Abstract

Current traditional tea processing production lines suffer from issues such as fragmented data and low levels of intelligence. This paper proposes a three-dimensional visualization system for tea processing production lines based on digital twins. Firstly, the system’s overall framework and functional architecture were established. Secondly, multi-source heterogeneous data from the production line was collected and managed through a driver architecture, enabling the construction and mapping of the digital twin information model. Thirdly, referencing the actual environment of a green tea processing line, scene-specific lighting models and rendering techniques were employed to recreate a virtual green tea processing environment. During this process, lighting optimization enhanced the realism of the system’s scenes. Finally, employing data-driven methodologies, the system dynamically simulates the operational states of various production line equipment and the morphological changes in tea leaves. This achieves comprehensive three-dimensional visualization and all-round monitoring of the tea processing production line. Experimental validation confirms the feasibility of this visualized 3D system, injecting fresh impetus into advancing intelligent tea production.

1. Introduction

Tea possesses rich nutritional value and is an indispensable part of daily life for most Chinese people [1,2]. Tea processing production lines are crucial to tea production, and optimizing and upgrading these lines directly impacts tea quality and production efficiency [3,4]. However, current tea processing production lines exhibit shortcomings in meeting market demands and ensuring product quality. Non-standardized data storage methods lead to fragmented and dispersed information, disrupting production line operations and hindering comprehensive monitoring and precise analysis [5]. Furthermore, the lack of transparency regarding real-time operational status of processing equipment impedes seamless collaboration between production stages, limiting overall efficiency gains. Therefore, a multidimensional approach is required to develop a three-dimensional visualization system for tea processing production lines, thereby upgrading these lines and promoting the sustainable development of the tea industry.

Digital twin technology is a crucial component for achieving three-dimensional visualization of tea processing production lines [6]. In recent years, an increasing number of scholars have focused on researching the theoretical framework of digital twin systems. Jia W proposed an innovative multi-scale, multi-scenario digital twin modeling approach for complex applications in variable work environment scales. The approach provides an implementable method to construct a complex model of digital twin [7]. Parle D examined nearly a hundred digital twin case studies, conducted a comprehensive evaluation of various digital twin platforms, and proposed a three-tier platform selection framework [8]. Vodyaho A focused on the challenges of implementing runtime digital twins and proposed a reference architecture for dynamic runtime digital twins. The method provides valuable reference for experts engaged in the research and development of various information systems [9]. Singh M examined the performance of various digital twin platforms in creating precise dynamic data replicas, providing a basis for developers and organizations to select digital twin platforms [10]. Currently, digital twin technology can be practically applied across multiple fields. Tao F analyzes the Digital Twin-Driven Product Design (DTPD) framework, proposes a novel product design approach based on digital twin methodology, and illustrates its practical application through case studies [11]. Zhu Z proposed an intelligent monitoring system for robotic milling process based on transfer learning and digital twin. The proposed monitoring system for robotic milling process demonstrates great virtual-real mapping [12]. Zhang H discussed the specific procedures and methods of model assembly, model fusion, respectively, based on digital twin. A satellite AIT(Assembly, Integration and Test) is chosen as the case to validate the correctness and feasibility [13]. Ling Tian analyzed construction methods for production line digital twins and established an interaction mechanism between the physical and information spaces of production lines [14]. Yixiong Wei designed a prototype system based on key technologies for collecting and managing multi-source heterogeneous data, providing a case study for digital twin technology applications in intelligent manufacturing [15]. Jihong Yan studied the architecture of digital twin workshop model based on state transition in big data environment. Using a non-standard aerospace product machining process as an example, the effectiveness of the proposed model is proved [16]. Zhang X proposed a digital twin-driven in-process monitoring system for the ultrasonic vibration-assisted milling process. The fundamental architecture is established from the digital twin model for real-time motion control, real-time material removal procedure simulation, during the ultrasonic vibration-assisted milling process [17]. Catherine proposed a design framework for module coupling mechanisms, demonstrating modular design advantages through applications in reconfigurable factories [18]. Hao Zhang investigated multi-objective optimization methods for insulating glass production lines, integrating system modeling with distributed real-time process data to enable pre-production data evaluation [19]; Yuval proposed a hierarchical structure for temporarily connecting digital twin production, implementing a modular design for digital twin product assembly line systems [20]. Practical applications of digital twin technology are primarily concentrated in industrial production. Through the monitoring and control enabled by digital twin technology, industrial production efficiency has been enhanced.

Visualization systems are rarely applied in agricultural production, with few cases integrating digital twin systems with agriculture. The production status of agricultural products is not effectively monitored. This paper proposes a three-dimensional visualization system based on digital twins for green tea production lines. Within this visualization system, equipment and tea leaf status throughout the production line undergo full-process monitoring, fulfilling the visualization requirements for tea processing lines. This work provides a new case study for the application and development of digital twin technology in the agricultural product processing sector.

The rest of this study is organized as follows: First, the overall framework of the tea three-dimensional visualization system is discussed in Section 2.1. Section 2.2 focuses on data acquisition and scene optimization for tea production lines. Section 2.3 presents the dynamic simulation process of tea processing production lines based on digital twins. Second, test results are presented and discussed from various perspectives. Finally, conclusions are provided in Section 4.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overall Framework of the 3D Visualization System

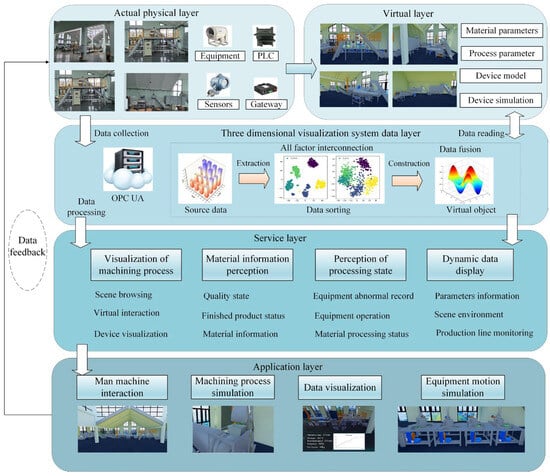

Based on the five-dimensional digital twin model [21], the three-dimensional visualization system architecture is divided into five layers: the physical layer, virtual layer, data layer, service layer, and application layer. These layers interact to form a closed-loop system, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overall framework of the tea production line 3D visualization system.

The physical layer provides the visualization system with data related to the tea processing workflow, encompassing tea processing equipment, sensors, Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs), and other components. The generation and collection of multi-source heterogeneous data during tea processing occur at the physical layer, forming the foundational prerequisite for the system’s normal operation. The virtual models within the virtual layer are established as three-dimensional representations based on actual tea production line scenarios, evolving dynamically across different stages of tea processing. The behavior rules of virtual equipment are defined based on the actual processing actions of physical equipment on the production line, achieving a true mirror mapping from physical to virtual equipment. The function of the data layer is to process multi-source heterogeneous data from the production line. This heterogeneous data can originate from various sensors on different tea processing equipment, such as signals for heating temperature, humidity, rotational speed, and pressure. It can also come from tea state data, including heating temperature, material feed rate, and material form. Utilizing the system’s data transmission module, the data layer employs the Open Platform Communications Unified Architecture (OPC UA) to extract and store real-time data from the physical layer. For tea processing equipment lacking data interfaces, data is obtained through deployed sensors. Data transmission is ultimately achieved via gateways. The service layer integrates the physical production line, virtual production line, and digital twin data. Within this layer, a three-dimensional visualization platform for tea processing is established, enabling process visualization, transparent processing status, and intelligent equipment management. The application layer integrates the physical production line, virtual production line, service layer, and digital twin data, achieving three-dimensional visualization of the tea production line and physical motion simulation of processing equipment. Additionally, triggered signals enable virtual monitoring of production line information, fulfilling user requirements for production line traceability analysis and real-time monitoring.

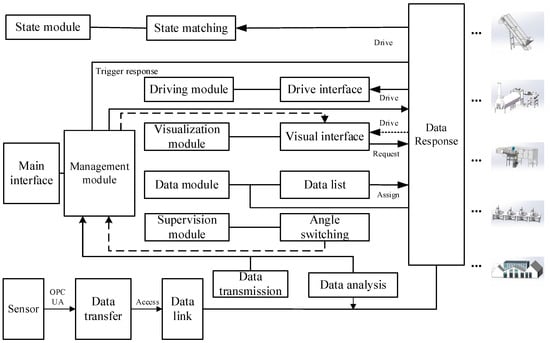

Based on the overall framework of the tea production line 3D visualization system, the functional architecture has been successfully established, as shown in Figure 2. The tea processing production line 3D visualization system is a modular system. Each module operates relatively independently. Maintenance of any single module does not affect others, enabling the addition or modification of functions as needed.

Figure 2.

System functional architecture.

2.2. Production Line Data Acquisition and Scenario Optimization

2.2.1. Multi-Source Heterogeneous Data Acquisition

Multi-source heterogeneous data primarily originates from various tea processing equipment, sensors, and control systems. This system leverages the OPC UA communication protocol to acquire real-time information from the tea production line in a standardized, secure, and efficient manner. Data is collected asynchronously by establishing connections between OPC UA clients and servers configured with data source devices. Key parameters such as temperature, humidity, flow rate, and mass are obtained in real time [22]. Data is not only utilized for production process monitoring but also stored in a local database for subsequent product quality analysis. Physical layer device data is uniformly collected and distributed using PLCs. Data upload is achieved through an OPC UA gateway. For devices or data inaccessible via PLC—including specific sensors, standalone processing equipment without interfaces, and inspection devices—data acquisition employs serial port access, WebSockets, and input/output port parsing, with results consolidated into a unified data list. This paper employs an event-driven mechanism to reduce coupling between modules, thereby ensuring the scalability of the 3D visualization system. This architecture is based on event triggering, subscription, publishing, and response mechanisms, enabling different modules to register and respond to events as needed. With the event-driven mechanism, the 3D visualization system can obtain various data sources in real time. The event-driven architecture for tea production lines incorporates modern communication and data transmission technologies, including OPC UA and Rabbit Message Queue (RabbitMQ), to achieve efficient data management and processing. When specific events or data updates occur on the production line, the OPC UA server publishes relevant information to the RabbitMQ message queue. Subsequently, handlers subscribed to these messages can immediately retrieve the information and respond accordingly. Most importantly, the model within the event-driven system synchronizes with the physical system. When model updates are triggered, the system reflects changes in the physical system, ensuring the model’s accuracy.

2.2.2. Scene Rendering

To enhance the visual realism of the tea processing production line scene, Unity 3D 2020 software was utilized for equipment model texturing, UI design, and lighting implementation. The entire scene underwent lighting baking to further improve the consistency between the virtual production line and the actual production line.

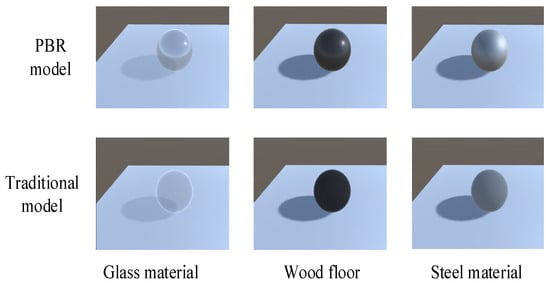

In traditional 3D scene rendering models, material and light source parameters must be continuously adjusted based on empirical models to achieve rendering results that more closely match real-world visual effects. However, these parameters are scattered across various components of the rendering engine, making the adjustment process quite time-consuming. Additionally, the universality of rendering parameters across different lighting scenarios must be considered. To avoid these issues, the system employs a physically based rendering (PBR) model.

Comparing physically based rendering models with traditional models reveals that PBR model surfaces exhibit not only specular reflections but also finer surface roughness, accurately reflecting the distribution of reflections on real-world object surfaces, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Comparison of different material rendering effects.

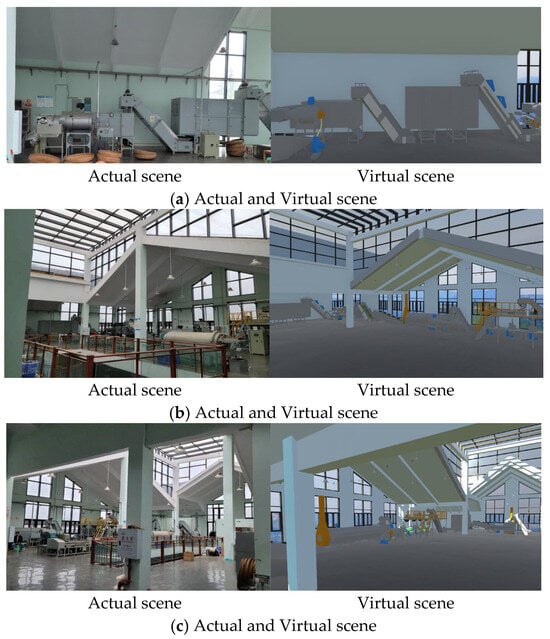

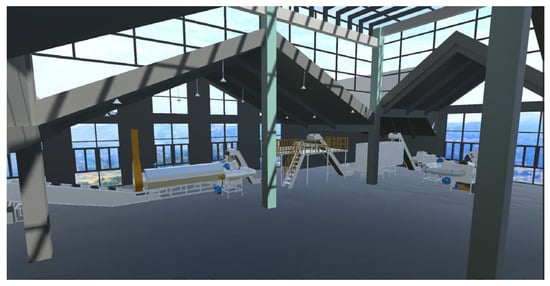

Using 3D 2020 modeling software, we created three-dimensional models of various processing equipment on the tea production line, including killers, rollers, and drying equipment. These 3D models of tea processing equipment were imported into Unity 3D 2020 software. The actual production line scene and the virtual scene are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Comparison effect between physical and virtual scenes.

2.2.3. Scene Lighting Rendering

In the green tea processing production line scene, light propagation directly influences object brightness, shadows, and reflections. Light information within the scene is computed and stored in textures to enhance virtualization efficiency. The entire green tea processing production line scene underwent light baking, with the results shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

System lightmap baking results.

Since both direct and indirect lighting from the main light source have been pre-baked into the light map, the scene lacks real-time lighting. Lighting adjustments are performed during post-processing to enhance the lighting rendering quality of the tea production line.

2.3. Dynamic Simulation of Tea Processing Production Line

2.3.1. Virtual Scene Monitoring

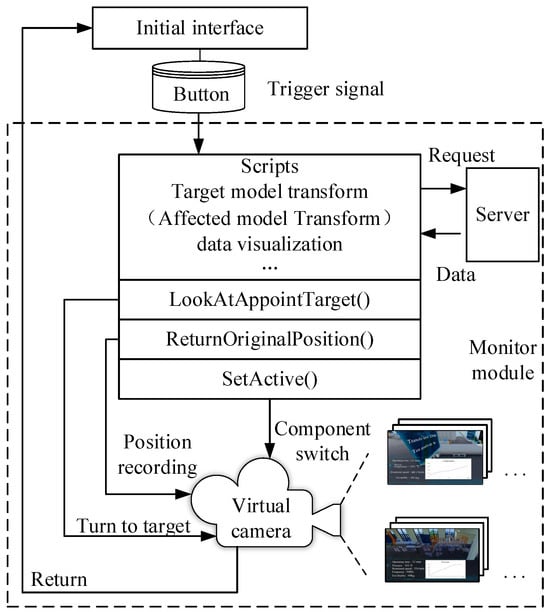

To comprehensively monitor the operational status of the tea production line, the visual monitoring system module provides functionality to switch between different monitoring perspectives. By controlling the smooth movement and positioning of virtual cameras, different processing equipment along the production line can be observed, thereby enabling monitoring of the production line’s operational status. The production line monitoring logic diagram is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Production line monitoring logic diagram.

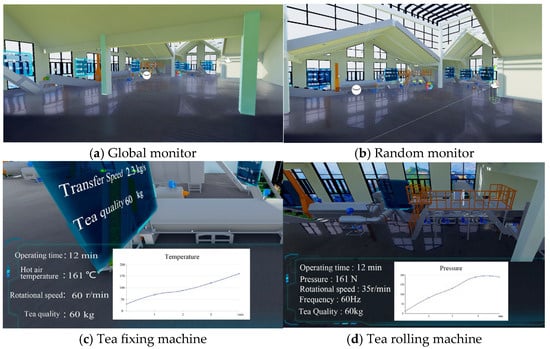

Monitoring perspectives for the processing production line include global view, equipment object view, and free view. The global view obtains operational parameters of each processing device by controlling the rotation of a virtual camera. Equipment monitoring views are accessed by moving the virtual camera. Monitoring displays are presented in chart formats. Random monitoring switches the primary virtual camera to a random virtual camera and incorporates object mesh collision detection. This ultimately enables users to freely navigate within the virtual tea processing production line. The multi-perspective monitoring of the tea processing production line is illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Multi perspective monitoring of production lines.

2.3.2. Virtual Machining Equipment Driver

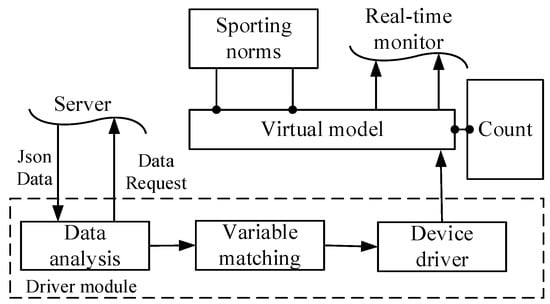

The drive module controls the motion of virtual equipment on the production line, including component position changes, rotation, and displacement. The drive process for the tea production line is shown in Figure 8. The drive module obtains real-time production line data through the data response interface. This data updates the digital twin model, ensuring it remains consistent with the actual production line.

Figure 8.

Driving process of tea production equipment.

Data parsing scripts are used to extract and parse JSON-formatted data retrieved from servers. Variable mapping scripts then match the parsed data to corresponding interfaces within the production line. Finally, through the integration of device drivers and motion specification scripts, the matching and driving functions for each model component within the production line are completed.

2.3.3. Simulation of Virtual Manufacturing Line Operation

Certain attribute parameters within the visual virtual space require acquisition through numerical simulation. The tea state simulation function drives tea-related data on the production line, such as mass, processed color, and transport velocity. Within the tea processing production line, distinct equipment types have corresponding script definitions for operational simulation. Multi-mechanical structure equipment simulation is achieved by establishing parent-child relationships.

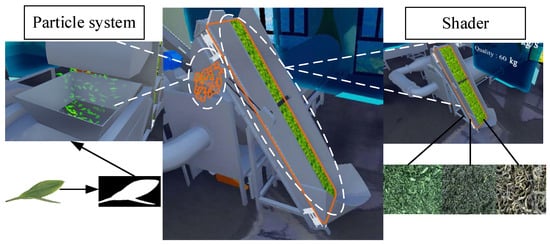

Tea leaf state simulation involves parameter parsing via data analysis scripts alongside concurrent data processing. A particle system is established to simulate the falling motion of tea leaves. By configuring particle parameters such as shape, material properties, quantity, and lifespan, the simulation reproduces the falling states of tea leaves following various processing stages.

Taking the initial conveyor belt as an example, Figure 9 shows the simulated state of tea leaves on the belt. By analyzing the weight of the tea leaves and the conveyor belt’s transmission speed, and using script code to control the particle system’s activation and playback speed, the simulation of tea leaf quantity is achieved. Shaders control the appearance and behavior of the tea leaves material on the conveyor belt, such as texture, color, and motion.

Figure 9.

Virtual tea simulation.

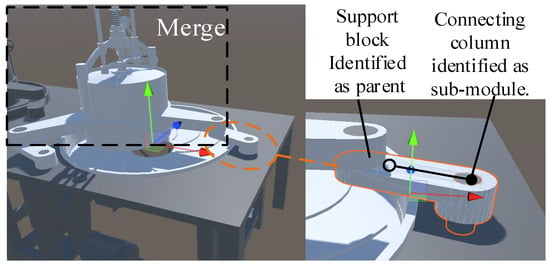

The processing of green tea primarily consists of three stages: fixation, rolling, and drying. Rolling occurs after fixation, where tea leaves undergo compression and friction against the circular discs at the bottom of the rolling machine. Through squeezing, kneading, and tumbling, the cellular structure of the leaves is disrupted. Tea juices are released, causing the leaves to curl or form into balls [23].

In the 3D visualization system, the kneader operates by rotating around a central disk via three support blocks at its base, while the support blocks themselves rotate around the right-end connecting column. To ensure the virtual kneader’s processing actions match those of the real kneader, all components above the support blocks are merged into a single entity with parent-child relationship attributes applied. The simulation of the virtual kneader’s operation is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Simulation of virtual rolling machine operation.

3. Results

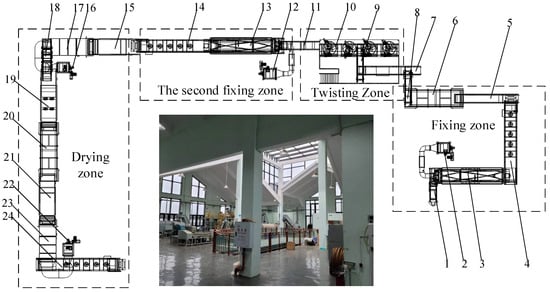

According to the actual tea processing production line in the factory, the overall layout of the green tea processing production line is designed, as shown in Figure 11. The whole production line consists of two fixing machines, three cooling conveyors, four rolling machines, two moisture regainers, two dryers and several conveyor belts.

Figure 11.

Overall layout of the production line. (1. Feed conveyor belt. 2. De-enzyming hot stove. 3. Hot air fixing machine. 4. Cooling oblique conveyor. 5. Returning feed conveyor belt. 6. Return machine. 7–9. Twisting feed conveyor belt. 10. Twisting unit. 11. Erqing feed conveyor belt. 12. Two green hot blast stove. 13. Hot air fixing machine. 14. Cooling oblique conveyors. 15. First drying feed conveyor belt. 16. Initially baked hot stove. 17. Dryer. 18. Vibration trough. 19. Rehydration feed conveyor belt. 20. Return machine. 21. Two baking feeding conveyor belt. 22. Two-burner hot stove. 23. Dryers. 24. Cooling inclined conveyor).

3.1. Operation Test Analysis

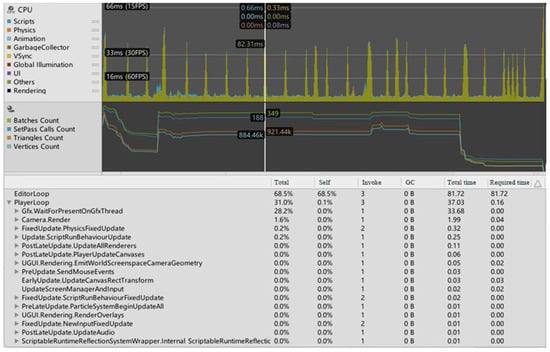

The overall system performance was tested using the Unity Profiler. During system testing, the Statistics window was employed alongside three monitoring tools—CPU, Render, and RAM memory—to better evaluate the operational status of each frame. After running the Unity Profiler, it was observed that CPU resources were primarily consumed by EditorLoop and PlayerLoop, as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

System performance indicators.

Within PlayerLoop, due to the scene characteristics and the machining equipment objects, the rendering workload for Camera Render operations increased, consequently driving up the demand for camera batch rendering. Additionally, Gfx.WaitForPresent indicates that the CPU main thread is waiting for GPU rendering. Profiler warnings indicate excessive time consumption. GPU rendering is overburdened.

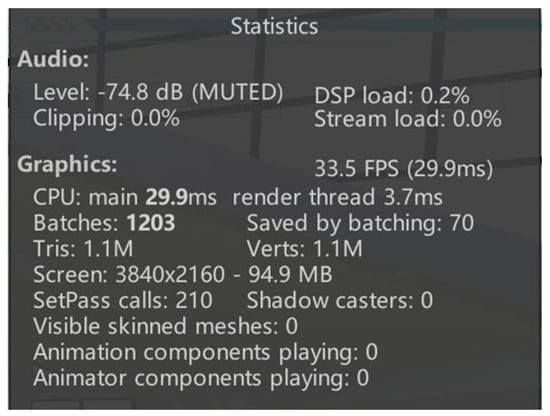

Figure 13 displays the image rendering window. Post-rendering statistics confirm that the rendering thread took a relatively long time, reaching 29.9 ms. The Saved by batching value of 70 indicates that only a small number of objects in the scene were rendered using batching. Additionally, the number of faces and vertices rendered is significantly high. The Shadow caster metric shows that no objects in the scene are capable of casting shadows, indicating a need for further shadow projection implementation. The CPU frequently passes rendering instructions to the GPU, resulting in excessive workload for both the CPU and GPU.

Figure 13.

System rendering data.

To enhance system operational efficiency, performance improvements were achieved through methods such as DrawCall optimization and Shader optimization. Given the presence of multiple device models within this system, both static batching and merged batching techniques were employed to optimize DrawCalls. During a static batching process, multiple static or nearly unchanging objects are consolidated into a single entity. Additionally, for mesh-based device models sharing identical materials, GPU instantiation enables the completion of multi-batch mesh rendering.

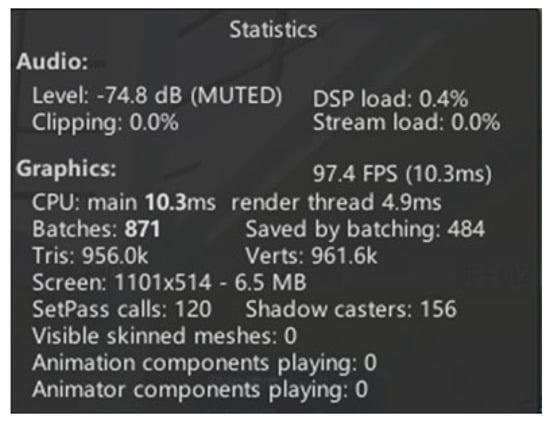

The primary task of the system shader tool is to simulate the state of tea leaves under different processing stages and the materials of processing equipment. Based on this, the use of keywords such as shader_feature and pragma multi-compile has been reduced, thereby decreasing parsing time. The number of shader variants has been minimized, resulting in reduced memory consumption. The optimized system’s performance metrics are shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Optimized system rendering data.

Compared with the rendering data before optimization in Figure 13, Figure 14 proves that the FPS value is increased by 2.91 times, the number of Batches batch processing is reduced by 27.6%, and the SetPass calls is reduced by 42.8%. In addition, the shadow of the key components of the equipment is set to be acceptable, the shadow rendering value is set to 156, and the scene authenticity of the green tea processing system is fully guaranteed

3.2. Client Performance Test

The CPU utilization, memory occupancy and GPU utilization of the client are used as indicators to test the effect of the system client during operation. The client computer is configured as follows: The operating system is Microsoft Windows 10 Professional, CPU is Intel Core i5-11300H 3.1 GHz, RAM memory is 16 GB 3200 MHz, graphics card is MX450. The visualization system of green tea production line was tested for 1 h. The test results show that the CPU utilization of the system is about 22%, the memory usage is 1297 MB, and the GPU usage is about 65%. The design of three-dimensional visualization system is more complex. GPU instantiation is used in the visualization system, which involves a large number of two-dimensional and three-dimensional graphics rendering. Therefore, the GPU occupancy rate is high, but it still meets the requirements of CPU and memory occupancy rate. In summary, under the conventional computer configuration, the digital twin system of green tea production line can run smoothly and meet the needs of the system client.

3.3. Comparative Test of Tea Production Line

The fresh tea leaves of the same batch in the factory were obtained as experimental materials, and the control group and the experimental group were set up. Three tea leaves with the same weight were obtained, one of which was used as a comparison material for microwave locking. Another group of fresh tea leaves was actually processed in the factory. After obtaining the third set of tea related parameters, the three-dimensional visualization system simulation experiment of green tea production line was carried out. The tea simulation experiment data and the actual factory processing data were compared and analyzed.

The test results are shown in Table 1. The data obtained by the three-dimensional visualization virtual production line are basically consistent with the actual factory processing data. The three-dimensional visualization system of tea production based on digital twin can effectively simulate the tea processing technology.

Table 1.

Comparison test of tea processing actual production line and virtual simulation system.

4. Conclusions

This paper successfully developed a three-dimensional visualization system for tea production lines based on digital twin technology, achieving real-time mirroring of actual tea processing equipment. The designed digital twin simulation system for tea processing represents a successful application of visualization technology in agricultural production. The simulation system provides multi-source data for displaying, analyzing, and managing tea processing workflows, thereby reducing equipment debugging time and trial-and-error costs while enhancing overall tea processing efficiency.

(1) According to the overall structure of green tea processing technology, the digital twin model of green tea processing production line was constructed. Through the combination of hierarchical design, particle system and data, the simulation of production line processing equipment and processing process is completed, and the combination of two-dimensional and three-dimensional data is realized.

(2) Based on the real scene of green tea processing production line, the equipment material of virtual production line is optimized. Through the lighting baking and rendering processing technology, the fidelity of the system scene is enhanced, and the virtual scene optimization of the green tea processing production line is finally realized.

(3) The client test of digital twin system of green tea processing production line and the comparative test of green tea processing were carried out. The results indicate that the data obtained from the 3D visualization virtual production line aligns closely with actual factory processing data, and the client application performs effectively.

This paper utilizes digital twin technology to achieve visualization of the tea processing workflow in the agricultural sector. The research also has certain limitations. The ultimate goal of the digital twin system for tea production lines is to achieve bidirectional mapping and real-time interaction between physical processing lines and virtual models. This paper only implements unidirectional mapping from physical production equipment to virtual models. A higher-level digital twin system is anticipated to be realized soon, thereby establishing true closed-loop control for tea production lines. The realism of images in this system can still be enhanced by optimizing scene rendering methods. For instance, the parameter models within the BRDF can be further refined, and the actual material parameters of tea processing equipment can be measured. After completing development, this system has been tested exclusively on the Windows platform. Future applications are anticipated for platforms such as WebGL and Android. Through multi-platform testing and optimization, a multi-platform, lightweight, adaptive digital twin system for tea processing is urgently expected.

Author Contributions

H.L., methodology, validation; G.M., original draft preparation, software; K.Z., resources, visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Shandong Provincial Key Program Project (Shandong-Chongqing Science and Technology Collaboration) (2021LYXZ019).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

Thank all members of the 211 Laboratory at Shandong Agricultural University for their assistance with the experimental testing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, T.M.; Yang, T.T. Based on the analysis of the current situation of tea e-commerce market and the analysis of marketing mode. Fujian Tea 2023, 45, 32–34. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.; Yang, Y.; Hu, K.; Chen, J.; Djomo, S.N.; Yang, X.; Knudsen, M.T. Economic, environmental, and emergy analysis of China’s green tea production. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, K.L.; Liu, X.H.; Lei, R.Y. Development status of matcha industry in China. Packag. Food Mach. 2019, 37, 53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.X.; Sang, J.; Zhu, Y.F.; Zhang, Z.D.; He, L.F. Research and development of automatic equipment for shaping and printing of Houkui tea. Hubei Agric. Sci. 2018, 57, 115–119. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.W.; Guo, S.S.; Du, B.G.; Du, B.G.; Wang, L.; Guo, J.; Li, Y.B.; Yu, L. Research and practice on the construction method of digital twin model in water purification plant. Comput. Integr. Manuf. Syst. 2023, 29, 1867–1881. [Google Scholar]

- Ogunsakin, R.; Mehandjiev, N.; Marin, C.A. Towards adaptive digital twins architecture. Comput. Ind. 2023, 149, 103920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Z. From simple digital twin to complex digital twin Part I: A novel modeling method for multi-scale and multi-scenario digital twin. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2022, 53, 101706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parle, D.; Sharma, G.; Anand, N.; Padgaonkar, N.; Stoddart, D.; Malley, D.J. A comparative analysis for harnessing digital twin platforms for net-zero manufacturing. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 180175–180197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodyaho, A.; Delhibabu, R.; Ignatov, D.I.; Zhukova, N. Run time dynamic digital twins and dynamic digital twins networks. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2025, 172, 107823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Kapukotuwa, J.; Gouveia, E.L.S.; Fuenmayor, E.; Qiao, Y.; Murray, N.; Devine, D. Comparative Study of Digital Twin Developed in Unity and Gazebo. Electronics 2025, 14, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Sui, F.; Liu, A.; Qi, Q.; Zhang, M.; Song, B.; Guo, Z.; Lu, S.C.-Y.; Nee, A.Y.C. Digital twin-driven product design framework. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 3935–3953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhu, W.; Huang, J.; He, B. An intelligent monitoring system for robotic milling process based on transfer learning and digital twin. J. Manuf. Syst. 2025, 78, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Qi, Q.; Tao, F. A multi-scale modeling method for digital twin shop-floor. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 62, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Liu, G.; Liu, S.C. Research on simulation technology of digital twin and production line. J. Graph. 2021, 42, 349–358. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.X.; Guo, L.; Chen, L.X.; Zhang, H.Q.; Hu, X.T.; Zhou, H.Q.; Li, G. Research and implementation of digital twin workshop based on real-time data driven. Comput. Integr. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 27, 352–363. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J.H.; Ji, S.Y. Big data-driven workshop digital twin model construction method. J. Mech. Eng. 2023, 59, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Shi, T.; Huang, X.; Yu, T. A digital twin-driven in-process monitoring system for the ultrasonic vibration-assisted milling. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2026, 98, 103168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cunha, C.; Cardin, O.; Gallot, G.; Viaud, J. Designing the Digital Twins of Reconfigurable Manufacturing Systems: Application on a smart factory. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2021, 54, 874–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, Q.; Chen, X.; Zhang, D.; Leng, J. A Digital Twin-Based Approach for Designing and Multi-Objective Optimization of Hollow Glass Production Line. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 26901–26911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Y.; Pilati, F.; Faccio, M. Digital twin to improve the virtual-real integration of industrial IoT. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2021, 54, 158–162. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, F.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z.; Huang, Z.; Xue, R. Digital twin for smart manufacturing equipment: Modeling and applications. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 137, 4929–4946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, M.M.; Bajestani, M.S.; Noh, S.D.; Kim, D.B. Digital twin-based architecture for wire arc additive manufacturing using OPC UA. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2025, 94, 102944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.H.; Xu, L.; Chen, P.X.; Lin, H.H.; Su, M.J. Research progress on the processing technology of flowery green tea. Tea 2022, 48, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.