Abstract

The Honey Badger Algorithm (HBA) is a recently proposed metaheuristic optimization algorithm inspired by the foraging behavior of honey badgers. The search mechanism of this algorithm is divided into two phases: a mining phase and a honey-seeking phase, effectively emulating the processes of exploration and exploitation within the search space. Despite its innovative approach, the Honey Badger Algorithm (HBA) faces challenges such as slow convergence rates, an imbalanced trade-off between exploration and exploitation, and a tendency to become trapped in local optima. To address these issues, we propose an enhanced version of the Honey Badger Algorithm (HBA), namely the Multi-Strategy Honey Badger Algorithm (MSHBA), which incorporates a Cubic Chaotic Mapping mechanism for population initialization. This integration aims to enhance the uniformity and diversity of the initial population distribution. In the mining and honey-seeking stages, the position of the honey badger is updated based on the best fitness value within the population. This strategy may lead to premature convergence due to population aggregation around the fittest individual. To counteract this tendency and enhance the algorithm’s global optimization capability, we introduce a random search strategy. Furthermore, an elite tangential search and a differential mutation strategy are employed after three iterations without detecting a new best value in the population, thereby enhancing the algorithm’s efficacy. A comprehensive performance evaluation, conducted across a suite of established benchmark functions, reveals that the MSHBA excels in 26 out of 29 IEEE CEC 2017 benchmarks. Subsequent statistical analysis corroborates the superior performance of the MSHBA. Moreover, the MSHBA has been successfully applied to four engineering design problems, highlighting its capability for addressing constrained engineering design challenges and outperforming other optimization algorithms in this domain.

1. Introduction

Optimization refers to the process of finding the best solution for a given system from all possible values to maximize or minimize the output. Over the past few decades, as the complexity of problems has increased, the demand for new optimization techniques has become more pressing [1,2]. In the past, traditional mathematical techniques used to solve optimization problems were mostly deterministic, but a major issue was their tendency to become trapped in local optima. This has resulted in low efficiency when using these techniques to solve practical optimization problems over the past two decades [3,4], thereby increasing interest in stochastic optimization techniques. In general, most real-world optimization problems—such as those in engineering [5], wireless sensor networks [6], image processing [7], feature selection [8,9], tuning machine learning parameters [10], and bioinformatics [11]—are highly nonlinear and non-convex due to inherent complex constraints and numerous design variables. Therefore, solving these types of optimization problems is highly complex due to the presence of numerous inherent local minima. Additionally, there is no guarantee of finding a global optimal solution.

Optimization problem-solving algorithms are classified into five main categories based on heuristic creation principles. Human-based optimization algorithms are designed based on human brain thinking, systems, organs, and social evolution. An example is the well-known Neural Network Algorithm (NNA) [12], which solves problems based on the message transmission in neural networks of the human brain. The Harmony Search (HS) algorithm [13,14] simulates the process by which musicians achieve a harmonious state by iteratively adjusting pitches through memory recall.

Algorithms that mimic natural evolution are classified as evolutionary optimization algorithms. The Genetic Algorithm (GA) [15] is the most classic model that simulates evolution, where chromosomes form offspring through a series of stages in cycles and produce more adaptive individuals through selection and reproduction mechanisms. Additionally, the differential evolution (DE) algorithm [16,17], the Imperialist Competitive Algorithm (ICA) [18], and the Mimetic Algorithm (MA) [19] are also based on evolutionary mechanisms.

Population-based optimization algorithms simulate the behaviors of biological populations, including reproduction, predation, and migration. In these algorithms, individuals in the population are treated as massless particles searching for the best position. The Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) algorithm [20,21] utilizes the concept of ants finding the shortest path from the nest to food sources. The Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm [22] is derived from the foraging behavior of birds and is widely recognized as a swarm intelligence algorithm. The Moth Flame Optimization (MFO) algorithm [23] is a mathematical model that simulates the unique navigation behavior of moths, which spiral towards a light source until they reach the “flame.” Other swarm intelligence algorithms include the Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) algorithm [24], the Moth-Flame Optimization (MFO) algorithm [25], the Artificial Hummingbird Algorithm (AHA) [26], the Stinky Pete Optimization (DMO) algorithm [27], the Chimpanzee Optimization Algorithm (CHOA) [28,29], the Raccoon Optimization Algorithm (COA) [30], the Beetle Optimization Algorithm (DBO) [31], Harris Hawk Optimization (HHO) [32], and the Osprey Optimization Algorithm (OOA) [33].

Plant growth-based optimization algorithms. The inspiration for these algorithms comes from plant characteristics such as photosynthesis, flower pollination, and seed dispersal. The Dandelion Optimization (DO) algorithm [34] is inspired by the processes of rising, falling, and landing of dandelion seeds in various wind directions. Algorithms that mimic the aggressive invasion of weeds, their search for suitable living spaces, and their utilization of natural resources for rapid growth and reproduction are known as Invasive Weed Optimization (IWO) [35].

Physics-based optimization algorithms are developed based on natural physical phenomena and laws. The Gravity Search Algorithm (GSA) [36] originates from the concept of gravity, and it possesses powerful global search capabilities and fast convergence speed. The Artificial Raindrop Optimization Algorithm (ARA) [37] is designed based on the processes of raindrop formation, landing, collision, aggregation, and evaporation into water vapor.

In particular, due to their excellent performance, many algorithms have been applied to a wide range of practical engineering problems, such as feature selection [38,39,40], image segmentation [41,42], signal processing [43], hydraulic facility construction [44], walking robot path planning [45,46], job shop scheduling [47], and pipeline and wiring optimization in industrial and agricultural production [48]. Unlike gradient-based optimization algorithms, metaheuristic algorithms rely on probabilistic searches rather than gradient-based methods. In the absence of centralized control constraints, the failure of individual agents will not affect the overall problem-solving process, ensuring a more stable search process. Typically, as a first step, it is necessary to appropriately set the basic parameters of the algorithm and generate an initial population of random solutions. Next, the search mechanism of the algorithm is employed to locate the optimal value until a stopping criterion is met or the optimal value is identified [49]. However, it is evident that each algorithm possesses distinct advantages and disadvantages, and its performance may vary depending on the specific problem being addressed. The “No Free Lunch” (NFL) theorem [50] posits that while an algorithm may effectively solve certain optimization problems, there is no universal guarantee that it can successfully address other optimization problems. Therefore, when confronted with several specific problems, it is reasonable to propose multiple strategies to enhance the efficiency of the algorithm.

In order to identify more effective problem-solving approaches, numerous researchers have endeavored to develop new algorithms and enhance existing methods. Research on metaheuristic optimization algorithms has led to the development of effective search strategies for achieving global optimality. Due to the exponential growth of the search space in real-life optimization problems, which often exhibit multimodality, traditional optimization methods frequently yield suboptimal solutions. Over the past few decades, the development of numerous new metaheuristic algorithms [51] has demonstrated robust performance across a broader spectrum of complex problems.

The Honey Badger Algorithm (HBA) is a novel metaheuristic algorithm proposed by Fatma A. Hashim et al. in 2022, inspired by the foraging behavior of honey badgers in nature. The algorithm searches for the optimal solution to problems by simulating the dynamic foraging and digging behaviors of honey badgers. The algorithm is known for its strong search ability and fast convergence speed compared to other algorithms, but it also has the disadvantage of slower search performance in the late stages and a tendency to become trapped in local optimal solutions.

The proposed Multi-Strategy Honey Badger Algorithm (MSHBA) is introduced to address the aforementioned issues. Due to the random generation of initial populations in the basic Honey Badger search algorithm, it cannot guarantee the uniform distribution of individuals within the search space, thereby affecting the algorithm’s search efficiency and optimization performance. The Cubic chaos mapping mechanism is incorporated into the initialization process of the improved Honey Badger algorithm to enhance the traversal capability of the initial population. During the digging and honey-seeking phases of the Honey Badger Algorithm, the positions of the agents are updated based on the best value within the population. This approach can lead to premature convergence due to population clustering around the optimal individual. To enhance the global optimization capability of the Honey Badger Algorithm, a random search strategy is introduced. When the population identifies the same best value for three consecutive iterations, both the elite tangent search and the differential mutation strategy are executed. Finally, the MSHBA algorithm is tested and validated on the CEC 2017 benchmark suite, demonstrating improved convergence speed and accuracy, as well as high efficiency in solving engineering problems.

2. Fundamentals of Honey Badger Algorithm

In the standard Honey Badger Optimization Algorithm, the optimal solution to the optimization problem is obtained by updating the prey odor intensity factor and employing two distinct foraging strategies of honey badgers: the “digging phase” and the “honey phase,” each characterized by unique search trajectories.

During the initialization stage, the population size of honey badgers is , and the position of each individual honey badger is determined by the following equation:

where is a random number between 0 and 1, is the position of the -th honey badger referring to a candidate solution, while and are the lower and upper bounds of the search space, respectively.

Defining Intensity (I): Intensity is related to the concentration of prey and the distance of individual honey badgers. represents the intensity of the scent. If the odor concentration is high, the honey badger searches for prey more rapidly; conversely, if the concentration is low, the search is slower. Therefore, the intensity of the scent is directly proportional to the concentration of the prey and inversely proportional to the square of the distance from the honey badger. The specific definition is given by the following equation:

where is a randomly generated number ranging from 0 to 1, is the prey concentration, and indicates the distance between the prey and the first badger.

Update the density factor. The density factor controls the time-varying randomization to ensure a smooth transition from exploration to exploitation; as the number of iterations increases, the intensity factor decreases, thereby reducing randomization over time, as given by the equation below:

where is the maximum number of iterations, and is a constant ≥1 (default = 2).

Digging phase

At this stage, the honey badger automatically locates beehives by scent and destroys them to obtain food. Its path follows the shape of a heart, and its location is updated as follows:

where is the position of the prey, which is the best position found so far—in other words, the global best position. (default = 6) is ability of the honey badger to obtain food. is the distance between the prey and the th honey badger, see Equation (2). , , and are three different random numbers between 0 and 1. works as the flag that alters search direction; it is determined using Equation (5), where is a randomly generated number ranging from 0 to 1.

Honey phase

At this stage, the honey badger follows the honey guide bird to the beehive to find honey. This process can be described by the following formula:

Here, refers to the new position of the honey badger, whereas denotes the location of the prey. The parameters and are determined using Equations (3) and (5), respectively. From Equation (6), it can be observed that the honey badger performs a search in the vicinity of the best location found so far, based on distance information . At this stage, the search behavior is influenced by a time-varying factor t. Moreover, the honey badger may encounter disturbances , where is a random number between 0 and 1.

3. Multi-Strategy Honey Badger Algorithm

Given the shortcomings of the standard HBA algorithm, such as its tendency to easily fall into local optima and its slow convergence speed in the later stages, this paper introduces a cubic chaotic mapping mechanism during the population initialization phase and incorporates a random search strategy into the position update process of the honey badgers. When the global best solution obtained by the honey badger population remains unchanged for three consecutive iterations, the elite tangent search and differential mutation strategies are introduced.

3.1. Cubic Chaotic Mapping

Since the initial population of the basic Honey Badger Algorithm is generated randomly, the uniform distribution of individuals in the search space cannot be guaranteed, which may negatively impact the convergence speed and optimization performance of the algorithm. To improve the initialization process of the Honey Badger Algorithm, cubic mapping [52] was introduced to enhance the diversity and coverage of the initial population, as shown below:

where denotes the position of the -th honey badger; and represent the lower and upper bounds of the -th variable, respectively; is a constant; and is the cubic chaotic sequence, typically set to a constant value of 3. This method generates individuals in the initial population to ensure a uniform and diverse distribution across the search space.

3.2. Introduction of Random Value Perturbation Strategy for Honey Badger Algorithm

In the Honey Badger Algorithm, the position of each honey badger is updated based on the global best solution , which may easily result in premature convergence as the population tends to cluster around the current best individual. To enhance the global optimization capability of the Honey Badger Algorithm, a random search strategy [53] is incorporated, and the position update mechanism is adaptively determined based on the value of a control coefficient . When the specified condition is , a perturbation-based search strategy is applied to randomly selected individuals; otherwise, the position of the honey badger is updated based on the current global best solution . The expression is given by

In this expression, , denotes a random number drawn from the interval (0,1). Its value decreases linearly from 2 to 0, where denotes a random number drawn from the interval (0,1). It can be seen from the above two expressions that the value of m generally shows a linear decreasing trend. In the early stages of iteration, the algorithm repeatedly applies random search strategies to prevent premature convergence due to population clustering, enhance the exploration capability of honey badgers across the search space, and improve global search performance.

The mathematical expressions for the digging phase and the honey phase of the Honey Badger Algorithm at the current stage are given as follows:

where .

3.3. Population Remains the Best Value Unchanged After Three Iterations, Elite Tangent Search and Differential Variation Strategy Are Executed

During each iteration, the population is divided into two subpopulations: the first half, consisting of individuals with lower fitness values, is designated as the elite subpopulation, while the second half serves as the exploration subpopulation. The elite subpopulation then executes the elite migration strategy.

3.3.1. Migration Strategy of Elite Subpopulation

When an individual approaches the current optimal solution, it explores the surrounding region—a behavior referred to as local search—which enhances convergence speed and solution accuracy. Since the fitness of the elite subpopulation is close to the current global best solution, enabling it to perform local search can improve the convergence rate and solution precision. The migration strategy of the elite subpopulation [54] involves updating the position by incorporating the Tangent Search Algorithm [55] (TSA). The mathematical formulation of the elite tangent search strategy is given as follows:

Due to the perturbation applied to elite individuals, the original position is transformed to a new position .

3.3.2. Exploration of Subpopulation Evolution Strategies

In the Honey Badger Algorithm, the position updating mechanism generates new individuals in the vicinity of the current individual and the current global best individual . In other words, other individuals in the population are guided toward the global best solution. However, if this solution is a local optimum, continued iterations may cause the honey badger individuals to converge around it, resulting in reduced population diversity and increasing the risk of premature convergence. To address these issues, a differential mutation strategy is adopted. Inspired by the mutation strategy in differential evolution, the current individual, the global best individual, and randomly selected individuals from the population are used to perform differentiation in order to generate new individuals. This process is described by the following equation:

where is the scaling factor for differential evolution; t denotes the current iteration number; and represent three randomly selected honey badger individuals.

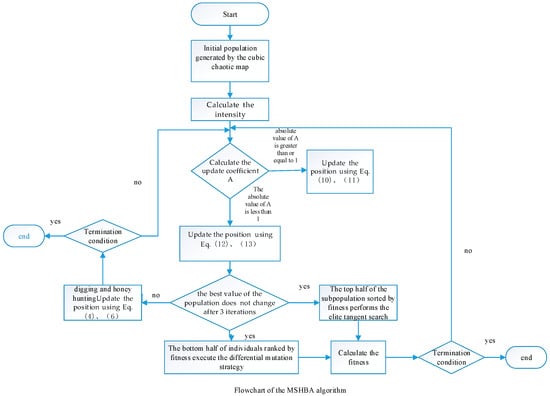

The flowchart of the MSHBA algorithm is shown in Figure 1. Algorithm 1 presents the pseudocode of MSHBA.

| Algorithm 1 Pseudo Code of MSHBA |

| Set parameters , . Initialize population using Equations (7) and (8) while do Update the decreasing factor using (3). for i = 1 to N do Calculate the intensity using Equation (2). Calculate using Equation (9). if Update the position using Equations (10) and (11). else Update the position using Equations (5) and (6). end. If the best value of the population does not change after 3 iterations The first half of the subpopulation performs the elite tangent search strategy. Update the position using Equations (12) and (13). The second half of the subpopulation performs the differential mutation strategy. Update the position using Equation (14). else digging and honey hunting Update the position using Equations (4) and (6) end If stop criteria satisfied. Output the optimal solution. else return Calculate using Equation (9). end |

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the MSHBA algorithm.

4. Experimental Results and Discussion

The experiments were conducted on the Windows 10 operating system. All algorithms were implemented using MATLAB R2023b. The performance of the IHBA was compared with that of recently developed metaheuristics to evaluate its effectiveness in global optimization. The numerical efficiency of MSHBA was evaluated using 29 benchmark functions from CEC 2017 and four engineering design problems. To validate the performance of MSHBA, the results were compared with four state-of-the-art optimization algorithms: COA [30], DBO [31], HHO [32], and OOA [33]. Among the selected competitive algorithms, COA, DBO, HHO, and OOA are swarm intelligence algorithms widely recognized in the metaheuristic literature. On the other hand, COA, DBO, HHO, and OOA are relatively recent algorithms that have demonstrated promising performance in addressing the optimization problems considered in this study. These methods were selected to include both well-established and recently proposed algorithms, ensuring a fair comparison to demonstrate the overall effectiveness of the proposed approach. For a fair comparison, a maximum of 500 iterations was set for each optimization problem.

4.1. Parameter Settings

Apart from the algorithm-specific parameter settings and the dimensions of the test functions listed in Table 1 and Table 2, the general settings common to all selected algorithms include a population size of 30 (), a maximum of 500 iterations (), and 30 independent runs for each optimization problem.

Table 1.

Summary of the CEC ’2017 test functions.

Table 2.

Parameters settings of IHBA and selected algorithm.

4.2. Benchmark Testing Functions

The performance of the Improved Honey Badger Optimization Algorithm is evaluated using the CEC2017 benchmark functions, which are categorized into unimodal functions, basic multimodal functions, hybrid functions, and composite functions, as presented in the Table 1 below.

Function F2 has been excluded from the benchmark set, as it exhibits unstable behavior, particularly in high-dimensional cases, and shows significant variations in performance when the same algorithm is implemented in MATLAB.

4.3. Comparison of MSHBA Algorithm with Other Algorithms

Table 3 demonstrates that the MSHBA algorithm achieves superior performance in terms of minimum, worst-case, median, average, and standard deviation (std) values on the unimodal functions F1 and F3, compared to the Raccoon Optimization Algorithm (COA), Dung Beetle Optimization (DBO), Harris Hawk Optimization (HHO), Osprey Optimization Algorithm (OOA), and the original Honey Badger Algorithm (HBA). These results indicate a significant improvement in the performance of the enhanced Honey Badger Algorithm (MSHBA).

Table 3.

Unimodal functions.

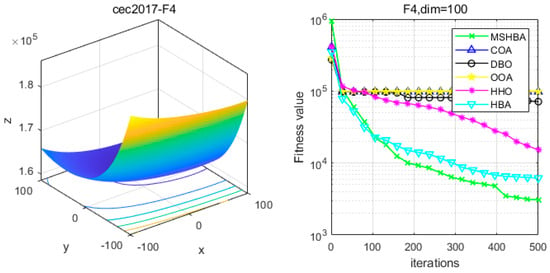

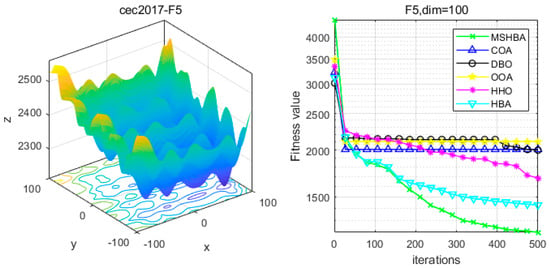

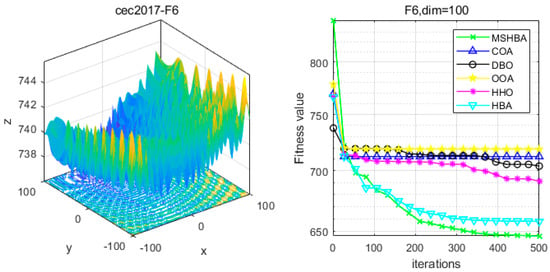

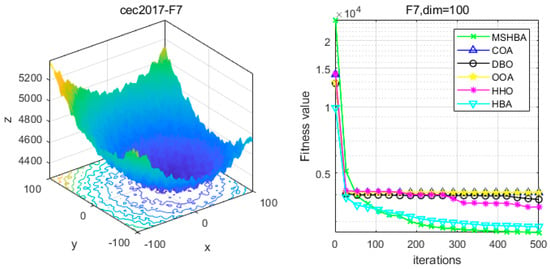

Table 4 shows that the MSHBA algorithm outperforms the Raccoon Optimization Algorithm (COA), Dung Beetle Optimization (DBO), Harris Hawk Optimization (HHO), Osprey Optimization Algorithm (OOA), and the original Honey Badger Algorithm (HBA) when tested on a set of multimodal functions (F4–F10), in terms of minimum, worst-case, median, average, and standard deviation (std) values.

Table 4.

Simple multimodal functions.

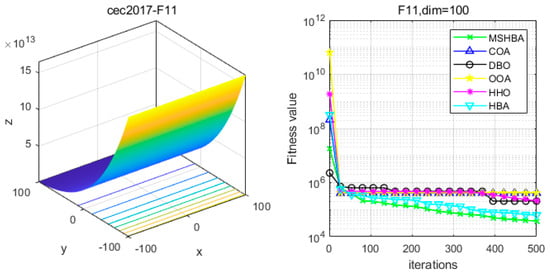

From Table 5, it can be seen that the MSHBA algorithm exhibits superior performance min, worst, median, average, and std on the hybrid function set F11–F20 compared to other algorithms such as Raccoon Optimization Algorithm (COA), Beetle Optimization Algorithm (DBO), Harris Hawk Optimization (HHO), Ospry Optimization Algorithm (OOA), Honey Badger Algorithm (HBA).

Table 5.

Hybrid functions.

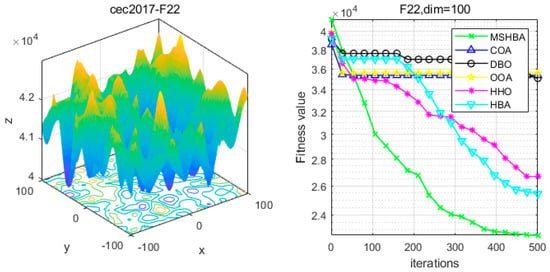

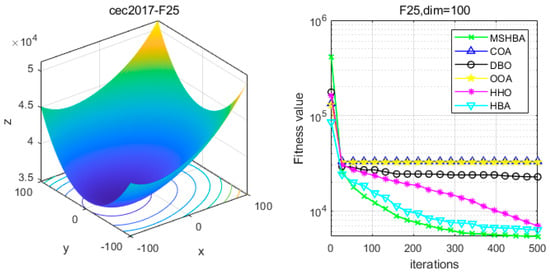

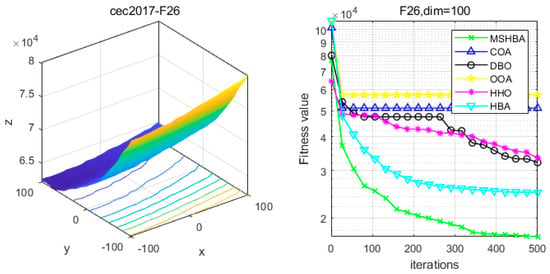

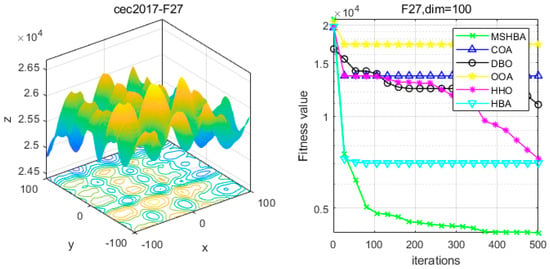

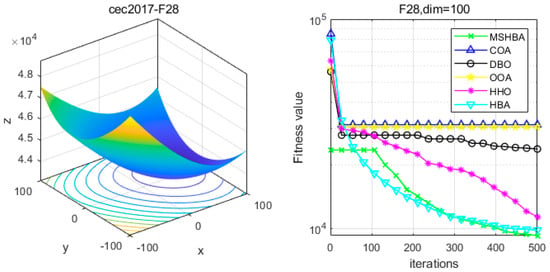

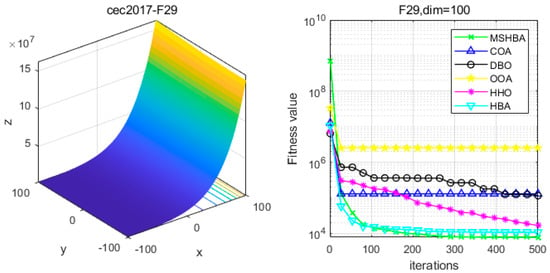

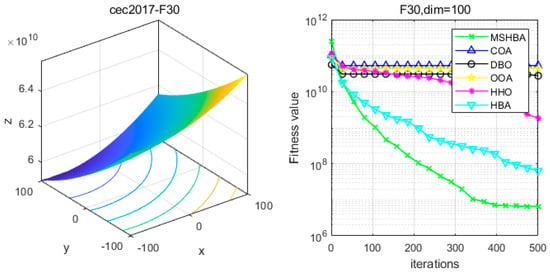

Table 6 shows that the MSHBA algorithm demonstrates superior performance in terms of minimum, worst-case, median, average, and standard deviation (std) values on the hybrid functions F21, F23, F24, F26, and F30, compared to other algorithms such as the Raccoon Optimization Algorithm (COA), Dung Beetle Optimization (DBO), Harris Hawk Optimization (HHO), Osprey Optimization Algorithm (OOA), and the original Honey Badger Algorithm (HBA). However, its performance in terms of variance is slightly inferior to that of COA on function F22, and to that of HBA on functions F25 and F29. Additionally, the mean and variance performances are slightly weaker than those of HBA on functions F27 and F28.

Table 6.

Composition functions.

4.4. MSHBA and Other Algorithms’ Rank-Sum Test

Table 7 shows that the Multi-Strategy Honey Badger Optimization Algorithm (MSHBA) demonstrates significantly superior performance compared to the other four algorithms (COA, DBO, OOA, and HHO) on test functions F1 and F3–F30, according to the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, as the obtained p-values are significantly lower than the given significance level. Overall, the improved algorithm outperforms the other four algorithms. However, on test functions F1, F12, F15, F18, F19, F20, F22, F25, F27, F28, and F29, the performance of the improved Honey Badger Algorithm is comparable to that of the original Honey Badger Algorithm. In general, the performance of the Honey Badger Algorithm has been significantly enhanced by introducing hybrid strategy operators.

Table 7.

Rank-sum test.

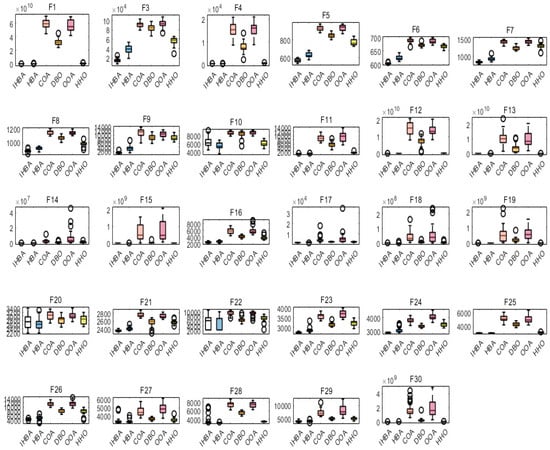

4.5. MSHBA and Other Algorithms of Boxplot

Figure 2 Boxplot Comparison of MSHBA with Other Algorithms outperforms the Raccoon Optimization Algorithm (COA), Dung Beetle Optimization (DBO), Harris Hawk Optimization (HHO), Osprey Optimization Algorithm (OOA), and the original Honey Badger Algorithm (HBA) on the CEC2017 test functions F3, F5–F9, F12, F13, F15–F19, F21, F23, F24, F26, F27, and F29.

Figure 2.

Boxplot Comparison of MSHBA with Other Algorithms.

However, on functions F1, F4, F11, F14, F22, F25, and F30, MSHBA performs comparably to or slightly worse than the original Honey Badger Algorithm (HBA). On functions F10, F20, and F28, its performance is similar to that of HHO.

Overall, the improved Honey Badger Algorithm demonstrates enhanced optimization performance on the majority of the benchmark functions.

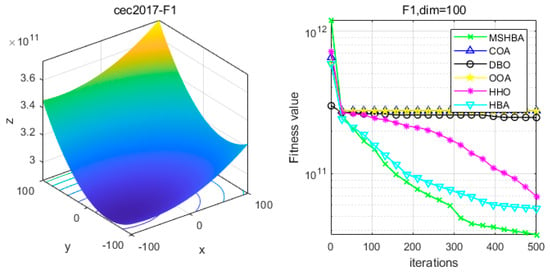

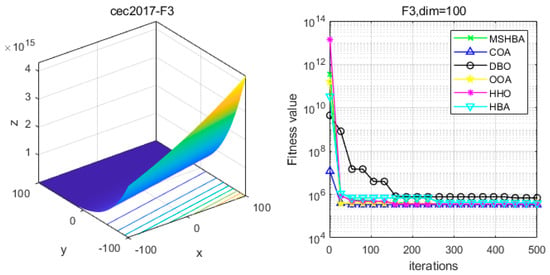

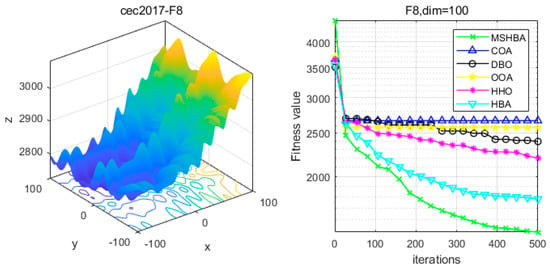

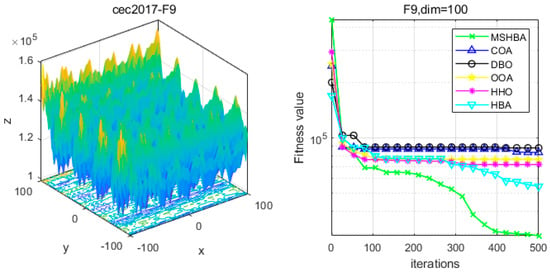

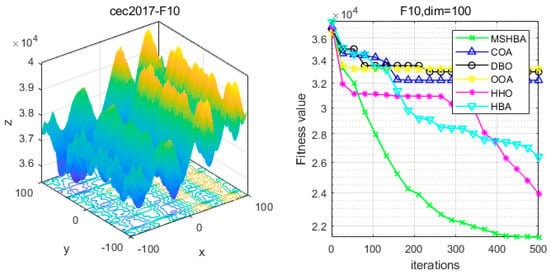

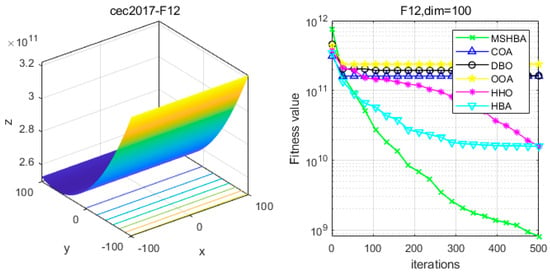

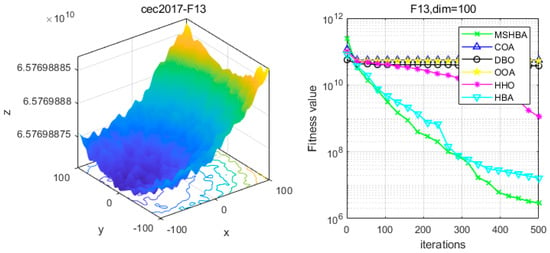

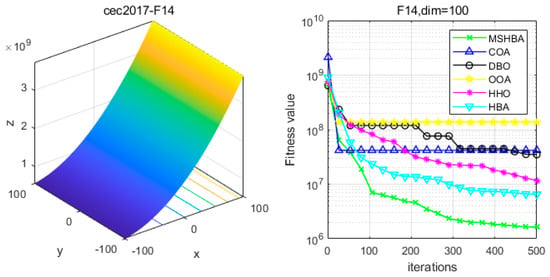

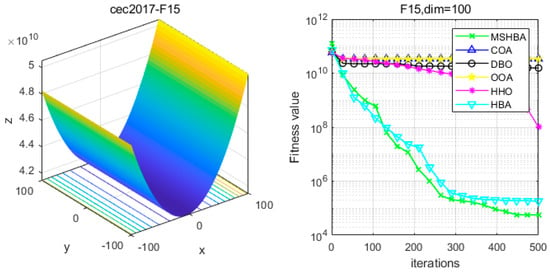

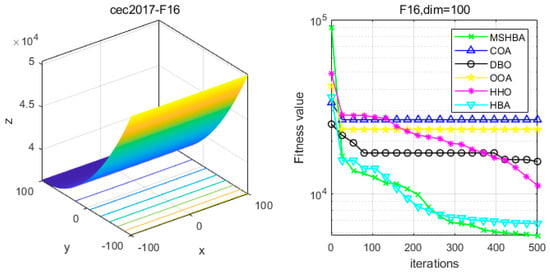

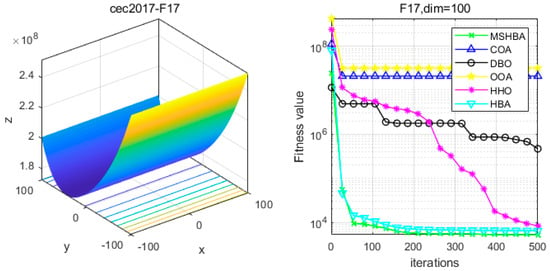

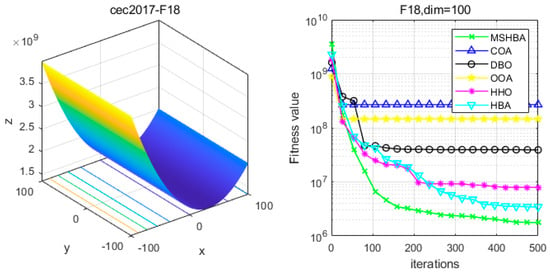

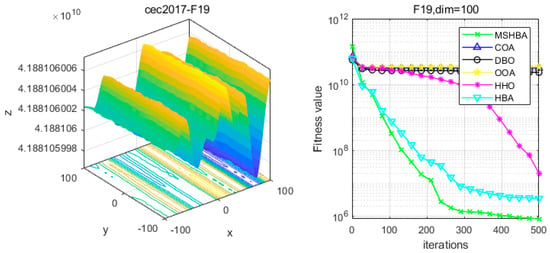

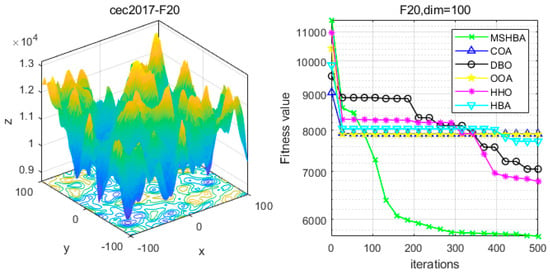

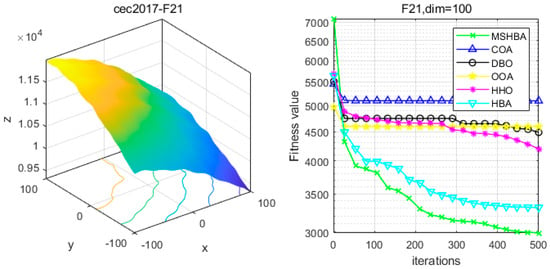

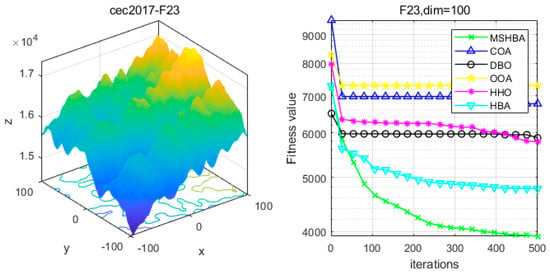

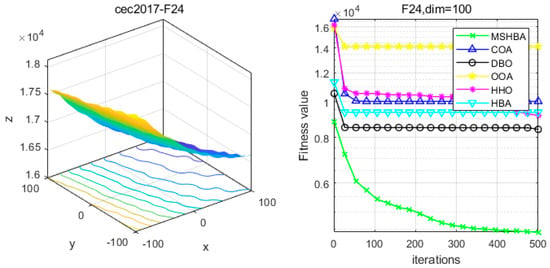

4.6. MSHBA for Test Function of Fitness Change Curve

The Multi-Strategy Honey Badger Algorithm (MSHBA) demonstrates superior convergence performance compared to the other five algorithms—COA, DBO, OOA, HHO, and HBA—on 29 benchmark functions, including F1 and F3–F19, F21–F30 (Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17, Figure 18, Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21, Figure 22, Figure 23, Figure 24, Figure 25, Figure 26, Figure 27, Figure 28, Figure 29, Figure 30 and Figure 31). Specifically, MSHBA outperforms COA, DBO, OOA, and HHO on functions F3, F20, and F29. Overall, the improved Honey Badger Algorithm exhibits significantly enhanced convergence behavior compared to the original HBA.

Figure 3.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F1 Test Function.

Figure 4.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F3 Test Function.

Figure 5.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F4 Test Function.

Figure 6.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F5 Test Function.

Figure 7.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F6 Test Function.

Figure 8.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F7 Test Function.

Figure 9.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F8 Test Function.

Figure 10.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F9 Test Function.

Figure 11.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F10 Test Function.

Figure 12.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F11 Test Function.

Figure 13.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F12 Test Function.

Figure 14.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F13 Test Function.

Figure 15.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F14 Test Function.

Figure 16.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F15 Test Function.

Figure 17.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F16 Test Function.

Figure 18.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F17 Test Function.

Figure 19.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F18 Test Function.

Figure 20.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F19 Test Function.

Figure 21.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F20 Test Function.

Figure 22.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F21 Test Function.

Figure 23.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F22 Test Function.

Figure 24.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F23 Test Function.

Figure 25.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F24 Test Function.

Figure 26.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F25 Test Function.

Figure 27.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F26 Test Function.

Figure 28.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F27 Test Function.

Figure 29.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F28 Test Function.

Figure 30.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F29 Test Function.

Figure 31.

Convergence Performance Comparison of CEC2017-F30 Test Function.

5. MSHBA for Solving Classical Engineering Problems

5.1. Weight Minimization of a Speed Reducer (WMSR) [51]

The reducer weight minimization problem is a typical engineering optimization problem, with the objective of achieving weight reduction in the reducer by optimizing design variables while satisfying a series of design constraints. The weight of the reducer depends on 11 constraints, which must be minimized. Among them, seven are nonlinear constraints, and the remaining four are linear constraints. The design variables include gear face width , gear module , number of teeth on the pinion , bearing span of the first shaft , bearing span of the second shaft , diameter of the first shaft , and diameter of the second shaft . The mathematical model is established as follows:

Minimize

subject to

with bounds

5.2. Tension/Compression Spring Design (TCSD) [52]

The design of tension/compression springs is a classic engineering optimization problem. The objective is to optimize the structural parameters of the spring to achieve minimum mass or optimal performance, while satisfying specific mechanical properties and spatial requirements. The design variables include wire diameter , mean coil diameter , and number of active coils . The constraints are shear stress constraint, spring vibration frequency constraint, and minimum deflection constraint. The established mathematical model is as follows:

Minimize

subject to

with bounds

5.3. Pressure Vessel Design (PVD) [52]

Pressure vessel design is a classic engineering optimization problem. The objective is to optimize the structural parameters of the pressure vessel to achieve cost minimization or performance optimization, while satisfying specific mechanical properties and safety standards. The design variables include shell thickness , head thickness , inner radius , and shell length . The constraints include thickness requirements, stress constraints, safety standard constraints, and geometric constraints. The established mathematical model is as follows:

Minimize

subject to

where

with bounds

5.4. Welded Beam Design (WBD) [52]

Welded beam design is a classic engineering optimization problem. The objective is to optimize the structural parameters of the welded beam to achieve the minimization of manufacturing costs or the optimization of performance, while satisfying specific mechanical properties and safety standards. The design variables include weld thickness , length of the beam attached to the support , height of the beam , and thickness of the beam . The constraints include shear stress constraint, bending stress constraint, buckling load constraint, end deflection constraint of the beam, and geometric constraints. The established mathematical model is as follows:

Minimize

subject to

where

with bounds

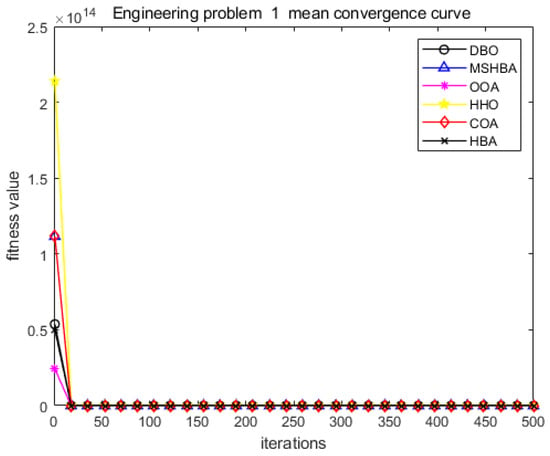

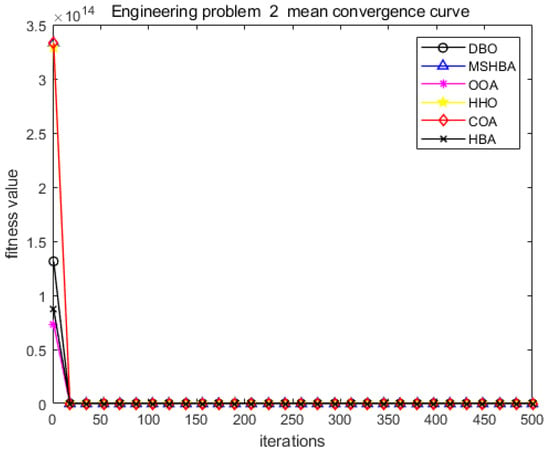

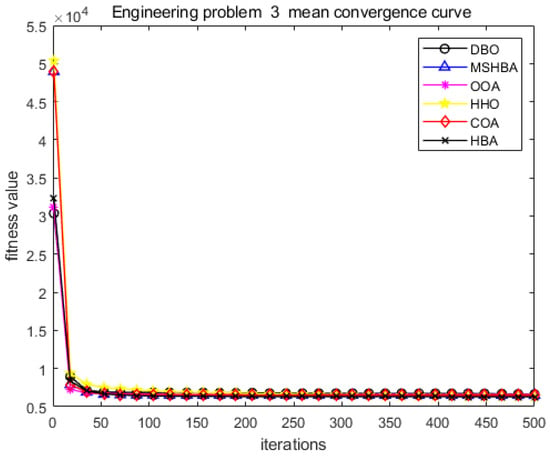

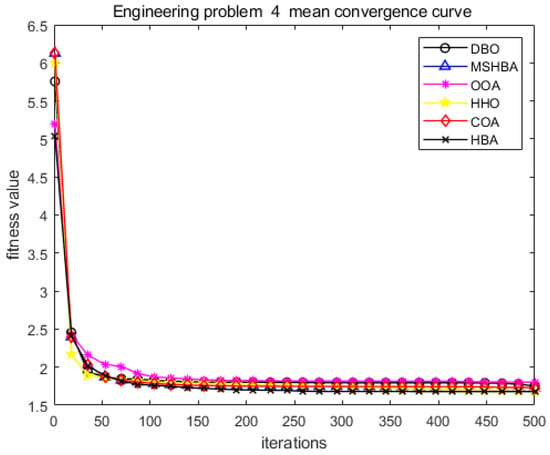

The MSHBA algorithm demonstrates strong convergence performance and stability when solving constrained engineering design problems, as evidenced by the results presented in Table 8, Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11 and Figure 32, Figure 33, Figure 34 and Figure 35. Additionally, it can be observed from Table 12, Table 13, Table 14 and Table 15 that the decision variables achieve optimal solutions when the objective function reaches its optimum. The algorithm is capable of reaching the optimal objective function value during the initial iterations and demonstrates excellent stability. In summary, the improved Honey Badger Algorithm demonstrates outstanding performance in solving constrained engineering design problems.

Table 8.

Statistical results of competitor algorithms for WMSR problem.

Table 9.

Statistical results of competitor algorithms for TCSD problem.

Table 10.

Statistical results of competitor algorithms for PVD problem.

Table 11.

Statistical results of competitor algorithms for WBD problem.

Figure 32.

Convergence curve of problem 1.

Figure 33.

Convergence curve of problem 2.

Figure 34.

Convergence curve of problem 3.

Figure 35.

Convergence curve of problem 4.

Table 12.

Statistical competition algorithm for solving WMSR problem.

Table 13.

Statistical competition algorithm for solving TCSD problem.

Table 14.

Statistical competition algorithm for solving PVD problem.

Table 15.

Statistical competition algorithm for solving WBD problem.

6. Conclusions and Future Works

This paper proposes a hybrid strategy to enhance the performance of the Honey Badger Optimization Algorithm. Performance analysis further confirms the superior performance of MSHBA, as evidenced by its improved convergence rate and enhanced exploration–exploitation balance. However, the proposed Multi-Strategy Honey Badger Algorithm (MSHBA) employs a hybrid strategy to enhance the performance of the original Honey Badger Algorithm (HBA). Specifically, it introduces a cubic chaotic map during population initialization to improve the diversity and exploration capability of the initial population. In the excavation and honey-searching stages of the Honey Badger Algorithm, the position update mechanism relies on the global best solution, potentially resulting in premature convergence caused by population clustering around the optimal individuals. In order to improve the global exploration capability of the Honey Badger Algorithm, a random search strategy is incorporated to enhance convergence speed and computational efficiency in the later iterations.

In subsequent studies, the proposed MSHBA algorithm will be further assessed for its effectiveness in addressing multi-objective, combinatorial, and real-world optimization problems with complex and uncertain search spaces. Furthermore, integrating hybrid strategies and parameter adaptation techniques into the traditional Honey Badger Algorithm (HBA) can enhance its capabilities in binary and multi-objective optimization. This approach aims to improve solution accuracy, achieve a better balance between exploration and exploitation, and accelerate global convergence, thereby enabling the algorithm to effectively solve a wide range of optimization problems.

Author Contributions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, D.G. and H.H.; methodology, D.G.; software, D.G.; validation, D.G. and H.H.; formal analysis, D.G.; investigation, D.G.; resources, D.G.; data curation, D.G.; writing—original draft preparation, D.G.; writing—review and editing, H.H.; visualization, D.G.; supervision, D.G.; project administration, D.G.; funding acquisition, H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by [2024 Open Fund Projects to be Funded by the Guangxi Key Laboratory of Hybrid Computing and Integrated Circuit Design Analysis] grant number [GXIC2402]. And the APC was funded by [2024 Open Fund Projects to be Funded by the Guangxi Key Laboratory of Hybrid Computing and Integrated Circuit Design Analysis].

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article: Theoriginal contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the Data Availability Statement. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

References

- Houssein, E.H.; Helmy, B.E.-D.; Rezk, H.; Nassef, A.M. An enhanced archimedes optimization algorithm based on local escaping operator and orthogonal learning for PEM fuel cell parameter identification. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2021, 103, 104309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houssein, E.H.; Mahdy, M.A.; Fathy, A.; Rezk, H. A modified marine predator algorithm based on opposition based learning for tracking the global MPP of shaded PV system. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 183, 115253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, C. Introduction to Stochastics Search and Optimization; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Parejo, J.A.; Ruiz-Cortés, A.; Lozano, S.; Fernandez, P. Metaheuristic optimization frameworks: A survey and benchmarking. Soft Comput. 2012, 16, 527–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.H.; Houssein, E.H.; Mahdy, M.A.; Kamel, S. An improved manta ray foraging optimizer for cost-effective emission dispatch problems. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2021, 100, 104–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.M.; Houssein, E.H.; Hassanien, A.E.; Taha, A.; Hassanien, E. Maximizing lifetime of large-scale wireless sensor networks using multi-objective whale optimization algorithm. Telecommun. Syst. 2019, 72, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houssein, E.H.; Helmy, B.E.-D.; Oliva, D.; Elngar, A.A.; Shaban, H. A novel black widow optimization algorithm for multilevel thresholding image segmentation. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 167, 114159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, K.; Neggaz, N.; Zhu, W.; Houssein, E.H. An efficient hybrid sine-cosine harris hawks optimization for low and high-dimensional feature selection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 176, 114778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neggaz, N.; Houssein, E.H.; Hussain, K. An efficient henry gas solubility optimization for feature selection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 152, 113364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanien, A.E.; Kilany, M.; Houssein, E.H.; AlQaheri, H. Intelligent human emotion recognition based on elephant herding optimization tuned support vector regression. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2018, 45, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, F.A.; Houssein, E.H.; Hussain, K.; Mabrouk, M.S.; Al-Atabany, W. A modified henry gas solubility optimization for solving motif discovery problem. Neural Comput. Appl. 2019, 32, 10759–10771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadollah, A.; Sayyaadi, H.; Yadav, A. A dynamic metaheuristic optimization model inspired by biological nervous systems: Neural network algorithm. Appl. Soft Comput. 2018, 71, 747–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, F.; Zain, A.M.; Zhou, K.-Q. Harmony search algorithm and related variants: A systematic review. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2022, 74, 101126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualigah, L.; Diabat, A.; Geem, Z.W. A Comprehensive Survey of the Harmony Search Algorithm in Clustering Applications. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeev, S.; Krishnamoorthy, C.S. Discrete optimization of structures using genetic algorithms. J. Struct. Eng. 1992, 118, 1233–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storn, R.; Price, K. Differential evolution–A simple and efficient heuristic for global optimization over continuous spaces. J. Glob. Optim. 1997, 11, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houssein, E.H.; Rezk, H.; Fathy, A.; Mahdy, M.A.; Nassef, A.M. A modified adaptive guided differential evolution algorithm applied to engineering applications. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 113, 104920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atashpaz-Gargari, E.; Lucas, C. Imperialist competitive algorithm: An algorithm for optimization inspired by imperialistic competition. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation, Singapore, 25–28 September 2007; pp. 4661–4667. [Google Scholar]

- Priya, R.D.; Sivaraj, R.; Anitha, N.; Devisurya, V. Tri-staged feature selection in multi-class heterogeneous datasets using memetic algorithm and cuckoo search optimization. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 209, 118286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorigo, M.; Birattari, M.; Stutzle, T. Ant colony optimization-Artificial ants as a computational intelligence technique. IEEE Comput. Intell. Mag. 2006, 1, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Lei, L.; Yu, F.; Heidari, A.A.; Wang, M.; Oliva, D.; Muhammad, K.; Chen, H. Ant colony optimization with horizontal and vertical crossover search: Fundamental visions for multi-threshold image segmentation. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2021, 167, 114122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of the ICNN’95-International Conference on Neural Networks, Perth, WA, Australia, 27 November–1 December 1995; pp. 1942–1948. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, M.; Wu, J.; Shi, Y.; Yue, L.; Yang, C.; Chen, X. Chaotic Random Opposition-Based Learning and Cauchy Mutation Improved Moth-Flame Optimization Algorithm for Intelligent Route Planning of Multiple UAVs. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 49385–49397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Wu, X. Ensemble grey wolf Optimizer and its application for image segmentation. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 209, 118267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L. Manta ray foraging optimization: An effective bio-inspired optimizer for engineering applications. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2020, 87, 103300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Wang, L.; Mirjalili, S. Artificial hummingbird algorithm: A new bio-inspired optimizer with its engineering applications. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2022, 388, 114194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agushaka, J.O.; Ezugwu, A.E.; Abualigah, L. Dwarf Mongoose Optimization Algorithm. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2022, 391, 114570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahzadeh, B.; Gharehchopogh, F.S.; Mirjalili, S. Artificialgorilla troops optimizer: A new nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm for global optimization problems. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2021, 36, 5887–5958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houssein, E.H.; Saad, M.R.; Ali, A.A.; Shaban, H. An efficient multi-objective gorilla troops optimizer for minimizing energy consumption of large-scale wireless sensor networks. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 212, 118827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, T.; Ma, S.; Chen, M. Dandelion Optimizer: A nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm for engineering applications. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 114, 105075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beşkirli, M. A novel Invasive Weed Optimization with levy flight for optimization problems: The case of forecasting energy demand. Energy Rep. 2022, 8 (Suppl. S1), 1102–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashedi, E.; Nezamabadi-Pour, H.; Saryazdi, S. GSA: A Gravitational Search Algorithm. Inf. Sci. 2009, 179, 2232–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Wang, L.; Lin, Y.; Hei, X.; Yu, G.; Lu, X. An efficient multi-objective artificial raindrop algorithm and its application to dynamic optimization problems in chemical processes. Appl. Soft Comput. 2017, 58, 354–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houssein, E.H.; Hosney, M.E.; Mohamed, W.M.; Ali, A.A.; Younis, E.M.G. Fuzzy-based hunger games search algorithm for global optimization and feature selection using medical data. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 35, 5251–5275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houssein, E.H.; Oliva, D.; Çelik, E.; Emam, M.M.; Ghoniem, R.M. Boosted sooty tern optimization algorithm for global optimization and feature selection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 113, 119015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Du, B.; Wang, X.; Wei, G. An enhanced black widow optimization algorithm for feature selection. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 235, 107638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualigah, L.; Almotairi, K.H.; Elaziz, M.A. Multilevel thresholding image segmentation using meta-heuristic optimization algorithms: Comparative analysis, open challenges and new trends. Appl. Intell. 2022, 53, 11654–11704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houssein, E.H.; Hussain, K.; Abualigah, L.; Elaziz, M.A.; Alomoush, W.; Dhiman, G.; Djenouri, Y.; Cuevas, E. An improved opposition-based marine predators algorithm for global optimization and multilevel thresholding image segmentation. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 229, 107348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Dinkar, S.K. A Linearly Adaptive Sine–Cosine Algorithm with Application in Deep Neural Network for Feature Optimization in Arrhythmia Classification using ECG Signals. Knowl. Based Syst. 2022, 242, 108411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Tian, X.; Fang, G.; Xu, Y.-P. Many-objective optimization with improved shuffled frog leaping algorithm for inter-basin water transfers. Adv. Water Resour. 2020, 138, 103531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.K.; Behera, H.S.; Panigrahi, B.K. A hybridization of an improved particle swarm optimization and gravitational search algorithm for multi-robot path planning. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2016, 28, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Jiang, N.; Wang, X.; Li, M. A hybrid algorithm based on grey wolf optimizer and differential evolution for UAV path planning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 215, 119327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Wang, G.-G.; Pedrycz, W. Solving fuzzy job-shop scheduling problem using DE algorithm improved by a selection mechanism. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 28, 3265–3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.R.; Bian, X.Y.; Zhao, S. Ship pipe route design using improved multi-objective ant colony optimization. Ocean. Eng. 2022, 258, 111789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Wang, J.; Li, M.; Hussien, A.G.; Abbas, M. EJS: Multi-strategy enhanced jellyfish search algorithm for engineering applications. Mathematics 2023, 11, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpert, D.H.; Macready, W.G. No free lunch theorems for optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 1997, 1, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, M.; Jolai, F. Lion optimization algorithm (LOA): A nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2016, 3, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, F.A.; Houssein, E.H.; Hussain, K.; Mabrouk, M.S.; Al-Atabany, W. Honey Badger Algorithm: New metaheuristic algorithm for solving optimization problems. Math. Comput. Simul. 2022, 192, 84–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochert, C.; Scheuermann, B.; Mauve, M. A Survey on congestion control for mobile ad-hoc networks. Wiley Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2007, 7, 655–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.F.; Zhan, H.W.; Huang, W.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Z.X. Development of Levy Flight and Its Application in Intelligent Optimization Algorithm. Comput. Sci. 2021, 48, 190–206. [Google Scholar]

- Pant, M.; Thangaraj, R.; Singh, V. Optimization of mechanical design problems using improved differential evolution algorithm. Int. J. Recent Trends Eng. 2009, 1, 21. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Zhou, Y. Enhancing the performance of differential evolution with covariance matrix self-adaptation. Appl. Soft Comput. 2018, 64, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahi, A.; Bekkouche, T.; Daachi, M.E.H.; Diffellah, N. A color image encryption scheme based on 1D cubic map. Optik 2022, 249, 168290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Xia, X. Random perturbation subsampling for rank regression with massive data. Stat. Sci. 2024, 35, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, H.; Yong, C.; Peng, C. Improved Honey Badger Algorithm Based on Elite Tangent Search and Differential Mutation with Applications in Fault Diagnosis. Processes 2025, 13, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).