Abstract

Background: Pruritus is burdensome across dermatoses. Beyond Staphylococcus, broader components of the cutaneous microbiome—bacteria, fungi, and viruses—and their products shape itch via barrier disruption, immune polarization, and direct neurosensory activation. Methods: We conducted a narrative review of human and translational studies. PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, and Web of Science were searched from inception to 27 August 2025 using terms for itch, skin microbiome, bacteriotherapy, proteases, PAR, TRP channels, IL-31, Malassezia, and AHR ligands. English and Italian records were screened; randomized trials, systematic reviews, and mechanistic studies were prioritized; and unsupported single case reports were excluded. Results: Beyond Staphylococcus aureus, microbial drivers include secreted proteases activating PAR-2/4; pore-forming peptides and toxins engaging MRGPRs and sensitizing TRPV1/TRPA1; and metabolites, especially tryptophan-derived AHR ligands, that recalibrate barrier and neuro-immune circuits. Commensal taxa can restore epidermal lipids, tight junctions, and antimicrobial peptides. Early studies of topical live biotherapeutics—Roseomonas mucosa and Staphylococcus hominis A9—report reductions in disease severity and itch. Fungal communities, particularly Malassezia, contribute via lipases and bioactive metabolites with context-dependent effects. Across studies, heterogeneous itch metrics, small samples, and short follow-up limit certainty. Conclusions: The cutaneous microbiome actively contributes to itch and is targetable. Future studies should prioritize standardized itch endpoints, responder stratification, and robust safety for live biotherapeutics.

1. Introduction

Pruritus is a pervasive and disabling symptom across dermatologic disease, impairing sleep, productivity, and quality of life. While the neural and immune circuitry of itch has been progressively elucidated—spanning epithelial barrier signals, type-2 inflammation, pruritogenic cytokines such as IL-31, and dedicated sensory pathways including TRPV1/TRPA1 and MRGPRs—the contribution of the cutaneous microbiome has only recently moved from association to mechanistic relevance [1,2,3,4]. In parallel with host factors, microbial communities and their products can initiate, amplify, or dampen pruriceptive signaling at the skin–nerve–immune interface [1].

Beyond the well-recognized role of Staphylococcus aureus in atopic dermatitis, a broader microbiome-centered view of itch is emerging. Bacterial proteases, pore-forming peptides, and toxins can directly engage protease-activated receptors (PAR-2/4), MRGPRs, and ion channels on sensory neurons and keratinocytes, lowering itch thresholds and reinforcing inflammation. Conversely, commensal species may restore epidermal lipids, tighten junctional integrity, induce antimicrobial peptides, and modulate cytokine networks, thereby indirectly reducing neuro-inflammation and pruritic drive [5,6]. Fungal communities—particularly Malassezia—and resident cutaneous viruses add metabolic and immunologic layers through lipase activity and bioactive metabolites (e.g., tryptophan-derived ligands of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor) that recalibrate epithelial and neuronal responses. This dynamic ecosystem suggests that loss of microbial diversity and function (dysbiosis) can bias the skin toward persistent itch [4,7].

Clinically, recognizing microbiome–itch crosstalk opens therapeutic avenues beyond conventional anti-inflammatories and neuromodulators. Topical live biotherapeutics, targeted modulation of microbial protease activity or PAR signaling, and strategies that bolster commensal functions represent rational approaches [2,8].

Despite rapid advances, key limitations persist: heterogeneous and inconsistently reported itch endpoints, small and short-duration trials, limited causal inference from cross-sectional designs, and incomplete mapping of microbial metabolites relevant to neuronal activation [9,10]. Safety, quality, and durability frameworks for live biotherapeutics require maturation, and responder stratification based on microbial and multi-omics signatures remains an unmet need [11,12]. Within this context, the present narrative review examines how the cutaneous microbiome contributes to itch pathobiology beyond Staphylococcus, synthesizes mechanistic pathways, appraises clinical evidence for microbiome-targeted and microbiome-relevant interventions, and outlines priorities for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

This narrative review was designed and reported in line with good-practice guidance for narrative syntheses (e.g., SANRA) and, where applicable, with elements of PRISMA-S for search reporting [4]. We queried PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, and Web of Science from database inception to 27 August 2025. Staphylococcus (especially S. aureus) and Malassezia were prespecified a priori because of (i) their high prevalence on human skin, (ii) consistent associations with itch-dominant dermatoses, and (iii) robust mechanistic signals (proteases, toxins/peptides, lipases, and tryptophan-derived metabolites) directly relevant to pruriceptor activation and barrier damage. We did not screen all articles on Staphylococcus or Malassezia indiscriminately: we combined organism terms with itch-specific terms (e.g., pruritus, itch NRS, PP-NRS, VAS), mechanistic terms (e.g., protease, PAR-2/4, TRPV1/TRPA1, MRGPR, IL-31), and dermatologic contexts. Records lacking an itch outcome or mechanistic link to pruritus were excluded at title/abstract stage. Searches were limited to English or Italian. Duplicates were removed and reference lists of key articles were hand-searched to identify additional records. Eligibility criteria prioritized human studies (randomized and nonrandomized trials, cohort and case–control studies), systematic reviews, and translational mechanistic research directly examining links between the skin microbiome (taxa, functions, or metabolites) and pruritus or validated itch outcomes; Animal-only studies were included only when: (i) the pathway is conserved in human skin or peripheral neurons, and (ii) there is at least one complementary human line of evidence (ex vivo human tissue, clinical biomarker correlation, or pharmacologic modulation in patients) supporting itch relevance. Otherwise, they were excluded or cited as hypothesis-generating only. We excluded non–peer-reviewed preprints from the evidence synthesis. When mentioned, they are flagged as exploratory context and not used to support core mechanistic or clinical conclusions. Two reviewers independently screened titles/abstracts and full texts, resolving disagreements by consensus. For each included study, we extracted design, population/condition, microbiome compartment and methods, candidate taxa or metabolite classes, intervention (if any), pruritus metrics (e.g., NRS, VAS, PP-NRS), sample size, follow-up, key results on itch, safety, and microbiome/barrier readouts. Risk of bias/quality was appraised with design-appropriate tools (e.g., RoB 2 for randomized trials, ROBINS-I or Newcastle–Ottawa for observational studies); preclinical studies were assessed qualitatively for rigor and translational plausibility. Given heterogeneity in designs and outcomes, no meta-analysis was planned; findings were synthesized narratively and organized by mechanistic pathway (proteases/PAR, MRGPR/TRP, metabolites/AHR), microbial groups (pathogenic vs. commensal), and clinical context (e.g., atopic dermatitis, scalp itch). Protease/PAR, MRGPR/TRP, and IL-31 terms were prespecified because these axes directly link microbial products to pruriceptor activation and itch behaviors, providing a mechanistic scaffold to organize the review. The primary outcome of interest was change in pruritus intensity or burden; secondary outcomes included quality of life, sleep disturbance, rescue medication use, microbiome or metabolite shifts, barrier function, and safety. No new, unpublished data were generated; ethics approval was not applicable; the search was last updated on 27 August 2025 and the protocol was not registered. Our goal is to translate complex microbe–neuron–immune interactions into clear, clinically relevant concepts for readers beyond the immediate field.

3. Biological Mechanisms of Pruritus Relevant to the Microbiome

Microbial dysbiosis primes the skin for itch through a cascade that begins at the barrier and culminates in central nervous system plasticity [13,14]. Altered community structure perturbs stratum corneum lipids, tight junctions, and antimicrobial peptides, increasing transepidermal water loss, shifting surface pH, and exposing free nerve endings; this barrier failure grants microbial products and ions easier access to keratinocytes, resident immune cells, and peripheral afferents, lowering activation thresholds and locking patients into the itch–scratch cycle that further abrades the barrier and expands microbial niches [5,15]. Within this permissive milieu, protease–PAR signaling is a dominant amplifier: bacterial and fungal proteases, alongside host proteases induced by dysbiosis and scratching, cleave protease-activated receptors on keratinocytes and unmyelinated C-fibers, driving calcium influx, release of pruritogenic mediators, and neurogenic vasodilation, while excess proteolysis degrades corneodesmosomes and filaggrin-derived components, compounding barrier dysfunction and perpetuating access of additional pruritogens [7,16,17,18]. In parallel, mast-cell and neuronal MRGPRs sense cationic peptides and selected microbial products, triggering rapid pruriceptor firing and IgE-independent mast-cell degranulation; this creates a self-reinforcing loop in which histamine-independent mediators and proteases reciprocally heighten excitability even when classic allergens are absent [19,20]. These inputs converge on polymodal TRP channels: TRPV1 and TRPA1 on primary afferents are sensitized by microbially driven cytokines, lipid mediators, and reactive metabolites via phosphorylation and remodeling of membrane microdomains, such that previously subthreshold cues—thermal fluctuation, sweat, minor friction—become overtly pruritic; sustained bombardment of these channels also facilitates central sensitization [21,22]. Dysbiosis biases epithelial and dendritic-cell signaling toward type-2 immunity, weakening barrier programs and enhancing neuronal excitability through IL-4/IL-13, while IL-31 directly stimulates neurons expressing IL-31RA/OSMR and further augments TRP activity; microbial cues therefore knit into cytokine networks to potentiate pruriception, and the resulting neurogenic inflammation reshapes the habitat to favor taxa that thrive in inflamed, protease-rich microenvironments [23,24]. Metabolic crosstalk adds a tunable layer: tryptophan catabolites and other microbially derived ligands calibrate aryl hydrocarbon receptor pathways in keratinocytes and immune cells, where context, dose, and ligand specificity determine whether AHR reinforces epidermal differentiation and dampens itch or instead promotes inflammatory gene programs and neuronal hyperexcitability [25,26]. Microbiome-shaped lipid signals can reach the skin via the circulation, sweat, and sebum. On the surface, bile acids and lysophospholipids are detectable and may modulate keratinocytes and sensory fibers [27]. Direct GPCR engagement in human cutaneous neurons is not uniformly demonstrated; evidence is mixed and partly preclinical. We therefore frame these interactions as hypothesis-generating and specify them wherever citations exist. These lipid cues likely intersect with PAR, MRGPR, and TRP pathways to tune itch thresholds. Activated afferents release neuropeptides such as substance P and CGRP, which drive vasodilation, mast-cell activation, and cytokine cascades; microbial products can initiate or potentiate these neuropeptidergic responses, while neurogenic inflammation feeds back to alter nutrient availability, oxygen tension, and pH at the surface, selecting for biofilm-forming or protease-secreting taxa that further stoke itch. Innate pattern-recognition receptors (TLRs, CLRs, NLRs) on keratinocytes and immune cells detect microbial motifs and elicit alarmins, including IL-33 and TSLP, indirectly sensitizing pruriceptors and reinforcing type-2 skewing; ATP, endothelin-1, and other epithelial danger signals join this relay, bridging microbial detection to itch behavior [28,29,30,31]. Over time, persistently heightened peripheral input entrains spinal changes—enhanced dorsal horn excitability, reduced inhibitory gating, glial activation, and altered descending modulation—that consolidate chronic itch even as peripheral microbial loads fluctuate, explaining clinical observations of lingering hypersensitivity after apparent cutaneous improvement. Viewed as a network, pruritus emerges from an interacting triad of barrier/epithelium, immune system, and sensory neurons modulated by microbial proteases, peptides, and metabolites; this systems frame yields testable implications: reducing protease burden should blunt PAR-dependent firing and itch, restoring commensal lipid programs should raise neuronal thresholds by repairing the barrier and normalizing surface pH, tailoring AHR ligand profiles should rebalance differentiation and inflammatory tone to normalize pruriception, and combinational strategies that align barrier repair, cytokine blockade, anti-biofilm tactics, and targeted microbiome modulation should produce additive—and potentially synergistic—antipruritic effects with improved durability [5,6,32,33].

4. Cutaneous Microbiome and Itch

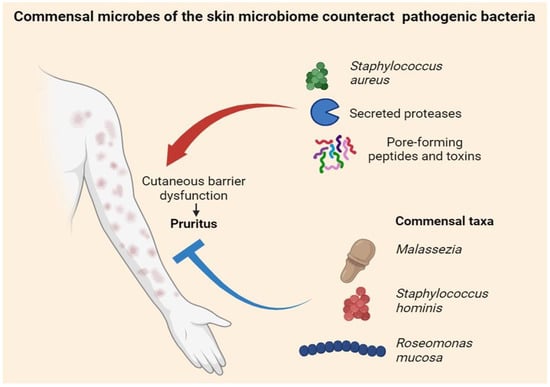

In atopic dermatitis, expansion of Staphylococcus aureus often accompanies flares and heightened itch via proteases, cytolytic peptides, and toxins that erode barrier integrity and lower neuronal thresholds, yet itch severity can vary despite similar staphylococcal loads, underscoring broader ecosystem effects in which health-associated commensals—Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus hominis, Roseomonas mucosa, Cutibacterium and select Corynebacterium spp.—support lipid synthesis, tight junctions, and antimicrobial peptide induction while restraining S. aureus through bacteriocins, quorum interference, and niche competition and dampening type-2 skewing to indirectly attenuate pruritus [4] (Figure 1). Mixed-species biofilms on lesional and peri-lesional skin further protect microbes from host defenses and topicals, prolong exposure to proteases and pruritogens, and impede barrier repair, thereby sustaining the itch–scratch cycle [34,35]. Beyond bacteria, Malassezia species dominate sebaceous sites and supply lipases and tryptophan metabolites that modulate aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling with context-dependent outcomes—either reinforcing barrier programs or promoting inflammation and neuronal sensitization that shape scalp and facial itch phenotypes—while the cutaneous virome, particularly resident bacteriophages, tunes bacterial population dynamics (including S. aureus control) and may shift during flares to alter bacterial virulence and metabolite output with downstream effects on pruriceptor activation [36]. These interactions are highly niche-specific—humid flexures and sebum-rich scalp favor taxa and metabolites distinct from dry extensor skin—and evolve with age, as pediatric communities transition through adolescence and adulthood, modifying susceptibility to pruritic flares; outside of atopy, prurigo nodularis features scratch-driven neuroinflammation that creates dysbiotic niches perpetuating itch via barrier disruption and secondary colonization [14,37], whereas psoriasis-associated itch appears linked less to a single pathogen and more to community structure and metabolite profiles interacting with neuro-immune circuits; host determinants—including filaggrin loss-of-function, type-2 cytokine tone [2], sweating, pH, and sebum quality—can tip ecosystems toward protease-rich, pruritogenic states or toward commensal-dominant, barrier-supportive configurations, and therapeutic pressures (topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, antiseptics, antibiotics) rapidly remodel these communities so that short-term itch relief from pathogen reduction may be offset by nonselective suppression of protective taxa, predisposing to rebound dysbiosis and recurrent pruritus upon withdrawal [38,39]; accordingly, early-phase data for topical live biotherapeutics such as R. mucosa and S. hominis A9 suggest reductions in disease activity and itch alongside restoration of commensal functions [7,37], complemented by targeted strategies—protease inhibition, PAR pathway modulation, pH optimization, lipid replenishment, and prebiotic vehicles that preferentially nurture beneficial taxa—yet translation is hampered by measurement challenges, since culture-independent profiling (16S versus shotgun metagenomics), limited strain-level resolution, and variable functional readouts (metabolomics, protease assays) can yield divergent pictures of “dysbiosis” [40], while sampling depth, site selection, and timing relative to flares can obscure links to itch, emphasizing the need for standardized, longitudinal, multi-omics approaches anchored to validated itch metrics to convert mechanistic signals into clinical practice.

Figure 1.

Cutaneous microbiome in pruritus. Staphylococcus aureus—via secreted proteases and pore-forming toxins/peptides—disrupts the skin barrier and fuels the itch–scratch cycle, whereas commensals such as Malassezia spp., Staphylococcus hominis, and Roseomonas mucosa antagonize pathogens, support barrier repair, and dampen pruritus.

5. Gut Microbiome and Itch (The “Gut–Skin–Liver–Kidney Axis”)

The gut microbiome shapes pruritus through metabolites, immune education, and lipid signaling that propagate along the gut–liver–kidney–skin network, with microbial products reaching the skin via the circulation, sweat, and sebum, while chronic itch and inflammation feed back on behavior, sleep, diet, and neuroendocrine tone to remodel gut ecology. In cholestasis, systemic accumulation and altered composition of bile acids, coupled with increased autotaxin activity and lysophosphatidic acid generation, heighten pruriceptive drive [41]; by deconjugating and transforming bile acids and modulating enterohepatic circulation, gut microbes influence the pruritogenic potential of specific species and ultimately the excitability of cutaneous sensory neurons. In advanced kidney disease, dysbiosis and slowed transit favor proteolytic fermentation that yields protein-bound uremic solutes—indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate—from aromatic amino acids; these toxins promote systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, and peripheral nerve sensitization, while increased intestinal permeability and low-grade endotoxemia amplify pruriceptive signaling [41]. Tryptophan metabolism provides a parallel neurosensory lever: bacterial conversion to indoles and other ligands tunes aryl hydrocarbon receptor activity, epithelial differentiation, and cytokine tone, whereas tryptamine and kynurenine pathways influence serotonergic and glutamatergic circuits that set itch thresholds—beneficial when indole profiles are balanced, potentially pro-pruritic when fluxes are dysregulated [42]. Short-chain fatty acids (acetate, propionate, butyrate) further regulate Treg differentiation, keratinocyte function, and neuroimmune crosstalk, with adequate SCFA signaling tightening epithelial barriers and lowering inflammatory set points, and loss of saccharolytic metabolism tilting toward a pro-pruritic milieu [43]. When intestinal junctions fail, microbial motifs engage TLRs and NLRs to induce systemic alarmins such as IL-33 and TSLP, which converge on cutaneous immune cells and sensory neurons to lower itch thresholds even without overt dermatoses [4]. These mechanisms create actionable levers: diets richer in fiber and resistant starch and lighter in ultra-processed protein loads can rebalance saccharolytic versus proteolytic fermentation, shift bile-acid pools, and reduce toxin generation; pharmacologic approaches that alter bile-acid handling or lower intestinal toxin burden, alongside narrow-spectrum, non-absorbed antimicrobials and targeted oral live biotherapeutics, aim to recalibrate microbial function while preserving ecological resilience [44]. At the skin interface, microbiome-modified bile acids and lysophospholipids circulate to the surface and interact with GPCRs and ion channels on keratinocytes and sensory fibers, integrating with PAR, MRGPR, and TRP pathways; sebum composition—shaped in part by diet and gut–liver lipid flux—conditions niches that either favor or restrain pruritogenic taxa [45]. To translate these insights into precision care, studies should adopt biomarkers such as serum/skin bile-acid speciation, autotaxin activity, indoxyl and p-cresyl conjugates, fecal SCFA profiles, permeability assays, and multi-omics signatures linking taxa to metabolite flux, and employ longitudinal designs that synchronize gut and skin sampling with validated itch metrics, sleep disturbance, and quality-of-life outcomes to establish causality and guide targeted interventions [35].

6. Therapeutic Implications of Microbiome Targeting

Translating the microbiome–itch paradigm into care begins with rational topical live biotherapeutics, with commensal strains (e.g., Staphylococcus spp., Roseomonas spp.) selected to suppress pruritogenic pathobionts, restore lipid programs, and temper type-2/IL-31 tone while addressing practical issues of colonization versus transient engraftment, induction/maintenance dosing, vehicle effects on viability, and stability on real-world skin, with trials prioritizing itch as a primary outcome (daily NRS/PP-NRS), as well as sleep disturbance, rescue-medication use, and off-treatment durability [46]. In parallel, protease and PAR pathway modulation—via topical protease inhibitors, mildly acidic pH to curb serine proteases, and barrier formulations that shield or neutralize proteolysis—can be paired with LBPs or anti-inflammatories to interrupt the itch–scratch–protease loop, while microbiome-supportive barrier care (prebiotic emollients, ceramide-cholesterol–fatty-acid replenishment, pH-appropriate cleansers) tips communities toward commensal dominance and reduces pruriceptor exposure; when antisepsis or antibiotics are required, use them precisely and briefly and follow with restorative care to minimize rebound dysbiosis [47]. Because biofilms prolong exposure to proteases and toxins and impede penetration of actives, a practical sequence is biofilm disruption (e.g., keratolytics, surfactants, selective physical debulking where appropriate), targeted therapy (LBP/protease-aware topicals), barrier rebuild [48]. Systemic levers along the gut–skin–liver–kidney axis complement topical strategies: diets richer in fiber and resistant starch and lower in ultra-processed protein loads foster SCFA production, tighten epithelial barriers, and may raise itch thresholds; in selected phenotypes, agents that reshape bile-acid handling or reduce intestinal generation/absorption of uremic toxins, as well as targeted oral biotherapeutics or non-absorbed narrow-spectrum antimicrobials, merit evaluation with itch-centric endpoints [49]. Non-microbiome biologics—IL-31RA or IL-4Rα blockade and, where appropriate, JAK inhibition [1]—rapidly reduce itch, improve barrier function, and may indirectly normalize cutaneous niches; layering these with LBPs, protease control, and anti-biofilm tactics is biologically plausible for additive relief [50]. A precision framework should integrate phenotype and site (e.g., scalp, flexures), bedside barrier metrics, and multi-omics—strain-level skin metagenomics, protease-burden assays, metabolomics (indoles), bile-acid speciation and autotaxin activity, and indoxyl/p-cresyl conjugates—to identify “microbiome-responsive” pruritus and guide targeted combinations Pragmatic RCTs need validated daily itch scales as primary endpoints, sleep and quality-of-life co-primaries, standardized background care and flare plans, ≥24–52-week duration for durability, and objective mechanistic readouts (skin/gut microbiome, protease activity, lipidomics, bile-acid panels); factorial designs can test synergy (e.g., LBP ± protease control; IL-31 blockade ± LBP). Safety and quality are central: LBPs require GMP manufacture, stable identity and potency, absence of transferable resistance/virulence genes, batch-to-batch viability, and environmental/shedding assessments, with monitoring for local irritation, infection in compromised hosts, and long-term ecological effects; systemic modulators warrant hepatobiliary and renal monitoring alongside itch outcomes. For clinicians, an implementation pathway starts with optimized barrier care and targeted antisepsis, adds microbiome-supportive measures (prebiotic emollients, pH-appropriate hygiene), considers LBPs or protease-focused regimens when dysbiosis features persist, escalates to biologics (IL-31/IL-4Rα or JAK) when neuro-immune drive predominates, and uses itch diaries, sleep metrics, and simple proxies of microbial or protease load to individualize therapy over time.

7. Discussion

Converging evidence indicates that the cutaneous microbiome is functionally implicated in the generation and maintenance of pruritus. Microbial proteases, pore-forming peptides, toxins, and context-dependent metabolites interact with epithelial, immune, and neuronal compartments to lower pruriceptive thresholds and sustain the itch–scratch cycle. While Staphylococcus aureus remains a prominent actor in atopic dermatitis, broader ecosystem features—loss of commensal functions, biofilm formation, and contributions from fungal and viral communities—better account for the heterogeneity of itch phenotypes across diseases, anatomical sites, and ages. The most persuasive translational thread links excessive protease activity to PAR signaling and sensory neuron sensitization, alongside dysbiosis-driven type-2 inflammation converging on IL-31–dependent pathways. Early clinical signals for topical live biotherapeutics and microbiome-supportive barrier care suggest that restoring commensal function can reduce itch, particularly in atopic and scalp-dominant phenotypes, and these strategies are biologically complementary to established antipruritic biologics that modulate IL-31 or IL-4/13 and may indirectly normalize microbial niches.

Despite this promise, the literature has notable constraints. Itch outcomes are heterogeneous and inconsistently reported; many studies are small, of short duration, and conducted against variable background therapies. Microbiome assessments often lack strain-level and functional resolution and rarely integrate measures such as protease burden, lipidomics, or metabolite flux. Sampling bias related to site selection and timing versus flares, batch effects, and unmeasured confounders (e.g., hygiene practices, detergents, climate) complicate causal inference. Safety and durability also warrant attention: live biotherapeutics require stringent identity, potency, and genomic safety controls, with real-world stability, colonization dynamics, and ecological effects (including resistance gene transfer) systematically monitored. For systemic strategies acting along the gut–liver–kidney axis—such as those that reshape bile-acid pools or reduce intestinal generation/absorption of uremic toxins—hepatic and renal safety parameters should be tracked alongside itch outcomes.

These limitations define clear opportunities. A practical precision framework should combine clinical phenotype, anatomical site, barrier status, and accessible biomarkers (e.g., skin pH, transepidermal water loss, local protease activity) with multi-omics where feasible (strain-level metagenomics, metabolomics including indoles and bile acids, autotaxin activity). Such signatures can identify “microbiome-responsive” pruritus and guide targeted combinations—e.g., protease control plus a live biotherapeutic, or IL-31 blockade layered onto commensal restoration. Future trials should elevate itch to a primary endpoint using validated daily measures (Itch NRS or PP-NRS), include sleep and quality-of-life as co-primaries, and extend to at least 24–52 weeks to assess durability and rebound. Factorial or adaptive designs are well suited to test synergy among live biotherapeutics, protease/PAR modulation, and biologics, while mechanistic substudies should pair longitudinal skin and gut sampling with functional assays (protease burden, biofilm metrics, lipid and metabolite panels).

Viewed through this lens, pruritus management shifts from purely anti-inflammatory tactics to ecosystem-aware care. By standardizing itch outcomes, building robust safety frameworks for live products, and adopting biomarker-guided stratification, microbiome-targeted therapies can be rationally integrated with established antipruritic agents to deliver more durable, patient-centered control of itch.

8. Conclusions

The cutaneous microbiome is not a passive passenger but an active determinant of itch pathobiology. Beyond the classical focus on Staphylococcus aureus, diverse bacterial, fungal, and viral communities and their products—proteases, pore-forming peptides, lipases, and context-dependent metabolites—converge on epithelial, immune, and neuronal nodes to lower itch thresholds. These inputs interface with host programs such as type-2 inflammation and IL-31 signaling and sensitize pruriceptors via PARs, MRGPRs, and TRP channels, thereby sustaining the itch–scratch cycle. Collectively, the evidence supports an ecosystem view of pruritus in which loss of commensal function, biofilm ecology, and metabolite mis-signaling amplify symptom burden across anatomically and clinically distinct phenotypes.

Clinically, this perspective reframes management from a purely anti-inflammatory paradigm to an “ecosystem-aware” strategy that aligns barrier optimization, targeted microbial modulation, and neuromodulation. Topical live biotherapeutics, protease burden control, anti-biofilm tactics, and microbiome-supportive skincare (pH, lipids, prebiotic vehicles) can be layered with established agents that block IL-31 or IL-4/13, which in turn may indirectly normalize microbial niches. Along the gut–skin–liver–kidney axis, dietary fiber, bile-acid handling, and reduction in microbially derived uremic toxins represent systemic levers that can attenuate pruriceptive drive reaching the skin. A practical, stepwise algorithm that escalates from barrier and microbiome support to targeted LBPs and finally to biologics or JAK inhibition—while maintaining ecological resilience—offers a rational path to durable itch control.

Translational progress will depend on methodological rigor. Future studies should elevate itch to a primary endpoint (daily Itch NRS or PP-NRS), incorporate sleep and quality-of-life co-primaries, and extend over 24–52 weeks to capture durability and rebound. Mechanistic substudies ought to integrate strain-level metagenomics, functional protease assays, lipidomics, and metabolite panels (e.g., indoles, bile acids, lysophospholipids) with simple bedside proxies (skin pH, transepidermal water loss). Precision stratification—by phenotype, site (sebaceous vs. dry), barrier status, and multi-omics signatures—can identify “microbiome-responsive” pruritus and guide combination therapy selection and sequencing.

Safety, quality, and implementation frameworks are equally pivotal. Live biotherapeutics require GMP manufacturing, stable identity and potency, genomic safety (absence of transferable resistance/virulence), viability in real-world conditions, and post-marketing ecological surveillance. For systemic modulators acting on bile acids or intestinal toxins, hepatic and renal monitoring should accompany itch outcomes. Health-system adoption will be aided by standardized care pathways, patient education on skincare/hygiene that preserves commensals, and pragmatic outcome tracking using itch diaries, sleep metrics, and, where available, wearable scratch sensing.

Finally, the field should broaden its lens to include cost-effectiveness, accessibility, pediatric and geriatric considerations, and equity across diverse skin types and environments. Advances in digital phenotyping, remote monitoring, and at-home sampling can reduce burden and capture real-world variability, while emerging modalities—strain-engineered LBPs, phage-based ecological control, and selective PAR/MRGPR modulators—promise more precise interventions. In sum, positioning the microbiome as a modifiable hub within the barrier–immune–neuron triad enables a coherent, precise roadmap: restore commensal function, reduce pruritogenic pressure, and align microbial and host targets to achieve sustained, patient-centered relief from itch.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.R. and V.P.; methodology, U.S.; validation, V.C., L.M. and F.G.; formal analysis, A.P. and E.B.; investigation, F.R.; data curation, V.P.; writing—original draft preparation, F.R. and V.P.; writing—review and editing, F.R. and V.P.; visualization, V.P.; supervision, S.R. and P.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study were obtained from public domain resources such as PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the authors used ChatGPT-5 for the purposes of study design, language and grammar analysis. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Butler, D.C.; Berger, T.; Elmariah, S.; Kim, B.; Chisolm, S.; Kwatra, S.G.; Mollanazar, N.; Yosipovitch, G. Chronic Pruritus: A Review. JAMA 2024, 331, 2114–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinhoff, M.; Ahmad, F.; Pandey, A.; Datsi, A.; AlHammadi, A.; Al-Khawaga, S.; Al-Malki, A.; Meng, J.; Alam, M.; Buddenkotte, J. Neuroimmune communication regulating pruritus in atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 149, 1875–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biazus Soares, G.; Hashimoto, T.; Yosipovitch, G. Atopic Dermatitis Itch: Scratching for an Explanation. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2024, 144, 978–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, S.K.; Khuwaja, W.M.; Hossain, M.L.; Fernando, L.G.B.; Dong, X. Neuroimmune interactions between itch neurons and skin microbes. Semin. Immunol. 2025, 78, 101933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Costa, F.; Blake, K.J.; Choi, S.; Chandrabalan, A.; Yousuf, M.S.; Shiers, S.; Dubreuil, D.; Vega-Mendoza, D.; Rolland, C.; et al. S. aureus drives itch and scratch-induced skin damage through a V8 protease-PAR1 axis. Cell 2023, 186, 5375–5393.e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, R.L.; Horswill, A.R. Staphylococcus aureus: The Bug Behind the Itch in Atopic Dermatitis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2024, 144, 950–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misery, L.; Pierre, O.; Le Gall-Ianotto, C.; Lebonvallet, N.; Chernyshov, P.V.; Le Garrec, R.; Talagas, M. Basic mechanisms of itch. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2023, 152, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labib, A.; Ju, T.; Yosipovitch, G. Emerging treatments for itch in atopic dermatitis: A review. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2023, 89, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Voigt, A.Y. The human skin microbiome: From metagenomes to therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 23, 771–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunjani, N.; Hlela, C.; O’Mahony, L. Microbiome and skin biology. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 19, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rethlefsen, M.L.; Kirtley, S.; Waffenschmidt, S.; Ayala, A.P.; Moher, D.; Page, M.J.; Koffel, J.B.; PRISMA-S Group. PRISMA-S: An extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ständer, S. Atopic Dermatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1136–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kengmo Tchoupa, A.; Kretschmer, D.; Schittek, B.; Peschel, A. The epidermal lipid barrier in microbiome–skin interaction. Trends Microbiol. 2023, 31, 723–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hülpüsch, C.; Rohayem, R.; Reiger, M.; Traidl-Hoffmann, C. Exploring the skin microbiome in atopic dermatitis pathogenesis and disease modification. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2024, 154, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhl, T.; Ikoma, A.; Kempkes, C.; Cevikbas, F.; Sulk, M.; Buddenkotte, J.; Akiyama, T.; Crumrine, D.; Camerer, E.; Carstens, E.; et al. Protease-Activated Receptor-2 Regulates Neuro-Epidermal Communication in Atopic Dermatitis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akiyama, T.; Lerner, E.A.; Carstens, E. Protease-activated receptors and itch. In Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; Volume 226, pp. 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meixiong, J.; Anderson, M.; Limjunyawong, N.; Sabbagh, M.F.; Hu, E.; Mack, M.R.; Oetjen, L.K.; Wang, F.; Kim, B.S.; Dong, X. Activation of Mast-Cell-Expressed Mas-Related G-Protein-Coupled Receptors Drives Non-histaminergic Itch. Immunity 2019, 50, 1163–1171.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhoff, M.; Buddenkotte, J.; Lerner, E.A. Role of mast cells and basophils in pruritus. Immunol. Rev. 2018, 282, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbière, A.; Loste, A.; Gaudenzio, N. MRGPRX2 sensing of cationic compounds—A bridge between nociception and skin diseases? Exp. Dermatol. 2021, 30, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, N.; Basso, L.; Sibilano, R.; Petitfils, C.; Meixiong, J.; Bonnart, C.; Reber, L.L.; Marichal, T.; Starkl, P.; Cenac, N.; et al. House dust mites activate nociceptor–mast cell clusters to drive type 2 skin inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 2019, 20, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, M.K.; Han, Y.; Liu, Z.; Hara, Y.; Langohr, I.M.; Morel, C.; Maloney, C.L.; Piepenhagen, P.; Xing, H.; Bodea, C.A.; et al. Type 2 cytokines pleiotropically modulate sensory nerve architecture and neuroimmune interactions to mediate itch. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2025, 156, 1066–1081.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, M.R.; Miron, Y.; Chen, F.; Miller, P.E.; Zhang, A.; Korotzer, A.; Richman, D.; Bryce, P.J. Type 2 cytokines sensitize human sensory neurons to itch-associated stimuli. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2023, 16, 1258823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegmann, H.; Renkhold, L.; Zeidler, C.; Agelopoulos, K.; Ständer, S. Interleukin Profiling in Atopic Dermatitis and Chronic Nodular Prurigo. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevikbas, F.; Wang, X.; Akiyama, T.; Kempkes, C.; Savinko, T.; Antal, A.; Kukova, G.; Buhl, T.; Ikoma, A.; Buddenkotte, J.; et al. A sensory neuron-expressed IL-31 receptor mediates T helper cell-dependent itch: Involvement of TRPV1 and TRPA1. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 133, 448–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaeian, A.; Rajabi, F.; Rezaei, N. Toll-like receptors in atopic dermatitis: Pathogenesis and therapeutic implications. Heliyon 2025, 11, e42226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Feng, Y.; Hu, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, T.; Zhang, J.; Yang, X.; Fu, Q.; Fu, D.; et al. Keratinocyte TLR2 and TLR7 contribute to chronic itch through pruritic cytokines and chemokines in mice. J. Cell. Physiol. 2023, 238, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamagawa-Mineoka, R. Toll-like receptors: Their roles in pathomechanisms of atopic dermatitis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1239244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, I.H.; Yoshida, T.; De Benedetto, A.; Beck, L.A. The cutaneous innate immune response in patients with atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 131, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsagareli, M.G.; Follansbee, T.; Iodi Carstens, M.; Carstens, E. Targeting Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) Channels, Mas-Related G-Protein-Coupled Receptors (Mrgprs), and Protease-Activated Receptors (PARs) to Relieve Itch. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, M.P.; Ständer, S. Chronic Pruritus: Current and Emerging Treatment Options. Drugs 2017, 77, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollanazar, N.K.; Smith, P.K.; Yosipovitch, G. Mediators of Chronic Pruritus in Atopic Dermatitis: Getting the Itch Out? Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2016, 51, 263–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uberoi, A.; Murga-Garrido, S.M.; Bhanap, P.; Campbell, A.E.; Knight, S.A.; Wei, M.; Chan, A.; Senay, T.; Tegegne, S.; White, E.K.; et al. Commensal-derived tryptophan metabolites fortify the skin barrier: Insights from a 50-species gnotobiotic model of human skin microbiome. Cell. Chem. Biol. 2025, 32, 111–125.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celoria, V.; Rosset, F.; Pala, V.; Dapavo, P.; Ribero, S.; Quaglino, P.; Mastorino, L. The Skin Microbiome and Its Role in Psoriasis: A Review. Psoriasis Targets Ther. 2023, 13, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cau, L.; Williams, M.R.; Butcher, A.M.; Nakatsuji, T.; Kavanaugh, J.S.; Cheng, J.Y.; Shafiq, F.; Higbee, K.; Hata, T.R.; Horswill, A.R.; et al. Staphylococcus epidermidis protease EcpA can be a deleterious component of the skin microbiome in atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 147, 955–966.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moniaga, C.S.; Tominaga, M.; Takamori, K. An Altered Skin and Gut Microbiota Are Involved in the Modulation of Itch in Atopic Dermatitis. Cells 2022, 11, 3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoghegan, J.A.; Irvine, A.D.; Foster, T.J. Staphylococcus aureus and Atopic Dermatitis: A Complex and Evolving Relationship. Trends Microbiol. 2018, 26, 484–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangel, S.M.; Paller, A.S. Bacterial colonization, overgrowth, and superinfection in atopic dermatitis. Clin. Dermatol. 2018, 36, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Yosipovitch, G. The Role of the Microbiome and Microbiome-Derived Metabolites in Atopic Dermatitis and Non-Histaminergic Itch. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2020, 21 (Suppl. S1), 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-C.; Shim, W.-S.; Kwak, I.-S.; Lee, D.-H.; Park, J.-S.; Lee, S.-Y.; Kang, S.-Y.; Chung, B.-Y.; Park, C.-W.; Kim, H.-O. Pathogenesis and Treatment of Pruritus Associated with Chronic Kidney Disease and Cholestasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Does, A.; Levy, C.; Yosipovitch, G. Cholestatic Itch: Our Current Understanding of Pathophysiology and Treatments. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2022, 23, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuers, U.; Wolters, F.; Oude Elferink, R.P.J. Mechanisms of pruritus in cholestasis: Understanding and treating the itch. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 20, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, T.; Sasaki-Tanaka, R.; Kimura, N.; Abe, H.; Yoshida, T.; Hayashi, K.; Sakamaki, A.; Yokoo, T.; Kamimura, H.; Tsuchiya, A.; et al. Pruritus in Chronic Cholestatic Liver Diseases, Especially in Primary Biliary Cholangitis: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kremer, A.E.; Bolier, R.; Van Dijk, R.; Oude Elferink, R.P.J.; Beuers, U. Advances in pathogenesis and management of pruritus in cholestasis. Dig. Dis. 2014, 32, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rušanac, A.; Škibola, Z.; Matijašić, M.; Čipčić Paljetak, H.; Perić, M. Microbiome-Based Products: Therapeutic Potential for Inflammatory Skin Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Fang, Y.; Hu, J.; Li, S.; Zeng, L.; Chen, S.; Li, Z.; Meng, R.; Yang, X.; Zhang, F.; et al. Innovative microbial strategies in atopic dermatitis. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1605434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidler, C.; Raap, U.; Witte, F.; Ständer, S. Clinical aspects and management of chronic itch. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2023, 152, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastorino, L.; Ribero, S.; Burlando, M.; Mendes-Bastos, P. Editorial: Patients-oriented treatments for chronic inflammatory skin diseases. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1473753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutaria, N.; Adawi, W.; Goldberg, R.; Roh, Y.S.; Choi, J.; Kwatra, S.G. Itch: Pathogenesis and treatment. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2022, 86, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misery, L.; Brenaut, E.; Pierre, O.; Le Garrec, R.; Gouin, O.; Lebonvallet, N.; Abasq-Thomas, C.; Talagas, M.; Le Gall-Ianotto, C.; Besner-Morin, C.; et al. Chronic itch: Emerging treatments following new research concepts. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 178, 4775–4791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, S.; Heul AVer Kim, B.S. New and emerging treatments for inflammatory itch. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021, 126, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).