Abstract

The Hisayamada Dam (22.5 m high, 75.4 m long), constructed in 1924 as a water supply facility, is a masonry arch–gravity concrete dam with a slender arch shape. Although it was the first theoretically designed arch-type dam in Japan, seismic forces were not considered at the time of construction. This study evaluates its seismic performance using a three-dimensional (3D) dynamic Finite Element Method (FEM) in accordance with current Japanese governmental guidelines. A detailed 3D model incorporating the dam body, surrounding topography, foundation, and reservoir was developed, and expected earthquake motions in three directions were applied simultaneously. The analysis showed that localized tensile stress exceeding the tensile strength occurred near the upstream heel of the dam base. However, these stress concentrations were limited to small regions and did not form continuous damage paths across the dam body. Based on the linear dynamic analysis and engineering judgment, the overall structural integrity and water storage function of the dam are considered to be maintained. Additional analyses were conducted by varying the elastic modulus of the foundation rock and dam concrete to clarify the influence of material stiffness on seismic response and stability.

1. Introduction

Recent progress in computational mechanics and earthquake engineering has enabled detailed evaluation of the seismic safety of concrete dams using the finite element method (FEM). Numerous studies have investigated the dynamic behavior of dams subjected to strong ground motions to clarify stress distribution, cracking mechanisms, and stability characteristics.

The seismic performance of concrete gravity dams has been extensively examined using two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) FEM models. Early linear dynamic studies by Chopra and Chakrabarti (1972) [1] and Clough and Chopra (1965) [2] established the fundamental framework for analyzing dam–reservoir systems. Subsequent research introduced nonlinear constitutive models to simulate tensile cracking, uplift, and sliding behavior along the dam–foundation interface [3]. More recent developments include advanced nonlinear analyses and extended FEM (XFEM) to represent crack initiation and propagation under strong ground motions [4]. In Japan and other seismically active regions, dynamic 2D FEM analysis is widely adopted according to the national guidelines [5]. However, 2D models cannot fully reproduce three-dimensional effects, such as abutment restraint, foundation–reservoir interaction, and spatially varying responses. Therefore, several studies have employed 3D FEM to improve the accuracy of seismic stress and deformation assessment for gravity dams.

Because of their curved geometry, arch dams inherently require 3D analysis to represent their complex load transfer and dynamic response. Significant contributions include the 3D hydrodynamic–structural interaction models developed by Fok and Chopra (1986) [6] and Hall and Chopra (1983) [7]. Recent nonlinear three-dimensional investigations have further demonstrated the importance of considering damage evolution, crack propagation mechanisms, and dam–foundation–reservoir interaction to accurately evaluate seismic vulnerability of concrete dams, including arch dams [8,9,10]. These studies consistently show that simplified 2D analysis tends to underestimate tensile stress, cracking potential, and asymmetric deformation near the abutments and crown cantilever.

The arch–gravity dam, a hybrid structure combining the weight stability of a gravity dam and the arch action of a curved configuration, has received comparatively less research attention. However, existing studies indicate that its seismic behavior cannot be captured adequately without full 3D evaluation. The ICOLD Benchmark Committee (2003) [11] reported that arch–gravity dams exhibit intermediate characteristics between pure gravity and pure arch dams. Investigations of historical arch–gravity dams have emphasized that material deterioration, heterogeneous concrete properties, construction joints, and foundation conditions significantly influence seismic performance [12,13,14]. These studies highlight the necessity of full 3D nonlinear analysis for evaluating the safety of early 20th-century arch–gravity dams.

In recent years, increasing attention has been paid to the seismic safety of existing and historical dams that were constructed without explicit seismic design considerations. Several studies published in Infrastructures have highlighted the challenges associated with assessing the seismic performance of aging dam structures, including uncertainties in material properties, limited monitoring data, and the applicability of numerical models [15,16,17,18]. Recent research has emphasized the importance of three-dimensional numerical modeling for evaluating the seismic response of existing concrete dams and arch–gravity dams, particularly in terms of stress redistribution, interaction with the foundation and reservoir, and the limitations of simplified two-dimensional approaches [16,17,18,19]. These studies indicate that engineering judgment, supported by advanced numerical analyses, remains a key component in the seismic safety verification of historical dam infrastructure.

In Japan, numerous early 20th-century masonry and concrete arch–gravity dams—including the Hisayamada Dam—were constructed without explicit seismic design considerations. Therefore, it is essential to assess their seismic safety under modern design ground motions using comprehensive 3D dynamic FEM analysis.

In this study, the seismic performance of the Hisayamada Dam, the first arch–gravity dam in Japan, is evaluated through a detailed 3D dynamic FEM model incorporating dam–foundation–reservoir interaction. The objective is to clarify its dynamic response characteristics under large inland and interplate earthquakes and to confirm its seismic stability based on current Japanese guidelines. Furthermore, the effects of arch geometry on stress distribution, damage localization, and water storage function are discussed.

2. Overview of the Hisayamada Dam

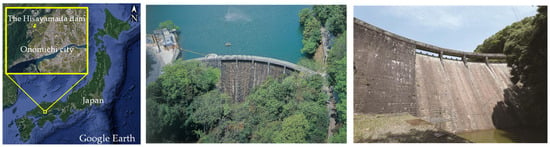

As shown in Figure 1, the Hisayamada Dam is a water supply dam located in Onomichi City, Hiroshima Prefecture, western Japan. The dam is an arch-shaped gravity concrete dam with a rough-stone masonry facing, in which mortar is filled between stones and the surface is covered with stone cladding. The dam was constructed in 1924 to address chronic water shortages caused by population growth in Onomichi City. The catchment area is 3.6 km2, and the total storage capacity is 720,000 m3. A semicircular intake tower is installed on the right bank of the dam body, while a free-overflow spillway without gates is located on the left bank side of the intake tower.

Figure 1.

Bird’s-eye view of the Hisayamada Dam and the downstream face of the dam as seen from the left and right banks.

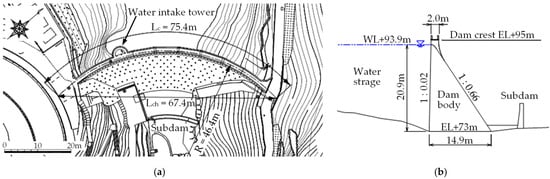

Figure 2 shows the plan view and a longitudinal cross-section in the upstream–downstream direction near the center of the dam. As shown in Figure 2a, the crest length (Lc) is 75.4 m, the chord length (Lch) is 67.4 m, and the radius of curvature (R) is 46.4 m. The dam height is 22.5 m, and the downstream face slope is 1:0.66, as illustrated in Figure 2b. This slope is steeper than that typically adopted for gravity dams, which generally ranges from approximately 1:0.7 to 1:0.8. The crest width is only 2 m, which is remarkably narrow, and the overflow section located at the center of the dam has a sharp geometry, resulting in an overall slender dam body. The dam exhibits a gentle arch configuration. Excluding small dams with a height of less than 15 m, the Hisayamada Dam is recognized as the first arch dam in Japan designed based on theoretical assumptions regarding arch action. However, at the time of its construction, seismic forces were not considered in the design.

Figure 2.

Geometry of the Hisayamada Dam: (a) plan view; (b) longitudinal cross-section.

The unconfined compressive strength of the mortar is 30 to 48 MPa, and that of the rough stone is 219 to 227 MPa, which is higher than the general level. There is no significant damage, deterioration, cracking, or leakage on the downstream face of the dam body. The results of the dam body boring and Lugeon water pressure tests also indicate no continuous cracks in the dam body. As shown by the dam body boring core, there are many rough stones of around 5 to 40 cm, but there are no cavities in the mortar, and there is no weathering at the boundary between the rough stones and the mortar. In addition, the joint surface between the dam body and the foundation bedrock is well adhered to, and there are no deteriorated areas that would cause problems for the stability of the dam body.

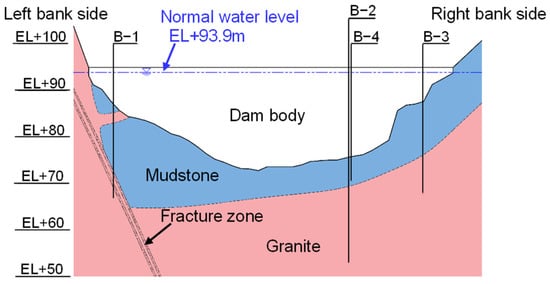

Figure 3 shows the geological cross section along the dam axis. At the base of the dam, mudstone with an uniaxial compressive strength of approximately 34 MPa is distributed. This rock has been thermally metamorphosed by the intrusion of granite, forming hard, massive hornfels. It contains a network of cracks, but these are tightly closed, without any particular orientation or continuity, and thus exhibit low permeability. Below an elevation of about 70 m, hard granite is present beneath the mudstone, having an uniaxial compressive strength of approximately 235 MPa.

Figure 3.

Geological cross section along the dam axis.

3. Seismic Performance Evaluation Method

In evaluating the seismic performance of dams in the event of a major earthquake, governmental guidelines [5] are generally applied. These guidelines indicate the seismic performance that dams should satisfy in the event of the largest earthquake that can occur at that location in the present and future (maximum expected earthquake). The seismic performance of arch-type concrete dams is investigated using 3D FEM models that include the dam body and the foundation rock because the structural behaviors of these types of concrete dams are characterized by their 3D behavior. The required seismic performance is that tensile stresses do not exceed the tensile strength of the dam body, and that compressive or shear failure does not occur in the dam body. Even if such failures occur, they should be limited to local areas so that the water storage capacity of the dam body is maintained.

As the concrete of a dam body can be treated as a linear material, the dam body is first evaluated using linear dynamic analysis, which treats it as a linear elastic body. If the results of the linear analysis indicate a risk of damage to the dam body, then nonlinear dynamic analysis is used to evaluate the damage process. The analysis in this study was conducted using the ISCEF Ver.2019.1.02 (Century Techno Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) software, a widely used 3D FEM program.

In this study, the results of the 3D linear dynamic analysis indicate that tensile and compressive stresses in the dam body remain generally below the corresponding material strengths, except for localized tensile stress concentrations near the dam base. Concerning shear failure, as the shear strength of the bedrock is lower than that of the dam body, the shear force H at the bottom of the dam body is lower than the resistance R calculated from the vertical force at the bottom and the strength of the bedrock; that is, the sliding safety factor Fs (=H/R) is 1.0 or more. In the seismic performance evaluation, the objective is to confirm that the water storage capacity is maintained, so the evaluation is conducted for dam body elements that are below the normal water level.

4. Dynamic Analysis Conditions

4.1. Analysis Model

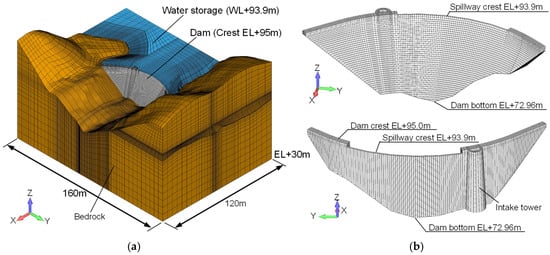

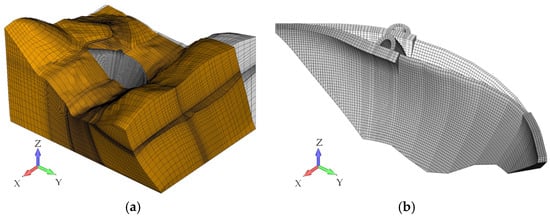

Figure 4 shows the three-dimensional FEM analysis model, which integrates the dam body, surrounding terrain, and reservoir. The dam body and foundation rock were modeled as solid elements using three-dimensional isoparametric elements with eight or six nodes, and joint elements were installed at the contact surface between the dam body and the foundation rock. The joint elements connect the nodes of the dam and foundation rock solid elements by springs in the shear and vertical directions. In general, joint elements allow sliding and separation at the interface according to shear and tensile failure criteria; however, in this study, shear and tensile failures were not considered. Therefore, the joint elements were introduced solely to evaluate the vertical and shear stresses acting at the dam–foundation interface.

Figure 4.

Three-dimensional FEM analysis model: (a) entire model; (b) downstream and upstream view of the dam model.

Although the added-mass approach based on Westergaard’s distribution is widely used in practical dam seismic analyses, the reservoir in this study was instead modeled using incompressible fluid elements in order to account for non-uniform responses along the dam axis and the influence of reservoir geometry. Interface elements were placed at the contact surfaces between the reservoir and both the dam body and the foundation rock, allowing hydrodynamic pressures induced by reservoir vibration to act on the structure. The water level was set equal to the dam crest elevation.

A subsidiary dam exists downstream of the dam; however, it was not included in the analysis model because it is an independent structure. The passageway and piers at the dam crest were also omitted, as they were considered to have negligible influence on the global seismic response of the dam.

The surface topography of the surrounding area was modeled using 5 m grid digital elevation model (DEM) data provided by the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan. The analysis domain was assumed to be uniformly covered by homogeneous foundation rock. The plan extent of the analysis model was set to at least twice the dam height in all directions around the dam, and the model bottom was located at a depth of approximately twice the dam height below the dam foundation.

Previous studies have shown that when the upstream truncation boundary of the reservoir is located at a distance of at least three times the water depth from the dam face, the influence of fluid pressure beyond this boundary on the hydrodynamic pressure acting on the dam is negligible [20,21]. Based on this criterion, the upstream extent of the fluid domain in the present model was set to 50 m from the upstream face of the dam, which exceeds three times the average reservoir depth of approximately 15 m.

The analysis was carried out in three sequential steps: initial stress setting, normal stress setting, and seismic response analysis. In the first step, the initial stress of the ground was set using the self-weight calculation method using only the ground section. In the second step, the dam body was installed on the foundation, and the self-weight of the dam together with the hydrostatic pressure was applied to establish the normal stress state of the dam–foundation system under static conditions. In the third step, the reservoir was installed and a dynamic analysis was performed by inputting seismic motion. Because the reservoir was modeled using fluid elements, hydrodynamic pressures induced by seismic excitation were automatically taken into account. In the present study, the static stress state obtained in Step 2 was used as the reference condition for the dynamic analysis in Step 3. As a result, the computed seismic response represents the combined effect of the initial static stresses and the incremental stresses induced by earthquake loading.

For the model boundary conditions, different boundary conditions were adopted for the static analyses (Steps 1 and 2) and the dynamic analysis (Step 3). In Steps 1 and 2, where static loads were applied, only the main analysis domain was considered; the bottom boundary was fixed, and the lateral boundaries were modeled as vertical rollers.

In Step 3, to reduce artificial reflection of seismic waves at the lateral boundaries, free-field ground models were added to both sides of the main analysis domain and connected using dashpots. In addition, the bottom boundary was modeled as a viscous boundary with dashpots to further suppress wave reflection during seismic excitation.

4.2. Physical Properties for the Analysis

Table 1 shows the physical properties of the dam body concrete and bedrock used for analysis. The compressive strength of the dam concrete was set based on the results of unconfined compression tests, and the tensile strength was assumed to be 1/10 of the compressive strength. For determining the elastic modulus of the dam body, PS logging was conducted, yielding observed velocities of Vs = 1100 m/s and Vp = 2581 m/s. However, as the dam concrete is a composite material of mortar and rough stone, it was difficult to determine the modulus directly. In general, for gravity dams, microtremor measurements are continuously conducted at the dam body, and the elastic modulus is identified such that the natural frequency obtained from observations coincides with that of the FEM model. In this case, however, as microtremor observation was not conducted for this dam, the setting was made to be consistent with the dam’s natural period (T = 0.22 × H/100 (s): when the dam height H = 21.5 m is substituted, T = 0.0473 (s)) using a simplified formula [22]. Other parameters, such as unit weight and damping ratio, were adopted as general values.

Table 1.

Physical properties for the analysis of the dam body concrete and bedrock.

The mudstone rock, which had a uniaxial compressive strength of ~34 MPa, was assumed to be uniformly spread throughout the model, and the elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio were set based on PS logging. Other physical properties were set according to the results of surveys of nearby dams and general values.

4.3. Input Seismic Motions

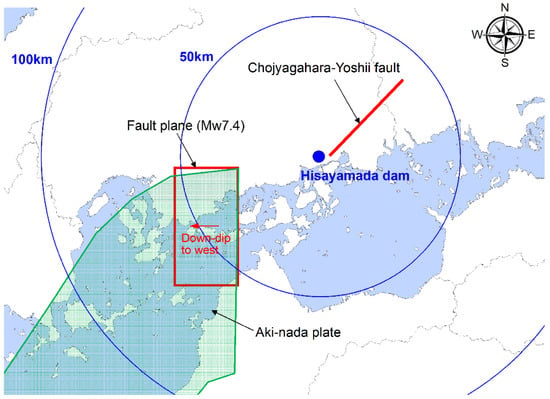

Two types of assumed seismic motion were set: an inland earthquake and a trench-type earthquake (Figure 5). The inland earthquake was that of the Chojagahara–Yoshii Fault near the Hisayamada Dam (Mw 6.9; fault length, 36 km; fault width, 18 km; dip angle, 90°; depth of the top of the fault, 2 km). For the trench-type earthquake, an intraplate earthquake that extended into the Aki-nada Sea near the dam was selected, and a fault surface with a length of 40 km and a width of 40 km (dip angle, 50°; depth at the top of the fault, 40 km) was adopted, corresponding to a moment magnitude of Mw 7.4. The location of the fault surface was set at the northeast corner of the plate shown in Figure 5 so that it would be at the shortest distance from the dam. Using the moment magnitude Mw of the target fault, the distance from the fault, and the depth of the fault, the horizontal and vertical acceleration response spectra were calculated using the distance attenuation formula specified in governmental guidelines for evaluating the seismic performance of dams against large-scale earthquakes [23].

Figure 5.

Location of the fault and Hisayamada Dam.

The seismic motion was created by adding the phase characteristics of typical strong motion records obtained from the dam foundation rock during past large-scale earthquakes. Therefore, the seismic motion created in the dam axis direction, upstream/downstream direction, and vertical direction was defined at the bottom of the dam body (EL + 72.96 m). For the phase characteristics of the Chojagahara–Yoshii Fault, the observation records of the Hitokura Dam for the 1995 Hyogo-ken Nanbu earthquake [5], an inland earthquake, were used. For the intraplate earthquake in the Aki-nada region, the observation records at the Ishite-gawa Dam from the 2001 Geiyo earthquake [24], which occurred within the same plate, were used. The phase characteristics of the strong motion records were in three directions: along the axis of the dam, upstream/downstream, and vertically. Time history acceleration waveforms in the direction of the axis of the dam and upstream/downstream were created by adding the phase characteristics of each direction to the horizontal acceleration response spectrum.

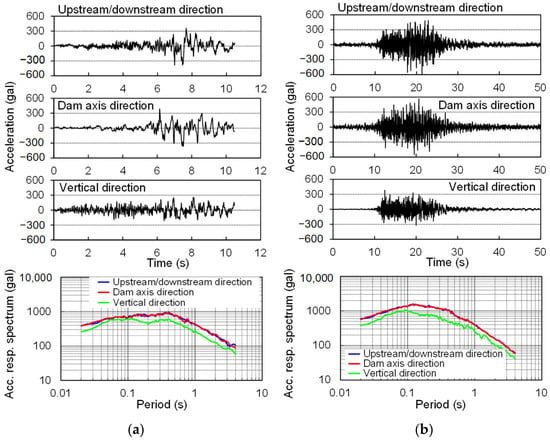

Figure 6 shows the acceleration time histories and acceleration response spectra of the input seismic motion caused by the Chojagahara–Yoshii Fault earthquake (hereafter referred to as the Chojagahara earthquake) and the intraplate earthquake in the Aki-nada region (hereafter referred to as the Aki-nada earthquake), both of which were defined at the bottom of the dam body. The maximum acceleration of the Chojagahara earthquake was 386 gal in the up and downstream directions and 260 gal in the vertical direction, with a duration of 10.5 s, whereas the maximum acceleration of the Aki-nada earthquake was 596 gal in the upstream and downstream directions and 381 gal in the vertical direction, with a duration of over 20 s. According to the acceleration response spectrum, the Chojagahara earthquake was slightly larger in the 0.4 to 0.6 s range, but the Aki-nada earthquake was larger in other frequency bands.

Figure 6.

Acceleration time history and acceleration response spectrum: (a) Chojagahara earthquake; (b) Aki-nada earthquake.

Deconvolution analysis was conducted on this seismic motion using a 3D FEM analysis model, and the seismic motion obtained at the base of the analysis model (EL + 30 m) was used to input the seismic motion in three directions simultaneously. Because the present study employs a linear dynamic FEM analysis based on the small-deformation assumption, the acceleration time histories obtained at the base were uniformly applied to the entire base of the analysis model. This approach does not consider spatial variability or propagation direction of seismic waves; however, it is commonly adopted in linear seismic response analyses to evaluate the overall dynamic behavior of dam–foundation–reservoir systems.

In addition, because the acceleration waveform had a bias in the positive and negative directions, the seismic motions in the upstream/downstream directions and the dam axis direction were inverted and analyzed. To examine the influence of directional bias in the input acceleration waveforms, the following three cases were analyzed:

- CASE-1: Upstream/downstream direction only inverted.

- CASE-2: Dam axis direction only inverted.

- CASE-3: Upstream/downstream and dam axis direction simultaneously inverted.

5. Analysis Results

5.1. Eigenvalue Analysis Results

The first dominant period of the model coupling of the dam body and foundation ground using eigenvalue analysis was 0.2380 s, and the second was 0.0924 s. These periods represent the global dynamic characteristics of the coupled dam–foundation system, which are mainly governed by the stiffness of the foundation and the overall system configuration. The first dominant period of the dam body alone was 0.0467 s, and the second was 0.0194 s. Although the natural periods of the dam body alone do not represent the global seismic response of the dam–foundation system, they are useful for interpreting the amplification characteristics of the dam crest response and the local dynamic behavior of the dam body. The first mode of the dam body and foundation and the first mode of the dam body alone are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

First-order mode diagrams: (a) the entire model; (b) the dam alone.

5.2. Analysis Results Under Normal Conditions

First, to verify the effect of the arch shape of the dam, the stress distribution of the dam body was examined by applying only hydrostatic pressure. Figure 8 shows the distribution of the horizontal and vertical stresses in the dam body when only hydrostatic pressure was applied. The vertical stress increased with the dam height. However, the horizontal stress in the dam body was tensile (at ~0.2 MPa) in the side parts of the dam. It was due to the central part moving forward because of the hydrostatic pressure, and no significant compressive stress due to the arch shape could be confirmed. This showed that the dam behaved similarly to a gravity dam.

Figure 8.

Distribution of stresses in the dam body under hydrostatic pressure only: (a) horizontal stress; (b) vertical stress.

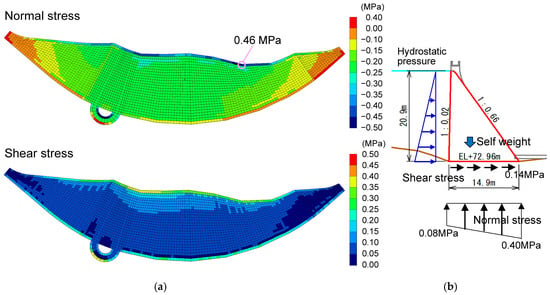

Figure 9 shows the distribution of normal and shear stresses in the upstream and downstream directions at the bottom of the dam under normal conditions, as well as the stress at the bottom of the dam, which was calculated simply using a 2D cross-section in the center of the dam. The normal stress on the bottom surface of the dam in Figure 9a was very small because of the tensile stress on both sides caused by the deformation of the dam, and a tensile stress exceeding 0.3 MPa occurred at the upstream end. However, the normal stress near the central part of the dam was 0.1–0.15 MPa at the upstream end and 0.55 MPa at the downstream edge; that of the central area was 0.22–0.24 MPa, which was about the same as the results of the 2D cross-section shown in Figure 9b. The shear stress at the bottom of the dam in Figure 9a was slightly greater at the upstream and downstream edges but was around 0.1 MPa at the central part of the dam, which was slightly less than the shear stress of 0.14 MPa at the bottom of the 2D cross-section. In addition, the dam height decreased at the side parts, but the shear stress did not decrease accordingly. From these results, the arch shape was inferred as causing the shear stress at the central part of the dam to be shared by both sides.

Figure 9.

Comparison of the stress at the bottom of the dam during normal conditions with the stress calculated using a simplified method for the 2D cross-section: (a) normal and shear stress at the dam bottom; (b) stress on the dam bottom for the 2D cross-section.

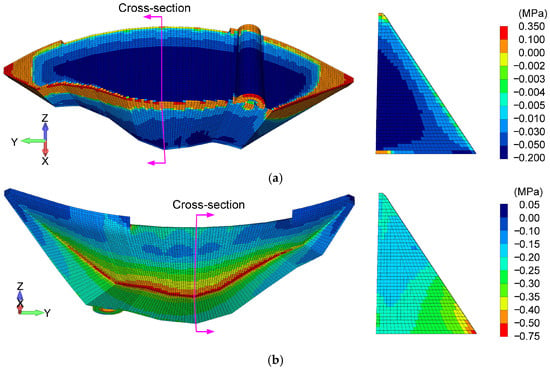

Figure 10 shows the distributions of the maximum tensile stress and maximum compressive stress in the dam body under normal conditions. The stress distributions are visualized based on the stress values at the centers of the finite elements, and the magnitudes of the maximum and minimum stresses depend on the adopted element size. In the present model, the element size is approximately 0.5 m on a side; therefore, localized stresses occurring at smaller scales cannot be evaluated. However, the adopted mesh resolution is considered adequate for assessing the global seismic response and overall stability of the dam within the framework of linear dynamic analysis. In the vicinity of the central part of the dam body, a maximum tensile stress of around 0.1 MPa occurred in a part of the upstream edge of the dam bottom, but no tensile stress occurred elsewhere on the dam body. Meanwhile, on both sides, a tensile stress of around 0.1 MPa occurred throughout the dam body, and a tensile stress of around 0.3 MPa occurred on the upstream edge of the dam bottom. However, the tensile strength of the dam body was 3.04 MPa or less, so this was not a concern. The maximum compressive stress was around 0.3 to 0.4 MPa at the downstream end of the bottom surface in the central part of the dam, and the compressive stress tended to be slightly higher on the downstream surface near the bottom surface in the side parts. As with the case where only hydrostatic pressure was applied, the arch shape reduced the stress near the central part of the dam and increased the stress in the side parts.

Figure 10.

Maximum stress distribution under normal conditions: (a) maximum tensile stress; (b) maximum compressive stress.

5.3. Earthquake Response Analysis Results

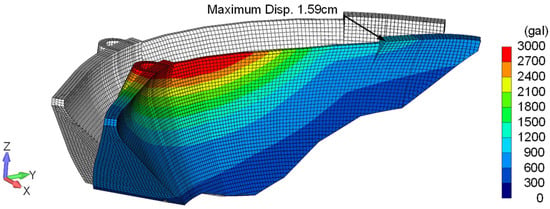

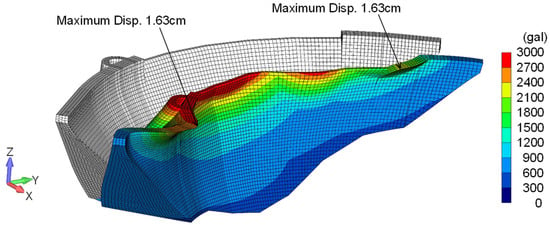

Figure 11 shows a superimposed image of the maximum acceleration distribution in the upstream and downstream directions and the maximum deformation diagram due to the Aki-nada earthquake. The maximum acceleration was 3334 gal at the top of the dam body near the center, and the maximum displacement was 1.6 cm. The maximum acceleration at the top of the dam body was amplified 5.6 times from 596 gal at the bottom of the dam body. Meanwhile, the maximum acceleration of the Chojagahara earthquake was 1060 gal at the top of the dam body near the center, the maximum displacement was 0.8 cm, and the amplification rate of the maximum acceleration was 2.7, which was smaller than that of the Aki-nada earthquake. The horizontal acceleration response spectrum value in Figure 6 at the first dominant period of the dam body (0.0467 s) was around 900 gal for the Aki-nada earthquake and around 600 gal for the Chojagahara earthquake. However, because of the effects of the dynamic water pressure, the dam shape and topography, and the simultaneous application of seismic motion from three directions, the response was considerably larger than the seismic response of the dam’s first mode.

Figure 11.

Maximum acceleration distribution and maximum deformation in the upstream and downstream directions due to the Aki-nada earthquake.

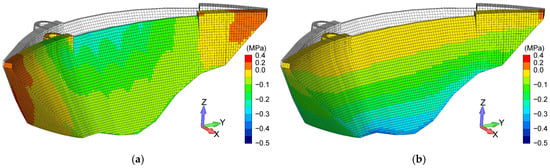

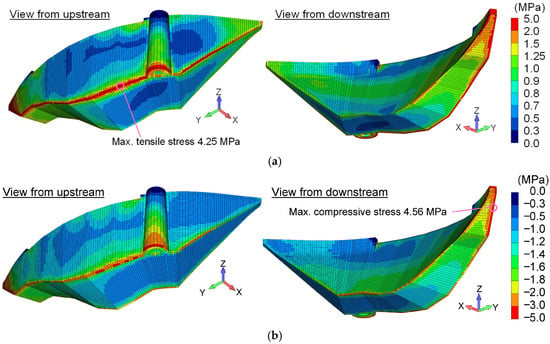

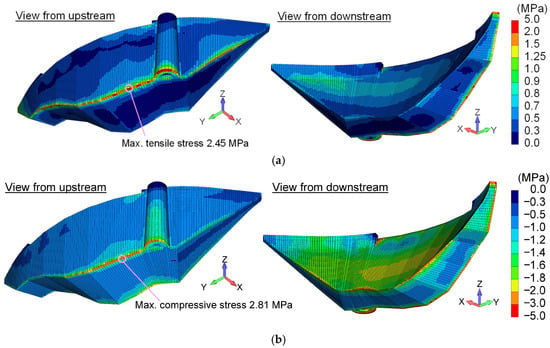

Figure 12 shows the distribution of the maximum tensile stress and maximum compressive stress generated in the dam body due to the Aki-nada earthquake. Compared with the stress distribution under normal loading conditions (Section 5.2), where tensile stresses of approximately 0.1–0.15 MPa occurred locally near the upstream edge of the dam base and at the abutments, the seismic response generates significantly larger stresses throughout the dam body. The maximum tensile stress shown in Figure 12a was large at the upstream and downstream heel of the dam bottom because of the earthquake force acting from the upstream and downstream sides, respectively, during the earthquake, and tensile stress was generated throughout the dam body. The maximum tensile stress was 4.26 MPa at the upstream end of the dam bottom, and the tensile stress locally exceeded the tensile strength of the dam concrete of 3.04 MPa. At the abutments, tensile stresses ranging approximately from 1.5 to 3.0 MPa were observed, and their magnitude tended to increase toward the outer sides rather than being uniformly distributed. This trend suggests that seismic loads acting on the central part of the dam are redistributed to the abutments through arch action. Meanwhile, the maximum tensile stress due to the Chojagahara earthquake was 4.12 MPa. Although the response of acceleration and displacement was smaller than that of the Aki-nada earthquake, the tensile stress was large. Overall, both tensile and compressive stresses induced by seismic loading are considerably larger than those under normal conditions, indicating that seismic-induced stresses dominate the stability evaluation of the dam.

Figure 12.

Distribution of maximum tensile stress and maximum compressive stress in the dam body due to the Aki-nada earthquake: (a) maximum tensile stress; (b) maximum compressive stress. The tensile stress is displayed as positive.

As with the maximum tensile stress, the maximum compressive stress shown in Figure 12b was greater at the upstream and downstream ends of the dam, with a maximum compressive stress of 3.0–3.5 MPa occurring at the upstream end of the dam. The maximum compressive stress around the central part of the dam was 4.0 MPa at the upstream end of the water intake tower, which protruded upstream. The maximum compressive stress of 4.56 MPa occurred at the left side of the dam, but as the dam height at this location was low, it was probably due to the arch shape. In comparison, in the Chojagahara earthquake, the maximum tensile stress also occurred at the same location, but the maximum value was smaller at 2.68 MPa.

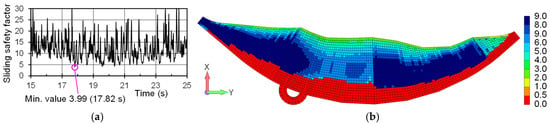

Figure 13 shows the time history of the sliding safety factor calculated from the stress of the joint elements installed on the entire dam base at the time of the main shock of the Aki-nada earthquake and the distribution of the sliding safety factor of each element of the dam bottom at the time of the minimum sliding safety factor. The minimum sliding safety factor was 3.99, and it occurred at 17.82 s. The sliding safety factor for each element of the dam bottom at 17.82 s showed a wide distribution of elements with a sliding safety factor of less than 1.0 on the upstream side. This was because tensile stress was generated on the upstream side of the dam base. However, the sliding safety factor was 6 or more in the vicinity of the dam center, and there were no elements where the sliding safety factor became 1.0 or less due to shear failure. In addition, there were no areas where the sliding safety factor was small in continuous upstream and downstream directions.

Figure 13.

Sliding safety factor of the bottom of the dam during the Aki-nada earthquake: (a) Time history of the sliding safety factor of the entire bottom of the dam; (b) Sliding safety factor of each element at the time of the minimum sliding safety factor.

6. Seismic Performance Evaluation

For the case of the reversed input seismic motion, an analysis was performed for the Aki-nada earthquake, which caused large tensile and compressive stresses. Table 2 shows a comparison of the maximum tensile and compressive stresses, and the sliding safety factor at the dam bottom, in the case where the Chojagahara earthquake waveforms were not reversed and the Aki-nada earthquake waveforms were reversed. In all cases, the maximum tensile stress exceeded the tensile strength of the dam body concrete (3.04 MPa). The exceedance of tensile strength was, however, confined to a very limited number of elements near the foundation edges and did not form a continuous zone in the upstream–downstream direction. In addition, the duration of tensile stress exceedance was extremely short, on the order of 1/100 s, and throughout the seismic motion the sliding safety factor in the axial direction near the central part of the dam consistently maintained a high value exceeding 6. Furthermore, the localized stress concentrations identified in the present linear analysis are likely to be redistributed to the surrounding regions through the formation of microcracks in the actual structure.

Table 2.

Maximum tensile and compressive stresses and sliding safety factor of the dam bottom.

The maximum compressive stress was 4.91 MPa in all cases, which is well below the compressive strength of the dam concrete (30.4 MPa), and therefore compressive failure is not expected to occur. The minimum sliding safety factor was 3.78, satisfying the required criterion of being greater than 1.0, indicating that shear failure at the dam base is not expected. Based on these results and their comprehensive interpretation, the occurrence of significant damage that could lead to a loss of water storage functionality is considered unlikely.

7. Discussion

7.1. Comparison of Seismic Performance for Different Elastic Moduli of the Dam Body

In the present analysis, the elastic modulus of the dam body was determined through numerical identification so that the natural frequency of the FEM model would match the empirical formula commonly used for gravity dams, because microtremor measurements were not carried out. This empirical formula was developed based on statistical analysis of measured vibration characteristics from existing concrete dams in Japan and is intended for standard gravity dams. However, the Hisayamada Dam is an arch–gravity concrete dam designed to utilize arch action, and its dam body consists of rough-stone masonry with mortar. Therefore, an additional analysis was conducted to examine the effect of assigning the elastic modulus calculated from the PS logging results (hereafter referred to as the dam body stiffness reduction case).

From the PS logging results (Vs = 1100 m/s, Vp = 2581 m/s), the elastic modulus of the dam body was calculated to be 7887 MPa, which is 0.4 times the value shown in Table 1. All other analysis conditions except for the elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio of the dam body were kept identical to those described in Section 4 (hereafter, the analysis conditions in Section 4 are referred to as the basic case). The analysis was conducted only for the Aki-nada earthquake. As a result, the first natural period of the dam body alone increased from 0.0467 s in the basic case to 0.0783 s, reflecting the softening of the dam body. This change in the natural period of the dam body alone is useful for interpreting the amplification characteristics of the crest response. In contrast, the first natural period of the coupled dam–foundation system was found to be 0.23810 s, which is almost identical to that of the basic case (0.23799 s). This result indicates that the global dynamic characteristics of the coupled dam–foundation system are governed primarily by the stiffness of the foundation and the overall system configuration, and are not significantly affected by changes in the elastic modulus of the dam concrete.

Figure 14 shows the distribution of maximum acceleration in the upstream–downstream direction together with the maximum deformation shape. Compared with the basic case shown in Figure 11, the maximum displacement at the side sections increased from 1.59 cm to 1.63 cm, and the maximum acceleration near the dam center increased from 3334 gal to 3587 gal. In the response spectrum of the Aki-nada earthquake shown in Figure 6b, the response acceleration corresponding to the first natural period of this reduced-modulus case is 1280 gal, whereas the response acceleration corresponding to the first natural period of the basic case is 1000 gal. This also confirms that the case with the reduced elastic modulus of the dam body results in larger seismic responses.

Figure 14.

Maximum acceleration distribution and maximum deformation in the upstream and downstream directions due to the Aki-nada earthquake for the dam body stiffness reduction case.

In addition, the distribution of maximum acceleration at the dam crest and the maximum deformation shows a single peak near the central part of the dam in the basic case, whereas reducing the elastic modulus of the dam body results in a distribution with multiple peaks, indicating higher-order mode effects. This behavior is considered to result from the three-dimensional topographic effects, as the ground on both abutments responds differently during the earthquake, as also observed in the first mode of the eigenvalue analysis shown in Figure 7a.

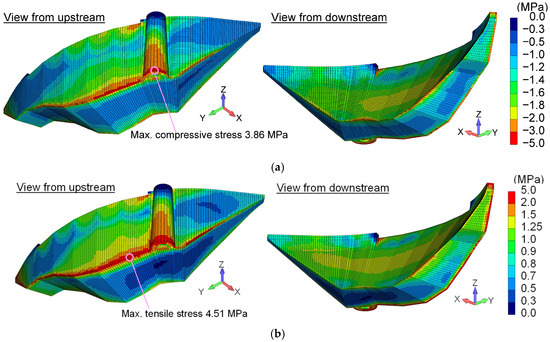

Figure 15 shows the distribution of maximum tensile and compressive stresses generated in the dam body. Compared with the basic case shown in Figure 12, both tensile and compressive stresses decreased. Although the seismic response became larger, the lower elastic modulus resulted in smaller stresses at the dam base. Consequently, the tensile failure region at the base decreased, and the minimum sliding safety factor increased significantly to 6.06, which is much larger than that of the basic case.

Figure 15.

Distribution of maximum tensile stress and maximum compressive stress in the dam body due to the Aki-nada earthquake for the dam body stiffness reduction case: (a) maximum tensile stress; (b) maximum compressive stress. The tensile stress is displayed as positive.

7.2. Comparison of Seismic Performance for Different Elastic Moduli of the Foundation Rock

In the present analysis, the foundation rock was modeled as a homogeneous material; however, hard granite is distributed approximately 10 m below the mudstone layer represented in the model. It is therefore possible that the seismic response of the dam is influenced by this underlying harder rock. For this reason, an additional analysis was performed to examine the effect of assuming granite as the foundation material (hereafter referred to as the foundation stiffness increase case). The elastic modulus of the granite was calculated from the PS logging results (Vs = 2175 m/s, Vp = 4273 m/s), yielding E = 33,351 MPa, which is approximately 1.8 times the elastic modulus of the mudstone shown in Table 1. All analysis conditions other than the elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio of the foundation rock were kept the same as the basic case (described in Section 4). The analysis was carried out only for the Aki-nada earthquake.

Figure 16 shows the distribution of the maximum tensile and compressive stresses generated in each dam element during the earthquake. Compared with the stress distribution of the basic case shown in Figure 12, both tensile and compressive stresses increased in the central portion of the dam, whereas they decreased in the side (abutment) sections. This indicates that increasing the elastic modulus of the foundation reduces the stress carried by the side sections due to arch action, meaning that the effectiveness of the arch action becomes smaller. It should be noted, however, that although an increase in foundation stiffness generally tends to amplify the seismic response of concrete dams, the discussion of arch action in this study is based on load redistribution associated with deformation of the dam–foundation system. Therefore, the influence of foundation stiffness on arch action cannot be discussed in a uniform manner, and both increases and decreases in local responses may occur depending on the deformation mode and interaction between the dam body and the abutments. As a result, the maximum acceleration at the dam center increased from 3334 gal in the basic case to 4786 gal, while the maximum displacement at the side sections decreased from 1.59 cm to 1.25 cm.

Figure 16.

Distribution of maximum tensile stress and maximum compressive stress in the dam body due to the Aki-nada earthquake for the foundation stiffness increase case: (a) maximum tensile stress; (b) maximum compressive stress. The tensile stress is displayed as positive.

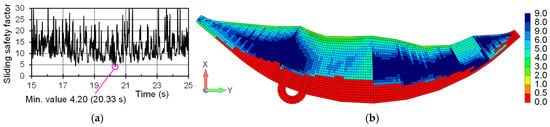

Figure 17 shows the time history of the sliding safety factor over the entire dam base during the Aki-nada earthquake for the foundation stiffness increase case, together with the spatial distribution of the sliding safety factor for each element at the time when the minimum sliding safety factor occurs. The minimum sliding safety factor was 4.20, which is nearly the same as that of the basic case. However, the distribution at 20.33 s indicates that the upstream region near the dam center, where the factor becomes less than 1.0, expanded slightly, and the sliding safety factor of elements from the central to downstream side decreased significantly. In contrast, in the side sections, the tensile zone became smaller and the sliding safety factor increased. Consequently, the overall sliding safety factor for the dam base remained similar to that of the basic case.

Figure 17.

Sliding safety factor of the bottom of the dam during the Aki-nada earthquake for the foundation stiffness increase case: (a) Time history of the sliding safety factor of the entire bottom of the dam; (b) Sliding safety factor of each element at the time of the minimum sliding safety factor.

8. Conclusions

For the 100-year-old masonry arch–gravity concrete dam, two earthquake motions were defined based on an inland-type fault near the dam and a trench-type fault along the subduction zone, and a three-dimensional dynamic FEM analysis was conducted to evaluate its seismic performance. In addition, analyses were performed by varying the elastic modulus of the foundation rock and the dam body to examine how differences in material stiffness influence the seismic response and overall seismic performance. The following findings were obtained:

- The maximum tensile stress during the earthquake caused localized tensile failure at the upstream heel of the dam base and in part of the side sections; however, because the magnitude of the tensile stress was small and the failure areas were limited, significant damage to the dam body is considered unlikely. Sufficient safety was also confirmed against compressive failure and sliding failure at the dam base. From these results, it was verified that no significant damage would occur in the dam body as a whole and that the water storage function would be maintained.

- The stress generated in the dam was generally similar to that of a gravity dam. However, due to the influence of the arch shape, stresses near the central part of the dam tended to decrease, while stresses at the side sections increased. It was also found that the arch shape of the Hisayamada Dam has the effect of reducing shear and tensile stresses occurring near the central part of the dam under hydrostatic pressure and seismic loading.

- When the elastic modulus of the dam body was reduced, the acceleration and displacement at the dam crest increased, as indicated by the response spectrum. However, the stresses generated at the dam base became smaller, and the overall sliding safety factor increased significantly compared with the basic case.

- When the elastic modulus of the foundation rock was increased, the effectiveness of arch action decreased, resulting in larger seismic responses near the central part of the dam and a reduction in the sliding safety factor at the central portion of the dam base. In contrast, stresses at the side sections decreased and their sliding safety factor increased. Consequently, the overall sliding safety factor of the dam base remained approximately the same as that of the basic case.

It should be noted that this study did not consider failure at the contact surface between the dam body and the foundation rock, nor cracking within the dam concrete. For a more rigorous evaluation, it is necessary to perform nonlinear analysis using joint elements that allow sliding and separation at the dam–foundation interface, as well as solid elements capable of representing crack formation in the dam body. In addition, the present analysis does not explicitly account for crack propagation and the possible development of uplift pressure associated with water penetration into cracks, nor the resulting influence on structural stability. Furthermore, validation using field monitoring data, parametric investigation of key structural and material properties, and evaluation of long-term deterioration effects were beyond the scope of this study and remain important subjects for future research. Incorporating these coupled mechanisms into a three-dimensional nonlinear analysis framework is an important subject for future research, particularly for a more detailed assessment of post-earthquake integrity and long-term water storage performance of arch–gravity dams.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.I., H.K. and M.K.; methodology, N.I., R.K. and H.K.; software, R.K.; validation, N.I. and H.K.; formal analysis, R.K.; investigation, R.K., H.K. and M.K.; data curation, R.K., H.K. and M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, N.I.; writing—review and editing, N.I. and H.K.; visualization, R.K.; supervision, H.K.; project administration, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Naoki Iwata and Ryouji Kiyota were employed by the Chuden Engineering Consultants Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 2D | Two-dimensional |

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| FEM | Finite Element Method |

References

- Chopra, A.K.; Chakrabarti, P. The earthquake experience at koyna dam and stresses in concrete gravity dams. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1972, 1, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clough, R.W.; Chopra, A.K. Earthquake Response Analysis of Arch Dams; Report No. EERC 65-10; Earthquake Engineering Research Center, University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Fenves, G.L.; Vargas-Loli, L.M. Nonlinear dynamic analysis of fluid–structure systems. J. Eng. Mech. 1988, 114, 219–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, G.; Yu, X. Seismic cracking analysis of concrete gravity dams with initial cracks using the extended finite element method. Eng. Struct. 2013, 56, 528–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT). Technical Guideline for Seismic Performance Evaluation of Dams Against Large Earthquakes; National Institute for Land and Infrastructure Management (NILIM): Tsukuba, Japan, 2005. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Fok, K.; Chopra, A.K. Earthquake analysis of arch dams including dam–water interaction, reservoir boundary absorption, and foundation flexibility. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1986, 14, 155–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.F.; Chopra, A.K. Dynamic analysis of arch dams including hydrodynamic effects. J. Eng. Mech. 1983, 109, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Tu, J. Nonlinear seismic response analysis of arch dam–foundation systems—Part II: Opening and closing contact joints. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2007, 5, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-T.; Lv, D.; Jin, F.; Zhang, C.-H. Earthquake damage analysis of arch dams considering dam–water–foundation interaction. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2013, 49, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wang, Y.; Lu, W.; Zhou, W.; Chen, M.; Yan, P. XFEM based seismic potential failure mode analysis of concrete gravity dam-water-foundation systems through incremental dynamic analysis. Eng. Struct. 2015, 98, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOLD Committee on Computational Aspects of Dam Design. Evaluation of ultimate strength of gravity dams with curved shape against sliding. In Proceedings of the 7th Benchmark Workshop on Numerical Analysis of Dams, Bucharest, Romania, 24–26 September 2003; ICOLD: Paris, France, 2003; pp. 20–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Yan, S.; Li, D.; Du, W. Seismic performance assessment of high arch dams considering pulse-like and directionality effects of near-fault ground motions. Eng. Struct. 2024, 312, 119010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jin, F.; Zhang, C.-H. Nonlinear seismic response analysis of high arch dams to spatially-varying ground motions. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2019, 17, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffi, G.; Manciola, P.; De Lorenzis, L.; Cavalagli, N.; Comodini, F.; Gambi, S.; Gusella, V.; Mezzi, M.; Niemeier, W.; Tamagnini, C. Calibration of finite element models of concrete arch-gravity dams using dynamical measures: The case of Ridracoli. Procedia Eng. 2017, 199, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasa, A.Y.; Budak, A.; Düzgün, O.A. Seismic performance evaluation of concrete gravity dams using an Efficient Finite Element Model. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 2024, 12, 2595–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, B.K.; Segura, R.L.; Bagchi, A. Modeling variability in seismic analysis of concrete gravity dams: A parametric analysis of Koyna and Pine Flat Dams. Infrastructures 2024, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, A.; Oliveira, S.; Mendes, P.; Proença, J.; Ramos, R.; Carvalho, E. Seismic safety assessment of arch dams using an ETA-Based Method with control of tensile and compressive damage. Water 2022, 14, 3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, T.S.; Al-Husseini, T.R.; Mousa, M.A.; Al-Jelawy, H.M. Comparative analysis of stochastic variables for seismic vulnerability of concrete gravity dams. Multiscale Multidiscip. Model. Exp. Des. 2025, 8, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zine, A.; Guettala, S.; Khelaifia, A.; Kadid, A. Advanced non-linear analysis of concrete gravity dams under multi-directional ground motions. J. Build. Pathol. Rehabil. 2025, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clough, R.W.; Chang, K.T.; Chen, H.-Q.; Stephen, R.M.; Wang, G.-L.; Ghanaat, Y. Dynamic Response Behavior of Xiang Hong Dian Dam; Report No. UCB/EERC-84/02; Earthquake Engineering Research Center, University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Clough, R.W.; Chang, K.T.; Chen, H.-Q.; Stephen, R.M.; Ghanaat, Y.; Qi, J.-H. Dynamic Response Behavior of Quan Shui Dam; Report No. UCB/EERC-84/20; Earthquake Engineering Research Center, University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Japan Dam Engineering Center. Construction of Multipurpose Dams; Vol. 4: Design I; Japan Dam Engineering Center: Tokyo, Japan, 2005; p. 95. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, T.; Ito, T. Attenuation relationship of earthquake motion at dam foundation considering the 2011 Tohoku earthquake. J. Jpn. Assoc. Earthq. Eng. 2016, 16, 80–92, (In Japanese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT). Acceleration Records at Dams Under the Jurisdiction of MLIT; Technical Note of National Institute for Land and Infrastructure Management No. 734; NILIM: Tsukuba, Japan, 2013; (In Japanese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.