Abstract

As an important component of the global fishery economy, the crab breeding and processing industry faces the dual challenges of sustainable development and technological upgrading. This paper first systematically analyzes the regional distribution and core biological characteristics of major global economic crab species, laying a foundation for the targeted design of processing technologies and equipment. Secondly, based on advances in crab processing technology, the industry is categorized into two systems: live crab processing and dead crab processing. Live crab processing has formed a full-chain technological system of “fishing–temporary rearing–depuration–grading–packaging”. Dead crab processing focuses on high-value utilization: high-pressure processing enhances the quality of crab meat; liquid nitrogen quick-freezing combined with modified atmosphere packaging extends shelf life; and biological fermentation and enzymatic hydrolysis facilitate the green extraction of chitin from crab shells. In terms of intelligent equipment application, sensor technology enables full coverage of aquaculture water quality monitoring, precise classification during processing, and vitality monitoring during transportation. Automation technology reduces labor costs, while fuzzy logic algorithms ensure the process stability of crab meat products. The integration of the Internet of Things (IoT) and big data analytics, combined with blockchain technology, enables full-link traceability of the “breeding–processing–transportation” chain. In the future, cross-domain technological integration and multi-equipment collaboration will be the key to promoting the sustainable development of the industry. Additionally, with the support of big data and artificial intelligence, precision management of breeding, processing, logistics, and other links will realize a more efficient and environmentally friendly crab industry model.

Keywords:

crab industry; intelligent equipment; processing technology; Internet of Things; big data analysis Key Contribution:

This paper systematically reviews the biological characteristics and industrial distribution of the world’s major economic crab species, providing biological and industrial background for the research and development of their processing technologies. Regarding processing technology, a systematic classification framework centered on “live crab processing” and “dead crab processing” was constructed, the key links from fishing to deep processing were clarified, and a clear flow chart was formed—all laying a structural foundation for technical optimization and equipment integration. This paper further reviews the application progress of intelligent technologies (including sensors, machine vision, and deep learning) in classification, recognition, monitoring, and traceability. The recognition accuracy and applicability of different algorithms are analyzed and evaluated, highlighting the driving role of interdisciplinary integration in industrial intelligence. Finally, this paper identifies current industrial challenges and outlines future development directions, thereby providing guiding value for industrial practice.

1. Introduction

As a core sector of the global fishery economy, the crab farming industry plays a key role in food supply, ecological balance, and international trade. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Asia’s total crab output exceeded 2 million tons in 2023, with China becoming the world’s largest producer, accounting for 45% of global production. Among these, Eriocheir sinensis output reached 913,000 tons, while the catch of marine crabs (e.g., Portunus pelagicus and Portunus trituberculatus) has remained stable above 563,000 tons [1]. Meanwhile, major producing countries such as the United Kingdom, Norway, Canada, and the United States have also established distinctive farming and fishing systems. However, amid growing consumer demand, increasing environmental pressure, and advances in intelligent technologies, the crab farming industry faces the dual challenges of sustainable development and technological upgrading.

From an industrial foundation perspective, the biological characteristics and ecological requirements of different crab species vary significantly. For instance, Eriocheir sinensis has a narrow salinity tolerance range, requires freshwater for growth and reproduction, and its diurnal and nocturnal habits necessitate precise regulation of water temperature and habitat conditions during the farming process [2]. In contrast, Portunus pelagicus adapts to the warm waters of the Indo-Western Pacific [3]. North American species, such as Callinectes sapidus [4] and Paralithodes camtschaticus [5], also exhibit unique growth patterns and aquaculture requirements due to variations in water temperature and salinity across their distribution ranges. Studying and analyzing the biological characteristics of different crab species serves as the foundation for optimizing aquaculture models.

In terms of technological evolution, the traditional aquaculture model faces the dual bottlenecks of efficiency and environmental protection. The harvesting, temporary rearing (i.e., holding tanks for short-term storage of live crabs before processing or sales), depuration, and sorting systems in live crab processing have greatly enhanced processing efficiency while ensuring the freshness and quality of crab products. This system accurately connects to the fresh retail and direct catering supply, fully responds to consumers’ core demands for product freshness and consistent specifications, and provides practical support for aquatic product processing technology to adapt to the needs of market. For example, the application of computer vision and deep learning algorithms has significantly improved the accuracy of sex identification for Eriocheir sinensis [6] and enabled real-time monitoring of molting status. The crab meat extraction technology in post-mortem crab processing (e.g., high-pressure processing, HPP), frozen preservation (the combination of liquid nitrogen quick-freezing and vacuum packaging), and by-product utilization (chitin extraction from crab shells via biological fermentation) [7] promote the industry’s upgrading toward a high-value-added orientation through interdisciplinary technological integration. Relevant processed products (such as canned crab meat and frozen crab products) are widely used in scenarios such as ready-to-eat foods and food industry ingredients, which meet the market’s core demands for product convenience and shelf life, and provide technical support for the high-value development of the aquatic product processing industry.

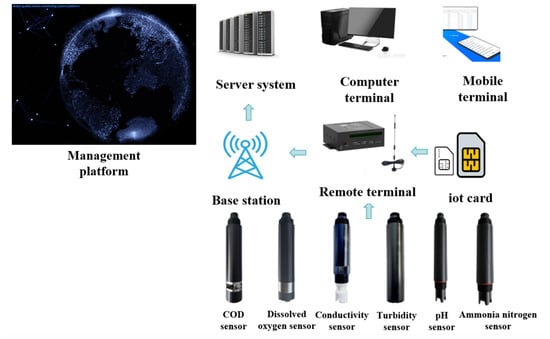

The application of intelligent equipment has become the core driving force for industrial transformation. Sensor technology enables real-time monitoring of aquaculture water quality and transportation environments. The integration of the Internet of Things (IoT)—particularly through sensors, data transmission, and management platforms tailored to crab aquaculture—facilitates full-link traceability of crabs from cultivation to sales. Through mining multi-dimensional data throughout the aquaculture process, big data analytics and cloud computing predict growth trends and disease risks, providing decision support for precision feeding and environmental regulation.

However, the industry currently faces numerous challenges: cannibalism and water quality deterioration in high-density temporary rearing, insufficient adaptability of automatic grading equipment to multiple crab species, mitigation of meat fiber damage caused by frozen preservation technology, and cost–benefit equilibrium in the resource utilization of crab shell waste. Additionally, abnormal water temperatures induced by climate change, restrictions on traditional fishing grounds imposed by ecological protection policies, and the upgrading of consumers’ demand for high-quality, sustainable products have compelled the transformation of aquaculture technology toward green and intelligent development.

The novelty of this review lies in three aspects: first, it establishes a direct connection between crab species’ biological characteristics and processing technology requirements, avoiding the disconnection between basic research and industrial application; second, it innovatively constructs a systematic classification system for crab processing technologies, clarifying the logical relationship between different processing routes and product value; third, it comprehensively combs the application of intelligent technologies across the entire industrial chain, highlighting the driving role of interdisciplinary integration (agricultural engineering, information technology, food science) in industrial upgrading.

This review is expected to provide a comprehensive theoretical reference for academic research in related fields, and offer practical technical paths for enterprises to optimize processing processes, develop intelligent equipment, and improve industrial competitiveness. Ultimately, it aims to promote the transformation of the crab industry toward precision management, resource efficiency, and environmental friendliness, realizing sustainable and high-quality development.

2. Main Economic Crab Species

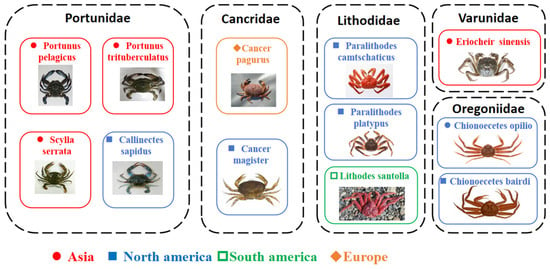

As a key component of marine biodiversity resources, crabs play a pivotal role in the global fishery economy and global ecosystem. Different crab taxa have formed a diverse economic value system due to their unique morphological traits, ecological adaptability, and distribution characteristics (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). This chapter focuses on crab taxa with significant commercial fishing and aquaculture value, systematically summarizes their taxonomic characteristics, ecological habits, and economic value, and lays a basic theoretical foundation for the development of relevant industries and resource conservation.

Figure 1.

Global distribution map of major economic crab species (key families: Portunidae, Varunidae, Cancridae, etc.) highlighting regional concentration in Asia, Europe, and North America.

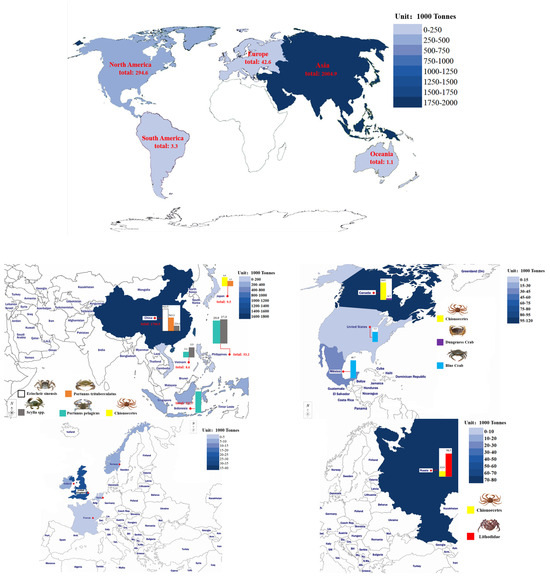

Figure 2.

World crab yield map.

According to data from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and fishery authorities of multiple countries, the global crab industry is characterized by regionalized harvests. The harvested and species distribution of crabs in the world’s major economies are presented in Figure 1.

As shown in Table 1, this study systematically synthesizes the ecological adaptation traits of economic crabs and their main sources of acquisition. Building on this, future research should integrate the aforementioned key biological parameters to conduct in-depth analysis of the relationships between economic crabs’ growth characteristics and environmental factors. Research findings in this direction are expected to enhance the utilization efficiency of crab resources, provide a scientific basis for formulating fishery management strategies, and offer important guidance for promoting the sustainable development of the crab aquaculture industry.

Table 1.

Optimal salinity, water temperature and main sources of acquisition of major economic crab species.

2.1. Asia

(1) Eriocheir sinensis

Eriocheir sinensis thrives in freshwater for growth and brackish water for reproduction, with optimal aquaculture conditions at 23–30 °C and low to moderate salinity [8]. Modern production is primarily through aquaculture, with wild capture now rare. These insights guide sustainable and high-quality mitten crab farming [9].

(2) Portunus pelagicus

Portunus pelagicus thrives at 30 ppt salinity and 30 °C [10], with estuarine and coastal habitats—especially those with mangroves and seagrass—being most suitable for growth and recruitment. While wild capture remains dominant, aquaculture is expanding to support sustainable production and reduce overfishing pressures.

(3) Portunus trituberculatus

Portunus trituberculatus grows best at 20–30 ppt salinity and 18–26 °C, with estuarine/coastal and pond-based polyculture systems providing optimal environments [11]. While wild capture persists, aquaculture is now the main source, supported by advances in environmental management and stock enhancement.

(4) Scylla serrata

Scylla serrata thrives at 20–30 ppt salinity and 25–32 °C, with mangrove and estuarine habitats providing optimal conditions [12]. While wild capture remains important, aquaculture is growing rapidly to meet demand and reduce pressure on natural stocks.

2.2. North America

(1) Callinectes sapidus

Callinectes sapidus thrives at 18–25 ppt salinity and 23–28 °C [13], occupying estuaries, lagoons, and tidal creeks. Wild capture remains the main acquisition method, with aquaculture still limited.

(2) Cancer magister

Cancer magister thrives at 25–32 ppt salinity and 10–15 °C, using estuaries and coastal waters for different life stages [14]. The fishery is sustained by wild capture, with aquaculture not yet commercially viable. Habitat quality and environmental stability are key for population health.

(3) Paralithodes camtschaticus

Red king crab requires high salinity (25–30 ppt) and cold water (3–10 °C optimal for larvae), inhabiting coastal and shelf areas with seasonal migrations [15]. The species is almost exclusively sourced from wild capture, with aquaculture not yet commercially viable. Environmental stability and sustainable management are crucial for healthy populations.

(4) Paralithodes platypus

Paralithodes platypus require cold (1–9 °C) [16], high-salinity (25–33 ppt) [17] marine environments and complex benthic habitats for juvenile survival. Wild capture is currently limited due to depleted stocks, while aquaculture is experimental and faces challenges with cannibalism and post-release survival. Habitat complexity and larval supply are key factors for population recovery and future stock enhancement.

(5) Chionoecetes opilio

Chionoecetes opilio thrives in cold, high-salinity marine environments (20–30 ppt, −1 °C to 4 °C) [18], inhabiting deep, soft-bottomed continental shelves. The species is almost exclusively sourced from wild capture fisheries, with aquaculture still experimental.

(6) Chionoecetes bairdi

Chionoecetes bairdi thrives in cold, high-salinity marine environments, with optimal juvenile growth at 4–9 °C [19] and a preference for fine sediments and complex habitats. The species is almost exclusively sourced from wild capture fisheries, with aquaculture still experimental.

2.3. Europe

Cancer paguris thrives in full-strength, temperate to cold marine waters (salinity 33–34 ppt, 9–15 °C) [20], inhabiting sandy or gravelly continental shelves. The species is exclusively wild-caught, with no aquaculture production. Its distribution and growth are shaped by temperature, salinity, and substrate, and sustainable management is crucial for fishery health.

2.4. South America

Lithodes santolla thrives in cold, fully marine waters (5–10 °C, ~33–34 ppt) [21,22], inhabiting subtidal to deep shelf environments. The species is almost exclusively wild-caught, with aquaculture still in development for stock enhancement.

3. Research Status of Crab Processing Technology

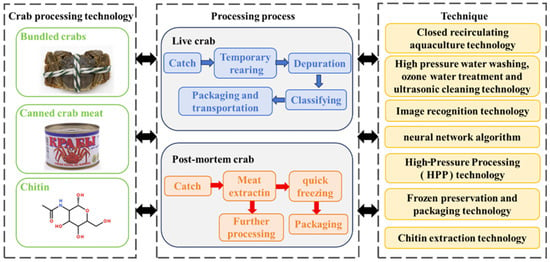

As a high-value aquatic product, crabs occupy a pivotal position in the global aquaculture and processing industry owing to their high nutritional value and significant economic benefits. Based on the status of the processed product, crab processing technologies are categorized into two types: live crab processing and post-mortem crab processing, as shown in Figure 3. In recent years, with the upgrading of consumer demands and the advancement of cold chain logistics, research into quality control, safety, efficiency, and automation in crab processing has been further advanced.

Figure 3.

Crab processing process flow chart.

3.1. Processing Technology of Live Crab

Live crab processing mainly involves processes such as harvesting, depuration, grading, and packaging. Its primary goal is to extend the survival period of crabs and maintain the quality of life of individuals during transportation and sales. Currently, live crab processing technology has achieved remarkable advancements, particularly in satisfying people’s demand for high-quality crab meat and enhancing consumer convenience. The key links in the processing chain—harvesting, depuration, grading, and packaging—are crucial for preserving the quality of live crabs and extending their shelf life.

3.1.1. Harvesting and Temporary Rearing Technology

Harvesting and temporary rearing technology serves as a critical initial step in crab processing, exerting a direct influence on subsequent processing quality, survival rate, and economic value. Based on distinct processing objectives, harvesting technology entails different goals and technical requirements for the processing routes of live crabs and post-mortem crabs. For live crabs, the focus is on minimal damage, high survival rate, and transport adaptability, whereas post-mortem crabs emphasize rapid cold chain transportation and inhibition of spoilage post-harvest.

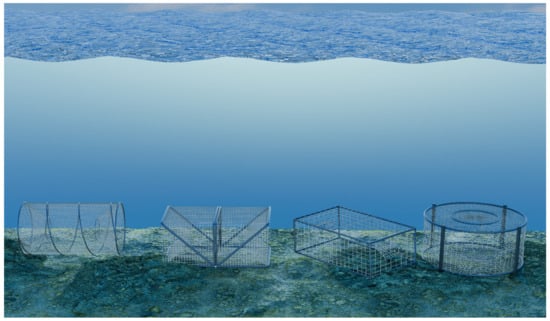

For crabs destined for live sales, harvesting operations must minimize stress responses and mechanical damage while ensuring the crabs’ integrity and vitality. Currently, widely adopted harvesting methods include gill nets, trap cages, small trawls, and manual collection, with their structural configurations illustrated in Figure 4. Trap cages are extensively used in offshore and inland waters due to their simple structure, high selectivity, and low environmental disturbance—particularly suitable for larger, more active crab species [23]. Studies have highlighted that the design of fishing gear has a significant impact on the capture efficiency of live crabs. For instance, Butcher et al. [24] investigated the effects of four different crab cage designs on the capture efficiency of Scylla serrata. Their findings revealed significant differences in capture efficiency among the designs; a rationally designed crab cage not only improves harvest performance but also effectively reduces damage during harvesting. These results provide important references for optimizing crab cage design and enhancing live crab harvesting efficiency.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of common live crab harvesting cages (trap cage, gill net cage, etc.) showing structural differences for optimizing capture efficiency and reducing mechanical damage.

Bergshoeff et al. [25] substantially improved the capture efficiency of rectangular crab cages through simple design modifications, and existing rectangular cages can be easily upgraded using this approach. To reduce the accidental capture of female Malaclemys terrapin, Roosenburg and Green [26] developed a bycatch reduction device and evaluated its effects on the size and catch quantity of Callinectes sapidus. Dawe et al. [27] found that trawls achieved the highest overall capture efficiency in soft muddy substrates, the lowest in coarse hard substrates, and intermediate efficiency in sandy substrates. Additionally, capture efficiency of trawls showed an upward trend with increasing male crab size.

The core objective of the temporary rearing stage is to alleviate stress responses induced by harvesting or transportation, stabilize crab metabolism, and improve survival rates. Modern temporary rearing technologies predominantly adopt closed recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS), enabling precise regulation of water quality by controlling parameters such as water temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, and pH [28]. A typical closed recirculating aquaculture system is depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Closed recirculating aquaculture system.

Furthermore, the stocking density of live crabs has a significant impact on survival rates [29]. Although high-density temporary rearing increases unit yield, it easily causes limb damage and water quality deterioration. Thus, rational control of stocking density is essential.

Live crab harvesting and temporary rearing technology is evolving toward high efficiency, intelligence, and sustainability. Technologies such as automatic monitoring, water quality management, and microbial control have significantly improved crab survival rates and product quality. Current research focuses on system optimization and technological innovation, with less attention paid to environmental risks, animal welfare, and long-term physiological effects during temporary rearing. Green, low-carbon, and sustainable management models require further exploration. In the future, multidisciplinary collaboration should be strengthened to promote technological innovation and green management practices.

3.1.2. Depuration Technology

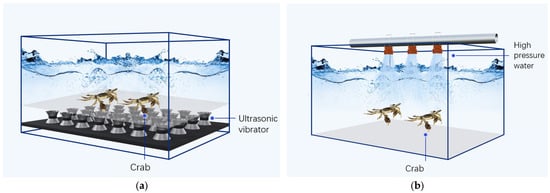

The primary purpose of live crab depuration is to remove sediment, organic matter, parasites, and bacteria adhered to the crab surface, thereby ensuring food safety. Common depuration methods include high-pressure water washing, ozonated water treatment, and ultrasonic depuration [30,31,32], as shown in Figure 6. Among these, high-pressure water washing is extensively adopted in small-scale processing due to its depuration speed and minimal mechanical damage. Ozonated water exhibits excellent sterilization and oxidation properties, which can effectively reduce the total number of surface bacteria without generating chemical residues. Ultrasonic depuration technology utilizes the cavitation effect of ultrasonic waves to more thoroughly remove harmful substances in crevices, enhance depuration quality while further improving depuration efficiency and food safety standards. Their advantages and disadvantages are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 6.

Different crab depuration methods: (a) high-pressure water washing technology; (b) ultrasonic depuration technology.

Table 2.

Comparison of advantages and disadvantages of different depuration methods.

Currently, live crab depuration technology is advancing rapidly toward automation, intelligence, and environmental sustainability. Emerging technologies such as high-efficiency mechanical equipment and ultrasonic systems have continuously driven industrial upgrading, significantly improving depuration efficiency, food safety, and environmental compatibility. However, current research mainly focuses on equipment structural innovation and physical depuration approaches, with equipment adaptability and large-scale industrial application still requiring further breakthroughs. Significant gaps remain in crab adaptability, automated integration, low-energy consumption technologies, and the industrialization of environmentally friendly materials.

3.1.3. Sorting and Packaging Transportation Technology

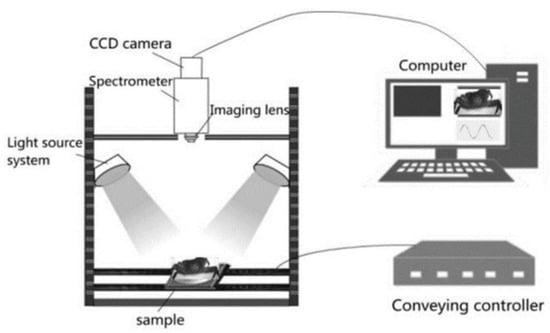

Live crab sorting is usually based on weight, sex, and appearance integrity. Some species, such as Eriocheir sinensis, also take crab roe content as an important reference parameter. Traditional manual sorting offers high flexibility but fails to meet the requirements of large-scale production due to low efficiency and large errors. Current automatic sorting systems are mainly weight-based [40,41]. With the development of computer technology, researchers have developed image recognition-based automatic sorting systems, whose composition is illustrated in Figure 7. These systems can achieve multi-parameter collaborative evaluation, distinguish crab sex, assess shelf life, and greatly enhance sorting accuracy [42].

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of image recognition-based crab sorting system (integrating CCD camera, spectrometer, and CNN algorithm) for multi-parameter grading (sex, weight, vitality).

As shown in Table 3, to further enhance sorting accuracy, researchers have conducted extensive in-depth studies in recent years based on image recognition technology and neural network algorithms. For instance, Wang et al. [43] proposed an improved BP neural network model based on a genetic algorithm, which can classify crab quality based on sex, fatness, weight, and shell color.

Table 3.

Machine learning for crab grading.

In order to improve the sex recognition accuracy of Chinese mitten crabs (Eriocheir sinensis) in low-light environments, Tian et al. [44] integrated the GAM algorithm into the YOLOv7 framework, enhancing the ability to identify sex-specific features. Cui et al. [6] proposed a novel crab sex classification method using a deep convolutional neural network (CNN) and employed dropout technology to suppress overfitting, achieving a classification accuracy of 98.90%. Chen et al. [45] developed a crab detection and sex classification method (GMNet-YOLOv4), which further reduced the parameter count while preserving accuracy. Compared with the original YOLOv4, the proposed method achieved a 2.82% accuracy improvement and an 82.24% reduction in the number of parameters.

In addition, Siripattanadilok and Siriborvornratanakul [46] proposed a machine olfaction system for determining the shelf life of whole live crabs. The stacked denoising autoencoder (SDAE) algorithm was used to extract effective features from sensor responses of the machine olfaction system. Verification experiments demonstrated that the olfaction-based recognition system achieved a recognition rate of up to 96.67%, providing further technical support for shelf life assessment of live crabs. Tang et al. [47] combined an improved YOLOv3 algorithm with an adaptive dark-channel defogging algorithm to achieve real-time detection of crab molting status in a single-crab basket culture system.

In terms of packaging and transportation, live crab packaging must prioritize maintaining survival, reducing stress responses, and enhancing transportation stability. Common packaging formats include single-crab or multi-crab bundled cartons, plastic boxes with ice packs, and breathable foam boxes. In recent years, some enterprises have begun adopting intelligent water treatment technologies. For example, during the transportation of European brown crabs (Cancer pagurus), electrochemical methods are used to remove ammonia and disinfect water, which significantly reduces the content of harmful compounds and improves crab survival rates [48]. For Lithodes santolla, burlap bags are used as moisture-retention packaging materials. Compared with Macrocystis pyrifera (giant kelp) packaging, burlap bags can effectively reduce water loss during long-distance transportation and enhance crab survival rates [49]. These advanced packaging and transportation technologies can increase profitability and reduce consumer costs by enabling longer-distance and higher-density transportation. Additionally, the pre-transport binding process—often secured with straw ropes, cotton ropes, or rubber bands—can significantly reduce the fighting and limb-abscission rates of live crabs during transportation.

Live crab grading, packaging, and transportation technology is advancing rapidly toward automation, intelligence, and environmental sustainability. Innovative technologies such as machine vision, deep learning, intelligent packaging, and cold chain logistics have continuously improved grading efficiency, transportation survival rates, and product quality. However, there is still room for breakthroughs in large-scale commercialization and standardization system construction. Current research mainly focuses on individual technological innovations in grading and packaging, lacking system integration and whole-process optimization. Intelligent packaging and real-time monitoring technologies have limited popularity in actual circulation. Cost control and environmental adaptability for large-scale commercial applications remain pressing issues that need to be addressed. In addition, soft-shell crabs represent a high-value niche product, facing unique packaging and transportation challenges due to their biological characteristics. Their soft and fragile exoskeletons are prone to damage from extrusion or friction, requiring independent partitioned packaging with flexible, moisture-retentive materials (e.g., breathable sponges or damp filter paper) instead of traditional binding methods to avoid exoskeleton breakage.

3.2. Processing Technology of Dead Crab

Post-mortem crab processing primarily involves shelling, segmentation, quick-freezing, and deep processing carried out within a specified timeframe after the crab’s death. These processes aim to maximize the utilization of crab meat while ensuring food safety and quality. Shelling involves separating the carapace from the crab meat, typically requiring professional shelling equipment or manual labor to preserve the integrity of the crab meat, as illustrated in Figure 8. Segmentation entails cutting the shelled crab meat into different parts—such as crab legs, chelipeds, and crab bodies—to cater to diverse consumer demands. Quick-freezing involves rapidly freezing heat-treated crab meat to a low-temperature state, which inhibits microbial growth and enzymatic activity, thereby further extending the product’s shelf life. This technology typically employs liquid nitrogen or mechanical refrigeration equipment to ensure the crab meat achieves the required freezing temperature within a short period. Deep processing involves further utilizing crab shells, such as for the production of chitin and chitosan. These products not only enhance crab resource utilization but also substantially increase added value.

Figure 8.

Extraction of crab meat.

3.2.1. Crab Meat Extraction Technology

Crab meat extraction technology is one of the most common processing methods in post-mortem crab processing. This technology primarily involves efficiently separating crab meat from crab shells through a series of mechanical means. First, post-mortem crabs undergo preliminary depuration to remove impurities and excess moisture. Then, crab meat is completely separated from the shells via mechanical extrusion or centrifugation. After further purification, the extracted crab meat can be used for subsequent processes such as freezing preservation and deep processing. The advantages of crab meat extraction technology include efficient large-scale processing of crabs, enhanced crab meat yield and resource utilization, as well as guaranteed product quality and safety.

To improve crab meat extraction efficiency, scholars at home and abroad have conducted extensive research and exploration. Wang et al. [50] developed a blue crab (Callinectes sapidus) cheliped detection system based on a convolutional neural network, providing an advanced intelligent device for automated crab processing. Lian et al. [51] explored a method for producing high-value-added claw meat products using high-pressure processing (HPP) on large-scale industrial equipment, with European brown crabs (Cancer pagurus) as raw material. They compared and evaluated the quality attributes of crab meat extracted from pressurized or heat-treated samples, determining the optimal treatment protocol.

Currently, crab meat extraction technology is continuously evolving toward high efficiency, automation, environmental sustainability, and intelligence. Multiple technologies—including high-pressure treatment, mechanized separation, and green extraction —have synergistically promoted the high-value utilization of crab meat and its by-products. Although significant progress has been made in this field, research gaps and room for improvement remain in process standardization, equipment intelligence, industrialization of green extraction, preservation of flavor and nutrition, and high-value utilization of crab shell by-products.

3.2.2. Frozen Preservation and Packaging Technology

After crabs die, endogenous proteases and tissue microorganisms are prone to causing autolysis and spoilage, while low-temperature treatment can significantly inhibit tissue degradation and delay spoilage [52]. Therefore, in the pre-processing stage of post-mortem crab processing, harvested crabs are typically rapidly chilled to preserve the freshness and quality of the meat, as illustrated in Figure 9. Low-temperature treatment can not only effectively alleviate the autolysis and spoilage of crab meat but also lay a solid foundation for subsequent thermal processing [53]. In addition, low-temperature treatment can preserve the original taste and flavor of crab meat to a certain extent [54], making the final processed crab products more flavorful.

Figure 9.

Crab freezing and packaging.

For the frozen preservation of crab meat, low-temperature freezing combined with vacuum packaging technology can effectively prevent lipid oxidation and ice crystal damage. Emerging freezing methods, such as liquid nitrogen quick-freezing and compressed air quick-freezing, are increasingly adopted to extend the product shelf life and enhance tissue structure stability. To improve the quality of frozen crab meat, scholars worldwide have conducted extensive research. For instance, Lorentzen et al. [55] evaluated weight changes in mildly cooked snow crabs (Chionoecetes opilio) during frozen storage and thawing, as well as drip loss and melanosis during cold storage. The results indicated that to minimize melanosis, crab meat should be frozen in salt water and thawed in water. Subramanian [56] performed a biochemical analysis of frozen crab products, finding that with prolonged storage (up to 120 days), the contents of total volatile basic nitrogen (TVB-N), trimethylamine (TMA), thiobarbituric acid (TBA), and free fatty acids (FFAs) in frozen crab products increased significantly. Webb et al. [53] compared changes in trimethylamine (TMA), total volatile basic nitrogen (TVB-N), and pH value of blue crab (Callinectes sapidus) meat stored at −18 °C and −30 °C for 8 months, concluding that the preservation effect at −18 °C was unsatisfactory.

To further extend the shelf life of crab meat, experts and scholars globally have conducted in-depth research on crab meat packaging technology. Dima et al. [57] used the finite element method to simulate heat transfer during the pasteurization of bagged crab meat products. The mathematical model was experimentally validated to determine the pasteurization time required for process system design. Gates et al. [58] compared the storage of crab meat in steel cans, aluminum cans, and plastic cans. The results showed that crab meat packaged in plastic and aluminum cans had better flavor and a longer shelf life compared to that in steel cans. Sun et al. [59] studied the effect of combined micro-freezing and modified atmosphere packaging (MAP) on the quality of Portunus trituberculatus during storage, finding that micro-freezing combined with 60% CO2 MAP extended the shelf life by 15–20 days. Tyler et al. [60] compared the total bacterial count of crab meat stored at 4 °C in traditional food-grade polyethylene snap-lid containers and trays sealed with film, providing a reference for crab meat preservation.

Overall, crab meat frozen preservation and packaging technology has gradually evolved from traditional low-temperature freezing and conventional plastic packaging toward diversification, intelligence, and environmental sustainability. However, different crab species, body parts, and processing links exhibit significant differences in sensitivity to process parameters, which require targeted optimization. Additionally, some studies have focused on the effects of freezing and packaging on heavy metal migration (e.g., cadmium) and food safety, indicating the need to strengthen whole-process quality control [61].

3.2.3. Deep Processing Technology

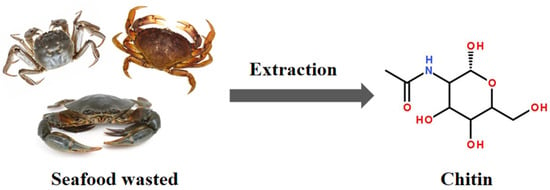

With the development of the crab processing industry, a large quantity of crab shells are discarded as waste, which not only results in resource waste but also imposes environmental pressure. However, crab shells are rich in valuable components such as chitin and chitosan, which possess biological activities including antibacterial, anticancer, and moisturizing properties, and are widely applied in multiple fields such as agriculture, industry, and medicine [62], as illustrated in Figure 10. Therefore, how to effectively utilize these wastes and achieve comprehensive utilization of crab resources has become a pressing issue to be addressed in the crab processing industry. Numerous experts and scholars have conducted extensive research, adopting chemical methods, biological fermentation, and enzymatic hydrolysis to realize the comprehensive utilization of crab shells.

Figure 10.

Extraction of chitin.

Chemical methods utilize chemical reagents to treat crab shells for chitin production. This method typically involves alkali treatment and acid treatment. A series of chemical reactions effectively remove inorganic salts and proteins from crab shells, yielding high-purity chitin. However, the use of chemical reagents may cause certain environmental pollution.

For instance, Zhang et al. [62] treated raw crab shells with hydrochloric acid under various conditions, investigating the desalination and deproteinization effects of different hydrochloric acid concentrations on raw and desalted crab shells. Their results laid the foundation for chemical chitin production. Gîjiu et al. [63] studied and optimized chitin extraction from crab shells, determining the optimal factor combination by adjusting NaOH concentration and temperature during deproteinization, HCl concentration during desalination, and the number of acid treatments.

To mitigate the environmental impact of chemical reagents, experts and scholars have focused on chitin production via biological fermentation processes. Hajji et al. [64] utilized protease-producing Bacillus to ferment crab shell waste, producing chitin and fermented crab supernatant. Jung et al. [65] co-fermented Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. tolerans KCTC-3074 and Erratia marcescens FS-3, achieving effective degradation of crab shell waste and chitin extraction.

Enzymatic hydrolysis processes can also convert crab shells into high-value-added products. For example, Castro et al. [66] extracted chitin via lactic acid fermentation, inoculating Lactobacillus plantarum isolated from coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) into crab shell substrates to study the effect of fermentation conditions on chitin extraction. Hamdi et al. [67] utilized endogenous alkaline proteases from fish to deproteinize crab and shrimp wastes, offering a potential alternative method for chitosan production.

Currently, crab shell chitin extraction technology is transitioning from traditional chemical methods to green and sustainable processes. Emerging technologies such as enzymatic hydrolysis and biological fermentation have significantly reduced environmental pollution and energy consumption while improving product purity, molecular weight, and functionality. However, current research mainly focuses on laboratory-scale or small-batch trials, with further breakthroughs needed in industrial scaling-up, cost control, and solvent recovery. Additionally, research on process suitability for different crab species/parts remains inadequate.

4. Intelligent Equipment

4.1. Sensor Technology

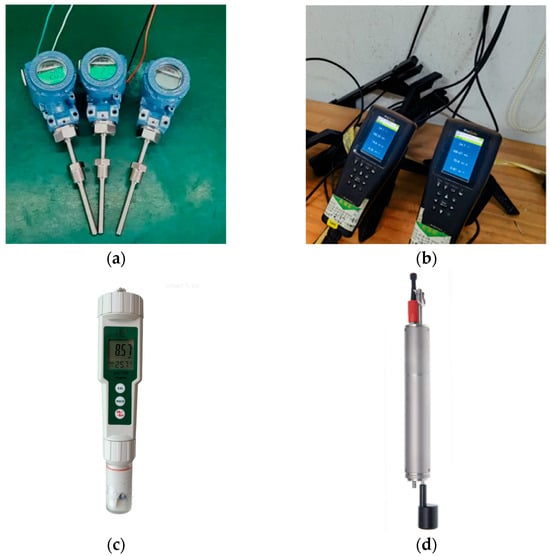

Sensors have become increasingly widely used in crab breeding, processing, and transportation, greatly enhancing the intelligence, automation, and economic benefits of the crab industry. Sensor technology enables real-time monitoring and intelligent management of key links such as water quality, crab viability, and processing precision, effectively reducing mortality rates, improving product quality, and optimizing supply chain efficiency [68], with its advantages and effects summarized in Table 4. For instance, during breeding, the water quality sensor illustrated in Figure 11 can monitor water temperature, dissolved oxygen, and pH in real time, ensuring crabs live in an optimal environment and thereby improving their growth rate and health status [69,70]. In processing, sensors can accurately measure crab weight, size, and appearance, facilitating automatic grading and packaging while reducing manual errors and time costs [6,42,43,44,45]. Additionally, during transportation, sensors can monitor temperature and humidity to ensure crabs reach their destination in optimal condition, further enhancing product market competitiveness [71].

Table 4.

Sensor technology advantages and effectiveness.

Figure 11.

Water quality monitoring sensor: (a) Temperature sensor; (b) Dissolved oxygen sensor; (c) PH sensor; (d) Salinity sensor.

In summary, sensor technology has deeply empowered the entire industrial chain of crab breeding, processing, and transportation, significantly improving production efficiency, product quality, and supply chain intelligence. Multi-parameter sensor networks exhibit excellent performance in water quality monitoring, automatic grading, and transportation and storage. However, research gaps remain in the development of low-cost, high-reliability sensors and whole-process intelligent decision-making. In the future, interdisciplinary technology integration and system optimization will be key directions to drive the intelligent upgrading of the crab industry.

4.2. Intelligent Technique

Intelligent technologies have been widely applied in crab breeding, processing, and transportation, significantly improving production efficiency, product quality, and management intelligence. Automation systems enable precise breeding management, intelligent processing, and efficient transportation, reducing labor costs and enhancing the overall efficiency of the crab industry—with the applications and effects of automation technologies summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Application and Effect of Automation Technology.

In the crab breeding process, automatic feeding equipment can accurately feed crabs according to their weight and growth stage, avoiding feed waste and water quality deterioration. Equipped with GPS navigation, it realizes uniform feeding across the entire pond [72,73,74]. The automatic sampling system based on information and communication technology (ICT) can real-time monitor crab growth, reducing manual operations and improving management efficiency and economic benefits [75]. The application of automatic aquatic plant grooming machines can efficiently clear aquatic plants in ponds, optimize the crab growth environment, and reduce the risk of crab injury [76].

In the processing link, the automatic control system integrates high-precision sensors and fuzzy logic algorithms to ensure the stability of process parameters in the production of crab meat products (e.g., crab sticks), improving product quality and reducing defective products [77]. In terms of transportation and management automation, the closed automatic rearing system facilitates the control of environmental variables, density management, and automatic monitoring, making it suitable for large-scale production and centralized management before transportation [78].

Robotic technology has also been gradually applied in the crab breeding, processing, and transportation industries. Its primary purpose is to improve automation, reduce labor costs, and address challenges posed by complex environments and product forms. Currently, robots have achieved remarkable progress in crab processing and amphibious operations, while their application in breeding and transportation is still in the exploration and platform development stage. For example, for crabs with complex surfaces (e.g., fully spined species), a robotic system based on 3D point cloud segmentation can automatically identify and remove crab spines, significantly improving processing efficiency and safety while reducing the difficulty of manual operations [79]. Through the integration of 2D and 3D visual information, robots can process crabs with complex shapes more accurately to adapt to dynamic processing needs [80].

4.3. Internet of Things and Big Data Analysis Technology

The Internet of Things (IoT) and big data technologies are revolutionizing the food processing and transportation industry through real-time monitoring, enhanced traceability mechanisms, and improved quality control. Their application optimizes production processes, ensures food safety, reduces waste, and delivers unprecedented transparency across the entire food supply chain. Particularly in crab breeding, processing, and transportation, IoT integration has significantly advanced industrial intelligence, transparency, and efficiency, with technical effects summarized in Table 6. As illustrated in Figure 12, IoT enables optimized whole-process management and quality control of crab breeding, processing, and transportation via real-time data acquisition and intelligent monitoring.

Figure 12.

Application of Internet of Things Technology.

In the breeding and processing stages, Pitakphongmetha et al. [69] achieved real-time monitoring of the aquaculture environment using water quality, locomotion, and feeding sensors. This improved the survival rate and production efficiency of high-value crabs (e.g., soft-shell crabs) while enabling precise and intelligent crab farming management. Tian and Jiang [81] realized full-link information traceability of crabs from breeding and processing to sales by integrating IoT with blockchain technology, which enhances brand trust while ensuring the authenticity and immutability of product information.

Rahmat et al. [82] developed an IoT-based water quality monitoring system incorporating temperature, humidity, pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), and other sensors, enabling real-time data display and cloud transmission.

Revathi et al. [83] utilized an IoT-based water quality monitoring system to achieve automatic real-time tracking and analysis of parameters such as pH, temperature, alkalinity, and nitrate in the aquaculture environment. This significantly improved the sustainability and efficiency of crab farming, thereby boosting productivity and profitability.

Table 6.

Technical Advantages and Effectiveness.

Table 6.

Technical Advantages and Effectiveness.

| The Role and Effectiveness of IoT Technology | Related References | |

|---|---|---|

| Breeding and processing | Real-time environmental monitoring, intelligent feeding, improved survival rate, full link traceability | [69,81] |

| Transport and circulation | Vitality monitoring, intelligent early warning, reducing loss and improving economic benefits | [71,84] |

| Quality traceability and supervision | Information transparency, enhance brand trust | [81,84] |

In transportation and quality traceability, Yu et al. [84] implemented whole-process quality traceability for cross-regional transportation of crab larvae via an IoT system. With a 100% traceability rate for crab larvae, this initiative elevated the standardization and management level of the industry. Zhang et al. [71] employed temperature, humidity, oxygen, and other sensors, combined with information fusion and intelligent algorithms, to dynamically monitor the vitality of live crabs during transportation. This greatly improved the accuracy of live crab vitality prediction and enhanced the economic efficiency of the supply chain. Jia et al. [85] developed a low-cost, high-contrast, and fast-response fluorescent marker for visual monitoring of the freshness of shrimp and crabs.

IoT and big data analytics have demonstrated substantial application value in crab breeding, processing, and transportation, advancing industrial intelligence, automation, and supply chain transparency. However, current research primarily focuses on individual links or local systems, lacking systematic research on the integration of the entire industrial chain and large-scale cross-regional applications. Research on data security, privacy protection, standardization, and long-term economic benefit evaluation remains relatively underdeveloped. In the future, it is necessary to strengthen the formulation of industry standards and conduct large-scale industrial-level verification.

4.4. Artificial Intelligence Technology

Artificial Intelligence (AI) technology, especially deep learning and computer vision, is becoming a core tool for crab farming density management, precision feeding, and health status monitoring. Through video analysis, object detection, and feature extraction, AI enables automatic detection and statistics of crab quantity and distribution. This further allows intelligent adjustment of feeding amounts and farming density, as well as real-time monitoring of crab behavior and health indicators, ultimately improving farming efficiency and reducing resource waste.

To reduce cannibalism, maintain water quality by optimizing stocking density, and improve the cost-effectiveness of aquaculture management, relevant research teams have carried out a number of technological explorations in the intelligent detection of crab aquaculture. Zakiyabarsi et al. [86] conducted a performance evaluation of two detection models, YOLOX and YOLOv9, to meet the demand for automatic identification of crab larvae in aquaculture environments, the results show that the YOLOv9 model has better detection capabilities, achieving a target detection rate of 93%, this model is conducive to establishing a sustainable crab aquaculture management system and provides technical support for long-term ecological and economic benefits. To address the challenges posed by low-illumination underwater environments to detection tasks, Sun et al. [87] proposed an underwater image enhancement method that integrates two-step color correction and improved dark channel prior. This method can effectively improve image quality, thereby constructing a clear distribution map of underwater river crabs and providing a basis for the scientific regulation of aquaculture environments. Cao et al. [88] designed an instance segmentation network (JDSNet), which can realize real-time detection and accurate segmentation of underwater unstructured live crabs and support biomass statistics. This method is of great value for promoting the application of precise feeding by automatic feeding boats.

Reducing feed waste plays a key role in improving the economic benefits of aquaculture. To enhance feed utilization efficiency, Hu et al. [89] proposed a visual detection algorithm based on improved YOLOv3 and Mask RCNN. This algorithm achieves an overall precision of 96.5% and a recall rate of 97%, enabling effective identification of residual feed and thus reducing feed waste. Ricohermoso et al. [90] developed an integrated IoT-based water quality monitoring and automatic feeding system for indoor mud crab aquaculture. This system continuously monitors key water quality parameters such as pH, salinity, temperature, and water level, and combines with an automatic feeding mechanism to realize refined aquaculture management.

In the research on intelligent management of aquaculture, behavior recognition and health status inference are important directions for achieving precise monitoring. Deep learning-based methods can effectively identify various behavioral patterns of aquaculture subjects, including feeding, hypoxic stress, low-temperature adaptation, and startle response [91]. Through the automatic recognition and analysis of behavioral patterns, abnormal states of individuals or groups can be detected at an early stage, thereby enabling timely early warning of health risks and environmental stress. This technology provides data support for disease prevention and health management during the aquaculture process, and helps promote the development of aquaculture management towards intelligence and refinement [92].

The above work has advanced the automated and precise management of crab aquaculture from different perspectives and provided a feasible technical path for building an efficient and sustainable aquaculture system.

5. The Future Development Direction

The automation and intelligence of processing and transportation links are an inevitable trend in the development of the crab aquaculture industry, as well as a key path to achieving efficient and sustainable development of aquaculture. This paper conducts a comprehensive review and analysis of the application status of major economic crab species, processing technologies, and intelligent equipment worldwide. It summarizes the intelligent technologies required for processing live and dead crabs, covering specific links such as depuration and temporary rearing, grading, packaging and transportation, freezing and preservation, and by-product processing. Meanwhile, this paper also explores the integrated innovation direction of “bioengineering + processing technology”, including optimizing the crab meat extraction process using enzyme engineering technology to reduce damage to meat fibers, and developing industrial strains for the biological fermentation of crab shells to improve the extraction rate of chitin. In addition, the paper elaborates on the technical requirements for intelligent equipment and focuses on discussing the application of the Internet of Things (IoT) technology. For the future development of the crab aquaculture industry, priority should be given to improving the stability and reliability of intelligent equipment, ensuring its stable operation even in harsh environments, thereby enhancing the efficiency and safety of the entire process of crab aquaculture, processing, and transportation. At the same time, it is necessary to strengthen the R&D and innovation of intelligent equipment, continuously adopt new technologies, new materials, and new processes to improve the intelligence level and environmental adaptability of the equipment.

Furthermore, efforts should be made to strengthen the data collection and analysis work throughout the entire chain of crab aquaculture, processing, and transportation. It is essential to promote the scenario-based application of “AI + big data” in precision aquaculture, establish growth models for different crab species such as Portunus trituberculatus (three-spot swimming crab) and snow crabs, and improve feed utilization efficiency through the dynamic matching of feeding amount and water quality parameters. Simultaneously, it is important to deepen the full-chain traceability system of the IoT, realize the immutability and traceability of data at all nodes of “aquaculture—processing—transportation”, and meet the quality traceability needs of the high-end market. By using big data and artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to optimize aquaculture management, processing techniques, and logistics systems, the precision management and efficient operation of the crab industry can be achieved. Through the above measures, the transformation and upgrading of the crab aquaculture industry will be promoted, and the industrial competitiveness and sustainable development capacity will be enhanced.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.T. and X.C.; methodology, Z.Q.; software, Z.Q.; validation, Z.Q., C.T. and X.C.; formal analysis, Z.Q.; investigation, C.T.; resources, Z.X. and J.C.; data curation, Z.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Q. and Z.X.; writing—review and editing, Z.X.; visualization, X.H.; supervision, X.C.; project administration, X.C.; funding acquisition, X.C. and J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Modern agricultural industrial technology system in China (grant number No. CARS-48), Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund, CAFS (grant number No. 2023TD67), and Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund, ECSFR, CAFS (grant number No. 2025YJ03).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024–Blue Transformation in Action; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Q.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, T.; Li, Z.; Liu, J. Effects of water temperature on growth, feeding and molting of juvenile Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis. Aquaculture 2017, 468, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryars, S.R.; Havenhand, J.N. Temporal and spatial distribution and abundance of blue swimmer crab (Portunus pelagicus) larvae in a temperate gulf. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2004, 55, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancinelli, G.; Chainho, P.; Cilenti, L.; Falco, S.; Kapiris, K.; Katselis, G.; Ribeiro, F. The Atlantic blue crab Callinectes sapidus in southern European coastal waters: Distribution, impact and prospective invasion management strategies. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 119, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falk-Petersen, J.; Renaud, P.; Anisimova, N. Establishment and ecosystem effects of the alien invasive red king crab (Paralithodes camtschaticus) in the Barents Sea–A review. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2011, 68, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Pan, T.; Chen, S.; Zou, X. A gender classification method for Chinese mitten crab using deep convolutional neural network. Multimedia Tools Appl. 2020, 79, 7669–7684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yu, Y.; Chu, D.; Zhu, S.; Liu, Q.; Yin, H. Efficient and eco-friendly chitin production from crab shells using novel deep eutectic solvents. J. Polym. Environ. 2024, 32, 6070–6079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.; Choi, T.; Kim, C. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis of Eriocheir sinensis from Wild Habitats in Han River, Korea. Life 2022, 12, 2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Peng, J.; Chen, J.; Zhao, Y.; Ding, Y.; Dai, J.; Hu, Z.; Huang, T.; Dong, M.; Xu, Z. Effect of Water Area and Waterweed Coverage on the Growth of Pond-Reared Eriocheir sinensis. Fishes 2022, 7, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juahir, J. Aquaculture Management of Blue Swimming Crab (Portunus pelagicus) in Boncong Bancar Marine Farming Facility, Tuban Regency, East Java Province, Indonesia. Aquat. Life Sci. 2024, 1, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Wang, L.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Lv, J.; Liu, P.; Li, J. Characterization of p53 from the Marine Crab Portunus trituberculatus and Its Functions Under Low Salinity Conditions. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 724693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddiwan; Dahril, T.; Adriman; Budijono; Efawani; Harjoyudanto, Y. Study of Growth and Survival of Mud Crab (Scylla serrata, Forskal) with Different Salinity Levels in culture media. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Pekanbaru, Indonesia, 5–16 September 2021; Volume 934. [Google Scholar]

- Marchessaux, G.; Barré, N.; Mauclert, V.; Lombardini, K.; Durieux, E.D.H.; Veyssiere, D.; Filippi, J.J.; Bracconi, J.; Aiello, A.; Garrido, M. Salinity tolerance of the invasive blue crab Callinectes sapidus: From global to local, a new tool for implementing management strategy. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, P. Culture Methods and Effects of Temperature and Salinity on Survival and Growth of Dungeness Crab (Cancer magister) Larvae in the Laboratory. Wsq Women’s Stud. Q. 1969, 26, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirley, T.; Shirley, S. Temperature and salinity tolerances and preferences of red king crab larvae. Mar. Behav. Physiol. 1989, 16, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, C.; Eckert, G.; Stoner, A. Influence of temperature and congener presence on habitat preference and fish predation in blue ( Paralithodes platypus Brandt, 1850) and red (P. camtschaticus Tilesius, 1815) king crabs (Anomura: Lithodidae). J. Crustac. Biol. 2016, 36, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, B.; Long, W.; Buckel, J. Inter-Cohort Cannibalism of Early Benthic Phase Blue King Crabs (Paralithodes platypus): Alternate Foraging Strategies in Different Habitats Lead to Different Functional Responses. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, D.; Munro, J.; Dutil, J. Temperature and salinity tolerance of the soft-shell and hard-shell male snow crab, Chionoecetes opilio. Aquaculture 1994, 122, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryer, C.; Ottmar, M.; Spencer, M.; Anderson, J.D.; Cooper, D. Temperature-Dependent Growth of Early Juvenile Southern Tanner Crab Chionoecetes bairdi: Implications for Cold Pool Effects and Climate Change in the Southeastern Bering Sea. J. Shellfish. Res. 2016, 35, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteley, N.M.; Suckling, C.C.; Ciotti, B.J.; Brown, J.; McCarthy, I.D.; Gimenez, L.; Hauton, C. Sensitivity to near-future CO2 conditions in marine crabs depends on their compensatory capacities for salinity change. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacristán, H.; Di Salvatore, P.; Fernández-Giménez, A.; Lovrich, G. Effects of starvation and stocking density on the physiology of the male of the southern king crab Lithodes santolla. Fish. Res. 2019, 218, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacristán, H.; Mufari, J.; Lorenzo, R.; Boy, C.; Lovrich, G. Ontogenetic changes in energetic reserves, digestive enzymes, amino acid and energy content of Lithodes santolla (Anomura: Lithodidae): Baseline for culture. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.J. Design criteria for crab traps. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 1980, 39, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, P.A.; Leland, J.C.; Broadhurst, M.K.; Paterson, B.D.; Mayer, D.G. Giant mud crab (Scylla serrata): Relative efficiencies of common baited traps and impacts on discards. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2012, 69, 1511–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergshoeff, J.A.; McKenzie, C.H.; Favaro, B. Improving the efficiency of the Fukui trap as a capture tool for the invasive European green crab (Carcinus maenas ) in Newfoundland, Canada. PeerJ 2019, 7, e6308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roosenburg, W.M.; Green, J.P. Impact of a Bycatch Reduction Device on Diamondback Terrapin and Blue Crab Capture in Crab Pots. Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 882–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawe, E.G.; Walsh, S.J.; Hynick, E.M. Capture efficiency of a multi-species survey trawl for Snow Crab (Chionoecetes opilio) in the Newfoundland region. Fish. Res. 2010, 101, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averina, J.M.; Kaliakina, G.E.; Zhukov, D.Y.; Kurbatov, A.Y.; Shumova, V.S. Development and design of a closed water use cycle. In Proceedings of the International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference: SGEM, Albena, Bulgaria, 28 June–6 July 2019; Volume 19, pp. 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Sneddon, L.U.; Huntingford, F.A.; Taylor, A.C. Impact of an ecological factor on the costs of resource acquisition: Fighting and metabolic physiology of crabs. Funct. Ecol. 1998, 12, 808–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, H.; Taylor, J.H.; Hall, K.E.; Holah, J.T. Effectiveness of cleaning techniques used in the food industry in terms of the removal of bacterial biofilms. J. Appl. Microbiol. 1999, 87, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, C.; Zahn, S.; Rost, F.; Zahn, P.; Jaros, D.; Rohm, H. Physical methods for cleaning and disinfection of surfaces. Food Eng. Rev. 2011, 3, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goode, K.R.; Asteriadou, K.; Robbins, P.T.; Fryer, P.J. Fouling and cleaning studies in the food and beverage industry classified by cleaning type. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2013, 12, 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucchetti, G.; Bonvini, B.; Francolino, S.; Neviani, E.; Carminati, D. Effect of washing with a high pressure water spray on removal of Listeria innocua from Gorgonzola cheese rind. Food Control. 2008, 19, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donoghue, E.M.; Somerfield, S.; McLachlan, A.; Olsson, S.; Woolf, A. High-pressure water washing and continuous high humidity during storage and shelf conditions prolongs quality of red capsicums (Capsicum annuum L.). Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013, 81, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, A.; Llorca, I.; Canut, A. Use of ozone in food industries for reducing the environmental impact of cleaning and disinfection activities. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 18, S29–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado-Alameda, E.; Garcia-Roman, M.; Altmajer-Vaz, D.; Jiménez-Pérez, J.L. Assessment of the use of ozone for cleaning fatty soils in the food industry. J. Food Eng. 2012, 110, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oulahal Lagsir, N.; Martial Gros, A.; Boistier, E.; Blum, L.J.; Bonneau, M. The development of an ultrasonic apparatus for the non-invasive and repeatable removal of fouling in food processing equipment. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2000, 30, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escrig, J.; Woolley, E.; Simeone, A.; Watson, N.J. Monitoring the cleaning of food fouling in pipes using ultrasonic measurements and machine learning. Food Control. 2020, 116, 107309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Sarpong, F.; Zhou, C. Use of ultrasonic cleaning technology in the whole process of fruit and vegetable processing. Foods 2022, 11, 2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, N.N.; Samuel, D.; Grewal, M.K.; Manjunatha, M. Development of orange grading machine on weight basis. J. Agric. Eng. 2014, 51, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunathilake, D.; Wasala, W.; Palipane, K.B. Design, development and evaluation of a size grading machine for onion. Procedia Food Sci. 2016, 6, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Li, J.; Li, Z.; Zhou, C.; Lu, Y.; Ye, H. Grading Related Feature Extraction of Chinese Mitten Crab Based on Machine Vision. BIO Web Conf. EDP Sci. 2024, 142, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhu, H.; Bi, L.; Xu, W.; Song, N.; Zhou, Z.; Ding, L.; Xiao, M. Quality grading of river crabs based on machine vision and GA-BPNN. Sensors 2023, 23, 5317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, Y. A Sex Recognition Method for Chinese Mitten Crab in Low Light Environment Based on Machine Vision. In Proceedings of the China Automation Congress (CAC), Qingdao, China, 1–3 November 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 4671–4675. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, D.; Duan, Q. Chinese mitten crab detection and sex classification method based on GMNet-YOLOv4. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 214, 108318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siripattanadilok, W.; Siriborvornratanakul, T. Recognition of partially occluded soft-shell mud crabs using Faster R-CNN and Grad-CAM. Aquac. Int. 2024, 32, 2977–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Zhang, G.; Hu, H.; Wei, P.; Duan, Z.; Qian, Y. An improved YOLOv3 algorithm to detect molting in swimming crabs against a complex background. Aquac. Eng. 2020, 91, 102115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Asher, R.; Lahav, O.; Mayer, H.; Nahir, R.; Birnhack, L.; Gendel, Y. Proof of concept of a new technology for prolonged high-density live shellfish transportation: Brown crab as a case study. Food Control. 2020, 114, 107239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, R.A.; Tapella, F.; Romero, M.C. Transportation methods for Southern king crab: From fishing to transient storage and long-haul packaging. Fish. Res. 2020, 223, 105441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Vinson, R.; Holmes, M.; Seibel, G.; Tao, Y. Convolutional neural network guided blue crab knuckle detection for autonomous crab meat picking machine. Opt. Eng. 2018, 57, 43103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, F.; De Conto, E.; Del Grippo, V.; Harrison, S.M.; Fagan, J.; Lyng, J.G.; Brunton, N.P. High-Pressure processing for the production of added-value claw meat from edible crab (Cancer pagurus). Foods 2021, 10, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YerlikAya, P.; Gökoǧlu, N. Quality changes of blue crab (Callinectes sapidus) meat during frozen storage. J. Food Qual. 2004, 27, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, N.B.; Tate, J.W.; Thomas, F.B.; Carawan, R.E.; Monroe, R.J. Effect of freezing, additives, and packaging techniques on the quality of processed blue crab meat. J. Food Prot. 1976, 39, 345–350. [Google Scholar]

- Gates, K.W.; Huang, Y.W.; Parker, A.H.; Green, D.P. Quality characteristics of fresh blue crab meat held at 0 and 4 degrees C in tamper-evident containers. J. Food Prot. 1996, 59, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorentzen, G.; Hustad, A.; Lian, F.; Grip, A.E.; Schrødter, E.; Medeiros, T.; Siikavuopio, S.I. Effect of freezing methods, frozen storage time, and thawing methods on the quality of mildly cooked snow crab (Chionoecetes opilio) clusters. LWT 2020, 123, 109103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, T.A. Effect of processing on bacterial population of cuttle fish and crab and determination of bacterial spoilage and rancidity developing on frozen storage. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2007, 31, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dima, J.B.; Baron, P.; Zaritzky, N. Pasteurization conditions and evaluation of quality parameters of frozen packaged crab meat. J. Aquat. Food Prod. Technol. 2016, 25, 745–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, K.W.; Parker, A.H.; Bauer, D.L.; Huang, Y. Storage changes of fresh and pasteurized blue crab meat in different types of packaging. J. Food Sci. 1993, 58, 314–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, J.; Ling, J.; Shang, H.; Liu, Z. The combined efficacy of superchilling and high CO2 modified atmosphere packaging on shelf life and quality of swimming crab (Portunus trituberculatus). J. Aquat. Food Prod. Technol. 2017, 26, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, C.G.; Jahncke, M.L.; Sumner, S.S.; Boyer, R.R.; Hackney, C.R.; Rippen, T.E. Role of package type on shelf-life of fresh crab meat. Food Prot. Trends 2010, 12, 796–802. [Google Scholar]

- Wiech, M.; Vik, E.; Duinker, A.; Frantzen, S.; Bakke, S.; Maage, A. Effects of cooking and freezing practices on the distribution of cadmium in different tissues of the brown crab (Cancer pagurus). Food Control. 2017, 75, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Feng, M.; Lu, X.; Shi, C.; Li, X.; Xin, J.; Yue, G.; Zhang, S. Base-free preparation of low molecular weight chitin from crab shell. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 190, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gîjiu, C.L.; Isopescu, R.; Dinculescu, D.; Memecică, M.; Apetroaei, M.-R.; Anton, M.; Schröder, V.; Rău, I. Crabs Marine Waste—A Valuable Source of Chitosan: Tuning Chitosan Properties by Chitin Extraction Optimization. Polymers 2022, 14, 4492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajji, S.; Ghorbel-Bellaaj, O.; Younes, I.; Jellouli, K.; Nasri, M. Chitin extraction from crab shells by Bacillus bacteria. Biological activities of fermented crab supernatants. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 79, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, W.J.; Jo, G.H.; Kuk, J.H.; Kim, K.Y.; Park, R.D. Extraction of chitin from red crab shell waste by cofermentation with Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. tolerans KCTC-3074 and Serratia marcescens FS-3. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006, 71, 234–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, R.; Guerrero-Legarreta, I.; Bórquez, R. Chitin extraction from Allopetrolisthes punctatus crab using lactic fermentation. Biotechnol. Rep. 2018, 20, e287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdi, M.; Hammami, A.; Hajji, S.; Jridi, M.; Nasri, M.; Nasri, R. Chitin extraction from blue crab (Portunus segnis) and shrimp (Penaeus kerathurus) shells using digestive alkaline proteases from P. segnis viscera. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 101, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niswar, M.; Wainalang, S.; Ilham, A.A.; Zainuddin, Z.; Fujaya, Y.; Muslimin, Z.; Paundu, A.W.; Kashihara, S.; Fall, D. IoT-based water quality monitoring system for soft-shell crab farming. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Internet of Things and Intelligence System (IOTAIS), Bali, Indonesia, 1–3 November 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Pitakphongmetha, J.; Suntiamorntut, W.; Charoenpanyasak, S. Internet of things for aquaculture in smart crab farming. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1834, 12005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gencer, Ö. The production of carbon quantum dots (CQDs) from cultivated blue crab shells their application in the optical detection of heavy metals in aquaculture. Aquac. Int. 2025, 33, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Saeed, R.; Gao, Q.; Hu, J. Information fusion enabled system for monitoring the vitality of live crabs during transportation. Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 235, 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niswar, M.; Zainuddin, Z.; Fujaya, Y.; Putra, Z.M. An automated feeding system for soft shell crab. Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2017, 5, 564–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Chen, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, D.; Hong, J.; Ruan, C. Research on Automatic Bait Casting System for Crab Farming. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Electromechanical Control Technology and Transportation (ICECTT), Nanchang, China, 15–17 May 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 403–408. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Hong, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, D. Design of trajectory planning system for river crab farming with automatic feeding boat. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. IOP Publ. 2020, 1575, 12143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perea, R.V.; Cullado, J.P.B. ICT-Assisted Growth Management System for Mud crabs (ICT-AGMAS): Deployment and Evaluation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Emerging Techniques in Computational Intelligence (ICETCI), Hyderabad, India, 20–27 August 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, S.; Xu, J.; Yuan, H.; Ku, J.; Liu, Z. Design and Testing of a Fully Automatic Aquatic Plant Combing Machine for Crab Farming. Machines 2024, 12, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hryhorenko, I.; Hryhorenko, S.; Andrenko, D.; Kubrik, B. Technology Control System for Crab Stick Vibration with Fuzzy Logic. In Bulletin of the National Technical University KhPI Series: New Solutions in Modern Technologies; National Technical University “Kharkiv Polytechnic Institute”: Kharkiv, Ukraine, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tavares, C.P.D.S.; Silva, U.A.T.; Pereira, L.A.; Ostrensky, A. Systems and techniques used in the culture of soft-shell swimming crabs. Rev. Aquac. 2018, 10, 913–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zou, T.; Burke, H.; King, S.; Burke, B. A novel approach for porcupine crab identification and processing based on point cloud segmentation. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Advanced Robotics (ICAR), Ljubljana, Slovenia, 6–10 December 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1101–1108. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Zou, T.; Burke, H.; King, S.; Burke, B. Methodology on robot-based complex surface processing using 2D and 3D visual combination. In Proceedings of the WRC Symposium on Advanced Robotics and Automation (WRC SARA), Beijing, China, 21–25 August 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, S.; Jiang, W. Blockchain Traceability Process for Hairy Crab Based on Cuckoo Filter. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmat, A.; Bengen, D.G.; Lestari, D.F.; Agus, S.B.; Pasaribu, R.A.; Jusadi, D.; Panggabean, D. Crab Monitoring System (CMS) using Internet of Things (IoT’s). BIO Web Conf. 2024, 106, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revathi, K.L.; Charukesh, K.; Suprabhas, P.S.; Khan, M.A. AIoT-Based Water Quality Monitoring System for Enhanced Mud Crab Farming. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computing and Intelligent Reality Technologies (ICCIRT), Coimbatore, India, 5–6 December 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.L.; Yang, J.; Ling, P.; Cao, S.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, C. Research on dynamic quality traceability system of Eriocheir sinensis seedling based on IOT smart service. J. Fish. China 2013, 37, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, R.; Tian, W.; Bai, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J. Amine-responsive cellulose-based ratiometric fluorescent materials for real-time and visual detection of shrimp and crab freshness. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakiyabarsi, F.; Aras, R.A.; Hydn; Nur, M.M.; Alfarizi, D.A.; Amri, M.U. Towards The Future of Crab Farming: The Application of AI with Yolox And Yolov9 to Detect Crab Larvae. Inspir. J. Teknol. Inf. Dan Komun. 2024, 14, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yuan, B.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, D.A. Rethinking Underwater Crab Detection via Defogging and Channel Compensation. Fishes 2024, 9, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Zhao, D.; Sun, Y.; Liu, X.; Ruan, C. Automatic coarse-to-fine joint detection and segmentation of underwater non-structural live crabs for precise feeding. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 180, 105905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Tang, C.; Shi, C.; Qian, Y. Detection of residual feed in aquaculture using YOLO and Mask RCNN. Aquac. Eng. 2022, 100, 102304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricohermoso, J.; Javier, P.P.; Balbin, J. An IoT-based Water Salinity Monitoring and Time-Dependent Automatic Feeding System for Mud Crab Aquaculture. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Computer and Automation Engineering (ICCAE), Perth, Australia, 20–22 March 2025; pp. 340–344. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Muhammad, A.; Liu, C.; Du, L.; Li, D. Automatic Recognition of Fish Behavior with a Fusion of RGB and Optical Flow Data Based on Deep Learning. Animals 2021, 11, 2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Gong, M.; Li, Z.; Yang, M. Research on Artificial Intelligence (AI) Recognition Automated Soft-Shell Crab Breeding System under “Internet +” Technology. In Proceedings of the IEEE 3rd International Conference on Electrical Engineering, Big Data and Algorithms (EEBDA), Changchun, China, 27–29 February 2024; pp. 1169–1173. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).