Abstract

This study developed a model of non-economic exploitation using Marxian theory and Bourdieusian methods. A survey of 275 respondents from Hindu, Sikh, and Christian minorities in Pakistan assessed religious, cultural, and social exploitation. Using CB-SEM, findings revealed unequal distribution of structural resources, with minorities having fewer than the majority. Religious, cultural, and social exploitation were significantly related (p < 0.05), with religious exploitation being the strongest predictor of the others. The study concludes that minority–majority (MM) relations are exploitative in non-economic terms, prompting minority resistance. Future research should evaluate the impact of exploitation and the extent of minority responses.

1. Introduction

The Marxian theory of exploitation argues that exploitation evokes “the exploited” to react against “the exploiter,” mostly through protests (Chan 2016; Bush and Martiniello 2017; Mueller 2018; Greene 2018). This exploitation theory is based on class relations. However, we focused on majority and minority (MM) relations and distanced our theorization from class relations and the economic dimension of exploitation. Therefore, we introduced the non-economic dimension of exploitation by using Bourdieu’s (1984, 1996) method of theorization which did not believe in theory and data separatism. In other words, instead of abstraction, we relied upon a doctrine: theory driven by data. We focused on the religious majority and minority to theorize and evaluate non-economic dimension of exploitation in Pakistan.

The study’s empirical focus on Southern Punjab is critically informed by the region’s unique socio-religious history, where national-level policies have manifested with distinct intensity to institutionalize the non-economic exploitation of minorities. Historically a heartland of religious diversity with substantial Hindu and Sikh populations, the region’s demographic landscape was permanently reshaped by the 1947 Partition. The subsequent national project of Islamic majoritarianism, initiated by the First Amendment 1974 and intensified during the 1980s Islamization, found a fertile ground in Southern Punjab’s feudal and tribal social structure. Here, these national policies were leveraged by local power elites to consolidate control, leading to a severe manifestation of minority exclusion (Tahir 2021). This local dynamic manifests in a pervasive system of exploitation: minorities in Southern Punjab face extreme political marginalization, where the national reserved-seat system fails to counterbalance the dominance of local religiously-aligned political families (Zainab et al. 2021). They are subjected to intense social boycotts and economic blockades, particularly in districts like Rahim Yar Khan and Bahawalpur, restricting their access to land, employment, and markets (Human Rights Commission of Pakistan 2019).

Furthermore, the region has a disproportionately high incidence of blasphemy accusations, used as a tool for property seizure and social coercion, creating a climate of fear specific to its towns and villages (Amnesty International 2016, 2023; Human Rights Commission of Pakistan 2019). Thus, Southern Punjab represents a critical case where national policies have converged with local socio-economics to create a uniquely intense and institutionalized system of multidimensional minority exploitation. The findings on non-eco-nomic exploitation of religious minorities in Pakistan are critical in the context of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), directly addressing the mandate of SDG 10 (Target 10.2: to promote the inclusion of all, irrespective of religion, and Target 10.3: to eliminate discriminatory policies).

The paper is divided into two parts. The first part explains the constitutional rights of minorities, constitutional bias, and the condition of minorities in the country. This section revealed the exploitation reported in previous studies and the continuum of MM relations. The second part comprised the assessment of the exploitation tool and the hypothesized relationship between exploitation and reaction. Geometric modelling assessed the preliminary proposition of unequal distribution of resources in MM relations, and the structural equation modelling evaluated the association between non-economic exploitation and the likelihood of the minority’s reaction against the exploitation.

2. Minority, Constitution and Exploitation

Several international organizations of human and minority rights have proposed various definitions of a minority, but previous studies and official authorities did not ratify a unanimous conceptualization of a minority. Medda-Windischer (2017) defined minorities as “communities whose members have a distinct language, culture, or religion as compared to the rest of the population… (p. 26).” This definition may confuse ethnic and religious minorities because the former and the latter are distinctive characteristics “which set them apart from the majority population” (Fleischmann and Phalet 2016, p. 447). They are distinctive (Basedau et al. 2017) because a homogeneous characteristic of a group and their numerical proportion within a territory defines their minority status. We defined a minority on a religious dimension and related it with structural resources. A religious minority refers to a religious homogenous group that lacks structural resources compared with a majority. The majority assumes the higher numeric population in the definition. The percentage distribution of minorities and majorities by country is given in Appendix A (Table A1).

Scholars also subdivided the term minority into first and second order minorities, especially in ethnic studies (e.g., Gerken 2004; Barter 2015; Espesor 2019). Although the terms first and second order minorities are not commonly used in the context of religious minorities, for clarity and usability in future studies, we drew upon the work of Espesor (2019) to define first and second order minorities in the country by group size. Thus, the most recent census of Pakistan 2023 showed that the majority in Pakistan is Muslims (96.35%). The first order minority includes Hindu (1.61%) and Christian (1.37%) and the second order minority is schedule castes/others (0.6%) (Pakistan Bureau of Statistics 2023). Espesor (2019) also associated the second order minority with a lack of structural resources e.g., lowest political power, employment and education. We also defined minorities in terms of lower population and access to structural resources. However, we did not use this distinction in analysis.

The constitutions of different countries offer religious liberty, promise the provision of basic rights, and guarantee protection to minorities (Martin and Finke 2015). The First Amendment of the constitution of the United States of America, Article 10 of the fundamental rights of the European Union, and Section 116 of the constitution of Australia provide religious freedom to their people. Similarly, the constitution of China enshrines religious liberty, and the state discourages religious discrimination (Article 36). Articles 12, 14, and 26 of the Iranian constitution offer religious liberty, human respect, and political freedom to minorities, respectively. The constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan (CIRP) carries an explicit framework for minorities’ participation in state affairs and policy construction for their fundamental rights (article 36). Their security (Article 9), religious freedom (Article 20-A, B and 22-3A and B), and preservation of their culture (article 28) is fundamentally established in the CIRP. Articles 25(1) and 25(2) of the Indian Constitution grant religious freedom to minorities, offer propagation and practice of their religion, and allow interference in religious matters of the country. Like India, Bangladesh adopted the Secular State Model. Article 41 of its constitution states the provision of religious liberty, and Articles 12(d) and 28 discourage religious discrimination.

Although the promotion of pluralism is also stated in these constitutions, it has implementation problems due to the political system (Brathwaite 2015; Finke et al. 2017). These constitutions protect social, cultural, and religious rights yet the exploitation of the legal rights of minorities is evident because they are suffering from inequity (Wilde et al. 2018, 2025), inferiority and discrimination (Finke et al. 2017). They feel insecure about their constitutional rights, assets, religious places, and ceremonies due to the intolerance of the majority (Kim 2017). They are also conscious about their religious identity (Fox 2016). Therefore, they ensure distance from the majority to reduce the risk of their identity loss (Eghdamian 2017).

3. Majority and Minority Relations: The Continuum

In the early 1950s, MM relations were examined by the equation of “ifs and ought to be”—if X policy has been implemented, the MM relations would have been solved; the X policy ought to be implemented. Roucek (1956) criticized this approach and declared MM relations as the relations of power struggle. Harris (1958) included the struggle of achieving “comparable status” (p. 248) in the power struggle domain of Roucek by segregating MM relations between dominant and lower social sub-groups. In the same year, MM relations entered the conflict perspective as Wagley and Harris (1958) proposed the relations as persistent social conflict, arguing that ethnocentrism and endogamy are the strongest predictors of the relations. Nevertheless, the economic sphere was missing because, generally, power revolves around economic activities (Ferraz et al. 2025). Considering the marketplace as an important arena of economic interaction, Redekop and Hostetler (1966) specify MM relations as “the power to participate in decision making” (p. 378) because the economic sphere provides opportunities for social acceptance.

For one and a half decades, the conceptualization of MM relations was suffering from suggestions, proposals, and recommendations, and no theorization attempt was made until Eitzen (1967) substantiated the proposal of social conflict into a conflict model in 1967. Despite the vulnerability-, suppression-, and oppression-oriented literature, MM relations as a structural problem were already established (see e.g., Scott 1961; Hoetink 1963). His conflict model of MM relations, like Roucek, views the relations as (a) power relations with (b) an inherent struggle and conflict for the preponderance of power. By that time, the relations theoretically extended to politics, nation-state, and religion. MM relations were typified by intermingling with pluralism, assimilation, regionalism, and other related constructs. The typification by Wirth (1945) and Schermerhorn (1972) has this credit. However, Amersfoort (1982) criticized the previous typologies and defined minorities under MM relations on three dimensions: numerical, social, and political positions that included legal, educational, market, and family systems in the debate.

Latterly, MM relations were specified to asymmetric relations of the minority, keeping in view the general attitude of the majority and minority toward a nation-state (Smith 1986). This asymmetric relation was widely evaluated in the 20th century (see e.g., Lipponen et al. 2003; Huo 2003; Devos and Banaji 2005; Elkins and Sides 2007) that further extended to gender, development, and religious and political studies (Predelli et al. 2012; Ceva and Zuolo 2013; Long et al. 2017; Fuchs and Fuchs 2020). These studies stressed the “toleration model” because, other than power relations, asymmetric relations assume a subordination of minorities that represents coercive, intimidating, and hateful behavior of the majority towards minorities. Phan and Tan (2013) and Brie (2011) discussed such behavior in Asia and America to support their claim about interfaith dialogue. They argued that migration provides an opportunity for interfaith dialogue in MM relations (being power relations) among diverse religious populations that, supposedly, promote tolerance and acceptance of differences.

However, the tolerance model assumes latent hate (there is something wrong that needed to be tolerated) and it does not reveal the complexity of MM relations in a dynamic society. Disclosing the limitations in the tolerance model, Ceva and Zuolo (2013) introduced the “respect” model of MM relations. They argued that in the relations, at vertical (sociopolitical inequality with a minority) and horizontal levels (disrespectful behavior of a majority towards a minority), minorities should be respected as self-legislators “on an equal footing with the majority” (p. 250).

Despite the various dimensions of MM relations such as trust (Wilkes and Wu 2018), respect (Ceva and Zuolo 2013), prejudice (Small and Bowman 2011), and religious clash (Hauser-Schäublin and Harnish 2014), they have been discussed under the umbrella of power relations in which a political institution or government is one of the major elements. The interaction between politics and religion is subject to the interests of the agents of both institutions such as politicians and clergy (Fox 2018). Minorities have been perceived as threats to these interests (Kirkman 2013; Finke et al. 2017). Therefore, the government of the majority ensures the limited participation of minorities in politics (Ramadhan 2022) and socioeconomic spheres that leads to their inequal share of structural resources. Such inequality forced them to be a marginalized community (Bader 2005; Mander 2015; Imai et al. 2011; Thorat and Neuman 2012). We called such limitations and exclusion in MM relations the exploitation of minorities. Such exploitation promotes an asymmetric attitude among minorities toward nation-states or nationalism (Staerklé et al. 2010). However, variations in the degree of exploitation are associated with a type of government e.g., autocracy and democracy. Such is the case for Malaysia and Pakistan–democratic countries that have a high level of exploitation against specific minorities (Sarkissian et al. 2011, p. 435) compared with Libya, an autocratic country (Fox 2012). Therefore, we hypothesized that the exploitation of minorities under MM relations is subject to the unequal distribution of structural resources in Pakistan.

4. Theoretical Framework

This study seeks to reconceptualize the Marxian theory of exploitation by shifting the analytical focus from the economic field of class relations to the multi-dimensional social space of majority–minority (MM) relations. In the classical Marxian sense, exploitation is an inherent feature of the capitalist mode of production, rooted in the ownership of the means of production by the bourgeoisie and their systematic appropriation of surplus value from the proletariat (Marx 1887). This relationship is fundamentally antagonistic, predisposing the exploited class to a reaction against the exploiter (Marx and Engels [1848] 1967; Marx [1850] 2001).

While we retain Marx’s core relational logic—where the sustained advantage of one group is structurally linked to the disadvantage of another (Marx 1887, [1885] 1956, [1959] 1999)—we argue that this dynamic is not confined to the economic sphere. To theorize its operation in the religious and social domains, we integrate the sophisticated sociological framework of Pierre Bourdieu. Bourdieu’s work provides the tools to analyze power and domination beyond the factory floor, in the intricate realms of culture, religion, and everyday life (Mohamad Hanefar et al. 2025).

Central to Bourdieu’s model is the concept of the field (champ), defined as a structured social space with its own specific laws, logics, and forms of authority, akin to a competitive game (Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992). Society is composed of multiple, intersecting fields (e.g., the religious field, the bureaucratic field, the educational field). Within these fields, individuals and groups struggle for the accumulation and monopoly of different forms of capital. Beyond economic capital, Bourdieu theorizes cultural capital (embodied, objectified, and institutionalized forms of knowledge and credentials), social capital (resources based on network membership), and symbolic capital (the form any capital takes when it is recognized as legitimate) (Bourdieu 1986).

The “structural resources” central to our study—such as access to political office, high-status professions, and prestigious education—are, in this framework, concrete forms of institutionalized cultural capital and social capital. The religious majority, by virtue of its numerical preponderance and its ability to shape the doxa (the taken-for-granted beliefs) of the national field, maintains disproportionate control over these capitals. This dominance is not static; it is actively perpetuated through strategies of social reproduction, whereby the dominant group uses its position to transmit its advantages across generations (Bourdieu and Passeron 1990). A key mechanism in this process is symbolic violence, a “gentle, invisible violence, unrecognized as such, chosen as much as undergone” (Bourdieu 1990, p. 127). It is the imposition of systems of meaning and symbolism (e.g., the superiority of the majority religion) by a dominant group, which are then misrecognized as legitimate by the dominated, thereby making the social order appear natural and just.

Drawing upon this framework, we define the non-economic exploitation of religious minorities as the systematic process by which the religious majority, through its dominant position across key social fields, secures and reproduces its monopoly over institutionalized capital, leveraging symbolic violence to legitimize this order (Bourdieu 1996), thereby structurally limiting the minority’s ability to accumulate capital and reinforcing a cycle of domination. This relationship is exploitative in a Marxian-relational sense because the majority’s privileged access to and enjoyment of key capitals is predicated on the minority’s systematic exclusion from them.

The hypothesized reaction of the minority is conceptualized not as a call for economic revolution, but as a counter-strategy within the Bourdieusian “game”—an attempt to contest the unequal distribution of capital, challenge the legitimacy of the rules (symbolic violence), and redefine the value of their own cultural and religious capital within the field.

5. Material and Methods

We randomly selected 275 respondents (192 males, Mage = 24.5 years; 83 females, Mage = 23.4 years) from the largest three religious minorities of Southern Punjab (Christian = 170, Hindu = 84, and Sikh = 21) from 2023 to 2024. The sample size was calculated using Taro Yamane’s equation (1967, p. 886). We used the face-to-face interview schedule of the field survey method for data collection. Most of the respondents were illiterate or below primary education (69.5%) and working in lower-level jobs (75.3%). Due to fear of the majority’s intolerance, respondents hesitated to participate in the study. We assured them that their names would not appear in written documents and that the data given would only be used for academic purposes. Moreover, we also selected a focal person from each religious minority to help us with data collection, which contributed to reducing the level of intimidation among respondents. Those respondents who agreed to participate in the study were interviewed.

We aimed to measure the major variables of the exploitation hypothesis i.e., non-economic exploitation and reaction against it. Both variables were measured through a self-administered questionnaire that was translated into Urdu. The minorities could understand the language easily. However, we did not interview those respondents who could not understand the language. The measurement detail of each variable is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of exploratory factor analysis.

5.1. Assessment of the Non-Economic Exploitation Tool

To measure the non-economic exploitation of minorities, we used a self-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of the most significant indicators of exploitation, which were selected from previous literature. The questionnaire comprised eight items (see Table 1) that ranged from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The Cronbach’s Alpha of the questionnaire was 0.851. We used Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) to explore the latent factors of the exploitation. The results of the EFA revealed that the value of the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy was 0.75 and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was statistically significant, χ2 (28) = 1078.64, p < 0.001. We used Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for the extraction method, with the Varimax rotation method and Kaiser Normalization. Greater than one Eigenvalue was defined as a cut point (Johnson and Wichern 2007) for each exploitation sub-scale that signified three non-economic dimensions of exploitation i.e., social (s2 = 41.18, Cronbach α = 0.90, three items), cultural (s2 = 25.28, Cronbach α = 0.85, 3 items) and religious (s2 = 13.72, Cronbach α = 0.66, two items).

Accumulatively, the questionnaire accounted for 80% of the variance in the variables, and the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) confirmed the fit of the model: χ2 (17) = 41.7, p = 0.001, RMR = 0.41, GFI = 0.964, AGFI = 0.924, PGFI = 0.455, CFI = 0.977 and RMSEA = 0.073. It was reported in previous studies that RMSEA less than 0.08 is appropriate for model fit (Garnier-Villarreal and Jorgensen 2020).

5.2. Measurement of Other Variables

The reaction of minorities: The likelihood of the reaction of minorities against the majority was measured through two indicators, one of which indicates the intention of respondents to react against majority at community level (IAPA), such as peaceful or violent protest, and the second of which indicates the intention of respondents to react against politics and constitution (IANA). The second indicator showed the intention of reaction at a national level because the most imperative part of any country is politics and a constitution that represent the structure and mechanism of the country. Each indicator of the reaction was measured on a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 = Least Likely to 5 = Highly Likely. Before asking the question, we and a focal person from each minority briefed the respondents about their fundamental rights ratified in the CIRP of 1973, as well as the concepts of pluralism, nationalism, and exploitation, due to the nature of the questions. The explanation of the terms used in the questionnaire made it easier for respondents to comprehend the questionnaire fully.

The measurement of the first question (IAPA) reads, “Keeping in view your fundamental rights and the concepts of pluralism and nationalism, if you think that your religious community has been exploited, do you ever intend to react against the Muslim community by any means that you think would be effective?” A similar statement was used to measure IANA by substituting “Muslim community” with “Politicians and the Constitution.” We were aware that the question would not strictly measure the intentions of anti-national activities, but if we asked the respondents directly if they intended to conspire or revolt against the constitution or political parties of the country, we may have gotten a zero-variance measure. However, the questions measured the intentions of respondents that we aimed to calculate.

6. Geometrical Modelling of Non-Economic Exploitation

The concept of exploitation in the economic perspective is subject to the inverse welfare principle, which states that perpetuating the welfare of an exploiter is at the expense of the exploited—the appropriation of the efforts of the exploited and their exclusion from productive resources (Das 2017). The principle is based upon the class relations of production, in which exploiters own the means of production and struggle to have persistent control over productive resources through the exploitation of the proletariat.

However, we did not focus on the economic dimension of exploitation, and therefore distanced our theorization from class relations and the inverse welfare principle. We drew exploitation on the following principle:

- Exploitation in MM relations is subject to the authority principle, or

- 1a.

- MM relations of authority are relations of exploitation.

Authority refers to the legitimate proportion of control on structural resources—politics, bureaucracy, education, law, etc.—whereby a religiously homogeneous group that has a higher proportion of control on structural resources would have higher control over other homogeneous groups who have a less numerical share in the total heterogeneous population. Moreover, the authority of a religious homogeneous group lies in its numeric share in the total heterogeneous population within a defined territory. Therefore, the religious majority always has a higher proportion of authority in a defined territory. Thus, structural resources have become the major means of exploitation and the subject of struggle. Defining authority in terms of control over structural resources is a matter of exploitation at a structural level. Thus, MM relations are the relations of authority proportion: the relations of proportionate control on structural resources. In other words, the proportion of control on structural resources by one group defines the proportion of authority of this group within MM relations.

Drawing upon the Marxist perspective, we assume that structural resources are the property of the masses. A group should not own and should not be legitimatized to accumulate all available resources because such a preponderance leads to exploitation. In MM relations, the control over structural resources is unequally distributed in Pakistan (see Figure 1), which we call asymmetric exclusion in the distribution of structural resources. Thus, in MM relations, exploitation refers to the proportion of asymmetric exclusion of a group. Our definition is based on the work of Vrousalis (2013), who defined exploitation as “a form of domination” for self-enrichment (p. 131). It highlights that discrimination (unfair treatment of a group based on religion and other characteristics) is an ultimate indicator of exploitation (Giammarinaro 2022)—as Boufkhed et al. (2024) operationalized—because it could occur independently of productivity (Roemer and Roemer 1978).

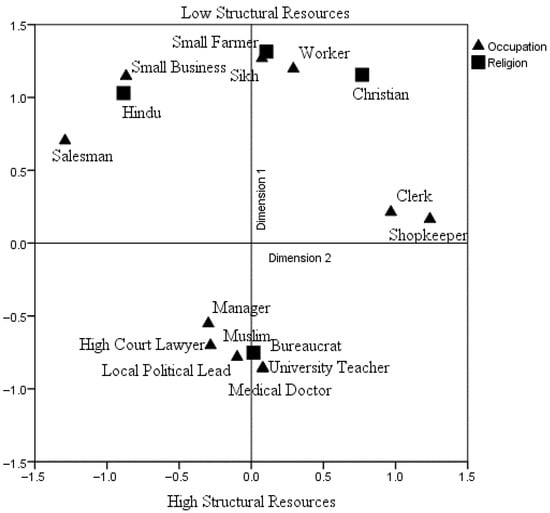

Figure 1.

MM relations in terms of control on structural resources. Dimension 1: inertia = 0.766; Dimension 2: inertia = 0.037; χ2 = 251.544, p = 0.000.

However, self-enrichment is not restricted to a person; it could be “groups or coalitions of optimizing agents”. A group dominates another group to ensure its benefits—an increase in the wellbeing of a group. Drawing upon this definition, we argue that control over structural resources by a group is a form of authority over another group. Therefore, we defined the exploitation of minorities in MM relations in terms of their asymmetric exclusion.

Bourdieu (1984) found that economic and cultural resources (e.g., education) are unequally distributed across occupations using relational logic. We used the same method to explore the pattern of distribution of resources across occupations. Following Bourdieu’s (1984, 1996) method of theorization that combines theory and data, we conducted a survey to theorize non-economic dimensions of exploitation. Figure 1 showed the results of the correspondence analysis. Minorities (n = 120) and a majority (n = 185) from Multan participated in the study (the methods for this survey are given in “Methods and Materials”). Figure 1 showed that Muslims have a higher proportion of control over legitimate structural resources than minorities. Therefore, they have higher authority than minorities. This geometrical representation vividly illustrates the unequal distribution of capital that constitutes the foundation of non-economic exploitation. The correspondence analysis reveals a stark division in the social space. The majority (Muslims) is clustered around positions rich in institutionalized cultural and social capital—such as “University teacher,” “Medical doctor,” and “Bureaucrat.” These positions represent dominance within the state and professional fields. In contrast, the religious minorities are clustered in positions with lower overall volumes of capital, such as “Worker” and “Small farmer.”

This visualization is a snapshot of the social closure exercised by the dominant group. It empirically demonstrates how the religious majority maintains its monopoly over key capital, restricting the minority’s access to the very resources required for social mobility and political influence. The distance between the clusters is a measure of the symbolic violence inherent in the system—the naturalization of this unequal order. The frequency and percentage distribution of structural resources across religions are given in Appendix B (Table A2).

Figure 1 shows one aspect of asymmetric exclusion in MM relations. The second aspect is the perpetuation of the exclusion whereby exploitation survived any attempt to change MM relations (which we call reaction) such as a political movement against asymmetric exclusion. Therefore, MM relations are not only a matter of unequal distribution but also a restriction on access to the resources as well, because they strengthen and facilitate the perpetuation of established asymmetric exclusion, which in turn strengthens established MM relations. In other words, the perpetuation of restriction itself is the perpetuation of exploitation. A group of people with accumulated resources restricts others from entering the group. Weber (1946) called such groups “Stände” (Waters and Waters 2016), Mills (1956) labelled it “power elite” (Phillips 2018), and Bourdieu termed it the “dominant class” (Lebaron 2018). Although Marx also pointed out such restrictions and exclusion, it was confined to the economic dimension. The Stände, power elite, and dominant class revealed the unequal distribution of non-economic resources such as the cultural capital theory of Bourdieu. The dominant class owns cultural and economic resources and reproduces the resources through several strategies such as educational and marital strategy i.e., securing academic credentials to acquire higher-level jobs in the market and marrying within a similar cultural and economic group in order to perpetuate the social position of a family across generations. Similarly, Stände do not consist of economic resources only; they are circles whose members are culturally homogenous, forming social closure to restrict others from entering the circle.

In order to perpetuate the restriction and the monopoly over resources, the members use different strategies such as the connubial strategy, which is similar to the marital strategy in Bourdieu’s reproduction thesis. The power elite, a homogeneous group, has similar socialization, education, and occupations. Therefore, in order to perpetuate the monopoly and exploitation, two strategies are of the highest importance:

- i.

- Accumulation of resources;

- ii.

- Perpetuation of social closure.

The strategies are related to each other and have various sub-strategies such as marital and educational strategies. To accumulate resources, the perpetuation of already established closure is necessary, otherwise the accumulation would be threatened by distribution. Similarly, to perpetuate the closure, the accumulated resources available must be distributed within the circle. In this process, the sub-strategies protect the main strategies of exploitation. Marriage within the same rank ensures the distribution of accumulated resources within the circle or group. However, academic credentials affirm accumulation of cultural and economic resources. Moreover, one important resource, i.e., social, highly contributes to the affirmation that the accumulated resources will not be wasted because it ensures the safety of the resources by ensuring that the “closed network” will distribute the accumulated resources within the network.

This non-economic dimension of capital has extended the field of exploitation. However, exploitation is outside of the conceptual domains of these theories. Therefore, we attempted to build an empirical model of exploitation on a non-economic dimension, which aimed to evaluate the hypothesis that the degree of non-economic exploitation, which can be called the proportion of exclusion of a group from access to structural resources, is positively associated with reaction of the excluded group against the exclusion.

7. Structural Equation Modeling of Non-Economic Exploitation

Initially, we conducted a preliminary analysis, i.e., the correlation between predictors and outcomes. The significant correlation coefficients among predictors ranged between r = 0.127, p < 0.05 to r = 0.77, p < 0.001. The predictors were also significantly correlated with outcomes (p < 0.001). Most of the predictors were reasonably correlated with outcomes except E4 and E6 (p > 0.05). E1 and E5 showed the lowest correlation with IAPA and IANA (ranging from r = 0.13 to r = 0.37). Other than non-significant items, the rest of the predictors were significantly correlated with outcomes. Further, males have been more exploited socially (M = 5.52, SD = 2.29, t (273) = 4.6) and religiously (M = 3.16, SD = 1.21, t (273) = 4.07) than females (p < 0.001). However, we found no significant difference in social, F (2, 274) = 0.867, cultural, F (2, 274) = 0.837, and religious, F (2, 274) = 0.815, exploitation across religious minorities.

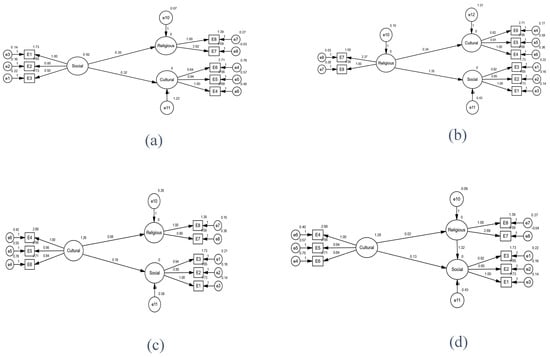

The first step of our analysis was to model predictors whereby the nature of relationships among predictors and the model that best fit the data could be explored. In order to explore the model, we evaluated all possible models by incorporating predictors only (see Table 2). We found that R1 and S1 were the most reasonable models because they significantly fit the data better than other models of predictors. Although goodness of fit indexes such as χ2, GFI, and AGFI indicated a plausible fit of the model R1 and S1, the values of RMSEA (0.07) and RMR (0.041) showed comparatively better fit for the model S1 than all other models of predictors i.e., R1, C1, Z1.

Table 2.

Description of models’ fit.

The model S1 (see Figure 2b) showed that social exploitation significantly predicted religious (β = 0.20, SE = 0.047) and cultural exploitation (β = 0.32, SE = 0.097, p < 0.001). However, it would not be reasonable to claim that cultural and religious dimensions of exploitation did not predict social exploitation. In fact, we found that religious exploitation in R1 has the highest regression coefficients to predict social (β = 1.35, SE = 0.198, p < 0.001) and cultural exploitation (β = 0.34, SE = 0.245, p > 0.05) (see Figure 2a). However, the model poorly fitted the data comparatively, but considering all models of predictors, including mediation models (see Figure 2d), it can be inferred that the religious and social exploitations are more strongly associated than other possible associations among predictors such as the association between religious and cultural exploitation.

Figure 2.

Models of predictors including mediation models: (a) Model R1; (b) Model S1; (c) Model C1; (d) One of the Z1 Models.

The structural equation models reveal the internal dynamics of this exploitative system. The finding that religious exploitation is the strongest predictor (in model R1) is theoretically significant. It suggests that the religious field is the primary locus of symbolic struggle; the legitimacy or stigma attached to a religious identity fundamentally structures one’s position in the broader social space. When a religious identity is systematically devalued—a core mechanism of symbolic violence—it facilitates and legitimizes exclusion from other forms of capital, such as social and cultural capital. This demonstrates that religious domination is not an isolated prejudice but the key lever that activates and reinforces the entire structure of non-economic exploitation.

The second step was to incorporate outcome variables in the models to explore which model of the predictors fit the data and significantly predicted each outcome variable. All models (from M1 to M6) incorporated R1, C1, S1, and the effect of each predictor on IAPA and IANA. As expected, M3 and M6 poorly fitted the data because these models included C1 which had a poor fit in the previous analysis (see Figure 2c).

Among the models that aimed to predict IAPA, M2 plausibly fitted the data (RMSEA = 0.064, RMR = 0.039, and χ2 = 48.7) better than M1 and M2. Similarly, M5 was more reasonably fitted (RMSEA = 0.072, RMR = 0.039 and χ2 = 55.73) to predict IANA than M4 and M6. The regression coefficients in M2 showed a significant relationship between religious exploitation (β = 1.6, SE = 0.216, p < 0.001) and IAPA. However, social and cultural exploitation was insignificant (p > 0.05). Similarly, M5 showed that religious exploitation is more strongly related to IANA (β = 2.17, SE = 0.237, p < 0.001) than IAPA. However, the other two predictors were insignificantly related to IANA (p > 0.05).

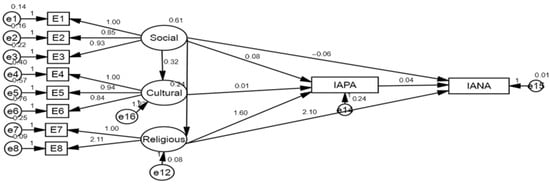

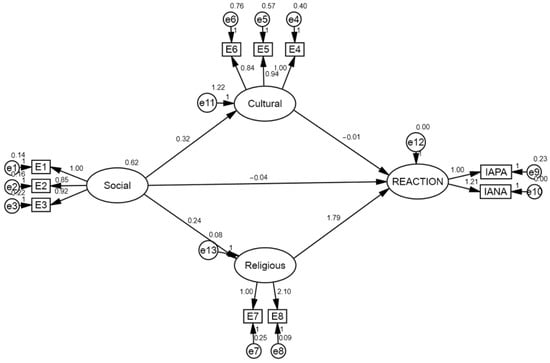

The full models that incorporated both outcomes, simultaneously, reasonably fitted the data and showed a very slight difference in fit indexes to the previous model. M7 was introduced in order to evaluate whether IAPA mediated between predictors and outcomes (see Figure 3). However, M8 used intentions to react against exploitation as a latent factor of observed variables i.e., IAPA and IANA (see Figure 4). This model was constructed in order to evaluate the effect of predictors on a composite measure of outcomes. Considering the fact that both models fitted the data, we selected M8 as the best model of exploitation and reaction on non-economic dimension (RMSEA = 0.072, RMR = 0.039, and χ2 = 55.73), although M7 had a slightly better fit than M8. The later model, on the one hand, had a statistical reason to be selected and, on the other hand, had an advantage of interpretability over the former model. First, in M7, IAPA did not significantly predict IANA (p > 0.05). Second, M8 remained consistent with measures of reaction by using it as a latent variable, consisting of IAPA and IANA, by which the model directly evaluated the effect of predictors on the intentions to react against exploitation. Third, the regression coefficients in both models showed an insignificant effect of social and cultural exploitation on the outcome(s), and a significant effect of religious exploitation on observed variables and the latent factor. Therefore, the selection of M8 did not cause any statistical or theoretical violation. M8 showed that only religious exploitation (β = 1.79, SE = 0.219) has a significant positive effect on intentions to react against the exploitation. The model also showed that social exploitation has an unstandardized total and indirect effects of 0.38 and 0.43 on latent factors, respectively (see Table 3).

Figure 3.

Structural equation model, M7.

Figure 4.

Structural equation model, M8.

Table 3.

Direct, indirect and total effect of predictors on outcome(s).

In the theory of Marx and Bourdieu, alienation and symbolic violence, respectively, may also serve as interpretative tools for exploitation and reaction. However, the theory of symbolic violence is closer to the non-economic dimension of exploitation. Nevertheless, it does not signify exploitation but an unfair exercise of power (Thapar-Björkert et al. 2016; Watkins 2018). Similarly, other sociological theories e.g., Stände and the power elite, also described the use of power and cultural patterns to form a social closure in order to sustain the monopoly over accumulated resources (Hoffmann-Lange 2018; Evans 2018), which is also closer to the non-economic dimension of exploitation. However, these studies, except Althusser’s, did not theoretically support and propose ‘the reaction’. Thus, the study empirically incorporated this neglected aspect that benefited from these theories, and extended the theory of exploitation in MM relations.

8. Discussion

This study moved beyond cataloging types of exploitation to test a theoretical model examining whether non-economic exploitation provokes a reaction from religious minorities. Framed by our Bourdieusian synthesis, we proposed that the majority perpetuates its dominance through a system of social reproduction, maintaining a monopoly over institutionalized capital (structural resources) across key social fields. Our findings confirm this structural inequality—supporting previous studies (Alam 2020; Jaffrelot 2020; Khalid and Rashid 2019; Advani 2016)—demonstrating that the struggle is fundamentally over capital. More importantly, the results reveal the internal dynamics of this system: exploitation rooted in the religious field—a primary site of symbolic violence—serves as the cornerstone, enabling and legitimizing exclusion in social and cultural fields. This multi-dimensional domination, in turn, generates a latent conflict, predisposing the minority to a reaction aimed at contesting the unequal distribution of capital.

The first factor that ensures this inequality is the constitution of a country. Khalid and Rashid (2019) asserted that CIRP is one of the structural factors of the social, religious, and cultural exploitation of religious minorities. Our findings concurred with Khalid and Rashid (2019) and Julius (2016) who explored the ways in which the laws of Pakistan have been used against minorities as an exploitation tool. Considering the political and constitutional biases, this study also supported the argument of Ispahani (2016, 2018) who stated that the political and constitutional structure of Pakistan breeds intolerance against religious minorities. As Article 2 of the Constitution of Afghanistan of 2004 promises religious freedom and Article 3 ensures the supremacy of Islam, a similar contradiction can be found between Article 227 and Article 20-A of CIRP. Crouch (2012) also pointed out that Article 70 of the Constitution of Indonesia of 1945 tempered the religious freedom of minorities, which is provided in Article 29. However, Crouch (2012) and Finke (2013) claimed that constitutional biases are intermingled with the government of the majority because the government restricts the political representation of minorities (Qasmi 2015) where a constitution can be amended. In Pakistan, religious minorities have 10 reserved seats in the national assembly (Article 51-4A) which they can occupy through a defined proportional system—proportional to the secured seats by each political party in the general electoral system (Article 51-6E). Javaid and Jalal (2019) signified such an interrelationship between politics and the constitution by stating that the Christians of Pakistan “have not only been victims of misuse of some of religious laws, but they also have little or no role in the law-making process that influences them. System of electorate [sic] has undermined their status as equal citizens of Pakistan. Their seclusion from national mainstream and resultant political and social insecurity has worsened over the period of time (p. 35).”

The constitutional and political relationship between the religious majority is a prime measure of the exploitation of minorities because they are restricted in accessing structural resources (Cheung 2014; Fox et al. 2018). In addition, the sub-scales of such exploitation are interrelated, as Cheung (2014) found that religiously exploited minorities also suffer from employment penalties because governmental policies are designed for the majority groups. This forms their alien identity and reduces national sentiments. Gabriel (2021) signified such an interrelationship of exploitation of religious minorities by stating that they feel “marginalized and alienated” (p. 104) from mainstream life. However, previous studies also affirmed that social exploitation e.g., lack of opportunities and marginalization (Tahir and Tahira 2016; Shah et al. 2018; Ahmed and Zahoor 2020) of religious minorities is the effects of religion. Our findings supported these interrelationships of exploitation levels.

The findings of Grim and Finke (2007, 2011) revealed governmental restrictions as well as a culture of a country that increased the persecution of religious minorities. This study also supported their findings, especially the predictor model about the interrelationship of exploitation levels. However, we propose that this exploitation leads to a reaction from minorities. Our findings supported the studies by Finke and Harris (2012), Martin and Finke (2015), and Finke (2013), who found that religious restrictions lead to violence. Specifically, the predictor model of religious and social exploitation is consistent with the findings of these studies. Our study also concurred with Wellman and Tokuno (2004) about the religious boundaries of the social dimension. They argued that such boundaries increased inter-group conflict. The theory of Marx and Bourdieu i.e., alienation and symbolic violence, respectively, may also serve as interpretative tools for exploitation and reaction. However, the theory of symbolic violence is closer to the non-economic dimension of exploitation. Nevertheless, it does not signify exploitation but an unfair exercise of power (Thapar-Björkert et al. 2016; Watkins 2018). Similarly, other sociological theories e.g., Stände and the power elite, also described the use of power and cultural patterns to form a social closure in order to sustain the monopoly over accumulated resources (Hoffmann-Lange 2018; Evans 2018), which is also closer to the non-economic dimension of exploitation. However, these studies, except Althusser’s, did not theoretically support and propose ‘the reaction’. Thus, this study empirically incorporated this neglected aspect that benefited from these theories by extending the theory of exploitation in MM relations.

9. Conclusions

The study concludes that majority–minority relations are structured by a system of non-economic exploitation, theorized through a Bourdieusian lens as the unequal distribution of capital across social fields, which the majority perpetuates through social reproduction and symbolic violence. The majority perpetuates its dominance through strategies of social reproduction and social closure, monopolizing institutionalized cultural capital (structural resources) while deploying symbolic violence to legitimize this order.

We found that religious exploitation is the cornerstone of this system—although previous studies (e.g., Crouch 2012; Ispahani 2016, 2018) proposed politics or constitution—as devaluation in the religious field powerfully enables exclusion in social and cultural fields. This multi-dimensional exploitation generates a latent conflict, predisposing the minority to a reaction aimed at reclaiming capital and challenging the rules of the game. The conclusion that minority-majority relations are exploitative in non-economic terms provides a necessary, granular data point for policymakers working to implement SDG 10 by 2030, particularly in strengthening the rule of law and promoting non-discrimina-tory policies.

However, the likelihood of reactions of minorities against the majority may not be treated as a revolution proposal but a conflict. The sustainability of such exploitation is identical to the reproduction of non-economic exploitation. Therefore, the proposed policy measures should be understood as interventions aimed at disrupting the specific mechanisms of social reproduction identified in our study:

- Replacing the quota system with open merit is a direct challenge to social closure. It seeks to reorient the allocation of capital from ascriptive religious group membership toward individual cultural capital (credentials and skills), thereby altering the structure of the bureaucratic and educational fields.

- Increasing political representation is about granting minorities a greater voice within the political field—the meta-field where the rules of other fields are often codified into law. This is a fundamental step in contesting the symbolic violence embedded in the legal framework.

This study demonstrates that sustainable change requires not only policy reforms but a fundamental challenge to the symbolic order that legitimizes this structure of non-economic exploitation.

The study recommends that the basic rights enshrined in the constitution of Pakistan should be implemented by providing minorities fair access to education, and the quota system of employment and education should be replaced with the open merit system. This can be achieved by increasing the political representatives of the minorities in the National Assembly where they could play a significant role in constitutional amendments.

10. Limitations

We did not include qualitative data in the study, which weakens the anthropological description of the exploitation model. We did not aim to replicate the description of vulnerability of minorities available in qualitative studies, but rather to extend the existing body of knowledge on MM relations. Therefore, we relied upon the data-driven theory approach of Bourdieu. The quantitative approach increased the generalizability of the findings. We are well aware that generalizability is confined to religious minorities only as we limit the study to the religious dimension. Therefore, another prime limitation of the study in terms of its generalizability is race and ethnicity. Previous studies widely focused on these aspects to deal with the power relations among groups, which can be extended, and we suggest using MM relations models to explore the non-economic dimension of exploitation.

We presented the operationalization of the reaction of minorities against non-economic exploitation, which meant reducing the level of exploitation. However, this study was limited to measuring whether the exploitation subscales are likely to provoke the reaction. It does not explore the results of the reaction and the chain of events that lead to a successful reaction. Therefore, we also suggest that future studies may include the effectiveness of the reaction so that the exploitation hypothesis can cover the results of the reaction as well. An important factor in doing so is the use of first and second order minorities, because some previous studies (e.g., Espesor 2019) explored whether second order minorities are the major agents of violent reaction against the authorities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.F.; methodology, S.F. and M.R.; software, M.R.; validation, A.F.; formal analysis, S.F.; investigation, A.F.; resources, M.F.; writing—original draft preparation, S.F.; writing—review and editing, M.F.; visualization, S.F.; supervision, S.F.; project administration, S.F. and M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board(IRB) University of Okara(Pakistan) (protocol code No.UO-ORIC-IRB-2024/66 and 2024-09-02 approval).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Percentage distribution of religious composition by countries.

Table A1.

Percentage distribution of religious composition by countries.

| Country | Christian | Muslim | Hindu | Other Religion | Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 0.1 | 99.7 | <0.1 | <0.1 | 31,410,000 |

| Australia | 67.2 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 22,270,000 |

| Bangladesh | 0.2 | 89.8 | 9.1 | <0.1 | 148,690,000 |

| Canada | 69.0 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 34,020,000 |

| Egypt | 5.1 | 94.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | 81,120,000 |

| France | 63.0 | 7.5 | <0.1 | 0.2 | 62,790,000 |

| Germany | 68.1 | 5.8 | <0.1 | 0.1 | 82,300,000 |

| India | 2.5 | 14.4 | 79.5 | 2.3 | 1,224,610,000 |

| Japan | 1.6 | 0.2 | <0.1 | 4.7 | 126,540,000 |

| Mexico | 95.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | 113,420,000 |

| Pakistan | 1.6 | 96.4 | 1.9 | <0.1 | 173,590,000 |

| Russia | 73.3 | 10.0 | <0.1 | <0.1 | 142,960,000 |

| Saudi Arabia | 4.4 | 93.0 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 27,450,000 |

| South Africa | 81.2 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 50,130,000 |

| United Kingdom | 71.1 | 4.4 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 62,040,000 |

| United States | 78.3 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 310,380,000 |

Source: Pew Research Center (2012). Global Religious Landscape. Note: Percentages are based on 2010, and the Percentage of the category “Other Religion” excludes unaffiliated, Buddhist, Folk Religion, and Jewish.

Appendix B

Table A2.

Frequency and percentage distribution of structural resources across religion.

Table A2.

Frequency and percentage distribution of structural resources across religion.

| Structural Resources | Christian | Hindu | Sikh | Muslim | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f (%) | f (%) | f (%) | f (%) | ||

| Bureaucrat | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 23 (100.0) | 23 (100.0) |

| Local political leader | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 51 (96.2) | 53 (100.0) |

| Salesman | 1 (25.0) | 2 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) | 4 (100.0) |

| Shopkeeper | 3 (27.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (18.2) | 6 (54.5) | 11 (100.0) |

| University teacher | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 44 (100.0) | 44 (100.0) |

| High court lawyer | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (92.3) | 13 (100.0) |

| Manager | 1 (3.7) | 3 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 23 (85.2) | 27 (100.0) |

| Medical doctor | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (100.0) | 15 (100.0) |

| Clerk | 3 (37.5) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (50.0) | 8 (100.0) |

| Small farmer | 13 (35.1) | 12 (32.4) | 11 (29.7) | 1 (2.7) | 37 (100.0) |

| Worker | 15 (33.3) | 12 (26.7) | 15 (33.3) | 3 (6.7) | 45 (100.0) |

| Small businessman | 5 (20.0) | 10 (40.0) | 8 (32.0) | 2 (8.0) | 25 (100.0) |

| Total | 41 (13.4) | 43 (14.1) | 36 (11.8) | 185 (60.7) | 305 (100.0) |

References

- Advani, Avinash. 2016. An Increasing the migration of Minorities in Pakistan. Arts and Social Sciences Journal 7: 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Zahid Shahab, and Musharaf Zahoor. 2020. Impacts of the ‘War on Terror’ on the (De-) Humanization of Christians in Pakistan: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Media Reporting. Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations 31: 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, Parvez. 2020. Populist Majoritarianism in India and Pakistan: The Necessity of Minorities. In Minorities and Populism–Critical Perspectives from South Asia and Europe. Edited by Volker Kaul and Ananya Vajpeyi. Cham: Springer, pp. 199–213. [Google Scholar]

- Amersfoort, Hans Van, ed. 1982. Minority as a sociological concept. In Immigration and the Formation of Minority Groups: The Dutch Experience 1945–1975. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 10–30. [Google Scholar]

- Amnesty International. 2016. “As Good as Dead”: The Impact of The Blasphemy Laws in Pakistan. London: Amnesty International Ltd. Available online: https://www.amnesty.org/fr/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/ASA3351362016ENGLISH.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Amnesty International. 2023. Pakistan: Authorities Must Protect Christians Against Vicious ‘Blasphemy’ Attacks. Press Release. Available online: https://www.amnesty.org.uk/press-releases/pakistan-authorities-must-protect-christians-against-vicious-blasphemy-attacks (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Bader, Veit. 2005. Associative democracy and minorities within minorities. In Minorities Within Minorities: Equality, Rights and Diversity. Edited by Avigail Eisenberg and Jeff Spinner-Halev. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 319–339. [Google Scholar]

- Barter, Shane Joshua. 2015. ‘Second-order’ ethnic minorities in Asian secessionist conflicts: Problems and prospects. Asian Ethnicity 16: 123–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basedau, Matthias, Jonathan Fox, Jan H. Pierskalla, Georg Strüver, and Johannes Vüllers. 2017. Does discrimination breed grievances—And do grievances breed violence? New evidence from an analysis of religious minorities in developing countries. Conflict Management and Peace Science 34: 217–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boufkhed, Sabah, Nicki Thorogood, Cono Ariti, and Mary Alison Durand. 2024. ‘They treat us like machines’: Migrant workers’ conceptual framework of labour exploitation for health research and policy. BMJ Global Health 9: e013521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. Forms of Capital. In The RoutledgeFalmer Reader in Sociology of Education. Edited by S. Ball. London: RoutledgeFalmer. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1990. The Logic of Practice. Redwood City: Stanford University Press, pp. 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1996. The State Nobility: Elite Schools in the Field of Power. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre, and Jean-Claude Passeron. 1990. Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre, and Loïc J. D. Wacquant. 1992. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brathwaite, Robert Thuan. 2015. Social Distortion: Democracy and Social Aspects of Religion—State Separation. Journal of Church and State 57: 310–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brie, Mircea. 2011. Ethnicity, Religion and Intercultural Dialogue in the European Border Space. Eurolimes 2011: 11–18. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-329431 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Bush, Ray, and Giuliano Martiniello. 2017. Food riots and protest: Agrarian modernizations and structural Crises. World Development 91: 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceva, Emanuela, and Federico Zuolo. 2013. A Matter of Respect: On Majority–Minority Relations in a Liberal Democracy. Journal of Applied Philosophy 30: 239–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Anita. 2016. China’s Workers Under Assault: Exploitation and Abuse in a Globalizing Economy: Exploitation and Abuse in a Globalizing Economy. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, Sin Yi. 2014. Ethno-religious minorities and labour market integration: Generational advancement or decline? Ethnic and Racial Studies 37: 140–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, Melissa. 2012. Judicial review and religious freedom: The case of Indonesian Ahmadis. Sydney Law Review 34: 545–72. [Google Scholar]

- Das, Raju J. 2017. Analytical Marxist Theory of Class. In Marxist Class Theory for a Skeptical World. Leiden: Brill, pp. 22–73. [Google Scholar]

- Devos, Thierry, and Mahzarin R. Banaji. 2005. American = White? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 88: 447–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eghdamian, Khatereh. 2017. Religious identity and experiences of displacement: An examination into the discursive representations of Syrian refugees and their effects on religious minorities living in Jordan. Journal of Refugee Studies 30: 447–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eitzen, D. Stanley. 1967. A conflict model for the analysis of majority-minority relations. Kansas Journal of Sociology 3: 76–89. [Google Scholar]

- Elkins, Zachary, and John Sides. 2007. Can institutions build unity in multiethnic states? American Political Science Review 101: 693–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espesor, Jovanie Camacho. 2019. Perpetual Exclusion and Second-Order Minorities in Theaters of Civil Wars. In The Palgrave Handbook of Ethnicity. Edited by Steven Ratuva. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillian, pp. 967–92. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Lisa. 2018. Shifting strategies: The pursuit of closure and the ‘Association of German Auditors’. European Accounting Review 27: 683–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, Diogo, Irum Shahzadi, Herick Fernando Moralles, and Buhari Doğan. 2025. The impact of financial development and economic complexity on energy and carbon intensity: Evidence of the top 10 complex countries. Energy Sources, Part B: Economics, Planning, and Policy 20: 2516447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finke, Roger. 2013. Origins and Consequences of Religious Restrictions: A Global Overview. Sociology of Religion 74: 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finke, Roger, and Jaime Harris. 2012. Wars and Rumors of Wars: Explaining Religiously Motivated Violence. In Religion, Politics, Society and the State. Edited by Jonathan Fox. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Finke, Roger, Robert R. Martin, and Jonathan Fox. 2017. Explaining discrimination against religious minorities. Politics & Religion 10: 389–416. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann, Fenella, and Karen Phalet. 2016. Identity conflict or compatibility: A comparison of Muslim minorities in five European cities. Political Psychology 37: 447–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, Jonathan. 2012. A World Survey of Religion and the State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, Jonathan. 2016. The Unfree Exercise of Religion: A World Survey of Discrimination Against Religious Minorities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, Jonathan. 2018. An Introduction to Religion and Politics: Theory and Practice. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, Jonathan, Roger Finke, and Dane R. Mataic. 2018. New data and measures on societal discrimination and religious minorities. Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion 14: 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, Maria-Magdalena, and Simon Wolfgang Fuchs. 2020. Religious minorities in Pakistan: Identities, citizenship and social belonging. South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies 43: 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, Theodore. 2021. Christian Citizens in an Islamic State: The Pakistan Experience. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Garnier-Villarreal, Mauricio, and Terrence D. Jorgensen. 2020. Adapting fit indices for Bayesian structural equation modeling: Comparison to maximum likelihood. Psychological Methods 25: 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerken, Heather K. 2004. Second-order diversity. Harvard Law Review 118: 1099. [Google Scholar]

- Giammarinaro, Maria Grazia. 2022. Understanding severe exploitation requires a human rights and gender-sensitive intersectional approach. Frontiers in Human Dynamics 4: 861600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, Julie. 2018. The condition of the working class in Shenzhen. Dissent 65: 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grim, Brian J., and Roger Finke. 2007. Religious persecution in cross-national context: Clashing civilizations or regulated religious economies? American Sociological Review 72: 633–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grim, Brian J., and Roger Finke. 2011. The Price of Freedom Denied: Religious Persecution and Violence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Marvin. 1958. Caste, class, and minority. Social Forces 37: 248–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser-Schäublin, Brigitta, and David D. Harnish. 2014. Between Harmony and Discrimination: Negotiating Religious Identities Within Majority-Minority Relationships in Bali and Lombok. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Hoetink, H. 1963. Change in Prejudice: Some Notes on the Minority Problem, with References to the West Indies and Latin America. Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land-en Volkenkunde 119: 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann-Lange, Ursula. 2018. Methods of Elite Identification. In The Palgrave Handbook of Political Elites. Edited by Heinrich Best and John Higley. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Rights Commission of Pakistan. 2019. Faith-Based Discrimination in Southern Punjab: Lived Experiences Field Investigation Report. Lahore: H.R.C.P. Available online: https://hrcp-web.org/hrcpweb/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/2019-Faith-based-discrimination-in-southern-Punjab.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Huo, Yuen. 2003. Procedural justice and social regulation across group boundaries: Does subgroup identity undermine relationship-based governance? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 29: 336–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, Katsushi, Raghav Gaiha, and Woojin Kang. 2011. Poverty, inequality and ethnic minorities in Vietnam. International Review of Applied Economics 25: 249–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ispahani, Farahnaz. 2016. Purifying the Land of the Pure: Pakistan’s Religious Minorities. Gurugram: HarperCollins India. [Google Scholar]

- Ispahani, Farahnaz. 2018. Constitutional issues and the treatment of Pakistan’s religious minorities. Asian Affairs 49: 222–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffrelot, Christophe. 2020. Minorities Under Attack in Pakistan. In Minorities and Populism–Critical Perspectives from South Asia and Europe. Cham: Springer, pp. 173–82. [Google Scholar]

- Javaid, Umbreen, and Iqra Jalal. 2019. Critical Analysis of Political Security of Christians in Pakistan. Pakistan Vision 20: 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Richard, and Dean Wichern. 2007. Applied Multivariate Analysis. Hoboken: Pearson Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Julius, Qaiser. 2016. The Experience of Minorities Under Pakistan’s Blasphemy Laws. Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations 27: 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, Iram, and Muhammad Rashid. 2019. A Socio Political Status of Minorities in Pakistan. Journal of Political Studies 26: 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Heewon. 2017. Understanding Modi and minorities: The BJP-led NDA government in India and religious minorities. India Review 16: 357–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkman, David M. 2013. State Responses to Minority Religions. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lebaron, Frédéric. 2018. Pierre Bourdieu, geometric data analysis and the analysis of economic spaces and fields. Forum for Social Economics 47: 288–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipponen, Jukka, Klaus Helkama, and Milla Juslin. 2003. Subgroup identification, superordinate identification and intergroup bias between the subgroups. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 6: 239–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Ahmad Sunawari, Zaizul Ab. Rahman, Ahamed Sarjoon Razick, and Kamarudi Salleh. 2017. Muslim socio-culture and majority-minority relations in recent Sri Lanka. Journal of Politics and Law 10: 105–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mander, Harsh. 2015. Looking Away: Inequality, Prejudice and Indifference in New India. New Delhi: Speaking Tiger. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Robert R., and Roger Finke. 2015. Defining and Redefining Religious Freedom: A Quantitative Assessment of Free Exercise Cases in the U.S. State Courts, 1981–2011. In Religious Freedom in America: Constitutional Roots and Contemporary Challenges. Edited by Allen D. Hertzke. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, pp. 91–116. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, Karl. 1887. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume I Book One: The Process of Production of Capital. Delhi: Progress Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, Karl. 1956. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume II Book One: The Process of Circulation of Capital. Delhi: Progress Publishers. First published 1885. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, Karl. 1999. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Volume III The Process of Capitalist Production as a Whole. Delhi: Progress Publishers. First published 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, Karl. 2001. The Class Struggle in France, 1848–1850. London: Electric Books. First published 1850. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. 1967. The Communist Manifesto. Translated by Samuel Moore. London: Penguin. First published 1848. [Google Scholar]

- Medda-Windischer, Roberta. 2017. Old and new minorities: Diversity governance and social cohesion from the perspective of minority rights. Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, European and Regional Studies 11: 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, C. Wright. 1956. The Power Elite. New York: Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamad Hanefar, Shamsiah Banu, Bensaid Benaouda, Ahmad Faizuddin, and Sharmila Devi Ramachandaran. 2025. Mapping the landscape of spiritual intelligence: A bibliometric analysis of trends, patterns and future directions. Journal of Religion and Health 64: 3419–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, Lisa. 2018. Political Protest in Contemporary Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. 2023. 7th Population & Housing Census 2023. (pbs.gov.pk). Available online: https://www.pbs.gov.pk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/National-Census-Report-2023.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Pew Research Center. 2012. The Global Religious Landscape. Available online: https://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2012/12/globalReligion-tables.pdf?_gl=1*1hvlwqb*_up*MQ..*_gs*MQ..&gclid=EAIaIQobChMI8PPzjJjTkAMVBaSDBx3a5haHEAAYASAAEgLIOfD_BwE&gbraid=0AAAAA-ddO9GlKnY1zoAGZcYb8bj_Vhnm5 (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Phan, Peter C., and Jonathan Y. Tan. 2013. Interreligious Majority-Minority Dynamics. In Understanding Interreligious Relations. Edited by David Cheetham, Douglas Pratt and David Thomas. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 218–40. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, Peter. 2018. Giants: The Global Power Elite. New York: Seven Stories Press. [Google Scholar]

- Predelli, Line, Beatrice Halsaa, Adriana Sandu, Cecilie Thun, and Line Nyhagen. 2012. Majority-Minority Relations in Contemporary Women’s Movements: Strategic Sisterhood. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Qasmi, Ali Usman. 2015. The Ahmadis and the Politics of Religious Exclusion in Pakistan. London: Anthem Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ramadhan, Gilang. 2022. Majority religious politics: The struggle for religious rights of minorities in Sampang, Madura. Simulacra 5: 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redekop, C., and John A. Hostetler. 1966. Minority-majority relations and economic interdependence. Phylon (1960-) 27: 367–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roemer, J. E., and John Roemer. 1978. Differentially exploited labor: A Marxian theory of discrimination. Review of Radical Political Economics 10: 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roucek, Joseph S. 1956. Minority-Majority Relations in Their Power Aspects. Phylon (1940–1956) 17: 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkissian, Ani, Jonathan Fox, and Yasemin Akbaba. 2011. Culture vs. rational choice: Assessing the causes of religious discrimination in Muslim states. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 17: 423–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermerhorn, R. A. 1972. Ethnicity in the perspective of the sociology of knowledge. Ethnicity I: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J. Irving E. 1961. Minorities and social conflict. Teachers College Record 63: 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Hassan Bin Usman, Farah Rashid, Iffat Atif, Muhammad Zafar Hydrie, Muhammad Waleed Bin Fawad, Hafiz Zeeshan Muzaffar, Abdul Rehman, Sohail Anjum, Muhammad Bin Mehroz, and Ahmed Hassan. 2018. Challenges faced by marginalized communities such as transgenders in Pakistan. The Pan African Medical Journal 30: 96. [Google Scholar]

- Small, Jenny. L., and Nicholas A. Bowman. 2011. Religious commitment, skepticism, and struggle among US college students: The impact of majority/minority religious affiliation and institutional type. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 50: 154–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Anthony D. 1986. The Ethnic Origins of Nations. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Staerklé, Christian, Jim Sidanius, Eva G. Green, and Ludwin E. Molina. 2010. Ethnic minority-majority asymmetry in national attitudes around the world: A multilevel analysis. Political Psychology 31: 491–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, Huma, and Iffat Tahira. 2016. Freedom of Religion and Status of Religious Minorities in Pakistan. International Journal of Management Sciences and Business Research 5: 12. [Google Scholar]

- Tahir, Zulqarnian. 2021. Punjab Assembly and Religious Minorities. Available online: https://sappk.org/wp-content/uploads/publications/eng_publications/Punjab_Assembly_and_Religious_Minorities.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Thapar-Björkert, Suruchi, Lotta Samelius, and Gurchathen S. Sanghera. 2016. Exploring symbolic violence in the everyday: Misrecognition, condescension, consent and complicity. Feminist Review 112: 144–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorat, Sukhadeo, and Katherine S. Neuman. 2012. Blocked by Caste: Economic Discrimination in Modern India. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vrousalis, Nicholas. 2013. Exploitation, vulnerability, and social domination. Philosophy & Public Affairs 41: 131–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagley, Charles, and Marvin Harris. 1958. Minorities in the New World. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Waters, Tony, and Dagmar Waters. 2016. Are the terms “socio-economic status” and “class status” a warped form of reasoning for Max Weber? Palgrave Communications 2: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, Megan. 2018. Little room for capacitation: Rethinking Bourdieu on pedagogy as symbolic violence. British Journal of Sociology of Education 39: 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, Max. 1946. The “rationalization” of education and training. In From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology. Edited by H. H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 240–44. [Google Scholar]

- Wellman, James K., and Kyoko Tokuno. 2004. Is Religious Violence Inevitable. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 43: 291–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, Melissa J., Patricia Tevington, and Wensong Shen. 2018. Religious inequality in America. Social Inclusion 6: 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, Melissa J., Tevington D. Huttenlocher, and Elena G. van Stee. 2025. Religious Inequality in America: The View from 1916. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 64: 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkes, Rima, and Cary Wu. 2018. Ethnicity, democracy, trust: A majority-minority approach. Social Forces 97: 465–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, Louis. 1945. The Problem of Minority Groups. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Company Incorporated. [Google Scholar]

- Zainab, Safia, Zahid Zulfiqar, Kamran Ishfaq, and Iqbal Shah. 2021. Socio-Cultural Issues of Religious Minorities in Southern Punjab, Pakistan. Journal of Languages, Culture and Civilization 3: 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).