Abstract

Alpha-gal syndrome (AGS) is an emerging, relatively newly recognized allergic disorder with clinical manifestations that occur as a result of hypersensitivity reactions to oligosaccharide galactose-α-1,3-galactose (α-gal), a carbohydrate present in lower-mammalian meat, dairy products, and some biopharmaceutical products. These reactions are delayed with oral ingestion of the antigen but can be immediate with intravascular or other parenteral antigenic exposure. Over the past 15 years, many revelations have occurred in the realm of AGS. However, there is still a huge unmet need related to its pathophysiology, diagnostics, timely recognition, and management. This article is geared towards providing a review of AGS for healthcare providers (HCPs) from all realms of medicine. It is a universal challenge, with cases being recognized from various parts of the world. Hence, it is critically important for HCPs planet-wide to pay heed to the prompt recognition of AGS and educate their patients. This can prevent morbidity as well as potentially fatal complications like severe anaphylaxis. It is a narrative clinical review. The PubMed database was searched from 2009 to 2025. Alpha-gal syndrome and related topics were included in the search engine.

1. Introduction and Pathophysiology

In 2008, Chung et al. published an association with cetuximab-induced anaphylaxis and alpha-gal [1]; subsequently, a link to tick bites was established [2]. Since then, AGS has been studied and reported globally with variation in the involved tick species: Ixodes ricinus in Europe, Haemaphysalis longicornis in Asia, Amblyomma americanum in the United States (U.S.), and Ixodes australiensis in Australia [3,4,5,6].

The underlying pathophysiology of AGS involves the development of α-gal-specific IgE, with evidence of altered T- and B-cell transcription [7], triggered by tick exposure. This sensitization is potentiated by the antigenic variability of tick saliva [8,9]. While most food allergies are immediate and protein/peptide-mediated, and have no previously established connection to tick exposure, AGS represents a paradigm shift, with (typically) delayed reactions uniquely mediated by a ‘carbohydrate’ epitope, and related to (as well as worsened by recurrent) tick bites. Hence, AGS is a unique example of a response to an ectoparasite giving rise to a significant food allergy, in addition to an allergic response to non-ingested items, e.g., personal products like lotion. Tick bites tend to induce IgE antibodies to a cross-reactive oligosaccharide.

2. Epidemiology

As per 28 July 2023, from the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report by The Centers for Disease Control (CDC), during 2017–2021, there was an annual increase in positive test results for AGS in the U.S.—more than 90,000 suspected AGS cases were identified during the study period, and the number of new suspected cases increased by approximately 15,000 each year during the study [10]. With climate and ecological changes driving the expansion of tick habitats [11,12], incidence is likely to rise further. The CDC has also endorsed a low level of healthcare provider awareness about AGS [13] leading to a significant delay in the diagnosis of AGS. Up to 2–3% of the residents in the most affected areas have AGS, and 35% or more of some populations in the U.S., e.g., in the southeastern states, are sensitized to alpha-gal, and the CDC’s estimate places AGS as the 10th most common food allergy in the U.S., appearing to be the leading cause of adult-onset food-allergy/anaphylaxis in certain datasets [14]. Epidemiological patterns show considerable heterogeneity. Swedish cohorts show associations between tick bites, B-negative blood groups, and red meat allergy, whereas U.S. surveillance points to an increasing pediatric burden and a very widespread occurrence [15,16,17]. Studies have shown high sensitization rates without clinical reactivity [18,19]. Also, α-gal IgE titers may wane with avoidance of tick exposure [20].

3. Clinical Features and Diagnosis

AGS is very heterogeneous and demonstrates a broad clinical spectrum.

The majority (~85%) of the patients with AGS present with the following ‘classical’ characteristics [21]:

- Onset in adult life despite eating mammalian meat for several years before;

- Symptoms ranging from itching (pruritus), localized urticaria (hives), or frank angioedema and anaphylaxis;

- Predominantly gastrointestinal symptoms (loose bowel movements, abdominal cramping, nausea and vomiting) without any significant skin, pulmonary, or cardiovascular manifestations;

- Symptoms starting 3–8 (occasionally 2–10) h after ingestion of non-primate mammalian meat, less commonly dairy, or other mammalian-derived products like gelatin. Reactions do occur much faster with parenteral route;

- Serum alpha-gal IgE level > 0.1 IU/mL using standard testing available in the U.S. (via Viracor-Eurofins) or Europe (via Phadia ThermoFisher);

- Improvement in symptoms upon compliance with appropriate nutritional and other ways of avoiding exposure to mammalian products;

- Large local reactions to bites from ticks or other arthropods. Often, patients can hone-in on an ‘index’ bite, which is different from prior bites.

The most important ‘non-classical’ symptoms of AGS pertain to the gastrointestinal (GI) tract [22]. Although GI symptoms can be a part of an allergic reaction, 3–20% of patients with AGS experience nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and/or heartburn in isolation of skin, cardiovascular, or other clinical features [7,15,23].

Less than 1% AGS patients can experience isolated oral pruritus or tongue-swelling [15]. Other conditions that also arise less commonly, and may not be causally related to AGS, include joint pain and chronic pruritus, the latter making it challenging to differentiate AGS from chronic spontaneous urticaria [15,24].

We have recently published AGS presenting as erythrodermic psoriasis that cleared-up rapidly with mammalian-product exclusion [25]. We have also related AGS and fibromyalgia in a series of American Indian patients, resolving with mammalian-product elimination [26]. So far, these are limited, hypothesis-generating case observations awaiting substantiation and reinforcement from the results of larger studies.

AGS symptoms can be more pronounced when mammalian meat exposure is paired with alcohol, stress, insomnia, intercurrent illness/infection, and menses [21].

Diagnosing AGS hinges on the recognition of delayed reactions combined with α-gal-specific IgE testing. Although, there is a paucity of established criteria regarding the titer of alpha-gal IgE to confirm a diagnosis of AGS, yet a cut-off of >0.1 IU/mL as a positive test result. It has a specificity of about 92% and sensitivity of close to 100% among AGS patients [27].

‘Seronegative’ AGS is a novel term used when there is a history of classical and/or non-classical AGS symptoms but the serum alpha-gal IgE test-result is negative. This situation can occur in about 2% of cases referred for evaluation of AGS [21]. In such cases, skin-prick and serum IgE testing for surrogate markers (beef, pork, and lamb) can be utilized.

The basophil activation test can help distinguish active allergy from asymptomatic sensitization [28]. A very pertinent review covers not only the current diagnostic methods used for AGS, such as the skin-prick test, but also the oral food challenge, serum anti-α-Gal IgE levels, and the basophil activation test [21]. Some potentially helpful next-generation diagnostic work-up includes the mast cell activation test, the histamine-release assay, genomics–proteomics–metabolomics technology, and model-based reasoning [29].

4. Overlap with Rheumatology

AGS is being recognized more and more in the field of allergy/immunology. However, its presence remains underappreciated in the related field of rheumatology. The symptoms of AGS, including skin rashes and arthralgia, may simulate a rheumatological condition. In a cross-sectional study from Johnston County, North Carolina, United States, performed to evaluate the potential associations between prior exposure to tick-borne diseases other than Lyme disease and musculoskeletal symptoms, only α-gal IgE was associated with knee pain, aching, or stiffness (mean ratio, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.09–1.56) [30].

In addition to frank rheumatic conditions like erythrodermic psoriasis [25] and fibromyalgia [26], we are observing the formation of several autoantibodies without full-blown systemic inflammatory immune-mediated rheumatic diseases in patients with AGS. It is still a preliminary observation with limited generalizability pending further larger systematic studies.

Certain medications not uncommonly used in the realm of rheumatology can present direct safety concerns. Several biologics and monoclonal antibodies contain mammalian components such as gelatin or bovine serum, and may be derived from non-primate mammalian cultures like Chinese Hamster Ovarian cell lines, which may provoke potentially severe allergic reactions in AGS patients [4,31]. One example is infliximab, a TNF-alpha inhibitor biologic widely prescribed in several rheumatological conditions including rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis. A case report described a 17-year-old patient, who, about six hours after the first infliximab infusion for Crohn’s disease, developed an intensely itchy, hive-like rash behind the ears, on the neck, and across the back. The reaction resolved within a few hours after taking oral diphenhydramine. For the subsequent infusions, the patient was pretreated with diphenhydramine and acetaminophen, which prevented immediate reactions during the infusion itself. However, four to six hours after each infusion, the patient consistently developed hives in varying locations. The symptoms resolved after discontinuation of infliximab [32]. Although this case involved the use of infliximab for inflammatory bowel disease and not a rheumatological condition, it highlights the need for caution when prescribing infliximab to rheumatological patients with AGS [33]. Importantly, Abatacept, a CTLA4Ig, a T-cell costimulatory blocker approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and other rheumatological indications has been associated with allergic reaction in AGS patients [21]. More commonly used medications in Rheumatology such as oral or injectable forms of NSAIDs (and even corticosteroids) may contain gelatin and can pose a risk [34].

Rheumatology clinics, especially in AGS endemic regions, like ours, are increasingly likely to encounter patients with undiagnosed AGS, given its clinical overlap with autoimmune systemic inflammatory disorders. Incorporating questions about tick exposure, allergic reactions, or worsening rheumatic symptoms after exposure to mammalian meat or products derived thereof can shorten diagnostic delay and improve patient outcomes. Maintaining a high index of suspicion allows clinicians to avoid unnecessary interventions and provide safer, more effective care.

5. Management

It is important to inform all patients that any further tick bites should be avoided because they can maintain or even increase the serum alpha-gal IgE level, potentially making the situation worse [2,22]. On the other hand, a significant proportion of the patients (close to 90%) who are able to avoid further tick bites successfully can experience a decline in their serum alpha-gal IgE level [20].

For all newly diagnosed patients with AGS, the primary advice is to completely avoid mammalian meat, which means beef, pork, venison, and lamb in most areas of the U.S. [35] Internal mammalian organs, especially pork kidney, should be avoided as well [36]. It is important to note that a higher fat content in the mammalian meat has been associated consistently with AGS symptoms and their severity [22,23,37].

If tolerating well, full avoidance of dairy products is typically not routinely included initially because a significant proportion (80–90%) of AGS patients do not react to milk or cheese [15,22,35]. However, if a patient’s AGS symptoms are not abated adequately by complete avoidance of exposure to mammalian meat, then, perhaps, full avoidance of dairy products can help [35]. All situations should be attentively addressed on a case-by-case basis.

It is important to consider ‘hidden’ forms of mammalian exposure if the patients continue to remain symptomatic despite elimination of all ‘obvious’ forms of alpha-gal exposure. The common ‘hidden’ forms include, but are not limited to, the use of products containing arachidyl propionate (wax made from mammalian fat), arachidonic acid (skin lotions and creams—typically isolated from the mammalian liver), glycerin, lanolin, oleic acid, and stearic acid.

In view of the varied forms of mammalian meat exposures as well as many ‘hidden’ forms that have not even been recognized so far, for a group of AGS patients who remain symptomatic despite their level best effort, adjunctive medical therapies including a very mindful use of oral antihistamines, oral cromolyn sodium, oral corticosteroids, or even omalizumab are implemented [21].

Iatrogenic AGS needs attention as well because medications, treatments, and devices that are mammalian-sourced or have inactive ingredients in them can lead to AGS [38]. Heparin is typically derived from porcine intestines, and heparin-induced allergic reactions have been deemed possible in patients with AGS [39,40].

It is important to understand that routine heparin prophylaxis for deep venous thrombosis (DVT) might not be as big an issue as when high-dose heparin is used for more complete anti-coagulation, e.g., during cardiac catheterization, valvular-procedures, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, etc., when the surgical team should be requested to assess risk-benefit ratio, and a standard pre-medication regimen using corticosteroid, antihistamine, and even omalizumab can be successful to reduce reactions to large doses of heparin; as well as using sodium citrate rather than heparin in patients with AGS for flushing their ports or central lines [21]. Gelatin-based capsules and lactose are usually not deleterious. However, the most severe anaphylaxis has been seen when gelatin is administered intravenously as a plasma expander [41,42]. Zostavax and MMR vaccines can also cause reactions due their gelatin content [43,44].

Pancreatic enzyme and thyroxine supplementation can also be fraught with reactions in AGS patients [21]. Bioprosthetic heart valves can induce allergic reactions [40], and even degeneration of mammalian cardiac valves has been observed in AGS patients [45]. Anti-venom formulations contain alpha-gal as they are typically derived from lower mammals after venom-immunization. Although an acute reaction to the antivenom can be seen in AGS patients [46,47], the expert recommendation is to consider the life-saving benefit of anti-venom until the true risk is more established in such a situation [21].

Readiness with epinephrine autoinjectors remains a cornerstone of safety [48].

6. Patients’ Challenges

Mammalian byproducts are added to foods, pharmaceuticals, personal care products (like lotion and make-up), and many other items. More than 20,000 drugs, vaccines, etc., contain mammalian byproducts. It can be challenging to know if any are present in food/medications despite checking labels, because no complete list exists. A significant proportion of patients have to modify their medications because of their AGS diagnosis. Up to 20% of AGS patients have contacted drug manufacturers asking about the ingredients more than 10 times. Only about 60% of the pharmaceutical companies provide an accurate response about mammalian-derived medication ingredients. It is humbling that more than 40% of the healthcare providers were not aware of AGS, and another 35% did not feel confident in diagnosing and managing AGS [13].

More than 1400 patients with AGS have petitioned the FDA to require drug manufacturers to clearly label whether ingredients used in their products are mammalian derived. If testing trends continue, and the geographic range of the lone star tick continues to expand, the number of AGS cases in the U.S. is predicted to increase during the coming years, presenting a critical need for synergistic public health activities, including (1) community education targeting tick bite prevention to reduce the risk for acquiring AGS, (2) healthcare provider education to improve timely diagnosis and management, and (3) improved surveillance to aid public health decision-making [14]. Future treatment and preventive tools are also discussed, being of utmost importance for the identification of tick salivary molecules, with or without α-Gal modifications that trigger IgE sensitivity as they could be the key for further vaccine development. Bearing in mind climate change, the tick-host paradigm will shift towards an increasing number of AGS cases in new regions worldwide, which will pose new challenges for clinicians in the future [29].

7. Conclusions

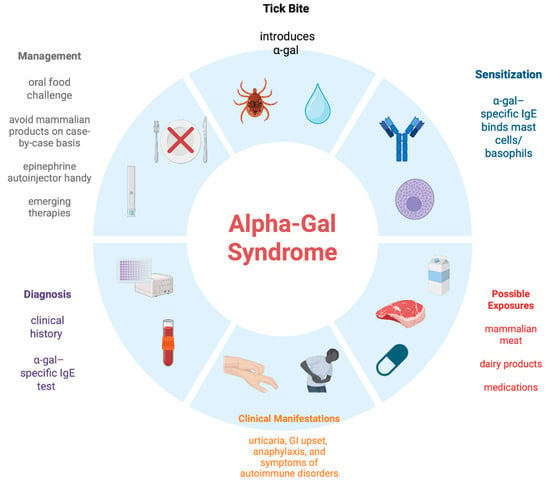

In the past decade and a half, the understanding of AGS has increased considerably. Unlike most food allergies, the causal antigen is not a protein, but an oligosaccharide, galactose-α-1,3-galactose, causing allergic reactions including anaphylaxis to products of non-primate mammalian origin. These reactions can be immediate (e.g., when certain pharmaceuticals are administered intravascularly), but more often (e.g., with oral intake of mammalian meat), there is a delay of several hours. It is critically important for primary care providers (PCPs), dermatologists, gastroenterologists, rheumatologists, emergency room physicians, and other HCPs to become aware of AGS because of its increasing prevalence, wide clinical spectrum, preventable nature, and potentially serious outcome if not recognized quickly enough. Patients presenting with unexplained anaphylaxis, recurrent urticarial lesions, angioedema, or gastrointestinal symptoms (especially with a temporal correlation with ingestion of mammalian meat several hours prior to the onset of symptoms, more so in tick-endemic areas) should have serum alpha-gal IgE levels measured (cut off of >0.1 IU/mL). Please refer to Figure 1 for a pictorial review of AGS.

Figure 1.

Alpha-gal Syndrome: A Pictorial Review [49].

Future Direction

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has been giving more and more attention to AGS. It can be useful to develop a repository of AGS-related information for patients and their community and healthcare providers. The cut-off of alpha-gal IgE testing might be different in different geographic areas based on background sensitization. Hence, some larger population-based studies are needed. Avoidance of exposure to the allergen (in this case, mammalian meat and the products derived thereof) is the prime tenet of AGS management. The Alpha-gal Alliance is trying to increase the transparency in the labeling of foods/pharmaceuticals/vaccines. Ongoing research into immunologic mechanisms, diagnostic tools, and targeted therapies is essential to better the understanding of AGS. One seminal article on the key independent mechanistic work [50] and one initial review article [51] on AGS are strongly recommended to the readers by the authors of this article.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.K., methodology, P.K.; software, P.K., F.S.B. and T.B.; validation, All authors; formal analysis, P.K., investigation, All authors; resources, All authors; data curation, All authors; writing—original draft preparation, P.K. and F.S.B.; writing—review and editing, P.K.; visualization, T.B.; supervision, P.K.; project administration, P.K.; funding acquisition, none. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Authors express their gratitude to the Alpha-gal Alliance action fund [2], a nonprofit advocacy partner of the Alpha-gal Alliance: www.alphagalaction.org.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chung, C.H.; Mirakhur, B.; Chan, E.; Le, Q.-T.; Berlin, J.; Morse, M.; Murphy, B.A.; Satinover, S.M.; Hosen, J.; Mauro, D.; et al. Cetuximab-induced anaphylaxis and IgE specific for galactose-α-1,3-galactose. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Commins, S.P.; James, H.R.; Kelly, L.A.; Pochan, S.L.; Workman, L.J.; Perzanowski, M.S.; Kocan, K.M.; Fahy, J.V.; Nganga, L.W.; Ronmark, E.; et al. The relevance of tick bites to the production of IgE antibodies to α-gal. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 127, 1286–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamsten, C.; Tran, T.A.T.; Starkhammar, M.; Brauner, A.; Commins, S.P.; Platts-Mills, T.A.E.; van Hage, M. Red meat allergy in Sweden: Association with tick sensitization and B-negative blood groups. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 132, 1431–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinuki, Y.; Ishiwata, K.; Yamaji, K.; Takahashi, H.; Morita, E. Haemaphysalis longicornis tick bites are a possible cause of red meat allergy in Japan. Allergy 2016, 71, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, M.; Somerville, C.; van Nunen, S. A novel Australian tick Ixodes australiensis inducing mammalian meat allergy after tick bite. Asia Pac. Allergy 2018, 8, e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nunen, S.A.; O’Connor, K.S.; Clarke, L.R.; Boyle, R.X.; Fernando, S.L. An association between tick bite reactions and red meat allergy in humans. Med. J. Aust. 2009, 190, 510–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iweala, O.I.; Choudhary, S.K.; Addison, C.T.; Commins, S.P. T and B lymphocyte transcriptional states differentiate between sensitized and unsensitized individuals in alpha-gal syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crispell, G.; Commins, S.P.; Archer-Hartman, S.A.; Choudhary, S.; Dharmarajan, G.; Azadi, P.; Karim, S. Discovery of alpha-gal-containing antigens in North American tick species believed to induce red meat allergy. Front Immunol. 2019, 10, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Ruiz, L.P.; Reif, K.E.; Ghosh, A.; Foré, S.; Johnson, R.L.; Park, Y. High levels of alpha-gal with large variation in the salivary glands of lone star ticks fed on human blood. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, J.M.; Carpenter, A.; Kersh, G.J.; Wachs, T.; Commins, S.P.; Salzer, J.S. Geographic distribution of suspected alpha-gal syndrome cases—United States, 2017–2022. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 815–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Springer, Y.P.; Jarnevich, C.S.; Barnett, D.T.; Monaghan, A.J.; Eisen, R.J. Modeling the present and future geographic distribution of the lone star tick, Amblyomma americanum, in the continental United States. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2015, 93, 875–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghavan, R.K.; Peterson, A.T.; Cobos, M.E.; Ganta, R.; Foley, D. Current and future distribution of the lone star tick, Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae), in North America. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0209082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, A.; Drexler, N.A.; McCormick, D.W.; Thompson, J.M.; Kersh, G.; Commins, S.P.; Salzer, J.S. Health Care Provider Knowledge Regarding Alpha-gal Syndrome—United States, March–May 2022. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 809–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alpha-Gal Alliance Action Fund, a Nonprofit Advocacy Partner of Alpha-Gal Alliance. Available online: https://www.alphagalaction.org (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Wilson, J.M.; Schuyler, A.J.; Workman, L.; Gupta, M.; James, H.R.; Posthumus, J.; McGowan, E.C.; Commins, S.P.; Platts-Mills, T.A.E. Investigation into the α-gal syndrome: Characteristics of 261 children and adults reporting red meat allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2019, 7, 2348–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busing, J.D.; Stone, C.A., Jr.; Nicholson, M.R. Clinical presentation of alpha-gal syndrome in pediatric gastroenterology and response to mammalian dietary elimination. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 118, 1293–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, A.M.; Cherry-Brown, D.; Biggerstaff, B.J.; Jones, E.S.; Amelio, C.L.; Beard, C.B.; Petersen, L.R.; Kersh, G.J.; Commins, S.P.; Armstrong, P.A. Clinical and laboratory features of patients diagnosed with alpha-gal syndrome-2010-2019. Allergy 2023, 78, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGill, S.K.; Commins, S.P.; Peery, A.F.; Galanko, J.; Keku, T.O.; Shaheen, N.J.; Anderson, C.; Sandler, R.S. Alpha-gal sensitization in a US screening population is not associated with a decreased meat intake or gastrointestinal symptoms. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 118, 1276–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, Y.; Chinuki, Y.; Ogino, R.; Yamasaki, K.; Aiba, S.; Ugajin, T.; Yokozeki, H.; Kitamura, K.; Morita, E. Cohort study of subclinical sensitization against galactose-α-1,3-galactose in Japan: Prevalence and regional variations. J. Dermatol. 2022, 49, 1268–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Straesser, M.D.; Keshavarz, B.; Workman, L.; McGowan, E.C.; Platts-Mills, T.A.E.; Wilson, J.M. IgE to galactose-α-1,3-galactose wanes over time in patients who avoid tick bites. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020, 8, 364–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commins, S.P. Diagnosis & management of alpha-gal syndrome: Lessons from 2,500 patients. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2020, 16, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Levin, M.; Apostolovic, D.; Biedermann, T.; Commins, S.P.; Iweala, O.I.; Platts-Mills, T.A.E.; Savi, E.; van Hage, M.; Wilson, J.M. Galactose alpha-1,3-galactose phenotypes: Lessons from various patient populations. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019, 122, 598–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabelane, T.; Basera, W.; Botha, M.; Thomas, H.F.; Ramjith, J.; Levin, M.E. Predictive values of alpha-gal IgE levels and alpha-gal IgE: Total IgE ratio and oral food challenge-proven meat allergy in a population with a high prevalence of reported red meat allergy. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2018, 29, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, K.; Zlotoff, B.J.; Borish, L.C.; Commins, S.P.; Platts-Mills, T.A.E.; Wilson, J.M. Alpha-Gal Syndrome vs Chronic Urticaria. JAMA Dermatol. 2019, 155, 115–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.; Bray, N.; Kaushik, P. Erythrodermic psoriasis and alpha-gal syndrome: A case report. J. Med. Clin. Res. Rev. 2025, 9, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik, P.; Suresh, S.; Alexander, C.S. Alpha-gal syndrome presenting as fibromyalgia in an American Indian population. J. Med. Clin. Res. Rev. 2024, 19, 329–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brestoff, J.R.; Zaydman, M.A.; Scott, M.G.; Gronowski, A.M. Diagnosis of red meat allergy with antigen-specific IgE tests in serum. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 140, 608–610.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehlich, J.; Fischer, J.; Hilger, C.; Swiontek, K.; Morisset, M.; Codreanu-Morel, F.; Schiener, M.; Blank, S.; Ollert, M.; Darsow, U.; et al. The basophil activation test differentiates between patients with alpha-gal syndrome and asymptomatic sensitization. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 143, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz-Rodrigues, R.; Mazuecos, L.; de la Fuente, J. Current and Future Strategies for the Diagnosis and Treatment of the Alpha-Gal Syndrome (AGS). J. Asthma Allergy 2022, 15, 957–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zychowski, D.L.; Alvarez, C.; Abernathy, H.; Giandomenico, D.; Choudhary, S.K.; Vorobiov, J.M.; Boyce, R.M.; Nelson, A.E.; Commins, S.P. Tick-Borne Disease Infections and Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain. JAMA Netw Open. 2024, 7, e2351418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bosques, C.J.; Collins, B.E.; Meador, J.W., 3rd; Sarvaiya, H.; Murphy, J.L.; Dellorusso, G.; Bulik, D.A.; Hsu, I.H.; Washburn, N.; Sipsey, S.F.; et al. Chinese hamster ovary cells can produce galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose antigens on proteins. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 1153–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Polanco, E.; Borowitz, S. Delayed Hypersensitivity Reaction to Infliximab Due to Mammalian Meat Allergy. JPGN Rep. 2023, 4, e322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chitnavis, M.; Stein, D.J.; Commins, S.; Schuyler, A.J.; Behm, B. First-dose anaphylaxis to infliximab: A case of mammalian meat allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2017, 5, 1425–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leder, J.; Diederich, A.; Patel, B.; Bowie, M.; Renwick, C.M.; Mangunta, V. Perioperative Considerations in Alpha-Gal Syndrome: A Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e53208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Commins, S.P. Invited Commentary: Alpha-Gal Allergy: Tip of the Iceberg to a Pivotal Immune Response. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2016, 16, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, J.; Hebsaker, J.; Caponetto, P.; Platts-Mills, T.A.E.; Biedermann, T. Galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose sensitization is a prerequisite for pork-kidney allergy and cofactor-related mammalian meat anaphylaxis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 134, 755–759.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commins, S.P.; James, H.R.; Stevens, W.; Pochan, S.L.; Land, M.H.; King, C.; Mozzicato, S.; Platts-Mills, T.A.E. Delayed clinical and ex vivo response to mammalian meat in patients with IgE to galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 134, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuravi, K.V.; Sorrells, L.T.; Nellis, J.R.; Rahman, F.; Walters, A.H.; Matheny, R.G.; Choudhary, S.K.; Ayares, D.L.; Commins, S.P.; Bianchi, J.R.; et al. Allergic response to medical products in patients with alpha-gal syndrome. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2022, 164, e411–e424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, R.B.; Wilson, J.M.; Mehaffey, J.H.; Platts-Mills, T.A.E.; Ailawadi, G. Safety of intravenous heparin for cardiac surgery in patients with alpha-gal syndrome. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2021, 111, 1991–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozzicato, S.M.; Tripathi, A.; Posthumus, J.B.; Platts-Mills, T.A.E.; Commins, S.P. Porcine or bovine valve replacement in 3 patients with IgE antibodies to the mammalian oligosaccharide galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2014, 2, 637–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullins, R.J.; James, H.; Platts-Mills, T.A.E.; Commins, S.P. Relationship between red meat allergy and sensitization to gelatin and galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 129, 1334–1342.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyttebroek, A.; Sabato, V.; Bridts, C.H.; De Clerck, L.S.; Ebo, D.G. Anaphylaxis to succinylated gelatin in a patient with a meat allergy: Galactose-alpha(1, 3)-galactose (alpha-gal) as antigenic determinant. J. Clin. Anesth. 2014, 26, 574–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, C.A., Jr.; Hemler, J.A.; Commins, S.P.; Schuyler, A.J.; Phillips, E.J.; Peebles, R.S., Jr.; Fahrenholz, J.M. Anaphylaxis after zoster vaccine: Implicating alpha-gal allergy as a possible mechanism. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 139, 1710–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, C.A., Jr.; Commins, S.P.; Choudhary, S.; Vethody, C.; Heavrin, J.L.; Wingerter, J.S.; Hemler, J.A.; Babe, K.; Phillips, E.J.; Norton, A.E. Anaphylaxis after vaccination in a pediatric patient: Further implicating alpha-gal allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2019, 7, 322–324.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, R.B.; Frischtak, H.L.; Kron, I.L.; Ghanta, R.K. Premature Bioprosthetic Aortic Valve Degeneration Associated with Allergy to Galactose-Alpha-1,3-Galactose. J. Card. Surg. 2016, 31, 446–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banner, W.; Edelen, K.; Epperson, L.C.; Moore, E. Hypersensitivity reactions due to North American pit viper antivenom administration and confirmed elevation of alpha-gal IgE. Toxicol. Commun. 2023, 8, 2314314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J.; Eberlein, B.; Hilger, C.; Eyer, F.; Eyerich, S.; Ollert, M.; Biedermann, T. Alpha-gal is a possible target of IgE-mediated reactivity to antivenom. Allergy 2017, 72, 764–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navalpakam, A.; Thanaputkaiporn, N.; Poowuttikul, P. Management of anaphylaxis. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2022, 42, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangale, T. Created in BioRender. 2025. Available online: https://BioRender.com/ (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Lammerts van Bueren, J.J.; Rispens, T.; Verploegen, S.; van der Palen-Merkus, T.; Stapel, S.; Workman, L.J.; James, H.; van Berkel, P.H.; van de Winkel, J.G.; Platts-Mills, T.A.; et al. Anti-galactose-α-1,3-galactose IgE from allergic patients does not bind α-galactosylated glycans on intact therapeutic antibody Fc domains. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 574–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platts-Mills, T.A.E.; Li, R.C.; Keshavarz, B.; Smith, A.R.; Wilson, J.M. Diagnosis and Management of Patients with the α-Gal Syndrome. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020, 8, 15–23.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).