Abstract

From an ecological perspective, sustainable lighting in urban marine areas requires striking a balance between meeting human needs and protecting marine ecosystems from the harmful effects of disrupting natural light regimes. While managing artificial lighting is crucial, we argue that preventing obstructions to light penetration into the water is as important, as many marine organisms depend on the euphotic zone. This study intends to review the key factors for the implementation of wildlife-friendly lighting design in the urban marine environment, as the subject is explored in ecological studies but scarcely discussed in urban studies. An integrative literature review and cases are employed to synthesise evidence about changes to the light regime in urban marine areas from four perspectives: light reach, intensity, spectrum, and duration. The cases present measures implemented to benefit marine species affected by alterations to the light regime following urbanisation in a way that they could still thrive in a modified built environment. In discussion, it is acknowledged that achieving sustainable lighting in urban marine areas is a multifaceted challenge involving concurrent influencing factors, including a shared agency between humans and non-humans, which may require comprehensive lighting designs that are tailored to specific goals and target species.

1. Introduction

The detrimental impact of light pollution on biodiversity and ecosystems is a recurring theme in the literature [1,2,3]. Light pollution research predominantly focuses on the influence of artificial light at night (ALAN) on the natural light regime—that is “the introduction of light at night at places and times at which it has not previously occurred, and with different spectral signatures” [4] (p. 917). Yet, a smaller proportion of studies also explore urban shading as a form of disturbance [5,6].

It has already been proven that artificial lighting can harm fauna, flora, and entire ecosystems, but it is difficult to avoid using it entirely in urban areas, given its significant contributions to urban living, such as ensuring safety and enabling a variety of activities after dark [7]. While most literature on this subject centres on terrestrial areas, an increasing amount of research has examined the impact of human-induced light pollution on coastal [8] and marine areas [9,10], particularly focusing on its effects on marine biodiversity and ecosystems. This study is in line with this trend, reflecting on how to achieve sustainable lighting in urban marine areas such as urban waterfronts, estuaries, and bays, by striking the right balance between light and darkness. It acknowledges that coastal areas are of great concern, given that, worldwide, most coastal ecosystems are under increasing pressure due to the severe artificialization of coastal areas [11], and also recognises that marine urban sprawl, the rapid proliferation of hard artificial structures in the marine environment [12], is a novel and mounting phenomenon [13] requiring proper management of alterations to the natural light regime resulting from it. This study is unique in that it explores, at once, disturbance to the natural light regime in marine environments from two different perspectives: artificial light at night and shading during the day. Although Longcore & Rich [14] (p. 191) define ecological light pollution as the “artificial light that alters the natural patterns of light and dark in ecosystems” we prefer to categorise both artificial lighting and urban shading, as pollutants, here understood as “any substance, produced and released into the environment as a result of human activities, that has harmful effects on living organisms” [15]. In this case, both artificial light (Figure 1) and shade (Figure 2) produced as a result of human activities have the potential to disrupt the natural light regime. Therefore, they can be considered equally as sources of light pollution, as they are both capable of contaminating the natural environment with pollutants [16], only at different times, one at daytime and the other at nighttime.

Figure 1.

Artificial lighting illuminates a dock. (unknown location) © Phil Wain/Unsplash.

Figure 2.

Incidence of shade along a seawall at Folkestone-UK © Tyrrone Jones/Unsplash.

2. Materials and Methods

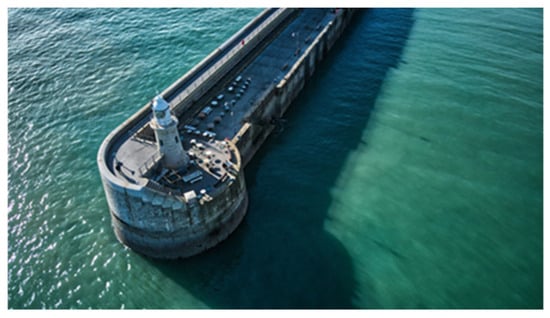

This study first employs an integrative literature review—a methodology that synthesises the knowledge and applicability of significant studies’ results to practice [17]—to examine the main factors affecting the light regime of urban marine areas and their implications for living marine organisms. To identify relevant sources, a search (Figure 3) was conducted during July 2025 in the Scopus and Web of Science Core Collection bibliographic databases for published, peer-reviewed articles/review articles in English using the following query string: TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Artificial shading” AND marine OR “Artificial Lighting at night” AND marine OR “light pollution” AND marine OR coastal AND “artificial lighting at night” OR Coastal AND “artificial shading” AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”)). The search returned 170 documents, from which 7 were duplicates, and 98 were discarded. A total of 163 were quickly screened by their titles/abstracts, 66 analysed in more depth, and 37 entered the review. The exclusion criteria eliminated all articles whose scope was not relevant to this research, such as articles dealing exclusively with effects on humans or terrestrial species and articles dealing with other environmental stressors, such as plastic pollution. Articles that were not fully accessible to this author were also excluded. The selection criteria included only articles/review articles that dealt with the ecological effects of disturbances to natural light regimes in the urban environment on marine species brought about by urbanisation, urban development, and urban infrastructure, considering the environmental stressors of both artificial light and shade. A backward snowball search was conducted for references mentioned in the texts that met the selection criteria applied to the original set.

Figure 3.

Flow diagram of Integrated Literature Review.

Second, it uses two instrumental cases to examine the remedial measures that were implemented to benefit marine species that suffered from alterations in the natural light regime following the implementation of urban infrastructure. The cases were chosen from initiatives that were already in place to address the disturbance caused by the introduction of shadows and artificial light, and which had already been assessed for their results. The cases in question are the renovation of the Elliot Bay seawall in Seattle, USA, and the Sea Turtle Conservancy’s beachfront lighting programme in Florida, USA. The unit of analysis is the means by which measures were used to mitigate the impact of changes in natural light: light-penetrating surfaces for the former case and lighting retrofits for the latter.

3. Key Factors Regarding the Disruption of the Natural Light Regime Caused by Artificial Lighting and Urban Shading in Urban Marine Areas

3.1. Artificial Light as a Sensory Pollutant

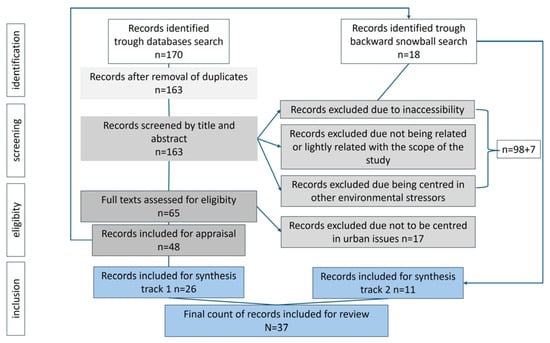

It has already been noticed that, nowadays, urban waters are often lit up, either on purpose or not, for the sake of aesthetics or because of the light reflecting off the water’s surface [18] (Figure 4). The literature remarks the mounting evidence already produced about the negative consequences of artificial illumination for aquatic ecosystems, a phenomenon that shall not be ignored when developing lighting strategies and installations in areas near water bodies [18].

Figure 4.

Hong Kong Bay—CH at nighttime © Daniam Choua/Unsplash.

When taking this alert into account, it is important to first understand how and to what extent light pollution affects the urban marine environment, and the key factors that influence the relationship between marine organisms and the natural light regime. It is accepted that artificial lightscapes exhibit unique spatial, temporal, and spectral patterns that can modify natural light and darkness cycles, resulting in various impacts, including biological organisation [19] and species’ abundance [20] and behaviour [21], as most species developed under natural and constant regimes of moonlight, sunlight, and starlight [9]. In certain cases, the impact originated from artificial lightscapes can be so severe that it may critically undermine fundamental ecological processes such as successful population recruitment [22]. In view of the aforementioned, it is here proposed that, in the context of sustainable lighting of urban marine areas, the following four key factors be given due consideration: light reach, intensity, spectrum, and duration.

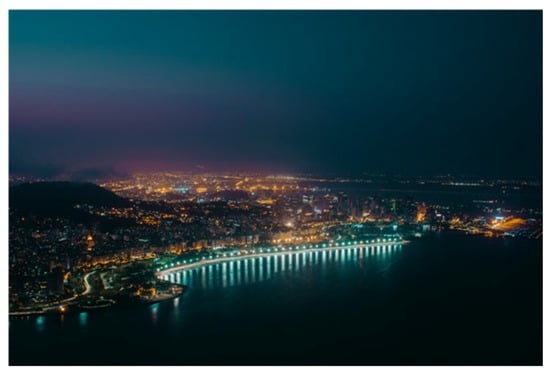

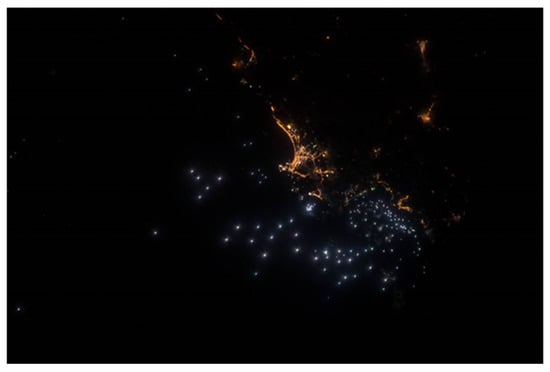

The literature highlights that, despite the highest levels of artificial light being experienced in close proximity to light sources, a misinterpretation may occur if the phenomenon is seen solely as having a localised impact. Some authors [2] explain that, in reality, in urban environments, the cumulative effects of direct light from street lighting (Figure 5) and other sources, as well as light reflected by surfaces, can create a highly irregular lighting environment that extends over a considerably larger area, such as the district scale. A landscape scale can also be attained from the impact of skyglow (Figure 6), i.e., the artificial light scattered in the atmosphere and reflected back [2] and in the phenomenon of ocean sprawl, due to the cumulative effects of artificial light employed to support anthropogenic uses of the marine territory that tend to be concentrated in specific stretches such as exploration sites, shipping routes and fishing grounds [4] (Figure 7). Furthermore, research findings show that the impact of artificial light in space is three-dimensional, extending beyond the water surface, possibly reaching significant depths within the water column (>40 m) [23] and, in some cases, as far as the seafloor [24].

Figure 5.

Light clutter in Flamengo beach, Rio de Janeiro—BR © Gabriel Santos/Unsplash.

Figure 6.

Artificial skyglow (unknown location) © David Kanigan/Pexels CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 7.

Spotlights from fishing boats along the coast of Sanya—CH © European Space Agency/Nightpod.

In addition to spatial reach, observing light intensity is also relevant. Indeed, even low levels of ALAN have been shown to affect marine species, triggering responses such as behavioural changes [25], both at the surface and underwater. For example, sea turtle hatchlings use dim light cues to find their way to the sea, but artificial light coming from built-up areas can confuse them [26]. Underwater, it has already been proven that low levels of ALAN can influence the growth of seagrasses such as Posidonia Oceanica [27] and significantly weaken behavioural rhythms of crustaceans such as Marinogammarus marinus [28]. This is due to the fact that marine organisms have evolutionarily adapted to respond to low levels of light and specific wavelengths of light [24]. Thus, although it is accepted that reducing the overall intensity of an artificial light source is a valid strategy for mitigating its harmful effects [29], simply reducing it may not alter the effects on all processes by the same amount. This is because the relationship is established under more complex terms, and other than the intensity of the light source, the result also depends on other factors, such as the ability of receptors to perceive and respond to light, which varies among and within species [10].

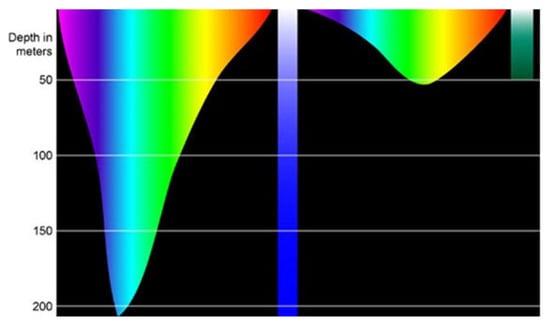

While the adjustment of light intensity might be needed, managing the light spectrum is also a key concern in the marine environment due to the properties of seawater and the spectral sensitivity tuning in marine organisms. The former refers to how different light is attenuated by seawater compared to the atmosphere. Light interacts with the molecules and components of seawater, leading to an attenuation of the first from scattering and absorption, a process which is highly dependent on wavelength [30]. Increasing depth not only diminishes light intensity but also shifts its spectrum [30]. This means that specific bands of light can penetrate the water column more deeply. The maximum transmission of light occurs at shorter wavelengths in deep-sea and clear open ocean environments (blue) and at intermediate wavelengths in coastal waters (green) [31] (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Light penetration in sea water in an open ocean environment (left) and coastal waters environment (right) © National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/Wikimedia Commons.

Modern light technologies have brought white light to the fore (Figure 9), providing the best colour rendering for the human eye [32]. However, they have also created complex colour and brightness patterns in marine lightscapes at night, which were previously unlit or lit only by the comparatively constant spectral signature of moonlight and starlight [9].

Figure 9.

Dock lit at night (unknown location) © Tangerine Shan/Unsplash.

The negative consequences of added artificial light on natural nocturnal environments and ecosystems are, according to some reference [33], often unintentionally overlooked in these contemporary solutions. Still, other authors have shown that light is perceived differently by organisms and that human perceptions alone are often insufficient for understanding the light environment [32]. Research has shown that this could be true when it comes to lighting marine areas, suggesting that the ever-increasing use of white light-emitting diodes (LEDs) will likely exacerbate the prevalence and impact of artificial light in marine ecosystems [24,32]. This is because, compared to older lighting technologies, LEDs emit more short-wavelength light, which penetrates deeper into seawater and falls within the spectral range to which many marine organisms are most sensitive, as many of them have evolved maximum spectral sensitivity at shorter wavelengths [24].

Finally, the implications of the duration of artificial light exposure should also be considered. The changes brought about by its use also have a temporal dimension, as it involves the introduction of light at times and for periods during which it has not previously naturally occurred [4]. This phenomenon is regarded as a novel environmental pressure [4], given the role played over the course of evolution by light and dark cycles as cues for organisms, until the recent introduction of ALAN came to modify them [19]. In brief, the disruptions can be twofold. Initially, it can be driven by the interruption of the periods of both twilight and nighttime, at which points light fades or ceases. Additionally, it may result from illuminating locations over long periods of time and in the same way at different seasons, in a manner that has never before been experienced in the natural world. In general, artificial lights switch on abruptly at dusk and remain on in the same way all night, no matter if the lit area is in use or not (Figure 9), whereas natural light experiences variations with the times of day (24 h cycle), month (lunar cycle), and year (season cycle) [34]. This phenomenon is particularly noticeable in urban marine areas, where artificial light is essential for supporting operations such as those in ports (Figure 10) and on oil platforms, which often need to operate non-stop, twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, all year round.

Figure 10.

Port of Los Angeles—USA operating at nighttime © Lance Cunningham/Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

3.2. Urban Shading as a Sensory Pollutant

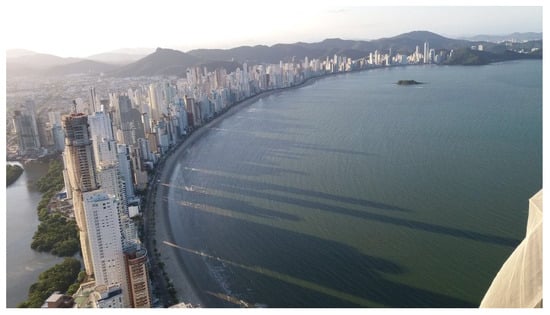

While artificial light pollution dominates research focusing on disturbances to the natural light regime in the marine environment, we should not ignore the fact that urban shading can also be considered a pollutant. It is well known that human-made structures, such as tall buildings constructed on waterfronts (Figure 11), can block sunlight in adjacent marine areas [6] and overwater structures, such as piers (Figure 12), docks, seawalls and wharves, especially large ones that are close to the water’s surface and supported by numerous pilings, can create dark environments underneath them with high-contrast shadow marking their edges [35].

Figure 11.

Shade cast by high-rise buildings in Balneário Camboriú–BR © Cassio Wollmann.

Figure 12.

Shade cast by pier (unknown location) © Gabrielle Polita/Unsplash.

There is growing evidence suggesting that impacts in the long term are likely to be driven by the shade cast by coastal infrastructure. Shade reduces the intensity of sunlight radiation, thereby affecting the physical conditions of marine habitats, such as temperature patterns [6] and causing multiple negative effects to the structure and functioning of biological communities [5]. Previous studies have shown that the low levels of light experienced under marine urban structures can influence the composition of entire subtidal epibiota [36] and fish assemblages [37]; influence fish behaviour [37] and impact the feeding of species that are dependent on light to detect prey [38]. In addition, shade can compromise the survival of autotrophs by restricting the light they need for photosynthesis [5], which affects the recruitment of algae and invertebrates [39]. This results in a decrease in habitat quality for the fish that interact with them along the trophic chain [38]. Still, some authors suggest that vulnerable marine ecosystems are likely to be subjected to greater shade from built structures [6], with marine built structures projected to spread further into the ocean in the future [13].

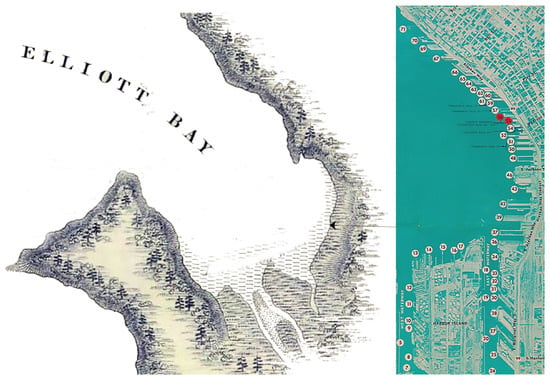

As with its counterpart, light pollution, it has been observed that the shadow caused by the proliferation of marine urban structures over time due to the urbanisation process (Figure 13) may have, besides its local repercussion, wider-reaching impacts on the seascape. For instance, it has been found that the shadow cast by piers affects not only the habitat beneath them as seen before but also serves as a barrier that prevents marine fauna from using the coastal territory extensively as they usually would. This is due to the fact that, under natural conditions, juvenile fish would transit and feed in the shallow coastal waters before venturing to deeper offshore waters at a later stage [35]. However, in a modified built environment, they tend to avoid shaded areas under overwater structures, such as piers. As a result, they do not swim under the shade cast by piers to cross from one lit area to another but instead gather near the piers [38]. This consequently impacts the ecological connectivity of seascapes, which is defined as the degree to which seascapes facilitate or impede movement [40].

Figure 13.

(left). Elliot Bay from the Charles Wilkes expedition survey in 1841. (right). Map of Seattle Harbour circa 1971 showing the proliferation of infrastructure built along the shore © Wikimedia Commons.

4. Remedial Measures to Tackle Alterations in the Light Regime Resulting from Urbanisation

Having reviewed the key themes regarding disturbances to the natural light regime of the marine environment resulting from urbanisation, this section examines remedial measures that have been implemented to benefit marine species that were affected by the consequences of change. The cases are the renovation of the Elliot Bay seawall in Seattle and the Sea Turtle Conservancy Beachfront Lighting Programme in Florida. Though they differ in their approach, the former dealing with urban shading and the latter with artificial light pollution, they share the common purpose of restoring viable conditions that enable target species to thrive in a modified built environment.

4.1. Elliot Bay Seawall Renovation

Following the 2001 Nisqually earthquake, the integrity of Seattle’s seawall was assessed, and it was found that renovation works were needed in order to withstand another extreme event of the same magnitude [41]. When the urbanisation of Seattle’s waterfront took place, many aspects of the native intertidal habitat were lost. Therefore, the renovation offered an opportunity to improve the habitat for local marine species affected by overwater structures and shoreline armouring while continuing to fulfil its function to safeguard the city’s waterfront.

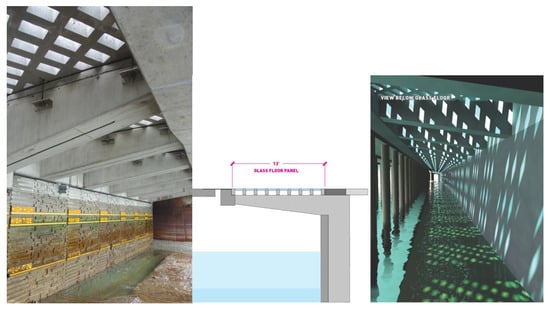

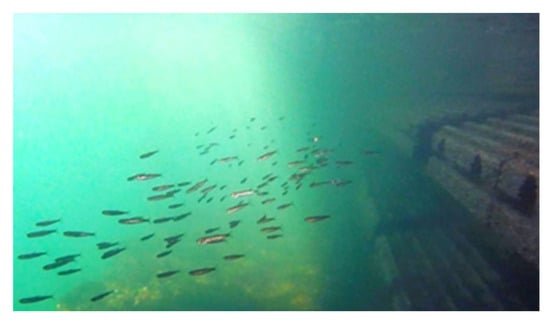

The ecological objectives of the Elliot Bay seawall renovation that took place in 2017 were to establish a tidal habitat corridor for juvenile salmon (Figure 14, right) and improve the health of neighbouring marine ecosystems. Prior to the reconstruction of the seawall, biological monitoring was conducted during the spring and summer of 2012, and researchers observed higher densities of young salmon between the piers than in their shadows [37]. This was because, as seen above, shaded areas under the piers had a significant impact on the behaviour of the young salmon and the invertebrates that they feed on, which were often associated with marine algae that were, in turn, affected by the pier shading to perform photosynthesis. Consequently, juvenile salmon rarely occurred or fed in such areas, most commonly stopping at the edges of the shadows produced by these overwater structures [42]. To address this issue, light-penetration surfaces (LPS) were installed above the seawall, designed in a way to blend with the waterfront promenade above (Figure 14, left). The system comprises precast concrete LPS panels with glass pavers that were specifically shaped, oriented, and positioned to provide optimal natural light to the fauna corridor below [43] (Figure 15, left). The system was intended to provide light to the ‘corridor’ (Figure 15), enabling juvenile salmon to migrate and feed normally. They were also expected to improve productivity under piers by illuminating the aquatic habitat, thereby reducing the detrimental effects of shading under piers and in other low-light areas along the seawall [44].

Figure 14.

(right, not to scale) Salmon corridor project boundary © Field Operations. (left). Top-view of light penetration system © Seattle Department of Transportation/Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 15.

(left) Bottom-view of light penetration system © Seattle Department of Transportation/Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. Cross-section of the habitat corridor—Area 4. © Field Operations (middle); digital mock-up of a lit area underneath a LPS. © Field Operations (right).

Post-construction assessments made in 2018, 2021, and 2022 demonstrated an increase in the use of formerly shaded areas, with observational results suggesting that the installation of the LPS may have encouraged habitat use beneath the pier [44]. A proportion of the juvenile salmon along the seawall was registered using the corridor under the piers lit by LPS (Figure 16), contrasting with the pre-intervention observations, when there were hardly any [44].

Figure 16.

Juvenile salmon swimming in the habitat corridor © University of Washington Wetland Ecosystem Team.

4.2. Sea Turtle Conservancy Beachfront Lighting Programme

For millions of years, sea turtles have nested on beaches at night in Florida, USA, which holds 90% of the nesting sites in the USA [45]. After hatching, the newborn turtles would find their way to the ocean by using light cues to distinguish the brighter ocean from the darker silhouette of the dunes. However, the increase in artificial light pollution resulting from coastal development and population settlement has had a considerable impact on the nesting and hatching behaviour of sea turtles. As these processes are so dependent on the natural light regime, up to 100,000 cases of hatchling disorientation have been recorded in Florida each year [46].

Since 2010, the Sea Turtle Conservancy (STC) has been working to mitigate the impact of beachfront artificial lighting by implementing the Sea Turtle Conservancy Beachfront Lighting Programme [46]. The programme involves carrying out lighting retrofits (Figure 17) and running educational initiatives to restore viable nesting beaches in Florida [45]. The programme acknowledges that the best lighting solution is to have no lighting at all. However, it may be impractical to remove all light, as buildings must meet safety codes. Thus, the programme begins with the removal of non-essential decorative lights. Where lighting is necessary, the three principles for wildlife-friendly lighting set out by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission are adopted: ‘keep it low, keep it shielded, keep it long’. These principles underpin all Sea Turtle Friendly Lighting initiatives. If light somehow illuminates the beach, they ensure that disruption to nesting turtles and hatching behaviour is minimised [46].

Figure 17.

Lighting retrofit project in Florida—USA © Sea Turtle Conservancy.

The first principle, ‘keep it low’, refers to both the mounting height of a lighting fixture, which should be placed as low as possible on the structure, and the light output intensity, which should be as dim as possible for the intended purpose. The second principle, ‘keep it long’, is based on the knowledge that sea turtles are less disturbed by longer wavelengths of light; thus, lamp fixtures should be fitted with long-wavelength bulbs, preferably with an optimal wavelength of around 580 nanometres, which are seen as red and amber in the light spectrum (Figure 17, right). The third principle, ‘keep it shielded’, involves shielding the bulb, lamp, or glowing lens from view on the beach, to ensure all light is directed is projected below the horizontal, rather than out onto the beach [46].

Since the introduction of the Beachfront Lighting Programme in 2010, STC has successfully retrofitted approximately 350 properties, darkened around 76 kilometres of beach, and upgraded 36,000 light bulbs or fixtures to a type of lighting that is more wildlife-friendly, minimising the need for residents to change their habits during the nesting season [46]. Post-intervention data suggest that disorientations from artificial lighting dropped to zero following the 2011 retrofits and remained at this level throughout the 2012 season [45].

5. Discussion

This study has demonstrated that although ALAN and urban shading have mostly been studied independently, combating light pollution and ensuring light penetration are two sides of the same sustainability coin, as both can influence the marine environment and the organisms that depend on light in different forms (e.g., sunlight and moonlight) to fulfil their needs, such as photosynthesis, foraging, and nesting. In short, the argument developed in this work is that these two phenomena are different manifestations of the same underlying issue: disruption to natural light regimes. Both can be considered sensory pollutants with multiple effects on aquatic biodiversity, which has evolved in response to natural light. Therefore, those aspiring to provide sustainable lighting in urban marine areas must consider standards for both daytime and nighttime light regimes.

It has been examined how urbanisation can lead to changes in marine lightscapes, either through the introduction of artificial light or the reduction in light caused by shade from built structures. In both cases, the origin of these factors is the same: they serve to support urban functions and meet human needs. Thus, we should recall what is remarked in the literature that “many landscapes now have to accommodate the needs of both humans and other species” [47] (p. 558). Due to the increase in coastal urbanisation and ocean sprawl, it appears that the seascape is no exception. A trade-off may be necessary to balance the needs of human and non-human stakeholders, with light representing a key component of the pact. However, finding this balance is not straightforward, as it has already been recognised that urban waterfronts are now so detached from the natural ecosystems’ conditions that it may not be feasible to try to return them to their historical configuration [35]. Therefore, given the need to reconcile the needs of humans and non-humans, and assuming that restoring natural conditions may be unfeasible in highly modified built environments, this study recognises that achieving sustainable lighting requires consideration of the many factors that influence the disruption of light regimes, all of which must be taken into account if one wishes to mitigate their environmental impact in the context of the artificialisation of the marine environment. Additionally, we shall add the complex distribution of agency among humans and non-humans. This encompasses human technology, building codes, and performance requirements on the one hand, and seawater properties and marine species that respond differently to marine light conditions on the other. As a result, it is likely that solutions will need to be adapted to meet specific goals and target species. In this sense, more research is needed to determine how the introduction of regulatory mechanisms and incentives could foster the inclusion of programmatic requirements in building specifications that consider other-than-human elements, encouraging designers and project owners to explore innovative solutions, such as those seen in the two cases.

In light of the intricate nature of the theme, this study identifies and synthesises four key domains that are important for planning and designing wildlife-friendly lighting in marine urban areas. Drawing on existing literature from marine science, ecology and biology, the study contributes to making the topic more accessible to professionals from outside these fields, such as architects, designers, and urban planners, who may find themselves dealing with the subject at some point of their practice and aspire to make their interventions more ecologically sustainable, for which a comprehensive overview could serve as a valuable starting point.

The domains that deserved the focus of this work refer to light reach, intensity, spectrum, and duration. It has been emphasised that, given that broader-scale impacts can be caused in different ways by the introduction of artificial light and shade, these phenomena should not be interpreted as having only a local impact. The reach of light can be approached in two ways: preventing light from reaching places where it is not desired, such as at nesting sites, and providing light so that it reaches places where it is needed, such as underneath piers and other similar structures over water. As we have seen in the cases studied, both situations may require proper management, and design solutions can be used to achieve these goals. Nevertheless, we could see that a design solution might not always suffice if it only addresses one aspect of the problem, as is the case with reducing light intensity. Although the management of light intensity is generally welcomed as a mitigation measure, when we reviewed the subject, we found that low levels of light can still harm certain species and that simply reducing the intensity may not mitigate the impact sufficiently. Therefore, in certain cases, considering darkness as the only solution may be appropriate, and preserving dark seas from the influence of urban areas could, in the future, become as significant as the contemporary advocacy to conserve dark skies. Where this is not possible, reducing the intensity of the lighting and taking other mitigation measures, such as shielding light sources and managing the light spectrum, will likely be necessary. These combined measures were extensively used in the Beachfront Lighting Programme. Similarly, although the preliminary data produced is encouraging, the potential of light penetration measures to address the issue of artificial shading remains scarce, given that the light intensity they provide is only a fraction of what was available prior to the introduction of the infrastructure. (In Elliot Bay, the mean Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR) was measured under ambient conditions and under different light penetration surfaces. The results were as follows: 1028.2 PAR for ambient conditions, 142.8 PAR for grating, 43.8 PAR for glass blocks, and 11.0 PAR for solar tubes (Cordel et al., 2017) [48]). For this reason, it has been defended that, when feasible, removing infrastructure that causes artificial shading should not be discarded as an option, and light penetration systems should be used where it is not possible to decrease the shade footprint due to technical or infrastructure requirements [48].

This review shows that the light spectrum, the visual sensitivity of marine species to specific wavelength bands, and the spectral signatures of artificial lighting technologies are closely linked and should be managed accordingly. This association formed the basis of the Sea Turtle Beachfront Light Programme, which was managed extensively. The issue of the light spectrum is less pronounced in relation to shading, since mitigation measures would typically aim to restore some natural light to darkened areas. Nevertheless, the literature has already suggested that artificial light could potentially be used as a tool to mitigate the shading caused by man-made structures under certain conditions [49,50]. In this case, adjusting the spectral signature of the lighting sources would be a point to be observed.

Lastly, the time factor was reviewed. Although it has already been demonstrated that light duration is a relevant aspect, as the presence of light at abnormal times can alter natural activity patterns of living organisms [28], this topic still receives the least attention from research or mitigation measures compared to other issues, such as light spectrum and intensity. However, there are currently dynamic lighting systems available on the market that are designed to emulate natural conditions by autonomously adjusting the timing and intensity of artificial light at different times. Initiatives using such systems to mitigate the impact on biodiversity have already been implemented in terrestrial settings [51]; thus, the same strategy of time management could be tested in urban marine areas, and further research on this particular topic is still needed.

It should be noted, however, that this paper does not aim to review all the impacts arising from human alteration of the natural light regime and its consequences for the marine environment and species. Although some of these are exemplified, the list is intended to be illustrative rather than exhaustive. For a more detailed discussion of this topic, please refer to the works of Davies et al. [9], Marangoni et al. [10], and Trethewy et al. [6]. For a broader discussion on how to mitigate the impacts of light pollution, please refer to the works of Gaston et al. [32] and Reilly et al. [29].

This study draws on cases that have been implemented relatively recently. Although care was taken in selecting cases that present preliminary results, and these suggest the effectiveness of the interventions, it should be noted that a more in-depth assessment of their effects on marine biodiversity requires a longer observation period. That said, the difficulty of making predictions about the success of these interventions, beyond their effect on the target species and including the marine ecosystem as a whole, as well as the cascade effects, is a limitation of this study.

Funding

This research did not receive any funding from public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article. The original data presented in the study are available in the DOIs/URLs indicated in the reference list.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ALAN | Artificial light at night |

| STC | Sea Turtle Conservancy |

| LPS | Light Penetration Surfaces |

| PAR | Photosynthetically Active Radiation |

References

- Dominoni, D.M.; Nelson, R.J. Artificial light at night as an environmental pollutant: An integrative approach across taxa, biological functions, and scientific disciplines. J. Exp. Zool. Part A Ecol. Integr. Physiol. 2018, 329, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaston, K.J.; Bennie, J.; Davies, T.W.; Hopkins, J. The ecological impacts of nighttime light pollution: A mechanistic appraisal. Biol. Rev. 2013, 88, 912–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katabaro, J.M.; Yan, Y.; Hu, T.; Yu, Q.; Cheng, X. A review of the effects of artificial light at night in urban areas on the ecosystem level and the remedial measures. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 969945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaston, K.J.; Duffy, J.P.; Gaston, S.; Bennie, J.; Davies, T.W. Human alteration of natural light cycles: Causes and ecological consequences. Oecologia 2014, 176, 917–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardal-Souza, A.L.; Dias, G.M.; Jenkins, S.R.; Ciotti, Á.M.; Christofoletti, R.A. Shading impacts by coastal infrastructure on biological communities from subtropical rocky shores. J. Appl. Ecol. 2017, 54, 826–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trethewy, M.; Mayer-Pinto, M.; Dafforn, K.A. Urban shading and artificial light at night alter natural light regimes and affect marine intertidal assemblages. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 193, 115203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaston, K.J.; Gaston, S.; Bennie, J.; Hopkins, J. Benefits and costs of artificial nighttime lighting of the environment. Environ. Rev. 2015, 23, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, M.; Rossi, F.; Benedetti-Cecchi, L.; Maggi, E. Ecological consequences of artificial light at night on coastal species in natural and artificial habitats: A review. Mar. Biol. 2025, 172, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, T.W.; Duffy, J.P.; Bennie, J.; Gaston, K.J. The nature, extent, and ecological implications of marine light pollution. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2014, 12, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangoni, L.F.B.; Davies, T.; Smyth, T.; Rodríguez, A.; Hamann, M.; Duarte, C.; Pendoley, K.; Berge, J.; Maggi, E.; Levy, O. Impacts of artificial light at night in marine ecosystems—A review. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 5346–5367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugan, J.; Airoldi, L.; Chapman, M.; Walker, S.; Schlacher, T. Estuarine and Coastal Structures: Environmental Effects, A Focus on Shore and Nearshore Structures. In Treatise on Estuarine and Coastal Science; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; Volume 8, pp. 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, W.L.B.; Knights, A.M.; Bridger, D.; Evans, A.J.; Mieszkowska, N.; Moore, P.J.; O’Connor, N.E.; Sheehan, E.V.; Hawkins, R.C.T.S.J. Ocean Sprawl: Challenges and Opportunities for Biodiversity Management in a Changing World. In Oceanography and Marine Biology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bugnot, A.B.; Mayer-Pinto, M.; Airoldi, L.; Heery, E.C.; Johnston, E.L.; Critchley, L.P.; Strain, E.M.A.; Morris, R.L.; Loke, L.H.L.; Bishop, M.J.; et al. Current and projected global extent of marine built structures. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 4, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longcore, T.; Rich, C. Ecological light pollution. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2004, 2, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, E.; Hine, R. Pollutant. In A Dictionary of Biology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008; Available online: https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100335155 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Allaby, M. Pollution. In A Dictionary of Ecology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; Available online: https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/acref/9780191793158.001.0001/acref-9780191793158-e-4398 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- de Souza, M.T.; da Silva, M.D.; de Carvalho, R. Integrative review: What is it? How to do it? Einstein-Sao Paulo 2010, 8, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grubisic, M. Waters under Artificial Lights: Does Light Pollution Matter for Aquatic Primary Producers? Limnol. Oceanogr. Bull. 2018, 27, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, M.J.; Sullivan, S.M.P.; Gray, S.M. Artificial Lighting at Night in Estuaries—Implications from Individuals to Ecosystems. Estuaries Coasts 2019, 42, 309–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, A.; Whitfield, A.K.; Cowley, P.D.; Järnegren, J.; Naesje, T.F. Potential effects of artificial light associated with anthropogenic infrastructure on the abundance and foraging behaviour of estuary-associated fishes. J. Appl. Ecol. 2013, 50, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, D.; Mayer-Pinto, M.; Clark, G.; Dafforn, K.; Brassil, W.; Becker, A.; Johnston, E. Coastal urban lighting has ecological consequences for multiple trophic levels under the sea. Sci. Total. Environ. 2017, 576, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simantiris, N.; Vardaki, M.Z.; Dimitriadis, C.; Netzipi, O.; Malaperdas, G. Assessing Light Pollution Exposure for the Most Important Sea Turtle Nesting Area in the Mediterranean Region. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, T.J.; Wright, A.E.; McKee, D.; Tidau, S.; Tamir, R.; Dubinsky, Z.; Iluz, D.; Davies, T.W. A global atlas of artificial light at night under the sea. Elem. Sci. Anthr. 2021, 9, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, T.W.; McKee, D.; Fishwick, J.; Tidau, S.; Smyth, T. Biologically important artificial light at night on the seafloor. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanna, G.; Domenici, P.; Maggi, E. Artificial light at night alters the locomotor behavior of the Mediterranean sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 206, 116782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmon, M. Artificial night lighting and sea turtles. Biologist 2003, 50, 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonare, L.D.; Basile, A.; Rindi, L.; Bulleri, F.; Hamedeh, H.; Iacopino, S.; Shukla, V.; Weits, D.A.; Lombardi, L.; Sbrana, A.; et al. Dim artificial light at night alters gene expression rhythms and growth in a key seagrass species (Posidonia oceanica). Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Underwood, C.N.; Ford, A.T.; Robson, S.C.; Wijnen, H. Behavioural rhythms of two amphipod species Marinogammarus marinus and Gammarus pulex under increasing levels of light at night. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0329449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, C.E.; Larson, J.; Amerson, A.M.; Staines, G.J.; Haxel, J.H.; Pattison, P.M. Minimizing Ecological Impacts of Marine Energy Lighting. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, W. Light in the sea: The optical world of elasmobranchs. J. Exp. Zool. 1991, 256, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerlov, N.G. Optical Oceanography; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Gaston, K.J.; Davies, T.W.; Bennie, J.; Hopkins, J. Reducing the ecological consequences of night-time light pollution: Options and developments. J. Appl. Ecol. 2012, 49, 1256–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, C.P.; Zielinska-Dabkowska, K.M.; Schroer, S.; Jechow, A.; Hölker, F. A Systematic Review for Establishing Relevant Environmental Parameters for Urban Lighting: Translating Research into Practice. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, S. New Global Atlas: Bathed in a Sea of Artificial Light. SciTechDaily. 2022. Available online: https://scitechdaily.com/new-global-atlas-bathed-in-a-sea-of-artificial-light/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Munsch, S.H.; Cordell, J.R.; Toft, J.D. Effects of shoreline armouring and overwater structures on coastal and estuarine fish: Opportunities for habitat improvement. J. Appl. Ecol. 2017, 54, 1373–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasby, T. Effects of shading on subtidal epibiotic assemblages. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1999, 234, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munsch, S.H.; Cordell, J.R.; Toft, J.D.; Morgan, E.E. Effects of Seawalls and Piers on Fish Assemblages and Juvenile Salmon Feeding Behavior. North Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2014, 34, 814–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy-Anderson, J.T.; Able, K.W. An Assessment of the Feeding Success of Young-of-the-Year Winter Flounder (Pseudopleuronectes americanus) near a Municipal Pier in the Hudson River Estuary, USA. Estuaries 2001, 24, 430–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blockley, D.J. Effect of wharves on intertidal assemblages on seawalls in Sydney Harbour, Australia. Mar. Environ. Res. 2007, 63, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabor, G.; Bankova-Todorova, M.; Ayram, C.; Stupariu Garcia, L.; Kapos, V.; Olds, A. Ecological Connectivity: A bridge to preserving biodiversity. In Frontiers 2018/19 Emerging Issues of Environmental Concern; United Nations Environment Pro-gramme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dunagan, C. New Seattle Seawall Improves Migratory Pathway for Young Salmon|Salish Sea Currents Magazine. Encyclopedia of Puget Sound. 2020. Available online: https://www.eopugetsound.org/magazine/IS/seawall (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Cordell, J.R.; Munsch, S.H.; Shelton, M.E.; Toft, J.D. Effects of piers on assemblage composition, abundance, and taxa richness of small epibenthic invertebrates. Hydrobiologia 2017, 802, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Society of Landscape Architects. (n.d.). Central Seawall Project|2017 ASLA Professional Awards. Available online: https://www.asla.org/2017awards/320768 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Toft, J.; Cordell, J.; Oxborrow, B.; Kobelt, J.; Toler-Scott, C.; Caputo, M.; Ellis, A.; Accola, K.; Burch, C. University of Washington—2022 Seawall Data Report; University of Washington/School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences: Seattle, WA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://depts.washington.edu/wetlab/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/2022-UW-Data-Report-compressed.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Barshel, N.; Bruce, R.; Grimm, C.; Haggitt, D.; Lichter, B.; McCray, J.; Ankersen, T.; Appelson, G.; Shudes, K. Sea Turtle Friendly Lighting-A model Ordinance for Local Governments & Model Guidelines for Incorporation into Governing Documents of Planned Communities: Condominiums, Cooperatives and Homeowner’s Associations; University of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2014. Available online: https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/35334/noaa_35334_DS1.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Sea Turtle Conservancy. (n.d.). Beachfront Lighting. Sea Turtle Conservancy. Available online: https://conserveturtles.org/program/beach-lighting/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Hobbs, R.J.; Higgs, E.; Hall, C.M.; Bridgewater, P.; Chapin, F.S.; Ellis, E.C.; Ewel, J.J.; Hallett, L.M.; Harris, J.; Hulvey, K.B.; et al. Managing the whole landscape: Historical, hybrid, and novel ecosystems. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2014, 12, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordell, J.R.; Toft, J.D.; Munsch, S.; Goff, M. Benches, Beaches, and Bumps: How Habitat Monitoring and Experimental Science can Inform Urban Seawall Design. In Living Shorelines: The Science and Management of Nature-Based Coastal Protection; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 421–438. [Google Scholar]

- Ono, K.; Simenstad, C.A. Reducing the effect of overwater structures on migrating juvenile salmon: An experiment with light. Ecol. Eng. 2014, 71, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, N.; Hoey, A.S.; Bishop, M.J.; Bugnot, A.B.; Herbert, B.; Mayer-Pinto, M.; Sherman, C.D.H.; Foster-Thorpe, C.; Vozzo, M.L.; Dafforn, K.A. Shining the light on marine infrastructure: The use of artificial light to manipulate benthic marine communities. J. Appl. Ecol. 2025, 62, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.M. Mitigating the impacts of street lighting on biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2023, 378, 20220355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.