Abstract

This study investigates the shear performance of high-strength concrete (HSC) beams reinforced with steel, fiber composite grids (CFRP and GFRP), and their hybrid configurations in the absence of transverse reinforcement. A total of six full-scale beams with varying reinforcement configuration and shear span-to-depth (a/d) ratios were experimentally tested under monotonic loading to evaluate their load capacity, cracking characteristics, failure modes, and serviceability behavior. The results revealed that beams reinforced solely with fiber grids exhibited significantly reduced strength and brittle shear failure. Hybrid systems incorporating both steel and fiber grids demonstrated improved strength and ductility, closely matching or surpassing control specimens with conventional steel reinforcement. Key structural parameters such as effective moment of inertia, cracking moment, shear strength, and midspan deflection were compared against analytical predictions based on ACI 318-16 and the Canadian Education Module code. While predictions generally aligned for hybrid beams, notable discrepancies were found for FRP-only systems, particularly in serviceability performance. The findings highlight the potential of hybrid reinforcement as a viable design strategy for HSC beams, offering a balance between strength, ductility, and service performance.

1. Introduction

The adoption of High-Strength Concrete (HSC) in structural and non-structural applications has significantly increased in recent years, primarily due to its outstanding mechanical performance characterized by high compressive strength, enhanced durability, and superior resistance to cracking [1,2,3]. Despite these benefits, HSC exhibits distinct shear behavior compared to normal-strength concrete, primarily because of its increased brittleness and reduced strain capacity under high stress, which can result in sudden and brittle failures [4,5]. Additionally, the susceptibility of conventional steel reinforcement to corrosion, particularly in chloride-rich environments, continues to impose substantial maintenance costs over the life cycle of structures.

To overcome these issues, Fiber-Reinforced Polymers (FRPs), especially Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (CFRP) and Glass Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (GFRP), have emerged as promising alternatives to steel reinforcement [6,7,8]. These materials offer superior corrosion resistance, high tensile strength, low density, and electromagnetic neutrality, making them suitable for a wide range of civil engineering applications [9,10,11]. Understanding the shear behavior of HSC beams reinforced with FRP and steel is thus essential, especially given the different failure modes introduced by the distinct mechanical properties of FRPs.

CFRP bars, due to their high-strength and stiffness, have shown the capacity to enhance the flexural performance of concrete beams. However, their relatively brittle behavior and lower ductility compared to steel necessitate further investigation into their influence on shear performance [12,13,14]. The shear strength of CFRP-reinforced concrete beams is influenced by key parameters including the shear span-to-depth ratio, beam dimensions, and concrete compressive strength [13,15]. Notably, the inherent brittleness of CFRP necessitates the development of accurate prediction models to ensure safety and reliability in design [16]. Moreover, experimental studies have revealed that CFRP-reinforced beams display different cracking behaviors and failure mechanisms than steel-reinforced beams, emphasizing the need for design approaches tailored to CFRP systems [13].

Similarly, GFRP bars have also been extensively studied as internal reinforcement for HSC beams. GFRP-reinforced beams tend to exhibit wider shear cracks at lower load levels when compared to CFRP or steel-reinforced counterparts [13]. Research indicates that the shear behavior of GFRP-reinforced beams is sensitive-to-reinforcement ratio, beam geometry, and compressive strength of concrete, which should be accounted for in design [15]. Xian Li et al. [17] and Gao and Zhang [18] demonstrated that the superior properties of GFRP provide significant structural advantages, especially when stirrups are absent. They found that core concrete compressive strength plays a decisive role in determining the shear capacity of GFRP-reinforced beams. Furthermore, several investigations have shown that the mechanical properties of GFRP contribute positively to shear resistance in FRP-reinforced beams [11,12,15,19].

To overcome the limitations of FRP’s brittle nature and to benefit from steel’s ductility, researchers have explored hybrid reinforcement systems combining both steel and FRP bars [13,20,21]. This composite reinforcement strategy leverages the complementary strengths of each material, leading to improved mechanical performance under cyclic or dynamic loading conditions, as demonstrated by Yuan et al. [22]. Hybrid systems help mitigate the lack of ductility often associated with pure FRP reinforcement, while also capitalizing on FRP’s corrosion resistance and strength. Studies have further shown that FRP confinement improves not only the compressive strength but also the ductility of HSC columns, with beneficial effects under both static and dynamic loads [13,23,24]. Recent experimental studies have shown that carbon fabric-reinforced cementitious matrix (CFRCM) systems can significantly enhance the shear capacity of reinforced concrete beams, while existing design models often underestimate their contribution. These findings highlight the need for improved analytical approaches for shear-critical members strengthened with fabric-based systems [25]. Moreover, Wakjira and Ebead [26] developed a simplified compression field theory (SCFT)-based model to predict the shear strength of fabric-reinforced cementitious matrix (FRCM)-strengthened reinforced concrete beams, demonstrating good agreement with experimental data and existing design provisions. Their work highlights the value of mechanics-based shear models for fiber-reinforced systems and motivates further evaluation of such approaches for high-strength concrete beams with internal FRP or hybrid reinforcement.

Despite growing interest and research into FRP applications in HSC systems, limited data exist on the performance of HSC beams reinforced specifically with FRP grids. This knowledge gap hinders the development of optimized design methodologies for such systems.

The primary objective of this research is to investigate the shear behavior of HSC beams reinforced with hybrid systems incorporating conventional steel and fiber composite grids, specifically CFRP and GFRP grids. This study aims to clarify how the integration of FRP grids influences ductility, shear strength, and load-carrying capacity, compared to traditional reinforcement strategies. The results are expected to provide new insights into advancing the use of hybrid FRP-steel reinforcement systems in HSC structural elements and contribute to the development of more resilient, high-performance infrastructure.

2. Experimental Program

2.1. Materials

This section outlines various components and their properties which were utilized in designing, fabricating and carrying out experiments for all the beam specimens.

2.1.1. Formwork

Each beam was cast in a timber formwork assembled to the required dimensions. The internal mold dimensions were slightly oversized at about 8 ft in length, 13 in in depth, and 8 in in width to accommodate the target beam size (7 ft length × 12 in depth × 6 in width). Table 1 shows the corresponding beam dimensions. Five identical wooden formworks were constructed for the experimental beams cast and tested in this laboratory. The control beam (3-CONT-MN-2) was sourced from prior published experimental work [27]. The inner faces of all formworks were sprayed with grease to avoid water absorption during concrete casting. Figure 1 illustrates five of the prepared timber molds ready for casting the beams. To ensure proper concrete cover, small support “seats” (spacer blocks) of 0.5 in height were fixed to the reinforcement cages before casting. These supports established a clear cover of 0.5 in at the top (compression face) and 1.0 in at the bottom (tension face) of each beam. After casting, the timber forms were removed 24 h later to allow demolding, and the concrete specimens were then moist cured with wet towels for 28 days.

Table 1.

Summary of reinforcement characteristics for all beam specimens.

Figure 1.

Prepared wooden formwork for concrete beams.

2.1.2. Reinforcement

In the experiment, five beams were cast and tested in the laboratory. The sixth beam (3-CONT-MN-2) acted as the control specimen. The experimental beams had three different kinds of reinforcements: CFRP, GFRP, and steel rebar. They were used as main reinforcements and were placed at the bottom of the formwork to work in tension. Omitting stirrups was a design choice to promote diagonal shear failure in these specimens, enabling a direct study of shear behavior in the different reinforcement configurations. The control beam was reinforced with traditional steel rebar only and had no stirrups. No. 5 rebar steel was used for all six beams, where the first and last 5 inches of each rebar was bent to avoid slippage and provide better bonding between the rebar and concrete. The CFRP and GFRP grids were also cut for length of 82 inches long and 5 inches wide. Overall, the first beam was reinforced with GFRP, the second beam with CFRP, the third with a GFRP hybrid with steel, and the fourth and fifth beams were reinforced with a hybrid of CFRP and steel. For the hybrid beams, the FRP grid was placed beneath the two steel rebars, and the two materials were securely attached to each other by a narrow metallic wire. The sixth beam acted as the control beam. The beams were named according to the reinforcement type and shear span-to-depth ratio (a/d). For example, CFRP_MN_2 indicates a CFRP-reinforced beam with a shear span-to-depth ratio of 2.0. Table 1 summarizes the reinforcement characteristics of all the beam specimens.

2.1.3. High-Strength Concrete

All beams were cast using HSC with a target 28-day compressive strength of approximately 9000 psi. This concrete mix was provided by a local ready-mix supplier (Central Pre-Mix, Pullman, WA, USA) and was delivered to the laboratory in a transit mixer truck. The mix design incorporated ordinary Portland cement blended with fly ash, fine silica sand, a high-range water-reducing admixture, and a small volume of steel or organic fibers to enhance ductility. A high-range water reducer (superplasticizer) was included to obtain the required flowability at a low water-to-cement ratio. Moreover, small fibers (steel or organic) were added to the mix; these fibers resulted in hardened concrete having improved toughness and post-crack load capacity. The resulting concrete can sustain flexural and tensile loads even after initial cracking due to ductility obtained. By using a single ready-mixed supply, material consistency was maintained across all beam specimens. Prior to casting, the fresh concrete exhibited a workable consistency under the action of the superplasticizer; however, to further ensure full compaction around the dense reinforcement (especially in the hybrid beams), vibration was applied during pouring. Table 2 below presents the material properties of this HSC mix obtained from the manufacturer.

Table 2.

Properties of High-Strength Concrete.

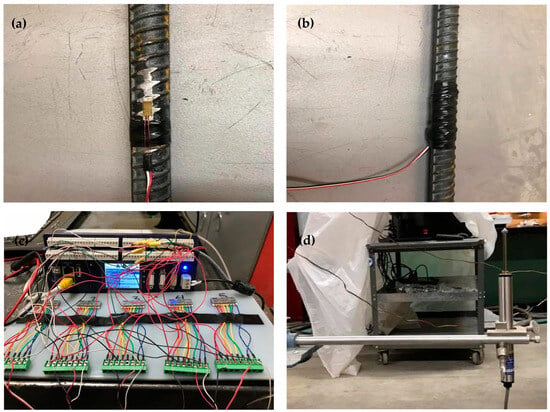

2.1.4. Strain Gauges

In each beam, two strain gauges were mounted on each main longitudinal reinforcing element. It is to capture and monitor strain at critical locations under the load applied. The gauges were positioned symmetrically on at approximately 31 inches from the midpoint of the reinforcement. This placement puts the gauges in the constant moment region just inside the loading points of the four-point bending setup, where the highest tensile strains occur in the reinforcement. With these locations marked, the rebar surface at these points were first ground smooth with an electric grinder and cleaned with a baking soda water solution to remove any grease or oxidation. After the surface dried, a super glue instant-set epoxy adhesive was applied with a syringe, and the strain gauge was bonded onto the cleaned rebar surface. The adhesive was allowed to dry (approximately 10 min), and then electrical tape was applied under the exposed lead wires. Figure 2a shows the strain gauge with tape under lead wire. The entire gauge area was then wrapped with additional electrical tape, and a thin layer of epoxy coating was added over the tape for waterproofing and mechanical protection during concrete pouring. This procedure was repeated for each gauge for each beam. The careful installation ensured reliable strain readings without damage from the wet concrete. A total of four strain gauge channels were provided on each beam (two per main bar, left and right of midpoint of rebar) to record the internal strain response during testing. Figure 2b shows the strain gauge with complete attachment.

Figure 2.

(a) Strain gauge with tape under lead wire; (b) strain gauge with complete attachment; (c) Expert Data Logger connection to strain gauges and LVDT; (d) LVDT attached to Expert Data Logger under each beam specimen.

2.1.5. Data Acquisition System

An Expert Data Logger unit capable of high-speed synchronized sampling on up to 46 analog channels was employed to record signals from the strain gauges and displacement transducers. All strain gauges installed on the beams were wired to this data logger via plug-in screw terminal connections, along with the linear variable displacement transducers (LVDTs) used to measure deflections. The LVDT used in this setup is a high-precision Linear Variable Differential Transformer device, which converts linear motion into a proportional electrical signal. In these experiments, a single LVDT was positioned at the bottom midspan of each beam to measure its vertical deflection under load. The LVDT’s output was fed into the data logger, enabling the capture of the deflection–time history throughout the loading process. Similarly, the strain gauge readings (changes in electrical resistance) were sampled and logged as load was applied. The data logger operated at a suitable sampling rate to accurately capture the behavior of the beam up to failure, and the collected data were saved for subsequent analysis. The data logger was interfaced with a laptop computer for control and real-time data storage. Prior to the tests, the data acquisition system was calibrated and configured through the computer to ensure each channel corresponded to the correct gauge or transducer. During each beam test, the system continuously monitored and recorded the strains and deflections. Figure 2c shows the Expert data logger connection to strain gauge and LVDT. Figure 2d shows the LVDT attached to Expert Data Logger under each beam specimen.

2.2. Design and Details of the Tested Beam Specimens

Six reinforced concrete beam specimens were designed and fabricated, each with identical overall dimensions and support conditions, but with different reinforcement configurations. The beams measured 7 ft (2134 mm) in total length and had a rectangular cross-section 12 in deep by 6 in wide (305 mm by 152 mm). All beams were simply supported and were intended to fail in shear (diagonal tension) rather than flexure. To ensure this, no transverse reinforcement (stirrups) was provided in any of the specimens, making the shear capacity primarily dependent on the concrete and the novel reinforcement (steel/FRP/hybrid). The longitudinal reinforcement scheme was the primary variable among the beams. Table 3 summarizes the key characteristics of each test specimen, including the reinforcement type, reinforcement amount, and shear span-to-depth (a/d) ratio in the four-point loading configuration. All beams were designed with the same span (supported length of 6.16 ft). The beam ICONT-MN-2 in Table 3 is the control beam containing only traditional steel reinforcement.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the concrete beams.

Reinforcement configurations: Two of the beams were reinforced only with FRP grid (one with a CFRP grid and one with a GFRP grid) as the flexural reinforcement, with no traditional steel bars. These are referred to as the CFRP-only and GFRP-only beams, respectively. The remaining three beams were hybrid-reinforced, containing a combination of steel rebars and FRP grid in the tension zone. Among the hybrid beams, one specimen had a GFRP grid with steel reinforcement hybrid, and two specimens had CFRP grid with steel reinforcement hybrid. In all hybrid cases, the longitudinal reinforcement consisted of a single strip of FRP grid layered beneath two #5 steel bars, effectively with the steel contributing ductility and the FRP providing additional tensile capacity and crack control. All beams had the same nominal concrete cover to reinforcement (0.5 in top, 1 in bottom). The steel bars in all beams were bent at their ends to form hooks, preventing slippage and ensuring the failure would occur in the span rather than at the supports.

Shear span-to-depth ratio: Five of the beams were tested with a shear span-to-depth ratio(a/d) of 2.0, which is a short shear span condition promoting diagonal shear failure. The third beam in Table 3 (with CFRP and steel hybrid) was tested with a larger a/d ratio of 2.5. The motivation for this variant was to examine the influence of slightly distributed loading on the shear behavior, particularly for the hybrid CFRP/steel reinforcement. Thus, across the six specimens, the experimental program encompassed five reinforcement schemes (steel-only, CFRP-only, GFRP-only, CFRP with steel hybrid, GFRP with steel hybrid), and two shear span ratios (2.0 in most beams, 2.5 in one beam). This matrix allows evaluation of how the presence of steel vs. FRP reinforcement, and the shear span length affects the shear capacity and failure mode of HSC beams.

2.3. Casting of the Test Beams

The five beams were cast in one session using the delivered batch of high-strength concrete. The casting took place in the structures laboratory at the University of Idaho using the prepared wooden molds described earlier (Figure 1). The ready-mix concrete truck discharged the HSC into wheelbarrows, and the concrete was transported in small batches into the lab and poured into each formwork. For each beam, the concrete placement was performed in layers to ensure even distribution around the dense reinforcement. Shovels and scoops were used to place and consolidate the concrete within the form, especially around the cage of steel and FRP. An internal vibrator was applied during and after pouring each layer to eliminate air entrainment and help the stiff HSC mix flow around the reinforcement. The vibrator was inserted at multiple points along the beam length for thorough compaction.

After each form was filled, the excess concrete was struck off, and the top surface was finished and leveled with a trowel. Care was taken to produce a smooth, flat top surface, as this would later be the compression face of the beam under testing. At this stage, clamps were attached to the sides of the wooden formwork as shown in the figure. These clamps prevented any buckling of formwork due to pressure from the fresh concrete, thereby preserving the correct beam width along the full length. The clamps also helped maintain alignment of the form until the concrete set. The beams remained undisturbed in their molds for the initial 24 h after casting to allow the concrete to set. Thereafter, the wooden molds were carefully stripped off. Immediately after formwork removal, the beams were covered with wet burlap/towels to moist-cure the concrete for 28 days. Figure 3 shows the arrangement of FRP and conventional steel reinforcement within the formwork, followed by the casting of concrete beam in progress.

Figure 3.

(a) Integrated arrangement of FRP and Conventional Steel Reinforcement within the formwork. (b) Casted concrete beams with clamps.

2.4. Test Setup and Instrumentation

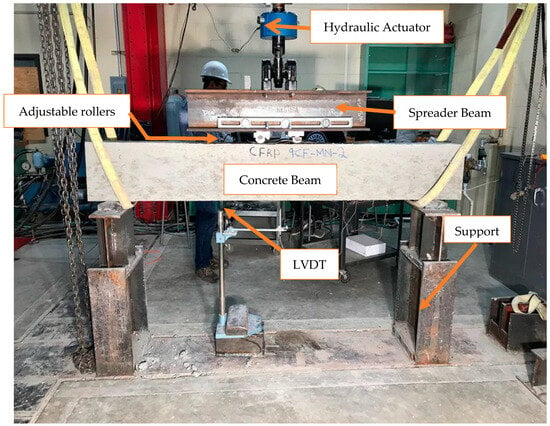

All beams were tested under a four-point bending configuration to induce shear-critical loading. The testing was conducted in a servo-valve hydraulic single ended fatigue-rated actuator mounted overhead. Each beam was simply supported on a pair of steel supports and loaded at two symmetric points located in the span to create a region of constant moment in the middle of the beam. The span length (center-to-center distance between supports) was 6.16 ft (1.88 m). The load from the actuator was introduced through a stiff spreader beam (load distribution beam) bolted to the actuator’s loading ram. This spreader beam had two adjustable knife-edge supports attached to its underside, spaced to match the desired loading points on the specimen. When the actuator pushed downward on the spreader, it transmitted equal concentrated loads into the beam at the two loading points. The beam, in turn, was supported at its ends by two steel roller supports. The supports were positioned so that the beam sat 36 in (0.91 m) above the laboratory floor. This elevation provided clearance to mount instrumentation such as the LVDT at midspan. Physical test setup, including the actuator, spreader beam, and roller supports, is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Experimental test setup of the concrete beams.

The load was applied under displacement control to capture the complete response of the beams up to failure. The actuator was driven at a constant stroke rate corresponding to approximately 1 mm/min at the loading points. This slow monotonic loading allowed the beams to undergo gradual crack development and for data to be recorded at a fine time resolution. The tests continued until a clear shear failure occurred or until the beam could no longer sustain additional load. The result is a comprehensive set of measurements: load–deflection curves, load–strain responses, and ultimately the shear capacity and failure mode for each beam. During testing, visual observations were made and recorded to complement the instrumented data. The formation of cracks was carefully monitored; crack initiation and propagation were marked on the beam surface with a pen. In particular, the first appearance of flexural cracks in the constant moment region and subsequent diagonal shear crack development in the shear spans were noted.

3. Theoretical Method

This section presents an integrated theoretical framework for analyzing the flexural and shear behavior of high-strength concrete (HSC) beams reinforced with steel and FRP grids. The analytical procedures are grounded in classical reinforced concrete mechanics and relevant international design standards, with particular reference to ACI 318-16 [28]. The framework incorporates the evaluation of energy absorption capacity, flexural moment capacity, shear strength, and maximum load. In addition, the load–deflection response is examined through midspan deflection analysis, including the calculation of effective moment of inertia and deflections under applied loading.

3.1. Energy Absorption

The ability of a beam to sustain deformations without failure reflects its ductility and energy absorption characteristics. In this study, energy absorption is considered a key performance indicator and is quantified by evaluating the area under the load–deflection curve. This area represents the mechanical work performed on the specimen and is expressed as an integral:

where U denotes the total energy absorbed up to failure, P represents the applied load, and Δ is the midspan deflection. This integration is performed numerically using experimental data obtained during flexural testing. The integral serves as a fundamental measure of a beam’s toughness, capturing not only its load-bearing capacity but also its deformation resilience prior to fracture. The theoretical formulation presented above is directly evaluated using the experimental results obtained from four-point bending tests.

3.2. Moment Capacity

Moment capacity is the ability of an applied force that causes a twisting or turning effect about an axis to a concrete beam. To find the theoretical ultimate moment, the Canadian Educational Module Code [29] of fiber reinforcement provides Equation (2) to estimate the moment capacity of beams reinforced with FRP, while ACI 318-16 Equation (3) predicts moment capacity of conventional beam reinforced with conventional steel bars.

where Mu(frp) is the ultimate moment resisted by the FRP bars, Mu(steel) is the ultimate moment resisted by the steel reinforcement, φfrp is the material resistance factor for FRP, φsteel is the material resistance factor for steel reinforcement, Afrp is the area of FRP reinforcement, Asteel is the area of steel reinforcement, ffrp(u) is the ultimate tensile strength of FRP, fsteel(u) is the ultimate tensile strength of steel reinforcement, d is the effective depth of the beam, β is stress—block parameter for concrete at a strain less than ultimate, and c is depth of neutral axis.

To estimate the ultimate moment of hybrid (steel with FRP)-reinforced concrete beams, Equation (4) was used. Table 3 and Table 4 show the details of the strength reduction factors and the mechanical properties that were used in the calculations. Table 5 shows the mechanical properties of the beam specimens.

Table 4.

Material Resistance Factor.

Table 5.

Mechanical Properties of Beam specimen.

To calculate the reinforcement area of hybrid beams, the steel and FRP areas are first determined separately and then summed. CFRP and GFRP areas are estimated using the Canadian Educational Module Code for FRP. The results are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Area of the reinforcements.

The tensile stress resultant, T can be calculated directly using Canadian Educational Module Code Equation (5):

The compressive stress resultant, C could be obtained using the following Canadian Educational Module Code Equation (6):

To calculate the depth of neutral axis, c, simply divide tensile stress over compressive stress, using Canadian Educational Module Code Equation (7):

Furthermore, based on the experimental applied maximum load, actual moment capacity can be calculated, using Canadian Educational Module Code Equation (8):

where is the experimental moment capacity, is the experimental maximum applied load, and a is the shear span for each beam.

3.3. Shear Strength

Shear strength is the resistance of materials or components against the type of yield or structural failure where their materials or components fail in shear. The shear capacity of reinforced concrete beams is developed through the combined action of concrete and transverse reinforcement. According to Canadian Education Module Code Equation (9), the total shear strength of beam specimen is as follows:

where V is the shear strength of the beam, is the shear strength provided by the concrete, and is the shear strength provided by the stirrups.

In the present study, all specimens were cast without transverse shear reinforcement. Therefore, the entire shear capacity is assumed to be provided by the concrete web alone. As a result, the contribution from stirrups is neglected ( = 0), and Equation (9) simplifies to the following:

To evaluate the experimental and theoretical shear strength, the following ACI equations were employed:

where is the maximum applied load by the actuator that caused the reinforced concrete beam to fail in shear. The corresponding predicted maximum load is calculated using Equation (13) from the Canadian Educational Module Code:

where is the ultimate moment of the beam and a is the shear span.

3.4. Deflection

Deflection refers to the displacement of a reinforced concrete beam from its original position under the action of external loads. It is a key serviceability parameter that reflects the beam’s deformation response to applied forces. In this study, static loading was applied to each specimen, and deflection was recorded using a Linear Variable Differential Transformer (LVDT). In order to calculate the experimental maximum deflection in each concrete beam, the following Equation (14) from Canadian Educational Module Code is used:

where is the maximum midspan deflection of specimen, P is the maximum applied load, a is the shear span, is the effective modulus of elasticity of concrete, is the effective moment of inertia, and l is the total span length. The modulus of elasticity of concrete, Ec, was determined using Equation (15) from ACI provisions:

3.5. Effective Moment of Inertia

The moment of inertia is a geometrical property of a beam that reflects its ability to resist bending; the larger the moment of inertia the less the beam will bend. For FRP-reinforced beams, the effective moment of inertia (Ie) accounts for stiffness degradation due to cracking. As per the Canadian Educational Module Code [29], Ie is calculated using the following:

where is the uncracked (transformed) section inertia, is the cracked section inertia (ignoring tensioned concrete), is the cracking moment of cross-section, and maximum moment in a member of at the load stage at which deflection is being calculated.

The cracked section inertia is computed using the following:

where k is the neutral axis depth ratio and is the modular ratio. The modular ratio and neutral axis factor are evaluated as follows:

The value of the cracking moment, Mcr, is calculated as follows:

where is the modulus of rupture and is the distance from the extreme fiber in tension to the neutral axis, taken as for symmetric rectangular sections, where h is the total height of the section. The modulus of rupture, is derived as follows:

for FRP-reinforced beams.

for steel-reinforced beams.

3.6. Cracking Moment

Cracking in the beams is a critical indicator of structural behavior, marking the transition from uncracked to cracked flexural response. To assess this behavior, both analytical and experimental cracking moments were evaluated. These values were calculated using Equations (23) and (24) from the Canadian Educational Module Code, as outlined below:

4. Experimental Results and Discussion

The experimental program involved six beams reinforced with conventional steel bars and hybrid CFRP–steel and GFRP–steel systems, tested under four-point monotonic loading to evaluate load–deflection response, load–strain behavior, ultimate load capacity, and failure modes. The experimental results presented in the following sections are directly compared with analytical predictions based on the Canadian Educational Module Code [29] to assess the applicability of its design equations for HSC beams reinforced with hybrid systems.

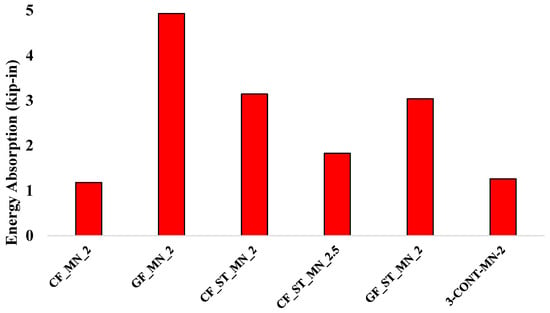

4.1. Energy Absorption Capacity

Figure 5 illustrates the energy absorption capacities of the six tested beam specimens, calculated as the area under their respective load–displacement curves. These values were determined using Equation (1) by integrating the experimental load–displacement response up to failure to quantify the total energy dissipation of each specimen.

Figure 5.

Energy absorption capacity of the concrete beam specimens.

Among the specimens, the GFRP-only reinforced beam (GF_MN_2) exhibited the highest energy absorption at 4.93 kip-in, despite its relatively low peak load capacity. This behavior indicates that the specimen experienced gradual crack propagation, facilitating distributed damage and extended energy dissipation before failure. In hybrid configurations, the CF_ST_MN_2 specimen recorded an energy absorption of 3.15 kip-in, while the GF_ST_MN_2 specimen reached 3.04 kip-in, underscoring the benefits of integrating FRP grids with steel reinforcement. These hybrid systems utilize the high tensile strength of FRP in conjunction with the ductility of steel, resulting in improved post-yield deformation capacity and delayed collapse under loading. Conversely, the CF_ST_MN_2.5 specimen, with a higher shear span-to-depth ratio (a/d = 2.5), demonstrated a lower energy absorption of 1.83 kip-in, suggesting that the increased shear span may have shifted the failure mode toward a more brittle shear-dominated response with reduced energy dissipation capacity. The CFRP-only reinforced beam (CF_MN_2) exhibited the lowest energy absorption at 1.18 kip-in, reaffirming the limited ductility and brittle behavior characteristic of FRP-only systems under shear-dominant conditions. The steel-reinforced control beam (3-CONT-MN-2) recorded an energy absorption of 1.26 kip-in, serving as a reference for the comparative performance of the other specimens.

FRP-reinforced and hybrid steel-FRP concrete beams can exhibit effective energy dissipation under shear-dominant conditions due to distributed cracking and delayed failure mechanisms that allow gradual energy absorption even with lower peak loads compared to steel-reinforced beams. Gao and Zhang [30] and Ali et al. [16] highlighted that these mechanisms contribute to improved post-cracking energy absorption and enhance the structural resilience of high-strength concrete members. These insights emphasize the value of hybrid reinforcement systems in maintaining energy dissipation capacity while improving ductility in shear-critical applications.

Collectively, the results highlight that hybrid reinforcement systems, particularly those combining steel and FRP, enhance energy dissipation by balancing tensile strength with ductility. Such systems contribute to improved structural resilience in high-strength concrete beams by promoting stable and ductile post-cracking behavior, which is essential for ensuring adequate toughness and reducing the risk of sudden catastrophic failures.

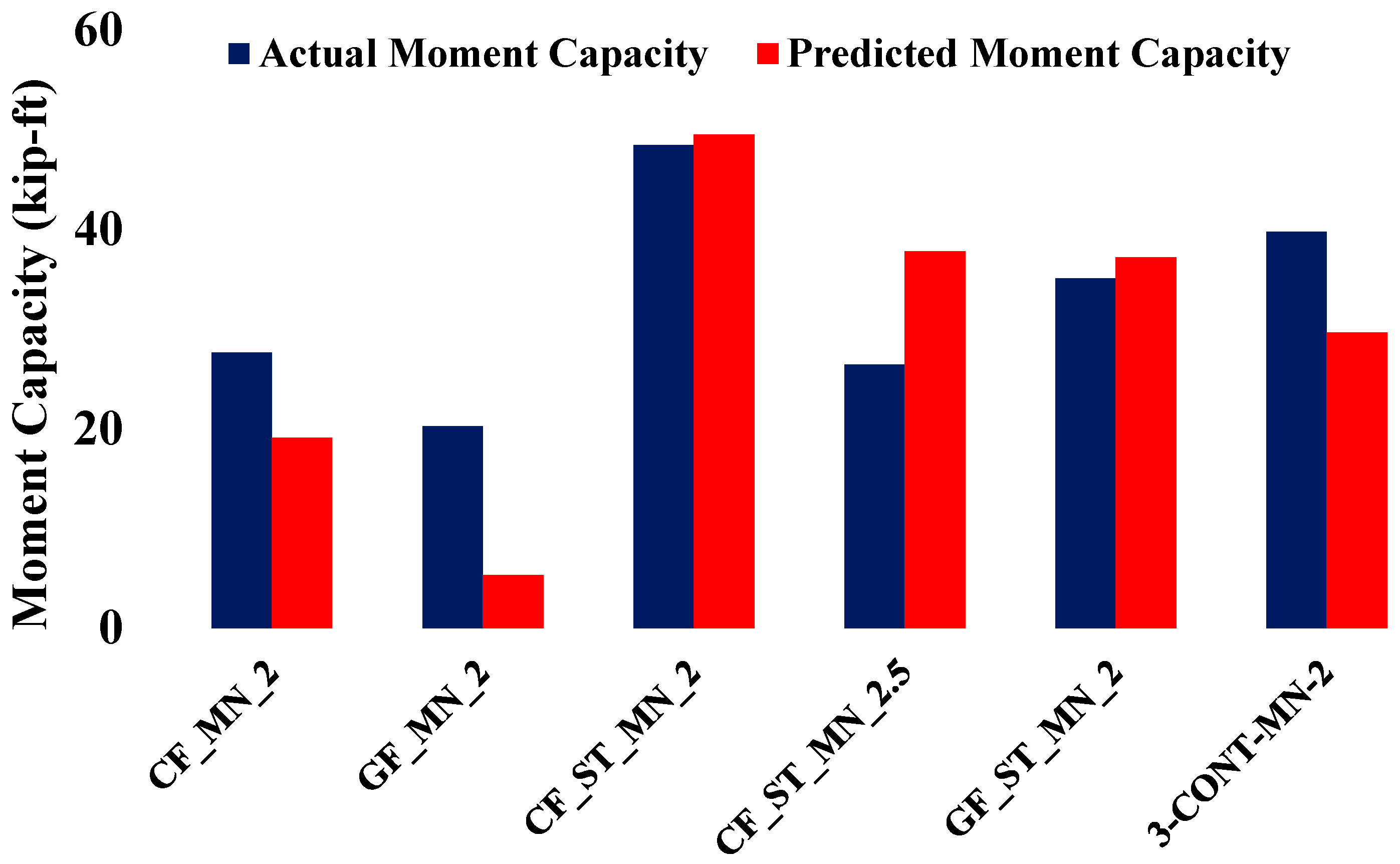

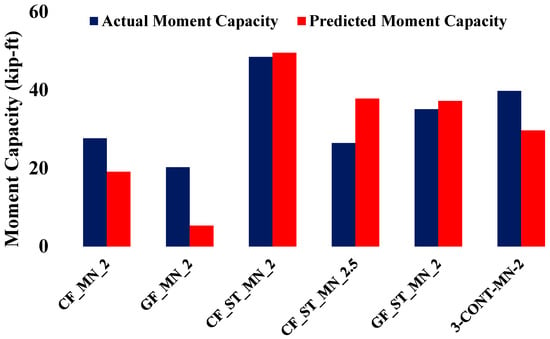

4.2. Moment Capacity Comparison

The comparison of moment capacity is presented to confirm that flexural capacity was not governing and that all specimens failed in a shear-critical manner. Figure 6 presents a comparison between the experimental and theoretical moment capacities of the tested beam specimens, with theoretical values computed using Equations (2)–(4). The steel-reinforced control beam (3-CONT-MN-2) achieved an experimental moment capacity of 39.80 kip-ft, exceeding its predicted value of 29.67 kip-ft by approximately 34%. This increase can be attributed to factors such as tension stiffening of concrete between cracks and confinement effects provided by the beam geometry, which are not fully represented in simplified predictive models.

Figure 6.

Comparison of Actual and Predicted Moment Capacities.

For beams reinforced solely with fiber grids, larger discrepancies between predicted and measured capacities were observed. The CFRP-reinforced specimen (CF_MN_2) recorded an experimental moment capacity of 27.66 kip-ft, which is approximately 45% higher than its predicted capacity of 19.10 kip-ft. The GFRP-reinforced specimen (GF_MN_2) exhibited an even greater deviation, with an experimental capacity of 20.26 kip-ft compared to a predicted value of 5.32 kip-ft, representing an increase of 280%. These significant differences underscore the limitations of traditional analytical models in capturing the nonlinear stress transfer and brittle post-cracking behavior associated with FRP-reinforced concrete beams. In contrast, hybrid reinforcement systems demonstrated closer alignment between predicted and experimental values. The CF_ST_MN_2 specimen achieved an experimental moment capacity of 48.48 kip-ft, closely matching its predicted value of 49.56 kip-ft, confirming the accuracy of the predictive model when steel reinforcement governs the flexural response. The CF_ST_MN_2.5 specimen; however, recorded an experimental capacity of 26.45 kip-ft, which is approximately 30% lower than its predicted value of 37.80 kip-ft, indicating that a higher shear span-to-depth ratio in combination with hybrid reinforcement may lead to stress redistribution or premature cracking not fully captured by the analytical model. The GF_ST_MN_2 specimen showed a modest deviation of approximately 6%, with an experimental moment capacity of 35.11 kip-ft compared to a predicted value of 37.21 kip-ft, reflecting consistent behavior under hybrid reinforcement.

Conventional design models often underestimate the moment capacities of FRP-reinforced concrete beams because they do not account for post-cracking mechanisms and tension stiffening effects that contribute to higher capacity in practice. Mukhtar and Deifalla [11] compiled extensive experimental data demonstrating that FRP-reinforced systems can achieve higher moment capacities than predicted due to these unaccounted mechanisms. They also showed that when steel is combined with FRP in hybrid reinforcement systems, the predicted and measured moment capacities align closely, reflecting the stabilizing influence of steel while retaining the tensile benefits of FRP.

Overall, while existing predictive models perform reliably for steel-dominated or hybrid systems where ductility and strain redistribution are present, they remain inadequate for accurately predicting the behavior of FRP-only reinforced beams. The observed deviations emphasize the need to refine analytical models for FRP applications to account for the effects of bond characteristics, tension stiffening, and brittle fracture propagation in order to improve the accuracy of flexural capacity predictions in future design provisions.

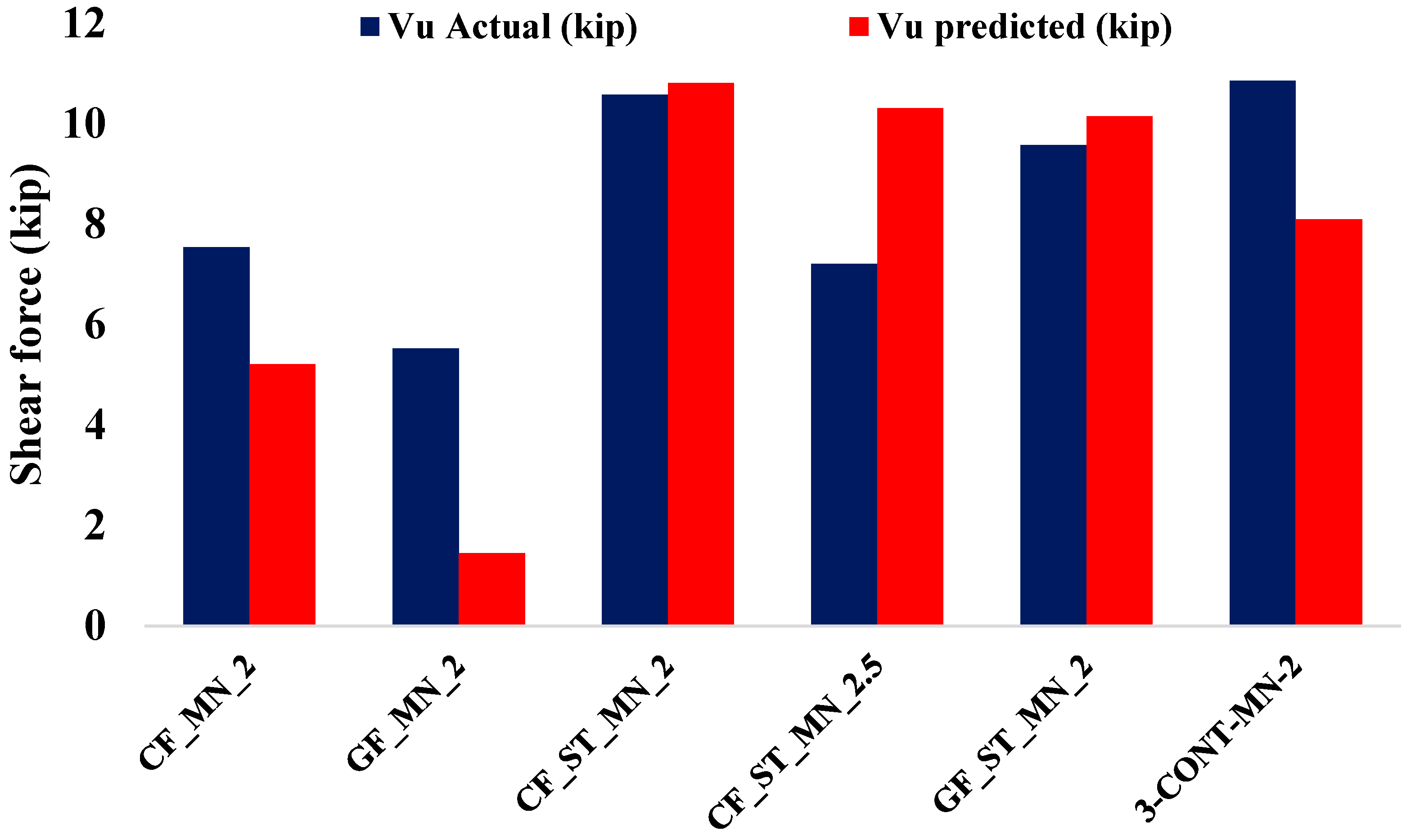

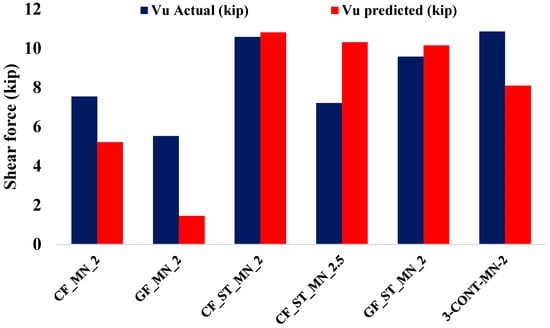

4.3. Shear Strength Comparison

Figure 7 compares the experimental and predicted shear strengths of the tested beam specimens, with theoretical values calculated using Equations (11) and (12). The hybrid beams exhibited strong agreement with analytical predictions. The CF_ST_MN_2 specimen recorded a measured shear strength of 10.58 kips, closely aligning with its predicted value of 10.81 kips, reflecting a deviation of only 2%. Similarly, the GF_ST_MN_2 specimen demonstrated a measured shear strength of 9.58 kips against a predicted value of 10.15 kips, corresponding to a deviation of approximately 6%. These results confirm the applicability of current shear models for steel-FRP hybrid systems, where the combined action of steel dowel effects and FRP grid continuity contributes to reliable shear resistance. In contrast, the CF_ST_MN_2.5 specimen exhibited an experimental shear strength of 7.21 kips, which is approximately 30% lower than its predicted value of 10.31 kips. This discrepancy suggests that at higher shear span-to-depth ratios, hybrid systems may experience wider and deeper diagonal cracking, which can compromise the shear-carrying contributions of the steel-FRP combination, a behavior not fully captured by simplified predictive models.

Figure 7.

Comparison of predicted and actual shear strength load for the beam specimen.

For the FRP-only specimens, the differences between predicted and measured shear strengths were substantial. The GF_MN_2 specimen demonstrated an experimental shear strength of 5.53 kips compared to a predicted value of 1.45 kips, indicating an underestimation of nearly 280%. Similarly, the CF_MN_2 specimen achieved a measured shear strength of 7.54 kips against a predicted value of 5.21 kips, exceeding the predicted value by approximately 45%. These significant discrepancies highlight the conservatism inherent in current design equations for FRP-only beams without shear reinforcement, likely due to the omission of beneficial mechanisms such as crack-bridging, aggregate interlock, and localized stress redistribution provided by FRP grids, even in the presence of brittle failure modes.

Shear strength predictions for FRP-reinforced and hybrid concrete beams are often inaccurate because conventional models do not fully account for crack-bridging and aggregate interlock effects that contribute to higher shear capacity in practice, particularly in FRP-only systems. Lower shear span-to-depth ratios further enhance shear performance by limiting diagonal crack development and promoting more effective load transfer across cracks. Recognizing and incorporating these mechanisms in predictive models is essential for accurately estimating the shear behavior of high-strength concrete beams with FRP and hybrid reinforcement under varying shear span conditions [31].

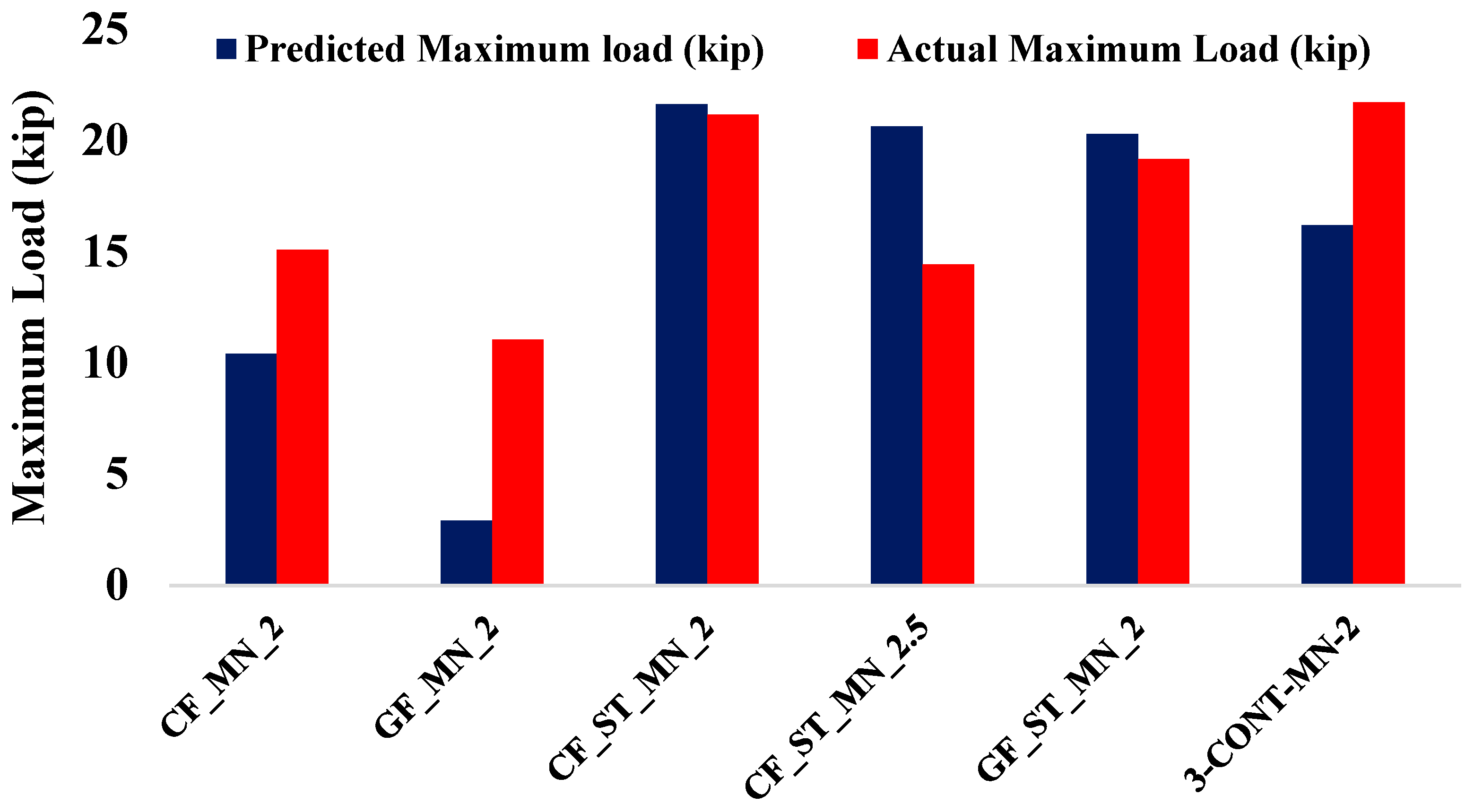

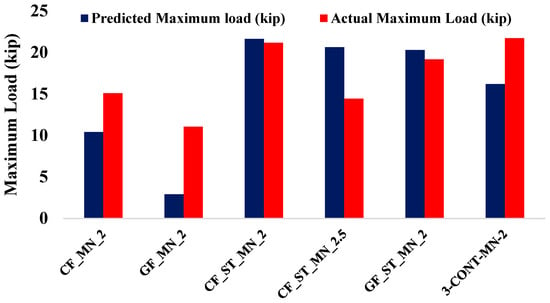

4.4. Maximum Load

Figure 8 compares the experimental and predicted maximum load capacities of the tested beam specimens, with theoretical values computed using Equation (13). The hybrid specimens exhibited strong alignment with analytical predictions. The CF_ST_MN_2 specimen reached an experimental peak load of 21.15 kips, which is within 2.2% of its predicted value of 21.63 kips. Similarly, the GF_ST_MN_2 specimen demonstrated close agreement, with an experimental load of 19.15 kips compared to a predicted value of 20.30 kips, reflecting a deviation of approximately 6%. In contrast, the CF_ST_MN_2.5 specimen showed a greater deviation, achieving a peak load of 14.43 kips against a predicted value of 20.62 kips, indicating a reduction of around 30%. These results confirm the reliability of current design expressions for hybrid reinforcement systems, where the combined contribution of steel and FRP enhances ductility and enables consistent stress redistribution, consistent with traditional design assumptions. However, at higher shear span-to-depth ratios, the effectiveness of hybrid reinforcement in fully mobilizing flexural capacity may diminish due to the development of wider shear cracks and altered stress redistribution patterns not fully captured by standard flexural models.

Figure 8.

Comparison of predicted and actual maximum load for the beam specimen.

In comparison, the FRP-only specimens exhibited more pronounced discrepancies between predicted and measured values. The CFRP-reinforced specimen (CF_MN_2) achieved an experimental peak load of 15.09 kips, which is approximately 45% higher than its predicted value of 10.42 kips. The GFRP-reinforced specimen (GF_MN_2) demonstrated an even larger deviation, reaching 11.05 kips compared to a predicted value of 2.90 kips, representing an increase of nearly 280%. These significant differences indicate that Equation (13) underestimates the load-carrying capacity of FRP grids when used without steel reinforcement, likely due to unaccounted mechanisms such as bond–slip behavior, localized crack-bridging, and progressive energy dissipation through FRP rupture during loading. From a structural engineering perspective, these findings suggest that current predictive models require refinement to more accurately represent the nonlinear and brittle behavior of FRP-only reinforcements in high-strength concrete beams.

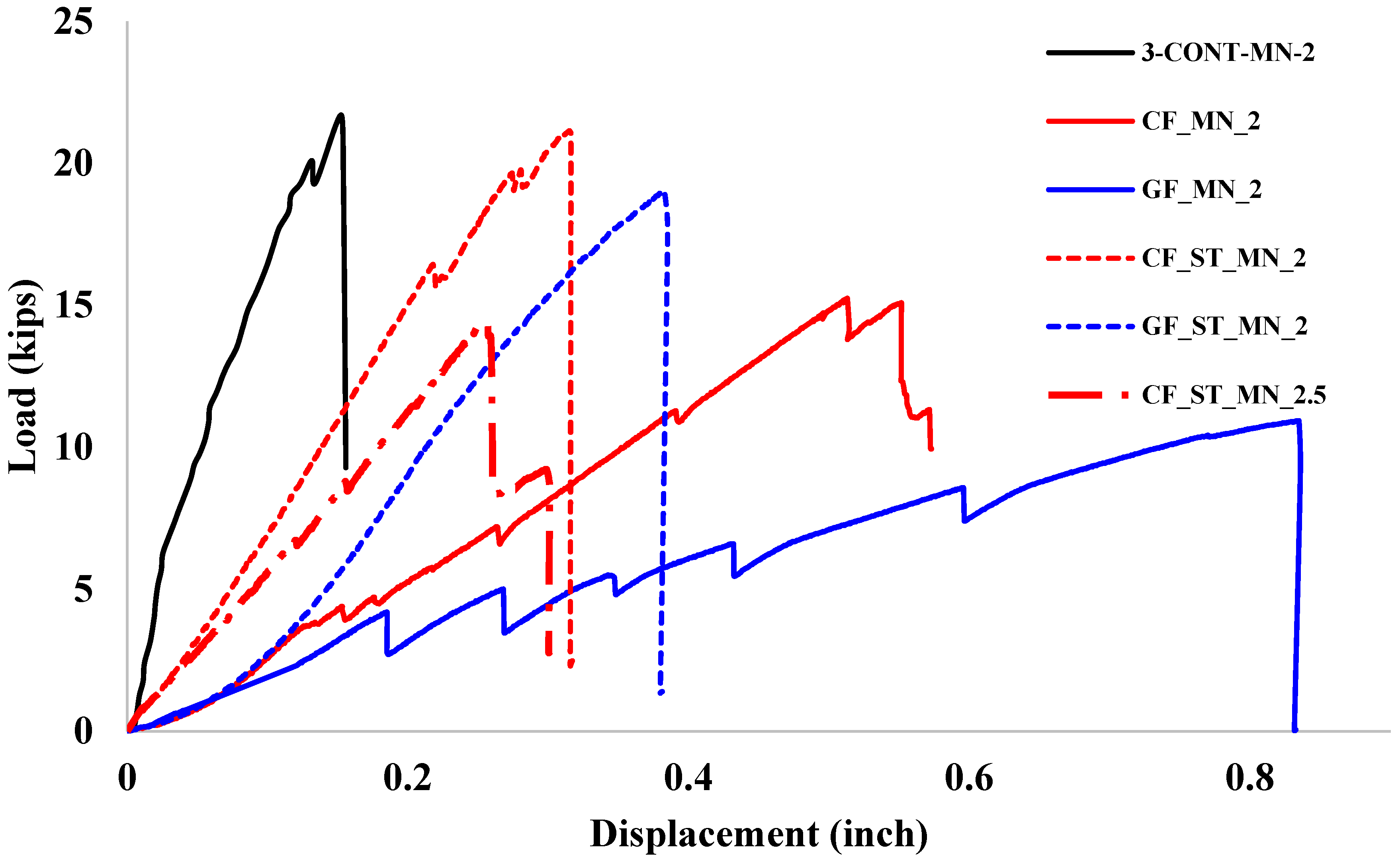

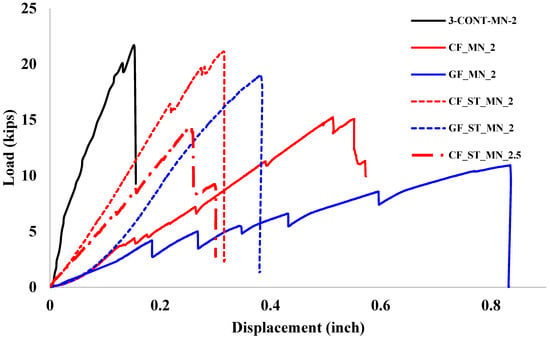

4.5. Load–Deflection Response

Figure 9 presents the comparative load–displacement curves of the six tested beam specimens, which include a conventional steel-reinforced concrete control beam (3-CONT-MN-2), beams reinforced solely with fiber grids (CFRP and GFRP), and hybrid beams integrating fiber grids with conventional steel reinforcement. Shear reinforcement was deliberately omitted in all specimens to isolate and evaluate the contribution of longitudinal reinforcement under shear-dominant loading. These results collectively illustrate the influence of reinforcement type and shear span-to-depth ratio (a/d) on peak load capacity and deformation behavior. The steel-reinforced control beam (3-CONT-MN-2) with an a/d ratio of 2 achieved a peak load of 21.71 kips, serving as a benchmark for assessing the performance of alternative reinforcement strategies.

Figure 9.

Load–Displacement Curves of Beam Specimens.

Beams reinforced exclusively with fiber grids exhibited a noticeable reduction in load-carrying capacity. The CFRP-reinforced specimen (CF_MN_2) reached a peak load of 15.25 kips, representing a 29.7% reduction relative to the control beam. The GFRP-reinforced specimen (GF_MN_2) demonstrated an even greater reduction, failing at 10.93 kips, which is 49.7% lower than the control. These findings highlight the inherent brittleness and lower tensile stiffness of fiber-reinforced systems in the absence of steel reinforcement, emphasizing the critical limitations in bond performance under shear-dominant conditions.

In contrast, hybrid reinforcement systems demonstrated a significant recovery in load capacity alongside enhanced ductility. The hybrid beam CF_ST_MN_2.5, reinforced with CFRP grids and steel at an a/d ratio of 2.5, achieved a peak load of 14.43 kips, approximately 33.5% lower than the control beam. This reduction is largely attributed to the higher shear span, which promotes a shift toward flexure-dominated behavior. Notably, the CF_ST_MN_2 specimen, with the same reinforcement type but a lower a/d ratio of 2, reached a peak load of 21.15 kips, closely matching the control beam with a marginal difference of 2.6%. The GF_ST_MN_2 specimen, incorporating GFRP grids with steel reinforcement at an a/d ratio of 2, attained a peak load of 19.01 kips, corresponding to 87.6% of the control beam’s capacity, and exhibited improved post-peak ductility.

Hybrid reinforcement strategies in reinforced concrete beams effectively balance strength and ductility while reducing the brittleness associated with FRP-only systems. This is achieved by combining the ductility and crack-bridging capabilities of steel with the tensile strength of GFRP, allowing hybrid systems to maintain high load capacities with improved deformation performance. Almahmood et al. [10] demonstrated that while GFRP-only beams exhibited lower peak load capacity and more brittle behavior under static loading without transverse reinforcement, hybrid steel-GFRP beams retained approximately 90% of the peak load capacity of steel-reinforced beams while achieving enhanced ductility and reduced crack widths, illustrating the benefits of hybrid reinforcement under flexural loading.

Overall, the results underscore the structural benefits of hybrid reinforcement systems in enhancing both strength and ductility in high-strength concrete beams. The integration of steel reinforcement with fiber composites effectively mitigates the brittleness and stiffness limitations associated with fiber-only systems, offering a viable strategy for improving the shear and flexural performance of concrete beams under service and ultimate load conditions.

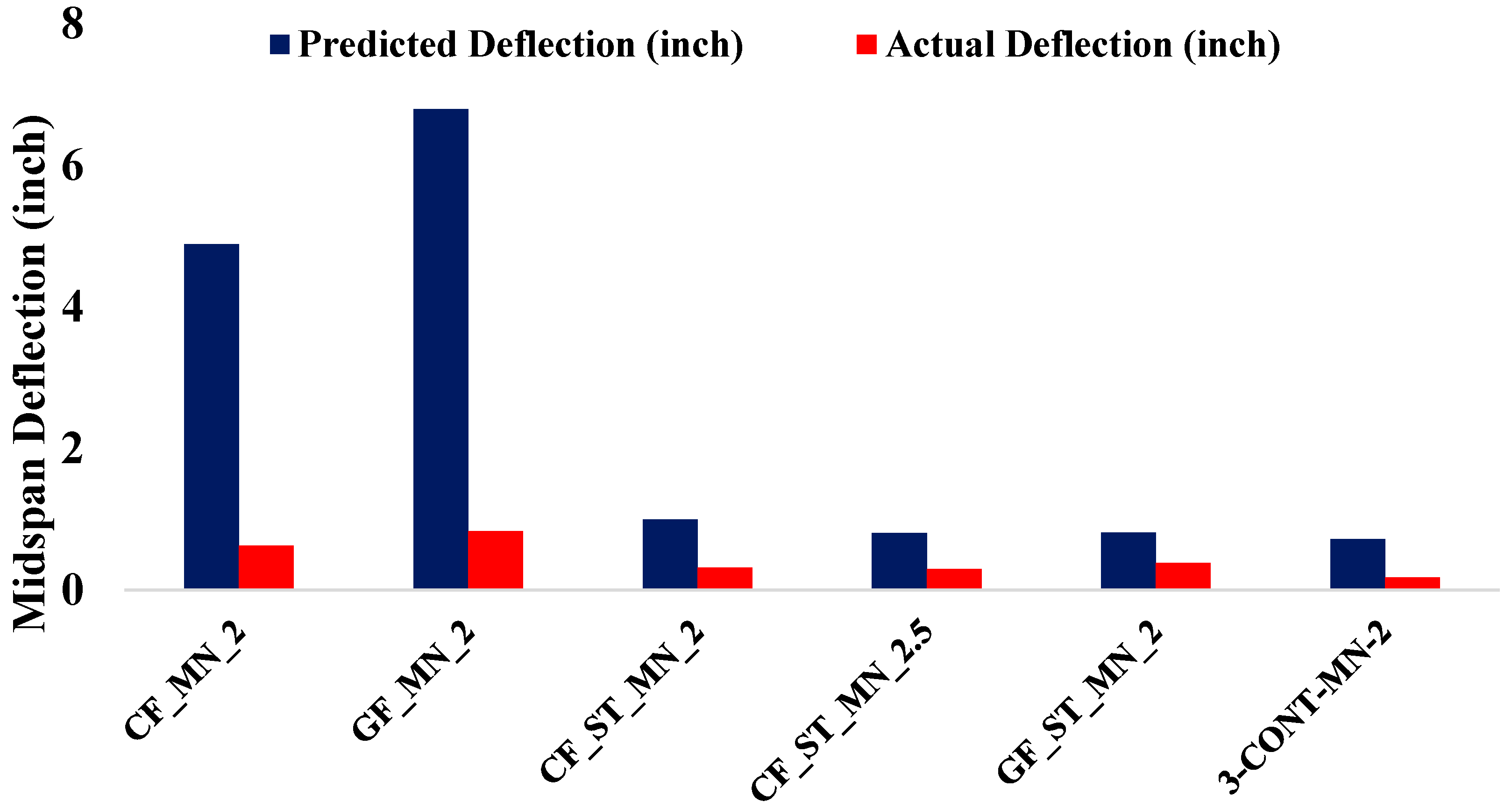

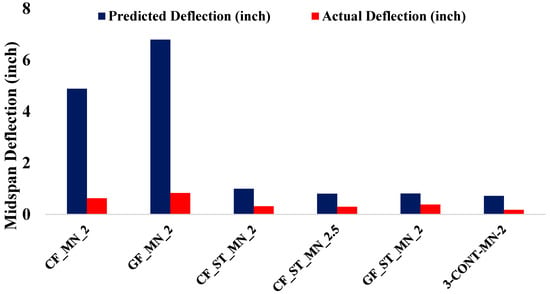

4.6. Midspan Deflection

Figure 10 presents the computed and measured midspan deflections of the tested beam specimens, with theoretical values determined using Equation (14). Substantial overpredictions were observed across all specimens, particularly for the FRP-only reinforced beams. For instance, the CF_MN_2 specimen was predicted to exhibit a deflection of 4.89 inches, whereas the measured deflection was only 0.63 inches. Similarly, the GF_MN_2 specimen showed a predicted deflection of 6.79 inches compared to a measured value of 0.84 inches. These overpredictions, by factors ranging from 7 to 8, indicate that the analytical models neglect critical mechanisms such as tension stiffening of the cracked concrete, bond–slip behavior at the reinforcement-concrete interface, and aggregate interlock, all of which contribute to limiting deflections even after cracking.

Figure 10.

Comparison of predicted and actual midspan deflection for the beam specimen.

While the hybrid specimens demonstrated smaller discrepancies, the trend of overprediction remained evident. The CF_ST_MN_2 specimen recorded a measured deflection of 0.32 inches compared to a predicted value of 0.99 inches. Similarly, the CF_ST_MN_2.5 specimen exhibited a measured deflection of 0.30 inches against a predicted value of 0.81 inches, and the GF_ST_MN_2 specimen measured 0.38 inches compared to a predicted 0.81 inches. The steel-reinforced control beam (3-CONT-MN-2) also demonstrated this trend, with a measured deflection of 0.18 inches compared to a predicted value of 0.72 inches, further illustrating the conservatism of existing predictive models. The results suggest that current serviceability models are overly conservative when applied to high-strength concrete beams reinforced with FRP or hybrid systems. The models fail to capture essential mechanisms such as the tension stiffening provided by partially cracked sections, effective bond characteristics between reinforcement and concrete, and stress redistribution following cracking. These observations underscore the need for refining existing predictive models to explicitly account for these mechanisms, thereby improving the accuracy of deflection predictions in FRP- and hybrid-reinforced high-strength concrete beams under service load conditions.

Analytical models often overestimate deflections in FRP-reinforced and hybrid concrete beams because they do not adequately consider the effects of tension stiffening, bond–slip behavior, and aggregate interlock, which contribute to reducing deflections even after cracking. These mechanisms enable hybrid systems to retain higher stiffness under service loads, while FRP’s tensile strength aids in limiting deformation, resulting in measured deflections significantly lower than those predicted by conventional models. Addressing these factors in serviceability models is essential for accurate deflection estimation in high-strength concrete members reinforced with FRP and hybrid systems [10].

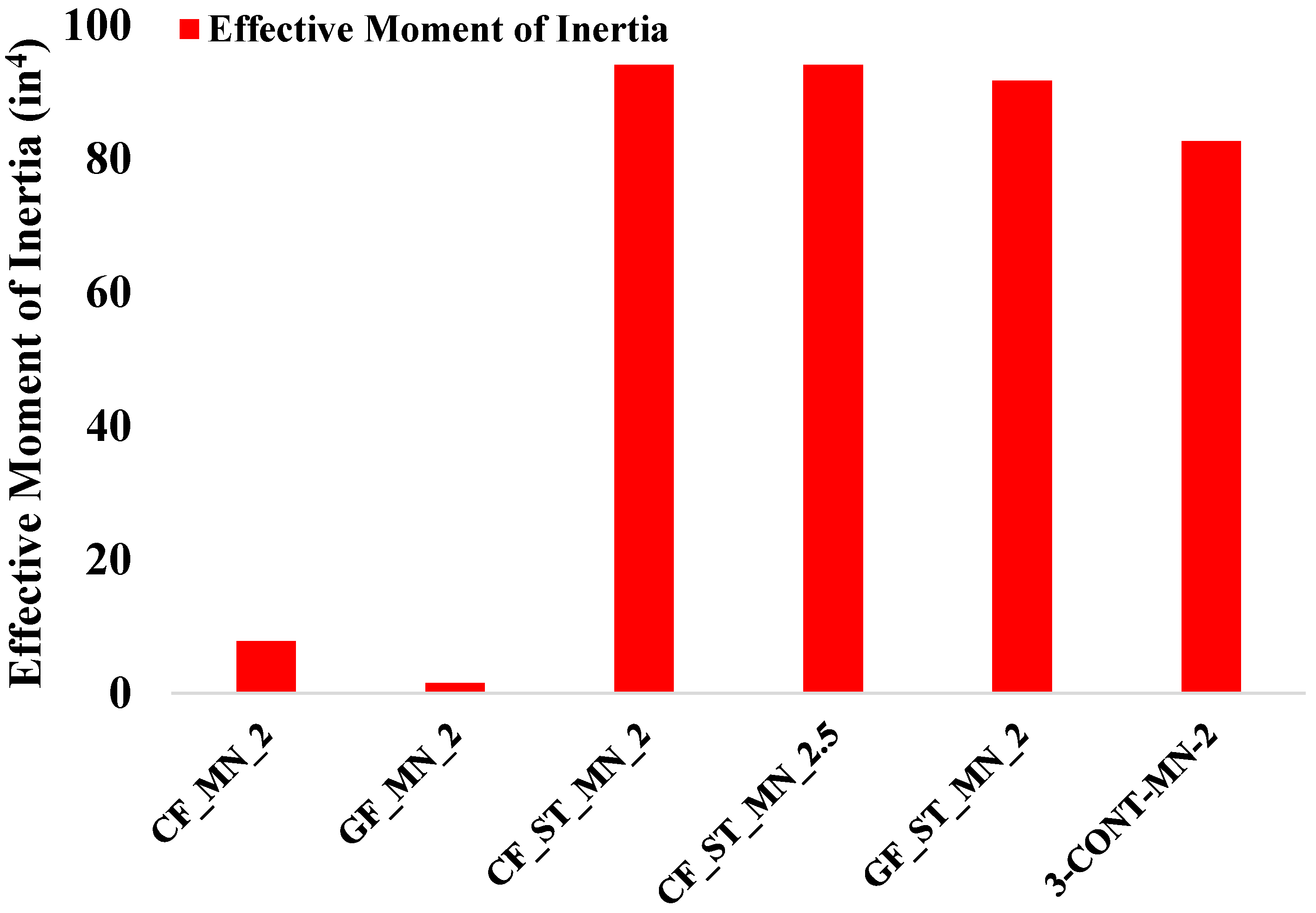

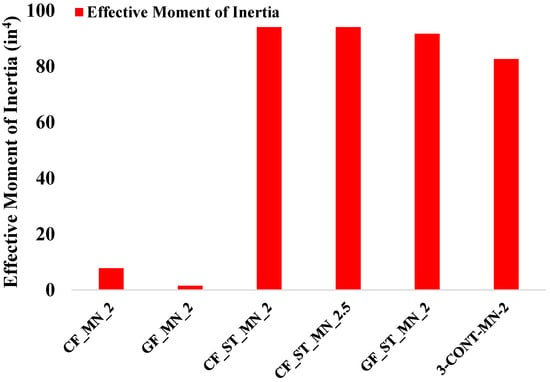

4.7. Effective Moment of Inertia

Figure 11 presents the effective moment of inertia (Ie) for the tested beam specimens, calculated using Equation (16) to evaluate the cracked section stiffness. The hybrid reinforcement systems exhibited significantly higher Ie values, with the CF_ST_MN_2 and CF_ST_MN_2.5 specimens each recording 94.15 in4, and the GF_ST_MN_2 specimen reaching 91.75 in4. These results emphasize the synergistic benefits of combining steel and FRP reinforcement, where the steel component contributes ductility and effective crack-bridging capabilities, while the FRP component provides additional tensile strength. The combined action of these materials enables hybrid systems to maintain superior flexural rigidity even after the initiation and propagation of cracks, supporting stable service-level performance and limiting deflections under load. In contrast, the FRP-only reinforced specimens demonstrated significantly lower effective stiffness after cracking. The CF_MN_2 specimen exhibited an Ie of 7.8 in4, while the GF_MN_2 specimen recorded an even lower value of 1.57 in4. These results highlight the vulnerability of FRP-only systems to pronounced stiffness degradation post-cracking due to the absence of yielding and the limited capacity for strain redistribution within the system. For comparison, the steel-reinforced control beam (3-CONT-MN-2) achieved an Ie of 82.7 in4, reflecting the well-established ability of steel reinforcement to maintain effective stiffness in cracked high-strength concrete members.

Figure 11.

Effective moment of inertia for the beam specimen.

Design models often underestimate cracking moments in FRP-reinforced and hybrid concrete beams because they neglect the tensile capacity of FRP materials, bond–slip characteristics at the reinforcement-concrete interface, and tension stiffening effects that enhance crack resistance and delay crack formation. These mechanisms contribute to improved crack control and stiffness retention, especially in hybrid systems where steel reinforcement provides additional tension stiffening, but they are not fully captured by existing predictive models. Incorporating these factors into design provisions is essential to improve the accuracy of cracking moment predictions in high-strength concrete members reinforced with FRP and hybrid systems [11].

Taken together, these findings reaffirm that hybrid reinforcement strategies are effective in balancing stiffness and ductility under service conditions, offering a practical approach for achieving enhanced serviceability performance in high-strength concrete beams by mitigating the stiffness reductions typically associated with FRP-only reinforcement systems.

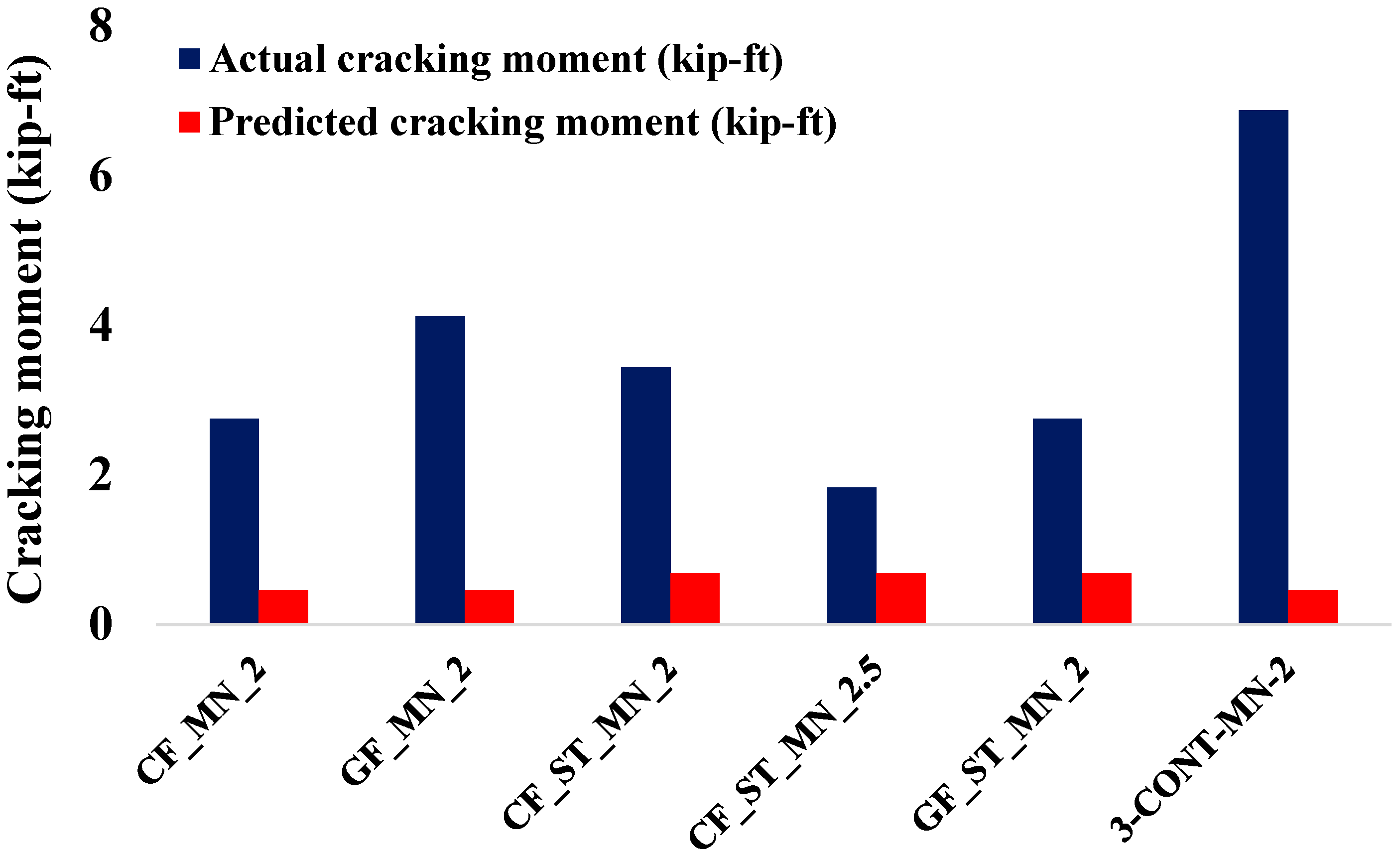

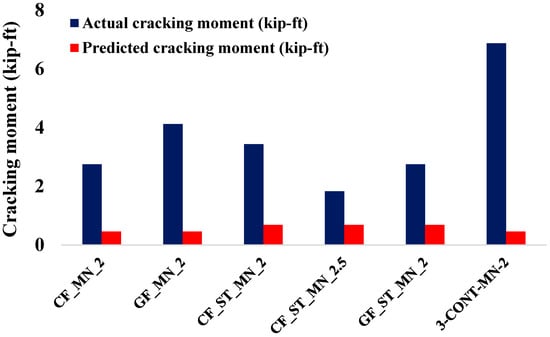

4.8. Cracking Moment

Figure 12 compares the predicted and experimentally measured cracking moments of the tested beam specimens, with predictions calculated using Equations (23) and (24). The FRP-only specimens exhibited substantial underestimations by the predictive model. For instance, the GF_MN_2 specimen recorded a measured cracking moment of 4.13 kip-ft compared to a predicted value of 0.46 kip-ft, representing an increase of approximately 800%. Similarly, the CF_MN_2 specimen exhibited a measured cracking moment of 2.75 kip-ft against the same predicted value of 0.46 kip-ft, indicating a sixfold increase. These pronounced discrepancies suggest that existing empirical models do not adequately account for the tensile capacity of FRP grids, nor do they capture the effects of bond characteristics and the micro-crack distribution inherent in high-strength concrete, all of which contribute to increased cracking resistance in practice.

Figure 12.

Comparison of predicted and actual cracking moment for the beam specimen.

The hybrid specimens demonstrated improved performance, yet the predictive models remained conservative. The CF_ST_MN_2 specimen achieved a measured cracking moment of 3.44 kip-ft, while the CF_ST_MN_2.5 specimen recorded 1.83 kip-ft, and the GF_ST_MN_2 specimen reached 2.75 kip-ft, all compared against the same predicted value of 0.69 kip-ft. These results indicate that the presence of steel within hybrid reinforcement systems enhances crack resistance by providing tension stiffening and effective stress redistribution, leading to higher cracking moments. However, current design codes still fail to fully capture these mechanisms within hybrid systems, resulting in conservative estimates. The steel-reinforced control specimen (3-CONT-MN-2) demonstrated a measured cracking moment of 6.88 kip-ft, considerably higher than the predicted value of 0.46 kip-ft. This further indicates that current predictive formulations may inadequately represent the higher tensile performance of high-strength concrete and the beneficial interaction between steel reinforcement and concrete during crack formation.

The underestimation of cracking moments in FRP-reinforced and hybrid concrete beams by current design models can be attributed to the neglect of critical factors such as the tensile capacity of FRP materials, bond–slip behavior, and tension stiffening effects, which contribute to higher cracking resistance in practice. These mechanisms enhance crack control and delay crack formation, particularly in systems combining steel and FRP reinforcement, but are not fully captured in existing predictive equations, leading to conservative estimates of cracking moments. Previous studies have identified these limitations, highlighting the need for refined models that account for these factors in high-strength concrete applications [16,32].

Collectively, these findings underscore the need to refine cracking moment prediction models to incorporate the contributions of tension stiffening, bond behavior, and micro-crack development in FRP and hybrid-reinforced high-strength concrete beams, thereby improving the accuracy of cracking behavior assessments under service loads.

4.9. Failure Modes and Cracking Behavior

All tested beams, including FRP-reinforced, hybrid-, and conventional steel-reinforced specimens, ultimately failed in shear, aligning with the experimental design that intentionally omitted shear reinforcement to induce brittle shear failure. Flexural failure was not observed in any specimen. Crack development followed a consistent progression across all beams: initial vertical flexural cracks appeared in the midspan tension zone, followed by inclined shear cracks within the shear spans, which evolved into dominant diagonal cracks that led to sudden collapse. These critical diagonal cracks typically originated near the supports and propagated upward toward the loading points.

The steel-reinforced control beam (3-CONT-MN-2) with an a/d ratio of 2.0 exhibited a clear and abrupt shear failure upon reaching its ultimate shear capacity. Vertical cracks initially formed around midspan at approximately 7.5 kips and progressed toward the compression zone as flexural demand increased. However, prior to the full engagement of steel yielding and effective stress redistribution, a major diagonal shear crack developed from the support toward the loading point, resulting in rapid brittle failure. The inherent brittleness of high-strength concrete, coupled with the absence of transverse reinforcement, contributed to the shear-dominated collapse mechanism, as shown in Figure 13a.

Figure 13.

Mode of failure for beam (a) 3CONT_MN_2, (b) CF_MN_2, (c) GF_MN_2, (d) CF_ST_MN_2.5, (e) CF_ST_MN_2, and (f) GF_ST_MN_2.

For the FRP-reinforced specimens, the first-cracking loads were lower, ranging from approximately 2.0 to 4.5 kips, reflecting the reduced tensile stiffness and limited crack-bridging capacity of FRP compared to steel reinforcement. Among these, the GFRP-only specimen (GF_MN_2) exhibited the highest first-cracking load (4.5 kips), likely attributable to its lower modulus of elasticity, which delayed stress concentration and permitted larger deflections before initial cracking. Conversely, the hybrid CFRP/steel specimen (CF_ST_MN_2) recorded the lowest first-cracking load (2.0 kips), potentially indicating early interface slip or localized stress concentrations at the CFRP grid–concrete interface. The remaining specimens, including CF_MN_2, GF_ST_MN_2, and CF_ST_MN_2.5, demonstrated initial cracking near 3.0 kips, suggesting similar tensile resistance in their uncracked states.

Following initial cracking, vertical flexural cracks continued to propagate while diagonal shear cracks developed within the shear spans and extended toward the loading points. In each specimen, a dominant diagonal crack eventually formed and propagated rapidly through the web, compromising the concrete’s load-carrying capacity and confirming a diagonal tension failure mode. Figure 13a–f depict these failure patterns. For instance, Figure 13b illustrates a pronounced diagonal crack in the CFRP-only specimen (CF_MN_2), while Figure 13c highlights wide, inclined cracking in the GFRP-only specimen (GF_MN_2). The hybrid specimens, shown in Figure 13d–f, exhibited similar diagonal cracking patterns but with narrower crack widths due to the bridging and dowel effects provided by steel reinforcement, thereby demonstrating improved post-cracking integrity. Across all specimens, the observed failure cracks were inclined at approximately 45–55° relative to the horizontal, consistent with classical shear failure mechanisms in reinforced concrete beams. No significant horizontal splitting cracks were noted at the reinforcement level, indicating that aggregate interlock and dowel action remained active until failure. The incorporation of FRP grids, even within hybrid reinforcement systems, did not alter the fundamental diagonal tension failure mode in the absence of shear reinforcement.

In high-strength concrete beams without stirrups, the absence of transverse reinforcement reduces crack-bridging capacity, allowing early flexural cracks to transition into steep diagonal shear cracks that lead to sudden brittle shear failures, as reported by Chen et al. [33]. In addition, Cao et al. [34] observed that FRP-reinforced beams, despite their high tensile strength, often exhibit lower first-cracking loads and develop wide, inclined cracks that progress rapidly to failure when shear reinforcement is absent, indicating that FRP alone does not prevent brittle shear failure. Al-Nimry and Neqresh [23] further noted that while CFRP confinement can improve crack distribution and reduce crack widths under loading, it cannot fully prevent brittle failures if lateral confinement is insufficient. These mechanisms highlight that although FRP and hybrid CFRP-steel reinforcement can enhance crack control and delay crack propagation, they do not fundamentally change the shear failure mechanism under shear-dominated conditions in the absence of stirrups, emphasizing the need for adequate shear reinforcement in high-strength concrete beams.

The research findings highlight the critical importance of adequate shear reinforcement in high-strength concrete beams with FRP grids, as their inherent brittleness limits reserve capacity following diagonal cracking. While hybrid systems exhibited improved crack control and energy dissipation due to the steel’s crack-bridging capabilities, they remained susceptible to brittle shear failure, underscoring the necessity of comprehensive shear design strategies for advanced reinforcement systems. The observed diagonal shear cracking is consistent with diagonal tension failure mechanisms commonly reported in shear-critical reinforced concrete members. The presence of steel reinforcement in hybrid beams enhanced dowel action and aggregate interlock across inclined cracks, resulting in improved crack control and delayed shear failure. In contrast, FRP-only beams exhibited reduced post-cracking shear transfer capacity due to limited dowel action and bond-dependent crack-bridging behavior of the FRP grids [35].

5. Conclusions

This study experimentally investigated the shear behavior of high-strength concrete (HSC) beams reinforced with conventional steel, fiber composite grids (CFRP and GFRP), and hybrid reinforcement systems, all tested without transverse reinforcement. A steel-reinforced control specimen sourced from the literature was included to benchmark the performance of alternative reinforcement strategies. Beam specimens were evaluated under varying shear span-to-depth ratios to assess their structural capacity, cracking behavior, failure modes, and serviceability performance.

The key findings are summarized as follows:

- FRP-only beams exhibited significantly lower peak capacities and brittle shear failures, with the CFRP-reinforced beam reaching approximately 70% and the GFRP-reinforced beam achieving about 51% of the steel control beam’s capacity. In contrast, hybrid reinforcement systems notably enhanced performance. For instance, the CFRP-steel hybrid at an a/d of 2.0 attained nearly 97% of the control beam’s peak load, while the GFRP-steel hybrid reached around 88%, demonstrating the advantages of combining ductile and high-strength reinforcements.

- All specimens failed in shear as intended due to the absence of stirrups. First-cracking loads ranged from 2 to 4.5 kips, governed by the tensile capacity of the concrete. Crack patterns displayed classical diagonal tension failures, with FRP-only beams exhibiting wider cracks and more abrupt collapse, while hybrid beams showed narrower diagonal cracks and more stable crack propagation due to the crack-bridging and dowel effects of steel reinforcement.

- Experimental results for moment capacity and shear strength were compared with theoretical predictions using the Canadian Educational Module Code. Predictions for shear strength (Equations (11) and (12)) and maximum load (Equation (13)) aligned well with the experimental results for hybrid- and steel-reinforced beams but substantially underestimated the capacities of FRP-only beams, sometimes by over 200%, confirming the conservative nature of current design provisions for non-metallic reinforcement systems.

- Predicted serviceability parameters, including effective moment of inertia (Equation (14)), cracking moment (Equations (23) and (24)), and midspan deflection (Equation (21)), showed good agreement with experimental results for hybrid beams but poor accuracy for FRP-only beams. The FRP-only specimens exhibited stiffer behavior and higher cracking resistance than predicted, indicating that existing models do not adequately capture bond–slip behavior, tension stiffening, and micro-cracking mechanisms in fiber-grid-reinforced sections.

- From a design perspective, the results indicate that current code-based shear prediction models tend to underestimate the shear capacity of FRP-reinforced and hybrid-reinforced HSC beams, particularly when post-cracking mechanisms and reinforcement interaction contribute significantly to shear resistance. While existing provisions remain conservative, their direct application may not fully capture the shear contribution of FRP grids. These findings highlight the need for refinement of shear design models to improve reliability and efficiency when applying current codes to FRP-reinforced concrete members.

Future research should focus on refining predictive models for FRP-reinforced HSC beams, particularly under shear-critical conditions. Further investigations into bond and anchorage behavior, long-term fatigue performance under cyclic loading, and hybrid configurations with limited transverse reinforcement would contribute to ensuring structural safety while facilitating the practical application of fiber composite grids in reinforced concrete structures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.I. and M.A.M.; methodology, A.I.; validation, M.A.M. and H.H.; formal analysis, M.A.M.; investigation, M.A.M. and A.I.; resources, A.I.; data curation, M.A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T.I.T. and H.H.; writing—review and editing, M.T.I.T., H.H. and A.I.; supervision, A.I.; project administration, A.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- French, C.; Mokhtarzadeh, A.; Ahlborn, T.; Leon, R.T. High-strength concrete applications to prestressed bridge girders. Constr. Build. Mater. 1998, 12, 105–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, F.H.; Barluenga, G. Fire performance of recycled rubber-filled high-strength concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2003, 34, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbasha, N.M. Reinforced HSC Beams. Key Eng. Mater. 2014, 629–630, 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, L.F.A.; Lopes, S.M.R. Flexural ductility of high-strength concrete beams. Struct. Concr. 2003, 4, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cladera, A.; Marí, A. Experimental study on high-strength concrete beams failing in shear. Eng. Struct. 2005, 27, 1519–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Emparanza, A.; De Caso Y Basalo, F.; Kampmann, R.; Adarraga Usabiaga, I. Evaluation of the bond-to-concrete properties of GFRP rebars in marine environments. Infrastructures 2018, 3, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, S.; Rossini, M.; Knight, C.; Nanni, A. New directions for reinforced concrete coastal structures. J. Infrastruct. Preserv. Resil. 2021, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wu, G.; Li, L.; Guan, Z.; Guo, M.; Yang, L.; Li, Z. Experimental investigations on bond behavior between FRP bars and advanced sustainable concrete. Polymers 2022, 14, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Duan, Z.; Guo, Y.-C.; Li, X.; Zeng, J. Behavior of fiber-reinforced polymer-confined high-strength concrete under Split-Hopkinson pressure bar (SHPB) impact compression. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almahmood, H.; Ashour, A.; Sheehan, T. Flexural behaviour of hybrid steel-GFRP reinforced concrete continuous T-beams. Compos. Struct. 2020, 254, 112802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, F.M.; Deifalla, A.F. Shear strength of FRP reinforced deep concrete beams without stirrups: Test database and a critical shear crack-based model. Compos. Struct. 2022, 307, 116636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikoo, M.R.; Aminnejad, B.; Lork, A. Firefly algorithm-based artificial neural network to predict the shear strength in FRP-reinforced concrete beams. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2023, 2023, 4062587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla, P.; Dolati, S.S.K.; Polanco, J.O.; Mehrabi, A.; Nanni, A.; Ding, J. Damage detection in FRP-reinforced concrete elements. Materials 2024, 17, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Fadhli, S.K.I. Shear performance of reinforced concrete beams with GFRP. Mater. Sci. Forum 2020, 1002, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, N.; Abbas, A.A.; Sharif, M.S.; Ahmed, H.M. Machine learning-based prediction of compressive performance in circular concrete columns confined with FRP. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Innovation and Intelligence for Informatics, Computing, and Technologies (3ICT), Sakheer, Bahrain, 20–21 November 2023; pp. 413–420. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.H.; Mohamed, H.M.; Chalioris, C.E.; Deifalla, A.F. Evaluating the shear design equations of FRP-reinforced concrete beams without shear reinforcement. Eng. Struct. 2021, 235, 112017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lv, H.L.; Zhou, S.C. Flexural behavior of innovative hybrid GFRP-reinforced concrete beams. Key Eng. Mater. 2012, 517, 850–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Zhang, C. Shear strength calculating model of FRP bar reinforced concrete beams without stirrups. Eng. Struct. 2020, 221, 111025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla, P.; Dolati, S.S.K.; Polanco, J.O.; Mehrabi, A.; Nanni, A.; Dinh, K. Feasibility of conventional non-destructive testing methods in detecting embedded FRP reinforcements. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Cao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, W.W. A state-of-the-art review on hybrid GFRP-concrete bridge deck systems. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 2021, 5548396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, S.J.S.; Rodzi, M.A.H.M.; Ayop, S.S.; Shahidan, S.; Mokhatar, S.N.; Salleh, N. Shear strengthening of reinforced concrete beams using fibre reinforced polymer: A critical review. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1200, 012015. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, J.; Gao, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, H. Improving ductility for composite beams reinforced with GFRP tubes by using rebars/steel angles. Polymers 2022, 14, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nimry, H.; Neqresh, M. Confinement effects of unidirectional CFRP sheets on axial and bending capacities of square RC columns. Eng. Struct. 2019, 196, 109329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.M.; Lan, Z.; Xiong, M.; Xu, Z. Compressive behavior of FRP-confined steel-reinforced high strength concrete columns. Eng. Struct. 2020, 220, 110990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Tang, J.-P.; Feng, R.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, J.-H. Experimental investigation of the shear performance of corroded RC continuous beams strengthened with polarized CFRCM plates. Eng. Struct. 2025, 333, 120145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakjira, T.; Ebead, U. Simplified compression field theory-based model for shear strength of fabric-reinforced cementitious matrix-strengthened reinforced concrete beams. ACI Struct. J. 2020, 117, 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Arowojolu, O.; Ibrahim, A.; Almakrab, A.; Saras, N.; Nielsen, R. Influence of shear span-to-effective depth ratio on behavior of high-strength reinforced concrete beams. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2021, 15, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Concrete Institute (ACI). Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete (ACI 318-16) and Commentary (ACI 318R-16); ACI: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- ISIS Canada Research Network. Reinforcing Concrete Structures with Fibre Reinforced Polymers (FRPs): Design Manual No. 3; ISIS EC Module 3: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, D.; Zhang, C. Shear strength prediction model of FRP bar-reinforced concrete beams without stirrups. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 7516502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirar, S.; Sogut, K.; Caro, M.; Rahman, R.; Theofanous, M.; Faramarzi, A. Effect of shear span-to-effective depth ratio and FRP material type on the behaviour of RC T-beams strengthened in shear with embedded FRP bars. Eng. Struct. 2025, 332, 120105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgabbas, F.; El-Sayed, A.K.; Benmokrane, B. Testing of concrete beams reinforced with glass fiber–reinforced polymer bars. ACI Struct. J. 2016, 113, 1023–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.M.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Z. Shear behavior of steel reinforced high-strength concrete beams with and without stirrups. Eng. Struct. 2020, 206, 110146. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Zuo, Y.; Liu, W. Experimental investigation on shear behavior of FRP bar reinforced concrete beams without stirrups. Eng. Struct. 2021, 229, 111619. [Google Scholar]

- Wakjira, T.G.; Ebead, U. Internal transverse reinforcement configuration effect of EB/NSE-FRCM shear strengthening of RC deep beams. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 166, 758–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.