Abstract

Climate change is increasing the frequency and intensity of natural hazards, placing additional stress on critical infrastructure systems. Addressing these challenges requires both robust evaluation frameworks and the inclusion of Nature-Based Solutions (NbSs) alongside conventional protection measures. Building on the RAMSSHEEP concept, originally proposed for risk-driven maintenance, and later further developed and applied in, e.g., previous Horizon projects and COST Action TU1406, this study integrates natural hazard considerations and NbS risk mitigation measures into a comprehensive approach to evaluate the resilience of critical infrastructure. The novel methodology involves a structured expert elicitation process with participants from the Horizon NATURE-DEMO project, to adapt and extend the RAMSSHEEP framework for resilience-oriented transformation. This also includes alignment with established hazard and risk assessment systems to ensure methodological consistency and applicability of the final concept. The resulting framework enables systematic evaluation of infrastructure vulnerability and resilience, explicitly accounting for natural hazards and the contribution of NbSs to risk mitigation. The expected outcome is an objective, repeatable assessment methodology that supports decision-makers in planning, prioritizing, and monitoring resilience-enhancing measures across the infrastructure life cycle. A particular focus of this contribution lies in the methodological approach, ensuring its applicability within interdisciplinary and multi-level decision-making contexts.

1. Introduction

Critical infrastructure systems form the backbone of modern societies, ensuring the provision of essential services such as mobility, energy supply, and public administration [1]. In alpine regions, however, the reliable operation of these systems is increasingly challenged by natural hazards, including debris flows, rockfall, avalanches, and floods [2,3]. These hazards pose a particular threat to lifeline infrastructure such as road networks, energy transmission systems, and municipal facilities, where service disruptions can have severe socioeconomic impacts [4,5].

The risk profile of alpine regions is further intensified by climate change, which is expected to increase the frequency and magnitude of extreme events [3,6]. This evolving hazard landscape calls for robust and adaptive evaluation approaches that can capture the complex interactions between infrastructure assets, environmental conditions, and societal needs.

In this context, the RAMSSHEEP evaluation framework—addressing Reliability, Availability, Maintainability, Safety, Health, Environment, Economics, and Politics—offers a structured methodology for assessing infrastructure performance and resilience. Developed within the COST Action TU1406, the framework combines technical performance evaluation with a broader set of societal and environmental criteria [7]. A distinguishing feature of RAMSSHEEP is its ability to integrate both conventional “grey” protection measures (e.g., galleries, retention dams, and net systems) and NbS. This dual focus reflects the growing recognition that sustainable hazard mitigation requires combining engineered structures with ecosystem-based approaches.

The importance of resilience assessment frameworks for critical infrastructure has been highlighted in numerous recent studies [8,9,10]. Many approaches emphasize system reliability and risk exposure, while increasing attention is being paid to adaptive capacity and sustainability dimensions [11,12]. Frameworks such as PEOPLES (population, environment, organized services, physical infrastructure, lifestyle/competence, economic development, sociocultural capital), IRF (Infrastructure Resilience Framework), and CIRI (Critical Infrastructure Resilience Index) have advanced quantitative and qualitative metrics for assessing resilience. However, while the main focus of the first two is not asset management, it is believed that the latter may suffer from a weakness that could compromise its results. This topic is addressed in Section 2.

The RAMSSHEEP framework builds on these efforts by incorporating economic, environmental, and political considerations and by explicitly integrating NbSs, thus addressing emerging challenges in asset-level optimization and infrastructure risk management under climate change.

The goal of this contribution is to demonstrate the RAMSSHEEP evaluation process in detail through a dedicated assessment tool applied to the Lattenbach catchment area in Tyrol, Austria. The analysis focuses on critical infrastructure assets—including roads, energy supply, and the urban area of Pians—and provides a comparative evaluation of grey protection measures and NbS. The results are embedded within a comprehensive decision-support framework, illustrating the full potential of RAMSSHEEP for integrated infrastructure risk management in hazard-prone alpine regions.

Furthermore, this study aims to show how the assessment process and expert involvement must be designed to establish a transparent, traceable decision-making framework. This approach ensures that all stakeholders are engaged and supportive of the outcomes, fostering consensus and shared ownership of resilience planning and investment decisions. The work also addresses the integration of RAMSSHEEP with existing local and national hazard and risk assessment systems and its embedding into strategic planning tools with CAPEX (Capital Expenditure) and OPEX (Operational Expenditure) parameters. Special attention is given to methodological aspects, including interdisciplinary stakeholder engagement, role definition, and the establishment of a cyclic, life-cycle-oriented assessment process.

2. Comparative Analysis: PEOPLES vs. IFR vs. CIRI vs. RAMSSHEEP

This section, in addition to the RAMSSHEEP framework, provides a brief description of three resilience assessment frameworks used in the domains of infrastructure, communities, and asset management: PEOPLES Resilience Framework, Critical Infrastructure Resilience Index (CIRI), and Infrastructure Resilience Framework (IRF).

2.1. PEOPLES

Developed by Renschler et al. [13] to define and measure community disaster resilience, PEOPLES is a seven-dimensional framework (population and demographics; environmental/ecosystem; organized governmental services; physical infrastructure; lifestyle and community competence; economic development; and social–cultural capital) intended as a holistic basis for both quantitative and qualitative modelling of community functionality before/after disasters. This framework is socially centred, shifting the focus from purely technical systems and physical infrastructure, admitting that resilience is fundamentally about people and their ability to cope and adapt, and therefore with a strong emphasis on social and human factors. PEOPLES is a broad approach for understanding social drivers of resilience and for community-wide socio-economic resilience assessments.

2.2. IRF

The Infrastructure Resilience Framework (IRF) was developed by the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) to help communities, regions, and the private sector incorporate resilience into planning for critical infrastructure [14]. Flexible, pragmatic, and action-oriented, it is a process that helps organizations identify critical infrastructure, assess risks, and develop and implement resilience solutions to support community resilience with the support of stakeholders. Intended for planners, it is a guidance tool with defined steps—lay the foundation, identify assets and hazards, assess risks, identify actions, and implement and monitor—to convert risk assessments into plans rather than producing a metric.

2.3. CIRI

The Critical Infrastructure Resilience Index (CIRI) developed by Pursiainen et al. is a methodology designed to evaluate organizational and technological resilience across the crisis management cycle: risk assessment → prevention → preparedness → warning → response → recovery → learning [15]. CIRI provides a consistent way to assess resilience by synthesizing data and simplifying complex information. Based on process maturity levels, it aggregates individual sector-specific resilience indicators into a unique, quantitative overall index, enabling the comparison of resilience for different assets or sectors for strategic decision-making. The aggregation of many indicators into a single score can, however, obscure the underlying drivers of resilience.

2.4. RAMSSHEEP

Originally proposed by Wagner and van Gelder [16,17] and promoted in Dutch infrastructure/asset management practice (Rijkswaterstaat), RAMSSHEEP is an asset-focused, multi-criteria approach to support risk-driven maintenance and lifecycle optimization of physical infrastructure. It extends the conventional RAMS (reliability, availability, maintainability, and safety) engineering framework for evaluating the performance and safety of a system or product, with additional dimensions expressed as “SHEEP” (security, health, environment, economics, and politics). This aggregation results in a broad, structured, and comprehensive set of performance/impact aspects, forcing evaluations beyond simple technical performance or cost. It integrates hard engineering metrics with socio-political factors, which are often overlooked in purely technical analyses. Designed to ensure all major facets of a system’s lifecycle and impact, RAMSSHEEP is a decision-making tool that supports complex decision-making by weighing competing factors (e.g., a more reliable system may be less economical).

3. Methodology

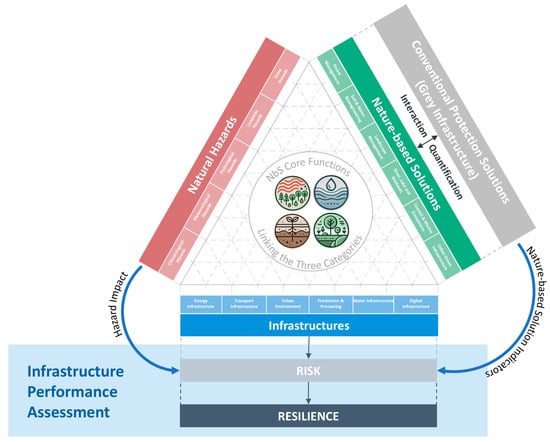

As previously mentioned, within the framework of the Horizon project NATURE-DEMO, we extend the classical RAMSSHEEP procedure, originally developed to assess infrastructures based on six dimensions: reliability, availability, maintainability, environment, costs, and politics. This extension actively incorporates, for the first time, the surrounding infrastructure environment. The performance assessment process now takes natural hazards into account, with explicit consideration of their characteristics and impact, as well as the existence or implementation of mitigation strategies such as conventional protection solutions (grey infrastructure) and NbS. The methodology flowchart is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Methodology flowchart.

For the correct application of this extended RAMSSHEEP tool, it is essential to establish and follow a structured step-by-step process plan. This plan includes the systematic integration of relevant information and the involvement of experts from diverse disciplines. Consistent implementation of this approach is crucial for the quality of the results, the long-term success, and the further development and added value of the RAMSSHEEP framework.

Furthermore, a clear definition and formulation of evaluation metrics in the form of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) is carried out. For this reason, the following methodology section is divided into corresponding subsections, in which we systematically present the procedure and subsequently demonstrate the application of the extended RAMSSHEEP approach using the Lattenbach case study.

3.1. Basic Information and Characteristics of the Lattenbach Valley Demonstrator and Involvement of Relevant Stakeholders in the Evaluation Process

The Lattenbach Valley is located in the Austrian Alps within the Landeck District of Tyrol and is renowned for its natural beauty as well as diverse recreational opportunities, such as hiking, mountain biking, and numerous resorts, making it a popular tourist destination. In addition to its scenic and touristic importance, the valley also hosts critical infrastructure, including the European route E60—a major transcontinental road spanning approximately 8200 km from Brest, France, to Irkeshtam, Kyrgyzstan. With about 5000 residents, the region also has a significant population.

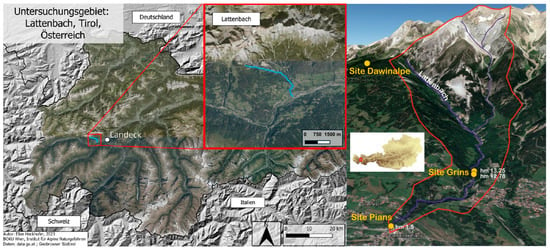

The Lattenbach catchment area includes the main stem of the Lattenbach on the western side and the Radunbach on the eastern side, which merge approximately 1.7 km downstream from the upper catchment and flow into the Sanna River within the municipality of Pians (Figure 2). The valley is particularly vulnerable to natural hazards such as debris flows and landslides triggered by extreme rainfall events resulting from altered precipitation patterns. These events are expected to increase in frequency and intensity, destabilizing slopes and threatening both the regional ecosystem and critical infrastructure.

Figure 2.

Location (left) [18] and overview (right) [19] of the Lattenbach catchment area.

Key existing infrastructure includes, besides the European route E60, local roads, bridges, energy supply systems, and municipal facilities within the Pians area. These infrastructures are central to the population’s supply and mobility as well as economic activities.

Given the hazard exposure, various stakeholder groups play essential roles in the risk management of the Lattenbach Valley:

- Public Sector: The municipality of Pians and district authorities are responsible for local land-use planning, hazard mapping (e.g., torrential risk maps), emergency management, and municipal risk communication. At the provincial level (Tyrol) and federal level, government agencies support regional hazard mapping, enforcement of safety standards, early warning systems, and funding allocation. At the national level, the Austrian Federal Ministry of the Interior (BMI) coordinates disaster management, risk assessments, and warning systems such as KATWARN.

- Local Community: Residents, as land and infrastructure users, need to be engaged, especially in hazard awareness and participatory planning. Volunteer rescue organizations, including fire brigades, Red Cross, and mountain rescue services, provide crucial operational response capabilities central to post-event risk management.

- Science and Technical Expertise: Geotechnical and natural hazard specialists conduct geo–hydro–mechanical slope analyses and assess landslide susceptibility. Civil and infrastructure engineers carry out risk assessments of critical structures (e.g., bridges and roads) using physical KPIs, condition monitoring, and multi-level analyses.

- Private Sector: Infrastructure owners and operators are responsible for evaluating the structural resilience of key facilities such as roads, power systems, bridges, and utilities, applying stress-testing methodologies.

This broad involvement of all relevant stakeholders is essential to ensure a holistic and robust risk and resilience assessment in the Lattenbach Valley.

We involved representatives of torrent control authorities, long-term scientists who have observed Lattenbach’s development for decades, experts in alpine hazards, and NbS specialists from both scientific and torrent control stakeholder groups to conduct the evaluation process comprehensively and rigorously.

The experts were able to adequately represent the interests of the different stakeholder groups, as they are in continuous exchange with these groups. The region is an active, dynamically changing zone that requires ongoing hazard and mitigation evaluations. Therefore, we are directly involved in these processes and continuously receive information on current torrent control measures.

3.2. Integration of Local Assessments and Historical Event Data

Following the identification of key stakeholders, it is essential to comprehensively compile data for the Lattenbach catchment. This includes historical records, current information from stakeholder groups, scientific studies, and observations from monitoring activities. Past events, as well as already implemented and planned mitigation measures, were systematically collected and categorized, and their interrelations were analyzed.

Another important aspect was to understand the current strategies of the locally responsible stakeholders, such as how energy levels are assessed and how their evaluation and decision-making processes are structured.

The Lattenbach catchment drains steep alpine slopes above Pians. The channels exhibit typical torrent morphology with steep sections, confined gorges, and depositional fans near settlements and transportation corridors. Historically, debris flows have significantly transported bedload and caused sudden impacts on built-up areas, severely affecting infrastructure. There is a long local history of such events, with written records dating back to 1907. Since then, severe events have been documented with detailed dates, times, and descriptions. Events such as the debris flows in 1954, 1987, 2005, and 2012 destroyed bridges, damaged buildings, and disrupted transport and economic activities.

With technological advancements, monitoring stations have been installed throughout the valley to collect valuable data, including observed intensities (peak discharge, runout length, and flow and debris volumes), damage logs (infrastructure type, repair costs, and photographic documentation of physical damages), and hydrometeorological records (rain gauges, snowmelt, and temperature). This information, complemented by hazard maps, inventories of protective structures (check dams and retention basins), maintenance and inspection reports, geomorphological surveys, LiDAR data, orthophotos, and cross-sectional profiles of the streams, allows the integration of existing hazard and risk assessments by local authorities into the RAMSSHEEP methodology. This can be further supplemented by a detailed analysis of historical natural hazard events.

These data serve to validate risk indicators and calibrate model parameters regarding intensity, frequency, and damage potential, enabling their targeted use in decision-making processes, early warning systems, and recovery planning.

3.3. Integration of Grey Infrastructure and Nature-Based Solutions

As outlined, the Lattenbach catchment area predominantly relies on grey infrastructure due to the terrain conditions, prevailing hazards, and the immediate protection objectives for critical infrastructure.

In the longer term and with awareness of climate change, NbS and bioengineering measures must be strongly considered to stabilize and potentially mitigate existing processes. In other words, a full replacement of grey infrastructure, such as check dams, by NbS alone is neither feasible nor sensible in the Lattenbach context. Therefore, the goal is to combine NbS with grey infrastructure within the protection system to ensure the resilience of the infrastructure.

As part of the Horizon NATURE-DEMO project, a comprehensive catalogue of NbS measures and risk classification was developed. This classification forms the basis for the RAMSSHEEP-based assessment tool developed here and is embedded within the tool.

The RAMSSHEEP-based assessment framework, developed within the Horizon NATURE-DEMO project, provides a structured environment for integrating risk mitigation measures by allowing simulation-based evaluation of single or combined strategies.

Using this tool requires data on existing grey protective infrastructure (GPI) as well as an assessment of its current condition to evaluate the impact of proposed mitigation strategies. In the case of Lattenbach, a database was compiled from inventories, municipal planning documents, and field surveys, detailing the following:

- Debris retention basins: capacity, location, year of construction, and maintenance status.

- Check dams: type, dimensions, and sediment trapping efficiency.

- Deflection structures: orientation, design discharge, and protected zones.

An inventory of planned grey infrastructure measures was also documented.

Each technical protection measure was georeferenced and linked to hazard zones (identified in Austrian hazard maps) and exposure areas.

At the same time, a list of feasible NbS options was gathered based on suitability mapping, considering factors such as slope, soil stability, and vegetation cover. Identified NbS include the following, among others:

- Reforestation of erosion-prone slopes to enhance root cohesion.

- Expansion of natural retention areas in the upper catchment to delay runoff peaks.

- Near-natural riverbank structures to improve channel resilience and sediment transport balance.

Both types of measures are analyzed for their impact on the overall risk profile and simulated under various scenarios to assess their potential for hazard mitigation.

3.4. RAMSSHEEP as a Multi-Level Decision Support Framework and Scenario-Based Evaluation

The RAMSSHEEP evaluation module should not be seen as a tool that provides a single, definitive solution—nor is it designed to do so. Instead, it serves as a decision support framework that offers experts at various levels a basis for discussion, assessment, and development of a range of solution options. For example, it enables the evaluation of isolated grey protective measures—both current and future—the assessment of replacing grey infrastructure with NbS in present and climate change scenarios, as well as the combined evaluation of both approaches.

Scenario-based simulations are used to compare the effectiveness of different combinations of grey infrastructure and NbS in reducing risk. This evaluation is conducted using a multi-criteria approach that considers technical performance, ecological impacts, and socio-economic relevance. By comparing simulation outcomes with documented historical events, the validity of modelled hazard scenarios and the potential of integrated mitigation strategies to reduce risk are assessed.

The results produced by the tool vary depending on the expert groups involved, their knowledge and understanding of local conditions, and their experience with previously applied methods. Thus, the key strength of the RAMSSHEEP tool lies in its ability to facilitate a shared communication and evaluation platform that supports a collaborative and consensus-driven decision-making process among experts from diverse disciplines.

4. Case Study Lattenbach—Application and Results

A systematic assessment was conducted to evaluate the resilience of critical infrastructure in the Lattenbach catchment. The methodology distinguishes between grey protective measures, NbS, and their combined effects. The results from these separate assessments were integrated into a comprehensive risk matrix, enabling detailed scenario-specific analyses. The RAMSSHEEP framework, as defined within COST Action TU1406, where multiple KPI from the original procedure considered to be related were aggregated in a single KPI, was used to implement the entire assessment process, ensuring a structured and quantitative approach to risk assessment, based on the following set of KPIs, classified on the scale presented in Table 1 [20]:

- Safety, Reliability, and Security (SRS)—combined KPI.

- Availability and Maintainability (AM)—combined KPI.

- Economy (i.e., Costs) (EC).

- Environment (EV).

- Health and Politics (HP)—combined KPI.

Table 1.

Rating scale.

Table 1.

Rating scale.

| Rating | Condition |

|---|---|

| 1 | Very good |

| 2 | Good |

| 3 | Fair |

| 4 | Poor |

| 5 | Very Poor |

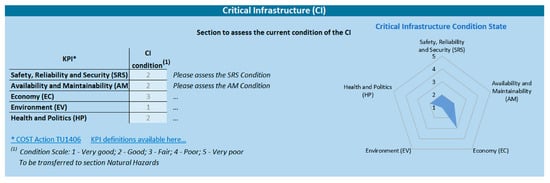

4.1. Evaluation of Critical Infrastructure

Using this methodology and the applied case study, critical infrastructure elements—such as roads, bridges, and energy supply networks—are systematically identified and assessed. The evaluation employs the RAMSSHEEP framework to determine the current condition, operational availability, and reliability of each component through individual assessment of KPIs as defined in the RAMSSHEEP model. The resulting data provides the basis for subsequent stages of the evaluation process. Particular emphasis is placed on the role of existing grey protective measures in enhancing infrastructure resilience. The outcome of this first phase of the procedure is shown in Figure 3 and, for better visualization of its content, in Table 2 that follows.

Figure 3.

Assessment of the current condition of existing critical infrastructure.

Table 2.

Assessment of the current condition of existing critical infrastructure.

This assessment shows that the infrastructure is operational, performing as expected, and showing no signs of reliability issues (SRS) or maintenance requirements (AM). Therefore, no significant expenditure (EC) is anticipated to keep it operational. Environmentally (EV), the infrastructure has no impact on the surrounding system, with a reduced effect on local politics and health (HP).

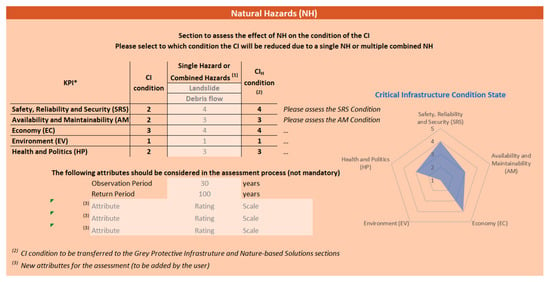

4.2. Evaluation of Natural Hazards Effects

In the second phase of the process, the post-event condition of infrastructures is evaluated by explicitly accounting for the impacts of natural hazards, specifically landslides and debris flows. Key attributes, including observed frequencies, return periods, and other factors affecting infrastructure performance, are integrated into the assessment (see Figure 4 and Table 3).

Figure 4.

Assessment of the effects of natural hazards on critical infrastructure.

Table 3.

Assessment of the effects of natural hazards on critical infrastructure.

As shown in Figure 4 and Table 3, for the Lattenbach infrastructure, several KPI ratings were adjusted based on updated hazard impact data and observed performance metrics:

- The Safety, Reliability, and Security (SRS) rating increased from good to poor, reflecting an increase in the perceived risk after updated hazard exposure.

- The Availability and Maintainability (AM) rating increased from good to fair, indicating a deterioration in maintainability due to challenges identified during post-event inspections, such as limited accessibility for maintenance and increased complexity in repair operations following hazard events.

- Equivalent adjustments were applied to Economy (EC) and Health and Politics (HP) parameters, with increased ratings reflecting the strains on post-event regional social requirements and drivers.

These changes result from combining historical performance data, updated hazard probabilities (return periods), and observed structural conditions. The numerical adjustments quantify the degree to which the infrastructure’s reliability, maintainability, and other performance attributes have improved or need to be revised in light of the natural hazard impacts.

The occurrence of a landslide and subsequent debris flow can pose severe risks to both public safety and infrastructure reliability. Rapidly moving masses of rock, soil, and water can disrupt, damage, and destroy facilities and infrastructure and endanger lives. These impacts not only threaten immediate safety but also compromise the long-term resilience and functionality of the region’s infrastructure.

Similarly, the availability and maintainability of infrastructure can be significantly reduced, with repair efforts hampered by unstable ground conditions and the risk of further failures. The accumulation of debris increases maintenance demands, requiring clearing operations, frequent inspections, and potential structural reinforcements. Over time, these challenges can strain local resources, making it harder to ensure the continuous and reliable operation of infrastructures.

Furthermore, landslides and related phenomena can have a substantial economic impact on the region. Apart from the costly repairs and reconstruction efforts, prolonged infrastructure disruptions hamper trade, tourism, and daily business operations. Local economy, particularly businesses dependent on reliable transport and supply chains, may face financial losses. Tourism can also suffer from reduced accessibility and negative perceptions of safety.

Additionally, far-reaching consequences for both public health and political stability may arise. Injuries, fatalities, and psychological trauma may result from sudden destruction, with disrupted access to medical facilities hindering healthcare. Politically, the disaster can place pressure on local and regional authorities to respond effectively, allocate emergency funds, and implement preventive measures.

4.3. Evaluation of Grey Protective Infrastructure Effects

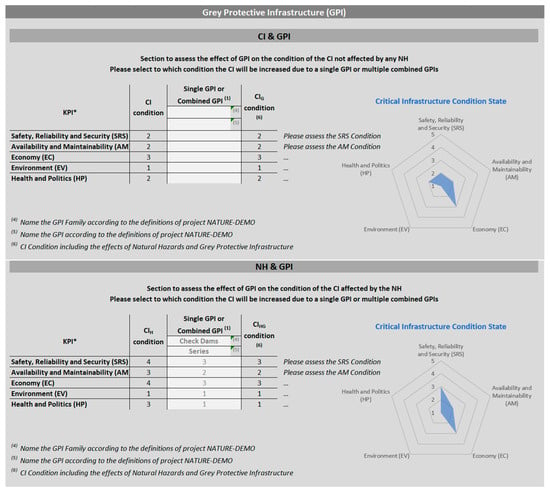

In Section 3, the benefits of implementing a GPI, or a combination of two GPIs, on the behaviour of the critical infrastructure are assessed. The best solutions are selected from a catalogue of suitable GPI compiled by experts. The analysis is carried out by assessing the positive effects on the condition of the infrastructure, whether it is affected by the risk(s) considered in Section 2 or is not affected by any natural hazard.

The assessment is carried out for two different situations: (i) when the infrastructure is not affected by any natural hazard, in which case the initial condition of the infrastructure is taken from Section 1; and (ii) when the influence of the natural hazards described in Section 2 is being studied, with the benefits of implementing GPI being assessed based on the condition of the infrastructure determined in that same section.

In the case of the Lattenbach Valley, the installation of check dams is considered a way to mitigate landslides and debris flows, greatly improving the safety of people and infrastructure reliability. By intercepting sediments, rocks, and other debris, check dams reduce the speed and volume of material reaching lower areas of the valley, reducing risks to public safety and infrastructure reliability. By reducing the volume and force of debris flows, these solutions also help keep infrastructure clear and functional, minimizing service interruptions. Over time, this preventive approach decreases the need for costly emergency repairs, allowing infrastructure to remain accessible, reliable, and easier to maintain.

Similarly, check dams can protect the local economy by preventing costly damage to infrastructure, property, and businesses. By doing so, these structures help maintain uninterrupted trade, tourism, and industrial activities, reducing economic losses and allowing for the allocation of public funds in development projects which would otherwise be used in repairs and maintenance.

Finally, check dams can improve both public health and political stability by reducing the risks of disasters, lowering the likelihood of injuries, fatalities, and stress-related health issues, and keeping access to medical facilities uninterrupted. Politically, it can strengthen public trust in local and regional authorities, demonstrating proactive governance and commitment to community safety, fostering stronger civic cooperation and support.

As shown in Figure 5 and Table 4, with the implementation of a GPI for landslide mitigation, it is estimated that the following adjustments will occur:

- The Safety, Reliability, and Security (SRS) rating increases from poor to fair.

- The Availability and Maintainability (AM) rating increases from fair to good.

- The Economy (EC) rating also increases from poor to fair.

- The Health and Politics (HP) rating increases from fair to very good.

Figure 5.

Assessment of the effects of GPI on critical infrastructure affected by natural hazards.

Table 4.

Assessment of the effects of GPI on critical infrastructure affected by natural hazards.

Table 4.

Assessment of the effects of GPI on critical infrastructure affected by natural hazards.

| KPI | CI Condition | Single GPI or Combined GPI | CIHG Condition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Check Dams | |||

| Series | |||

| Safety, Reliability, and Security (SRS) | Poor | Fair | Fair |

| Availability and Maintainability (AM) | Fair | Good | Good |

| Economy (EC) | Poor | Fair | Fair |

| Environment (EV) | Very good | Very good | Very good |

| Health and Politics (HP) | Fair | Very good | Very good |

4.4. Evaluation of Nature-Based Solutions Effects

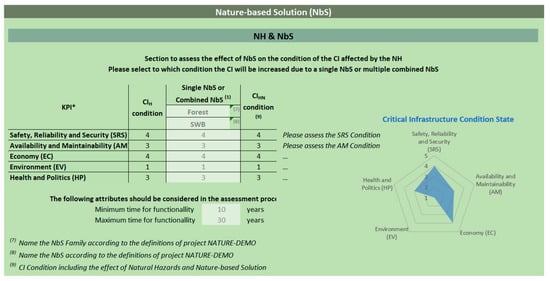

This section details the methodology for evaluating NbS measures implemented or planned in the Lattenbach catchment.

The procedure involves the selection, by an expert, of an NbS or a set of combined NbSs that best suit the infrastructure. This selection is made from a catalog of a predefined set of NbS families.

The carried out assessment involves determining the improvement in the infrastructure with the implementation of the selected solution, based on the condition determined in Section 2, where the effects of the natural hazard were determined. To this end, and given the very nature of NbSs, namely their time-limited effects, their minimum and maximum functionality times must be taken into account for future decision-making.

One of the possible NbSs applicable to Lattenbach would be the use of natural forest ecosystems, namely soil and water bioengineering (SWB), which uses vegetation and inert elements to stabilize slopes, control erosion, and manage water flow.

However, considering the type of natural event common in Lattenbach, namely the forces involved throughout the entire course of the valley, it is believed that the implementation of this measure alone would have a very limited impact, if any. Thus, it is estimated that the condition of the infrastructure determined in Section 2 (the impact of the natural hazard on the infrastructure) would remain unchanged, as shown in Figure 6 and Table 5.

Figure 6.

Assessment of the effects of NbS on critical infrastructure.

Table 5.

Assessment of the effects of NbS on critical infrastructure.

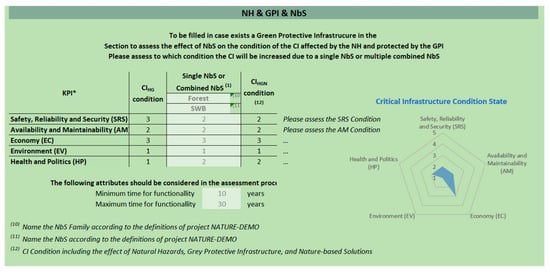

4.5. Combined Evaluation of Grey Infrastructure and NbS

Here, the combined effects of grey infrastructure and NbS on risk reduction are analyzed.

As in the previous section, the improvement in the condition of the infrastructure with the implementation of NbS is assessed. However, this time, it is taken into consideration a previously existing grey infrastructure (Section 3), as a way of mitigating the effects of a natural hazard (Section 2) on the initial condition of the infrastructure (Section 1). This analysis is therefore based on the values determined in Section 3. Figure 7 and Table 6 show the assessment procedure.

For this type of green solution, it is estimated that

- Safety, Reliability, and Security (SRS) will improve from fair to good.

- Health and Politics (HP) will decrease from very good to good.

- Other KPIs will remain unchanged.

Figure 7.

Assessment of the effects of combined GPI and NbS on critical infrastructure.

Table 6.

Assessment of the effects of combined GPI and NbS on critical infrastructure.

Table 6.

Assessment of the effects of combined GPI and NbS on critical infrastructure.

| KPI | CIHG Condition | Single NbS or Combined NbS | CIHGN Condition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forest | |||

| SWB | |||

| Safety, Reliability, and Security (SRS) | Fair | Good | Good |

| Availability and Maintainability (AM) | Good | Good | Good |

| Economy (EC) | Fair | Fair | Fair |

| Environment (EV) | Very Good | Very Good | Very Good |

| Health and Politics (HP) | Very Good | Good | Good |

The use of a solution such as SWB aims to reduce the amount of sediment, rocks, and other debris that can be transported, retained by check dams, and eventually reach the lower parts of the valley. As such, and as previously explained, it is possible to keep infrastructure clean and functional, reducing the need for repairs, minimizing service interruptions, and allowing infrastructure to remain accessible and reliable.

With regard to the reduced performance at the level of “Health and Politics,” more specifically to “Politics”, the perception that “soft” measures are less reliable than engineering structures, such as check dams, can lead to public dissatisfaction. If a disaster occurs before the NbS proves effective, authorities may face criticism for underestimating the risks, undermining public confidence, and triggering political accusations and disputes over risk management responsibilities.

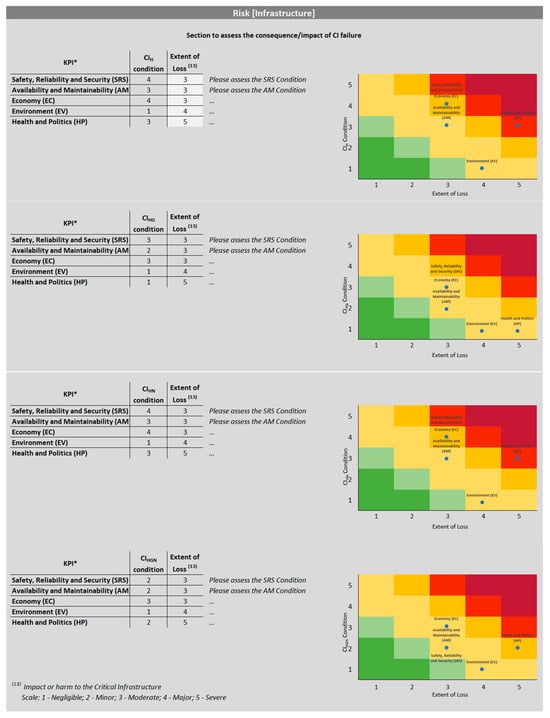

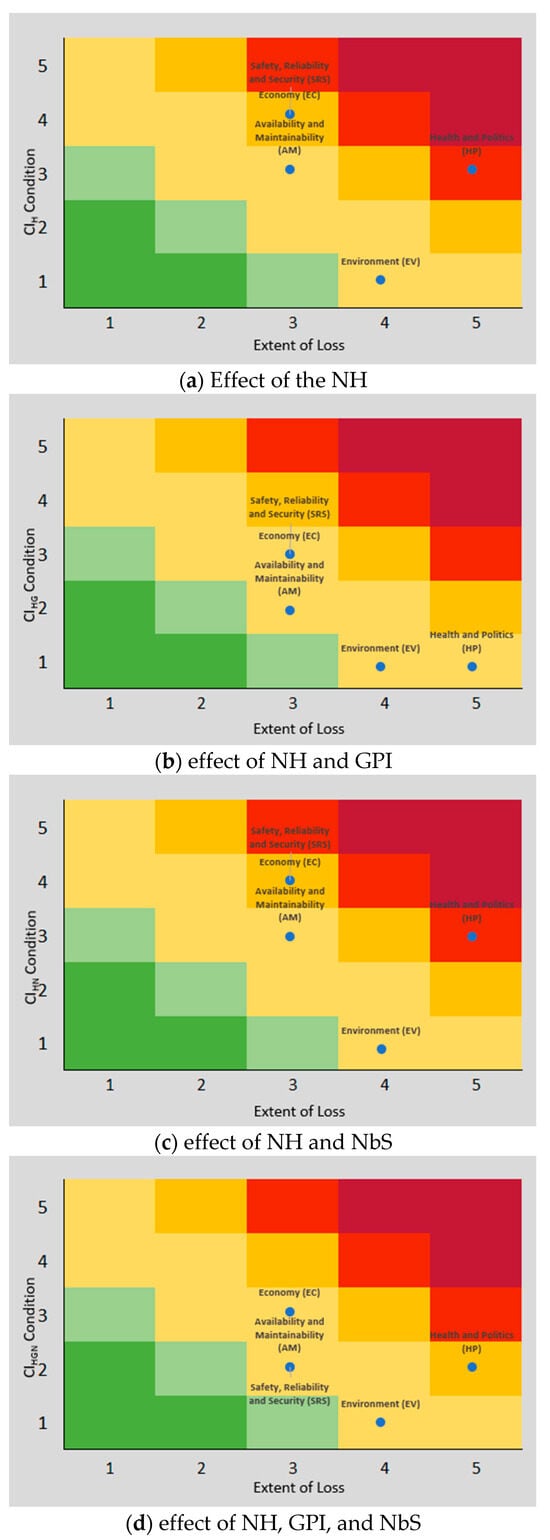

4.6. Integration of Results into a Risk Matrix

In the final stage of the procedure, the results of each of the previous steps are transposed into risk matrices that map the level of risk in the various dimensions (KPIs) versus the impact/damage (extent of loss) that the hazardous event represents (Figure 8). The assessment of the extent of infrastructure loss is better shown in Table 7 and Figure 9, considering the scale presented in Table 8.

Figure 8.

Risk matrix framework.

Table 7.

Assessment of the extent of infrastructure loss in the face of a natural event.

Figure 9.

Risk matrices: CI condition versus extent of loss.

Table 8.

Scale of loss extent.

The integration of the evaluation process into risk matrices serves as a decision-support tool, synthesizing the assessment outcomes into an accessible format, thus facilitating risk prioritization and management. Each matrix enables the identification of critical risk hotspots for each of the RAMSSHEEP KPI, supporting scenario comparison for stakeholder communication, highlighting infrastructure vulnerabilities and best mitigation measures for risk reduction, thus facilitating informed decision-making.

4.7. Scenario Analysis and Decision Support

The application of scenario-based simulations enables a comprehensive evaluation of the effectiveness of selected mitigation strategies under varying hazard intensities and climatic conditions, thereby supporting informed decision-making for resilient infrastructure management.

Scenario 1 represents the status quo, reflecting the baseline conditions of existing grey infrastructure. Serving as a reference point, this scenario facilitates the quantification of current risk levels and infrastructure resilience. Performance analysis under this scenario reveals vulnerabilities and critical failure points, thereby informing the identification of necessary interventions.

Scenario 2 examines the integration of NbS alongside existing grey infrastructure. The evaluation focuses on the synergistic effects of hybrid mitigation strategies, quantifying the enhancement in functionality and resilience attributable to NbS. Insights derived from this scenario elucidate the complementary strengths of both solution types, thereby advancing the decision-making process for optimized risk management.

Scenario 3 incorporates future climate stressors, simulating risk variability in conjunction with anticipated environmental changes. Assessment of the combined mitigation capacity of grey infrastructure and NbS under projected climate conditions informs the medium- to long-term sustainability and adaptability of integrated risk management approaches. Identification of potential weaknesses under this scenario facilitates the formulation of proactive adaptation strategies.

Collectively, these scenarios establish a decision-support framework that enables stakeholders to compare the performance, costs, and benefits of diverse mitigation strategies under future conditions. Outcomes from the simulations inform the prioritization of investments, maintenance planning, policy formulation, and stakeholder engagement, ultimately optimizing infrastructure resilience both presently and in the future.

5. Discussion—Risk Matrix for Selected Scenarios

The application of the extended RAMSSHEEP framework has demonstrated the critical role of a risk matrix in synthesizing complex multi-dimensional data into a clear and actionable format. The risk matrices developed for the three selected scenarios provide invaluable insights into how different mitigation strategies influence infrastructure resilience under varying conditions.

Scenario 1 (Status Quo with Existing Grey Infrastructure) serves as a baseline, illustrating current vulnerabilities in the critical infrastructure network when relying solely on existing grey protective measures. The risk matrix highlights hotspots where reliability, maintainability, or availability are compromised due to insufficient hazard mitigation. This scenario underscores existing risk concentrations and identifies priority areas where interventions could yield significant improvements.

Scenario 2 (Increased NbS Integration Alongside Grey Measures) shows notable risk reductions across multiple KPIs in the risk matrix, confirming the complementary benefits of integrating NbSs with traditional grey infrastructure. The NbS measures improve environmental and operational resilience, especially in areas where grey infrastructure alone may be limited or costly to enhance. The risk matrix visualization effectively captures these synergistic effects, aiding stakeholders in appreciating the value of hybrid mitigation approaches.

Scenario 3 (Future Climate Stress Test Combining Both Measures) provides a critical forward-looking assessment of infrastructure resilience under intensified hazard conditions projected from climate change. The risk matrix here reveals how combined mitigation strategies can buffer infrastructure performance against increasing stresses, while also exposing potential residual risks and temporal vulnerabilities linked to the durability of NbS. This scenario informs adaptive management by identifying infrastructure elements that may require additional reinforcement or monitoring over time.

Overall, the risk matrix framework facilitates a holistic understanding of infrastructure risk by integrating diverse assessment outputs—from initial conditions and hazard impacts to mitigation effects—within the RAMSSHEEP dimensions. It allows decision-makers to prioritize investments and maintenance by clearly visualizing where risk remains highest and where mitigation yields the greatest benefits. Moreover, the scenario comparisons embedded in the matrices support transparent communication with stakeholders, enabling collaborative planning for sustainable, resilient infrastructure development in alpine environments such as Lattenbach.

The application in this case study validates the extended RAMSSHEEP approach as a robust decision-support tool, capable of capturing the complexity of natural hazard risk management and guiding effective, evidence-based interventions. Future work may focus on further refining the risk matrix parameters and incorporating real-time monitoring data to enhance dynamic risk assessment capabilities.

RAMSSHEEP was developed primarily for risk-based maintenance planning and asset management in infrastructure systems and is often applied case-by-case rather than as a scalable, generalizable model. It was designed for specific asset classes (e.g., flood defences or transport bridges) with specific performance indicators. A practical weakness is that many risk criteria (e.g., “Availability” and “Safety”) are qualitatively defined and can be interpreted inconsistently by practitioners. This may lead to variability in risk scores across assessors and reduced comparability between different sites or projects. Such subjectivity hinders generalization across regions or infrastructure types under diverse extreme weather regimes. Furthermore, the lack of standardization in KPIs among different stakeholders means results cannot easily be aggregated for broader policy or regional adaptation planning. In light of this, the extended RAMSSHEEP methodology can provide added value as part of a broader risk assessment strategy, integrating a multi-criteria decision support framework with explicit performance metrics. This combination may help bridge the gap between detailed asset-level assessments and broader climate adaptation planning.

6. Conclusions

In this contribution, a comprehensive framework for assessing the resilience of alpine infrastructure areas, leveraging the RAMSSHEEP methodology, was presented. The step-by-step process integrates the effects of individual and combined grey protective measures and NbS on infrastructure performance in the face of different natural hazard scenarios.

The initial assessment of infrastructure performance established a baseline for the analysis of the impact of natural hazards and mitigation measures. The evaluation of grey infrastructure measures combined with NbS highlighted the added value of hybrid mitigation strategies, leading to risk reduction.

Integrating the results into risk matrices enabled clear visualization of hotspots across the RAMSSHEEP KPIs, enabling better understanding of devised solutions and facilitating stakeholder communication.

Scenario analyses provide valuable insight into the effectiveness of different mitigation strategies, emphasizing the relevance of forward-looking approaches to infrastructure resilience for a better decision-making process.

The methodology presented can go beyond its use as a strategic planning tool. Integrating the expanded RAMSSHEEP framework into existing local and national risk assessment systems and strategic planning tools with CAPEX and OPEX parameters can align risk assessment with financial planning and operational resilience. By balancing safety, cost, and operational priorities, the methodology allows for the assessment of the financial viability of NbS implementation, helping to reconcile trade-offs between infrastructure upgrades and ongoing maintenance in strategic planning. By incorporating RAMSSHEEP into these systems, organizations can create a unified approach, from risk assessment to financial planning, ensuring that resources are allocated to the most critical infrastructure.

Furthermore, integration with digital twin infrastructure systems and real-time monitoring systems has the potential to transform it into a dynamic operational decision-making mechanism. This combination creates a powerful feedback loop between the physical world, the virtual representation of the infrastructure, and risk management strategies, creating a “living” risk management system. This allows transportation authorities to move from periodic, static risk assessments to a continuous, predictive, and proactive approach, optimizing not only their capital and operating expenditures but also maximizing network resilience, safeguarding the health and safety of the community.

The presented evaluation process offers a practical decision-support tool for optimizing infrastructure performance and maintenance aimed at safeguarding critical infrastructure against evolving natural hazards. The findings advocate for a balanced, adaptive management strategy that leverages both engineered and NbS to enhance infrastructure resilience in the face of environmental changes and challenges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. and S.F.; methodology, S.F. and A.S.; validation, R.S., J.H., F.D.I., E.K. and M.O.; formal analysis, S.F.; investigation, S.F.; resources, S.F. and E.K.; data curation, S.F., A.S., E.K., M.O., R.S., J.H. and F.D.I.; writing—original draft preparation, S.F. and A.S.; writing—review and editing, S.F., E.K., M.O., R.S., J.H., F.D.I., A.B.-v.V., J.M. and A.S.; visualization, S.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

NATURE-DEMO (“Nature-Based Solutions for Demonstrating Climate-Resilient Critical Infrastructure”; https://www.nature-demo.eu/) is an innovation action funded under the European Union’s Horizon Europe Programme, Grant Agreement No. 101157448. This work was supported by FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, I.P., by project reference and DOI identifier https://doi.org/10.54499/PRT/BD/152848/2021.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yang, Y.; Liu, H.; Mostafavi, A.; Tatano, H. Review on modeling the societal impact of infrastructure disruptions due to disasters. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 257, 110879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggio, T.; Martini, M.; Bettella, F.; Agostino, V. Debris flow and debris flood hazard assessment in mountain catchments. Catena 2024, 245, 108338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquemart, M.; Weber, S.; Chiarle, M.; Chmiel, M.; Cicoira, A.; Corona, C.; Eckert, N.; Gaume, J.; Giacona, F.; Hirschberg, J.; et al. Detecting the impact of climate change on alpine mass movements in observational records from the European Alps. Earth Sci. Rev. 2024, 258, 104886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECLAC (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean). Manual Para la Evaluacíon del Impacto Socioeconómico y Ambiental de Los Desastres (Versíon Final) (LC/MEX/G.5; LC/L.1874); ECLAC Subregional Headquarters in Mexico: Mexico City, Mexico, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Yue, D.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Meng, X.; Xu, X. Coupling mechanism of the eco-geological environment in debris flow prone area: A case study of the Bailong River basin. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 955, 177230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Roux, E.; Evin, G.; Eckert, N.; Blanchet, J.; Morin, S. Elevation-dependent trends in extreme snowfall in the French Alps from 1959 to 2019. Cryosphere 2021, 15, 4335–4356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stipanovic, I.; Chatzi, E.; Limongelli, M.; Gavin, K.; Bukhsh, Z.A.; Palic, S.S.; Xenidis, Y.; Imam, B.; Anzlin, A.; Zanini, M.; et al. Performance Goals for Roadway Bridges of COST TU1406 (WG2 Technical Report); s.l.: COST TU1406; Boutik.pt: Braga, Portugal, 2017; Available online: https://eurostruct.org/repository/tu1406_wg2.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Bruneau, M.; Chang, S.E.; Eguchi, R.T.; Lee, G.C.; O’Rourke, T.D.; Reinhorn, A.M.; Shinozuka, M.; Tierney, K.; Wallace, W.A.; von Winterfeldt, D. A Framework to Quantitatively Assess and Enhance the Seismic Resilience of Communities. Earthq. Spectra 2003, 19, 733–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, M.; Dueñas-Osorio, L. Multi-dimensional hurricane resilience assessment of electric power systems. Struct. Saf. 2014, 48, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panteli, M.; Mancarella, P. Influence of extreme weather and climate change on the resilience of power systems: Impacts and possible mitigation strategies. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2015, 127, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimellaro, G.P.; Renschler, C.; Reinhorn, A.M.; Arendt, L. PEOPLES: A Framework for Evaluating Resilience. J. Struct. Eng. 2016, 142, 04016063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linkov, I.; Fox-Lent, C.; Read, L.; Allen, C.R.; Arnott, J.C.; Bellini, E.; Coaffee, J.; Florin, M.V.; Hatfield, K.; Hyde, I.; et al. Tiered Approach to Resilience Assessment. Risk Anal. 2018, 38, 1772–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renschler, C.S.; Frazier, A.E.; Arendt, L.A.; Cimellaro, G.P.; Reinhorn, A.M.; Bruneau, M. Developing the ‘PEOPLES’ resilience framework for defining and measuring disaster resilience at the community scale. In Proceedings of the 9th U.S. National and 10th Canadian Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Toronto, ON, Canada, 25–29 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- America’s Cyber Defense Agency. Available online: https://www.cisa.gov/resources-tools/resources/infrastructure-resilience-planning-framework-irpf (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Pursiainen, C.; Rød, B.; Baker, G.; Honfi, D.; Lange, D. Critical infrastructure resilience index. In Risk, Reliability and Safety: Innovating Theory and Practice; Walls, L., Revie, M., Bedford, T., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-138-02997-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, W. RAMSSHEEP Analysis: A Tool for Risk-Driven Maintenance—Applied for Primary Flood Defence Systems in the Netherlands. Master’s Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, W.; van Gelder, P.H.A.J.M. Applying RAMSSHEEP analysis for risk-driven maintenance. In Safety, Reliability and Risk Analysis: Beyond the Horizon: Proceedings of the European Safety and Reliability Conference, ESREL 2013; Steenbergen, R.D.J.M., van Gelder, P.H.A.J.M., Miraglia, S., Vrouwenvelder, A.C.W.M., Eds.; CRC Press: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 703–713. [Google Scholar]

- Hackhofer, E. Analyse der Sedimentdynamik im Wildbach Lattenbach auf Basis digitaler Fernerkundung und Photogrammetrie. Master’s Thesis, The University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences (BOKU), Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Huebl, J.; Kaitna, R. Monitoring Debris-Flow Surges and Triggering Rainfall at the Lattenbach Creek, Austria. Environ. Eng. Geosci. 2021, 27, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajdin, R.; Kušar, M.; Mašović, S.; Linneberg, P.; Amado, J.; Tanasić, N. Establishment of a Quality Control Plan of COST TU1406 (WG3 Technical Report); s.l.: COST TU1406; Boutik.pt: Braga, Portugal, 2018; Available online: https://eurostruct.org/repository/tu1406_wg3_digital_vf.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.