Abstract

Research suggests that overweight/obese adults (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) have an elevated risk of cognitive decline. Although exercise is recommended to improve both physical and cognitive health, adherence is often low in this population. Virtual reality (VR) is an emerging strategy that may enhance exercise engagement. This pilot study compared the effects of traditional (TRAD) cycling and VR-based exercise on cognitive performance and prefrontal cortex (PFC) oxygenation (O2Hb). Eleven adults (M = 6, F = 5; BMI: 31.1 ± 2.8 kg/m2; VO2max: 30.4 ± 5.7 mL/kg/min) completed a VO2max test and two 16 min moderate-intensity cycling sessions (TRAD, VR) on separate days, each followed by a Stroop task (four rounds of 30 trials). Exercise intensity did not differ between conditions (TRAD: %HRmax 73.9 ± 4.2, RPE 12.9 ± 1.5, BLa− 2.5 ± 1.3; VR: %HRmax 74.0 ± 5.6, RPE 12.7 ± 1.4, BLa− 2.7 ± 1.7). Stroop accuracy was similar between conditions; however, response time was faster post-TRAD in round two (p = 0.005) and round three (p = 0.004). No significant differences in PFC O2Hb were observed. These preliminary results suggest that both TRAD cycling and VR-based exercise are feasible modes of moderate-intensity exercise in overweight/obese adults, with largely comparable post-exercise cognitive outcomes. Larger, counterbalanced studies are warranted.

1. Introduction

Obesity is a growing issue in the United States, with approximately 74% of Americans categorized as overweight or obese (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]) [1]. While obesity is commonly associated with negative effects on one’s physical health, it can also have significant implications to one’s cognitive health [2]. Specifically, a body mass index (BMI) over 30 kg/m2 (i.e., obese) has been associated with the atrophy of grey matter in the brain and a decrease in overall brain size, including the prefrontal cortex (PFC) [3,4]. The PFC is a control center of the brain that plays a central role in executive functioning and modulates reward-seeking behaviors and dietary decision-making [5]. Cognitive dysfunction, especially altered regulation to executive function-such as impulse control, decision-making, and working memory, can result in serious health consequences including poorer academic performance, reduced quality of life and an elevated risk of all-cause mortality [6]. When executive function is compromised, individuals may experience a reduction in self-control and are therefore more susceptible to unhealthy eating behaviors that can contribute to the development of obesity [7].

Exercise is commonly prescribed to improve physical and cognitive health; however, over half of the adults in the U.S. do not meet the recommended 150 min of moderate-intensity exercise each week [8]. Many adults report lack of motivation, time, and gym access as barriers to physical activity [9]. As a result, many overweight and obese individuals struggle with adhering to an exercise program, putting them at higher risk for cognitive dysfunction. This increased risk for cognitive dysfunction in overweight and obese individuals can be mitigated through exercise. Cognitive gains associated with aerobic exercise are linked to enhanced cerebral blood flow, increasing the amount of oxygen delivered to the brain [10]. Blood flow has been shown to specifically increase in the subcallosal and anterior cingulate gyrus of the frontal lobe. Monitoring blood flow in these two areas of the frontal lobe is crucial as they are involved in regulating executive cognitive functions. Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) is a non-invasive neuroimaging tool that can be used to monitor localized changes in cortical oxygenation. The advantages of fNIRS are that it is portable and provides real-time information regarding hemodynamic changes associated with cortical activity [11]. This makes fNIRS particularly well-suited for examining how exercise influences brain activity and cognitive engagement, allowing researchers to gain valuable insight into potential mechanisms by which exercise may enhance cognitive function. In particular, increased PFC oxygenation is believed to play an important role in governing executive functioning. Specifically, the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (left-DLPFC) shows high activation during memory tasks and impacts processing speed, and research indicates this area of the brain may be impacted by acute exercise bouts [12,13]. Since exercise has been shown to increase PFC oxygenation and activation, consistent exercise may improve cognitive function in overweight and obese individuals allowing researchers to gain valuable insight into potential mechanisms by which exercise may enhance cognitive function.

A new technique that is gaining popularity with its application to exercise is virtual reality (VR). VR is an immersive, computer-generated environment that replaces the user’s physical surroundings and induces a strong sense of presence. Improvements in VR technology and increased access to VR headsets have increased their prevalence in the fitness industry. Previous research has shown VR’s ability to provide relief from discomfort caused by traditional (TRAD) exercise for individuals in the obese population [14]. This relief allows individuals to engage in longer exercise bouts, which can aid in cognitive improvements. Research has also shown that VR has the potential to improve exercise adherence in an overweight population by increasing enjoyment of activity [15]. This study examined the activation of the right dorsolateral PFC during exercise; however, no research has investigated post-exercise cognitive performance and global PFC activation. In addition to relieving discomfort and increasing exercise enjoyment, VR-based exercise has been shown to decrease BMI and depression and increase exercise immersion [16]. When comparing an indoor biking group with VR and an identical indoor biking group without VR, the group with VR-based biking saw greater physical changes than the group without, and positive mental impacts both during and after training. This increased immersion and enjoyment during exercise with VR amplifies its physiological effects and increases adherence to an exercise plan. Since exercise has been shown to increase cognition and VR can increase exercise adherence, VR-based exercise may offer the opportunity to improve cognition and alter activation in the PFC for overweight or obese individuals. VR is often discussed in conjunction with exergames, or video games that require physical exercise to play [17]. The multitasking required to engage in VR and exercise changes the brain’s capacity and enhances various cognitive functions such as attention, observation, and inhibition.

Overall, the introduction of VR-based exercise provides an engaging and safe way to exercise, which bridges the gap between physical activity and entertainment. Research shows that acute exercise leads to improvements in cognitive function [13], and since VR provides an alternative method of exercise, it may allow individuals in the overweight population to experience exercise in a more enjoyable and immersive manner, minimizing the risk of cognitive dysfunction. Despite growing interest in VR-based exercise, limited research has directly compared post-exercise cognitive performance and PFC activation via fNIRS between VR-based and TRAD exercise in overweight/obese adults.

Based on previous research, the primary aim of this pilot study was to determine whether VR-based exercise exhibits similar physiological (heart rate (HR), blood lactate (BLa−)), perceptual (rating of perceived exertion (RPE)), and cognitive responses (Stroop accuracy and response time) as TRAD exercise in overweight/obese adults. A secondary aim was to determine whether post-exercise PFC oxygenation differed between exercise modalities. We hypothesized that no significant differences would be observed between VR-based and TRAD exercise trials. This would indicate that VR-based exercise exhibits the same physical and cognitive impacts as TRAD exercise in the overweight population.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 11 participants (M = 6, F = 5) were recruited via a randomized university email and flyers that were dispersed throughout campus (see Table 1). Prior to providing written consent, the risks, benefits, and procedures were outlined, and a health history questionnaire was filled out. Briefly, eligible participants had to be between 18 and 29 years old, overweight or obese (BMI > 27 kg/m2 and at least “poor” body fat % classification according to the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) guidelines), and sedentary (<1 h/week of regular exercise) [18]. The BMI threshold was selected to ensure inclusion of individuals with both elevated BMI and excess adiposity. Individuals with reported neurological impairment or disease such as dementia, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, or stroke, or those taking antidepressants, were not eligible to participate in the study. If subjects had physical impairments that prevented them from performing a maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max) test on a stationary bike or engaging in a VR-based workout, they were also excluded from the study. All study procedures were performed in the Exercise Physiology Laboratory at UNI (approved IRB protocol FY24-182) under similar environmental conditions and at the same time of day (±2 h).

Table 1.

Subject characteristics.

2.2. Study Design

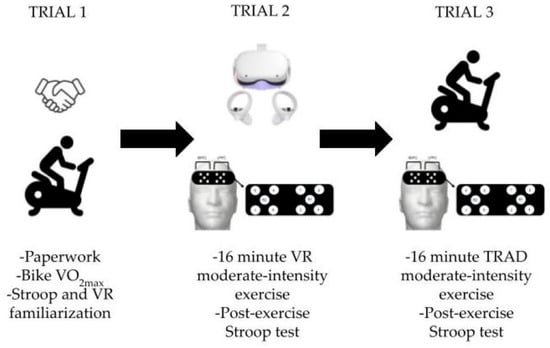

Each participant completed baseline testing (trial 1), followed by a VR-based workout (trial 2), and finally a TRAD cycling workout (trial 3), separated by 3–10 days to ensure adequate participant recovery. The VR trial was conducted first to establish an individualized target heart rate range, which was then matched during the TRAD cycling trial. Although this approach ensured comparable exercise intensity, the lack of counterbalancing is acknowledged as a limitation. Baseline measures included a maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max) test and body composition via bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA). In the first trial, the participants’ anthropometric measures were recorded, and a maximal bike exercise was performed to obtain a measure of cardiorespiratory fitness, as well as a maximum HR value from which moderate-intensity exercise could be prescribed. In the second and third trials, participants began each trial by being fitted with an HR monitor before exercising at moderate intensity for 16 min. A measure of HR was continuously collected throughout each exercise trial. A BLa- sample was collected immediately post-exercise. Following the exercise portion of the trial, participants had a 10 min rest period before completing the cognitive task. During this time, participants were asked to refrain from using electronic devices and to limit communication with any research team members present in the room. Finally, the participant was fitted with the fNIRS headcap and the cognitive task was administered. An outline of the study design is shown in Figure 1. This moderate intensity was defined as a RPE between 12–13 [18]. Moderate intensity was also defined as 64–76% of the participant’s HRmax which was obtained from the baseline testing in trial 1. The participant’s HR was monitored throughout the second and third trials to ensure moderate-intensity exercise was maintained. If HR deviated outside the moderate-intensity exercise range, power was decreased by 5% increments until the participant was back within 64–76%HRmax.

Figure 1.

Study Outline. TRAD = traditional exercise trial, VO2max = maximal oxygen consumption trial, VR = virtual reality.

2.3. Baseline Measures

Following approval and written signature of the consent form, each participant’s height (nearest 0.1 cm) and weight (nearest 0.1 kg) were measured using a stadiometer and scale, respectively. These measures were then used to calculate each participant’s BMI. In addition, body fat percentage was determined using a bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) device (InBody 720, Carritos, CA, USA).

Following the aforementioned initial measurements, the participant performed a VO2max test on an electronically braked cycle ergometer (Lode, Groningen, The Netherlands) to determine cardiovascular fitness (i.e., VO2max). Following a 5 min self-select warm-up, participants were connected to a metabolic cart (Parvomedics, Sandy, UT, USA) in order to measure oxygen consumption (VO2) and carbon dioxide production (VCO2). During the VO2max test, participants were asked to maintain 70–80 revolutions per minute (RPM). Heart rate was measured continuously using a PolarTM HR monitor (Verity Sense, Polar Electro Inc., Woodbury, NY, USA) and workload increased every 3 or 4 s (20 watt ramp for males beginning at 40 watts and 15 watt ramp for females beginning at 30 watts) until cadence dropped below 60 RPM despite verbal encouragement or participants reached volitional fatigue. That said, participants were asked to stop and inform the researchers if they experienced any chest pain, dizziness, or faintness. VO2max required two of the following four criteria to be met: respiratory exchange ratio (RER) > 1.15, within ±10 bpm of age-predicted maximal HR, VO2 plateau of <150 mL/min, or RPE > 17. VO2max was determined by the highest value achieved using a 15 s average. Participants’ HR, in combination with workload in watts, were used to calculate appropriate moderate-intensity exercise levels for each participant’s TRAD and VR-based exercise protocols.

2.4. VR Workout

During the VR-based exercise trial, participants completed a 16 min exercise session. After the duration of the workout, participants’ HR, RPE and BLa− levels were measured. The Meta Quest 3 was the VR headset used for all participants. Participants completed the exercise using the “Next Level HIIT” workout in the FitXR app on the VR headset. Based on the categories in the FitXR program, this workout was considered moderate-intensity exercise. A virtual instructor guided subjects to follow certain movements using the controllers to hit floating orbs to move on to the next exercise. The instructor would show the participants the exercises while also communicating with the viewer before the exercise was performed. Movements included extending arms, squats, and side lunges to move their body and increase their HR. The instructor’s voice was heard throughout the workout, offering encouragement and reminders of how much time was left in a particular round of exercises. An iPad was synched to the headset and used to monitor the participants during the workout and make sure they complete the correct movements. Immediately following exercise, the participants’ BLa− and average RPE through the exercise were recorded. Ten minutes post-exercise, the subjects donned the fNIRS headcap and completed the Stroop task.

2.5. TRAD Workout

The TRAD exercise trial consisted of a 16 min cycling exercise on a stationary cycle ergometer (the same duration as the VR trial). During the cycling exercise the subject’s HR was monitored to ensure they were in a moderate intensity zone similar to the HR zone maintained during the VR-based exercise session. Subjects’ HR, RPE, BLa− levels, and average watts were recorded after the exercise was concluded. Similarly to the VR-based exercise session, subjects waited 10 min before fNIRS measurement and Stroop tasks were started.

2.6. Blood Lactate

Participants’ whole BLa− levels were measured immediately following exercise in both the VR-based and TRAD exercise trials. Measuring BLa− allows for an accurate representation of exercise intensity and shows the balance between the amount of lactate produced and metabolized at a specific time. The BLa− values were collected and compared after the control and experimental trials for each participant. A lancet was used to puncture the bottom of the earlobe, and a droplet of blood (~1 µL) was collected using a handheld analyzer device (Nova Biomedical, Waltham, WA, USA). The device was calibrated following manufacturer instructions before each trial.

2.7. Cognitive Task

Cognitive evaluation was measured post-exercise using the Stroop task. The Stroop task is one of the most widely used measures of inhibition [19]. Participants were presented with a printed word of a color appearing in different ink. Subjects were expected to select the color of the ink rather than the printed word itself [20]. Two conditions are administered during the duration of the Stroop task. A congruent condition is displayed when the word printed is the same color as the ink of the word (e.g., the word green is shown in green). Incongruent condition is exhibited when the word presented has a different ink than the printed version (e.g., the word green is shown in red). Congruent and incongruent trials were presented in equal proportion and randomized. Participants completed four rounds with 30 trials in each round and an intertrial interval of 1500 milliseconds (1.5 s). The Stroop task measures response time and accuracy by matching the words. The 10 min rest period prior to the Stroop task was chosen as similar short time periods have been used previously with positive results on Stroop performance [21,22]. During this time, participants were instructed to refrain from using electronic devices and limit communication with any research team members present in the room. Response time and accuracy were averaged across congruent and incongruent trials for each round and used for statistical analyses.

2.8. Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS)

The participants’ PFC oxygenated hemoglobin (O2Hb) was measured during the cognitive evaluations using the fNIRS device post-exercise. The unit consists of a headband with eight optodes and two receivers with an interoptode distance of 3.5 cm and a signal sampling of 10 Hz. Four LED optodes combined with one receiver were placed over the right and left PFC regions creating an 8 × 2 configuration. Optode placement followed the modified international electroencephalogram 10–20 system. The left prefrontal cortex (LPFC) regions are identified as Fp1 and F7 using channels 1–4. The right prefrontal cortex (RPFC) regions are identified as Fp2 and F8 using channels 5–8. The fNIRS cap was placed 2 cm above the nasion site and centered at the Fpz location (located superior to the nose bridge). To remove any potential external artifacts, the fNIRS signal was filtered using a low-pass filter of 0.1 Hz. The values collected by each channel were filtered in Oxysoft software (Artinis Medical Systems, Elst, The Netherlands), placed in Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, CA, USA), and averaging of the values across all trials was completed in Prism (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). The fNIRS device detects changes in levels of oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin in the brain and may indicate sites of neural activation [23].

2.9. Statistical Analysis

A two-way repeated measures ANOVA was conducted to evaluate differences in cognitive performance across the four Stroop task rounds between TRAD and VR-based exercise conditions. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were adjusted using Bonferroni correction. A paired t-test was used to compare average PFC O2Hb between exercise conditions. Descriptive statistics (mean ± standard deviation) were calculated for key physiological variables, including % HR max, RPE, and BLa−, to confirm comparable exercise intensity across conditions. All results are expressed as means ± standard deviations and a partial eta-squared (n2p) was used for the magnitude of the mean effect. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism, version 9.4.1 with a significance level set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Heart Rate and RPE

There was no significant difference in average HR or % HR max between the VR-based and TRAD exercise trials (Table 2). The % HR max values for the participants were 74.0 ± 5.6 and 73.9 ± 4.2 for the VR-based and TRAD exercise trials, respectively. These values fall within the 64–76% range which the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) defines as moderate-intensity exercise [16]. There was no significant difference in session RPE between the VR-based and TRAD exercise trials (Table 2). The RPE values were 12.7 ± 1.4 and 12.9 ± 1.5 for the VR-based and TRAD exercise trials respectively. These values fall within the 12–13 range that the ACSM defines as moderate-intensity exercise [18].

Table 2.

Exercise intensity variables.

3.2. Blood Lactate

There was no significant difference in BLa− levels between the VR-based and TRAD exercise trials (Table 2). These values were 2.7 ± 1.7 mmol/L and 2.5 ± 1.3 mmol/L for the VR-based and TRAD exercise trials, respectively.

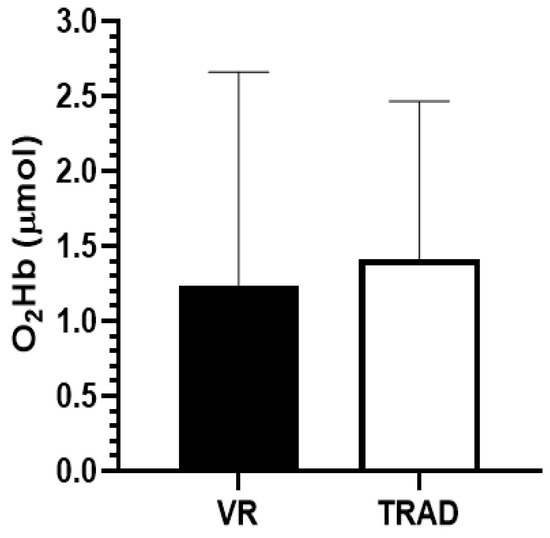

3.3. fNIRS

There was no significant difference in PFC O2Hb during the Stroop test between the VR-based (1.24 ± 1.42 µmol) and TRAD (1.42 ± 1.05 µmol) exercise trials (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Post-exercise (VR-based and TRAD exercise) changes in PFC O2Hb during the Stroop test.

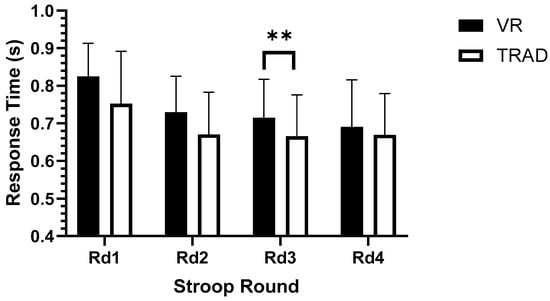

3.4. Stroop Test

Figure 3 shows the post-exercise scores for response times in the Stroop test. Rounds 1, 2, and 4 showed no significant difference in response time between the VR-based and TRAD exercise trials. Round 3 saw a significantly quicker response time in the TRAD exercise trial compared to VR-based exercise trial (TRAD: 0.67 ± 0.11 s, VR: 0.72 ± 0.1 s, p = 0.038, n2p = 0.364). There were no significant differences in Stroop accuracy between the two trials.

Figure 3.

Post-exercise (VR-based & TRAD exercise) scores for response times in the Stroop test. ** p < 0.01.

4. Discussion

The study found no significant difference in PFC oxygenation, average HR, and BLa− between the VR-based and TRAD exercise trials. These findings are important because the consistency in PFC oxygenation, HR, and BLa− shows VR-based exercise may be an appropriate exercise option to achieve moderate-intensity exercise. This could potentially eliminate barriers to exercise for overweight or obese individuals and allow them an alternative mode of exercise at home, rather than relying on gym-based activities. This access to in-home exercise could improve both physical and cognitive function. The Stroop test found no significant difference in response time between the VR-based and TRAD exercise trials in rounds 1, 2, and 4; however, the response times following the TRAD exercise trials in round 3 were faster than the VR-based exercise times. Perhaps the engaging and interactive nature of VR increases mental strain, making the exercise bout more mentally exhausting than TRAD exercise. The ability to sustain moderate-intensity exercise in addition to VR commands may lead to cognitive overload, which may be a key factor in the reduced cognitive performance seen in round 3 following the VR-based exercise trial.

As previously mentioned, over 50% of Americans over 18 do not achieve the 150 min of moderate-intensity exercise each week recommended by the CDC [6]. According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), 76% of adults in the U.S. play video games on at least one platform [24]. This lack of physical activity and high level of engagement in video games presents the potential for exergaming to be an effective alternative form of exercise for many. A previous study found that exergaming for 60 min three times a week for 12–24 weeks decreased adiposity and increased cardiometabolic health in adolescents [25]. It is plausible to suggest that these physiological benefits may extend to VR-based exercise, which combines physical exertion with heightened cognitive and sensory engagement. Although our study did not examine adipose tissue or cardiovascular health in response to exergaming, the participants were able to achieve moderate-intensity exercise during the VR condition. This finding suggests that, if performed chronically, VR-based exercise may confer similar cardiometabolic benefits while simultaneously offering enhanced engagement and adherence compared to traditional exercise modalities.

Although the field of exergaming is relatively novel, a few studies have demonstrated its ability to improve cognitive function. Their findings show that 3 min of upper body exergaming can increase activation of the DLPFC [26]. Previous research also suggests that 10 min of VR-based exercise can improve working memory performance, as demonstrated in the 3-back test [27]. Our findings agree with this research, since there was no significant difference in cognitive performance on the Stroop test between TRAD and VR-based exercise in rounds 1, 2, and 4, indicating VR exercise’s ability to promote cognitive function. However, the Stroop response times following the TRAD exercise were slightly faster than the VR-based exercise response time in round 3. The isolated difference observed in round 3, may reflect normal variability in cognitive performance following acute exercise in a small pilot sample. On the other hand, this could also be due to higher engagement and cognitive stimulation during the VR-based workout, leading to more cognitive fatigue during the cognitive task following the VR-based trial. The TRAD exercise trial did not include an interactive component; therefore, there was minimal cognitive engagement during the exercise, which may have allowed for faster TRAD exercise trial response times in round 3.

Previous studies found that exergaming can improve executive function in the same way traditional treadmill exercise does [28]. This study’s findings were measured with the Stroop test, and the participants in the exergaming group and the treadmill group had faster response times after their exercise than they did before. These results match our findings from rounds 1, 2, and 4 of the Stroop test where there was no significant difference between VR-based and TRAD exercise response times. Similarly, Guzmán and colleagues [29] found that aerobic exercise and aerobic exercise combined with video games had positive effects on decision reaction times. The control group in this study, who were at rest, had no improvements in choice reaction times [29]. Another study found that moderate and high-intensity VR exergaming leads to cognitive improvements, with the improvements being more pronounced following high-intensity exergaming [30]. This offers evidence that exergaming is also a viable option for exercise which can improve cognitive function.

In addition to measuring cognitive function with the Stroop test following VR-based and TRAD exercise, fNIRS was used to examine PFC activation. fNIRS can measure resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC), which is how different areas of the brain are functionally connected when the brain is not performing a task. A previous study found that rsFC was significantly higher following exergaming than TRAD exercise or no exercise at all [31]. In addition to exergaming increasing the brain’s functional connectivity, studies have shown that VR-based cognitive training is associated with an increase in frontal-occipital functional connectivity in patients with mild cognitive impairment [32]. Since exergaming and VR-based cognitive training elicit more functional connectivity in the brain than TRAD exercise, shown through fNIRS, this provides evidence for VR as an effective alternative exercise form to improve cognitive function in overweight or obese individuals.

From a theoretical perspective, VR-based exercise may impose a greater dual-task cognitive load, influencing neural efficiency and post-exercise cognitive performance. Practically, VR-based exercise represents an accessible and engaging alternative to TRAD exercise that may improve exercise adherence in populations that struggle to meet physical activity guidelines.

It is important to note several limitations of this pilot study, the first being a small sample size and lack of counterbalancing, as each participant completed the VR-based exercise trial first and the TRAD exercise trial second. Secondly, since the target population was overweight/obese individuals within a certain age range, the results produced may not apply to individuals who are considered healthy or who fall outside the specified age range. Lastly, the fNIRS measurement only observed activity in the PFC. Looking at other areas of the brain, such as the hippocampus, may provide additional insight and information regarding cognitive function post-exercise. Findings should therefore be interpreted as preliminary and hypothesis-generating.

Future research should strive to determine if overweight or obese individuals would rate VR-based exercise as “enjoyable” and investigate long-term adherence to a VR-based exercise protocol. Recent research has measured participant “satisfaction” following VR-based immersive exercise and found that those engaging in TRAD exercise with VR technology had reported higher satisfaction after the program than participants completing TRAD exercise without VR [33]. Other research suggests that using VR during stationary exercise, such as cycling or a wall squat, reduces pain intensity and lowers perceived exertion scores compared to those performing a wall squat without VR [34]. These findings could offer insight into a new exercise option for individuals who are not physically active. Another future direction from this study could be to extend the duration of the study to include multiple VR-based and TRAD exercise sessions. This could examine if the cognitive load required to complete VR exercise would decrease as participants gained familiarity with the movements, leading to increased cognitive performance on the Stroop test following both VR-based and TRAD exercise trials.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this pilot study suggests that VR-based exercise is a feasible alternative to TRAD exercise for achieving moderate-intensity exercise in overweight/obese individuals, with broadly comparable post-exercise cognitive responses. Given the small sample size, conclusions regarding efficacy are premature, and larger randomized studies are needed. These preliminary findings are important because they may offer a new option to help overweight and obese individuals engage in physical activity in an environment that is comfortable for them. Engaging in VR-based exercise could help individuals in this population meet the weekly moderate-intensity exercise recommendations and improve cognitive functioning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.M. and E.K.; methodology, T.M.; formal analysis, T.M. and E.K.; data curation, E.K., G.N., G.B., and D.W.; writing—original draft preparation, T.M. and E.K.; writing—review and editing, T.M., E.K., G.N., G.B., and D.W.; supervision, T.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of Northern Iowa (protocol code FY24-182 and 28 March 2024) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The group data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The individual data are not publicly available due to privacy and confidentiality.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACSM | American College of Sports Medicine |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| BLa− | Blood Lactate |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| DLPFC | Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex |

| fNIRS | Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy |

| HR | Heart Rate |

| LPFC | Left Prefrontal Cortex |

| PFC | Prefrontal Cortex |

| RPE | Rating of Perceived Exertion |

| RPFC | Right Prefrontal Cortex |

| TRAD | Traditional Exercise |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

References

- CDC. FastStats—Overweight Prevalence. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/obesity-overweight.htm (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Rukadikar, C.; Shah, C.J.; Raju, A.; Popat, S.; Josekutty, R. The Influence of Obesity on Cognitive Functioning Among Healthcare Professionals: A Comprehensive Analysis. Cureus 2023, 15, e42926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medic, N.; Ziauddeen, H.; Ersche, K.D.; Farooqi, I.S.; Bullmore, E.T.; Nathan, P.J.; Ronan, L.; Fletcher, P.C. Increased body mass index is associated with specific regional alterations in brain structure. Int. J. Obes. 2016, 40, 1177–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, M.J.; Tesar, A.K.; Beier, J.; Berg, M.; Warrings, B. Grey matter alterations in obesity: A meta-analysis of whole-brain studies. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, C.J.; Reichelt, A.C.; Hall, P.A. The Prefrontal Cortex and Obesity: A Health Neuroscience Perspective. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2019, 23, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargénius, H.L.; Lydersen, S.; Hestad, K. Neuropsychological function in individuals with morbid obesity: A cross-sectional study. BMC Obes. 2017, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohle, S.; Diel, K.; Hofmann, W. Executive functions and the self-regulation of eating behavior: A review. Appetite 2018, 124, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgaddal, N.; Kramarow, E.; Reuben, C. Physical Activity Among Adults Aged 18 and Over: United States, 2020. (NCHS Data Brief No. 443). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db443.htm (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- CDC. Overcoming Barriers to Physical Activity. Physical Activity Basics. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/physical-activity-basics/overcoming-barriers/index.html (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Kleinloog, J.P.D.; Mensink, R.P.; Ivanov, D.; Adam, J.J.; Uludağ, K.; Joris, P.J. Aerobic Exercise Training Improves Cerebral Blood Flow and Executive Function: A Randomized, Controlled Cross-Over Trial in Sedentary Older Men. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, X.; Bray, S.; Bryant, D.M.; Glover, G.H.; Reiss, A.L. A quantitative comparison of NIRS and fMRI across multiple cognitive tasks. NeuroImage 2011, 54, 2808–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Causse, M.; Chua, Z.; Peysakhovich, V.; Del Campo, N.; Matton, N. Mental workload and neural efficiency quantified in the prefrontal cortex using fNIRS. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujach, S.; Byun, K.; Hyodo, K.; Suwabe, K.; Fukuie, T.; Laskowski, R.; Dan, I.; Soya, H. A transferable high-intensity intermittent exercise improves executive performance in association with dorsolateral prefrontal activation in young adults. NeuroImage 2018, 169, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Han, R.; Li, Z.; Huang, X.; Cheng, D.; Ni, J.; Zhang, S.; Tan, X.; Kang, P.; Yu, S.; et al. Effect of virtual reality-based exercise and physical exercise on adolescents with overweight and obesity: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e075332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.; Ekkekakis, P. Affect and prefrontal hemodynamics during exercise under immersive audiovisual stimulation: Improving the experience of exercise for overweight adults. J. Sport Health Sci. 2019, 8, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, E.Y.; Kim, Y.S.; Lee, Y.J.; Hur, M.H. Virtual Reality Exercise Program Effects on Body Mass Index, Depression, Exercise Fun and Exercise Immersion in Overweight Middle-Aged Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosprêtre, S.; Marcel-Millet, P.; Eon, P.; Wollesen, B. How Exergaming with Virtual Reality Enhances Specific Cognitive and Visuo-Motor Abilities: An Explorative Study. Cogn. Sci. 2023, 47, e13278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liguori, G.; American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod, C.M. Half a century of research on the Stroop effect: An integrative review. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 109, 163–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa, H.; Dan, I.; Tsuzuki, D.; Kato, M.; Okamoto, M.; Kyutoku, Y.; Soya, H. Acute moderate exercise elicits increased dorsolateral prefrontal activation and improves cognitive performance with Stroop test. Neuroimage 2010, 50, 1702–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crush, E.A.; Loprinzi, P.D. Dose-response effects of exercise duration and recovery on cognitive functioning. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2017, 124, 1164–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.K.; Chu, C.H.; Wang, C.C.; Wang, Y.C.; Song, T.F.; Tsai, C.L.; Etnier, J.L. Dose–response relation between exercise duration and cognition. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2015, 47, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriarty, T.; Bourbeau, K.; Bellovary, B.; Zuhl, M.N. Exercise Intensity Influences Prefrontal Cortex Oxygenation During Cognitive Testing. Behav. Sci. 2019, 9, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoggins, H.; Porter, R.R.; Braun-Trocchio, R. Gameplay and physical activity behaviors in adult video game players. Front. Sports Act. Living 2025, 6, 1520202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staiano, A.E.; Marker, A.M.; Beyl, R.A.; Hsia, D.S.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Newton, R.L. A randomized controlled trial of dance exergaming for exercise training in overweight and obese adolescent girls. Pediatr. Obes. 2016, 12, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; You, T.; Du, R.; Zhang, J.-H.; Peng, T.; Liang, J.; Zhao, B.; Ou, H.; Jiang, Y.; Feng, H.-P.; et al. The Effect of Non-immersive Virtual Reality Exergames Versus Band Stretching on Cardiovascular and Cerebral Hemodynamic Response: A Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Study. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 902757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochi, G.; Ohno, K.; Kuwamizu, R.; Yamashiro, K.; Fujimoto, T.; Ikarashi, K.; Kodama, N.; Onishi, H.; Sato, D. Exercising with virtual reality is potentially better for the working memory and positive mood than cycling alone. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2024, 27, 100641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Jo, E.-A.; Ji, H.; Kim, K.-H.; Park, J.-J.; Kim, B.H.; Cho, K.I. Exergaming Improves Executive Functions in Patients with Metabolic Syndrome: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Serious Games 2019, 7, e13575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, J.F.; López-García, J. Acute effects of exercise and active video games on adults’ reaction time and perceived exertion. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2016, 16, 1197–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Mao, J.; Sun, J.; Teo, W.-P. Exercise intensity of virtual reality exergaming modulates the responses to executive function and affective response in sedentary young adults: A randomized, controlled crossover feasibility study. Physiol. Behav. 2024, 288, 114719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eng, C.M.; Pocsai, M.; Fishburn, F.; Calkosz, D.; Fisher, A.V. Adaptations of Executive Function and Prefrontal Cortex Connectivity Following Exergame Play in 4-to 5-year old Children. In Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society, Online, 29 July–1 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.M.; Kim, N.; Lee, S.Y.; Woo, S.K.; Park, G.; Yeon, B.K.; Park, J.W.; Youn, J.-H.; Ryu, S.-H.; Lee, J.-Y.; et al. Effect of Cognitive Training in Fully Immersive Virtual Reality on Visuospatial Function and Frontal-Occipital Functional Connectivity in Predementia: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e24526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.M.; Mohamed Awad Allah, S.A.; Elsharawy, D.E.; Ahmed, H.S.; Abdelwahab, M.A.M. Effects of Conventional versus Virtual Reality-simulated Treadmill Exercise on Fatigue, Cognitive Function, and Participant Satisfaction in Post-COVID-19 Subjects. A Randomized Trial. J. Exerc. Sci. Fit. 2024, 22, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolu, U.; Camliguney, A.F. The Effect of Virtual Reality on Isometric Muscle Strength. Prog. Nutr. 2022, 24, 2022004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.