Abstract

Identifying floating residual feed is a critical technology in recirculating aquaculture systems, aiding water-quality control and the development of intelligent feeding models. However, existing research is largely based on ideal indoor environments and lacks adaptability to complex outdoor scenarios. Moreover, current methods for this task often suffer from high computational costs, poor real-time performance, and limited recognition accuracy. To address these issues, this study first validates in outdoor aquaculture tanks that instance segmentation is more suitable than individual detection for handling clustered and adhesive feed residues. We therefore propose LMFF–YOLO, a lightweight multi-scale fusion feed segmentation model based on YOLOv8n-seg. This model achieves the first collaborative optimization of lightweight architecture and segmentation accuracy specifically tailored for outdoor residual feed segmentation tasks. To enhance recognition capability, we construct a network using a Context-Fusion Diffusion Pyramid Network (CFDPN) and a novel Multi-scale Feature Fusion Module (MFFM) to improve multi-scale and contextual feature capture, supplemented by an efficient local attention mechanism at the backbone’s end for refined local feature extraction. To reduce computational costs and improve real-time performance, the original C2f module is replaced with a C2f-Reparameterization vision block, and a shared-convolution local-focus lightweight segmentation head is designed. Experimental results show that LMFF–YOLO achieves an mAP50 of 87.1% (2.6% higher than YOLOv8n-seg), enabling more precise estimation of residual feed quantity. Coupled with a 19.1% and 20.0% reduction in parameters and FLOPs, this model provides a practical solution for real-time monitoring, supporting feed waste reduction and intelligent feeding strategies.

Keywords:

LMFF–YOLO; recirculating aquaculture; floating residual feed; deep learning; outdoor aquaculture tanks Key Contribution:

This study introduces LMFF–YOLO, a segmentation model that strikes an optimal balance between accuracy and efficiency for outdoor residual feed segmentation. Through novel architectural designs, it significantly improves multi-scale feature fusion and contextual modeling, achieving superior mAP50 alongside a substantial reduction in computational cost, thereby setting a new practical benchmark for the task.

1. Introduction

Recirculating aquaculture represents an efficient production model amenable to automation and intelligent control, and its market share has steadily increased in recent years [1]. Within these systems, feed administration is the most critical operational aspect, directly impacting both the cultivation yield of farmed species and the economic sustainability of the operation [2]. Current feeding strategies predominantly rely on manual application or automated machines that dispense fixed quantities at fixed times. Consequently, feeding amounts are often determined by the subjective experience of farmers. However, this approach carries significant risks: insufficient feeding can impair the development of farmed animals, whereas excessive feeding results in residual feed that pollutes the water [3,4]. Information from residual feed estimation serves as a crucial input parameter for constructing precise feeding systems. Real-time detection of residual feed allows for an accurate assessment of the animals’ feeding requirements, thereby enabling precise feed administration [5,6].

Previous research has explored acoustic technology for residual feed detection [7,8,9]. While this method is relatively simple to implement, it is susceptible to noise interference and costly, which have hindered its widespread application in aquaculture. Other researchers have investigated residual feed identification using machine vision techniques. For example, Atoum et al. [10] detected residual feed particles in local areas using correlation filters and subsequently suppressed detection errors with an optimized support vector machine classifier. Hung et al. [11] developed a highly sensitive underwater vision platform to observe residual feed on sediments in turbid, low-light pond environments. Li et al. [12] employed an adaptive thresholding framework for subaquatic imagery, which used a maximum likelihood-guided Gaussian mixture model to derive adaptive thresholds suitable for varying illuminance and turbidity gradients. Despite achieving reasonable results, these traditional machine vision methods often rely heavily on human intervention and deliver suboptimal real-time detection performance.

In recent years, deep learning has emerged as a promising alternative for solving complex detection problems [13,14,15]. Deep-learning models automatically extract salient features via neural networks, eliminating reliance on manually engineered features and thereby significantly improving both detection accuracy and real-time performance. This approach has been successfully applied to residual feed detection. Hou et al. [16] proposes an improved MCNN network model to quantitatively study the bait particle. The experimental results show that the mean absolute error (MAE) of the proposed model is 2.32, and the mean square error (MSE) is 3.00. Although its recognition accuracy has been improved, it still consumes substantial computational resources, rendering it unsuitable for deployment on edge devices. Xu et al. [17] proposed the YOLOv5s-CAGSDL model based on YOLOv5s. Compared to the YOLOv5s model, the YOLOv5s-CAGSDL model achieved improvements of 6.30% and 10.80% in AP50 and FPS, respectively, bringing potential environmental and economic benefits in the actual aquaculture environment. Feng et al. [18] proposed a lightweight network, YOLO-feed, based on YOLOv8s. This network enables real-time, high-precision feed pellet detection on CPU devices. However, in outdoor recirculating aquaculture tanks, vision-based perception of residual feed faces core challenges. First, the continuous variation in natural light causes areas of intense reflection and shadow on the water surface to shift constantly, creating high-contrast conditions that severely disrupt the stable extraction of image features. More critically, in outdoor scenarios, the aggregation of residual feed consistently co-occurs with the aforementioned dynamic lighting conditions. Under rapidly changing light and shadow, the contours and contrast of these blurred, clustered targets become further distorted. This fundamentally undermines the suitability of traditional detection paradigms, which are designed to identify clear, distinct individual objects. Furthermore, during dataset construction, the insufficient clarity of images captured under such complex conditions hinders effective annotation, thereby further increasing the complexity of model training.

Therefore, exploring holistic analysis methods capable of directly processing aggregated residual feed—specifically, bypassing individual differentiation and performing segmentation directly on cohesive regions—emerges as a potential technical pathway to address these challenges. This necessitates that subsequent research not only focus on model lightweighting and accuracy enhancement but also fundamentally design recognition frameworks tailored for dense, cohesive targets. Methods based on deep neural networks, which automatically learn local and global image features to achieve target region segmentation, have seen important applications in fields such as agriculture, medicine, and intelligent driving [19,20,21]. Several studies have applied deep-learning segmentation to related problems. Hu et al. [22] employed a dual strategy using you only look once version 3 (YOLOv3) and mask region-based convolutional neural network (Mask R-CNN) to identify residual feed; YOLOv3 was used for instance segmentation of crabs and feed in cluttered scenes, whereas Mask-RCNN was applied to segment feed in crab-free environments. While this body of research demonstrates that deep-learning-based instance segmentation can effectively detect and segment objects, challenges of high computational load and poor real-time performance persist. For residual feed recognition specifically, a model must achieve both high accuracy and real-time processing—a combination that remains an urgent, unresolved issue.

In summary, to address the need for real-time monitoring of residual feed in outdoor aquaculture tanks, this study proposes LMFF–YOLO, a lightweight model derived from YOLOv8n-seg. It is designed primarily for real-time, on-site segmentation, providing accurate pixel-level contours of adhesive feed patches. This high-precision output enables the quantitative estimation of residual feed area and distribution, which serves as a critical data layer for assessing feeding efficiency and guiding management decisions. By forming a reliable perception module for vision-based precision feeding systems. Ultimately, this work aims to contribute directly to feed waste reduction and water quality management through improved sensing accuracy.

- (1)

- It presents a comprehensive comparison of residual feed individual detection and instance segmentation in outdoor recirculating aquaculture tanks, using experimental data and visual analysis to evaluate their recognition performance.

- (2)

- It proposes LMFF–YOLO, an improved lightweight model based on YOLOv8n-seg, which is designed to achieve real-time segmentation and facilitate deployment on resource-constrained devices by balancing operational efficiency with high segmentation accuracy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Setup and Evaluation

2.1.1. Data Collection and Processing

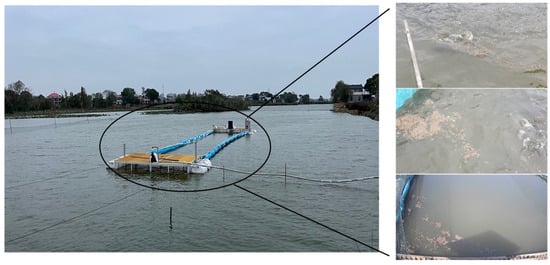

As no publicly available dataset on fish residual feed is available, this study used a self-built dataset. Image data were collected from the aquaculture demonstration base of Kaitian Fish Farm in Qiaokou Town, Changsha City, Hunan Province, China. Data sources comprise two components: first, surveillance cameras fixed at specific positions and angles, providing baseline images with stable perspectives and scales; second, images captured by mobile phones from varying distances and angles to encompass perspective and scale variations that may occur in real-world scenarios, thereby enhancing the model’s adaptability to such changes. A total of 1500 raw images were collected, each with a resolution of 2880 × 1620 pixels. Mobile phone photography was conducted by designated personnel, with shooting distances controlled within a specific range to minimize extreme perspective variations. The collection site and examples of the residual feed images are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Data collection site at Kaitian Fish Farm, showing the outdoor recirculating aquaculture tank (left) and inset examples of residual feed images captured in varying conditions (right).

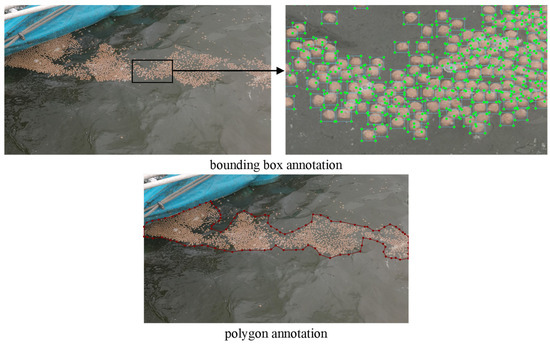

To accommodate the distinct annotation needs of each task, LabelImg 1.86(for bounding box annotations) and LabelMe 5.6.1(for polygon annotations) were used during data preparation. The specific annotation examples are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Examples of the data-annotation methodologies. (Top-left) Original image. (Top-right) Annotation for individual detection, showing bounding boxes around each particle. (Bottom) Annotation for instance segmentation, showing a polygon mask enclosing the aggregated feed cluster.

For core instance segmentation annotations, we have established clear annotation guidelines and strictly enforced them to ensure repeatability and consistency. First, each visually distinguishable clump of residual feed is annotated as an independent instance, with its outline traced along visible actual edges. Second, for contiguous regions, the principle of “visually distinguishable” applies: if clear water gaps separate clumps, they are annotated as distinct instances; if fully merged with indistinguishable boundaries, they are annotated as a single instance. We avoided fixed pixel distance or area thresholds to prevent inconsistent annotations under varying lighting and perspective conditions. Finally, all annotations undergo a rigorous quality control process. This involves initial labeling by one researcher, followed by 100% cross-verification by a second researcher. Discrepancies are discussed between both parties and ultimately arbitrated by a senior researcher to ensure consistent annotation standards.

To enhance model robustness, this study applied a combination of image-augmentation techniques to both the original images and their corresponding labels. These techniques included image scaling, color enhancement, blur enhancement, noise enhancement, and image flipping. Through this data-augmentation process, the dataset was expanded from 1500 to 4000 images. The preprocessed dataset was then divided into training (70%), validation (20%), and test (10%) sets.

2.1.2. Experimental Environment

The experimental platform employed was a Windows 10 operating system equipped with a 12th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-12400F 2.50 GHz processor and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060Ti 8 GB graphics card. The models were developed using Python 3.11 and the deep-learning framework version 2.0.0, with CUDA version 11.8. Key training hyperparameters were set as follows: a batch size of 32 was used, with mosaic data augmentation enabled for the majority of training but disabled for the final 10 epochs. The initial learning rate was 0.01, and the minimum learning rate was 0.0001. The stochastic gradient descent optimizer was employed with a momentum parameter of 0.937. All models were trained for 500 epochs, and no pretrained weights were loaded for any experiment to ensure a fair comparison.

2.1.3. Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the residual feed segmentation models, we selected precision (P), recall (R), and mean average precision (mAP) as primary evaluation indicators. mAP50 represents the average detection accuracy at an intersection over union (IoU) threshold of 0.5 for all categories, whereas mAP50-95 represents the average detection accuracy across all IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95, with a step size of 5. mAP is calculated as follows:

In these formulas, TP (True Positive) is the correctly predicted positive instance, FP (False Positive) is the incorrectly predicted positive instance, and FN (False Negative) is the incorrectly predicted negative instance. AP represents the detection accuracy for a single category, mAP is the average of all category APs, and N is the total number of categories. Additionally, this study employed parameters (Params), floating-point operations (FLOPs), and frames per second (FPS) to evaluate the model’s size and computational efficiency. Params refers to the total sum of trainable parameters within the network, and FLOPs refers to the total number of floating-point operations performed during model inference, which is used to estimate the required computing resources.

2.2. Selection of Methods for Identifying Floating Fish Residual Feed

To effectively evaluate performance in outdoor recirculating aquaculture tanks, this study systematically compared three identification methods: individual detection, sliding slice detection, and instance segmentation. Given the minute size of residual feed particles and the high resolution (2880 × 1620 pixels) of images captured in real-world scenarios, conventional detection methods often overlook small targets when applied directly. To address this, we employed a sliding-slice detection strategy based on the slicing-aided hyper-inference algorithm developed by the Ultralytics team. This approach significantly enhances the detection of small objects by slicing high-resolution images into multiple overlapping smaller patches, performing detection on each patch individually, and then fusing the results. The sliding slice detection in this study used YOLOv8n as the base detection architecture. Its training set comprised manually cropped slices from the original high-resolution images, resized to 640 × 640 pixels, ensuring consistency between the slice data and the detection scale. The individual detection task was similarly implemented using the YOLOv8n model, whereas instance segmentation employed the YOLOv8n-seg model. To ensure a fair comparison, all models were trained, validated, and tested on the same image dataset, which maintained its original 2880 × 1620-pixel resolution. During training and inference, all models automatically performed resize-and-pad preprocessing on input images, uniformly resizing them to 640 × 640 pixels to meet network input requirements.

Experiments were conducted on the test set to compare the detection performance of the three methods. The results are presented in Table 1. Note that object and sliding slice detection employ box-based evaluation metrics, whereas instance segmentation uses mask-based evaluation metrics. The experimental results indicate that the individual detection method exhibits poor recognition performance with low recall, suggesting that the model missed a significant number of detections. Although sliding slice detection achieved the highest recognition accuracy, its FPS was excessively low to meet real-time detection requirements. By contrast, the instance segmentation method achieved a favorable balance between recognition accuracy and processing efficiency, making it more suitable for the real-time detection of outdoor recirculating aquaculture tanks.

Table 1.

Performance comparison of the three preliminary identification methods.

To fairly evaluate the performance difference between instance segmentation and object detection for residual bait under a unified metric, this study introduces an area comparison method independent of annotation formats. To circumvent the inherent differences in standard evaluation protocols (e.g., Average Precision) between bounding boxes and segmentation masks, the analysis focuses on the core capability of both approaches in predicting the true pixel area of targets. To ensure evaluation accuracy, a subset of 50 images captured as parallel as possible to the water surface was selected from the dataset. For this subset, the standard pixel area of residual bait in each image was obtained through meticulous manual scribble annotations on the original targets. Based on this benchmark, the pixel area of the segmentation mask output by the instance segmentation model and the pixel area of the bounding box output by the object detection model were calculated and compared against the standard area from the scribble annotations. The core evaluation metric is the Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) of the predicted area relative to the standard scribble area, calculated as follows:

In these formulas, APE is the Absolute Percentage Error for a Single Sample, Apred is the model-predicted area (mask or bounding box), Agt is the standard area from manual scribbles. MAPE, the Mean Absolute Percentage Error, provides an aggregate measure of accuracy across the test set. N is the number of test samples (N = 50 in this case). The term σ stands for the standard deviation of the errors, quantifying their dispersion around the mean (MAPE) and serving as a metric for assessing the stability and consistency of the predictive method.

Based on the quantitative evaluation and statistical test results presented in Table 2, the instance segmentation demonstrates a significant advantage in the accuracy of residual feed area prediction, with its MAPE being 17.17% and 41.56% lower than that of the sliding slice detection and the object detection, respectively. This performance superiority is rigorously confirmed by paired-sample t-tests: the difference between instance segmentation and object detection is highly significant (t(49) = 8.69, p < 0.001), and the difference compared to sliding slice detection is also significant (t(49) = 2.98, p = 0.041). It is noteworthy that although object detection exhibits the highest prediction consistency, its substantial systematic error (MAPE = 58.52%) primarily stems from a high rate of missed detections, leading to a systematic underestimation of the total residual feed area. The sliding slice detection partially mitigates this issue through slice analysis, which improves recall, yet its accuracy remains significantly lower than that of instance segmentation. Therefore, from the statistical comparison based on a unified area error metric, this study concludes that for aquaculture applications requiring precise quantification of residual feed coverage area, instance segmentation is the pivotal technology for providing reliable spatial quantification information.

Table 2.

Residual feed area prediction of the three preliminary identification methods.

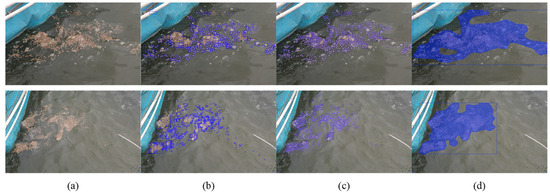

To visually compare the performance of the different methods, images were randomly selected from the test set (Figure 3). Evidently, residual feed particles are minuscule, constituting a typical small-object detection problem. When particles are aggregated, blurred boundaries and low feature distinctiveness between objects reduce individual recognition accuracy. While the sliding slice detection method demonstrated satisfactory detection performance overall, it exhibited a limited capability to distinguish adhered residual feed particles. Although the segmentation method occasionally missed scattered residual feed instances, it effectively partitioned most residual feed targets, rendering it more suitable for the practical requirements of residual feed identification in outdoor recirculating aquaculture tanks. However, the baseline YOLOv8n-seg model presents challenges, including substantial parameter size and computational demands, alongside room for improvement in segmentation accuracy. Therefore, further optimization and refinement were necessary.

Figure 3.

Visual comparison of the effects of preliminary identification methods. (a) Original image; (b) individual object detection (YOLOv8n), showing significant missed detections; (c) sliding slice detection, showing improved recall; and (d) instance segmentation (YOLOv8n-seg), which effectively groups aggregated feed.

2.3. LMFF–YOLO: Improved YOLOv8n-Seg Model

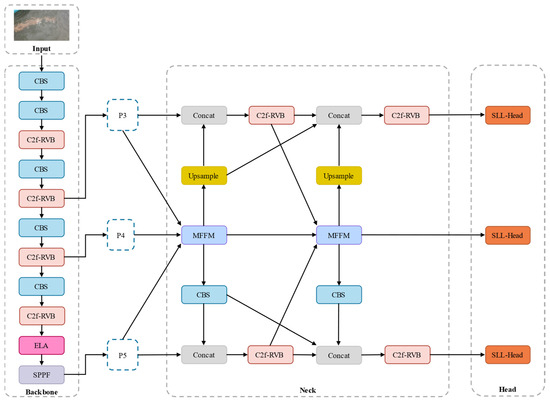

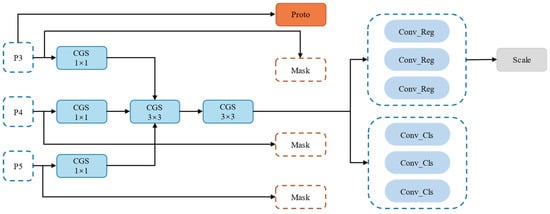

LMFF–YOLO is an efficient residual feed segmentation model based on YOLOv8n-seg, designed to balance operational efficiency with segmentation accuracy. The feature-fusion component incorporates the context-fusion diffusion pyramid network (CFDPN) and a novel multiscale feature-fusion module (MFFM) to form the MFFM–CFDPN. The RepVITBlock (RVB) module is adopted into the traditional C2f module, replacing it with the C2f-RVB module to optimize feature transfer efficiency. Efficient local attention (ELA) is applied at the end of the backbone to enhance feature discrimination. Finally, the shared convolution local focus lightweight segmentation head (SLL-Head) is designed to effectively reduce the model’s parameter count and operational cost while improving segmentation accuracy. The complete LMFF–YOLO architecture is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Overall network architecture of the proposed LMFF–YOLO model.

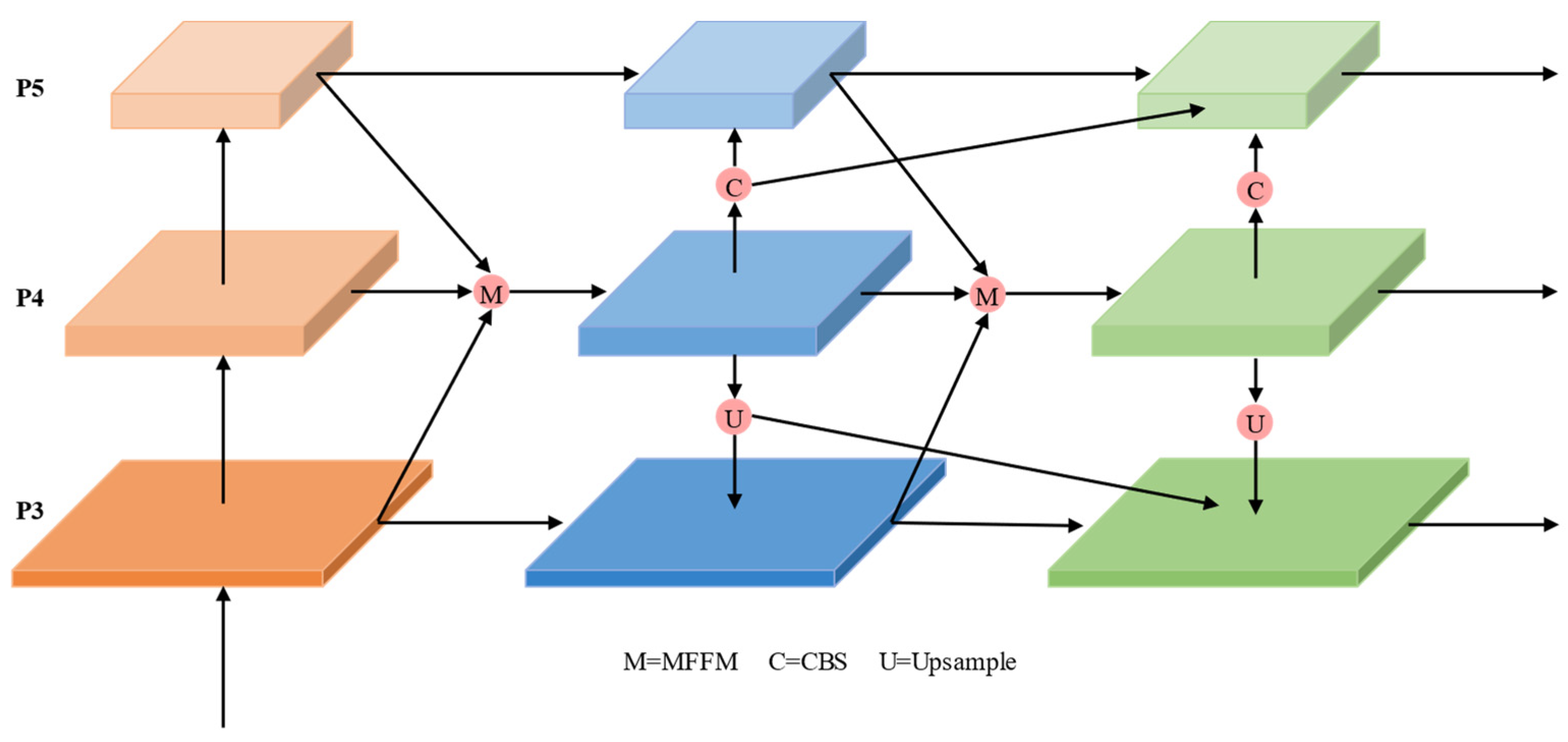

2.3.1. MFFM–CFDPN

In the YOLO series, the path aggregation feature pyramid network (PAFPN) is typically used for feature fusion. While effective at integrating features from higher to lower layers, it tends to overlook feature adjustments within the same layer. This leads to insufficient semantic information exchange across channels, making it difficult to effectively filter conflicting information, particularly when handling small objects and complex backgrounds. Additionally, PAFPN performs poorly when fusing non-adjacent layers, resulting in severe detail loss after multiple upsampling operations. To address these issues, this study adopts the CFDPN [23] and designs the MFFM for feature fusion across different layers, thereby constructing the MFFM–CFDPN.

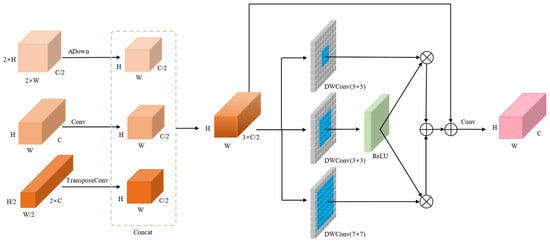

Standard multiscale feature fusion in YOLOv8 employs direct alignment followed by tensor concatenation. This approach fails to capture contextual information effectively, leading to significant feature-information loss during downsampling and alignment. To address this, we propose the MFFM, which uses parallel deep-wise separable convolution (DWConv) to simultaneously capture local contextual information at different scales. It constructs a feature-interaction gating mechanism through element-wise multiplication and addition, dynamically adjusting the weights of each branch to enhance feature interactions. Because the inherent information compression of convolution downsampling can easily lead to feature loss, this study incorporates ADown [24] into MFFM to handle high-resolution feature maps. The ADown module employs a dual-branch processing approach to preserve spatial details while extracting global semantics. It combines multiscale pooling to reduce information loss from downsampling, thereby improving small-object segmentation accuracy. The MFFM architecture is illustrated in Figure 5. The module receives three feature maps of different scales from layers P3, P4, and P5, denoted as high-resolution x1, medium-resolution x2, and low-resolution x3, respectively. x1 maintains its channel count through the lightweight ADown module, x2 aligns its channel count with that of x1 via standard convolution, and x3 is aligned with x1 through a transposed convolution and BatchNorm layer. The aligned feature maps are then concatenated to yield x′. Subsequently, a set of depth-separable convolutions is applied to obtain x1′, x2′, and x3′. x1′ is activated by the rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation function, multiplied element-wise with x2′ and x3′, and then summed to obtain x″. This result is connected to x1′ via a residual connection and convolved to align the channel counts with the P4 layer, yielding the final output xout. The MFFM operation is formulated as follows:

Figure 5.

Architecture of the multiscale feature-fusion module (MFFM).

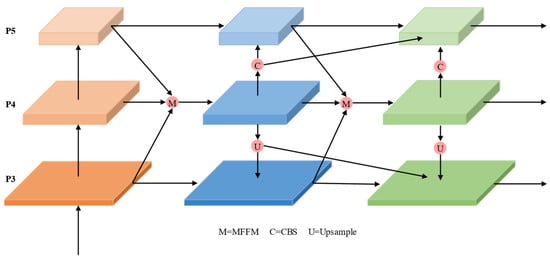

The unidirectional, localized feature-fusion method of the PAFPN results in insufficient interaction between information at different scales, thereby affecting model accuracy. MFFM–CFDPN extracts features from different network layers, fully considering their diversity in spatial resolution and semantic information. The network aggregates deep and shallow features into intermediate layers for multiscale feature fusion via the MFFM, avoiding the detail loss caused by multiple upsampling operations. Subsequently, the fused features are propagated to other layers through bidirectional diffusion. This mechanism not only enables the efficient flow of features across different scales but also enhances the model’s consistency in multiscale segmentation. The architecture MFFM–CFDPN is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Architecture of the MFFM–CFDPN.

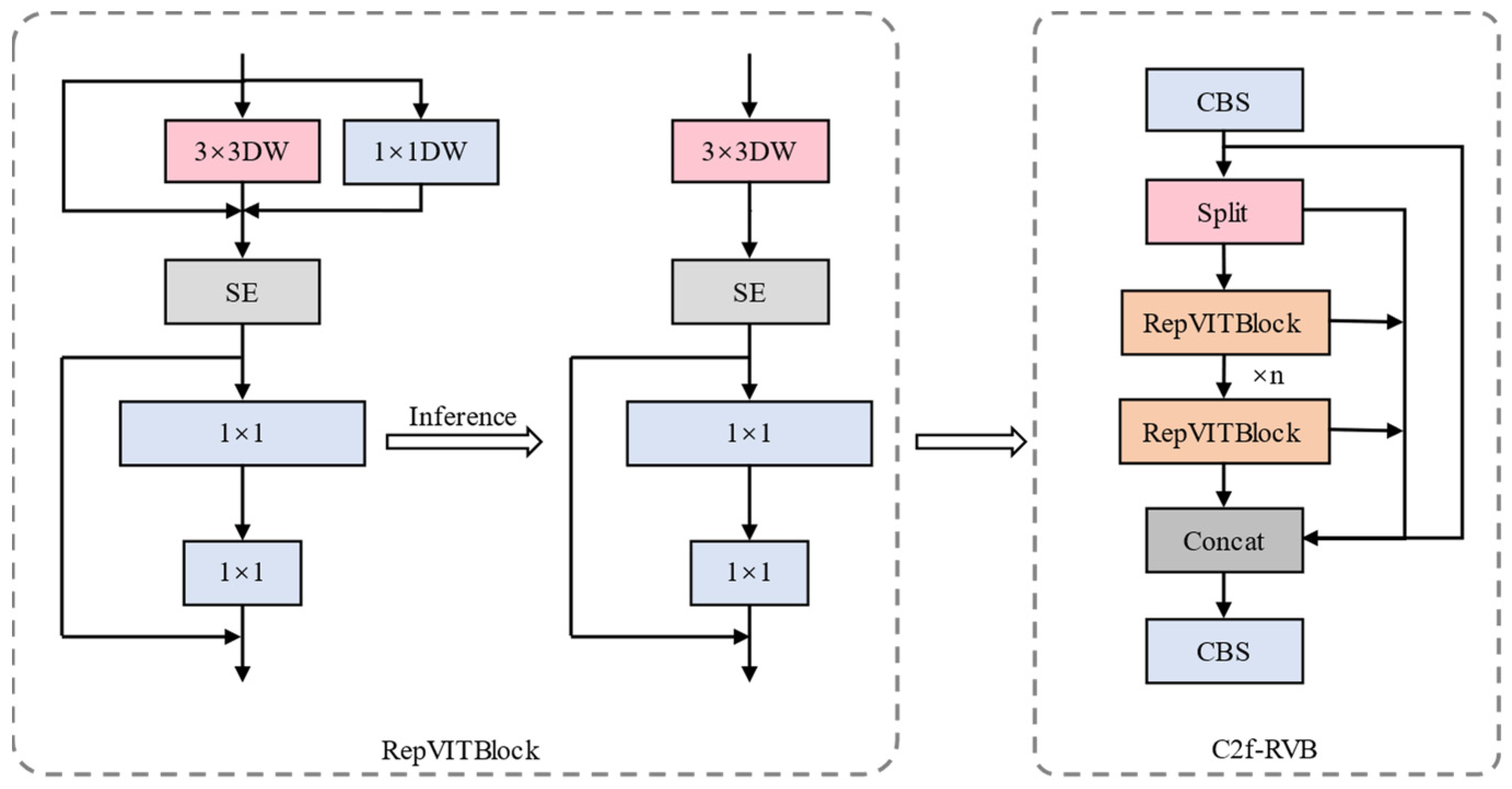

2.3.2. C2f-RVB

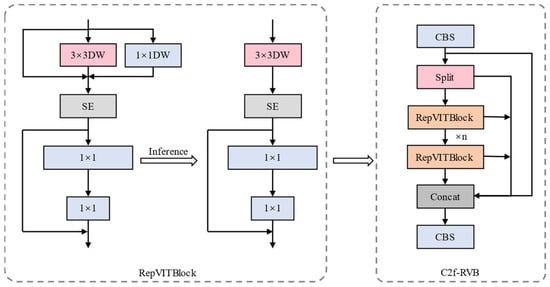

YOLOv8’s C2f module uses multiple standard convolutions and bottleneck blocks connected via residual connections to capture features of varying sizes. This structure incurs additional parameters and computational overhead, increasing the computational demand. To simplify the network structure and minimize redundant computations, this study adopts the RVB module [25], which employs a flexible parameter-representation method and decomposition techniques to convert large matrices into the product of smaller matrices. It separates the word and channel shufflers through reparameterization techniques, improving computational efficiency while compressing the parameter count. To develop a lightweight model, we replaced the bottleneck block within C2f with RVB to construct the C2f-RVB module. This model achieves lightweighting while ensuring accurate residual feed segmentation, thereby preserving the task’s real-time nature. The architecture of C2f-RVB is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Architecture of the proposed C2f-RVB module.

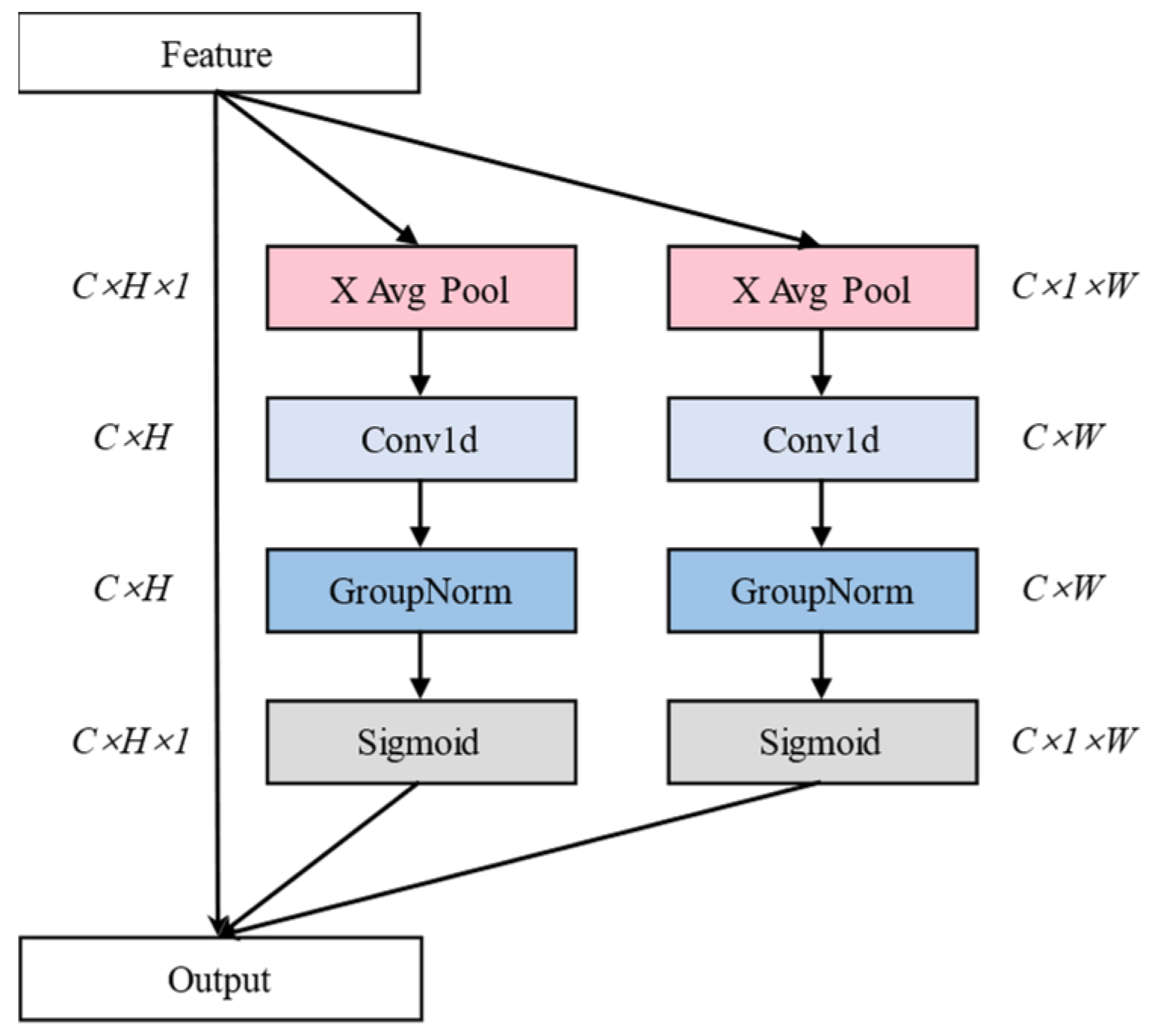

2.3.3. ELA

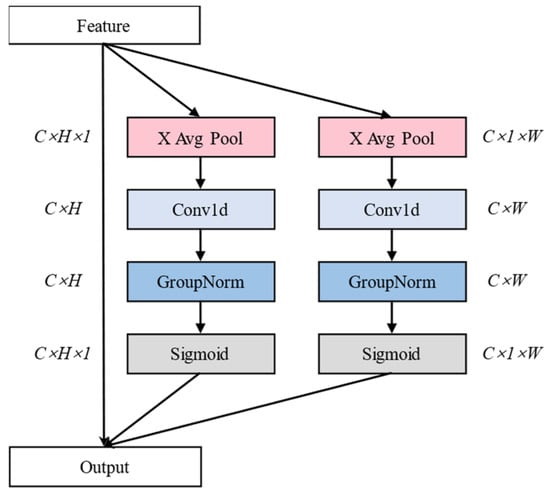

ELA [26] is a lightweight attention module that aims to enhance the model’s sensitivity to detailed information by enhancing its ability to extract local features while incurring low operational costs. It achieves this balance through local window computation and a lightweight design. Specifically, it captures long-range dependencies in both the horizontal and vertical directions through strip pooling, effectively addressing segmentation discontinuities caused by size differences in residual feed targets. Simultaneously, ELA’s dimension-free design retains the original channel information, and the generated positional attention map can accurately enhance the weight of the residual feed area. This allows ELA to meet the equipment restrictions of outdoor conditions while balancing performance. The ELA architecture is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Architecture of the efficient local attention (ELA) module.

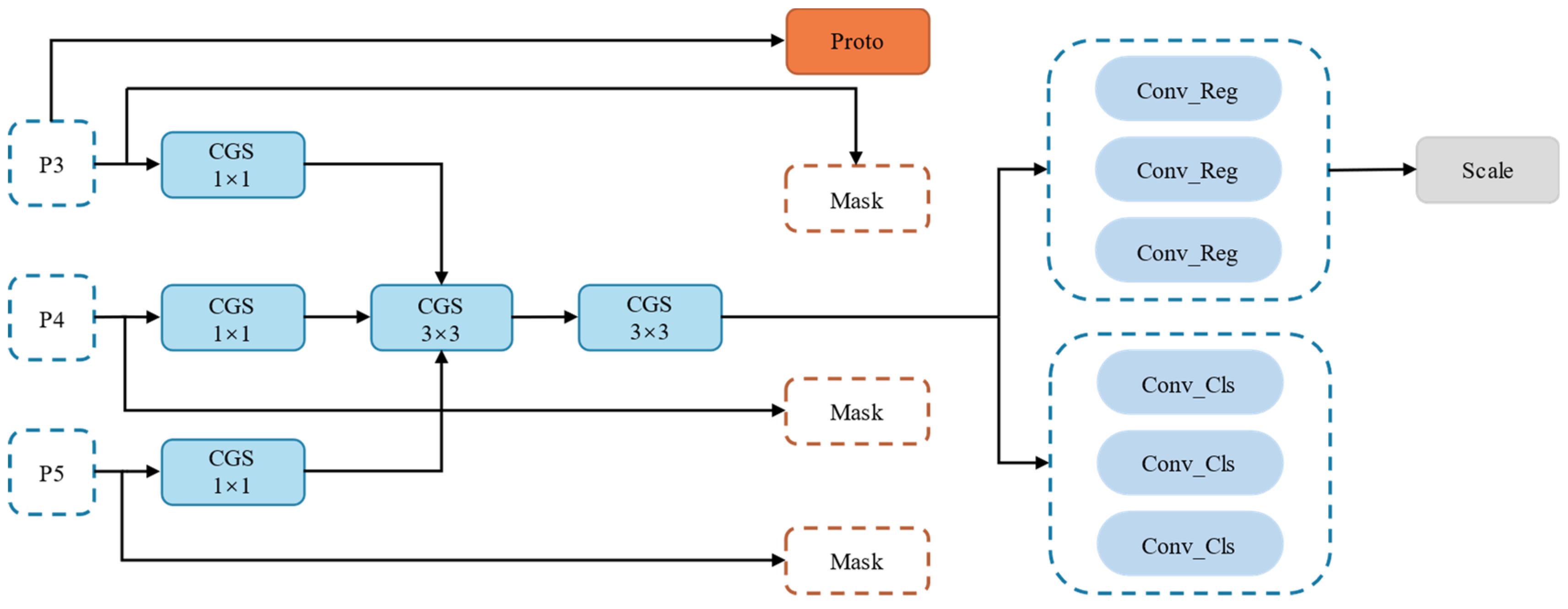

2.3.4. SLL-Head

The segmentation head of YOLOv8-seg comprises a detect branch, which predicts bounding boxes and classes, and a mask branch, which generates mask coefficients and prototypes. In the original model, each of the three output heads of the detect branch uses four 3 × 3 convolutions and two 1 × 1 convolutions, significantly increasing the network parameters and negatively impacting inference efficiency. To reduce the number of parameters and computational complexity, this study adopts shared convolutions in the detection branch and proposes the SLL-Head, which aggregates inputs from three feature layers into a shared convolutional layer for feature extraction. To address objects of different scales, the regression branch uses scale layers for feature scaling. Additionally, the original batch normalization (BatchNorm) in the convolution module is replaced with group normalization (GroupNorm) to construct the Conv-GroupNorm-SiLU (CGS) module. This grouping strategy reduces computational complexity while preserving channel correlations within a group, thereby preventing excessive feature smoothing. The improved detect branch structure is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Proposed shared convolution local focus lightweight segmentation head (SLL-Head) structure.

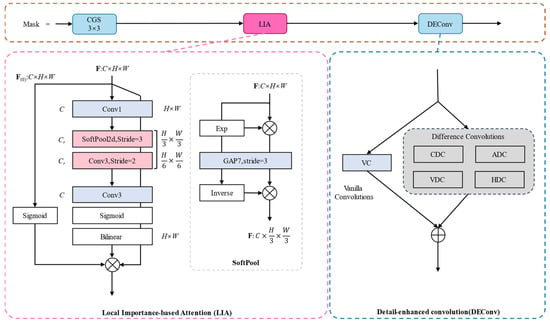

In the mask branch, CGS is first used for feature extraction; then, detail-enhancing convolution (DEConv) [27] is applied. DEConv contains parallel computation paths with four differential convolution branches and one standard convolution (VC) branch. The standard convolution preserves intensity-level information, whereas the differential convolutions amplify gradient-level information. Specifically, DEConv incorporates traditional local descriptors via four differential convolutions—center, angular, horizontal, and vertical—within the convolutional layers, optimizing computational overhead. Furthermore, the local importance-based attention (LIA) [28] mechanism is adopted to maintain the lightweight nature of the mask branch. LIA can measure local importance on low-resolution feature maps, enhancing the model’s ability to capture local information. The structure of the mask branch is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Structure of the lightweight mask branch.

In the context of the residual feed segmentation task, the shared convolution detection head enhances the model’s perception of residual feed areas of different sizes and shapes while maintaining computational efficiency. Simultaneously, the mask branch helps the model achieve more refined feature extraction, strengthening the representation of local image features and reducing small-target misses caused by information loss. SLL-Head improves the ability to obtain edge detail information during segmentation, enabling the model to better handle blurred boundaries and providing more accurate information for residual feed segmentation.

3. Experiments and Analysis

3.1. Ablation Experiment

To verify the specific effect of each modification in the LMFF–YOLO model, a series of ablation experiments was conducted on the test set. The results are presented in Table 3. First, replacing the original model’s neck with our proposed MFFM–CFDPN resulted in improvements of 1.9% and 2.5% in mAP50 and mAP50-95, respectively. This indicates that MFFM–CFDPN effectively enhances cross-scale information interaction within the network, enabling the model to fully utilize global context and capture multiple patterns from input features, thereby significantly improving its feature-representation capability. Second, replacing the C2f module with C2f-RVB streamlined the feature extraction network, reducing the model’s Params and FLOPs by 7.1 M and 1.7 G, respectively. Although this modification led to slight decreases in mAP50 (0.3%) and mAP50-95 (0.5%), it demonstrates that C2f-RVB can significantly improve the model’s runtime efficiency while sacrificing only a minimal amount of segmentation accuracy. Third, adopting the ELA mechanism into the backbone network improved the model’s mAP50 and mAP50-95 by 0.9% each. This demonstrates that ELA enhances the model’s sensitivity to detailed information by strengthening its ability to capture local features. Finally, using the SLL-Head as the segmentation head improved mAP50 and mAP50-95 by 0.5 and 1.4%, respectively, while decreasing Params and FLOPs by 5.6 M and 1.7 G, respectively.

Table 3.

Ablation study results for the components of LMFF–YOLO. The baseline model (1) is YOLOv8n-seg. Model (8) is the final LMFF–YOLO.

Overall, these improvements not only significantly enhance the model’s accuracy in residual feed segmentation but also effectively reduce its training and operational costs. This optimization makes real-time segmentation of residual feed feasible and facilitates easier deployment on resource-constrained devices.

3.2. Comparison of Different Attention Mechanisms

To validate the impact and choice of the ELA module, we conducted comparative experiments by integrating different attention mechanisms into the backbone of the original YOLOv8n-seg model, The mechanisms tested included the efficient multiscale attention (EMA), squeeze-and-excitation (SE), convolutional block attention module (CBAM), mixed local channel attention (MLCA), and context anchor attention (CAA). As shown in Table 4, compared to the original model, the CBAM, CAA, and ELA modules all demonstrated performance improvements; however, adopting the ELA mechanism yielded the most significant improvement.

Table 4.

Performance comparison of different attention mechanisms integrated into the YOLOv8n-seg backbone.

3.3. Comparison of Different Network Structures

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed MFFM–CFDPN, we compared its performance against that of other mainstream feature-fusion networks. As shown in Table 5, the MFFM–CFDPN significantly improved segmentation accuracy. By contrast, the performance of different models decreased, except for the model using BiFPN, which achieved 0.6 and 0.9% improvements in mAP50 and mAP50-95, respectively.

Table 5.

Performance comparison of different network structures.

3.4. Comparison of Different Segmentation Heads

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed segmentation head, we added different segmentation heads to the original network and conducted comparative experiments. The experimental results are shown in Table 6. The model with the added DyHead achieved the greatest improvement in segmentation accuracy, with mAP50 and mAP50-95 increasing by 1.9% and 1.4%, respectively; however, the number of parameters and computational cost increased by 33.3 M and 6.2 G, respectively. The remaining models performed worse than the original model. Meanwhile, the model incorporating the SLL-Head designed in this paper saw improvements of 0.5% and 1.4% in mAP50 and mAP50-95, respectively, while reducing the number of parameters and computational complexity by 5.6 M and 1.7 G, respectively, achieving a balance between segmentation accuracy and computational efficiency.

Table 6.

Performance comparison of different lightweight segmentation heads.

3.5. Comparison of Different Models

To comprehensively evaluate the model’s overall detection performance, LMFF–YOLO was benchmarked against several mainstream instance segmentation models, including YOLCAT, YOLOv5n-seg, YOLOv8n-seg, YOLOv11n-seg, Mask-RCNN, and Mask2Former. As shown in Table 7, LMFF–YOLO outperformed all competing models on both mAP50 and mAP50-95 metrics, except Mask2Former. However, in terms of computational efficiency, LMFF–YOLO features a parameter count of merely 26.3 M and computational load of 9.6 GFLOPs, while maintaining a frame rate of 317.14 FPS. This demonstrates commendable real-time processing capabilities. Compared with other models, LMFF–YOLO offers significant weight savings. It not only enables real-time, high-precision segmentation of residual feed but also facilitates deployment onto edge devices with limited computational resources. To validate the statistical significance of performance differences between the models, paired-sample t-tests were conducted on the test set, comparing LMFF–YOLO against both YOLOv8n-seg and YOLOv11n-seg. For each pairwise comparison, the analysis was restricted to test images for which both models yielded valid AP50 values, leading to slightly different effective sample sizes across comparisons. The results demonstrated statistically significant differences for all model pairs (p < 0.001). Specifically, the performance of LMFF–YOLO was significantly superior to that of YOLOv8n-seg (t(391) = −15.45, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = −0.704) and also to that of YOLOv11n-seg (t(363) = −15.90, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = −0.690), with both effect sizes being medium according to conventional guidelines.

Table 7.

Performance comparison of mainstream instance segmentation models.

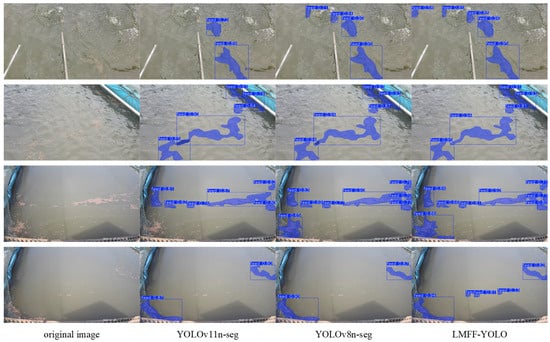

To visually observe the model’s practical performance, we randomly selected images from the test set for instance segmentation, as shown in Figure 11. Although YOLOv8n-seg and YOLOv11n-seg detected residual feed, they exhibited issues such as missed detections and duplicate segmentations. Their capture ability and accuracy for small targets are particularly weak. By contrast, LMFF–YOLO can more accurately segment small targets and complex residual feed clusters without duplicate segmentation, validating its higher stability and robustness and offering clear advantages in handling blurred boundaries.

Figure 11.

Visual comparison of segmentation results from different models.

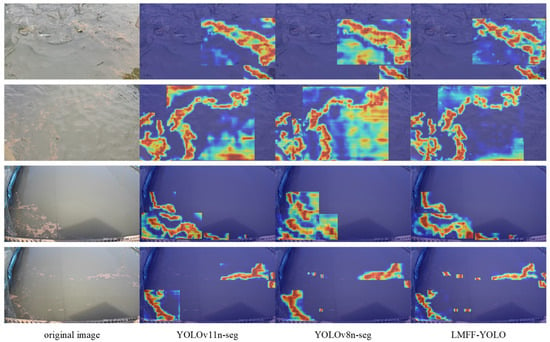

To further investigate the decision-making mechanisms and feature-focused characteristics of the different models, we employed gradient-weighted class activation mapping (Grad-CAM) for a visual comparative analysis. This approach reveals differences in attention distribution during the models’ recognition processes. In the heatmaps, areas ranging from yellow to deep red denote regions receiving heightened attention. This study selected typical image samples characterized by high background complexity, dense residual feed distribution, and weak boundary continuity. In such images, residual feed tends to be visually confused with the surrounding environment, posing a significant challenge to a model’s discrimination capabilities. The heatmaps shown in Figure 12 demonstrate that the high-response areas (red) generated by LMFF–YOLO heatmaps closely align with the actual shapes of the residual feed. This is particularly evident in the model’s ability to focus on small-scale targets, effectively separating the feed from the complex background. By contrast, the YOLOv8n-seg heatmap reveals significant misdirected attention toward the background or other irrelevant objects. While YOLOv11n-seg demonstrates more focused attention, its alignment with the actual residual feed contours remains inadequate. By contrast, LMFF–YOLO significantly enhances feature discrimination between targets and backgrounds while reducing false activations from the background. These results demonstrate that LMFF–YOLO outperforms the comparison models in multiscale feature fusion, fuzzy-boundary perception, robustness to complex backgrounds, and resistance to noise interference, exhibiting a more stable and precise segmentation performance.

Figure 12.

Grad-CAM heatmap visualizations for the various models. The red areas indicate high model attention.

4. Discussion

Accurate identification of floating residual feed is essential for advancing intelligent recirculating aquaculture systems. However, conventional vision-based methods often struggle to adapt to the complexities of outdoor environments. This study first established that an instance segmentation approach is fundamentally superior to individual object detection for processing clustered and adhesive feed residues, which are common in practice. To address the prevalent issues of high computational cost and limited real-time capability, we developed LMFF–YOLO, a lightweight model tailored for real-time, on-site segmentation.

Unlike prior studies conducted predominantly in controlled indoor settings, our work explicitly targets challenging outdoor aquaculture tanks, with the primary application scenario being continuous, in situ monitoring. To clarify this novel focus, Table 8 compares our approach with representative methods that excel on clear, discrete targets (e.g., fish or pellets) but are ill-suited for adhesive clumps. The LMFF–YOLO model is specifically engineered for this challenging scenario. Experimental validation demonstrates that LMFF–YOLO achieves an optimal balance between accuracy and efficiency. Specifically, it elevates the mAP50 metric by 2.6% while concurrently reducing parameter count and FLOPs by 19.1% and 20.0%, respectively, compared to the YOLOv8n-seg baseline. This combination of enhanced accuracy and lightweight design is not merely a technical improvement; it directly enhances deployment feasibility on resource-constrained edge devices, offering concrete technical support for real-time monitoring systems aimed at water quality management and intelligent feeding.

Table 8.

Comparison of related research on fish behavior recognition and feed identification.

4.1. Practical Application Value Discussion

The reported improvements in segmentation accuracy (mAP) possess direct practical significance for aquaculture management. The core advancement of our work lies in the ability to obtain precise pixel-level contours of residual feed patches, moving beyond mere detection or the coarse localization provided by bounding boxes. This capability facilitates a critical transition from qualitative observation to quantitative analysis. Specifically, enhanced segmentation precision translates directly into more accurate estimation of the total area covered by residual feed on the water surface. This metric serves as a more reliable indicator of feeding excess than estimates derived from object detection, which are sensitive to the variable morphology of feed clusters. Furthermore, accurate instance segmentation enables the analysis of the spatial distribution and density of feed residues, yielding insights into water flow patterns and feeding uniformity. Most importantly, the high-precision, pixel-level masks output by LMFF–YOLO directly represent the area and morphology of residual feed patches. This explicit representation of target geometry provides a critical data foundation that enables the quantification of coverage area and the analysis of spatial distribution. These capabilities are essential for transitioning from qualitative observation to quantitative monitoring, supporting the assessment of feeding efficiency and informing management decisions. Thus, the model’s core capability—producing accurate instance segmentation masks—establishes the necessary technical precondition for developing data-driven feed management systems.

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

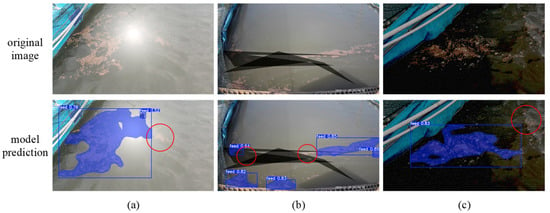

Several limitations and future directions are acknowledged. The model’s validation was primarily based on datasets from specific pond configurations with similar lighting and water color, which necessarily raises concerns about its performance under varying environmental conditions. The model maintains robust segmentation performance for reliable quantification of adhesive feed residues in most outdoor scenarios that share spectral characteristics with the training data, such as conditions without intense water surface agitation, strong glare, or severe shadow interference. However, performance may degrade under certain extreme or adverse environmental conditions, such as strong specular reflections that erase textural features, dramatic changes in water color due to algal blooms or turbidity, dense dynamic shadows that cause substantial occlusion, persistent surface disturbances caused by rainy conditions, or severely insufficient lighting that reduces image contrast and feature distinctiveness. Representative examples of these challenging conditions, approximated through controlled perturbations of key image features (e.g., strong glare, shadow occlusion, and low contrast light) via data augmentation, are visualized in Figure 13 to delineate the model’s sensitivity to such distribution shifts. As shown, under these challenging scenarios, issues such as missed detections occur, which are highlighted with red circles in the figure.

Figure 13.

Representative failure cases of the model under challenging simulated conditions. (a) Strong Glare; (b) Shadow Occlusion; and (c) Low Contrast Light.

Furthermore, the current research scope is confined to the visual recognition module. Future efforts should focus on translating the high-precision perceptual capability demonstrated here into practical management tools. This includes integrating this visual module with physical actuators and control algorithms to realize a fully operational system. A key direction will be developing models to convert the area data into actionable management parameters, which requires addressing challenges such as in-clump density variation. Concurrently, advancing model compression techniques to reduce parameters and FLOPs by an additional 30–50% while retaining >85% mAP50, and enhancing boundary segmentation precision by over 5% for adhesive clusters using advanced metrics. A key focus will be on improving cross-scenario robustness. This includes systematically evaluating and enhancing the model’s generalization and performance transfer capabilities across diverse farming environments (e.g., indoor vs. outdoor settings), with the goal of maintaining mAP50 above 80% across at least three distinct farm environments without retraining. Expanding the dataset, employing transfer learning techniques, and exploring avenues such as multimodal fusion are promising strategies to achieve these technical objectives and enhance the model’s adaptability and deployment potential in practical applications.

5. Conclusions

This study addressed the challenge of identifying floating fish residual feed, a critical task in outdoor recirculating aquaculture tanks. We first conducted a comparative analysis of residual feed individual detection and instance segmentation methods. The results demonstrated that instance segmentation is fundamentally more suitable for this application, as individual detection methods struggle with the small size of feed particles and the indistinct, blurred boundaries of aggregated feed clusters. Consequently, we proposed LMFF–YOLO, a lightweight instance segmentation model designed for real-time operation in outdoor environments. Experimental verification on a self-built residual feed dataset confirmed the effectiveness of our approach. The LMFF–YOLO algorithm improved mAP50 and mAP50-95 by 2.6 and 3.4%, respectively, over the YOLOv8-seg benchmark. Additionally, the model’s parameter count (Params) and computational load (FLOPs) were reduced by 6.2 M and 2.4 G, respectively, making it more suitable for deployment on devices with limited computational capabilities. Furthermore, visual comparisons against other mainstream models proved LMFF–YOLO’s superior performance in handling small-target segmentation, blurred boundaries, complex backgrounds, and noise interference. More importantly, this technical advancement has clear practical implications: the boost in segmentation accuracy enables precise pixel-level area quantification of residual feed, moving beyond mere detection. Coupled with its lightweight architecture, the model is deployable for continuous monitoring. In summary, LMFF–YOLO successfully meets the practical needs for accurately identifying floating fish residual feed in complex real-world environments. Beyond offering an efficient and lightweight solution, its precise segmentation capability has been shown to provide a more reliable measurement of feed coverage area, establishing a critical perceptual foundation for future quantitative management systems. This advancement is a crucial step towards developing intelligent feeding systems, by resolving the core identification challenge and enabling the next phase of research focused on data interpretation and control.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W. and C.T.; methodology, J.W. and C.T.; software, J.W.; validation, J.W.; formal analysis, J.W. and C.T.; investigation, J.W. and C.T.; resources, C.T.; data curation, J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, J.W.; writing—review and editing, J.W., C.T., X.X. and Y.W.; visualization, J.W.; supervision, C.T., X.X. and Y.W.; project administration, C.T., X.X. and Y.W.; funding acquisition, C.T. and Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation Upper-level Programs, grant number 2024JJ5209; Scientific Research Project of Hunan Provincial Department of Education—Excellent Young Scholars Project, grant number 24B0217; The Program for the Key Research and Development Project of Hunan Province, China, grant number 2025JK2027.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

For data supporting the results of this study, please contact the author for communication. Due to privacy, these data have not been made public.

Acknowledgments

Expressions of gratitude are extended to Kaitian New Agricultural Science and Technology Co. in Hunan Province, China, for their provision of the designated test site, and to Hu Haoyu and Li Mi for their invaluable contributions to the present paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Laktuka, K.; Kalnbalkite, A.; Sniega, L.; Logins, K.; Lauka, D. Towards the Sustainable Intensification of Aquaculture: Exploring Possible Ways Forward. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, B.; Sun, X.; Hong, Q.; Duan, Q. Intelligent fish feeding based on machine vision: A review. Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 231, 133–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Xu, Q.; Lyu, H.; Kong, J.; Wang, X.; Shen, B.; Bi, Y. Sediment and residual feed from aquaculture water bodies threaten aquatic environmental ecosystem: Interactions among algae, heavy metals, and nutrients. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 326, 116735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A.; Ghosh, A.R. Role of artificial intelligence (AI) in fish growth and health status monitoring: A review on sustainable aquaculture. Aquac. Int. 2024, 32, 2791–2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, W.; Wei, D.; Peng, Z.; Ma, Z.; Zhu, S.; Tang, R.; Tian, X.; Zhao, J.; Ye, Z. An appetite assessment method for fish in outdoor ponds with anti-shadow disturbance. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 221, 108940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, C.; Rhodes, M.A.; Davis, D.A. Feed management and the use of automatic feeders in the pond production of Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Aquaculture 2019, 498, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, X. A remote acoustic monitoring system for offshore aquaculture fish cage. In Proceedings of the 2007 14th International Conference on Mechatronics and Machine Vision in Practice, Xiamen, China, 4–6 December 2007; pp. 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juell, J.-E. Hydroacoustic detection of food waste—A method to estimate maximum food intake of fish populations in sea cages. Aquac. Eng. 1991, 10, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorens, S.; Pérez-Arjona, I.; Soliveres, E.; Espinosa, V. Detection and target strength measurements of uneaten feed pellets with a single beam echosounder. Aquac. Eng. 2017, 78, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atoum, Y.; Srivastava, S.; Liu, X. Automatic feeding control for dense aquaculture fish tanks. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2015, 22, 1089–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.-C.; Tsao, S.-C.; Huang, K.-H.; Jang, J.-P.; Chang, H.-K.; Dobbs, F.C. A highly sensitive underwater video system for use in turbid aquaculture ponds. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Xu, L.; Liu, H. Detection of uneaten fish food pellets in underwater images for aquaculture. Aquac. Eng. 2017, 78, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fini, C.; Amato, S.G.; Scutaru, D.; Biancardi, S.; Antonucci, F.; Violino, S.; Ortenzi, L.; Nemmi, E.N.; Mei, A.; Pallottino, F.; et al. Application of Generative Artificial Intelligence in the aquacultural sector. Aquac. Eng. 2025, 111, 102568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Zhao, B.; Shi, Y. Computer Vision for Site-Specific Weed Management in Precision Agriculture: A Review. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, Y.; Wang, T. YOLOv8-BaitScan: A Lightweight and Robust Framework for Accurate Bait Detection and Counting in Aquaculture. Fishes 2025, 10, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; An, D.; Wei, Y. Research on fish bait particles counting model based on improved MCNN. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 196, 106858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wang, Z.; Du, R.; Li, Y.; Li, D.; Chen, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, C. A method for detecting uneaten feed based on improved YOLOv5. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 212, 108101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Jiang, P.; Wang, Y.; Hu, S.; Chen, S.; Li, R.; Huang, H.; Li, N.; Zhang, B.; Ke, Q.; et al. YOLO-feed: An advanced lightweight network enabling real-time, high-precision detection of feed pellets on CPU devices and its applications in quantifying individual fish feed intake. Aquaculture 2025, 608, 742700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.M.; Jim, J.R.; Istenes, Z. Terrain detection and segmentation for autonomous vehicle navigation: A state-of-the-art systematic review. Inf. Fusion 2025, 113, 102644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Yang, Q.; Yang, L.; Shen, T.; Wang, R.; Fu, C. Deep learning implementation of image segmentation in agricultural applications: A comprehensive review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Qian, C.; Xu, J.; Tu, X.; Jiang, X.; Liu, S. Salient Object Detection Guided Fish Phenotype Segmentation in High-Density Underwater Scenes via Multi-Task Learning. Fishes 2025, 10, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Tang, C.; Shi, C.; Qian, Y. Detection of residual feed in aquaculture using YOLO and Mask RCNN. Aquac. Eng. 2023, 100, 102304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.Q.; Yan, F.; Yang, Y.; Li, H.Y. MMF-YOLO algorithm for detection of micro-defects on wafer mold surfaces. Comput. Eng. Appl. 2025, 61, 132–143. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Yeh, I.-H.; Liao, H.-Y.M. YOLOv9: Learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2024; Leonardis, A., Ricci, E., Roth, S., Russakovsky, O., Sattler, T., Varol, G., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G. Rep ViT: Revisiting mobile CNN from ViT perspective. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 15909–15920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Wan, Y. ELA: Efficient local attention for deep convolutional neural networks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.01123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; He, Z.; Lu, Z.-M. DEA-net: Single image dehazing based on detail-enhanced convolution and content-guided attention. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2024, 33, 1002–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, A.; Zha, H. (Eds.) Computer Vision—ECCV 2024; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 246–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, U.; Li, D.; Qureshi, M.F.; Mushtaq, Z.; ur Rehman, H.A. LightHybridNet-Transformer-FFIA: A hybrid Transformer based deep learning model for enhanced fish feeding intensity classification. Aquac. Eng. 2025, 111, 102604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Yu, G.; Liu, H.; He, Z. Segmentation and calculation of splashes area during fish feeding using deep learning and linear regression. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 234, 110208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, T.; Yang, S.; Fan, M.; Lu, J.; Guo, A. FishSegNet-PRL: A Lightweight Model for High-Precision Fish Instance Segmentation and Feeding Intensity Quantification. Fishes 2025, 10, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.