4.1. Calibration Strip Testing Results

Results obtained from the calibration strips were analyzed to assess variability, as the pavement on the calibration strips remains unworn and uncontaminated. Calibration strip friction testing results were collected at two airports, referred to here as Airport A and Airport B. Airport A provided results from 2007 to 2011, and Airport B from 2013 to 2023. All tests were performed by third-party contractors, different for each airport. Calibration strip results provide valuable information on repeatability and variability, since the strip is typically unaffected by aircraft traffic and wear.

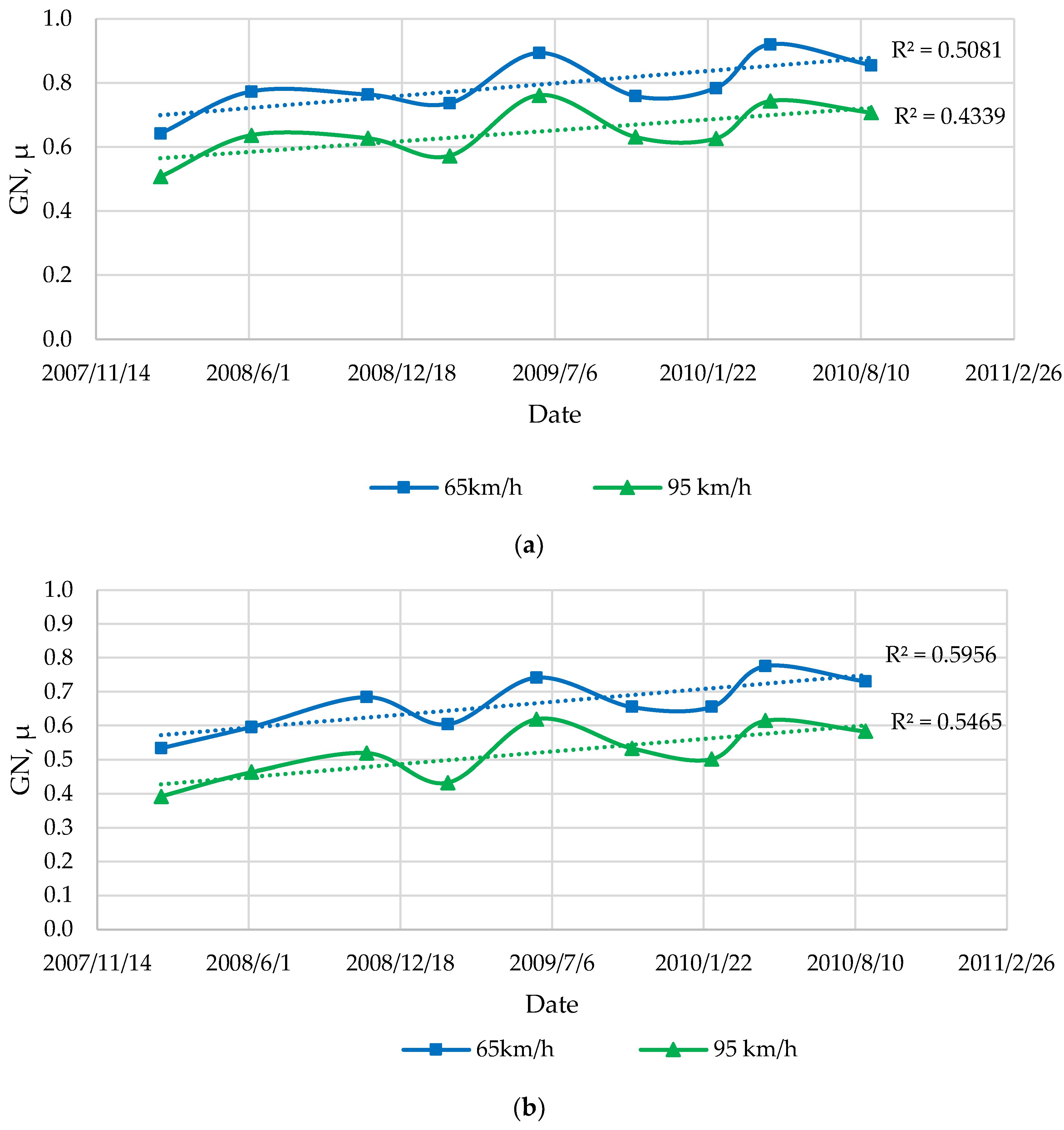

Figure 2 presents the friction testing results for the calibration strip at Airport A. There is a noticeable trend showing an increase in friction on a calibration strip that can be attributed to testing equipment tire wear, which was previously shown in another study [

10] by Equation (1). The coefficient of determination, however, is relatively low (R

2 = 0.43–0.59) due to high variation in results.

where

F is the friction value,

GN is the GripTester number,

SD is the standard tire diameter (260 mm),

CD is the chain cog effective diameter (130 mm), and

MD is the measured tire diameter.

On the other hand, tire wear of the testing equipment can significantly influence friction testing results through changes in adhesion, which may become particularly pronounced in materials with a large surface area [

58,

59]. Previous studies have also shown that an increase in surface area due to wear can substantially affect friction testing outcomes [

23]. Standards, however, do not mention testing tire roughness change during the test and its effect on the results [

47]. It is also important to note that measured friction can change due to binder film wear [

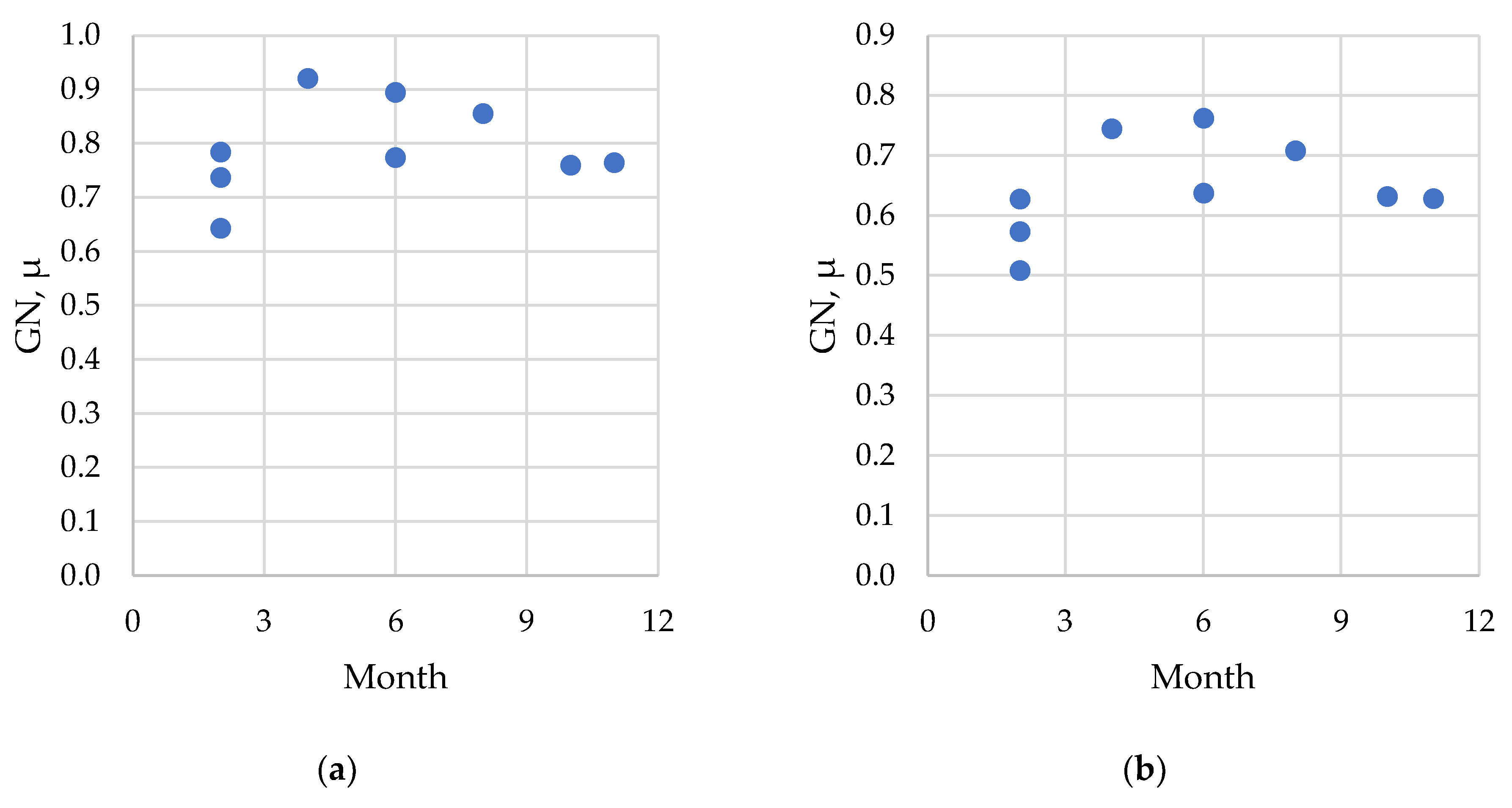

60], but this effect might affect friction only at the beginning of the lifecycle, and the whole trend cannot be explained by this effect. At the same time, there is a significant difference between winter and summer testing results, as shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. The difference in average friction can reach up to 25% between winter (June) and summer (February) results within the same year, which is consistent with findings reported in other studies [

17,

18].

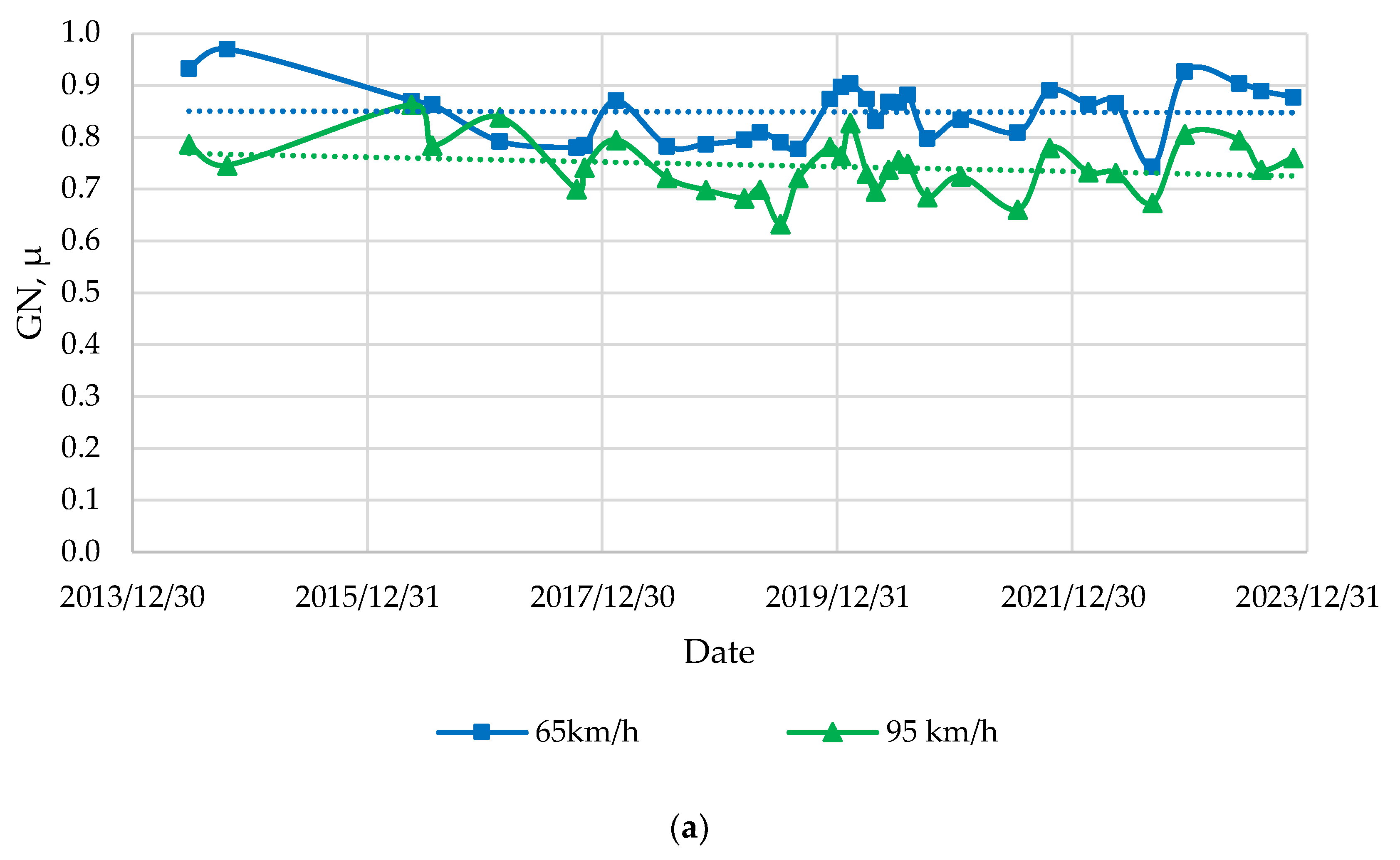

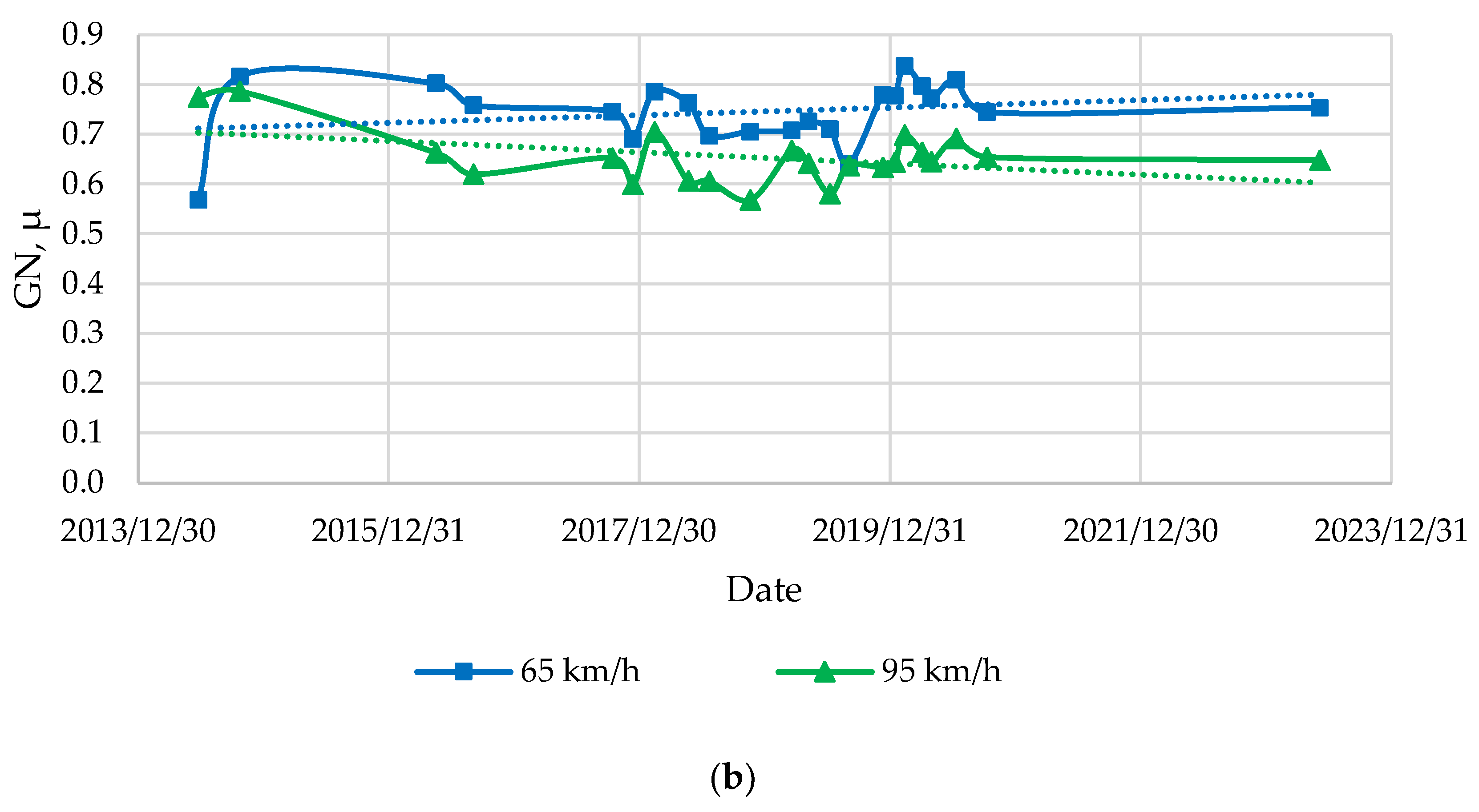

Measurement statistics from Airport B were collected between 2013 and 2023, providing a larger dataset compared to Airport A. Similarly to Airport A, the calibration strip testing results at Airport B show a maximum variation of about 25% across different years (

Figure 5). However, the average friction remains relatively stable, with no discernible long-term trend.

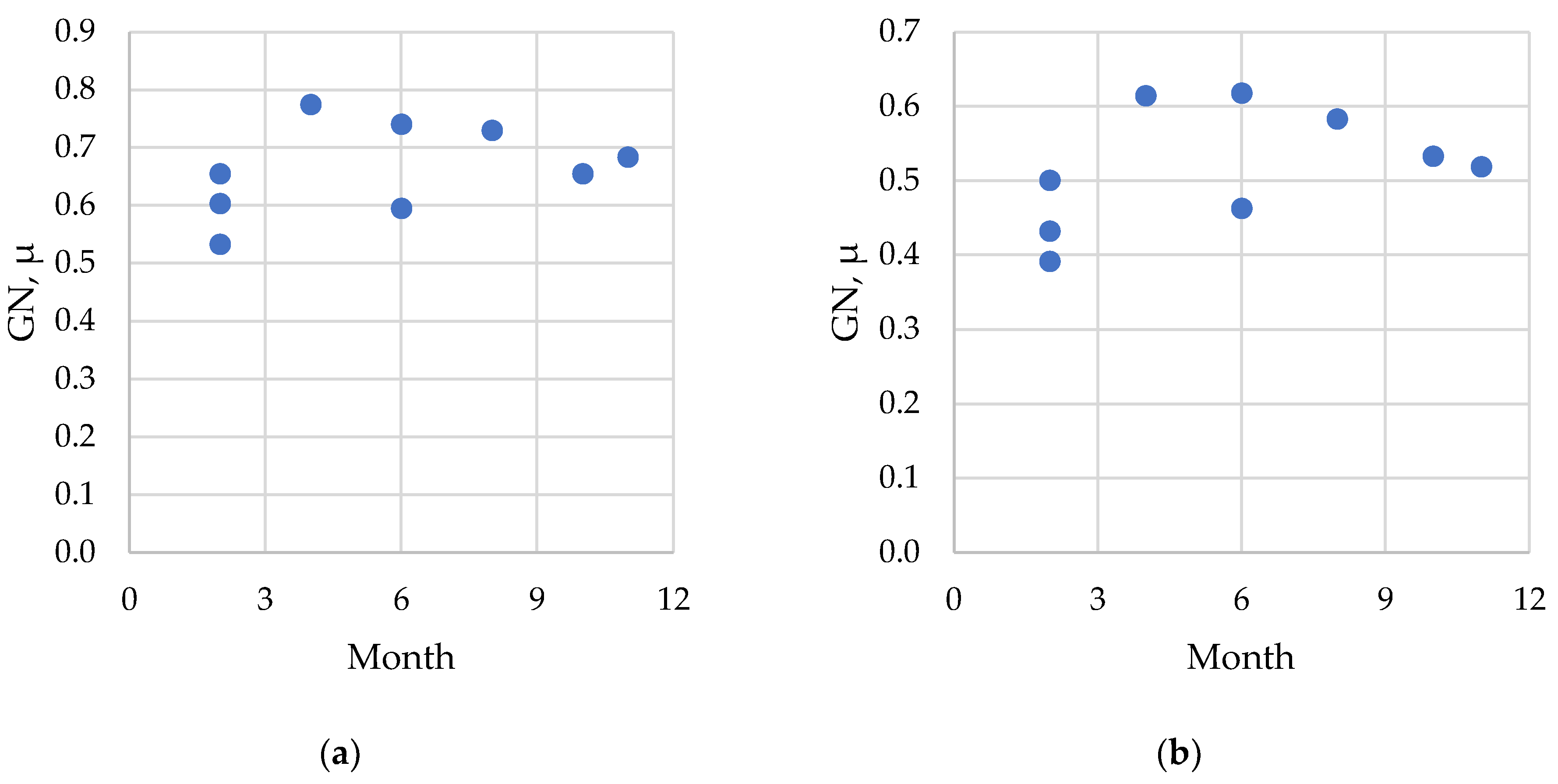

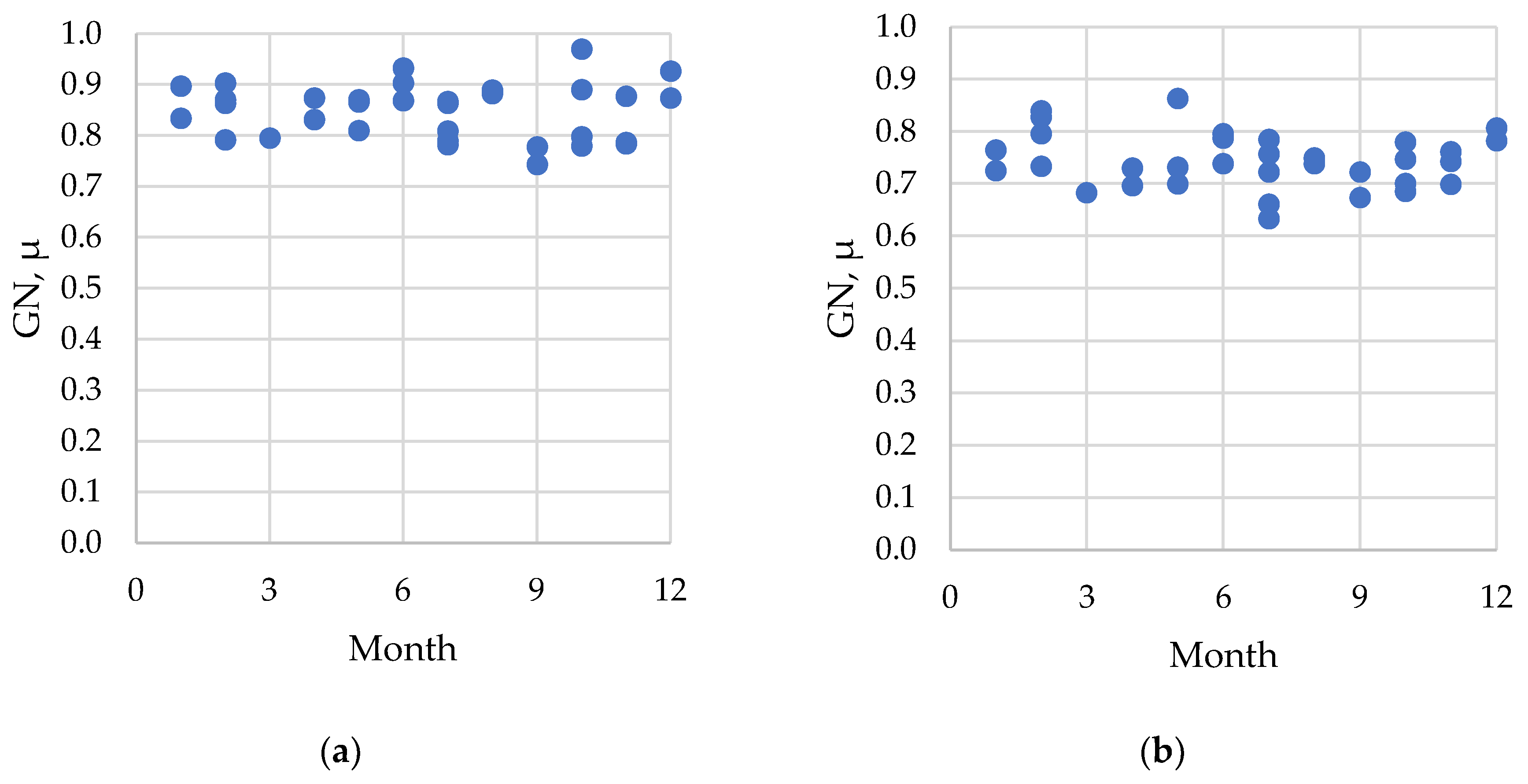

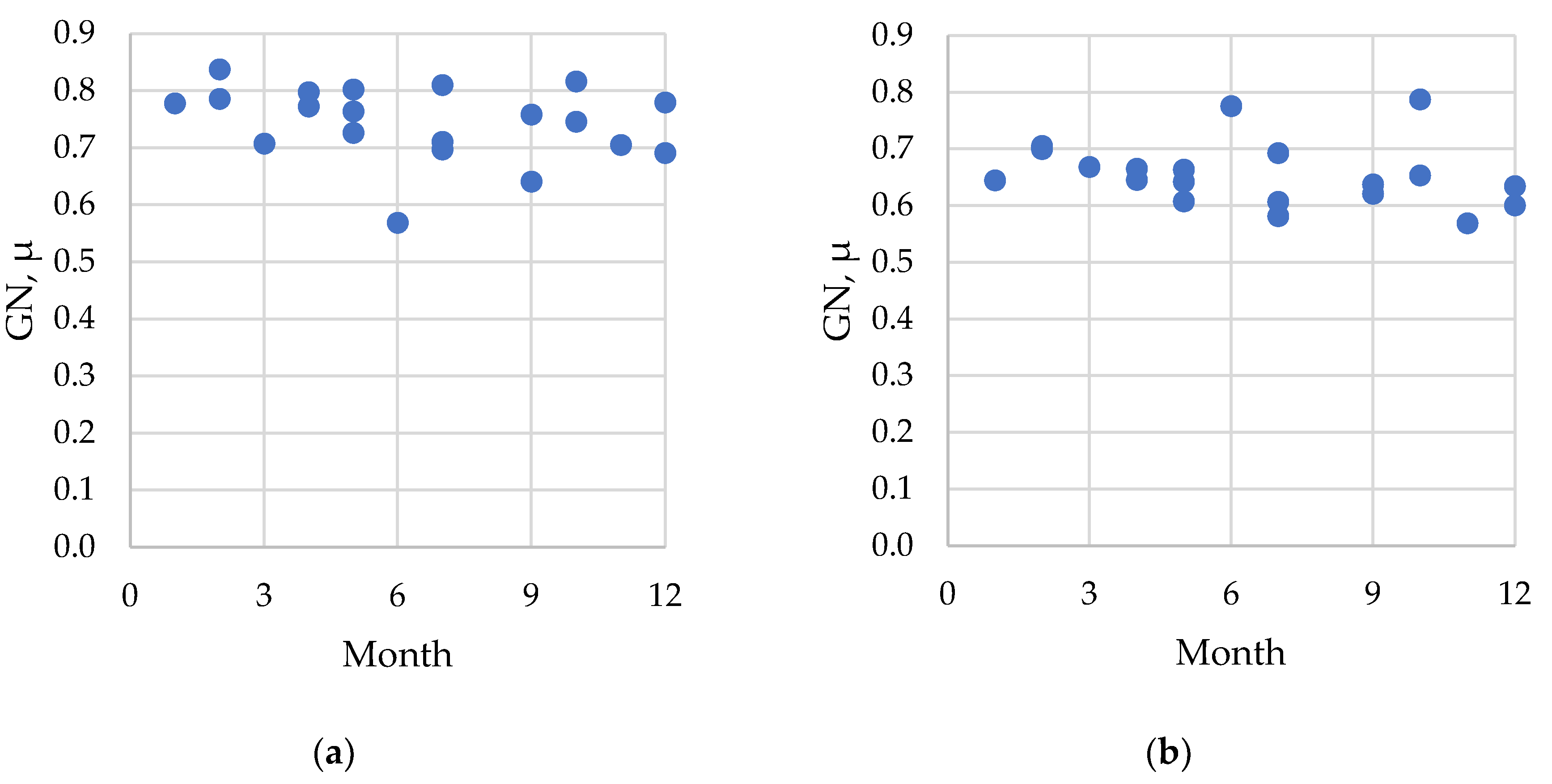

In contrast to Airport A, the variation at Airport B is not associated with seasonal changes (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). Instead, it is primarily attributable to random deviations, which outweigh seasonal effects. These deviations may result from measurement error, calibration error, and tire wear; however, unlike at Airport A, the tire wear effect is not gradual. This difference likely reflects the use of a frequently operated GripTester and the longer observation period at Airport B.

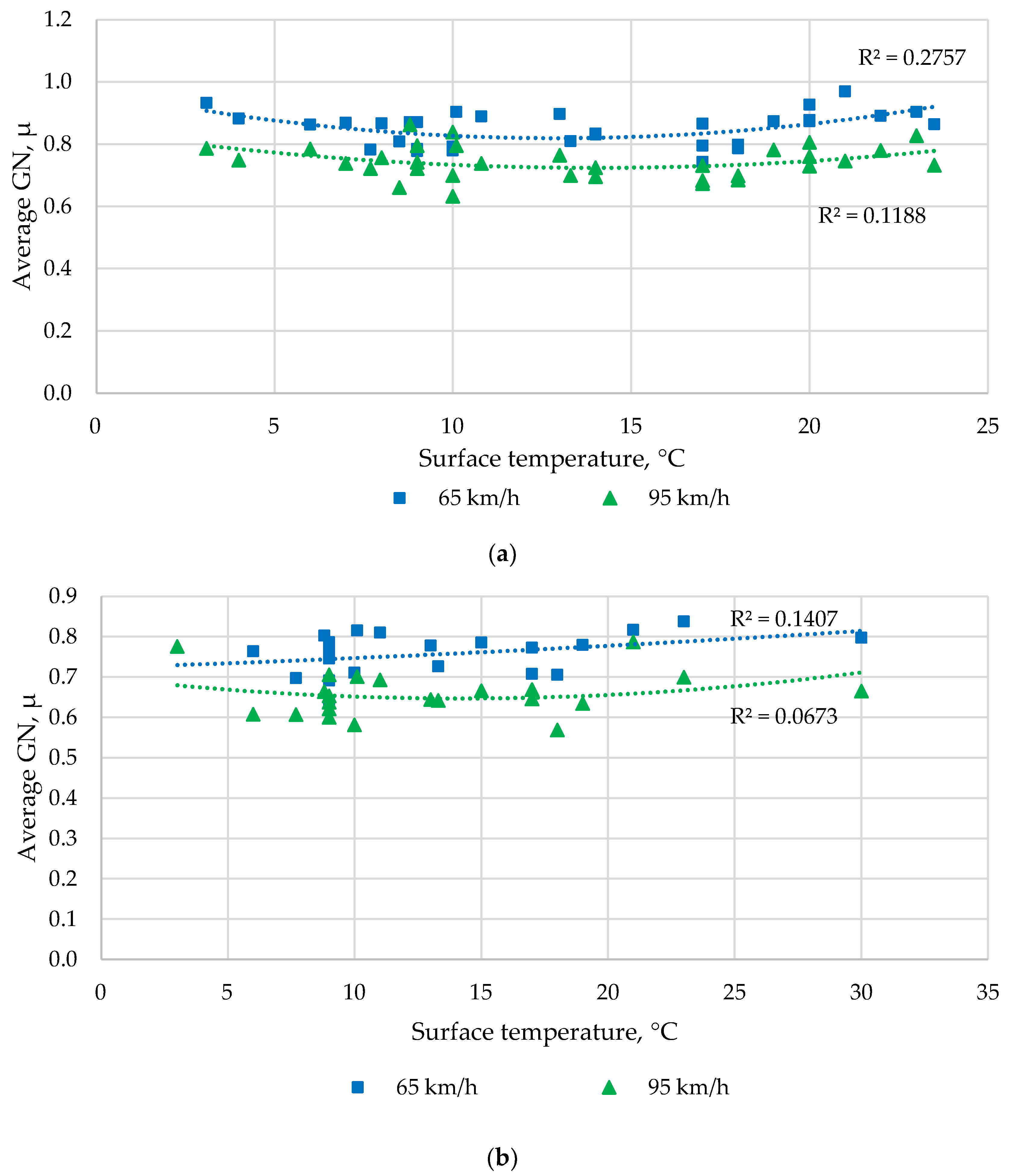

During the calibration strip measurements at Airport B, surface temperature was also recorded. However, no significant correlation was found between temperature and friction test results (

Figure 8). On both the main and secondary runways, minimum friction occurred at around 15 °C; however, there is no sufficient correlation between surface temperature and friction testing results. The highest coefficient of determination was obtained for the 65 km/h results on the main runway (R

2 = 0.28), which is insufficient to draw a conclusion about the influence of surface temperature on friction.

To approximate the influence of errors associated with seasonal changes and random variability, the standard variance law can be applied [

61]. For the Airport B dataset, the variance of average friction measurements can be compared with the variance of friction results for each third of the calibration strip, using values adjusted to compensate for seasonal effects and the constant error from equipment calibration. In this framework, the variance within each third (with adjusted values) represents random error, whereas the variance of the overall average friction results for the calibration strip reflects both random variability and the additional contributions of seasonal effects and constant calibration error. This method was employed to minimize the influence of seasonal variation when comparing results from the runway thirds. At the same time, it allows for direct comparison of the same thirds across different years. This does not provide the exact magnitude of the random error; however, it offers a practical estimate without requiring a detailed analysis of friction results, which is complicated by the fact that chainages for friction testing might differ slightly from year to year. By comparing these variances, the relative influence of seasonal changes and calibration error on the results can be approximated (

Table 3 and

Table 4).

The results indicate that approximately 26–83% of the total variance is attributable to random error rather than seasonal changes, with higher random variance observed for the secondary runway. This difference may reflect the higher measurement quality achieved on the main runway. The contribution of random error to the overall variance is greater at 95 km/h, owing to the lower total variance at this speed. Conversely, at 65 km/h, seasonal changes and constant calibration error have a stronger influence on measurement results, likely due to the adhesive component of friction at lower speeds, which is more sensitive to variations in weather conditions and tire wear.

For Airport B, both the random error and its contribution are significantly lower, likely due to generally lower friction values. At the same time, the overall error is higher, probably reflecting the effect of tire wear. Seasonal effects and calibration error increase the variance at 65 km/h. This difference is grater compared to the variance from the airport B, likely because tire wear disproportionately affects adhesive friction, which is more pronounced at lower speeds.

Overall, friction testing results differ between the two airports, with seasonal effects having a greater influence at Airport A and random error being more pronounced at Airport B. It is also important to note the impact of tire wear on the results from Airport A. In general, random deviations can reach 0.05 µ for both 65 and 95 km/h. When including both random deviations and seasonal effects, the total deviation can reach 0.09 if tire wear is not controlled or accounted for. These findings are consistent with results reported in previous studies [

10,

15].

4.2. Runway Friction Testing Results

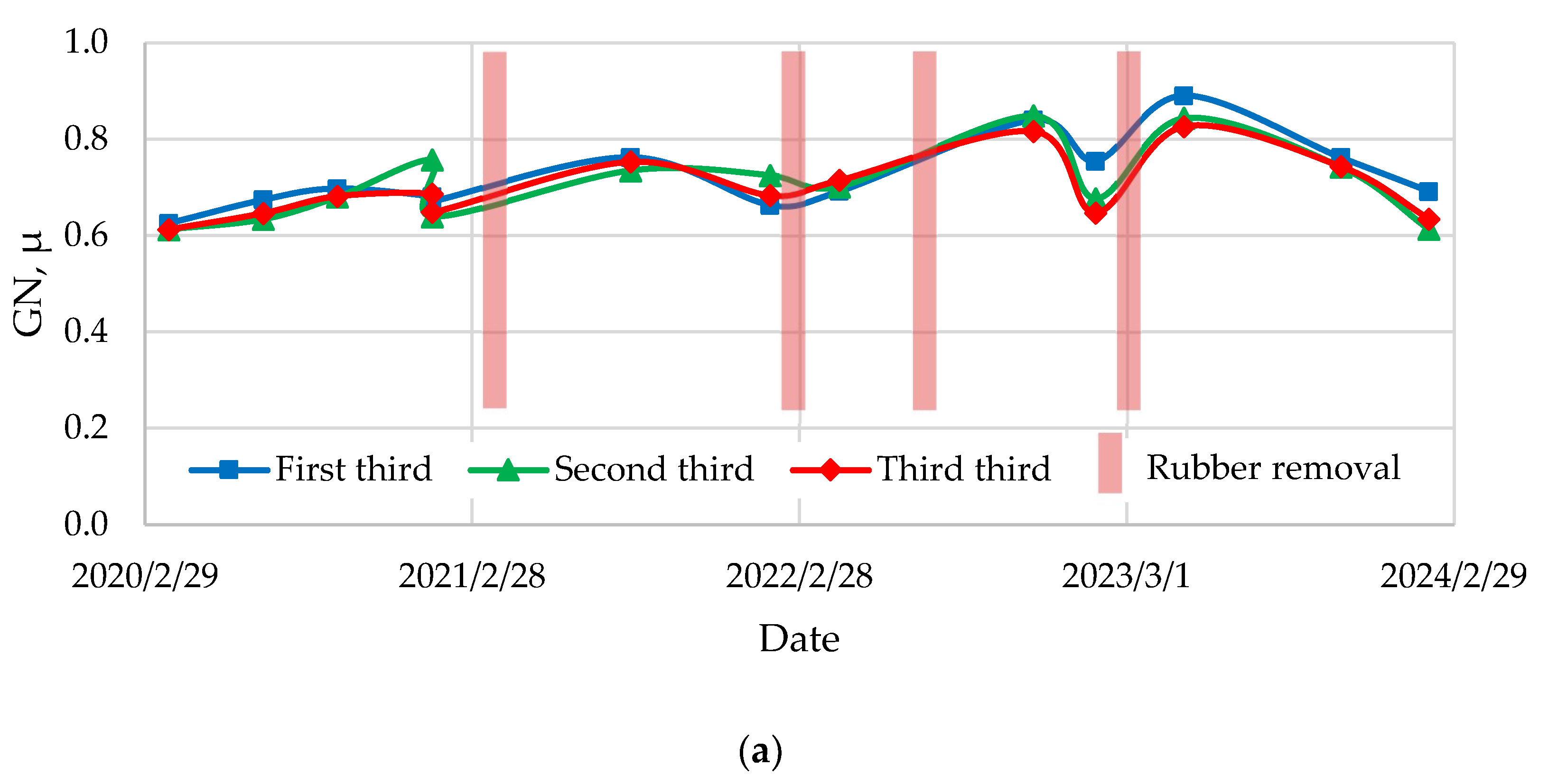

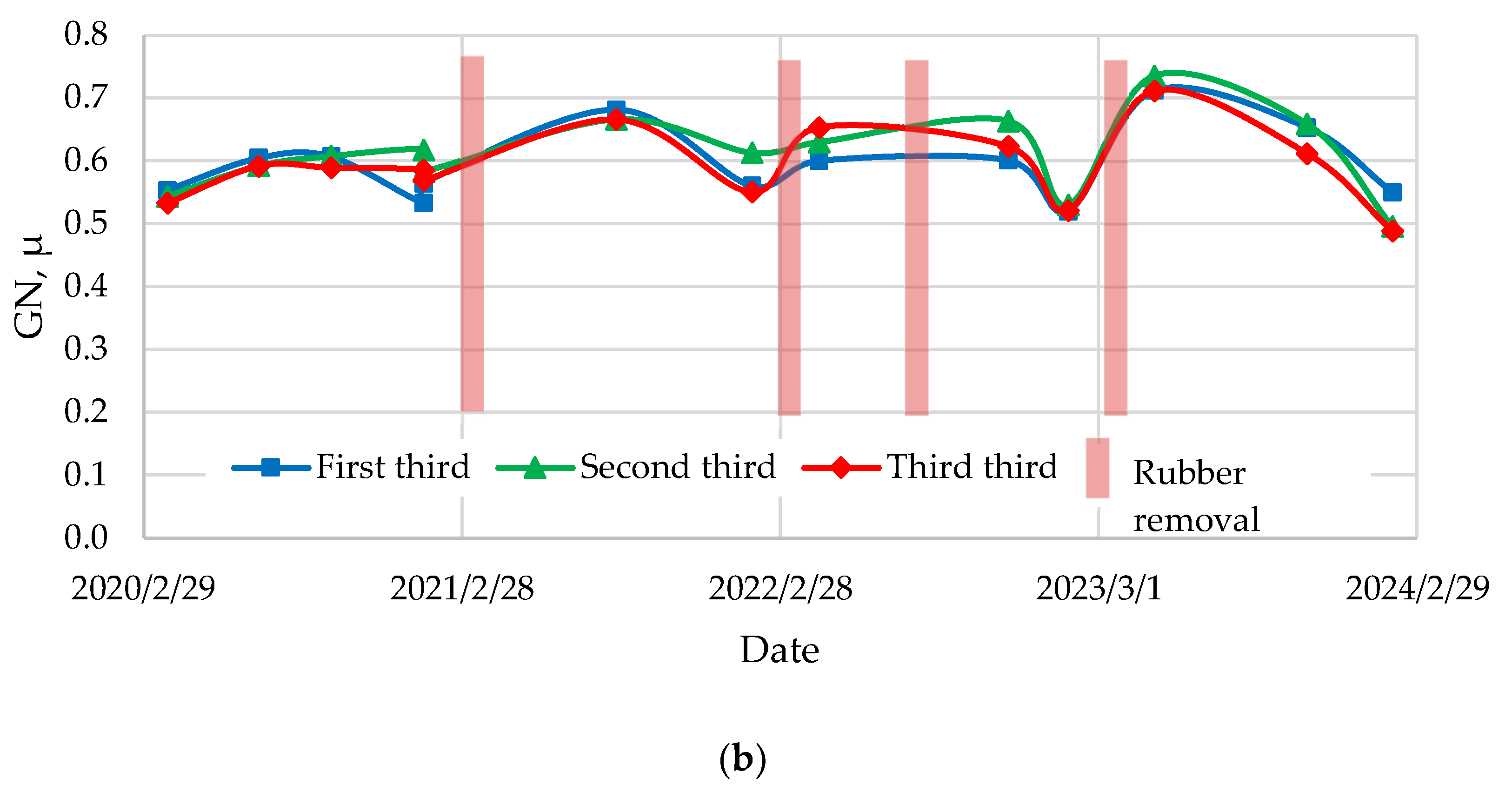

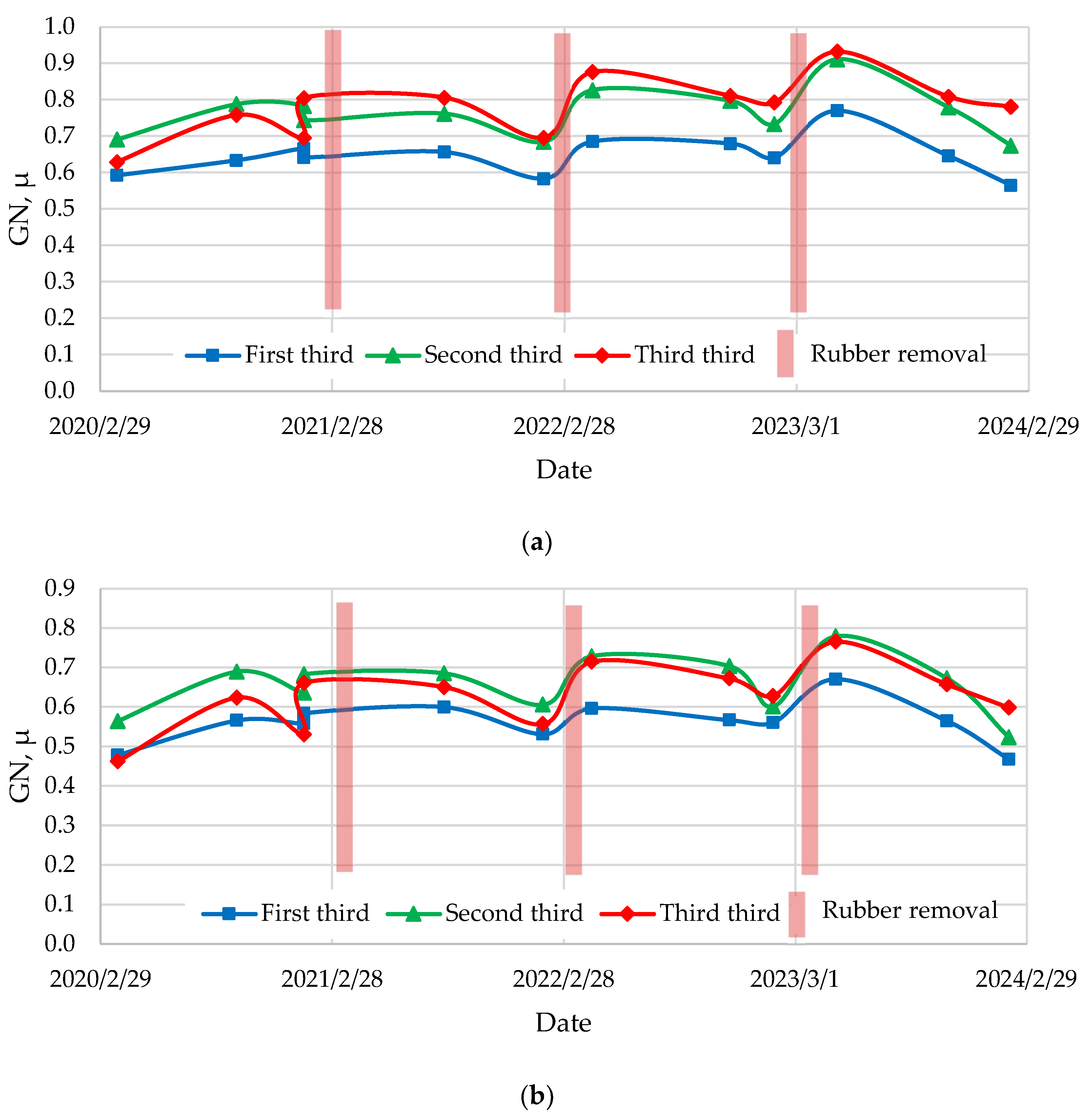

The CFME friction results from Airport C are shown in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, for the main and secondary runways, respectively. The results were measured 3 m from the centerline, starting from the time of construction, for the main and secondary runways of Airport C. Friction testing results for the runways of Airports A and D were not included in this analysis, as only limited measurement points were available between maintenance activities, and the friction dynamics were not clearly observable. The friction dynamics on the secondary runway were more evident, as rubber removal was performed less frequently and in a more consistent manner.

Traffic on the main runway of Airport C is approximately 2.5 times higher than on the secondary runway. Maintenance activities are also indicated in the graph. For both the main and secondary runways, there is a noticeable improvement in friction immediately after construction, which can be attributed to a combination of binder scouring and testing tire wear. It can also be observed that the second third of the runway shows greater friction improvement after construction, likely because touchdown zones experience immediate rubber build-up following binder scouring.

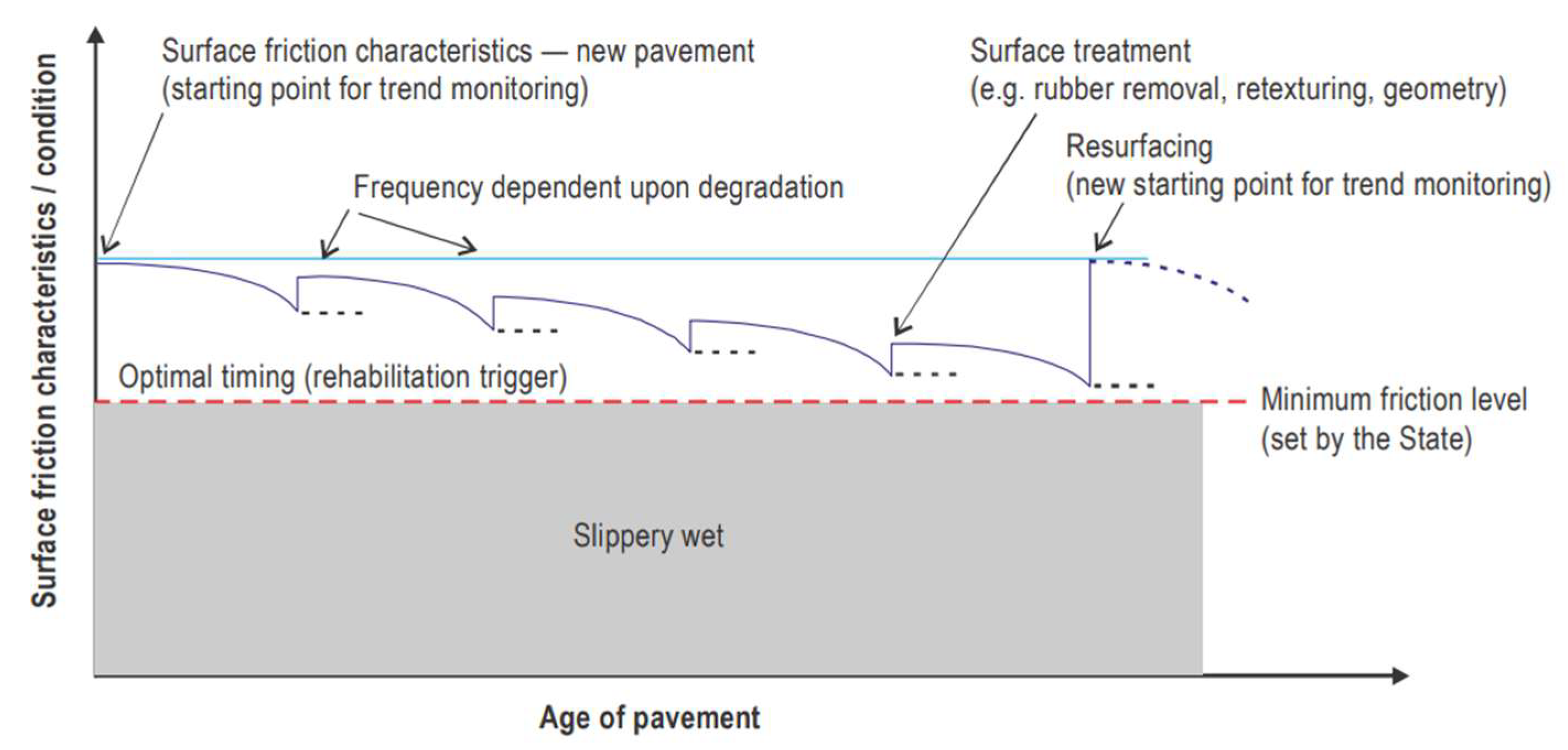

Friction on each runway shows a significant improvement following maintenance works. Notably, friction after rubber removal can even exceed the levels observed immediately after construction. The underlying cause of this effect remains unclear—it may be related to binder scouring or to improvements in microtexture resulting from rubber removal. However, this observation contradicts both previous findings and the recommended friction monitoring concept (

Figure 1). Nevertheless, it highlights the importance and effectiveness of rubber removal.

Airport C uses an ultra-high-pressure water rubber removal system. It operates by blasting water through a rotary device at pressures of up to 40,000 psi [

62]. This method effectively removes rubber from the pavement and improves surface texture compared to other techniques. One of its main advantages is that it preserves the drainage characteristics of the pavement. Although some reports suggest a reduction in microtexture due to water blasting, other studies have found no evidence of this effect, concluding that it depends on the aggregate type and may be related to the normal polishing of aged pavement [

63].

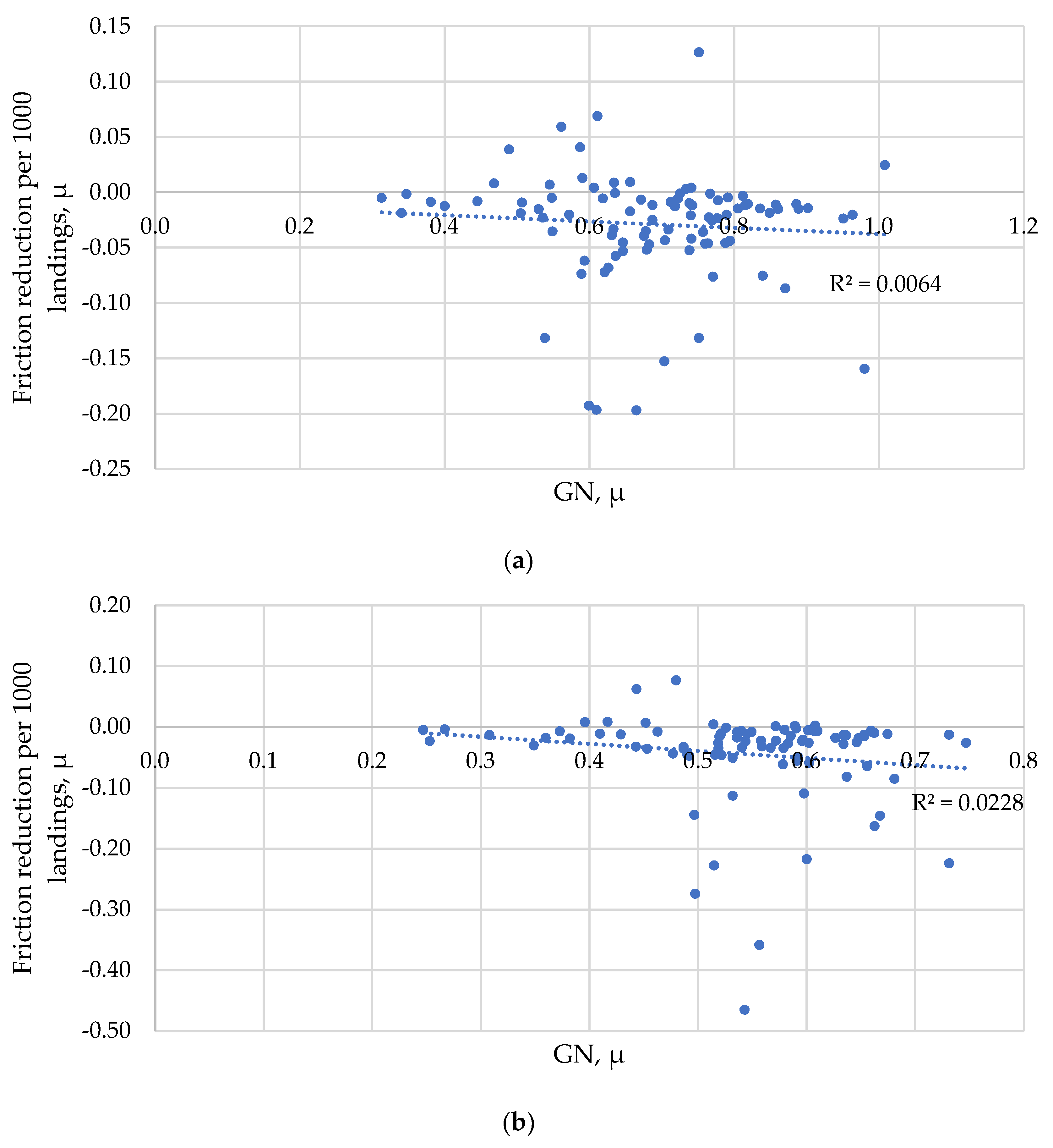

It is evident from the graphs (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10) that the friction reduction rate for runway thirds is higher when friction is lower. To evaluate the friction reduction rate for 100 m averages at the touchdown points, the friction reduction per 1000 landings on each runway end was compared to the friction values from Airports A, C, and D (

Figure 11). Due to the high variance in the friction testing results, as noted previously, the correlation between friction levels and friction reduction is extremely low. Nevertheless, a clear pattern emerges: there is no abrupt friction reduction when friction is low, particularly for the 95 km/h results.

A t-test comparing the reduction rate between the 0–0.45 µ and 0.45–1 µ friction level ranges yielded a statistically significant difference (p < 0.001) for the 95 km/h results. For the 65 km/h results, a similar test between the 0–0.6 µ and 0.6–1 µ ranges showed a less significant difference (p = 0.037), reflecting the higher variability of the 65 km/h measurements. These findings indicate that the friction reduction rate for 100 m averages at touchdown zones decreases as friction decreases, while the higher reduction rate observed for runway thirds can be explained by the progressive extension of rubber-contaminated zones. This conclusion underscores the importance of timely rubber removal to optimize runway maintenance costs.

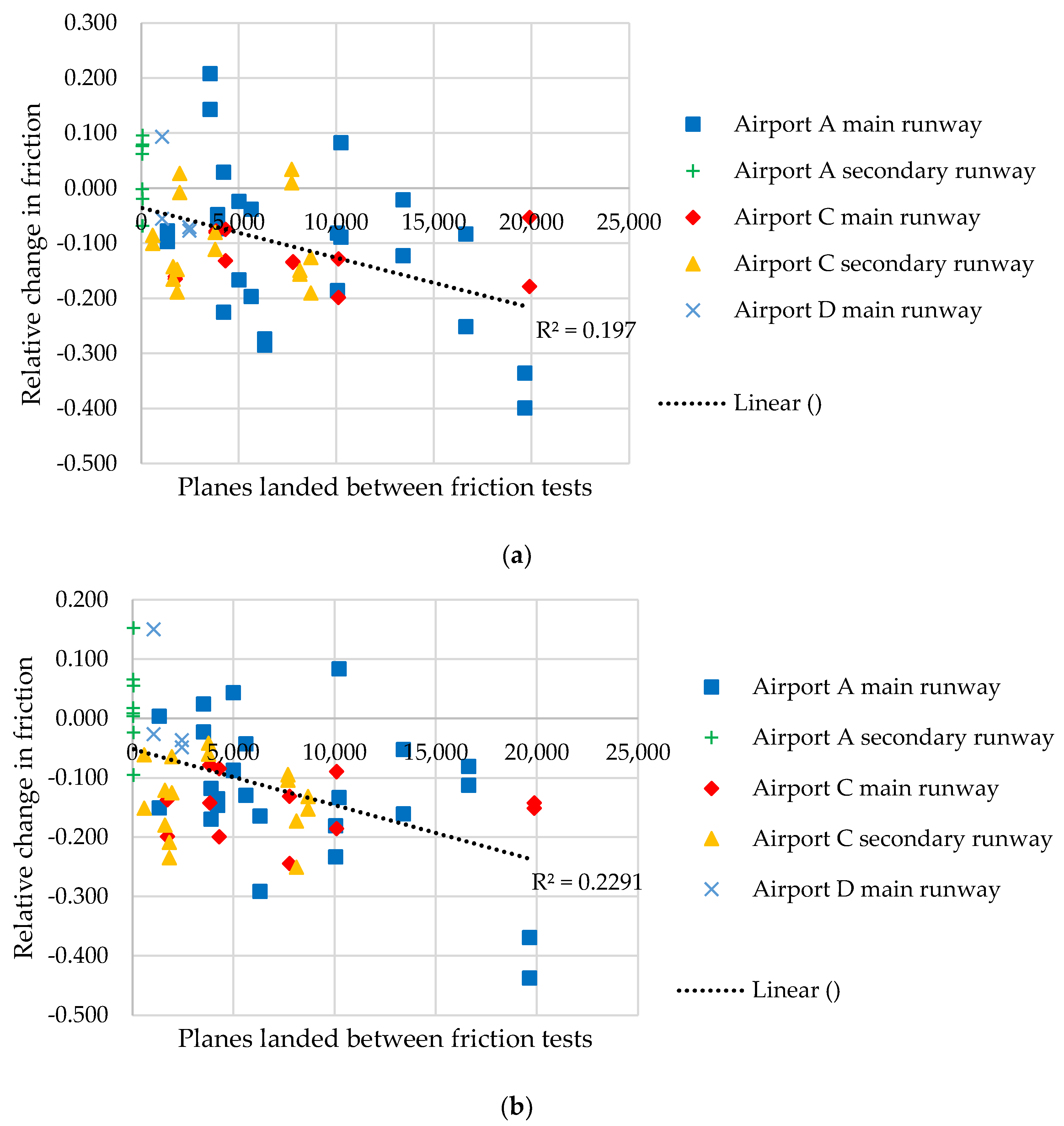

Friction reductions at the touchdown points (100 m averages) was calculated for each runway end and compared to the corresponding number of landings (

Figure 12). Data on aircraft movements and the ratio of landings on each runway end were obtained from open sources [

54,

55]. Relative friction reduction was used to account for the unevenness of the friction reduction rate.

Figure 13 shows the relative change in friction versus the number of aircraft landings across all airports, with friction measured 3 m from the centerline. Due to the high variability of the measurements, the overall correlation is low. However, the correlation is stronger for the results obtained at 95 km/h. Although this relationship does not allow for precise modeling of friction dynamics, it indicates that aircraft traffic influences the rate of friction reduction.

Table 5 presents the number of landings and relative friction reduction for the main and secondary runways of Airport A. A significant negative correlation is observed between relative friction change and the number of landings, which is stronger for the 95 km/h results.

In the case of Airport C (

Table 6), this correlation is not evident. The lack of correlation may be related to the high variability in runway usage throughout the year, which makes accurate estimation of aircraft landings difficult. Results from Airport D (

Table 7) show a significant negative correlation. However, the number of measurements is insufficient to draw definitive conclusions.

In general, there is a noticeable correlation between the number of landings and friction change at the touchdown zones, with Pearson coefficients of −0.44 and −0.47 for friction at 65 km/h and 95 km/h, respectively. One reason for the relatively low correlation is the high variability in the measurements, as observed during the analysis of calibration strip results. Friction measurements for the middle thirds of the runways (

Table 8 and

Table 9) show lower correlation, particularly for 95 km/h. This low correlation can be explained by the high variability in aircraft traffic over the middle sections, as aircraft may pass the same section twice depending on the location of exit taxiways.

ICAO recommendations do not specify the number of landings before each friction test, but rather define time-based intervals (

Table 1). According to these intervals, friction testing should be conducted after 2940–8212 landings, or approximately 5320 landings on average across all intervals. The ICAO-recommended testing intervals were compared to friction reduction rates observed at the studied airports. As a reference, friction reduction from the design objective level to the maintenance planning level was used, since data on friction reduction below the maintenance level were insufficient in the dataset. Data from the secondary runway of Airport A were also excluded due to low traffic and the high likelihood of overestimating reduction rates. Based on the existing reduction rates, the probability of friction reduction from the design objective level to the maintenance planning level between friction tests was estimated (

Table 10).

According to existing reduction rates from 4 Australian airports, friction testing intervals recommended by ICAO can allow 0.28 probability of friction reduction from design objective level to maintenance level in between tests. This value is likely overestimated due to high variance of the friction testing results; however, high variance also requires more frequent friction testing. According to the obtained data, to achieve 90% confidence, friction testing should be conducted after approximately 3200 landings for 65 km/h friction and 4000 landings for 95 km/h. These values provide updated recommended testing frequencies that ensure, with 90% confidence, that friction does not fall below the maintenance planning level between tests (

Table 11). It is important to note, however, that these reduction rates are based on Australian airports with specific climatic conditions. Hence, the obtained values may not be applicable to other regions.

At the same time, when planning friction testing, it is important to account for seasonal variability in the results. As shown in previous section, there is no reliable method to correct friction measurements based on season or temperature. However, a general awareness that friction tends to be higher during cold and dry periods can help avoid misinterpretation of the results.

4.3. Practical Recommendations Based on the Data Analysis

To ensure timely maintenance and high safety of aircraft operations, it is important to account for both testing variability and friction reduction rates during friction management planning. Analysis of friction testing results from runways and calibration strips at four Australian airports provides the following recommendations for maintenance planning and friction measurement interpretation.

4.3.1. Seasonal and Weather Variability

Friction results can vary due to seasonal and weather conditions. The analysis indicates that these changes cannot be reliably corrected. However, awareness of higher friction levels during cold and dry periods can help avoid misinterpretation of results.

4.3.2. Magnitude of Variability

Seasonal variance and variability due to testing equipment calibration are generally greater than random measurement error. Random deviations range from 0.02 to 0.06, while total deviation, including seasonal changes and equipment calibration, can reach 0.09, which is nearly as high as the difference between the maintenance planning level and the minimum friction level for the GripTester.

4.3.3. Speed Dependence of Measurements

Friction results at 65 km/h are more sensitive to errors, particularly due to seasonal effects. These results exhibit higher variance and slightly weaker correlation with the number of landings. Consequently, 95 km/h results should be prioritized in maintenance decision-making, with 65 km/h results used to confirm these decisions.

4.3.4. Friction Dynamics Post-Construction

After runway construction, friction on dense-graded asphalt shows a noticeable initial improvement, primarily due to the binder scouring effect. Following this, friction gradually decreases, with the reduction rate slowing as 100 m average friction values decline. Touchdown zones of the runway are more susceptible to friction deterioration, whereas deterioration rates are lower in the middle sections of the runway. In contrast, friction reduction for runway thirds remains relatively constant and higher, reflecting the progressive extension of rubber build-up zones. Timely rubber removal in this context can optimize maintenance costs and, in many cases, restore friction levels to values higher than those immediately after construction.

4.3.5. Recommended Testing Intervals

Current friction testing intervals do not provide sufficient confidence, as there is a significant probability of friction reduction from the design objective level to the maintenance planning level between tests. Based on the analysis, it is recommended to reduce testing intervals to approximately 3200 landings to achieve 90% confidence in timely maintenance. Additionally, friction dynamics should be monitored continuously to prevent unexpected reductions. These values, however, are based on testing results from Australian airports and may therefore be limited by specific climatic conditions.