Abstract

Local scour around pile-group foundations is a predominant cause of hydraulic instability in bridge engineering. This study employs a fully coupled three-dimensional computational fluid dynamics model to investigate local scour around a 2 × 2 inline pile group under steady flows. The model is validated against detailed laboratory measurements of flow and scour, demonstrating good agreement in both hydrodynamic and scour results, with scour depth simulations deviating by less than 15% from experimental data. Analysis of the flow fields reveal that scour evolution is accompanied by the descent of the horseshoe vortex, intensification of gap-flow, and acceleration around the side piles, while migration of bed shear stress from the pile flanks to the upstream slope dictates the equilibrium scour morphology. A systematic parametric study was conducted to evaluate the influence of the Froude number (Fr) and pile spacing (G/D) on scour depth. The results indicate that scour depth increases rapidly with Fr up to approximate 0.35, beyond which it plateaus as form-induced drag dissipates the incoming flow energy. Increasing G/D from 1 to 1.5 reduces the scour depth by about 12%, with smaller further reduction beyond G/D = 1.5, suggesting that this spacing offers a pragmatic compromise between structural footprint and scour resistance.

1. Introduction

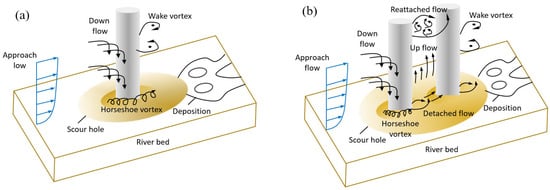

Hydraulic actions have been the leading cause of bridge failures since the 1990s [1]. Wardhana and Hadipriono (2003) [2] pointed out that 55% of the U.S. bridge failures between 1989 and 2000 were hydraulic-related, giving an annual failure frequency of ~1/5000 bridges. A 612% increase in the amount of hydraulic structural damage has been reported since the 1960s, driven by more extreme rainfall and floods linked to climate change [3]. Local scour around bridge foundations remains a significant threat to structural safety, contributing to numerous bridge failures globally and incurring substantial maintenance costs [4]. With the increasing adoption of pile-group foundations in both fluvial and coastal bridge designs (owing to their superior load-bearing capacity and adaptability to complex geological conditions), understanding the scour mechanisms around multiple piles has become imperative. As illustrated in Figure 1, flow patterns around pile groups are considerably more complicated than those around single piers, involving phenomena such as flow contractions, vortex interactions, and wake interference [5,6,7,8], which lead to more complicated scour mechanism. Therefore, a thorough understanding of the interplay between flow characteristics and piles is essential for accurate prediction and mitigation of scour around pile-group foundations. This research is driven by an ongoing engineering programme (Key Technologies for Long-Span Bridges in Complex Reservoir Environments) [9] in which Uchar Bridge is the pivotal structure. With roughly 80% of its piers permanently below the water level, flow-induced pier scour constitutes a primary design constraint that demands accurate assessment and mitigation.

Figure 1.

Sketch of scour mechanisms for (a) single piers and (b) pile groups.

While considerable research has been devoted to local scour at single piers or monopiles [10,11], investigations focusing on multiple-pile foundations remain relatively limited. Existing research on pile-group scour has concentrated largely on identifying equilibrium depth and dissecting how selected governing parameters affect that depth, leading to empirical prediction formulae [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Sumer & Fredsøe (2002) [11] noted that mutual flow interference among neighboring piles produces scour patterns markedly different from those around an isolated pile. To account for this effect, Ataie-Ashtiani & Beheshti (2006) [20] proposed a correction factor for use in monopile-based predictive models. Amini et al. (2012) [21] systematically varied pile spacing, group layout and submergence ratio under steady-current conditions. Lança et al. (2013) [22] examined how scouring time, skew angle and the number of pile columns influence both the resulting scouring evolution and the final scour depth. Through flume tests on single, tandem and side-by-side pile configurations, Liang et al. (2017) [23] evaluated existing predictive equations against their experimental database. Wang et al. (2023) [24] proposed a probabilistic strategy to evaluate scour around bridge deepwater foundations considering a reliability assessment. Yu et al. (2023) [25] performed a flume experiment examining local scour around large-scale pile groups under tidal currents using the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge as prototypes. More recent experimental studies on pile-group scour have been reported, focusing on the parameters of flow, sediment or piles arrangement [26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. Some design guidelines have been proposed based on the aforementioned existing experimental or field studies [16,17].

Most of the aforementioned work has examined how geometric variables—spacing, layout, and skew angle relative to the current—govern scour depth, whereas the role of hydraulic conditions in a fixed configuration has received comparatively little attention. Wang et al. (2016) [33] reported that when piles are sufficiently far apart, mutual interference of turbulent vortices weakens. However, the threshold for this isolation distance was found to be markedly different. Amini et al. (2012) [21] noted separate scour holes for pile spacing (G/D) = 3, while Zhang et al. (2017) [34] found negligible interaction at G/D = 4. These discrepancies likely arise from different flow intensities and sediment conditions used in the respective tests, underscoring the need to explore spacing effects across a broader hydraulic range. As vortex shedding and turbulence interactions among piles evolve with both G/D and inflow velocity, the resulting scour pattern can shift from overlapping individual scour holes to a unified depression [15,35]. Sumer et al. (2005) [36] attributed this behavior to two superimposed mechanisms: local scour at each pile and general bed-lowering over the entire group footprint. Kim et al. (2015) [37] further demonstrated that coherent structures, such as horseshoe vortices, gap jets and wake vortices, migrate and merge as spacing decreases, generating distinct turbulent kinetic energy patterns that lead to markedly different scour morphologies. Thus, the combined influence of pile spacing and flow conditions on scour around pile groups remains inadequately quantified and warrants systematic investigation. Yang et al. (2020) [38] experimentally investigated the influence of pile-group arrangement and found that unlike a pure tandem pair, the 2 × 2 inline arrangement generates three-dimensional corner vortices that wrap around the outermost piles. In fact, practical bridge pile groups are typically installed with small spacing (e.g., G/D = 1–2) for structural economy and cap efficiency, which deserves to be further investigated.

Parallel to experimental studies, numerical modeling has emerged as a powerful tool for investigating scour processes. Computational fluids dynamics (CFD) models coupled with sediment transport modules have been successfully applied to simulate scour around single piles and pile groups [39,40,41]. For example, Baykal et al. (2015) [42] used a CFD model to simulate scour and backfilling around a monopile under waves and currents, underscoring the role of suspended sediment transport. Yang et al. (2024) [43] extended this approach to complex piers with caps and pile groups, demonstrating the sensitivity of scour depth to pile spacing and Froude number. Using large-eddy simulation coupled with sediment transport, Kim et al. (2014) [44] explored scour development between two neighboring cylinders in side-by-side and tandem arrangements, highlighting how vortex dynamics and bed morphology vary with pile spacing. Despite these advancements, several knowledge gaps persist. Most numerical studies have focused on single or twin piles, with high-fidelity, fully coupled hydro-morphodynamic simulations of larger pile groups (e.g., 2 × 2 or more) remaining scarce. Moreover, detailed analyses of the relationships among vorticity dynamics, bed shear stress, and scour evolution are still lacking. Consequently, current design practices often employ oversimplified group factors applied to monopile equations, which fail to capture the nonlinear interactions between flow intensity and pile spacing.

To address these limitations, this study conducts fully coupled three-dimensional numerical simulations of local scour around a 2 × 2 inline pile group under steady flow conditions. Using a validated CFD model, we investigate the scour evolution across a range of Froude numbers and pile spacing ratios. The objectives are twofold: (1) to elucidate the hydro-morphodynamic feedback mechanisms governing scour development; (2) to quantify the effects of key parameters on scour depth. The findings aim to enhance the predictive accuracy of scour depth in pile-group foundations and contribute to more resilient bridge infrastructure design.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the mathematical framework, including the hydrodynamic solver, turbulence closure and sediment transport model. Section 3 provides a validation against experimental flume data. Section 4 details the scour evolution around the pile group. Section 5 analyzes the flow fields during scouring to illustrate the underlying mechanisms. Section 6 presents a parametric study on the effects of pile spacing and Froude number. Finally, the key findings are summarized in Section 7.

2. Methodology

2.1. Governing Equations and Turbulence Closure

In this study, the incompressible and unsteady flow field is simulated using the Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) equations, coupled with the k–ω turbulence model as implemented in FLOW-3D v11.2.0. The continuity and momentum equations are expressed as follows:

where ui and uj denote the time-averaged velocity components, ρ is the fluid density, p represents pressure, ν is the kinematic viscosity, σT is the surface tension coefficient, κγ is the surface curvature, and τij is the Reynolds stress tensor, modeled using the Boussinesq approximation:

Here, νT is the eddy viscosity, is the turbulent kinetic energy, and δij is the Kronecker delta.

The k–ω model proposed by Wilcox (2006) [45] is employed to close the RANS equations. The transport equations for turbulent kinetic energy k and specific dissipation rate ω are given by the following:

The model constants are set as follows: Clim = 7/8, α = 0.52, β = 0.078, β* = 0.09, σ = 0.5, σ* = 0.6 and σdo = 0.125. A wall-damping function is activated to ensure accurate resolution of near-bed turbulence.

2.2. Sediment Transport and Morphodynamic Modeling

Sediment movement is considered in two modes: bed-load and suspended-load transport. The bed-load sediment flux qb is calculated using the empirical formula proposed by Van Rijn (1984) [46]:

where s = ρs/ρ is the specific gravity of sediment, d50 is the median grain size, is the Shields parameter, and d* is the dimensionless grain size:

The critical Shields parameter θc is determined using the Soulsby and Whitehouse (1997) correlation [47]:

For suspended sediment transport, the volumetric concentration c is governed by the advection-diffusion equation:

where ws is the settling velocity of sediment.

The temporal evolution of the bed surface zb is modeled using the Exner equation:

Here, n = 0.4 is the bed porosity, and Es and Ds represent the entrainment and deposition rates of suspended sediment, respectively. A sand-sliding algorithm is applied locally to maintain the bed slope below the angle of repose. It is worth noting that while FLOW-3D is indeed a commercial package, the novelty of our work lies not in developing or modifying the code itself but in applying this well-validated CFD tool to the still-controversial problem of pile-group scour. The built-in sediment-transport module provides a framework, yet some key parameters and the nested mesh refinement were still required to be calibrated against the flume data of Yang et al. (2020) [38] following the procedure we documented in our previous study [40,41]. Thus, the contribution of this study is the physics-based, experimentally validated workflow for quantifying vorticity–morphodynamics feedback in closely spaced pile groups, rather than software development.

3. Numerical Model Setup and Validation

3.1. Computational Domain and Boundary Conditions

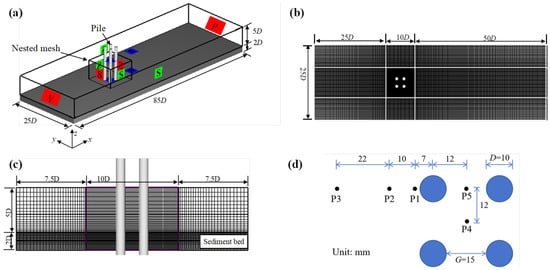

Prior to parametric analysis, the numerical model was validated by replicating the benchmark experiments conducted by Yang et al. (2020) [38]. The physical setup comprised a 10 m × 3 m recirculating flume with a smooth circular cylinder (diameter D = 0.01 m) mounted 5 m downstream of the inlet. Table 1 lists the test conditions, with a uniform approach flow depth H = 0.05 m, depth-averaged velocity U0 = 0.233 m/s, Reynolds number Re = U0D/ν = 11,566 and a Froude number Fr = U0/(gh)0.5 = 0.333. A three-dimensional numerical domain mirroring this configuration was constructed to simulate the coupled hydrodynamic and morphodynamic response of the pile group under steady flows. As shown in Figure 2, the computational domain was designed based on the physical flume dimensions used in the validation experiments, with a length of 85D, width of 25D, and still water depth of 5D, where D is the pile diameter. The sediment bed thickness was set to 2D, consistent with the maximum scour depth observed in the experiments. Boundary conditions were defined as follows: Inlet: velocity inlet with a fully developed turbulent velocity profile; Outlet: pressure outlet with zero-gradient condition; Bottom: no-slip wall with a wall function to solve the boundary layer; Sides and top: symmetry boundaries to minimize wall effects.

Table 1.

Experimental conditions for numerical model validation.

Figure 2.

Numerical setup: (a) computational domain and boundary conditions; (b) top view of the global mesh; (c) side view of the refined mesh around piles; (d) position of the measurement point for velocity.

It is worth noting that the computational domain is a full-scale replica of the experimental flume used by Yang et al. (2020) [38], with no geometric distortion (model: prototype = 1:1). The water depth and bulk velocity were directly adopted from the experiment. The Reynolds number (Re = 11,566) and Froude number (Fr = 0.333) match the experimental values listed in Table 1. A logarithmic velocity profile measured in the experiment was imposed at the inlet boundary. No artificial turbulence seeding was required, as the turbulence model naturally develops the boundary layer. The sand-bed roughness height was set to ks = 2.5d50 = 0.15 mm, consistent with the median sediment size used in the experiment. No scaling or tuning coefficients were applied. All fluid and sediment properties were identical to those reported in Yang et al. (2020) [38].

A nested mesh strategy was employed to enhance local resolution around the pile group. The inner mesh region (10D × 10D in plan view) encompassed the piles and the surrounding sediment bed, with a grid refinement ratio of 1:2 in the horizontal directions and 1:1 in the vertical direction. The outer mesh consisted of 280 × 100 × 17 cells in the streamwise, transverse, and vertical directions, respectively, while the inner mesh contained 100 × 100 × 17 cells. Grid independence was verified by testing coarse, medium, and fine resolutions. The medium mesh (total 627,130 cells) was selected for all subsequent simulations as it provided an optimal balance between computational accuracy and cost.

The simulation was not initialized from still water conditions. Instead, the following two-step procedure was adopted: (i) a statistically steady, fully turbulent velocity field was first developed over the flat, immobile bed for 20 s by running the CFD solver with the sediment transport module deactivated; (ii) at t = 0 s the bed was released (sediment transport activated) while the flow continued to evolve.

3.2. Hydrodynamic Validation

The flow field was validated using acoustic Doppler velocimetry (ADV) data obtained from the physical experiments. Velocity profiles were measured along four vertical lines (P1–P4 in Figure 2d) upstream and around the pile group under clear-water scour conditions. Measurements were taken at a sampling frequency of 200 Hz, with a sampling duration of two minutes per point to ensure statistically stable time-averaged velocities.

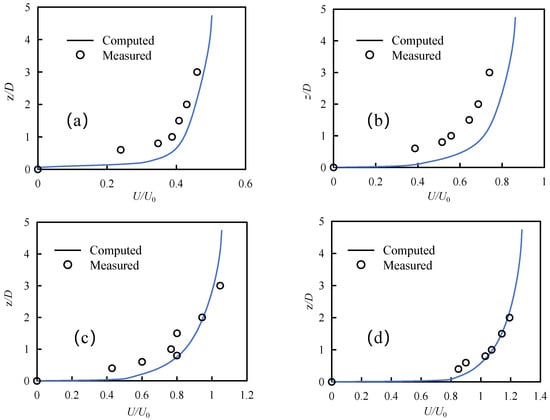

Figure 3 compares the simulated and measured normalized velocity profiles (U/U0) at different relative depths (z/D). The results show good agreement in both magnitude and distribution, confirming the model’s capability to reproduce the key flow features, including velocity reduction in front of the leading pile, flow acceleration along the pile sides, and wake recirculation and vortex shedding in the gap region. Minor discrepancies observed near the bed are likely due to differences in bed roughness representation between the numerical model (fixed roughness height) and the experiment (mobile sand bed with possible localized armoring). Overall, the model accurately captures the spatial distribution of streamwise velocities and the extent of flow disturbance caused by the pile group.

Figure 3.

Comparison of simulated and experimental flow velocity profiles at different vertical lines: (a–d) P1–P4.

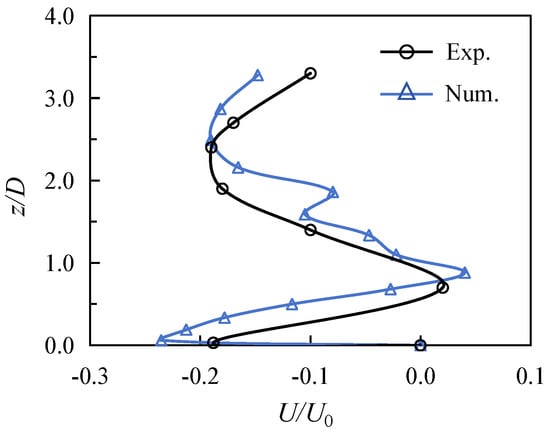

In addition to point-wise velocity profiles, the spatial distribution of flow velocity within the gap between piles was analyzed using Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) measurements. Figure 4 presents a comparison of the simulated and measured streamwise velocity components along a horizontal transect across the mid-gap between the front and rear piles. The velocity profile was measured at point P5 shown in Figure 2d. The numerical results agree well with the experimental data, accurately capturing the flow reversal and the reduced velocity magnitude within the sheltered region behind the front piles. This further validates the model’s capability to resolve the complex flow interactions within pile groups, which are critical for accurate scour prediction.

Figure 4.

Comparison of velocity in the gap region (P5) of pile group between numerical and experimental results.

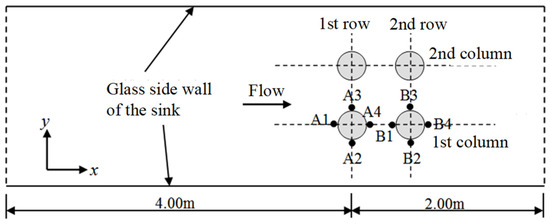

3.3. Scour Validation

Scour validation was performed by comparing the simulated bed evolution with experimental measurements at eight monitoring points around the pile group. As shown in Figure 5, points A1–A4 are located around the front row and points B1–B4 are located around the back row. The simulations were run for 300 s of physical time, representing the early stage of the scouring process. Normalized scour depth (S/D) was used to quantify the comparison.

Figure 5.

Locations of the eight points for scour monitoring around piles.

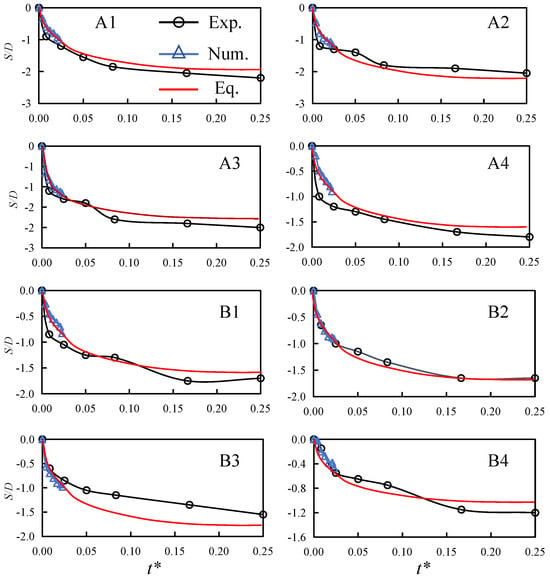

As shown in Figure 6, the numerical model satisfactorily reproduces the temporal development of scour depth at all monitoring points, with relative errors generally within 15%. The time is normalized as t* = t/Ts, where Ts is the densimetric time scale (∫(Se − Ss)/Se dt) obtained from the experiments of Yang et al. (2020) [38]. The model correctly predicts deeper scour at the front piles compared to the rear ones, with the larger scour occurring on the inner side of the pile group due to flow contraction. The curve also shows faster scour development during the initial stage (t* < 0.025). The minor under-estimation is attributed to (i) the short simulation interval and (ii) the fixed roughness height used in the CFD, whereas the experiment developed small ripples that increases the effective bed roughness. Nonetheless, the model captures the essential scour patterns and their spatial variability, validating its suitability for subsequent parametric analyses.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the temporal development of scour depth between numerical and experimental results at different positions around the pile group.

It should be noted that, due to the high computational cost of the coupled CFD-morphodynamic solver, the simulation interval (300 s) corresponds to only the initial stage of the 240 min laboratory test. Under clear-water conditions, approximately 70% of the ultimate scour depth is attained within this initial phase [38,48]. Consequently, the comparison provides a stringent benchmark for the model’s ability to reproduce the correct initial scour rate and spatial pattern but it does not constitute validation of the final equilibrium depth. The generally good agreement (relative error < 15%) confirms that the numerical framework captures the dominant hydro-morphodynamic processes without simulating the prohibitively long equilibrium phase. The model reproduces the early spatial differentiation of the scour morphology around the pile group, which supports its suitability for parametric trend analysis, without implying that the ultimate scour pattern is already fully formed. This 300 s interval corresponds to approximately 10% of the equilibrium time and captures ≈ 70% of the final scour depth measured by Yang et al. (2020) [38] and predicted by BenMeftah and Mossa (2020) [48], providing a stringent benchmark for the initial scour rate without implying that equilibrium has been reached.

Although the CFD simulation was limited to the first 300 s, the final scour depths used in the subsequent analysis were predicted based on the initial simulation data. For every simulated case, the temporal point was extended to the equilibrium scour depth based on the empirical pile-group scour evolution equation proposed by Yang et al. (2020) [38]:

where c1 and c2 are fitting coefficients which can be obtained by the present simulation data. The red solid line in Figure 6 represents the fit of Equation (13) to the present test data, demonstrating good agreement between the experimental and equation-predicted results. Applying this procedure converts each short-term simulation result into a statistically sound estimate of the final scour depth without assuming geometrical similarity or proportional scaling.

The validated numerical model successfully reproduces both the hydrodynamic and scour characteristics of local scour around pile groups under steady flow conditions. The adopted mesh resolution, turbulence closure, and sediment transport schemes are deemed appropriate for investigating the influence of flow conditions and pile configurations on scour development.

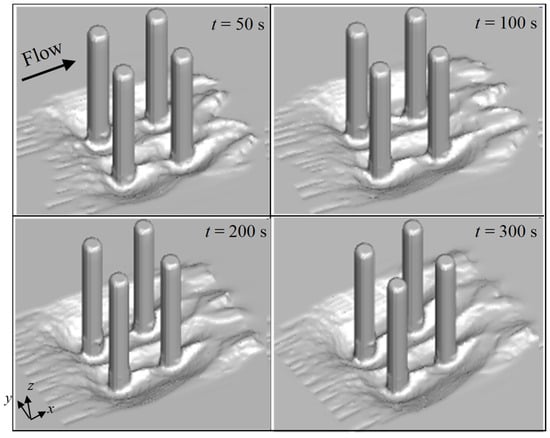

4. Scour Hole Evolution Around Pile Group

To quantify the morphodynamic response of the sediment bed, the temporal evolution of the scour hole was extracted from the aforementioned validation case at six representative instants: t = 50, 100, 150, 200, 250 and 300 s. Figure 7 presents the three-dimensional iso-surface of net bed elevation change during the first 300 s of the scouring process. Within the initial 50 s, scour primarily concentrates at the lateral flanks of the front-row piles (approximately ±45° relative to the approach flow direction), where bed shear stress is amplified by the contracting streamlines. A deposition dune immediately emerges in the lee of the pile group, indicating rapid sediment redistribution driven by the horseshoe-vortex system and the subsequent wake vortex street.

Figure 7.

Local scour hole evolution around the pile group.

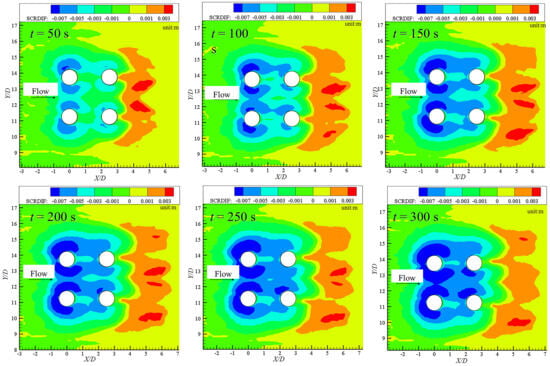

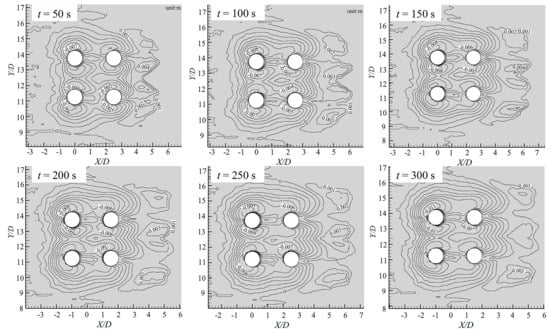

As scouring progressed, the individual separate scour holes begin to coalesce, forming a continuous trough that extends around the upstream half of the front row (Figure 8). The location of the maximum scour depth migrates from the pile sides toward the geometric center-line, following the trajectory of the primary horseshoe vortex. Meanwhile, the deposition ridge downstream migrates rearward and increases in height, reaching approximately 0.3 cm at t = 300 s. Owing to the sheltering effect of the front piles, the back row initially experiences milder scour; however, after t ≈ 150 s, the gap flow accelerates and the rear piles begin to develop their own pronounced scour holes. The resultant bed morphology exhibits a “bow-shaped” scour pattern upstream and a “tail-shaped” deposition lobe downstream, consistent with previous experimental observations for tandem piers.

Figure 8.

Bed morphology contour around the pile group at different times during the scouring process.

Figure 9 shows the contour maps of bed elevation, which further reveals that the scour hole is not perfectly symmetric about the streamwise center-line. Minor deviations (approximately 5% of D) are attributed to the staggered arrangement and to low-frequency oscillations of the horseshoe vortex. The lateral extent of the scour hole at t = 300 s is approximately 3.5D and 2.8D for the front and back rows, respectively, while the longitudinal extent reaches 5D from the leading pile edge. These dimensions are in line with empirical predictors for pile groups at comparable G/D and Fr conditions, lending additional confidence to the morphodynamic module.

Figure 9.

Bed elevation distribution around the pile group at different times during the scouring process.

Overall, the simulated morphological sequence captures the three key phases observed in the laboratory: (i) initial scour formation at pile shoulders, (ii) lateral merger into a global scour hole, and (iii) downstream dune development. This agreement is essential for the subsequent analysis of flow-sediment feedback mechanisms discussed in Section 5.

5. Flow Characteristics During Scouring Process

To elucidate the hydro-morphodynamic coupling that drives the evolving scour geometry, high-resolution three-component velocity, vorticity and bed-shear-stress fields were extracted at the representative instants introduced in Section 4.

5.1. Velocity Field

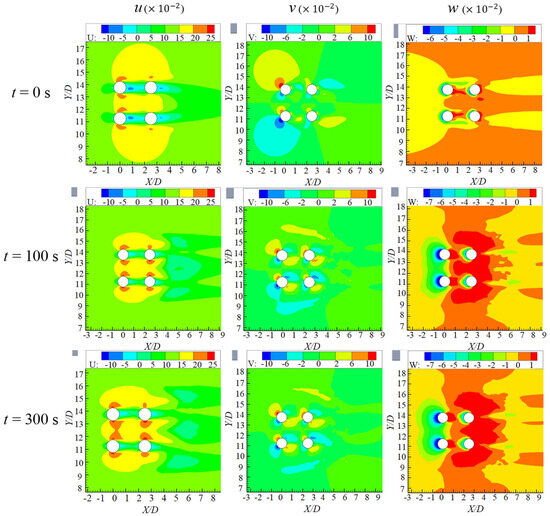

Time-averaged velocity fields on a horizontal plane 2 mm above the initial bed were extracted at t = 0, 100 and 300 s to clarify the hydrodynamic drivers of scour initiation and development. Figure 10 presents the streamwise (u), transverse (v) and vertical (w) components of velocity.

Figure 10.

Velocity fields around the pile group at different times during scouring process.

At the flat-bed stage (t = 0 s), the approaching boundary layer is pinched between the front piles, producing an accelerated flow ribbon reaching 1.35U0 along their ±75° flanks. Simultaneously a narrow reverse-flow pocket forms immediately downstream and a weak gap jet initiates through the inter-pile space. Down-welling at the pile nose supplies the nascent horseshoe vortex. Once the upstream scour hole has deepened to approximate 0.7 cm (t = 100 s), the high-velocity core is lifted slightly above the depression, with the peak velocity shifting to the shoulder of the scour slope and exceeding 1.4U0. The wake behind the front row extends by approximately 1.5D, and the accelerated gap flow increases shear stress on the rear piles. By t = 300 s, the core of maximum streamwise velocity is located within the trough, confirming that the sloping face sustains above-critical shear stress even as the scour rate decreases. A coherent jet emerges through the gap, impinges on the downstream slope of the rear pile and carves a secondary scour lobe. Transverse velocity fluctuations reflect unsteady wake flapping, while vertical velocities organize into two persistent cells, including down-welling on the upstream slope and up-welling over the downstream dune, creating a closed sediment loop that limits further scour.

The spatial correspondence between these velocity patterns and the observed bedforms underlines that flow acceleration along the pile sides initiates scour, vortex-core migration drives deepening, and eventual energy dissipation by form drag determines the equilibrium depth.

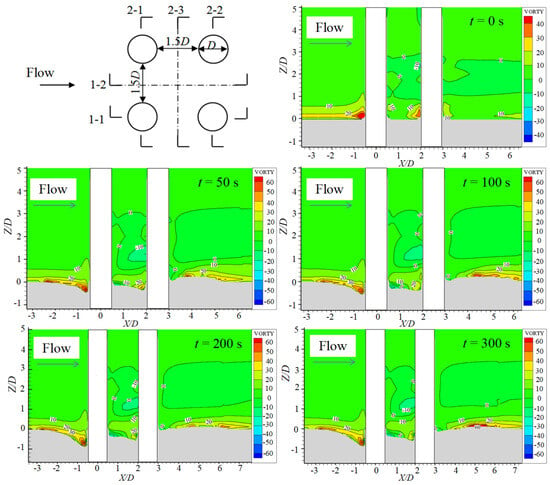

5.2. Vorticity Field

Figure 11 shows the temporal evolution of the y-component vorticity on the vertical symmetry plane that cuts through the center-line of both pile rows (Section 1-1). At t = 0 s, a single high-intensity vorticity core is anchored to the upstream bed junction of the front pile, marking the classical horseshoe vortex. As the scour hole deepens (t = 50–100 s), this core splits, specifically demonstrating that the primary filament descends along the developing slope, while a secondary lobe remains near the lip of the scour hole. The peak vorticity magnitude inside the primary core remains largely constant, but the affected area expands to roughly 3D downstream, indicating that an enlarged recirculation zone continuously sweeps sediment out of the hole. By t = 300 s, the vorticity field has reached a quasi-steady state. The lower core settles within the trough, the upper core adheres to the slope shoulder, and a weaker counter-rotating cell appears behind the rear pile, supplying the uplift that feeds the downstream dune. The persistence of strong vorticity along the scour perimeter explains the sustained sediment transport capacity even as the scour rate declines.

Figure 11.

The y-direction vorticity distribution contour on section 1-1 at different times during the scouring process.

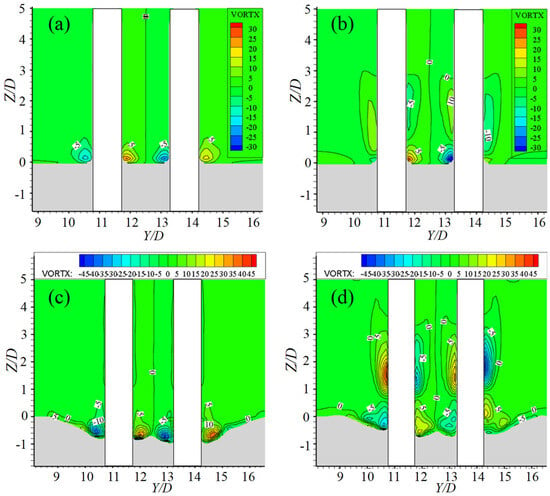

Figure 12 illustrates the variability of vortical structures around side-by-side piles on Sections 2-1 (front row) and 2-2 (rear row). At t = 0 s, both sections show the typical kidney-shaped pattern, and the positive and negative vorticity lobes wrap around each pile. As scour develops (t = 300 s), the vorticity at the front-row intensifies and the cores shift downward into the newly formed scour slope, indicating that the pressure-driven vortex now follows the local bathymetry rather than the original bed. In contrast, the rear-row vorticity cores weaken slightly but broaden laterally, consistent with the gap-flow jet impinging on the downstream slope and generating a wider, weaker vortex sheet. The difference between the two rows underscores the sheltering effect, and the front piles harvest most of the approach-flow vorticity, leaving a diminished, but still erosive, field for the rear piles.

Figure 12.

The x-direction vorticity distribution contour: (a) Section 2-1 at 0 s; (b) Section 2-2 at 0 s; (c) Section 2-1 at 300 s; (d) Section 2-2 at 300 s.

Collectively, these results demonstrate that the scour hole does not simply passively accommodate the horseshoe vortex. Instead, its evolving geometry actively steers and intensifies vorticity along the slope, thereby maintaining the sediment entrainment capacity until energy dissipation by form drag balances the incoming kinetic energy.

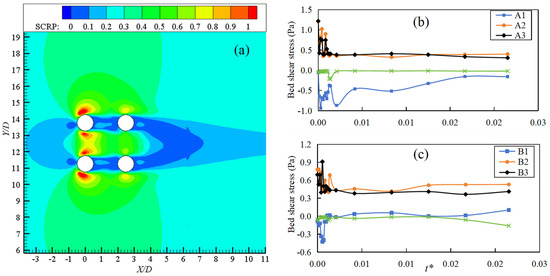

5.3. Bed Shear Stress

The spatial and temporal evolution of bed shear stress is examined to identify zones of active sediment mobility and link flow structures with scour patterns. At the flat-bed stage (t = 0 s), Figure 13a exhibits two pronounced arcs of high shear stress wrapping around the front piles at ±45°, coinciding with the footprint of the horseshoe vortex detected in Figure 10. A secondary and weaker stripe appears along the gap center-line, foreshadowing the later incision between the rows. Outside these zones, bed shear stress falls below the critical threshold, indicating clear-water scour conditions.

Figure 13.

Bed shear stress: (a) spatial contour at initial scour stage; (b) temporal variation at different positions in front of pile; (c) temporal variation at different positions behind pile.

Temporal variations extracted at the eight monitoring points (Figure 13b,c) reveal a consistent pattern, that is, an initial spike within the first 20 s, followed by a rapid decay as the scour hole deepens and the local slope increases. Front-row points (A1–A4) consistently exhibit higher magnitudes than their rear-row counterparts (B1–B4), reflecting the sheltering effect already noted in the velocity and vorticity fields. The largest initial stress occurs at A2 (pile-side), rather than A1 (pile-front), confirming that side-pile acceleration, not frontal stagnation pressure, initiates sediment motion. Negative values at A1 indicate flow reversal associated with the descending limb of the horseshoe vortex. Although brief, these excursions contribute to bed loosening and are quickly followed by outward transport along the scour floor.

At the late stage, the stresses approach quasi-equilibrium. The front-row values stabilize around 0.5 Pa (still 20% above sediment critical value), sufficient to maintain the observed slow bottom creep, while rear-row values drop to 0.3 Pa, below the motion threshold, explaining the reduced scouring rate at B1-B4 after 200 s. The gradual spatial expansion of the high-stress zone mirrors the outward migration of the scour slope, indicating that the bed adjusts its shape to keep the integrated shear force in balance with the submerged weight of the sliding sediment. Overall, the bed shear stress analysis corroborates the findings from the velocity and vorticity field, that is, side-pile acceleration triggers incision, vortex descent sustains deepening, and eventual stress reduction through slope adjustment leads to equilibrium.

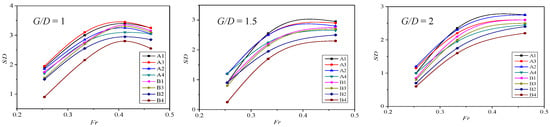

6. Influence of Key Parameters on Scour Depth

Based on the validated model, a parametric study was conducted to isolate the influence of flow intensity and pile spacing on the scour depth, with a focus on the Froude number (Fr) and pile spacing ratio (G/D). As shown in Table 2, the simulations cover a Froude number range of Fr = 0.25–0.46 and gap-to-diameter ratios of G/D = 1, 1.5 and 2. The following sections summarize the principal trends.

Table 2.

Flow conditions used for parametric analysis.

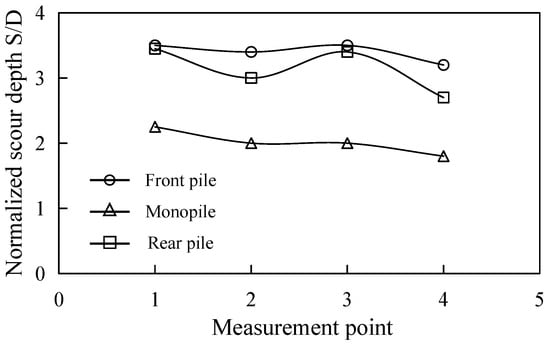

6.1. Comparison with Monopile

Before evaluating group effects, a single isolated pile (monopile) was simulated under the same hydraulic conditions that will later be applied to the pile group (Fr = 0.41, H = 0.05 m, U0 = 0.289 m/s). Figure 14 compares the equilibrium scour depth at four equally spaced locations around the monopile with the corresponding positions in the 2 × 2 inline group (G/D = 1). The monopile exhibits the expected axisymmetric scour pattern, with a nearly uniform normalized scour depth (S/D) around its circumference, confirming spatial uniformity of the approach flow and sediment properties. In contrast, the pile-group case displays significant spatial variability. The front-row positions (Points 1 and 2) reach scour depths of 3.5D and 3.3D, respectively, i.e., approximately 55% greater than the monopile reference. The rear-row counterparts (Points 3 and 4) attain shallower scour depths of 2.6D and 2.1D, with the latter being slightly less than the monopile scour depth. The deeper scour on the inner faces of both rows (Points 2 and 3) reflect enhanced flow contraction through the piles gap, whereas the outer face of the rear pile (Points 4) lies within the wake of the front row and consequently experiences lower approach velocities and reduced scour. Overall, it quantitatively demonstrates that the 2 × 2 inline group generates a spatially variable scour envelope whose maximum scour depth can exceed that of the monopile reference by more than 50%. This amplification should be accounted for in foundation design and scour protection if the traditional monopile-based prediction is used without modification.

Figure 14.

Comparison of scour depth with monopile at different measured points.

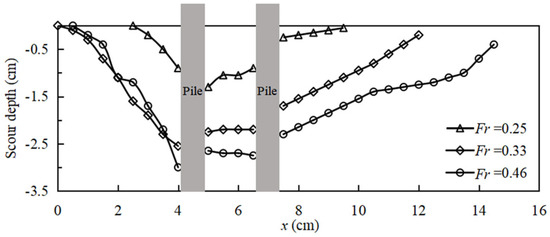

6.2. Effect of Froude Number

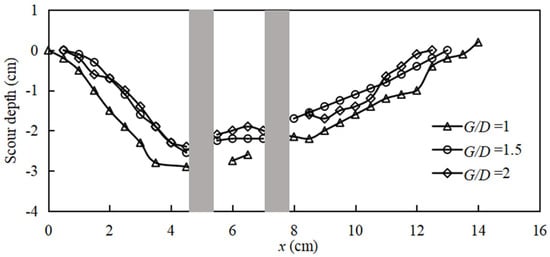

To isolate the influence of Froude number, the 2 × 2 inline group (G/D = 1.5) was subjected to four steady currents with identical water depth (H = 0.05 m) but increasing bulk velocity, yielding Fr = 0.25, 0.33, 0.41 and 0.46. Figure 15 shows the longitudinal bed profiles along the group center-line. It clearly exhibits a monotonic deepening of the upstream scour hole as Fr rises, specifically as the trough shifts from 2.3D at Fr = 0.25 to 3.6D at Fr = 0.46, while the downstream dune grows commensurately in height and extent. The slope angle of the scour hole remains nearly constant at approximately 33°, indicating that the bed morphology is governed by the repose angle of sediment once sufficient flow energy is available for transport.

Figure 15.

Scoured bed profile on Section 1-1 under different flow conditions.

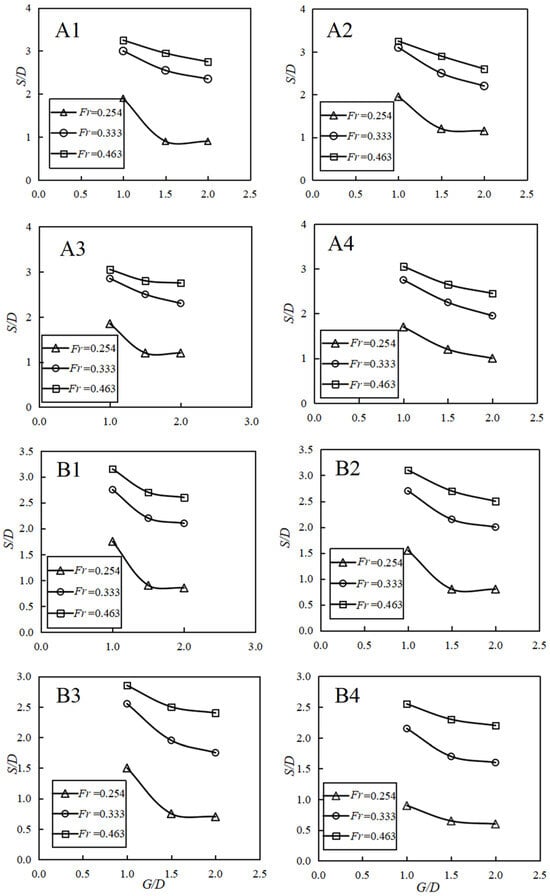

Figure 16 shows the point-wise scour depths extracted at the eight monitoring points. It reveals a rapid increase between Fr = 0.25 and 0.35, followed by a pronounced plateau. The maximum scour depth at the front row rises from 2.9D to 3.6D in the lower Fr range but increases by only 0.1D as Fr rises from 0.41 to 0.46. The rear-row values follow a similar trend, stabilizing near 2.7D for Fr > 0.35. This asymptotic behavior is attributed to the growing dominance of form drag on the enlarged scour hole. As the trough deepens, an increasing fraction of the flow kinetic energy is dissipated by pressure work on the scour slope, reducing the energy available for further sediment transport. For design practice, these results suggest that linear extrapolation of scour depth with velocity may be overly conservative for Fr values exceeding approximately 0.35. In the present clear-water regime, a 30% increase in velocity (corresponding to Fr increasing from 0.33 to 0.46) yields only a 3% increase in maximum scour depth, implying that site-specific upper-bound Fr estimates could be used to cap scour predictions for extreme discharge events. The form-drag work (Wf) and the bed-shear power (Pb) were extracted from the CFD results using the following relationships:

where p and τb represent the pressure and bed-shear stress on the pile. Between Fr = 0.33 and 0.46 the normalized quantities evolve as ΔWf/(0.5ρU03D2) = +28% and ΔPb/(0.5ρU03D2) = +3%. Consequently, the fraction of incoming kinetic energy dissipated by form drag rises from 0.42 to 0.54, while the fraction used for sediment transport (proportional to Pb) remains nearly constant. This redistribution explains why the scour depth increment drops to 3% even though the bulk velocity increases by 30%. The dimensionless scour sensitivity Δ(S/D)/ΔFr decreases from 0.18 (Fr = 0.25–0.35) to 0.02 (Fr = 0.35–0.46), confirming the asymptotic behavior.

Wf = ∫∫ p u · n dA

Pb = ∫ τb |ub| dA

Figure 16.

Effects of Froude number on scour depth under different pile spacing conditions.

6.3. Effect of Pile Spacing

The influence of pile spacing was investigated for a fixed Froude number (Fr = 0.33) and group layout (2 × 2 inline), with G/D varied from 1 to 2 in increments of 0.5. Figure 17 presents the resulting equilibrium bed profiles along the center-line. As G/D increases, the upstream scour hole becomes progressively shallower and narrower. The maximum scour depth decreases from 3.5D at G/D = 1 to 2.8D at G/D = 2, while the scour half-width contracts from 1.9D to 1.3D. The downstream dune also diminishes in height and length, indicating a weakening of the entire sediment redistribution system as pile interaction decreases.

Figure 17.

Scoured bed profile on the Section 1-1 under different pile spacing conditions.

Figure 18 shows the point-wise scour depths for all monitoring points. The front-row scour depth decreases nearly linearly as the spacing increases from G/D = 1 to 1.5, followed by a more gradual reduction beyond G/D = 1.5. Rear-row points behave similarly but stabilize earlier, essentially reaching the monopile reference depth (2.2D) at G/D = 2. These trends reflect the decay of hydrodynamic interference between piles. At G/D = 1, the horseshoe vortices generated by adjacent piles overlap, creating a single, deeper trough, whereas at G/D = 2 the vortex cores are sufficiently separated to develop independently. From a design perspective, the results indicate diminishing returns once G/D exceeds 1.5. Increasing the pile spacing from 1D to 1.5D reduces the global scour depth by about 12%, whereas a further increase to 2D yields only an additional 4% reduction. Therefore, a spacing of 1.5D offers a practical balance between geotechnical requirements (a larger pile cap for the same number of piles) and hydraulic performance (significant scour reduction) without excessively increasing the foundation footprint.

Figure 18.

Effects of pile spacing on the scour depth at different measured points.

7. Conclusions

This study presents a fully coupled 3D CFD investigation that quantifies the competing corner-vortex and wake-interference effects for closely spaced 2 × 2 inline pile groups, a configuration common in bridges foundations but still lacking high-resolution, process-based evidence. We proposed a validated, mesh-adaptive modeling protocol that reduces CPU cost while predicting equilibrium scour depth within the limited flume data, identifying the influence of key parameters, and providing dimensionless curves that quantify the variation in equilibrium scour depth with Fr and G/D for 2 × 2 inline pile groups, providing engineers with a ready-to-use design reference. The principal findings are summarized below:

- (1)

- The validated numerical model accurately reproduces the key hydro-morphodynamic processes, including flow acceleration around the side piles, descent of the horseshoe vortex, intensification of gap flow, and the formation of a downstream depositional dune. The simulated scour depths agree well with laboratory data, with relative errors generally within 15%. In engineering practice, long-term morphodynamic simulations or empirical time-scale methods are still necessary to estimate equilibrium scour depth.

- (2)

- Analysis of the flow field demonstrates that the scour morphology is governed by a dynamic feedback mechanism. The core of the horseshoe vortex migrates from the pile sides into the developing scour slope, sustaining high bed shear stress along the perimeter of the trough. Scour progression ceases as the slope approaches the repose angle of sediment, leading to stress decay and the establishment of a closed sediment recirculation loop that defines the equilibrium state.

- (3)

- Increasing Fr from 0.25 to 0.35 deepens the scour depth rapidly, while beyond Fr = 0.35, the growth rate diminishes, becoming nearly asymptotic. This transition is attributed to the increasing dissipation of incoming flow energy by form drag on the enlarged scour hole. A 30% increase in Fr from 0.33 to 0.46 yields only a 3% increase in scour depth, implying that linear extrapolation with velocity may be overly conservative at high Fr.

- (4)

- Increasing G/D from 1 to 2 leads to a quasi-linear reduction in scour depth up to G/D = 1.5, beyond which the mitigating effect plateaus. The benefit of increasing the spacing beyond 1.5D is marginal (<4% additional reduction), indicating that this threshold represents a pragmatic compromise, balancing hydraulic safety (significant scour reduction) against structural footprint constraints. A true engineering optimum would additionally require explicit evaluation of geotechnical stability, lateral stiffness, construction cost, and other constraints, which is beyond the scope of the present hydraulic study.

Author Contributions

W.L.: Project administration; Funding acquisition; X.W.: Conceptualization; Project administration; Funding acquisition; Writing—original draft; Writing—original draft; Z.W.: Formal analysis; Investigation; Q.Y.: Funding acquisition; Writing—original draft; P.H.: Formal analysis; Investigation; Y.Y.: Methodology; Validation; Visualization; J.L.: Visualization; Writing—review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is financially supported by the Research Project under the 2021 Annual Scientific Research Plan of China Railway Construction Corporation Limited (Project Nos. 2021-C01, ZT-2020A01) and the Youth Science and Technology Leaders Training Program Project of Jiangxi Bureau of Geology (No. 2022JXDZKJRC07).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Wentao Li, Xiangdong Wang, Zhixun Wang, Qianmi Yu and Peng Huang were employed by the company China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation and Ningbo East China Nuclear Industry Survey and Design Institute Group Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Xiong, W.; Cai, C.S.; Zhang, R.; Shi, H.; Xu, C. Review of hydraulic bridge failures: Historical statistic analysis, failure modes, and prediction methods. J. Bridge Eng. 2023, 28, 03123001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardhana, K.; Hadipriono, F.C. Analysis of recent bridge failures in the United States. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2003, 173, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, A.; Björnsson, I.; Honfi, D.; Larsson Ivanov, O.; Johansson, J.; Kjellström, E. A review of the potential impacts of climate change on the safety and performance of bridges. Sustain. Resilient Infrastruct. 2021, 6, 192–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettema, R.; Gonstantinescu, G.; Melville, B.W. Flow-field complexity and design estimation of pier-scour depth: Sixty years since Laursen and Toch. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2017, 143, 03117006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, D. Two circular cylinders in cross-flow: A review. J. Fluids Struct. 2010, 26, 849–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataie-Ashtiani, B.; Aslani-Kordkandi, A. Flow field around single and tandem piers. Flow Turbul. Combust. 2013, 90, 471–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Qi, M.; Li, J.; Ma, X. Evolution of hydrodynamic characteristics with scour hole developing around a pile group. Water 2018, 10, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, J. Experimental study of flow field around pile groups using PIV. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2021, 120, 110223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, W.; Peng, Z.; Yu, Q.; Yang, Y.; Li, J. Optimization of combined scour protection for bridge piers using computational fluid dynamics. Water 2025, 17, 2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melville, B.W.; Coleman, S.E. Bridge Scour; Water Resources Publication: Highlands Ranch, CO, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sumer, B.M.; Fredsøe, J. The Mechanics of Scour in the Marine Environment; World Scientific: Singapore, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sumer, B.M.; Fredsøe, J. Wave scour around group of vertical piles. J. Waterw. Port Coast. Ocean Eng. 1998, 124, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, A.; Larson, M. Analysis of scour around a group of vertical piles in the field. J. Waterw. Port Coast. Ocean Eng. 2000, 126, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arneson, L.A.; Zevenbergen, L.W.; Lagasse, P.F.; Clopper, P.E. Evaluating Scour at Bridges. In Hydraulic Engineering Circular, 5th ed.; No. 18; Federal Highway Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, D.; Gotoh, H.; Scott, N.; Tang, H. Experimental study of local scour around twin piles in oscillatory flows. J. Waterw. Port Coast. Ocean Eng. 2013, 139, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, M.; Li, J.; Chen, Q. Comparison of existing equations for local scour at bridge piers: Parameter influence and validation. Nat. Hazards 2016, 82, 2089–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, M.; Li, J.; Chen, Q. Applicability analysis of pier-scour equations in the field: Error analysis by rationalizing measurement data. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2018, 144, 04018050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghbadorani, D.A.; Ataie-Ashtiani, B.; Beheshti, A.; Hadjzaman, M.; Jamali, M. Prediction of current-induced local scour around complex piers: Review, revisit, and integration. Coast. Eng. 2018, 133, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Z. Influence of scour development on turbulent flow field in front of a bridge pier. Water 2020, 12, 2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataie-Ashtiani, B.; Beheshti, A.A. Experimental investigation of clear-water local scour at pile groups. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2006, 132, 1100–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, A.; Melville, B.W.; Ali, T.M.; Ghazali, A.H. Clear-water local scour around pile groups in shallow-water flow. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2012, 138, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lança, R.; Fael, C.; Maia, R.; Pêgo, J.P.; Cardoso, A.H. Clear-water scour at pile groups. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2013, 139, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Wang, C.; Huang, M.; Wang, Y. Experimental observations and evaluations of formulae for local scour at pile groups in steady currents. Mar. Georesour. Geotechnol. 2017, 35, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yuan, Y.; Zhu, W.; Wang, C.; Yu, X. A probabilistic strategy to evaluate scour around bridge deepwater foundations considering a reliability assessment. Mar. Georesour. Geotec. 2023, 411, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Chen, J.; Zhou, J.; Li, J.; Yu, L. Experimental investigation of local scour around complex bridge pier of sea-crossing bridge under tidal currents. Ocean Eng. 2023, 290, 116374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Wang, C.; Gong, M.; Zhu, F.; Wu, G.; Liang, B. Local scour around varied-configuration pile groups in silty seabed under steady current: An experimental study. Appl. Ocean Res. 2025, 165, 104819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Wu, G.; Du, S.; Pan, X.; Lv, Y.; Sun, Y.; Ding, G.; Liang, B. Experimental investigations of local scour around piles in a single-column and three-columns with multiple rows in steady current. Appl. Ocean Res. 2025, 159, 104608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Niu, G.; Du, S. Study of local scour around multiple-arranged piles in unidirectional flow. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 075153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrie, A.; Wang, C.; Liang, F.; Qi, W. Experimental investigation on the mechanism of local scour around a cylindrical coastal pile foundation considering sloping bed conditions. Ocean Eng. 2024, 312, 119225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yu, X.; Liang, F. A review of bridge scour: Mechanism, estimation, monitoring and countermeasures. Nat. Hazards 2017, 87, 1881–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wu, Q.; Liang, J.; Liang, F.; Yu, X. Establishment and implementation of an artificial intelligent flume for investigating local scour around underwater foundations. Transp. Geotech. 2024, 49, 101433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yu, X.; Liang, F. Investigation of the protection mechanism and failure modes of solidified soil utilized for scour mitigation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 472, 140858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tang, H.; Xiao, J.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, S. Clear-water local scouring around three piers in a tandem arrangement. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2016, 59, 888–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhou, X.L.; Wang, J.H. Numerical investigation of local scour around three adjacent piles with different arrangements under current. Ocean Eng. 2017, 142, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaghefi, M.; Motlagh, M.J.T.N.; Hashemi, S.S.; Moradi, S. Experimental study of bed topography variations due to placement of a triad series of vertical piers at different positions in a 180° bend. Arab. J. Geosci. 2018, 11, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumer, B.M.; Bundgaard, K.; Fredsøe, J. Global and local scour at pile groups. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth International Offshore and Polar Engineering Conference, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 19 June 2005; International Society of Offshore and Polar Engineers: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.S.; Nabi, M.; Kimura, I.; Shimizu, Y. Computational modeling of flow and morphodynamics through rigid-emergent vegetation. Adv. Water Resour. 2015, 84, 64–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Qi, M.; Wang, X.; Li, J. Experimental study of scour around pile groups in steady flows. Ocean Eng. 2020, 195, 106651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Fuhrman, D.R.; Kong, X.; Xie, M.; Yang, Y. Three-dimensional numerical simulation of wave-induced scour around a pile on a sloping beach. Ocean Eng. 2021, 233, 109174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Kong, X.; Yang, Y.; Deng, L.; Xiong, W. CFD investigations of tsunami-induced scour around bridge piers. Ocean Eng. 2022, 244, 110373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Kong, X.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Hu, J. Numerical modeling of solitary wave-induced flow and scour around a square onshore structure. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baykal, C.; Sumer, B.M.; Fuhrman, D.R.; Jacobsen, N.G.; Fredsoe, J. Numerical investigation of flow and scour around a vertical circular cylinder. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2015, 373, 20140104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Zou, W.; Chen, B.; Li, J. Numerical investigation of flow and scour around complex bridge piers in wind-wave-current conditions. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Nabi, M.; Kimura, I.; Shimizu, Y. Numerical investigation of local scour at two adjacent cylinders. Adv. Water Resour. 2014, 70, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, D.C. Turbulence Modeling for CFD, 3rd ed.; DCW Industries: La Canada, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Van Rijn, L. Sediment transport, Part I: Bed load transport. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1984, 110, 1431–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulsby, R.L.; Whitehouse, R.J.S. Threshold of sediment motion in coastal environments. In Proceedings of the 13th Australasian Coastal and Ocean Engineering Conference and the 6th Australasian Port and Harbour Conference, Christchurch, New Zealand, 7–11 September 1997; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- BenMeftah, M.; Mossa, M. New approach to predicting local scour downstream of grade-control structure. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2020, 146, 04019058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).