Abstract

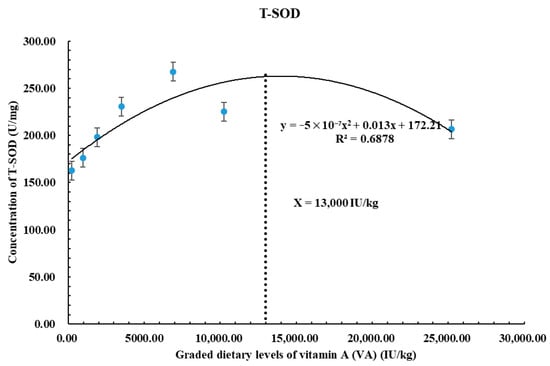

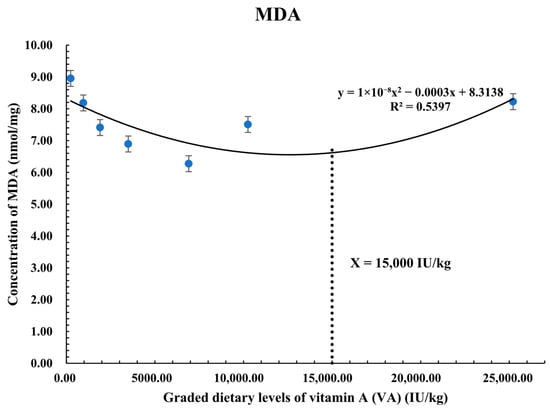

Vitamin A (VA) is an essential micronutrient that improves growth, immune activity, and antioxidant responses in fish. This study focuses on optimizing VA dietary levels for Oncorhynchus kisutch (Coho salmon) alevins. A 12-week trial was conducted using seven diets containing graded dietary VA levels of 244, 957, 1902, 3494, 6906, 10,248, and 25,213 IU/kg. A total of 2100 fish were reared in 21 tanks; 100 fish were housed in each tank, and 3 tanks represented one treatment. Peak (SGR) and FBW were observed at 6906 IU/kg. Excess VA levels (>15,000 IU/kg) compromised feed conversion efficacy and led to oxidative stress. Analysis of proximate composition resulted in protein and lipid deposition at optimal VA levels. However, excess may have led to metabolic disturbances and reduced ash content. The activity of the antioxidant enzymes catalase (CA), acid phosphatase (ACP), alkaline phosphatase (AKP), and total superoxide dismutase (T-SOD) revealed biphasic patterns, peaking at 6906 IU/kg and dropping when VA levels were exceeded, inducing pro-oxidant effects. Malondialdehyde (MDA), the indicator of toxicity, had a minimal value of 15,000 IU/kg. VA accumulation in the liver showed a dose-dependent relationship, while excess storage (>25,000 IU/kg) induced hepatotoxicity. Quadratic regression was used to identify the optimum VA levels required in Coho salmon alevins, ranging from 6906 to 10,248 IU/kg. Polynomial quadratic regression results indicated that the predicted dietary inclusion of VA at 3000 IU/kg and 15,000 IU/kg may yield better results of T-SOD and MDA. Real-world experimentation is recommended to explore long-term VA optimization with other nutrients and promote better feed utilization and sustainable aquaculture practices.

Keywords:

fish nutrition; lipid metabolism; liver health; immune response; oxidative biomarkers; aquaculture sustainability Key Contribution:

This study identified 6906–10,248 IU/kg to be the optimal vitamin A range for proper growth and health in Coho salmon alevins. This range boosts growth, protein retention, and antioxidant defense. Excessive levels lead to liver toxicity and oxidative stress. The findings provide valuable insights into species-specific feed formulation to promote sustainable aquaculture practices.

1. Introduction

The aquaculture industry plays a vital role in global food production, ensuring food safety and security. Sustainable aquaculture systems not only support production but also influence the nutritional quality of fish, underlining the importance of optimized feed formulations [1,2]. Although vitamins are needed in small quantities, they are important essential organic compounds obtained from dietary sources. They are crucial for the normal growth, reproduction, and health of fish [3]. In recent studies, vitamins, antioxidants, and natural compounds have been particularly significant in sustaining immune functions and oxidative balance in aquaculture species [4]. Vitamin A (VA) is a fat-soluble vitamin that commonly exists in forms of retinal, retinol, and retinoic acid, which contain aldehyde, alcohol, and acid groups, respectively [5]. Although required in small amounts, VA is effective for physiological processes like vision, growth, differentiation, and immunity [6,7,8]. VA not only plays important roles in erythropoiesis, iron metabolism, and regulation, but is also directly and indirectly involved in the activation of transcription factors regulating more than 500 genes [9]. Despite the recognized importance of vitamin A in animal nutrition and health, relatively few studies have examined this vitamin’s effects on the immune system and disease resistance in fish. VA does not undergo de novo synthesis, which is why farmed fish obtain their VA requirement from their diet. A balanced amount of VA is crucial; insufficient or excess intake causes poor growth and mortality [10,11]. In salmonid aquaculture, at least 3–4 fat-soluble vitamins are mandatory for healthy farming. VA deficiencies in salmonids lead to photophobia, ascites, edema, and exophthalmia [12]. The requirements of VA vary with species and factors, such as size, age, nutrient interrelationship, and temperature. Dietary VA levels and antioxidant components have been studied in many different fish species. Undesirable VA levels, whether the result of deficiency or excess intake, reduce antioxidative enzymes such as SOD (superoxide dismutase) and CAT (catalase) [13,14].

Oncorhynchus kisutch (Coho salmon) is one of the seven recognized Pacific salmon. It is widely distributed in Russia’s Far East around the Bering Sea, in Alaska, and south along the North American coast to California. It is important both commercially and in sport fisheries [15]. In China, Coho salmon has been farmed on a large scale [16]. Taking an inadequate amount of any vitamin can lead to disturbances in fish homeostasis [17]. The vitamin content in salmonid feed has been revised as studies have advanced in understanding the functional nutrients available to fish. For better survival, growth, stress resistance, and food quality, feed must contain VA dietary supplements [3].

Optimizing vitamins is crucial for the sustainable development of salmonid aquaculture. To determine the nutritional requirements of fish, it is important to study the effects different nutrient levels have on growth. Fish experts recommend ameliorating the VA supplement according to fish species and developmental stages (Xu et al., 2022) [16]. VA influences growth level through morphogenesis and cellular differentiation, which is essential for skeleton and tissue development. Fish species have shown positive results when VA is provided in an optimal formulation; this supplementation has been proven to combat free radicals produced from oxidative stress [18].

Previous investigations determined the VA requirement for Coho salmon post-smolts based on growth performance [16]. However, VA requirements for the critical Coho salmon alevin stage remain unexplored. Therefore, the current study evaluated the effect of dietary VA supplementation on growth, biochemical composition, and oxidative stress in Coho salmon alevins.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Diets

This study was carried out strictly in accordance with the recommendations in the “Guide for the Ethical Use of Experimental Animals” of Weifang University, Weifang, Shandong, China (No. 20200601). Vitamin A (VA) in the form of retinyl acetate was purchased from NHU Co., Ltd., Shaoxing, China. Seven different feeds were formulated by supplementing the basal diet with graded levels of pure retinyl acetate. The inclusion rates of the VA supplement were 0.000%, 0.002%, 0.004%, 0.008%, 0.016%, 0.024%, and 0.060% of the diet weight (g/100 g), respectively. This resulted in analyzed dietary VA concentrations of 244.00, 957.00, 1902.00, 3494.00, 6906.00, 10,248.00, and 25,213.00 IU/kg, respectively. The basal diet (244 IU/kg VA), which contained no supplemental retinyl acetate, served as the control group. During feed manufacturing, a low-temperature extrusion process was employed to minimize heat exposure and prevent thermal degradation of vitamin A. Fresh feed was prepared every month to maintain potency. The formulation and proximate composition of the feed are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Formulation and proximate composition used in the experimental diets for Coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) alevins (% dry matter).

2.2. Experimental Conditions and Animal Management

Coho salmon alevins were cultured at the Coho Salmon Health Culture Engineering Technology Center of Shandong Collaborative Innovation Center (Weifang, China) and procured from the Shandong Freshwater Fisheries Research Institute, China. The alevins were acclimatized to the experimental conditions prior being transferred into the tanks. The tanks were food-grade white plastic tanks (Shandong Conqueren Marine Technology Co., Ltd., Weifang, China). The experiment was conducted in a controlled laboratory environment using 21 white plastic tanks (0.8 × 0.6 × 0.6 m, L × W × H, water volume 240 L/tank). Each tank contained 100 fish, and each dietary treatment was assigned to three replicate tanks in a randomized design. Throughout the 12-week trial, fish were reared in underground spring water, which was filtered using a polypropylene (PP) sediment filter. The photoperiod was maintained to simulate a natural light regime. The water quality parameters were maintained within the following ranges: temperature, 15.6 ± 0.6 °C; dissolved oxygen, 9.1 ± 0.3 mg/L; and pH, 7.2 ± 0.3. Fish were fed their respective experimental diets four times daily (7:30, 11:00, 14:30, and 17:50) to apparent satiation.

3. Sampling Procedures

Method for Euthanizing Coho Salmon Alevins

At the end of the feeding trial, the fish were subjected to a 24-hour fasting period to ensure their digestive systems were empty. Following this, fish were anesthetized using tricaine methanesulfonate (MS222) at a concentration of 30 mg/L to minimize stress and discomfort. After cessation of opercular movement, liver and muscle tissues were dissected and instantly preserved in liquid nitrogen. Samples were then stored at −80 °C for further biochemical analysis.

4. Sampling Protocols and Analytical Techniques

Evaluation of Growth Performance

The growth performance of fish was assessed by recording body weight and the number of fish in each replicate at both the beginning and end of the trial. At the trial’s conclusion, three fish from each replicate were randomly selected for further analysis. Their final body weight and length were measured, after which they were promptly dissected to collect whole-body muscle, liver, and viscera samples. These samples were weighed and stored at −20 °C for later analysis.

We used whole-body muscle samples to determine body composition, and liver samples were analyzed for optimal VA, ACP, AKP, CAT, and T-SOD levels. The recorded data were used to calculate several growth and health indices, including the survival rate (SR), weight gain (WG), specific growth rate (SGR), feed conversion ratio (FCR), protein efficiency ratio (PER), condition factor (CF), hepatosomatic index (HSI), and viscerosomatic index (VSI). The formulas for these calculations are presented as follows:

- Survival Rate (SR):

SR (%) = (Final number of fish/Initial number of fish) × 100.

- Weight Gain (WG):

WG (g) = (Final weight (g) − Initial weight (g))/Initial weight (g).

- Specific Growth Rate (SGR):

SGR (%/day) = [(ln(Final body weight) − ln(Initial body weight))/Days] × 100.

- Feed Conversion Ratio (FCR):

FCR = Total feed intake (g)/(Final body weight (g) − Initial body weight (g)).

- Protein Efficiency Ratio (PER):

Protein intake (g) = Total feed intake (g) × Protein percentage in feed.

PER = Weight gain (g)/Protein intake (g).

- Condition Factor (CF):

CF (%) = (Weight (g)/Length3 (cm)) × 100.

- Hepatosomatic Index (HSI):

HSI (%) = (Liver weight/Final body weight) × 100.

- Viscerosomatic Index (VSI):

VSI (%) = (Visceral weight/Final body weight) × 100.

5. Analysis of Feed and Whole-Body Chemical Composition

We analyzed feed samples and stored whole-body muscle samples from the dissected fish to assess nutrient composition using the methods outlined by the Association of Official Analytical Chemists [19]. The crude protein content was determined using a Kjeldahl apparatus (Automatic Apparatus Kjeltec 8400, FOSS, Hillerød, Denmark), and nitrogen content was converted to protein using a factor of 6.25. Crude fat was measured using a Soxhlet apparatus (ST 243, FOSS, Hillerød, Denmark). Moisture content was determined by drying samples at 105 °C in a hot-air oven until a constant weight was achieved. Finally, for crude ash analysis, samples were incinerated in a muffle furnace at 550 °C for 12 h.

6. Liver Vitamin A Measurement

Samples of liver tissue (0.2 g) were thoroughly homogenized. The resulting homogenates from both muscle and liver were subsequently examined using a previously reported method [20] to determine the concentration of VA in the tissues.

7. Liver Tissue Immune and Antioxidative Activity Analysis

The liver tissue samples were processed in a 0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) at 4 °C, after which they were prepared for further examination. Analyses were conducted using commercially available assay kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) with a Microplate reader (Tecan Spark10M, Grödig, Austria). All procedures adhered strictly to the guidelines provided by the kit manufacturers. Specifically, the activity of SOD in liver samples was assessed using the xanthine oxidase technique, with absorbance readings taken at 550 nm [21]. CAT activity was evaluated by monitoring the reduction in hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) levels that occurred at an absorbance wavelength of 405 nm [22]. MDA levels were quantified using the thiobarbituric acid (TBA) assay, with measurements recorded at 532 nm [23]. Additionally, the activities of both liver AKP and ACP were determined using an enzymatic colorimetric approach, following the methodology outlined in [24].

8. Statistical Analyses

The data obtained from the experiment were statistically analyzed by one-way ANOVA in SPSS software (IBM SPSS 21.0) to determine the mean values. The significance between the mean values was tested using Duncan’s test, and the values in the table represent the mean ± standard deviation. The level of significant difference is p < 0.05. Polynomial quadratic regression was performed to predict suitable dietary concentration levels of VA for T-SOD and MDA.

9. Results

9.1. Growth Performance and Feed Utilization

Growth performance and feed utilization were significantly influenced by dietary vitamin A levels in Coho salmon alevins over the 12-week feeding trial. Survival rates remained high and statistically similar across all treatment groups (93.33–97.00%). Specific growth rates and final body weight both peaked at 3.35%/day and 5.86 g, respectively, in the group fed 6906 IU/kg VA (p < 0.001), with marked reductions observed at both lower and higher concentrations. Coho salmon alevins possessed an optimal feed conversion ratio (1.03) with VA (6906 IU/kg) supplementation, indicating efficient nutrient utilization, while protein efficiency was highest within the 6906–10,248 IU/kg range. No significant differences were detected in HSI; however, a significant response to dietary VA (p = 0.001) was observed for VSI. Significant differences were obtained for various condition factors among dietary treatments, suggesting that morphological development in alevins is influenced by VA intake (Table 2).

Table 2.

Growth performance and feed utilization of Coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) alevins fed diets with graded levels of vitamin A (VA) for 12 weeks.

9.2. Whole-Body Proximate Composition

Analysis of proximate composition showed variation in crude protein, moisture, crude lipid, and ash content. The crude protein content significantly increased, peaking at 10,248 IU/kg (p < 0.001). This implies protein synthesis. Likewise, the crude lipid content also significantly increased with dietary VA supplementation, stabilizing at around 6906–10,248 IU/kg (p < 0.001). On the other hand, ash content showed a downward trend with increased VA levels (p = 0.022) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Whole-body proximate composition of Coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) alevins fed diets with graded levels of vitamin A (VA) for 12 weeks.

9.3. Liver VA Concentrations

Regarding dietary VA levels (p < 0.001), liver VA concentration significantly increased by 290-fold. This upward trend was observed from the lowest to highest values of (0.09 µg/g at 244 IU/kg) and (26.01 µg/g at 25,213 IU/kg), respectively. This shows that an excess of VA accumulation in the liver might lead to hepatic toxicity (Table 4).

Table 4.

Liver vitamin A (VA) concentrations of Coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) alevins fed diets with graded levels of VA for 12 weeks.

9.4. Liver Immune and Antioxidant Responses

Liver enzyme activities (ACP and AKP) showed a biphasic response to dietary VA levels. Both enzymes reached peak activity at moderate VA levels (3494–6906 IU/kg) and significantly decreased at higher concentrations (10,248–25,213 IU/kg) (p < 0.001). This suggests that VA levels in the moderate range enhance the innate immune system; however, above-normal VA levels may have immunosuppressive effects. Antioxidative enzymes (CAT and T-SOD) showed the same pattern, with maximum levels at 6906 IU/kg (p < 0.001). While an increase in VA levels significantly decreases lipid peroxidation, with the lowest levels at 6906 IU/kg, it increases with higher VA supplementation (p < 0.001). We can conclude that while a moderate range of VA enhances antioxidative defense, an excess amount can lead to oxidative stress (Table 5).

Table 5.

Liver immune and antioxidant activities of Coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) alevins fed diets with graded levels of vitamin A (VA) for 12 weeks.

Figure 1 depicts the association between dietary vitamin A levels and total superoxide dismutase (T-SOD) activity in Oncorhynchus kisutch alevins. T-SOD is the main antioxidant enzyme that provides protection against oxidative stress by minimizing ROS. The polynomial quadratic regression demonstrates that with the increased intake of dietary VA levels, T-SOD activity also increases, reaching its initial highest peak at approximately 13,000 IU/kg. Beyond this limit, the activity of T-SOD decreases, indicating that excess VA levels cause enzyme suppression and an imbalance in oxidative activity. However, moderate VA levels maintain the antioxidant defense mechanism. The reason for this reduction could be the generation of ROS due to pro-oxidant effects. This result emphasizes the importance of maintaining VA dietary levels (around 13,000 IU/kg) to enhance antioxidant protection in Coho salmon alevins while avoiding potential toxicity.

Figure 1.

Polynomial quadratic regression analysis of T-SOD with graded levels of vitamin A (VA) in Coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) alevins. The predicted VA requirement for T-SOD was 13,000 IU/kg.

Figure 2 portrays the quadratic regression of MDA levels in response to graded VA levels. High levels of MDA correspond with elevated oxidative stress and cellular damage, as MDA is a biomarker of lipid peroxidation. MDA showed an inverse relationship with VA intake, exhibiting the lowest value of 15,000 IU/kg. This suggests that increased VA intake reduces cellular damage and lipid peroxidation. However, above this limit, a rise in MDA levels occurs. This indicates that excess supplementation of VA has a pro-oxidant effect, which increases rather than mitigates oxidative stress.

Figure 2.

Polynomial quadratic regression analysis of MDA with graded levels of vitamin A (VA) in Coho salmon alevins. The predicted VA requirement for MDA was 15,000 IU/kg.

10. Discussion

The present study investigated dietary vitamin A (VA) requirements and its effect on the growth performance, whole-body composition, immune response, liver VA concentration, and antioxidant capacity of Coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) alevins. The growth and health status of fish can vary due to many factors, including water quality, fish size, feeding period during the trial, and the nutrient variability of the experimental diet. While inadequate VA levels could lead to reduced growth and feed utilization, excess amounts might be toxic, causing deformities like stunted growth and mortality [25,26]. Some research reported that excess VA dietary supplementation leads to retinol oxidation and toxic metabolite accumulation in some fish [27].

10.1. Growth Performance

The final body weight and specific growth rate of Coho salmon alevins were enhanced with gradual dietary supplementation of vitamin A, and peak values were estimated at 6906 IU/kg. These findings are in agreement with the previous studies on salmonids, where VA dietary supplementation of 6422 IU/kg significantly improved the specific growth rate of Coho salmon post-smolts [16]. However, the peak value of Amur sturgeon (Acipenser schrenckii) occurred at a VA supplementation rate of 1050 IU/kg in the diet before decreasing after this limit [28]. In addition, Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) exhibited a better growth rate with a VA dietary supplementation of 3505 IU/kg in the diet [17]. The higher VA dietary requirements in Coho salmon diets may be associated with species differences, their feeding nature, feeding practices, and varying assessment criteria. The higher FCR observed at the highest vitamin A level (25,213 IU/kg) was likely due to oxidative stress caused by metabolic disturbances. This forces fish to utilize energy to combat oxidative damage, thus reducing nutrient utilization and growth. This is consistent with a previous study on grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella), in which excessive VA supplementation induced a pro-oxidant response that diverted energy from growth to cellular repair, leading to reduced feed efficiency and a higher FCR [11]. Optimum values of the feed conversion ratio (FCR) and protein efficiency ratio (PER) were observed at 6906 IU/kg for dietary VA supplementation. These results reinforce the fact that moderate levels of dietary VA supplementation boost lipid metabolism and protein retention in chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) [29]. Nevertheless, excessive VA supplementation in the case of European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax) caused a reduction in lipid peroxidation and a sudden decline in FCR [30]. Our study on Coho salmon alevins reported a gradual decline in FCR beyond the optimal value of dietary VA supplementation, suggesting that different fish species have different metabolic adaptations against alleviating VA levels in the diet.

Dietary VA supplementation did not influence the hepatosomatic index (HSI), as no significant variation was found for HSI. However, the viscerosomatic index (VSI) displayed a notable response to vitamin A, reflecting an alleviated visceral fat deposition. Similar observations were recorded in dourado (Salminus brasiliensis), where the size of the liver was not affected by enhanced levels of VA supplementation in their diet [31]. Notably, a higher HIS value was noticed in Wuchang bream (Megalobrama amblycephala) fed with diets devoid of vitamin A compared to fish-fed diets supplemented with vitamin A [6]. This unexpected rise in the HSI value without vitamin A could be connected with fat deposition, oxidative stress, and species-specific metabolic responses.

10.2. Whole-Body Muscle Proximate Analysis

Proximate analysis revealed significant changes in crude protein, moisture, crude lipid, and ash content with varying VA levels. The decline in moisture content along with VA supply aligns with previous findings [31], suggesting that VA plays a role in minimizing water retention in muscle tissues. In contrast, amplification in crude protein content with an increase in VA dietary levels deviates from the previous findings on Cyprinus carpio, which showed an inverse relation between crude protein and VA levels. This discrepancy could be due to species, habitat, and dietary preferences. The direct relationship between crude lipid content and VA supplementation is consistent with previous reports indicating that an increase in VA supply contributes to lipid deposition in muscle tissues [9]. However, reduced ash content with an increase in VA supplementation contradicts the findings on Atlantic salmon [10], which states that there are no significant changes in ash content with VA intake. This conflict suggests that Coho salmon have a unique response to VA supplementation, possibly associated with differences in mineral metabolism. Further experimentation is recommended to elucidate the underlying effects of VA on proximate composition to optimize VA levels in different fish species.

10.3. VA Accumulation and Toxicity in Liver

This study reported a dose-dependent increase in VA levels by 290-fold in Coho salmon livers. These findings agree with a previous study on Atlantic salmon [32] and Nile tilapia [33], which reported a positive correlation between dietary VA intake and liver accumulation. The significant variation in VA concentration with dietary VA levels is also supported by an earlier study on hybrid tilapia [34] and grass carp [35]. However, the current study reports that excessive dietary VA levels (>25,213 IU/kg) could lead to hepatotoxicity. This contrasts with findings in Atlantic salmon post-smolts, which showed a greater resilience to excessive VA levels, highlighting that tolerance to VA toxicity is species-specific [10]. This is why optimization of dietary VA levels is crucial to prevent hepatotoxicity and ensure the health status of Coho salmon.

10.4. Antioxidative Enzymes and Immune Response

The present study clarifies the fact that dietary vitamin A is linked to immune and antioxidant responses in Coho salmon. The activities of ACP and AKP peaked at moderate VA levels (6906 IU/kg), depicting the fact that optimum VA supplementation enhances the immune response. However, an increase beyond the moderate range (>6906 IU/kg) reduces enzyme activity, indicating an immunosuppressive response. This finding supports previous studies, emphasizing the importance of VA for maintaining homeostasis in fish [13,36].

Peak activities of antioxidant enzymes (CAT and T-SOD) were observed at 6906 IU/kg but declined afterwards. These results reinforce the previous findings in Coho salmon post-smolts and northern whiting (Sillago Sihama), indicating that the ability of various VA levels to enhance antioxidant defense is species-specific [14,16,37]. The reduced MDA levels with VA intake suggest that oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation are mitigated. However, an excessive increase in VA levels (>15000 IU/kg) also increases MDA levels, indicating pro-oxidant effects. The quadratic regression analysis of T-SOD and MDA underscores the necessity of optimizing VA levels. A VA level of 13,000 IU/kg enhances antioxidant activity and leads to oxidative stress; however, levels exceeding 15,000 IU/kg do not. Therefore, species-specific VA supplementation is crucial for the maintenance of immune homeostasis in Coho salmon [18].

10.5. Optimal VA Requirement for Coho Salmon Alevins

An analysis of the polynomial quadratic regression presented in this study reveals maximum T-SOD activity at 13,000 IU/kg VA levels and the lowest MDA level at 15,000 IU/kg. Considering growth performance, immune response, and antioxidant response, the optimum VA level for Coho salmon alevins ranges from 6906 to 10,248 IU/kg. These findings suggest a significantly higher VA requirement for Coho salmon alevins (6906–10,248 IU/kg) compared to the higher level of intake required for other salmonids, such as Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) post-smolts. These species demonstrated resilience to diets containing up to 25,300 IU/kg of VA without the evidence of hepatotoxicity observed in the present study [10]. This marked contrast underscores a fundamental species-specific difference in VA metabolism and tolerance between members of the Oncorhynchus and Salmo genera. This indicates that every fish species has a unique requirement of VA to ensure proper growth, immunity, and antioxidant response. Moreover, genetic and metabolic factors also contribute to VA utilization among different species.

11. Conclusions

The current findings identified 6906–10,248 IU/kg as the optimal dietary vitamin A range for better growth, health, and antioxidant activity in Coho salmon alevins. Beyond this range, VA triggers a pro-oxidant response that compromises the immune system, leading to hepatotoxicity. Future research should focus on long-term feeding trials to validate optimal levels of VA in aquaculture practices. It should also explore potential synergetic interactions between VA and other nutrients, such as selenium and vitamin E, for maximum nutrient utilization in aquaculture feeds. Furthermore, targeting species-specific VA delivery methods like microencapsulation or phased supplementation could minimize toxicity and ensure sustainable production of Coho salmon.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Y. and H.Y.; Data curation, H.Z. and M.Y.; Formal analysis, A.R., S.S. and M.S.; Investigation, G.S. and L.L.; Methodology, H.Z. and S.S.; Project administration, L.Y. and H.Y.; Software, G.S. and L.L.; Validation, L.Y. and H.Y.; Writing—original draft, A.R., S.S., and M.S.; Writing—review and editing, L.Y., H.Y., A.R., H.Z., S.S., M.S. and M.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Shandong Provincial Key Research and Development Programs (Major Scientific and Technological Innovation Projects, MSTIP), Grant/Award Numbers: 2018CXGC0102 and 2019JZZY020710; the scientific and Technologic Development Program of Weifang, Grant/Award Number: 2019ZJ1046; and the Technical Development (Entrustment) Project between University and Enterprise (Grant/Award Number: 20240701CLFWFU01).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The present study was carried out according to the recommendations in the “Guide for the Ethical Use of Experimental Animals” of Weifang University, Weifang, Shandong, China (Approval Code: No. 20200601; Approval Date:16 May 2022). This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of Modern Facility Fisheries, Weifang University, China (IACUC NO. 20220516003). The funder was not involved in the study design; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the article; or the decision to submit it for publication.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data contained in the article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors Abdur Rahman and Sattanathan Govindharajan were employed by Conqueren Leading Fresh Science & Technology Inc., Ltd. The author Lingyao Li was employed by Shandong Conqueren Marine Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022: Towards Blue Transformation; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turlybek, N.; Nurbekova, Z.; Mukhamejanova, A.; Baimurzina, B.; Kulatayeva, M.; Aubakirova, K.M.; Alikulov, Z. Sustainable Aquaculture Systems and Their Impact on Fish Nutritional Quality. Fishes 2025, 10, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Santigosa, E.; Dumas, A.; Hernandez, J.M. Vitamin Nutrition in Salmonid Aquaculture: From Avoiding Deficiencies to Enhancing Functionalities. Aquaculture 2022, 561, 738654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Ma, W.; Zhang, D.; Tian, Z.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Hong, Y. Application of Natural Antioxidants as Feed Additives in Aquaculture: A Review. Biology 2025, 14, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Ahmed, I.; Reshi, Q.M.; Hassan, P. Role of Fat-Soluble Vitamins in Fish Nutrition. In Aquaculture: Enhancing Food Security and Nutrition; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 203–224. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Zhao, Z.; Brown, P.B.; Cui, H.; Xie, J.; Habte-Tsion, H.M.; Ge, X. Dietary Vitamin A Requirement of Juvenile Wuchang Bream (Megalobrama amblycephala) Determined by Growth and Disease Resistance. Aquaculture 2016, 45, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battisti, E.K.; Marasca, S.; Durigon, E.G.; Villes, V.S.; Schneider, T.L.; Uczay, J.; Peixoto, N.C.; Lazzari, R. Growth and Oxidative Parameters of Rhamdia quelen Fed Dietary Levels of Vitamin, A. Aquaculture 2017, 474, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, L.H.; Hardy, R.W. Vitamin A Functions and Requirements in Fish. Aquac. Res. 2020, 51, 3061–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Ahmed, I.; Wani, G.B. Effect of Supplementation of Vitamin A on Growth, Haemato-Biochemical Composition, and Antioxidant Ability in Cyprinus carpio var. communis. Aquac. Nutr. 2022, 1, 8446092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornsrud, R.; Lock, E.J.; Waagbø, R.; Krossoy, C.; Fjelldal, P.G. Establishing an Upper Level of Intake for Vitamin A in Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar L.) Postsmolts. Aquac. Nutr. 2013, 19, 651–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.D.; Zhang, L.; Feng, L.; Wu, P.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, J.; Zhou, X.Q. Inconsistently Impairment of Immune Function and Structural Integrity of Head Kidney and Spleen by Vitamin A Deficiency in Grass Carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Fish. Shellfish. Immunol. 2020, 99, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, R.S.M. Vitamin Deficiency and Toxicity. In Aquaculture Pathophysiology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 693–702. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, L.Y.; Zhu, X.M.; Yang, Y.X.; Jin, J.Y.; Liu, H.K.; Han, D.; Xie, S.Q. Effects of Dietary Vitamin A on Growth, Hematology, Digestion and Lipometabolism of Ongrowing Gibel Carp (Carassius auratus gibelio var. CAS III). Aquaculture 2016, 460, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.C.; Kwaku, A.; Du, T.; Tan, B.P.; Chi, S.Y.; Yang, Q.H.; Yang, Y.Z. Dietary Vitamin A Requirement of Sillago sihama Forskál. Aquac. Res. 2018, 49, 2587–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J.L. Pacific Fishes of Canada; Fisheries Research Board of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1973; p. 740. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.M.; Yu, H.R.; Li, L.Y.; Li, M.; Qiu, X.Y.; Zhao, S.S.; Shan, L.L. Dietary Vitamin A Requirements of Coho Salmon Oncorhynchus kisutch (Walbaum, 1792) Post-Smolts. Aquaculture 2022, 560, 738448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimaraes, I.G.; Pezzato, L.E.; Santos, V.G.; Orsi, R.O.; Barros, M.M. Vitamin A Affects Haematology, Growth and Immune Response of Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus L.), but Has No Protective Effect against Bacterial Challenge or Cold-Induced Stress. Aquac. Res. 2016, 47, 2004–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shastak, Y.; Pelletier, W. Vitamin A in Fish Well-Being: Integrating Immune Strength, Antioxidant Capacity and Growth. Fishes 2024, 9, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC, 16th ed.; Helric, K., Ed.; Association of Analytical Chemists, Inc.: Arlington, VA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ostermeyer, U.; Schmidt, T. Determination of Vitamin K in the Edible Part of Fish by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2001, 212, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCord, J.M.; Fridovich, I. Superoxide Dismutase: An Enzymic Function for Erythrocuprein (Hemocuprein). J. Biol. Chem. 1969, 244, 6049–6055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebi, H. Catalase in vitro. In Methods in Enzymology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984; Volume 105, pp. 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buege, J.A.; Aust, S.D. Microsomal Lipid Peroxidation. Methods Enzymol. 1978, 52, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tietz, N.W.; Burtis, C.A.; Duncan, P.; Ervin, K.; Petitclerc, C.J.; Rinker, A.D.; Zygowicz, E.R. A Reference Method for Measurement of Alkaline Phosphatase Activity in Human Serum. Clin. Chem. 1983, 29, 751–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moren, M.; Opstad, I.; Berntssen, M.H.G.; Infante, J.L.Z.; Hamre, K. An Optimum Level of Vitamin A Supplements for Atlantic Halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus L.) Juveniles. Aquaculture 2004, 235, 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, L.H.H.; Teshima, S.I.; Ishikawa, M.; Alam, S.; Koshio, S.; Tanaka, Y. Dietary Vitamin A Requirements of Juvenile Japanese Flounder Paralichthys olivaceus. Aquac. Nutr. 2005, 11, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, H.L.H.; Teshima, S.I.; Koshio, S.; Ishikawa, M.; Tanaka, Y.; Alam, M.S. Effects of Vitamin A on Growth, Serum Anti-Bacterial Activity and Transaminase Activities in the Juvenile Japanese Flounder, Paralichthys olivaceus. Aquaculture 2007, 262, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Yan, A.S.; Gao, Q.; Jiang, M.; Wei, Q.W. Dietary Vitamin A Requirement of Juvenile Amur Sturgeon (Acipenser schrenckii). J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2008, 24, 534–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvy, J.E.; Symonds, J.E.; Hilton, Z.; Walker, S.P.; Tremblay, L.A.; Casanovas, P.; Herbert, N.A. The Relationship of Feed Intake, Growth, Nutrient Retention, and Oxygen Consumption to Feed Conversion Ratio of Farmed Saltwater Chinook Salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha). Aquaculture 2022, 554, 738184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villeneuve, L.; Gisbert, E.; Le Delliou, H.; Cahu, C.L.; Zambonino-Infante, J.L. Dietary Levels of All-Trans Retinol Affect Retinoid Nuclear Receptor Expression and Skeletal Development in European Sea Bass Larvae. Br. J. Nutr. 2005, 93, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, J.F.A.; Sabioni, R.E.; Aguilar, F.A.A.; Lorenz, E.K.; Cyrino, J.E.P. Vitamin A Requirements of Dourado (Salminus brasiliensis): Growth Performance and Immunological Parameters. Aquaculture 2018, 491, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, I.; Fletcher, T.C.; Houlihan, D.F.; Secombes, C.J. The Effect of Dietary Vitamin A on the Immunocompetence of Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar L.). Fish Physiol. Biochem. 1994, 12, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campeche, D.F.B.; Catharino, R.R.; Godoy, H.T.; Cyrino, J.E.P. Vitamin A in Diets for Nile Tilapia. Sci. Agric. 2009, 66, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.J.; Chen, S.M.; Pan, C.H.; Huang, C.H. Effects of Dietary Vitamin A or β-Carotene Concentrations on Growth of Juvenile Hybrid Tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus × O. aureus. Aquaculture 2006, 253, 602–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhu, W.; Liu, M.; Chen, C.; Chen, J.; Tan, Q. Effects of Dietary Vitamin A on Growth Performance, Blood Biochemical Indices and Body Composition of Juvenile Grass Carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus). Turk. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2016, 16, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpwaga, A.Y.; Gyan, R.W.; Ding, M.Y.; Tan, B.; Chi, S.; Yang, Q. Effects of Dietary Vitamin A Supplementation on Growth, Immune Response, and Lipid Metabolism in Mid-Stage Epinephelus coioides. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2025, 323, 116274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattman, C.L.; Schaefer, L.M.; Oury, T.D. Extracellular Superoxide Dismutase in Biology and Medicine. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003, 35, 236–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).