Abstract

Background. The prevalence of psychological difficulties is rising at an alarming rate, with an increasing number of individuals reporting symptoms of depression. A decline in both perceived control and desire for control has previously been associated with the onset of depression. However, previous research has failed to examine whether perceived control and desire for control interact in their relationship with depressive symptomology. Methods. A sample of 350 participants completed the Spheres of Control Scale, the Desirability of Control Scale and Beck’s Depression Inventory. Process Macro was used to examine whether desire for control moderated the relationship between perceived control and depressive symptomology. Results. Desire for control significantly moderated the relationship between perceived control and depressive symptomology. The results indicated that variations in perceived control had a greater effect on the manifestation of depressive symptomology in individuals with lower desire for control than those with higher desire for control. Discussion. This study provides novel evidence that desire for control moderates the relationship between perceived control and depressive symptomology. The clinical implications of the results are discussed, with reference to future research. Conclusions. The results indicate that individuals with lower desire for control are more sensitive to variations in perceived control, such that decrements in perceived control contribute to a greater increase in depressive symptomology, and vice versa.

Introduction

Depression is characterized by low mood, persistent despondency and loss of interest in pleasurable activities, among other symptoms. The prevalence of depressive symptomology is rising at an alarming rate, currently affecting over 21% of the population [1]. It is critical that psychologists endeavor to elucidate the etiology of depression, to aid the development of effective interventions for people with such psychological difficulties [2].

Perceived Control and Depression

Perceived control refers to the extent to which one believes that one possesses the power to affect one’s environment. Theorists such as Friedrich Nietzsche have advocated the importance of perceived control in psychological welfare long before the formal inception of psychology as a scientific field. Early researchers in psychology also emphasized the importance of perceived control in psychological welfare [3,4], with such propositions formalized in Martin Seligman’s ‘Hopelessness Theory’. This theory argues that the perceived absence of the ability to modulate outcomes in one’s environment culminates in a sense of hopelessness, which increases one’s propensity to the development of depressive symptomology [5,6,7].

Hopelessness theory has ascertained overwhelming empirical support over the last 45 years. Contemporary literature indicates that perceived control maintains an inverse relationship with the development of depressive symptomology [8,9,10,11,12,13]. Moreover, there is strong evidence that this relationship is causal, with decrements in perceived control preceding the onset of depressive symptomology, and vice versa [14,15,16]. These results indicate that perceived control is critical for psychological welfare and that its absence can culminate in the manifestation of symptoms of depression.

Desire for Control and Depressive Symptomology

Desire for control refers to the extent to which one craves power in their environment. Whilst research on this topic is scarce, preliminary evidence indicates that there is an inverse relationship between desire for control and depressive symptomology. Specifically, individuals with higher desire for control exhibit fewer symptoms of depression, and vice versa [17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. Interestingly, the relationship between desire for control and depressive symptomology appears to be consistent among individuals from both individualistic and collectivistic cultures [24]; these results provide tentative evidence that the relationship between the respective facets may represent a universal phenomenon. However, it is important to note that longitudinal data are currently absent, limiting one’s ability to determine whether desire for control causally influences the manifestation of symptoms of depression.

Perceived Control, Desire for Control and Depressive Symptomology

More recently, researchers have begun to examine whether perceived control and desire for control interact in their relationship with depressive symptomology. In a recent article, Myles argued that the upsurge of depressive symptomology, and mental health concerns more generally, in adolescence may be the consequence of large increments in desire for control in the absence of correspondingly high increments in perceived control [22]. Indeed, Amoura ascertained that that there may be an interaction between perceived control and desire for control in their relationship with depression [18]. The authors report that individuals with low perceived control and low desire for control experienced the highest number of symptoms of depression, followed by individuals with low perceived control and high desire for control, followed by individuals with high perceived control and high desire for control; the individuals with high perceived control and low desire for control exhibit the fewest symptoms of depression. However, the authors failed to present analyses detailing whether the differences in the mean scores of the depressive symptomology met the threshold for statistical significance. Nevertheless, these results provide some evidence that perceived control and desire for control interact in their relationship with depression.

Current Study

To the authors’ knowledge, there is currently no research examining whether perceived control and desire for control interact in their effect on depressive symptomology. As previously alluded, Myles suggested that desire for control may moderate the relationship between perceived control and the onset of the symptoms of depression [22]. Accordingly, this study aims at examining whether desire for control and perceived control interact in their relationship with depressive symptomology. Specifically, this paper will reanalyze previously collected data in order to examine whether desire for control moderates the relationship between perceived control and depressive symptomology [22].

Materials and Methods

Design

A cross-sectional design was used to examine the moderating role of desire for control in the relationship between perceived control and depressive symptomology.

Participants

A total of 350 participants completed three online questionnaires, examining perceived control, desire for control and depressive symptomology, respectively. The sample included 83 males, 266 females and one individual who did not disclose their gender. Additionally, the mean age of the participants was 22.8 years (SD = 9.0), ranging from 18 to 67 years. Our sample was recruited largely from Durham University’s social media pages, with only individuals over 18 years of age permitted to participate in the study. All participants provided informed consent for their participation in this study.

Measures Perceived Control

Perceived control was examined using the ‘Spheres of Control Scale 3’ [25,26]. This scale adopts a holistic perspective over perceived control by examining the extent to which individuals perceive their being in control of various domains of their lives. It includes 30 statements and the participants are required to rate their agreement on a 7-point Likert scale; for example, “I can usually achieve what I want when I work hard for it.” The reliability of this measure was strong, with an internal consistency of α = .804. Moreover, there is significant support in the literature for this tool as a valid measure of perceived control [27,28].

Desire for Control

Desire for control was examined using the ‘Desirability of Control Scale’ [29]. This 20-item scale examines the extent to which individuals crave power within their environment. The items are statements for which the individuals rate their agreement on a 7-point Likert scale; for example, “I enjoy making my own decisions.” This scale had strong reliability, with an internal consistency of α = .803. Moreover, research indicates that this measure represents both a valid [30] and reliable measure of desire for control [31].

Depressive Symptomology

Depressive Symptomology was examined using ‘Beck’s Depression Inventory 2’ [32]. This measure consists of 21 items and requires individuals to rate their agreement with statements such as, “I hate myself”. The measure was deemed highly reliable, with an internal consistency of α = .929. Moreover, the validity of this measure has ascertained significant empirical support in the literature [33].

Procedure

Durham University Ethics Committee provided the ethical approval for this study to be conducted. All the individuals participating in the study were informed of the potentially distressing content of the questionnaires and were provided with information regarding the procedure, so that informed consent could be ascertained. Participants then provided demographic information, including their age and gender, prior to completing the Spheres of Control Scale 3, the Desirability of Control Scale and Beck’s Depression Inventory 2. Finally, participants were debriefed on the aims of the study and provided with the contact details of relevant mental health support services.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 displays the means, standard deviations and zero-order correlations between the variables. These preliminary analyses indicate that all variables were significantly correlated (p < .01). As perceived control and desire for control did not entail a correlation coefficient higher than 0.9, multi-collinearity was not deemed to be an issue.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations (SD) and intercorrelations between the variables (n=350).

In addition, the data were examined for normality. Perceived control and desire for control were normally distributed, as indicated by the examination of skew indices. However, depressive symptomology was not normally distributed and had a positive skew of 1.203 (standard error = 0.13); a logarithmic transformation was used to correct for positive skew. A moderation analysis was conducted using Process Macro for SPSS to examine whether desire for control moderated the relationship between perceived control and depressive symptomology [34].

Moderation Analysis

The direct effects of perceived control and desire for control on depressive symptomology were examined. Perceived control had a direct effect on depressive symptomology (b = -.6175, 95% CI [-.885, -.3501], t = 4.5408, p < .0001), indicating that perceived control entails an inverse relationship with depressive symptomology. Desire for control also maintained a direct effect on depressive symptomology (b = -.6858, 95% CI [-1.1238, -.2478], t = -3.0794, p = .0022), suggesting that there is an inverse relationship between desire for control and depressive symptomology.

The results indicated that there was a significant effect of the interaction between perceived control and desire for control on depressive symptomology (b = .0054, 95% CI [.002, .0088], p = .0021). Critically, the amount of variance accounted for by the model significantly increased by 2.26% with the inclusion of the interaction term, indicating that the inclusion of desire for control as a moderating variable is appropriate, F (1, 352) = 9.5929, P = .0021, ΔR2 = .0226. Overall, the model accounted for 16.99% of the variance in depressive symptomology.

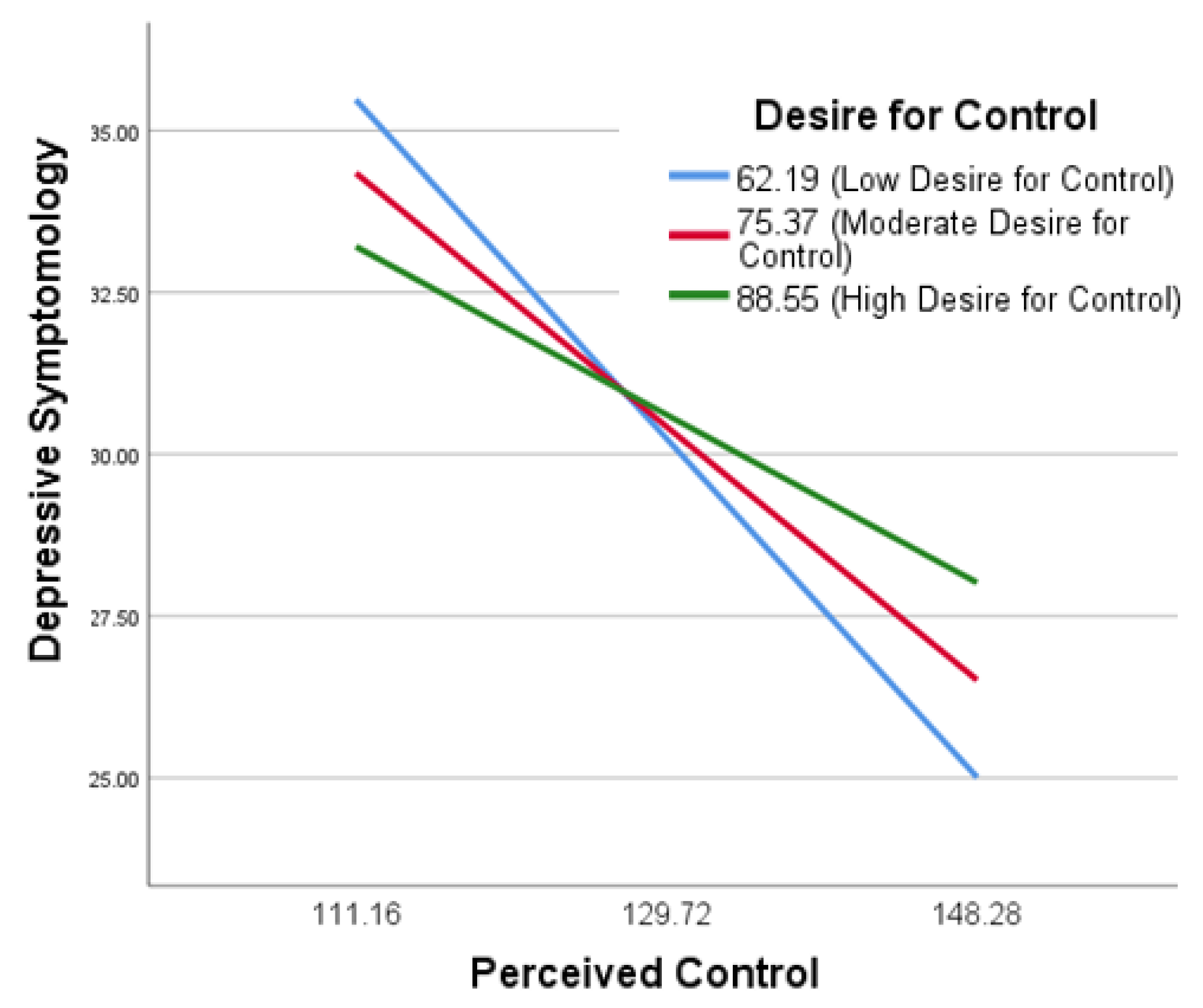

Further analyses were conducted to probe the interaction between desire for control and perceived control in their relationship with depressive symptomology. Simple slopes were used to examine the moderating effect of desire for control in the relationship between perceived control and depressive symptomology. Accordingly, the effect of perceived control on depressive symptomology was examined when desire for control was one standard deviation below the mean, at the mean and one standard deviation above the mean. The results indicated that the relationship between perceived control and depressive symptomology was significant at one standard deviation below the mean (b = -.2820, 95% CI [-.3583, -.2057], t = -7.2677, p < .0001), at the mean (b = -.2109, 95% CI [-.2706, -.1513], t = -6.9567, p < .0001) and at one standard deviation above the mean (b = -.1398, 95% CI [-.2131, -.0666], t = -3.755, p = .0002). Moreover, the Johnson-Neyman output indicates that the effect of perceived control on depressive symptomology was significant at low, moderate and relatively high levels of desire for control (p ≤ .05). However, at very high levels of desire for control, such that participants score above 97 out of 112 on the Desirability of Control Scale [29], the effect of perceived control on depressive symptomology was no longer statistically significant (p > .05).

Inspection of Figure 1 provides greater insight into the nature of the moderating role of desire for control in the relationship between perceived control and depressive symptomology. Figure 1 indicates that perceived control maintains an inverse relationship with depressive symptomology, irrespective of the extent to which participants crave control. However, fluctuations in perceived control entail a greater influence over variations in depressive symptomology in participants with lower desire for control, compared to individuals with higher desire for control.

Figure 1.

The Moderating Effect of Desire for Control in the Relationship between Perceived Control and Depressive Symptomology.

Discussion

The results indicate that both perceived control and desire for control maintain inverse relationships with depressive symptomology, such that decrements in the control-related facets are associated with increments in the symptoms of depression. Furthermore, the current study extends previous data by demonstrating that desire for control moderates the relationship between perceived control and depressive symptomology. Specifically, fluctuations in perceived control entail a greater influence over variations in depressive symptomology in individuals with lower desire for control, compared to individuals with higher desire for control. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate the moderating role of desire for control in the relationship between perceived control and depressive symptomology.

Indeed, the results from the current study are in line with previous research. An abundance of prior research has demonstrated that depressive symptomology entails an inverse relationship with both perceived control [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,13,14,15,16,22] and desire for control [17,18,19,22,24]. These results support this literature and theoretical propositions that the absence of perceived control culminates in a sense of hopelessness, and consequently the manifestation of symptoms of depression [5,6,7]. Moreover, the results indicated that individuals with low perceived control and low desire for control experienced the greatest number of symptoms of depression, followed by individuals with low perceived control and high desire for control, followed by individuals with high perceived control and high desire for control; individuals with high perceived control and low desire for control exhibit the fewest symptoms of depression. Interestingly, these findings are in line with the information provided by Amoura; however, Amoura failed to determine whether these differences were statistically significant [18].

Elucidating the phenomenological and experiential basis of the moderating effect of desire for control in the relationship between perceived control and depressive symptomology is necessarily speculative, due to the absence of prior literature in this area [18]. However, it is conceivable that individuals with greater desire for control over their lives will more regularly seek out opportunities to exert control over their environment than individuals with lower desire for control (see [22] for an in-depth discussion). Accordingly, during instances of low perceived control, individuals with high desire for control may be more inclined to seek out opportunities to exert control; this would serve to prevent psychological welfare from further deterioration. In contrast, individuals with lower desire for control may be less likely to attempt to find opportunities to exert control, culminating in further psychological distress and elevated depressive symptomology [22]. When perceived control is high, this may be less rewarding for individuals with high desire for control, as a sense of control may be, to some extent, anticipated. However, high perceived control may be particularly rewarding for individuals with lower desire for control, as increments in perceived control may not be anticipated. This theory accounts for the results obtained in the current study from a more phenomenological and experiential perspective.

Clinical Implications

These results have critical implications for applied psychologists working in clinical settings. Firstly, this study supports the notion that maintaining both perceived control and desire for control is critical for psychological welfare [22]. Accordingly, clinicians should endeavor to bolster these facets in individuals experiencing symptoms of depression through therapeutic interventions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy. Whilst perceived control is a common target for cognitive therapeutic interventions [35,36,37], desire for control is less frequently targeted in therapeutic interventions. These results indicate that clinicians may be better able to support their clients through the use of therapeutic techniques such as motivational interviewing [38,39] to elevate clients’ desire for control.

Furthermore, evidence that desire for control moderates the relationship between perceived control and depressive symptomology also has important clinical implications. These findings indicate that, whilst clinicians should generally endeavor to preserve perceived control in their clients through therapeutic interventions [35,36], they must

be particularly mindful of enhancing perceived control in individuals with low desire for control, since such individuals may experience greater depressive symptomology as a consequence of decrements in perceived control.

Limitations

One of the primary limitations concerns the cross- sectional design used to collect the data. Whilst statistical techniques indicate that desire for control moderates the relationship between perceived control and depressive symptomology, longitudinal data would be required to determine whether the effect of these variables on depressive symptomology is causal. Secondly, confounding psychological difficulties may have limited the validity of these results. For example, the control- related facets may also modulate symptoms of anxiety, which may confound symptoms of depression [40], resulting in an apparent relationship between the respective facets and depressive symptomology. Finally, the participants’ current medical status was not controlled, and some individuals may have been using antidepressant medication. This may have diminished the observed relationships between the predictor variables and depressive symptomology, as antidepressants can reduce psychological distress [41]. Nevertheless, these limitations are pertinent to the majority of the studies in this area and do not render the results unintelligible, nor do they detract from the relevance of the results to clinical practice.

Future Research

Future research must endeavor to determine whether desire for control entails a causal role in moderating the relationship between perceived control and depressive symptomology through the collection of longitudinal data. In addition, future research should explore the therapeutic applications of these data, examining how clinicians can best support clients by bolstering their desire for control. This is a topic that has received little attention in the literature, despite its significant potential in aiding clinicians to support their clients.

Conclusions

Overall, these findings indicate that both perceived control and desire for control maintain an inverse relationship with depressive symptomology, such that decrements in the control-related facets are associated with increments in the symptoms of depression. However, this study extends the previous research with novel evidence that desire for control moderates the relationship between perceived control and depressive symptomology. Specifically, these results indicate that individuals with lower desire for control are more sensitive to variations in perceived control, such that decrements in perceived control contribute to a greater increase in depressive symptomology, and vice versa.

Conflicts of Interest disclosure

There are no known conflicts of interest in the publication of this article. The manuscript was read and approved by all authors.

Compliance with ethical standards

Any aspect of the work covered in this manuscript has been conducted with the ethical approval of all relevant bodies and that such approvals are acknowledged within the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Liam Myles would like to thank the Harding Distinguished Postgraduate Scholars Programme Leverage Scheme and the Economic and Social Research Council Doctoral Training Partnership for funding his research at the University of Cambridge.

References

- Auerbach, S.M.; Clore, J.N.; Kiesler, D.J.; Orr, T.; Pegg, P.O.; Quick, B.G.; Wagner, C. Relation of diabetic patients' health-related control appraisals and physician–patient interpersonal impacts to patients' metabolic control and satisfaction with treatment. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2002, 25, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myles, L.A.M. The Emerging Role of Computational Psychopathology in Clinical Psychology. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy. The Corsini encyclopedia of psychology. 2010, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.W. Motivation reconsidered: The concept of competence. Psychological review. 1959, 66, 297–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, L.Y.; Seligman, M.E.; Teasdale, J.D. Learned helplessness in humans: Critique and reformulation. Journal of abnormal psychology. 1978, 87, 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, L.Y.; Metalsky, G.I.; Alloy, L.B. Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological review. 1989, 96, 358–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E. Helplessness: On depression, development, and death. New York, NY: Henry Holt & Co. 1975. [CrossRef]

- Bjørkløf, G.H.; Engedal, K.; Selbæk, G.; Maia, D.B.; Coutinho, E.S.F.; Helvik, A.S. Locus of control and coping strategies in older persons with and without depression. Aging & mental health. 2016, 20, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Cheung, S.F.; Chio, J.H.M.; Chan, M.P.S. Cultural meaning of perceived control: a meta-analysis of locus of control and psychological symptoms across 18 cultural regions. Psychological bulletin. 2013, 139, 152–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandall, A.; Allsop, Y.; Hanson, C.L. The longitudinal association between cognitive control capacities, suicidality, and depression during late adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of adolescence. 2018, 65, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinberg, A.; Aluoja, A.; Vasar, V. Social support in depression: structural and functional factors, perceived control and help-seeking. Epidemiology and psychiatric sciences. 2013, 22, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myles, L.A.M. Taking control of mental health. The Psychologist. 2020, 33, 7–7. [Google Scholar]

- Volz, M.; Voelkle, M.C.; Werheid, K. General self-efficacy as a driving factor of post-stroke depression: A longitudinal study. Neuropsychological rehabilitation. 2018, 29, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørkløf, G.H.; Engedal, K.; Selbæk, G.; Maia, D.B.; Borza, T.; Benth, J.Š.; Helvik, A.S. Can depression in psychogeriatric inpatients at one-year follow-up be explained by locus of control and coping strategies? Aging & mental health. 2018, 22, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, E.W.; Abramson, L.Y. Cognitive patterns and major depressive disorder: A longitudinal study in a hospital setting. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1983, 92, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, S.J.; Raymundo, M.M. Causal uncertainty and psychological well-being: The moderating role of accommodation (secondary control). Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2010, 36, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoura, C.; Berjot, S.; Gillet, N. Desire for control: Its effect on needs satisfaction and autonomous motivation. Revue internationale de psychologie sociale. 2013, 26, 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Amoura, C.; Berjot, S.; Gillet, N.; Altintas, E. Desire for control, perception of control: their impact on autonomous motivation and psychological adjustment. Motivation and Emotion. 2014, 38, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, J.M. Desire for control, locus of control, and proneness to depression. Journal of Personality. 1984, 52, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlo, E.M.; Sicari, F.; Frisone, F.; Costa, G.; Alibrandi, A.; Avena, G.; Settineri, S. Uncertainty, alexithymia, suppression and vulnerability during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Health Psychology Report. 2021, 9, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlo, E.M.; Stoian, A.P.; Motofei, I.G.; Settineri, S. The Role of Suppression and the Maintenance of Euthymia in Clinical Settings. Frontiers in Psychology 2012, 12, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myles, L.A.M.; Connolly, J.; Stanulewicz, N. The Mediating Role of Perceived Control and Desire for Control in the Relationship between Personality and Depressive Symptomology. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myles, L.A.M.; Merlo, E.M. Alexithymia and physical outcomes in psychosomatic subjects: a cross-sectional study. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences. 2021, 8, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsey, M.J.; Greenaway, K.H.; Harris, E.A.; Bain, P.G. Exploring Cultural Differences in the Extent to Which People Perceive and Desire Control. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2018, 45, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulhus, D.L.; Van Selst, M. The spheres of control scale: 10 years of research. Personality and Individual Differences. 1990, 11, 1029–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakka, S.; Nikopoulou, V.A.; Bonti, E.; Tatsiopoulou, P.; Karamouzi, P.; Giazkoulidou, A.; Tsipropoulou, V.; Parlapani, E.; Holeva, V.; Diakogiannis, I. Assessing test anxiety and resilience among Greek adolescents during COVID-19 pandemic. J Mind Med Sci. 2020, 7, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palenzuela, D.L. Sphere-specific measures of perceived control: Perceived contingency, perceived competence, or what? A critical evaluation of Paulhus and Christie's approach. Journal of research in personality. 1987, 21, 264–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherer, M.; Maddux, J.E.; Mercandante, B.; Prentice-Dunn, S.; Jacobs, B.; Rogers, R.W. The self-efficacy scale: Construction and validation. Psychological reports. 1982, 51, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, J.M.; Cooper, H.M. The desirability of control. Motivation and emotion. 1979, 3, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, J.M. Desire for control and interpersonal interaction style. Journal of Research in Personality. 1990, 24, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, J.M.; Solano, C.H. Changes in desire for control over time: Gender differences in a ten-year longitudinal study. Sex Roles, 4: 31(7-8). [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Brown, G.K. Beck depression inventory-II. San Antonio. 1996, 78, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnau, R.C.; Meagher, M.W.; Norris, M.P.; Bramson, R. Psychometric evaluation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II with primary care medical patients. Health Psychology. 2001, 20, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockwood, N.J.; Hayes, A.F. Mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: Regression-based approaches for clinical research. In Handbook of research methods in clinical psychology; Wright, A.G.C.; Hallquist, M.N., Eds.; Cambridge University Press. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J.; Proudfoot, J.; Birch, M.R.; Whitton, A.E.; Parker, G.; Manicavasagar, V.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D. Effects of mental health self-efficacy on outcomes of a mobile phone and web intervention for mild-to-moderate depression, anxiety and stress: secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. BMC psychiatry. 2014, 14, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, Z.V.; Williams, M.; Teasdale, J. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression. New York, NY: Guilford Press. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Jordan, W.J. Mental Health & Drugs; A Map the Mind. J Mind Med Sci. 2020, 7, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R.; Rollnick, S. Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. Guilford press. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Rollnick, S.; Miller, W.R.; Butler, C. Motivational interviewing in health care: helping patients change behavior. Guilford Press. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Fydrich, T.; Dowdall, D.; Chambless, D.L. Reliability and validity of the Beck Anxiety Inventory. Journal of anxiety disorders. 1992, 6, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitz, E.S.; Hollon, S.D.; Twisk, J.; Van Straten, A.; Huibers, M.J.; David, D.; Faramarzi, M. Baseline depression severity as moderator of depression outcomes between cognitive behavioral therapy vs pharmacotherapy: an individual patient data meta-analysis. JAMA psychiatry. 2015, 72, 1102–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]