Effects of Shifts in Bacterial Community on Improving Water Quality and Growth Performance of Pacific Whiteleg Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) in Biofloc Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Shrimp Acclimation, Experimental Design, Operation, and Management

2.2. High-Throughput Sequencing and Data Processing

2.3. Determination of 16S rRNA Gene Copies

2.4. Analysis of Bacterial Composition Profile

2.5. Analysis of Bacterial Diversity

2.6. Water Quality Parameters

2.7. Zootechnical Indices

2.8. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

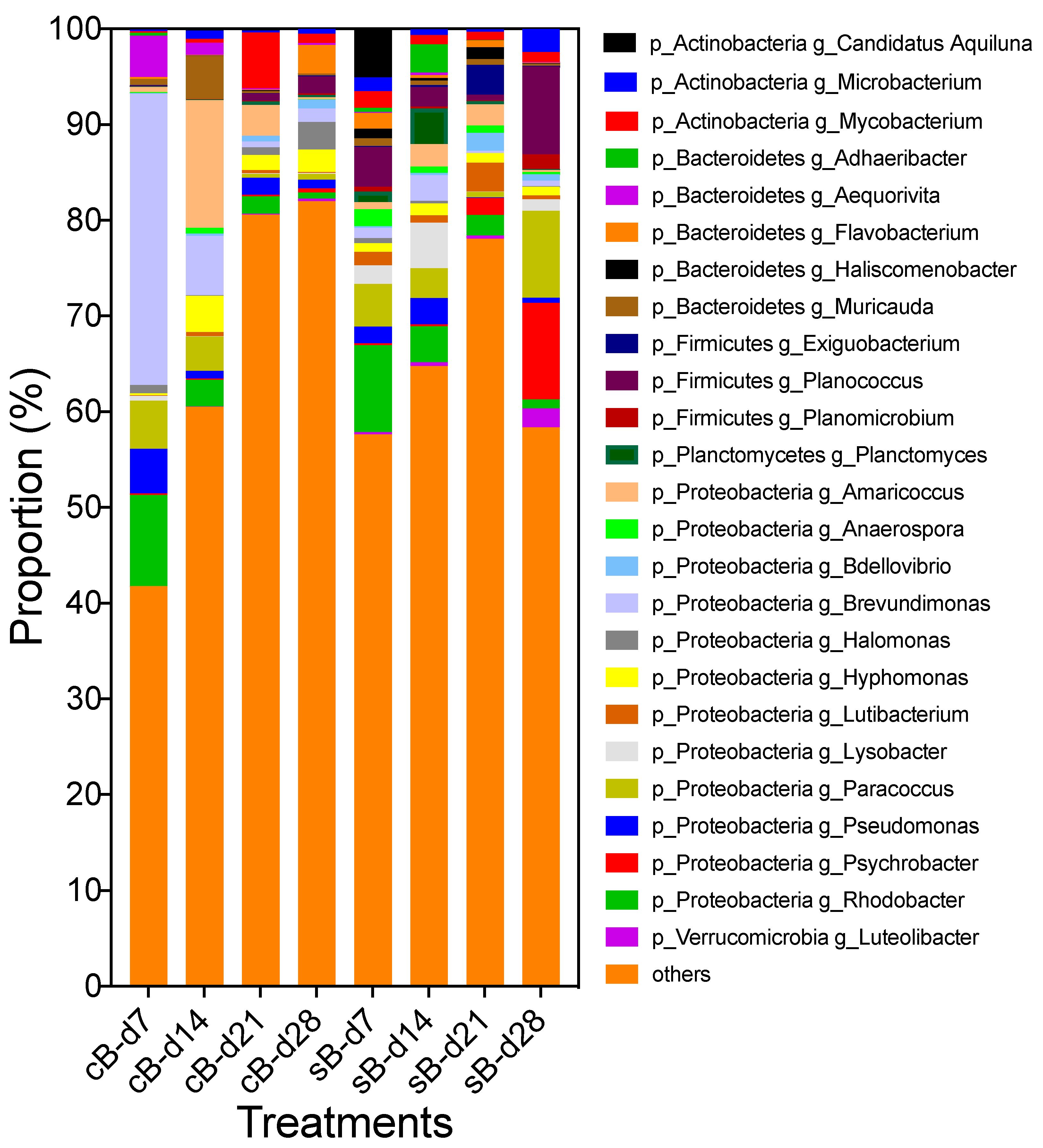

3.1. Bacterial Composition Profile

3.2. Absolute Abundances of Bacterial Taxa

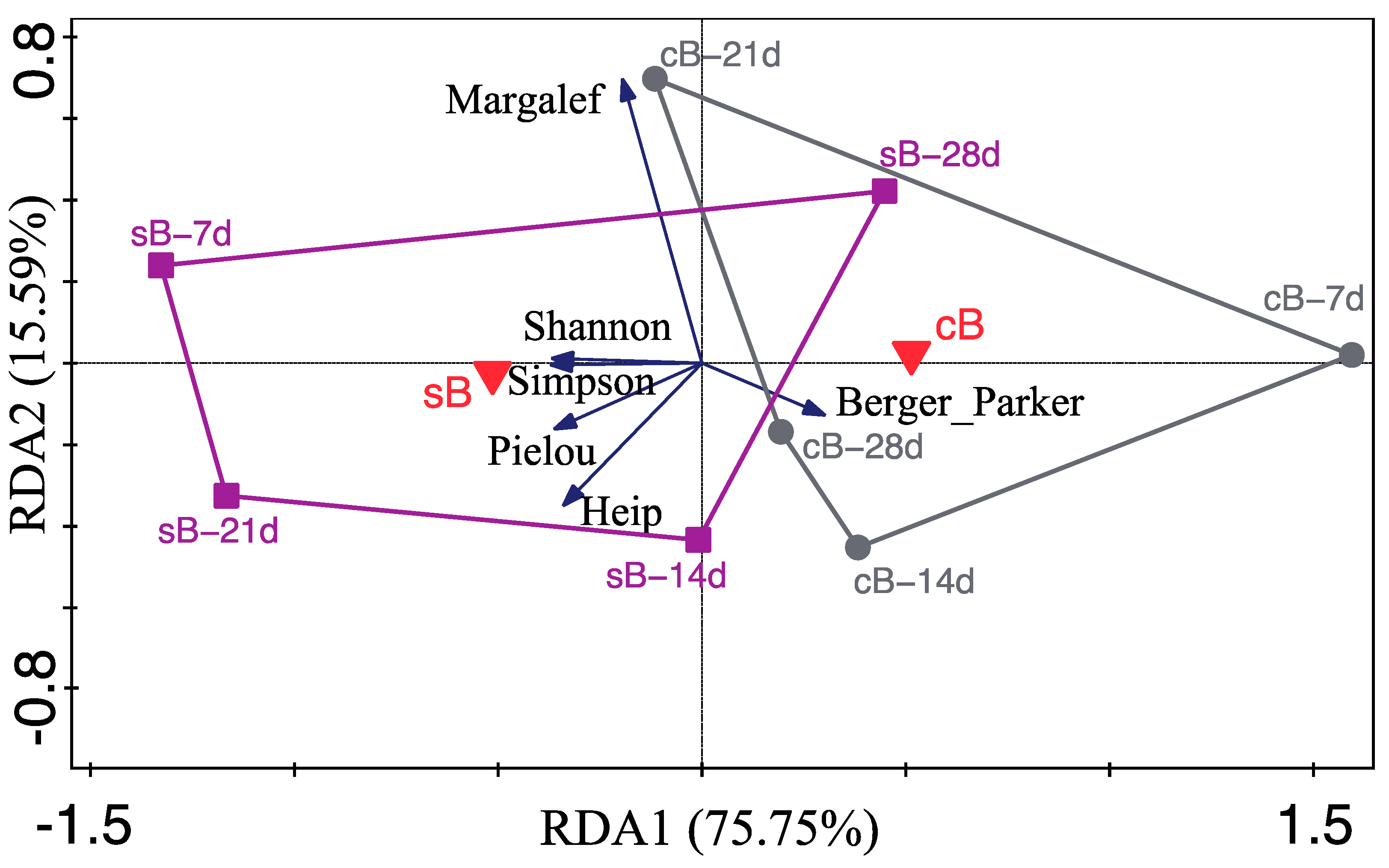

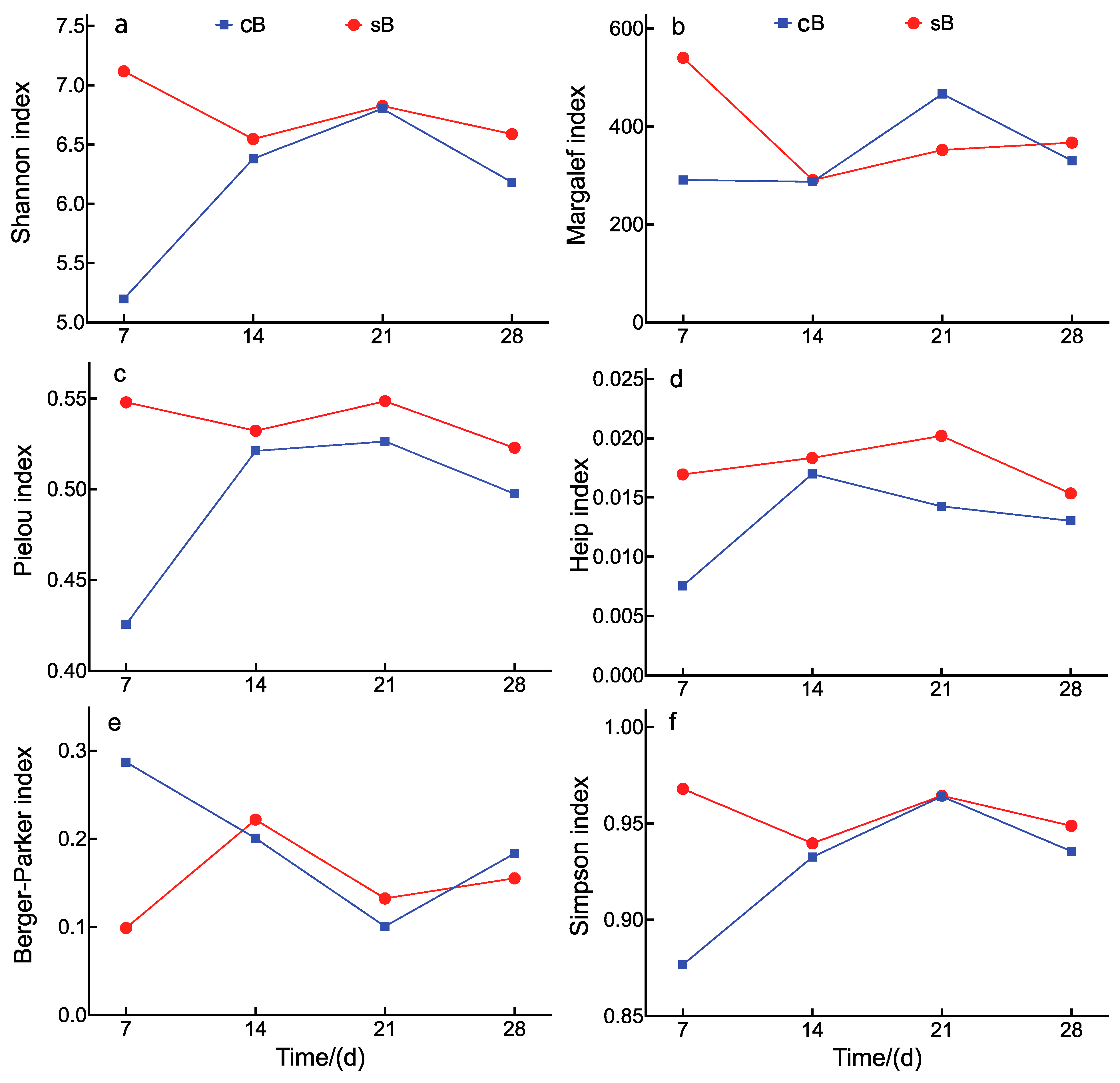

3.3. Bacterial Diversity

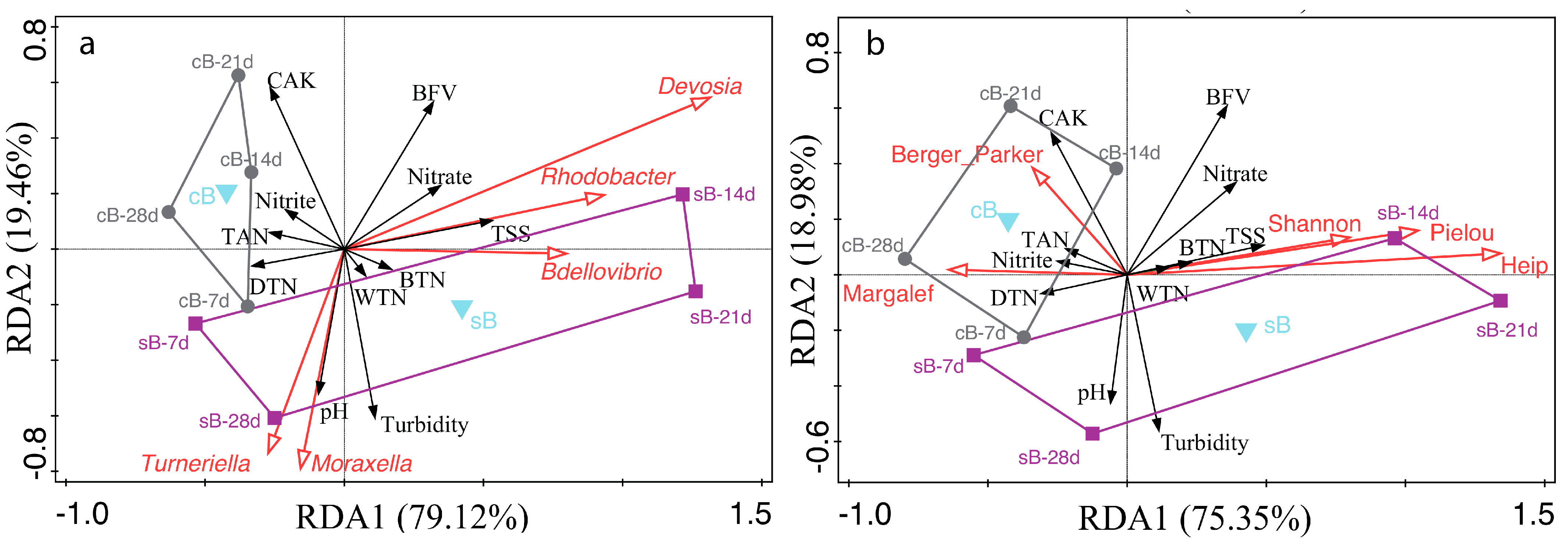

3.4. Water Quality

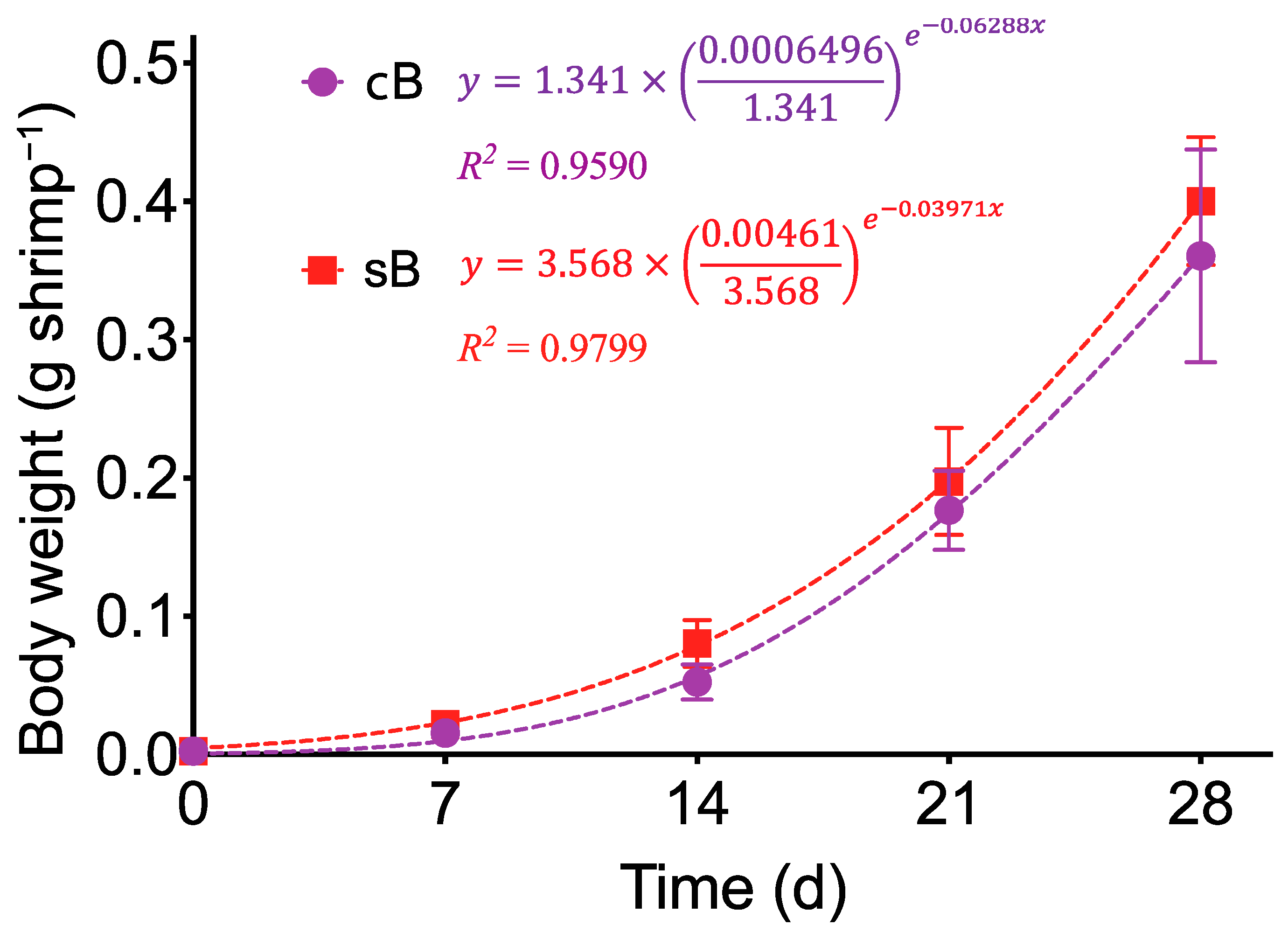

3.5. Growth Performance

4. Discussion

4.1. Bacterial Composition and Diversity of the Biofloc System Shifted After Addition of Substrate

4.2. Shift in Bacterial Community Induced by Adding Substrate Positively Affected Water Quality

4.3. Shift in Bacterial Community Induced by Adding Substrate Improved the Growth Performance of Shrimp

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture: Towards Blue Transformation; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wyk, P.; Davishodgkins, M.; Laramore, R.; Main, K.L.; Mountain, J.; Scarpa, J. Farming Marine Shrimp in Recirculating Freshwater Systems; Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services: Tallahassee, FL, USA, 1999; pp. 1–219.

- BFMA (Bureau of Fisheries of the Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China). China Fishery Statistical Yearbook; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2025.

- Huang, H.-H.; Li, C.-Y.; Song, Y.; Lei, Y.-J.; Yang, P.-H. Growth performance of shrimp and water quality in a freshwater biofloc system with a salinity of 5.0‰: Effects on inputs, costs and wastes discharge during grow-out culture of Litopenaeus vannamei. Aquacult. Eng. 2022, 98, 102265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, L.A.; Davis, D.A.; Saoud, I.P.; Boyd, C.A.; Pine, H.J.; Boyd, C.E. Shrimp culture in inland low salinity waters. Rev. Aquac. 2010, 2, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.J.; Drury, T.H.; Cecil, A. Comparing clear-water RAS and biofloc systems: Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) production, water quality, and biofloc nutritional contributions estimated using stable isotopes. Aquacult. Eng. 2017, 77, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krummenauer, D.; Abreu, P.C.; Poersch, L.; Paiva Reis, P.A.C.; Suita, S.M.; dos Reis, W.G.; Wasielesky Jr, W. The relationship between shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) size and biofloc consumption determined by the stable isotope technique. Aquaculture 2020, 529, 735635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avnimelech, Y. Biofloc Technology: A Practical Hand Book, 3rd ed.; The World Aquaculture Society: Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Khanjani, M.H.; Mohammadi, A.; Emerenciano, M.G.C. Microorganisms in biofloc aquaculture system. Aquacult. Rep. 2022, 26, 101300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abakari, G.; Wu, X.; He, X.; Fan, L.; Luo, G. Bacteria in biofloc technology aquaculture systems: Roles and mediating factors. Rev. Aquacult. 2022, 14, 1260–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abakari, G.; Luo, G.; Shao, L.; Abdullateef, Y.; Cobbina, S.J. Effects of biochar on microbial community in bioflocs and gut of Oreochromis niloticus reared in a biofloc system. Aquacult. Int. 2021, 29, 1295–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Chen, J.; Hou, J.; Li, D.; He, X. The effect of different carbon sources on water quality, microbial community and structure of biofloc systems. Aquaculture 2018, 482, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, G.; Li, C.; Deng, Y.; Abubakar, T.M.; Lan, L.; Zhu, S.; Liu, D. Effects of different solid carbon sources on water quality, biofloc quality and gut microbiota of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) larvae. Aquaculture 2018, 495, 919–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.-f.; Wang, A.-l.; Liao, S.-a. Effect of different carbon sources on microbial community structure and composition of ex-situ biofloc formation. Aquaculture 2020, 515, 734492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Zhang, N.; Cai, S.; Tan, H.; Liu, Z. Nitrogen dynamics, bacterial community composition and biofloc quality in biofloc-based systems cultured Oreochromis niloticus with poly-β-hydroxybutyric and polycaprolactone as external carbohydrates. Aquaculture 2017, 479, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinasyiam, A.; Verdegem, M.C.J.; Ekasari, J.; Schrama, J.W.; Kokou, F. Prokaryotic and eukaryotic microbial community dynamics in biofloc systems supplemented with non-starch polysaccharides. Aquaculture 2025, 594, 741396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhu, Z.; Lv, X.; Tan, H.; Liu, W.; Luo, G. Optimizing carbon sources on performance for enhanced efficacy in single-stage aerobic simultaneous nitrogen and phosphorus removal via biofloc technology. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 411, 131347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Li, L.; Dong, X.; Tian, X. Influence of carbon source supplementation on the development of autotrophic nitrification and microbial community composition in biofloc technology systems. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 71, 107215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Huang, F.; Zhao, Y.; Su, H.; Hu, X.; Xu, Y.; Wen, G.; Cao, Y. Carbohydrate addition strategy affects nitrogen dynamics, budget and utilization, and its microbial mechanisms in biofloc-based Penaeus vannamei culture. Aquaculture 2024, 589, 740907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Wen, G.; Su, H.; Xu, Y.; Hu, X.; Cao, Y. Effect of input C/N ratio on bacterial community of water biofloc and shrimp gut in a commercial zero-exchange system with intensive production of Penaeus vannamei. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.-J.; Morris, T.C.; Samocha, T.M. Effects of C/N ratio on biofloc development, water quality, and performance of Litopenaeus vannamei juveniles in a biofloc-based, high-density, zero-exchange, outdoor tank system. Aquaculture 2016, 453, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, A.; Saranya, C.; Sundaram, M.; Vinoth Kannan, S.R.; Das, R.R.; Sathish, S.; Rajesh, P.; Otta, S.K. Carbon: Nitrogen (C:N) ratio level variation influences microbial community of the system and growth as well as immunity of shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) in biofloc based culture system. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2018, 81, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.; Dong, D.; Li, M.; Yang, X.; Song, X.; Li, X. Effects of carbon source addition strategies on water quality, growth performance, and microbial community in shrimp BFT aquaculture systems. Aquaculture 2024, 578, 740027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkuar, N.; Li, L.; Srisapoome, P.; Dong, S.; Tian, X. Application of biodegradable polymers as carbon sources in ex situ biofloc systems: Water quality and shift of microbial community. Aquacult. Res. 2021, 52, 3570–3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanjani, M.H.; Sharifinia, M. Biofloc technology as a promising tool to improve aquaculture production. Rev. Aquacult. 2020, 12, 1836–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, C.C.d.M.; Owatari, M.S.; Schleder, D.D.; Poli, M.A.; Gelsleichter, Y.R.R.; Postai, M.; Kruger, K.E.; Carvalho, F.G.d.; Silva, B.P.P.; Teixeira, B.L.; et al. Identification and characterization of microorganisms potentially beneficial for intensive cultivation of Penaeus vannamei under biofloc conditions: Highlighting Exiguobacterium acetylicum. Aquacult. Res. 2021, 52, 3628–3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, S.M.; Chesti, A.; Rehman, S.; Nautiyal, V.C.; Bhat, I.A.; Ahmad, I. Repurposing and reusing aquaculture wastes through a biosecure microfloc technology. Environ. Res. 2025, 274, 121214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramiro, B.d.O.; Wasielesky, W.; Pimentel, O.A.L.F.; Martin, N.P.S.; Borges, L.d.V.; Krummenauer, D. Different management strategies for artificial substrates on nitrification, microbial composition, and growth of Penaeus vannamei in a super-intensive biofloc system. Aquaculture 2025, 596, 741853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Shi, M.; Huang, X.; Luo, L.; Wang, S.; Zhang, R.; Xu, W.; Ruan, G.; Zhao, Z. The Effect of Artificial Substrate and Carbon Source Addition on Bacterial Diversity and Community Composition in Water in a Pond Polyculture System. Fishes 2024, 9, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparza-Leal, H.M.; Cardozo, A.P.; Wasielesky, W., Jr. Performance of Litopenaeus vannamei postlarvae reared in indoor nursery tanks at high stocking density in clear-water versus biofloc system. Aquacult. Eng. 2015, 68, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, J.K.; Samocha, T.M.; Patnaik, S.; Speed, M.; Gandy, R.L.; Ali, A.-M. Performance of an intensive nursery system for the Pacific white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei, under limited discharge condition. Aquacult. Eng. 2008, 38, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende, P.C.; Schleder, D.D.; Silva, H.V.d.; Henriques, F.M.; Lorenzo, M.A.d.; Seiffert, W.Q.; Andreatta, E.R.; Vieira, F.d.N. Prenursery of the Pacific white shrimp in a biofloc system using different artificial substrates. Aquacult. Eng. 2018, 82, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schveitzer, R.; Lorenzo, M.A.D.; Felipe, D.N.V.; Pereira, S.A.; Mourino, J.L.P.; Seiffert, W.Q.; Andreatta, E.R. Nursery of young Litopenaeus vannamei post-larvae reared in biofloc- and microalgae-based systems. Aquacult. Eng. 2017, 78, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, T.W.; Fleckenstein, L.J.; Ray, A.J. The effects of density and artificial substrate on intensive shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei nursery production. Aquacult. Eng. 2020, 89, 102063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, G.R.d.; Poersch, L.H.; Wasielesky, W., Jr. The quantity of artificial substrates influences the nitrogen cycle in the biofloc culture system of Litopenaeus vannamei. Aquacult. Eng. 2021, 94, 102171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiro-Alcantar, C.; Rivas-Vega, M.E.; Martinez-Porchas, M.; Lizarraga-Armenta, J.A.; Miranda-Baeza, A.; Martinez-Cordova, L.R. Effect of adding vegetable substrates on Penaeus vannamei pre-grown in biofloc system on shrimp performance, water quality and biofloc composition. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res. 2019, 47, 784–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-H.; Luo, T.; Lei, Y.-J.; Kuang, W.-Q.; Zou, W.-S.; Yang, P.-H. Water quality, shrimp growth performance and bacterial community in a reusing-water biofloc system for nursery of Penaeus vananmei rearing under a low salinity condition. Aquacult. Rep. 2021, 21, 100894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.J. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol. 2001, 26, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.-H.; Liao, H.-M.; Lei, Y.-J.; Yang, P.-H. Effects of different carbon sources on growth performance of Litopenaeus vannamei and water quality in the biofloc system in low salinity. Aquaculture 2022, 546, 737239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-H.; Li, C.-Y.; Lei, Y.-J.; Zhou, B.-L.; Kuang, W.-Q.; Zou, W.-S.; Yang, P.-H. Effects of Bacillus strain added as initial indigenous species into the biofloc system rearing Litopenaeus vannamei juveniles on biofloc preformation, water quality and shrimp growth. Aquaculture 2023, 569, 739375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segata, N.; Izard, J.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Miropolsky, L.; Garrett, W.S.; Huttenhower, C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, Y.; Hiraiwa, M.N.; Ito, T.; Itonaga, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Okabe, S. Bacterial community structures in MBRs treating municipal wastewater: Relationship between community stability and reactor performance. Water Res. 2007, 41, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchman, D.L. The ecology of Cytophaga–Flavobacteria in aquatic environments. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2002, 39, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan-Sagastume, F.; Larsen, P.; Nielsen, J.L.; Nielsen, P.H. Characterization of the loosely attached fraction of activated sludge bacteria. Water Res. 2008, 42, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghai, R.; Mizuno, C.M.; Picazo, A.; Camacho, A.; Rodriguez-Valera, F. Metagenomics uncovers a new group of low GC and ultra-small marine Actinobacteria. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Guo, H.; Chen, C.; Huang, X.; Chen, W.; Bao, F.; Liu, W.; Wang, S.; Zhang, D. The bacteria from large-sized bioflocs are more associated with the shrimp gut microbiota in culture system. Aquaculture 2020, 523, 735159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addo, F.G.; Zhang, S.; Manirakiza, B.; Ohore, O.E.; Shudong, Y. The impacts of straw substrate on biofloc formation, bacterial community and nutrient removal in shrimp ponds. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 326, 124727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Ren, W.; Li, L.; Dong, S.; Tian, X. Light and carbon sources addition alter microbial community in biofloc-based Litopenaeus vannamei culture systems. Aquaculture 2020, 515, 734572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-S.; Kim, S.-E.; Kim, S.-J.; Jung, H.-K.; Park, J.; Jeon, Y.J.; Kim, D.-H.; Kang, J.-H.; Kim, K.-H. Effects of wheat flour and culture period on bacterial community composition in digestive tracts of Litopenaeus vannamei and rearing water in biofloc aquaculture system. Aquaculture 2021, 531, 735908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandel, P.P.; Pasternak, Z.; van Rijn, J.; Nahum, O.; Jurkevitch, E. Abundance, diversity and seasonal dynamics of predatory bacteria in aquaculture zero discharge systems. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2014, 89, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, N.V. The use of probiotics in aquaculture. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 119, 917–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Zhang, S.-H.; Yu, X.; Wei, B. Variations of both bacterial community and extracellular polymers: The inducements of increase of cell hydrophobicity from biofloc to aerobic granule sludge. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 6421–6428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manan, H.; Rosland, N.A.; Mat Deris, Z.; Che Hashim, N.F.; Kasan, N.A.; Ikhwanuddin, M.; Fauzan, F.; Suloma, A. 16S rRNA sequences of Exiguobacterium spp. bacteria dominant in a biofloc pond cultured with whiteleg shrimp, Penaeus vannamei. Aquacult. Res. 2022, 53, 2029–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, N.; Surratt, A.; Renukdas, N.; Monico, J.; Egnew, N.; Sinha, A.K. Assessing the feasibility of biofloc technology to largemouth bass Micropterus salmoides juveniles: Insights into their welfare and physiology. Aquaculture 2020, 520, 735008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrapani, S.; Panigrahi, A.; Sundaresan, J.; Mani, S.; Palanichamy, E.; Rameshbabu, V.S.; Krishna, A. Utilization of Complex Carbon Sources on Biofloc System and Its Influence on the Microbial Composition, Growth, Digestive Enzyme Activity of Pacific White Shrimp, Penaeus vannamei Culture. Turk. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2022, 22, trjfas18813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanjani, M.H.; Mozanzadeh, M.T.; Sharifinia, M.; Emerenciano, M.G.C. Biofloc: A sustainable dietary supplement, nutritional value and functional properties. Aquaculture 2023, 562, 738757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, M.T.; Broom, M.; Al-Mur, B.A.; Harbi, M.A.; Ghandourah, M.; Otaibi, A.A.; Haque, M.F. Biofloc technology: Emerging microbial biotechnology for the improvement of aquaculture productivity. Polish J. Microbiol. 2020, 69, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, M.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, X.; Huang, L.; Su, Y.; Yan, Q. The complete genome sequence of Exiguobacterium arabatum W-01 reveals potential probiotic functions. MicrobiologyOpen 2017, 6, e00496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sombatjinda, S.; Wantawin, C.; Techkarnjanaruk, S.; Withyachumnarnkul, B.; Ruengjitchatchawalya, M. Water quality control in a closed re-circulating system of Pacific white shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) postlarvae co-cultured with immobilized Spirulina mat. Aquacult. Int. 2014, 22, 1181–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, A.; Esakkiraj, P.; Jayashree, S.; Saranya, C.; Das, R.R.; Sundaram, M. Colonization of enzymatic bacterial flora in biofloc grown shrimp Penaeus vannamei and evaluation of their beneficial effect. Aquacult. Int. 2019, 27, 1835–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-K.; Song, J.; Rajeev, M.; Kim, S.K.; Kang, I.; Jang, I.-K.; Cho, J.-C. Exploring bacterioplankton communities and their temporal dynamics in the rearing water of a biofloc-based shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) aquaculture system. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 995699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, A.; Esakkiraj, P.; Das, R.R.; Saranya, C.; Vinay, T.N.; Otta, S.K.; Shekhar, M.S. Bioaugmentation of biofloc system with enzymatic bacterial strains for high health and production performance of Penaeus indicus. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Zhao, X.; Cheng, Y.; Jiang, M.; Li, X.; Xue, G. Iron Robustly Stimulates Simultaneous Nitrification and Denitrification Under Aerobic Conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 1404–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, W.; Li, J.; Li, P.; Wang, C.; Cao, Y.; Li, D.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zuo, J. Effects of residual organics in municipal wastewater on hydrogenotrophic denitrifying microbial communities. J. Environ. Sci. 2018, 65, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Xu, B.; Tan, H.; Zhu, S.; Luo, G.; Shitu, A.; Wan, Y. Investigating the conversion from nitrifying to denitrifying water-treatment efficiencies of the biofloc biofilter in a recirculating aquaculture system. Aquaculture 2022, 550, 737817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Li, L.; Dai, Z.; Senbati, Y.; Song, K.; He, X. Aerobic denitrification affects gaseous nitrogen loss in biofloc-based recirculating aquaculture system. Aquaculture 2020, 529, 735686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Ke, H.; Xie, J.; Tan, H.; Luo, G.; Xu, B.; Abakari, G. Characterizing the water quality and microbial communities in different zones of a recirculating aquaculture system using biofloc biofilters. Aquaculture 2020, 529, 735624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullian-Klanian, M.; Quintanilla-Mena, M.; Hau, C.P. Influence of the biofloc bacterial community on the digestive activity of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquaculture 2023, 562, 738774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, H.N.F.; Ayuni, G.N.; Mat, A.N.; Noraznawati, I.; Azman, K.N. Description of novel marine bioflocculant-producing bacteria isolated from biofloc of Pacific whiteleg shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei culture ponds. bioRxiv 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chang, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; Li, J. Water quality, microbial community and shrimp growth performance of Litopenaeus vannamei culture systems based on biofloc or biofilters. Aquacult. Res. 2021, 52, 6656–6666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Roy, S.; Behera, B.K.; Swain, H.S.; Das, B.K. Biofloc Microbiome with bioremediation and health benefits. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 741164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, M.; Liao, S.; Wang, B.; Zeng, J.; Fang, J.; Wang, A.; Ye, J. Effect of carbon source and C/N ratio on microbial community and function in ex situ biofloc system with inoculation of nitrifiers and aerobic denitrifying bacteria. Aquacult. Res. 2021, 52, 4498–4511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansel, B. Morphology, composition and aggregation mechanisms of soft bioflocs in marine snow and activated sludge: A comparative review. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 205, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Luo, G.; Chen, W.; Tan, H.; Wu, S.; Zhang, N.; Yu, Y. Effect of no carbohydrate addition on water quality, growth performance and microbial community in water-reusing biofloc systems for tilapia production under high-density cultivation. Aquacult. Res. 2018, 49, 2446–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, C.d.S.; Rodiles, A.; Marques, M.R.F.; Merrifield, D.L. White spot syndrome virus (WSSV) disturbs the intestinal microbiota of shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) reared in biofloc and clear seawater. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 8007–8023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabarrok, M.; Seyfabadi, J.; Salehi Jouzani, G.; Younesi, H. Comparison between recirculating aquaculture and biofloc systems for rearing juvenile common carp (Cyprinus carpio): Growth performance, haemato-immunological indices, water quality and microbial communities. Aquacult. Res. 2020, 51, 4881–4892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angahar, L.T. Applications of Probiotics in Aquaculture. Am. J. Curr. Microbiol. 2016, 4, 66–79. [Google Scholar]

- Ninawe, A.S.; Selvin, J. Probiotics in shrimp aquaculture: Avenues and challenges. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 35, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newaj-Fyzul, A.; Al-Harbi, A.H.; Austin, B. Review: Developments in the use of probiotics for disease control in aquaculture. Aquaculture 2014, 431, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Dai, Z.; Senbati, Y.; Li, L.; Song, K.; He, X. Aerobic denitrification microbial community and function in zero-discharge recirculating aquaculture system using a single biofloc-based suspended growth reactor: Influence of the Carbon-to-Nitrogen Ratio. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Guo, Z.; Tang, Y.; Kuang, J.; Duan, Y.; Lin, H.; Jiang, S.; Shu, H.; Huang, J. Effects on development and microbial community of shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei larvae with probiotics treatment. AMB Express 2020, 10, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Xu, Y.; Huang, X.; Hu, X.; Xu, Y.; Su, H.; Li, Z.; Yang, K.; Wen, G.; Cao, Y. Addition of algicidal bacterium CZBC1 and molasses to inhibit cyanobacteria and improve microbial communities, water quality and shrimp performance in culture systems. Aquaculture 2019, 502, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luis-Villaseñor, I.E.; Voltolina, D.; Audelo-Naranjo, J.M.; Pacheco-Marges, M.R.; Herrera-Espericueta, V.E.; Romero-Beltrán, E. Effects of Biofloc Promotion on Water Quality, Growth, Biomass Yield and Heterotrophic Community in Litopenaeus vannamei (Boone, 1931) Experimental Intensive Culture. Science Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 14, 3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, G.S.; Santos, D.; Schmachtl, F.; Machado, C.; Fernandes, V.; Boegner, M.; Schleder, D.D.; Seiffert, W.Q.; Vieira, F.N. Heterotrophic, chemoautotrophic and mature approaches in biofloc system for Pacific white shrimp. Aquaculture 2021, 533, 736099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta-Rabago, J.A.; Martinez-Porchas, M.; Miranda-Baeza, A.; Nieves-Soto, M.; Rivas-Vega, M.E.; Martinez-Cordova, L.R. Addition of commercial probiotic in a biofloc shrimp farm of Litopenaeus vannamei during the nursery phase: Effect on bacterial diversity using massive sequencing 16S rRNA. Aquaculture 2019, 502, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Córdova, L.R.; Francisco, V.A.; Estefanía, G.V.; Ortíz-Estrada, á.M.; Porchas-Cornejo, M.A.; Asunción, L.L.; Marcel, M.P. Amaranth and wheat grains tested as nucleation sites of microbial communities to produce bioflocs used for shrimp culture. Aquaculture 2018, 497, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.A.; Poli, M.A.; Legarda, E.C.; Pinheiro, I.C.; Siqueira Carneiro, R.F.; Pereira, S.A.; Martins, M.L.; Goncalves, P.; Schleder, D.D.; Vieira, F.d.N. Heterotrophic and mature biofloc systems in the integrated culture of Pacific white shrimp and Nile tilapia. Aquaculture 2020, 514, 734517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schveitzer, R.; Fonseca, G.; Orteney, N.; Temistocles Menezes, F.C.; Thompson, F.L.; Thompson, C.C.; Gregoracci, G.B. The role of sedimentation in the structuring of microbial communities in biofloc-dominated aquaculture tanks. Aquaculture 2020, 514, 734493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Li, Y.; Jiang, F.; Hu, Z.; Zheng, Y. Performance of Platymonas and microbial community analysis under different C/N ratio in biofloc technology aquaculture system. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 43, 102257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krummenauer, D.; Poersch, L.; Romano, L.A.; Lara, G.R.; Encarnacao, P.; Wasielesky, W., Jr. The Effect of Probiotics in a Litopenaeus vannamei Biofloc Culture System Infected with Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Appl. Aquacult. 2014, 26, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Luo, G.-z.; Meng, H.; Tan, F.Y. Effect of the particle size on the ammonia removal rate and the bacterial community composition of bioflocs. Aquacult. Eng. 2019, 86, 102001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Liao, S.; Liu, D.; Bai, H.; Wang, A.; Ye, J. The combination use of Candida tropicalis HH8 and Pseudomonas stutzeri LZX301 on nitrogen removal, biofloc formation and microbial communities in aquaculture. Aquaculture 2019, 500, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariana, P.; André, G.; Felipe, V.; Walter, S.; Evelyne, B.; Rafael, R.; Luciane, P. Exploring the Impact of the Biofloc Rearing System and an Oral WSSV Challenge on the Intestinal Bacteriome of Litopenaeus vannamei. Microorganisms 2018, 6, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhu, S.; Liu, D.; Ye, Z. Effect of the C/N ratio on inorganic nitrogen control and the growth and physiological parameters of tilapias fingerlings, Oreochromis niloticu reared in biofloc systems. Aquacult. Res. 2018, 49, 2429–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Shan, D.; Li, G.; Li, X.; Tian, R.; He, J.; Shao, Z. Prokaryotic communities vary with floc size in a biofloc-technology based aquaculture system. Aquaculture 2020, 529, 735632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona, E.; Gueguen, Y.; Magre, K.; Lorgeoux, B.; Piquemal, D.; Pierrat, F.; Noguier, F.; Saulnier, D. Bacterial community characterization of water and intestine of the shrimp Litopenaeus stylirostris in a biofloc system. BMC Microbiol. 2016, 16, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhoff, J.F. Rhodobacter. In Bergey’s Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas, R.; Velázquez, E.; Willems, A.; Vizcaíno, N.; Subba-Rao, N.S.; Mateos, P.F.; Gillis, M.; Dazzo, F.B.; Martínez-Molina, E. A new species of Devosia that forms a unique nitrogen-fixing root-nodule symbiosis with the aquatic legume Neptunia natans (L.f.) Druce. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 5217–5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gou, J.; Hong, C.U.; Deng, M.; Chen, J.; Hou, J.; Li, D.; He, X. Effect of carbon to nitrogen ratio on water quality and community structure evolution in suspended growth bioreactors through biofloc technology. Water 2019, 11, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zhang, D.; Qin, J.; Wang, Y. The effect of C/N ratio on bacterial community and water quality in a mussel-fish integrated system. Aquacult. Res. 2018, 49, 1699–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Xu, Y.; Su, H.; Hu, X.; Xu, Y.; Li, Z.; Wen, G.; Cao, Y. Production performance, inorganic nitrogen control and bacterial community characteristics in a controlled biofloc-based system for indoor and outdoor super-intensive culture of Litopenaeus vannamei. Aquaculture 2021, 531, 735749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Maixin, L.U.; Mengmeng, Y.I.; Jianmeng, C.; Fengying, G. The commensal microbiota structure of Nile tilapia(Oreochromis niloticus)skin and gill surfaces and preliminary study of their implications on tilapia health status. J. Fish. China. 2017, 41, 1148–1157. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Wang, G.; Zhang, K.; Gong, W.; Yu, E.; Tian, J.; Xie, J.; Yu, D. Epizootic ulcerative syndrome causes cutaneous dysbacteriosis in hybrid snakehead (Channa maculata ♀ × Channa argus ♂). PeerJ 2019, 7, e6674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preena, P.G.; Dharmaratnam, A.; Swaminathan, T.R. Antimicrobial Resistance analysis of Pathogenic Bacteria Isolated from Freshwater Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Cultured in Kerala, India. Curr. Microbiol. 2020, 77, 3278–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maida, I.; Fondi, M.; Papaleo, M.C.; Perrin, E.; Orlandini, V.; Emiliani, G.; de Pascale, D.; Parrilli, E.; Tutino, M.L.; Michaud, L.; et al. Phenotypic and genomic characterization of the Antarctic bacterium Gillisia sp. CAL575, a producer of antimicrobial compounds. Extremophiles 2014, 18, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasan, N.A.; Yee, C.S.; Manan, H.; Ideris, A.R.A.; Kamaruzzan, A.S.; Waiho, K.; Lam, S.S.; Mahari, W.A.W.; Ikhwanuddin, M.; Suratman, S.; et al. Study on the implementation of different biofloc sedimentable solids in improving the water quality and survival rate of mud crab, Scylla paramamosain larvae culture. Aquacult. Res. 2021, 52, 4807–4815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-H.; Li, C.-Y.; Liang, T.; Lei, Y.-J.; Yang, P.-H.; Wu, M.-X. Effects of carbon-to-nitrogen ratio (C:N) on water quality and growth performance of Litopenaeus vannamei (Boone, 1931) in the biofloc system with a salinity of 5‰. Aquacult. Res. 2022, 53, 5287–5299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

, response variables (bacterial genera); only the twenty best-fitted genera were shown due to the capacity limitation of the biplot.

, response variables (bacterial genera); only the twenty best-fitted genera were shown due to the capacity limitation of the biplot.  , factor explanatory variable (substrate), accounted for 18.00% of the total variation in genus composition.

, factor explanatory variable (substrate), accounted for 18.00% of the total variation in genus composition.  , water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28 d from sB treatment.

, water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28 d from sB treatment.  , water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28 d from cB treatment.

, water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28 d from cB treatment.

, response variables (bacterial genera); only the twenty best-fitted genera were shown due to the capacity limitation of the biplot.

, response variables (bacterial genera); only the twenty best-fitted genera were shown due to the capacity limitation of the biplot.  , factor explanatory variable (substrate), accounted for 18.00% of the total variation in genus composition.

, factor explanatory variable (substrate), accounted for 18.00% of the total variation in genus composition.  , water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28 d from sB treatment.

, water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28 d from sB treatment.  , water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28 d from cB treatment.

, water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28 d from cB treatment.

, response variables (alpha diversity indices).

, response variables (alpha diversity indices).  , factor explanatory variable (substrate), accounting for 26.50% of the total variation in alpha diversity.

, factor explanatory variable (substrate), accounting for 26.50% of the total variation in alpha diversity.  , water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28 d from sB treatment.

, water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28 d from sB treatment.  , water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28d from cB treatment.

, water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28d from cB treatment.

, response variables (alpha diversity indices).

, response variables (alpha diversity indices).  , factor explanatory variable (substrate), accounting for 26.50% of the total variation in alpha diversity.

, factor explanatory variable (substrate), accounting for 26.50% of the total variation in alpha diversity.  , water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28 d from sB treatment.

, water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28 d from sB treatment.  , water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28d from cB treatment.

, water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28d from cB treatment.

, response variables (water parameters).

, response variables (water parameters).  , explanatory variables ((a), genus abundances; (b), bacterial alpha diversity indices).

, explanatory variables ((a), genus abundances; (b), bacterial alpha diversity indices).  , supplementary factor explanatory variable (substrate).

, supplementary factor explanatory variable (substrate).  , water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28 d from sB treatment.

, water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28 d from sB treatment.  , water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28 d from cB treatment. BFV, biofloc volume; BTN, total nitrogen contained in biofloc; CAK, carbonate alkalinity; DTN, dissolved total nitrogen in water; TAN, total ammonia nitrogen; TSS, total suspended solids; WTN, whole total nitrogen in water body.

, water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28 d from cB treatment. BFV, biofloc volume; BTN, total nitrogen contained in biofloc; CAK, carbonate alkalinity; DTN, dissolved total nitrogen in water; TAN, total ammonia nitrogen; TSS, total suspended solids; WTN, whole total nitrogen in water body.

, response variables (water parameters).

, response variables (water parameters).  , explanatory variables ((a), genus abundances; (b), bacterial alpha diversity indices).

, explanatory variables ((a), genus abundances; (b), bacterial alpha diversity indices).  , supplementary factor explanatory variable (substrate).

, supplementary factor explanatory variable (substrate).  , water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28 d from sB treatment.

, water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28 d from sB treatment.  , water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28 d from cB treatment. BFV, biofloc volume; BTN, total nitrogen contained in biofloc; CAK, carbonate alkalinity; DTN, dissolved total nitrogen in water; TAN, total ammonia nitrogen; TSS, total suspended solids; WTN, whole total nitrogen in water body.

, water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28 d from cB treatment. BFV, biofloc volume; BTN, total nitrogen contained in biofloc; CAK, carbonate alkalinity; DTN, dissolved total nitrogen in water; TAN, total ammonia nitrogen; TSS, total suspended solids; WTN, whole total nitrogen in water body.

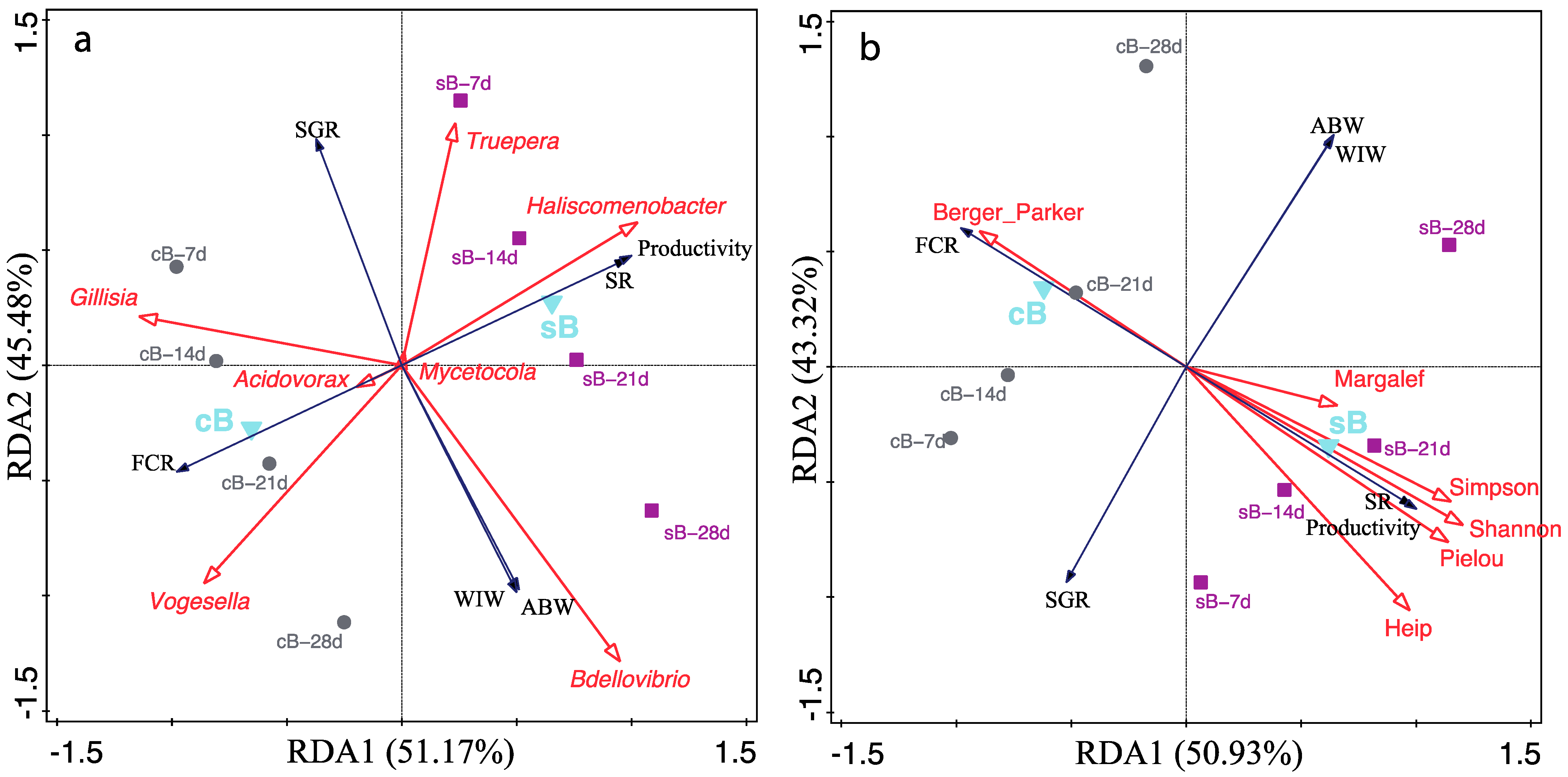

, response variables (zootechnical indices).

, response variables (zootechnical indices).  , explanatory variables ((a), genera abundances; (b), bacterial alpha diversity indices).

, explanatory variables ((a), genera abundances; (b), bacterial alpha diversity indices).  , supplementary factor explanatory variable (substrate).

, supplementary factor explanatory variable (substrate).  , water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28 d from sB treatment.

, water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28 d from sB treatment.  , water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28 d from cB treatment. ABW, average body weight; FCR, feed conversion ratio; SGR, specific growth rate; SR, survival rate; WIW, weekly increment of body weight.

, water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28 d from cB treatment. ABW, average body weight; FCR, feed conversion ratio; SGR, specific growth rate; SR, survival rate; WIW, weekly increment of body weight.

, response variables (zootechnical indices).

, response variables (zootechnical indices).  , explanatory variables ((a), genera abundances; (b), bacterial alpha diversity indices).

, explanatory variables ((a), genera abundances; (b), bacterial alpha diversity indices).  , supplementary factor explanatory variable (substrate).

, supplementary factor explanatory variable (substrate).  , water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28 d from sB treatment.

, water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28 d from sB treatment.  , water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28 d from cB treatment. ABW, average body weight; FCR, feed conversion ratio; SGR, specific growth rate; SR, survival rate; WIW, weekly increment of body weight.

, water samples at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, and 28 d from cB treatment. ABW, average body weight; FCR, feed conversion ratio; SGR, specific growth rate; SR, survival rate; WIW, weekly increment of body weight.

| Phylum | Genus | Absolute Abundance (105 Copies of Genome mL−1) | p-Value (Repeated-Measures ANOVA) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cB | sB | Substrate | Time | interaction | ||

| Actinobacteria | 23.81 ± 7.15 | 10.91 ± 3.74 | <0.001 | 0.027 | 0.008 | |

| Candidatus aquiluna | 0.19 ± 0.05 | 0.49 ± 0.22 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Microbacterium | 0.85 ± 0.23 | 2.13 ± 0.69 | 0.001 | 0.019 | 0.038 | |

| Mycobacterium | 3.22 ± 1.25 | 1.85 ± 0.49 | 0.021 | 0.003 | 0.001 | |

| Bacteroidetes | 40.98 ± 12.81 | 41.71 ± 34.45 | 0.948 | 0.029 | 0.183 | |

| Adhaeribacter | 0.10 ± 0.05 | 2.89 ± 1.68 | 0.041 | 0.041 | 0.038 | |

| Aequorivita | 2.14 ± 0.65 | 0.32 ± 0.16 | <0.001 | 0.012 | 0.016 | |

| Flavobacterium | 1.36 ± 0.63 | 0.59 ± 0.12 | 0.002 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Haliscomenobacter | 0.07 ± 0.03 a | 0.65 ± 0.15 b | 0.005 | 0.046 | 0.085 | |

| Muricauda | 3.00 ± 1.43 | 0.71 ± 0.22 | 0.027 | 0.016 | 0.039 | |

| Chloroflexi | 6.88 ± 5.11 | 1.15 ± 0.53 | <0.001 | 0.006 | 0.006 | |

| Firmicutes | 7.18 ± 4.21 | 10.93 ± 6.39 | 0.012 | 0.009 | <0.001 | |

| Exiguobacterium | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.84 ± 0.3 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.002 | |

| Planococcus | 1.08 ± 0.36 | 7.73 ± 2.68 | <0.001 | 0.019 | 0.037 | |

| Planomicrobium | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 1.15 ± 0.45 | 0.001 | 0.013 | 0.021 | |

| Planctomycetes | 14.98 ± 4.35 | 21.86 ± 11.38 | 0.096 | 0.071 | 0.100 | |

| Planctomyces | 0.35 ± 0.07 | 3.82 ± 2.11 | 0.043 | 0.043 | 0.040 | |

| Proteobacteria | 73.82 ± 13.09 | 82.51 ± 39.86 | 0.389 | 0.064 | 0.209 | |

| Amaricoccus | 9.33 ± 4.17 | 2.88 ± 1.27 | 0.031 | 0.013 | 0.080 | |

| Anaerospora | 0.42 ± 0.19 a | 1.07 ± 0.31 b | 0.033 | 0.026 | 0.554 | |

| Bdellovibrio | 0.80 ± 0.17 | 1.01 ± 0.21 | 0.079 | <0.001 | 0.566 | |

| Brevundimonas | 13.45 ± 4.41 | 3.02 ± 1.47 | <0.001 | 0.007 | 0.007 | |

| Halomonas | 1.85 ± 0.54 | 0.37 ± 0.15 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Hyphomonas | 3.92 ± 1.06 | 2.01 ± 0.65 | 0.034 | 0.018 | 0.348 | |

| Lutibacterium | 0.44 ± 0.12 a | 1.66 ± 0.38 b | 0.008 | 0.038 | 0.249 | |

| Lysobacter | 0.27 ± 0.07 | 5.53 ± 2.65 | 0.020 | 0.051 | 0.049 | |

| Paracoccus | 3.98 ± 1.08 | 8.66 ± 2.77 | <0.001 | 0.038 | 0.031 | |

| Pseudomonas | 2.99 ± 0.51 | 3.16 ± 1.52 | 0.834 | 0.070 | 0.029 | |

| Psychrobacter | 0.40 ± 0.06 | 6.31 ± 3.07 | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.009 | |

| Rhodobacter | 5.49 ± 1.26 | 5.39 ± 1.92 | 0.931 | 0.034 | 0.068 | |

| Verrucomicrobia | 1.15 ± 0.45 a | 7.61 ± 2.86 b | 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.072 | |

| Luteolibacter | 0.16 ± 0.05 | 1.59 ± 0.57 | <0.001 | 0.019 | 0.030 | |

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Jaccard Index | Permutations | Pseudo-F | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cB | cB | 0.761 ± 0.208 | - | - | - |

| sB | sB | 0.768 ± 0.211 | - | - | - |

| cB | sB | 0.941 ± 0.007 | 999 | 3.96 | 0.001 |

| Index | Treatments | p-Value (Repeated-Measures ANOVA) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cB | sB | Substrate | Time | Interaction | |

| Shannon | 6.14 ± 0.18 | 6.77 ± 0.07 | 0.002 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Margalef | 343.9 ± 22.0 | 387.7 ± 28.0 | 0.367 | 0.007 | 0.471 |

| Heip | 0.013 ± 0.001 | 0.018 ± 0.001 | 0.026 | 0.012 | 0.544 |

| Pielou | 0.493 ± 0.012 | 0.538 ± 0.003 | 0.024 | <0.001 | 0.016 |

| Berger–Parker | 0.193 ± 0.020 | 0.152 ± 0.014 | 0.098 | 0.002 | 0.676 |

| Simpson | 0.927 ± 0.010 | 0.955 ± 0.003 | 0.043 | <0.001 | 0.127 |

| Parameters | Treatments | p-Value (Repeated-Measures ANOVA) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cB | sB | Substrate | Time | Interaction | |

| TSS (mg L−1) | 148.5 ± 31.3 a | 491.3 ± 150.2 b | 0.009 | 0.116 | 0.594 |

| WTN (mg L−1) | 76.8 ± 11.2 | 76.3 ± 9.6 | 0.057 | <0.001 | 0.013 |

| DTN (mg L−1) | 13.0 ± 2.6 | 14.7 ± 3.6 | 0.890 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| BTN (mg L−1) | 63.8 ± 9.3 | 61.6 ± 12.5 | 0.052 | <0.001 | 0.085 |

| TAN (mg L−1) | 0.55 ± 0.25 | 0.43 ± 0.06 | 0.010 | 0.227 | 0.002 |

| Nitrite (mg L−1) | 0.37 ± 0.28 | 0.10 ± 0.03 | 0.352 | 0.348 | 0.342 |

| Nitrate (mg L−1) | 0.51 ± 0.14 | 0.56 ± 0.08 | 0.924 | 0.274 | 0.252 |

| BFV (mL L−1) | 8.8 ± 2.3 | 8.3 ± 2.3 | 0.044 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Turbidity (NTU) | 111.9 ± 56.3 | 299.5 ± 92.0 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.059 |

| CAK (mg L−1 CaCO3) | 373.7 ± 12.4 b | 306.5 ± 51.7 a | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Temperature (°C) | 26.9 ± 0.7 | 27.1 ± 0.6 | 0.656 | <0.001 | 0.012 |

| pH | 7.20 ± 0.14 | 7.11 ± 0.03 | 0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| Dissolved oxygen (mg L−1) | 5.85 ± 0.32 | 5.63 ± 0.59 | 0.215 | <0.001 | 0.764 |

| Parameters | cB | sB | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Final ABW (g) | 0.36 ± 0.04 | 0.40 ± 0.03 | 0.596 |

| SR (%) | 81.0 ± 7.1 | 96.3 ± 3.6 | 0.011 |

| FCR | 0.98 ± 0.08 | 0.76 ± 0.06 | 0.044 |

| WIW (g week−1) | 0.090 ± 0.014 | 0.099 ± 0.008 | 0.652 |

| SGR (% d−1) | 17.7 ± 0.5 | 18.1 ± 0.4 | 0.581 |

| Productivity (kg m−3) | 1.14 ± 0.09 | 1.54 ± 0.12 | 0.029 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, H.-H.; Cheng, C.; Guo, L.-L.; Zou, W.-S.; Lei, Y.-J.; Kuang, W.-Q.; Zhou, B.-L.; Yang, P.-H.; Li, C.-Y. Effects of Shifts in Bacterial Community on Improving Water Quality and Growth Performance of Pacific Whiteleg Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) in Biofloc Systems. Fishes 2025, 10, 626. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120626

Huang H-H, Cheng C, Guo L-L, Zou W-S, Lei Y-J, Kuang W-Q, Zhou B-L, Yang P-H, Li C-Y. Effects of Shifts in Bacterial Community on Improving Water Quality and Growth Performance of Pacific Whiteleg Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) in Biofloc Systems. Fishes. 2025; 10(12):626. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120626

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Hai-Hong, Chao Cheng, Li-Li Guo, Wan-Sheng Zou, Yan-Ju Lei, Wei-Qi Kuang, Bo-Lan Zhou, Pin-Hong Yang, and Chao-Yun Li. 2025. "Effects of Shifts in Bacterial Community on Improving Water Quality and Growth Performance of Pacific Whiteleg Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) in Biofloc Systems" Fishes 10, no. 12: 626. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120626

APA StyleHuang, H.-H., Cheng, C., Guo, L.-L., Zou, W.-S., Lei, Y.-J., Kuang, W.-Q., Zhou, B.-L., Yang, P.-H., & Li, C.-Y. (2025). Effects of Shifts in Bacterial Community on Improving Water Quality and Growth Performance of Pacific Whiteleg Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) in Biofloc Systems. Fishes, 10(12), 626. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120626