Abstract

Rice–fishery integrated farming has expanded rapidly in China, yet its implications for arsenic (As) accumulation remain insufficiently understood. This study evaluated As bioavailability and enrichment in a rice–crayfish farming system (RCFS) by establishing controlled field plots with soil As concentrations ranging from 5 to 40 mg/kg under three water-management regimes: alternating wetting and drying (AWD), continuously flooded (CF), and RCFS. Soil–water physicochemical variables and As accumulation in both rice organs and crayfish tissues were systematically analyzed, followed by human health risk assessment. Inorganic As in brown rice increased linearly with soil As, following Y = 0.0117X + 0.0598 (R2 = 0.96), and the estimated soil safety thresholds were 26.48 mg/kg for AWD, 11.98 mg/kg for RCFS, and 9.24 mg/kg for CF. AWD consistently exhibited the lowest As risk due to its ability to elevate soil Eh and maintain a more favorable pH, thereby suppressing As mobilization. Compared with CF, RCFS reduced As bioavailability through crayfish-induced bioturbation, which increased Eh, enhanced SOM and CEC, and improved soil aeration. As accumulation in crayfish tissues also rose with soil As, with abdominal muscle As fitting Y = 0.0085X + 0.0553 (R2 = 0.8588). Although abdominal muscle met safety limits, the hepatopancreas accumulated substantially higher As and exceeded carcinogenic risk thresholds, even at 5 mg/kg of soil As, indicating a potential health concern for consumers. This work elucidates As dynamics and enrichment mechanisms in RCFS, providing guidance for safer rice–crayfish production in As-impacted areas.

Key Contribution:

This study determines the safe arsenic concentrations for rice and fish in RCFS, clarifies the arsenic pollution risks within RCFS, and provides important reference data for paddy field production.

1. Introduction

Arsenic is a highly persistent, toxic, bioaccumulative, and bioavailable heavy metal that has been recognized as a class A carcinogen by international authorities such as the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control [1,2]. Arsenic is commonly used in the production of pesticides, such as insecticides and herbicides, and has caused serious contamination of agricultural land in several countries and regions around the world, such as Bangladesh, China, and Japan [3]. Rice is often grown in flooded paddy soils that readily mobilize arsenic, so arsenic-contaminated farmland can directly translate into arsenic-accumulating rice, posing a serious threat to global food safety and human health.

Numerous studies have been conducted on the bioavailability of arsenic in AWD. Arsenic exists in soil as inorganic and organic arsenic forms, most of which are inorganic, including As (III) and As (V) [2]. Organic arsenic includes MMA and DMA, but accounts for a very low percentage of total soil arsenic. The uptake capacity of rice for different forms of arsenic varies greatly, and the uptake capacity of rice for inorganic arsenic is significantly stronger than that of organic arsenic. As (III) in inorganic arsenic is more easily absorbed by rice roots than As (V). Arsenic bioavailability is affected by the physicochemical properties of the soil [4]. Studies have shown that redox conditions are one of the key factors influencing the stability of exogenous arsenic or changes in the bound form in soil. Under biased reducing conditions, where arsenic mainly exists in the form of trivalent arsenic oxyanions, anaerobic microorganisms consume protons and pH increases, leading to weakened adsorption of trivalent arsenic between the trivalent arsenic and soil minerals, resulting in arsenic desorption. Under biased oxidizing conditions, arsenic mainly exists in the form of pentavalent arsenic compounds. Compared with trivalent arsenic, pentavalent arsenic is less active in soil, and amorphous iron oxides are more easily converted to trivalent iron oxides with a high degree of crystallinity, which promotes the conversion of easy-to-migrate state arsenic to a relatively difficult-to-migrate state.

In integrated rice–aquatic animal systems, the presence and activities of aquatic animals can further modify flooding regimes, redox conditions, and organic matter dynamics in paddy soils, potentially altering arsenic speciation and bioavailability; however, these effects remain poorly quantified and warrant systematic investigation. Similar studies in aquatic–rice or aquatic–sediment systems have shown that fish and crustaceans can accumulate toxic elements from both water and sediments under real environmental conditions [5,6]. Crayfish is a widely distributed freshwater species and has become highly popular in many Asian countries due to its strong market demand and culinary value. Owing to its high economic returns and perceived environmental benefits, the rice–crayfish farming system (RCFS) has expanded rapidly in recent decades, with China alone cultivating more than 15,667 km2 of RCFS farmland. Relative to the AWD, the RCFS produces significant changes in the physicochemical properties of the soil–water system on the farmland due to flooding throughout the entire life cycle and the introduction of crayfish. The bioavailability of arsenic in RCFS has not been reported so far.

In this experiment, a controlled mesocosm system was constructed to simulate arsenic-contaminated rice–crayfish farming conditions and to investigate arsenic behavior within this integrated system. We aimed to (i) characterize the temporal dynamics of key soil–water physicochemical parameters in RCFS in comparison with conventional flooding and AWD; (ii) quantify arsenic accumulation patterns in rice and crayfish across graded soil arsenic levels; and (iii) discuss how RCFS-induced environmental changes may influence arsenic speciation, mobility, and bioavailability. The results are expected to provide a scientific basis for arsenic risk assessment and to support the safe and sustainable development of rice–crayfish farming systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

This semi-field mesocosm experiment was conducted to evaluate arsenic (As) migration, bioavailability, and accumulation in rice–crayfish farming systems (RCFS). Three farming modes were compared: RCFS, alternating wetting and drying (AWD), and conventional flooding (CF). For each mode, six soil As levels were established (background, 5.0, 9.0, 15.0, 25.0, and 40.0 mg/kg). Each treatment consisted of three independent plastic-box mesocosms (130 cm × 60 cm × 50 cm), which served as biological replicates. In total, 54 mesocosms (3 farming modes × 6 As levels × 3 replicates) were prepared, filled with pre-treated soil, and managed according to the procedures described below (Section 2.1.1, Section 2.1.2, Section 2.1.3 and Section 2.1.4). Rice, watercress, and crayfish were subsequently introduced according to the requirements of each farming mode.

The entire experiment spanned a full rice-growing season. After soil preparation and a 30-day arsenic aging period, rice was transplanted and maintained until maturity (~120 days), with crayfish stocked 40 days after transplanting in the RCFS treatment. All measurements and sample collections were conducted within this experimental timeline.

2.1.1. Pollution Modeling

Surface paddy soil was collected from Wenjiang, Sichuan Province, by removing the top 2 cm and eliminating stones and plant debris. The soil was air-dried, homogenized, and sieved (2 mm), after which its moisture content, basic physicochemical properties (pH, redox potential, cation-exchange capacity, soil texture, nutrients, and organic matter), and background metal levels (As, Cd, Fe, Zn, Mn) were analyzed.

Sodium arsenite (NaAsO2, 232-070-5, Sigma, Saint Louis, MO, USA) was used as the As source. The required mass was calculated based on the target concentrations and the initial soil As content, dissolved in distilled water, and sprayed evenly onto the soil. To ensure homogeneous incorporation of arsenic, the soil–solution mixture was blended using an overhead mechanical stirrer (Model RW20 Digital, IKA Works, Staufen, Germany) equipped with a paddle impeller at 30 rpm for 15 min, followed by gentle agitation on a platform shaker (Model SK-O180-S, Scilogex, Rocky Hill, CT, USA) for 20 min. The spiked soil was then air-dried back to its initial moisture content, re-sieved (2 mm), and randomly subsampled at five points to verify As homogeneity (coefficient of variation <5%). Total arsenic concentrations were determined after acid digestion to confirm the uniform distribution of As in the spiked soil. For each mesocosm, 280 kg of the prepared soil was loaded into a plastic box (130 cm × 60 cm × 50 cm), leveled to ~30 cm depth, and flooded with 5 cm of water for a 14-day aging period to allow stabilization of arsenic in the soil matrix. In RCFS treatments, a ridge–furrow structure (~20 cm) was constructed five days before rice transplantation.

2.1.2. Rice and Watercress Planting

After 10 days of arsenic aging, basal fertilizer was applied at a rate of 25 kg mu−1 of ammonium bicarbonate, and rice seedlings were transplanted four days later. The rice variety used was Lu You 9803, an indica three-line hybrid medium-duration cultivar with a growth period of approximately 134 days in the Chengdu Plain. Uniform, healthy seedlings free of visible damage or disease and with uniform height were selected. Six seedlings were transplanted into each mesocosm (three on each side) at a spacing of 30 cm. Watercress (Xanthium sibiricum) was planted as the aquatic vegetation in RCFS and CF units, with an initial coverage of ~20%, and was manually trimmed once per month to prevent excessive growth.

2.1.3. Crayfish Stocking and Management

The experimental crayfish (Procambarus clarkii) were obtained from a commercial farm in Chengdu and selected for uniformity in size (5.25 ± 0.36 g), appearance, and health, with no signs of disease, injury, or deformity. Prior to stocking, the crayfish were acclimated in aerated freshwater for 14 days. At 40 days after rice transplanting, similarly sized individuals were selected and introduced into each mesocosm at a density of 12 individuals per box. During the experimental period, the crayfish were fed a commercial sinking pellet feed (8636, Tongwei Co., Ltd., Chengdu, China) at approximately 4% of their body weight per day. Pre-experimental screening confirmed that arsenic was not detected (ND < LOD) in the feed.

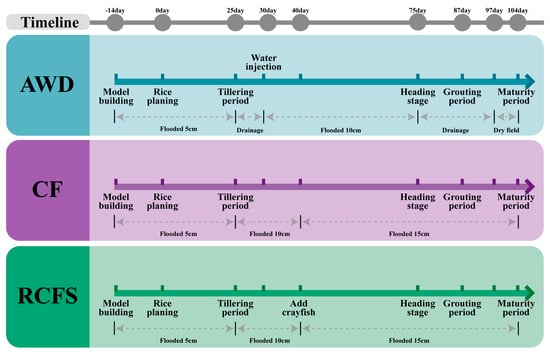

2.1.4. Water Level Management

In the RCFS and CF treatments, fields were continuously flooded throughout the rice-growing season. Water depth was maintained at approximately 5 cm at transplanting, increased to ~10 cm during the tillering stage, and further increased to ~15 cm from the heading stage until maturity. In the AWD treatment, water management followed a phenology-based alternating wet–dry cycle. After transplanting, a 5 cm water layer was maintained. During the tillering stage (around 25 d), the field was allowed to drain naturally until the soil surface became dry, after which it was reflooded to ~10 cm during subsequent stem elongation, jointing, and booting stages (around 30 d). A second drying phase occurred after heading (around 75 d), during which the field was kept dry throughout the grain-filling period (87–97 d). Final drainage occurred 15 days before harvest to facilitate grain maturation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Water level management for three models.

2.2. Sample Collection

2.2.1. Sampling Schedule for Water and Soil Physicochemical Parameters

Water and soil physicochemical parameters (DO, EC/TDS, soil Eh, pH, CEC, and SOM) were monitored throughout the rice-growing period at nine phenology-based sampling points: −14, 1, 15, 29, 43, 57, 71, 85, and 99 days relative to rice transplanting, corresponding to pre-flood soil stabilization, transplanting, early tillering, late tillering, jointing, early heading, mid heading, mid filling, and late filling stages. In the AWD treatment, water sampling was performed only when a stable standing-water layer was present. Because the AWD field exhibited only transient or negligible surface water at 85 days and entered the scheduled dry phase by 99 days, no water samples were obtained for these two time points. A total of 1458 individual measurements were collected across the experiment (three farming modes × six arsenic concentrations × three biological replicates × nine sampling time points × three technical replicates). For statistical analysis, technical replicates were averaged within each mesocosm, and these averaged values were used as the biological observations (n = 486) in the final dataset. Water measurements in the AWD treatment were not available at 85 and 99 days because the field did not maintain a stable standing-water layer during these scheduled dry-phase periods. In addition, preliminary observations indicated that soil and water physicochemical parameters were not substantially affected by the arsenic concentration; therefore, environmental parameters were analyzed at the farming level rather than along arsenic gradients.

Water temperature, dissolved oxygen (DO), and electrical conductivity (EC) in each mesocosm were measured in situ using a portable multi-parameter water quality meter (HQ40d, Hach, Loveland, CO, USA), and total dissolved solids (TDS) were recorded simultaneously based on EC readings. Soil redox potential (Eh) was determined using a platinum electrode with an Ag/AgCl reference electrode (RM-30P, Toa-DKK, CORPORATION, Tokyo, Japan) inserted at a 10 cm depth, with readings corrected to the standard hydrogen electrode. Soil pH was measured on air-dried samples using a bench-top pH meter (PHS-3C, INESA, Shanghai, China) at a 1:2.5 (w/v) soil-to-water ratio. Cation exchange capacity (CEC) was analyzed using the ammonium acetate (pH 7.0) displacement method, and soil organic matter (SOM) was determined using the potassium dichromate oxidation (Walkley–Black) method, following standard soil physicochemical procedures.

2.2.2. Growth Trait Assessment and Tissue Sampling in Crayfish

At the time of rice harvest, all crayfish from each mesocosm were collected using hand nets, and the number of surviving individuals was recorded to calculate the survival rate. The total biomass of surviving crayfish in each mesocosm was measured using an electronic balance, and the mean individual body weight was obtained as the ratio of total biomass to the number of survivors. Based on the initial and final mean body weights, the specific growth rate (SGR) and overall growth rate of crayfish in each mesocosm were calculated using standard growth equations.

For arsenic analysis, six crayfish were randomly selected from each mesocosm in the RCFS treatment, yielding a total of 108 individuals (six arsenic concentrations × three biological replicates × six crayfish per mesocosm). All procedures involving crayfish followed institutional guidelines for the ethical use of animals (protocol code: SC2021019, 28 May 2021). Crayfish were anaesthetized via immersion in ice-chilled water until loss of response and subsequently euthanized via swift destruction of the cerebral ganglia prior to dissection. Each individual was placed on a sterile dissection board, the dorsal carapace was opened, and six tissues—abdominal muscle, cheliped muscle, cephalothorax tissue, gill, hepatopancreas, and intestine—were excised using stainless-steel dissection tools. A total of 108 composite tissue samples were obtained for arsenic determination (6 tissue types × 18 mesocosms), with each composite prepared by pooling the same tissue from six crayfish within each mesocosm, and each composite measured in triplicate technical replicates that were averaged for use in the analysis.

All tissue samples were gently rinsed with deionized water to remove adhering debris, blotted dry with lint-free paper, placed into pre-labeled polyethylene bags or centrifuge tubes, and immediately frozen at −20 °C (or below) until further processing for arsenic analysis.

2.2.3. Measurement of Agronomic Traits in Rice

At rice maturity, plants were harvested from each mesocosm to evaluate agronomic traits and to obtain tissues for arsenic determination. Five representative hills were randomly selected along the diagonal of each mesocosm. For each hill, plant height, main panicle length, number of tillers, number of effective panicles, and spikelet-setting rate were recorded. Aboveground and belowground biomass were measured after oven-drying at 65 °C to a constant weight. Well-filled grains from the main panicle were used to determine thousand-grain weight and main panicle grain weight.

For arsenic analysis, plants from the selected hills were separated into roots, stems, leaves, and brown rice. Root samples were gently washed with deionized water to remove adhered soil; stems and leaves were cut from the culm at the node positions, and brown rice was obtained by dehulling air-dried grains using a laboratory rice huller. A total of 216 composite rice tissue samples were obtained for arsenic determination (4 tissue types × three farming modes × six arsenic concentrations × three biological replicates), with each composite prepared by pooling the corresponding tissue from the five sampled hills within each mesocosm and measured in three technical replicates, whose averaged values were used for analysis.

All tissue samples were oven-dried at 65 °C, ground to a fine powder, homogenized, and stored in airtight polyethylene tubes at −20 °C until arsenic determination.

2.3. Arsenic Testing

Samples of crayfish and rice tissues obtained as described in Section 2.2 were used for arsenic determination. Arsenic concentrations in feed, soil, crayfish, and rice were determined following the method outlined by Zhao et al. (2009) [7]. Samples were oven-dried, finely ground, homogenized, digested using HNO3–H2O2 in a microwave digestion system, and analyzed to determine total arsenic (As) using ICP–MS (NexION 350X, PerkinElmer, Norwalk, CT, USA). The limits of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ) were 0.001 mg/kg and 0.003 mg/kg, respectively. Quality control included procedural blanks, duplicate samples, and certified reference materials. Arsenic was not detected in the feed or the aerated tap water used in the experiment (ND < LOD).

2.4. Health Risk Assessment

Human health risks associated with rice and crayfish consumption were assessed following standard U.S. EPA methods. Non-carcinogenic risk was expressed as the target hazard quotient (THQ):

where EF (exposure frequency), ED (exposure duration), IR (ingestion rate), C (arsenic concentration in food), BW (body weight), AT (average exposure time = F × ED), and RfD (reference dose = 0.0003 mg/kg/day for inorganic As) follow values adopted from Tao Chunjun and U.S. EPA guidelines (Table 1).

Table 1.

Parameters used in the health risk assessment.

Carcinogenic risk (CR) was calculated as

where the cancer slope factor (CSF) for arsenic is 15.0 mg/kg/day. Because cooking processes generally reduce arsenic concentrations, the obtained risk values represent conservative estimates.

2.5. Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 20.0, Excel 2016, and GraphPad Prism 8. Technical replicates were averaged prior to analysis, and all statistical tests were based on biological replicates (mesocosms). Environmental parameters (DO, EC/TDS, soil Eh, pH, CEC, and SOM) were analyzed at the farming level, because preliminary observations indicated that arsenic concentration did not substantially affect these variables. For each sampling time, values from the six arsenic treatments were therefore averaged within each mode and used to construct the temporal trends. For rice and crayfish growth traits, as well as for arsenic concentrations in rice and crayfish tissues, data were analyzed within each farming mode using one-way ANOVA, with the soil arsenic concentration as the single fixed factor. Normality and homogeneity of variance were tested prior to ANOVA, and Duncan’s multiple range test was used when significant differences were detected (p < 0.05). Dose–response relationships between the soil arsenic concentration and arsenic accumulation in soil, water, rice tissues, and crayfish tissues were examined using linear regression models fitted separately for each farming mode. Model performance was evaluated using the fitted regression equations and their corresponding R2 values. Soil arsenic thresholds were extrapolated from these regressions based on national food safety limits.

3. Results

3.1. Dynamics of Physical and Chemical Indicators of the Soil–Water System

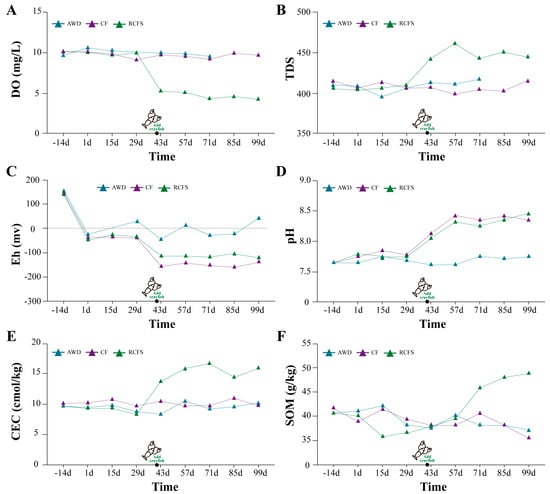

Before the addition of crayfish, the water dissolved oxygen in the RCFS, CF, and AWD showed a daily pattern of high at noon, low in the evening, and medium in the morning, with a mean value of 9–10 mg/L, and there was no significant difference in the daily mean values among the three groups. However, after the crayfish were put in, the daily mean value of redissolved oxygen in the RCFS decreased rapidly to about 4.8 mg/L and was significantly lower than that of the remaining two groups (p < 0.05) (Figure 2A). Before crayfish were put in, the TDS of all three models was around 407 S/m; however, after crayfish were put in, the conductivity of the rice–shrimp system rapidly increased to 460 S/m and then remained around 440 S/m. The TDS of the rice–shrimp system was around 440 S/m (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Dynamics of physicochemical indicators of soil–water system in three models.

Soil Eh was maintained around −30 mv 15 days before and 15 days after rice planting; in the AWD, soil Eh rose to 30 mv at 15 d–43 d due to intermittent flooding and fall-drying, decreased to -16 mv at 43 d–71 d, and rose to 45 mv between 71 d and 99 d; in the CF, soil Eh increased with the rise of the water level, decreased to −150 mv between 29 d–43 d decreased to −150 mv, and remained between −150 mv and 200 mv until the end of the experiment. The trend of soil Eh in the RCFS was similar to that of the flooded mode, but after 43 days of crayfish release, soil Eh basically remained around -110 mv, which was significantly higher than that of the flooded mode (p < 0.05) (Figure 2C).

The soil pH of the AWD has been relatively stable and maintained around 7.70. The RCFS and the CF slowly increased the soil pH to 8.30 after being flooded all the time. Soil pH in the RCFS was slightly lower than that of the CF during the period of 40 d–99 d of crayfish release (Figure 2D).

The soil CEC in the AWD and CF was relatively smooth, while in the RCFS, it rose rapidly after 43 days and then remained between 14 and 16 cmol/kg, which was significantly higher than that in the AWD and CF (p < 0.05) (Figure 2E).

SOM content in the CF and AWD showed a continuous and slow decreasing trend after planting rice. In the RCFS, it showed a continuous and slow decreasing trend after planting rice, but an increasing trend in SOM content after 57 d. SOM content at rice maturity decreased by 14.6% and 9.02% in the CF and AWD, respectively, compared with that at planting, while it increased by 19.9% in the RCFS (Figure 2F).

3.2. Characterization of Arsenic Enrichment in Crayfish

In the RCFS, crayfish survival was not significantly different at contaminant concentrations of 5.0 mg/kg–25.0 mg/kg, but it was significantly reduced when the contaminant concentration reached 40.0 mg/kg (Figure S1A). The specific growth rate of crayfish ranged from 90.25 to 99.25%/d at soil arsenic concentrations of 5.0 mg/kg–15.0 mg/kg and decreased to 51.50%/d in the 40 mg/kg treatment group, which was significantly lower than the other groups (Figure S1B). The growth rate of crayfish ranged from 115 to 136% at soil arsenic concentrations of 5.0 mg/kg–15.0 mg/kg, decreased to 88% when the contamination concentration increased to 25.0 mg/kg, and plummeted to 54% when the soil arsenic concentration reached 40.0 mg/kg, which was significantly lower than that of the low-concentration group (p < 0.05) (Figure S1C).

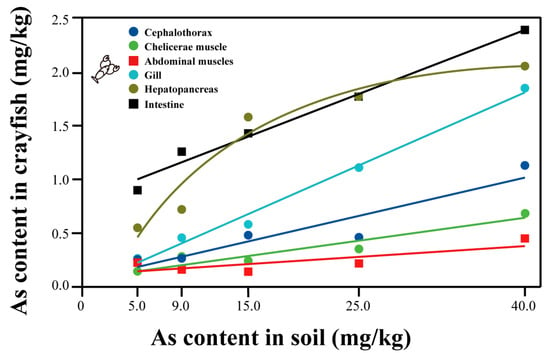

At the same concentration, the overall trend of arsenic content in various tissues of crayfish was abdominal muscle < chelicerae muscle < cephalothorax < gill < hepatopancreas < intestine. The arsenic content in each tissue of crayfish increased with increasing soil arsenic concentration, showing a significant dose effect. The relationship equation between the arsenic content in the abdominal muscle (the main edible part of crayfish) and soil arsenic was Y = 0.0085X + 0.0553 (R2 = 0.8588), and the safety threshold for soil arsenic was deduced to be 52.29 mg/kg according to (GB2762-2022 National Standard for Food Safety Limits of Pollutants in Foods [8]). The relationship equation for the hepatopancreas, which was preferred by some diners as part of the food, was Y = 0.0431X + 0.5245 (R2 = 0.825) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Regression equation of arsenic content in crayfish tissues and soil arsenic concentration.

3.3. Characterization of Arsenic Enrichment in Rice

The aboveground length and plant height of rice in the RCFS were significantly higher than those in the CF and the AWD (p < 0.05), and there were no significant differences (p > 0.05) in the belowground length, main spike length, number of tillers, number of effective spikes, fruiting rate, and thousand-grain weight of the three modes (Table S1).

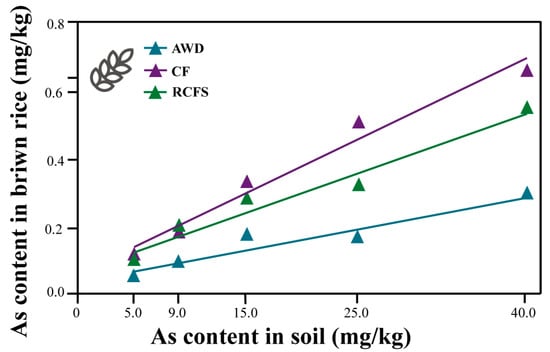

Regardless of the mode and pollution concentration, the overall trend of arsenic enrichment in rice tissues was root > stem > brown rice; in the three modes, arsenic content in rice roots, stems, leaves, and brown rice increased with the increase in arsenic concentration in soil (Figure S2A–C). At the same pollution concentration, the overall trend of arsenic content in brown rice was CF > RCFS > AWD (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Regression equation of brown rice and soil arsenic content.

The arsenic content of brown rice in the three modes in relation to the arsenic content of the soil was determined using the following equations: RCFS: y = 0.0117x + 0.0598 (R2 = 0.9600), CF: y = 0.0159x + 0.0532 (R2 = 0.9729), and AWD: y = 0.0063x + 0.0332 (R2 = 0.9116). According to the (GB2762-2022 National Standard for Food Safety Limits of Contaminants in Food) inorganic arsenic threshold (0.2 mg/kg) for brown rice, soil arsenic safety thresholds were extrapolated as 11.98 mg/kg, 9.24 mg/kg, and 26.48 mg/kg for RCFS, CF, and AWD, respectively (Figure 4).

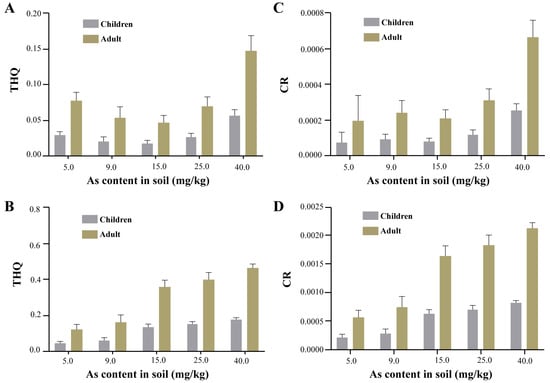

3.4. Risk Assessment

Under the same soil arsenic contamination conditions, the non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic risks of crayfish tissues to adults and children were positively correlated with soil arsenic concentrations. Hepatopancreas non-carcinogenic risk and carcinogenic risk were higher than in abdominal muscles. In the 40 mg/kg treatment group, the non-carcinogenic risk of abdominal muscle and hepatopancreas (Figure 5A,B) did not exceed the guideline values. For children, the carcinogenic risk of the abdominal muscle of crayfish did not exceed 10−4 at any soil arsenic concentration lower than 15.0 mg/kg, but when the soil arsenic concentration reached 25.0 mg/kg, the carcinogenic risk of the abdominal muscle was 1.2 × 10−4 > 1 × 10−4 (Figure 5C); the carcinogenic risk of the hepatopancreas of crayfish already reached 3.17 × 10−4, even in low-concentration conditions (Figure 5D), indicating that the hepatopancreas of crayfish is a potential carcinogenic risk for children. For adults, the carcinogenic risk due to abdominal muscle and hepatopancreas exceeded 10−4 at a soil arsenic concentration of 5.0 mg/kg (Figure 5C,D), suggesting that crayfish produced in the RCFS poses a potential carcinogenic risk to adults.

Figure 5.

Non-carcinogenic risk and carcinogenic risk of crayfish. ((A,C): abdominal muscle; (B,D): hepatopancreas).

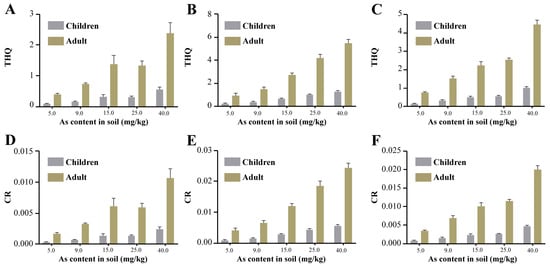

The non-carcinogenic risk of brown rice for both children and adults was positively correlated with soil arsenic concentration and showed a trend of CF > RCFS > AWD. At the same soil arsenic concentration, the non-carcinogenic risk of adults was higher than that of children. In the AWD (Figure 6A), the non-carcinogenic risk of brown rice for children was below the guideline value of 1 in all cases, while the non-carcinogenic risk for adults was 1.37 at a soil arsenic concentration of 15 mg/kg. In the CF (Figure 6B) and RCFS (Figure 6C), the non-carcinogenic risk of brown rice for children was 1.53 and 1.03 only under high contamination conditions (40 mg/kg), while the non-carcinogenic risk for adults was 1.44 and 1.53, respectively, at a soil arsenic concentration of 9 mg/kg. In all three models, the carcinogenic risk of brown rice to children and adults was positively correlated with the soil arsenic concentration and showed a trend of CF > RCFS > AWD (Figure 6D–F). Carcinogenic risk was higher in adults than in children at all the same soil arsenic concentrations. The carcinogenic risk exceeded 10−4 at all concentrations in all three models.

Figure 6.

Non-carcinogenic risk (THQ; (A–C)) and carcinogenic risk (CR; (D–F)) of brown rice under different irrigation regimes. ((A,D): AWD; (B,E): CF; (C,F): RCFS).

4. Discussion

4.1. Characterizing the Dynamics of Physicochemical Properties of Soil–Water Systems in the RCFS

It has been shown that macrobenthos has a significant impact on biogeochemical processes at the sediment–water interface [9,10,11]. The introduction of crayfish into the RCFS resulted in a wide range of physicochemical factors in the soil–water system, which differed significantly from the other two models. RCFS (with the addition of crayfish in the water after the rapid decline in dissolved oxygen) resulted in a lower level of dissolved oxygen. On the one hand, the crayfish’s own respiratory oxygen consumption reduces the dissolved oxygen in the water; on the other hand, the crayfish’s various activities (foraging, chasing, swimming, etc.) formed a kind of bioturbation caused by a reduction in the transparency of the water, restricting the water in the algae’s ability to produce oxygen [12].

Soil Eh was consistently low in RCFS compared to AWD, mainly because the RCFS was flooded, blocking airborne oxygen from reaching the soil [13,14]. The relatively higher soil Eh in the RCFS compared to the CF may be attributed to the strong bioturbation effect of crayfish. Crayfish build burrows within the sediment, which increases the contact area between the sediment and the overlying water. Due to foraging, resting, enemy avoidance, and other behaviors, crayfish frequently go in and out of the burrow, introducing oxygen into the water through the sediment–water interface into the interior of the sediment to alleviate the anaerobic state of the soil caused by prolonged flooding.

The SOM content of the soil in RCFS increased after adding crayfish for a period of time, mainly due to the residual bait and feces produced during crayfish farming, which were converted into SOM by microbial decomposition. CEC also increased gradually after crayfish were released into RCFS, which may be due to the increase in SOM.

4.2. Characterization of Arsenic Enrichment in Crayfish and Risk Assessment

It has been shown that the accumulation of heavy metals in crayfish depends on the rate of absorption, storage, and elimination [15]. Heavy metals enter the body through respiration in the gills, absorption in the digestive tract, and osmosis from the body surface, and ultimately enter the circulatory system and flow throughout the body, thus accumulating in various tissues and organs [16,17]. There were significant differences in the accumulation characteristics of individual tissues, and in the present study, arsenic accumulation in crayfish organs generally followed the order of abdominal muscles < chelicerae muscle < cephalothorax < gill < hepatopancreas < intestine, consistent with studies in other shrimp or fish species [17] (Gedik et al., 2016).

Gills have a very wide surface area for rapid diffusion of heavy metals and are an important pathway for heavy metal ions to enter the body from water [18,19]. Some studies have reported high accumulation of arsenic in gills [20,21,22,23]. In the present study, although the accumulation of arsenic in gills was low, it does not mean that very little arsenic enters the body through the gills; this may be due to the redistribution of arsenic accumulated in gills through blood circulation. The intestinal tract is a reservoir for heavy metal absorption, and heavy metals can be excreted into the intestines via bile [24]. Crayfish are omnivores and feed on wiggler larvae, flea-like larvae, larger zooplankton, and even aquatic plants in addition to commercial forage. When crayfish feed, some sediment enters the gut with the food, which may be an important reason for the high accumulation of arsenic in the gut. The hepatopancreas and kidneys of crayfish are susceptible to metal enrichment, and metallothioneins are closely associated with heavy metal exposure; heavy metals absorbed from the environment can be detoxified by binding to these proteins [25]. In addition, heavy metals are partially deposited in the cephalothoracic armor, and crayfish can reduce their heavy metal burden in the body by molting their shells, which is excreted with the shedding of the cephalothoracic armor. As the most dominant edible part, the accumulation of arsenic in the abdominal muscle of crayfish is low, a result that is the same as in many other shrimp or fish species [26,27,28]. The soil safety threshold was inferred from the regression equation between arsenic concentration in muscle and arsenic concentration in soil as 52.29 mg/kg, which is much higher than that of rice. These results suggest that the food safety of rice in RCFS is more vulnerable. There are many people who like to consume the hepatopancreas of crayfish, and the results of this study showed that the arsenic level in the hepatopancreas was much higher than that in the abdominal muscles. According to the risk assessment in this study, consumption of hepatopancreas poses a high carcinogenic risk to adults and is recommended to be consumed in small amounts.

The uptake of arsenic by crayfish may be influenced by many factors, as soil arsenic contamination is also contaminated to some extent by various media in the RCFS, including water, rice, insects, and grasses.

4.3. Characterization of Arsenic Enrichment in Rice and the Mechanism of Its Influence

In this study, we found that the arsenic content in different parts of rice increased with increasing soil arsenic concentration, and at the same contamination concentration, the arsenic content in different parts of rice was in the order of root > stem > brown rice. These results are consistent with previous studies [29] The inorganic arsenic content of brown rice in this study showed CF > RCFS > AWD, and during the experimental period, the RCFS and CF Eh ranged from −200 mv to −150 mv with pH around 8.3, while the AWD Eh was much higher than the RCFS and CF due to indirect irrigation, and the pH was stabilized at around 7.7 for the soil Eh. It has been shown that the bioavailability of arsenic increases dramatically when the pH increases above 7.4 to 7.5 or when the Eh drops below −200 mV [30], and that rice is more susceptible to arsenic contamination under the chemical environmental conditions that are created when rice paddies are flooded, which contributes to global food insecurity [31,32]. Therefore, AWD produces safer brown rice compared to RCFS and CF.

RCFS, compared to CF, crayfish aquaculture feeding, and the residual bait manure it produces, can lead to higher SOM content in RCFS than CF. Some studies suggest that the effects of organic matter are particularly complex [33,34]. Humic substances may inhibit arsenic release through As(III) immobilization [35]; SOM can catalyze phase and compositional transformations of Fe oxides; and under anaerobic conditions, SOM promotes reductive transformations of Fe oxides and accelerates the mobilization of Fe oxides bound to arsenic [36,37]. In addition, organic matter rich in carboxyl, amino, hydroxyl, phenolic, and sulfhydryl functional groups can immobilize arsenic via specific adsorption [38], thus reducing the bioavailability of arsenic. Therefore, RCFS yields safer brown rice compared to CF.

4.4. Overview of This Experiment

In previous studies on arsenic enrichment in rice or aquatic organisms, the approach has typically been field surveys or laboratory-constructed arsenic contamination models in planters (for rice) or aquaria (for fish or other aquatic organisms) [27]. Although the potting/aquarium model can accurately represent contamination levels, it cannot effectively reflect the accumulation of arsenic in rice or aquatic organisms in real environments due to the large differences between experimental environments and actual field environments. Field surveys are not precisely designed for contamination levels, and conditions—such as soil properties in different environments, weather (temperature, rainfall, and other factors), and planting/farming management techniques—are complex and variable. Therefore, it does not effectively reflect universal patterns. In this experiment, contamination was modeled and quantified to simulate arsenic levels in a small- to medium-sized test field. This experiment is a small-scale field experiment that not only accurately controls pollution levels but also maintains a high degree of similarity with the field environment. From a methodological perspective in pollution modeling, this experiment can overcome the shortcomings of the above two methods.

5. Conclusions

The inorganic arsenic content of brown rice in RCFS increases with increasing soil arsenic concentration, Y = 0.0117X + 0.0598 (R2 = 0.9600). Under the same soil arsenic concentration, the inorganic arsenic content of brown rice in the three modes showed a trend of CF > RCFS > AWD. According to (GB2762-2022 National Standard for Food Safety Limits of Pollutants in Food) standards for brown rice, the soil arsenic safety thresholds for RCFS, CF, and AWD were extrapolated to be 11.98 mg/kg, 9.24 mg/kg, and 26.48 mg/kg. The arsenic content in different tissues of crayfish increases with the increase in soil arsenic concentration. The relationship between the arsenic content in the abdominal muscle and the soil arsenic concentration is Y = 0.0085X + 0.0553 (R2 = 0.8588). According to the GB2762-2022 standard, the soil arsenic safety threshold for crayfish in RCFS was deduced to be 52.29 mg/kg. At the same soil arsenic concentration, arsenic levels in the hepatopancreas of crayfish were significantly higher than those in the abdominal muscle, and at 5 mg/kg, the hepatopancreas exceeded the carcinogenic risk of 10−4 for both adults and children, suggesting that the hepatopancreas poses a potential carcinogenic risk to humans. This study is the first to systematically illustrate the arsenic enrichment characteristics and influence mechanism of crayfish and rice in RCFS and to provide a basis for the safe production of RCFS.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fishes10120645/s1, Figure S1. Crayfish survival rate, specific growth rate, weight gain rate; Figure S2. Rice tissue arsenic content (A: RCFS; B: AWD; C: CF); Table S1. Rice agronomic traits.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.Z. and S.Z.; methodology, L.D.; software, T.L. and L.L.; validation, W.L., Y.Z. and Y.G.; formal analysis, D.L.; investigation, S.Y.; resources, L.D.; data curation, S.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, K.Z. and S.Z.; writing—review and editing, J.W.; visualization, D.W.; supervision, D.W. and Z.D.; project administration, Z.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32172998), Study and Demonstration on the Breeding of New Cobitidae Varieties and Standardized Aquaculture Techniques (2021YFYZ0015), the Yalong River Percocypris pingi Germplasm Characterization and Its Application in Artificial Propagation Project (000023-22XB0141), and the National Modern Agricultural Industry Technology System-Sichuan Innovation Team, China (SCCXTD-2025-15).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was approved by the Animal Care Advisory Committee of Sichuan Agricultural University (protocol code: SC2021019 and approval date: 28 May 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that this study received funding from Yalong River Hydropower Development Co., Ltd. The funder provided experimental materials and drafted the manuscript. The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Rahman, M.A.; Hasegawa, H.; Rahman, M.M.; Tasmin, A. Straighthead disease of rice (Oryza sativa L.) induced by arsenic toxicity. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2007, 62, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, W.R.; Reimer, K.J. Arsenic speciation in the environment. Chem. Rev. 1989, 89, 713–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Wang, Y. Hydrogeochemical processes in shallow Quaternary aquifers from the northern part of the Datong Basin, China. Appl. Geochem. 2004, 19, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Y.-J.; Jiang, S.-J. Application of HPLC–ICP–MS and HPLC–ESI–MS procedures for arsenic speciation in seaweeds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 2083–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guabloche, A.; Alvariño, L.; Acioly, T.M.S.; Viana, D.C.; Iannacone, J. Assessment of essential and potentially toxic elements in water and sediment and the tissues of Sciaena deliciosa (Tschudi, 1846) from Callao Bay, Peru. Toxics 2024, 12, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, K.S.S.; Acioly, T.M.S.; Nascimento, I.O.; Costa, F.N.; Corrêa, F.; Gagneten, A.M.; Viana, D.C. Biomonitoring of waters and Tambacu (Colossoma macropomum × Piaractus mesopotamicus) from the Amazônia Legal, Brazil. Water 2024, 16, 2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.-J.; Ma, J.F.; Meharg, A.A.; McGrath, S.P. Arsenic uptake and metabolism in plants. New Phytol. 2009, 181, 777–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 2762–2022; National Standard for Food Safety—Limits of Pollutants in Foods. National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China; State Administration for Market Regulation: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Granberg, E.M.; Hansen, R.; Selck, H. Relative importance of macrofaunal burrows for microbial mineralization of pyrene in marine sediments: Impact of macrofaunal species and organic matter quality. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2005, 288, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Albertson, L.K.; Sklar, L.S.; Cooper, S.D.; Cardinale, B.J. Aquatic macroinvertebrates stabilize gravel-bed sediment: A test using silk net-spinning caddisflies in semi-natural river channels. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0209087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki, S.S.; Usio, N.; Takamura, N.; Washitani, I. Effects of common carp on nutrient dynamics and littoral communities: Roles of excretion and bioturbation. Fundam. Appl. Limnol. 2007, 168, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Wang, D.; Xu, Z.; Liao, G.; Chen, D.; Huang, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhao, L.; Huang, H.; et al. Effects of cadmium pollution on the safety of rice and fish in rice–fish coculture. Environ. Int. 2020, 143, 105898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, J.G.; Naylor, D.V.; Fendorf, S.E. Arsenic sorption in phosphate-amended soils during flooding and aeration. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1999, 63, 1149–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hseu, Z.Y.; Chen, Z.S. Saturation, reduction, and redox morphology of seasonally flooded Alfisols in Taiwan. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1996, 60, 941–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehran, L.; Parvin, S.; Salim, S. Bioaccumulation of Metals in Pacific White-Leg Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) and Sediment in Shrimp Farms of Gwatr Bay, Iran: Effects of Culture Cycle and Diet. Thalass. Int. J. Mar. Sci. 2023, 39, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.; West, J.M.; Koch, I.; Reimer, K.J.; Snow, E.T. Arsenic speciation in freshwater crayfish, Cherax destructor Clark. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 2650–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedik, K.; Kongchum, M.; DeLaune, R.D.; Sonnier, J.J. Distribution of arsenic and other metals in crayfish tissues (Procambarus clarkii) under different production practices. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 574, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, A.; Malik, R.N. Heavy Metals in Eight Edible Fish Species from Two Polluted Tributaries (Aik and Palkhu) of the River Chenab, Pakistan. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2011, 143, 1524–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veettil, K.D.; Mohan, G.; Noushad, K.M.; Ganeshamurthy, R.; Kumar, T.T.A.; Balasubramanian, T. Determination of Metal Levels in Thirteen Fish Species from Lakshadweep Sea. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2012, 88, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achard, M.; Baudrimont, M.; Boudou, A.; Bourdineaud, J.P. Induction of a multixenobiotic resistance protein (MXR) in the Asiatic clam Corbicula fluminea after heavy metals exposure. Aquat. Toxicol. 2004, 67, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, S.M.; Rocha, E.; Mancera, J.M.; Fontaínhas-Fernandes, A.; Sousa, M. A stereological study of copper toxicity in gills of Oreochromis niloticus. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2009, 72, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berntssen, M.H.; Aspholm, O.Ø.; Hylland, K.; Bonga, S.E.W.; Lundebye, A.-K. Tissue metallothionein, apoptosis and cell proliferation responses in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) parr fed elevated dietary cadmium. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2001, 128, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lall, S.P.; Kaushik, S.J. Nutrition and metabolism of minerals in fish. Animals 2021, 11, 2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Culioli, J.; Calendini, S.; Mori, C.; Orsini, A. Arsenic accumulation in a freshwater fish living in a contaminated river of Corsica, France. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2009, 72, 1440–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Huang, L.; Wang, W. Biotransformation and detoxification of inorganic arsenic in a marine juvenile fish Terapon jarbua after waterborne and dietborne exposure. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 221, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenšová, R.; Čelechovská, O.; Doubravová, J.; Svobodová, Z. Concentrations of Metals in Tissues of Fish from the Věstonice Reservoir. Acta Vet. Brno 2010, 79, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subotić, S.; Jeftić, Ž.V.; Spasić, S.; Hegediš, A.; Krpo-Ćetković, J.; Lenhardt, M. Distribution and accumulation of elements (As, Cu, Fe, Hg, Mn, and Zn) in tissues of fish species from different trophic levels in the Danube River at the confluence with the Sava River (Serbia). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 5309–5317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanakumar, S.; Solaraj, G.; Mohanraj, R. Heavy metal partitioning in sediments and bioaccumulation in commercial fish species of three major reservoirs of river Cauvery delta region, India. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2015, 113, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.F.; Yamaji, N. Functions and transport of silicon in plants. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008, 65, 3049–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, K.; Xie, P.; Ji, H. The optimum pH and Eh for simultaneously minimizing bioavailable cadmium and arsenic contents in soils under the organic fertilizer application. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 711, 135229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Tang, Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Zhou, W.-X.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, F.-J. Water management impacts the soil microbial communities and total arsenic and methylated arsenicals in rice grains. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 247, 736–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.J.; McGrath, S.P.; Meharg, A.A. Arsenic as a Food Chain Contaminant: Mechanisms of Plant Uptake and Metabolism and Mitigation Strategies. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 535–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.; Wang, X.; Zheng, C.; Yan, L.; Li, L.; Huang, R.; Wang, H. Enhanced arsenic depletion by rice plant from flooded paddy soil with soluble organic fertilizer application. Chemosphere 2020, 252, 126521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, J.; Li, X.; Li, F.; Liu, T.; Young, L.Y.; Huang, W.; Sun, K.; Tong, H.; Hu, M. Humic Substances Facilitate Arsenic Reduction and Release in Flooded Paddy Soil. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 5034–5042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Yang, Y.; Williams, P.N.; Sun, H.; Chen, H.; Yang, D.; Shi, X.; Fu, R.; Luo, J. A Novel In Situ Method for Simultaneously and Selectively Measuring AsIII, SbIII, and SeIV in Freshwater and Soils. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 4576–4583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, W.; Ding, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, N.; Li, Y.C.; Gao, B.; Wang, B.; Wang, X. Biochar-supported zero-valent iron enhanced arsenic immobilization in a paddy soil: The role of soil organic matter. Biochar 2024, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, H.T.T.; Hyun, S.K.; Lee, H.; Jo, H.Y.; Chung, J.; Lee, S. Variable effects of soil organic matter on arsenic behavior in the vadose zone under different bulk densities. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 447, 130826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Khan, S.; Ibrahim, M.; Sun, T.-R.; Tang, J.-F.; Cotner, J.B.; Xu, Y.-Y. Biochars induced modification of dissolved organic matter (DOM) in soil and its impact on mobility and bioaccumulation of arsenic and cadmium. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 348, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).