Temperature and Speed Corrections for TSD-Measured Deflection Slopes Using 3D Finite Element Simulations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Objective and Scope

3. Materials and Methods

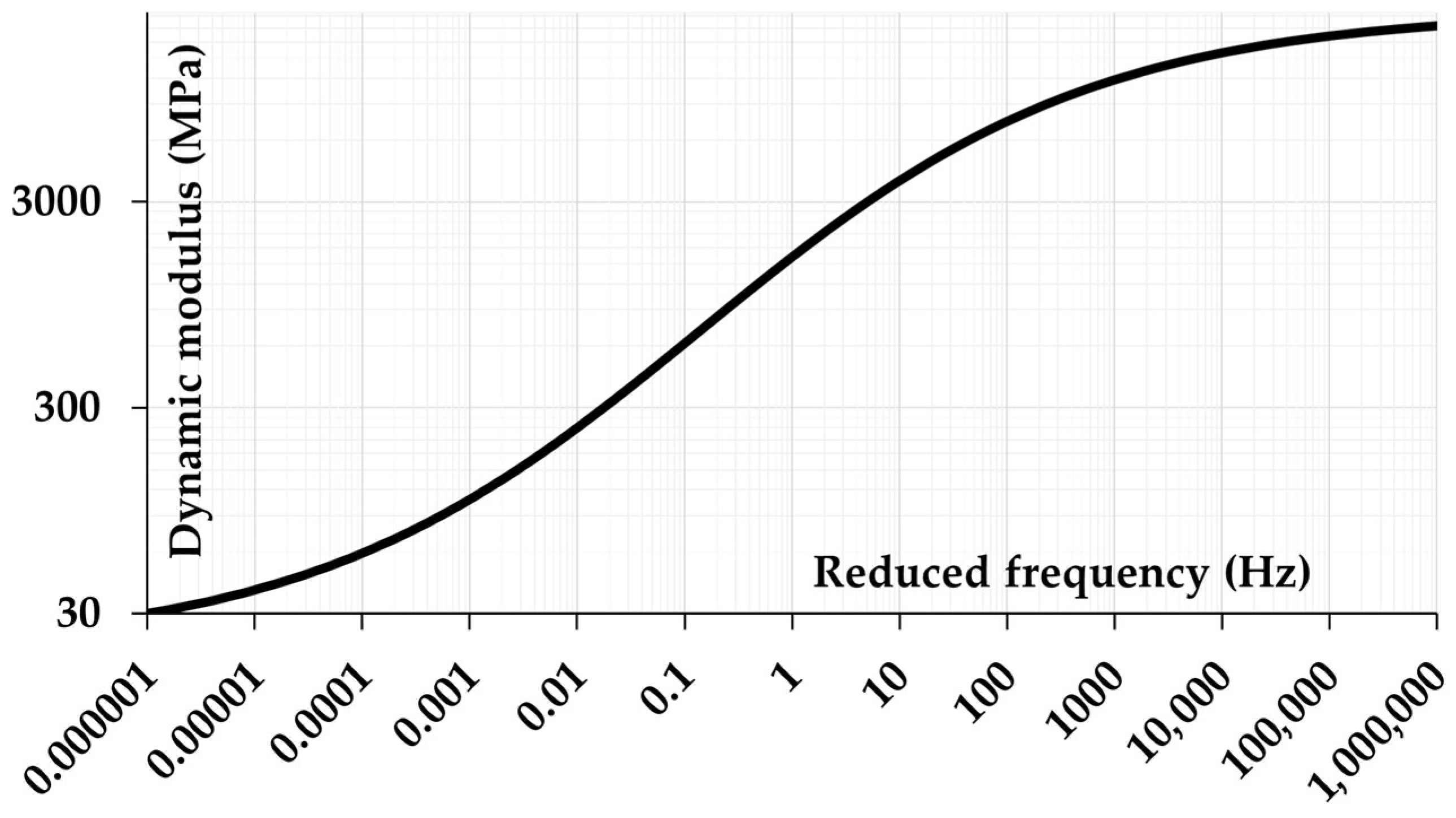

3.1. Material Properties in FEM

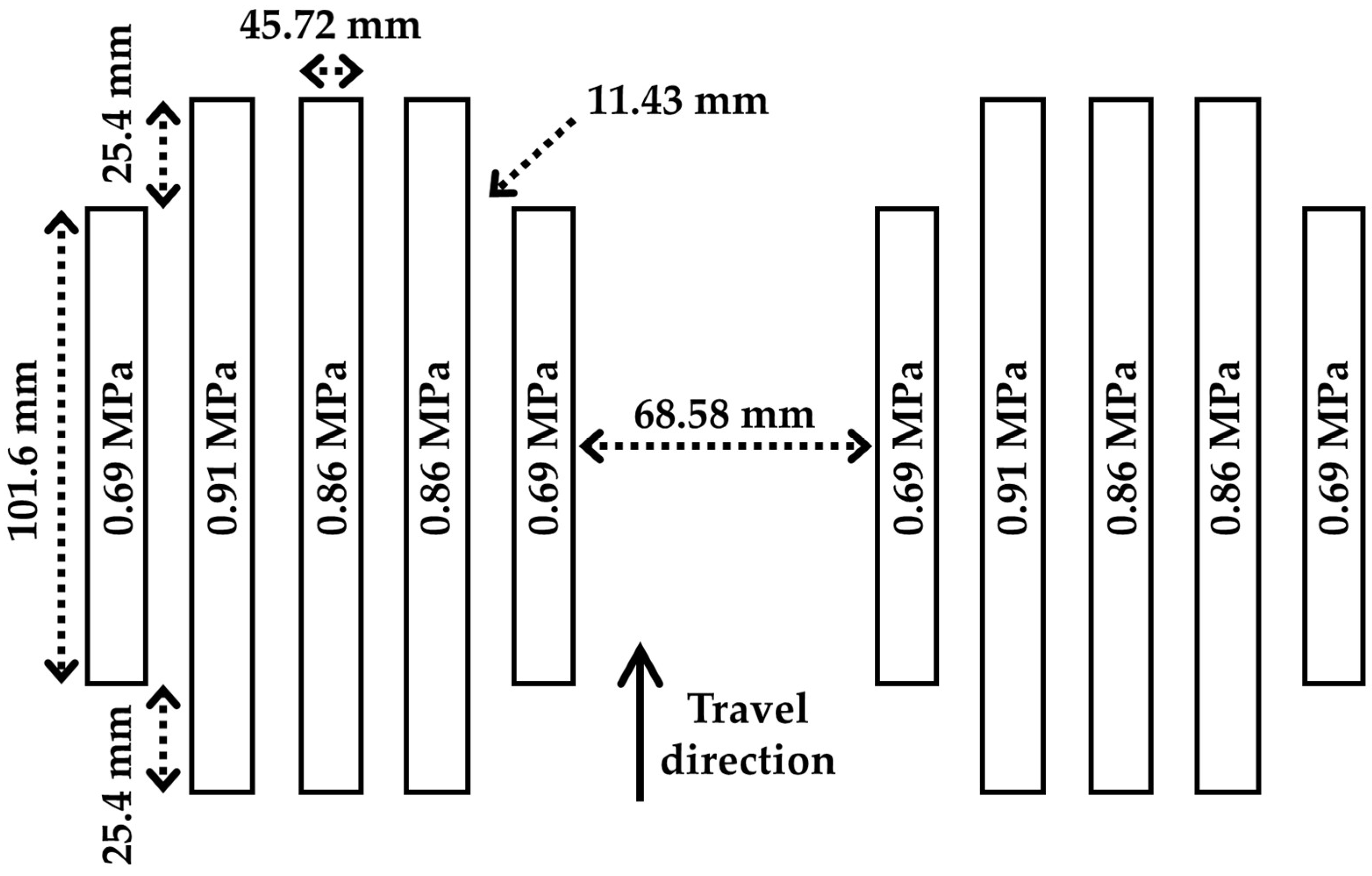

3.2. Loading Configuration in FEM

3.3. Model Geometry in FEM

4. Results and Discussion

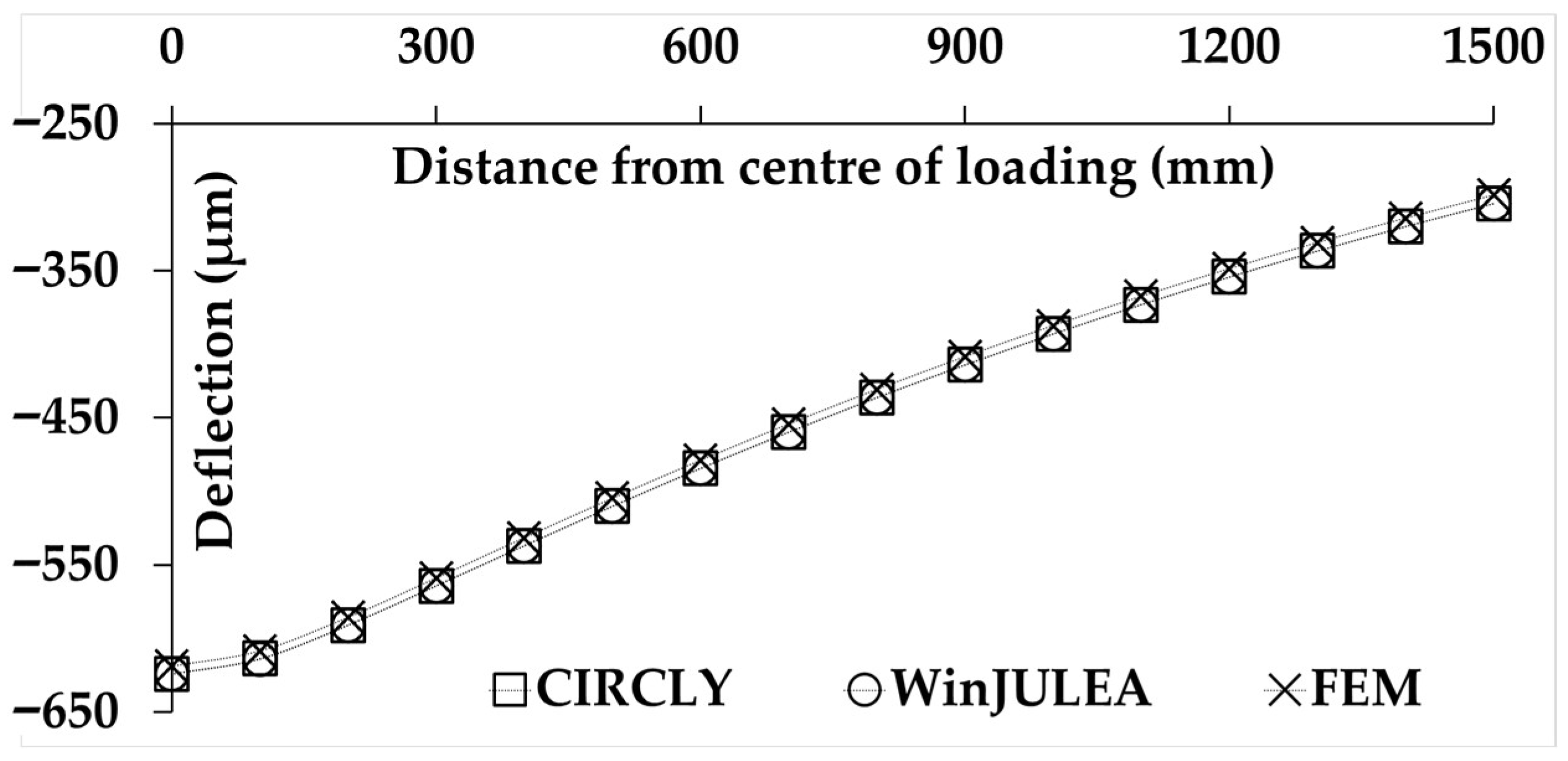

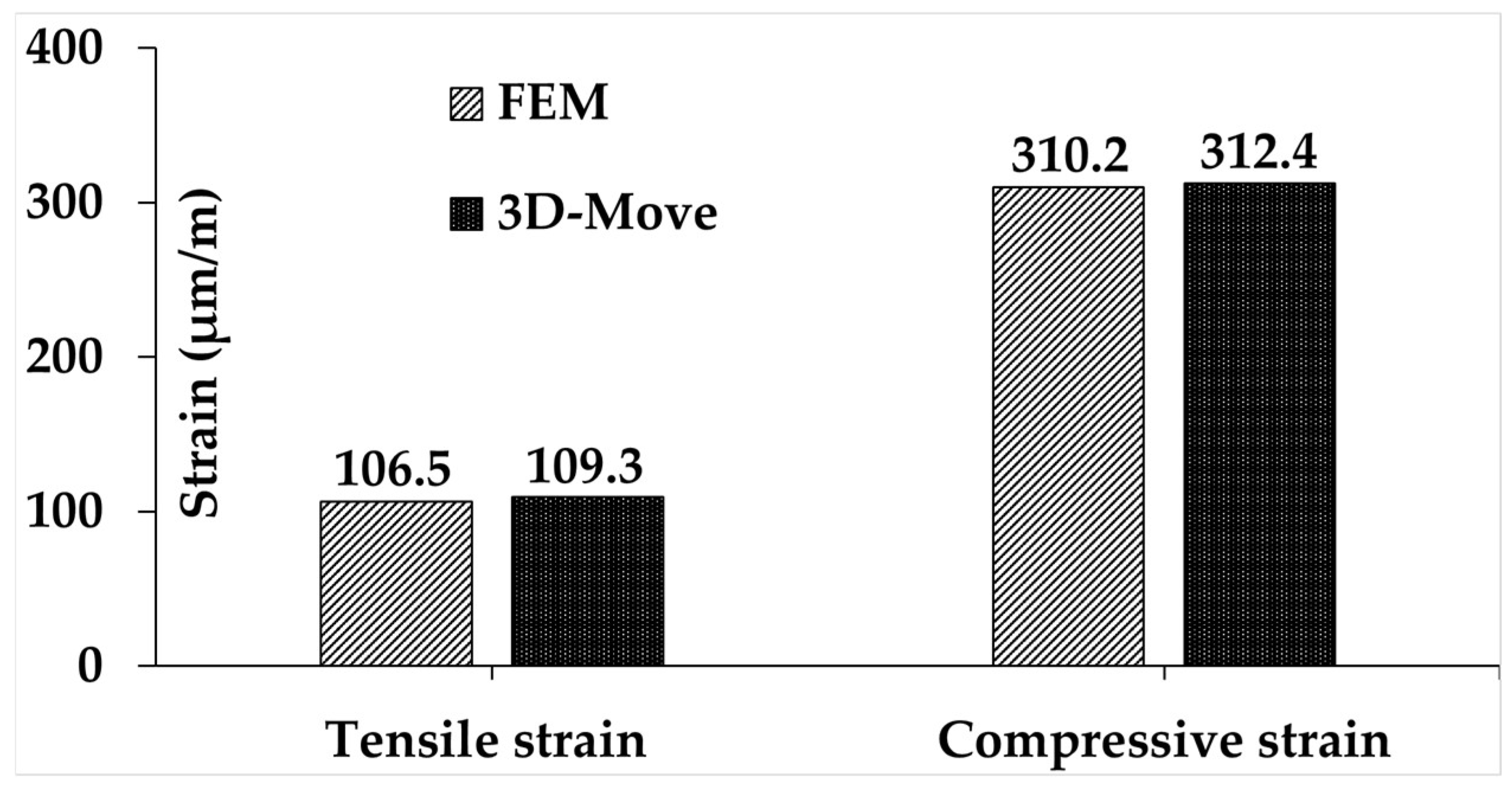

4.1. Theoretical Validation of FEM Simulations

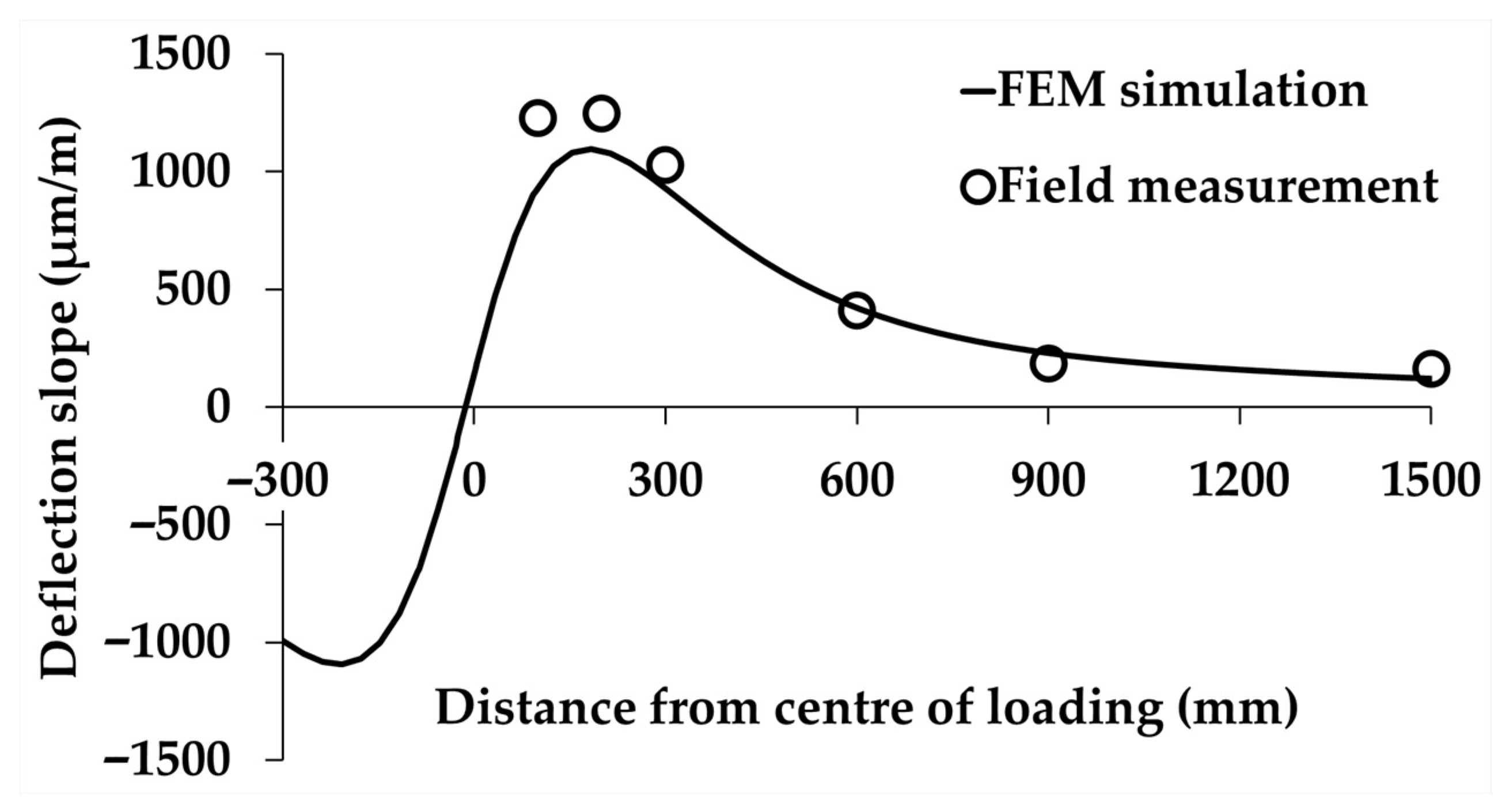

4.2. Field Validation of FEM Simulations Based on MnROAD Measurements

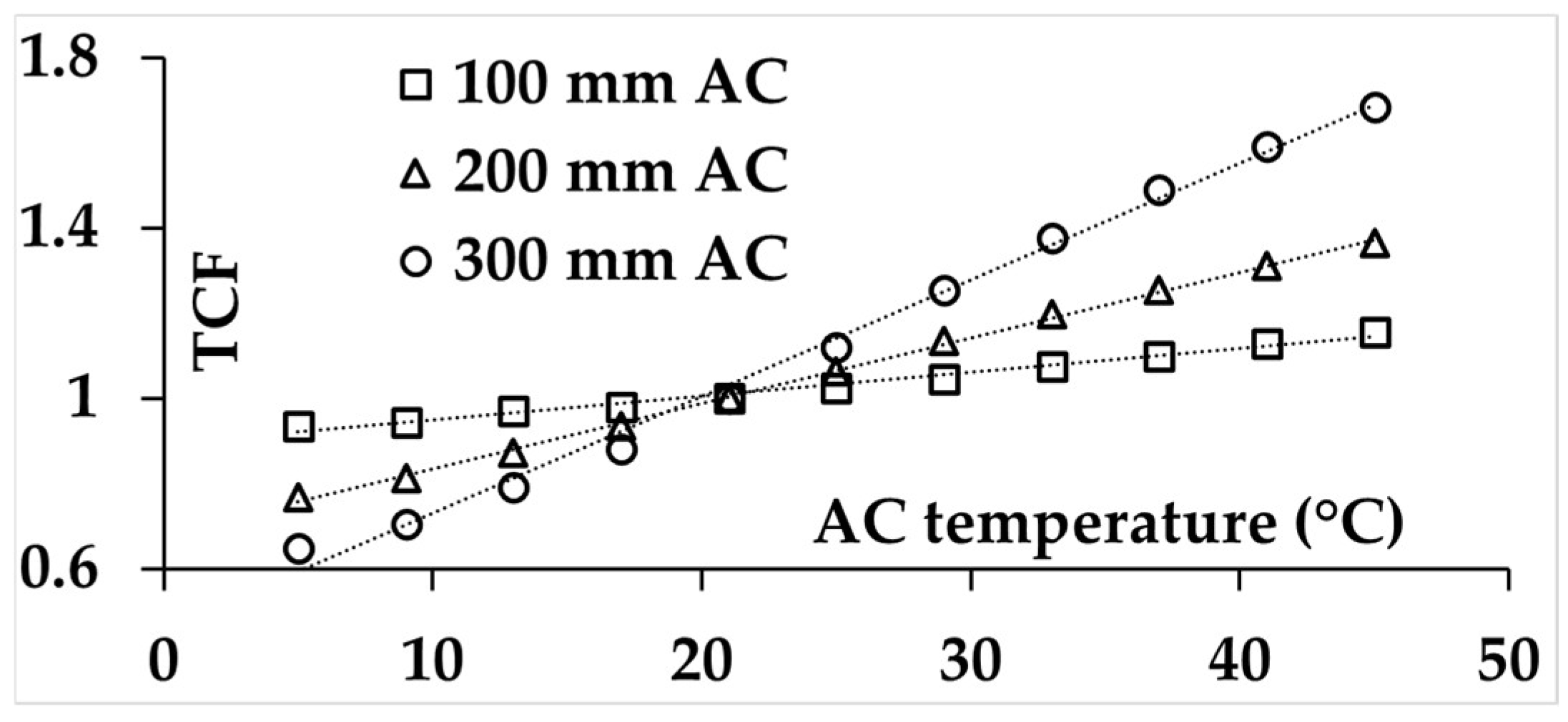

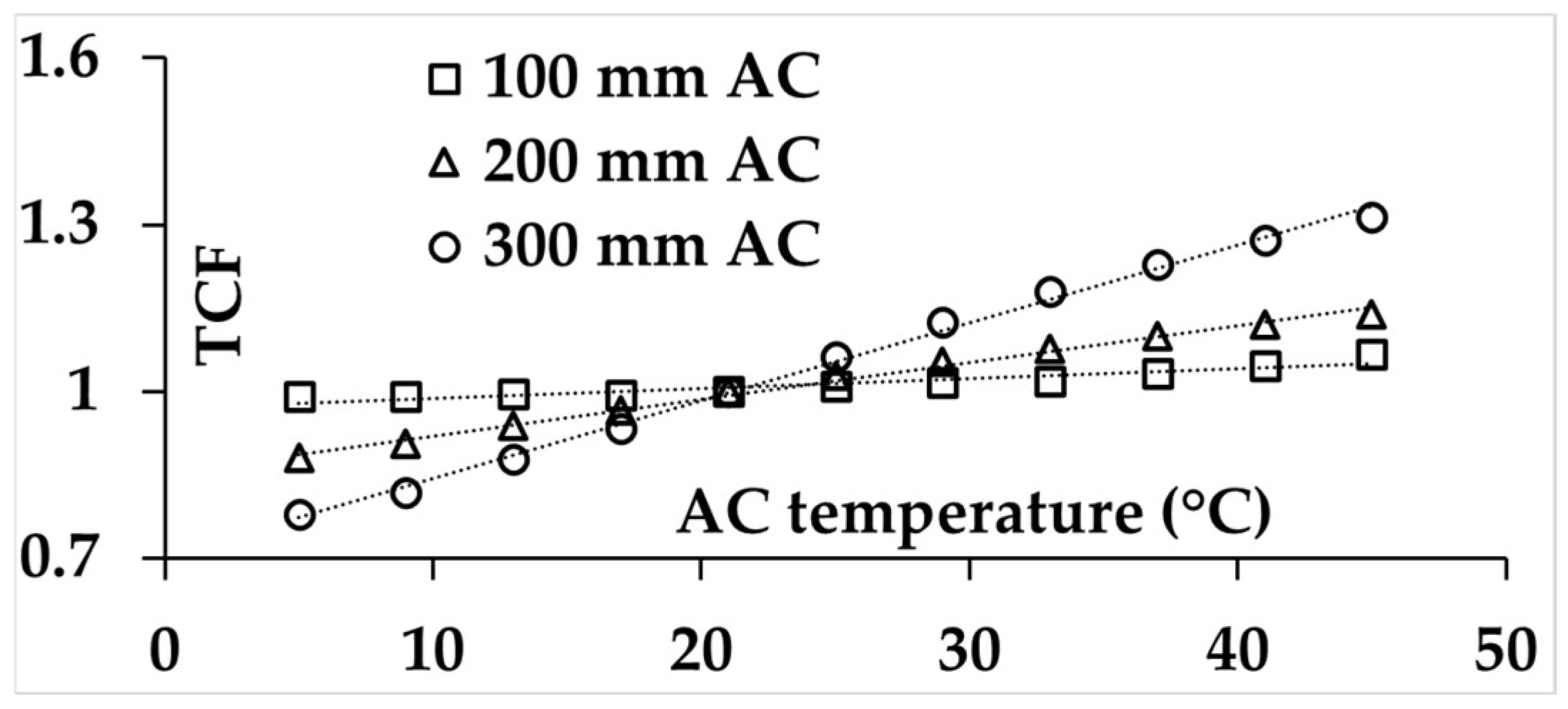

4.3. Temperature Correction of Deflection Slopes

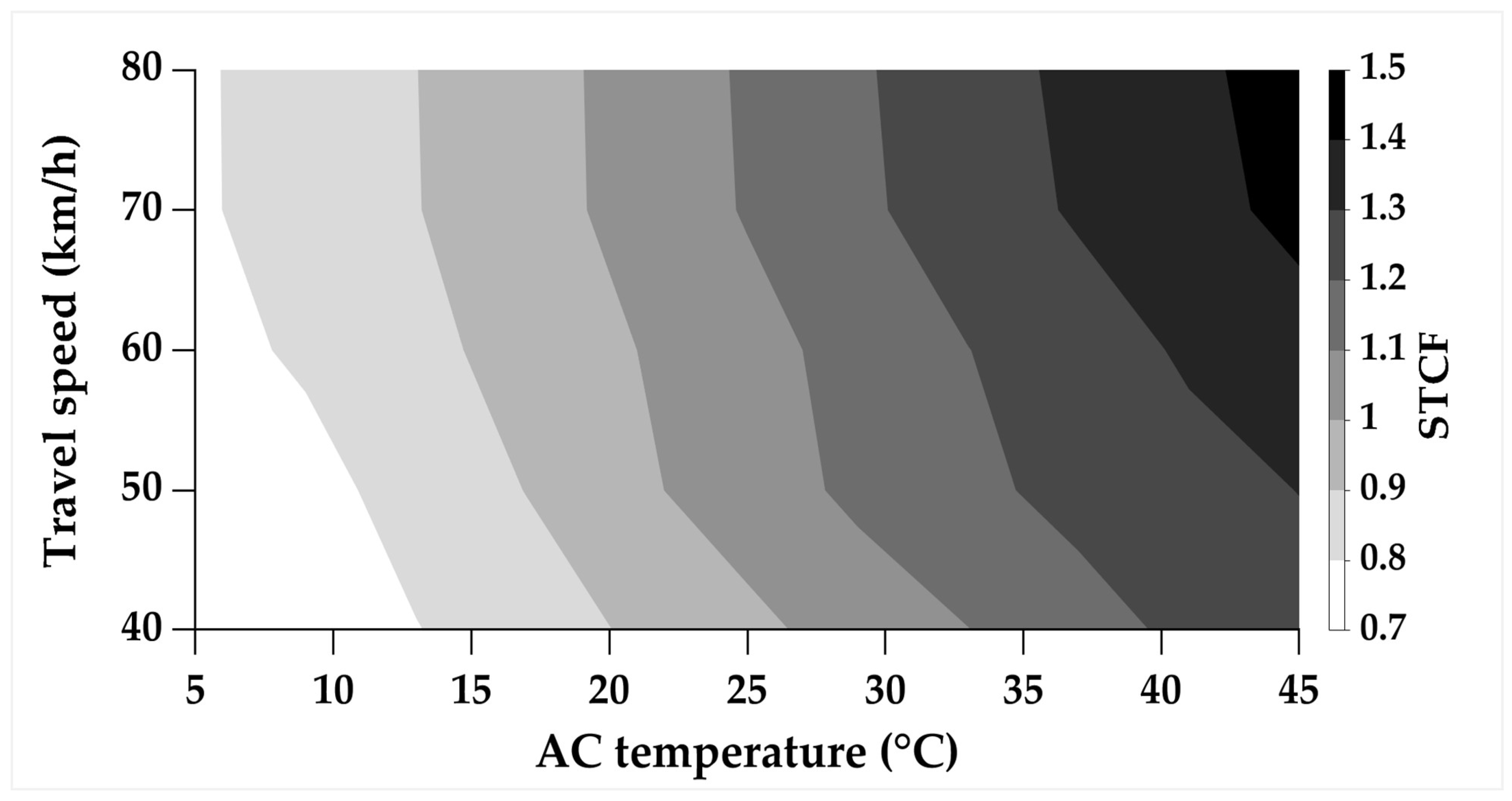

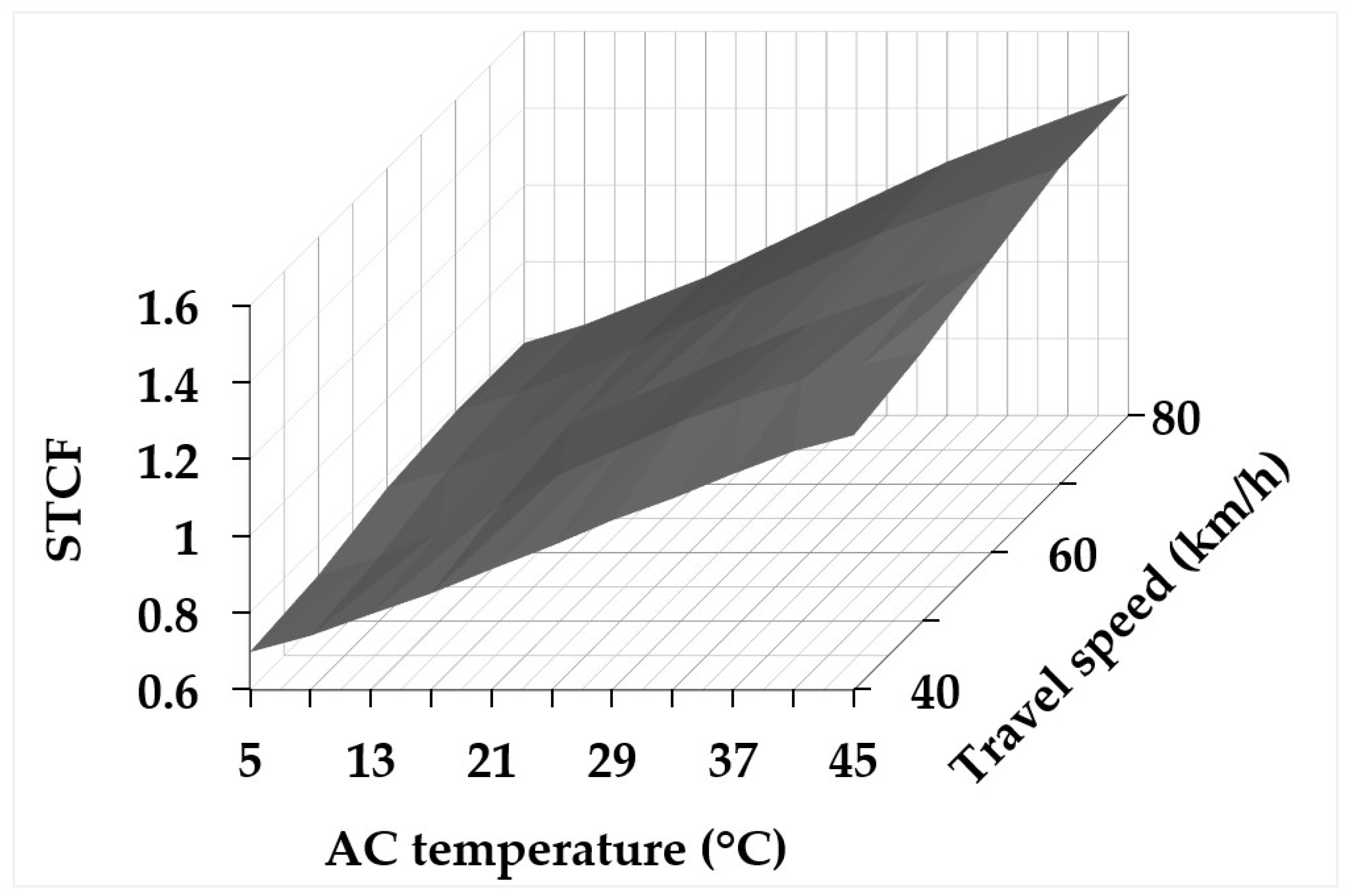

4.4. Simultaneous Speed and Temperature Correction of Deflection Slopes

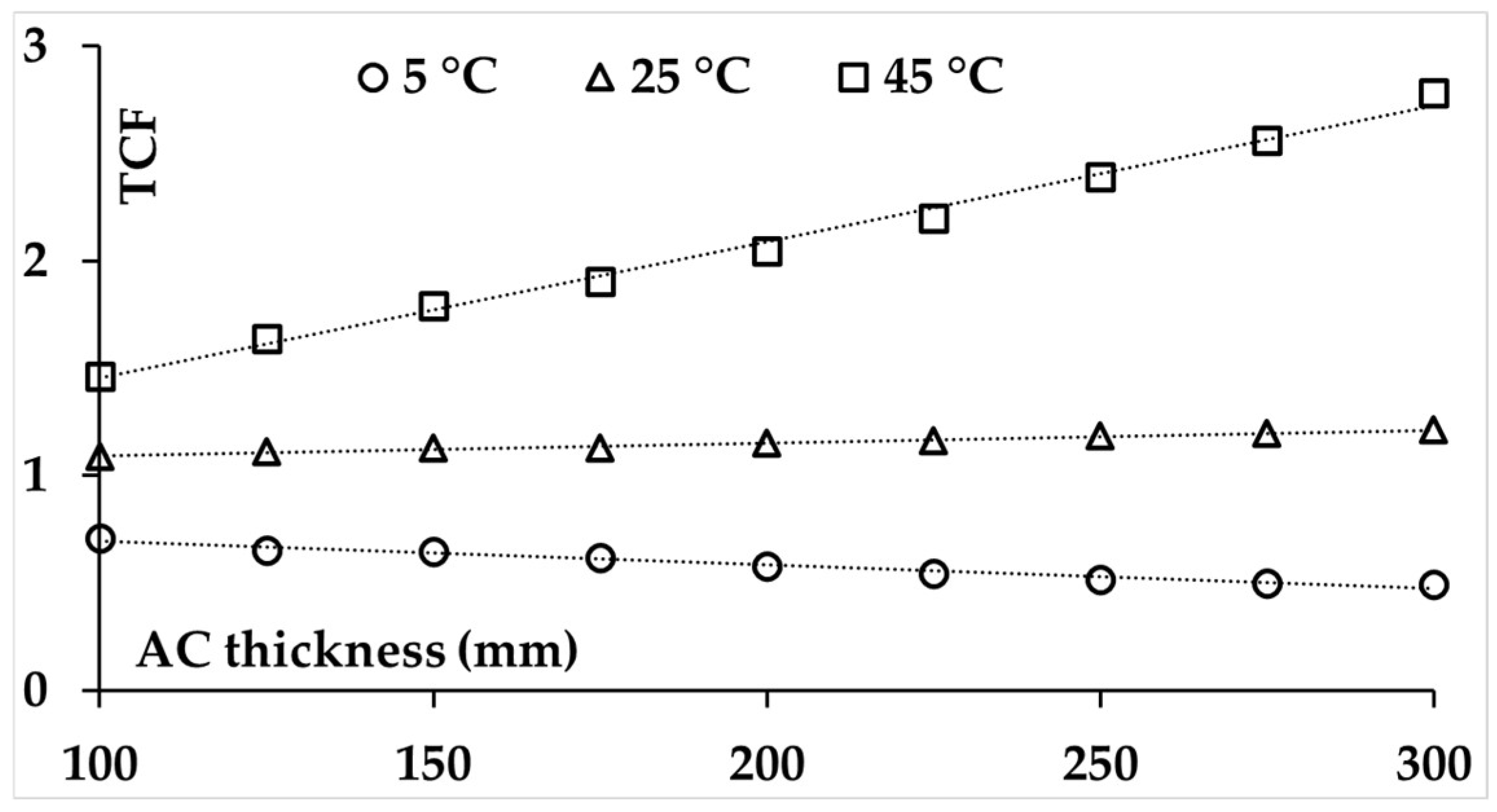

4.5. Correlation Between Temperature Correction Factor and AC Thickness

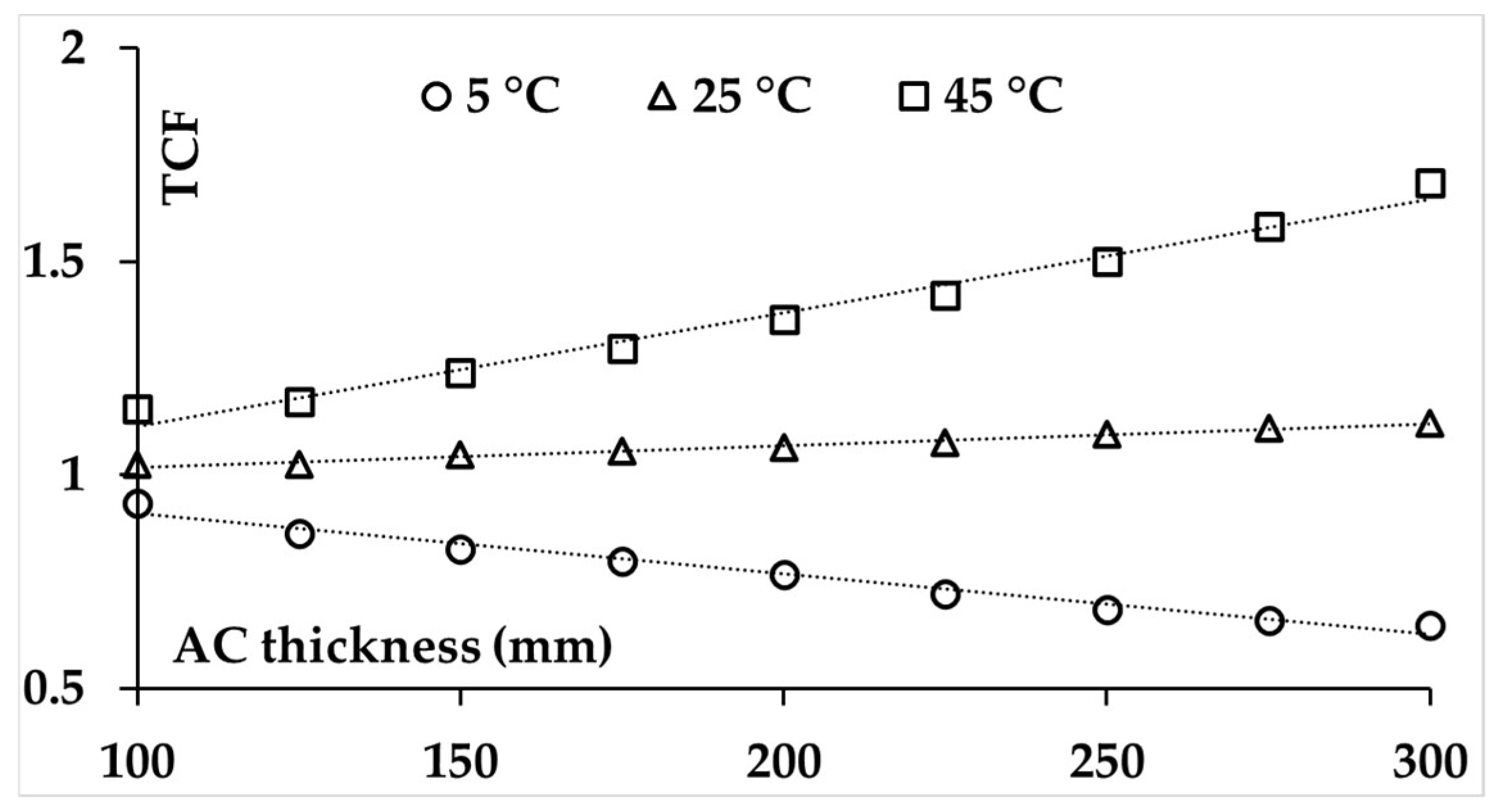

4.6. Simultaneous Speed and Temperature Correction Considering the AC Layer’s Thickness

5. Conclusions

6. Study Limitations and Path Towards Future Research

- -

- Only a limited number of pavement structures were evaluated, primarily to demonstrate the capability of developing correction factors for deflection slopes by accounting for AC temperature, travel speed, and AC thickness. It is recommended that future studies expand the FEM simulations to include a wider range of pavement structures by considering different material properties and layer thicknesses. This will help ensure that the regression equations with the developed structures are applicable to a broad spectrum of pavement configurations and can be extended to incorporate all relevant characteristics of pavement systems in terms of material properties and layer thicknesses. Expanding the range of pavement structures in future studies would require consideration of different aggregate gradations and bitumen types for the AC layer, resulting in different AC moduli, as well as varying base and subgrade layers’ moduli and AC and base layer thicknesses.

- -

- Some simplifications were made regarding the material properties of pavement layers. The temperature gradient within the AC layer was disregarded, and the AC layer was assumed to possess a uniform effective temperature throughout its entire thickness. The base and subgrade layers were considered to behave as linear elastic materials in the FEM simulations, with their nonlinear stress-dependent and cross-anisotropic behaviour neglected. The effect of moisture on subgrade stiffness was also not considered.

- -

- FEM simulations were performed using an equivalent circular loading simplification of a specific rear axle configuration for the TSD vehicle at the MnROAD facility, which limits the generality of the study findings. Furthermore, the effect of pavement surface roughness on the excitation of tyre load magnitude [43] was not considered.

- -

- Finally, although the range of AC temperatures considered in the study is relatively comprehensive, the findings could be further strengthened by including some negative AC temperatures in the FEM simulations. Additionally, considering a wider range of TSD travel speeds, particularly below 40 km/h and above 80 km/h, is important to enhance the comprehensiveness of the study.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3D | Three-Dimensional |

| AASHTO | American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials |

| AC | Asphalt Concrete |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| FEA | Finite Element Analysis |

| FEM | Finite Element Method |

| FWD | Falling Weight Deflectometer |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| PG | Performance Grade |

| ReLU | Rectified Linear Unit |

| SAFEM | Semi-Analytical Finite Element Method |

| SCI | Surface Curvature Index |

| STCF | Speed and Temperature Correction Factor |

| TCF | Temperature Correction Factor |

| TSD | Traffic Speed Deflectometer |

| TSDDs | Traffic Speed Deflection Devices |

| WLF | Williams–Landel–Ferry |

References

- Kim, Y.R. Modeling of Asphalt Concrete; McGraw-Hill Education: Columbus, OH, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0071464628. [Google Scholar]

- Lukanen, E.O.; Stubstad, R.; Briggs, R. Temperature Predictions and Adjustment Factors for Asphalt Pavement; Report No. FHWA-RD-98-085; Turner-Fairbank Highway Research Center, Federal Highway Administration, US Department of Transportation: McLean, VA, USA, 2000.

- Zhang, M.; Fu, G.; Ma, Y.; Xiao, R.; Huang, B. Speed and Temperature Superposition on Traffic Speed Deflectometer Measurements. Transp. Geotech. 2023, 40, 100990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guide for Design of Pavement Structures; American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO): Washington, DC, USA, 1993.

- Ferne, B.W.; Langdale, P.; Round, N.; Fairclough, R. Development of a Calibration Procedure for the UK Highways Agency Traffic-Speed Deflectometer. Transp. Res. Rec. 2009, 2093, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rada, G.R.; Nazarian, S.; Visintine, B.A.; Siddharthan, R.; Thyagarajan, S. Pavement Structural Evaluation at the Network Level: Final Report; Report No. FHWA-HRT-15–074; Federal Highway Administration, US Department of Transportation: McLean, VA, USA, 2016.

- Shrestha, S.; Katicha, S.W.; Flintsch, G.W.; Thyagarajan, S. Application of Traffic Speed Deflectometer for Network-Level Pavement Management. Transp. Res. Rec. 2018, 2672, 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasimifar, M.; Chaudhari, S.; Thyagarajan, S.; Sivaneswaran, N. Temperature Adjustment of Surface Curvature Index from Traffic Speed Deflectometer Measurements. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2020, 21, 1408–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddharthan, R.V.; Yao, J.; Sebaaly, P.E. Pavement Strain from Moving Dynamic 3D Load Distribution. J. Transp. Eng. 1998, 124, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasimifar, M.; Kamalizadeh, R.; Heidary, B. The Available Approaches for using Traffic Speed Deflectometer Data at Network Level Pavement Management System. Measurement 2022, 202, 111901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, K.; Wang, H.; Canestrari, F.; Graziani, A. Temperature Correction for Traffic Speed Deflectometer Measurements on Flexible Pavement using ANN Models. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2025, 26 (Suppl. 1), 751–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wang, H.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, X.; Qiu, Y. Asphalt Pavement Modulus Backcalculation using Surface Deflections under Moving Loads. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2020, 35, 1246–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wei, J.; Hou, X.; Wu, C. Evaluation of Deflection Errors in Traffic Speed Deflectometer Measurements on Inverted Asphalt Pavement Structures. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Chen, Z.; Cheng, H.; Sun, L.; Li, Y.; Min, X.; Jin, F. Improved Deflection Calculation Methods for Traffic Speed Deflectometers for Asphalt Pavement Condition Assessments. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2025, 26, 2498080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABAQUS; Dassault Systèmes Simulia Corp.: Johnston, RI, USA, 2022.

- Katicha, S.; Flintsch, G.; Diefenderfer, B. Ten Years of Traffic Speed Deflectometer Research in the United States: A Review. Transp. Res. Rec. 2022, 2676, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TP 62-07; Standard Method of Test for Determining Dynamic Modulus of Hot Mix Asphalt (HMA). Standard Specifications for Transportation and Methods of Sampling and Testing. American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO): Washington, DC, USA, 2009.

- Williams, M.L.; Landel, R.F.; Ferry, J.D. The Temperature Dependence of Relaxation Mechanisms in Amorphous Polymers and other Glass-forming Liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1955, 77, 3701–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Schapery, R. Methods of Interconversion between Linear Viscoelastic Material Functions. Part I—A Numerical Method Based on Prony Series. Int. J. Solids Struct. 1999, 36, 1653–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellinen, T.K.; Witczak, M.W.; Bonaquist, R.F. Asphalt Mix Master Curve Construction using Sigmoidal Fitting Function with Non-linear Least Squares Optimization. In Recent Advances in Materials Characterization and Modeling of Pavement Systems; Geotechnical Special Publication No. 12; American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE): Reston, VA, USA, 2003; pp. 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABAQUS 2016 Analysis User’s Guide Volume 3: Materials; Dassault Systèmes Simulia Corp.: Providence, RI, USA, 2015.

- Kim, S.; Kim, H. A New Metric of Absolute Percentage Error for Intermittent Demand Forecasts. Int. J. Forecast. 2016, 32, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C.D. Industrial and Business Forecasting Methods: A Practical Guide to Exponential Smoothing and Curve Fitting; Butterworth Scientific: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1982; ISBN 978-0408005593. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Li, J.; Hu, Y.; Sun, L. Study on Temperature Correction of Asphalt Pavement Deflection Based on the Deflection Change Rate. Appl. Sci. 2022, 13, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walia, A.; Rastogi, R.; Kumar, P.; Jain, S.S. Determination of Effective Depth to Measure Temperature Required for Structural Evaluation of Asphalt Pavements. J. Transp. Eng. Part B. Pavements 2021, 147, 04021040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inge, E.H., Jr.; Kim, Y.R. Prediction of Effective Asphalt Layer Temperature. In Transportation Research Record 1473; Transportation Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; pp. 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Qadi, I.L.; Wang, H.; Tutumluer, E. Dynamic Analysis of Thin Asphalt Pavements by using Cross-Anisotropic Stress-Dependent Properties for Granular Layer. Transp. Res. Rec. 2010, 2154, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.F.; Pappin, J. Analysis of Pavements with Granular Bases. In Transportation Research Record 810; Transportation Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 1981; pp. 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Tarefder, R.A.; Ahmed, M.U.; Rahman, A. Effects of Cross-Anisotropy and Stress-Dependency of Pavement Layers on Pavement Responses under Dynamic Truck Loading. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2016, 8, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzan, J. Characterization of Granular Material. In Transportation Research Record 1022; Transportation Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 1985; pp. 52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi, N.; Saleh, M.; Lee, C.-L. Effect of the Stress Dependency and Anisotropy of Unbound Granular Base and Subgrade Materials on TSD Deflection Slopes. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Transportation and Development (ICTD), Atlanta, GA, USA, 15–18 June 2024; pp. 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, N.; Saleh, M.; Lee, C.-L. Effect of Nonlinear Stress-Dependency and Cross-Anisotropy on the Backcalculation Outputs from the TSD Deflection Slopes and the Effect on Estimated Pavement Performance. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2024, 25, 2417967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-L. Proportional Viscous Damping Model for Matching Damping Ratios. Eng. Struct. 2020, 207, 110178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.J.; Puthanpurayil, A.M.; Lavan, O.; Dhakal, R.P. Damping Models for Inelastic Time History Analysis: A Proposed Modelling Approach. In Proceedings of the 16th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering (WCEE), Santiago, Chile, 9–13 January 2017; Volume 11, pp. 7696–7705. [Google Scholar]

- Nasimifar, M.; Thyagarajan, S.; Sivaneswaran, N. Backcalculation of Flexible Pavement Layer Moduli from Traffic Speed Deflectometer Data. Transp. Res. Rec. 2017, 2641, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannemeyer, L.; Lategan, W.; Mckellar, A. Verification of Traffic Speed Deflectometer Measurements using Instrumented Pavements in South Africa. In Proceedings of the Pavement Evaluation, Blacksburg, VA, USA, 15–18 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Elseifi, M.A.; Zihan, Z.U. Assessment of the Traffic Speed Deflectometer in Louisiana for Pavement Structural Evaluation; Report No. FHWA/LA/.18/590; Louisiana Transportation Research Center: Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 2018.

- ABAQUS 2016 User Subroutines Reference Guide; Dassault Systèmes Simulia Corp.: Providence, RI, USA, 2015.

- Fortran Compiler; Intel Corporation: Santa Clara, CA, USA, 2023.

- ABAQUS Theory Manual: Version 6.11; Dassault Systèmes Simulia Corp.: Providence, RI, USA, 2011.

- Wardle, L. CIRCLY and Mechanistic Pavement Design: The Past, Present and Towards the Future; Mincad Systems: Richmond, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Uzan, J. JULEA (Jacob Uzan Layered Elastic Analysis); Technion University: Haifa, Israel, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Marcondes, J.A.; Snyder, M.B.; Singh, S.P. Predicting Vertical Acceleration in Vehicles through Road Roughness. J. Transp. Eng. 1992, 118, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| i | (s) | E0 (MPa) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10−6 | 0.000802 | 18,403.1 |

| 2 | 10−5 | 0.207389 | |

| 3 | 10−4 | 0.24844 | |

| 4 | 10−3 | 0.246903 | |

| 5 | 10−2 | 0.168632 | |

| 6 | 10−1 | 0.081873 | |

| 7 | 1 | 0.028347 | |

| 8 | 10 | 0.013771 | |

| 9 | 104 | 0.00001 | |

| 10 | 105 | 0.000011 | |

| 11 | 106 | 0.000011 |

| Reference Temperature (°C) | MAPE (%) | (°C) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 3.1 | 17.9 | 133.1 |

| 9 | 3.2 | 17.3 | 137 |

| 13 | 3.1 | 16.8 | 141.2 |

| 17 | 3.2 | 16.4 | 145.2 |

| 21 | 3.1 | 15.9 | 149.2 |

| 25 | 3.4 | 15.5 | 153.2 |

| 29 | 3.2 | 15.1 | 157.2 |

| 33 | 3.2 | 14.8 | 161.3 |

| 37 | 3.3 | 14.4 | 165.3 |

| 41 | 3.2 | 14 | 169 |

| 45 | 3.2 | 13.7 | 172.9 |

| MAPE | Prediction Accuracy |

|---|---|

| <10% | High |

| 10–20% | Good |

| 20–50% | Reasonable |

| >50% | Inaccurate |

| Layer | Thickness (mm) | Modulus (MPa) | Temperature (°C) | Poisson’s Ratio | Density (kg/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC | 100 to 300 | viscoelastic | 5 to 45 | 0.4 | 2300 |

| Base | 300 | 400 | - | 0.35 | 2000 |

| Subgrade | Semi-infinite | 50 | - | 0.45 | 2000 |

| Distance (mm) | AC Thickness (mm) | Regression Equation | MAPE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 100 | TCF = 0.02T * + 0.5891 | 1.2 |

| 200 | TCF = 0.0375T + 0.2805 | 5.2 | |

| 300 | TCF = 0.0574T − 0.046 | 13.2 | |

| 600 | 100 | TCF = 0.0056T + 0.8931 | 0.7 |

| 200 | TCF = 0.0154T + 0.6803 | 0.6 | |

| 300 | TCF = 0.0274T + 0.4552 | 2.3 | |

| 1500 | 100 | TCF = 0.0018T + 0.97 | 0.7 |

| 200 | TCF = 0.0066T + 0.8534 | 0.6 | |

| 300 | TCF = 0.014T + 0.7032 | 0.9 |

| AC Thickness (mm) | Regression Equation | MAPE (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 100 | TCF = −6 × 10−7T2 + 0.0201T * + 0.5888 | 1.2 |

| 200 | TCF = 0.0004T2 + 0.0172T + 0.4691 | 0.9 |

| 300 | TCF = 0.0011T2 + 0.0041T + 0.45 | 1.6 |

| Distance (mm) | AC Thickness (mm) | Regression Equation | MAPE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 100 | STCF = 0.02T * + 0.0013V * + 0.5034 | 1.3 |

| 200 | STCF = 0.038T + 0.0023V + 0.1231 | 5.9 | |

| 300 | STCF = 0.0552T − 3 × 10−5V + 0.027 | 12.6 | |

| 600 | 100 | STCF = 0.0058T + 0.0037V + 0.6725 | 1 |

| 200 | STCF = 0.0158T + 0.0034V + 0.4602 | 1.5 | |

| 300 | STCF = 0.0262T + 0.0016V + 0.3883 | 2.9 | |

| 1500 | 100 | STCF = 0.0019T + 0.0075V + 0.4843 | 2.2 |

| 200 | STCF = 0.0061T + 0.0039V + 0.5948 | 2.4 | |

| 300 | STCF = 0.0132T + 0.0013V + 0.6116 | 2.2 |

| AC Thickness (mm) | Regression Equation | MAPE (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 100 | STCF = 4 × 10−5T2 + 0.0182T * + 0.0013V * + 0.5203 | 1.2 |

| 200 | STCF = 0.0004T2 + 0.0157T + 0.0023V + 0.3307 | 1.7 |

| 300 | STCF = 0.0011T2 + 0.0014T − 3 × 10−5V + 0.5273 | 1.9 |

| Distance (mm) | AC Temperature (°C) | Regression Equation | MAPE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 5 | TCF = −0.0011h * + 0.8039 | 1.7 |

| 25 | TCF = 0.0006h + 1.0333 | 0.4 | |

| 45 | TCF = 0.0064h + 0.8169 | 1.4 | |

| 600 | 5 | TCF = −0.0014h + 1.0512 | 1.7 |

| 25 | TCF = 0.0005h + 0.9683 | 0.4 | |

| 45 | TCF = 0.0027h + 0.846 | 1.6 | |

| 1500 | 5 | TCF = −0.0011h + 1.0991 | 0.5 |

| 25 | TCF = 0.0003h + 0.9722 | 0.4 | |

| 45 | TCF = 0.0013h + 0.9057 | 1.5 |

| Offset Distance (mm) | a | b | c | d | m | n | p | q | MAPE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 (parabolic) | 4 × 10−6 | −3 × 10−5 | 2 × 10−5 | −2.4 × 10−3 | −3 × 10−4 | 0.0184 | −3 × 10−3 | 0.9402 | 3 |

| 100 (linear) | 0 | 2 × 10−4 | −6 × 10−6 | −2.4 × 10−3 | 0 | 0.0036 | 2.7 × 10−3 | 0.672 | 6.5 |

| 600 | 0 | 10−4 | −10−5 | −1.4 × 10−3 | 0 | −0.0048 | 0.005 | 0.7799 | 1.9 |

| 1500 | 0 | 6 × 10−5 | −3 × 10−5 | 6 × 10−4 | 0 | −0.0048 | 0.0103 | 0.4522 | 2.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kazemi, N.; Saleh, M.; Lee, C.-L. Temperature and Speed Corrections for TSD-Measured Deflection Slopes Using 3D Finite Element Simulations. Infrastructures 2025, 10, 351. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10120351

Kazemi N, Saleh M, Lee C-L. Temperature and Speed Corrections for TSD-Measured Deflection Slopes Using 3D Finite Element Simulations. Infrastructures. 2025; 10(12):351. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10120351

Chicago/Turabian StyleKazemi, Nariman, Mofreh Saleh, and Chin-Long Lee. 2025. "Temperature and Speed Corrections for TSD-Measured Deflection Slopes Using 3D Finite Element Simulations" Infrastructures 10, no. 12: 351. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10120351

APA StyleKazemi, N., Saleh, M., & Lee, C.-L. (2025). Temperature and Speed Corrections for TSD-Measured Deflection Slopes Using 3D Finite Element Simulations. Infrastructures, 10(12), 351. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10120351