Abstract

Chitosan nanoparticles (CSNPs), a product of nanotechnology, have emerged as promising biostimulants with significant applications in sustainable agriculture for enhancing crop yield and quality. In this study, the effects of foliar-applied CSNPs on yield and bioactive compounds in melon (Cucumis melo L.) fruits were evaluated. Five increasing concentrations of CSNPs (0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 mg mL−1) were foliarly applied. The foliar spraying of CSNPs exerted positive effects on fruit productivity and nutraceutical attributes. The most significant yield and commercial quality were achieved with the 0.4 mg mL−1 dose. In contrast, the 0.8 mg mL−1 dose was most effective in enhancing optimal postharvest characteristics, including fruit firmness and reduced weight loss, as well as stimulating the accumulation of bioactive compounds (such as flavonoids and vitamin C) and antioxidant capacity. In the case of phenols, the highest total phenolic content was observed at concentrations of 0.6 and 0.8 mg mL−1. Therefore, the foliar application of CSNPs constitutes a versatile and sustainable strategy, allowing for the tailoring of application doses to either maximize yield or enhance the functional and postharvest quality of melon fruits.

1. Introduction

Agricultural intensification in recent decades has relied on the continuous use of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides [1]. Although these inputs have helped to sustain productivity, their prolonged use has been associated with alterations in soil biota and structure, contamination from runoff and leaching, selection of resistance in phytopathogens, and the presence of residues in agricultural products [2,3]. In addition, increasing climate variability (e.g., droughts and heatwaves), regulatory and market demands for stricter residue limits, and rising costs underscore the need to explore more sustainable production alternatives [4,5]. These challenges have accelerated the search for innovative and sustainable alternatives, such as plant biostimulants, to maintain productivity while minimizing environmental footprints.

Crop biostimulation, defined as the application of substances or microorganisms to enhance nutrient efficiency, abiotic stress tolerance, and/or crop quality traits [6], is an emerging strategy to enhance fruit yield and organoleptic quality [7,8]. This technology is based on the application of substances or microorganisms aimed at improving agronomic traits and increasing plant tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses [6,9]. Among the various materials used as biostimulants, chitosan nanoparticles (CSNPs) are particularly notable due to their unique properties, including biocompatibility, non-toxicity, biodegradability, and environmental friendliness [10]. These features are particularly relevant for their application in the agricultural sector.

The large specific surface area of CSNPs increases the density of protonated amino groups, enhancing their capacity for electrostatic and hydrogen bonding interactions. This property directly improves leaf adhesion and retention, leading to more uniform coverage [11,12]. Furthermore, they have a cross-linked polymer matrix architecture that acts as a nano-reservoir, allowing controlled release by diffusion and greater persistence over time, as well as greater effective surface reactivity, which enhances plant defense responses at lower doses [12,13,14].

Several studies have reported that CSNPs induce diverse physiological responses in plants, such as the activation of antioxidant enzymes [15,16,17] and mitigation of oxidative stress through the modulation of catalase, ascorbate peroxidase, and glutathione reductase activities [16], ultimately improving growth, productivity, and fruit quality [18].

In addition, CSNPs improve the plant’s immune response, increase the expression of PR proteins related to pathogenicity, and activate enzymes associated with cell wall reinforcement (e.g., chitinases, β-1,3-glucanases, and polyphenol oxidases), strengthening physical and chemical barriers [19,20,21]. They intensify phenylpropanoid metabolism and the accumulation of phenols and flavonoids [22,23].

Melon (Cucumis melo L.) is one of the most important horticultural crops worldwide, both in terms of cultivated area and commercial value, as well as for its nutritional attributes. Its pulp is a valuable source of health-promoting compounds, such as vitamin C, β-carotene, proteins, and lipids, and has a high water content, which provides hydration and antioxidant properties [24,25]. However, the concentration of bioactive compounds in melon is often relatively low compared to other fruits [26,27], and research on the use of nano-biostimulants like CSNPs to enhance its nutraceutical profile remains limited.

Consequently, we hypothesize that the foliar application of CSNP would improve the productivity and nutraceutical quality of melons in terms of higher fruit yield, total phenolics, flavonoids, vitamin C, and antioxidant capacity, and it would improve postharvest attributes (higher firmness and lower weight loss).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Growing Conditions and Plant Material

The experiment was conducted in Concordia, Coahuila, Mexico (25°48′31″ N, 103°5′56.4″ W; 1016 m.a.s.l.). The region has a dry semi-warm climate, characteristic of the Comarca Lagunera, with an average annual temperature of 22 °C (ranging from 16.1 to 38.5 °C) and mean annual rainfall of 258 mm. The melon hybrid ‘Cruiser’ (Harris Moran®) was sown directly into the soil on 15 March 2024, at 0.30 m within-row spacing and 2.0 m between-row spacing. The crop cycle lasted approximately 90 days from sowing to the last harvest. The soil had a silty loam texture, with a bulk density of 0.56 g cm−3, pH of 7.63, electrical conductivity of 3.28 dS m−1, organic matter of 0.8%, total nitrogen (N) of 4.82 mg kg−1, available phosphorus (P) of 4.27 mg kg−1, potassium (K) of 603.06 mg kg−1, calcium (Ca) of 6181.93 mg kg−1, and magnesium (Mg) of 202.74 mg kg−1. Fertilization consisted of 120–60–00 (N–P2O5–K2O), applying all P and half of the N at sowing, and the remaining N at flowering, using NH4H2PO4 and NH4SO4. Irrigation was applied by gravity, with 300 mm before sowing and 250 mm during the growing period, totaling 550 mm over the crop cycle. Agronomic management followed regional INIFAP (Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias) recommendations. Weed control was performed manually twice. Pest and disease control relied on constant monitoring and the preventive application of biological products when required. The first fruits were harvested 77 days after sowing, followed by three additional harvests.

2.2. Chitosan Nanoparticles

CSNPs were synthesized at CIQA (Saltillo, Mexico) by ionic gelation, following Kumaraswamy et al. [28] with minor adaptations. Chitosan (viscosimetric molecular weight ~200,000 g mol−1; degree of deacetylation 84%; Marine Hydrocolloids, Kerala, India) was dissolved at 0.5% (w/v) in 0.5% (v/v) acetic acid under magnetic stirring (~200 rpm) at room temperature until complete solubilization. In parallel, a sodium tripolyphosphate (TPP; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) solution was prepared at 0.5% (w/v) in deionized water. Ionic crosslinking was carried out at a 10:3 (v/v) chitosan: TPP solution ratio by adding the TPP solution dropwise to the chitosan solution under vigorous stirring (~600 rpm) and allowing the reaction to proceed for ~30 min at room temperature.

The resulting dispersion was centrifuged (12,000× g, 10 min, 4 °C) to pellet the nanoparticles; the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was washed three times with deionized water (resuspension + centrifugation) to remove unreacted species. For solid-state characterization (FTIR, TGA, and SEM), a clean aliquot was frozen and lyophilized (≈48 h). The dried nanoparticles were stored in airtight polypropylene vials with desiccant and protected from light at 4 °C to minimize hygroscopicity until use. The CSNPs (ionic gelation, CS: TPP 10:3 v/v) had a hydrodynamic size of 111 ± 21 nm (DLS). Their formation was corroborated by a UV–Vis band at 195 nm and by FTIR-ATR with characteristic signals (∼3164 cm−1, –OH/–NH vibrations; 1628 and 1532 cm−1, –CONH2 due to CS–TPP interaction). SEM confirmed their nanometric scale, and TGA showed that the CS–TPP network had a stable thermal behavior. Additional details are provided in Ramírez-Rodríguez et al. [29].

2.3. Treatments and Experimental Design

CSNP dispersions were prepared in deionized water containing glycerin (1% v/v) and Bionex® (0.2% v/v; Arysta LifeScience México, S.A. de C.V., Ciudad de México, Mexico) as dispersant/adjuvant agents. A CSNP stock at 1 mg mL−1 (mass of CSNP solids per mL of carrier) was obtained by sonication in an ultrasonic bath (Branson 1510R-DTH; Branson Ultrasonics Corp., Danbury, CT, USA; ~40 kHz, 6 min). Working spray solutions were prepared by diluting the stock with the same carrier to final CSNP concentrations of 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 mg mL−1; the 0 mg mL−1 treatment (control) contained only the carrier (deionized water + glycerin 1% v/v + Bionex® 0.2% v/v) and no CSNPs. Foliar applications were performed in the early morning (08:00 h) four times at 15-day intervals, beginning at the 3–4 true-leaf stage. Treatments were assigned in a completely randomized design (CRD) with six replicates (plots) per treatment. Each experimental plot consisted of a 4 m row with 13 plants (0.30 m between plants); the distance between rows was 2.0 m, so the plot area was ≈ 8 m2. Sprays were applied at the plot level with a backpack sprayer fitted with flat-fan nozzles. The actual spray volume per 4-m plot increased with canopy development and was 0.24, 0.50, 0.90, and 1.00 L for the 1st–4th applications, respectively.

2.4. Yield and Commercial Fruit Quality

Fruits were harvested in four pickings as they reached commercial maturity. The harvest started 77 days after sowing and continued with three additional pickings at regular intervals; all plots (treatments) were harvested on the same four dates to ensure comparability. At each picking and for each plot, the number of fruits and total fruit weight were recorded using a digital scale (Torrey®, Monterrey, Nuevo León, Mexico; 5 kg capacity). Yield per hectare (Mg ha−1) was computed as the sum of marketable fruit weight over the four pickings per plot, scaled by plot area.

2.5. Soluble Solids and Firmness

Total soluble solids (TSSs) were measured using a handheld refractometer (Atago® Ltd., Tokyo, Japan; Master 2311, 0–32% Brix), calibrated with distilled water (0 Brix) before each session. From each fruit, mesocarp pulp samples were taken from the equatorial region on two opposite sides, avoiding the placental tissue and seed cavity. Subsamples (10 g total) were homogenized (mortar/blender), and juice was obtained by pressing through double-layer gauze. Readings were taken on a clean, dry prism at 20 ± 1 °C. For each fruit, two technical readings were recorded and averaged. Results are expressed in Brix. Firmness was evaluated using a digital penetrometer (Extech® Instruments, Waltham, MA, USA; FH20000) equipped with an 8 mm cylindrical probe. Measurements were taken in the equatorial region on two opposite sides of the fruit; on each side, the skin/rind was carefully removed to expose the mesocarp, standardizing a circular area of 1.5–2.0 cm in diameter and a peeling thickness of ≈ 2–3 mm (only down to the mesocarp, without removing additional pulp). Two separate punctures were made on each side ≥2 cm apart and away from any previous defects (four punctures per fruit in total). The penetration depth was standardized to 8 mm, recording the maximum force (N); when necessary, a constant feed rate was maintained [30].

2.6. Fruit Weight Loss

To estimate fruit weight loss, a sample of four fruits per treatment was collected and exposed to laboratory conditions. Weight loss was measured seven days after harvest using a digital scale (Torrey®, Mexico) [31]. The difference was calculated with respect to the initial weight and recorded as a percentage, according to the following formula:

where WL: Weight Loss; IW: Initial weight; and FW: Final weight.

2.7. Preparation of Extracts for Non-Enzymatic Antioxidants

Six melons were randomly selected from each treatment for the analysis of non-enzymatic antioxidants. From each fruit, three independent subsamples (2 g each) were collected from different regions (apical, equatorial, and basal) to ensure sample representativeness and homogeneity. Each subsample was extracted with 10 mL of 80% ethanol in plastic tubes, which were sealed with screw caps and placed in a rotary shaker (Appropriate Technical Resources, Inc. (ATR Biotech), Laurel, MD, USA) for 6 h at 5 °C and 200 rpm. Samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min, and the supernatant was collected for analysis. All spectrophotometric determinations were performed in triplicate.

2.8. Total Flavonoid Content

The total flavonoids were determined by spectrophotometry [32]; 250 μL of the ethanolic extract was taken, mixed with 1.25 mL of Milli-Q water and 75 μL of NaNO2 (5%), left to stand for 5 min, and 150 μL of AlCl3 (10%) was added. Subsequently, 500 μL of NaOH (1 M) and 275 μL of Milli-Q water were added. It was vigorously shaken, and the samples were quantified in a UV–Vis spectrophotometer at 510 nm (Metash, UV-6000, Shanghai, China). The standard was prepared with quercetin dissolved in absolute ethanol (y = 0.0122x − 0.0067; r2 = 0.965). The results are expressed in mg QE 100 g−1 FW.

2.9. Total Phenolic Content

The total phenolic content was determined using a modified version of the Folin–Ciocalteau method, as described by Guillén-Enríquez et al. [33]. An aliquot (30 µL) of the ethanolic extract (Section 2.7) was combined with 270 μL of distilled water in a test tube. Subsequently, 1.5 mL of Folin–Ciocalteau reagent (Sigma-Aldrich), diluted at a ratio of 1:15, was added, and the mixture was agitated briefly using a vortex mixer for 10 s. After waiting for 5 min, 1.2 mL of sodium carbonate solution (7.5% w/v) was introduced into the test tube and vortexed for an additional 10 s. The resulting solution was then incubated in a water bath set to 45 °C for 15 min. Finally, the solution was allowed to cool to room temperature before further analysis. The absorbance of the solution was measured at 765 nm using a spectrophotometer (Metash, UV-6000, Shanghai, China). The phenolic content was assessed by employing a standard curve with gallic acid (from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) as the reference standard, and the outcomes were expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalent (GAE) per 100 g fresh weight (mg GAE 100 g−1 FW).

2.10. Antioxidant Capacity

The assessment of antioxidant capacity was conducted through the in vitro DPPH+ method, with a modification based on the method of Brand-Williams [34]. A 50 µL aliquot of the ethanolic extract (Section 2.7) was mixed with 950 µL of 0.1 mM DPPH+ in ethanol; after 3 min, absorbance was read at 515 nm. A calibration curve was prepared with Trolox (Sigma-Aldrich), and results were expressed as milligrams of Trolox equivalents per 100 g of fresh weight (mg TE 100 g−1 FW).

2.11. Vitamin C

The vitamin C content was determined by titration with 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol (DCPIP; AOAC 967.21) [35]. A sample mass W (g) was homogenized with an acid extractant (e.g., 2% v/v HCl or 3% m/v metaphosphoric acid) and measured to Vtotal (mL); the extract was kept protected from light and filtered. The DCPIP solution was standardized daily with L-ascorbic acid to obtain the dye factor F (mg AA·mL−1). An aliquot (mL) of the extract was titrated (Valiquot) until a persistent pale pink color change occurred (~10 s) to record the volume of dye consumed (VDCPIP) (mL). The results were expressed as mg of ascorbic acid per 100 g of fresh weight (mg AA 100 g−1 FW), calculated using:

where F is the dye factor (mg AA mL−1) obtained from daily standardization with L-ascorbic acid; VDCPIP is the volume of DCPIP consumed in the titration (mL); Vtotal is the total extract volume (mL); Valiquot is the titrated aliquot volume (mL); DF is any additional dilution factor (dimensionless; 1 if none); and W is the fresh sample mass (g).

2.12. Statistical Data Analyses

The data obtained were subjected to the Shapiro–Wilk normality test and Bartlett’s test for homogeneity of variances. The data were then analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with R Studio software (R version 4.4.2). Means were compared using Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05). For the yield variable (Mg ha−1), the assumptions of normality and homogeneity were not met. Standard transformations (logarithmic, arcsine, or square root) were applied, but the assumptions were not corrected. Consequently, a nonparametric approach was adopted: the Kruskal–Wallis test was applied for global contrast, and, when significant, Dunn’s multiple post hoc comparisons with Bonferroni adjustment were performed to control the type I error.

3. Results

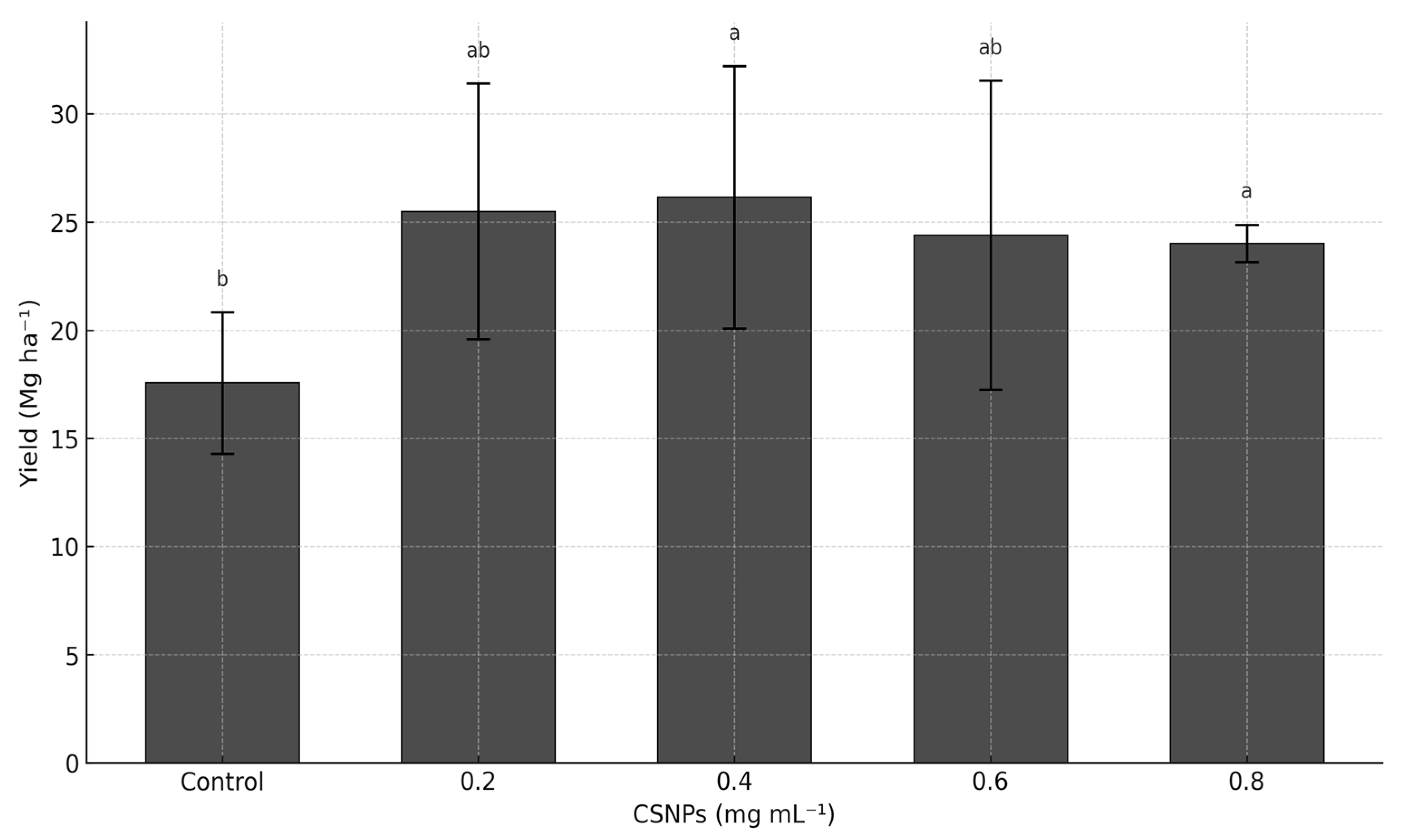

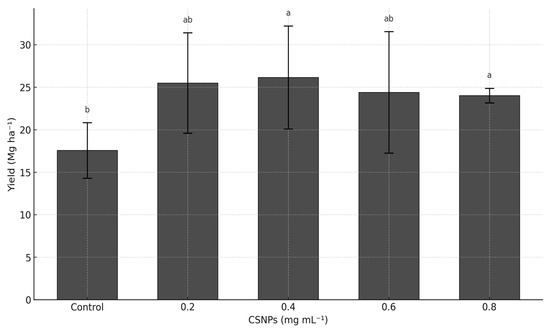

The foliar application of CSNPs significantly increased melon yield compared to the untreated control (p ≤ 0.05). No significant differences were detected between the 0.2–0.8 mg mL−1 doses of CSNPs (p > 0.05), with yields ranging from 24 to 26 Mg ha−1, exceeding the control treatment by 37 to 48%. The control treatment recorded the lowest yield at 17.57 Mg ha−1 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effect of chitosan nanoparticles (CSNPs) on melon yield (Mg ha−1). The bars show mean ± standard deviation. Means with equal letters in columns (a, b) do not differ significantly according to Dunn’s test with Bonferroni adjustment (p ≤ 0.05) following a Kruskal–Wallis test.

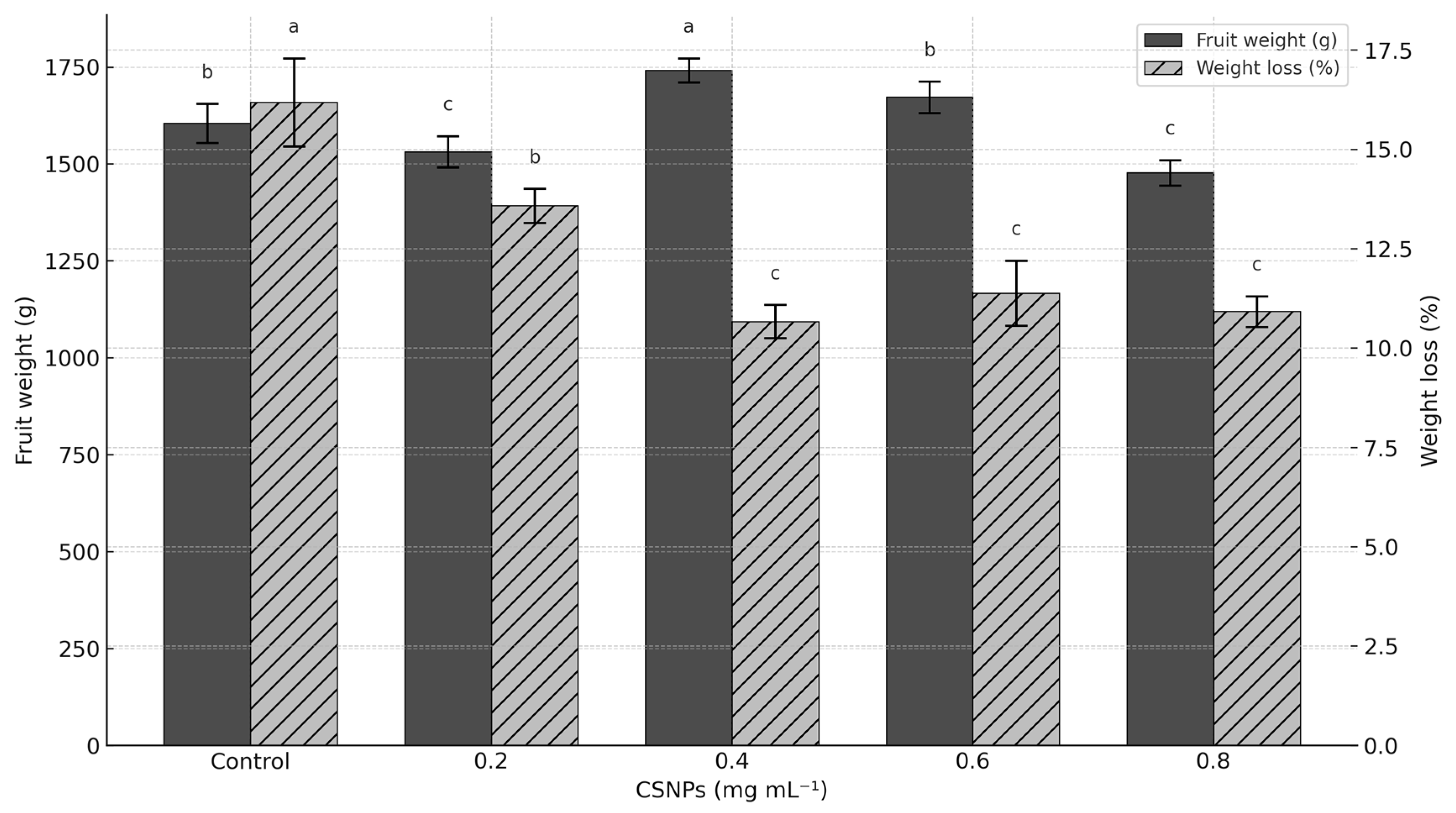

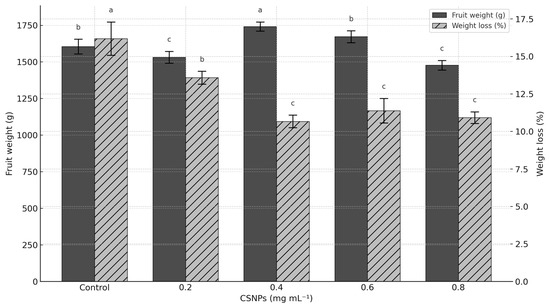

Fruit weight only increased (p ≤ 0.05) with the application of 0.4 mg ml−1 CSNP (+8.48% compared to the control). Concentrations of 0.6 mg ml−1 CSNP showed no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) compared to the control treatment. The highest concentration of CSNP (0.8 mg ml−1) produced the lowest fruit weight (p > 0.05) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of foliar application of chitosan nanoparticles (CSNPs) on fruit weight and weight loss in melons. Means with equal letters in columns (a, b, c) do not differ significantly according to Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05). The bars show mean ± standard deviation.

The application of CSNP reduced postharvest weight loss in melon fruits compared to the control. Concentrations of 0.4 to 0.8 mg mL−1 showed the lowest weight loss values, reducing weight loss by more than 35%, with no statistical differences between them (p > 0.05). The concentration of 0.2 mg ml−1 showed statistical differences (p ≤ 0.05) with the rest of the CSNP concentrations; however, it was still higher than the control treatment (Figure 2).

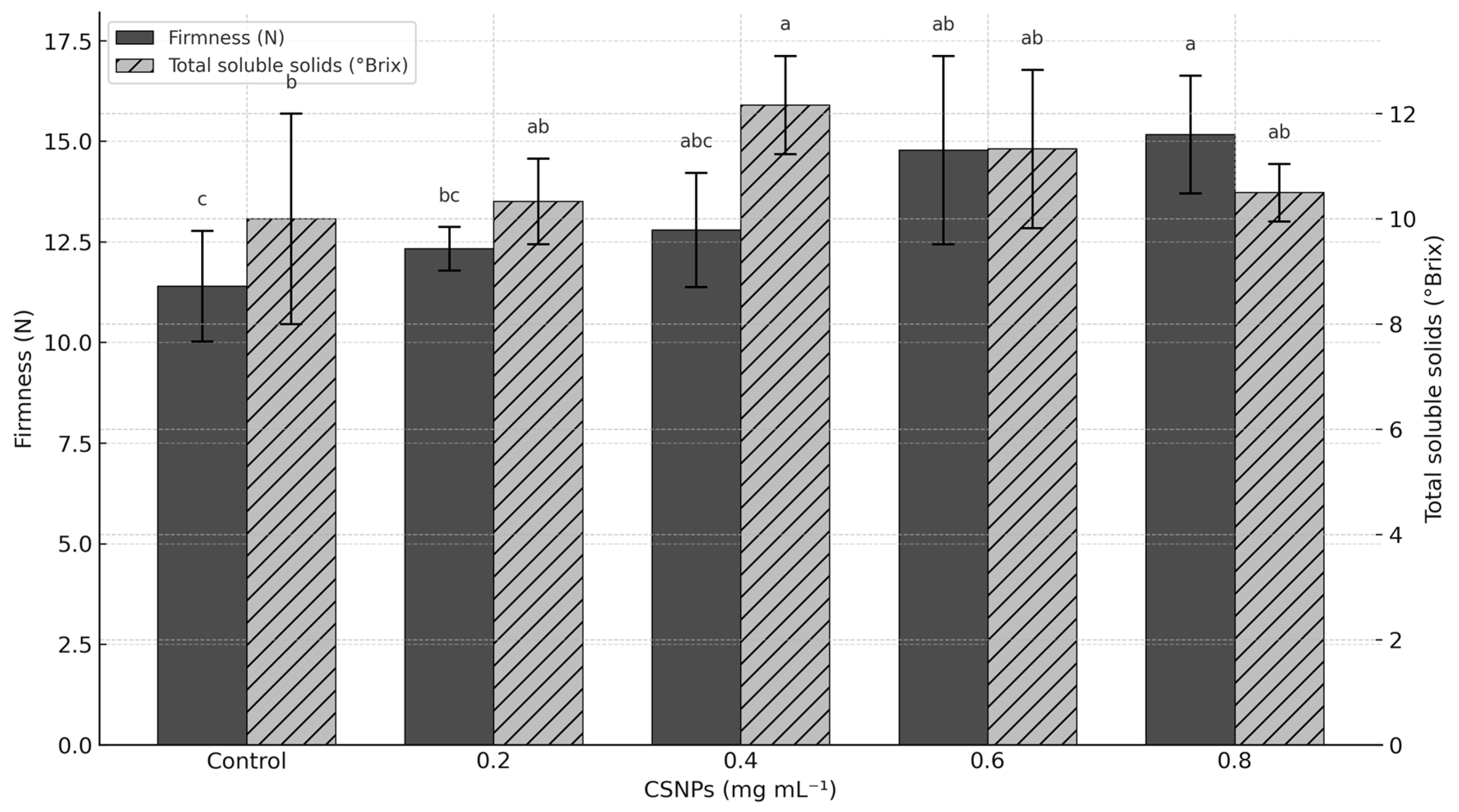

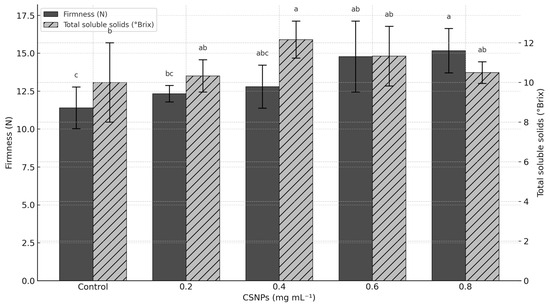

Fruit firmness increased with CSNP dosage, reaching maximum values at 0.6 mg mL−1 (14.78 N) and 0.8 mg mL−1 (15.17 N) compared to the control treatment (p ≤ 0.05), increasing firmness by more than 31%. However, low CSNP concentrations (0.2 and 0.4 mg mL−1) showed no differences from the control (p > 0.05) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of chitosan nanoparticles (CSNPs) on the firmness and total soluble solids of melon fruit. Means with equal letters in columns (a, b, c) do not differ significantly according to Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05). The bars show mean ± standard deviation.

The concentration of 0.4 mg mL−1 of CSNP increased total soluble solids (Brix) by 21.70% compared to the control treatment (p ≤ 0.05). The other CSNP concentrations did not exceed the control treatment (p > 0.05); however, the control treatment had the lowest Brix concentration (10.01 Brix) (Figure 3).

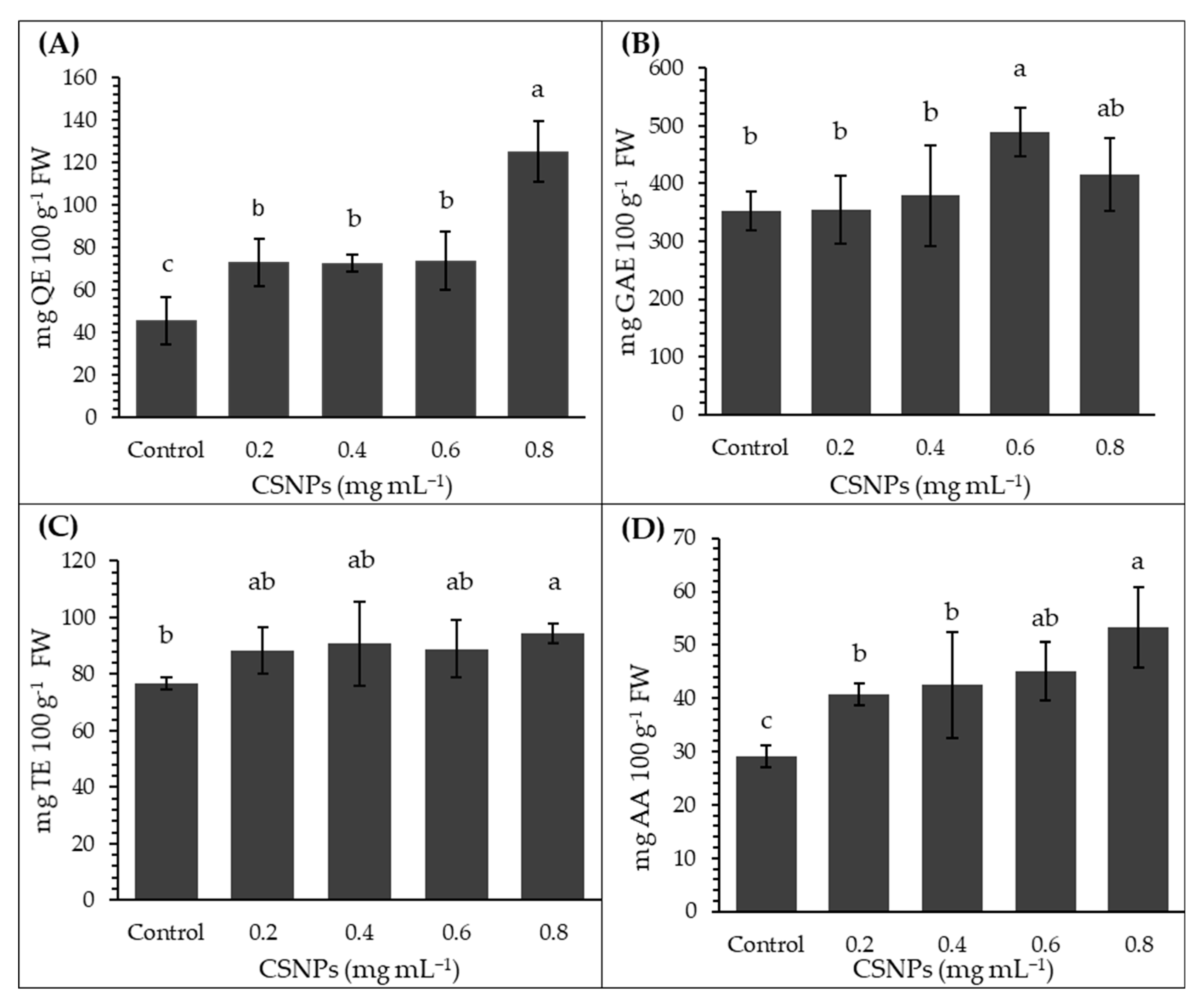

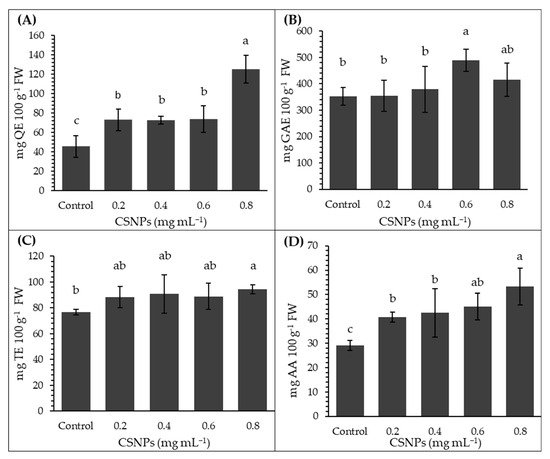

The highest total flavonoid content in melon fruits was obtained with the 0.8 mg mL−1 CSNP treatment, exceeding the control treatment by 175% and showing statistically significant differences with the other treatments (p ≤ 0.05). No statistical differences were observed between the 0.2 to 0.6 mg mL−1 treatments (p > 0.05); however, they were superior to the control treatment (Figure 4A). Regarding total phenol content, only the concentration of 0.6 mg mL−1 of CSNP was higher than the control treatment by 38%; however, it did not differ significantly from the concentration of 0.8 mg mL−1 (p > 0.05). The lowest total phenol content was obtained with concentrations of 0.2 and 0.4 mg mL−1, which did not show statistical differences with the control treatment (p > 0.05) (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Effect of foliar chitosan nanoparticles (CSNPs) on antioxidant capacity and bioactive compounds in melon fruit. (A) Total flavonoids. (B) Total phenols. (C) Antioxidant capacity. (D) Vitamin C. Means with equal letters in columns (a, b, c) do not differ significantly according to Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05). The bars show mean ± standard deviation.

CSNPs only increased antioxidant capacity compared to the control treatment (p ≤ 0.05) at the highest concentration (0.8 mg mL−1); intermediate concentrations (0.2–0.6 mg mL−1) were statistically comparable to the control (p > 0.05) (Figure 4C). Concentrations of 0.6 and 0.8 mg mL−1 of CSNP increased vitamin C content compared to the control (p ≤ 0.05) by 54% and 82%, respectively. All CSNP concentrations produced higher vitamin C content levels than the control treatment (p ≤ 0.05). The lowest value corresponded to the control group (Figure 4D).

In summary, the effects of CSNPs were highly concentration-dependent. The intermediate dose of 0.4 mg mL−1 was most effective for enhancing yield and total soluble solids, whereas the highest dose of 0.8 mg mL−1 consistently provided the greatest improvement in fruit firmness, antioxidant capacity, and concentration of flavonoids and vitamin C.

4. Discussion

Our results show that the application of CSNPs in melon cultivation increases yields by 48%, specifically at a concentration of 0.4 mg mL−1. In addition, postharvest weight loss was reduced by 35% at concentrations of 0.4–0.8 mg mL−1, and firmness increased by 31% at concentrations of 0.6–0.8 mg mL−1. Regarding nutraceutical quality, the concentration of 0.8 mg mL−1 increased the total flavonoid content, vitamin C, and antioxidant capacity by 175, 82, and 23%, respectively, while the concentration of 0.6 mg mL−1 increased the total phenol content by 38%.

The functional superiority of CSNPs is attributed to their greater specific surface area and positive charge, which promote adhesion and leaf retention [36,37]. This mode of action facilitates defense responses in plants (priming) with modulation of salicylic acid (SA) and jasmonic acid (JA) pathways and cell wall reinforcement (chitinases, β-1,3-glucanases, and polyphenoloxidases), which reduces oxidative damage and improves reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis [21,38,39]. In terms of the plant’s physiology, these changes translate into better photosynthetic performance, water use, and membrane stability, factors that contribute to greater partitioning of photoassimilates to the fruit and, therefore, greater weight and yield [17,40].

In our study, the application of CSNPs increased fruit weight (using up to 0.4 mg mL−1) and reduced postharvest weight loss (effect of 0.4–0.8 mg mL−1) compared to the control. The increase in fruit weight can be explained by improvements in water status and membrane integrity, which reduce respiratory costs and promote the accumulation of solids [41,42]. When fruit weight loss was evaluated at 7 days, the CSNP treatments showed less loss than the control. These results may be due to indirect effects such as enzyme reinforcement and lower lipid peroxidation, which would contribute to maintaining the integrity of the epidermis and cuticle. A metabolic profile with greater antioxidant capacity and better osmoregulation would attenuate respiration and transpiration, and possible microstructural modifications of the cuticle would reduce its effective permeability to water vapor [42,43,44].

The increase in fruit weight observed at 0.4 mg mL−1 is consistent with greater cell expansion and the deposition of wall biomolecules, in a context of improved photoassimilate partitioning and water status; these processes, reported under chitosan/CSNP applications, have been linked to greater fruit mass and firmness [45,46]. However, higher doses (0.6 and 0.8 mg mL−1) did not maintain this effect, reinforcing the importance of using intermediate concentrations to maximize benefits without inducing toxicity. Although the average fruit weight was lower with 0.8 mg mL−1 (Figure 2), the yield (=number of fruits × average weight × marketable proportion) did not change compared to 0.4–0.6 mg mL−1 (Figure 1). This is consistent with a trade-off between yield components, a higher number of fruits, and/or a higher proportion of marketable fruit, which was not quantified in this trial.

In melons, yield is related to the source-sink balance and the partitioning of photoassimilates to the fruit, which together determine fruit number per plant and individual fruit weight. This principle, described in cucurbits, supports the idea that increases in sink strength or carbon transfer efficiency during fruit expansion translate into higher commercial mass (yield) [47,48,49]. CSNPs have been shown to improve plant physiological performance, increase photosynthesis/chlorophyll status, and improve water status and membrane stability with less peroxidation, which reduces respiratory costs and promotes the accumulation of solids in the fruit, reinforcing source-sink efficiency during filling [17,23,50].

In addition, these effects are attributed to CSNPs’ ability to activate key physiological processes such as cell division and elongation, enzymatic activation, protein synthesis, and gene expression regulation, thereby enhancing nutrient metabolism and tolerance to biotic and abiotic stress [51,52]. However, doses higher than 0.4 mg mL−1 reduced yield, indicating that the effect of CSNPs is dependent on an optimal concentration range. Overdosing may negatively alter plant metabolism, causing hormonal imbalances and oxidative stress, which can lead to phytotoxic effects and reduced productivity [29].

In terms of commercial fruit quality, CSNPs also showed positive effects due to their ability to induce metabolic pathways related to chlorophyll synthesis, growth regulators, sugars, and antioxidants, thereby improving plant physiology and tolerance to biotic and abiotic stress [53].

In our experiment, CSNPs increased TSS by 21.70%. This may be related to improved assimilation and transfer of carbohydrates to the fruit during the filling phase. CSNPs have been shown to improve physiological traits (photosynthesis, chlorophyll status, water status, and membrane integrity) and are associated with fruits with higher solute content. For example, in cucumbers, foliar applications of chitosan increased Brix and other quality attributes compared to the control, supporting the link between biostimulation and solid accumulation in reproductive organs [54]. In melons, layered coatings (including matrices with chitosan) have shown higher Brix values at the end of storage compared to the uncoated control, related to better fruit preservation and lower consumption of fermentable sugars [55]. However, at the highest dose (0.8 mg mL−1), TSS levels decreased, indicating a dose-dependent response [56].

Regarding fruit firmness, the 0.6 and 0.8 mg mL−1 doses resulted in increases of 31 and 34.5%, respectively, compared to the control. This improvement is attributed to the role of chitosan in stabilizing the cell wall by inhibiting the degradation of protopectins into soluble pectins [57,58]. The observed improvements in firmness are consistent with the regulation of enzymes related to softening in the plant, including the inhibition of polygalacturonase (PG), pectin methylesterase (PME), and β-glucosidase/β-galactosidase [57,59,60]. These effects are consistent with the reduction in cell wall-degrading enzyme activities [57] and the attenuation of ethylene production [61], which together contribute to maintaining firmness and extending shelf life. In Cucumis melo, chitosan matrices have been shown to maintain postharvest quality by preserving firmness and Brix, sustaining higher levels of vitamin C, and reducing H2O2. This performance is associated with lower wall hydrolase activity (PG and PME), lower browning enzyme activity (PPO/GPOD), and better structural integrity of membranes and cell walls observed histologically. These results in the same species support our findings of higher firmness and lower weight loss, although our focus was on preharvest [62]. Furthermore, in melon, chitosan treatments have been shown to preserve firmness and reduce postharvest weight loss by modulating cell wall and starch/sucrose metabolism. In Hami melon, a chitosan coating reduced softening, associated with lower pectin solubilization and a reprogramming of sugar metabolism [46].

The foliar application of CSNPs significantly increased the accumulation of bioactive compounds in melon fruits, with notable enhancements in total flavonoids, phenolic compounds, vitamin C, and antioxidant capacity. These results highlight chitosan’s role as a metabolic elicitor capable of inducing biosynthetic pathways associated with the production of nutraceutical secondary metabolites [15].

Total flavonoids increased significantly with the 0.8 mg mL−1 dose of CSNPs, reaching 175% more than the control treatment. This substantial increase reinforces chitosan’s role as an elicitor, which, when perceived by plant cells as a fungal-derived molecule, activates defense mechanisms similar to those triggered by phytopathogens [63]. Foliar spraying of chitosan oligosaccharides on strawberry crops significantly increased flavonoids; the content rose from 21.34 to 29.59 mg·g−1 (+38% vs. control) and also improved total phenols [64], results similar to those reported in our work. This increase is also associated with the activation of redox signaling pathways and the expression of defense-related genes [65,66]. Overall, the increase in flavonoids observed with CSNPs is consistent with reports that these nanoparticles significantly increase total flavonoids and other phenols in plant tissues, and with evidence that chitosan acts as an elicitor of the phenylpropanoid–flavonoid pathway (activation of PAL, CHS, CHI, F3H, and FLS/DFR) [15,23,67]. This increase contributes to non-enzymatic antioxidant capacity, complements SOD/CAT/APX in ROS control, and is associated with improved membrane integrity and physiological performance during fruit filling and ripening [68,69].

For phenolic compounds, significant increases were observed with the 0.6 and 0.8 mg mL−1 doses, surpassing the control by 38% and 18%, respectively. These compounds play essential antioxidant roles and are associated with fruit pigmentation, flavor, and postharvest stability [70]. Their increased content may be due to the accumulation of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) as a stress signal, which activates metabolic pathways related to phenol production as part of the plant’s defense response [71].

Antioxidant capacity also improved significantly with the 0.8 mg mL−1 dose of CSNPs. This effect can be attributed to chitosan’s regulation of redox balance, which reduces the production of ROS and promotes the synthesis of antioxidants such as flavonoids, phenolic compounds, carotenoids, and anthocyanins [18,72].

Previous reports have consistently shown that pre- and postharvest applications of chitosan, including chitosan nanoparticles, increase antioxidant capacity as measured by DPPH/ABTS/FRAP, in parallel with increases in total phenols, flavonoids, anthocyanins, carotenoids, and ascorbate, i.e., the total content of non-enzymatic antioxidants [23,57,73]. At the same time, CSNPs/chitosan strengthen the enzymatic machinery (SOD, CAT, APX, and GR), reduce H2O2, MDA, and electrolyte leakage, and improve membrane integrity [16,74]. This dual effect increases the buffering capacity of ROS during fruit filling and ripening.

Further contributing to the enhanced antioxidant profile, vitamin C content also showed a significant increase with the 0.6 and 0.8 mg mL−1 doses, registering an 82% increase compared to the control. Chitosan stimulates the biosynthesis of ascorbic acid through its involvement in the ascorbate-glutathione cycle, a key mechanism for ROS neutralization and maintaining cellular metabolism under stress conditions [75]. Moreover, vitamin C plays important roles in antioxidant defense, regulation of senescence, and postharvest fruit quality [76].

Thus, our results show that there is no single optimal dose for all variables but rather a functional range depending on the objective: yield was maximized at 0.4 mg mL−1; firmness, vitamin C, and total phenols reached their highest values at 0.6–0.8 mg mL−1; and antioxidant capacity only exceeded the control at 0.8 mg mL−1. Therefore, moderate doses favor commercial mass without penalizing yield, while high doses prioritize postharvest and nutraceutical attributes. The selection of doses should be adjusted to the management objective (yield vs. shelf life/quality), the sensitivity of the cultivar, and environmental conditions. Furthermore, no additional yield gains were observed above 0.4 mg mL−1. This dose-objective differentiation is a practical contribution of the study and guides the implementation of CSNPs in sustainable intensification programs.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that chitosan nanoparticles (CSNPs), applied preharvest via foliar application, are an effective tool for optimizing the productive performance and nutraceutical quality of melons. An intermediate dose (0.4 mg mL−1) maximizes commercial productivity (higher weight without penalizing yield), while doses of 0.6–0.8 mg mL−1 prioritize postharvest and nutraceutical quality attributes (more firmness, vitamin C, phenols/flavonoids, and antioxidant capacity), without further increasing yield. Therefore, foliar spraying of chitosan nanoparticles represents a sustainable strategy for improving the yield, postharvest quality, and functional attributes of melon fruits. These results offer a practical management criterion: select the CSNPs dose according to the objective (commercial volume vs. shelf life and nutraceutical value).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.T.-R. and P.P.-R.; methodology, J.A.T.-R., J.J.R.-P. and P.P.-R.; software, E.R.M.-G. and L.G.H.-M.; validation, E.R.M.-G., L.G.H.-M. and F.N.-R.; formal analysis, J.A.T.-R., L.G.H.-M. and J.J.R.-P.; investigation, F.N.-R., P.P.-R. and H.O.-O.; resources, P.P.-R. and H.O.-O.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A.T.-R., J.J.R.-P. and P.P.-R.; writing—review and editing, E.R.M.-G., L.G.H.-M. and P.P.-R.; visualization, J.J.R.-P., J.A.T.-R. and P.P.-R.; supervision, F.N.-R., L.G.H.-M. and J.A.T.-R.; project administration, P.P.-R.; funding acquisition, P.P.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of the National Council for Humanities, Sciences, and Technology (CONAHCYT, Mexico) through project A1-S-20923.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Burian, A.; Kremen, C.; Wu, J.S.-T.; Beckmann, M.; Bulling, M.; Garibaldi, L.A.; Krisztin, T.; Mehrabi, Z.; Ramankutty, N.; Seppelt, R. Biodiversity–Production Feedback Effects Lead to Intensification Traps in Agricultural Landscapes. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 8, 752–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swaine, M.; Bergna, A.; Oyserman, B.; Vasileiadis, S.; Karas, P.A.; Screpanti, C.; Karpouzas, D.G. Impact of Pesticides on Soil Health: Identification of Key Soil Microbial Indicators for Ecotoxicological Assessment Strategies through Meta-Analysis. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2025, 101, fiaf052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.K.; Sanghvi, G.; Yadav, M.; Padhiyar, H.; Christian, J.; Singh, V. Fate of Pesticides in Agricultural Runoff Treatment Systems: Occurrence, Impacts and Technological Progress. Environ. Res. 2023, 237, 117100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zeleke, K.; Wang, B.; Liu, D.-L. A Review of Data for Compound Drought and Heatwave Stress Impacts on Crops: Current Progress, Knowledge Gaps, and Future Pathways. Plants 2025, 14, 2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyuo, J.; Sackey, L.N.A.; Yeboah, C.; Kayoung, P.Y.; Koudadje, D. The Implications of Pesticide Residue in Food Crops on Human Health: A Critical Review. Discov. Agric. 2024, 2, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Jardin, P. Plant Biostimulants: Definition, Concept, Main Categories and Regulation. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groote, H.; Tessema, M.; Gameda, S.; Gunaratna, N.S. Soil Zinc, Serum Zinc, and the Potential for Agronomic Biofortification to Reduce Human Zinc Deficiency in Ethiopia. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, Y.; Cao, D.; Hu, J.; Lin, Y.; Dang, C.; Xue, D. The Application, Safety, and Challenge of Nanomaterials on Plant Growth and Stress Tolerance. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 222, 119691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, L.; Shrivastava, M.; Srivastava, S.; Cota-Ruiz, K.; Zhao, L.; White, J.C.; Hernandez-Viezcas, J.A.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.L. Nanomaterials for Managing Abiotic and Biotic Stress in the Soil–Plant System for Sustainable Agriculture. Environ. Sci. Nano 2025, 12, 1037–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ul-Islam, M.; Alabbosh, K.F.; Manan, S.; Khan, S.; Ahmad, F.; Ullah, M.W. Chitosan-Based Nanostructured Biomaterials: Synthesis, Properties, and Biomedical Applications. Adv. Ind. Eng. Polym. Res. 2024, 7, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benettayeb, A.; Seihoub, F.Z.; Pal, P.; Ghosh, S.; Usman, M.; Chia, C.H.; Usman, M.; Sillanpää, M. Chitosan Nanoparticles as Potential Nano-Sorbent for Removal of Toxic Environmental Pollutants. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, T.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Du, L. Synthesis, Characterization of Chitosan/Tripolyphosphate Nanoparticles Loaded with 4-Chloro-2-Methylphenoxyacetate Sodium Salt and Its Herbicidal Activity against Bidens pilosa L. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshayb, O.M.; Ghazy, H.A.; Wissa, M.T.; Farroh, K.Y.; Wasonga, D.O.; Seleiman, M.F. Chitosan-Based NPK Nanostructure for Reducing Synthetic NPK Fertilizers and Improving Rice Productivity and Nutritional Indices. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1464021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, J.; Durand, A.; Desobry, S. Chitosan-Based Particulate Carriers: Structure, Production and Corresponding Controlled Release. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xoca-Orozco, L.-Á.; Aguilera-Aguirre, S.; Vega-Arreguín, J.; Acevedo-Hernández, G.; Tovar-Pérez, E.; Stoll, A.; Herrera-Estrella, L.; Chacón-López, A. Activation of the Phenylpropanoid Biosynthesis Pathway Reveals a Novel Action Mechanism of the Elicitor Effect of Chitosan on Avocado Fruit Epicarp. Food Res. Int. 2019, 121, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, F.A.S.; Ali, E.; Gaber, A.; Fetouh, M.I.; Mazrou, R. Chitosan Nanoparticles Effectively Combat Salinity Stress by Enhancing Antioxidant Activity and Alkaloid Biosynthesis in Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 162, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenazi, M.M.; El-Ebidy, A.M.; El-shehaby, O.A.; Seleiman, M.F.; Aldhuwaib, K.J.; Abdel-Aziz, H.M.M. Chitosan and Chitosan Nanoparticles Differentially Alleviate Salinity Stress in Phaseolus vulgaris L. Plants. Plants 2024, 13, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishkeh, S.R.; Shirzad, H.; Asghari, M.; Alirezalu, A.; Pateiro, M.; Lorenzo, J.M. Effect of Chitosan Nanoemulsion on Enhancing the Phytochemical Contents, Health-Promoting Components, and Shelf Life of Raspberry (Rubus sanctus Schreber). Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, S.-C.; Chandrasekaran, M. Chitosan and Chitosan Nanoparticles Induced Expression of Pathogenesis-Related Proteins Genes Enhances Biotic Stress Tolerance in Tomato. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 125, 948–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahman, F.A.; Monir, G.A.; Hassan, M.S.S.; Ahmed, Y.; Refaat, M.H.; Ismail, I.A.; El-Garhy, H.A.S. Exogenously Applied Chitosan and Chitosan Nanoparticles Improved Apple Fruit Resistance to Blue Mold, Upregulated Defense-Related Genes Expression, and Maintained Fruit Quality. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; He, M.; Wang, X.; Liu, S.; Luo, L.; Zeng, Q.; Wu, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Yang, Z.; Sheng, G.; et al. Emerging Nanochitosan for Sustainable Agriculture. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancilla-Álvarez, E.; Serrano-Fuentes, M.K.; Fuentes-Torres, M.A.; Sánchez-Páez, R.; Bello-Bello, J.J. Chitosan Nanoparticles: An Alternative for In Vitro Multiplication of Sugarcane (Saccharum Spp.) in Semi-Automated Bioreactors. Plants 2025, 14, 1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attaran Dowom, S.; Karimian, Z.; Mostafaei Dehnavi, M.; Samiei, L. Chitosan Nanoparticles Improve Physiological and Biochemical Responses of Salvia abrotanoides (Kar.) under Drought Stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, H.; Mao, J.; Wu, L.; Li, J.; Wang, X. Variations of Physical Properties, Bioactive Phytochemicals, Antioxidant Capacities and PPO Activities of Cantaloupe Melon (Cucumis melo L.) Slices Subjected to Different Drying Methods. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1548271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okcu, Z.; Yangılar, F. Quality Parameters and Antioxidant Activity, Phenolic Compounds, Sensory Properties of Functional Yogurt with Melon (Cucumis melo L.) Peel Powder. Turk. J. Agric. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 12, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro, A.L.; Spadafora, N.D.; Pereira, M.J.; Dhorajiwala, R.; Herbert, R.J.; Müller, C.T.; Rogers, H.J.; Pintado, M. Multitrait Analysis of Fresh-Cut Cantaloupe Melon Enables Discrimination between Storage Times and Temperatures and Identifies Potential Markers for Quality Assessments. Food Chem. 2018, 241, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Xu, B.-T.; Xu, X.-R.; Gan, R.-Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, E.-Q.; Li, H.-B. Antioxidant Capacities and Total Phenolic Contents of 62 Fruits. Food Chem. 2011, 129, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumaraswamy, R.V.; Kumari, S.; Choudhary, R.C.; Pal, A.; Raliya, R.; Biswas, P.; Saharan, V. Engineered Chitosan Based Nanomaterials: Bioactivities, Mechanisms and Perspectives in Plant Protection and Growth. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 113, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Rodríguez, S.; Preciado-Rangel, P.; Cabrera-De, M.; González-Morales, S.; Ortega-Ortiz, H. Chitosan Nanoparticles as Biostimulant in Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) Plants. Phyton 2024, 93, 777–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Jiang, X.; Deng, Y.; Xu, K.; Duan, X.; Wan, K.; Tang, X. Study on Characteristics and Lignification Mechanism of Postharvest Banana Fruit during Chilling Injury. Foods 2023, 12, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Cegrí, A.; Carvajal, F.; Osorio, S.; Jamilena, M.; Garrido, D.; Palma, F. Postharvest Abscisic Acid Treatment Modulates the Primary Metabolism and the Biosynthesis of T-Zeatin and Riboflavin in Zucchini Fruit Exposed to Chilling Stress. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2023, 204, 112457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, V.R.; Pereira, P.A.P.; da Silva, T.L.T.; de Oliveira Lima, L.C.; Pio, R.; Queiroz, F. Determination of the Bioactive Compounds, Antioxidant Activity and Chemical Composition of Brazilian Blackberry, Red Raspberry, Strawberry, Blueberry and Sweet Cherry Fruits. Food Chem. 2014, 156, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén-Enríquez, R.R.; Sánchez-Chávez, E.; Fortis-Hernández, M.; Márquez-Guerrero, S.Y.; Espinosa-Palomeque, B.; Preciado-Rangel, P. ZnO Nanoparticles Improve Bioactive Compounds, Enzymatic Activity and Zinc Concentration in Grapevine. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2023, 51, 13377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a Free Radical Method to Evaluate Antioxidant Activity. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.S. Vitamin C Determination by Indophenol Method. In Nielsen’s Food Analysis Laboratory Manual; Ismail, B.P., Nielsen, S.S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 153–156. ISBN 978-3-031-44970-3. [Google Scholar]

- Saberi Riseh, R.; Vatankhah, M.; Hassanisaadi, M.; Varma, R.S. A Review of Chitosan Nanoparticles: Nature’s Gift for Transforming Agriculture through Smart and Effective Delivery Mechanisms. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 260, 129522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Zhou, Q.; Xiao, J.; Qin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, H. Nanoparticle LDH Enhances RNAi Efficiency of dsRNA in Piercing-Sucking Pests by Promoting dsRNA Stability and Transport in Plants. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poznanski, P.; Shalmani, A.; Bryla, M.; Orczyk, W. Salicylic Acid Mediates Chitosan-Induced Immune Responses and Growth Enhancement in Barley. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukarram, M.; Ali, J.; Dadkhah-Aghdash, H.; Kurjak, D.; Kačík, F.; Ďurkovič, J. Chitosan-Induced Biotic Stress Tolerance and Crosstalk with Phytohormones, Antioxidants, and Other Signalling Molecules. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1217822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, S.; Shah, A.A.; Kaleem, M.; Noreen, Z.; Xu, W.; Mahmoud, E.A.; Elansary, H.O. Chitosan-Copper Nanocomposites Exterminate Cd Toxicity in Capsicum annuum L. through Improving Photosynthetic Attributes, Antioxidant Defense, and Reduced Cd Uptake. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 32879–32894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Li, N.; Lin, H.; Lin, M.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Ritenour, M.A.; Lin, Y. Effects of Chitosan Treatment on the Storability and Quality Properties of Longan Fruit during Storage. Food Chem. 2020, 306, 125627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Wu, S. Application of Chitosan in Fruit Preservation: A Review. Food Chem. X 2024, 23, 101589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Chen, G.; Lin, H.; Lin, M.; Wang, H.; Lin, Y. Chitosan Postharvest Treatment Suppresses the Pulp Breakdown Development of Longan Fruit through Regulating ROS Metabolism. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 165, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, T.M.P.; Nguyen, T.H.; Dang, T.M.Q.; Do, T.V.T.; Reungsang, A.; Chaiwong, N.; Rachtanapun, P. Effect of Pectin/Nanochitosan-Based Coatings and Storage Temperature on Shelf-Life Extension of “Elephant” Mango (Mangifera indica L.) Fruit. Polymers 2021, 13, 3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Xu, X.; Xue, S.; Gong, D.; Wang, B.; Zheng, X.; Xie, P.; Bi, Y.; Prusky, D. Preharvest Multiple Sprays with Chitosan Promotes the Synthesis and Deposition of Lignin at Wounds of Harvested Muskmelons. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 206, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Tang, F.; Cai, W.; Peng, B.; Ning, M.; Shan, C.; Yang, X. Chitosan Treatment Reduces Softening and Chilling Injury in Cold-Stored Hami Melon by Regulating Starch and Sucrose Metabolism. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1096017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Gu, J.; Chen, C.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Hua, B.; Miao, M. The Sink-Source Relationship in Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) Is Modulated by DNA Methylation. Plants 2023, 13, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valantin, M.; Gary, C.; Vaissière, B.E.; Frossard, J.S. Effect of Fruit Load on Partitioning of Dry Matter and Energy in Cantaloupe (Cucumis melo L.). Ann. Bot. 1999, 84, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Nuñez Ocaña, D.; Choe, D.; Larsen, D.H.; Marcelis, L.F.M.; Heuvelink, E. Far-Red Radiation Stimulates Dry Mass Partitioning to Fruits by Increasing Fruit Sink Strength in Tomato. New Phytol. 2020, 228, 1914–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.; Al-Azawi, T.N.I.; Methela, N.J.; Rolly, N.K.; Khan, M.; Faluku, M.; Huy, V.N.; Lee, D.-S.; Mun, B.-G.; Hussian, A.; et al. Chitosan-Fulvic Acid Nanoparticles Enhance Drought Tolerance in Maize via Antioxidant Defense and Transcriptional Reprogramming. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, M.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Rahman, M.; Khan, M.A.R.; Bhowmik, P.; Mahmud, N.U.; Tanveer, M.; Islam, T. Mechanism of Plant Growth Promotion and Disease Suppression by Chitosan Biopolymer. Agriculture 2020, 10, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, D.; Pal, A.; Dimkpa, C.; Harish; Singh, U.; Devi, K.A.; Choudhary, J.L.; Saharan, V. Chitosan Nanomaterials: A Prelim of next-Generation Fertilizers; Existing and Future Prospects. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 288, 119356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bécquer Granados, C.J.; González Cañizares, P.J.; Ávila Cordoví, U.; Nápoles Gómez, J.Á.; Galdo Rodríguez, Y.; Muir Rodríguez, I.; Hernández Obregón, M.; Quintana Sanz, M.; Medinilla Nápoles, F. Efecto de La Inoculación de Microorganismos Benéficos y Quitomax® En Cenchrus ciliaris L., En Condiciones de Sequía Agrícola. Pastos y Forrajes 2019, 42, 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Dawa, K.K.; Metwaly, E.E.; Swelam, W.M.E.; Morgan, A.F.F.M. Response of Some Cucumber Cultivars Grown under High Plastic Tunnels to Grafting and Some Foliar Application Treatments. J. Plant Prod. 2022, 13, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cice, D.; Ferrara, E.; Pecoraro, M.T.; Capriolo, G.; Petriccione, M. An Innovative Layer-by-Layer Edible Coating to Regulate Oxidative Stress and Ascorbate–Glutathione Cycle in Fresh-Cut Melon. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles-Ozuna, L.E.; Goycoolea, F.M.; Silveira, M.I. Uso Del Quitosano Durante El Escaldado Del Nopal (Opuntia ficus indica) y Efecto Sobre Su Calidad. Rev. Mex. De Ing. Química 2007, 6, 193–201. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, C. Application of Chitosan and Its Derivatives in Postharvest Coating Preservation of Fruits. Foods 2025, 14, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, S.; Anand, G.; Yadav, S.; Yadav, D. An Insight into Production Strategies for Microbial Pectinases: An Overview. In Microbial Enzymes; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 87–118. ISBN 978-3-527-84434-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.; Hao, D.; Tian, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Qin, G.; Pei, J.; Abd El-Aty, A.M. Effect of Chitosan/Thyme Oil Coating and UV-C on the Softening and Ripening of Postharvest Blueberry Fruits. Foods 2022, 11, 2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassem, H.S.; Tarabih, M.E.; Ismail, H.; Eleryan, E.E. Influence of Nano-Silica/Chitosan Film Coating on the Quality of ‘Tommy Atkins’ Mango. Processes 2022, 10, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-López, M.L.; Vieira, J.M.; Rocha, C.M.R.; Lagarón, J.M.; Cerqueira, M.A.; Jasso de Rodríguez, D.; Vicente, A.A. Postharvest Quality Improvement of Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) Fruit Using a Nanomultilayer Coating Containing Aloe vera. Foods 2024, 13, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, R.L.; Cabral, M.F.; Germano, T.A.; de Carvalho, W.M.; Brasil, I.M.; Gallão, M.I.; Moura, C.F.H.; Lopes, M.M.A.; de Miranda, M.R.A. Chitosan Coating with Trans-Cinnamaldehyde Improves Structural Integrity and Antioxidant Metabolism of Fresh-Cut Melon. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2016, 113, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sree Rayanoothala, P.; Dweh, T.J.; Mahapatra, S.; Kayastha, S. Unveiling the Protective Role of Chitosan in Plant Defense: A Comprehensive Review with Emphasis on Abiotic Stress Management. Crop Des. 2024, 3, 100076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Bose, S.K.; Wang, W.; Jia, X.; Lu, H.; Yin, H. Pre-Harvest Treatment of Chitosan Oligosaccharides Improved Strawberry Fruit Quality. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malerba, M.; Cerana, R. Chitosan Effects on Plant Systems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harborne, J.B.; Williams, C.A. Advances in Flavonoid Research since 1992. Phytochemistry 2000, 55, 481–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackah, S.; Xue, S.; Osei, R.; Kweku-Amagloh, F.; Zong, Y.; Prusky, D.; Bi, Y. Chitosan Treatment Promotes Wound Healing of Apple by Eliciting Phenylpropanoid Pathway and Enzymatic Browning of Wounds. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 828914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shomali, A.; Das, S.; Arif, N.; Sarraf, M.; Zahra, N.; Yadav, V.; Aliniaeifard, S.; Chauhan, D.K.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Diverse Physiological Roles of Flavonoids in Plant Environmental Stress Responses and Tolerance. Plants 2022, 11, 3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, N.; Jiang, C.; Chen, L.; Paul, A.; Chatterjee, A.; Shen, G. Achieving Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants through Antioxidative Defense Mechanisms. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1110622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallek-Ayadi, S.; Bahloul, N.; Kechaou, N. Characterization, Phenolic Compounds and Functional Properties of Cucumis melo L. Peels. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 1691–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez González, L.; Reyes Guerrero, Y.; Falcón Rodríguez, A.; Núñez Vázquez, M. Efecto Del Tratamiento a Las Semillas Con Quitosana En El Crecimiento de Plántulas de Arroz (Oryza sativa L.) Cultivar INCA LP-5 En Medio Salino. Cultiv. Trop. 2015, 36, 143–150. [Google Scholar]

- Hajihashemi, S.; Kazemi, S. The Potential of Foliar Application of Nano-Chitosan-Encapsulated Nano-Silicon Donor in Amelioration the Adverse Effect of Salinity in the Wheat Plant. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Li, D.; Guo, L.; Hong, X.; He, S.; Huo, J.; Sui, X.; Zhang, Y. Enhancing Postharvest Quality and Antioxidant Capacity of Blue Honeysuckle Cv. ‘Lanjingling’ with Chitosan and Aloe vera Gel Edible Coatings during Storage. Foods 2024, 13, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackah, S.; Bi, Y.; Xue, S.; Yakubu, S.; Han, Y.; Zong, Y.; Atuna, R.A.; Prusky, D. Post-Harvest Chitosan Treatment Suppresses Oxidative Stress by Regulating Reactive Oxygen Species Metabolism in Wounded Apples. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 959762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pichyangkura, R.; Chadchawan, S. Biostimulant Activity of Chitosan in Horticulture. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Goes, G.B.; Dias, T.J.; Neri, D.K.P.; Filho, P.L.; da Silva Leal, M.P.; Henschel, J.M.; Batista, D.S.; da Silva Ribeiro, J.E.; da Silva, T.I.; de Mello Oliveira, M.D.; et al. Bioactivator, Phosphorus and Potassium Fertilization and Their Effects on Soil, Physiology, Production and Quality of Melon. Acta Physiol. Plant 2023, 45, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).