Abstract

The application of alizarin dye for the marking of fish is a widely adopted practice in post-stocking monitoring programmes. Nevertheless, concerns regarding the welfare implications of alizarin staining persist. The present study conclusively demonstrated that ARS dye exerts instantaneous and protracted deleterious effects on the physiological parameters (gill ventilation frequency, homeostasis in the gut microbiota, total number of erythrocytes and leukocytes) and body fitness (total length, weight and Fulton’s condition factor) of S. trutta fry. The validity of the dye-marked fish stocking effectiveness studies is called into question by these findings.

Key Contribution:

This study demonstrates that Alizarin Red S (ARS) marking of Salmo trutta fry induces immediate physiological stress (increased gill ventilation frequency and gut microbiota imbalance) and delayed fitness impairments (reduced growth, lower condition factor, and decreased survival over seven months), with no long-term hematological alterations. ARS marks were fully retained after seven months (100% mark retention), confirming the dye’s long-term marking efficacy; however, the observed physiological and fitness costs highlight the need for caution when using ARS in fish stocking programs.

1. Introduction

The decline in salmonids fish stocks in the Baltic Sea region is a serious concern [1]. Within this group, Salmo trutta (Linnaeus, 1758) is a key cold-water salmonid widely distributed in European rivers and streams, where it often functions as a top or near-top predator and a flagship indicator of ecological integrity [2,3]. Its strict requirements for cool, well-oxygenated and structurally complex habitats make S. trutta particularly sensitive to hydromorphological alteration, fragmentation and warming, so that changes in its abundance frequently signal broader degradation of salmonid river ecosystems [4]. At the same time, S. trutta is one of the most culturally and economically important freshwater fishes in Europe, supporting high-value recreational fisheries and being the focus of extensive stocking and restoration programmes, including in the Baltic Sea region [5,6]. Robust tools for monitoring stocked S. trutta cohorts are therefore critical both for evaluating management interventions and for conserving the ecological functions provided by this species. Salmonid restocking has been implemented as a standard management practice in many countries for more than half a century [7,8,9]. To ensure optimal outcomes and to evaluate the efficacy of interventions, it is imperative that every stocking strategy incorporates a post-stocking monitoring programme [10]. At the scale required for salmonid restocking programs, practical marking options include otolith thermal marking, fluorochrome marking (e.g., oxytetracycline, calcein, alizarin compounds) and, in some contexts, natural otolith chemical signatures; each differs scalability, detectability and regulatory constrains [10,11,12]. However, the number of adequate post-stocking evaluations of salmonids remains limited. One of the reasons for the inadequacy of post-stocking assessment is the lack of a simple and cost-effective fish-marking technique that could be easily applied on a mass scale [13,14]. Recent syntheses have emphasized the existence of mass-marking methods capable of handling millions of juveniles at low cost. Nevertheless, these methods have been adopted unevenly across programmes, resulting in gaps to evaluation [15,16]. A promising method for mass fish-marking is otolith dying with Alizarin Red S (ARS), which has become one of the most widely applied methods in practice [16,17,18]. ARS is a fluorochrome that complexes with calcium and is incorporated into calcified tissues (notably otoliths), yielding persistent fluorescent marks detectable by microscopy [12,19]. Multi-month to multi-year ARS retention has been reported across taxa, supporting its utility for cohort identification in stocking assessments [20,21,22]. However, concerns have been raised regarding the welfare of fish marked with ARS, as well as the retention and detectability of the ARS mark [18,20,23]. Evidence on fitness impacts is mixed: several operational studies found negligible acute mortality or growth effects at recommended concentration, whereas others have explicitly evaluated potential sub-lethal responses in sensitive early stages—such as altered growth, survival or behavior—under specific immersion protocols [13,14,20,22,24]. Previous studies, including that of Lejk and Radtke [20], have mainly focused on evaluating ARS mark visibility and long-term retention in otoliths under field conditions. Reported detection success commonly exceeds 90% within the first-year post-marking and can remain high over multiple years in some species, although performance varies with life stage, concertation, and stocking practices [21,22]. However, little is known about the potential physiological or microbiological consequences of ARS exposure during marking, which could affect fish welfare and post-release performance. If such dye-related effects are not recognized, differences in growth or survival between marked and unmarked fish may be mistakenly attributed to hatchery origin or management actions, potentially biasing evaluations of stocking programmes. This gap is notable given the central roles of the teleost gut microbiome in digestion, xenobiotic, metabolism, immune homeostasis and growth, and the sensitivity of microbial communities to handling and chemical stressors [25,26,27]. The present study therefore expands upon earlier work by investigating both immediate and delayed biological responses to ARS, providing a toxicological and microbiological perspective that has not been previously addressed. By combining acute stress indicators, microbiome-related endpoints, growth and blood parameters with mark-retention checks, this study directly addresses priorities highlighted in recent syntheses on mass-marking optimization and fish microbiome research [21,28].

The present study, from a toxicological perspective, aims to evaluate whether exposure to the dye induces instant measurable adverse effects in S. trutta fry, focusing on potential physiological responses, such as changes in gill ventilation frequency, and microbiological responses, such as alterations in gut microbiota. Furthermore, to reveal the prolonged (delayed) effects of ARS dye on S. trutta fry fitness, we examined ARS exposed fish growth, fitness, and blood parameters within their first year (7 months) in a recirculating aquaculture system (RAS). Additionally, we assessed ARS mark retention and its detectability after 7 months post-treatment to evaluate the durability and effectiveness of the dyeing technique over an extended period. Situating these endpoints within the broader marking toolkit (thermal, oxytetracycline, calcein) helps interpret trade-offs between practicality, detectability and potential sub-lethal costs for stocking programs [10,29].

2. Materials and Methods

Salmo trutta fry were obtained from the state salmonid hatchery. To ensure the lowest possible genetic variation of the fish used in the experiment, the entire amount of S. trutta fry was derived from a single breeding pair (consisting of one male and one female) collected from the wild spawner stock.

Prior to the marking procedures, the fish were acclimated for two days period in flow-through (minimum flow rate 1 L/1 g of their wet body mass per day) 1 m3 tanks half filled with aerated deep-well water, at a density of 150 individuals per tank, under controlled conditions: water temperature 12 ± 1 °C, pH ~8.1, dissolved oxygen ~9.6 mg O2/L, and a natural day/night photoperiod. The mean values the total length (TL), total weight (W) and Fulton condition factor (KF) of the transferred fish were as follows: TL = 49.7 ± 0.4 mm; W = 1.1 ± 0.2 g, and KF = 0.89 ± 0.08 (Table 1).

Table 1.

The measurements of Salmo trutta fry growth after 7 months post-treatment: number of measured specimens within a group (N); total fish length (TL, mm); total weight (Q, g); Fulton condition factor (KF).

The experiment was conducted in two stages to assess the effects of ARS on S. trutta fry and juveniles. In the first stage, the instant acute toxicity of ARS dying on fish fry was tested. In the second stage, the prolonged effects of ARS marks in juveniles were evaluated.

For the assessment of the instant acute toxicity of ARS dying on the fish fry physiology and gut microbiota a 24-h exposure was applied. Although marking procedures usually involve a 3-h bath, a 24-h exposure was applied to evaluate possible toxic effects of prolonged contact. Fry (50 days post-hatching) were exposed to 100 mg/L of Alizarin Red S (ARS; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MI, USA) for 24 h using aerated deep-well water (pH 8.0). The pH shift after adding ARS was insignificant. The experiment was conducted in glass beakers (500 mL volume) with three replicates (10 individuals in each) per treatment group in a climate chamber (PGC-660, Bronson, Zaltbommel, the Netherlands) under static conditions (ISO 7346-1:1996) [30]. In order to ensure that the concentration of ARS remained consistent throughout the exposure period, it was necessary to cease water exchange during fish exposure to ARS. However, water aeration was fully maintained throughout the entire dying period. Consequently, the dissolved oxygen level was maintained at approximately 10.8 mg O2/L during the entire dying period. Fish incubated in the same deep-well water and environmental conditions, but without the addition of ARS, served as controls. After the 24-h exposure, fish mortality and gill ventilation frequency (GVF; counts·min−1) were recorded. GVF was evaluated in 10 individuals per replicate from both the treatment and control groups during 15-s observation intervals.

To analyse the gut cultivable microbiota, fish from three replicates of each group (control and ARS, 100 mg/L) were aseptically dissected, and the contents of the midgut and distal intestine were collected. All selected fish had been euthanized by a blow to the head following international, national, and institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals (Directive 2010/63/EU; LT 61-13-005) before the dissection. The homogenates of three fish guts from each replicate were pooled to minimize individual variations and then serially diluted (1:10) in Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS, pH 7.3, Oxoid, Hampshire, United Kingdom). 100 µL of each dilution (from 10−4 to 10−8) was spread on Tryptone Soya Agar (TSA, Oxoid, Hampshire, United Kingdom) plates in triplicate. The plates were then incubated at 15 °C for 96 h, after which the colony forming units (CFU/g) were counted and expressed as CFU/g (mean ± SD).

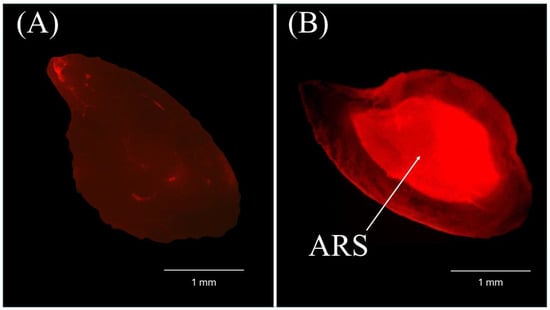

In the second stage, 150 individuals of S. trutta fry were marked applying the technique described by Caudron & Champigneulle [23,31]. The subsequent analyses focused on evaluating ARS marking success and its potential physiological responses on fish juveniles under prolonged experimental conditions. We marked 150 S. trutta fry in a single batch by immersing them in 100 mg/L ARS for 3 h. During the immersion process, the fish were maintained within a 0.6 m3 tank that was filled with 400 L of aerated deep-well water. The remaining 150 subjects, not subjected to the ARS marking process, were designated as the control group. Following a 3 h acclimation period, the fish transferred into 1 m3 flow-through tanks (minimum flow rate: 1 L/1 g of wet body mass per day) that were half-filled with aerated deep-well water. The tanks were maintained under controlled conditions, with temperature set at 12 ± 1 °C, pH ~8.1, dissolved oxygen ~9.6 mg O2/L, and a natural day/night photoperiod for a period of 7 months post-treatment. The fish were fed commercial trout feed (ALLER PLATINUM, Aller Aqua A/S, Christiansfeld, Denmark) daily (in the morning), with a daily feed intake of 1% of the fish’s wet body weight. Fish mortality was observed daily. After a period of 7 months, the fish were measured and weighed in order to assess any significant differences in total length (TL), weight (W), and Fulton’s condition factor (KF) between the marked and non-marked S. trutta individuals. Blood samples were collected in order to analyse erythrocyte and leukocyte counts. Blood cell counts were evaluated in each 20 individuals from both the treatment and control groups. All animal procedures were carried out in accordance with the Directive 2010/63/EU Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Lithuanian State Food Veterinary Service (licence no. G2-168). In addition, 10 individuals from each group (20 in total; ARS-treated and control) were selected in order to verify ARS mark recognition in otoliths. After selected fish specimens had been euthanized by a blow to the head the otoliths were removed and then cleaned, desiccated, placed on thin glass slides and kept in the dark until microscopic (Optika B-600TiFL, Optika, Ponteranica, Italy) examination (Figure 1). The presence of ARS marks in fish otoliths was detected under a fluorescence microscope with a magnification power of 4 x. This microscope was equipped with green (λex = 560 − 595 nm and λem = 645 nm) filters.

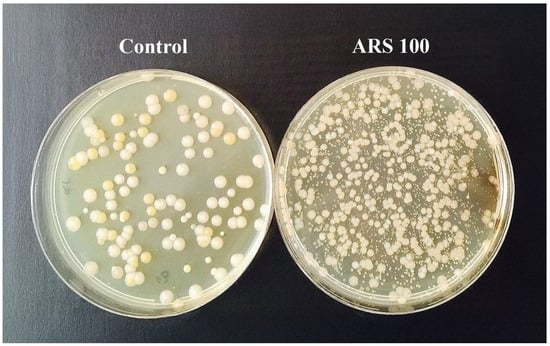

Figure 1.

General appearance of Salmo trutta gut viable bacterial colonies grown on TSA agar plates after 96 h of incubation at 15 °C: control and ARS-exposed group (100 mg/L) after 10−5 dilutions.

The distribution of TL, W, and KF was found to be normal, as confirmed by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests. Because these variables met the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances, parametric tests were applied. Independent Student’s t-tests were performed to compare the ARS-exposed and control fish groups. The mortality rate between the two groups was then subjected to a Chi-squared test. For variables (gill ventilation frequency and blood cell counts) that did not meet the assumption of normality, the non-parametric Kruskal–Walli’s test was employed, as it does not require normally distributed data. The assessment of cultivable gut bacteria data was conducted using a one-way ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test. Differences were accepted as significant at the 95% level of confidence (p < 0.05). All statistical calculations were performed using Statistics 7.0 software (USA).

3. Results

3.1. Short Experiment

No mortality of S. trutta fry exposed to 24 h ARS dye was observed during the marking procedure. However, a significant increase in GVF was recorded in the ARS-exposed fry compared with the control group after 24 h of exposure (Kruskal–Wallis H = 6.87, 1 d. f., p = 0.009). The GVF of the former group (114.40 ± 3.37 counts/min) was significantly higher than that of the latter group (110.00 ± 2.83 counts/min; p = 0.013). Furthermore, analysis of fish gut microbiota showed that the total number of cultivable gut bacteria in S. trutta fry significantly increased (one-way ANOVA: F2.12 = 22.050; p = 0.0001) in the ARS-exposed group (6.6 ± 2.0 × 107 CFU/g) compared to the control fish (7.0 ± 1.8 × 106 CFU/g) (Figure 1).

3.2. Prolonged Experiment

Further analysis revealed significant differences in fish size between marked and non-marked specimens (Table 1). The TL of non-marked fish was found to be 88.8 ± 1.1 mm, while marked fish exhibited a TL of 84.0 ± 1.0 mm (Student’s t-test: df = 220, t = 3.41, p < 0.001). The results also revealed significant differences in fish weight (Student’s t-test: df = 220, t = 4.31, p < 0.001) and Fulton condition factor (Student’s t-test: df = 220, t = 7.25, p < 0.001) (Table 1). After seven months of rearing, the final body size of the fish reflected the near-natural conditions used in the experiment. Fish were maintained at low water temperatures (8–10 °C) and under a restricted feeding regime, conditions comparable to those in natural streams. Such environmental parameters result in slow and uniform growth, consistent with values reported for S. trutta juveniles under similar temperature and feeding conditions [32]. Although the difference in total length between the groups was statistically significant (~5 mm), its biological relevance remains uncertain. Such variation falls within the natural range reported for juvenile S. trutta and is unlikely to have major implications for growth performance or fitness under natural conditions.

The mortality rate for fish marked with ARS within a 7-month period was calculated to be 21.3% (32/150), while for fish that were not marked, the mortality rate was slightly lower at 17.3% (26/150). However, a Chi-squared test (χ21 = 0.33, p = 0.56) revealed that there was no significant difference between these two groups. The slightly higher mortality observed among marked fish may indicate a minor physiological cost of ARS exposure, although the difference was small and not statistically significant. Overall, this analysis provides an indicative comparison of survival and growth under standard marking conditions.

Furthermore, after a period of 7 months following the treatment, no significant alterations were observed in the fish erythrocyte count (Kruskal–Wallis H = 0.16, 1 d.f., p = 0.685; ARS group: 0.84 ± 0.27 × 106/μL, control group: 0.87 ± 0.29 × 106/μL) and the total white blood cell count (Kruskal–Wallis H = 1.42, 1 d.f., p = 0.233 ARS group: 25.95 ± 12.45 × 103/μL, control group: 20.75 ± 10.36 × 103/μL), suggesting that the standard ARS marking did not produce long-term hematological signs of impaired aerobic capacity or chronic stress (Table 2).

Table 2.

The hematological parameters of Salmo trutta juveniles after 7 months post-treatment: number of measured specimens within a group (N); erythrocyte count (×106/µL); leukocyte count (×103/µL).

The anonymous analysis of 20 encoded otoliths demonstrated the efficacy of the method for identifying ARS-marked S. trutta specimens, with 100% detection accuracy being achieved (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The otoliths of non-marked (A) and ARS-marked (B) Salmo trutta after 7 months under green illumination (4× magnification).

4. Discussion

Overall, our results indicate that ARS otolith marking did not cause acute mortality but induced mild, sub-lethal effects, including reduced growth and slight changes in condition and selected blood parameters of S. trutta fry. These effects should be taken into account when applying ARS marking, particularly in conservation and restocking programmes.

It is well established that stress influences fish breathing, extends the critical acclimation phase and may potentially result in a diminished growth rate in fish in the long term [33]. Furthermore, experimental findings demonstrated a substantial increase in cultivable gut bacteria numbers in fish groups exposed to ARS. The ingestion of chemicals and compounds can have deleterious effects on the organism, potentially causing an imbalance in the gut microbial community [34]. The gut microbiota of fish plays a pivotal role in regulating host physiology, participating in the process of nutrient digestion, metabolizing xenobiotics, producing a variety of bioactive molecules, and maintaining homeostasis and host immunity [25,35]. It is known that exposure to stressors can modify the composition of the gut microbiome, consequently leading to impaired energy metabolism and nutrient uptake, resulting in stunted growth and increased mortality [33,36,37]. Furthermore, changes in the gut microbiota can cause dysbiosis-an overgrowth of potential pathogenic bacteria that can lead to systemic infections harming the host [38]. Intestinal imbalance has also been linked to hematobiochemical changes and decreased antioxidant enzyme activity in fish [39]. Additionally, imbalances in the gut microbiota and increases in microbes that produce toxic metabolites can weaken the integrity of the intestinal mucosal barrier, which is the first line of defense against harmful substances, disrupt immunomodulation in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue, and trigger an inflammatory response [40,41].

Our long-term growth experiment with S. trutta also suggests that ARS marking can have deleterious consequences. A slight trend toward a decline in weight, size, and overall fitness was observed in the fish group that had been exposed to ARS after 7-month in comparison to the control group. Additionally, the results indicated a non-significant tendency toward a reduction in the number of erythrocytes and an increase in the number of leukocytes in the ARS-exposed group compared to the control group. However, these differences did not reach statistical significance. The reduction in erythrocytes in salmonids is typically attributable to oxidative stress or damage to erythropoietic tissues [42], whereas an increase in leukocytes is often indicative of a fish responding to an infection, inflammatory condition or other environmental stressor [43]. In summary, an increase in the total number of white blood cells typically suggests an active immune response, while a decrease in erythrocytes may indicate anaemia or stress, both of which can be critical for the health and survival of salmonids. The overall prolonged mortality rate also did not differ significantly, although a slight trend toward higher mortality in the ARS-exposed fish group was observed throughout the experiment. Nevertheless, from a monitoring perspective, even weak, non-significant tendencies may hold ecological relevance when evaluated across longer temporal scales or in the presence of cumulative stressors. Recent work shows that small hematological shifts can act as early-warning indicators of subclinical physiological strain in fish, particularly in environments where multiple anthropogenic pressures interact [44]. In this context, the observed tendencies, although not statistically meaningful highlight the value of integrating hematological and condition-related metrics into long-term monitoring frameworks, as such metrics can capture low-intensity responses that precede measurable effects at the population level [45]. From an ecological standpoint, the absence of significant differences also suggests that standard ARS marking is unlikely to impose strong physiological burdens under controlled conditions. However, subtle trends warrant continued observation in natural systems, where additional factors such as temperature fluctuations, food limitation, or pathogen exposure may amplify fish vulnerability [46].

Although the absolute differences in TL, W and KF between ARS-marked and control juveniles were relatively small but statistically different, research on salmonids shows that even modest reductions in somatic growth and energetic condition during early life stages can have cumulative ecological consequences. Lower body weight and reduced condition factor often converts into decreased energy reserves, lower metabolic efficiency, and diminished tolerance to starvation or environmental fluctuation [2,3]. Juveniles in poorer condition typically show reduced competitive ability for feeding territories, diminished overwintering success, and higher susceptibility to predation, particularly under resource limitation or density-dependent regulation [9]. Therefore, the statistically significant reductions in W and KF observed in ARS-marked fry—despite appearing numerically small under controlled RAS conditions—may become biologically meaningful after release into natural habitats. In addition, the ARS-induced increase in cultivable gut bacteria observed in the short-term trial may reflect microbiota dysbiosis, which is known to impair nutrient uptake, metabolic efficiency, and overall growth performance in teleosts [25,34]. Together, these mechanisms suggest that even subtle physiological and condition-related disruptions following ARS marking may influence post-stocking performance and competitive dynamics. In post-stocking scenarios, such differences may weaken fry during the critical initial period after release, when access to shelter and high-quality feeding microhabitats largely determines survival outcomes [2,9]. Fish in slightly poorer condition typically show reduced foraging success and limited ability to defend territories, potentially reinforcing growth disadvantages over time and diminishing their long-term contribution to the stocked cohort. These considerations highlight that even subtle differences in energetic condition at the time of release can shape post-stocking performance and should be taken into account when applying ARS in conservation and restocking programmes.

The use of alizarin dye in the marking of fish otoliths is a widely employed method within the domain of sustainable fishery management. Typically, ARS dye is employed to differentiate artificially bred fish from their naturally occurring counterparts in experiments designed to assess restocking efficiency. The present study demonstrated 100% detection accuracy of ARS marks following a 7-month period of S. trutta fry dying procedures, accompanied by 21.3% mortality rate, which was not significantly bigger compared to the control group. In general, natural annual survival rate of 0+ S. trutta exhibits variability, ranging from approximately 25% to 75%. This variability is associated with factors such as water temperature, habitat quality, food availability and quality, and density-dependent factors [47,48]. In this particular context, the survival rate of 0+ S. trutta kept in the laboratory approximates the lower survival limits. This suggests that ARS marking is a highly effective tool for distinguishing fish groups in experimental settings, with a detection accuracy maintained for a period of up to one year. Though, further research is needed to ascertain the longevity of this marking method.

5. Conclusions

Overall, this study expresses some concerns about the effects of ARS marking on fish health. Some negative effects were revealed, such as a significant increase in gill ventilation and a change in the gut microbiota balance. These effects may be associated with a delayed reduction in growth rate. Therefore, evaluating artificially bred fish growth in wild experiments it should be noted that the reduced growth observed in the experiments may be attributable to the ARS marking procedure itself, rather than to the artificial breeding. The present findings raise concerns about potential limitations in studies that prioritize the assessment of fish stocking effectiveness and subsequent growth. While ARS provides excellent long-term mark retention (100% detection after seven months), our results indicate that this benefit comes with measurable physiological and microbiological costs. Even small early-life differences in weight and condition factor may have cumulative ecological implications, as juveniles in poorer energetic condition typically show reduced competitive ability, increased susceptibility to predation, and lower overwinter survival in natural environments. These considerations highlight an important trade-off between ARS marking efficiency and its potential sub-lethal impacts on fry performance. Future research should therefore focus on longer-term, post-release evaluations to determine whether the observed physiological and microbial alterations persist in natural settings, how they influence competitive ability and habitat acquisition, and whether the gut microbiome recovers after stocking. Such studies are needed to fully understand the long-term implications of ARS-induced sub-lethal stress and to refine mass-marking practices in aquaculture and conservation programmes. This underscores the necessity for further research to investigate the prolonged, delayed negative impact of potentially harmful compounds that are widely utilized in aquaculture.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.R.; methodology, D.M., Ž.J. and V.S.-A.; software, S.R. and T.V.; validation, S.R.; formal analysis, T.V.; investigation, D.M., V.R. and S.R.; resources, J.P.; data curation, T.V.; writing—original draft preparation, V.R., S.R., D.M., V.S.-A. and Ž.J.; writing—review and editing, T.V.; visualization, S.R.; supervision, V.R.; project administration, D.M. and S.R.; funding acquisition, D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the PhD of Ecology and Environmental Science of Nature Research Centre in collaboration with Vilnius University (PhD study contract No 2018-DOK-7). This work was also funded by NATO Science for Peace and Security Programme “Creating a Strategy for Assessing and Restoring War-affected Aquatic Ecosystem” (project No G6085).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All sampling and surveys were conducted in accordance with the Lithuanian law. The research in this manuscript has been conducted under State Food and Veterinary Service (Valstybinė maisto ir veterinarijos tarnyba, VMVT), approval code: No. G2–168 and approval date: 27 January 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to our lab colleagues for their unwavering support and collaboration in the field, which proved crucial to the success of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of this study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ARS | Alizarin Red S |

| CFU | Colony forming units |

| GVF | Gill ventilation frequency |

| KF | Fulton condition factor |

| RAS | Recirculating aquaculture system |

| TL | Total length |

| W | Total weight |

References

- HELCOM. Sea Trout Populations and Rivers in the Baltic Sea; Helsinki Commission: Helsinki, Finland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson, B.; Jonsson, N. Ecology of Atlantic Salmon and Brown Trout: Habitat as a Template for Life Histories; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Klemetsen, A.; Amundsen, P.A.; Dempson, J.B.; Jonsson, B.; Jonsson, N.; O’Connell, M.F.; Mortensen, E. Atlantic salmon Salmo salar L.; brown trout Salmo trutta L. and Arctic charr Salvelinus alpinus (L.): A review of aspects of their life histories. Ecol. Freshw. Fish 2003, 12, 1–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Mas, R.; Vezza, P.; Martínez-Capel, F.; Alcaraz-Hernández, J.D. Spawning Habitat Degradation and Loss of Brown Trout (Salmo trutta) in the Upper Ebro River Basin under Climate Change Scenarios. Ecol. Model. 2018, 384, 138–151. [Google Scholar]

- Aprahamian, M.W.; Smith, K.M.; McGinnity, P.; McKelvey, S.; Taylor, J. Restocking of salmonids—Opportunities and limitations. Fish. Res. 2003, 62, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HELCOM. Sea Trout Populations and Rivers in the Baltic Sea—HELCOM Assessment for 2011; Baltic Sea Environment Proceedings 132; HELCOM: Helsinki, Finland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Araki, H.; Schmid, C. Is hatchery stocking a help or harm? Evidence, limitations and future directions in ecological and genetic surveys. Aquaculture 2010, 308 (Suppl. S1), S2–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesminas, V. Lietuvos Lašišinės Žuvys: Biologija, Ekologija ir Išteklių Apsauga; Gamtos Tyrimų Centras: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pinter, K.; Weiss, S.; Lautsch, E.; Unfer, G. Survival and growth of hatchery and wild brown trout (Salmo trutta) parr in three Austrian headwater streams. Ecol. Freshw. Fish 2017, 27, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, E.C.; Schroder, S.L.; Grimm, J.J. Otolith thermal marking. Fish. Res. 1999, 43, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillanders, B.M. Using elemental chemistry of fish otoliths to determine connectivity between estuarine and coastal habitats. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2005, 64, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, X.M.; Zhang, P.D.; Nwafili, S.A. The use of alizarin red S and alizarin complexone for immersion marking Japanese flounder Paralichthys olivaceus (T.). Fish. Res. 2009, 98, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, J.; Rösch, R. Mass-marking of brown trout (Salmo trutta L.) larvae by alizarin: Method and evaluation of stocking. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2008, 24, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, H.; Chen, H.; Fu, M.; Peng, X.; Xi, D.; Zhang, Z. Experimental evaluation of calcein and alizarin red S for immersion marking grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus). Fish. Sci. 2015, 81, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campana, S.E. Otolith science entering the 21st century. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2005, 56, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren-Myers, F.; Dempster, T.; Swearer, S.E. Otolith mass marking techniques for aquaculture and restocking: Benefits and limitations. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2018, 28, 485–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crook, D.; O’Mahony, D.J.; Gillanders, B.M.; Munro, A.R.; Sanger, A.C. Quantitative measurement of calcein fluorescence for non-lethal, field-based discrimination of hatchery and wild fish. In Advances in Fish Tagging and Marking Technology; McKenzie, J., Parsons, B., Seitz, A.C., Kopf, R.K., Mesa, M., Phelps, Q., Eds.; American Fisheries Society: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2012; pp. 389–396. [Google Scholar]

- Unfer, K.; Pinter, K. Marking otoliths of brown trout (Salmo trutta L.) embryos with alizarin red S. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2013, 29, 470–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, L.A.; Campana, S.E. Chemical Composition of Fish Hard Parts as a Natural Marker of Fish Stocks. In Stock Identification Methods: Applications in Fishery Science, 2nd ed.; Cadrin, S.X., Kerr, L.A., Mariani, S., Eds.; Elsevier: San Diego, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 205–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lejk, A.M.; Radtke, G. Effect of marking Salmo trutta lacustris L. larvae with alizarin red S on their subsequent growth, condition, and distribution as juveniles in a natural stream. Fish. Res. 2021, 234, 105786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J.; Wickström, H. Long-term retention of alizarin red S marks and coded wire tags in European eels. Fish. Res. 2020, 224, 105453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turek, J.; Lepič, P.; Bořík, A.; Galicová, P.; Nováková, P.; Avramović, M.; Randák, T. Evaluation of large-scale marking with alizarin red S in different age rainbow trout fry for nonlethal field identification. Acta Ichthyol. Piscat. 2024, 54, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudron, A.; Champigneulle, A. Multiple marking of otoliths of brown trout (Salmo trutta L.) with alizarin red S to compare efficiency of stocking of three early life stages. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2009, 16, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.; Sørensen, S.R.; Peck, M.A.; Støttrup, J.G. Sublethal effects of alizarin complexone marking on Baltic cod (Gadus morhua) eggs and larvae. Aquaculture 2012, 324–325, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egerton, S.; Culloty, S.; Whooley, J.; Stanton, C.; Ross, R.P. The Gut Microbiota of Marine Fish. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llewellyn, M.S.; Boutin, S.; Hoseinifar, S.H.; Derome, N. Teleost microbiomes: The state of the art in their characterization, manipulation and importance in aquaculture and fisheries. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, C.; Nagar, S.; Lal, R.; Negi, R.K. Fish Gut Microbiome: Current Approaches and Future Perspectives. Indian J. Microbiol. 2018, 58, 397–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanbari, M.; Kneifel, W.; Domig, K.J. A new view of the fish gut microbiome: Advances from next-generation sequencing. Aquaculture 2015, 448, 464–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campana, S.E.; Thorrold, S.R. Otoliths, increments, and elements: Keys to a comprehensive understanding of fish populations? Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2001, 58, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 7346-1:1996; Water Quality—Determination of the Acute Lethal Toxicity of Substances to a Freshwater Fish (Brachydanio rerio Hamilton-Buchanan)—Part 1: Static Method. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1996.

- Caudron, A.; Champigneulle, A. Technique de fluoromarquage en masse à grande échelle des otolithes d’alevins vésiculés de truite commune (Salmo trutta L.) à l’aide de l’alizarine red S. Cybium 2006, 30, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Jurgelėnė, Ž.; Montvydienė, D.; Šemčuk, S.; Stankevičiūtė, M.; Sauliutė, G.; Pažusienė, J.; Morkvėnas, A.; Butrimienė, R.; Jokšas, K.; Pakštas, V.; et al. The impact of co-treatment with graphene oxide and metal mixture on Salmo trutta at early development stages: The sorption capacity and potential toxicity. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakakhel, M.A.; Narwal, N.; Kataria, N.; Johari, S.A.; Zaheer Ud Din, S.; Jiang, Z.; Khoo, K.S.; Xiaotao, S. Deciphering the dysbiosis caused in the fish microbiota by emerging contaminants and its mitigation strategies—A review. Environ. Res. 2023, 237, 117002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evariste, L.; Barret, M.; Mottier, A.; Mouchet, F.; Gauthier, L.; Pinelli, E. Gut microbiota of aquatic organisms: A key endpoint for ecotoxicological studies. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 248, 989–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, R.L.; Volkoff, H. Gut microbiota and energy homeostasis in fish. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Wu, S.; Zeng, Z.; Fu, Z. Effects of environmental pollutants on gut microbiota. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 222, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Albores, F.; Martínez-Córdova, L.R.; Hernández-Mendoza, A.; Cicala, F.; Lago-Lestón, A.; Martínez-Porchas, M. Therapeutic modulation of fish gut microbiota, a feasible strategy for aquaculture? Aquaculture 2021, 544, 737050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, R.; Severino, R.; Silva, S.M. Signatures of dysbiosis in fish microbiomes in the context of aquaculture. Rev. Aquac. 2024, 16, 706–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Q.; Yu, L.; Li, T.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W. Effect of dietary probiotic supplementation on intestinal microbiota and physiological conditions of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) under waterborne cadmium exposure. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2017, 110, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- See, M.S.; Ching, X.L.; Khoo, S.C.; Abidin, S.Z.; Sonne, C.; Ma, N.L. Aquatic microbiomes under stress: The role of gut microbiota in detoxification and adaptation to environmental exposures. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 17, 100612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Fan, N.; Ma, S.X.; Cheng, X.; Yang, X.; Wang, G. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis: Pathogenesis, Diseases, Prevention, and Therapy. MedComm 2025, 6, e70168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witeska, M.; Kondera, E.; Bojarski, B. Hematological and Hematopoietic Analysis in Fish Toxicology—A Review. Animals 2023, 13, 2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuthen, D.; Meuthen, I.; Bakker, T.C.M.; Thünken, T. Anticipatory plastic response of the cellular immune system in the face of future injury: Chronic high perceived predation risk induces lymphocytosis in a cichlid fish. Oecologia 2020, 194, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Andotra, M.; Kaur, A. Cytogenotoxicity and Hematological Alterations Induced by the Environmentally Relevant Concentration of Low-Density Polyethylene Microplastics and Nickel Oxide Nanoparticles in Cirrhinus mrigala (Ham.). J. Appl. Toxicol. 2025, 44, 1416–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, N.; Ahmed, I.; Wani, G.B. Hematological and serum biochemical reference intervals of rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss cultured in Himalayan aquaculture: Morphology, morphometrics and quantification of peripheral blood cells. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 29, 2942–2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, D.; Shanmugam, S.A.; Kathirvelpandian, A.; Eswaran, S.; Rather, M.A.; Rakkannan, G. Unraveling the Impact of Climate Change on Fish Physiology: A Focus on Temperature and Salinity Dynamics. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2024, 2024, 5782274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerniawski, R.; Pilecka-Rapacz, M.; Domagała, J. Growth and survival of brown trout fry (Salmo trutta m. fario L.) in the wild, reared in the hatchery on different feed. Electron. J. Pol. Agric. Univ. 2010, 13, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Koski, A.; Koljonen, S.; Syrjänen, J.T. Fast colonization of wild brown trout in nature-like compensation channel. River Res. Appl. 2024, 41, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).