy and basic education, the school fostered a culture of egalitarian dialogue where neighbours reflected together on how to improve their living conditions. These conversations were not limited to educational needs but extended to broader demands for a dignified neighbourhood, including access to health services, social infrastructure, and green public spaces. The struggle against “hard squares” and uncontrolled construction was always intertwined with the defence of green parks, plazas, ramblas, and natural heritage. In this context, the adult school was not only a path to individual development, but a collective process of neighbourhood transformation grounded in everyday realities and aspirations.

Moreover, the benefits of urban green spaces observed in La Verneda, such as improved air quality, reduced urban heat, and enhanced social cohesion, are consistent with findings from previous studies [15,20,21]. These studies highlight the role of vegetation in promoting physical and mental health, mitigating pollution, and fostering climate resilience. However, as previous studies have warned [23,26], urban greening projects can also perpetuate inequalities when implemented through top-down approaches. In contrast, La Verneda’s transformation was driven by grass-roots mobilization, ensuring that environmental improvements were aligned with community needs. This bottom-up model challenges the exclusionary dynamics observed in other cities, such as Shanghai, Tartu, and Melbourne [27,28,30]. As well, by integrating residents’ voices into the decision-making process, La Verneda demonstrates that dialogic, community-based planning can function as an alternative to both technocratic and market-driven urban governance. This approach advances theoretical understandings of participatory governance by evidencing how egalitarian dialogue can operationalize environmental justice in contexts of historical deprivation.

Inclusive design principles were evident in the interventions, in line with previous studies emphasizing intergenerational spaces and accessibility as key components of equitable urban regeneration [22,32]. These interventions not only improved environmental conditions but also strengthened community cohesion, as evidenced by the testimonies of residents who linked green spaces to health, dignity, and social connection. Interventions prioritized intergenerational interaction and emotional well-being. This achievement reflects the community’s vision of urban planning that prioritizes human needs, ecological regeneration, and social inclusion. It was also deeply tied to a strong sense of identity and a sense of belonging. Residents consistently expressed pride in the kind of neighbourhood they had built, one with green spaces, public services, and vibrant community life. The defence of the neighbourhood’s name illustrates the role of symbolic recognition in regeneration. This naming choice symbolized the neighbourhood’s inclusive and dignified identity, rooted in both cultural heritage and decades of collective struggle.

The findings from the current study align with recent research in Urban Science, which shows that increased community engagement in green space management is correlated with improved access and reduced socio-environmental inequality [46]. This supports the idea that participatory governance is not only desirable but necessary to ensure equitable urban sustainability, especially in contexts of historical exclusion. The case of La Verneda contributes to the broader debate on the role of local agency in shaping sustainable cities. As highlighted by previous studies [33].

Recent findings from ISGlobal, Barcelona Institute for Global Health [47], reinforce the relevance of La Verneda’s grassroots transformation by quantifying the health benefits of urban greening. Their study estimates that full implementation of the Green Corridors Plan, a city-wide initiative proposed by the Barcelona City Council to convert one in every three streets into vegetated corridors, could prevent up to 178 premature deaths annually due to increased greenery, and 5 additional deaths during heatwaves through temperature reduction. In the Sant Martí district, where La Verneda is located, the plan projects a 15% increase in green surface area and the addition of 0.09 trees per linear meter, making it one of the areas with the highest potential for thermal improvement. However, these interventions echo demands that La Verneda’s residents had already articulated decades earlier. Long before scientific consensus emerged on the role of vegetation in mitigating urban heat and improving public health, the community had mobilized against “hard squares” and advocated for tree-lined streets, shaded plazas, and ecological restoration. In this sense, La Verneda’s movement not only anticipated contemporary urban sustainability frameworks, but it also embodied them, integrating environmental justice, health, and neighbourhood identity into a coherent and community-driven vision of regeneration.

The dialogic model that allowed for La Verneda’s transformation reveals transferable principles that can inspire other communities facing ecological and social marginalisation. Its strength lies not in replicating identical organisational forms, but in cultivating dialogic spaces where neighbours collectively produce meaning, vision, and action. The potential for upscaling resides in the multiplication of such learning spaces, supported by alliances between civil society, municipalities, and universities. Far from being constrained by political or institutional limitations, these partnerships illustrate how agency can be redistributed through dialogue itself. La Verneda thus provides a hopeful case of urban transformation, one that frames environmental justice as a cumulative, dialogic, and replicable practice rather than a singular achievement.

The findings also underscore the limitations of the current study. As with other qualitative case studies, the insights presented here are context-specific and not intended for statistical generalization. While the narratives provide rich evidence of lived experience, they are also subject to the interpretive nature of oral histories. As well, in addition to the qualitative findings, future research could benefit from integrating more systematic quantitative data on air quality, tree coverage, or surface temperature derived from municipal open datasets. In this study, the analysis of NO2 levels (20–30 µg/m3) is used illustratively to signal environmental improvement, but further environmental indicators, such as normalized vegetation indices or longitudinal comparisons, could complement community accounts and provide a more robust measure of ecological impact.

Finally, this study primarily reflects the experiences of older generations who led the neighbourhood’s transformation. Future inquiry could explore how newer generations perceive and benefit from these earlier efforts, particularly how they reinterpret green spaces as part of their everyday urban identity. Such complementary studies would allow for a fuller understanding of how community-driven ecological regeneration sustains itself across time and demographic change.

6. Conclusions

The case of La Verneda demonstrates that ecological urban transformation is not only possible in working-class neighbourhoods but can be more inclusive, sustainable, and socially rooted when driven by the residents themselves. Far from being passive recipients of top-down planning, the people of La Verneda actively resisted the dominant urban models of the time, characterized by “hard squares” and unchecked construction, and reclaimed their right to a dignified neighbourhood with green spaces, public services, and cultural infrastructure.

The transformation was not limited to physical improvements. It was deeply social, educational, and cultural. La Verneda–Sant Martí Adult Education School played a central role in this process, fostering dialogic learning and community engagement among residents who had migrated from rural areas and had not previously accessed formal education. Through egalitarian dialogue, neighbours organized to demand not only literacy and healthcare, but also parks, plazas, and tree-lined streets that reflected their vision of a liveable and connected community.

The creation of intergenerational spaces, such as the elderly residence with large windows facing a green plaza and children’s playground, exemplifies how urban planning can respond to human needs when shaped by local agency. The defence of the neighbourhood’s name, La Verneda, against proposals to rename it “Sant Martí”, further illustrates the importance of symbolic recognition and collective memory in processes of urban regeneration.

This bottom-up model offers valuable lessons for other urban peripheries undergoing ecological transition. It shows that environmental justice must be intertwined with social dignity, and that sustainable cities are built not only with trees and infrastructure, but with the voices, histories, and aspirations of their residents.

Author Contributions

E.T.-G.: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing—Original draft, Writing—review and editing; C.J.: Resources; A.A. (Aitor Alzaga): Writing—Original draft; E.O.: Conceptualization, Data curation; L.R.-E.: Formal analysis, Writing—Original draft, Writing—review and editing; M.S.-G.: Conceptualization, Supervision; L.P.: Conceptualization, Supervision; A.A. (Adriana Aubert): Conceptualization, Writing—review and editing; R.V.-C.: Conceptualization, Investigation; R.F.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision; A.L.d.A.: Formal analysis; K.M.: Writing—Original draft; A.C.-L.: Investigation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Community of Researchers on Excellence for All (CREA) (20250927) on 27 September, 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors due to confidentiality reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- UN-Habitat. Rescuing SDG 11 for a Resilient Urban Planet; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Grove, M.; Ogden, L.; Pickett, S.; Boone, C.; Buckley, G.; Locke, D.H.; Lord, C.; Hall, B. The Legacy Effect: Understanding How Segregation and Environmental Injustice Unfold over Time in Baltimore. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2018, 108, 524–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haandrikman, K.; Costa, R.; Malmberg, B.; Rogne, A.F.; Sleutjes, B. Socio-Economic Segregation in European Cities. A Comparative Study of Brussels, Copenhagen, Amsterdam, Oslo and Stockholm. Urban Geogr. 2023, 44, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilisei, R.-D.; Salom-Carrasco, J. Urban Projects and Residential Segregation: A Case Study of the Cabanyal Neighborhood in Valencia (Spain). Urban Sci. 2018, 2, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazorra Rodríguez, Á. Social Inequality and Residential Segregation Trends in Spanish Global Cities. A Comparative Analysis of Madrid, Barcelona, and Valencia (2001–2021). Cities 2024, 149, 104935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baffoe, G. Understanding the Neighbourhood Concept and Its Evolution: A Review. Environ. Urban. Asia 2019, 10, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren Andersen, S.; Blot, W.J.; Shu, X.-O.; Sonderman, J.S.; Steinwandel, M.; Hargreaves, M.K.; Zheng, W. Associations between Neighborhood Environment, Health Behaviors, and Mortality. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 54, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, E.Y.; Ailshire, J.A. Neighborhood Stressors and Epigenetic Age Acceleration among Older Americans. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2024, 79, gbae176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, C.E.; Mirowsky, J. Neighborhood Disadvantage, Disorder, and Health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2001, 42, 258–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez Roux, A.V. Neighborhoods and Health: What Do We Know? What Should We Do? Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 430–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Yang, R.; Lu, H.; Fernandez, J.; Wang, T. Why Do We Love the High Line? A Case Study of Understanding Long-Term User Experiences of Urban Greenways. Comput. Urban Sci. 2023, 3, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palardy, N.P.; Boley, B.B.; Johnson Gaither, C. Residents and Urban Greenways: Modeling Support for the Atlanta BeltLine. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 169, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal Yañez, D.; Pereira Barboza, E.; Cirach, M.; Daher, C.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; Mueller, N. An Urban Green Space Intervention with Benefits for Mental Health: A Health Impact Assessment of the Barcelona “Eixos Verds” Plan. Environ. Int. 2023, 174, 107880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chastenet, C.A.; Belziti, D.; Bessis, B.; Faucheux, F.; Le Sceller, T.; Monaco, F.-X.; Pech, P. The French Eco-Neighbourhood Evaluation Model: Contributions to Sustainable City Making and to the Evolution of Urban Practices. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 176, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigolon, A.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; McAnirlin, O.; Yoon, H.V. Green Space and Health Equity: A Systematic Review on the Potential of Green Space to Reduce Health Disparities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, C.; Wang, R.; Akaraci, S.; Burns, C.; Garcia, L.; Clarke, M.; Hunter, R. The Contribution of Urban Green and Blue Spaces to the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals: An Evidence Gap Map. Cities 2024, 145, 104706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira e Almeida, L.; Favaro, A.; Raimundo-Costa, W.; Anhê, A.C.B.M.; Ferreira, D.C.; Blanes-Vidal, V.; Dos Santos Senhuk, A.P.M. Influence of Urban Forest on Traffic Air Pollution and Children Respiratory Health. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafari, S.; Shabani, A.A.; Moeinaddini, M.; Danehkar, A.; Sakieh, Y. Applying Landscape Metrics and Structural Equation Modeling to Predict the Effect of Urban Green Space on Air Pollution and Respiratory Mortality in Tehran. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cinderby, S.; Archer, D.; Mehta, V.K.; Neale, C.; Opiyo, R.; Pateman, R.M.; Muhoza, C.; Adelina, C.; Tukhanen, H. Assessing Inequalities in Wellbeing at a Neighbourhood Scale in Low-Middle-Income-Country Secondary Cities and Their Implications for Long-Term Livability. Front. Sociol. 2021, 6, 729453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millward, A.A.; Torchia, M.; Laursen, A.E.; Rothman, L.D. Vegetation Placement for Summer Built Surface Temperature Moderation in an Urban Microclimate. Environ. Manag. 2014, 53, 1043–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabon, L.; Shih, W.-Y. Urban Greenspace as a Climate Change Adaptation Strategy for Subtropical Asian Cities: A Comparative Study across Cities in Three Countries. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 68, 102248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Urban Green Spaces and Health; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover, F.-A.; Meerow, S.; Grabowski, Z.J.; McPhearson, T. Environmental Justice Implications of Siting Criteria in Urban Green Infrastructure Planning. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2021, 23, 665–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo Black, K.; Richards, M. Eco-Gentrification and Who Benefits from Urban Green Amenities: NYC’s High Line. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 204, 103900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immergluck, D.; Balan, T. Sustainable for Whom? Green Urban Development, Environmental Gentrification, and the Atlanta Beltline. Urban Geogr. 2018, 39, 546–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguelovski, I.; Connolly, J.J.T.; Masip, L.; Pearsall, H. Assessing Green Gentrification in Historically Disenfranchised Neighborhoods: A Longitudinal and Spatial Analysis of Barcelona. Urban Geogr. 2018, 39, 458–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yue, W.; La Rosa, D. Which Communities Have Better Accessibility to Green Space? An Investigation into Environmental Inequality Using Big Data. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 204, 103919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa Silva, C.; Viegas, I.; Panagopoulos, Τ.; Bell, S. Environmental Justice in Accessibility to Green Infrastructure in Two European Cities. Land 2018, 7, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, Z.S.; Figari, H.; Krange, O.; Gundersen, V. Environmental Justice in a Very Green City: Spatial Inequality in Exposure to Urban Nature, Air Pollution and Heat in Oslo, Norway. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 160193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, F.; Nygaard, A.; Stone, W.M.; Levin, I. Accessing Green Space in Melbourne: Measuring Inequity and Household Mobility. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 207, 104004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazar, M.; Daloglu Cetinkaya, I.; Iban, M.C.; Bilgilioglu, S.S. The Green Divide and Heat Exposure: Urban Transformation Projects in Istanbul. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1265332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, M.; Cook, P.A.; James, P.; Wheater, C.P.; Lindley, S.J. Relationships between Health Outcomes in Older Populations and Urban Green Infrastructure Size, Quality and Proximity. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguelovski, I. Beyond a Livable and Green Neighborhood: Asserting Control, Sovereignty and Transgression in the Casc Antic of Barcelona: Asserting Control, Sovereignty and Transgression in Barcelona. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2013, 37, 1012–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borja, J.; Castells, M. Local Y Global: La Gestión De Las Ciudades En La Era De La Información; Taurus: Madrid, Spain, 2003; ISBN 9788430605446. [Google Scholar]

- Oyón, J.L. The Split of a Working-Class City: Urban Space, Immigration and Anarchism in Inter-War Barcelona, 1914–1936. Urban Hist. 2009, 36, 86–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatjer, M.; Larrea, C. (Eds.) Barraques: La Barcelona Informal Del Segle XX; Museu d’Història de Barcelona, Institut de Cultura, Ajuntament de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2010; ISBN 9788498502909. [Google Scholar]

- Capel, H. La Morfologia De Las Ciudades; Ediciones del Serbal: Barcelona, Spain, 2006; ISBN 9788476283912. [Google Scholar]

- Huertas Claveria, J.M.; Andreu, M. Barcelona En Lluita: El Moviment Urbà 1965–1996; Ketres: Barcelona, Spain, 1996; ISBN 9788485256822. [Google Scholar]

- Capel, H. El Modelo Barcelona: Un Examen Crítico; Ediciones del Serbal: Barcelona, Spain, 2005; ISBN 9788476284797. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Aroca, M. Voices inside Schools—La Verneda-Sant Martí: A School Where People Dare to Dream. Harv. Educ. Rev. 1999, 69, 320–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Activity Report “Science against Poverty” FP7 Project. 2012. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/268168/reporting (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- European Commission; Directorate-General for Research and Innovation; Flecha, R.; Radauer, A.; Besselaar, P. Monitoring the Impact of EU Framework Programmes: Expert Report; Publications Office of the European Union, Directorate-General for Research and Innovation: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; ISBN 9789279934711. [Google Scholar]

- Ajuntament de Barcelona Environmental Data Maps. Barcelona City Council. Available online: https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/mapes-dades-ambientals/qualitataire/ca/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Aubert, A.; Villarejo, B.; Cabré, J.; Santos, T. La Verneda-Sant Martí Adult School: A Reference for Neighborhood Popular Education. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2016, 118, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Eugenio, L.; Tellado, I.; Valls-Carol, R.; Gairal-Casadó, R. Dialogic Popular Education in Spain and Its Impact on Society, Educational and Social Theory, and European Research. Eur. J. Res. Educ. Learn. Adults 2023, 14, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressane, A.; Loureiro, A.I.S.; Almendra, R. Community Engagement in the Management of Urban Green Spaces: Prospects from a Case Study in an Emerging Economy. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iungman, T.; Caballé, S.V.; Segura-Barrero, R.; Cirach, M.; Mueller, N.; Daher, C.; Villalba, G.; Barboza, E.P.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M. Co-Benefits of Nature-Based Solutions: A Health Impact Assessment of the Barcelona Green Corridor (Eixos Verds) Plan. Environ. Int. 2025, 196, 109313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.