Abstract

Natural disasters pose significant risks to engineering projects, necessitating a systematic analysis of their risk factors. This study focuses on identifying and mapping these factors using a mixed-methods approach that integrates a qualitative literature review with scientometric analysis via Social Network Analysis (SNA). Through a meta-analysis of 81 peer-reviewed articles from Web of Science, Scopus, and ScienceDirect, the qualitative review establishes a comprehensive list and classification of 48 natural disaster risk factors, categorized into geological, climatic, hydrological, topographic, and biological groups, while providing a theoretical foundation. SNA complements this by quantifying co-occurrence frequencies, centrality metrics (degree, betweenness, and eigenvector), and network structures, revealing dynamic interactions, key influential factors, and research gaps—particularly in under-explored areas like hydrological hazards, extreme temperatures, lightning storms, and temperature variations—that qualitative methods alone might miss. This multi-perspective integration highlights discrepancies between theoretical discussions and practical applications, underscoring overlooked cascading effects. Findings emphasize the absence of an integrated model for all 48 factors, urging the development of a holistic predictive framework to bolster disaster resilience. Theoretically, the study offers a novel SNA-based quantification of factor importance and interrelations, addressing literature fragmentation. Practically, it guides project managers in prioritizing risks for optimized design, resource allocation, and prevention strategies. Future research should incorporate real-time data sources to refine this framework for enhanced risk management in engineering projects.

1. Introduction

Globally, the frequent occurrence of extreme weather events exacerbated by climate change, along with other natural disasters such as earthquakes, floods, mudslides, and hurricanes, poses significant risks and challenges to the development of the construction industry and engineering projects. Typically, natural disasters can cause large-scale damage to both ongoing and completed projects [1]. For instance, the 2023 earthquake in Turkey and Syria led to the collapse of thousands of buildings and caused severe damage to critical infrastructure [2]. According to data from the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR), approximately 350 to 500 natural disasters occur globally each year, and this number is on the rise. The sudden nature of natural disasters often results in varying degrees of damage to construction projects or completed infrastructure. Due to their scale and unpredictability, natural disasters pose greater threats to engineering projects than other destructive forces [3].

Since the mid-20th century, the impact of natural disasters on engineering projects has attracted widespread attention, especially amid the large-scale construction of infrastructure projects. Natural disasters can cause severe damage to engineering projects, including structural damage, functional failure, and long-term safety concerns. The impact of natural disaster risks on engineering projects has long drawn extensive attention from academia and industry [4]. With the acceleration of global climate change and urbanization, the frequency and destructive power of natural disasters are increasing, introducing substantial uncertainty and risk to engineering projects. Considerable research has been devoted to assessing [5] and managing [6] the vulnerability and risk of engineering projects to natural disasters. As a result, research on the resilience of engineering projects has gained increasing focus, aiming to enhance their ability to withstand natural disasters. For example, Ouyang et al. proposed a resilience assessment framework for urban infrastructure systems [7].

Research on natural disasters affecting engineering projects is of significant importance [8]. In the past 30 years, with the implementation of the International Strategy and Action Plan for Disaster Reduction, disaster reduction science has become a global hotspot. By reviewing the knowledge system of natural disaster risk factors for engineering projects, it is evident that previous research mainly focused on a single natural disaster risk factor, such as floods [9], earthquakes [10], hurricanes [11], landslides [12], rockfalls [13], collapses [14]. In previous research, methods such as BP neural networks [15], disaster mapping and risk assessment [16], event maps [17], natural disaster knowledge map [18], multiple linear regression analysis [19], and others were used to conduct in-depth explorations of specific natural disasters in engineering projects, which have contributed to mitigating the impacts of natural disaster risks on engineering projects.

Overall, although existing studies have analyzed natural disaster risk factors affecting engineering projects through various methods, a comprehensive list of natural disaster factors for engineering projects has not been established [20]. While significant progress has been made in analyzing the risks of natural disasters for engineering projects, the frameworks used in practical applications remain insufficiently systematic and comprehensive. Most research focuses on one or a few specific natural disaster risk factors, conducting either risk assessments or analyses of natural disasters without specifying particular risk factors, which results in broad generalizations and a lack of systematic understanding of natural disaster risk factors within engineering projects. Furthermore, there may be linkage or superimposed effects among these natural disasters [21]. For instance, an earthquake may trigger flooding, especially when it causes dam failures or landslides [22]. The lack of an integrated framework means that some critical factors may be overlooked in the assessment process, or the interactions between disasters may not be systematically considered, which constitutes a critical knowledge gap and limits the forward-looking development of natural disaster risk prediction for engineering projects. Consequently, researchers and engineers have emphasized the need to establish an integrated framework. Such a comprehensive list would not only enhance the resilience of engineering projects, reducing disaster-related losses, but also promote more scientific resource allocation and emergency response. Moreover, clarifying the interactions among natural disasters could provide policymakers with a basis for optimizing disaster risk management and urban planning, ensuring sustainable development.

This study employs a mixed-methods approach, combining a qualitative literature review with scientometric analysis to achieve a comprehensive examination of natural disaster risk factors in engineering projects. The qualitative review systematically synthesizes existing literature to identify and classify 48 core risk factors, providing the theoretical foundation and conceptual framework. However, traditional qualitative methods are often limited to descriptive analysis and are insufficient for capturing the dynamic interactions among factors. To address this limitation, we introduce Social Network Analysis (SNA) as a scientometric tool. Its relevance lies in its graph-theoretical basis, which enables the quantification of co-occurrence frequencies and centrality measures of risk factors, revealing research hotspots, gaps, and potential cascading effects. This quantitative supplement not only validates the reliability of the qualitative classification but also visualizes the overall structure of the risk network, offering multi-level insights and providing a research foundation for future disaster assessments in engineering projects. This paper analyzes 81 articles to examine the risk factors they address, systematically identifying natural disaster risk factors in engineering projects and constructing both the factor network and the factor model network. The study identifies key natural disaster risk factors as well as factors overlooked during the research process, revealing the complex relationships among these risk factors.

Compared with the existing literature, the primary contributions of this study are threefold:

- Comprehensive identification and systematization of risk factors: This is the first study to systematically identify, classify, and compile a complete set of 48 natural disaster risk factors through rigorous comprehensive analysis. Building on this foundation, we construct a detailed factor network and corresponding model network, providing a structured and exhaustive reference framework that was previously lacking.

- Novel integration of methodological approaches: We propose a unique hybrid framework that combines simplified analytical methods with SNA. This multi-level approach not only bridges the gap between theoretical risk discussions and practical modeling applications but also enables dynamic visualization of the interrelationships and structural evolution among risk factors. Compared with traditional linear or single-method analyses, our approach significantly enhances the reliability, depth, and interpretability of complex system evaluations.

- New insights into overlooked hazards and practical implications: The study uncovers the low network connectivity and potential cascading effects of traditionally neglected risk factors, including hydrological hazards, extreme temperatures, lightning storms, and temperature variations. These findings highlight the urgent need for integrated, multi-hazard predictive models and offer actionable, evidence-based guidance for project managers to improve engineering design, optimize resource allocation, and strengthen disaster prevention and mitigation strategies.

The writing framework of this paper is as follows: The second part describes the literature review; the third part introduces the research methods, including simplified analysis and SNA; the fourth part discusses the results. The fifth part presents the final conclusion.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Natural Disaster Risk

Defining natural disasters in the context of engineering projects is complex, as highlighted by Lukic et al., who note the challenge of establishing a universally accepted definition, even when disasters are clearly identifiable [23]. A review of existing literature suggests a general definition of natural disasters in engineering projects as extreme environmental events caused by natural processes or phenomena, such as earthquakes, hurricanes, floods, and landslides [24]. These events can cause significant damage to civil engineering structures, disrupt social and economic systems, and impair infrastructure and essential services.

Natural disaster risk factors for engineering projects are typically categorized into five groups [25,26]: geological factors (e.g., earthquakes, geological structures, and conditions), climatic factors (e.g., storms, rainstorms, tornadoes, blizzards), hydrological factors (e.g., floods, tsunamis, sea-level rise), topographic factors (e.g., topography, elevation), and biological factors (e.g., fires, pests), or any combination thereof. To synthesize these classifications, recent reviews have mapped the evolution of risk frameworks, revealing a shift from isolated disaster assessments toward integrated resilience models that account for climate-amplified interactions [27]. For example, early studies emphasized probabilistic modeling of single events, such as earthquakes [28] or floods [29], whereas more recent integrated analyses highlight the need for holistic quantification of resilience, critiquing traditional metrics for underestimating the recovery dynamics of urban infrastructure [30]. This evolution underscores a critical gap: despite progress in earthquake risk factors, comprehensive lists remain fragmented and often overlook cascading effects, such as hydrological surges triggered by earthquakes.

Understanding the characteristics of natural disaster risks is critical for engineers and decision-makers in developing targeted preventive measures and ensuring effective disaster response [31]. Such understanding also facilitates the assessment of potential chain reactions triggered by natural disasters, enabling more comprehensive risk evaluations [32]. A literature review identifies the following characteristics of natural disaster risk factors [33]: (1) high unpredictability; (2) large-scale impact, often affecting multiple projects or entire regional infrastructures; (3) sudden onset, causing significant damage in a short time; (4) potential for chain reactions, such as earthquakes triggering landslides; and (5) long-term impacts. These characteristics underscore the need for comprehensive risk assessment and management to minimize the potential impacts of disasters on engineering projects.

In synthesizing previous work, studies have explored various natural disaster risk factors, including rapid assessment techniques for earthquake disaster losses [28], flood risk management [29], fuzzy comprehensive evaluation of collapse risks in mountain tunnel construction [34], comprehensive management of short-term extreme rainfall threats [35], deterministic modeling of dredging project durations [36], and a comprehensive index system for landslide susceptibility along highways [37]. However, as highlighted by reviews of construction disaster systems from 2010 to 2025 [38], these approaches often prioritize methodological trends at the expense of interdisciplinary integration, resulting in the neglect of socio-economic amplifiers within the civil engineering context [30]. This fragmentation limits holistic understanding and calls for the adoption of a unified framework aligned with global risk reporting.

Natural disasters pose significant risks to engineering projects, prompting extensive literature reviews to enhance understanding of these risks. Despite considerable progress, most studies focus on specific risks, assessing their magnitude, probability, and mitigation strategies, rather than providing a holistic understanding of the natural disaster risk system affecting engineering projects. Critically, this siloed approach—as evident in reviews of infrastructure projects identifying 128 cross-category risks [39]—fails to address interdependencies, such as how climatic factors may amplify geological vulnerabilities. Consequently, a comprehensive list of natural disaster risk factors for engineering projects has yet to be established. This paper employs SNA to identify these risks, create a comprehensive risk list, clarify the relationships among risk factors, and highlight the most critical factors.

2.2. Social Network Analysis

2.2.1. SNA Applications in Engineering Projects

In engineering projects, SNA is a method that examines networks composed of nodes and edges to study social structures, focusing on relationships among entities and their formation into complex network structures for systematic analysis and visualization [40]. Over the past two decades, SNA has gained prominence in construction engineering and management (CEM) as projects are increasingly viewed as organizational networks [41]. For instance, Trach et al. applied SNA to evaluate communication quality among construction project participants, identifying key factors affecting communication and addressing low delivery efficiency [42]. He et al. employed Social Network Analysis to quantify the systemic risk and vulnerability of power grid disasters. They identified and analyzed the key risk factors of power grid disasters, constructed a power grid disaster system, and used the SNA framework to identify the core risk factors and critical combinations of risk factors in power grid disasters [43]. Similarly, Zheng et al. reviewed SNA applications in construction project management, addressing gaps through literature analysis, including applications in subway construction collapse accidents and freeway data decision networks [44]. Hazarika et al. explored SNA’s application in natural disaster risk management for engineering projects [45]. They assessed the impact of natural disasters on project resilience and analyzed interrelationships among risk factors. Using SNA, researchers identified critical nodes and information flow paths essential in disaster scenarios, proposing strategies to enhance project resilience and demonstrating SNA’s effectiveness in managing complex risk networks. Shan and Zhao [46] proposed a social network analysis (SNA) framework based on social media to assess disaster recovery and resilience in terms of infrastructure and psychological states. This framework aids disaster emergency management departments in formulating more precise and effective decisions for post-disaster reconstruction and psychological interventions, while providing references for enhancing urban disaster resilience. Wang et al. [47] applied SNA to HSE (Health, Safety, and Environment) risk network analysis, laying the foundation for disaster risk assessment and supporting multi-stakeholder coordination. They also proposed risk classification early warning and control strategies to rationally allocate emergency resources. Yang et al. [48] visualized flood risk networks using SNA, supporting the assessment and prediction of flash flood disasters. Shen et al. [49] applied SNA indicators to risk networks in large-scale programs, identifying cross-project dependencies and enhancing risk mitigation strategies.

2.2.2. Reasons for Selecting SNA

SNA is instrumental in revealing relationships between research literature [50,51,52]. SNA’s utility in complex project management has been demonstrated by Lee et al., who highlighted its effectiveness in analyzing non-human resource networks, aiding strategic planning, and improving project delivery and interdisciplinary interactions [53]. Various methods have been used to analyze natural disaster risk factors, each with distinct benefits. For example, the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) decomposes complex decision-making into hierarchical structures, determining factor weights through pairwise comparisons; Badea et al. used AHP to analyze supply chain collaboration barriers [54]. The Delphi method identifies and prioritizes risks through iterative expert consultations, as seen in Pratama et al.’s study of 28 toll road operation risks in Sumatra [55]. In another case, AHP was applied to assess flood risk in Malda, India, improving disaster map accuracy [56].

This paper adopts SNA for the following reasons: (1) SNA effectively captures the complex relationships and interactions among numerous natural disaster risk factors using graph theory and network structures, providing a global perspective; (2) it identifies key nodes and pathways; (3) it offers robust visualization tools; and (4) it integrates data from diverse sources to build comprehensive risk networks. Compared to other traditional methods, SNA exhibits significant advantages in capturing the dynamic correlations of risk factors and quantifying network structures. AHP determines factor weights through pairwise comparisons and hierarchical decomposition, making it suitable for linear decision structures, but it struggles to handle nonlinear dynamic interactions between risk factors, such as the cascading effects of earthquakes inducing floods, leading to the neglect of potential bridging paths and amplification mechanisms in complex networks [54,57]. Similarly, the Delphi method relies on iterative expert consensus to prioritize risks, excelling in the subjective evaluation of single or few factors, but it is limited by expert biases and static feedback loops, and is unable to quantify global connectivity and evolutionary dynamics among multiple factors, such as topological changes in risk networks under climate change [55,58]. In contrast, SNA, based on a graph theory framework, can dynamically map multidimensional correlations between risk factors through co-occurrence frequency and centrality metrics (such as degree centrality), while visualizing network density and modular structures to reveal hidden cascading risk paths, thereby providing more comprehensive system-level insights [50,51,52]. This methodological innovation not only enhances the robustness and interpretability of risk assessment but also lays a quantitative foundation for constructing multi-hazard prediction models in engineering projects [57].

2.2.3. Integration with Factor Analysis and Literature Review

The integration of SNA with factor identification and analysis has been applied in previous studies on engineering project risks beyond natural disasters. Researchers have treated factors as nodes within SNA frameworks. For instance, Wang et al. used SNA to identify key safety risk factors in marine bridge construction [59], while Li et al. identified nine social risk factors and 12 stakeholders in infrastructure projects [60]. Aghililotf et al. applied SNA to analyze construction industry challenges, identifying key issues through network analysis [61]. In these studies, factors are represented as nodes connected to form a network. This paper adopts a similar logic, treating natural disaster risk factors as nodes in an SNA framework.

Literature reviews integrated with SNA have also been employed previously. For example, Assaad and El-adaway reviewed 43 journal articles to identify 20 factors contributing to the failure of design and construction companies, using SNA to highlight neglected factors [62]. Schreiber et al. conducted a systematic literature review on software development projects, emphasizing SNA’s importance [63]. Tai et al. built an SNA model to analyze factors affecting BIM adoption in China’s construction industry [64]. This paper similarly combines SNA with a literature review to identify natural disaster risk factors in engineering projects, building on existing research to analyze SNA’s application.

2.2.4. Provided Benefits

Using SNA to analyze natural disaster risk factors in engineering projects leverages centrality indices to measure node importance or influence within a network. Key centrality measures include:

- 1

- Degree Centrality: Reflects the number of connections a node has, indicating its direct influence. High degree centrality suggests a factor significantly impacts others, marking it as a key network member [65];

- 2

- Betweenness Centrality: Measures how often a node lies on the shortest paths between other nodes, reflecting its role as a bridge or intermediary [66];

- 3

- Eigenvector Centrality: Considers both the number and importance of a node’s connections, with higher centrality indicating connections to other influential nodes [67].

These centrality measures provide a deeper understanding of network structures [68], aiding in the development of effective policies and decisions. In this paper, degree centrality, calculated from co-occurrence frequency matrices, ranks the importance of natural disaster risk factors. This approach aligns with prior studies, such as Darko et al., who used degree centrality to analyze global green building research trends [69], and Yuan et al., who assessed key risk factors and stakeholders in high-density urban construction projects through co-occurrence and degree centrality analysis [70].

These centrality measures enable a deeper understanding of the network structure and provide hazard-specific insights into natural disaster risk networks, thereby supporting effective policy and decision-making. Degree centrality quantifies the direct exposure of each factor—analogous to assessing hazard frequency—and helps prioritize high-frequency risks (e.g., earthquakes). Betweenness centrality reveals the role of bridging nodes and maps potential cascading pathways (e.g., earthquakes triggering landslides), allowing interventions to target key intermediaries. Eigenvector centrality captures indirect amplification effects, reflecting system-level vulnerabilities (such as climatic factors amplifying hydrological risks through topographic conditions). This combination is well suited to the context of engineering projects, where disaster risks often manifest as asymmetric networks—dominated by a small number of highly influential factors—rather than evenly distributed interactions [69,70].

3. Research Methods

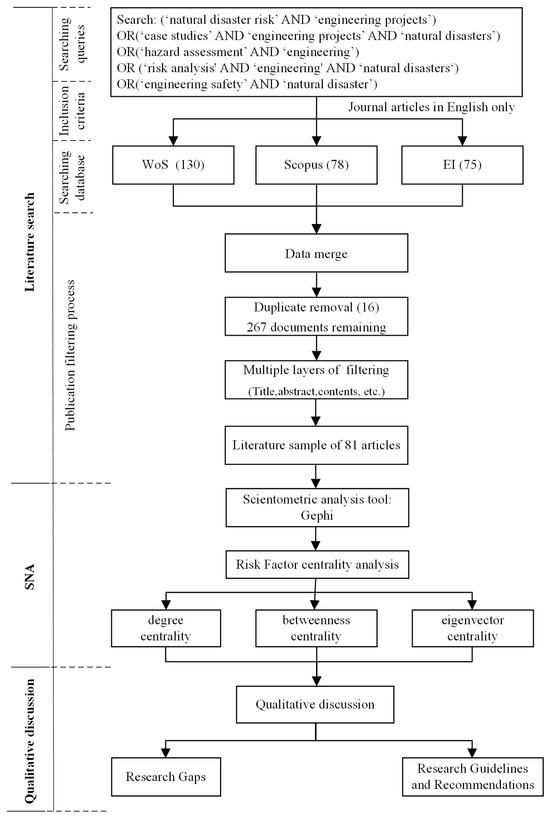

The authors conducted a meta-analysis of literature addressing natural disaster risk factors in engineering projects to achieve three objectives: (1) identify key natural disaster risk factors affecting engineering projects, (2) determine under-researched risk factors requiring further investigation, and (3) highlight the need for a holistic and comprehensive model to predict and mitigate natural disaster risks. The research framework is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research framework.

To ensure objectivity and reproducibility, this study predefined the parameters and criteria for identifying risk factors. First, based on predefined search terms, a systematic literature review was conducted using three databases: Web of Science, Scopus, and ScienceDirect (EI) [71]. A total of 130 articles were retrieved from Web of Science, 78 from Scopus, and 75 from ScienceDirect. After removing duplicates—15 overlapping articles between Web of Science and Scopus, and 1 between Scopus and ScienceDirect—283 articles were identified, and 16 duplicates were excluded, resulting in 267 articles. The complete list of all 283 articles is provided in Appendix A.1. These articles were screened based on three criteria: (1) relevance to natural disaster risk: ensuring that the articles explicitly address hazards such as earthquakes, floods, or storms, while excluding general climatic or anthropogenic risks that may dilute the focus on unpredictable, large-scale natural events relevant to engineering vulnerability; (2) pertinence to the construction industry: strictly limit the inclusion scope to the civil engineering context of the primary disaster-affected domains under discussion; and (3) focus on construction projects: focusing on project-specific analyses (e.g., risk assessment during the design or construction phases) rather than post-disaster recovery of completed structures. After screening, 44 articles were excluded for not addressing natural disaster risk, 120 for not pertaining to the construction industry, and 169 for not focusing on construction projects. Ultimately, 81 articles were selected for analysis of natural disaster risks in engineering projects. Finally, risk factors were extracted using content analysis, with co-occurrence frequency serving as the initial activation criterion. Following Newman’s [72] network density principle to avoid noisy nodes, factors were included as network nodes only when they co-occurred in three or more articles. The classification of risk factors followed the five-category framework of Blaikie et al. [25], and the SNA parameters included degree centrality, betweenness centrality, and eigenvector centrality. These criteria ensured the transparency and objectivity of factor identification, avoiding potential biases.

3.1. Meta-Analysis of the Literature

Following the approach of Ciurean et al. [73], which integrates theoretical discussion and modeling, the selected articles were categorized into two types: (1) studies focusing on theoretical aspects of natural disaster risk factors, and (2) studies combining theoretical and practical perspectives by examining the impacts of these risk factors.

Type 1: These articles provide theoretical discussions on natural disaster risk factors and their influence on engineering projects. Here, “theoretical discussion” refers to abstract or conceptual analyses without employing statistical, machine learning, or other mathematical/computational models. In this study, papers with theoretical discussions are denoted by the letter “M.”

Type 2: These articles combine theoretical discussions (similar to Type 1) with predictive models based on selected natural disaster risk factors. Papers developing such models are denoted by the letter “S,” indicating both theoretical mention (M) and model formulation (S).

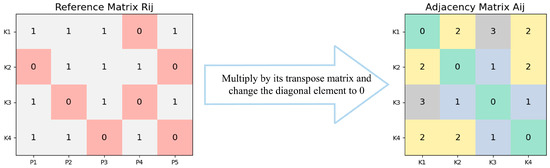

A reference matrix was constructed, with natural disaster risk factors as rows and the 81 selected articles as columns. Each cell indicates whether a specific risk factor is mentioned or used in a given paper (1 for mentioned/used, 0 otherwise). A hypothetical diagram of the reference matrix, illustrating its transformation into an adjacency matrix, is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Adjacency matrix diagram.

The reference matrix “M” represents articles (Type 1) that provide theoretical discussions on natural disaster risk factors in engineering projects. Its purpose is to map the overall academic and professional discourse on these risk factors and identify those deemed most significant. The reference matrix “S” represents Category 2 literature, namely studies that construct predictive models based on specific natural disaster risk factors. Here, a “predictive model” refers to a quantitative or simulation-based framework used to estimate the potential impact of natural disaster risks on engineering projects. Such models typically employ mathematical, statistical, or computational methods to simulate scenarios and predict outcomes—for example, finite element analysis (FEA) models used to predict structural responses under earthquakes [10], or Monte Carlo simulation models used to assess flood inundation risks and the probabilistic failure rates of hydraulic infrastructure [9]. By incorporating empirical data and validation techniques, these models bridge the gap between theoretical risk discussions and engineering practice. The reference matrix “S” represents articles (Type 2) that develop predictive models based on specific natural disaster risk factors. Its purpose is to highlight the risk factors incorporated into existing models. By comparing matrices M and S, this study identifies discrepancies between risk factors discussed in theory and those applied in predictive models, addressing a key research question: which natural disaster risk factors are under-researched or overlooked in engineering projects, and which should be prioritized for future study?

Based on the reference matrices, two analytical approaches were employed: simplified analysis and SNA. In analyzing natural disaster risk factors for engineering projects, combining simplified analysis with SNA provides multi-level insights into the complex relationships and overall structure of these risk factors. This integrated approach not only underscores the importance of individual risk factors but also reveals their interactions and influence within disaster response or prediction frameworks [74].

SNA offers distinct advantages over simplified analysis, particularly in elucidating complex relational structures and dynamics. It enables a deeper examination of relational networks within disaster management, identifying critical nodes with high centrality or connectivity. This method is particularly effective for capturing intricate interactions, such as multi-stakeholder collaboration and rapid response needs, which simplified analysis often fails to address [75]. When discrepancies arise between simplified analysis and SNA results, SNA is prioritized because it more comprehensively captures complex relational networks and their influence. By revealing key relationships and core nodes that simplified analysis may overlook, SNA provides a more accurate perspective on network dynamics, making it more reliable for analyzing complex systems [76].

3.2. Simplified Analysis

Simplified analysis involves reviewing the literature to identify future research needs by calculating the frequency of occurrence of natural disaster risk factors across previous studies. For this analysis, the reference matrix M is used to compute a score for each natural disaster risk factor by summing the values in each row, as shown in Equation (1). For example, a score of 16 for natural disaster risk factor F1 indicates that it was mentioned or discussed in 16 source papers. To enable comparison, the score for each factor is normalized by dividing it by the maximum score in the matrix, as shown in Equation (2). Thus, the normalized score for any natural disaster risk factor ranges from 0 to 1 (inclusive).

where is the total score for natural disaster risk factor across all sources, and represents the value (1 or 0) of the cell corresponding to source and risk factor in the matrix.

3.3. Social Network Analysis

3.3.1. Adjacency Matrices Formation and Analysis

To perform SNA, the adjacency matrix is generated from the reference matrix (48 × 81), which indicates the presence of natural disaster risk factors in the literature. Specifically, the process is divided into two main steps: (1) constructing the reference matrix (literature-risk factor matrix), which records the occurrence of each risk factor in the 81 selected papers; and (2) deriving the adjacency matrix (risk factor-risk factor co-occurrence matrix) from the reference matrix, quantifying the interactions between factors. First, in the construction of the reference matrix, risk factors are extracted from the title, abstract, keywords, and body of each paper according to three predefined criteria, and classified using the five-category framework of Blaikie et al. (geological, climatic, hydrological, topographical, and biological). The matrix uses binary coding (1 for the presence of the factor, 0 for its absence) to avoid subjective weight bias. If risk factor appears in paper , then ; otherwise, . By multiplying by its transpose and setting the diagonal elements to 0, the adjacency matrix (48 × 48) is generated, resulting in a symmetric matrix. In this matrix, both rows and columns represent natural disaster risk factors, and the cell values indicate the frequency of co-occurrence of risk factors in the source literature. The process of generating the adjacency matrix is illustrated in Figure 2.

The adjacency matrix is imported into Gephi software (version 0.9.1) for network visualization, enabling a graphical representation of the relationships among risk factors.

Degree centrality for each natural disaster risk factor is calculated using Equation (3), where represents the degree centrality of risk factor , and is the value in row and column of the adjacency matrix. To account for variations in network size, degree centrality is normalized by dividing it by the maximum degree centrality in the network, as shown in Equation (4). The normalized degree centrality for any risk factor ranges from 0 to 1.

3.3.2. Risk Factor Centrality Analysis

SNA indicators provide valuable insights into the distribution and relational patterns within the network of natural disaster risk factors. The key SNA indicators used are degree centrality, betweenness centrality, and eigenvector centrality:

- 1

- Degree Centrality: Calculated using Equation (3), this measures the number of direct connections a risk factor has, indicating its influence within the network.

- 2

- Betweenness Centrality: Calculated using Equation (5), this measures the extent to which a node lies on the shortest paths between other nodes, reflecting its role as an intermediary.

- 3

- Eigenvector Centrality: Calculated using Equation (6), this considers both the number and importance of a node’s connections.

4. Analysis and Results

Through analysis of the 81 selected articles, 48 natural disaster risk factors for engineering projects were identified, as listed in Table 1. Two matrices were constructed: the reference matrix M, capturing theoretical discussions of natural disaster risk factors and their sources (papers), and the model matrix S, representing risk factors used in predictive models. Of the 81 articles, 40 belong to Type 1 (theoretical discussions, forming matrix M), and 41 belong to Type 2 (theoretical discussions with predictive models, forming matrix S).

Table 1.

Natural disaster risk factors of engineering projects.

4.1. Simplified Analysis and Social Network Analysis

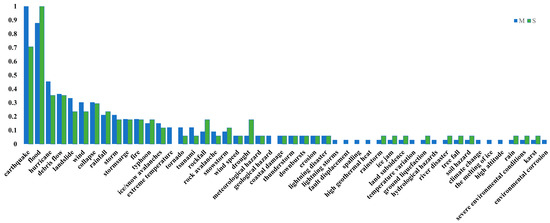

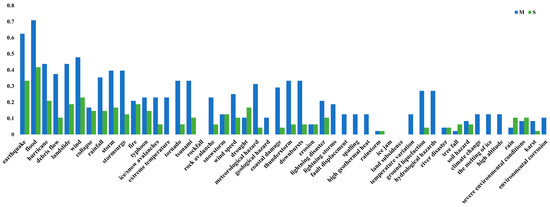

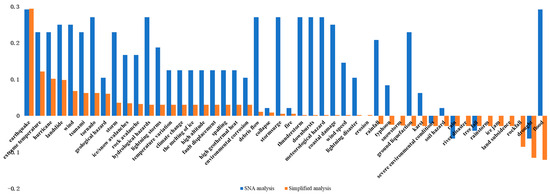

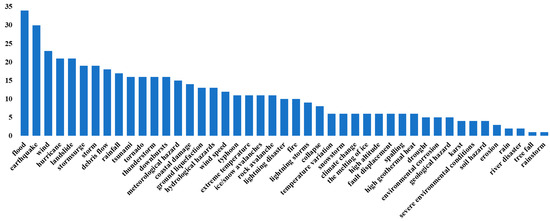

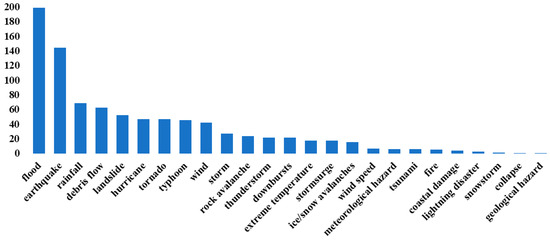

Both the reference matrix M and the model matrix S were analyzed using simplified analysis and SNA, with results presented in Figure 3 and Figure 4, respectively. The scores for each factor from both simplified analysis and SNA are provided in Appendix A.2.

Figure 3.

Obtained normalized scores for the simplified analysis.

Figure 4.

Obtained normalized scores for the SNA.

Figure 3 shows the occurrence frequency and normalized scores of natural disaster risk factors in the theoretical literature (matrix M). It can be seen that F8 (earthquake) and F5 (flood) have the highest scores, indicating that they receive the most attention in disaster research for engineering projects. In contrast, some factors, such as F36 (hydrological hazards) and F19 (extreme temperature), have lower scores, suggesting that although they are mentioned in some studies, they receive relatively little overall research attention. This trend reflects a bias in existing research toward high-impact but less diverse types of disasters.

Figure 4 shows the normalized degree centrality of nodes in the co-occurrence network constructed from matrix M. The results are highly consistent with Figure 3, with F8 (earthquake) and F5 (flood) remaining the most central nodes, having the highest number of connections. Notably, Figure 4 further reveals the relational structure among factors: for example, meteorological factors (such as F1, F2, and F20) form distinct highly connected clusters, while biological factors (such as F38, tree fall) exhibit significantly lower centrality. This indicates that the former are more likely to co-occur with other disasters, whereas the latter are often studied in isolation.

Figure 3 and Figure 4 also reveal discrepancies between the theoretical discussions in matrix M and the risk factors incorporated into predictive models in matrix S. The simplified analysis highlights a significant gap for F8 (earthquake), which is even more pronounced in the SNA. This discrepancy suggests that the research attention devoted to certain risk factors, particularly earthquakes, does not align with their inclusion in predictive models, indicating under-exploration in practical applications. Additionally, risk factors such as F36 (hydrological hazards), F19 (extreme temperature), F10 (lightning storms), F25 (temperature variation), F41 (climate change), F42 (ice melting), F43 (high altitude), F13 (fault displacement), F15 (spalling), F16 (high geothermal heat), F48 (environmental corrosion), and F29 (geological hazards) are frequently mentioned in theoretical discussions (matrix M) but are absent from existing predictive models (matrix S), highlighting significant research gaps.

Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8 show the normalized degree centrality of natural disaster risk factors in engineering projects, calculated based on networks M and S. The depth of the color represents the strength of the factor’s centrality and the intensity of its connections, with darker colors indicating greater strength. The size of the nodes is proportional to the normalized degree centrality of the risk factors, while the thickness of the links between nodes reflects the co-occurrence frequency in the matrices.

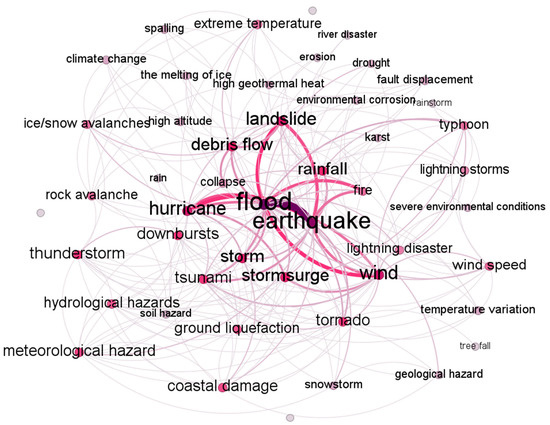

Figure 5.

Co-occurrence map of natural disaster risk factors.

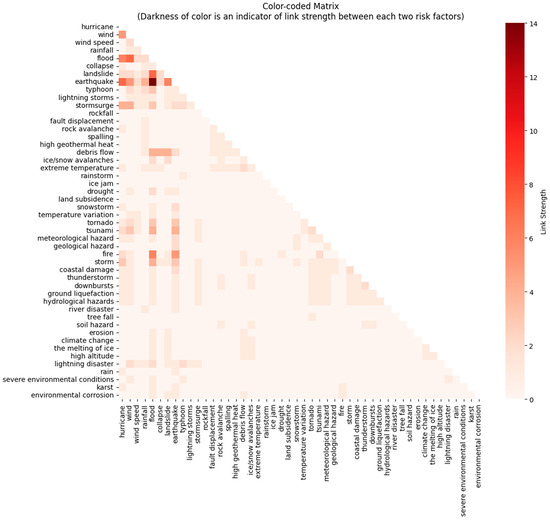

Figure 6.

Connection strength diagram of different nodes in M matrix.

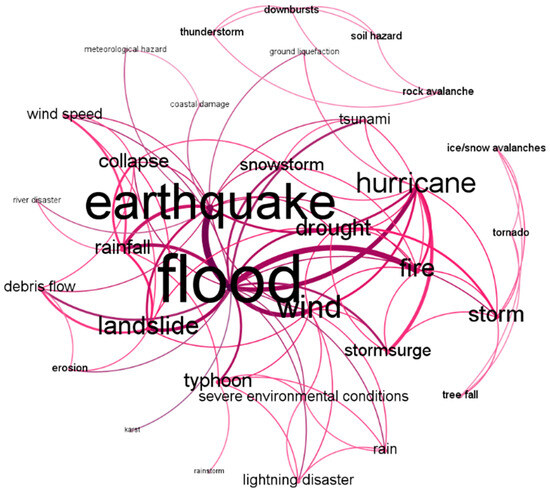

Figure 7.

Co-occurrence diagram of natural disaster risk model.

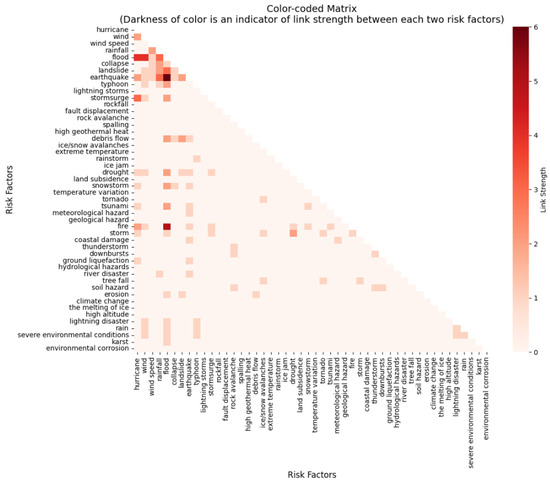

Figure 8.

Connection strength diagram of different nodes in S matrix.

Figure 5 illustrates the co-occurrence network of natural disasters based on theoretical discussions (matrix M). In the figure, the size and color intensity of the nodes reflect the level of degree centrality, and the links represent the strength of co-occurrence. The network exhibits a clear “core–periphery” structure: F8 (earthquake) and F5 (flood) occupy the network center and frequently co-occur with multiple categories of risks, such as meteorological, geological, and hydrological factors, indicating strong systemic connectivity. In contrast, nodes such as F21 (ice jams) and F38 (tree fall) are located at the network periphery, suggesting that they are relatively isolated in existing theoretical research and lack systemic connections.

Figure 6 presents the strength of connections between factors in network M in a matrix format. The figure shows that disaster combinations such as earthquake–landslide, flood–storm, and storm–hydrological hazards exhibit the highest co-occurrence intensity, reflecting a strong focus in the literature on potential cascading disasters. In contrast, biological or ecological hazards generally show lower connectivity. These results support the structural features displayed in Figure 5, indicating that theoretical research tends to focus on typical disaster combinations.

Figure 7 and Figure 8 illustrate the co-occurrence relationships of natural disaster risk factors in network S. These visualizations, based on simplified analysis, reveal the association patterns among the factors and their frequency of occurrence.

Figure 7 illustrates the co-occurrence network in predictive model-related literature (matrix S). Compared with Figure 5, network S is noticeably sparser, with a higher concentration of core nodes. F8 (earthquake) and F5 (flood) remain at the center, but the number of their connections with other factors is significantly lower than in matrix M, indicating that the risk factors included in actual predictive models are far fewer than those discussed theoretically. Many factors, such as F36 (hydrological hazards) and F19 (extreme temperature), are frequently discussed in the literature but rarely incorporated into models, highlighting a clear gap between theory and practice. Figure 5 and Figure 7 reveal the implications of the core–periphery structure for the resilience framework: the high centrality of earthquakes and floods indicates their dominance in information flow, akin to hubs in disaster propagation. Within the framework of Ouyang et al. [7], this guides the prioritization of strengthening “bridging resilience”—for example, monitoring earthquake-induced hydrological pathways through sensor networks to reduce cascading failure rates. Although peripheral nodes have low visibility, they exhibit high radiative effects, exposing model blind spots and causing predictive bias.

Figure 8 further quantifies the co-occurrence strength of factors in network S. It can be observed that the combinations of factors considered in model-based studies are very limited, primarily focusing on small, classical combinations such as earthquake–landslide and flood–storm. Many cells in the matrix are zero, indicating that model-based studies make very limited use of multi-hazard coupling relationships. Notably, theoretically important climate-related factors (such as F19, F25, and F41) are almost entirely absent from the models, reflecting the structural limitations of current predictive models.

Figure 6 and Figure 8 show that networks M and S exhibit similarities in normalized degree centrality. The matrices are color-coded, with cell colors representing the strength of connections between pairs of natural disaster risk factors. For instance, F8 (earthquake) shows high normalized degree centrality in both networks, indicating that it is frequently mentioned in theoretical discussions and is also incorporated into predictive models. However, the co-occurrence heatmap highlights dense clustering in the geological–climate cluster, which goes beyond visual repetition and implies that the resilience framework needs to shift from static classification to modularization.

Figure 9 illustrates the score differences between the simplified analysis and SNA for matrices M and S. The results indicate a significant gap between theory and models: for example, F8 (earthquake) is highly prominent in the literature, but its centrality in models shows the most pronounced decline; meanwhile, some climate-related factors receive moderate scores in theory but are almost absent in models. This discrepancy suggests that future predictive models should more comprehensively consider factors frequently discussed in the literature but not yet incorporated, in order to enhance the completeness and effectiveness of the models. The difference between Matrix M and Matrix S reveals the gap between theoretical understanding and practical modeling: Network M has higher connectivity and density, indicating that the interconnections between risk factors are more thoroughly discussed in the theoretical literature, whereas Network S has lower density, with many widely discussed factors only frequently appearing in theory but rarely included in models.

Figure 9.

Obtained differences in M and S matrix scores using simplified analysis and SNA.

Although consensus factors such as earthquakes and floods occupy the core of the network, SNA reveals deeper amplification effects: these nodes do not dominate in isolation but amplify the influence of peripheral factors through high-betweenness bridging (e.g., earthquakes connecting geological and hydrological modules). For instance, extreme temperatures, though not high-frequency, act as amplifiers within the climate subnetwork. They are frequently discussed in theory but rarely incorporated into models, exposing a gap between practice and research. This gap points to cascading risk blind spots (e.g., temperature variability triggering increased flood intensity) and suggests new priorities for engineering design: not only reinforcing core hazards but also integrating the network resilience of peripheral factors. Furthermore, network module analysis shows asymmetric interactions among the five categories of factors (e.g., the biological factor module is isolated, with centrality <0.2), challenging the completeness of traditional classifications and calling for multi-hazard simulations.

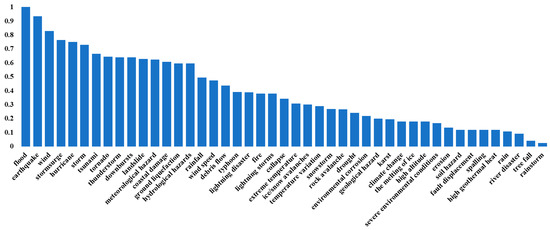

4.2. Risk Factor Centrality Analysis

Centrality analysis was conducted on network M to assess the theoretical importance of natural disaster risk factors in academic discussions. Analyzing matrix M through SNA centrality measures reveals which risk factors are widely recognized as significant, forming the theoretical foundation for further research [65]. In contrast, centrality analysis of matrix S (practical application) may not fully capture the general importance of risk factors, as model development often depends on specific contexts and needs. Thus, other analytical methods, such as frequency statistics or context-specific matching analysis, may be more appropriate for matrix S to reflect the actual application of risk factors in predictive models [77]. The centrality measures applied to matrix M are detailed below. Using graph theory and statistical methods, three key centrality metrics were analyzed for network M.

Figure 10 shows that F5 (flood) and F8 (earthquake) have the highest degree centrality, indicating that projects affected by these disasters are highly likely to experience chain reactions with other disasters. This suggests that risk prevention and assessment efforts should prioritize factors with high centrality.

Figure 10.

Degree centrality ranking of natural disaster risk factors.

Figure 11 indicates that F5 (flood) and F8 (earthquake) also dominate in betweenness centrality, underscoring their critical role as intermediaries connecting other risk factors in the network.

Figure 11.

Betweenness centrality ordering.

Figure 12 reveals that F5 (flood) and F8 (earthquake) not only have numerous connections but are also linked to other influential risk factors, reinforcing their significance in the network. Additionally, the high betweenness centrality of hydrological factors suggests their role as cascade bridges. When combined with closeness centrality, it can further quantify the propagation speed and identify systemic risk hotspots. This omission highlights the static limitations of the current analysis but paves the way for the integration of a multi-hazard framework.

Figure 12.

Eigenvector centrality ordering.

5. Discussion

This study synthesizes findings from prior research, identifying a comprehensive set of 48 natural disaster risk factors across five categories, providing a valuable resource for future researchers to assess the completeness of their risk assessment frameworks. Literature reviews that establish guidelines are a well-established practice in construction research. Such studies, both theoretically and practically, significantly contribute to the knowledge system by consolidating past work and laying a robust foundation for advancing research [78].

Through the literature review, this study identifies the following key findings and recommendations. These findings are directly derived from the SNA outputs (such as degree centrality, betweenness centrality, and eigenvector centrality) and bridge the gap between theoretical discussions (Network M) and predictive models (Network S), as illustrated in Figure 5 and Figure 7. To enhance practical applicability, these findings have been translated into specific, actionable guidance, focusing on how SNA results can inform resource allocation and emergency planning.

- 1

- Both F5 (flood) and F8 (earthquake) consistently rank highly in degree centrality, betweenness centrality, and eigenvector centrality, as well as in simplified analyses, reflecting their frequent discussion in theoretical and predictive models and their strong interconnections with other natural disaster risk factors. Previous studies have prioritized high-impact risks like F5 (flood) and F8 (earthquake), often neglecting other significant but less frequently studied risks, such as F12 (rockfalls), F23 (land subsidence), and F21 (ice jams).

- 2

- Researchers are encouraged to incorporate critical natural disaster risk factors, such as F5 (flood), F8 (earthquake), F1 (hurricane), F2 (wind), and F26 (tornado), into their predictive models, as these consistently rank among the top 10 in degree centrality, betweenness centrality, and eigenvector centrality.

- 3

- Future research should prioritize under-explored factors like F12 (rockfall), F21 (ice jam), and F23 (land subsidence), which were identified as isolated nodes in the SNA co-occurrence diagrams. This isolation indicates limited connections to other risk factors, potentially leading to their exclusion from predictive models and reducing model comprehensiveness. The project budget can be weighted according to centrality. For example, 40% of the total risk budget could be allocated to high-impact core nodes (such as F5 and F8, for deploying real-time monitoring sensors), while only 10% is allocated to low-connectivity nodes like F12 (rockfalls). By integrating the SNA map with GIS, resources can be prioritized to strengthen mountain slope stabilization, thereby optimizing resource utilization.

- 4

- While many studies emphasize the need to explore diverse risk factors and their interrelationships, existing models predominantly focus on high-impact risks, overlooking others. The matrix in Figure 5 reveals that Network M exhibits stronger and denser connectivity than Network S, indicating greater interconnectivity among risk factors in theoretical discussions compared to predictive models. This gap suggests the need to develop a hierarchical response model: primary responses target core nodes, secondary responses address bridging nodes (e.g., F1, hurricane), and tertiary responses simulate cascading scenarios. For instance, in hurricane-prone areas, integrating threshold-based alert systems with drone inspections can reduce response time.

- 5

- Earthquake risks (F8) warrant particular attention in future research, as both simplified analysis and SNA highlight their frequency and significance in engineering projects [79]. However, a notable gap exists between theoretical discussions and applied models for F8 (earthquake), as evidenced by differences between matrices M and S in Figure 7.

- 6

- Factors such as F36 (hydrological hazards), F19 (extreme temperature), F10 (lightning storms), F25 (temperature variation), F41 (climate change), F42 (the melting of ice), F43 (high altitude), F13 (fault displacement), F15 (spalling), F16 (high geothermal activity), F48 (environmental corrosion), and F29 (geological hazards) are marginalized in the network. This neglect stems from the literature’s single-hazard focus and data scarcity, leading engineering assessments to bias toward high-frequency events. Future research should focus on risk factors that appear frequently in theoretical discussions but have not been incorporated into predictive models. This blind spot skews resources toward core hazards, amplifying cascading losses; project managers may overlook design buffers, increasing the risk of delays.

- 7

- To enhance the prediction and mitigation of natural disaster impacts in engineering projects, future models—such as risk assessment frameworks, simulation tools, or predictive analytics systems—should selectively incorporate relevant subsets of the 48 risk factors identified in this study, tailored to the specific context of the project (e.g., regional hazard characteristics or project phases). Although developing a fully integrated model encompassing all factors may be challenging due to computational complexity and data requirements, creating modular or hierarchical models that allow these factors to be incorporated incrementally and in a scalable manner offers a more practical path toward comprehensive risk management. This approach can address the fragmentation observed in the current literature and support the implementation of adaptive risk management strategies across diverse engineering contexts.

The depth of this study lies in bridging known and unknown information: while confirming core factors, SNA quantifies the systemic role of overlooked factors, laying the foundation for a missing integrated model. In conclusion, this study aligns with existing scholarship and underscores the critical need for a comprehensive model to predict natural disaster risks in engineering projects, addressing a widely recognized gap in the literature. Furthermore, through the analysis of 81 articles and the comparison of SNA centrality results, we found that the failure of prediction models to incorporate risk factors widely discussed in the theoretical literature is primarily due to the mutually reinforcing effects of model complexity and disciplinary silos. Traditional methods (such as BP neural networks [15] and linear regression [19]) encounter the curse of dimensionality when expanded, leading to reduced accuracy, which makes engineering practice favor simpler models. Meanwhile, theoretical discussions are dominated by geology and climatology scholars, while civil engineering models tend to overlook cross-domain impacts. Due to budget or time constraints, these models prioritize “engineering-friendly” factors, creating a feedback loop.

Therefore, a modular prediction model is constructed based on 48 natural disaster risk factors to optimize disaster prevention and control strategies. Through a modular framework, geological, climatic, hydrological, topographic, and biological factors are integrated modularly, utilizing SNA centrality metrics (such as degree centrality and betweenness centrality) to prioritize high-influence factors and achieve targeted resource allocation. Here, the event of New York State coastal bridges affected by hurricane storm surges and waves is taken as an example [80], leveraging the interactions between prominent climatic and hydrological factors from the risk list in this study. The modular prediction model can be applied in layers: the climate module prioritizes the assessment of storm path probabilities, combined with SNA bridging path analysis to optimize pier reinforcement, such as elevating the deck clearance to 2–3 m; the hydrological module integrates sea-level rise to design wave-dissipating structures, supplemented by biological factors for corrosion-resistant coatings. This scheme, in case simulations, will reduce the annual damage rate, providing actionable prevention strategies for coastal infrastructure.

6. Conclusions

This study reviews the existing literature on natural disaster risk factors, offering proactive guidance for future research to develop comprehensive and holistic models for assessing these risks in engineering projects. To achieve this, the authors (1) conducted a meta-analysis of prior research, (2) identified and categorized 48 natural disaster risk factors affecting engineering projects, and (3) employed SNA to quantitatively identify overlooked and under-researched factors in natural disaster risk assessments.

The study highlights both strengths and gaps in the current literature, providing a roadmap for areas requiring further investigation. For example, while theoretical discussions frequently address factors such as F36 (hydrological hazards), F19 (extreme temperatures), F10 (lightning storms), F25 (temperature variations), F41 (climate change), F42 (ice melting), F43 (high altitudes), F13 (fault displacement), F15 (spalling), F16 (high geothermal heat), F48 (environmental corrosion), and F29 (geological hazards), these factors are rarely incorporated into predictive risk models. This study underscores the need to prioritize these overlooked risk factors to enhance the understanding of their dynamics and improve risk assessment frameworks. To integrate these factors into predictive models, one can: (1) extend the framework to a dynamic Bayesian network, incorporating time-series data to simulate cascading probabilities; and (2) develop a hybrid framework that treats low-centrality factors as sensitivity parameters to enhance model robustness. This approach bridges the gap between theory and practice and advances an integrated resilience framework.

The recommendations proposed in this research advocate for a proactive approach to addressing complex natural disaster risks in engineering projects. Researchers are encouraged to focus on bridging the identified research gaps, particularly by integrating under-explored risk factors into predictive models to ensure more comprehensive risk management strategies.

However, this study has certain limitations. The literature search was restricted to articles from the Web of Science, Scopus, and ScienceDirect databases and included only English-language publications, potentially excluding valuable contributions from other databases or languages. Future research should broaden the scope by including additional databases and non-English sources to capture a wider range of risk factors, thereby enhancing the comprehensiveness of the analysis. In addition, the literature analysis in this study was limited to the selected search period, which may have overlooked emerging risk factors driven by recent extreme climate events. With the rapid development of natural disaster research, future findings may need to be validated and extended through regular updates of literature databases to ensure the timeliness and comprehensiveness of the framework. This approach would not only capture emerging interaction effects but also integrate real-time data sources, such as satellite monitoring, further enhancing the predictive accuracy of the models. Therefore, future work should extend to dynamic SNA metrics, such as closeness centrality or PageRank, to capture the dynamics of disaster propagation, and combine them with simulation tools to quantify cascading probabilities. Adopting this expanded approach will improve the management of engineering projects and enable relevant authorities to implement more effective disaster prevention measures.

By synthesizing findings from prior studies, this research establishes a robust foundation for studying natural disaster risk factors in engineering projects, significantly contributing to the knowledge system. The results inform researchers about the current state of the field and highlight areas requiring further exploration, with the ultimate goal of minimizing the impacts of natural disasters on engineering projects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.G. and J.W.; methodology, Q.G. and J.W.; validation, Q.G. and J.W.; formal analysis, Q.G. and J.W.; data curation, Q.G. and J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.G.; writing—review and editing, J.W.; visualization, Q.G. and J.W.; supervision, J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Shandong Province Natural Science Foundation, grant number ZR2023QG168.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

The complete list of all 283 articles is provided here.

Table A1.

The complete list of all 283 articles.

Table A1.

The complete list of all 283 articles.

| Index | Title | Year |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | AI-based risk assessment for construction site disaster preparedness through deep learning-based digital twinning | 2022 |

| 2 | Prioritizing Post-Disaster Reconstruction Projects Using an Integrated Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Approach: A Case Study | 2022 |

| 3 | Assessing the Risk of Natural Disaster-Induced Losses to Tunnel-Construction Projects Using Empirical Financial-Loss Data from South Korea | 2020 |

| 4 | Dynamic risk evaluation method for collapse disasters of drill-and-blast tunnels: a case study | 2022 |

| 5 | Risk-Informed Prediction of Dredging Project Duration Using Stochastic Machine Learning | 2020 |

| 6 | Geological Disaster Susceptibility Evaluation Using Machine Learning: A Case Study of the Atal Tunnel in Tibetan Plateau | 2024 |

| 7 | Exploring Cost Variability and Risk Management Optimization in Natural Disaster Prevention Projects | 2024 |

| 8 | Quantifying the Third-Party Loss in Building Construction Sites Utilizing Claims Payouts: A Case Study in South Korea | 2020 |

| 9 | Natural Assurance Schemes Canvas: A Framework to Develop Business Models for Nature-Based Solutions Aimed at Disaster Risk Reduction | 2021 |

| 10 | A Comprehensive Assessment Approach for Water-Soil Environmental Risk during Railway Construction in Ecological Fragile Region Based on AHP and MEA | 2020 |

| 11 | Risk Assessment of Rockfall Hazards in a Tunnel Portal Section Based on Normal Cloud Model | 2017 |

| 12 | Development of a Road Geohazard Risk Management Framework for Mainstreaming Disaster Risk Reduction in Developing Countries | 2021 |

| 13 | Scientific challenges in disaster risk reduction for the Sichuan-Tibet Railway | 2022 |

| 14 | Dynamic Evaluation Method of the EW-AHP Attribute Identification Model for the Tunnel Gushing Water Disaster under Interval Conditions and Applications | 2021 |

| 15 | Classification of Construction Hazards for a Universal Hazard Identification Methodology | 2020 |

| 16 | Combined System of Magnetic Resonance Sounding and Time-Domain Electromagnetic Method for Water-Induced Disaster Detection in Tunnels | 2018 |

| 17 | Effective Evaluation of Infiltration and Storage Measures in Sponge City Construction: A Case Study of Fenghuang City | 2018 |

| 18 | The cost of rapid and haphazard urbanization: lessons learned from the Freetown landslide disaster | 2019 |

| 19 | BIM-based Hazard Recognition and Evaluation Methodology for Automating Construction Site Risk Assessment | 2020 |

| 20 | Social Vulnerability Evaluation of Natural Disasters and Its Spatiotemporal Evolution in Zhejiang Province, China | 2023 |

| 21 | Implications of building code enforcement and urban expansion on future earthquake loss in East Africa: case study-Blantyre, Malawi | 2023 |

| 22 | Workflows for Construction of Spatio-Temporal Probabilistic Maps for Volcanic Hazard Assessment | 2022 |

| 23 | Quantifying Hazard Exposure Using Real-Time Location Data of Construction Workforce and Equipment | 2016 |

| 24 | Risk assessment of debris flow disaster in mountainous area of northern Yunnan province based on FLO-2D under the influence of extreme rainfall | 2023 |

| 25 | Grain Risk Analysis of Meteorological Disasters in Gansu Province Using Probability Statistics and Index Approaches | 2023 |

| 26 | Dynamic Assessment of Drought Risk of Sugarcane in Guangxi, China Using Coupled Multi-Source Data | 2023 |

| 27 | Personality Assessment Based on Electroencephalography Signals during Hazard Recognition | 2023 |

| 28 | Hierarchical Structure Model of Safety Risk Factors in New Coastal Towns: A Systematic Analysis Using the DEMATEL-ISM-SNA Method | 2022 |

| 29 | Hazard function deployment: a QFD-based tool for the assessment of working tasks—a practical study in the construction industry | 2020 |

| 30 | Hazard Assessment for Biomass Gasification Station Using General Set Pair Analysis | 2016 |

| 31 | Integrating expert opinion with modelling for quantitative multi-hazard risk assessment in the Eastern Italian Alps | 2016 |

| 32 | Quantitative hazard assessment of rockfall and optimization strategy for protection systems of the Huashiya cliff, southwest China | 2020 |

| 33 | UAV Application for Typhoon Damage Assessment in Construction Sites | 2022 |

| 34 | Reliability and Robustness Assessment of Highway Networks under Multi-Hazard Scenarios: A Case Study in Xinjiang, China | 2023 |

| 35 | Probabilistic volcanic mass flow hazard assessment using statistical surrogates of deterministic simulations | 2023 |

| 36 | A Periodic Assessment System for Urban Safety and Security Considering Multiple Hazards Based on WebGIS | 2021 |

| 37 | A Building Classification System for Multi-hazard Risk Assessment | 2022 |

| 38 | Evaluating the impact of mental fatigue on construction equipment operators’ ability to detect hazards using wearable eye-tracking technology | 2019 |

| 39 | A quantitative risk assessment development using risk indicators for predicting economic damages in construction sites of South Korea | 2019 |

| 40 | Validating ambulatory gait assessment technique for hazard sensing in construction environments | 2019 |

| 41 | Health Risk and Resilience Assessment with Respect to the Main Air Pollutants in Sichuan | 2019 |

| 42 | Evaluation of Thermal Hazard Properties of Low Temperature Active Azo Compound under Process Conditions for Polymer Resin in Construction Industries | 2021 |

| 43 | Controlling safety and health challenges intrinsic in exoskeleton use in construction | 2023 |

| 44 | Frazil ice jam risk assessment method for water transfer projects based on design scheme | 2020 |

| 45 | Scenario-based earthquake risk assessment for central-southern Malawi: The case of the Bilila-Mtakataka Fault | 2022 |

| 46 | Hazard Assessment of Rainfall-Induced Landslide Considering the Synergistic Effect of Natural Factors and Human Activities | 2023 |

| 47 | Multifactor Uncertainty Analysis of Construction Risk for Deep Foundation Pits | 2022 |

| 48 | Hazard and risk assessment for early phase road planning in Norway | 2023 |

| 49 | Quantifying workers’ gait patterns to identify safety hazards in construction using a wearable insole pressure system | 2020 |

| 50 | Perceptions of disaster temporalities in two Indigenous societies from the Southwest Pacific | 2021 |

| 51 | Automated performance assessment of prevention through design and planning (PtD/P) strategies in construction | 2024 |

| 52 | Selection of Policies on Typhoon and Rainstorm Disasters in China: A Content Analysis Perspective | 2018 |

| 53 | Exploring construction workers’ attention and awareness in diverse virtual hazard scenarios to prevent struck-by accidents | 2024 |

| 54 | Comprehensive assessment of geological hazard safety along railway engineering using a novel method: a case study of the Sichuan-Tibet railway, China | 2020 |

| 55 | Quantitative Assessment of the State of Threat of Working on Construction Scaffolding | 2020 |

| 56 | Integration of InSAR and LiDAR Technologies for a Detailed Urban Subsidence and Hazard Assessment in Shenzhen, China | 2021 |

| 57 | Influence of Sociodemographic Factors on Construction Fieldworkers’ Safety Risk Assessments | 2022 |

| 58 | Assessment of Health and Safety Solutions at a Construction Site | 2013 |

| 59 | Risk Assessment of Offshore Wind Turbines Suction Bucket Foundation Subject to Multi-Hazard Events | 2023 |

| 60 | Risk Analysis and Extension Assessment for the Stability of Surrounding Rock in Deep Coal Roadway | 2019 |

| 61 | Risk Assessment and Control of Geological Hazards in Towns of Complex Mountainous Areas Based on Remote Sensing and Geological Survey | 2023 |

| 62 | The 2013 European Seismic Hazard Model: key components and results | 2015 |

| 63 | Assessment of seismic hazard in the Erzincan (Turkey) region: construction of local velocity models and evaluation of potential ground motions | 2015 |

| 64 | Mechanism of water inrush in tunnel construction in karst area | 2016 |

| 65 | Safety Performance Assessment of Construction Sites under the Influence of Psychological Factors: An Analysis Based on the Extension Cloud Model | 2022 |

| 66 | An Improved Probabilistic Seismic Hazard Assessment of Tripura, India | 2022 |

| 67 | Probabilistic assessment of landslide tsunami hazard for the northern Gulf of Mexico | 2016 |

| 68 | Multi-Hazard Meteorological Disaster Risk Assessment for Agriculture Based on Historical Disaster Data in Jilin Province, China | 2022 |

| 69 | A Decision Support System for Organizing Quality Control of Buildings Construction during the Rebuilding of Destroyed Cities | 2023 |

| 70 | Hazard Assessment of Debris Flow: A Case Study of the Huiyazi Debris Flow | 2024 |

| 71 | Construction and Application of Safety Management Scenarios at Construction Sites | 2024 |

| 72 | Validity and reliability of a wearable insole pressure system for measuring gait parameters to identify safety hazards in construction | 2021 |

| 73 | Governing the Moral Hazard in China’s Sponge City Projects: A Managerial Analysis of the Construction in the Non-Public Land | 2018 |

| 74 | Practice Framework for the Management of Post-Disaster Housing Reconstruction Programmes | 2018 |

| 75 | A spatiotemporal multi-hazard exposure assessment based on property data | 2015 |

| 76 | Use of Mamdani Fuzzy Algorithm for Multi-Hazard Susceptibility Assessment in a Developing Urban Settlement (Mamak, Ankara, Turkey) | 2020 |

| 77 | Occupational Risk Index for Assessment of Risk in Construction Work by Activity | 2014 |

| 78 | Stability of spatial dependence structure of extreme precipitation and the concurrent risk over a nested basin | 2021 |

| 79 | Assessment of check dams’ role in flood hazard mapping in a semi-arid environment | 2019 |

| 80 | An Extension of the Failure Mode and Effect Analysis with Hesitant Fuzzy Sets to Assess the Occupational Hazards in the Construction Industry | 2020 |

| 81 | Hazard Zonation and Risk Assessment of a Debris Flow under Different Rainfall Condition in Wudu District, Gansu Province, Northwest China | 2022 |

| 82 | Developing a BIM and Simulation-Based Hazard Assessment and Visualization Framework for CLT Construction Design | 2021 |

| 83 | Risk Assessment for Hazard Exposure and Its Consequences on Housing Construction Sites in Lagos, Nigeria | 2020 |

| 84 | Enhancing Risk Assessment in Toll Road Operations: A Hybrid Rough Delphi-Rough DEMATEL Approach | 2023 |

| 85 | Risk-Informed Performance-Based Metrics for Evaluating the Structural Safety and Serviceability of Constructed Assets against Natural Disasters | 2021 |

| 86 | Dynamic Simulation of the Probable Propagation of a Disaster in an Engineering System Using a Scenario-Based Hybrid Network Model | 2022 |

| 87 | Predicting the resilience of transport infrastructure to a natural disaster using Cox’s proportional hazards regression model | 2017 |

| 88 | Disaster Risk Management Through the DesignSafe Cyberinfrastructure | 2020 |

| 89 | Role of Predisaster Construction Market Conditions in Influencing Postdisaster Demand Surge | 2018 |

| 90 | Historic storms and the hidden value of coastal wetlands for nature-based flood defence | 2020 |

| 91 | A Decision Process for Optimizing Multi-Hazard Shelter Location Using Global Data | 2020 |

| 92 | Study on the evolutionary mechanisms driving deformation damage of dry tailing stack earth-rock dam under short-term extreme rainfall conditions | 2023 |

| 93 | Essential Tools to Mitigate Vrancea Strong Earthquakes Effects on Moldavian Urban Environment | 2013 |

| 94 | Market-Implied Spread for Earthquake CAT Bonds: Financial Implications of Engineering Decisions | 2010 |

| 95 | Assessment of Damage Risks to Residential Buildings and Cost-Benefit of Mitigation Strategies Considering Hurricane and Earthquake Hazards | 2012 |

| 96 | Influence of rupture velocity on risk assessment of concrete moment frames: Supershear vs. subshear ruptures | 2024 |

| 97 | Loss Analysis for Combined Wind and Surge in Hurricanes | 2012 |

| 98 | Market Insurance and Self-Insurance through Retrofit: Analysis of Hurricane Risk in North Carolina | 2017 |

| 99 | Landslide susceptibility assessment using weights-of-evidence model and cluster analysis along the highways in the Hubei section of the Three Gorges Reservoir Area | 2021 |

| 100 | Ethical discounting for civil infrastructure decisions extending over multiple generations | 2015 |

| 101 | Discrete-Outcome Analysis of Tornado Damage Following the 2011 Tuscaloosa, Alabama, Tornado | 2020 |

| 102 | Framework for Earthquake Risk Assessment for Container Ports | 2010 |

| 103 | Research on real-time risk monitoring model along the water transfer project: a case study in China | 2022 |

| 104 | Failure analysis of the offshore process component considering causation dependence | 2018 |

| 105 | Risk-Based Design of Dike Elevation Employing Alternative Enumeration | 2014 |

| 106 | Seismic damage to pipelines in the framework of Na-Tech risk assessment | 2015 |

| 107 | Numerical and Physical Analysis on the Response of a Dam’s Radial Gate to Extreme Loading Performance | 2020 |

| 108 | Flood susceptibility-based building risk under climate change, Hyderabad, India | 2023 |

| 109 | Machine learning network suitable for accurate rapid seismic risk estimation of masonry building stocks | 2023 |

| 110 | Dynamical process of the Hongshiyan landslide induced by the 2014 Ludian earthquake and stability evaluation of the back scarp of the remnant slope | 2019 |

| 111 | Probabilistic Flood Loss Assessment at the Community Scale: Case Study of 2016 Flooding in Lumberton, North Carolina | 2020 |

| 112 | Fragility assessment of traditional wooden houses in Madagascar subjected to extreme wind loads | 2023 |

| 113 | Insurance Pricing for Windstorm-Susceptible Developments: Bootstrapping Approach | 2012 |

| 114 | Flood characterization based on forensic analysis of bridge collapse using UAV reconnaissance and CFD simulations | 2022 |

| 115 | A Comparative Study of a Typical Glacial Lake in the Himalayas before and after Engineering Management | 2023 |

| 116 | An Integrated GIS-BBN Approach to Quantify Resilience of Roadways Network Infrastructure System against Flood Hazard | 2020 |

| 117 | Early warning method for overseas natural gas pipeline accidents based on FDOOBN under severe environmental conditions | 2022 |

| 118 | Framework for Multihazard Risk Assessment and Mitigation for Wood-Frame Residential Construction | 2009 |

| 119 | Attributes and metrics for comparative quantification of disaster resilience across diverse performance mandates and standards of building | 2019 |

| 120 | Risk Assessment of Shield Tunnel Construction in Karst Strata Based on Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process and Cloud Model | 2021 |

| 121 | Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation of Collapse Risk in Mountain Tunnels Based on Game Theory | 2024 |

| 122 | The Practice of Forward Prospecting of Adverse Geology Applied to Hard Rock TBM Tunnel Construction: The Case of the Songhua River Water Conveyance Project in the Middle of Jilin Province | 2018 |

| 123 | Evolution Law and Grouting Treatment of Water Inrush in Hydraulic Tunnel Approaching Water-Rich Fault: A Case Study | 2024 |

| 124 | Dynamic Stability Analysis of Subsea Tunnel Crossing Active Fault Zone: A Case Study | 2024 |

| 125 | Flooded architecture as an adaptation tool for climate change impact-a case study of possible interpretation in Egypt | 2024 |

| 126 | Quantitative foundation stability evaluation of urban karst area: Case study of Tangshan, China | 2015 |

| 127 | Processes and techniques for rapid bridge replacement after extreme events | 2007 |

| 128 | Construction stability analysis of intersection tunnel in city under CRD method | 2023 |

| 129 | Public School Earthquake Safety Program in Nepal | 2014 |

| 130 | Research on the Resilience Evaluation of Rural Ecological Landscapes in the Context of Desertification Prevention and Control: a Case Study of Yueyaquan Village in Gansu Province | 2024 |

| 131 | The Post-disaster House: Simple Instant House using Lightweight Steel Structure, Bracing, and Local Wood Wall | 2021 |

| 132 | Research on the Classification of Life-Cycle Safety Monitoring Levels of Subsea Tunnels | 2017 |

| 133 | Increasing vulnerability to floods in new development areas: evidence from Ho Chi Minh City | 2018 |

| 134 | Assessing the risk of natural disaster-induced losses to tunnel-construction projects using empirical financial-loss data from South Korea | 2020 |

| 135 | The centrality of engineering codes and risk-based design standards in climate adaptation strategies | 2021 |

| 136 | Fearing the knock on the door: Critical security studies insights into limited cooperation with disaster management regimes | 2015 |

| 137 | Risk assessment and management of vulnerable areas to flash flood hazards in arid regions using remote sensing and GIS-based knowledge-driven techniques | 2023 |