Abstract

Populations of northern pike (Esox lucius) and pumpkinseed (Lepomis gibbosus) from the Mrežnica River were found to be infected with the tapeworm Triaenophorus nodulosus. In both species, the mean intensity of infection was low, suggesting a well-balanced host–parasite relationship. This study investigates pathological changes caused by adult T. nodulosus in its definitive host, the northern pike, and the associated intestinal immune response. The infection had no detectable adverse effects on either the northern pike population or the host’s body condition index. Histological examination revealed lesions both at the site of tapeworm attachment and in areas adjacent to the free strobila, involving the lamina propria and submucosa. A moderate, multifocal, ulcerative, and necrotizing enteritis was observed, accompanied by an increased number of mast cells (MCs), which were identified as the predominant immune cells involved in the E. lucius–T. nodulosus interaction. MCs, mostly degranulated, were found in the lamina propria and superficial submucosa at the attachment site. Immunofluorescence revealed a subpopulation of piscidin 1-positive MCs in the same layers, with a higher number at the attachment site compared to unaffected intestinal areas. This represents the first evidence of piscidin 1 involvement in intestinal host defence against cestode infections in teleosts.

Keywords:

Triaenophorus nodulosus; Esox lucius; Lepomis gibbosus; host–parasite interaction; intestinal pathology; mast cells; piscidin 1; cestode infection Key Contribution:

Piscidin 1 involvement in intestinal host defence against cestode infections in teleosts.

1. Introduction

Triaenophorus nodulosus (Pallas, 1781) is the best-known and most extensively studied species within the genus Triaenophorus Rudolphi, 1793 (Cestoda: Bothriocephalidea). This evolutionarily ancient bothriocephalidean tapeworm has a Holarctic distribution and a complex life cycle [1,2]. Its life cycle involves copepods as the first intermediate hosts, various fish species as second intermediate hosts, and pikes (Esox spp.), namely the northern pike (Esox lucius) and the muskellunge (Esox masquinongy), as definitive hosts [1,3]. The spectrum of its second intermediate hosts is remarkably broad and includes more than 70 species of freshwater fish [4,5]. Among these suitable hosts is the pumpkinseed (Lepomis gibbosus), a species native to North America and introduced into Europe in the 19th century [6]. Infection of pumpkinseed by the larval stage (plerocercoids) of T. nodulosus was first reported in North American waters [7]. Subsequently, the role of pumpkinseed as a second intermediate host was confirmed in several European countries, including Italy [8], Germany [9], Slovakia [10], and France [11], but data from Croatian waters are lacking.

Triaenophorus nodulosus is generally considered the most pathogenic species within the genus [1]. However, it appears that only the plerocercoids of T. nodulosus possess significant pathogenic potential. Since they are typically located in the liver, the resulting pathology can be considerable [12,13]. In large numbers, plerocercoids may cause extensive liver damage [12,14,15], which may in turn lead to alterations in certain haematological parameters, reduced growth, and host death [1]. Moreover, infection with plerocercoids has been associated with high mortality rates in both wild and farmed fish populations [1,12,16]. Within the liver of perch (Perca fluviatilis), one of the preferred second intermediate hosts of T. nodulosus, plerocercoids elicit a granulomatous reaction composed of mast cells (MCs) (predominantly a subpopulation of piscidin 4-immunopositive MCs), fibroblasts, epithelioid cells, and macrophage aggregates [17].

Unlike plerocercoids, adult tapeworms are intestinal parasites with low pathogenicity, even when present in high numbers [1,18,19,20]. Although they may impair normal gut function [18] and enzyme activity [21,22], their pathogenic potential remains poorly studied, and the host immune response has not yet been described in detail. This study investigates the pathological changes caused by adult specimens of T. nodulosus and the associated intestinal immune response in a wild population of northern pike from the Mrežnica River.

2. Materials and Methods

Specimens of northern pike (Esox lucius) and pumpkinseed (Lepomis gibbosus) were collected from the Mrežnica River (Croatia) during a study on pollution-associated pathology. They were incidentally found to be infected with Triaenophorus spp. The study was conducted as part of the Croatian Science Foundation-funded project METABIOM (IP-2019-04-2636) and was approved by the Committee for Ethics in Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Zagreb (Approval No. 640-01/22-02/15).

2.1. Study Area, Sampling, and Data Analysis

Two sites on the Mrežnica River were selected for this study. The first sampling site (REF site; 45°26′28.40″, 15°30′15.39″) was characterized by shallow water with a rocky or gravel bottom and a moderate to fast current. The second site (DRF site; 45°27′4.38″, 15°30′18.96″) was located downstream and featured a deeper, nutrient-rich, muddy-bottom habitat with slow-flowing water (Figure S1). Sampling at both sites was conducted in spring (late April to early May) and autumn (late September), using a boat and electrofishing.

A total of 62 northern pike and 53 pumpkinseed were captured. All fish were euthanized with an overdose of MS-222 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) [23], and necropsy was performed on-site. Prior to necropsy, the body weight and total length of each northern pike were measured and used to calculate Fulton’s condition index (FCI) [24]. Differences in FCI (mean ± SD) between infected and uninfected northern pike were analysed using the Mann–Whitney rank-sum test (SigmaPlot, version 11.0), with the level of significance set at p < 0.05.

All fish from both sampling sites were methodically examined for the presence of Triaenophorus spp. Northern pike were examined for adult tapeworms in the intestine and for plerocercoids in the internal organs, while pumpkinseed were examined for plerocercoids in the internal organs. To compare the two sites, parasite prevalence and mean intensity (the total number of tapeworms found in all infected fish divided by the number of infected fish) were calculated. The parasitological terminology used for prevalence and mean intensity follows Bush et al. [25].

2.2. Parasite Identification

Specimens of Triaenophorus, adult tapeworms from the intestine of northern pike (n = 10) and plerocercoids from the liver of pumpkinseed (n = 3), were carefully removed using dissecting needles, fixed in hot 4% neutral-buffered formalin (NBF), and transported to the laboratory for morphological identification. Morphological identification was based on scolex hook morphology [1,26]. Scolex hooks were measured using an Olympus DP23 digital camera (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and cellSens Entry 4.2 software (Olympus, Münster, Germany).

For molecular identification, adult tapeworms were stored in 70% ethanol. The tapeworm DNA was extracted from a sample of the strobila using the iHelix kit (Institute of Metagenomic and Microbial Technologies, Slovenia; https://www.ihelix.eu/, accessed on 14 September 2025) according to the manufacturer’s instructions [27]. For species determination, three PCRs and Sanger sequencing were employed, targeting the small subunit (12S) mitochondrial rRNA (forward primer 5′ AAAIGGTTTGGCAGTGAGIGA 3′, reverse primer 5′ GCGGTGTGTACITGAGITAAAC 3′) [28], the large subunit (16S) mitochondrial rRNA (forward primer 5′ TRCCTTTTGCATCATG 3′, reverse primer 5′ AATAGATAAGAACCGACCTGGC 3′) [29], and the small subunit (18S) genomic rRNA (forward primer 5′ GTACCCGTTAAATGGATAACTGTAATAA 3′, reverse primer 5′ CAGACATTTGAAGGACCCGTC 3′) [30]. Each PCR reaction mixture was prepared in a 25 μL volume, which contained 1 μM of each primer pair, 0.25 mM of each dNTP (Applied Biosystems by Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 2.5 mM MgCl2 and 1× PCR buffer supplied by the manufacturer, 0.5 U of Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen by Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and 2.5 μL of the extracted DNA. For amplification, VeritiPro Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems by Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used according to the published protocols [28,29,30]. For 12S, the PCR protocol was 15 min at 95 °C; 40 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 54 °C, and 90 s at 72 °C; followed by the elongation step of 10 min at 72 °C [28]. The protocol for 16S was 5 min at 94 °C; 35 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 58 °C, and 30 s at 72 °C; followed by the elongation step of 10 min at 72 °C [29]. The protocol for 18S was 10 min at 94 °C; 40 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 55 °C, and 1 min at 72 °C, followed by the elongation step of 10 min at 72 °C [30]. The obtained PCR amplicons with the expected length 285 bp for 12S, 827 bp for 16S, and 207 bp for 18S were analysed with the QIAxcel capillary electrophoresis system (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and Sanger-sequenced in both directions (Eurofins Genomics Europe, Ebersberg, Germany). The obtained sequences were examined using Geneious Prime v2022.1.1 (Biomatters, New Zealand) and analysed by BLAST 2.17.0 (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/; accessed on 14 September 2025).

Additionally, several adult tapeworms were fixed in NBF and, upon arrival in the laboratory, either stained with alum carmine or routinely processed for histology, sectioned longitudinally, and stained with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) [31]. Two adult tapeworms were also deposited in the Platyhelminthes collection of the Croatian Natural History Museum (CNHM No. 080 and 081).

2.3. Histopathology and Immunofluorescence Assay

To evaluate the extent of intestinal damage caused by adult tapeworms, small samples of the intestine were collected during necropsy and fixed in 10% NBF. No samples were collected from northern pike co-infected with other intestinal helminths (i.e., the nematode Raphidascaris acus and/or the acanthocephalan Acanthocephalus lucii) to ensure accurate histopathological and immunofluorescence evaluation. In the laboratory, the fixed material was embedded in paraffin, and 5 µm thick serial sections were prepared. Sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E), PAS, alcian blue/PAS, and toluidine blue (TB). Additional sections were stained either with Mallory’s trichrome to visualize collagen or with the Verhoeff–Van Gieson method to visualize elastic fibres. Histological slides were examined under an Olympus BX41 light microscope.

For immunofluorescence microscopy, intestinal sections were prepared as described previously [32]. Briefly, sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated, and then treated with 2.5% bovine serum albumin for 60 min and incubated with a primary antibody against piscidin 1 (GenScript Biotech Corporation, Rijswijk, Netherlands; diluted 1:50) in a humid chamber overnight at 4 °C. The secondary antibody used was Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti-rabbit IgG TRITC conjugated (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, Eugene, OR, USA; diluted 1:300). Finally, sections were mounted with Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and examined under a Zeiss LSM DUO confocal laser scanning microscope with a META module (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging GmbH, Jena, Germany). Images were enhanced using Zen 2011 v3.4 software. A negative control was performed by omitting the primary antibody, while rat skin tissue served as a positive control.

3. Results

3.1. Parasite Identification and Infection Dynamics

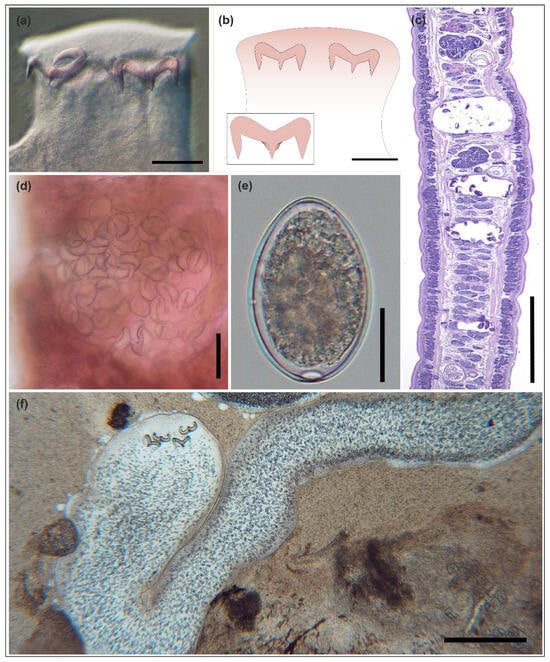

The northern pike and pumpkinseed populations from the Mrežnica River were found to be infected with Triaenophorus spp. tapeworms. The overall prevalence of infection was 25.8% (16/62) in northern pike and 5.7% (3/53) in pumpkinseed. Adult tapeworms (gravid specimens) were found in the anterior third of the northern pike intestine, while plerocercoids were detected in the liver of the pumpkinseed. Based on the morphology of scolex hooks, both adults and plerocercoids were identified as T. nodulosus (Figure 1) (Table S1).

Figure 1.

Triaenophorus nodulosus (Pallas, 1781); adult tapeworm (a–e) from Esox lucius, and plerocercoid (f) from Lepomis gibbosus. (a) Scolex of the adult tapeworm. (b) Schematic drawing of the scolex. Inset: trident-shaped hook. (c) Histological section of a polyzoic strobila showing three gravid proglottids (longitudinal section; PAS staining). (d) Gravid proglottid with a clearly visible uterus filled with eggs (alum carmine staining). (e) Egg removed from the uterus. (f) Plerocercoid in the liver (squash preparation). Scale bars: (a,b,d) = 100 µm; (c,f) = 500 µm; (e) = 20 µm.

The sample of the adult tapeworm generated bands of 285 bp for the 12S rRNA gene, 815 bp for the 16S rRNA gene, and 201 bp for the 18S rRNA gene. After Sanger sequencing, quality trimming, pairwise aligning and blast search, the consensus sequences were most similar to T. nodulosus for the 16S rRNA gene (99.16% identity with 99% query cover) with accession numbers OR065063 and OR065064, and for the 18S rRNA gene (100% identity with 100% query cover) with accession numbers KR780923 and Z98404, while the 12S rRNA gene sequence had no previous entry in the blast core nucleotide database. Sequences were submitted to GenBank under accession numbers PX369339, PX363284, and PX363281 for 12S, 16S, and 18S, respectively.

Infected fish were found at both sampling sites (REF and DRF), but only during spring (April-May). From all northern pike sampled during spring at the REF site, T. nodulosus prevalence was 18.8% (3/16), and mean intensity was 1.3 (range = 1–2). From northern pike sampled during spring at the DRF site, prevalence was 76.5% (13/17), and mean intensity was 1.3 (range = 1–3). Details on sample sizes and the infection parameters are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Numbers of fish sampled at two sites on the Mrežnica River in spring (April–May) and autumn (September), with T. nodulosus prevalence (%) and mean intensity (±SE).

3.2. Body Condition and Gross Pathology

Field observations showed no apparent negative effects of Triaenophorus infection on the northern pike population in the Mrežnica River. FCI did not differ significantly (p > 0.05) between infected (0.69 ± 0.06) and uninfected fish (0.67 ± 0.07) (Table S2). At necropsy, no gross pathological lesions were observed in any infected northern pike, except for two fish co-infected with T. nodulosus and other intestinal helminths (R. acus and/or A. lucii). These co-infected fish exhibited clearly visible catarrhal to mild haemorrhagic enteritis.

3.3. Histopathology and Immunofluorescence Assay

Microscopically, intestinal lesions associated with adult T. nodulosus were multifocal and involved the mucosa and submucosa. They consisted of moderate inflammation and necrotizing changes, with occasional superficial ulcerations caused by deep scolex penetration.

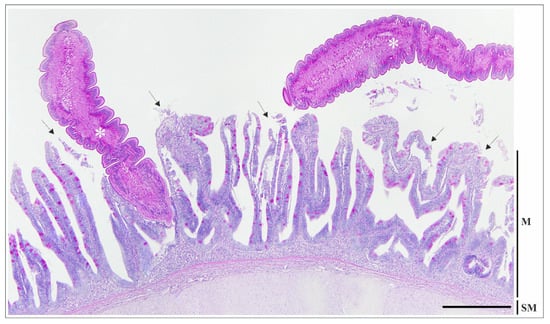

Tapeworms were typically firmly attached between deep mucosal folds, resulting in distortion of the normal mucosal architecture (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Histological section of the intestine of Esox lucius infected with Triaenophorus nodulosus, showing two adult tapeworms (asterisks): one firmly attached between the mucosal folds, and the other with a free strobila within the intestinal lumen. Erosion and desquamation of the mucosal epithelium (arrows) are evident both at the attachment site and in the area adjacent to the free strobila, where the parasite is not in direct contact with the mucosal surface. PAS staining. Scale bar = 500 µm. Abbreviations: M—mucosa; SM—submucosa with two interspersed strata: compactum and granulosum.

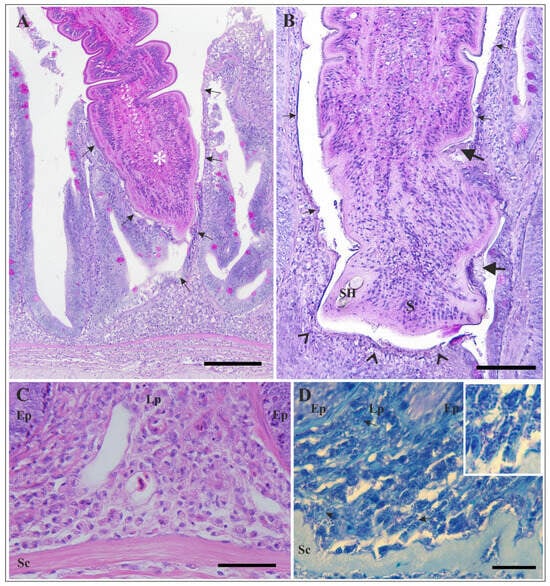

Specifically, diffuse coagulative and/or lytic necrosis of enterocytes was observed adjacent to the scolex and the embedded portion of the strobila. Occasionally, the mucosal epithelium was completely detached and lost into the lumen, while the basement membrane generally remained intact (erosion) (Figure 3A,B and Figure S2). In cases of deeper scolex penetration, superficial ulcerations were noted at the base of atrophic folds (Figure 3B). These ulcerations were sometimes surrounded by a focal area of fibrosis around the scolex.

Figure 3.

Histological sections of the intestine of Esox lucius infected with Triaenophorus nodulosus. (A) High magnification of the attachment site shown in Figure 2. Necrosis and complete loss of the mucosal epithelium adjacent to the embedded part of the strobila (asterisk) are visible (arrows). PAS staining. (B) Section of the intestinal wall at the site of attachment, showing loss of the mucosal epithelium (arrows) and shallow ulceration (arrowheads). Remnants of the damaged mucosal surface are attached to the microtriches of the cestode (thick arrows). PAS staining. (C) High magnification of the intestinal wall beneath the site of attachment. Note the abundant presence of mast cells in the lamina propria and superficial submucosa. H&E staining. (D) Numerous mast cells undergoing intense degranulation are visible beneath the site of attachment (arrows). Inset: High magnification of several mast cells. Note the free granules adjacent to the mast cells. TB staining. Scale bars: (A) = 200 µm; (B) = 100 µm; (C) = 50 µm; (D) = 20 µm. Abbreviations: S—scolex; SH—scolex hook; Ep—epithelium; Lp—lamina propria; Sc—stratum compactum.

Multifocally, the lamina propria and submucosa were infiltrated by a moderate number of inflammatory cells, mainly MCs, with fewer neutrophils and macrophages. MCs were irregular in shape, with an eccentric nucleus and numerous large cytoplasmic granules, while neutrophils were round to oval in shape, with a round or lobed nucleus, and macrophages were larger cells with irregular outlines that sometimes contained phagocytosed material. An increased number of MCs, which were largely degranulated, was observed in the lamina propria, primarily at the base of the folds, and in the superficial submucosa (Figure 3C,D and Figure S2).

Multifocal exocytosis of a few inflammatory cells was also observed among necrotic enterocytes. Occasionally, the intestinal mucosa was lined by cuboidal or low columnar cells, suggesting epithelial regeneration. Additionally, multifocal mild oedema of the lamina propria was observed. Finally, in the affected part of the intestine, T. nodulosus infection did not elicit an increase in rodlet or mucous cell numbers, nor excessive mucus secretion.

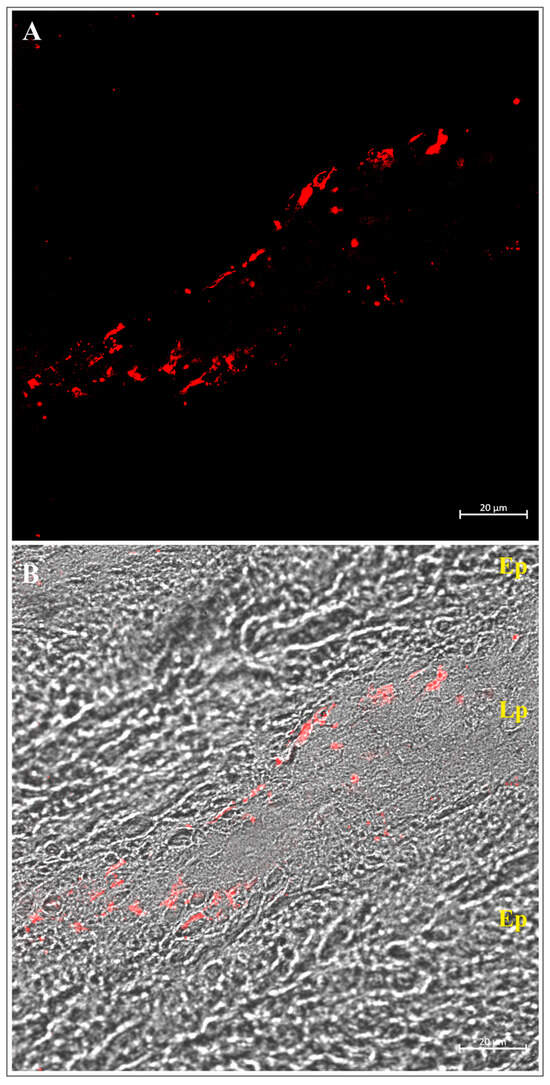

By immunofluorescence, intestinal sections of infected northern pike revealed a subpopulation of piscidin 1-positive MCs. Piscidin-positive MCs were located subepithelially, within the lamina propria and superficial submucosa (Figure 4), with a visibly higher number observed at the site of tapeworm attachment compared to unaffected intestinal areas.

Figure 4.

Confocal (A) and transmitted light (B) images of the intestine of Esox lucius infected with Triaenophorus nodulosus, immunolabeled with an antibody against piscidin 1. Numerous piscidin 1-positive mast cells are visible in the lamina propria below the site of tapeworm attachment. Abbreviations: Ep—epithelium; Lp—lamina propria.

4. Discussion

T. nodulosus is the most widespread species within the genus Triaenophorus and a common intestinal parasite of northern pike throughout Europe [1,17]. This predatory fish is of particular interest in recreational fishing and pond aquaculture in many European countries. It is also widely used as a model organism in studies of ecology and evolutionary biology [33,34,35,36]. Despite the importance of the northern pike as a popular angling species, a valuable food source, and a model organism in scientific research, relatively little has been published on its pathology associated with intestinal helminths [34].

In northern pike infected with Triaenophorus spp., intestinal pathology appears to correlate with the size of the scolex and its hooks [1,19]. The scolex and hooks of Triaenophorus crassus, another well-known member of this genus [2,3], are larger than those of T. nodulosus [1,26]. Furthermore, T. crassus is capable of penetrating more deeply into the intestinal wall [1,19]. Consequently, adult T. crassus can induce extensive intestinal ulceration, accompanied by mixed cellular infiltration and marked fibrosis, which may ultimately lead to thickening of the intestinal wall and partial occlusion of the intestinal lumen [1,19]. More pronounced intestinal lesions have been reported in freshwater fish infected with a few other bothriocephalidean and caryophyllidean cestodes. For example, in common carp (Cyprinus carpio) parasitized by Schyzocotyle acheilognathi (syn. Bothriocephalus acheilognathi) [2,37,38]; in tench (Tinca tinca) parasitized by Monobothrium wageneri [39,40,41]; in suckers (Catostomidae) parasitized by Hunterella nodulosa [42,43,44,45]; and in an endemic chub species (Squalius tenellus) parasitized by Caryophyllaeus brachycollis [46]. In contrast, the intestinal lesions caused by T. nodulosus are generally less severe. A comprehensive review of the literature on the pathogenicity of adult fish tapeworms [1,16,19,37,39,40,42,43,46,47,48,49,50], along with findings from the present study, suggests that the severity of intestinal lesions is determined by a complex interplay of multiple factors. These include the parasite size and total biomass, the morphology of the scolex and its attachment structures, the presence of secretory products from tegumental (frontal) glands, the attachment pattern (clustered or solitary), the depth of penetration, and the evolutionary history of host–parasite relationships.

In the present study, intestinal lesions caused by T. nodulosus were confined to the mucosa and submucosa and were present not only at the immediate site of attachment but also in areas adjacent to the strobila, where the tapeworm was not in continuous intimate contact with the mucosal surface. These lesions are comparable to those caused by T. crassus, but as previously mentioned, they are not as deep or extensive. At the point of scolex attachment, the lesions were characterized by epithelial necrosis and desquamation or, occasionally, shallow ulceration, accompanied by a mild mixed inflammatory infiltrate (composed of neutrophils and macrophages) and an increased number of MCs. It is important to note that the tissue damage and inflammatory response observed adjacent to the strobila of T. nodulosus are consistent with previously published data on the pathogenicity of Triaenophorus spp. [18,19] and a few other adult cestodes, such as the bothriocephalideans S. acheilognathi [38,51] and Eubothrium crassum [52], and the caryophyllideans Atractolytocestus huronensis [48,53], Khawia japonensis [54], and C. brachycollis [46]. Although definitive evidence is lacking, it is plausible that at least some degree of the pathological changes observed near the strobila may result from the effects of excretory-secretory products (ESPs) released to modulate and evade the host immune response [55,56,57,58,59].

Numerous studies have highlighted the important role of fish MCs, also referred to as eosinophilic granular cells [60,61], in orchestrating the intestinal immune response to cestode infections [19,39,40,41,46,62,63]. The role of MCs in the teleost immune system, particularly in response to parasitic infections, was recently reviewed by Sayyaf Dezfuli et al. [64]. Through their effects on vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, neutrophil recruitment, and macrophage activation, MCs play an active role in the inflammatory response [41,61,65,66]. In addition, their interaction with fibroblasts contributes to tissue repair and remodelling [66,67,68,69]. Evidence for co-operation between MCs and neutrophils in response to cestode infections has been observed within the intestinal tract of several fish species [39,41,46,50]. In northern pike parasitized by T. nodulosus, an increased number of MCs, largely degranulated and accompanied by a few neutrophils, was observed within the lamina propria and superficial submucosa at the site of attachment. Given the absence of a lamina muscularis mucosae in the intestine of northern pike [70], these two layers have been collectively referred to as the lamina propria–submucosa [34]. The marked degranulation of MCs at the site of T. nodulosus attachment is consistent with findings in other fish–cestode systems, such as Oncorhynchus mykiss–Eubothrium crassum [71], Tinca tinca–Monobothrium wageneri [39,40,41], and Squalius tenellus–Caryophyllaeus brachycollis [46]. In the presence of intestinal helminths, MCs undergo degranulation, releasing their contents into the neighbouring tissue, and gradually increase in number [61,71] through proliferation of the resident population and/or emigration of the circulating population from blood vessels [62,72].

Intestinal MCs of northern pike contain a mixture of inflammatory and antimicrobial molecules, including piscidin, with piscidin 3-positive MCs found exclusively throughout the lamina propria–submucosa [34]. Piscidins are a group of host defence α-helical peptides with broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity [73,74,75]. In northern pike parasitized by the acanthocephalan A. lucii, a significant increase in the number of piscidin 3-positive MCs was observed in the lamina propria–submucosa [34]. Similarly, at the site of T. nodulosus attachment, we observed a higher number of piscidin 1-positive MCs within the lamina propria and superficial submucosa. Piscidin 1 exhibits antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal, and antiprotozoal activities and also has immunomodulatory properties [74,75,76]. To the best of our knowledge, this paper is the first report providing evidence of piscidin 1 involvement in the intestinal host defence against cestode infections.

The results of the present study indicate that the infection dynamics of T. nodulosus in a wild population of northern pike from the Mrežnica River exhibit clear seasonality, with gravid tapeworms present in spring (April–May) and absent in autumn (September). Although this pattern is consistent with findings reported in the literature [1], the absence of immature tapeworms in autumn may be due to insufficient sampling, potentially influenced by previous restocking. Parasite prevalence in the northern pike population was markedly higher at the downstream site, characterized by deeper, nutrient-rich, slow-flowing water, than at the upstream site, which featured shallow water and a moderate to fast current. However, infection intensity remained low at both sampling sites (REF and DRF), suggesting a well-balanced host–parasite relationship. A wide range of biotic and abiotic factors influence the abundance and prevalence of fish helminths [47], with trophic relationships between hosts playing a significant role in cestode infections [1]. Given the low specificity of plerocercoids for fish second intermediate hosts [4,5], the higher prevalence of T. nodulosus at the nutrient-rich downstream site may reflect a greater abundance of both copepod first intermediate hosts and northern pike as the definitive host. This assumption is further supported by the difference in sampling effort required to capture northern pike, with fish being more readily caught at the downstream site.

5. Conclusions

Although fish helminths can be significant pathogens even in wild populations [47], assessing their pathological effects in these populations remains challenging [77], particularly when infection intensity is low. Many aspects of host–parasite interactions, including the immune response of fish to cestode infections [16] and the effects of parasite ESPs, are still poorly understood and require further research.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fishes10120640/s1, Table S1: Measurements of scolex hooks of Triaenophorus nodulosus from Esox lucius and Lepomis gibbosus, accompanied by data from previous studies. Measurements are presented in µm and are given as range (mean ± SE); Table S2: Body weight and total length measurements of sampled Esox lucius; Figure S1: Map of the Mrežnica River with the sampling area marked; Figure S2: Histological sections of the uninfected intestine of Esox lucius. (A) Normal mucosal architecture. PAS staining. (B) High magnification of the intestinal wall. Note the absence of large numbers of inflammatory cells in the lamina propria and superficial submucosa. H&E staining. (C) High magnification of the intestinal wall. TB staining. Scale bars: (A) = 500 µm; (B) = 50 µm; (C) = 20 µm. Abbreviations: Ep—epithelium; Lp—lamina propria; Sc—stratum compactum.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.G.; methodology, E.G., P.B., A.A. and F.M.; formal analysis, V.B., K.M., P.B. and L.D.; investigation, E.G., V.B., K.M. and S.K.; writing—original draft preparation, E.G., V.B., P.B., A.A. and J.M.A.; writing—review and editing, E.G. and J.M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Croatian Science Foundation (project METABIOM; IP-2019-04-2636), the University of Messina (Visiting Professor Fellowship awarded to E.G. in 2023), and the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency (research core funding no. P4-0092: Animal health, environment and food safety, in 2025).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Ordinance on the Protection of Animals Used for the Scientific Purposes, the Freshwater Fisheries Act, and the Revision of the Management Plan in the Mrežnica Fishing Area, and was approved by the Committee for Ethics in Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Zagreb (Approval No. 640-01/22-02/15; approved on 16 October 2022).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are deeply grateful to the late Slavko Bambir for his continued support and constructive discussions, both during the preparation of this manuscript and throughout the years. Doroteja Benko helped with the illustrations, while Giovanni Lanteri contributed to the collection of literature.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kuperman, B.I. Tapeworms of the Genus Triaenophorus. In Parasites of Fishes; Amerind Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd.: New Delhi, India, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Brabec, J.; Waeschenbach, A.; Scholz, T.; Littlewood, D.T.J.; Kuchta, R. Molecular phylogeny of the Bothriocephalidea (Cestoda): Molecular data challenge morphological classification. Int. J. Parasitol. 2015, 45, 761–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasenko, P.G.; Sokolov, S.G.; Ieshko, E.P.; Frolov, E.V.; Kalmykov, A.P.; Parshukov, A.N.; Chugunova, Y.K.; Kashinskaya, E.N.; Shokurova, A.V.; Bochkarev, N.A.; et al. A re-evaluation of conflicting taxonomic structures of Eurasian Triaenophorus spp. (Cestoda, Bothriocephalidea: Triaenophoridae) based on partial cox1 mtDNA and 28S rRNA gene sequences. Can. J. Zool. 2022, 100, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, T.A.; Chambers, C.; Isinguzo, I. Cestoidea (Phylum Platyhelminthes). In Fish Diseases and Disorders, Protozoan and Metazoan Infections, 2nd ed.; Woo, P.T.K., Ed.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2006; Volume 1, pp. 391–416. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz, T.; Choudhury, A.; McAllister, C.T. A young parasite in an old fish host: A new genus for protocephalid tapeworms (Cestoda) of bowfin (Amia calva) (Holostei: Amiiformes), and a revised list of its cestodes. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2022, 18, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, U.; Molnár, K.; Cech, G.; Eiras, J.C.; Bandyopadhyay, P.K.; Ghosh, S.; Czeglédi, I.; Székely, C. Evidence of the American Myxobolus dechtiari was introduced along with its host Lepomis gibbosus in Europe: Molecular and histological data. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2021, 15, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischthal, J.H. Parasites of northwest Wisconsin fishes III. The 1946 survey. Trans. Wis. Acad. Sci. Arts Lett. 1952, 41, 17–58. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz, T.; Paggi, L.; Di Cave, D.; Orecchia, P. On some cestodes parasitizing freshwater fish in Italy. Parassitologia 1992, 34, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brinker, A.; Hamers, R. First Description of Pumpkinseed Lepomis gibbosus (L.) as a Possible Second Intermediate Host for Triaenophorus nodulosus (Pallas, 1781) (Cestoda, Pseudophyllidea) in Germany. Bull. Eur. Assoc. Fish Pathol. 2000, 20, 83–86. [Google Scholar]

- Košuthová, L.; Koščo, J.; Letková, V.; Košuth, P.; Manko, P. New records of endoparasitic helminths in alien invasive fishes from the Carpathian region. Biologia 2009, 64, 776–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, G.; Vanacker, M.; Fox, M.G.; Beisel, J.-N. Impact of the cestode Triaenophorus nodulosus on the exotic Lepomis gibbosus and the autochthonous Perca fluviatilis. Parasitology 2014, 142, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, G.H. Aspect of the Biology of Triaenophorus nodulosus in Yellow Perch, Perca flavescens, in Heming Lake, Manitoba. J. Fish. Res. Board Can. 1969, 26, 821–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stromberg, P.C.; Crites, J.L. Triaenophoriasis in Lake Erie white bass, Morone chrysops. J. Wildl. Dis. 1974, 10, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechtiar, A.O.; Christie, W.J. Survey of the Parasite Fauna of Lake Ontario Fishes, 1961 to 1971. In Parasites of Fishes in the Canadian Waters of the Great Lakes; Technical Report No. 51; Nepszy, S.J., Ed.; Great Lakes Fishery Commission: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1988; pp. 66–95. [Google Scholar]

- Morley, N.J.; Lewis, J.W. Influence of Triaenophorus nodulosus plerocercoids (Cestoda: Pseudophyllidea) on the occurrence of intestinal helminths in the perch (Perca fluviatilis). J. Helminthol. 2017, 91, 711–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, T.; Kuchta, R.; Oros, M. Tapeworms as pathogens of fish: A review. J. Fish Dis. 2021, 44, 1883–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dezfuli, B.S.; Giari, L.; Lorenzoni, M.; Manera, M.; Noga, E.J. Perch liver reaction to Triaenophorus nodulosus plerocercoids with an emphasis on piscidins 3, 4 and proliferative cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) expression. Vet. Parasitol. 2014, 200, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronina, S.V.; Pronin, N.M. The effect of cestode (Triaenophorus nodulosus) infestation on the digestive tract of pike (Esox lucius). J. Ichthyol. 1982, 22, 641–648. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Shostak, A.W.; Dick, T.A. Intestinal pathology in northern pike, Esox lucius L., infected with Triaenophorus crassus Forel, 1868 (Cestoda: Pseudophyllidea). J. Fish Dis. 1986, 9, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashinskaya, E.N.; Vlasenko, P.G.; Kolmogorova, T.V.; Izotova, G.V.; Shokurova, A.V.; Romanenko, G.A.; Markevich, G.N.; Andree, K.B.; Solovyev, M.M. Metapopulation Structure of Two Species of Pikeworm (Triaenophorus, Cestoda) Parasitizing the Postglacial Fish Community in an Oligotrophic Lake. Animals 2023, 13, 3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frolova, T.V.; Izvekova, G.I. A comparative Analysis of the Effect on Intestinal Cestodes in Different Fish Species on Proteolytic Enzyme Activity. J. Evol. Biochem. Physiol. 2022, 58, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolova, T.V.; Izvekova, G.I. Metabolic Adaptation of Fish Intestinal Helminths: Anti-Protease Inhibitory Ability of Cestodes Triaenophorus nodulosus. J. Evol. Biochem. Physiol. 2023, 59, 1488–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjurčević, E.; Kužir, S.; Valić, D.; Marino, F.; Benko, V.; Kuri, K.; Matanović, K. Pathogenicity of Clinostomum complanatum (Digenea: Clinostomidae) in naturally infected chub (Squalius cephalus) and common carp (Cyprinus carpio). Vet. Arh. 2022, 92, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, R.D.M.; Valencia, A.H.; Geffen, A.J. The Origin of Fulton’s Condition Factor—Setting the Record Straight. Fisheries 2006, 31, 236–238. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, A.O.; Lafferty, K.D.; Lotz, J.M.; Shostak, A.W. Parasitology meets ecology on its own terms: Margolis et al. revisited. J. Parasitol. 1997, 83, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchta, R.; Vlčková, R.; Poddubnaya, L.G.; Gustinelli, A.; Dzika, E.; Scholz, T. Invalidity of three Palaearctic species of Triaenophorus tapeworms (Cestoda: Pseudophyllidea): Evidence from morphometric analysis of scolex hooks. Folia Parasitol. 2007, 54, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandelj, P.; Žele Vengušt, D.; Vengušt, G.; Kušar, D. Case report: First report of potentially zoonotic Gongylonema pulchrum in a free-living roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) in Slovenia. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1444614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roelfsema, J.H.; Nozari, N.; Pinelli, E.; Kortbeek, L.M. Novel PCRs for differential diagnosis of cestodes. Exp. Parasitol. 2016, 161, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taube, K.; Noreikiene, K.; Kahar, S.; Gross, R.; Ozerov, M.; Vasemägi, A. Subtle transcriptomic response of Eurasian perch (Perca fluviatilis) associated with Triaenophorus nodulosus plerocercoid infection. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2023, 22, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boufana, B.; Žibrat, U.; Jehle, R.; Craig, P.S.; Gassner, H.; Schabetsberger, R. Differential diagnosis of Triaenophorus crassus and T. nodulosus experimental infection in Cyclops abyssorum praealpinus (Copepoda) from the Alpine Lake Grundlsee (Austria) using PCR-RFLP. Parasitol. Res. 2011, 109, 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chervy, L. Manual for the study of tapeworms (Cestoda) parasitic in ray-finned fish, amphibians and reptiles. Folia Parasitol. 2024, 71, 001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesci, A.; Capillo, G.; Mokhtar, D.M.; Fumia, A.; D’Angelo, R.; Cascio, P.L.; Albano, M.; Guerrera, M.C.; Sayed, R.K.A.; Spanò, N.; et al. Expression of Antimicrobic Peptide Piscidin1 in Gills Mast Cells of Giant Mudskipper Periophthalmodon schlosseri (Pallas, 1770). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsman, A.; Tibblin, P.; Berggren, H.; Nordahl, O.; Koch-Schmidt, P.; Larsson, P. Pike Esox lucius as an emerging model organism for studies in ecology and evolutionary biology: A review. J. Fish Biol. 2015, 87, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyaf Dezfuli, B.; Giari, L.; Lorenzoni, M.; Carosi, A.; Manera, M.; Bosi, G. Pike intestinal reaction to Acanthocephalus lucii (Acanthocephala): Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural surveys. Parasites Vectors 2018, 11, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosi, G.; Lorenzoni, M.; Carosi, A.; Sayyaf Dezfuli, B. Mucosal Hallmarks in the Alimentary Canal of Northern Pike Esox lucius (Linnaeus). Animals 2020, 10, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dragun, Z.; Ivanković, D.; Tepić, N.; Filipović Marijić, V.; Šariri, S.; Mijošek Pavin, T.; Drk, S.; Gjurčević, E.; Matanović, K.; Kužir, S.; et al. Metal Bioaccumulation in the Muscle of the Northern Pike (Esox lucius) from Historically Contaminated River and the Estimation of the Human Health Risk. Fishes 2024, 9, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, J.R.; Pegg, J.; Williams, C.F. Pathological and Ecological Host Consequences of Infection by an Introduced Fish Parasite. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e26365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, T.; Kuchta, R.; Williams, C. Bothriocephalus acheilognathi. In Fish Parasites: Pathobiology and Protection; Woo, P.T.K., Buchmann, K., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2012; pp. 282–297. [Google Scholar]

- Dezfuli, B.S.; Giari, L.; Squerzanti, S.; Lui, A.; Lorenzoni, M.; Sakalli, S.; Shinn, A.P. Histological damage and inflammatory response elicited by Monobothrium wageneri (Cestoda) in the intestine of Tinca tinca (Cyprinidae). Parasites Vectors 2011, 4, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.F.; Poddubnaya, L.G.; Scholz, T.; Turnbull, J.F.; Ferguson, H.W. Histopathological and ultrastructural studies of the tapeworm Monobothrium wageneri (Caryophyllidea) in the intestinal tract of tench Tinca tinca. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2011, 97, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezfuli, B.S.; Lui, A.; Giari, L.; Castaldelli, G.; Shinn, A.P.; Lorenzoni, M. Innate immune defence mechanisms of tench, Tinca tinca (L.), naturally infected with the tapeworm Monobothrium wageneri. Parasite Immunol. 2012, 34, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackiewicz, J.S.; Cosgrove, G.E.; Gude, W.D. Relationship of Pathology to Scolex Morphology among Caryophyllid Cestodes. Z. Parasitenkd. 1972, 39, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayunga, E.G. Observations on the intestinal pathology caused by three caryophyllid tapeworms of the white sucker Catostomus commersoni Laécpède. J. Fish Dis. 1979, 2, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, T.; Waeschenbach, A.; Oros, M.; Brabec, J.; Littlewood, D.T.J. Phylogenetic reconstruction of early diverging tapeworms (Cestoda: Caryophyllidea) reveals ancient radiations in vertebrate hosts and biogeographic regions. Int. J. Parasitol. 2021, 51, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, O.M.; Rubtsova, N.Y. Revisiting Hunterella nodulosa Mackiewicz and McCrae, 1962 (Cestoda: Caryophyllidae) from Catostomus commersoni (Lacépède) with a Special Treatment of its Ecological Diversity in Wisconsin Waters. Int. J. Zool. Anim. Biol. 2023, 6, 000473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyaf Dezfuli, B.; Franchella, E.; Bernacchia, G.; De Bastiani, M.; Lorenzoni, F.; Carosi, A.; Lorenzoni, M.; Bosi, G. Infection of endemic chub Squalius tenellus with the intestinal tapeworm Caryophyllaeus brachycollis (Cestoda): Histopathology and ultrastructural survey. Parasitology 2024, 151, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.; Jones, A. Parasitic Worms of Fish; Taylor & Francis Ltd.: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gjurčević, E.; Beck, A.; Drašner, K.; Stanin, D.; Kužir, S. Pathogenicity of Atractolytocestus huronensis (Cestoda) from cultured common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.). Vet. Arh. 2012, 82, 273–282. [Google Scholar]

- Bosi, G.; Maynard, B.J.; Pironi, F.; Sayyaf Dezfuli, B. Parasites and the neuroendocrine control of fish intestinal function: An ancient struggle between pathogens and host. Parasitology 2022, 149, 1842–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyaf Dezfuli, B.; Lorenzoni, M.; Carosi, A.; Bosi, G.; Franchella, E.; Poddubnaya, L.G. Glandular cell products in adult cestode: A new tale of tapeworm interaction with fish innate immune response. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2024, 25, 100991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoole, D.; Nisan, H. Ultrastructural studies on intestinal response of carp, Cyprinus carpio L., to the pseudophyllidean tapeworm, Bothriocephalus acheilognathi Yamaguti, 1934. J. Fish Dis. 1994, 17, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosi, G.; Shinn, A.P.; Giari, L.; Simoni, E.; Pironi, F.; Dezfuli, B.S. Changes in the neuromodulators of the diffuse endocrine system of the alimentary canal of farmed rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum), naturally infected with Eubothrium crassum (Cestoda). J. Fish Dis. 2005, 28, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molnár, K.; Majoros, G.; Csaba, G.; Székely, C. Pathology of Atractolytocestus huronensis Anthony, 1958 (Cestoda, Caryophyllaeidae) in Hungarian pond-farmed common carp. Acta Parasitol. 2003, 48, 222–228. [Google Scholar]

- Barčák, D.; Madžunkov, M.; Uhrovič, D.; Miko, M.; Brázová, T.; Oros, M. Khawia japonensis (Cestoda), the Asian parasite of common carp, continues to spread in Central European countries: Distribution, infection indices and histopathology. BioInvasions Rec. 2021, 10, 934–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, A.L.; Pittaway, C.E.; Sparrow, R.M.; Balkwill, E.C.; Coles, G.C.; Tilley, A.; Wilson, A.D. Analysis of caecal mucosal inflammation and immune modulation during Anoplocephala perfoliata infection of horses. Parasite Immunol. 2019, 41, e12667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochneva, A.; Drozdova, P.; Borvinskaya, E. The first transcriptomic resource for the flatworm Triaenophorus nodulosus (Cestoda: Bothriocephalidea), a common parasite of Holarctic freshwater fish. Mar. Genom. 2020, 51, 100702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazanec, H.; Koník, P.; Gardian, Z.; Kuchta, R. Extracellular vesicles secreted by model tapeworm Hymenolepis diminuta: Biogenesis, ultrastructure and protein composition. Int. J. Parasitol. 2021, 51, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutyrev, I.A.; Biserova, N.M.; Mazur, O.E.; Dugarov, Z.N. Experimental study of ultrastructural mechanisms and kinetics of tegumental secretion in cestodes parasitizing fish (Cestoda: Diphyllobothriidea). J. Fish Dis. 2021, 44, 1237–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlyuchenkova, A.N.; Kutyrev, I.A.; Fedorov, A.V.; Chelombitko, M.A.; Mazur, O.E.; Dugarov, Z.N. Investigation into Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Excretory/Secretory Products from Gull-Tapeworm Dibothriocephalus dendriticus and Ligula Ligula interrupta Plerocercoids. Mosc. Univ. Biol. Sci. Bull. 2023, 78, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A.E. Histamine, mast cells and hypersensitivity responses in fish. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 1982, (Suppl. 2), 147–155. [Google Scholar]

- Reite, O.B.; Evensen, Ø. Inflammatory cells of teleostean fish: A review focusing on mast cells/eosinophilic granule cells and rodlet cells. Fish Shellfish Immun. 2006, 20, 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezfuli, B.S.; Bosi, G.; DePasquale, J.A.; Manera, M.; Giari, L. Fish innate immunity against intestinal helminths. Fish Shellfish Immun. 2016, 50, 274–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Hakeem, S.S.; Fadladdin, Y.A.J.; Khormi, M.A.; Abd-El-Hafeez, H.H. Modulation of the intestinal mucosal and cell-mediated response against natural helminth infection in the African catfish Clarias gariepinus. BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayyaf Dezfuli, B.; Lorenzoni, M.; Carosi, A.; Giari, L.; Bosi, G. Teleost innate immunity, an intricate game between immune cells and parasites of fish organs: Who wins, who loses. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1250835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumsden, J.S. Gastrointestinal Tract, Swimbladder, Pancreas and Peritoneum. In Systemic Pathology of Fish: A Text and Atlas of Normal Tissues in Teleosts and Their Responses in Disease, 2nd ed.; Ferguson, H.W., Ed.; Scotian Press: London, UK, 2006; pp. 168–199. [Google Scholar]

- Dezfuli, B.S.; Manera, M.; Bosi, G.; DePasquale, J.A.; D’Amelio, S.; Castaldelli, G.; Giari, L. Anguilla anguilla intestinal immune response to natural infection with Contracaecum rudolphii A larvae. J. Fish Dis. 2016, 39, 1187–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dezfuli, B.S.; Giovinazzo, G.; Lui, A.; Giari, L. Inflammatory response to Dentitruncus truttae (Acanthocephala) in the intestine of brown trout. Fish Shellfish Immun. 2008, 24, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dezfuli, B.S.; Lui, A.; Giari, L.; Pironi, F.; Manera, M.; Lorenzoni, M.; Noga, E.J. Piscidins in the intestine of European perch, Perca fluviatilis, naturally infected with an enteric worm. Fish Shellfish Immun. 2013, 35, 1539–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayyaf Dezfuli, B.; Fernandes, C.E.; Galindo, G.M.; Castaldelli, G.; Manera, M.; DePasquale, J.A.; Lorenzoni, M.; Bertin, S.; Giari, L. Nematode infection in liver of the fish Gymnotus inaequilabiatus (Gymnotiformes: Gymnotidae) from the Pantanal Region in Brazil: Pathobiology and inflammatory response. Parasites Vectors 2016, 9, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vukšić, M. Histological and Histochemical Identification of Mast Cells in Fish. Master’s Thesis, The University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia, 2023. (In Croatian). [Google Scholar]

- Dezfuli, B.S.; Lui, A.; Boldrini, P.; Pironi, F.; Giari, L. The inflammatory response of fish to helminth parasites. Parasite 2008, 15, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezfuli, B.S.; Giari, L. Mast cells in the gills and intestines of naturally infected fish: Evidence of migration and degranulation. J. Fish Dis. 2008, 31, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silphaduang, U.; Noga, E.J. Peptide antibiotics in mast cells of fish. Nature 2001, 414, 268–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, S.V.; Sarkar, P.; Kumar, P.; Arockiaraj, J. Piscidin, Fish Antimicrobial Peptide: Structure, Classification, Properties, Mechanism, Gene Regulation and Therapeutical Importance. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2021, 27, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Parra, C.; Serna-Duque, J.A.; Espinosa-Ruiz, C.; Albadalejo-Riad, N.; Bardera, G.; Thompson, K.; Esteban, M.Á. Piscidin 1 and 2 of gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata): New insights into their role as host defense peptides. Fish Shellfish Immun. 2025, 165, 110501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccone, G.; Capillo, G.; Fernandes, J.M.O.; Kiron, V.; Lauriano, E.R.; Alesci, A.; Cascio, P.L.; Guerrera, M.C.; Kuciel, M.; Zuwala, K.; et al. Expression of the Antimicrobial Peptide Piscidin 1 and Neuropeptides in Fish Gill and Skin: A Potential Participation in Neuro-Immune Interaction. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feist, S.W.; Longshaw, M. Histopathology of fish parasite infections—Importance for populations. J. Fish Biol. 2008, 73, 2143–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).