Abstract

Lead (Pb) has progressively become ubiquitous due to widespread use. The liver represents a target of Pb toxicity due to its central role in metabolism and detoxification. The mechanisms of Pb hepatotoxicity have not yet been fully elucidated, although oxidative stress and iron dysregulation suggest the involvement of the ferroptosis pathway. It has been hypothesized that exposure to environmental Pb concentrations induces the activation of ferroptosis as a mechanism involved in Pb hepatotoxicity, an iron-mediated regulated cell death. To test this hypothesis, we exposed adult zebrafish to environmentally relevant Pb concentrations (2.5 and 5 μg/L), combining ultrastructural analysis (TEM) with the study of key markers of ferroptosis (GPX4, SLC7A11, NRF2, KEAP1 and ACSL4). The results demonstrated that Pb exposure induced dose-dependent and progressive mitochondrial damage in hepatocytes, characterized by loss of cristae and membrane rupture. At the same time, consistent with a ferroptotic molecular profile, increased expression of ACSL4, reduced levels of the protective factors NRF2, KEAP1 and SLC7A11, and altered expression of GPX4 were observed. Overall, our data collectively identify ferroptosis as a pathogenic pathway in Pb-induced hepatotoxicity.

Key Contribution:

Environmentally relevant lead exposure induces dose-dependent mitochondrial damage in zebrafish hepatocytes, consistent with ferroptotic ultrastructural hallmarks. Integrated ultrastructural and molecular evidence identifies ferroptosis as a key pathogenic mechanism underlying Pb-induced hepatotoxicity in zebrafish.

1. Introduction

Metal pollution represents a serious and widespread threat, with lead (Pb) among the most pervasive toxic substances. The extensive use of lead (Pb)-containing chemicals in industrial activities, such as petroleum refining, paints, plastics, and auto mechanics, has led to widespread release of this metal into the environment, contaminating soil and aquatic ecosystems [1]. Once absorbed by living organisms, Pb is not metabolically processed and tends to accumulate in organs and tissues, exerting chronic toxic effects [2]. Pb exposure was attributed to more than 1.5 million human deaths globally in 2021, primarily due to cardiovascular effects [3], and it remains a major threat to both human and animal health due to its environmental persistence and bioaccumulation. Therefore, a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying Pb toxicity is essential for predicting its biological and ecological impacts and for mitigating its effects on ecosystems.

Pb bioaccumulation patterns vary among species and tissues, with preferential deposition in metabolically active organs. The liver is a well-established target of Pb toxicity, principally due to its function as a primary metabolic and detoxification organ [4]. Several studies have reported Pb-induced detrimental effects in fish, including oxidative stress [5,6,7,8,9], morphological alterations of different organs [8,10,11,12,13], and genotoxicity [13,14,15,16]. In zebrafish (Danio rerio), we recently demonstrated that Pb exposure induced significant dose- and time-dependent liver damage, characterised by histological alterations such as congestion, cytoplasmic vacuolization, and macrophage proliferation, alongside an increase in hepatic lipid content [12]. These findings parallel those observed in mammalian models, suggesting that Pb-induced hepatotoxic mechanisms are conserved across vertebrates [17,18].

Ferroptosis is a regulated, iron-dependent form of non-apoptotic cell death characterised by the excessive accumulation of lipid peroxides on polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) within cell membranes [19,20]. Unlike apoptosis, necroptosis, or autophagy, ferroptosis is mechanistically driven by redox imbalance, iron overload, and impaired antioxidant defenses [21,22]. A dynamic equilibrium between pro- and anti-ferroptotic factors governs the process. Among the key mediators, Acyl-CoA Synthetase Long-Chain Family Member 4 (ACSL4) facilitates the incorporation of PUFAs into phospholipids, rendering them susceptible to peroxidation [23]. Conversely, the cystine/glutamate antiporter system Xc−, composed of the SLC7A11 subunit, imports cystine for glutathione (GSH) synthesis; glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) detoxifies lipid hydroperoxides; and the NRF2–KEAP1 pathway orchestrates antioxidant gene expression under oxidative stress [24,25,26].

Increasing evidence implicates ferroptosis in the pathogenesis of metal toxicity. Pb exposure disrupts redox homeostasis by depleting GSH and downregulating key antioxidant enzymes, thereby promoting lipid peroxidation [27,28]. Pb can also increase intracellular iron levels by inhibiting ferroportin-1 and suppressing amyloid precursor protein translation, further enhancing oxidative reactions via the Fenton mechanism [29,30]. Recent studies have directly associated Pb exposure with ferroptotic neurodegeneration in mammalian systems [31,32], suggesting that this pathway may play a broader toxicological role across tissues and species.

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) provide a suitable vertebrate model for investigating hepatic ferroptosis in environmental toxicology, particularly in relation to redox imbalance and lipid peroxidation pathways conserved across vertebrates [33,34]. In zebrafish, hepatic ferroptosis has been induced by iron overload and chemical stressors, with characteristic mitochondrial shrinkage, iron accumulation, and lipid peroxidation [35,36]. Moreover, previous studies have shown that exposure to metals in zebrafish and other teleosts can disrupt key anti-ferroptotic defenses, including suppression of the SLC7A11–GPX4 axis and impairment of NRF2–KEAP1 signaling, alongside upregulation of ACSL4—molecular signatures consistent with ferroptotic cell death [36,37].

Based on the evidence reported above, we hypothesized that Pb exposure induces liver toxicity through ferroptotic mechanisms. To test this hypothesis, zebrafish were exposed to environmentally relevant concentrations of Pb, and hepatic ferroptosis was investigated using ultrastructural and molecular approaches.

Because ferroptosis is associated with distinctive ultrastructural mitochondrial changes, including membrane condensation and cristae loss [38], transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was employed to assess the presence of these alterations. This analysis was complemented by molecular profiling of key ferroptosis-related markers—GPX4, SLC7A11, NRF2, KEAP1, and ACSL4—to explore whether Pb exposure modulates the canonical molecular pathways of ferroptosis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Zebrafish Husbandry

A total of 42 wild-type adult zebrafish (6–8 months old; length: 3.5 ± 0.5 cm; weight: 0.43 ± 0.06 g) of both sexes were obtained from a local supplier (Rosario, Argentina). Fish were acclimated for two weeks in aquaria containing dechlorinated tap water under controlled conditions: temperature 26 ± 0.5 °C, pH 7.3 ± 0.4, conductivity 300 ± 50 µS/cm, dissolved oxygen 8 ± 1 mg/L, hardness 100 ± 5 mg/L CaCO3, and a 14:10 h light/dark photoperiod. All values are reported as mean ± SD. During acclimation, fish were fed twice daily with commercial tropical fish food (Prodac, Cittadella, Italy).

2.2. Exposure Protocol

2.2.1. Test Substance

Two sublethal concentrations of lead acetate, 2.5 and 5 μg/L, were selected for this study. A stock solution of lead acetate [Pb(CH3CO2)2·3H2O] (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) was prepared at a concentration of 1000 μg/L in distilled water. Working solutions were then obtained by diluting the stock solution in dechlorinated tap water to achieve the desired nominal concentrations.

Lead concentrations in the experimental media were quantified using an Elan DRC-e Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometer (ICP–MS) (PerkinElmer SCIEX, Woodbridge, ON, Canada) as described by Macirella et al. [12]. Briefly, water samples were acidified with 500 µL of ultrapure nitric acid and analysed with a PerkinElmer AS-93 plus autosampler and a cross-flow nebuliser coupled to a Scott-type spray chamber. Quantification was performed by external calibration using a five-point standard curve within the range of 0.1–50 μg/L. Analytical verification of Pb levels was conducted at the beginning of the exposure and subsequently every 24 h throughout the experimental period, and no significant deviations from the nominal concentrations were detected (Appendix A).

The chosen exposure levels (2.5 and 5 μg/L) fall within the range of Pb concentrations typically detected in surface waters worldwide and therefore represent environmentally relevant conditions [39]. These concentrations correspond to approximately 0.0015% and 0.0030% of the 96 h LC50 for adult zebrafish (171 mg/L) [40], ensuring sublethal exposure conditions. Since wider concentration ranges often shift cellular responses toward necrosis or apoptosis, which would undermine the study’s objective of identifying early ferroptotic signatures, this relatively narrow interval was chosen to detect dose-dependent ultrastructural progression under environmentally realistic conditions and to avoid inducing overt toxicity that would obscure early ferroptotic features.

2.2.2. Experimental Design

The minimum number of animals required for this study was determined using G*Power 3.1.9.7 Software (Franz Faul, Universität Kiel, Kiel, Germany), following the ‘a priori’ method. The expected effect size and variability used for the a priori power analysis were estimated based on previously published morphometric and molecular data obtained from zebrafish liver following exposure to environmentally relevant Pb concentrations under comparable experimental conditions [12]. A total of 42 fish were randomly distributed among three experimental groups: control, low Pb concentration (2.5 μg/L), and high Pb concentration (5 μg/L). Each group consisted of 14 fish, maintained in 30 L glass aquaria (40 × 32 × 20 cm) under continuous aeration. Exposure was conducted using a static renewal system, in accordance with OECD guidelines [41,42], with minor adjustments. Test solutions were renewed every 24 h to maintain consistent exposure conditions. The experimental duration was 96 h, during which all physicochemical parameters (temperature, pH, conductivity, dissolved oxygen, and photoperiod) were measured daily and maintained within the range established during acclimatization. Fish were not fed throughout the exposure period to prevent contamination and interference from waste products.

At the end of the exposure period (96 h), fish were euthanized following a two-step anesthesia protocol: first, immersion in buffered tricaine methane sulfonate (MS-222, 0.20 mg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 10–30 s, followed by hypothermic shock in ice-chilled water (0–4 °C) for 10 min. Liver tissues were carefully excised and immediately processed for morphological and molecular analyses. The entire experiment was independently replicated three times, and no mortality occurred in any group during the exposure period.

2.3. Ultrastructural Examination

For ultrastructural analysis, seven animals per experimental group were examined as described by Ahmed et al. [43]. Briefly, liver samples were rapidly excised and fixed for 3 h in 3% glutaraldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA) prepared in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 0.1 M, pH 7.2), followed by post-fixation in 2% osmium tetroxide (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA) for 2 h at 4 °C. Subsequently, tissues were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, infiltrated with propylene oxide, and embedded in Epon–Araldite resin (Araldite 502/Embed 812, Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA). Ultra-thin sections (approximately 800 Å) were stained with a uranyl acetate substitute and counterstained with lead citrate (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA), and then examined using a JEM 1400 PLUS transmission electron microscope (JEOL, Peabody, MA, USA).

2.4. Morphometric Analysis

TEM images were analyzed in ImageJ 1.53k software (NIH, developed at the National Institutes of Health, a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services) as described by Lam et al. [44], to calculate mitochondrial area, mitochondrial cristae area, and mitochondrial cristae number. Briefly, ImageJ was used to load and read TIFF-formatted images. The “set scale” option from the “Analyze” tab was first used to establish the scale (1 pixel = 1 nm for all images). Then, a freehand tool was used to trace and outline each mitochondrion and cristae structure. The ROI manager was used to store the measurements. After outlining all mitochondria and cristae structures, the measurements were acquired by clicking “measure” in the ROI manager. At least 30 mitochondria were analyzed for each group.

2.5. Western Blotting

Liver tissues from seven zebrafish of each experimental group destined for Western blot analysis were homogenized and lysed in ice-cold RIPA buffer (RIPA Lysis Buffer, Cat. No. 89900, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF; Cat. No. P7626, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (cOmplete™ Mini EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail, Cat. No. 11836170001, Roche, Basel, Switzerland).

Protein concentration of the lysates was determined using the Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (Cat. No. 23225, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Equal amounts of protein (typically 20–40 µg) from each sample were separated by SDS-PAGE and subsequently transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Immobilon-P, Cat. No. IPVH00010, Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA).

After blocking in 5% non-fat dry milk (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) prepared in TBS with 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T) for 1 h at room temperature, membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary antibodies from the Ferroptosis Essentials Antibody Kit (Cat. No. PK30002, Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, USA).

Following three washes with TBS-T, membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies: goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP (Cat. No. ab97023, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (HRP, Cat. No. ab97080, Abcam, Cambridge, UK).

Immune complexes were visualized using the Clarity™ Western ECL Substrate (Cat. No. 1705061, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and imaged with a ChemiDoc™ MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Western blots were normalized using GAPDH (anti-GAPDH antibody; Cat. No. ab9485as, Abcam) a loading control. Densitometric analysis was performed using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

2.6. Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 8.00 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The level of significance was set at 0.05. Normality and homogeneity of variance were assessed prior to inferential testing. Since no significant differences were detected among independent experimental replicates for any morphometric or protein expression parameter (Mann–Whitney test, p > 0.05), replicate datasets were pooled. Treatment effects were then analyzed using parametric one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test, consistent with the a priori power analysis. Homogeneity of variances was verified in all cases using the Brown–Forsythe test.

3. Results

3.1. Ultrastructural Analysis

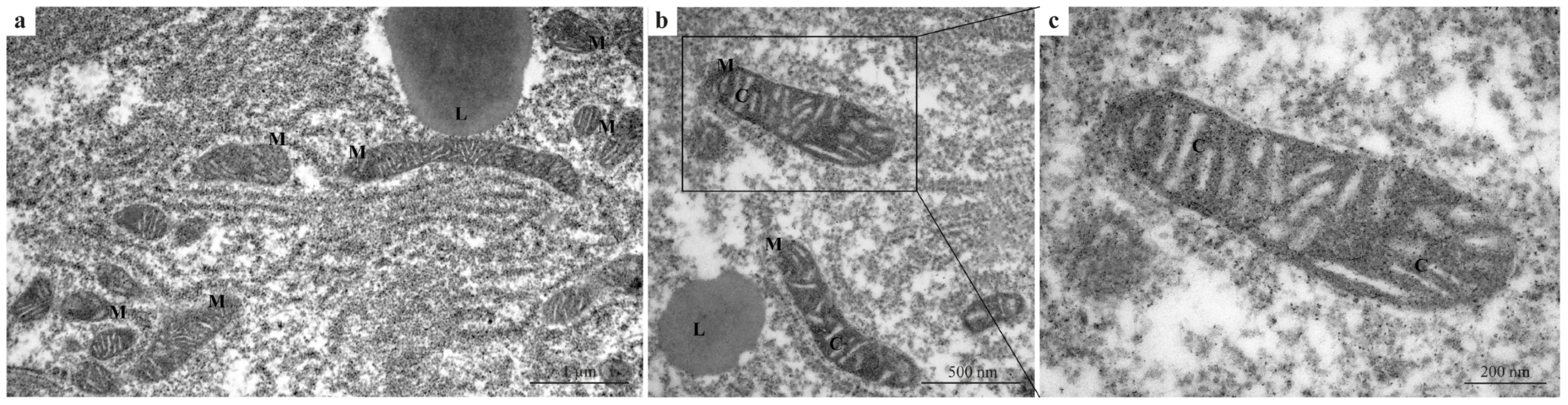

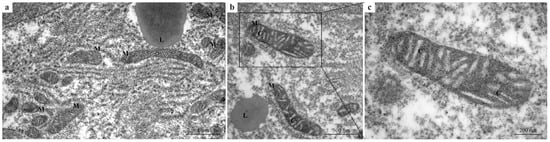

In the control group, hepatocytes exhibited normal ultrastructural organization with well-preserved cellular components (Figure 1a–c), providing a reference baseline for comparison with treated groups. Mitochondria showed intact double membranes, densely packed cristae, and uniform electron density (Figure 1a,b). The cytoplasm appeared homogeneous, with no evidence of vacuolization or organelle disruption (Figure 1a,b). At higher magnification (Figure 1c), mitochondria exhibited an elongated shape with clearly defined inner membranes and densely packed cristae, indicative of healthy mitochondrial function.

Figure 1.

TEM micrographs of zebrafish liver from the control group. (a–c) Hepatocytes with normal ultrastructural organization. (a,b) Mitochondria showing intact double membranes, well-defined and densely packed cristae, and homogeneous electron density. (b) Normal cytoplasm organization. (c) Higher magnification of a mitochondrion showing the densely packed cristae. M = mitochondria; L = lipid droplets; C = cristae.

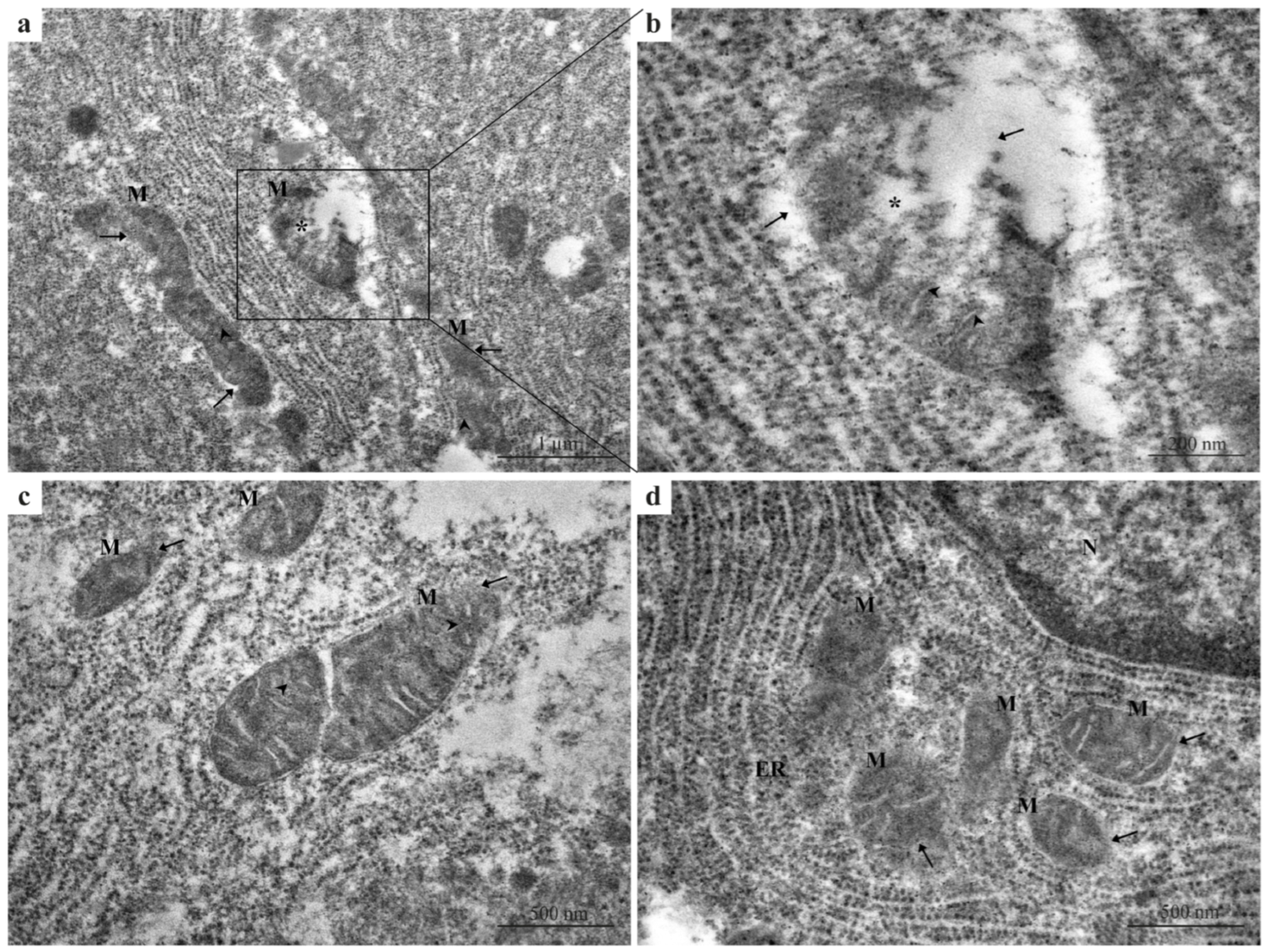

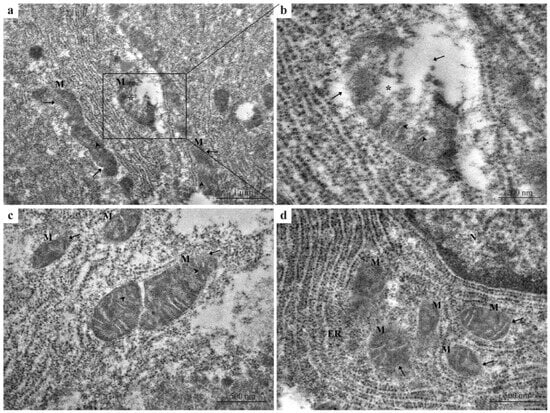

Hepatocytes from the 2.5 µg/L Pb-exposed group exhibited early degenerative changes compared with the control group (Figure 2a–d). These changes included mild mitochondrial swelling and partial disorganization of cristae (Figure 2a,b) compared with the intact membranes and densely packed cristae observed in control hepatocytes. Irregularities and partial ruptures of the outer mitochondrial membrane were frequently observed (Figure 2b). Mitochondria also showed elongated or contracted profiles with dense matrices and shrunken morphology (Figure 2c) deviating from the uniform mitochondrial morphology seen in the control.

Figure 2.

TEM micrographs of zebrafish liver exposed to 2.5 μg/L Pb. (a–d) Hepatocytes with early degenerative ultrastructural changes compared with the control group. (a) Mild mitochondrial swelling and partial disorganization of cristae. (b) A higher magnification image highlighting irregular mitochondrial morphology and partial rupture of the outer mitochondrial membrane. (c) Mitochondria displaying elongated or contracted morphology, dense matrices, and a shrunken appearance. (d) Multiple damaged mitochondria surrounded by disorganized ER membranes, showing increased electron density and fragmented cristae. Black arrows = damaged or absent outer mitochondrial membrane; M = mitochondria; black arrowheads = disorganized cristae; black asterisks = mitochondrial swelling; ER = endoplasmic reticulum; N = nucleus.

Additionally, in several cells, multiple damaged mitochondria were surrounded by disorganized endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membranes (Figure 2d), accompanied by increased electron density and fragmented cristae.

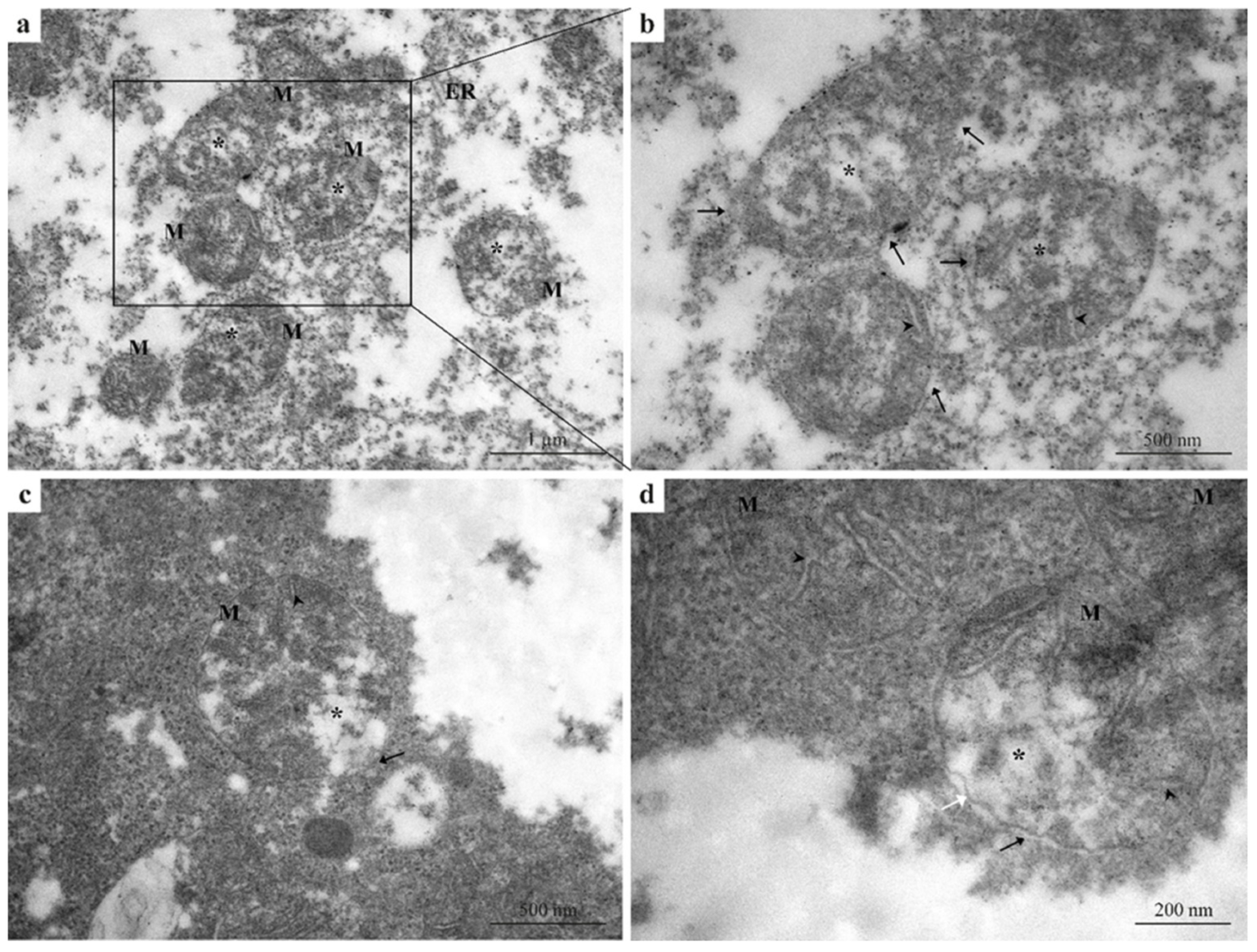

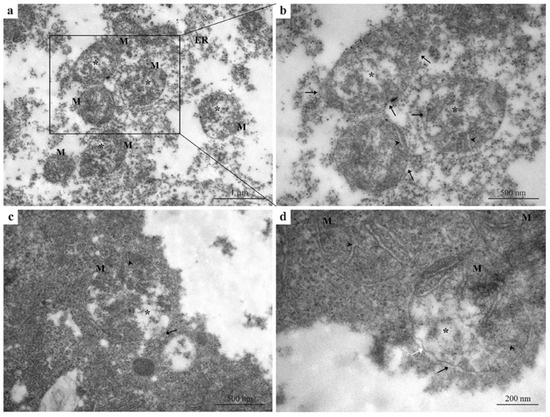

Exposure to 5 µg/L Pb induced pronounced ultrastructural damage in hepatocytes compared with both the control group (Figure 1a–c) and the 2.5 µg/L Pb-exposed group (Figure 2a–d). Hepatocytes displayed extensive cytoplasmic disorganization and markedly dilated rough endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Figure 3a,b), indicating a clear progression in cellular injury with increasing Pb concentration. All mitochondria examined showed severe structural alteration and their typical morphology was destroyed relative to the milder changes observed at 2.5 µg/L Pb. Prominent mitochondrial swelling, damaged outer mitochondrial membranes, disrupted or fragmented cristae, and electron-lucent matrices were the main pathological signs observed (Figure 3a–d). Moreover, the inner membrane structure appeared largely disorganized and, in some regions, the membrane showed discontinuities or irregular contours (Figure 3d). These pronounced alterations reflect progressive mitochondrial and ER degeneration in response to increasing Pb exposure and are readily distinguishable when compared across treatment groups.

Figure 3.

TEM micrographs of zebrafish liver exposed to 5 µg/L Pb. (a,b) Hepatocytes showing pronounced cytoplasmic disorganization and markedly dilated rough endoplasmic reticulum, compared with both control (Figure 1) and 2.5 µg/L Pb-exposed groups (Figure 2). (a–d) Mitochondria displaying severe morphological alterations, including swelling, disrupted or fragmented cristae, electron-lucent matrices, and damaged outer membranes. (d) Inner mitochondrial membrane with discontinuities and irregular contours in some regions. Black arrows = damaged or absent outer mitochondrial membrane; white arrow = irregular inner mitochondrial membrane; M = mitochondria; black arrowheads = disorganized cristae; black asterisks = mitochondrial swelling; ER = endoplasmic reticulum.

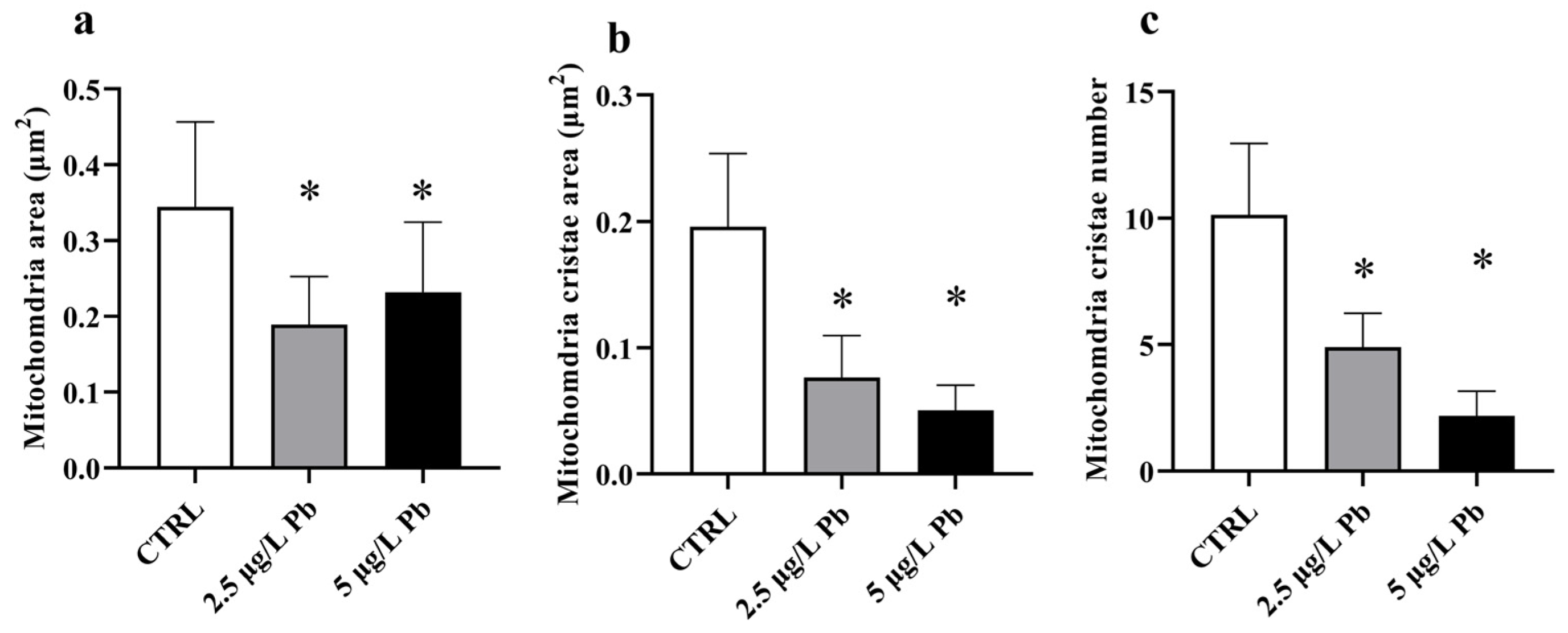

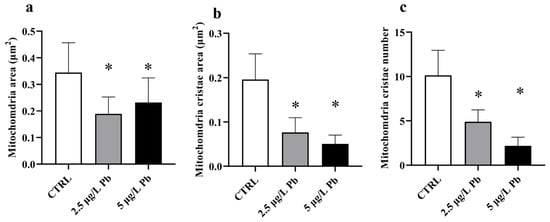

Quantitative morphometric analysis of mitochondrial ultrastructure confirmed the ultrastructural observations (Figure 4a–c). Both Pb-exposed groups exhibited a significant reduction in mitochondrial area compared to the control (F (2, 75) = 21.36; p < 0.0001; Figure 4a), consistent with a mitochondrial shrinkage as a result of Pb exposure. Mitochondrial cristae area was significantly decreased in both treatment groups, with a further reduction at 5 µg/L Pb (F (2, 82) = 105.1; p < 0.0001; Figure 4b). Similarly, the number of cristae was markedly lower in both Pb-exposed groups compared to the control (F (2, 85) = 130.8; p < 0.0001; Figure 4c), reaching the minimum values in the 5 µg/L group.

Figure 4.

Quantitative morphometric analysis of mitochondrial ultrastructure in zebrafish liver following Pb exposure. (a) Mitochondrial area, (b) mitochondrial cristae area, and (c) mitochondrial cristae number in control and Pb-exposed groups. Pb exposure resulted in statistically significant alterations in all measured parameters compared with the control group, with more pronounced effects observed at the higher Pb concentration. Data are presented as mean ± SD. * indicates a statistically significant difference relative to the control group (p < 0.05).

3.2. Western Blot Analysis

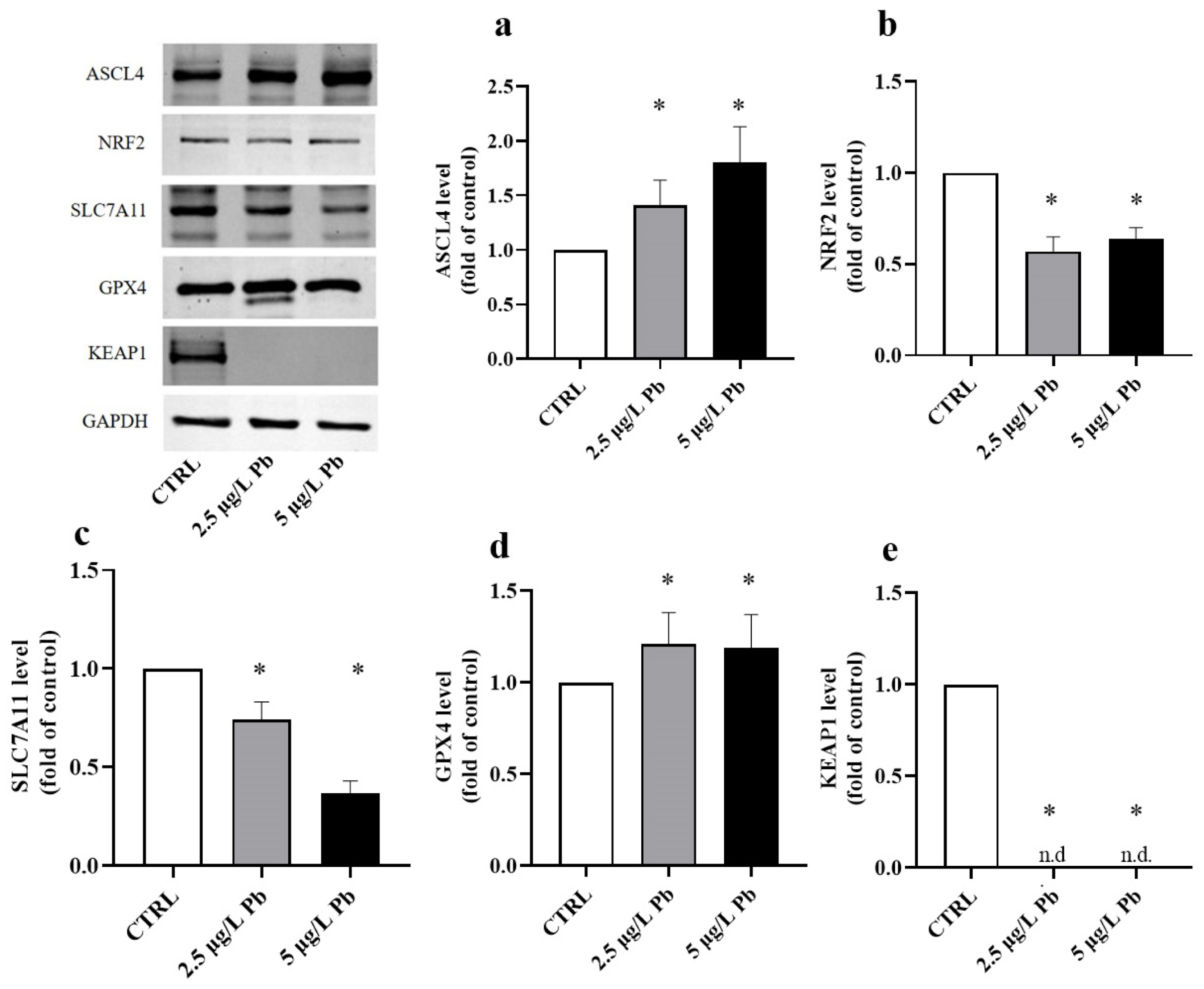

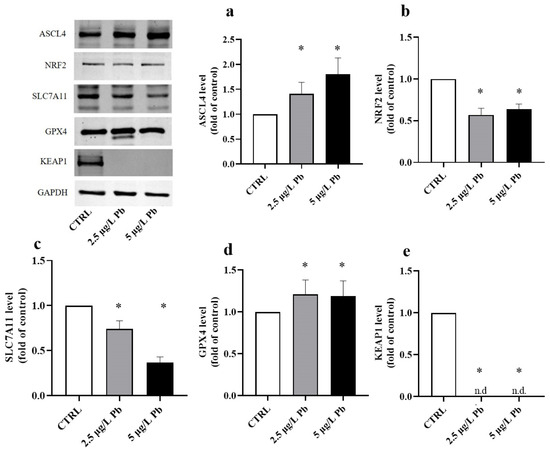

To investigate how Pb exposure affects oxidative stress responses and ferroptotic susceptibility, we quantified the protein expression of key components of the NRF2/KEAP1 pathway and ferroptosis regulators by Western blot. Protein levels were normalized to GAPDH and expressed as fold change (FC) relative to the untreated CTRL (set to 1). Our results showed that Pb exposure strongly promotes a pro-ferroptotic cellular environment (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effects of lead (Pb) exposure on ASCL4, NRF2, SLC7A11, GPX4, and KEAP1 protein expression in zebrafish liver. Quantification of protein levels normalized to GAPDH and expressed as fold change relative to the control group (CTRL). Pb exposure significantly increased ASCL4 (a) and GPX4 (d) protein levels, while markedly decreasing NRF2 (b), SLC7A11 (c), and KEAP1 (e) expression in liver tissue. Data are presented as mean ± SD. * indicates a statistically significant difference relative to the control group (p < 0.05), n.d.: not detectable.

Pb exposure caused a clear upregulation of ACSL4, a pro-ferroptotic enzyme that plays a role in lipid peroxidation (F (2, 18) = 29.29; p < 0.0001; Figure 5a). Treatment with 2.5 μg/L Pb (Figure 5a) increased the amount of ACSL4 by 1.41-fold relative to the CTRL (p < 0.01). The increase became more pronounced in the group treated with 5 μg/L Pb (Figure 5a), where ACSL4 levels rose 1.80-fold control values (p < 0.0001). The significant difference between the two Pb concentrations (p < 0.05) confirms a clear dose-dependent trend (Figure 5a).

In line with this oxidative shift, NRF2, the major transcriptional regulator of redox responses, was significantly downregulated by Pb exposure (F (2, 18) = 90.31; p < 0.0001; Figure 5b). Although no significant difference was observed between the two different doses of Pb (2.5 μg/L Pb vs. 5 μg/L: p > 0.05; Figure 5b), NRF2 levels were strongly reduced by 0.57-fold in the 2.5 μg/L Pb group and by 0.64-fold in the 5 μg/L Pb group compared to CTRL (p < 0.0001 for both; Figure 5b).

Consistently, SLC7A11, which is essential for glutathione synthesis and for sustaining the antiferroptotic activity of GPX4, also was greatly reduced upon exposure to Pb (F (2, 18) = 214.0; p < 0.0001; Figure 5c). Its expression decreased to 0.73-fold at 2.5 μg/L Pb and further decreased to 0.37-fold at 5 μg/L Pb with respect to the control (p < 0.0001 for both; Figure 5c). The strongly marked reduction in protein levels in the group treated with the highest dose of lead (2.5 μg/L Pb vs. 5 μg/L: p < 0.0001) indicates clear Pb dose-dependent downregulation of SLC7A11 (Figure 5c).

Notably, despite the dose-dependent reduction of SLC7A11, GPX4 protein level was upregulated after Pb exposure (F (2, 18) = 6.476; p = 0.0076; Figure 5d). GPX4 was upregulated by 1.20-fold at concentrations of 2.5 μg/L Pb (p < 0.05; Figure 5d). The induction response of GPX4 at a dose of 5 μg/L (Figure 5d), although remarkably significant compared to the CTRL (1.19 FC; p < 0.05), did not produce any increase compared to that induced by the lower dose (p > 0.05).

KEAP1, as a cytosolic inhibitory regulator of NRF2, was evaluated for its protein expression levels after Pb exposure (F (2, 18) = 2800; p < 0.0001; Figure 5e). KEAP1 was present but barely detectable in the two Pb-exposed groups, while it was easily detectable within the control group (p < 0.0001; Figure 5e).

4. Discussion

Environmental exposure to lead (Pb) remains a critical toxicological concern for aquatic organisms, yet the cellular pathways mediating Pb-induced liver injury are incompletely defined. In the present study, we demonstrate that environmentally relevant Pb concentrations activate a ferroptotic program in zebrafish hepatocytes, integrating ultrastructural mitochondrial damage with disruption of antioxidant and lipid-metabolic regulatory pathways. These findings extend previous research, which has shown that Pb induces oxidative stress and hepatic injury in fish [4,12], and align with recent studies indicating that ferroptosis is a central mechanism of metal-induced toxicity [31,45].

In particular, mitochondria represent a critical hub in ferroptosis, serving as both sources and targets of lipid peroxidation. Ferroptotic cell death is distinguished ultrastructurally by mitochondrial shrinkage, loss of cristae, and membrane disruption, features that differ fundamentally from apoptotic or necrotic degeneration. The mitochondrial ultrastructural alterations observed in Pb-exposed zebrafish livers closely align with the typical defining characteristics of ferroptotic mitochondria [19,20,38], suggesting that mitochondrial failure is not a secondary consequence, but a core event in Pb-induced ferroptosis. Our results closely resemble ferroptotic mitochondrial signals previously observed in the liver of zebrafish [36,46,47,48] and other teleosts [35,37,45,49,50].

In fact, a progressive mitochondrial structural collapse is a defining ultrastructural hallmark of ferroptosis and reflects failure of bioenergetic and redox homeostasis. Moreover, ferroptosis-associated mitochondrial morphometric alterations, similar to those observed in this study, have been previously reported in vitro and in vivo [48,51,52] and are fully consistent with lipid-peroxidation-driven mitochondrial collapse, where PUFA-enriched membranes become vulnerable to oxidative degradation [23].

Beyond mitochondrial damage, ferroptosis involves coordinated dysfunction of multiple organelles, with a particular regard to dilation of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Because the ER regulates lipid metabolism, calcium homeostasis, and protein folding, it plays a critical role in determining ferroptotic susceptibility [53,54]. Moreover, ER stress is well known to activate the unfolded protein response (UPR) through the transmembrane sensors PERK, IRE1α, and ATF6, which initially function to restore ER homeostasis [54,55]. However, under sustained stress, UPR signalling can shift toward pro-ferroptotic pathways, thereby promoting ferroptosis [55].

Therefore, ER dilation likely reflects a transition from an early adaptive response to a maladaptive, pro-ferroptotic state. Pb exposure is also known to increase ROS generation [56,57]. This can activate PERK and exacerbate ER dysfunction [58], while ROS produced during ferroptosis may further impair protein-folding capacity, creating a positive feedback loop between ER stress and ferroptotic progression [59]. This interplay between mitochondrial damage, lipid peroxidation, and ER stress suggests that Pb initiates a multi-organelle cascade culminating in ferroptotic cell death once oxidative stress exceeds the cell’s compensatory capacity, a hypothesis that warrants future mechanistic investigation.

We did not perform direct antioxidant system measurements (e.g., enzymatic activity assays, GSH quantification), since the scope of this study was to reveal morphological and mechanistic evidences. Nevertheless, the proteins analysed represent central regulatory nodes of the cellular antioxidant and ferroptosis defense systems (see, e.g., refs. [23,24,25,26,27,28]), and their observed modulation provides validated indirect evidence of antioxidant imbalance.

Our molecular data provide strong evidence that Pb induces a ferroptosis-like pathway in hepatocytes. The ferroptosis process is characterized by a particular type of lipid peroxidation whose main target is phosphatidylethanolamines [60]. The ACSL4 enzyme has the role of activating long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids and incorporating them into membrane lipids, particularly phosphatidylethanolamines [60]. Thus, ACSL4 determines the cellular abundance of lipid substrates susceptible to peroxidation, acting as a positive regulator of ferroptotic cell death and its cellular expression is a valuable molecular marker to monitor the activation of this pathway [61]. In this study, a statistically significant increase in ACSL4 levels was observed in response to Pb exposure at each concentration tested. Furthermore, the significant difference in ACSL4 expression observed between the different Pb concentrations (2.5 and 5 μg/L) strengthens the hypothesis that disruption of lipid metabolism is a central event in Pb-mediated toxicity. The upregulation of ACSL4 by Pb in an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis model [62] suggests a conserved cellular response that extends beyond specific pathologies. This conservation is evidenced by similar effects induced by other toxic metals, including arsenic and cadmium [63,64], strongly supporting ACSL4-mediated ferroptosis as a common pathway in metal-induced cytotoxicity.

The xCT transporter is a heterodimeric complex whose functional subunit SLC7A11 serves as a crucial cystine/glutamate antiporter. SLC7A11 mediates cellular uptake of cystine in exchange for intracellular glutamate efflux [65]. Once imported, cystine is rapidly reduced to cysteine, which is an essential precursor for glutathione (GSH). GSH, in turn, is a key cofactor for GPX4, whose activity neutralizes lipid hydroperoxides and thereby prevents ferroptosis [66].

Given the central role of the NRF2/SLC7A11 axis in ferroptosis defense, we hypothesized that Pb toxicity compromises this pathway to promote cellular damage. Consistent with this, Pb exposure caused a dose-dependent reduction in SLC7A11 protein expression in zebrafish, identifying cystine import as an early and highly sensitive target of Pb-induced stress. Our data are in line with other studies showing Pb-mediated repression of SLC7A11 expression [45,62] and can relate to our own observations on reduced NRF2 expression [67]. Indeed, NRF2 is recognized as one of the primary regulators of antioxidant responses and directly controls SLC7A11 transcription through its promoter region [68]. Hence, Pb-mediated repression of NRF2 likely provides the basis for reduced SLC7A11 expression, resulting in a cellular cysteine/GSH deficiency. This sequence of events offers a molecular mechanism for the well-documented ability of Pb to disrupt redox homeostasis by reducing GSH and downregulating antioxidant pathways [69,70], which our findings in zebrafish liver strongly support.

After establishing Pb-induced suppression of the NRF2/SLC7A11 axis, we evaluated the impact of exposure on the terminal ferroptosis defense enzyme, GPX4. Interestingly, and seemingly in contrast with the suppression of this axis, we observed a moderate upregulation of GPX4 protein levels. Similar observations have been reported in other models, where GPX4 protein levels remained high but were insufficient to prevent ferroptosis. Specifically, Coornaert et al. [71] demonstrated that GPX4 overexpression in ApoE knockout mice failed to protect against ferroptotic cell death. Furthermore, inducible GPX4 isoforms can accumulate to high levels while remaining functionally inadequate to inhibit ferroptosis [72]. This functional insufficiency in our model is supported by the severe mitochondrial alterations observed via transmission electron microscopy in Pb-treated groups. It is therefore hypothesized that the Pb-mediated reduction in NRF2/SLC7A11 expression leads to reduced GSH levels, which compromises GPX4 function despite its upregulation.

In parallel, protein levels of KEAP1, the canonical repressor of NRF2, were also barely detectable following Pb exposure. Under oxidative stress conditions, NRF2 detached from KEAP1 translocated to the nucleus and triggered antioxidant response in cells by activating cytoprotective genes [73]. However, in our model, we observed a reduction in KEAP1 accompanied by a concomitant decrease in NRF2, a finding consistent with previous studies [74,75]. One possible explanation behind this simultaneous reduction could be the transcription of miR-153 through the effect of Pb, which directly targets the mRNA of NRF2 without following the regulatory system of KEAP1 [75]. Further investigation is required to fully elucidate the alternative KEAP1-independent pathways through which Pb suppresses NRF2.

5. Conclusions

Together, our findings demonstrate that Pb exposure induces ferroptosis-like pathway in zebrafish hepatocytes through mitochondrial destabilization, impaired antioxidant defenses, and ACSL4-driven lipid peroxidation. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study providing combined ultrastructural (TEM) and ferroptosis-related molecular evidence in zebrafish liver following Pb exposure at environmentally realistic concentrations.

Further work should assess whether ferroptosis inhibitors, such as lipophilic antioxidants or ACSL4 inhibitors, can alleviate Pb-induced damage. Investigating Pb-induced alterations in iron metabolism through direct lipid peroxidation and iron measurements may also help clarify upstream events triggering ferroptosis in aquatic organisms. Future analysis should also test sex-dependent susceptibility to ferroptosis using a dedicated experimental design.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.B. and M.M.; methodology, F.T.; formal analysis, F.T.; investigation, I.O. and A.I.M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, I.O. and A.I.M.A.; writing—review and editing, E.B.; supervision, E.B. and M.M.; project administration, E.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the National University of Entre Ríos and the Italian University Institute of Rosario (Rosario, Argentina; protocol N°028/12, issued on 30 November 2012).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GSH | Glutathione |

| ALS | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| UPR | Unfolded protein response |

| FC | Fold change |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene difluoride |

| PMSF | Phenylmethylsulfonyl |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| MS-222 | Tricaine methane sulfonate |

| OECD | Organisation for economic co-operation and development |

| ICP-MS | Inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometer |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| PUFAs | Polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| GPX4 | Glutathione peroxidase 4 |

| SLC7A11 | Solute carrier family 7, member 11 |

| NRF2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| KEAP1 | Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 |

| ACSL4 | Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family 4 |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Measured Pb concentrations in the control group and exposure solutions. The values are presented as (mean ± SEM, n = 9).

Table A1.

Measured Pb concentrations in the control group and exposure solutions. The values are presented as (mean ± SEM, n = 9).

| Nominal Concentration (μg/L) | Measured Concentration (μg/L) |

|---|---|

| CTRL | 0.03 ± 0.02 |

| 2.5 µg/L | 2.47 ± 0.08 |

| 5 µg/L | 4.94 ± 0.06 |

References

- Mishra, P.; Ali, S.; Kumar, R.; Shekhar, S. Global Lead Contamination in Soils, Sediments, and Aqueous Environments: Exposure, Toxicity, and Remediation. J. Trace Element Miner. 2025, 14, 100259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Villalva, A.; Marcela, R.L.; Nelly, L.V.; Patricia, B.N.; Guadalupe, M.R.; Brenda, C.T.; Eugenia, C.V.M.; Martha, U.C.; Isabel, G.P.; Fortoul, T.I. Lead systemic toxicity: A persistent problem for health. Toxicology 2025, 515, 154163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Lead Poisoning and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lead-poisoning-and-health (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Oros, A. Bioaccumulation and trophic transfer of heavy metals in marine fish: Ecological and ecosystem-level impacts. J. Xenobiotics 2025, 15, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Liu, S.; Fu, L.; Du, H.; Xu, Z. Lead (Pb) accumulation, oxidative stress and DNA damage induced by dietary Pb in tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquac. Res. 2012, 43, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firidin, G. Oxidative stress parameters, induction of lipid peroxidation, and ATPase activity in the liver and kidney of Oreochromis niloticus exposed to lead and mixtures of lead and zinc. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2018, 100, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zheng, Y.G.; Feng, Y.H.; Li, M.Y.; Wang, G.Q.; Ma, Y.F. Toxic effects of waterborne lead (Pb) on bioaccumulation, serum biochemistry, oxidative stress and heat shock protein-related genes expression in Channa argus. Chemosphere 2020, 261, 127714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Pu, Y.; Zhong, L.; Wang, K.; Duan, X.; Chen, D. Lead impaired immune function and tissue integrity in yellow catfish (Peltobargus fulvidraco) by mediating oxidative stress, inflammatory response and apoptosis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 226, 112857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Kong, Y.; Wu, X.; Yin, Z.; Niu, X.; Wang, G. Dietary α-lipoic acid can alleviate the bioaccumulation, oxidative stress, cell apoptosis, and inflammation induced by lead (Pb) in Channa argus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2021, 119, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curcio, V.; Macirella, R.; Sesti, S.; Ahmed, A.I.M.; Talarico, F.; Tagarelli, A.; Mezzasalma, M.; Brunelli, E. Morphological and functional alterations induced by two ecologically relevant concentrations of Lead on Danio rerio gills. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahi, T.F.; Chowdhury, G.; Hossain, M.A.; Baishnab, A.K.; Schneider, P.; Iqbal, M.M. Assessment of lead (Pb) toxicity in juvenile Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus—Growth, behaviour, erythrocytes abnormalities, and histological alterations in vital organs. Toxics 2022, 10, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macirella, R.; Curcio, V.; Ahmed, A.I.M.; Talarico, F.; Sesti, S.; Paravani, E.; Odetti, L.; Mezzasalma, M.; Brunelli, E. Morphological and functional alterations in zebrafish (Danio rerio) liver after exposure to two ecologically relevant concentrations of lead. Fishes 2023, 8, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryam, S.; Naz, H.; Ahmed, T.; Omran, A.; Alanazi, Y.F.; Usman, M.; Ijaz, M.U.; Ali Shah, S.Q.; Qazi, A.A.; Ali, B.; et al. Determination of histological and genotoxic parameters of Nile Tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus exposed to lead (Pb). Cell. Mol. Biol. 2023, 69, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsdorf, W.A.; Ferraro, M.V.M.; Oliveira-Ribeiro, C.A.; Costa, J.R.M.; Cestari, M.M. Genotoxic evaluation of different doses of inorganic lead (PbII) in Hoplias malabaricus. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2009, 158, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, V.; Cavalcante, D.G.S.M.; Viléla, M.B.F.A.; Sofia, S.H.; Martinez, C.B.R. In vivo and in vitro exposures for the evaluation of the genotoxic effects of lead on the Neotropical freshwater fish Prochilodus lineatus. Aquat. Toxicol. 2011, 104, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, K.K.; Mondal, P.; Chattopadhyay, A. Environmentally relevant lead alters nuclear integrity in erythrocytes and generates oxidative stress in liver of Anabas testudineus: Involvement of Nrf2-Keap1 regulation and expression of biomarker genes. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2024, 44, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, P.V.; Kamthan, M.; Gera, R.; Dogra, S.; Gautam, K.; Ghosh, D.; Mondal, P. Chronic exposure to Pb2+ perturbs Ch REBP transactivation and coerces hepatic dyslipidemia. FEBS Lett. 2019, 593, 3084–3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Huo, Y.; Gao, X.; Li, Y.; Cheng, F.; Zhang, Z. Lead exposure exacerbates liver injury in high-fat diet-fed mice by disrupting the gut microbiota and related metabolites. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 3060–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.J.; Lemberg, K.M.; Lamprecht, M.R.; Skouta, R.; Zaitsev, E.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Patel, D.N.; Bauer, A.J.; Cantley, A.M.; Yang, W.S.; et al. Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockwell, B.R.; Angeli, J.P.F.; Bayir, H.; Bush, A.I.; Conrad, M.; Dixon, S.J.; Fulda, S.; Gascon, S.; Hatzios, S.K.; Kagan, V.E.; et al. Ferroptosis: A regulated cell death nexus linking metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell 2017, 171, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yu, S.; Liu, W.; Zhuo, Y.; Qu, C.; Zeng, Y. Ferroptosis-related signaling pathways in cancer drug resistance. Cancer Drug Resist. 2025, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Lin, B.; Jin, W.; Tang, L.; Hu, S.; Cai, R. NRF2, a superstar of ferroptosis. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Wang, L.; Wu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Yao, Y.; Yang, H.; Hao, C. Lipid metabolism in ferroptosis: Mechanistic insights and therapeutic potential. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1545339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Long, D. Nrf2 and ferroptosis: A new research direction for neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.F.; Zou, T.; Tuo, Q.Z.; Xu, S.; Li, H.; Belaidi, A.A.; Lei, P. Ferroptosis: Mechanisms and links with diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Liao, Y.; Zhu, C.; Zou, Z. GPX4, ferroptosis, and diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 174, 116512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangid, A.P.; Shekhawat, V.P.S.; Pareek, H.; Yadav, D.; Sharma, P.; John, P.J. Effect of lead on human blood antioxidant enzymes and glutathione. Int. J. Biochem. Res. Rev. 2016, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shilpa, O.; Anupama, K.P.; Antony, A.; Gurushankara, H.P. Lead (Pb) induced oxidative stress as a mechanism to cause neurotoxicity in Drosophila melanogaster. Toxicology 2021, 462, 152959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, J.T.; Venkataramani, V.; Washburn, C.; Liu, Y.; Tummala, V.; Jiang, H.; Smith, A.; Cahill, C.M. A role for amyloid precursor protein translation to restore iron homeostasis and ameliorate lead (Pb) neurotoxicity. J. Neurochem. 2016, 138, 479–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Chen, Y.; Fan, G.; Feng, C.; Du, G.; Zhu, G.; Li, Y.; Jiao, H.; Guan, L.; Wang, Z. Lead-induced iron overload and attenuated effects of ferroportin 1 overexpression in PC12 cells. Toxicol. Vitro. 2014, 28, 1339–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Wang, Y.; Hao, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, F.; Ge, Y.; Liu, S.C.; Liu, P.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y. Lead binds HIF-1α contributing to depression-like behaviour through modulating mitochondria-associated astrocyte ferroptosis. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Q.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.; Ribas, L.; Liu, H.; Jiang, J. Dietary Cottonseed Protein Substituting Fish Meal Induces Hepatic Ferroptosis Through SIRT1-YAP-TRFC Axis in Micropterus salmoides: Implications for Inflammatory Regulation and Liver Health. Biology 2025, 14, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, K.; Zon, L.I. Zebrafish: A model system for the study of human disease. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2000, 10, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakan-Akdogan, G.; Aftab, A.M.; Cinar, M.C.; Abdelhalim, K.A.; Konu, O. Zebrafish as a model for drug induced liver injury: State of the art and beyond. Explor. Dig. Dis. 2023, 2, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Weng, Y.; Shi, W.; Liang, S.; Liao, X.; Chu, R.; Ai, Q.; Mai, K.; Wan, M. Aquatic high iron induces hepatic ferroptosis in zebrafish (Danio rerio) via interleukin-22 signaling pathway. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 367, 125627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Fan, Z.; Wu, J.; Li, L.; Cheng, G.; Yan, J.; Wang, Z.; Qian, Q.; Wang, H. Combined exposure of polystyrene nanoplastics and silver nanoparticles exacerbating hepatotoxicity in zebrafish mediated by ferroptosis pathway through increased silver accumulation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 492, 138260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Sun, W.; Song, Y.; Wu, S.; Xie, S.; Xiong, W.; Peng, C.; Peng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Lek, S.; et al. Acute waterborne cadmium exposure induces liver ferroptosis in Channa argus. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 283, 116947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Z.; Xie, B.; Tao, Y.; Xiao, D. Mechanism of Ferroptosis and Its Role in Disease Development. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2025, 21, 5328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhang, B.; Li, N.; Ji, X.; Liu, K.; Jin, M. Zebrafish neurobehavioral phenomics applied as the behavioral warning methods for fingerprinting endocrine disrupting effect by lead exposure at environmentally relevant level. Chemosphere 2019, 231, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, R.; Liu, C.; Chen, Y. Molecular mechanism of lead-induced superoxide dismutase inactivation in zebrafish livers. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2014, 118, 14820–14826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Fish Embryo Acute Toxicity (FET) Test; Section 2; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Guidance Document on Aqueous-Phase Aquatic Toxicity Testing of Difficult Test Chemicals. No. 23 (Second Edition); OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019; Available online: https://one.oecd.org/document/ENV/JM/MONO(2000)6/REV1/en/pdf (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Ahmed, A.I.M.; Macirella, R.; Talarico, F.; Curcio, V.; Trotta, G.; Aiello, D.; Gharbi, N.; Mezzasalma, M.; Brunelli, E. Short-term effects of the strobilurin fungicide dimoxystrobin on zebrafish gills: A morpho-functional study. Chemosphere 2023, 333, 138914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, J.; Katti, P.; Biete, M.; Mungai, M.; AshShareef, S.; Neikirk, K.; Lopez, E.G.; Vue, Z.; Christensen, T.A.; Beasley, H.K.; et al. A universal approach to analyzing transmission electron microscopy with ImageJ. Cells 2021, 10, 2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Zhao, W.; Zhong, Y.; Jiang, X.; Mei, H.; Chang, Y.; Wu, D.; Dou, J.; Vasquez, E.; Shi, X.; et al. Effects of chronic low-level lead (Pb) exposure on cognitive function and hippocampal neuronal ferroptosis: An integrative approach using bioinformatics analysis, machine learning, and experimental validation. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 917, 170317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Z.; Wei, Y.; He, M.; Lin, C.; Ouyang, W.; Liu, X. Antimony trioxide nanoparticles promote ferroptosis in developing zebrafish (Danio rerio) by disrupting iron homeostasis. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 949, 175140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Song, J.; Qian, Q.; Wang, H. Silver nanoparticles induce liver inflammation through ferroptosis in zebrafish. Chemosphere 2024, 362, 142673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Chen, H.; Lian, H.; Cai, X.; Xie, L.; Ahmed, R.G.; Lin, X.; Chen, H.; Dong, W. The role of the ferroptosis pathway in the toxic mechanism of TCDD-induced liver damage in zebrafish. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part-C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2025, 295, 110213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.H.; Song, C.C.; Pantopoulos, K.; Wei, X.L.; Zheng, H.; Luo, Z. Mitochondrial oxidative stress mediated Fe-induced ferroptosis via the NRF2-ARE pathway. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2022, 180, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Cao, J.; Feng, C.; Luo, Y.; Lin, Y. Self-recovery study of fluoride-induced ferroptosis in the liver of zebrafish (Danio rerio). Aquat. Toxicol. 2022, 251, 106275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Jia, Y.; Mahmut, D.; Deik, A.A.; Jeanfavre, S.; Clish, C.B.; Sankaran, V.G. Human hematopoietic stem cell vulnerability to ferroptosis. Cell 2023, 186, 732–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Ruan, S.; Sun, J.; Li, J.; Chen, D.; Ma, Y.; Gi, Y.; Liu, Z.; Ruan, Q.; Huang, Y. Human cytomegalovirus RNA2. 7 inhibits ferroptosis by upregulating ferritin and GSH via promoting ZNF395 degradation. PLoS Pathog. 2024, 20, e1012815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.J.; Patel, D.N.; Welsch, M.; Skouta, R.; Lee, E.D.; Hayano, M.; Thomas, A.G.; Gleason, C.E.; Tatonetti, N.P.; Slusher, B.S.; et al. Pharmacological inhibition of cystine–glutamate exchange induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis. eLife 2014, 3, e02523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y. Beyond single targets: Crosstalk between endoplasmic reticulum stress, ferroptosis, and vitamin D signaling in stroke treatment. Cell Signal. 2025, 3, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Shi, C.; He, M.; Xiong, S.; Xia, X. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: Molecular mechanism and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Liu, J.Y.; Dong, J.X.; Xiao, Q.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, F.L. Toxicity of Pb2+ on rat liver mitochondria induced by oxidative stress and mitochondrial permeability transition. Toxicol. Res. 2017, 6, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandaru, L.J.M.; Murumulla, L.; Lasya, C.B.; Prasad, D.K.; Challa, S. Exposure of combination of environmental pollutant, lead (Pb) and β-amyloid peptides causes mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in human neuronal cells. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2023, 55, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeeshan, H.M.A.; Lee, G.H.; Kim, H.R.; Chae, H.J. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and associated ROS. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.; Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Li, W. Crosstalk between endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis in liver diseases. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed) 2024, 29, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kielan, B.; Pałasz, A.; Krysta, K.; Krzystanek, M. Ferroptosis as a Form of Cell Death—Medical Importance and Pharmacological Implications. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Kang, R.; Tang, D. Identification of ACSL4 as a biomarker and contributor of ferroptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 478, 1338–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zheng, B.; Peng, X.; Ma, N.; Qi, Y.; Lan, X.; Wang, Y.; Zha, H.; Zhou, C.; Liu, F.; et al. Lead exposure induces ferroptosis in ALS cell models by activating the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 306, 119301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Yan, S.; Zhang, H.; Ruilin, D.; Cheng, X.; Bao, S.; Li, X.; Song, Y. Cadmium induced ferroptosis and inflammation in sheep via targeting ACSL4/NF-κB axis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1617190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concessao, P.L.; Prakash, J. Arsenic-induced nephrotoxicity: Mechanisms, biomarkers, and preventive strategies for global health. Vet. World. 2025, 18, 2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyotsana, N.; Ta, K.T.; DelGiorno, K.E. The role of cystine/glutamate antiporter SLC7A11/xCT in the pathophysiology of cancer. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 858462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Xing, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Jin, X.; Tian, M.; Ba, X.; Hao, F. Cysteine and homocysteine can be exploited by GPX4 in ferroptosis inhibition independent of GSH synthesis. Redox Biol. 2024, 69, 102999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, Y.; Song, X.; Long, D. Ferroptosis regulation through Nrf2 and implications for neurodegenerative diseases. Arch. Toxicol. 2024, 98, 579–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Zhao, K.; Sun, L.; Yin, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, C.; Li, B. SLC7A11 regulated by NRF2 modulates esophageal squamous cell carcinoma radiosensitivity by inhibiting ferroptosis. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, K.K.; Kamila, S.; Das, T.; Chattopadhyay, A. Lead induced genotoxicity and hepatotoxicity in zebrafish (Danio rerio) at environmentally relevant concentration: Nrf2-Keap1 regulated stress response and expression of biomarker genes. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2024, 107, 104396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrakowski, M.; Pawlas, N.; Hudziec, E.; Kozłowska, A.; Mikołajczyk, A.; Birkner, E.; Kasperczyk, S. Glutathione, glutathione-related enzymes, and oxidative stress in individuals with subacute occupational exposure to lead. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2016, 45, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coornaert, I.; Breynaert, A.; Hermans, N.; De Meyer, G.R.; Martinet, W. GPX4 overexpression does not alter atherosclerotic plaque development in ApoE knock-out mice. Vasc. Biol. 2024, 6, e230020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; Li, D.; Meng, H.; Sun, D.; Lan, X.; Ni, M.; Ma, J.; Zeng, F.; Sun, S.; Fu, J.; et al. Targeting a novel inducible GPX4 alternative isoform to alleviate ferroptosis and treat metabolic-associated fatty liver disease. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 3650–3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.J.; Kabeer, A.; Abbas, Z.; Siddiqui, H.A.; Calina, D.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Cho, W.C. Interplay of oxidative stress, cellular communication and signaling pathways in cancer. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aglan, H.S.; Gebremedhn, S.; Salilew-Wondim, D.; Neuhof, C.; Tholen, E.; Holker, M.; Schellander, K.; Tesfaye, D. Regulation of Nrf2 and NF-κB during lead toxicity in bovine granulosa cells. Cell Tissue Res. 2020, 380, 643–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, H.; Tan, X.; Yang, D.; Lv, Z.; Jiang, H.; Lu, J.; Baiyun, R.; Zhang, Z. GSPE reduces lead-induced oxidative stress by activating the Nrf2 pathway and suppressing miR153 and GSK-3β in rat kidney. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 42226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.