Abstract

Inactivity is a major issue that causes physical and psychological health problems, especially in people with intellectual disability (ID). This review discusses the beneficial effects of sport intervention programs (SIPs) in people with ID, and aims to provide an overview of the scientific literature in order to identify the main factors influencing the participation of people with ID in SIPs. Twelve papers were analyzed and compared. The results show a large variety in examined SIPs, concerning participants’ age and disability, intervention characteristics and context, as well as measures and findings. The main factors essential for people with ID partaking in SIPs appeared to be suitable places for the SIP development, adequate implementation of physical activity (PA) programs in school and extra-school contexts, education, and the training of teachers and instructors. The literature review highlights the relevance of using SIPs in order to improve physical and psychological health, as well as increase social inclusion in populations with ID. SIPs should be included in multifactor intervention programs. Nevertheless, the need is recognized for stakeholders to adopt specific practice and policy in promoting social inclusion in order to organize intervention strategies which are able to provide quality experiences in sport and physical activity for people with ID.

1. Introduction

Physical activity (PA) is a critical behavior for maintaining and improving health during one’s lifespan. A number of positive effects of PA in persons with intellectual disability (ID) include improvements in general health, such as physical fitness, bone metabolism, increased cardiovascular and respiratory muscle functions, and the control/prevention of obesity and coronary artery disease. Benefits in the social domain include functional independence and social inclusion, and benefits to psychological well-being include the increase of self-esteem, self-competence, self-efficacy, and positive self-perception [1,2,3,4].

Moreover, a large amount of research has recognized a close relationship between regular PA and brain development, particularly in the prefrontal cortical area. Several explanations for this association can be put forth: regular sport exercise programs have positive effects on the production of neurotrophins, synaptogenesis, and angiogenesis with the consequent enhancement of cognitive performance, such as the speed of information processing, working memory, planning, and behavior control strategies [5].

Following evidence from these studies, researchers and practitioners have worked to implement sport intervention programs (SIPs) aimed at obtaining the abovementioned beneficial effects for atypical populations, such as those with ID [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13].

Definition of Terms: From Physical Activity (PA) to Adapted Physical Activity (APA) and Sport Intervention Programs (SIPs)

The difference between PA and adapted physical activity (APA) is crucial to better understanding the health benefits for people with ID. PA is defined as “any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure” (www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity). This includes leisure, exercise, and work activities, and is based on fundamental motor skills development (walking, catching, running, throwing, etc.) [14,15]. Although the World Health Organization recommends at least 60 min of moderate to vigorous-intensity PA daily for ages ranging from 5–17 years, 150 min of moderate-intensity aerobic PA within a week for ages ranging 18–64 and above, a large number of individuals with ID are not meeting these recommendations [16]. Excluding famous examples of PA in people with disabilities (e.g., the Special Olympics (SO)), a broad gap between programs by the Special Olympics and noncompetitive sport programs has been demonstrated. There is a need to develop and implement intervention actions and educational strategies to enhance fitness levels in daily living as well as to motivate people with ID to participate in regular exercise at home and in educational settings [17].

An inactive lifestyle contributes to heightened clinical diseases and the increase of health-related complications such as higher accumulation of bone mass, type II diabetes, and functional motor impairment. Following the European Association for Research into Adapted Physical Activity, APA is a “cross-disciplinary body of practical and theoretical knowledge directed toward impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions in physical activity” (www.ifapa.net). The main aim is to allow and support the acceptance of individual differences and advocate enhanced access to active lifestyles and sport in people with special needs. This involves a variety of professional areas, such as physiotherapy, occupational therapy, motor rehabilitation, pediatrics, recreation, and psychology [12,15,18,19,20,21].

Nevertheless, sport intervention programs (SIPs) can be considered a subtype of APA; their specific characteristic is to emphasize the sport components. SIPs focus on several different sport activities, such as swimming, martial arts, cycling, movement and dance, strength, agility, and balance tasks. They are increasingly used in association with conventional methods of physiotherapy or medical interventions in people with ID [22,23,24]. The characteristics of a specific disability determine the nature of the SIP. For example, for children with autism spectrum disorder, water sports are considered a suitable exercise [25,26,27], while for individuals with Down Syndrome, the most used SIPs consist of cycling, movement and dance, strength and agility, and balance training [28]. Nevertheless, SIPs have been revealed to be especially suitable to enhance socialization by creating an inclusive environment that accommodates individual differences. Sport is a natural context that triggers social interactions and sophisticated behaviours in addition to providing proper scaffolding during cooperation [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37].

However, these beneficial effects are threatened by high levels of inactivity that were found in numbers of the population with ID. Lower rates of participation in PA, in community-based sports, and in exercise programs compared to a typical development (TD) population are described in the literature. This difference is due to many reasons [38,39,40]. Often, health conditions limit their participation; physical impairment and difficulties in motor skills such as walking, running, jumping, standing, or maintaining body control are often reported [19]. Moreover, environmental barriers and lack of appropriate motivational resources impair compliance with these programs [41]. Other barriers include personal characteristics such as age, gender, motor and cognitive proficiency, and the severity of the disability. Lower intellectual abilities can reduce the ability to comprehend the exercise procedures, to plan goal-directed behaviors, and to continue exercise protocols over time. Furthermore, family overprotection towards their children, worries about clinical characteristics, as well as family socioeconomic status and availability of transportation decrease or limit the engagement of people with ID in sport programs. In summary, participation in sport programs decreases in variety, frequency, and duration with age, in coherence with higher levels of loneliness in adult age for people with ID.

Based on these theoretical considerations, this review aims to provide an overview of the scientific literature in order to identify the main factors that influence the participation in sport intervention programs (SIPs) in people with ID in the age range from 6 to 60 years.

2. Materials and Methods

The PRISMA method was followed for the review methodology and data extraction [42,43,44]. A protocol for this review was registered on PROSPERO in January 2018 (PROSPERO registration number CRD42018081672). The registration number is available at http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO.

2.1. Participants

Studies using SIPs in people with ID and chronological age between 6 and 60 years were considered. The age range from 6 to 60 years was established because the engagement in sport activities above or below these developmental phases is scarce in the population with ID. Moreover, the broad age range was a forced choice because of the paucity of studies on sport interventions among individuals with ID. In detail, 24 papers were analyzed.

2.2. Procedure

To identify the literature, the following databases were searched: PsycInfo, ERIC Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science, MEDLINE, and EBSCO. The search for electronic literature databases was dated from January 1998 to February 2018. In order to ensure that no relevant studies were missed, additional studies were identified by hand-searching the reference lists of reviews and research papers. The literature search was exclusively in the English language.

Missing papers were requested from study authors by e-mail. In each database, the following terms were searched: social inclusion, equal opportunities, ID and special needs, APA, PA, SIP. Their synonyms were identified. Duplicates and irrelevant records were eliminated. Remaining records were independently screened by two review authors to identify studies that potentially met the inclusion criteria as outlined below.

The following inclusion criteria were adopted:

- studies described SIPs in people with ID;

- cross-sectional, cohort, experimental, and quasi-experimental;

- peer-reviewed studies;

- people with ID aged between the ages of 6 and 60.

The following exclusion criteria were adopted:

- studies were not published in the English language;

- studies were published before 1998;

- studies were not peer-reviewed;

- qualitative studies;

- grey literature, e.g., dissertations, conference abstracts, research reports, chapter(s) from a book, Ph.D. theses, reports on ID guidelines.

2.3. Data Analysis

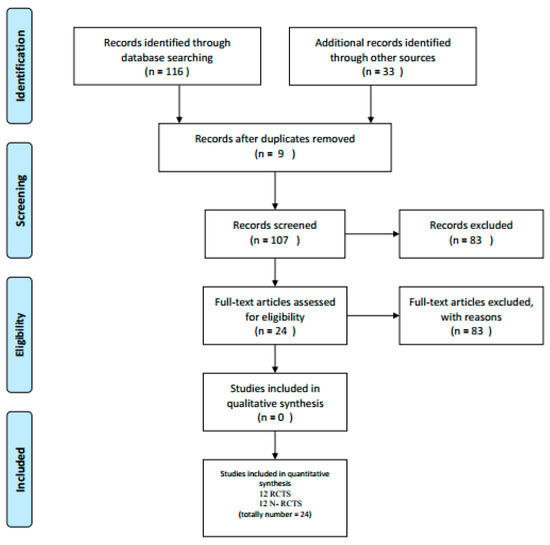

The initial database search identified a total of 116 papers; after a careful selection, according to the PRISMA checklist and inclusion criteria, 24 papers were analyzed for the data extraction. Figure 1 shows the flow diagram following the models of Liberati [44] and Moher et al. [45,46].

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for the selection of papers to be included in the review.

Table 1 and Table 2 present a summary of the following extracted information: Reference (Title and Country), Source (Author and Year), Study Population (Age and Sample Size), Aim of the Study, Intervention (Program), Outcome (Measures), Results and Discussion (Main issues), Quality Assessment.

Table 1.

Randomized controlled trial study (RCTS): papers analyzed in order of publication year.

Table 2.

Non-randomized controlled trial study (N-RCTS) papers analyzed in order of publication year.

The papers’ methodological quality and the risk of bias of the reviewed studies were assessed through a 14-item quantitative checklist, as described in Table 3 [47]. The items concerned questions and methods description, outcome assessment, and conclusions. For each item, studies were scored with yes = 2, partial = 1, no = 0, or not specified (NS) when necessary. Papers were independently analyzed by two reviewers to carry out data extraction, and disagreements were discussed with a third reviewer. The results of the methodological quality evaluation were achieved as a percentage of relevant items. Fifty percent was considered as the cut-off of acceptable methodological quality (+50%) or low methodological quality (−50%).

Table 3.

Quality assessment checklist.

3. Results

The studies included in this systematic review were found to fall in one of two research methods: randomized controlled trial design (RCTD) and non-randomized controlled trial design (N-RCTD). So, they were summarized separately (Table 1 and Table 2). In detail, 12 papers used an RCTD and 12 papers used an N-RCTD. The first ones were studies in which participants were randomly allocated into the intervention or control groups, while studies in the N-RCTD group were experimental studies without participants’ random allocation to intervention or control condition [48]. Concerning RCTD studies, eight had a methodological quality higher than 50% and four had a methodological quality lower than 50%. Regarding N-RCTD studies, nine had a methodological quality higher than 50% and three studies had a methodological quality lower than 50%.

Nevertheless, in terms of methodology, the studies covered a wide range of characteristics (e.g., participants’ age and disability, intervention characteristics, intervention context, and measures). Therefore, a narrative synthesis of results was carried out.

In the RCTD studies that were addressed to adults, two types of measures were mainly used before and following the training period: 1. physical measures with parameters such as aerobic and anaerobic capacity, functional walking capacity, agility, muscle strength, body mass index, and motor skills; 2. well-being measures such as self-perception, self-competence, and self-esteem [38,39,49,50]. Moreover, measures of social inclusion were used: working together, creating cooperative interdependence and participation [51]. Intervention programs ranged from active lifestyle stimulation, counseling on daily PA and physical fitness training, to sport activities such as dance, swimming, and martial arts to improve participation, functioning, and health-related outcomes [52]. For children and adolescents, the parameters were physical fitness and participation associated with enjoyment [40,52]. Interventions were revealed to be quite effective in improving participation and compliance. However, in studies by Andriolo et al. [15], Slaman et al. [53], and Matthews et al. [54], the interventions were not effective in significantly increasing levels of PA. Their quality assessment is low.

Concerning sport activities, the most used sport programs were: training to improve muscle strength, muscle endurance, physical functioning, lifestyle intervention and fitness training, aerobic exercise training, Walk Well intervention, and swimming programs. N-RCTD in adults showed positive outcomes combining physical fitness and psychosocial well-being. Physical fitness measures included walking capacity, muscular endurance and strength, flexibility, cardiorespiratory health, and functional independence. Psychosocial well-being outcomes such as exercise self-efficacy, higher life satisfaction, self-efficacy, and confidence were increased [14,55,56,57,58].

Following the aquatic program, physical fitness parameters such as cardio-respiratory endurance, strength, functional mobility, as well as skills in specific sport domains, such as aquatic proficiency [29,59,60], were used to measure the intervention effectiveness. Aquatic intervention programs were especially suitable for children [28,57,58,61]. Two studies used measures of cognitive abilities such as working memory, attention and visual–perceptual skills and executive functions [5,60,62].

Overall, the most used sport programs were: fitness and health education programs, physical training, and aquatic exercise program.

4. Discussion

This review aimed to provide an overview of the scientific literature in order to identify the main factors influencing participation in sport intervention programs (SIPs) in people with ID. Recently, there has been an increased interest in sport programs addressed to individuals with ID given the sport educational values and their efficacy in improving physical and mental health [20,36,37,42,63].

The reviewed studies showed how, for individuals with ID, sport programs positively affect the quality of life and community participation, such as satisfaction with professional services, home life, daily activities, dignity and rights, respect from others, feelings, choice, control, and family satisfaction [33,34,35]. Individuals with ID who regularly attended SIPs reported having higher opportunities for social interactions and more frequent outings into the community than sedentary peers [50,55,64]. In detail, SIPs were: training improving muscle strength, muscle endurance, physical functioning, lifestyle interventions, Walk Well intervention, swimming programs, health education programs, physical training, and aerobic and aquatic exercise programs.

Despite a wide variety of methodological variables such as participants’ age and disability, intervention characteristics, context, and measures, the main factors essential for the people with ID experiencing SIPs were revealed to concern suitable places for the SIP development, adequate implementation of PA programs in the school and extra-school contexts, and the education and training of teachers and instructors. Studies underlined the importance of providing access to physical exercise for people with ID through recreational and competitive sport and physical education curricula [20,22,36,37,42].

Enjoyable interventions and appealing settings are recommended to increase the repertoire of leisure skills and the level of PA in children and adolescents with ID [1,2,3,4,40,52,65]. Nevertheless, a wide range of personal factors was identified to influence the participation in PA in the lifespan. These concerned person’s disability characteristics (e.g., intellectual level, motor proficiency, social and communication competences) [49,62]. For example, the Walk Well treatment/intervention was not effective in increasing the level of PA in children with DS [54], while it was effective for other kinds of ID [49,52]. Moreover, personal factors included personal knowledge and information, interest and inclination, motivation, physical literacy skills, attitudes, and beliefs. These personal factors were influenced by interactions with socio-cultural factors at the levels of home, workplace, and community. The SIP delivery in school and extra-school contexts appeared to be essential to increase sustainable participation in PA and sport. This is because in early life and at young ages, the school is considered to be an authoritative educational agency and the privileged place of literacy to the sport.

Moreover, inclusive education involves a person-centered, inter-cultural, and integrated educational approach that validates the experience at any age. For example, the use of group-based programs where adults with ID performed exercises together increased the program effectiveness in terms of costs and time [6,7,8,11,12,13,50,65].

Furthermore, the education and training of teachers and instructors are crucial to address individual needs and to plan targeted intervention programs matching the specific skills of people with ID. Expert instructors and coaches play a key role in initiating and maintaining the participation in SIPs over the time by all people given their specific education, knowledge, and awareness of strategies to favor the inclusion of people with ID.

Finally, regarding methodological aspects, 12 reviewed articles were used a RCTD and 12 used a N-RCTD. The former had the highest level of evidence because randomization allows bias to be limited and offers a rigorous instrument to investigate cause–effect links between intervention and results. However, in the population with ID, N-RCTD studies may enclose important and useful information on clinical course and prognosis, even though they provide a lower level of evidence [66]. The elevated inter-individual variability that characterizes people with ID often requires quasi-experimental or case reports studies. This was the case of the present review, showing how in many cases a great deal of preliminary educational and clinical information can be derived from studies without a control group or studies carried out on narrow groups.

5. Conclusions

Sport activities provide great opportunities through the medium of movement, and contribute to the overall development of individuals with ID, with the final outcome of improving and maintaining both mental and physical health. The growing emphasis on the key role of PA and sport in promoting wellbeing and social inclusion in people with ID is supported by the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health [67], which highlights the close relationship between body, person, and society as components characterizing human functioning, both in health and in disability conditions.

Government programs must ensure equal opportunities between people who have different disabilities and those with typical development during the life span through good practice and policy. Thus, people with ID must have the same opportunities for social inclusion as people with typical development. Indeed, SIPs have been recognized as a promising tool to promote social inclusion. High-quality sports programs offer people with ID a possibility to change lifestyle and personal perceptions in terms of wellbeing and the promotion of individual differences. From a methodological perspective, the analysis of differences between RCTD and N-RCTD studies showed the importance of implementing intervention programs with specific and structured research designs. An appropriate research design intervention—especially following a RCTD that supports evidence-based intervention programs—allows more effective results to be obtained.

A shortcoming of this review is the large subject age range, from 6 to 60 years. This was for two reasons: 1. the engagement in sport activities above or below these ages was scarce in the population with ID; 2. there is a paucity of studies on sport interventions among individuals with ID.

To summarize, the findings of this review suggest implications on the educational and clinical fields to develop targeted evidence-based programs aiming at improving health and enhancing social inclusion through SIPs. The implementation of these intervention programs needs to account for the specificity of both disability and social/family factors to maximize the maintenance and generalization of improvements to daily living skills. In coherence with these practical implications, future research is needed to examine the the effectiveness of these programs by measuring short- and long-term improvements. Further investigations are therefore recommended to provide a richer and more complete understanding of the direction of the interrelationship between SIPs and traditional intervention methods such as physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and motor rehabilitation. Moreover, it is necessary to gather scientific evidence on the consequences of SIPs in lowering economic health costs deriving from diseases, use of medical services, and welfare assistance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.S., M.A. and A.B.; methodology, all authors; software, L.S.; validation, L.S., C.C.B., D.M. (Diogo Monteiro), D.M. (Doris Matosic), K.F.; formal analysis, L.S., C.C.B., D.M. (Diogo Monteiro), D.M. (Doris Matosic), K.F.; investigation, all authors; resources, L.S., C.C.B., D.M. (Diogo Monteiro), D.M. (Doris Matosic); data curation, L.S., C.C.B., D.M. (Diogo Monteiro), D.M. (Doris Matosic), K.F.; writing—original draft preparation, L.S., M.A.; writing—review and editing, L.S., M.A., K.F.; visualization, all authors; supervision, M.A. and A.B.; project administration, M.A. and A.B.; funding acquisition, M.A. and A.B.

Funding

Erasmus+ Sport Programme (2017–2019) Call EAC/A04/2015 – Round 2 E+ SPORT PROJECT - 579661-EPP-1-2016-2-IT-SPO-SCP “Enriched Sport Activities Program”—Agreement number 2016-3723/001-001.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ogg-Groenendaal, M.; Hermans, H.; Claessens, B. A systematic review on the effect of exercise interventions on challenging behavior for people with intellectual disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2014, 35, 1507–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastebroek, M.; Naaldenberg, J.; Lagro-Janssen, A.L.; Van Schrojenstein Lantman de Valk, H. Health information exchange in general practice care for people with intellectual disabilities—A qualitative review of the literature. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2014, 35, 1978–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairclough, S.J.; McGrane, B.; Sanders, G.; Taylor, S.; Owen, M. A non-equivalent group pilot trial of a school-based physical activity and fitness intervention for 10–11 year oldenglish children: Born to move. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGarty, A.M.; Downs, S.J.; Melville, C.A.; Harris, L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions to increase physical activity in children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2017, 62, 312–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alesi, M.; Battaglia, G.; Roccella, M.; Testa, D.; Palma, A.; Pepi, A. Improvement of gross motor and cognitive abilities by an exercise training program: Three case reports. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2014, 10, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn, E.B.; Ramsey, L.T.; Brownson, R.C.; Heath, G.W.; Howze, E.H.; Powell, K.E.; Stone, E.J.; Rajab, M.W.; Corso, P. The effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity a systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2002, 22, 72–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R. Evaluating the relationship between physical education, sport and social inclusion. Educ. Res. Rev. 2005, 57, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allender, S.; Cowburn, G.; Foster, C. Understanding participation in sport and physical activity among children and adults: A review of qualitative studies. Health Educ. Res. Theory Pract. 2006, 21, 826–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, B.H.; Williams, D.M.; Dubbert, P.M.; Sallis, J.F.; King, A.C.; Yancey, A.K.; Franklin, B.A.; Buchner, D.; Daniels, S.R.; Claytor, R.P.; et al. Physical activity intervention studies: What we know and what we need to know a scientific statement from the american heart association council on nutrition, physical activity, and metabolism (subcommittee on physical activity); council on cardiovascular disease in the young; and the interdisciplinary working group on quality of care and outcomes research. Circulation 2006, 114, 273–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, N.A.; Carbone, P.S.; Council on Children with Disabilities. Promoting the participation of children with disabilities in sports, recreation, and physical activities. Am. Acad. Ped. 2008, 121, 1057–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodde, A.E.; Seo, D.C. A review of social and environmental barriers to physical activity for adults with intellectual disabilities. Disabil. Health J. 2009, 2, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heath, G.W.; Parra, D.C.; Sarmiento, O.L.; Andersen, L.B.; Owen, N.; Goenka, S. Evidence-based intervention in physical activity: Lessons from around the world. Phys. Act. 2012, 3, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dairo, Y.M.; Collett, J.; Dawes, H.; Oskrochi, G.R. Physical activity levels in adults with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review. Prev. Med. Rep. 2016, 4, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, B.C.; Wendy, Y.J.; Huang, W.Y.J.; Choi, P.H.N.; Pan, C.-Y. Design and methods of a multi-component physical activity program for adults with intellectual disabilities living in group homes. J. Exerc. Sci. Fit. 2016, 14, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andriolo, R.B.; El Dib, R.P.; Ramos, L.; Atallah, Á.N.; da Silva, E.M.K. Aerobic exercise training programmes for improving physical and psychosocial health in adults with Down Syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grondhuis, S.N.; Aman, M.G. Overweight and obesity in youth with developmental disabilities: A call to action. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2014, 58, 787–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bota, A.; Teodorescu, S.; Kiss, K.; Stoicoviciu, A. Fitness status in subjects with intellectual disabilities: A comparative studies. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 46, 2078–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lina, J.D.; Lin, P.Y.; Lin, L.P.; Chang, Y.Y.; Ru Wu, S.; Wu, J.L. Physical activity and its determinants among adolescents with intellectual disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2009, 31, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimmer, J.H.; Chen, M.D.; McCubbin, J.A.; Drum, C.; Peterson, J. Exercise intervention research on persons with disabilities: What we know and where we need to go. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2010, 89, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D. Sports-Based intervention as a tool for social inclusion? Seameo sen icse. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Special Education: Access and Engagemen, Sarawak, Malaysia, 31 July–2 August 2017; Institute of Educational Leadership, University of Malaya: Sarawak, Malaysia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Howie, E.H.; Pate, R.R. Physical activity and academic achievement in children: A historical perspective. J. Sport Health Sci. 2012, 1, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simplican, S.C.; Leader, G.; Kosciulek, J.; Leahy, M. Defining social inclusion of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities: An ecological model of social networks and community participation. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 38, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafferty, R.; Breslin, G.; Brennan, D.; Hassan, D. A systematic review of school-based physical activity interventions on children’s wellbeing. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2016, 9, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tercedor, P.; Villa-González, E.; Ávila-García, M.; Díaz-Piedra, C.; Martínez-Baena, A.; Soriano-Maldonado, A. A school-based physical activity promotion intervention in children: Rationale and study protocol for the previne project. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’isanto, T.; Di Tore, P.A. Physical activity and social inclusion at school: A paradigm change. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2016, 16, 109–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Spieth, P.M.; Kubasch, A.S.; Penzlin, A.I.; Illigens, B.M.; Barlinn, K.; Siepmann, T. Randomized controlled trials—A matter of design. Neuropsych. Dis. Treat. 2016, 12, 1341–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudenbush, S.W. On randomized experimentation in education: A commentary on deaton and cartwright, in honor of frederick mosteller. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 210, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funk, M. Physical Activity Interventions for Children with Down Syndrome: A Synthesis of the Research Literature. In Kinesiology Sport Studies, and Physical Education Synthesis Projects; 2017; Volume 32, Available online: https://digitalcommons.brockport.edu/pes_synthesis/32 (accessed on 30 December 2017).

- Verschuren, O.; Ketelaar, M.; Gorter, J.W.; Helders, P.J.M.; Uiterwaal, C.S.P.M.; Takken, T. Exercise training program in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2007, 161, 1075–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.H.; Pan, C.Y. The effect of peer- and sibling-assisted aquatic program on interaction behaviors and aquatic skills of children with autism spectrum disorders and their peers/siblings. Res. Autism Spect. Disor. 2012, 6, 1211–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, C.; Forneris, T. The role of special olympics in promoting social inclusion: An examination of stakeholder perceptions. J. Sport Dev. 2015, 3, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Thorn, S.H.; Pittman, A.; Myers, R.E.; Slaughter, C. Increasing community integration and inclusion for people with intellectual disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2009, 30, 891–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siperstein, G.N.; Glick, G.C.; Parker, R.C. Social inclusion of children with intellectual disabilities in a recreational setting. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2009, 47, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S.A. The Social Inclusion of Young Adults with Intellectual Disabilities: A Phenomenology of Their Experiences. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE, Canada, 2010; p. 18. Available online: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cehsedaddiss/18 (accessed on 30 December 2010).

- Grandisson, M.; Te´treault, S.; Freeman, A.R. Enabling integration in sports for adolescents with intellectual disabilities. J. Appl. Res. Intellec. Disabil. 2012, 25, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McConkey, R.; Dowling, S.; Hassan, S.; Menke, S. Promoting social inclusion through Unified Sports for youth with intellectual disabilities: A five-nation study. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2012, 57, 923–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphrey, N.; Lendrum, A.; Barlow, A.; Wigelsworth, M.; Squires, G. Achievement for all: Improving psychosocial outcomes for students with special educational needs and disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 34, 1210–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lante, K.; Stancliffe, R.J.; Bauman, A.; Van der Ploeg, H.P.; Jan, S.; Davis, G.M. Embedding sustainable physical activities into the everyday lives of adults with intellectual disabilities: A randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2014, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shields, N.; Synnot, A. Perceived barriers and facilitators toparticipation in physical activity for children with disability: A qualitative study. BMC Pediatr. 2016, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaman, J.; Roebroeck, M.E.; Van Meeteren, J.; van der Slot, W.M.; Reinders- Messelink, H.A.; Lindeman, E.; Stam, H.J.; van den Berg-Emons, R.J. 2 Move 16-24: Effectiveness of an intervention to stimulate physical activity and improve physical fitness of adolescents and young adults with spastic cerebral palsy; a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pediatr. 2010, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alesi, M. Investigating Parental Beliefs Concerning Facilitators and Barriers to the Physical Activity in Down Syndrome and Typical Development. SAGE Open 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, D.; Pouesard, M.L.; Rummens, J.A. Defining social inclusion for children with disabilities: A critical literature review. Child. Soc. 2018, 32, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, B.; Young, H.J.; Bickel, C.S.; Motl, R.W.; Rimmer, J.H. Current trends in exercise intervention research, rechnology, and behavioral change ctrategies for people with disabilities: A scoping review. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehab. 2017, 96, 748–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A. The prisma statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epid. 2009, 62, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for Systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The prisma statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kmet, L.; Lee, R.; Cook, L. Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evacuatig Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Felds, 2nd ed.; Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, J.H. The distinction between randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and preliminary feasibility and pilot studies: What they are and are not. J. Orthop. Sports. Phys. Ther. 2014, 44, 555–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melville, C.A.; Mitchell, F.; Stalker, K.; Matthews, L.; McConnachie, A.; Murray, H.M.; Mutrie, N. Effectiveness of a walking programme to support adults with intellectual disabilities to increase physical activity: Walk well cluster-randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elinder, L.S.; Bergström, H.; Hagberg, J.; Wihlman, U.; Hagströmer, M. Promoting a healthy diet and physical activity in adults with intellectual disabilities living in community residences: Design and evaluation of a cluster-randomized intervention. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, E.; Glidden, L.M. Changing attitudes toward disabilities through unified sports. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2014, 52, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, F.; Melville, C.; Stalker, K.; Matthews, L.; McConnachie, A.; Murray, H.; Walker, A.; Mutrie, N. Walk well: A randomised controlled trial of a walking intervention for adults with intellectual disabilities: Study protocol. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slaman, J.; Roebroeck, M.; Dallmijer, A.; Twisk, J.; Stam, H.; Van Den Berg-Emons, R.; Learn 2 Move Research Group. Can a lifestyle intervention programme improve physical behaviour among adolescents and young adults with spastic cerebral palsy? A randomized controlled trial. Dev. Child Neurol. 2014, 57, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, L.; Mitchell, F.; Stalker, K.; McConnachie, A.; Murray, H.; Melling, C.; Mutrie, N.; Melville, C. Process evaluation of the walk well study: A cluster-randomised controlled trial of a community based walking programme for adults with intellectual disabilities. BMC Public Health 2016, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blick, R.N.; Saad, A.E.; Goreczny, A.J.; Roman, K.; Sorensen, C.H. Effects of declared levels of physical activity on quality of life of individuals with intellectual disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 37, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, E.; Zinger-Vaknin, T.; Morad, M.; Merrick, J. Can physical training have anaffecton well-being in adults with mild intellectual disability? Mech. Ageing Dev. 2005, 126, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraro, A.; Gobbi, E. Effects of an exercise programme on anxiety in adults with intellectual disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 33, 1221–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heller, T.; Hsieh, K.; Rimmer, J.H. Attitudinal and psychosocial outcomes of a fitness and health education program on adults with down syndrome. Am. J. Ment. Retard. 2004, 109, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragala-Pinkham, M.; O’Neil, M.E.; Haley, S.M. Summative evaluation of a pilot aquatic exercise program for children with disabilities. Disabil. Health J. 2010, 3, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, C.Y. The efficacy of an aquatic program on physical fitness and aquatic skills in children with and without autism spectrum disorders. Res. Autism Spect. Disor. 2011, 5, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanardag, M.; Erkan, M.; Yılmaz, I.; Arıcan, E.; Düzkantar, A. Teaching advance movement exploration skills in water to children with autism spectrum disorders. Res. Autism Spect. Dis. 2015, 9, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.D.; Tsai, H.Y.; Wang, C.C.; Wuang, Y.P. The effectiveness of racket-sport intervention on visual perception and executive functions in children with mild intellectual disabilities and borderline intellectual functioning. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2015, 11, 2287–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, N.; Taylor, N.F.; Dodd, K.J. Effects of a Community-Based Progressive Resistance Training Program on Muscle Performance and Physical Function in Adults With Down Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2008, 89, 1215–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wely, L.V.; Becher, J.G.; Reinders-Messelink, H.R.; Lindeman, E.; Verschuren, O.; Verheijden, J.; Dallmeijer, A.J. Learn 2 move 7-12 years: A randomizedcontrolled trial on the effects of a physical activity stimulation program in children with cerebral palsy. BMC Pediatric 2010, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, D.A.; Burghardt, A.R.; Lloyd, M.; Tiernan, C.; Hornyak, J.E. Physical Activity Benefits of Learning to Ride a Two-Wheel Bicycle for Children With Down Syndrome: A Randomized Trial. Phys. Ther. 2011, 10, 1463–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sackett, D.L. Rules of evidence and clinical recommendations on the use of antithrombotic agents. Chest 1989, 95, 2S–4S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Healt: ICF; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001; Available online: http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en (accessed on 30 December 2017).

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).