Extreme Strengthening of Nickel by Ultralow Additions of SiC Nanoparticles: Synergy of Microstructure Control and Interfacial Reactions During Spark Plasma Sintering

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Powder Preparation

2.2. Spark Plasma Sintering

2.3. Structural Analysis Methods

2.4. Mechanical Testing

2.5. Thermodynamic and Kinetic Modeling

3. Results

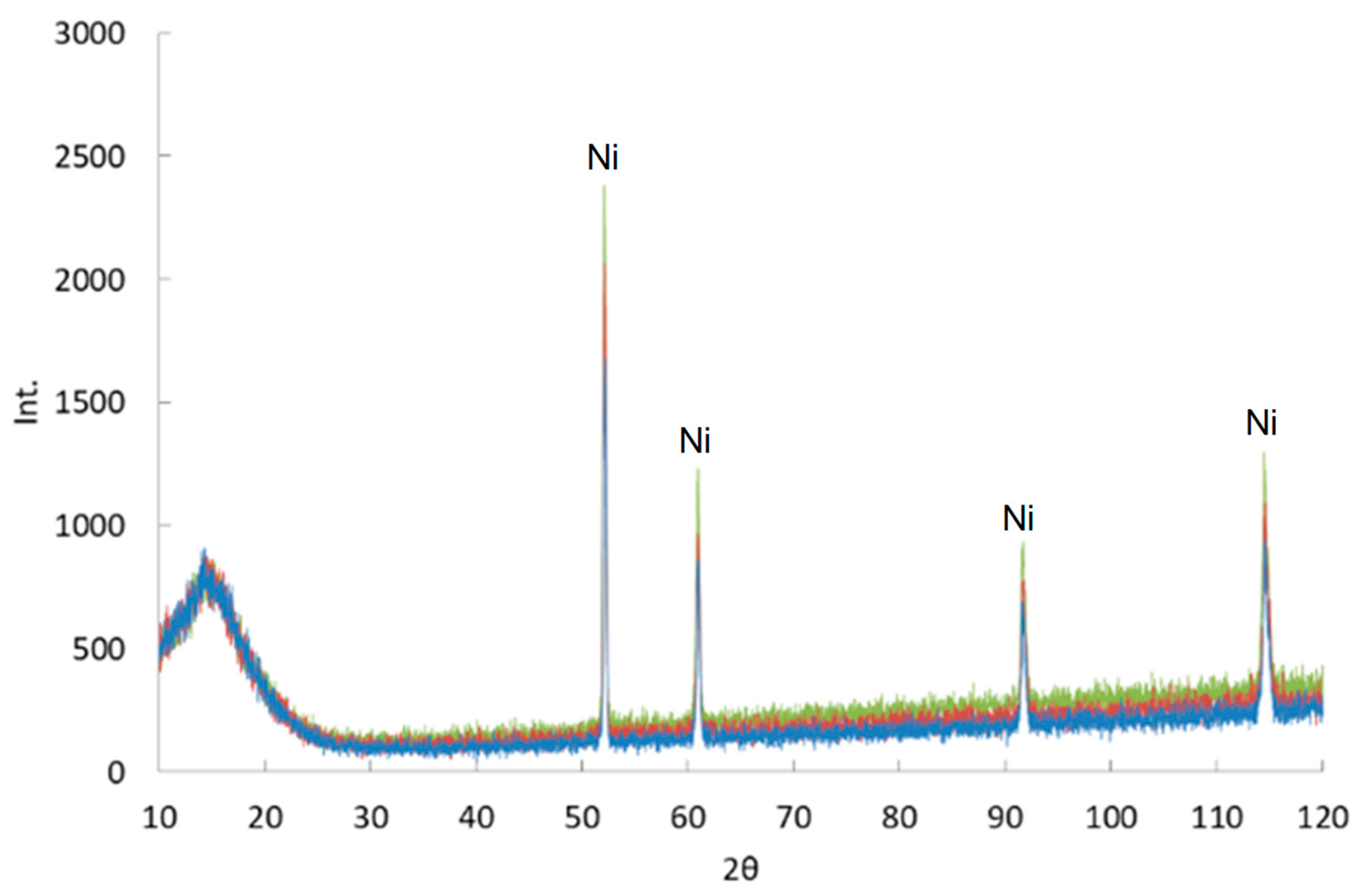

3.1. Structure and Phase Composition of Sintered Nickel

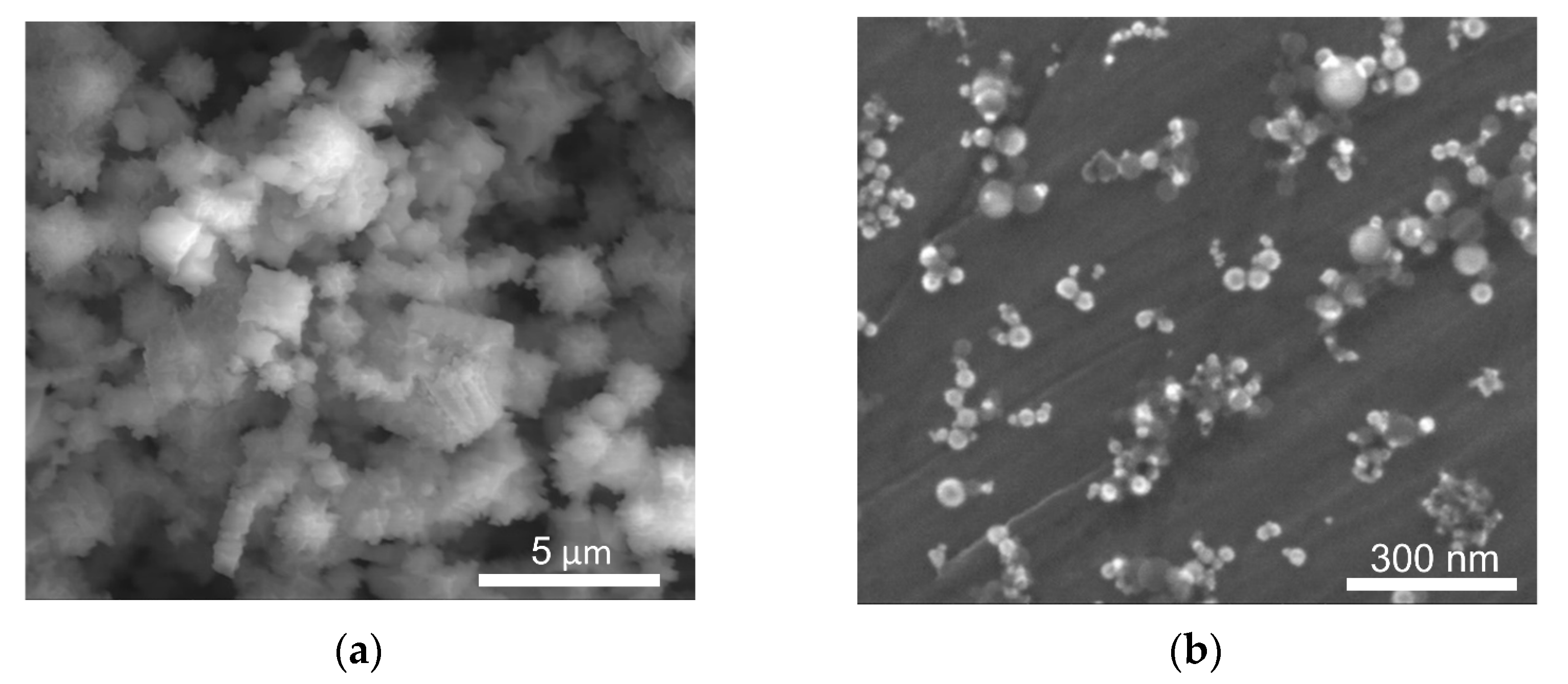

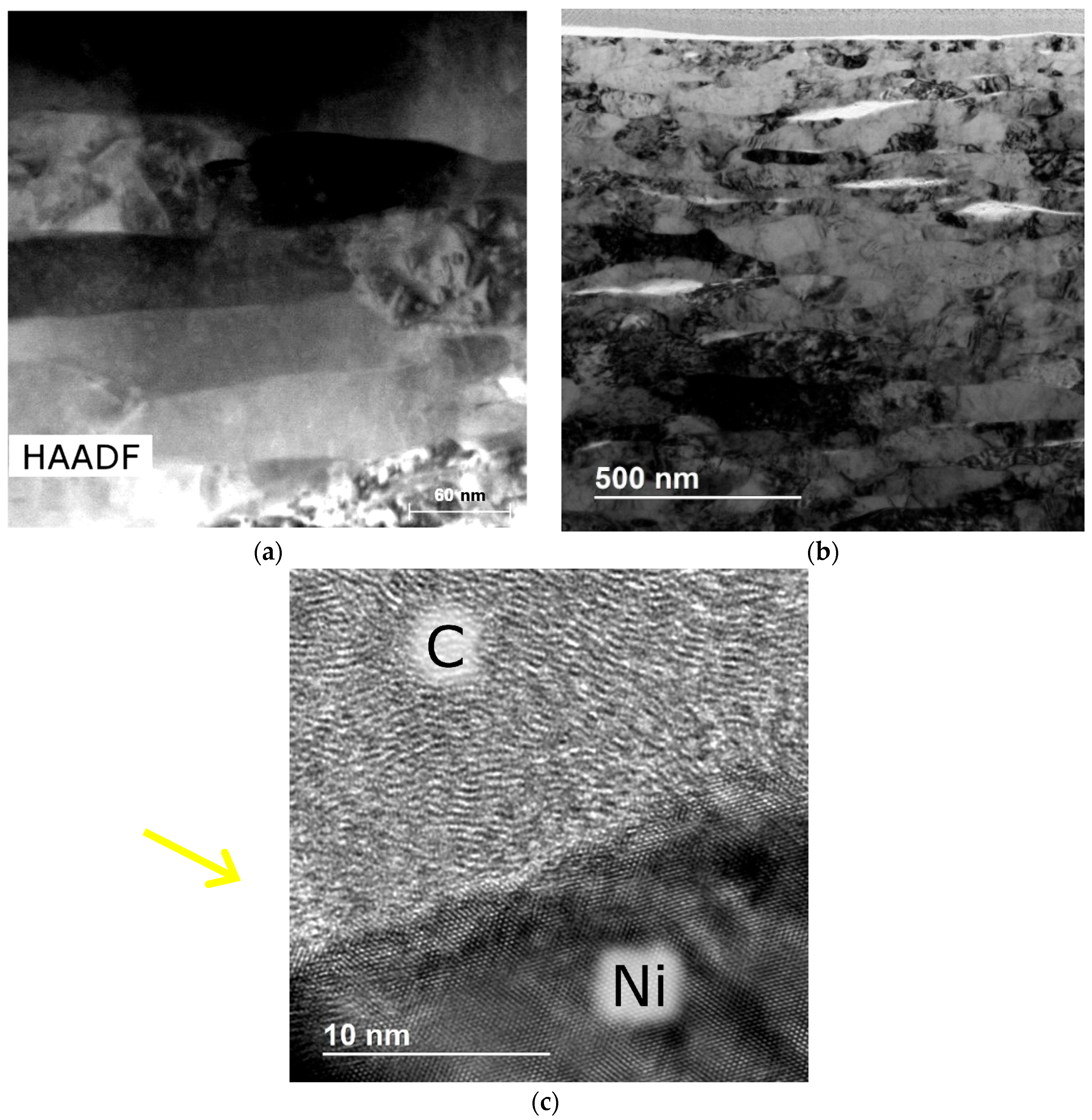

3.2. Structure of Ni–SiC Composites

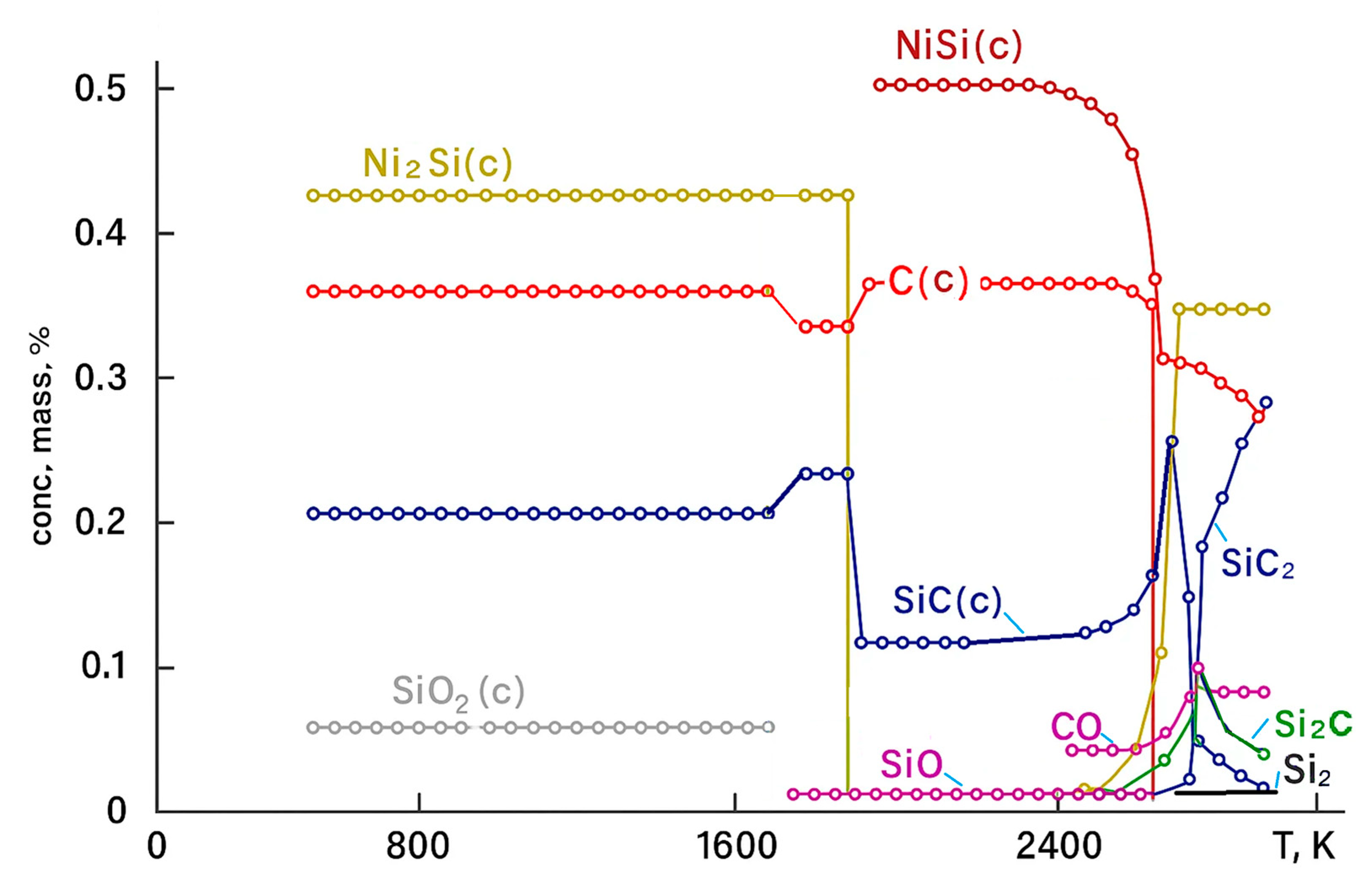

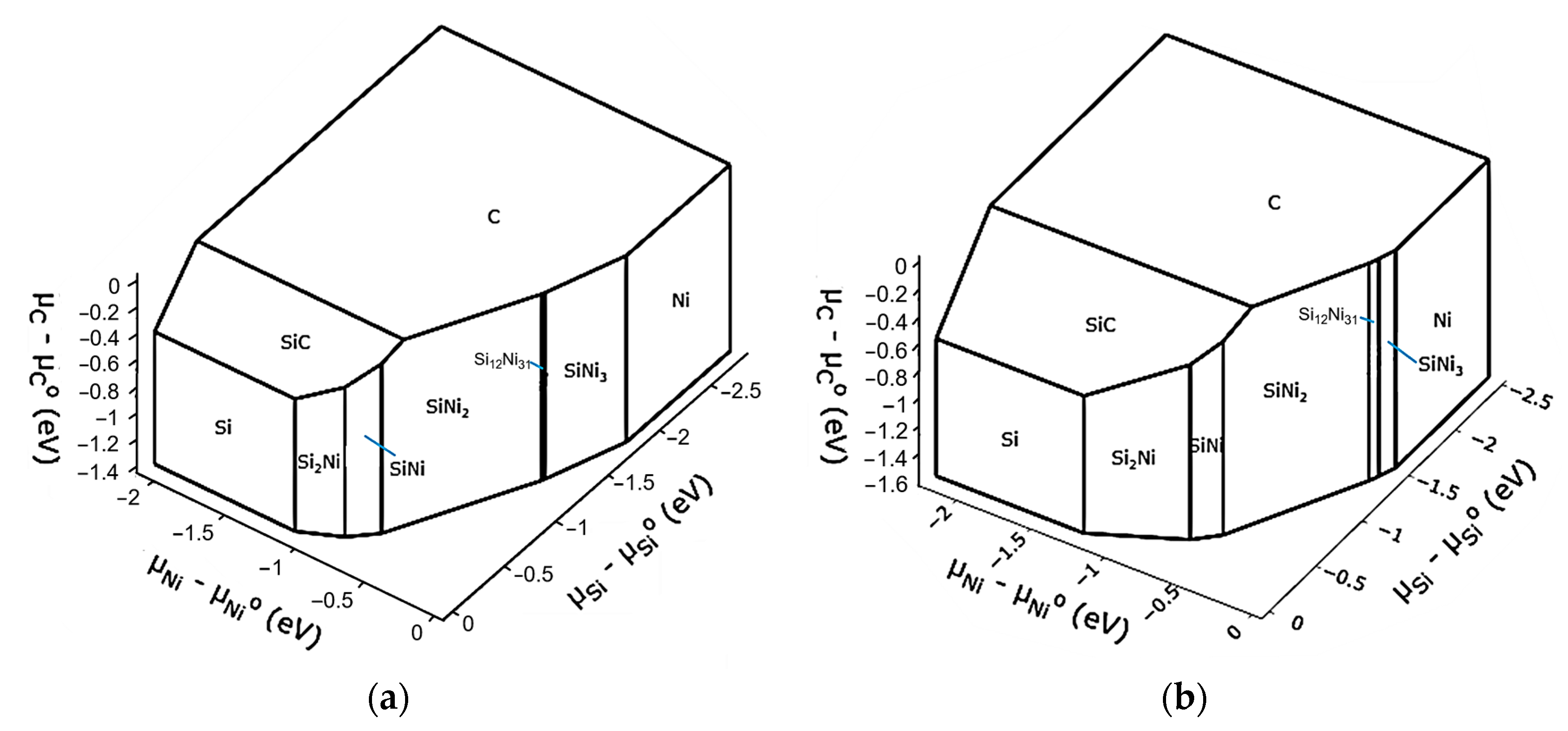

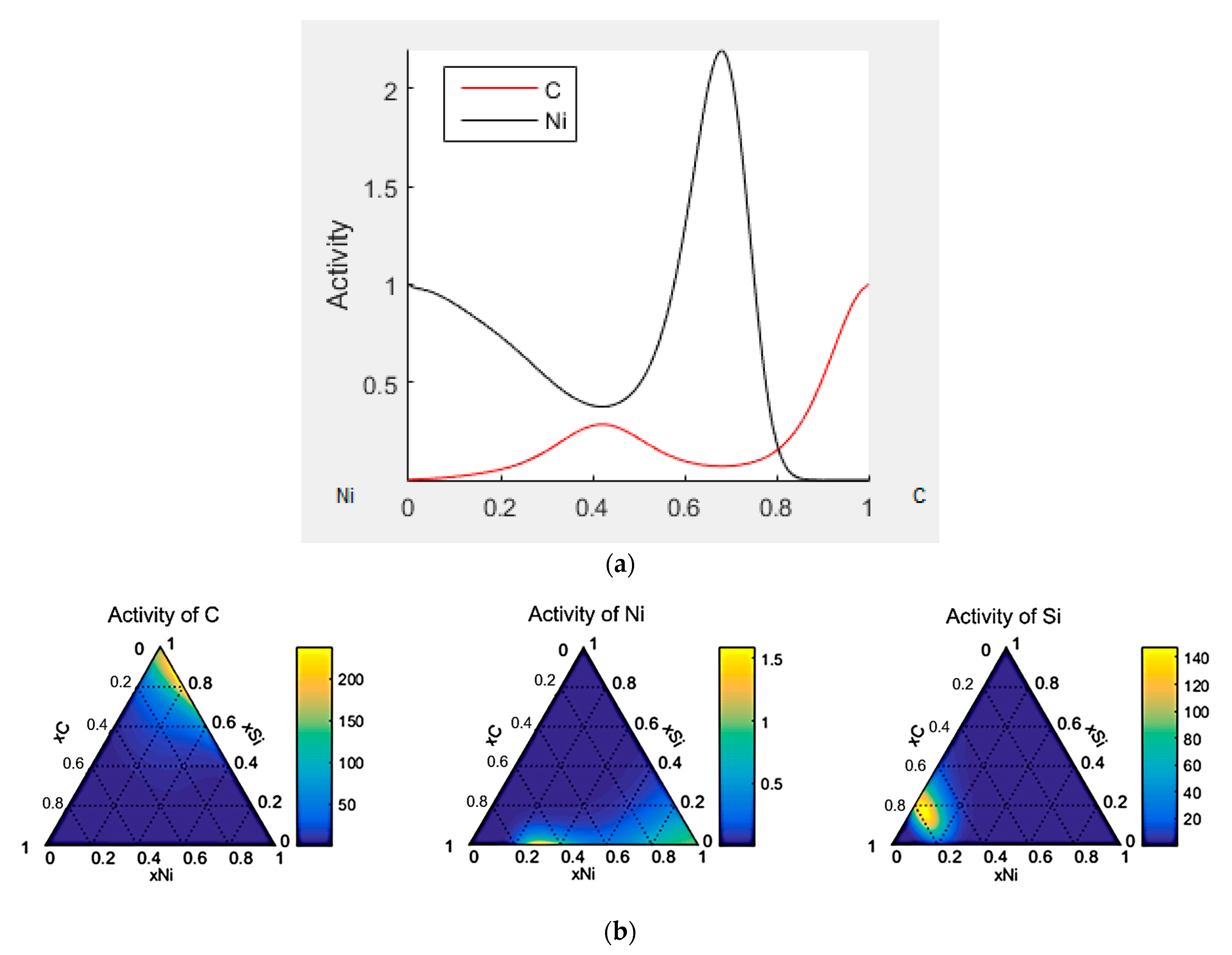

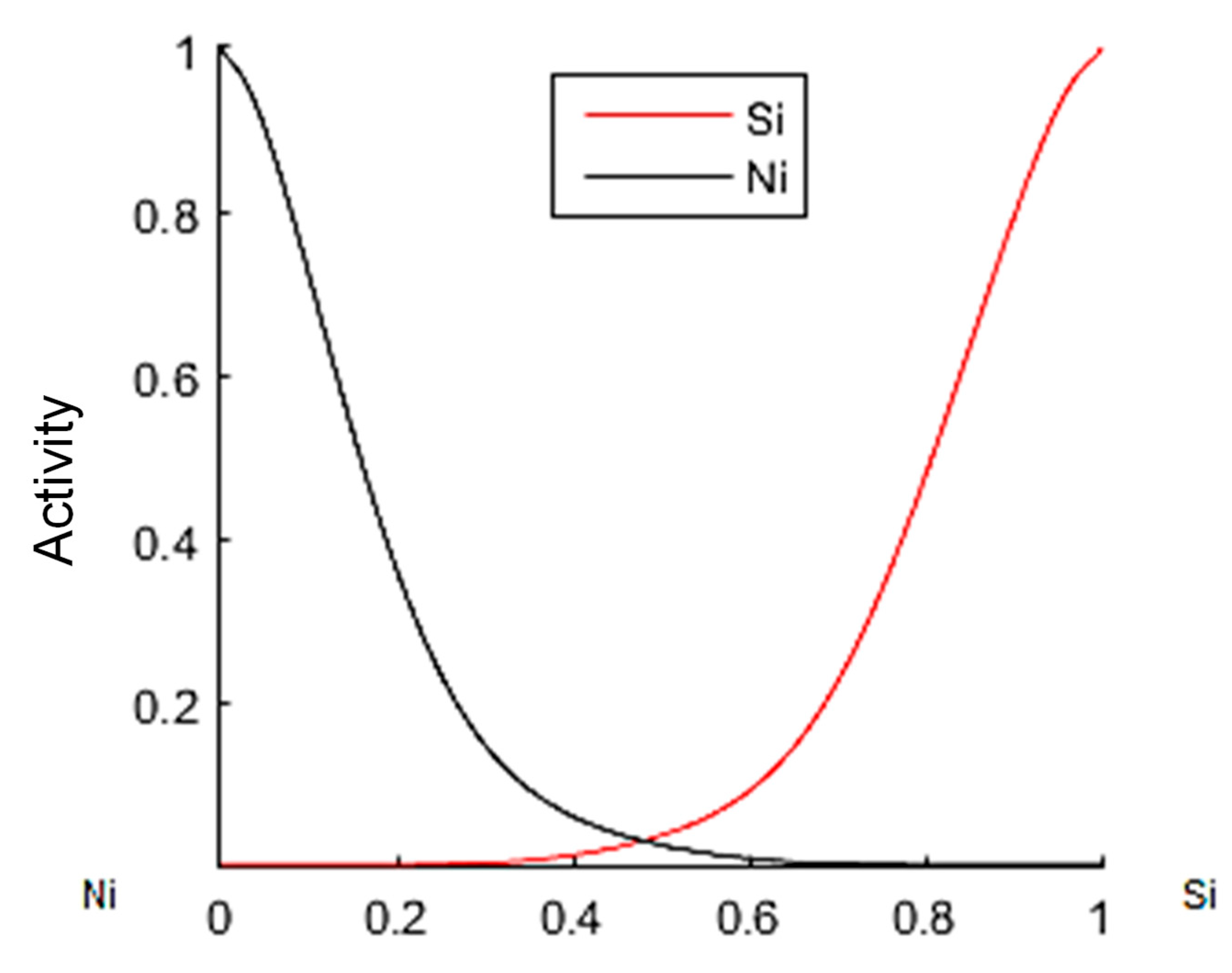

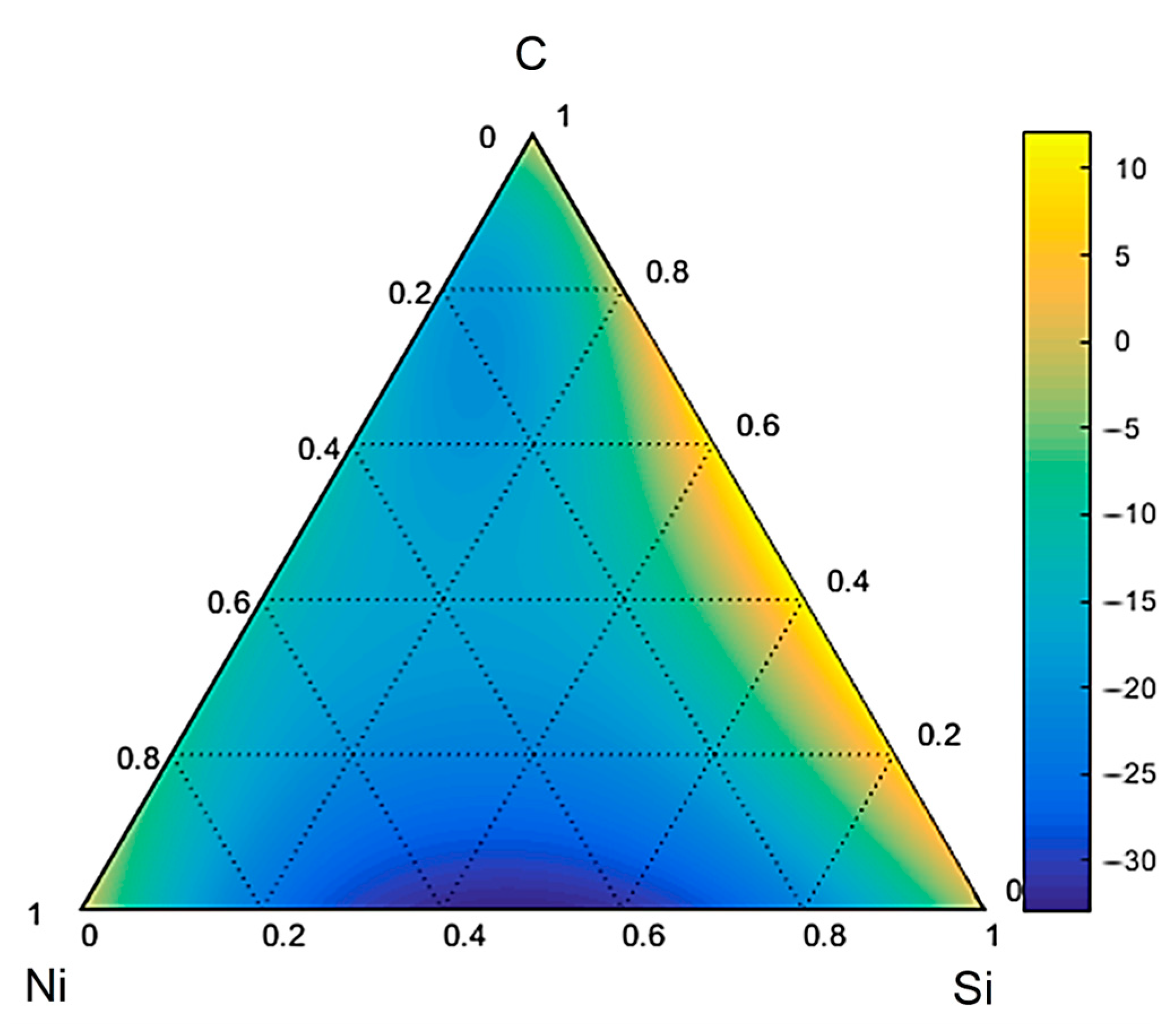

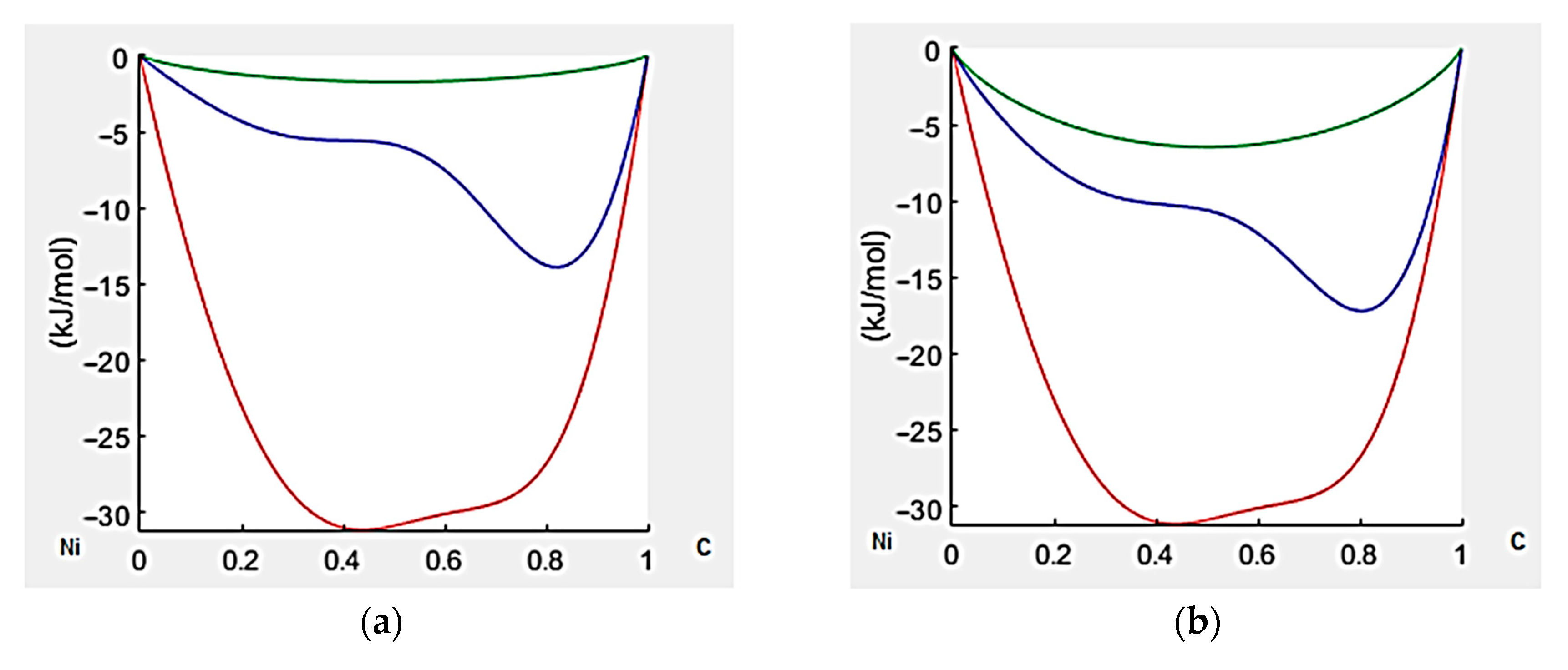

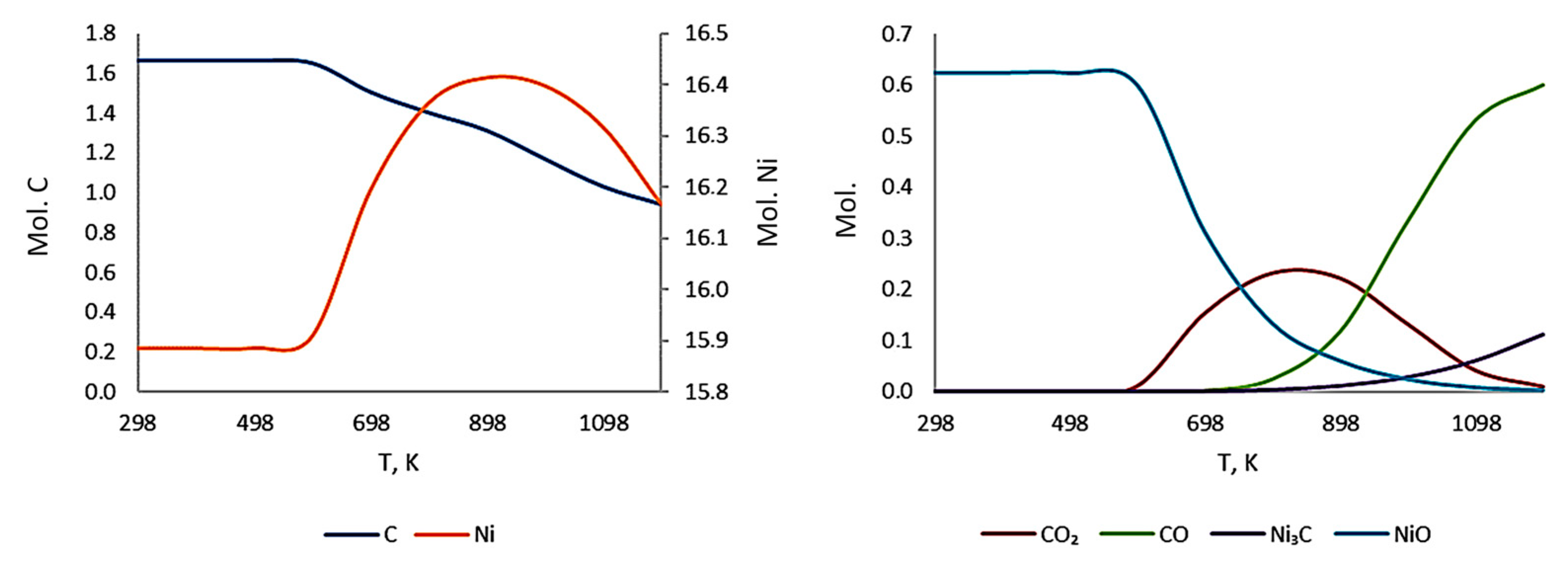

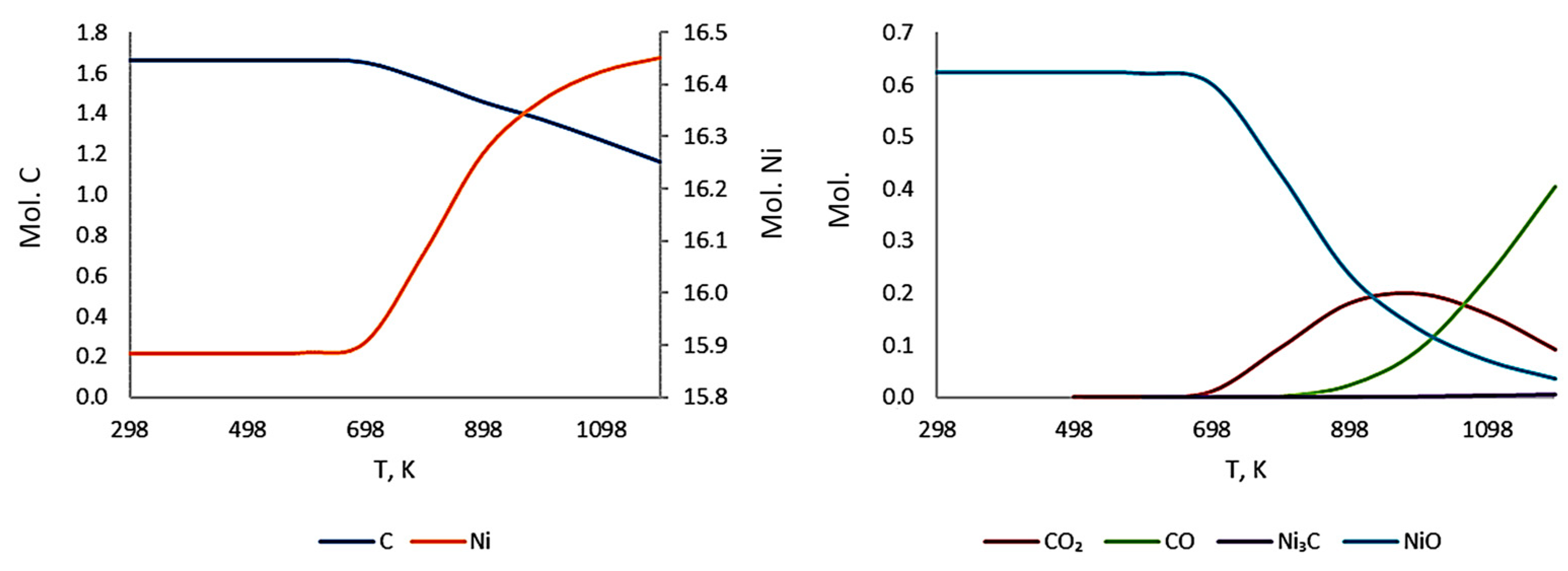

3.3. Thermodynamic Modeling and Analysis of Chemical Potentials

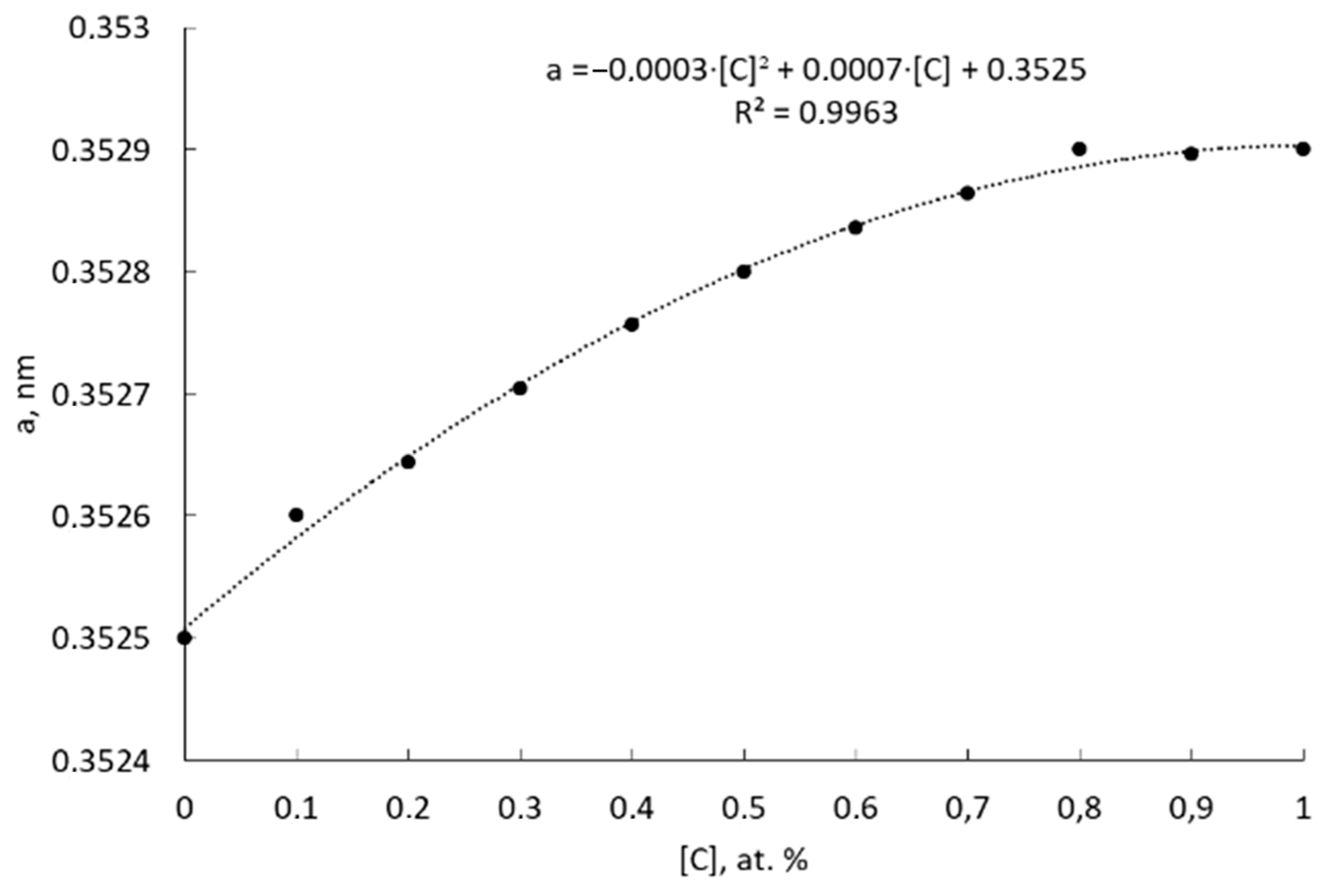

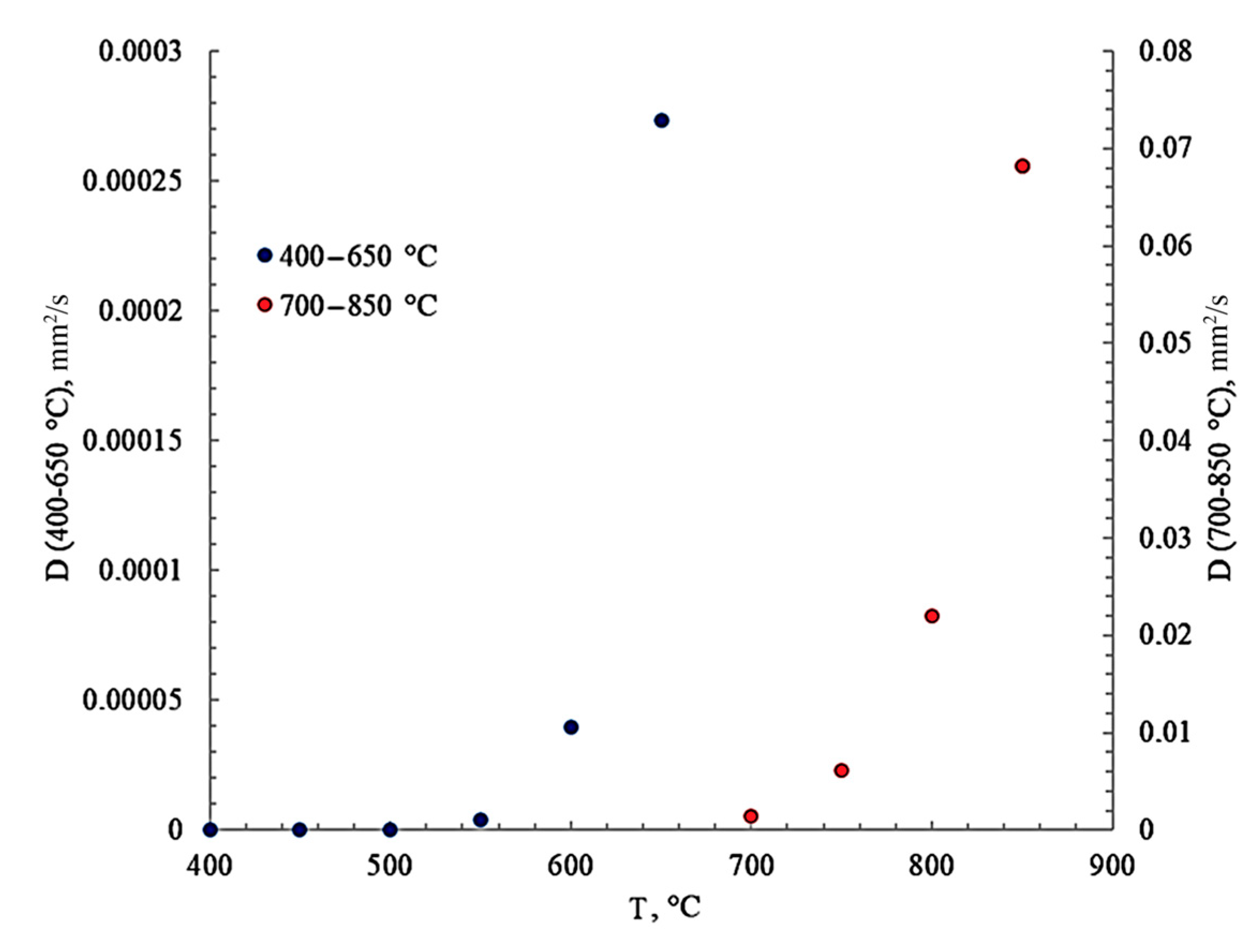

3.4. Kinetics of Carbon Diffusion in Nickel

3.5. Mechanical Properties

4. Discussion

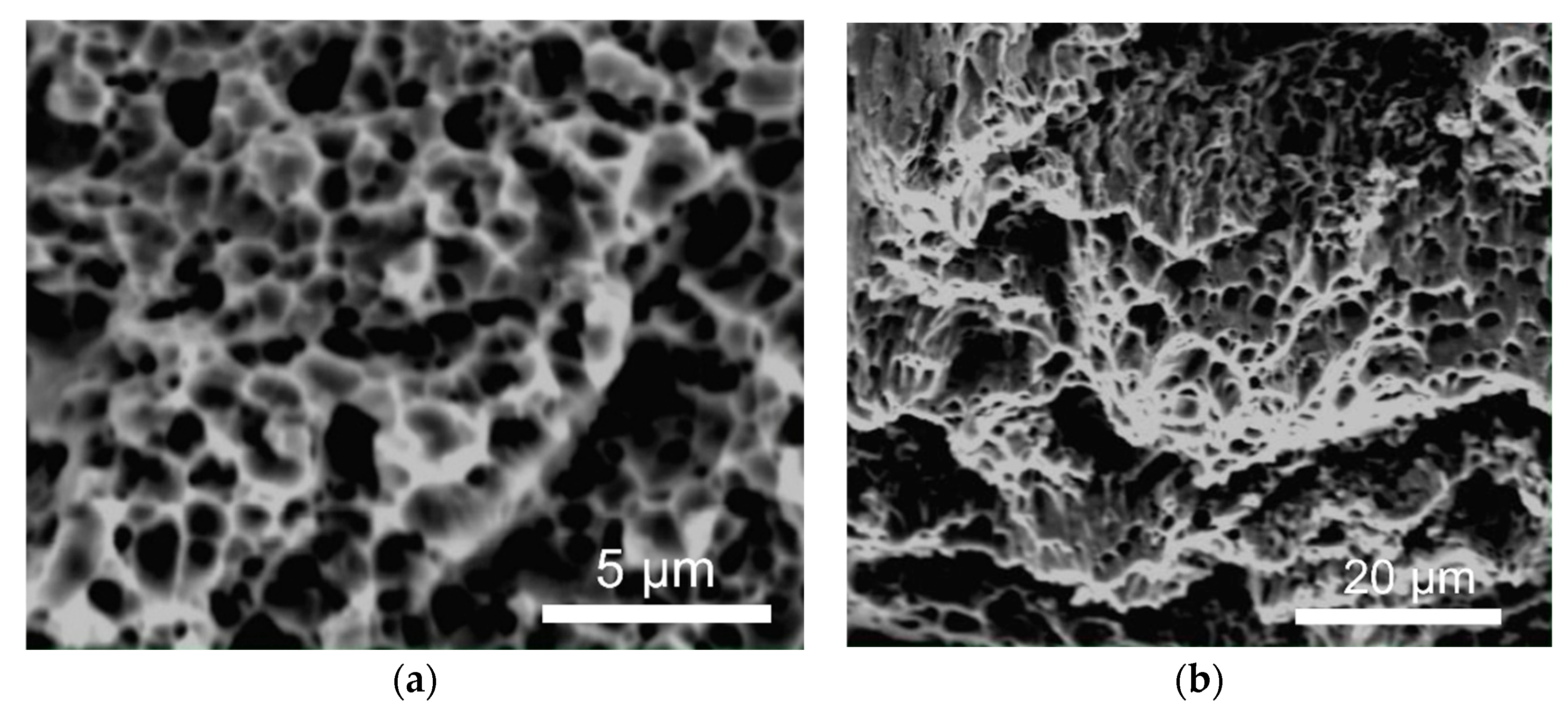

- This is Hall–Petch strengthening due to the ultrafine-grained substructure. For d ≈ 0.25 µm and kHP ≈ 0.1–0.2 MPa·m1/2 [46], we obtain ΔσHP ≈ 200–400 MPa. For regions with larger grains (d ~20 µm), the contribution drops to 20–40 MPa, reflecting the heterogeneity of the structure (0.15–0.4 µm by TEM), giving a contribution of ΔσHP ≈ 200–400 MPa.

- It is also solid solution strengthening by carbon (0.1–0.3 at.% in the Ni solid solution), giving a contribution of ΔσSS ≈ 45–135 MPa.

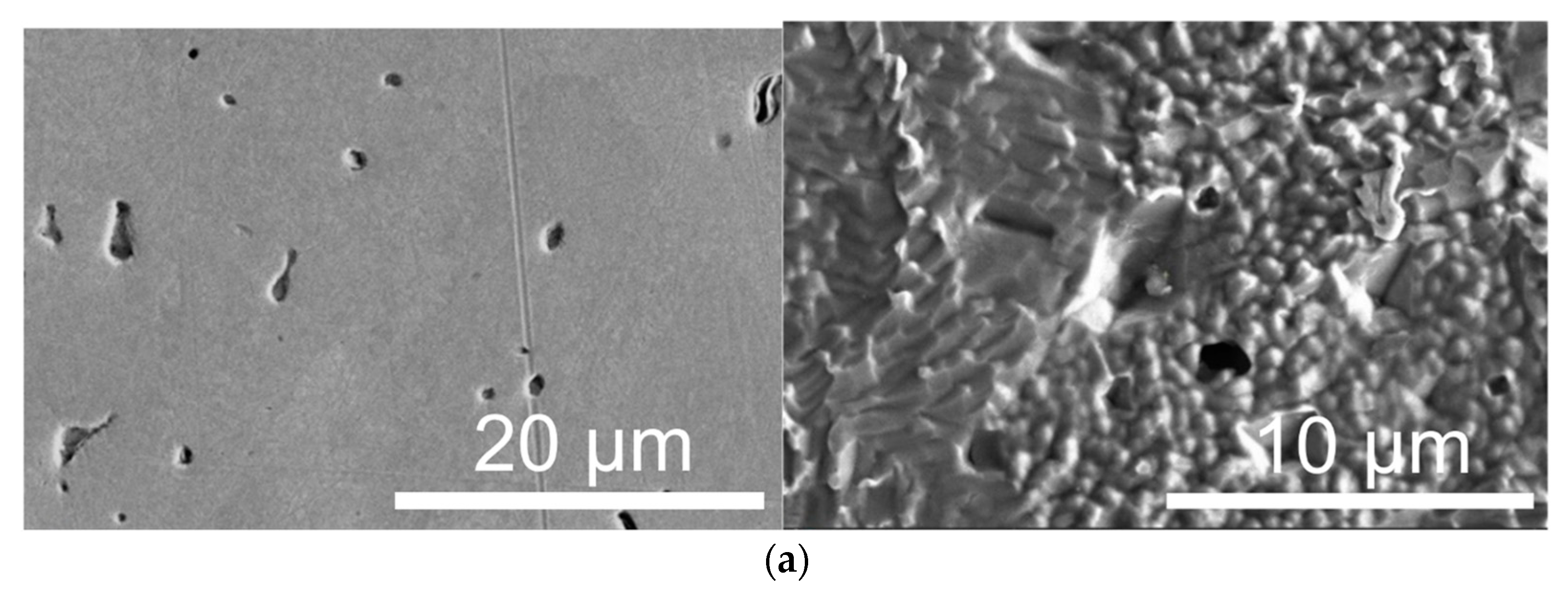

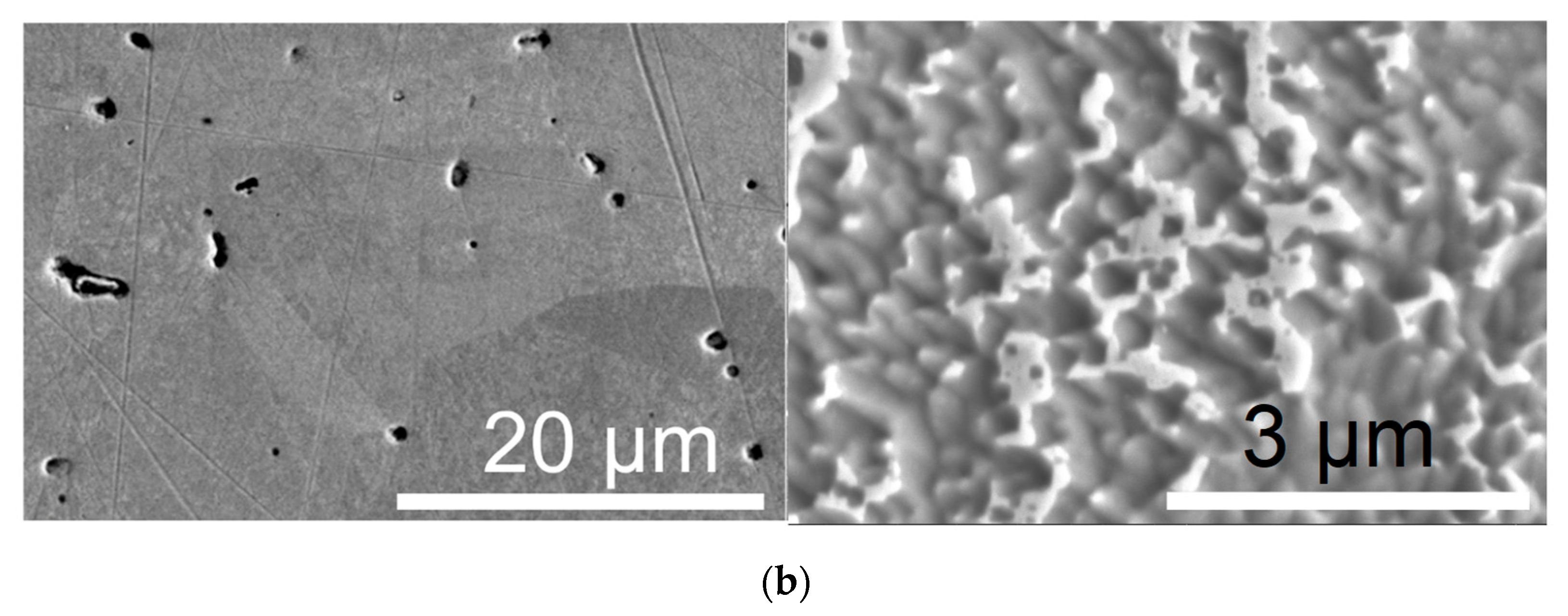

- Texture and elongated grain morphology formed during SPS under pressure create an additional contribution of Δσtexture ~50–150 MPa. TEM shows pronounced elongation of grains (Figure 1a,b), similar to structures after severe plastic deformation [47]. Models that take into account the shape factor predict an increase in yield strength of 10–30% compared to an isotropic fine-grained structure [48]. For σ ~525 MPa, this yields Δσtexture ~50–150 MPa.

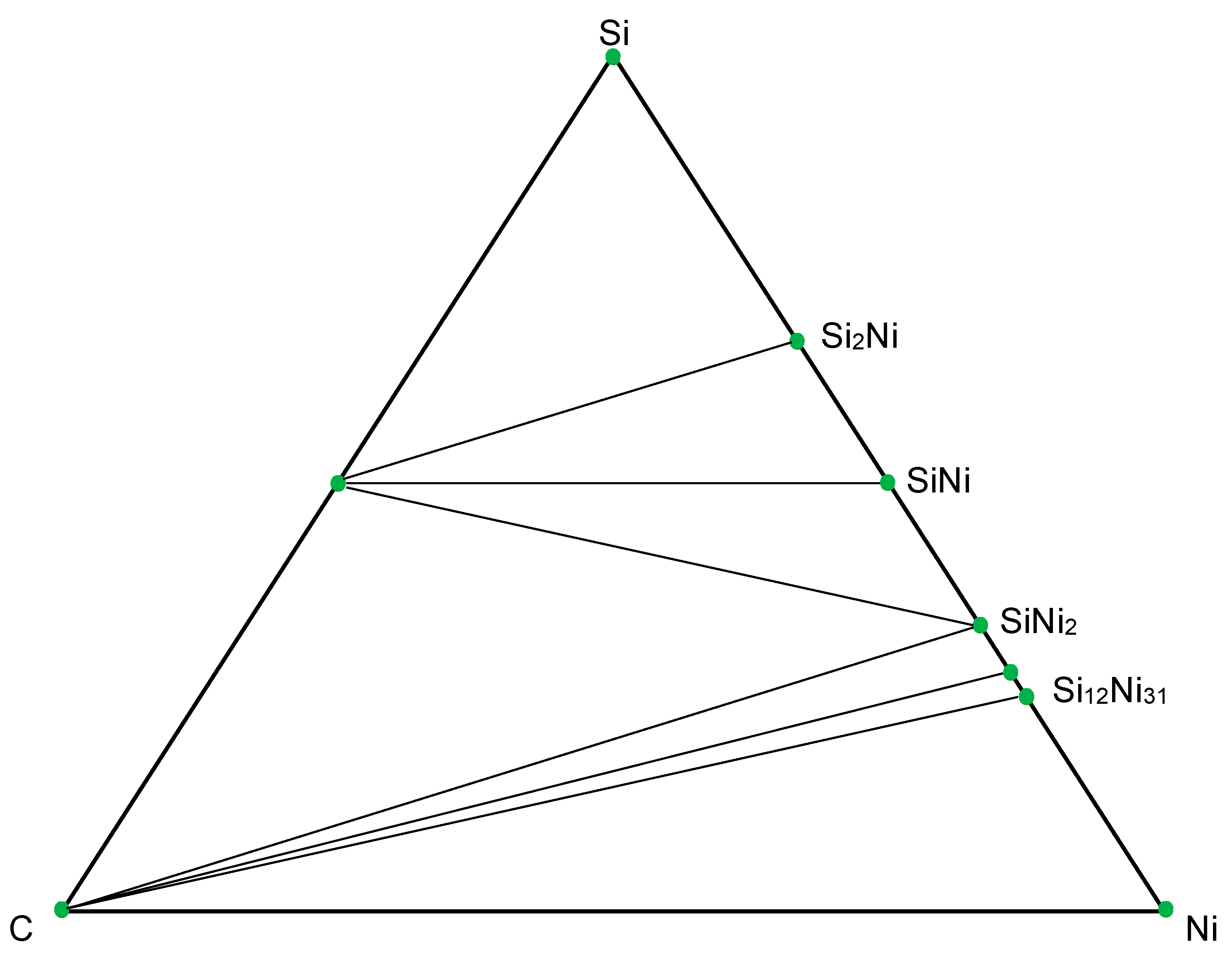

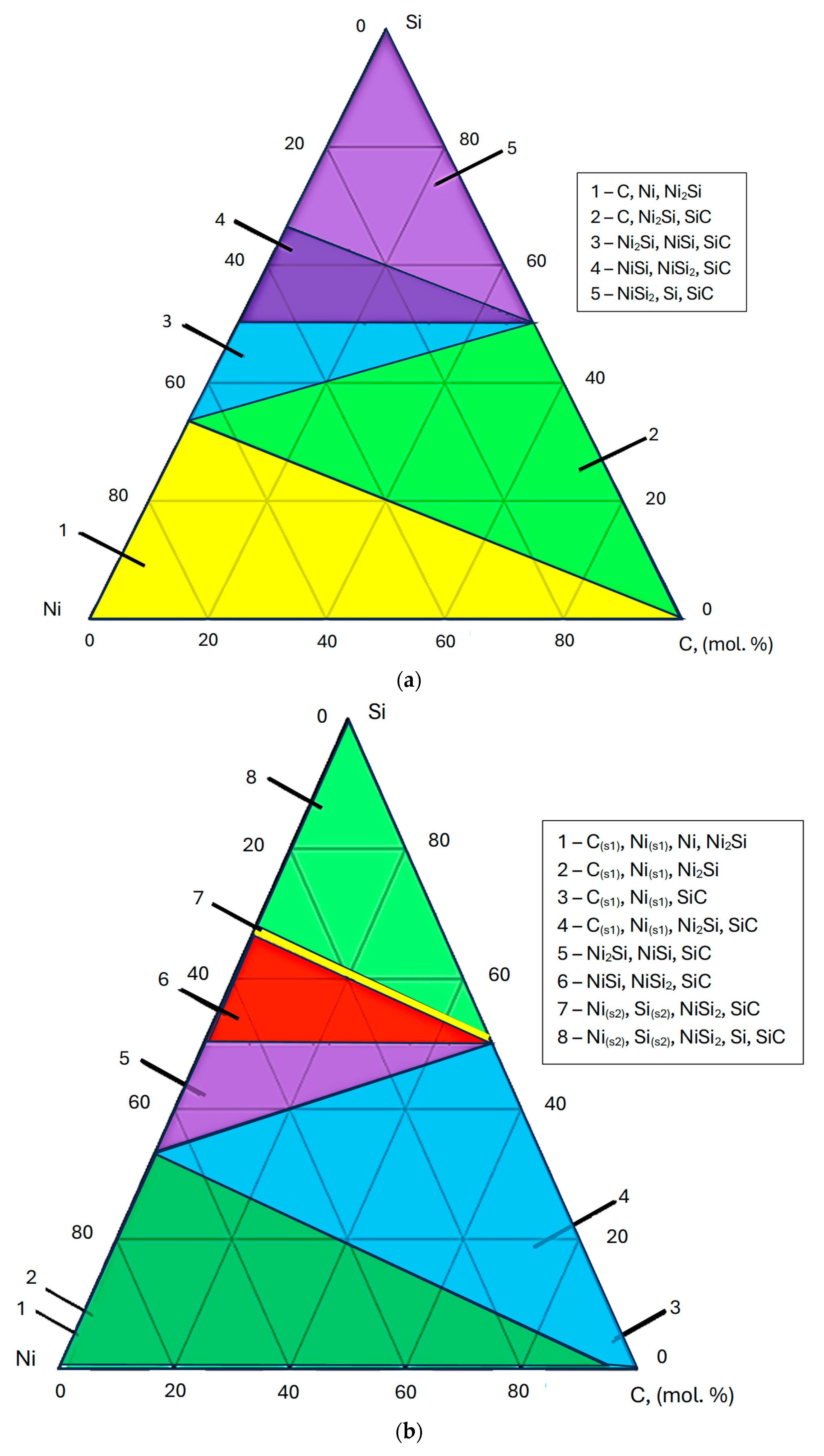

- It is also the result of the synergistic contribution of SiC decomposition products. Thermodynamic modeling and analysis of chemical potentials unequivocally demonstrated the thermodynamic instability of the Ni-SiC system at a sintering temperature of 850 °C. The decomposition of SiC nanoparticles results in the formation of free carbon (pyrolytic carbon at the boundaries) and, as hypothesis, nickel silicides (Ni2Si and NiSi). According to classical Zener theory, the efficiency of grain growth inhibition is determined by both the volume fraction and the particle size. The nanoscale silicide and pyrolytic carbon precipitates formed as a result of the controlled decomposition of SiC localize precisely at the grain boundaries. These nuclei are exceptionally effective for boundary pinning, which explains the stability of the UFG structure with such small total additions. At an ultralow SiC content of 0.001 wt.%, the resulting silicide interlayers are discontinuous and serve as effective barriers to dislocations, preventing the formation of continuous brittle phases. At the same time, the released carbon partially dissolves in nickel (solid solution strengthening) and partially forms nanoscale precipitates of pyrolytic carbon, which also inhibits dislocation motion and boundary migration.

- −

- maximum contribution from grain refinement (Hall–Petch) and elongated texture;

- −

- significant solid solution strengthening;

- −

- stabilizing influence of controlled SiC decomposition (pyrolytic carbon, silicides) products without the formation of extensive brittle phases;

- −

- efficient kinetic provision of these processes due to the high diffusion mobility of carbon.

5. Conclusions

- Composites of the Ni–ySiC system (y = 0.001, 0.005, 0.015 wt.%) with improved mechanical properties were obtained by mechanical activation and spark plasma sintering at 850 °C in graphite tooling.

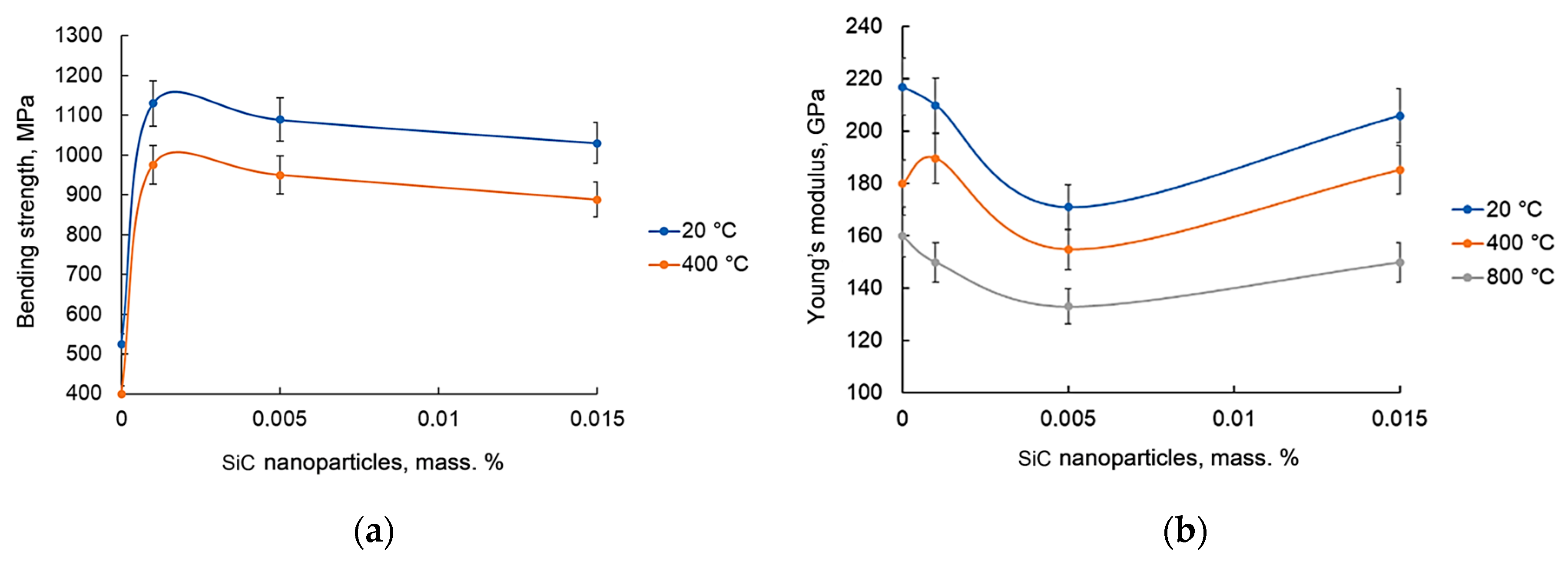

- For the Ni–0.001SiC composite, the flexural strength at 20 °C increased by 115% (to 1130 MPa) and at 400 °C by 86% (to 976 MPa) compared to sintered nickel without additives. At higher SiC contents, a decrease in strength is observed, indicating the presence of a property extremum at 0.001 wt.% nanoparticles.

- Microstructural analysis showed an ultrafine-grained structure of sintered nickel (0.15–0.4 µm), with elongated grains, the presence of pyrolytic carbon at the boundaries, and a carbon concentration in the solid solution of ~0.1–0.3 at.%. A significant part of the carbon (~6–7 at.%) is present in the form of a free phase.

- Comprehensive thermodynamic (chemical potentials) and kinetic (diffusion) modeling confirmed the possibility of SiC decomposition with the formation of free carbon and Ni silicides (Ni2Si, NiSi) at SPS temperatures. It is shown that with an increase in temperature from 300 K to 1273 K, the stability regions of nickel silicides expand, and the SiC region narrows, which thermodynamically favors reactions at the interface.

- The property extremum at 0.001 wt.% SiC is explained by the synergy of several strengthening mechanisms: solid solution (carbon), grain boundary (Hall–Petch for ultrafine-grained structure), dislocation (high dislocation density and elongated grain shape), as well as structure stabilization by the products of controlled SiC decomposition (pyrolytic carbon, silicides as hypothesis), while minimizing the negative influence of extensive brittle phases.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CVD | Chemical vapor deposition |

| DFT | Density functional theory |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

References

- Logunov, A.V. Heat-Resistant Nickel Alloys for Blades and Disks of Gas Turbines; Moskovskie Uchebniki: Moscow, Russia, 2018; p. 592. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Reed, R.C. The Superalloys: Fundamentals and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; p. 372. [Google Scholar]

- Nakada, Y.; Keh, A.S. Solid-Solution Strengthening in Ni–C Alloys. Metall. Trans. 1971, 2, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruckart, W.L.; Jaffee, R.I. Cladding of Molybdenum for Service in Air at Elevated Temperature. Trans. ASM 1952, 44, 176–198. [Google Scholar]

- Lurie, S.; Volkov-Bogorodskiy, D.; Solyaev, Y.; Rizakhanov, R.; Agureev, L. Multiscale Modelling of Aluminium-Based Metal-Matrix Composites with Oxide Nanoinclusions. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2016, 116, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostikov, V.I.; Agureev, L.E.; Eremeeva, Z.V. Development of Nanoparticle-Reinforced Alumocomposites for Rocket-Space Engineering. Russ. J. Non-Ferr. Met. 2015, 56, 325–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Roh, M.-H.; Jung, D.-H.; Jung, J.-P. Effect of ZrO2 Nanoparticles on the Microstructure of Al–Si–Cu Filler for Low-Temperature Al Brazing Applications. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2016, 47A, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaliere, P. Spark Plasma Sintering of Materials: Advances in Processing and Applications; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; p. 767. [Google Scholar]

- Borkar, T.; Banerjee, R. Influence of Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS) Processing Parameters on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Nickel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2014, 618, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Topping, T.; Bingert, J.F.; Thornton, J.J.; Dangelewicz, A.M.; Li, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Lavernia, E.J. High Tensile Ductility and Strength in Bulk Nanostructured Nickel. Adv. Mater. 2008, 20, 3028–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naimi, F.; Minier, L.; Le Gallet, S.; Couque, H.; Bernard, F.; Schoenstein, F.; Jouini, N. Dense Nanostructured Nickel Produced by SPS from Mechanically Activated Powders: Enhancement of Mechanical Properties. J. Nanomater. 2013, 2013, 712431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portnoy, K.I.; Babich, B.N. Dispersedly Hardened Materials; Metallurgiya: Moscow, Russia, 1974; 199p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Tokumitsu, K.; Umemoto, M. Formation of HCP Solid Solution in the Ni–C System by Mechanical Alloying. J. Metastable Nanocryst. Mater. 2003, 15–16, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portnoi, V.K.; Leonov, A.V.; Mudretsova, S.N.; Fedotov, S.A. Formation of Nickel Carbide in the Course of Deformation Treatment of Ni–C Mixtures. Phys. Met. Metallogr. 2010, 109, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corthay, S.; Kutzhanov, M.K.; Narzulloev, U.U.; Konopatsky, A.S.; Matveev, A.T.; Shtansky, D.V. Ni/h-BN Composites with High Strength and Ductility. Mater. Lett. 2022, 308, 131285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.; Ilavsky, J.; Huang, H.F.; Zhou, X.L.; Yang, C.; Wang, Y.Z.; Xu, H.J. Dispersed SiC Nanoparticles in Ni Observed by Ultra-Small-Angle X-ray Scattering. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2016, 49, 2155–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agureev, L.; Kostikov, V.; Eremeeva, Z.; Savushkina, S.; Ivanov, B.; Khmelenin, D.; Belov, G.; Solyaev, Y. Influence of Alumina Nanofibers Sintered by the Spark Plasma Method on Nickel Mechanical Properties. Metals 2021, 11, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuvil’deev, V.; Kopylov, V.; Zeiger, W. A Theory of Non-Equilibrium Grain Boundaries and Its Applications to Nano- and Micro-Crystalline Materials Processed by ECAP. Ann. De Chim. Sci. Des Matériaux 2002, 27, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ohji, T.; Hirano, T.; Nakahira, A.; Niihara, K. Particle/Matrix Interface and Its Role in Creep Inhibition in Alumina/Silicon Carbide Nanocomposites. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1996, 79, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorovich, V.K.; Sheftel, E.N. Dispersion Hardening of Refractory Metals; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1980. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Gottstein, G. Physical Foundations of Materials Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; p. 502. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, A.W. Substructure Strengthening Mechanisms. Metall. Trans. A 1977, 8, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugovskoi, Y.F. Effect of Structure on the Fatigue Strength of Dispersion-Hardened Condensated Based on Copper II. Analysis of the First Coefficient of the Mott–Stroh Relation. Powder Metall. Met. Ceram. 1998, 37, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taira, S.; Otani, R. Theory of High Temperature Strength of Materials; Metallurgiya: Moscow, Russia, 1986. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Manohar, P.A.; Ferry, M.; Chandra, T. Five Decades of the Zener Equation. ISIJ Int. 1998, 38, 913–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousnina, M.A.; Omrani, A.D.; Schoenstein, F.; Madec, P.; Haddadi, H.; Smiri, L.S.; Jouini, N. Spark Plasma Sintering and Hot Isostatic Pressing of Nickel Nanopowders Elaborated by a Modified Polyol Process and Their Microstructure, Magnetic and Mechanical Characterization. J. Alloys Compd. 2010, 504, S323–S327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, P.P.; Sinha, S.K.; Upadhyaya, A. Effect of Sintering Temperature on Grain Boundary Character Distribution in Pure Nickel. Scr. Mater. 2007, 56, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinaiskii, M.A.; Samokhin, A.V.; Alekseev, N.V.; Tsvetkov, Y.V. Extended Characteristics of Dispersed Composition for Nanopowders of Plasmachemical Synthesis. Nanotechnol. Russ. 2016, 11, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Huang, H.-F.; de los Reyes, M.; Yan, L.; Zhou, X.-T.; Xia, T.; Zhang, D.-L. Microstructures and Tensile Properties of Ultrafine Grained Ni–(1–3.5) wt.% SiCNP Composites Prepared by a Powder Metallurgy Route. Acta Metall. Sin. (Engl. Lett.) 2015, 28, 809–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maweja, K.; Phasha, M.; Yamabe-Mitarai, Y. Processing, Alloying and microstructural changes in platinum–titanium milled and annealed powders. J. Alloys Compd. 2012, 523, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belov, G.V.; Iorish, V.S.; Yungman, V.S. Simulation of Equilibrium States of Thermodynamic Systems Using IVTANTERMO for Windows. High Temp. 2000, 38, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belov, G.V.; Iorish, V.S.; Yungman, V.S. IVTANTERMO for Windows—Database on Thermodynamic Properties and Related Software. Calphad 1999, 23, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldshtein, M.I.; Litvinov, V.S.; Bronfin, M.F. Metallophysics of High-Strength Alloys; Metallurgia: Moscow, Russia, 1986; p. 312. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan, P.; Tendolkar, G.S. Influence of Thin Oxide Films on the Mechanical Properties of Sintered Metal-Powder Compacts. Powder Metall. 1964, 7, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, B.S. Diffusion of carbon in nickel. J. Appl. Phys. 1973, 44, 3792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourrat, X.; Langlais, F.; Chollon, G.; Vignoles, G.L. Low Temperature Pyrocarbons: A Review. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2006, 17, 1090–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Yu, S.; He, L.; Guo, Q.; Ye, H. The Interpretation of X-ray Diffraction from the Pyrocarbon in Carbon/Carbon Composites with Comparison of TEM Observations. Philos. Mag. 2012, 92, 1198–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewski, M.; Zybała, R.; Strojny-Nędza, A.; Piątkowska, A.; Dobrowolski, A.; Jagiełło, J.; Diduszko, R.; Bazarnik, P.; Nosewicz, S. Microstructural Evolution of Ni-SiC Composites Manufactured by Spark Plasma Sintering. Metall. Mater. Trans. A. 2023, 54, 2191–2207, Correction in Metall Mater Trans A 2023, 54, 3370–3371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11661-023-06999-w.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Ohashi, O.; Song, M.; Furuya, K.; Noda, T. Behavior of Oxide Film at the Interface Between Particles in Sintered Al Powders by Pulse Electric-Current Sintering. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2003, 34A, 699–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefkaier, I.K.; Bentria, E.T. The Effect of Impurities in Nickel Grain Boundary: Density Functional Theory Study. In Study of Grain Boundary Character; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, D.J.; Hamilton, J.C. Computational study of carbon segregation and diffusion within a nickel grain boundary. Acta Mater. 2005, 53, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lurie, S.; Belov, P.; Volkov-Bogorodsky, D.; Tuchkova, N. Interphase Layer Theory and Application in the Mechanics of Composite Materials. J. Mater. Sci. 2006, 41, 6693–6707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagae, T.; Yokota, M.; Nose, M.; Tomida, S.; Kamiya, T.; Saji, S. Effects of Pulse Current on an Aluminum Powder Oxide Layer During Pulse Current Pressure Sintering. Mater. Trans. 2002, 43, 1390–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.M.; Ma, E. Three Strategies to Achieve Uniform Tensile Deformation in a Nanostructured Metal. Acta Mater. 2004, 52, 1699–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Ma, Y.; Bai, Q. Effects of the Primary Carbide Distribution on the Evolution of the Grain Boundary Character Distribution in a Nickel-Based Alloy. Metals 2024, 14, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García de La Cruz, L.; Martinez, M.; Keller, C.; Hug, E. Achieving Good Tensile Properties in Ultrafine Grained Nickel by Spark Plasma Sintering. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 772, 138770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiev, R.Z.; Estrin, Y.; Horita, Z.; Langdon, T.G.; Zehetbauer, M.J.; Zhu, Y.T. Producing Bulk Ultrafine-Grained Materials by Severe Plastic Deformation. JOM 2006, 58, 33–39, Correction in JOM 2020, 3304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11837-006-0213-7.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieter, G.E. Mechanical Metallurgy; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, C.; Briones, F.; Aguilar, C.; Araya, N.; Iturriza, I.; Machado, I.; Rojas, P. Effect of Hot Pressing and Hot Isostatic Pressing on the Microstructure, Hardness, and Wear Behavior of Nickel. Mater. Lett. 2020, 273, 127944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, Q.H.; Dirras, G.; Ramtani, S.; Gubicza, J. On the Strengthening Behavior of Ultrafine-Grained Nickel Processed from Nanopowders. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2010, 527, 3227–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Vehoff, H. The Effect of Grain Size on the Mechanical Properties of Nanonickel Examined by Nanoindentation. Z. Metallkd. 2004, 95, 499–504. Available online: https://www.degruyterbrill.com/document/doi/10.1515/ijmr-2004-0099/html (accessed on 24 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Greulich, F.; Murr, L.E. Effect of Grain Size, Dislocation Cell Size and Deformation Twin Spacing on the Residual Strengthening of Shock-Loaded Nickel. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1979, 39, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseluikin, V.N. On the Structure and Properties of Composite Electrochemical Coatings. A Review. Prot. Met. Phys. Chem. Surf. 2016, 52, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Rel. Density, % | Open Porosity, % | HV0.2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ni | 98.7 | 1.1 | 70 ± 10 |

| Ni–0.001SiC | 98.4 | 1.4 | 81 ± 3 |

| Ni–0.005SiC | 98.3 | 1.5 | 92 ± 4 |

| Ni–0.015SiC | 98.2 | 1.2 | 82 ± 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Agureev, L.; Savushkina, S.; Ashmarin, A. Extreme Strengthening of Nickel by Ultralow Additions of SiC Nanoparticles: Synergy of Microstructure Control and Interfacial Reactions During Spark Plasma Sintering. Inventions 2026, 11, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/inventions11010001

Agureev L, Savushkina S, Ashmarin A. Extreme Strengthening of Nickel by Ultralow Additions of SiC Nanoparticles: Synergy of Microstructure Control and Interfacial Reactions During Spark Plasma Sintering. Inventions. 2026; 11(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/inventions11010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleAgureev, Leonid, Svetlana Savushkina, and Artem Ashmarin. 2026. "Extreme Strengthening of Nickel by Ultralow Additions of SiC Nanoparticles: Synergy of Microstructure Control and Interfacial Reactions During Spark Plasma Sintering" Inventions 11, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/inventions11010001

APA StyleAgureev, L., Savushkina, S., & Ashmarin, A. (2026). Extreme Strengthening of Nickel by Ultralow Additions of SiC Nanoparticles: Synergy of Microstructure Control and Interfacial Reactions During Spark Plasma Sintering. Inventions, 11(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/inventions11010001