1. Introduction

Continuously reinforced concrete pavement (CRCP) is a Portland cement concrete pavement with continuous longitudinal steel reinforcement and no regular transverse joints (except transverse construction joints). Concrete undergoes volume changes due to temperature and moisture variations, called environmental loading, which results in transverse cracking. In CRCP, continuous longitudinal steel restrains concrete volume changes, which results in numerous hairline transverse cracks. If CRCP is properly designed and constructed, these cracks are held so tightly that they provide structural continuity throughout the pavement, which is responsible for the excellent performance of CRCP. Traditionally, longitudinal steel has been placed beneath the slab surface at somewhere between one-third and one-half of the depth, with only one reinforcement mat; there was no need for more than one mat. However, as slab thicknesses have increased, the spacing between longitudinal steel decreased to a point where a concern was raised as to whether the smaller clear spacing between longitudinal steel could cause concrete consolidation issues. This necessitated placing the steel in two layers. The two-mat system doubles the spacing between longitudinal bars. While the major motivation was attaining adequate spacing of steel bars, this arrangement also ensures that both upper and lower portions of the pavement receive adequate reinforcement for concrete slab restraint and stress distribution. Since the 1980s, the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) has used a single-mat reinforcement for CRCP up to 330 mm (13 in) thick, and double-mat for 356 mm (14 in) and 381 mm (15 in) thick CRCP.

More recently, it has been found that using two-mat reinforcement in CRCP provides greater concrete restraint, particularly near the top surface, which results in narrower crack widths and a closer crack spacing compared to a single-mat design, even with similar total steel content. Narrower crack widths ensure better load transfer and prevent the infiltration of water and incompressible materials, which is crucial for long-term performance [

1,

2,

3]. Structurally, having two layers of longitudinal steel modifies the stress distribution in the slab [

1]. Under environmental loading, a single layer of steel at mid-depth primarily controls the middle portion of the slab, whereas the top and bottom of a thick slab receive less restraint. This can increase the likelihood of the horizontal cracking issues observed in Texas, along with other distresses. Choi and Won [

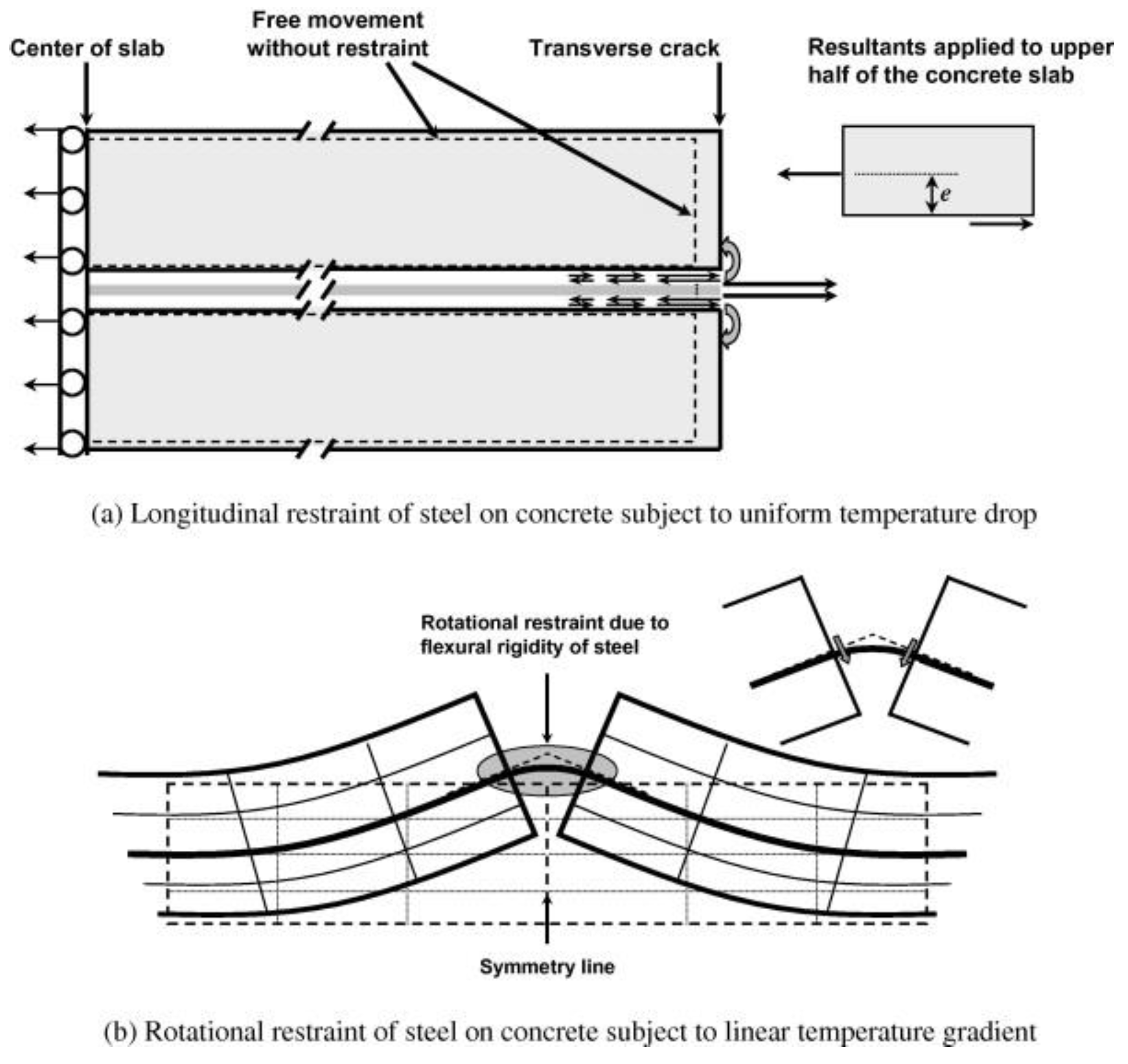

1] conducted primarily theoretical analyses of the mechanism of horizontal cracking in CRCP. According to this study, when a CRCP slab experiences a temperature drop, continuous longitudinal steel across transverse cracks restrains slab movement and this restraint, which acts eccentrically due to the steel’s depth, induces local bending and vertical stress near the steel, as shown in

Figure 1a. Moreover, near a transverse crack, two adjacent slabs rotate away from each other when concrete curls due to temperature differentials throughout the pavement depth, but the steel running through the crack resists that rotation due to its flexural rigidity. This rotational restraint imposed by the steel creates a vertical tensile stress in concrete at the steel depth, pushing against the concrete in that region, as illustrated in

Figure 1b. If this stress becomes greater than the tensile strength of concrete, horizontal cracking develops at or near the steel depth. The study found that even though the steel ratio of a slab with two-mat steel placement was the same as with one-mat reinforcement, vertical concrete stresses in two-mat slab were significantly reduced [

1]. This result was attributed to the shorter vertical distance (eccentricity) between where the steel provides its restraining force and where the opposing reaction occurs in the slab, which lessens the bending effect at the crack and reduces the resulting vertical concrete tensile stress around the steel.

TxDOT remains the only agency with a long-established two-mat CRCP standard supported by extensive long-term monitoring, although a recent project in Bangladesh reported the first documented use of a two-layer CRCP system outside the United States [

4]. The Bangladesh section, constructed in 2023 on a 275 mm slab, is still new and lacks long-term performance data, but it confirms that two-layer reinforcement is beginning to appear internationally.

Table 1 outlines the current TxDOT’s design standard [

5]. As shown, the standard specifies distributing the total longitudinal steel percentage equally between the upper and lower mats. This design was developed in the 1980s and implemented at that time based on engineering judgment, but with no in-depth technical evaluations. Therefore, in order to fully utilize the benefits of two-mat steel in thick CRCP, several design details need to be fully evaluated, such as the proper placement depths and amounts of steel in each layer.

The existing literature consistently shows that reinforcement depth and reinforcement content influence crack spacing, crack width, load-transfer behavior, and long-term performance. For example, a report from the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) shows that placing longitudinal reinforcement deeper in the slab increases predicted punchouts and terminal IRI, whereas shallower placement leads to tighter crack spacing and better load-transfer efficiency [

6]. Similar trends appear in European studies of CRCP sections in Germany, Belgium, and Poland, where slab thickness, concrete quality, reinforcement layout, base stiffness, and environmental exposure were shown to shape crack spacing and crack patterns across multiple decades of field experience [

7]. A study by Lee et al. [

8] demonstrated that reinforcement depth also affects horizontal cracking potential. The study consisted of a field test that investigated the impact of longitudinal steel depth on the early-age behavior of 330 mm thick CRCP in Texas. Field experiments compared steel placed at the mid-depth with steel placed 38 mm above the mid-depth. The findings showed that placing steel 38 mm above mid-depth reduced the risk of horizontal cracking, resulted in tighter transverse crack widths, and shifted the slab’s response from flexural to more axial behavior under environmental loading. The hypothesis of the current study is that, in thicker CRCP with a two-mat steel design, the top-layer steel will play a more dominant role in restraining concrete volume changes than will the bottom-layer steel. As such, increasing the amount of steel in the top mat while reducing it in the bottom mat may offer improved performance with potentially a lower cost. Likewise, slightly raising the position of both mats could provide greater restraint on the concrete near the pavement surface, where temperature and moisture fluctuations are greatest.

This study intends to use a combination of finite-element modeling (FEM) and field testing to evaluate how variations in reinforcement placement affect stress distribution, crack width, and concrete response under environmental loading. The current phase focuses on a preliminary mechanistic analysis of CRCP with two-mat steel configurations using three-dimensional FEM. The goal is to understand how variations in steel placement, such as the depth and spacing of top and bottom mats, affect structural responses under environmental loadings. The results of this study will guide the selection of reasonable steel layouts for field experiments in the next phase.

2. Methodology

This study conducted a mechanistic analysis of two-mat CRCP configurations using three-dimensional finite-element models developed in ANSYS 2024 R1. The analysis focused on evaluating the influence of steel placement on the structural response of thick CRCP under environmental loadings. As shown in

Table 2, a factorial experiment was implemented, covering a range of geometric and thermal variables that influence pavement behavior. For each thickness, the depth of the top steel layer was fixed at 127 mm (5 in) from the slab surface, while the bottom steel layer varied across three depths. Top steel spacing was also varied at three levels, while bottom steel spacing was set either equal to the top spacing (“Regular”) or twice the top spacing (“Alternate”). This alternate design is more top-layer-focused than the current design, as it removes some steel from the bottom layer while increasing the amount of steel in the top layer. The 2 levels of coefficient of thermal expansion (CoTE) values of concrete were 8.1 and 9.9 microstrains/°C, corresponding to 4.5 and 5.5 microstrains/°F. Thermal gradients were applied as 0.66 °C/cm and −0.33 °C/cm, corresponding to +3 and −1.5 °F/in, and temperature drops from setting were 16.7 °C and 27.8 °C, corresponding to 30 and 50 °F. Crack spacing levels were 0.6, 1.2, 1.8, 2.4, and 3.7 m (2, 4, 6, 8, and 12 ft). A total of 2160 simulation cases were generated from the combination of all variable levels.

2.1. Material Properties

The CoTE of concrete varied between 8.1 and 9.9 microstrains/°C to account for differences in coarse aggregate types in concrete. In Texas, CoTE is heavily influenced by the coarse aggregate type, with siliceous river gravel producing higher values. To reduce the risk of surface distress, particularly spalling, TxDOT limits the CoTE of concrete to a maximum of 9.9 microstrains/°C. The concrete was modeled with an elastic modulus of 34.5 GPa and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.15. An elastic modulus of 200 GPa and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.30 were selected for reinforcing steel. The support conditions were represented using the Winkler foundation model, with a modulus of subgrade reaction set at 82 MN/m3.

2.2. Geometry

Two steel layouts were developed to evaluate the influence of bottom steel spacing on slab behavior. In both cases, the top and bottom mats had the same depth, while the spacing of the bottom steel varied, as shown in

Figure 2. Each slab was 3.66 m wide.

In the first configuration, the spacing of the top and bottom longitudinal bars was kept equal. This setup is referred to as “Regular” steel layout in this study.

In the second configuration, the bottom steel spacing was set to twice that of the top mat. This layout is referred to as “Alternate” steel layout.

To improve computational efficiency, a symmetrical plane approach was applied in the modeling. Only half of the CRCP slab between two transverse cracks was modeled, using symmetrical boundaries along both the longitudinal and transverse directions. This approach reduced mesh size and analysis time without compromising accuracy. Validation checks showed that the difference in maximum steel stress between full and half geometries was less than 0.5%, confirming that the symmetry assumption was appropriate for evaluating the behavior and responses.

Figure 3 shows a typical geometry with 1.2 m crack spacing.

2.3. Temperature Loadings

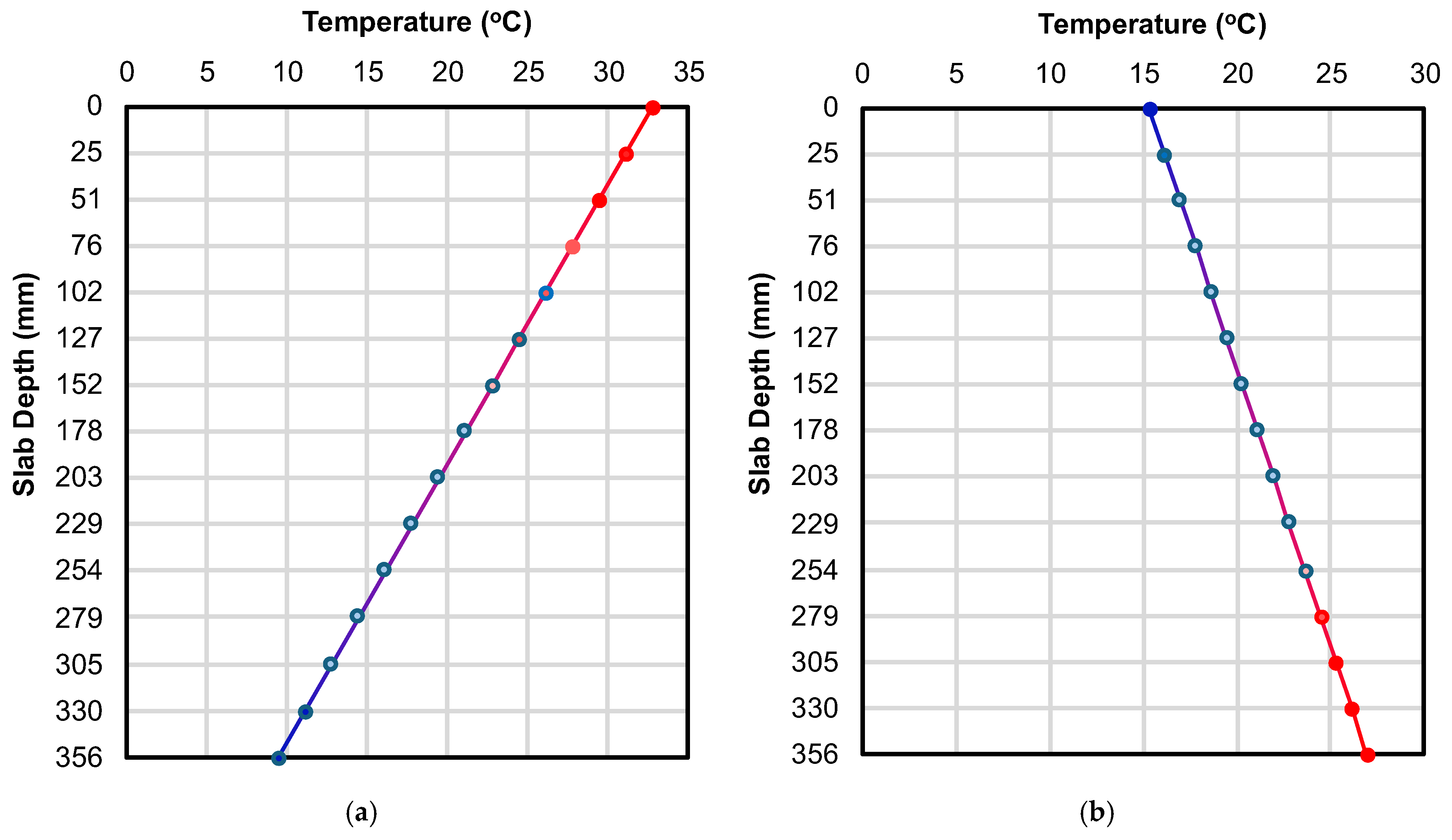

Two linear temperature gradients were applied through the slab depth to simulate daily thermal variations: 0.66 °C/cm and −0.33 °C/cm, as illustrated in

Figure 4. The positive gradient represents conditions in which the top of the slab is warmer than the bottom, typically occurring during the daytime. The negative gradient reflects situations in which the bottom of the slab is warmer than the top, which is common at night or during rapid surface cooling. According to Huang [

9], the typical daytime gradients range from 0.55 to 0.76 °C/cm, while nighttime gradients are about half that range, between 0.27 and 0.38 °C/cm. The selected values fall within these conditions and were used to evaluate the slab’s curling behavior and stress development under different thermal loading scenarios.

2.4. Drying Shrinkage

Since ANSYS does not allow direct input of shrinkage strains, an indirect approach was used by converting shrinkage to an equivalent temperature drop. This method enables simulation of shrinkage effects using thermal loading. The conversion was based on Equation (1):

where

T is the equivalent temperature change,

ε is the shrinkage strain, and

α is the coefficient of thermal expansion of concrete.

To account for the nonlinear variation of shrinkage through the slab depth, the shrinkage strain was defined using Equation (2) proposed by Desai [

10]. This formulation captures the higher shrinkage near the surface due to moisture loss, which is consistent with physical behavior in concrete pavement.

where

Y is the slab height from the bottom,

εSH(Y) is the shrinkage strain at height

Y, and

λ = 0.01893867. The coefficients

a and

b were taken as 24.55357 and 0.446429, respectively, corresponding to 7-day drying shrinkage of 400 microstrains.

The resulting equivalent temperature reduction from shrinkage was superimposed on the applied thermal gradient (+0.66 °C/cm or −0.33 °C/cm) to create a composite temperature profile that accounts for both drying shrinkage and thermal effects. For instance,

Figure 5 illustrates the combined profile for a −0.33 °C/cm gradient, a CoTE of 8.1 microstrains/°C, and a 16.7 °C temperature drop. These composite profiles were applied across the slab depth in the finite-element model.

2.5. Contact Regions

The steel–concrete interface was modeled with a fully bonded (no-slip) condition. Although bond-slip relationships are sometimes used in reinforced-concrete modeling, previous CRCP-specific studies that directly compared finite-element predictions with field-measured steel strains under environmental loading concluded that this approach tends to underestimate responses and misrepresent actual field behavior in CRCP [

8]. The study showed that the fully bonded condition more closely matched field-measured strains under similar thermal conditions. While this assumption does not capture potential slip along the steel–concrete interface, and the resulting strain compatibility may lead to slightly higher stresses than would occur in service, it helps to better replicate in situ pavement behavior.

In contrast, transverse crack faces were modeled with a frictionless contact condition, allowing the two surfaces to slide over each other without resistance, meaning they can separate freely in all directions. This simplification produces conservative estimates of steel stress and crack width because all restraint against slab contraction and all load transfer across the crack are carried solely by the continuous longitudinal reinforcement. Although aggregate interlock is present in tight cracks and contributes to load-transfer efficiency, the frictionless assumption represents a reasonable worst-case scenario for design-oriented comparative studies.

2.6. Mesh Discretization

All concrete and steel components were modeled using ANSYS SOLID185 elements, which are eight-node hexahedral (brick) elements capable of capturing three-dimensional stress states. To improve accuracy in regions of interest, finer mesh sizes were applied locally, particularly around the steel. A mesh sensitivity analysis was conducted by varying the longitudinal concrete element size from 2 in to 0.75 in across several representative slab configurations. The results showed that reducing the element size from 1.5 in to 1 in produced noticeable changes in stresses, while further refinement to 0.75 in resulted in only small additional changes with a substantial increase in computational time. Based on this convergence behavior, a 1 in longitudinal element size was selected, with local refinement around the reinforcement, as it provided a balance between accuracy of stress prediction, and computational efficiency.

Figure 6 shows the representative mesh models used in the study.

2.7. Boundary Conditions

To simulate conditions consistent with planned field experimentation, boundary conditions were defined based on the expected slab placement configurations. Since the instrumentation will likely be installed on the outside shoulder, the longitudinal edge of the model was defined as a free boundary, representing the unconfined condition at the slab edge. It was also assumed that the longitudinal steel does not displace at a transverse crack in the longitudinal direction. While this may not fully reflect all realistic field conditions, especially where crack spacing is irregular, it provides a reasonable approximation when cracks are evenly spaced, as is typical in stable CRCP sections. However, vertical movement of the longitudinal steel at cracks was permitted, acknowledging that slab curling due to temperature gradients requires the steel to follow the vertical displacement of the surrounding concrete.

2.8. Definition of Key Evaluation Points

Seven key evaluation points were selected to align FEM output with field data collection and to capture the most relevant structural behaviors influencing CRCP performance. These points, as listed below, were chosen based on sensitivity in modeling and field relevance to strain, stress, and crack movement.

Maximum stress in the top-layer longitudinal steel at transverse crack.

Maximum stress in the bottom-layer longitudinal steel at transverse crack.

Concrete stress near top steel depth at transverse crack.

Concrete stress near bottom steel depth at transverse crack.

Crack width at top steel depth.

Crack width at bottom steel depth.

Concrete stress at slab surface (to evaluate potential for additional crack formation).

2.8.1. Maximum Tensile Stresses in Top and Bottom Longitudinal Steel

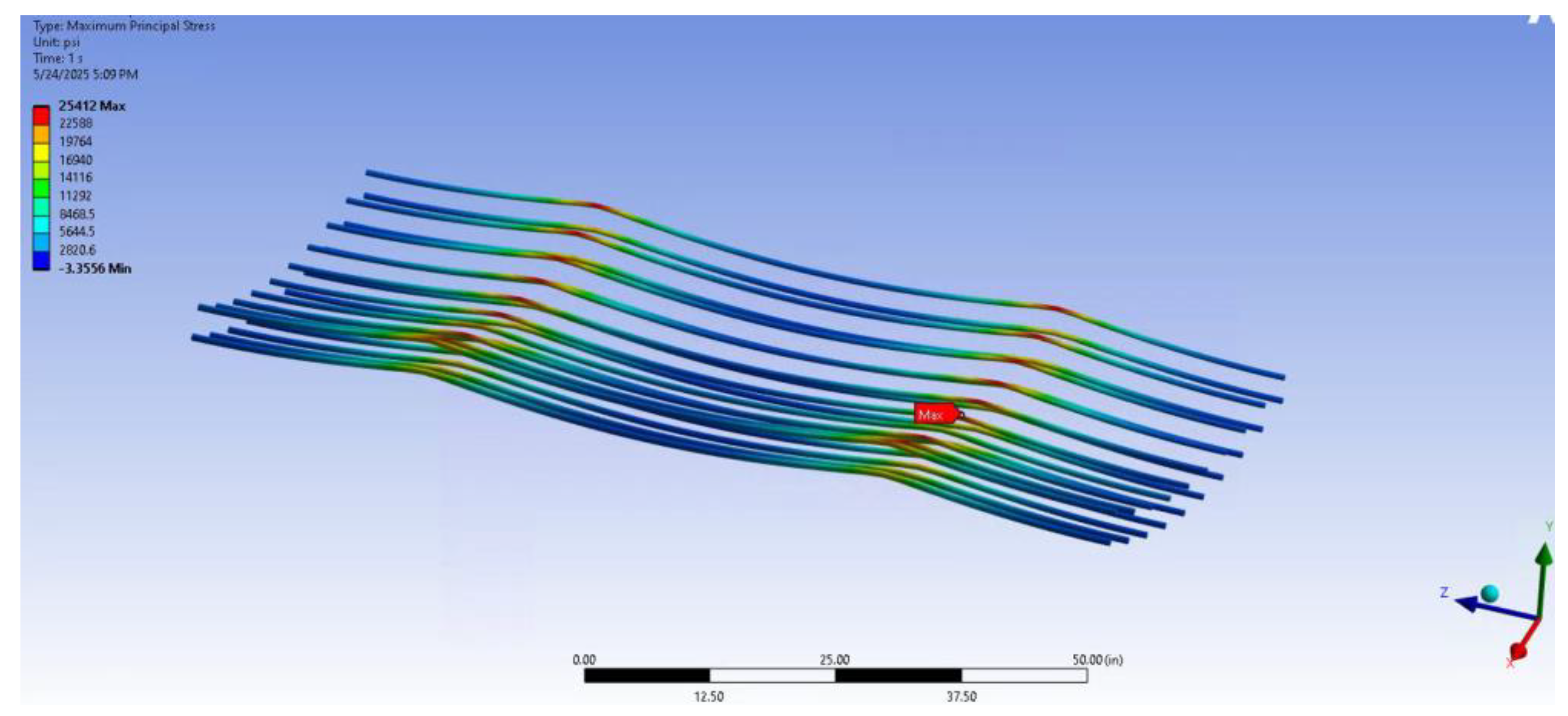

These locations were evaluated to assess the tensile demand in the reinforcement at the transverse cracks. FEM results consistently showed peak stresses at these cracks, as shown in

Figure 7. In the field experimentation of the second phase of this study, steel strain gauges will be installed to capture this behavior. The top steel typically experiences higher stress due to greater temperature and moisture fluctuations near the surface. To prevent rebar failure, the tensile stress should remain below 310 MPa for steel with a yield strength of 414 MPa (60,000 psi), corresponding to 75% of the yield strength.

2.8.2. Concrete Stress Surrounding the Top and Bottom Steel at the Transverse Crack

Theoretical analysis has indicated that wheel and environmental loading applications create significant localized stresses near the steel–concrete interface, contrary to the traditional assumption that maximum stresses occur at the slab bottom [

11]. These interactions can lead to horizontal cracking near transverse cracks. Stress concentration develops around the steel due to restrained volume changes, especially near the transverse cracks. FEM contour plots show localized zones of high principal stress in concrete near the reinforcement, as shown in

Figure 8, which presents the transverse crack plane viewed in the longitudinal direction. In future experiments, these zones will be monitored in the field using embedded vibrating wire strain gauges (VWSGs). If concrete tensile strength is exceeded, horizontal cracking or delamination may initiate along the steel plane.

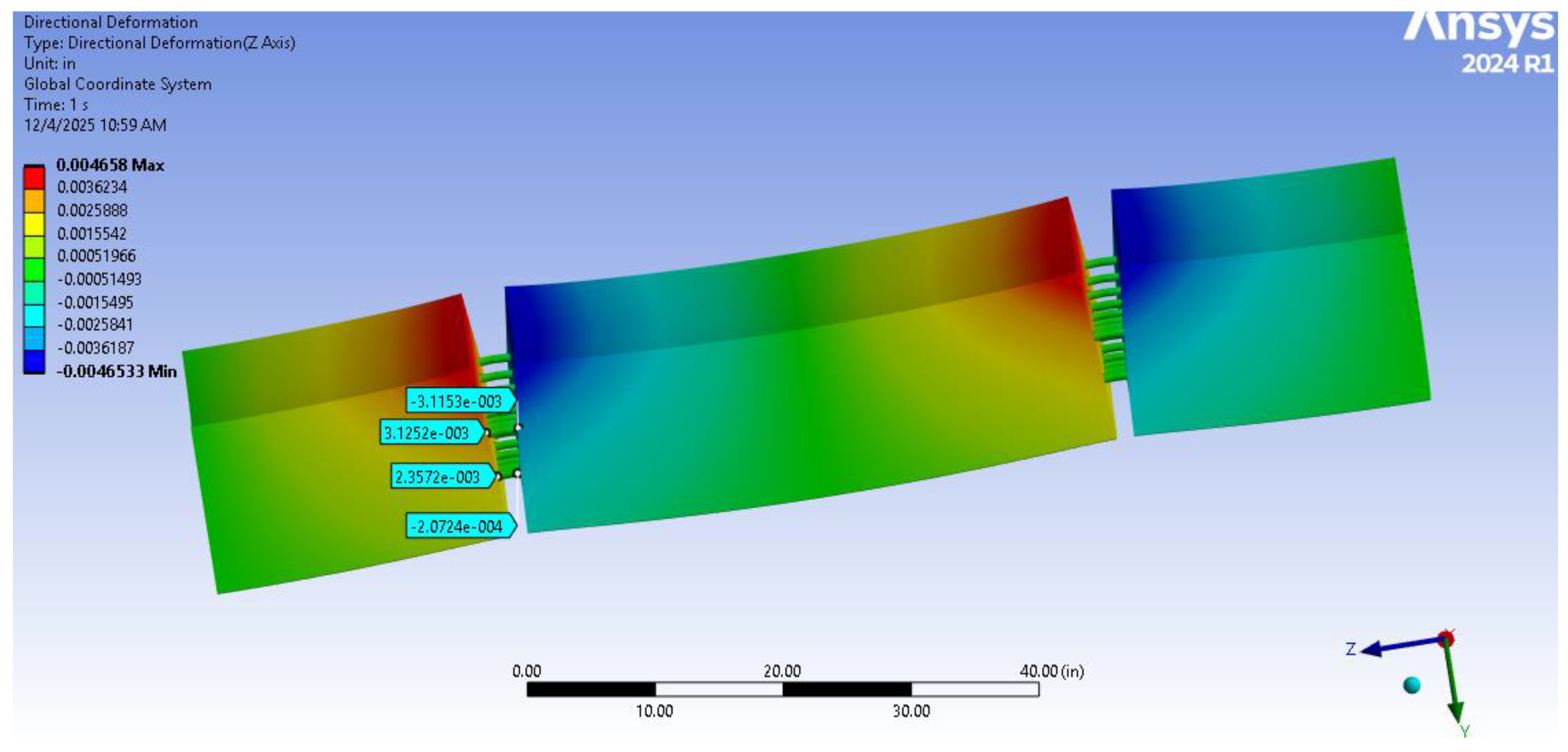

2.8.3. Crack Width at Top and Bottom Steel Depths

Figure 9 shows how crack width was estimated in the finite-element simulations. It was calculated as the relative longitudinal displacement between adjacent slab segments at the steel depth. Displacement data was extracted at the same depths at which crackmeters and longitudinal VWSGs will be installed during field experiment. Crack width is a performance indicator, with the

Mechanistic–Empirical Pavement Design Guide (MEPDG) recommending that it stays below 0.5 mm at steel depth [

6]. Wider cracks may compromise load transfer, increase water infiltration, and lead to other distresses such as pumping, spalling, or punchouts.

2.8.4. Maximum Principal Stress at the Slab Surface

This location helps evaluate the potential for forming additional transverse cracks between the selected transverse cracks in this modeling. Surface stress is influenced by thermal gradients and restraints, particularly during periods of rapid temperature change. FEM results show elevated surface stress under both positive and negative gradients. While the literature suggests desirable crack spacing is between 0.9 and 2.4 m [

6], field evidence shows that spacing alone does not degrade performance unless the cracks are defective [

11]. As a matter of fact, observation of the 356 mm two-mat section on IH 35 in Waco, Texas showed that multiple crack spacings were less than 0.6 m with very good performance. Therefore, this point was included to assess the potential for additional crack propagation, not as a failure indicator.

3. Results

This chapter presents the results of the analysis. The primary objective is to understand how variations in slab thickness, reinforcement depth and spacing, thermal loads, and crack spacing affect stress, displacement, and crack behavior within the pavement. Comparisons between regular and alternate configurations are also included to assess how redistribution of steel influences structural behavior.

3.1. Effect of Temperature Gradient, CoTE, and Temperature Drop from Setting

The influence of thermal parameters on steel stress, concrete stress, and crack width was examined using a 356 mm (14 in) CRCP section with a crack spacing of 1.2 m (4 ft), a top steel spacing of 191 mm (7.5 in), and a bottom steel depth of 203 mm (8 in) as a representative case. This configuration was selected because its trends were consistent with those observed across the full range of slab thicknesses and crack spacing scenarios, making it suitable for isolating and illustrating the effects of CoTE, temperature drop from setting, and temperature gradient.

Across all response measures evaluated in this study, the same thermal condition governed the behavior of the slab, with larger CoTE values and greater temperature drops from setting producing larger concrete volume changes. The combination of −0.33 °C/cm gradient, a CoTE of 9.9 × 10−6/°C, and a temperature drop of 27.8 °C consistently resulted in the highest steel stress, the widest crack openings, and the largest localized stresses in the concrete surrounding the steel. Because this trend was uniform across all metrics and across both steel layouts, the following discussion focuses on differences between the regular and alternate reinforcement configurations instead of repeating identical explanations for each thermal scenario.

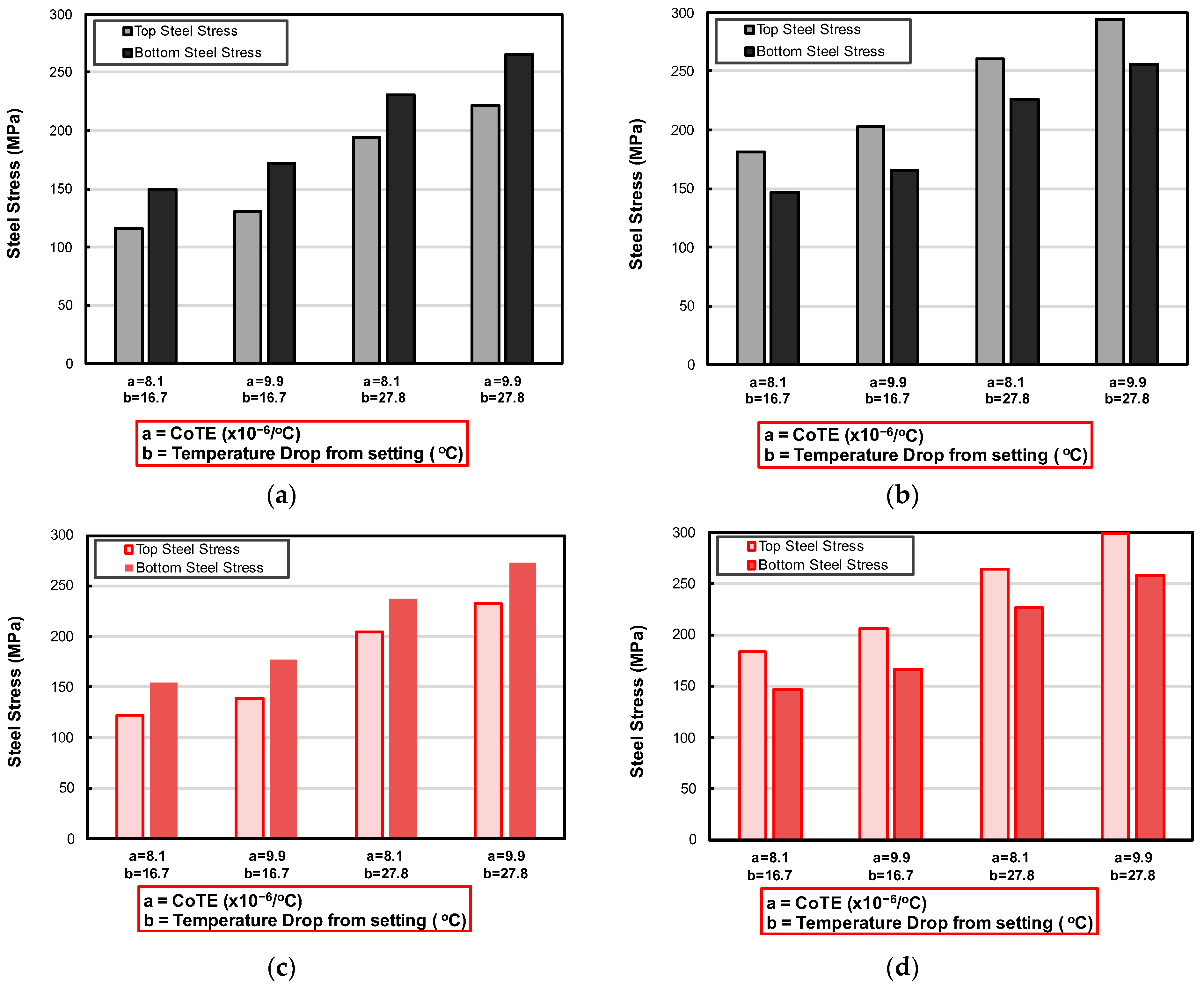

3.1.1. Effect on Top and Bottom Steel Stress

Figure 10 illustrates the top and bottom steel stresses under different combinations of thermal input conditions for both regular and alternate models. For both steel layouts, the steel stresses increased with higher CoTE values and with greater temperature drops from setting. This behavior is expected, as increased CoTE and thermal gradients cause greater concrete displacements, which in turn raises the demand on the steel to restrain the slab. Under the governing thermal condition, the steel stress reached approximately 294 MPa in the regular configuration and 299 MPa in the alternate model. The small difference between the two indicates that removing part of the bottom reinforcement does not significantly affect the overall stress response. Furthermore, it can be observed that under the positive gradient when slab is curled downward, the stress was more pronounced in the bottom steel than in the top. In contrast, under the negative gradient condition (with slab curled upward), the top steel carried more stress. Overall, stress magnitudes were greater in the negative gradient cases compared to their positive gradient counterparts in both layouts.

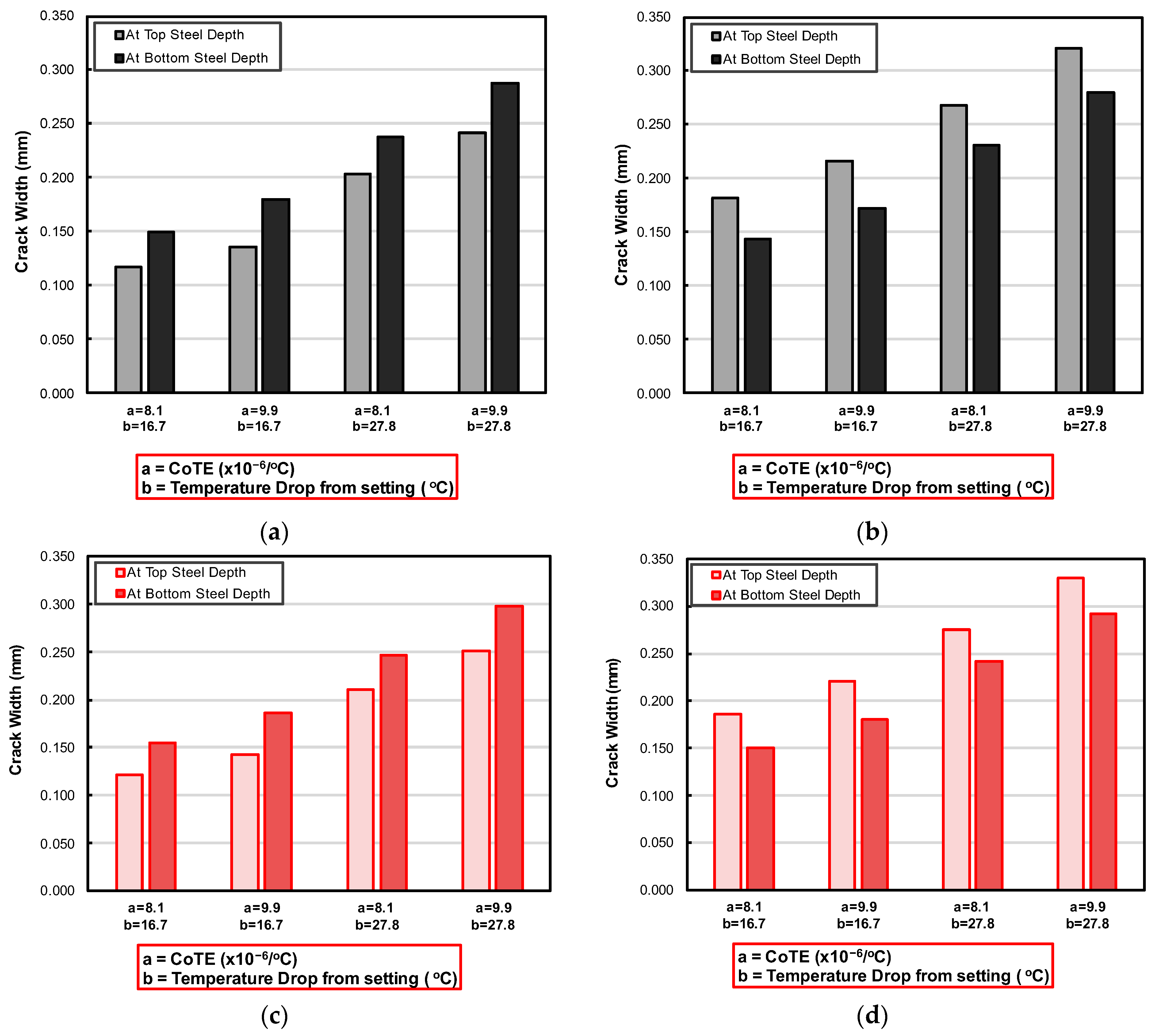

3.1.2. Effect on Crack Width

Crack width behavior followed the same trend patterns observed in the steel stress evaluations. As shown in

Figure 11, the crack width increased for larger CoTE values and as the temperature drop from setting was greater. This is expected since both parameters amplify the concrete volumetric changes and result in larger crack widths. The maximum crack width occurred near the top steel depth under the most demanding thermal scenario described above.

When separating results by temperature gradient, wider cracks were observed at the bottom of the slab under positive gradients due to downward curling. This condition causes the bottom portion of the slab to separate more, increasing the crack opening. Conversely, under negative gradients (upward curling), the top portion of the slab experiences more opening, which explains the higher crack widths recorded near the top steel depth under these conditions. Comparing reinforcement configurations, the alternate steel layout produced wider cracks than the regular models. This increase is attributed to the reduction in steel, which reduces the restraint on the concrete volume changes.

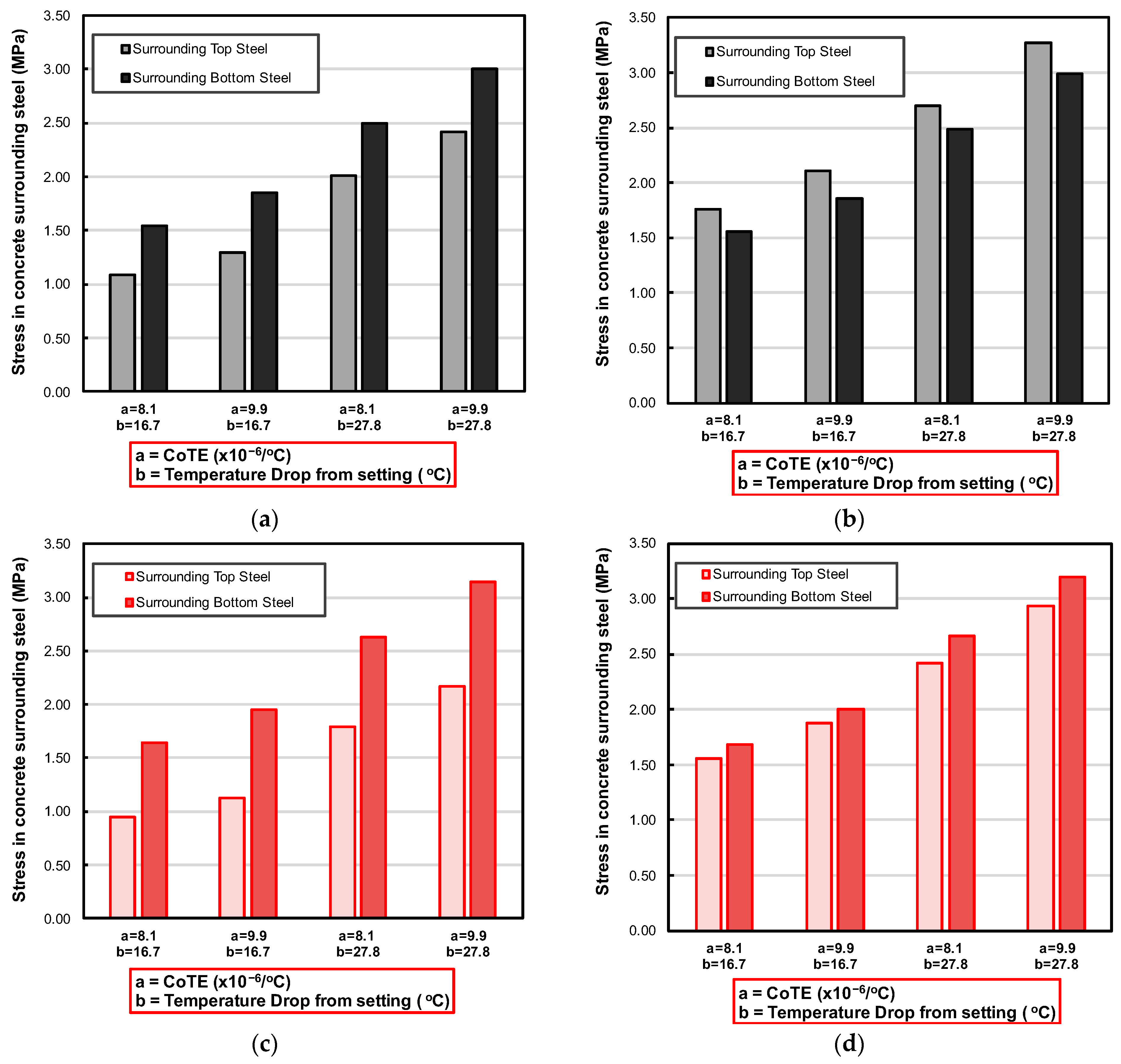

3.1.3. Effect on Stress in Concrete Surrounding Top and Bottom Steel

Stress in the concrete surrounding the longitudinal steel showed consistent trends with variations in CoTE, temperature drop from setting, and temperature gradient, across both regular and alternate steel layouts. An increase in either CoTE or temperature drop led to higher concrete stresses in all cases. This is expected, as higher CoTE and greater temperature differential induce larger volume changes in the concrete, which translates into higher stress in steel, and more localized stress in the concrete surrounding the steel. This result is illustrated in

Figure 12.

For the regular layout, the maximum stress was observed around the top steel at the critical thermal combination. The concrete stress at this point reached approximately 3.27 MPa. This top-region concentration is consistent with the upward curling behavior under a negative gradient, which causes the top layer to experience tension. On the other hand, the alternate case showed peak stress around the bottom steel under the same thermal loading. The concrete stress reached about 3.19 MPa. Removing some steel causes the remaining steel to carry more of the load, leading to an increase in localized stress at the surrounding concrete. This shift in location of peak stress from top to bottom is attributed to both the redistribution of restraint and the effect of bottom bar spacing on stress distribution. Overall, while the peak locations differed between the regular and alternate layouts, the concrete stress was generally higher in the regular layouts due to the greater restraint provided by the full reinforcement layout.

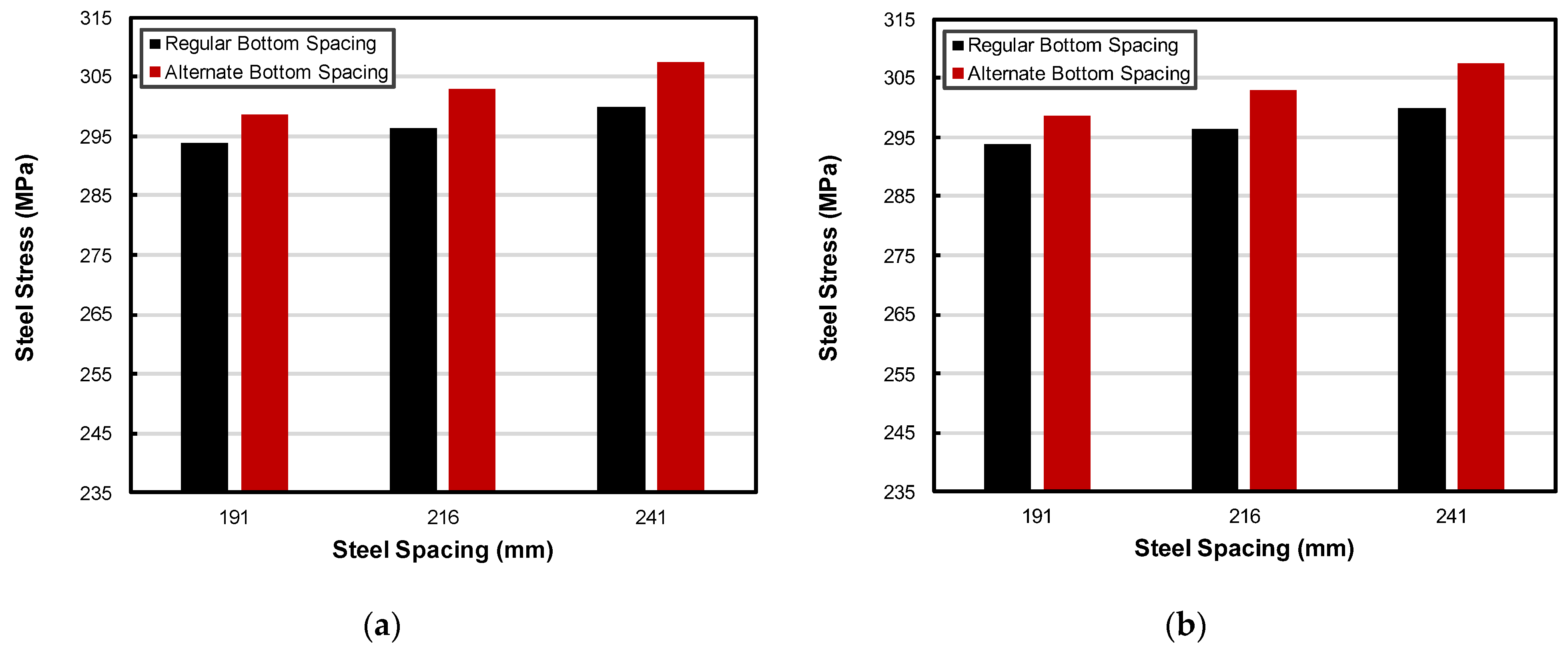

3.2. Effect of Steel Spacing on Structural Responses

For this evaluation, the critical thermal condition previously identified (CoTE = 9.9 × 10−6/°C, temperature gradient = −0.33 °C/cm, and temperature drop = 27.8 °C) was applied to study the influence of steel spacing on stress responses, using a 356 mm CRCP section with a crack spacing of 1.2 m.

3.2.1. Effect on Top and Bottom Steel Stresses

As shown in

Figure 13, the steel stress increased with increasing steel spacing. Wider spacing implies fewer bars per unit width of pavement, which reduces the total area of steel available to restrain concrete volume changes. Consequently, the demand on the remaining steel increases, resulting in higher stress levels. In alternate layouts, this effect is even more pronounced since the bottom mat contains fewer bars, which further concentrates stress on the remaining steel. Thus, the alternate layouts exhibited consistently higher stresses than the regular layouts at every spacing level.

3.2.2. Effect on Crack Width

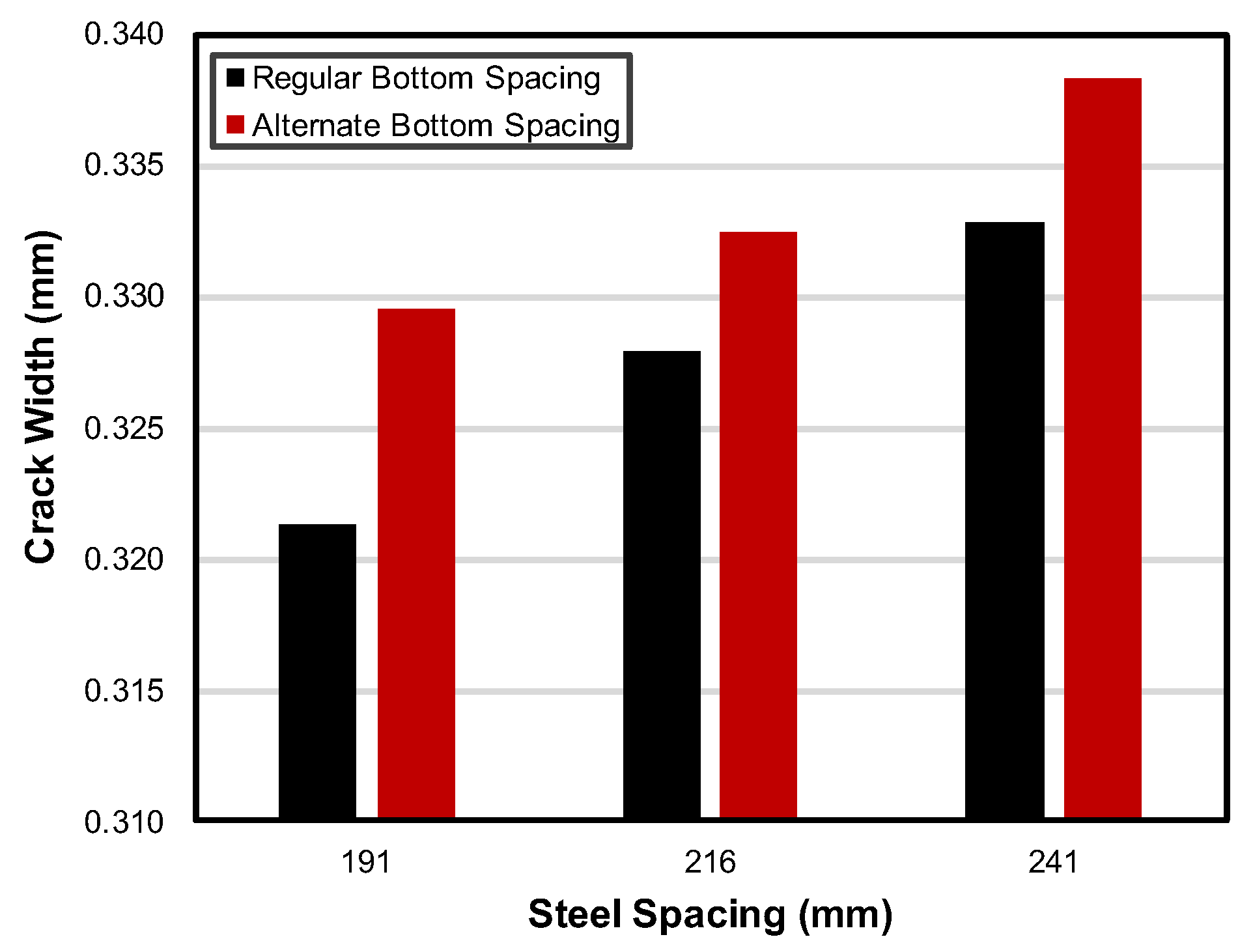

Crack width increased with wider steel spacing, as shown in

Figure 14. This behavior is expected because reducing the amount of steel reduces the overall restraint capacity of the system, allowing more concrete displacements at the transverse cracks. The trend was consistent across both regular and alternate layouts, though the alternate layouts produced larger crack widths at each spacing level. This is attributed to the reduced number of bottom bars in the alternate cases, which further lessens the system’s ability to resist volume changes in the concrete, leading to greater crack widths.

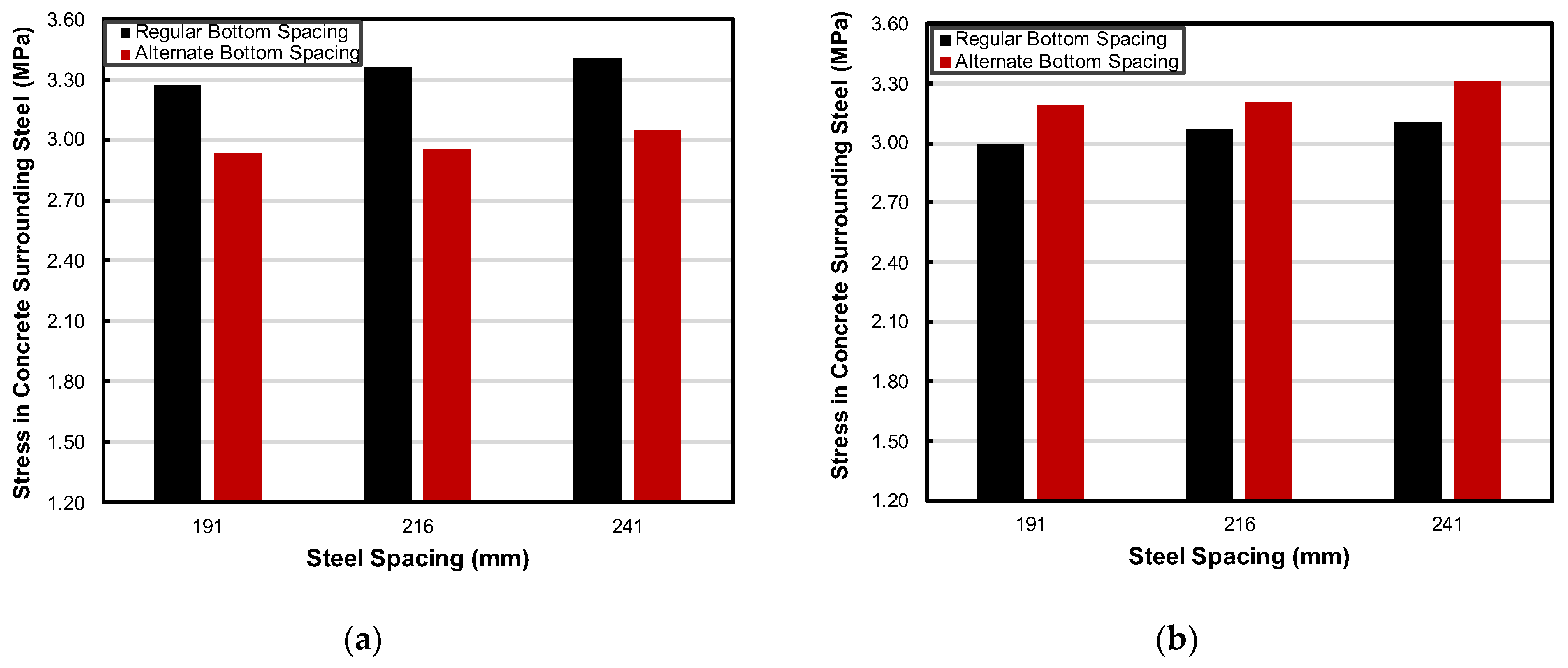

3.2.3. Effect on Stress in Concrete Surrounding Top and Bottom Steel

Concrete stresses surrounding the steel increased as steel spacing increased, as depicted in

Figure 15. This is driven by the higher stresses experienced in the remaining steel and the resulting localized effects. In the top steel region, concrete stress was lower in alternate layouts compared to the regular configuration. This is likely due to the reduced overall restraint, which allowed more deformation and led to less concrete stress buildup. On the other hand, in the bottom steel region, concrete stress was higher in alternate layouts. This can be attributed to the fewer bars carrying more load individually, which intensified localized stress around the remaining steel, even though the global restraint was reduced, as previously discussed.

3.3. Effect of Bottom Steel Depth on Structural Responses

The influence of bottom steel depth was also evaluated using 356 mm CRCP with 1.2 m crack spacing under the critical thermal condition. In all layouts, the top steel was kept constant at 127 mm from the surface, while the bottom steel depth was varied to assess its effect.

3.3.1. Effect on Top and Bottom Steel Stress

Figure 16 shows that as bottom steel depth from the concrete slab surface increased, top steel stress increased. This is because shifting more steel to the bottom leaves less reinforcement to restrain volume changes above the bottom layer of steel. Consequently, the stress demand on the remaining top steel becomes higher. In contrast, stress in the bottom steel decreased with increasing depth. This is as expected because the case considered is of upward curling of the concrete slab. In all cases, alternate bottom steel arrangements resulted in higher stress values compared to regular spacing, attributed to the reduced number of steel bars available to restrain slab movement.

3.3.2. Effect on Crack Width

Crack width at the top steel region increased as the bottom steel depth increased, as shown in

Figure 17, which can be explained by the reduced restraint provided by the bottom steel on the slab above the bottom steel. This effect is especially relevant under upward curling conditions, where the top portion of the slab contracts and crack width becomes larger. As the bottom steel moves deeper, its ability to resist slab movement at higher elevations diminishes, resulting in wider cracks. The alternate layouts consistently showed greater crack widths than did the regular layouts, again due to the reduced amount of steel available to restrain concrete volume changes.

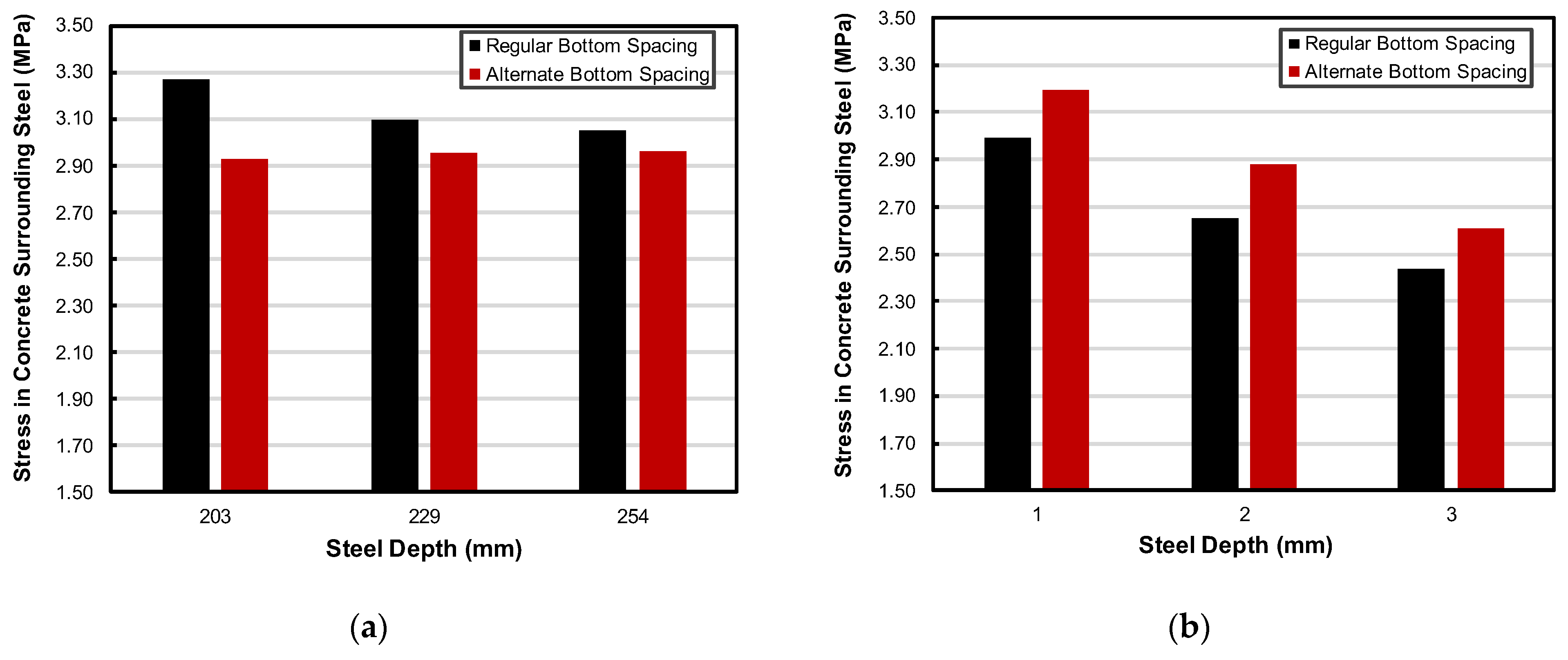

3.3.3. Effect on Stress in Concrete Surrounding Top and Bottom Steel

The stress in concrete surrounding steel generally decreased as the bottom bar depth increased, as shown in

Figure 18. This is because deeper placement of bottom reinforcement reduces the effectiveness of restraint within the concrete cross-section, thereby reducing internal stress buildup. However, an exception to this trend was observed in the stress surrounding the top steel in the alternate layouts. In those cases, the stress did not decrease in the same way but instead showed a localized increase. This can be explained by the redistribution of restraint demand to the top layer when the bottom steel is placed deeper and fewer bars are available to share the load.

3.4. Quantification of Changes in Regular Versus Alternate Layouts

This section presents a comparison between the regular and alternate reinforcement layouts using the previously established critical thermal condition. The focus is on quantifying the extent to which the steel stress, concrete stress, and crack width changed due to the reduced amount of steel in the bottom mat (alternate case).

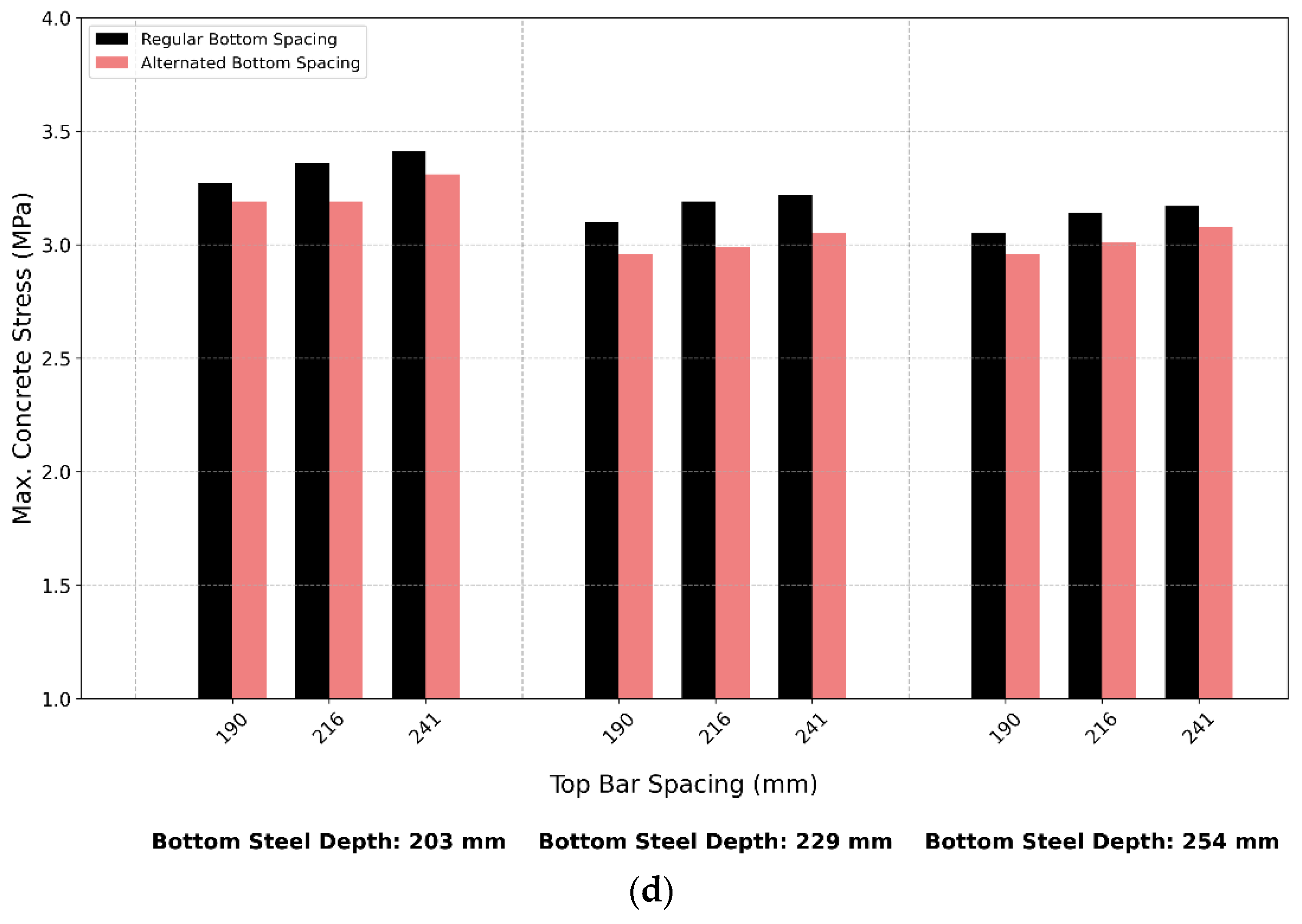

Figure 19a–d presents a direct comparison between regular and alternate steel configurations under critical thermal conditions for the 356 mm slab with 1.2 m crack spacing. Across all slab thicknesses evaluated, the alternate layouts consistently exhibited higher stresses in both the top and bottom steel, as well as increased crack widths. In contrast, the concrete stress measured at the steel depth was lower in the alternate cases, which aligns with the reduced level of restraint due to fewer steel bars. This reduction in concrete stress may help in mitigating the development of horizontal cracking within the slab. The average differences across parameters are quantified in

Table 3 for both the 356 mm and 381 mm CRCP sections. These results indicate that removing some of the bottom steel does not lead to a drastic increase in stress and may even reduce the overall localized stress in concrete.

3.5. Selection of Optimum Steel Configuration

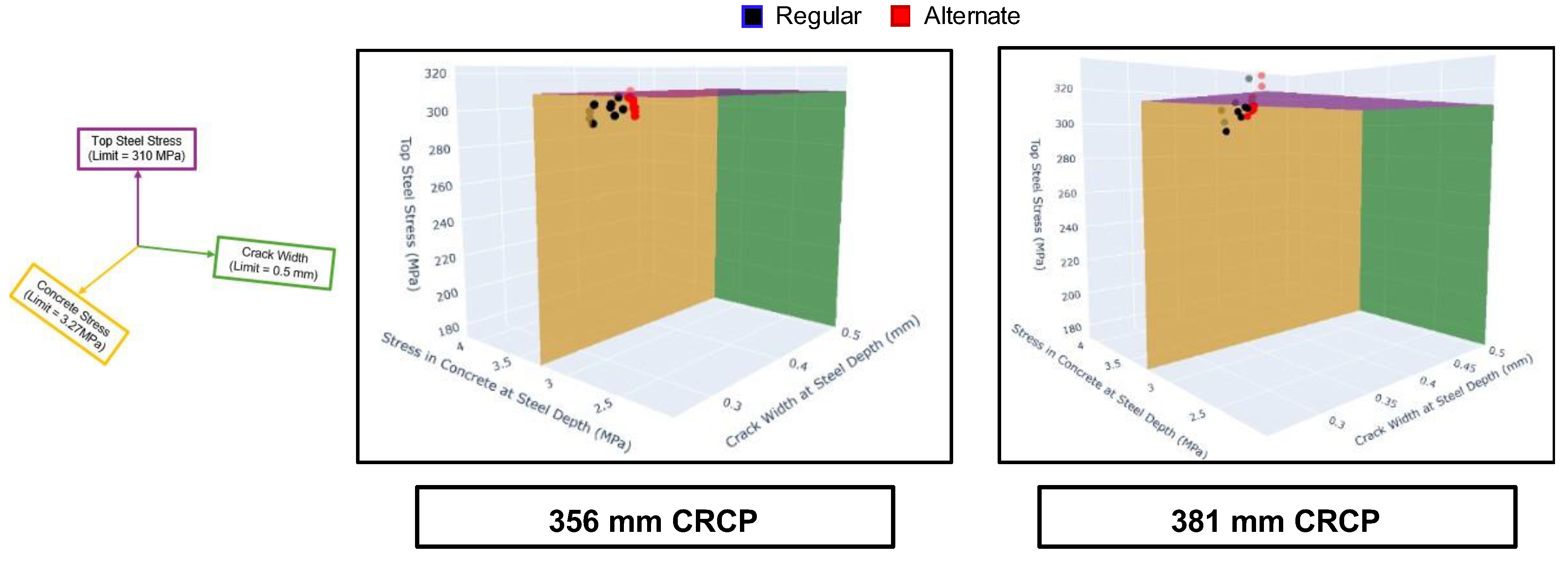

Figure 20 illustrates the step-by-step procedure used to select the optimum reinforcement configuration for CRCP. The process began by defining the environmental conditions and performance criteria that must be satisfied under critical conditions. These conditions were chosen based on their ability to trigger the most severe stress and deformation responses in the pavement, with the assumption that any design that performs adequately under such conditions would also perform satisfactorily in less severe environments.

After defining the criteria, all model combinations were screened, and only those meeting the specified thresholds were retained. A further check was made to ensure that both the regular and alternate versions of the same configuration satisfied the criteria. The performance of the configurations that passed this filter was then compared to the current design. This phase served to ensure that any proposed alternative offers at least the same or improved behavior. Since the same optimal design was observed across all crack spacing scenarios, the analysis focused on the 1.2 m spacing case.

3.5.1. Definition of Performance Criteria

The first phase involved defining both the environmental conditions and the performance thresholds used to screen the steel configurations. The selected thermal condition was based on the critical scenario observed in the analysis, and the performance limits were established based on structural design principles and serviceability recommendations. A maximum steel stress of 310 MPa was selected, corresponding to 75% of the 414 MPa yield strength typically used for reinforcing bars, to maintain a conservative margin below yielding. The concrete stress limit of 3.27 MPa was derived from the ACI tensile stress expression for a concrete compressive strength (f′

c) of 34.5 MPa, providing a tensile cracking threshold for concrete [

12]. The crack width limit of 0.5 mm was based on MEPDG recommendations for maximum crack width at steel depth in CRCP, to maintain adequate load transfer and minimize water infiltration [

6].

3.5.2. Performance Evaluation and Selection of Optimum

Figure 21 provides a three-dimensional visualization of how the design configurations performed relative to the set thresholds for the 356 and 381 mm slab thicknesses. Each point represents a configuration, and the shaded boundary planes indicate the filtering limits for top steel stress, concrete stress, and crack width. Any configuration falling outside these volumes was eliminated. While most points fell below the limits in 356 mm thick CRCP, fewer points were observed in the 381 mm thick CRCP. This result could be due to differences in the steel ratio.

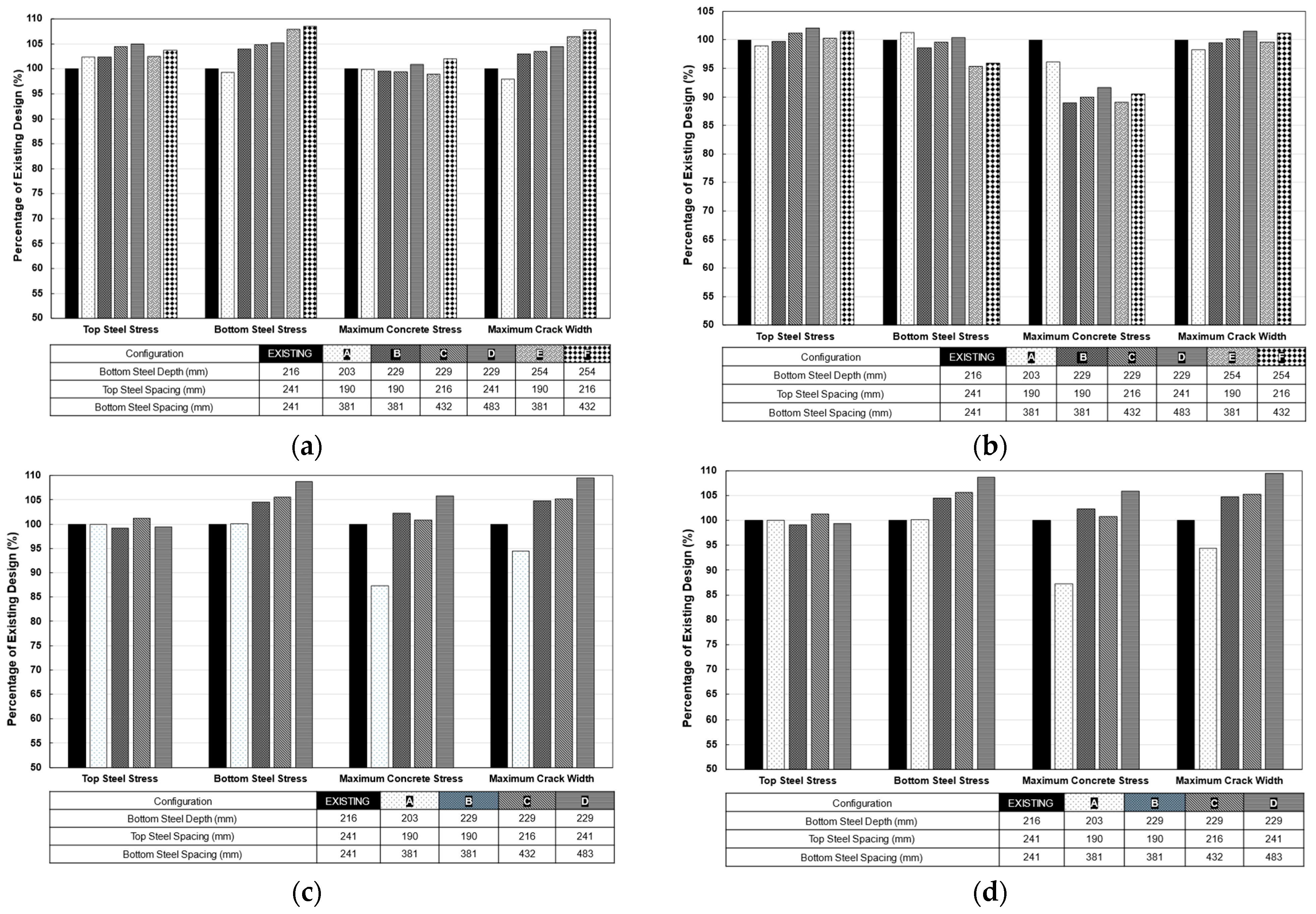

Figure 22a,b show a detailed breakdown of individual configurations for the 356 mm and 381 mm slabs, respectively. Each bar group represents a configuration defined by top spacing and bottom steel depth. The bar height provides top steel stress, while the overlaid markers indicate concrete stress and crack width. The limit lines are clearly shown for all three parameters. While many configurations stayed within the crack width and concrete stress limits, top steel stress was the dominant parameter responsible for disqualification in alternate layouts, especially in the 381 mm CRCP. Regular layouts generally performed better, but a few alternate versions still satisfied all three limits.

Figure 23a–d isolates the top-focused (alternate) configurations (A–F) that passed the filtering process and presents the results as a percentage of responses attained from the current TxDOT design. The charts compared the results under extreme cases of temperature drops and CoTE (27.8 °C and 9.9 × 10

−6/°C, respectively) for both positive and negative temperature gradients. In many cases, the proposed configurations had steel stresses close to the limit but remained within an acceptable range. The same process was carried out for crack width and stress in concrete. The intent of this step was to verify that selected configurations were not just satisfactory in isolation, but also competitive with existing TxDOT practice. While steel stresses were, in few cases, slightly higher in the top-focused design than the existing design, some variants of the alternate designs consistently achieved lower concrete stresses and crack widths, making them favorable alternatives, since the steel stress is still considerably below the yield strength of steel.

Table 4 summarizes the final configurations considered for implementation along with the responses under critical conditions for 1.2 m crack spacing. Two top-focused designs were selected for the 356 mm slab thickness and one for the 381 mm slab thickness. These designs increase the amount of reinforcement at the top layer over the current TxDOT design, while reducing the amount of steel at the bottom. This redistribution of reinforcement is expected to provide improved control of surface-related distresses while maintaining overall adequate performance. In general, the selected configurations are expected to perform better than the current TxDOT design and offer cost advantages through a reduced total steel ratio.

The results in

Table 4 show that maximum tensile stress consistently occurred in the top steel layer, as already discussed. Although an increase in bottom steel stress was observed, it was still relatively small compared to the stress in the top steel layer. Reducing reinforcement in the bottom mat and redistributing it toward the top layer effectively lowered the top steel stresses in the 356 mm slab by about 1%, with negligible change in the 381 mm section compared with the existing two-mat design. Since the analysis was based on a 1.2 m crack spacing, additional crack formation in the field is expected to further relieve steel stresses. A reduction in concrete stress at steel depth was also observed in both the 356 mm and 381 mm sections, with decreases of about 4% and 11% for the 356 mm options, and about 13% for the 381 mm section, indicating a lower likelihood of horizontal cracking. The optimized configurations are also expected to produce narrower crack widths, including about a 2% reduction for the 356 mm slab and about a 5% reduction for the 381 mm slab. Finally, the reduced steel ratios of the shortlisted designs, which decreased by about 5% for the 356 mm slab and about 1% for the 381 mm slab, are expected to result in material savings without compromising structural performance.

4. Discussions

The results of this study showed that environmental loads strongly influence CRCP behavior, especially near the surface. Larger CoTE values and greater temperature drops from setting produced larger volume changes in the slab, which raised steel stress, widened crack openings, and increased stress in the surrounding concrete. Across all slab thicknesses and crack spacings, the same thermal condition consistently produced the highest responses. This critical condition corresponds to a negative gradient that causes upward curling in CRCP. Under this scenario, the top reinforcement carried the highest tensile stress, and the concrete surrounding that layer experienced the greatest tension. Crack opening was also largest near the top steel, confirming that the upper region of the slab governs structural response under severe temperature-induced curling.

The comparison between regular and alternate layouts showed that removing some of the bottom reinforcement reduced overall restraint, which lowered concrete stress around both layers but placed slightly more tensile demand on the steel. This is expected since the alternate layout has much less steel and would have to distribute the stress to the remaining steel present in the system. Even so, the stress increases were modest, and remained well below capacity. More importantly, the reductions in concrete stress may help prevent horizontal cracking. Overall, it can be concluded that heavy reinforcement in the bottom layer is not necessary for maintaining performance in two-layered CRCP. Since the top reinforcement controls behavior under the governing thermal condition, shifting some reinforcement upward provides a more efficient balance between structural demand and material use. When the overall steel ratio remained similar but slightly more reinforcement was placed at the top, the upper layer was found to effectively provide restraint where it is most needed, while the bottom layer still provided enough restraint to limit excessive movement at the lower portion of the slab. The selected configurations produced lower concrete stresses, smaller crack widths, and steel stresses that remained well below yield strength. The redistribution also reduced the total steel ratio without compromising performance.

The findings from this study provide useful insights for design comparison but remain subject to some important limitations. Firstly, the model employed linear elastic material behavior for both concrete and steel, which does not capture nonlinear cracking, tension-softening, or post-cracking stiffness degradation near the transverse crack.

Furthermore, only environmental loading scenarios were applied, with traffic loading excluded from the simulations. As a result, the model does not represent the interaction between wheel loads, slab curling, and crack opening, and this may limit the interpretation of long-term field performance. In addition, the support conditions beneath the slab were idealized as elastic foundation, and did not incorporate moisture gradients, nonuniform base stiffness, or base erosion, all of which can affect slab movement and the stress and strain distributions that develop over time.

Finally, the results presented here correspond to Phase 1 of an ongoing study and will be validated in Phase 2 through field measurements of steel strain, crack width, crack movement, temperature gradients, and load-transfer efficiency on full-scale instrumented test sections. The findings should therefore be considered preliminary.

5. Summary and Conclusions

This study presents a preliminary mechanistic evaluation of two-mat reinforcement layouts in CRCP using detailed three-dimensional finite-element models. A total of 2160 simulations were performed to examine the effect of steel depth, spacing, slab thickness, and environmental loading on steel stress, concrete stress, and crack width. Regular and alternate steel layouts were evaluated. The alternate layout reduces reinforcement in the bottom mat while increasing it in the top layer to enhance restraint against concrete volume changes near the surface, where environmental loading is most severe. The thermal environment was realistically modeled, and responses were evaluated at seven critical points within the slab. Based on structural capacity and serviceability criteria, performance thresholds were established and used to screen all configurations. Comparisons with TxDOT’s current design standard revealed that several alternate layouts outperformed or matched the current configuration in stress control and crack behavior, while requiring less total steel. The selected configurations are expected to optimize performance by offering more restraint where temperature and moisture variations are more severe (near the top) and reducing unnecessary steel where restraint demand is lower (bottom of the slab). Based on the findings from this study, steel configurations for a two-mat design were developed and will be incorporated into the field experiment. The microscopic behavior of the CRCP system, as affected by these various steel configurations as well as environmental loading and concrete material properties, will be evaluated using various sensors. The results collected will then be analyzed to validate the findings made in the FEM analysis. The following conclusions are drawn from this study:

The top layer of steel experiences the highest tensile stress under thermal loading, particularly under negative temperature gradients that induce upward slab curling.

Increases in CoTE, temperature drop from setting, and crack spacing all lead to higher steel stress, wider crack widths, and greater stress in surrounding concrete.

Top-layer-focused configurations evaluated in this study reduced bottom steel and increased reinforcement near the surface, where temperature and moisture variations are most severe. These designs remained within performance limits and compared favorably to the current TxDOT standard, while requiring less total steel.

Once field validation is complete, the recommended steel design is expected to reduce steel and concrete stresses and result in narrower crack widths. Overall, the selected steel configurations should improve structural performance while reducing material use and costs through lower steel reinforcement requirements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-W.B., J.H.Y. and M.W.; methodology, S.A., R.C., S.-W.B., J.H.Y. and M.W.; software, S.A. and R.C.; validation, S.-W.B. and J.H.Y.; formal analysis, S.A. and R.C.; investigation, S.A., R.C., S.-W.B., J.H.Y. and M.W.; resources, J.H.Y. and M.W.; data curation, S.A. and R.C.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A. and R.C.; writing—review and editing, S.A., R.C., S.-W.B., J.H.Y. and M.W.; visualization, S.A. and R.C.; supervision, S.-W.B., J.H.Y. and M.W.; funding acquisition, J.H.Y. and M.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Texas Department of Transportation, grant number 0-7206.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Choi, S.; Won, M. Horizontal Cracking in Continuously Reinforced Concrete Pavements; Report No. FHWA/TX-11/0-5549-3; Texas Tech University: Lubbock, TX, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rouzmehr, F.; Bae, S.-W.; Won, M. Reinforcement design optimisation for continuously reinforced concrete pavement: One-mat vs. two-mat. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2023, 24, 2273325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalade, S.; Koirala, N.; Dangal, N.; Shakya, B.; Won, M. Performance comparison of single-mat and two-mat steel designs in thick CRCP. In Proceedings of the 2nd Annual Research Day, Lubbock, TX, USA, 9 February 2025; Texas Tech University Whitacre College of Engineering (WCOE): Lubbock, TX, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/388861806 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Abadin, M.; Roy, S.; Wei, Z.; Rahman, M. First experiences with continuously reinforced concrete pavement in national highway of Bangladesh. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2023, 18, 114–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Texas Department of Transportation. CRCP(2) 24: Continuously Reinforced Concrete Pavement: Two Layer Steel Bar Placement; Texas Department of Transportation: Austin, TX, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Roesler, J.; Hiller, J.; Brand, A. Continuously Reinforced Concrete Pavement Manual: Guidelines for Design, Construction, Maintenance, and Rehabilitation; Report No. FHWA-HIF-16-026; U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Moharekpour, M.; Hoeller, S.; Oeser, M. Crack behavior of continuously reinforced concrete pavements (CRCP) in Germany. In Eleventh International Conference on the Bearing Capacity of Roads, Railways and Airfields; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Koirala, N.; Rouzmehr, F.; Jabonero, C.; Won, M. Optimizing Reinforcing Steel in 12-in and 13-in Continuously Reinforced Concrete Pavement (CRCP); Research Report No. 0-7026; Texas Tech University, Multidisciplinary Research in Transportation: Lubbock, TX, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. Pavement Analysis and Design, 2nd ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Desai, P. Drying shrinkage behaviour of foam-cement panel: A numerical study. In Proceedings of the Navrachana University National Conference on Innovating for Development and Sustainability, Vadodara, India, 30–31 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, S.-I.; Choi, P.; Won, M. Punchout evaluations and classification of continuously reinforced concrete pavement to improve pavement design. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2021, 22, 1481–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACI CODE-318-19(22); Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete and Commentary. American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2022.

Figure 1.

Restraint of steel on CRCP movement at transverse crack [

1].

Figure 1.

Restraint of steel on CRCP movement at transverse crack [

1].

Figure 2.

Regular and alternate geometries in ANSYS. (a) “Regular” steel layout; (b) “Alternate” steel layout.

Figure 2.

Regular and alternate geometries in ANSYS. (a) “Regular” steel layout; (b) “Alternate” steel layout.

Figure 3.

Typical geometry with 1.2 m crack spacing, showing planes of symmetry.

Figure 3.

Typical geometry with 1.2 m crack spacing, showing planes of symmetry.

Figure 4.

Temperature gradients. (a) Positive temperature gradient; (b) negative temperature gradient.

Figure 4.

Temperature gradients. (a) Positive temperature gradient; (b) negative temperature gradient.

Figure 5.

Superposition of shrinkage-induced temperature drop.

Figure 5.

Superposition of shrinkage-induced temperature drop.

Figure 6.

Mesh model adopted in the FEA.

Figure 6.

Mesh model adopted in the FEA.

Figure 7.

Steel stress at transverse cracks.

Figure 7.

Steel stress at transverse cracks.

Figure 8.

Principal stress in concrete at transverse crack face.

Figure 8.

Principal stress in concrete at transverse crack face.

Figure 9.

Longitudinal displacement at steel depth for crack width estimation.

Figure 9.

Longitudinal displacement at steel depth for crack width estimation.

Figure 10.

Steel stress variations with environmental changes. (a) Positive gradient—regular; (b) negative gradient—regular; (c) positive gradient—alternate; (d) negative gradient—alternate.

Figure 10.

Steel stress variations with environmental changes. (a) Positive gradient—regular; (b) negative gradient—regular; (c) positive gradient—alternate; (d) negative gradient—alternate.

Figure 11.

Crack width variations with environmental changes. (a) Positive gradient—regular; (b) negative gradient—regular; (c) positive gradient—alternate; (d) negative gradient—alternate.

Figure 11.

Crack width variations with environmental changes. (a) Positive gradient—regular; (b) negative gradient—regular; (c) positive gradient—alternate; (d) negative gradient—alternate.

Figure 12.

Variations in stresses in concrete surrounding steel. (a) Positive gradient—regular; (b) negative gradient—regular; (c) positive gradient—alternate; (d) negative gradient—alternate.

Figure 12.

Variations in stresses in concrete surrounding steel. (a) Positive gradient—regular; (b) negative gradient—regular; (c) positive gradient—alternate; (d) negative gradient—alternate.

Figure 13.

Variation of steel stress with steel spacing. (a) Top steel stress; (b) bottom steel stress.

Figure 13.

Variation of steel stress with steel spacing. (a) Top steel stress; (b) bottom steel stress.

Figure 14.

Crack width at depth of top steel.

Figure 14.

Crack width at depth of top steel.

Figure 15.

Effect of steel spacing on stress in concrete surrounding steel. (a) Stress in concrete surrounding top steel; (b) stress in concrete surrounding bottom steel.

Figure 15.

Effect of steel spacing on stress in concrete surrounding steel. (a) Stress in concrete surrounding top steel; (b) stress in concrete surrounding bottom steel.

Figure 16.

Variation of steel stress with bottom steel depth. (a) Top steel stress; (b) bottom steel stress.

Figure 16.

Variation of steel stress with bottom steel depth. (a) Top steel stress; (b) bottom steel stress.

Figure 17.

Variation of crack width at top steel depth with bottom steel depth.

Figure 17.

Variation of crack width at top steel depth with bottom steel depth.

Figure 18.

Effect of bottom steel depth on stress in concrete surrounding steel. (a) Stress in concrete surrounding top steel; (b) stress in concrete surrounding bottom steel.

Figure 18.

Effect of bottom steel depth on stress in concrete surrounding steel. (a) Stress in concrete surrounding top steel; (b) stress in concrete surrounding bottom steel.

Figure 19.

Comparison between regular and alternate models under critical conditions. (a) Top steel stress; (b) bottom steel stress; (c) crack width; (d) maximum stress in concrete surrounding steel.

Figure 19.

Comparison between regular and alternate models under critical conditions. (a) Top steel stress; (b) bottom steel stress; (c) crack width; (d) maximum stress in concrete surrounding steel.

Figure 20.

Process for selecting optimum reinforcement configuration.

Figure 20.

Process for selecting optimum reinforcement configuration.

Figure 21.

Visualization of filtering process.

Figure 21.

Visualization of filtering process.

Figure 22.

Performance filtering based on response limits under critical conditions. (a) 356 mm CRCP; (b) 381 mm CRCP.

Figure 22.

Performance filtering based on response limits under critical conditions. (a) 356 mm CRCP; (b) 381 mm CRCP.

Figure 23.

Comparison of selected configurations to current design. (a) 356 mm—positive temperature gradient; (b) 356 mm—negative temperature gradient; (c) 381 mm—positive temperature gradient; (d) 381 mm—negative temperature gradient.

Figure 23.

Comparison of selected configurations to current design. (a) 356 mm—positive temperature gradient; (b) 356 mm—negative temperature gradient; (c) 381 mm—positive temperature gradient; (d) 381 mm—negative temperature gradient.

Table 1.

Two-mat reinforcement configuration for 356 mm and 381 mm CRCP [

5].

Table 1.

Two-mat reinforcement configuration for 356 mm and 381 mm CRCP [

5].

| Steel Parameter | Layer | 356 mm CRCP (mm) | 381 mm CRCP (mm) |

|---|

| Longitudinal Steel Spacing | Top | 241 | 216 |

| Bottom | 241 | 216 |

| Longitudinal Steel Depth from Top | Top | 127 | 140 |

| Bottom | 216 | 229 |

Table 2.

Factorial design for finite-element analysis.

Table 2.

Factorial design for finite-element analysis.

| Variables | Level | Changes in Variables |

|---|

| Slab Thickness (mm) | 3 | 330 | 356 | 381 |

Steel Depth

(mm) | Top | 1 | 127 | 127 | 127 |

| Bottom | 3 | 191/216/241 | 203/229/254 | 216/241/267 |

Steel Spacing

(mm) | Top | 3 | 216/241/267 | 191/216/241 | 165/191/216 |

| Bottom | 2 | Same spacing as top and twice the top spacing |

| CoTE (microstrains/°C) | 2 | 8.1/9.9 |

| Temperature Variation (°C/cm) | 2 | 0.7/−0.3 |

Temp. Drop from Setting

(°C) to Tdaily,min | 2 | 16.7/27.8 |

| Crack Spacing (m) | 4 | 0.6/1.2/1.8/2.4/3.7 |

| 2160 Cases |

Table 3.

Average differences between alternate and regular models under critical condition.

Table 3.

Average differences between alternate and regular models under critical condition.

| Parameter | |

|---|

| 356 mm CRCP | 381 mm CRCP |

|---|

| Top Steel Stress | 3.9 MPa | 4.6 MPa |

| Bottom Steel Stress | 5.6 MPa | 6.1 MPa |

| Maximum Stress in Concrete at Steel Depth | −0.13 MPa | −0.13 MPa |

| Maximum Crack Width | 4.1 µm | 5.1 µm |

Table 4.

Selected configurations and responses under critical conditions.

Table 4.

Selected configurations and responses under critical conditions.

| No. | Top Bar Depth (mm) | Bot. Bar Depth (mm) | Top Bar Spacing (mm) | Bot. Bar Spacing (mm) | Top Steel Stress (MPa) | Bottom Steel Stress (MPa) | Max. Concrete Stress (MPa) | Max. Crack Width (mm) | Steel Ratio |

|---|

| 356 mm CRCP |

| Existing | 127 | 216 | 241 | 241 | 302 | 255 | 3.32 | 0.336 | 0.66 |

| A | 127 | 203 | 191 | 381 | 299 | 258 | 3.19 | 0.33 | 0.63 |

| B | 127 | 229 | 191 | 381 | 301 | 251 | 2.96 | 0.334 | 0.63 |

| 381 mm CRCP |

| Existing | 140 | 229 | 216 | 216 | 303 | 256 | 3.33 | 0.336 | 0.69 |

| A | 127 | 216 | 165 | 330 | 303 | 261 | 2.91 | 0.319 | 0.68 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).