Preliminary Latvian RESTQ-76 for Athletes: A Tool for Recovery–Stress Monitoring and Health Promotion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. The Instrument

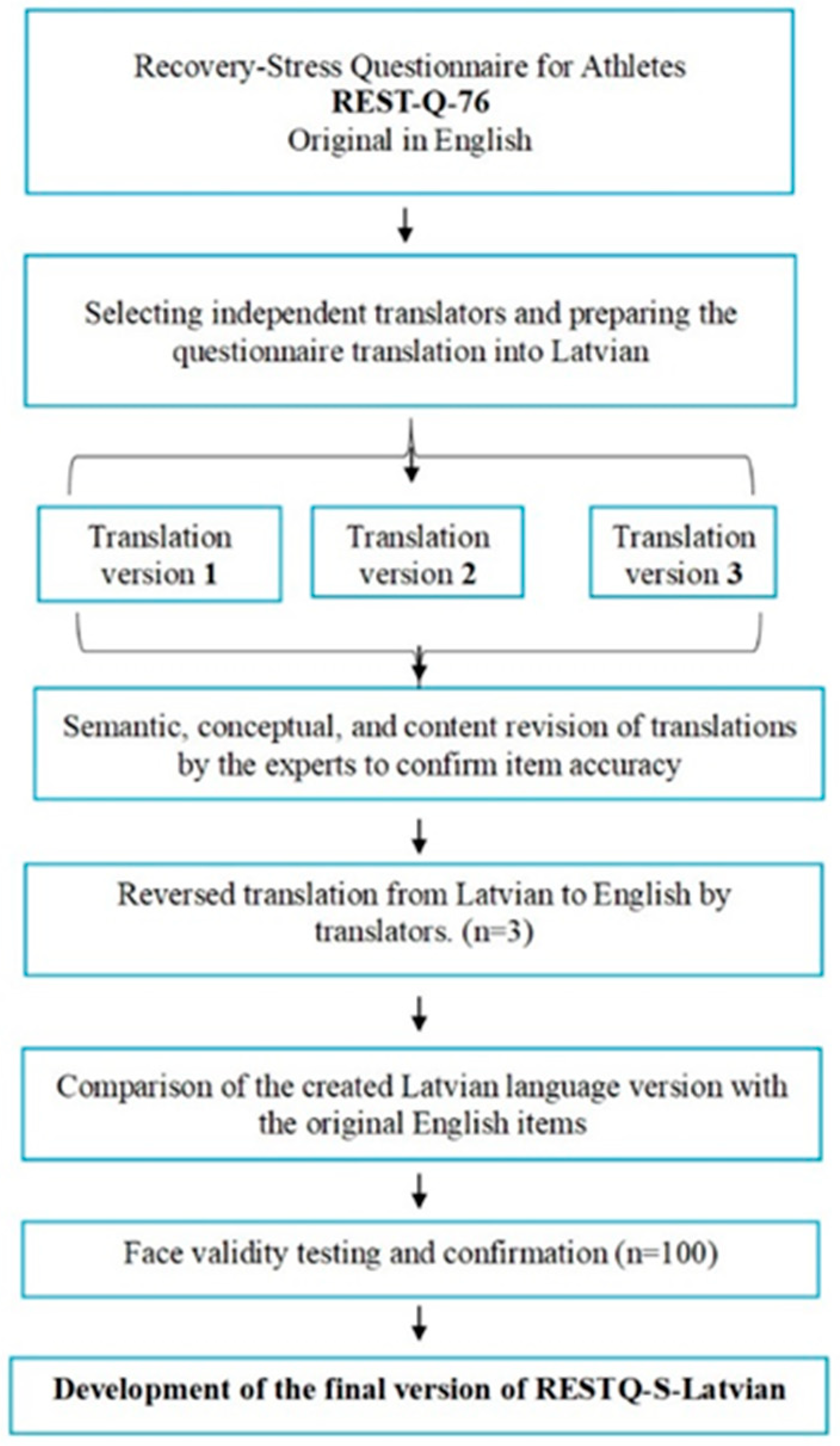

2.3. Translation and Cross-Cultural Adaptation Process of REST Q-76

2.4. Data Collection Procedures and Ethical Considerations

2.5. Statistical Procedures

3. Results

3.1. Distribution of the RESTQ Scales

3.2. Factor Analysis and Structural Model

3.3. Reliability Analysis

4. Discussion

Limitations and Practical Applications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RESTQ | Recovery stress questionnaire |

| GS | General stress |

| ES | Emotional stress |

| SS | Social stress |

| C/P | Conflicts/pressure |

| F | Fatigue |

| LE | Lack of energy |

| PC | Physical complaints |

| GR | General recovery |

| S | Success |

| SR | Social recovery |

| PR | Physical recovery |

| GWB | General well-being |

| SQ | Sleep quality |

| SS | Sport stress |

| DB | Disturbed breaks |

| EE | Emotional exhaustion |

| I | Injury |

| SSR | Sport-specific recovery |

| BS | Being in shape |

| PA | Personal accomplishment |

| SE | Self-efficacy |

| Self-R | Self-regulation |

References

- Kellmann, M.; Bertollo, M.; Bosquet, L.; Brink, M.; Coutts, A.J.; Duffield, R.; Erlacher, D.; Halson, S.L.; Hecksteden, A.; Heidari, J.; et al. Recovery and performance in sport: Consensus statement. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2018, 13, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbe, A.M.; Rasmussen, C.P.; Nielsen, G.; Nordsborg, N.B. High-intensity and reduced-volume training attenuates stress and recovery levels in elite swimmers. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2016, 16, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, J.A.; Moreira, A.; Crewther, B.T.; Nosaka, K.; Viveiros, L.; Aoki, M.S. Monitoring training load, recovery-stress state, immune-endocrine responses, and physical performance in elite female basketball players during a periodized training program. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2014, 28, 2973–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellmann, M. Preventing overtraining in athletes in high-intensity sports and stress/recovery monitoring. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2010, 20, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, J.; Beckmann, J.; Bertollo, M.; Brink, M.; Kallus, K.W.; Robazza, C.; Kellmann, M. Multidimensional monitoring of recovery status and implications for performance. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2019, 14, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lope Fernández, D.E.; Solís Briceño, O.B. Estrategias de afrontamiento como intervención al estrés en futbolistas (Coping strategies as a stress intervention in soccer players). Retos 2020, 38, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenttä, G.; Hassmén, P.; Raglin, S.J. Mood state monitoring of training and recovery in elite kayakers. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2006, 6, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hug, M.; Mullis, P.E.; Vogt, M.; Ventura, N.; Hoppeler, H. Training modalities: Over-reaching and over-training in athletes, including a study of the role of hormones. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 17, 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soligard, T.; Schwellnus, M.; Alonso, J.M.; Bahr, R.; Clarsen, B.; Dijkstra, H.P.; Gabbett, T.; Gleeson, M.; Hägglund, M.; Hutchinson, M.R.; et al. How much is too much? (Part 1) International Olympic Committee consensus statement on load in sport and risk of injury. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 1030–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwellnus, M.; Soligard, T.; Alonso, J.M.; Bahr, R.; Clarsen, B.; Dijkstra, H.P.; Gabbett, T.J.; Gleeson, M.; Hägglund, M.; Hutchinson, M.R.; et al. How much is too much? (Part 2) International Olympic Committee consensus statement on load in sport and risk of illness. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 1043–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdon, P.C.; Cardinale, M.; Murray, A.; Gastin, P.; Kellmann, M.; Varley, M.C.; Gabbett, T.J.; Coutts, A.J.; Burgess, D.J.; Gregson, W.; et al. Monitoring athlete training loads: Consensus statement. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2017, 12, S2161–S2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saw, A.E.; Kellmann, M.; Main, L.C.; Gastin, P.B. Athlete self-report measures in research and practice: Considerations for the discerning reader and fastidious practitioner. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2017, 12, S2127–S2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellmann, M.; Kallus, K.W. The Recovery-Stress Questionnaire for Athletes User Manual; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kellmann, M.; Kallus, K. (Eds.) The Recovery-Stress Questionnaire for Athletes. In The Recovery-Stress Questionnaire: User Manual; Pearson Assessment & Information GmbH: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2016; pp. 86–131. [Google Scholar]

- Kellmann, M.; Kallus, K.W. (Eds.) The Recovery-Stress Questionnaire: A User’s Manual; Routledge Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kölling, S.; Wiewelhove, T.; Raeder, C.; Endler, S.; Ferrauti, A.; Meyer, T.; Kellmann, M. Sleep monitoring of a six-day microcycle in strength and high-intensity training. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2016, 16, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, M.; Vacher, P.; Martinent, G.; Mourot, L. Monitoring stress and recovery states: Structural and external stages of the short version of the RESTQ sport in elite swimmers before championships. J. Sport Health Sci. 2019, 8, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfagno, D.G.; Hendrix, J.C. Overtraining syndrome in the athlete: Current clinical practice. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2014, 13, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nederhof, E.; Brink, M.S.; Lemmink, K.A. Reliability and validity of the Dutch Recovery Stress Questionnaire for Athletes. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 2008, 39, 301–311. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Does, H.T.; Brink, M.S.; Otter, R.T.; Visscher, C.; Lemmink, K.A. Injury risk is increased by changes in perceived recovery of team sport players. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2017, 27, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filho, E.; di Fronso, S.; Forzini, F.; Murgia, M.; Agostini, T.; Bortoli, L.; Robazza, C.; Bertollo, M. Athletic performance and recovery-stress factors in cycling: An ever-changing balance. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2015, 15, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellmann, M.; Kallus, K.W. Der Erholungs-Belastungs-Fragebogen für Sportler: Manual; Swets Test Services: Frankfurt, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Elbe, A.M. The Danish Version of the Recovery-Stress Questionnaire for Athletes; University of Copenhagen: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2008; unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, L.O.P.; Samulski, D.M. Validation process of the recovery-stress questionnaire for athletes (RESTQ-Sport) in Portuguese. R. Bras. Ci. Mov. 2005, 13, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- González-Boto, R.; Salguero, A.; Tuero, C.; Márquez, S.; Kellmann, M. Spanish adaptation and analysis by structural equation modeling of an instrument for monitoring overtraining: The Recovery-Stress Questionnaire (RESTQ-Sport). Soc. Behav. Personal. 2008, 36, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynoso-Sánchez, L.F.; Pérez-Verduzco, G.; Celestino-Sánchez, M.Á.; López-Walle, J.M.; Zamarripa, J.; Rangel-Colmenero, B.R.; Muñoz-Helú, H.; Hernández-Cruz, G. Competitive recovery-stress and mood states in Mexican youth athletes. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 627828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäestu, J.; Jürimäe, J.; Kreegipuu, K.; Jürimäe, T. Changes in perceived stress and recovery during heavy training in highly trained male rowers. Sport Psychol. 2006, 20, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinent, G.; Decret, J.C.; Isoard-Gautheur, S.; Filaire, E.; Ferrand, C. Evaluations of the psychometric properties of the Recovery-Stress Questionnaire for Athletes among a sample of young French table tennis players. Psychol. Rep. 2014, 114, 326–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovbas, Y.Y. Russian version of the RESTQ-sport questionnaire (Kellman, Kallus, 2001) for assessing the recovery status of athletes. Lech. Fizkul’tura I Sport. Meditsina 2015, 2, 15–21. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Morales, J.; Roman, V.; Yáñez, A.; Solana-Tramunt, M.; Álamo, J.; Fíguls, A. Physiological and psychological changes at the end of the soccer season in elite female athletes. J. Hum. Kinet. 2019, 66, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, D.; Clark, T.; Kellmann, M.; Hume, P. Stress and recovery changes of injured and non-injured amateur representative rugby league players over a competition season. N. Z. J. Sports Med. 2017, 43, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laux, P.; Krumm, B.; Diers, M.; Flor, H. Recovery–stress balance and injury risk in professional football players: A prospective study. J. Sports Sci. 2015, 33, 2140–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hacker, S.; Reichel, T.; Hecksteden, A.; Weyh, C.; Gebhardt, K.; Pfeiffer, M.; Ferrauti, A.; Kellmann, M.; Meyer, T.; Krüger, K. Recovery-stress response of blood-based biomarkers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres-Diego, B.; Alcaraz, P.E.; Marín-Pagán, C. Neuromuscular and psychological performance monitoring during one season in Spanish Marine Corps. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holguín-Ramírez, J.; Ramos-Jiménez, A.; Quezada-Chacón, J.T.; Cervantes-Borunda, M.S.; Hernández-Torres, R.P. Effect of mindfulness on the stress–recovery balance in professional soccer players during the competitive season. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, A.B.; Nakamura, F.Y.; Morgado, M.C.; Holmes, C.J.; Di Baldassarre, A.; Esco, M.R.; Rama, L.M. Heart rate variability and stress recovery responses during a training camp in elite young canoe sprint athletes. Sports 2019, 7, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, R.; Madigan, S.M.; Nevill, A.; Warrington, G.; Ellis, J.G. The sleep and recovery practices of athletes. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellmann, M. Enhancing Recovery: Preventing Underperformance in Athletes; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Boobani, B.; Grants, J.; Glaskova-Kuzmina, T.; Zidens, J.; Litwiniuk, A. Effect of green exercise on stress level, mental toughness, and performance of taekwondo athletes. Arch. Budo J. Innov. Agonol. 2024, 20, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Boobani, B.; Grants, J.; Litwiniuk, A.; Boge, I.; Glaskova-Kuzmina, T. Effect of walking in nature on stress levels and performance of taekwondo athletes in the competition period. J. Kinesiol. Exerc. Sci. 2024, 34, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volgemute, K.; Ulme, G.; Perepjolkina, V.; Licis, R.; Abele, A.; Lavins, R.; Klonova, A.; Tihija, A.; Grants, E. Adaptation and psychometric properties of Psychological Skills Inventory for Sport (PSIS-R5) in Latvian athletes: Insights and implications for practice. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0325225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boobani, B.; Kalnina, Z.; Glaskova-Kuzmina, T.; Erina, L.; Liepina, I. Utilizing facial emotion analysis with FaceReader to evaluate the effects of outdoor activities on preschoolers’ basic emotions: A pilot study in e-health. Int. J. Online Biomed. Eng. 2025, 21, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellmann, M.; Weidig, T. Der Pausenverhaltensfragebogen (PVF)—Manual [The Rest-Period Questionnaire—Manual]; Sportverlag Strauß: Cologne, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Montull, L.; Slapšinskaitė-Dackevičienė, A.; Kiely, J.; Hristovski, R.; Balagué, N. Integrative proposals of sports monitoring: Subjective outperforms objective monitoring. Sports Med. Open 2022, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.L.; Chapman, D.; Cronin, J.; Newton, M.; Gill, N. Fatigue monitoring in high performance sport: A survey of current trends. J. Aust. Strength Cond. 2012, 20, 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gudmundson, E. Guidelines for translating and adapting psychological instruments. Nord. Psychol. 2009, 61, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R.J. Vers une méthodologie de validation trans-culturelle de questionnaires psychologiques: Implications pour la recherche en langue française. Can. Psychol. 1989, 30, 662–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Test Commission. Guidelines for Translating and Adapting Tests, 2nd ed.; Version 2.4; 2018; Available online: www.InTestCom.org (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Kim, H.Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2013, 38, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods Psychol. Res. Online 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausenblas, H.A.; Nigg, C.R.; Downs, D.S.; Fleming, D.S.; Connaughton, D.P. Perceptions of exercise stages, barrier self-efficacy, and decisional balance for middle-level school students. J. Early Adolesc. 2002, 22, 436–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.J.; Nelson, J.K. Research Methods in Physical Activity; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Collier, J. Applied Structural Equation Modeling Using AMOS: Basic to Advanced Techniques; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kueh, Y.C.; Atamamen, T.; Arifin, W.N.; Abdullah, N.; Kuan, G. Validation of the Malay version of the recovery-stress questionnaire for athletes: Application of confirmatory factor analysis and exploratory structural equation modeling. Asian J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2024, 4, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, N.D.; Van Yperen, N.W.; Brauers, J.J.; Frencken, W.; Brink, M.S.; Lemmink, K.A.P.M.; Meerhoff, L.A.; Den Hartigh, R.J.R. Nonergodicity in load and recovery: Group results do not generalize to individuals. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2022, 17, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birrer, D.; Binggeli, A.; Seiler, R. Examination of the Factor Structure of the Recovery-Stress Questionnaire; Swiss Federal Institute of Sports Magglingen, Federal Office of Sport: Magglingen, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, H.; Orzeck, T.; Keelan, P. Psychometric item evaluations of the recovery-stress questionnaires for athletes. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2007, 8, 917–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnacinski, S.L.; Meyer, B.B.; Wahl, C.A. Psychometric properties of the RESTQ-Sport-36 in a collegiate student-athlete population. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 671919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hockey, G.R.J. The Psychology of Fatigue: Work, Effort and Control; University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Batista, J.M.; Coenders, G. Structural Equation Modeling: Models for the Analysis of Causal Relationships; La Muralla & Hespérides: Madrid, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Boobani, B.; Grants, J.; Vazne, Ž.; Volgemute, K.; Astafičevs, A.; Leja, R.; Brūvere, D.D.; Līcis, R.; Saulīte, S.; Litwiniuk, A. Recovery-Stress Questionnaire-76 (RESTQ-76) for Latvian Athletes; Rīga Stradiņš University Institutional Repository Dataverse: Rīga, Latvia, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Cruz, G.; López-Walle, J.; Quezada-Chacón, J.T.; Jaenes, J.C.; Rangel Colmenero, B.; Reynoso-Sánchez, L.F. Impact of the internal training load over recovery-stress balance in endurance runners. Rev. Psicol. Deporte 2017, 26, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, T.J.; Baguley, T.; Brunsden, V. From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. Br. J. Psychol. 2014, 105, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haff, G.G.; Haff, E.E. Training integration and periodization. In Strength and Conditioning Program Design; Hoffman, J., Ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2012; pp. 209–254. [Google Scholar]

| Scales | M | SD | S | K | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-GS | 7.54 | 4.83 | 0.66 | 0.05 | 0.81 |

| 2-ES | 8.15 | 4.14 | 0.38 | 0.08 | 0.79 |

| 3-SS | 8.05 | 4.52 | 0.53 | 0.06 | 0.80 |

| 4-C/P | 10.25 | 4.42 | 0.38 | −0.19 | 0.70 |

| 5-F | 10.32 | 4.68 | 0.47 | −0.25 | 0.75 |

| 6-LE | 8.65 | 4.20 | 0.50 | 0.31 | 0.74 |

| 7-PC | 7.71 | 4.23 | 0.67 | 0.12 | 0.73 |

| 8-S | 12.46 | 4.11 | 0.26 | −0.07 | 0.70 |

| 9-SR | 12.70 | 4.70 | 0.21 | −0.51 | 0.74 |

| 10-PR | 11.24 | 3.90 | 0.32 | −0.03 | 0.72 |

| 11-GWB | 12.32 | 4.15 | 0.18 | −0.36 | 0.78 |

| 12-SQ | 10.97 | 4.96 | 0.21 | −0.40 | 0.70 |

| 13-DB | 7.16 | 4.33 | 0.37 | −0.47 | 0.75 |

| 14-EE | 6.15 | 4.41 | 0.62 | −0.009 | 0.73 |

| 15-I | 9.84 | 4.59 | 0.43 | −0.03 | 0.70 |

| 16-BS | 12.82 | 4.68 | 0.06 | −0.27 | 0.81 |

| 17-PA | 11.24 | 4.57 | 0.41 | 0.12 | 0.70 |

| 18-SE | 12.10 | 4.66 | 0.19 | 0.06 | 0.82 |

| 19-Self-R | 12.74 | 4.68 | 0.03 | −0.21 | 0.72 |

| Higher-Order Factor | Abbreviation | Subscales Included | Number of Subscales | Items per Subscale | Total Items |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Stress | GS | General Stress (GS); Emotional Stress (ES); Social Stress (SS); Conflicts/Pressure (C/P); Fatigue (F); Lack of Energy (LE); Physical Complaints (PC) | 7 | 4 | 28 |

| General Recovery | GR | Success (S); Social Recovery (SR); Physical Recovery (PR); General Well-Being (GWB) | 4 | 4 | 16 |

| Sport-Specific Stress | SS | Disturbed Breaks (DB); Emotional Exhaustion (EE); Injury (I) | 3 | 4 | 12 |

| Sport-Specific Recovery | SSR | Being in Shape (BS); Personal Accomplishment (PA); Self-Efficacy (SE); Self-Regulation (Self-R) | 4 | 4 | 16 |

| Absolute Fit | Incremental Fit | Parsimonious Fit | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Modification | RMSEA | GFI | AGFI | TLI | CFI | NFI | χ2/df |

| M1 | Initial model | 0.099 | 0.850 | 0.801 | 0.871 | 0.891 | 0.867 | 4.85 |

| M2 | M1 + correlated errors of Emotional Stress and Social Stress | 0.09 | 0.868 | 0.824 | 0.893 | 0.910 | 0.886 | 4.20 |

| M3 | M2 + correlated errors of Fatigue and Physical Complaints | 0.089 | 0.872 | 0.827 | 0.896 | 0.914 | 0.889 | 4.11 |

| Criterion for goodness of fit | ≤0.08 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.85 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 | <5 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Boobani, B.; Grants, J.; Vazne, Ž.; Volgemute, K.; Astafičevs, A.; Leja, R.; Brūvere, D.D.; Licis, R.; Saulite, S.; Litwiniuk, A. Preliminary Latvian RESTQ-76 for Athletes: A Tool for Recovery–Stress Monitoring and Health Promotion. Sci 2026, 8, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci8010006

Boobani B, Grants J, Vazne Ž, Volgemute K, Astafičevs A, Leja R, Brūvere DD, Licis R, Saulite S, Litwiniuk A. Preliminary Latvian RESTQ-76 for Athletes: A Tool for Recovery–Stress Monitoring and Health Promotion. Sci. 2026; 8(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci8010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoobani, Behnam, Juris Grants, Žermēna Vazne, Katrina Volgemute, Aleksandrs Astafičevs, Rihards Leja, Daido Dagne Brūvere, Renars Licis, Sergejs Saulite, and Artur Litwiniuk. 2026. "Preliminary Latvian RESTQ-76 for Athletes: A Tool for Recovery–Stress Monitoring and Health Promotion" Sci 8, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci8010006

APA StyleBoobani, B., Grants, J., Vazne, Ž., Volgemute, K., Astafičevs, A., Leja, R., Brūvere, D. D., Licis, R., Saulite, S., & Litwiniuk, A. (2026). Preliminary Latvian RESTQ-76 for Athletes: A Tool for Recovery–Stress Monitoring and Health Promotion. Sci, 8(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci8010006