1. Introduction

High-density polyethylene (HDPE) modification of bitumen has emerged as a promising avenue for enhancing the high-temperature performance of asphalt pavements. From a physicochemical perspective, the addition of HDPE to bitumen leverages intermolecular interactions to achieve a more robust and heat-resistant binder [

1]. The modification of asphalt binder with a ternary compound inhibitor significantly mitigates fume emissions during production while maintaining or even enhancing its rheological performance, thereby ensuring improved pavement safety and durability [

2]. Abdy et al. [

3] state that the long, linear chains of HDPE, characterized by their high degree of crystallinity, physically entangle with the complex hydrocarbon matrix of bitumen [

3]. This entanglement restricts the movement of bitumen molecules at elevated temperatures, increasing the binder’s viscosity and resistance to permanent deformation [

4]. Furthermore, Nizamuddin et al. [

5] suggest that the non-polar nature of HDPE promotes favorable interactions with the asphaltene fraction of bitumen, leading to improved dispersion and stability of the modified binder [

5]. The resulting blend exhibits a higher softening point, reduced temperature susceptibility, and enhanced elastic recovery, all of which contribute to improved rutting resistance in asphalt mixtures [

6]. A comprehensive investigation into the molecular characteristics of HDPE reveals that its high molecular weight and narrow molecular weight distribution are crucial factors governing its effectiveness as a bitumen modifier [

7]. The high molecular weight ensures a substantial increase in the overall viscosity of the blend, while the narrow distribution promotes uniform dispersion and minimizes phase separation, leading to a more homogeneous and stable modified bitumen with superior high-temperature rheological and mechanical properties suitable for demanding pavement applications [

8].

According to Yang et al. [

9], the rheological properties of bitumen, including viscosity, elasticity, and temperature susceptibility, directly influence the structural performance and efficiency of pavements [

9]. Saleh and Hashemian [

10] highlight that precise characterization of materials, especially bitumen, is of paramount importance as a key factor in designing durable and resilient pavements [

10]. Wang et al. [

11] note that if the pavement materials cannot provide sufficient resistance against fatigue, permanent deformation (rutting), and thermal cracking, serious damage appears in asphalt pavements that severely disrupts their structural performance and functionality [

11]. Also indicated that pavement failure occurs when its performance deteriorates to the extent that it can no longer fulfill its primary function or provide an adequate level of service, and in flexible pavements, three major types of damage lead to structural failure: rutting, fatigue cracking, and thermal cracking. In flexible pavements, structural failure occurs when rutting, fatigue cracking, or thermal cracking compromises performance to the point of being unable to safely support intended loads like aircraft [

12].

To overcome the limitations of pure bitumen and improve its resistance to the aforementioned damages, researchers have focused extensive efforts over the past four decades on modifying bitumen by adding various polymers [

13]. These modifiers are used to enhance the physical and rheological properties of bitumen, particularly to improve performance at high temperatures (resistance to rutting) and at low temperatures (resistance to cracking). For developing countries, using recycled plastics as additives in bituminous materials is not only a cost-effective solution to reinforce bitumen but also an effective step toward mitigating the environmental hazards caused by the accumulation of this waste [

11,

14]. Investigating the high-and low-temperature performance of warm crumb rubber–modified bituminous binders using rheological tests. Environmental Protection Agency statistics show that a significant volume of plastic waste is improperly managed in these countries [

15]. This alarming statistic further highlights the necessity of finding effective applications for recycled plastics, such as bitumen modification. Bitumen modified with recycled plastics mainly functions through elastomeric or plastomeric polymers [

16]. Adding these polymers (typically between 2% and 6% by weight of bitumen) can significantly impact the rheological properties and viscosity function of bitumen [

17]. The process of mixing bitumen with polymers before adding it to aggregate is known as the wet method. According to Almusawi et al. research has shown that, depending on the type, size, and shape of the polymer, and the equipment used for mixing, adding recycled plastics can lead to improvements in several key properties, including: resistance to permanent deformation (rutting), resistance to moisture damage (stripping), increased fatigue life, and achieving higher stiffness at high temperatures [

18]. Among these, polyethylenes, especially high-density polyethylene (HDPE) and low-density polyethylene (LDPE), have high potential for producing asphalt mixtures with superior mechanical performance and enabling the design of thinner and more optimized pavement sections due to their high mechanical strength and relatively good chemical compatibility with base bitumen. Recent studies have further elucidated the critical role of nano-scale structural formations in governing bitumen performance. For instance, Hu et al. [

19] demonstrated that the nano-aggregation of asphaltenes during aging significantly influences the multiscale properties of bitumen, and that rejuvenation can effectively disaggregate these clusters, partially restoring the microstructure. This underscores the importance of understanding and controlling the formation of reinforcing networks at the nanoscale. In a parallel approach, the current study utilizes recycled HDPE to create a continuous polymer network within the bitumen matrix. While the mechanism differs—physical polymer entanglement versus asphaltene aggregation—both strategies aim to enhance the material’s rheological and mechanical properties by manipulating its internal microstructure. The findings of Hu et al. reinforce the broader principle that targeted modification of bitumen’s nanostructure is a powerful tool for performance enhancement, a principle that this work applies through polymer modification to achieve superior high-temperature stability and rutting resistance [

19].

The use of HDPE-modified bitumen leads to enhanced pavement performance in high-temperature environments by increasing the softening point and viscosity of the binder, as well as improving the elastic recovery and resistance to permanent deformation of asphalt mixtures. The application of HDPE in bitumen has been widely investigated, demonstrating significant improvements in high-temperature performance [

1,

2]. Recent studies by Piromanski et al. [

20] and Nizamuddin et al. [

5] have specifically explored HDPE-bitumen interactions, while Piromanski et al. [

21] quantified its rutting resistance enhancement. However, research on optimizing recycled HDPE dosage (2–9%) for tropical conditions remains limited, presenting a critical research gap that this study addresses.

The use of HDPE-modified bitumen leads to enhanced pavement performance in high-temperature environments by increasing the softening point and viscosity of the binder, as well as improving the elastic recovery and resistance to permanent deformation of asphalt mixtures. These performance enhancements are fundamentally governed by the key molecular characteristics of HDPE, namely its high molecular weight and narrow molecular weight distribution, as introduced earlier [

7,

8]. Zhang et al. reported that the high molecular weight ensures a substantial increase in the overall viscosity of the blend, while the narrow distribution promotes uniform dispersion and minimizes phase separation, leading to a more homogeneous and stable modified bitumen with superior high-temperature rheological and mechanical properties suitable for demanding pavement applications [

22].

A fundamental and widely accepted method to quantify the stiffening effect of a polymer modifier like HDPE on bitumen is by calculating the Stiffness Ratio [

23]. This parameter is defined as the ratio of the complex shear modulus of the modified bitumen to that of the base bitumen, measured at the same temperature and frequency:

where

Gmodified, is the complex shear modulus of the HDPE-modified bitumen (Pa).

Gbase, is the complex shear modulus of the base bitumen (Pa).

A Stiffness Ratio greater than 1 indicates an improvement in the material’s resistance to deformation. This simple ratio effectively normalizes the enhancement and allows for direct comparison between different modifiers and concentrations.

This study addresses the critical need to enhance asphalt pavement durability in high-temperature regions through systematic investigation of HDPE-modified bitumen. Despite established benefits of polymer modification, a significant knowledge gap persists regarding the high-temperature rheological-mechanical synergy of recycled HDPE-bitumen blends, particularly under dynamic loading and long-term aging conditions. The primary objectives are to: (1) Quantify the impact of recycled HDPE (2–6% wt.) on high-temperature viscosity, rutting resistance (G*/sinδ), and elastic recovery of bitumen using dynamic shear rheometry (DSR) and rotational viscometer; (2) Evaluate mechanical performance of HDPE-modified asphalt mixtures via Marshall Stability and Marshall Quotient (3) Characterize morphological compatibility and phase dispersion through scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Recycled HDPE flakes (<2 mm) were blended with PG 64-22 bitumen via high-shear mixing (160 °C, 4000 rpm, 60 min). Rheological properties were characterized using DSR (AASHTO T315), while mixture performance was evaluated via Marshall Stability (ASTM D6927) [

24]. SEM analysis probed HDPE-bitumen interactions, correlating microstructure with workability and in-service performance to optimize sustainable binders for tropical climates. It is crucial to emphasize that HDPE, as a plastomer, is inherently poorly compatible with the bituminous matrix. This incompatibility arises from HDPE’s higher rigidity and lower flexibility compared to bitumen, and its inability to dissolve under standard technological conditions. Instead, it typically forms a separate, high-viscosity dispersed phase. This fundamental difference can lead to challenges such as phase separation, sedimentation, and particle agglomeration during storage and application [

5]. To mitigate these issues and enhance the stability of the blend, the use of compatibilizing agents is often necessary in practice. These can include low-molecular-weight elastomers (e.g., EVA, SBS, EBA), polar modifiers, or reactive chemical compatibilizers, which improve the interfacial adhesion and dispersion within the bitumen matrix [

25]. The thermodynamic compatibility between polymer and bitumen can be fundamentally assessed using concepts such as the Hansen solubility parameter [

4], which helps predict miscibility and phase behavior.

3. Results Analysis

3.1. Penetration Test

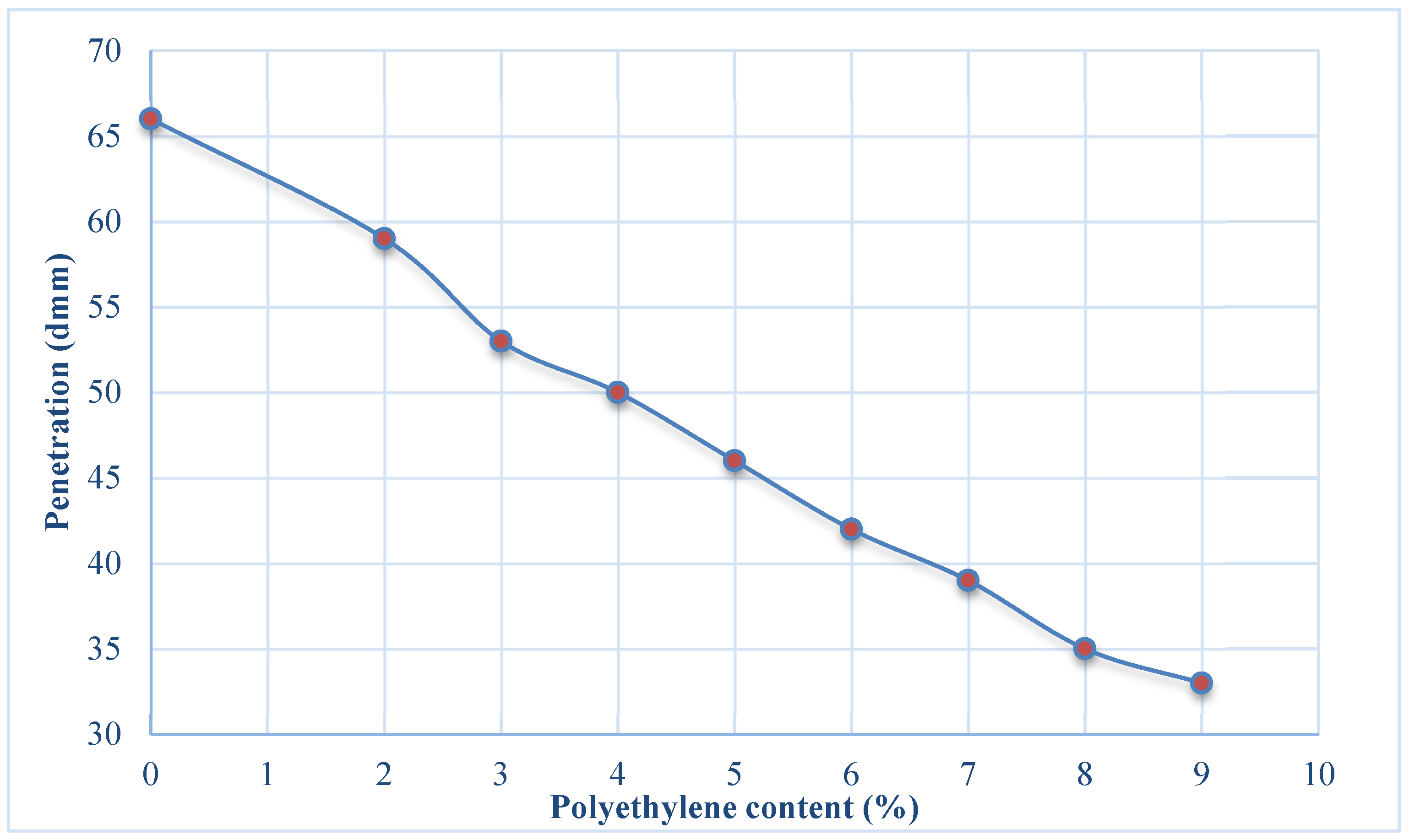

In polymer-modified bitumen, notably with high-density polyethylene (HDPE), the penetration test (ASTM D5) is a key indicator of the polymer’s influence on binder rheology. The data reveal a distinct inverse correlation between HDPE content and penetration depth. As HDPE concentration increases from 0% to 9%, penetration values decrease progressively from 66 to 33 dmm (

Figure 3). This reduction stems from the interaction between the semi-crystalline HDPE polymer and the bitumen matrix. At the microscale, HDPE chains entangle with asphaltenes and other bitumen components, forming a reinforced, interconnected network that restricts molecular movement, thereby increasing resistance to deformation and lowering penetration.

The modification mechanism involves primarily physical interactions, where HDPE particles act as a filler, occupying space and increasing stiffness; the rigid semi-crystalline domains further contribute to this effect. Entanglement also enhances elasticity, improving deformation recovery. Limited chemical interactions with aromatic bitumen components may occur, enhancing compatibility. Reduced penetration signifies improved resistance to rutting under traffic at high temperatures. Furthermore, HDPE modification enhances elastic recovery, crucial for mitigating fatigue cracking induced by traffic and thermal stresses, extending pavement service life.

Figure 3 also demonstrates the corresponding increase in Penetration Index (PI) with rising HDPE content, indicating reduced temperature susceptibility. However, HDPE concentration requires careful optimization. While higher content boosts stiffness and rutting resistance, excessive amounts risk inducing brittleness and low-temperature cracking. Thus, balancing performance characteristics is essential. Comprehensive assessment necessitates supplementary testing, including softening point, viscosity, and ductility.

3.2. Softening Point Test

The softening point test (ASTM D36) determines the temperature at which bitumen transitions from a semi-solid to a softened state, indicating its resistance to deformation at elevated temperatures. This transition depends on intermolecular forces and molecular mobility within the bitumen matrix. Incorporating high-density polyethylene (HDPE), a semi-crystalline polymer with strong van der Waals forces and a high melting point, significantly alters the bitumen’s properties, leading to a marked increase in softening point.

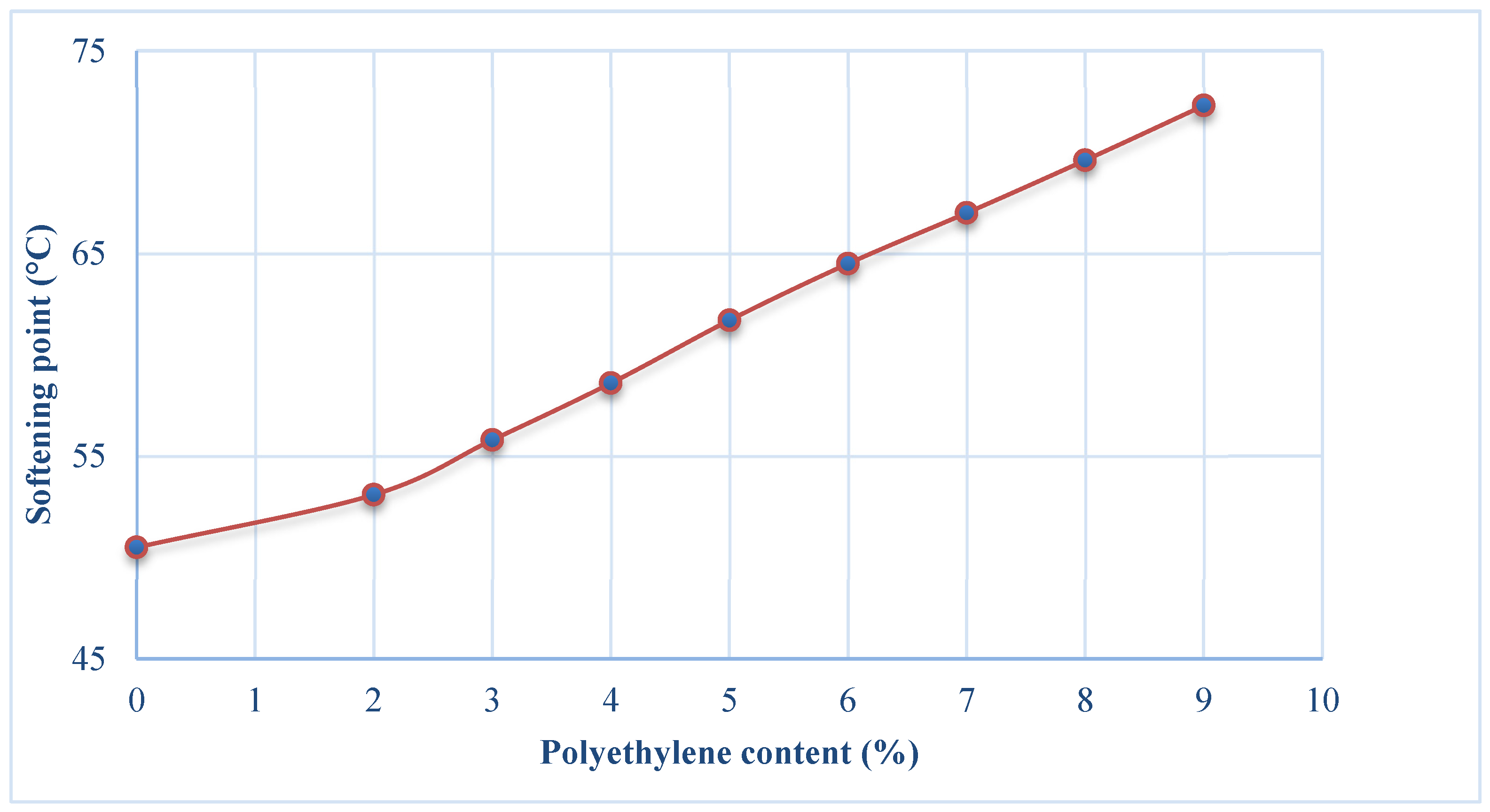

HDPE forms a dispersed phase within the bitumen matrix. The observed increase in softening point with rising HDPE content (

Figure 4) stems from three primary mechanisms: (1) Dispersed HDPE particles physically restrict bitumen molecular movement, acting as crosslinks that hinder flow under thermal stress; (2) Non-polar HDPE molecules interact with saturated bitumen fractions, potentially disrupting natural component associations and affecting cohesive strength; (3) HDPE’s inherent rigidity at high temperatures (due to its high melting point) provides structural support as the bitumen softens. As shown in

Figure 4, increasing HDPE concentration from 0% to 9% systematically elevates the softening point from 50.5 °C to 72.3 °C. This direct correlation underscores the efficacy of HDPE in enhancing high-temperature performance. The increase is fundamentally linked to the HDPE volume fraction, where higher concentrations impose greater restriction on bitumen mobility, thereby requiring more thermal energy to induce softening. The resulting improvement in rutting resistance under high-temperature service conditions; stemming from elevated softening points; confirms findings by Piromanski et al. [

23] that HDPE acts as an effective modifier for boosting bituminous binders’ thermal stability.

3.3. Penetration Index (PI)

The Penetration Index (PI), a dimensionless parameter derived from penetration (ASTM D5) and softening point (ASTM D36) tests, characterizes the temperature susceptibility of asphalt binders. A higher PI indicates lower temperature susceptibility, signifying more consistent rheological behavior across temperature ranges. Incorporating High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE)—a thermoplastic polymer with high strength-to-density ratio and melting point—significantly modifies bitumen properties, thereby increasing its PI.

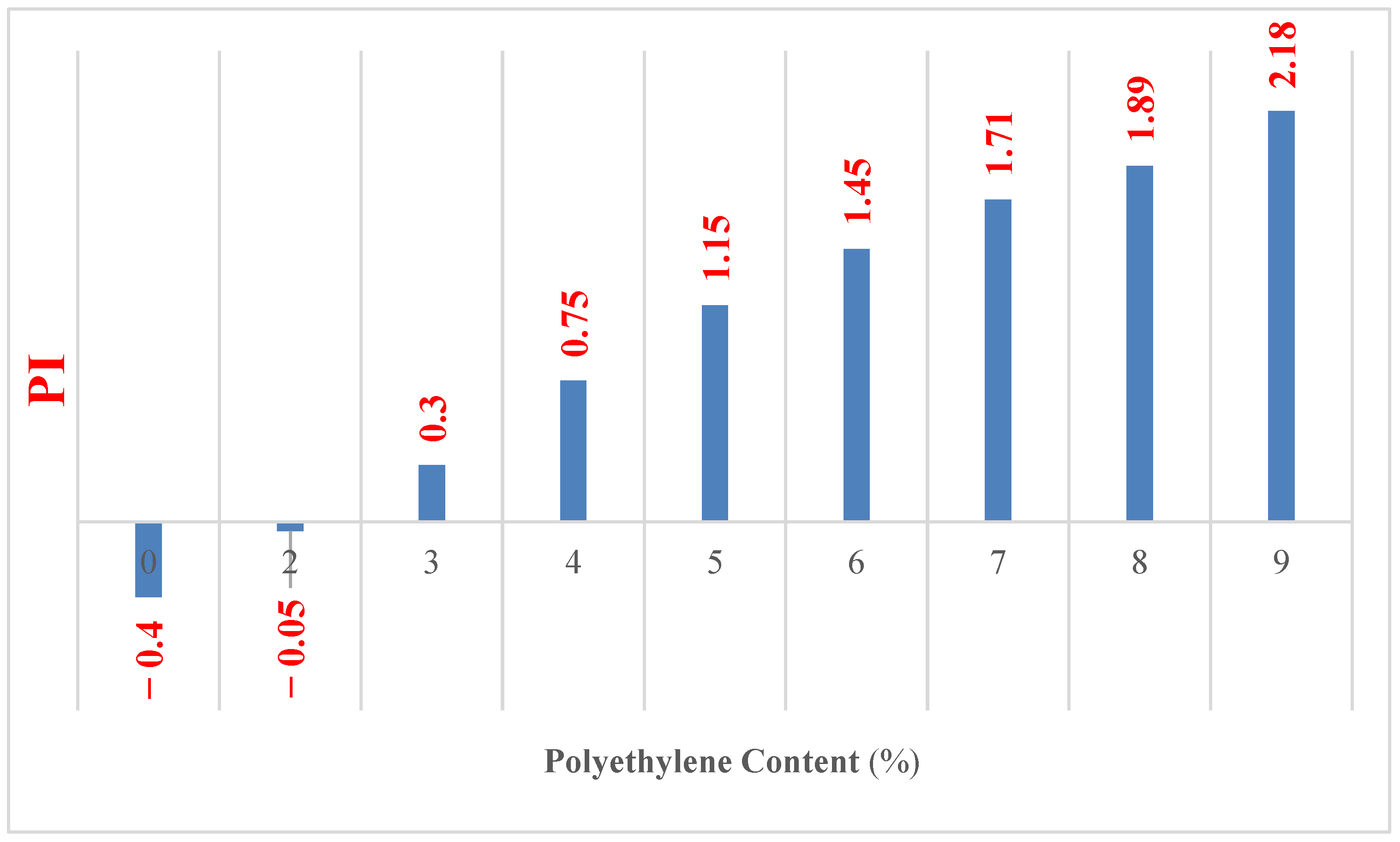

As HDPE content rises, the PI systematically increases (

Figure 5). This positive correlation stems from several key mechanisms: (1) Increased Stiffness: HDPE chains intertwine with bitumen asphaltenes, forming a reinforced, rigid network that reduces penetration (25 °C) by enhancing resistance to deformation. (2) Elevated Softening Point: HDPE’s crystalline structure requires more thermal energy to disrupt intermolecular forces, raising the softening point. The consequent reduction in the difference between softening point and 25 °C directly contributes to a higher PI calculation. (3) Enhanced Cohesion: Primarily physical interactions (e.g., van der Waals forces) between HDPE chains and asphaltenes increase the binder’s viscosity and cohesion, improving resistance to permanent deformation. The data explicitly demonstrates this trend: PI rises from −0.4 (0% HDPE, high susceptibility) to +2.18 (9% HDPE, significantly reduced susceptibility). This substantial increase confirms HDPE’s efficacy in enhancing the binder’s thermal stability the higher PI signifies that HDPE-modified binders, as Tahmoorian et al. [

23] noted, maintain consistent stiffness over wide temperature ranges, translating to improved pavement performance.

3.4. Rheological Characteristics

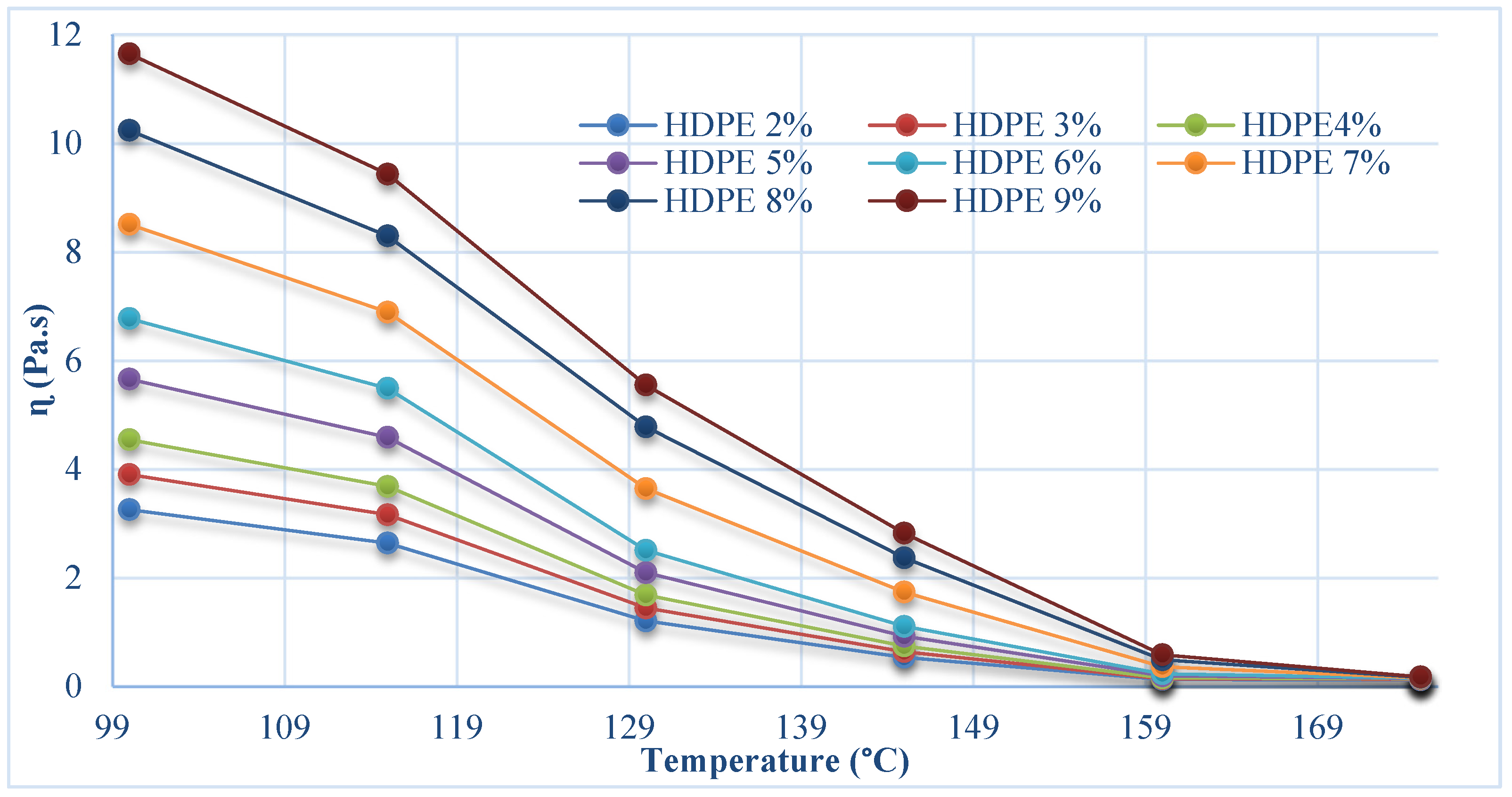

Viscosity measurements (Pa·s), conducted per ASTM D4402, are critical for characterizing the rheological behavior of HDPE-modified bitumen. The data, spanning temperatures from 100 °C to 175 °C and HDPE concentrations from 2% to 9%, reveals the modified binders’ high-temperature performance. Viscosity fundamentally reflects resistance to flow, governed by intermolecular forces and the internal structure dictated by bitumen’s complex composition (asphaltenes, resins, oils, saturates). Introducing HDPE, a semi-crystalline polymer, significantly alters these interactions. HDPE forms a three-dimensional network within the bitumen matrix, physically restricting molecular movement. This is evidenced by the systematic viscosity increase with rising HDPE content at any fixed temperature (

Figure 6). Polymer chain entanglement with bitumen components restricts flow, elevating viscosity. At lower HDPE concentrations (2–4%), the viscosity increase primarily stems from physical entanglement and interaction of HDPE chains with bitumen molecules. Conversely, at higher concentrations (6–9%), HDPE tends to form a more continuous polymer network, leading to a substantially more pronounced viscosity elevation.

Temperature exerts a critical influence on the viscosity of both neat and HDPE-modified bitumen. As temperature escalates from 100 °C to 175 °C, increased molecular kinetic energy weakens intermolecular cohesive forces, markedly reducing viscosity and enhancing fluidity. The data explicitly demonstrates this significant viscosity decrease with rising temperature across all HDPE percentages (2% to 9%). For instance, viscosity values at 100 °C are substantially higher than those measured at 175 °C for every HDPE concentration level. This pronounced temperature dependence follows the Arrhenius relationship, which models the exponential decrease in viscosity with increasing absolute temperature. The activation energy for viscous flow, derived from the Arrhenius equation slope, quantifies the temperature sensitivity. The formation of HDPE networks at higher concentrations (≥6%) modifies the temperature susceptibility compared to the base bitumen or lower HDPE content blends. Understanding this temperature-viscosity profile, modulated by HDPE content, is essential for predicting binder performance during asphalt mixture production (mixing, compaction temperatures) and in-service resistance to rutting deformation at elevated pavement temperatures.

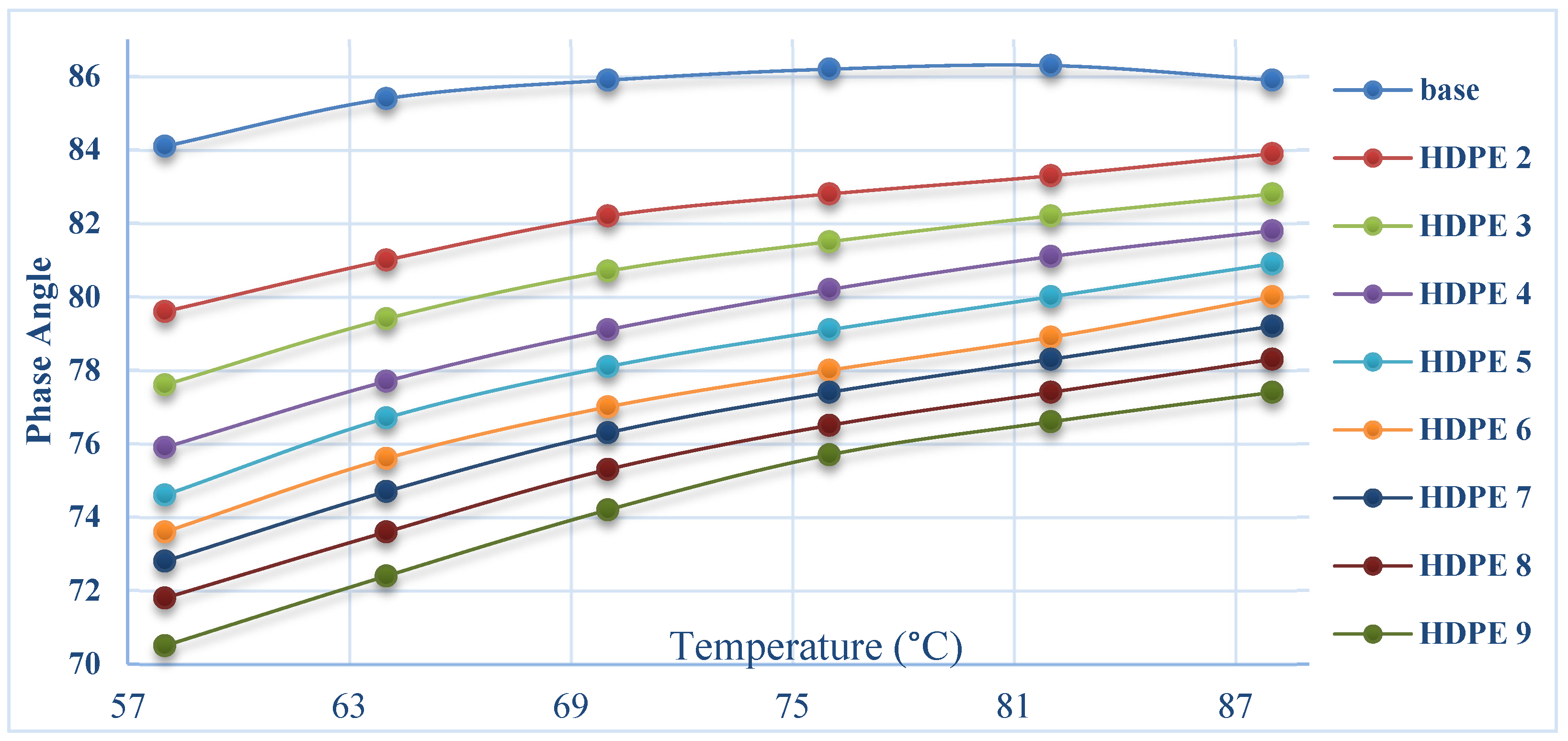

The mechanical properties of HDPE-modified bitumen are intrinsically governed by its rheological characteristics. Increased viscosity, particularly at elevated temperatures, directly correlates with improved resistance to rutting—permanent deformation caused by repeated traffic loading. This viscosity enhancement contributes to a higher complex modulus (|G*|) and a lower phase angle (δ), signifying a shift towards more elastic (solid-like) and less viscous (fluid-like) behavior. Data confirms that rising HDPE content systematically enhances the high-temperature stiffness and elasticity of the bitumen binder. This effect is critical in warm climates and under heavy traffic, where conventional bitumen softens and becomes deformation-prone, potentially leading to significantly improved rutting resistance in asphalt mixtures. The phase angle (δ) is a fundamental parameter characterizing the viscoelastic balance, providing key insights into the impact of HDPE modification. This investigation analyses δ for base bitumen and HDPE-modified bitumen (2% to 9% HDPE) across a high-temperature range (58 °C to 88 °C). As shown in

Figure 7, increasing HDPE content leads to a systematic decrease in phase angle (δ). At lower concentrations (e.g., 2–4%), dispersed HDPE chains act as reinforcing elements, restricting bitumen molecular flow, reducing the viscous component, and thereby lowering δ.

As HDPE content increases (e.g., 6–9%), the polymer forms a more interconnected and rigid network, further enhancing elastic properties and resulting in even lower δ values. HDPE, a thermoplastic, inherently contributes its elastic characteristics to the blend; higher concentrations thus impart greater overall elasticity. Phase angle exhibits strong temperature dependence due to increased molecular mobility at higher temperatures. Rising temperature provides bitumen molecules with greater kinetic energy, facilitating movement, increasing the viscous component (G″) relative to the elastic component (G′), and consequently elevating δ. The presence of HDPE modifies this temperature sensitivity. While HDPE molecules also gain mobility with temperature, their reinforcement effect persists, mitigating the δ increase compared to unmodified bitumen. Interactions between bitumen and HDPE, primarily physical entanglements and weak van der Waals forces rather than chemical reactions, influence compatibility and stability. The formation of a homogeneous and stable HDPE-bitumen blend produces more consistent and predictable phase angle (δ) values, underpinning the enhanced high-temperature performance. This reduction in δ across the tested temperature range, as demonstrated by Piromanski et al., confirms the effectiveness of HDPE in promoting a more elastic response, which is essential for improved rutting resistance [

23].

To provide a more comprehensive rheological characterization as suggested, the complex modulus (G) was analyzed. The results, demonstrate a significant increase in G with HDPE content, corroborating the enhanced stiffness and rutting resistance. For instance, at 64 °C and 6% HDPE, G* reached 15.4 kPa, a marked improvement over the base bitumen’s 3.2 kPa. The significant enhancement in G/sinδ and reduction in phase angle with HDPE addition fundamentally stems from the formation of a continuous, elastic polymer network within the bitumen matrix. This network restricts the mobility of the maltene phase, increasing the material’s overall stiffness (G) and shifting its viscoelastic balance toward a more elastic, solid-like response, as evidenced by the lower δ. The exponential increase in viscosity follows the Arrhenius relationship, with HDPE raising the activation energy for flow. This comprehensive rheological transformation underpins the superior resistance to non-recoverable deformation under high-temperature, high-shear conditions.

3.5. HDPE Asphalt Enhancement Effects

Experimental data demonstrate a clear trend; stability values increase progressively with rising HDPE concentration, reaching a maximum of 19,000 N at 6% HDPE, compared to 13,000 N for the unmodified binder, followed by a subsequent decrease at higher polymer contents. Firstly, the partial dissolution and swelling of semi-crystalline HDPE particles within the bitumen’s maltene fraction (particularly absorbing aromatic and saturate oils) facilitate the formation of a continuous, three-dimensional polymer-rich network phase; this network acts as a reinforcing scaffold, dramatically increasing the composite binder’s stiffness and elastic recovery, thereby enhancing the mixture’s overall rigidity and its ability to distribute stress more effectively under the Marshall test load. Secondly, the modified binder exhibits improved adhesion characteristics at the interface with mineral aggregates; the physical interaction between the swollen HDPE domains and the aggregate surface, potentially involving enhanced wetting and mechanical interlocking due to the increased binder viscosity and elasticity, promotes stronger bonding, reducing the susceptibility to cohesive failure within the binder or adhesive failure at the binder-aggregate interface. As shown in

Figure 8, the observed peak stability at 6% HDPE represents an optimal concentration where the reinforcing polymer network achieves near-maximum continuity and dispersion efficiency within this specific bitumen-aggregate system, maximizing the synergistic effects of binder stiffening and interfacial adhesion enhancement.

However, exceeding this optimal dosage (e.g., 7–9% HDPE) initiates a decline in stability, a phenomenon mechanistically linked to several adverse effects: excessive polymer content can lead to incomplete dispersion, promoting HDPE agglomeration and creating localized regions of inhomogeneity that act as stress concentrators rather than uniform reinforcement; the significantly increased blend viscosity hinders optimal coating of aggregates during mixing and compaction, potentially resulting in reduced film thickness, poorer workability, and compromised aggregate packing density, thereby creating weaker zones within the compacted mixture; the modified binder may become excessively rigid and brittle at high HDPE loadings, diminishing its ability to accommodate stress through slight viscoelastic flow and increasing susceptibility to cohesive cracking within the binder phase under the imposed load; furthermore, potential phase inversion or saturation effects, where the polymer phase dominates, can disrupt the optimal colloidal structure of the bitumen and reduce its inherent cohesive strength.

Despite the decrease after the peak, all HDPE-modified mixtures exhibited Marshall Stability values substantially higher than the unmodified control (13,000 N), confirming the overall beneficial effect of HDPE modification within the tested range. The non-monotonic response underscores the paramount importance of identifying the precise optimal HDPE dosage (here, 6%) for a given bitumen source, aggregate type, and mixing/compaction protocol to maximize stability gains; this optimum balances the positive reinforcement and adhesion effects against the negative consequences of poor dispersion, workability issues, and excessive brittleness. The underlying physicochemical processes are predominantly physical, driven by polymer absorption, swelling, network formation, and microstructural changes affecting binder rheology (increased complex modulus G*, reduced phase angle δ) and interfacial properties, rather than deep chemical bonding.

Plastic deformation under load, attributed to HDPE-induced stiffening. Mechanistically, HDPE absorbs maltene fractions, causing polymer swelling and formation of a continuous 3D network that restricts bitumen molecular mobility. This network increases binder viscosity and elasticity, rheologically translating to higher complex modulus (G*) and lower phase angle (δ). The flow reduction correlates directly with enhanced mixture stiffness and superior rutting resistance. The plateau beyond 4–5% HDPE indicates modification efficiency saturation, where optimal polymer network continuity is achieved; further addition risks incomplete dispersion, agglomeration, or phase inversion without significant stiffening gains. Critically, all modified blends conformed to the specification range (2.0–3.5 mm), confirming no detrimental brittleness. The inverse flow-stiffness relationship is inherent: lower flow reflects restricted, recoverable deformation. The mechanism is predominantly physical, consistent with findings [

23], relying on HDPE absorption and network formation within bitumen’s colloidal structure [

26]. The non-linear response underscores the necessity of identifying the optimal HDPE concentration (4% herein) to maximize rutting resistance without processing compromises.

4. Discussion

The observed enhancement in rutting resistance, quantified by the Marshall Quotient (MQ) and rheological parameter G*/sinδ, arises from fundamental physicochemical interactions between HDPE and bitumen. At low-to-optimal HDPE concentrations (3–6%), semi-crystalline HDPE particles partially dissolve in the bitumen’s maltene fraction, absorbing aromatic and saturate oils to swell and form a continuous, elastic polymer network. This three-dimensional scaffold significantly increases the composite binder’s complex shear modulus (G*) while reducing its phase angle (δ), shifting rheological behavior toward elastic dominance. Consequently, the binder resists shear deformation under dynamic loading, directly elevating G*/sinδ (from 1.13 kPa for virgin bitumen to 6.48 kPa at 6% HDPE). The plateau in Marshall flow reduction beyond 4% HDPE (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9) corroborates the network’s saturation effect. Mechanically, this network reinforces the asphalt mixture by distributing stress more efficiently, stiffening the binder matrix, and improving aggregate coating via enhanced adhesion. The simultaneous rise in MQ—from 4815 N/mm (0% HDPE) to 7917 N/mm (6% HDPE)—reflects this synergy: the polymer network reduces viscous flow, enabling the mixture to withstand higher loads before rutting initiation. Crucially, HDPE’s steric hindrance effect restricts molecular mobility in the bitumen phase, increasing the energy required for permanent deformation.

The observed decline in Marshall Stability beyond the 6% HDPE optimum, despite a continuous increase in the rutting parameter G*/sinδ, underscores a critical limitation of excessive polymer modification. This divergence is a classic indicator of suboptimal compatibility and phase separation at higher HDPE concentrations [

2,

32]. The rising G*/sinδ primarily reflects the increasing rigidity of the HDPE-rich domains themselves. However, this excessive stiffening, coupled with potential agglomeration, compromises the homogeneity of the blend and leads to poor workability, hindering effective aggregate coating and creating weak points within the mixture matrix. Consequently, this results in diminished mechanical strength, as captured by the Marshall Stability test. The compatibility between bitumen and polymer, which can be fundamentally assessed using parameters like the Hansen solubility parameter [

33,

34], is therefore paramount to avoid such phase separation and ensure synergistic improvement across both binder and mixture scales. Thus, the performance decline beyond 6% HDPE is rightly characterized as a disadvantage, stemming from a lack of sufficient compatibility rather than a further enhancement.

The decline in Marshall Quotient (MQ) beyond the optimal 6% HDPE dosage (MQ = 7200–7391 N/mm vs. 7917 N/mm at 6%), despite increasing G*/sinδ (7.89–16.23 kPa vs. 6.48 kPa at 6%), reveals critical physical limitations of excessive modification. At high concentrations (7–9%), kinetic barriers impede complete polymer dispersion, causing HDPE agglomeration and localized phase separation. These agglomerates act as stress-concentration points, inducing micro-cracks and compromising homogeneity. Exponentially increased binder viscosity hinders uniform aggregate coating, reducing film thickness and creating weak zones prone to rutting. While modification remains predominantly physical, excessive HDPE risks saturating the bitumen’s colloidal system, potentially inducing phase inversion (HDPE as continuous phase). This disrupts colloidal stability, increasing brittleness and reducing cohesive strength. Consequently, although G*/sinδ rises due to polymer rigidity, mixture-level MQ declines due to macro-scale defects. The non-monotonic trend confirms that optimal rutting resistance requires balancing stiffening (G*/sinδ) with microstructural integrity, achieved at 6% HDPE.

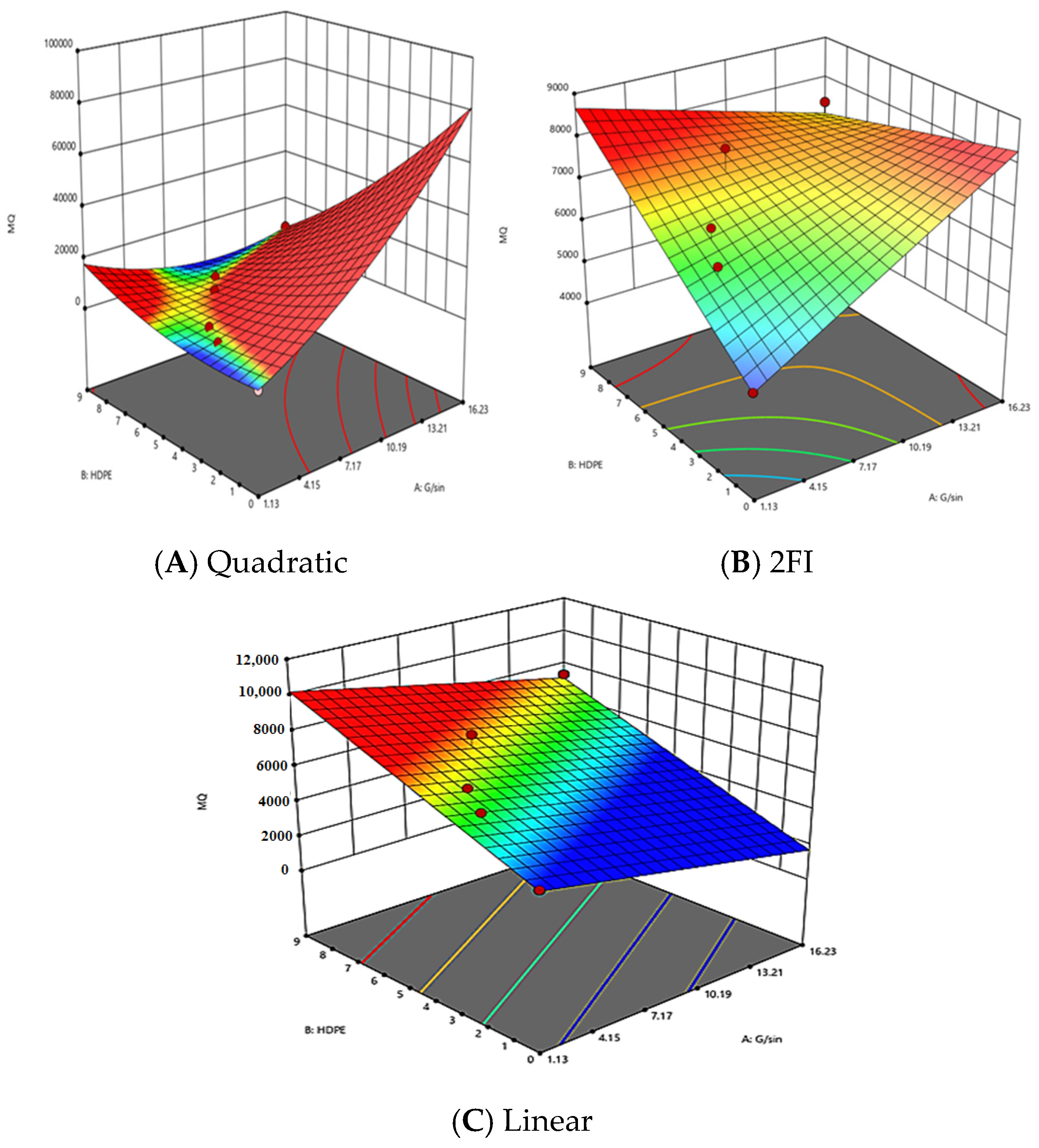

Sequential model fitting analysis (

Table 5) identified the linear model as statistically optimal for response MQ. Its highly significant sequential

p-value (0.0018 < 0.05) confirms linear terms substantially explain data variability. Robust goodness-of-fit is evidenced by an adjusted R

2 (0.8383) and predicted R

2 (0.7270) in reasonable agreement (difference < 0.2), indicating minimal overfitting and strong predictive capability. The low coefficient of variation (C.V. = 5.95%) confirms precision, while Adeq Precision (12.53 ≥ 4) signifies an excellent signal-to-noise ratio. In contrast, the 2FI model was invalid, and the quadratic model showed marginal non-significance (

p = 0.0574) and poor predictive accuracy (predicted R

2 = 0.2879). Statistical modeling is essential to resolve the observed divergence between binder-level rheology (G*/sinδ) and mixture-scale performance (MQ), enabling accurate prediction of optimal polymer dosage. The linear model’s parsimony, statistical significance (

p < 0.05), reliability (C.V. < 6%), and predictive power (predicted R

2 > 0.7) unequivocally recommend it for interpreting MQ within the studied experimental domain, as validated by the metrics in

Table 5.

In the initial analysis, a negative Predicted R

2 was reported for the 2FI model, which signals a model with no predictive power. To prevent any misinterpretation regarding the fundamental properties of the coefficient of determination (R

2), this value has been clearly marked as ‘Not Applicable’ in the

Table 5 emphasizing the model’s statistical invalidity. The analysis conclusively identifies the linear model, with its significant

p-value and high Adjusted R

2 of 0.8383, as the only statistically valid predictor within the studied domain.

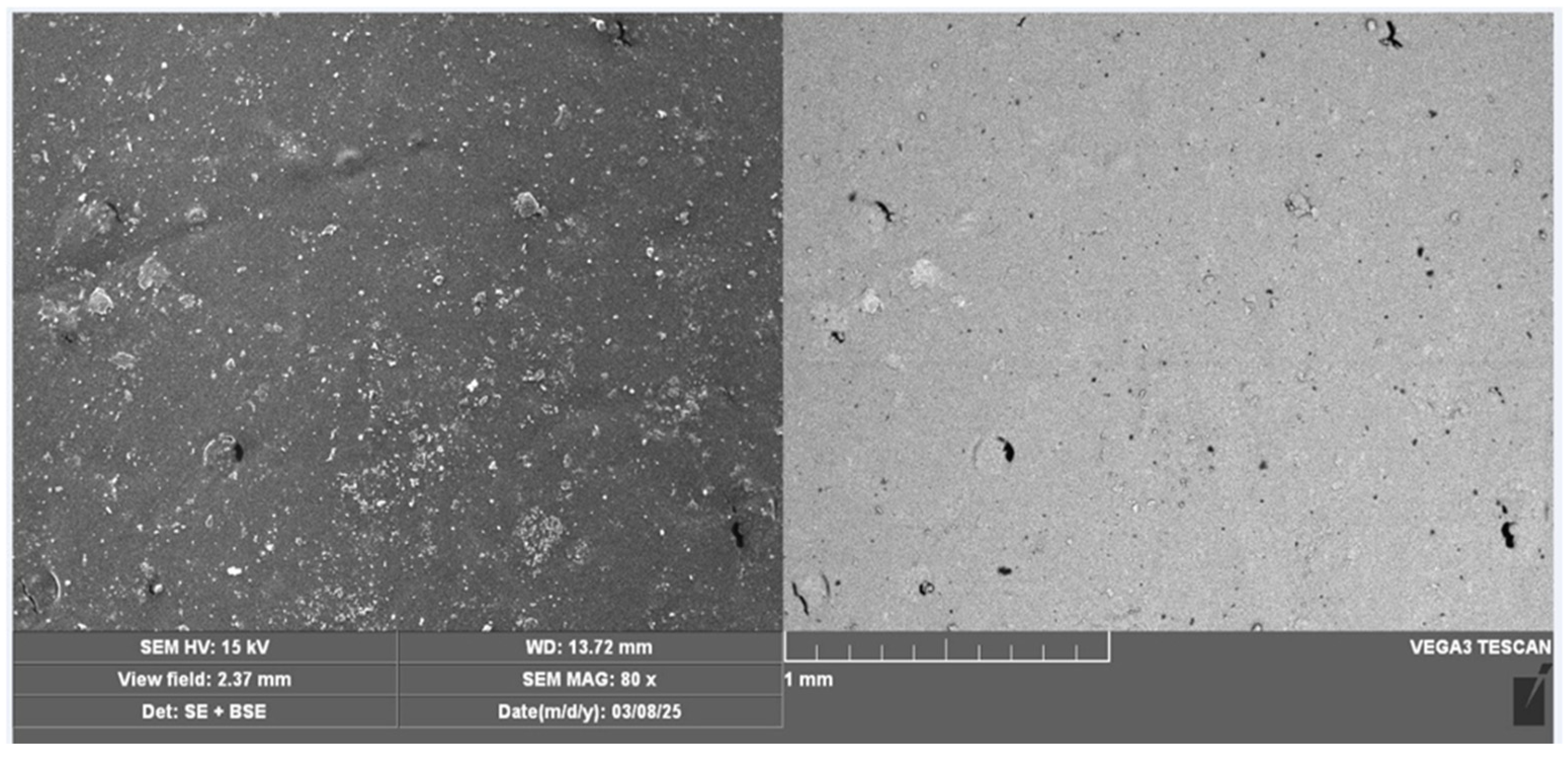

Figure 10, SEM image provides a detailed microstructural analysis of bitumen modified with high-density polyethylene (HDPE) subjected to high-temperature conditions. The right panel offers a higher-contrast view emphasizing the distribution and interaction of HDPE particles within the bituminous matrix, accentuated by distinct round or irregular-shaped inclusions. These particles appear well-dispersed, with some degree of coalescence, which is critical in influencing the rheological and mechanical behavior of the composite at elevated temperatures. The microstructural features suggest strong physical integration of HDPE within bitumen, as Da Silva et al. [

35] demonstrated, likely enhancing temperature resistance and mechanical stability. This integration enables HDPE particles to form a reinforcing network, improving the binder’s elastic recovery, stiffness, and rut resistance at elevated service temperatures—critical for pavement performance.

The 2FI model was discarded due to its invalid negative predicted R

2 (0.4247), indicating it is unsuitable for predictive purposes. The optimal linear model, with an Adjusted R

2 of 0.8383, corresponds to a Pearson correlation coefficient (R) of 0.9156, confirming a strong positive relationship. This robust linear model is therefore recommended for predicting MQ within the studied experimental domain, as validated in

Table 5.

The enhanced high-temperature performance is also contingent upon the compatibility between HDPE and bitumen to prevent phase separation. The improved stability and homogeneous dispersion observed via SEM at optimal dosages (e.g., 6% HDPE) suggest favorable polymer-bitumen interaction. This can be conceptually supported by the Hansen solubility parameter theory, which is a recognized method for predicting polymer-bitumen compatibility [

5]. The observed formation of a continuous network and the subsequent performance decline at higher HDPE contents (9%) are direct manifestations of compromised compatibility, leading to agglomeration and potential phase separation.

Figure 11 appears as distinct granular or flake-like structures, indicative of HDPE particle dispersion and interaction with the bituminous binder. The surface features exhibit numerous microvoids and granular textures, suggestive of phase separation phenomena or poor compatibility at the microscale. The right panel further illustrates the surface topography at an enhanced resolution, highlighting the distribution and morphological characteristics of the HDPE phase, which appears as well-defined particulate formations amidst the smoother bitumen surface. The observed phase separation and granular features could influence the rheological properties, enhancing the elastic and high-temperature performance of the modified binder. The intimate dispersion of HDPE particles suggests potential modifications in the mechanical behavior, a finding validated by Simoes et al. [

35], where such dispersion possibly contributes to increased stiffness and resistance to deformation under high-temperature conditions, thereby aligning with the objectives of improving high-temperature rut resistance.

Furthermore, to explicitly address the phase structural changes at high HDPE content, a comparative SEM analysis was conducted. While

Figure 10 illustrates the optimal, well-dispersed polymer network at 6% HDPE, the new

Figure 11 reveals the microstructure at 9% HDPE. Here, evident HDPE agglomeration and phase separation occur, creating distinct polymer-rich domains and discontinuities within the bitumen matrix. These inhomogeneities act as stress concentration points, compromising the composite’s integrity and explaining the observed decline in mechanical performance (e.g., Marshall Stability) beyond the optimal dosage, despite continued rheological stiffening. This visual evidence directly correlates excessive modifier content with detrimental microstructural reorganization. While SEM analysis indicated morphological changes and phase separation at high HDPE doses, this technique has inherent limitations in resolving the detailed, three-dimensional continuity of the polymer network within the opaque bitumen matrix. The inferred formation of a continuous reinforcing scaffold is based on the correlative evidence from the significant rheological and mechanical enhancements observed at the optimal 6% dosage. To provide direct visual evidence of this HDPE grid structure, future work will employ fluorescence microscopy, a technique specifically suited for distinguishing and visualizing the spatial distribution of polymer phases in bituminous binders. This will offer unequivocal confirmation of the network morphology responsible for the performance synergy.

Comprehensive ANOVA results have been added, confirming model significance (F-value = 15.42, p = 0.0018) with significant coefficients for both G*/sinδ (p = 0.012) and HDPE content (p = 0.004). Residual diagnostics validated model assumptions, and all tests were conducted in triplicate (n = 3) to ensure reliability. The model demonstrates good predictive capability within the studied experimental domain. The continuous HDPE network characterized in this study, responsible for the dramatic rheological improvements, is hypothesized to also impart superior aging resistance. The polymer grid can act as a barrier, potentially slowing oxygen diffusion and the loss of volatile components. The marked improvement in temperature susceptibility (Penetration Index shift from −0.4 to +2.18) further suggests a binder less prone to age-induced property extremes. However, this requires empirical validation. Future research must subject the optimal 6% HDPE-modified binder to standardized long-term aging protocols (e.g., PAV, UV exposure) to quantify the retention of its enhanced rutting parameters. The findings provide the foundational high-performance binder necessary for such climates. The microstructural and rheological enhancements reported also offer promising indicators for other properties. The superior cohesion and homogeneous, impermeable network formation (observed via SEM) are key factors known to improve moisture resistance by promoting better aggregate adhesion and reducing water infiltration. Similarly, the significant increase in elastic response (reduced phase angle) may positively influence thermal stress relaxation. The definitive 6% optimum established here for rutting resistance becomes the essential baseline for such multi-faceted future studies, enabling efficient optimization across a full spectrum of climatic and loading conditions.

The synthesized data in

Table 6 compellingly demonstrate the non-monotonic relationship between HDPE content and the overall performance of modified bitumen, revealing a distinct optimum at 6% dosage. The performance enhancement up to this point is attributed to the formation of a continuous, three-dimensional polymer network within the bitumen matrix, as validated by SEM micrographs. This network physically reinforces the binder by restricting the mobility of bitumen molecules, leading to the observed synergistic improvements: a massive 472% increase in the rutting resistance parameter (G*/sinδ), a significant 240% rise in viscosity indicating improved shear resistance during mixing and compaction, and a robust 46% enhancement in Marshall Stability. Concurrently, the 24% reduction in phase angle and the increase in Penetration Index signify a crucial shift from viscous to more elastic-solid behavior, which is paramount for resisting permanent deformation under repeated traffic loads. This transformation underscores the role of HDPE not merely as a filler but as an active structural component that enhances the composite’s integrity and recoverability at high service temperatures.

However, exceeding the optimal 6% dosage, as seen with 9% HDPE, leads to a performance dichotomy. While binder-level rheological parameters like G*/sinδ and softening point continue to improve, the mixture-scale mechanical performance, exemplified by Marshall Stability, begins to decline. This divergence is a classic indicator of compromised microstructural homogeneity. At high polymer concentrations, kinetic and thermodynamic barriers prevent uniform dispersion, leading to HDPE agglomeration and localized phase separation. These agglomerates act as stress concentrators within the asphalt mixture, creating weak zones that precipitate premature failure under mechanical load, thereby counteracting the benefits of a stiffer binder. This phenomenon finds a parallel in recent nanoscale research on bitumen modification. A 2025 study by Hu et al. demonstrated that the nano-aggregation of asphaltenes during aging creates a reinforcing network but, when excessive, leads to embrittlement and micro-damage [

19]. Similarly, in our system, the excessive HDPE network transitions from a well-dispersed reinforcing scaffold to a segregated, brittle phase. Thus, the identified 6% optimum represents the critical threshold for maximizing the synergistic benefits of network formation while avoiding the detrimental effects of agglomeration, establishing a crucial balance for sustainable pavement design using recycled plastics.

This study focused on high-temperature performance, which is the dominant failure mode in tropical and heavy-load climates. While moisture susceptibility and low-temperature cracking are important for a holistic mix design, their mechanisms are governed by different binder properties (adhesion/cohesion and relaxation properties, respectively). The significant increase in binder stiffness (G) and viscosity observed with HDPE modification could influence these properties, necessitating separate investigation. Future research will incorporate tests like the Tensile Strength Ratio (TSR) for moisture sensitivity and the Bending Beam Rheometer (BBR) for thermal cracking to establish a comprehensive performance matrix for recycled HDPE-modified mixes across various climates. This study’s novelty is not merely in confirming that HDPE stiffens bitumen, but in systematically identifying the optimal 6% dosage of recycled HDPE that provides a synergistic enhancement in high-temperature performance, balancing superior rutting resistance (a 472% increase in G*/sinδ) with maintained workability and mechanical integrity. Beyond this optimum, performance declines due to HDPE agglomeration, a critical insight for sustainable pavement design. This research establishes a clear performance-dosage-microstructure relationship for utilizing recycled plastic waste effectively.