Abstract

The accelerated carbonation of fresh concrete and recycled aggregates is one of the safest methods of CO2 sequestration as it mineralizes CO2, preventing its escape into the atmosphere. CO2 injection during batching of concrete improves its strength and may partially replace Portland cement, as with supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs). The curing of concrete by incorporation of CO2 also accelerates early strength development, which may enable early stripping of formwork/moulds for precast and in situ construction. The carbonation process may also be used for the beneficiation of recycled aggregates sourced from demolition waste. The CO2 mineralization technique may also be used for producing low-carbon, carbon-neutral, or carbon-negative concrete constituents via the carbonation of mineral feedstock, including industrial wastes like steel slag, mine tailings, or raw quarried minerals. This research paper analyses various available technologies for CO2 storage in concrete, CO2 curing and mixing of concrete, and CO2 injection for improving the properties of recycled aggregates. Carbon dioxide can be incorporated into concrete both through reaction with hydrating cement and through incorporation in recycled aggregates, giving a product of similar properties to concrete made from virgin materials. In this contribution we explore the various methodologies available to incorporate CO2 in both hydrating cement and recycled aggregates and develop a protocol for best practice. We find that the loss of concrete strength due to the incorporation of recycled aggregates can be mitigated by CO2 curing of the aggregates and the hydrating concrete, giving no negative strength consequences and sequestering around 30 kg of CO2 per cubic metre of concrete.

1. Introduction

Global warming poses a serious threat to the existence of humankind. Global warming is directly linked to climate change caused by greenhouse gas (GHG) emission. GHGs include carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O), with CO2 being the dominant greenhouse gas. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) cumulative CO2 emission data shows a near linear relationship with global warming [1]. The Paris agreement commits signatories to limit global warming to well below 2 °C, preferably 1.5 °C, compared to pre-industrial levels [2]. In 2024, the global CO2 emission was 38.60 billion tonnes (bt), and 386.73 million tonnes (Mt) for Australia. Australia’s per capita CO2 emission is 14.48 tonnes (t), which is approximately three times the world’s per capita CO2 emission of 4.72 t [3]. Australian construction industry is responsible for approximately 18% of total greenhouse gas emissions [4]. Therefore, decarbonization of this sector needs to be prioritised to achieve Australia’s Net Zero goal by 2050. Approximately 29 million m3 of concrete is used per year in Australia, with a total embodied carbon (EC) of approximately 12 Mt CO2e. A concrete mix typically consists of 12% to 15% of Portland cement (PC), which is responsible for approximately 90% of concrete’s embodied carbon (EC). The decarbonization of cement and concrete, therefore, needs to be prioritised for the decarbonization of construction industry.

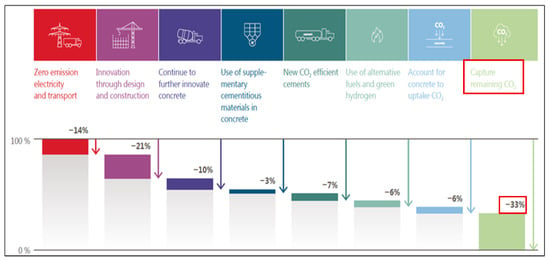

Figure 1 presents the decarbonization pathways for the Australian cement and concrete sector recommended by Verein Deutscher Zementwerke (VDZ) [5]. This study shows that decarbonization of cement and concrete can be achieved by decarbonizing electricity and transport (14% reduction in CO2 footprint), use of alternative fuels (6% reduction in CO2 footprint), innovation in concrete and cement technology (20% reduction in CO2 footprint), innovation in design and construction (21% reduction in CO2 footprint), carbon capture (33% reduction in CO2 footprint), and accounting for concrete re-carbonation (6% reduction in CO2 footprint). This study envisages that carbon capture will be essential for decarbonization of the cement and concrete industry.

Figure 1.

Decarbonization pathways for the Australian cement and concrete sector, CO2 capture estimate is highlighted with ‘Red box’. (reproduced from Reference [5], permission from SmartCrete CRC, 2025).

CO2 may be captured and stored permanently in concrete and recycled aggregates by chemically reacting with hydrating oxides and producing stable carbonates. This research paper analyses the following technologies currently under development and trialling and proposes a methodology for integrating them with low-carbon concrete (LCC) production technologies to further lower the EC for improving sustainability.

- CO2 storage in concrete for sustainability;

- CO2 used for concrete curing and mixing;

- CO2 injection for improving properties of recycled aggregates.

2. Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Recycling in Concrete

2.1. CO2 Storage in Concrete for Sustainability

2.1.1. CO2 Mineralization

Mineral carbonation is one of the safest methods for the sequestration of CO2 as it prevents the escape of CO2 to the atmosphere for long periods of time. Ex situ carbonation involves the carbonation of pretreated feedstock above ground (e.g., in a plant) to produce a value-added material for specific use. The carbonation process involves initial dissolution of both the carbon dioxide and the metal ions, which subsequently react to form carbonates (e.g., MgCO3, CaCO3). Owing to their high alkalinity, cementitious material waste stream materials commonly used as supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs), including steel slags and fly ashes, are valuable carbonation feedstocks. The concrete carbonation process can be carried out on both cement slurry (i.e., the solution with water and cementitious binder) or fresh concrete, which includes additives and aggregates. The carbonation processes involve hydrated gel (portlandite and C-S-H), ettringite, and un-hydrated phases, and affect the final composition of the hardened material and the strength development due to the hydration process [6].

Accelerated carbonation curing is the most widely used method to store CO2 in cement-based materials. In this method, the fresh cement or concrete mix (within a few hours after mixing) is subjected to a carbonation reaction. CO2 storage in concrete due to accelerated carbonation curing depends on the free lime content of the cementitious binder system including Portland cement and supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) such as GGBFS, fly ash, and glass powder. Other factors, including particle size distributions and moisture contents, also affect the CO2 storage capacity. The maximum amount of CO2 that can be stored in cement-based materials depends on the chemical composition of the cement. The Steinour formula, as given in Equation (1), may be used for estimating the maximum amount of CO2 that can be stored in cement-based materials [7].

where CaO, SO3, MgO, Na2O, and K2O are the mass percentages of relevant constituent oxides.

The carbonation reaction products are a hybrid of calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) and calcium carbonate (CaCO3). High early strength can be obtained from a few minutes to a few hours. The carbonation reaction occurring in hardened concrete is usually considered detrimental because calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) is decomposed, reducing the concrete strength. However, if carbonation takes place at an early stage, it could be beneficial for CO2 utilisation and performance (mechanical strength and durability properties) improvement [8].

Approximately 100 kg slag/ton of steel is produced during the steel-making process. Steel slag mainly consists of CaO-SiO, CaO-MgO-SiO2, and Fe2O3 phases. Steel slag is not commonly used as an SCM because it does not show hydraulic behaviour and has high free lime content. It is reported that the carbonation activation of steel slag is required before using it as an SCM. When steel slag is carbonated by exposing slag panels to 99.5% pure CO2 gas at the ambient temperature and 0.15 MPa pressure for a duration of 2 to 24 h, the average CO2 uptake has been reported to be 3.4% in 2 h carbonation and 4.6% in 24 h carbonation. One kilo of basic oxygen furnace slag can capture up to 215 g of carbon dioxide [9].

This implies that by adding CO2 sourced from the flue gases, the industry wastes or raw materials may be upcycled to carbonate and silicate materials. These materials may be used to produce low-carbon concrete and manufacturing of low-carbon industrial products. In addition, by adding CO2 at an early stage, the performance of concrete may be improved.

2.1.2. MCi Mineral Carbonation Process

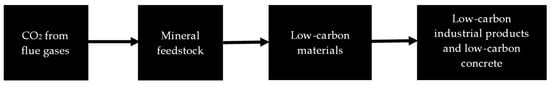

In Australia, MCi Carbon has developed a mineral carbonation process which combines CO2 captured from flue gases with a mineral feedstock, including industrial wastes like steel slag, mine tailings, or raw quarried minerals, to produce magnesium carbonate, calcium carbonate, and amorphous silica. MCi Carbon has established a pilot plant in Newcastle for the upcycling of industrial waste. A conceptual process of MCi materials beneficiation, as described on the MCi Carbon website [10], is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

MCi process for abatement of CO2 and upcycling of industrial wastes.

The low-carbon carbonate materials may be used for the manufacturing of products including paper, glass, plastics, and paint. However, the silicates (amorphous silica) may be used as a supplementary cementitious material (SCM) which can deliver comparable mechanical performance at lower replacement levels, such as 10% replacement. It will have the potential to achieve the same embodied carbon reduction as a FA substitution greater than 10%, enabling concrete producers to minimise clinker use without compromising target strengths [11].

2.2. Use of CO2 for Concrete Curing and Mixing

2.2.1. CO2 Curing Process

Curing freshly cast concrete allows for rapid cement hydration, which improves early-age performance and durability properties. CO2 curing of fresh concrete may be used on a standalone basis or in conjunction with water curing. This not only enables the storage of CO2 as a solid calcium carbonate phase in concrete but also accelerates the curing process and improves the mechanical properties. The conceptual CO2 curing process flow is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Conceptual process flow for CO2 curing process.

During CO2 curing, calcium silicate hydration generates a mixture of calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) and calcium carbonate (CaCO3), instead of only C-S-H, which is generated during the normal hydration process. The rapid generation of C-S-H is responsible for early strength generation. CO2 curing of concrete is an exothermic process and it results in a compressive strength growth rate similar to that of elevated temperature curing, while being more sustainable. CO2 curing reduces permeability and improves the freeze–thaw, chloride, and sulphate resistance of concrete. CO2 curing reduces the alkalinity of concrete, increasing the vulnerability of embedded steel reinforcement to corrosion [12]. CO2 curing is generally undertaken in a pressurised curing chamber. CO2 is injected into the chamber, and the gas pressure is maintained at 0.2 MPa, for example, for a duration of 3 h to 28 days. CO2 curing may be followed by water curing. It is reported that the compressive strength of carbonated concrete increases significantly with dry curing. However, if CO2 curing is followed by water curing, the 1-day compressive strength of concrete increases further, by 30% [13]. The use of CO2 during batching and CO2 curing of concrete are already being trialled. An overview of the technology developed by Solidia Technologies and CarbonCure is included here.

2.2.2. Solidia Low-Carbon Cement and CO2 Curing Technology

Solidia Technologies [14] has developed Solidia Cement™, which is a non-hydraulic cement composed of low-lime-containing calcium silicate phases, such as wollastonite/pseudowollastonite (CaO.SiO2) and rankinite (3CaO.2SiO2). Solidia cement clinker is produced at 1200 °C (PC clinker is produced at 1450 °C) and has a carbon footprint 30% lower than that of PC [15]. Solidia cement uses approximately 50% limestone, compared to the 70% required by PC. It is reported that Solidia cement consists of 46.6% of CaO, 47.9% of SiO2, 2.6% of Al2O3, 0.8% of Fe2O3, 0.8% of MgO, 0.4 of Na2O, 0.7 of K2O, and 0.2 of SO3.

This cement sets and hardens by a reaction between CO2 and the calcium silicates (in the presence of water), locking CO2 permanently. During the carbonation process, calcite (CaCO3) and silica (SiO2) are formed as per the chemical reactions given below, which are responsible for the strength development in concrete [15,16].

CaO.SiO2 + CO2 + H2O → CaCO3 + SiO2 + H2O

3CaO.2SiO2 + 3CO2 + H2O → 3CaCO3 + 2SiO2 + H2O

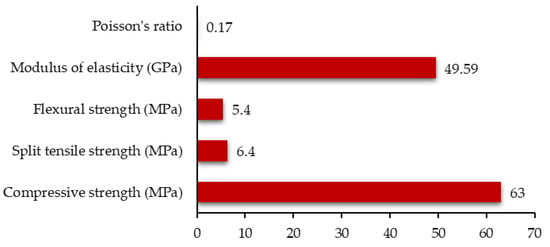

CO2 used during the curing process needs to be pressurised, which makes it more relevant for precast concrete applications. The mechanical properties of Solidia cement concrete comprising 350 Kg/m3 of Solidia cement, 821 Kg/m3 of sand, 9.5 mm aggregate 414 Kg/m3, 19 mm aggregate 737 Kg/m3, water 136 Kg/m3, and admixtures (high-range water reducer @ 4 mL/Kg of cement, air-entraining admixture @ 3 mL/kg of cement, and set retarding admixture @ 5 mL/kg of cement), as reported by Sahu et al. [16], are presented in Figure 4. This figure shows that the performance of Solidia cement concrete is similar to that of PC concrete. Sahu et al. [16] also reported that Solidia cement concrete demonstrated equivalent or better freezing-and-thawing, alkali–silica reaction (ASR), and sulphate resistance compared to PC concrete.

Figure 4.

Typical mechanical properties of Solidia cement concrete (Source: Data extracted from reference [16]).

Solidia cement concrete can develop full strength in 1 day, and therefore can also increase precast production output significantly. Solidia Concrete™ products are more durable and have a wider colour palette and no efflorescence. Unreinforced precast concrete products such as pavers or blocks produced with Solidia Cement™ and cured with CO2 reduce its carbon footprint by 60% (30% due to the use of Solidia cement and 30% due to CO2 curing). These unreinforced precast products can be produced in traditional precast factories with a 24 h production cycle time. Solidia cement can be produced in existing rotary kilns with minor adjustments, removing barriers to its adoption. This technology is being trialled via pilot projects in collaboration with cement producers including LafargeHolcim, and may potentially be trialled in other places around the world [17,18].

2.2.3. CarbonCure Technology

CarbonCure [19] has developed CO2 sequestration technology that involves the addition of an optimum dose of liquid CO2 to ready-mixed concrete during the batching process. This results in the formation of mineralized calcium carbonate (CaCO3) due to the reaction of CO2 with calcium carbonate and calcium silicate hydrate gel (formed during the hydration of Portland cement), storing the CO2 permanently in the concrete. The process flow is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

CarbonCure process for abatement of CO2 and concrete strength improvement.

Monkman et al. [20] reported that the addition of CO2 @ 0.06% by weight of cement to a ternary concrete mix (design 28 days compressive strength of 48.2 MPa) comprising cement (50%), slag (37%), and fly ash (13%) resulted in a cement reduction of 55 kg/m3 (20%) for similar mechanical properties of concrete. CO2 addition resulted in 1% and 3% greater compressive strength than that of the control mix at 7 days and 28 days, respectively. This example mix resulted in a reduction of 142 g/m3 of atmospheric CO2 and 49.8 Kg/m3 of embodied carbon reduction. The carbon footprint of enabling works, capture and liquefaction of CO2, pipeline transportation, and tanker transport was estimated to be 31.7 Kg/t.km and 0.38 Kg/t.km. This technology provides dual benefit, namely, it enables the recycling of CO2 sourced from flue gases and the partial replacement of PC in concrete mixes, functioning as an SCM. The technology was used in the production of concrete used in a 34,000 m2 (36,000 m3 concrete) mid-rise office tower at 725 Ponce de Leon Avenue NE in Atlanta, Georgia, in the United States.

2.3. CO2 Injection for Improving Properties of Recycled Aggregates

In 2022–2023, 29.2 Mt from the construction and demolition (C & D) stream (39% of the total) was generated in Australia, which included 27 Mt of building and demolition materials including asphalt, bricks, concrete, and pavers; ceramics, tiles, and pottery; plasterboard and cement sheeting; uncontaminated soil, sand and rock; rubble, etc. The estimated resource recovery for building and demolition materials was 84%. In total, 4.6 Mt of building and demolition materials was disposed in landfill [21,22].

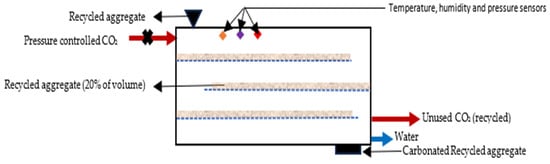

The properties of recycled aggregate (RA) are typically inferior to those of natural aggregates due to the existence of adhered old mortar and multiple interfacial transition zones (ITZs) of RA. It is reported that the fresh, mechanical, and durability properties of recycled aggregate concrete (RAC) are inferior to those of concrete with virgin aggregates with the same water binder ratio. The adhered old mortar on RA is generally removed by mechanical treatment, including mechanical grinding, heating, and pre-soaking in acid solution. This mechanical treatment may induce micro-cracks in the RA, which adversely affect the properties of RAC. To mitigate this issue, the accelerated carbonation technique is used for improving the properties of RA. CO2 gas curing of RA enhances the properties of the adhered old mortar and the ITZ. In this process, CO2 gas penetrates adhered mortar via pores and cracks, and reacts with the primary hydration products, producing CaCO3 and silica gel, enhancing the strength of the adhered old mortar of RA. CO2 curing of RA is generally undertaken in a carbonation chamber at a relative humidity (RH) of 50%, a temperature of 25 °C, and a pressure of 0.5 to 0.6 bar [23]. The compressive strength of RCA depends on the CO2 exposure time of the RA and the proportion of RA in the concrete mix. Pu et al. [24] reported that the carbonation occurs rapidly to 17.65% (62% of total carbonation) in first 0.5 h; then, carbonation occurs at a slower rate of 2.9% per hour up to 3 h from the commencement of the process. After 3 h, carbonation stabilises and continues for a long period of time. This finding may be used for designing an efficient RA carbonation process, allowing for a minimum 0.5 h exposure time. A conceptual RA carbonation setup is presented in Figure 6. For efficient performance, the volume of RA should be approximately 20% of the carbonation chamber volume to maximise the high contact between RA and CO2. The concentration of CO2 in the gas mix should be minimum 20% for an optimum carbonation. This threshold allows for selecting industrial flue gas that can be used with minimum processing. The carbonation of RA requires a continuous supply of CO2, so the RA carbonation plant should be located close to an industrial or power plant emiting CO2 to minimise transportation costs and CO2 emission.

Figure 6.

Conceptual system design for recycled aggregate carbonation.

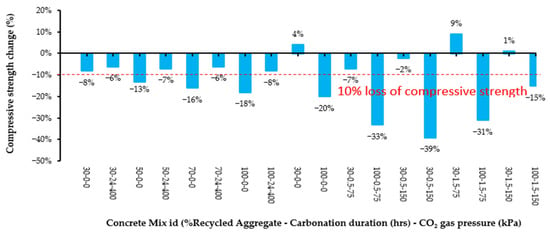

The effect of carbonation treatment parameters, % RA in aggregate, CO2 gas pressure, and exposure time on compressive strength is presented in Figure 7. It may be seen from this that the carbonation treatment of recycled aggregates provides RAC mixes incorporating up to 70% RA with a compressive strength of ±10% of that of concrete with 100% virgin aggregate.

Figure 7.

Effect of carbonation treatment and recycled aggregate proportion on compressive strength (Source: data extracted from reference [25]).

Pan et al. [26] reported that for optimal CO2 curing results, the CaOH (CH) pretreatment should be carried out with a 0.01–0.05 mol/kg CH solution, a CO2 concentration of 70%, and a moisture content of 5%. After the CO2 curing process, the powder content of the recycled fine aggregates (RFAs) decreased from 14.2% to 9.1%, the water absorption decreased from 4.35% to 1.65%, and the crush value decreased from 18% to 13%. In addition, the water-demand ratio of the cured RFAs decreased from 1.17 to 1.10, and the compressive-strength ratio increased from 0.95 to 1.04.

Shi et al. [27] reported that CO2 curing increases the apparent density of RA by 5.6–7.8%. The post-CO2 curing apparent density was only 1.5–2.6% lower than that of the natural aggregate. Generally, the drying shrinkage of RAC is higher than that of natural aggregate concrete (NAC), and it increases with an increase in RA content. However, carbonation treatment reduces the dry shrinkage of RAC by 8–13% [23].

It is expected that carbonation would lower the alkalinity of concrete, which may reduce the pH of concrete, increasing the susceptibility of embedded steel to corrosion. However, in the carbonation process, CO2 penetrates the loosely attached mortar of RAs through the pores or cracks, and dissolves in the pore water, producing carbonic acid (H2CO3). The CO3 ions released from H2CO3 react with calcium ions from the hydration of PC, producing carbonate (CaCO3) and silica gel, which fill the cracks, improving the microstructure and reducing the porosity, increasing the resistance to the penetration of detrimental ions into the concrete. This mitigates the corrosion risk of embedded reinforcement to some extent. Liang et al. [23] reported that the chloride diffusion coefficient of concrete with carbonated RA decreased by 41–46% compared with that with RA. The carbonation depth of concrete with carbonated RA decreased by approximately 20% to 29% compared with that with RA.

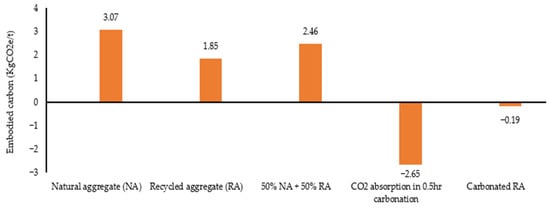

During the natural carbonation process, one ton of RA can absorb 11–20 kg of CO2 [23]. This implies that the embodied carbon of naturally carbonated RA is approximately −15 KgCO2e/t if no preprocessing is undertaken. Assuming accelerated carbonation will be able to achieve CO2 absorption equivalent to that by natural carbonation over a long period of time, the estimated embodied carbon of carbonated RA (excluding carbon footprint associated with carbonation system building) for 0.5 h carbonation (17.65% of total carbonation) is presented in Figure 8. This figure shows that the carbonation of RA makes the aggregates more or less carbon-neutral when carbon emissions relating to CO2 processing and transport are added. The embodied carbon of carbonated RA concrete may be carbon-negative when its cured with CO2 (due to reduction in binder quantity and CO2 absorption).

Figure 8.

Estimated embodied carbon of 0.5 h carbonated recycled aggregate (Source: Data extracted from references [23,24,28]).

3. Limitations and Challenges

Despite the significant potential of CO2 mineralisation, carbonation curing, and recycled aggregate (RA) beneficiation for reducing the embodied carbon of concrete, there exist several limitations and implementation challenges.

3.1. Availability, Purity, and Logistics of CO2 Supply

The feasibility of CO2 utilisation in concrete depends on access to a reliable CO2 stream and the infrastructure required for capture, conditioning, compression, storage, and distribution. While sectoral roadmaps indicate that carbon capture is expected to play a substantial role in decarbonising the cement and concrete industry, deployment at scale remains contingent on broader industrial CCS buildout and associated logistics [5]. In addition, the performance of carbonation-based processes can be sensitive to CO2 concentration, moisture, and processing conditions, so variability in CO2 supply and handling can translate into variability in uptake and performance [6,8,12,13].

3.2. Variability in Carbonation Capacity and Kinetics

The maximum CO2 uptake in cementitious systems is constrained by reactive oxide availability (primarily CaO and MgO), but realised uptake is governed by kinetics and transport (e.g., moisture content, particle size distribution, and diffusion) [6,7,8]. Consequently, theoretical capacity estimates (e.g., using oxide-based formulae) may overpredict achievable uptake under practical curing or treatment timeframes [7,8]. Similar constraints apply to RA carbonation, where CO2 ingress and reaction depend on pore structure and adhered mortar characteristics, which vary widely across sources [24,25,26,27].

3.3. Durability and Reinforcement Corrosion Risks

While early-age carbonation curing can improve early strength and reduce permeability, carbonation reduces alkalinity, which may increase the vulnerability of embedded reinforcement to corrosion if carbonation depth approaches the steel cover zone [12]. This consideration tends to make CO2 curing most straightforward for non-reinforced or lightly reinforced precast elements or concrete reinforced with non-ferrous reinforcement, unless combined curing regimes or additional durability design measures are applied [12,13]. Long-term durability under representative exposure conditions (chlorides, cyclic wetting/drying, carbonation progression) requires further field validation to support broader structural uptake [12,13].

3.4. Recycled Aggregate Quality and Consistency

RA properties are inherently variable due to differences in parent concrete strength, demolition/processing methods, adhered mortar content, and contamination. Although accelerated carbonation can improve RA density and reduce water absorption, the magnitude of improvement and its translation into concrete performance depends strongly on the specific RA stream and treatment protocol [24,26,27]. Studies reporting strength recovery and shrinkage reductions following carbonation treatment are promising, but achieving consistent performance at scale will require robust quality control and specification frameworks [24,27].

3.5. Energy Demand, Throughput, and Economic Viability

Accelerated carbonation processes commonly require controlled environments (CO2 concentration, humidity, and sometimes pressure) and sufficient residence time to achieve meaningful uptake and performance gains [12,13,24]. These requirements imply added infrastructure and operational complexity that can affect throughput and cost—especially in ready-mix contexts where curing chambers are less readily integrated than in precast production [12,13]. The overall cost–benefit also depends on how much clinker can be displaced (e.g., through strength gains enabling cement reduction) and the achievable uptake per m3 under real production constraints [20].

3.6. Standards, Codes, and Industry Adoption

Even where laboratory and pilot results are positive, widespread adoption depends on acceptance pathways within standards, performance verification, and risk management. Roadmaps highlight that carbon capture and technology innovation are essential components of sector decarbonisation, but translating emerging CO2 utilisation approaches into routine practice will require consistent test protocols and evidence bases that satisfy regulators and industry stakeholders [5]. This is particularly important for structural applications where durability and long-term performance must be demonstrated [12,13].

3.7. System Boundaries and LCA Uncertainty

Claims of “carbon-neutral” or “carbon-negative” concrete depend on system boundaries and assumptions regarding CO2 sourcing, capture energy, transport, and avoided burdens (e.g., cement reduction, landfill diversion). While mineral carbonation is generally considered a safe long-term storage pathway, the net benefit must account for the emissions associated with implementing the carbonation process and any additional processing steps [6,7,8,12,13,24]. Therefore, cradle-to-grave assessments are needed to quantify overall climate impact consistently across alternative decarbonisation levers [5].

4. Mitigation Strategy and Integrated Approach

A potential mitigation strategy could address the identified limitations by integrating multiple CO2 utilisation pathways across the concrete production lifecycle rather than relying on a single carbonation mechanism. Low-dosage CO2 injection during batching and short-duration curing reduces dependence on continuous high-purity CO2 supply while still delivering strength gains and enabling clinker reduction [12,13,20], consistent with sectoral decarbonisation roadmaps [5]. Carbonation treatment of recycled aggregates targets highly reactive adhered mortar, improving aggregate quality and interfacial transition zones and mitigating performance variability associated with high recycled aggregate contents [24,25,26,27]. Durability risks linked to early-age carbonation are reduced by limiting carbonation to controlled early stages and, where required, combining CO2 curing with subsequent water curing to preserve later-age hydration [12,13]. By combining cement reduction, recycled aggregate beneficiation, and permanent mineralisation of CO2 within existing precast and ready-mix infrastructure, the integrated approach enhances robustness, scalability, and the likelihood of achieving meaningful embodied carbon reductions at the system level [5,12,13,20].

Embedded steel corrosion is considered a major risk to the service life of reinforced concrete structures. To eliminate the corrosion risks for steel reinforcement due to carbonated RA and CO2 curing, carbonated concrete may be adopted for the construction of unreinforced concrete elements such as pavers and concrete elements reinforced with non-ferrous steel reinforcements such as glass fibre-reinforced polymer (GFRP) reinforcement. Carbonated RA and CO2 curing may also be used for low-risk concrete structures with as design life of 25 to 50 years designed according to AS 3600, including footpaths, cycleways, medians, safety barriers, drainage structures, etc. These infrastructures require 20 to 32 MPa concrete, which represent a significant portion (>50%) of the concrete supply. In Australia, transport authorities allow the controlled use of RA and carbonated RA. In October, 2023 a 1 m by 25 m section of the pathway at Transport for NSW’s Edmondson Park North Commuter Carpark in New South Wales (NSW) was installed by AW Edwards in collaboration with Holcim and Western Sydney University. In this installation, 50% carbonated RA was used. The carbonated RA was also trialled at Maidstone Tram Maintenance Facility, Victoria, Blacktown Animal Rehoming Centre, New South Wales, and Western Sydney University Hawkesbury Farm’s concrete slabs in similar low-risk concrete infrastucture in at-grade structures [29].

It is noted that further research is required to demonstrate the compliance of the performance of carbonated aggregates with Australian Standards, including AS 2758 (Aggregates and rock for engineering purposes), AS 3600 (Concrete structures), etc., for stimulating the adoption of carbonated RA. A long-term data set for carbonated RA is required to support lab-based measured and modelled data to demonstrate compliance of its properties with relevant standards, including design life (>60 years), degradation factor (>60), attrition resistance (Los Angeles value < 30–40%), sodium sulphate soundness (average material loss 6–12%), etc. The strength improvement effect of CO2 when added during mixing and curing stages needs to be included in the concrete standard, AS 3600.

5. Conclusions

We have examined the potential for reducing the embodied carbon of concrete through the integrated recycling of atmospheric and industrial carbon dioxide using carbonation-based technologies applied to cementitious systems and recycled aggregates. Mineral carbonation was shown to provide a safe and durable pathway for permanent CO2 storage through the formation of stable carbonate phases, while simultaneously enabling the valorisation of industrial by-products such as steel slag, mine tailings, and demolition waste. When used as supplementary cementitious materials or aggregate feedstocks, these carbonated materials can contribute to clinker reduction and landfill diversion.

We find that the use of CO2 during concrete batching and curing can deliver dual benefits, permanent mineralisation of CO2 and measurable improvements in early-age strength, enabling reductions in Portland cement content without compromising mechanical performance. Industrial examples such as CO2 injection during batching and carbonation curing of precast elements demonstrate that these approaches are already technically feasible within existing production infrastructure. However, durability considerations, particularly related to alkalinity reduction and reinforcement corrosion, necessitate controlled application and, in some cases, combined curing regimes.

Carbonation treatment of recycled aggregates was shown to significantly improve aggregate quality by densifying adhered mortar and enhancing interfacial transition zones. Evidence from the literature indicates that recycled aggregate concrete incorporating up to approximately 70% carbonated recycled aggregates can achieve compressive strengths within ±10% of those of equivalent natural aggregate concrete, while also reducing shrinkage and water demand. This provides a viable pathway for increasing recycled aggregate utilisation in structural and non-structural applications.

Importantly, we find that the greatest benefit arises from integrating these approaches rather than applying them singularly. Strength gains from CO2 injection during batching can partially offset performance losses associated with high recycled aggregate contents, while mineralisation of CO2 across multiple process stages reduces reliance on any single carbonation mechanism. This integrated strategy improves robustness against variability in CO2 supply, material composition, and processing conditions, and aligns with recommended decarbonisation pathways for the cement and concrete sector.

While the potential for embodied carbon reduction is substantial, realising these benefits at scale will require further work to address CO2 supply logistics, energy demand, standardisation, and lifecycle assessment uncertainties. Future research should focus on validated mix-design case studies, cradle-to-grave carbon accounting, and performance-based standards development to support wider industry adoption. Overall, the integrated CO2 recycling framework presented in this paper provides a pragmatic and scalable pathway toward low-carbon concrete consistent with net-zero objectives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, data collection and analysis, data curation, and writing—original draft preparation, H.K.S.; writing—review and editing and supervision, S.M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study. The data used for analysis in this study has been sourced from the literature cited as references. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Working Group II—IPCC. IPCC_AR6_WGII_SummaryForPolicymakers. 2021. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_SPM_Stand_Alone.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2022).

- UNFCCC and United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Adoption of the Paris Agreement—Paris Agreement Text English. 2015. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2022).

- Ritchie, R.; Max, R.; Pablo, R. Our World in Data. CO2 and Greenhouse Gas Emission. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/co2/country/australia (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Yu, M.; Wiedmann, T.; Crawford, R.; Tait, C. The Carbon Footprint of Australia’s Construction Sector. Procedia Eng. 2017, 180, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VDZ. Decarbonisation Pathways for the Australian Cement and Concrete Sector. 2021. Available online: https://www.ccaa.com.au (accessed on 30 July 2022).

- Davolio, M.; Muciaccia, G.; Ferrara, L. Concrete carbon mixing—A systematic review on the processes and their effects on the material performance. Clean. Mater. 2025, 15, 100292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, W. Carbonation of cement-based materials: Challenges and opportunities. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 120, 558–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; El-Hassan, H. CO2 Utilization in Concrete. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Sustainable Construction Materials and Technologies (SCMT3), Kyoto, Japan, 18–22 August 2013; Available online: http://www.claisse.info/Proceedings.htm (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- MCi Carbon. Available online: https://mcicarbon.com/technology (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Jiayi, F.; Louise, K.; Kirk, V.; Paul, T.; Mann, J. Preliminary Study of Carbon-Neutral Amorphous Silicate via Mineral Carbonation as a Sustainable SCM for Concrete. In Proceedings of the Concrete 2025 Proceeding, Adelaide, Australia, 7–10 September 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoutian, M.; Shao, Y. Production of cement-free construction blocks from industry wastes. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 1339–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Ghouleh, Z.; Shao, Y. Review on carbonation curing of cement-based materials. J. CO2 Util. 2017, 21, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Shi, C.; Tu, Z.; Poon, C.S.; Zhang, J. Effect of further water curing on compressive strength and microstructure of CO2-cured concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 72, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solidia Technologies. Available online: https://assets.ctfassets.net/jv4d7wct8mc0/5DwEAeEYqsFAYA9UC53EF7/4f8b7566221a8d9cb38f970867003226/Solidia_Science_Backgrounder_11.21.19__5_pdf (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Decristofaro, N.; Sahu, S. CO2-Reducing Cement. World Cement. 2014. Available online: https://assets.ctfassets.net/jv4d7wct8mc0/2GLZRAD0IdwCDjHYvBgKh9/5b7db2442628571965323c1ed759e9e4/World-Cement-Article.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2026).

- Sahu, S.; Meininger, R.C. Sustainability and Durability of Solidia Cement Concrete. Concr. Int. 2020, 42, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LafargeHolcim. Low-Carbon_Construction_Solidia_CO2_Curing. Available online: https://www.holcim.com/sites/holcim/files/documents/low-carbon_construction_solidia_co2_curing.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2026).

- Atom333. Solidia Technologies: Reinventing Cement to Slash Concrete’s Carbon Footprint. Available online: https://www.materialfuture.com/solidia-technologies-reinventing-cement-to-slash-concretes-carbon-footprint/ (accessed on 8 January 2026).

- CarbonCure. Available online: https://www.carboncure.com/ (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Monkman, S. Utilization of CO2 in Ready Mixed Concrete Production: A Project Case Study. In Proceedings of the Concrete Institute of Australia’s Biennial National Conference 2021, Online, 5–8 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pickin, J.; Macklin, J. National Waste and Resource Recovery Report 2024. Available online: www.blueenvironment.com.au (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Maqsood, T.; Shooshtarian, S.; Peter, S.P.; Wong, R.; Yang, J.; Khalfan, M. Construction and Demolition Waste Management in Australia. April 2020. Available online: https://www.rmit.edu.au/content/dam/rmit/au/en/about/schools-colleges/property-construction/construction-waste-lab/construction-and-demolition-waste-management-in-australia.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Liang, C.; Pan, B.; Ma, Z.; He, Z.; Duan, Z. Utilization of CO2 curing to enhance the properties of recycled aggregate and prepared concrete: A review. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 105, 103446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, Q.; Shi, X.; Luan, C.; Zhang, G.; Fu, L.; El-Fatah Abomohra, A. Accelerated carbonation technology for enhanced treatment of recycled concrete aggregates: A state-of-the-art review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 282, 122671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, V.W.Y.; Butera, A.; Le, K.N.; Li, W. Utilising CO2 technologies for recycled aggregate concrete: A critical review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 250, 118903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.; Zhan, M.; Fu, M.; Wang, Y.; Lu, X. Effect of CO2 curing on demolition recycled fine aggregates enhanced by calcium hydroxide pre-soaking. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 154, 810–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Wu, Z.; Cao, Z.; Ling, T.C.; Zheng, J. Performance of mortar prepared with recycled concrete aggregate enhanced by CO2 and pozzolan slurry. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2018, 86, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bampanis, I.; Vasilatos, C. Recycling Concrete to Aggregates. Implications on CO2 Footprint. Mater. Proc. 2023, 15, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CO2 Concrete. Available online: https://www.co2concrete.com.au (accessed on 11 January 2026).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.