A Model of Spaces and Access in the Construction of Asian and Asian American Identities: “Blood Only Takes You So Far”

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review of the Literature

2.1. Race in the U.S.

2.2. Asians in the U.S.

2.3. Asian Identity Development

2.4. The Case for Identity Construction

2.5. Minority-Serving Institutions

2.6. Theoretical Positioning of Study Terminology

3. Theoretical Framework

Researcher Positionality

4. Methods

4.1. IRB

4.2. Participant Recruitment

4.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Self-identify as Asian or Asian American

- Immigrated to the US prior to applying and enrolling at one of the HSIs of interest

- Currently enrolled undergraduate and graduate students or those who graduated within a year from the interview

- Had attended the university for and completed at least one full semester

- Enrolled and completed at least one full face-to-face semester course

- At least 18 and one day at the time of the interview

4.2.2. Recruitment Procedures

4.2.3. Informed Consent Process

4.2.4. Participants

4.3. Setting and Environment

4.3.1. Desert Basin University

4.3.2. University of the South, Veridian Mesa

4.4. Data Collection

Tell me about your experiences as an Asian American student attending DBSU/UVM. I’d like to hear your story in your own words and, should the need arise, I will ask additional questions for clarification or elaboration.

- What does it mean to be Asian/Asian American to you?

- Tell me about experiences serving as the “spokesperson” of the Asian community or of instances where you might have felt tokenized (defined for participants)

- Tell me about your peer groups

4.4.1. Institutional Data

4.4.2. Data Management

4.5. Data Analysis

5. Findings

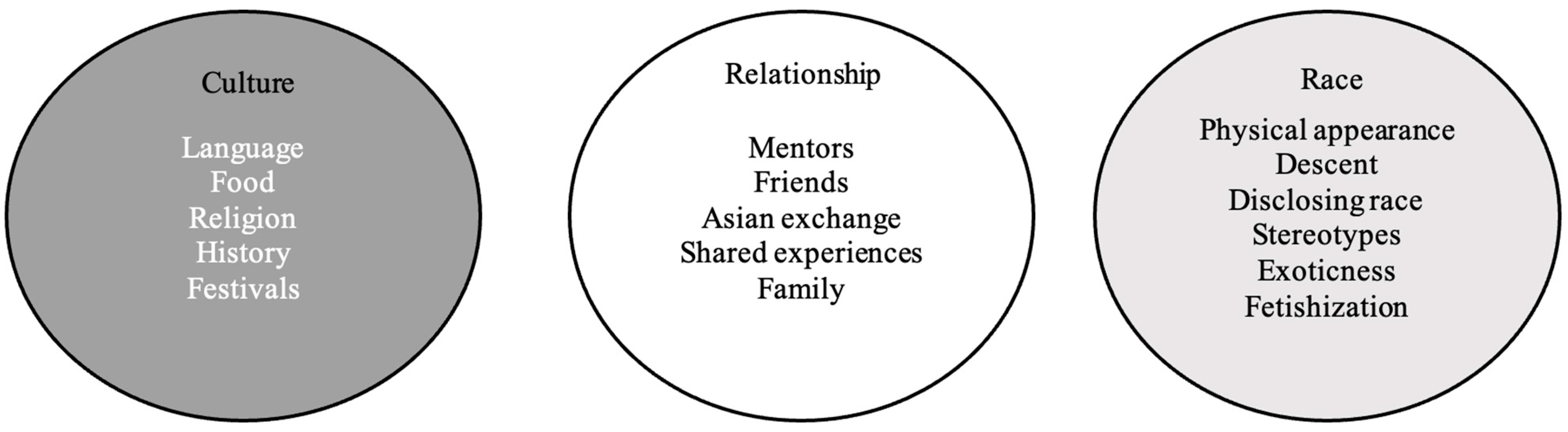

5.1. Overview of the Access to Asian Identity Spaces Model

5.2. “Mythical Scripts”

That made me like wonder, whether I was Asian enough. Cause I don’t do well in school. Like I’m a slacker, procrastinator. And people always made comments that like I wasn’t smart enough to be Asian and stuff.

One summer I went to a teaching academy lecture and a humanities professor who was there, greeted me in Mandarin. I’d never met him before. He didn’t know me, I didn’t know him and he just kind of saw me, then greeted me in Mandarin.

Traveling was extremely difficult, at special screenings just based on your name, you had a special code. You had to go and then they dump your underwear and they would do it whatever! They just dumped your stuff. You did not have that dignity, your body, was—you know, we were nothing. It was robbed. It was a certain kind of pathologizing to a degree. And it’s like you were not only diseased but you were deadly.

I was feeling kind of shocked from that and a little bit upset that they did that? And they used that as like justification for why I called her out on her comment about Japanese people? And then on the other hand—like I was like “Ok, this, is a moment for me to educate” and be like, “Hey yes I am half Chinese I don’t think you should be asking people you think are Chinese if they’re Chinese or hello, in Mandarin cause that’s a little racist.”

Sometimes I feel like if in the social context like if I’m with other Asians that I don’t’ really know, I’m like well, I don’t want to like feel too much like an outsider, and I don’t want them to feel uncomfortable. I’ll be like, “My mom’s Chinese,” just so like you know I don’t feel like an outsider, they don’t feel uncomfortable.

5.3. “Culture Wise I’m Nothing Like It”

I am Asian American in appearance, but culture wise, I’m nothing I would say like it. Because the fact that I just never had that opportunity to really, deeply connect with it. So for me when I think of Asian American, I think of the people who actually do have like actual family, and roots in the respective cultures that they’re from. That they have the traditions that’s been passed down.

They can you know reject it ‘cause you know sometimes it’s, it’s not what they want to do anymore. But for me it wasn’t rejecting, it was just I was never introduced to it in the first place. So, I think nowadays when I think of Asian American, I think, of those who actually are, of Asian descent and have that connectivity. For me it’s’ just like, I don’t even know if I would be able to say I’m Asian American because of it. I just say I’m American.

I think about the extremes of like New York city living in Chinatown living in Koreatown, they really hold on to their culture they’re family life is very much similar to what they had when they were living in you know China or Korea and I don’t’ really see that as being Asian American in a sense that like you know the, the integration part is missing. I think the other extreme is like Asian Americans in Hawaii or California where they are fully integrated, fully acculturated and the only thing they hold is you know their blood line and they’re last name maybe, not even their first name. I think it’s like the happy medium, where they are proud of their heritage, they might practice some of it not all of it probably?

I don’t have so much cultural knowledge. I mean I know how to order dim sum and things like that. I think that was one reason why studying abroad in Germany was easier was because I could just float into that society a lot easier than if I had studied abroad I think in like China. That would’ve been much more difficult because there would’ve been a stronger culture shock because I grew up here. And just the concept of, of White identity. I think it’s a little bit easier for mixed people to flow into that. But also, it’s cause I’m phenotyping because I think I look a lot Whiter than I do Asian.

I think that being an Asian American I know language is a part of it, but culture without the language. How much you practice also. I, I mean it’s hard to tease out. Like culture doesn’t exist without the different language base. You know it’s like you could be very Japanese, but don’t speak the language or you could very much understand concepts of being Asian but don’t speak the language.

I was just part of one of the group because it was all different Asians. We all had to speak English anyway, so I didn’t ever feel left out because of that. Because I think there’s a feeling of barriers when you feel like you should have access to language, and you don’t which is what I think a lot of people feel like here if you don’t speak Spanish. There’s that kind of feeling, of that barrier, where you know stuff is happening, but you can’t access it.

My mom didn’t really push the Japanese culture on us. In fact, when I was growing up, the reason I don’t know Japanese is that they refused to speak to Japanese to us when we were kids. Because they didn’t want us to be confused when we went to kindergarten and everybody was speaking English. They thought they were doing something good for us.

I’m very close to my culture. My mom wanted me to be like a very Korean girl so I feel like, I’ve learned, “Oh I am a little more Korean,” but then, I would be like, “Eh no I’m going to be White,” and stuff like that. But I guess the more I look into it the more I’m like, “Ok I feel more in touch with my Korean,” ‘cause honestly that was what I was more exposed to when I was younger and now I am kind of like accepting it and embracing it and I feel like proud to say like, “Oh I am Korean,” I’m not full, but you know what I still am.

5.4. “It’s Helped Me Become More Centered”

It’s helped me kind of become more um centered I would say? Before when I came down here, I didn’t even know how to identify myself other than as American because I had no context to compare myself to. To come down here and have that experience of seeing other Asian adoptees down here as well just maybe like two or three um and actually just being able to like get to know different kinds of um Asian cultures it’s, it’s really helped, honestly like better understand where I come from? As well as just finally start being like ok this is who I am I’ve, I’ve started to accept it

- Rosalind:

- It depends on how someone identifies and it also feels weird cause you’re picking out their features and looking at them, like “Oh that’s why, I want to approach you. “Or like what if they don’t identify as Asian and you’re just like making this assumption or what if like OK, yes, they do, now what?

- Researcher:

- Right, the now what. So where do you go forward with that?

- Rosalind:

- You create a group an Asian student group! And tell them to join. ‘Cause even them coming, like there’s a reason. Like that’s their choice. Versus, when you approach someone, it’s like you’re choosing to talk to them? But they may not choose not to talk back.

Like my needs weren’t met. and it wasn’t even that I was looking for a parallel experience, but just the space to discuss it. and it was like shut down. … cause it’s like you would think that like if someone is confiding in you can talk about like Asian identity and asking like oh how do you identify and just being completely shut down.

5.5. “It’ll Be Super Defining”

It was kind of weird cause I would talk about, like some of my experiences. Or I would say something that was like “Oh yeah I eat with chopsticks with all my meals every day,” and it was like little things like that that I do because I grew up in a Chinese household. But they just found them really funny and like, “Oh you eat with chopsticks! For every meal! Ha ha ha.” It was it was very it was a very weird experience.

So we had this conversation in class. Like the Hispanic students didn’t get it, “Like what’s the big deal?” Because they don’t understand that you know in a lot of Asian culture I mean it’s important. Especially our family name is important and so it’s offensive to me that I have to change to a Western name just to hide myself. Do I defend myself or not, you know, that’s why it’s important that I’m Participant 19, um because it’s a neutral term. But like it was interesting because the Hispanic students in the classroom did not get it. Like what the big deal was.

I had like an internal thing like, “Let me disprove some stereotypes for you.” ‘Cause I don’t like it when they immediately judge me by what they see. ‘Cause you do not know me specifically. So I use that as a conversation starter. I like hearing other people’s perspective about me, so I can correct them. I the question came up as like, “Do you eat dog?” I would frankly say, “Some of the countries they do and in where I grew up some of them did, but that doesn’t mean that I did.” What is it they say in statistics like, correlation does not mean causation. It’s exactly that. That’s why I like disproving myths cause it’s like what you’ve learned and what people have told you sometimes are not, they’re not real.

Like Southwest is considered diverse, but it’s Southwest diverse? Which means we have Native American, Mexican, and White and that’s what our concept of diversity is. Which isn’t bad! But like, I think because of that I’ve always, as I’ve gotten older I’ve been attempting to stretch more into this kind of Asian identity.

The only thing I would say is that in the end, I think my experiences at DBSU have been thus far the most defining in impact -most defining for my racial identity. Because before, I think I’ve had more, I don’t know if this is right, but I had more of an ethnic identity that was like unquestioned. I was like I’m Korean. I was raised by my dad, my grandma, that was very strong and unquestioned within me, but I started questioning and being faced with things more here. So, so I think it’ll be super defining.

5.6. The AAA Identity and HSI Context

In California, being White in my classroom was kind of like being in the minority. There were always like at least 10 Asian students in each class, I guess starting school in elementary school here was good. I think it felt much more different if I had moved when like I was like in high school or like college. I think I would have been way more uncomfortable? But I had gradually got used to it.

I mean right away as an Asian American, at DBSU, you notice you’re like the only one. You’re pretty much the only one where ever you are. You know, um and, and I guess by now, I’m used to that? ‘Cause I’ve been here for 10 years?

I don’t know how college students at other universities know not to say crazy shit like that. Like how do they know that?! Like did somebody tell them? Was that in the orientation? Like whatever they’re doing, DBSU also needs to do? [long pause] And like in an area where there’s a lot less exposure, because Asians are a numeric minority, like maybe there needs to be more sort of deliberate education about like what, what is an ok thing to say and what is problematic if they’re not picking that up from their personal relationships with Asian Americans

Yeah, I think like with my racial identity, it, it’s definitely become stronger. My, my ethnic identity has become stronger. I, I identify more as Korean than I think I did before? Yeah, I think it, it means a lot more to me. Like it’s something that I hold more dearly to me as a result of what I’ve experienced.

I feel like we’re also there when it’s convenient? I feel like Asianness in America is used like as a tool to be like diversity, but also, like oh, what is it called, that uh, positive stereotype?

‘Cause I feel like SWSU really likes pushing, “Oh, we’re a diverse campus, we have international students,” like it, our happy smiling promotional images, with one Asian person, one Black, one Latino person, and a bunch of White people. Like I, that’s kind of how I feel like they use it?

I think they think of us as cash cows. I think they have the general racists perspective of what they think us Asians are then treat all the same as if we’re the same. Exact, you know, cut from the cloth. Dehumanized numbers. You know, um I guess when they hear about Asian Americans and I don’t think they’re thinking about people from the Philippines or people from you know Indonesia, they’re probably thinking about Chinese, if they’re beyond that, maybe they’re thinking about Japanese. maybe they’re thinking about Indian, but they don’t think Indians are always with Asians. So I mean there’s all kinds of those sort of sort of sort of stereotypical I think I mean they don’t think about us its’ just not a thought.

I haven’t had any interactions with the university, like, “Hey Asian Americans,” or like, you know, like representing me. Or, “We want your thoughts!” Something like that. There’s no input output from the university to Asians. So that’s what I think it’s like, you know I can’t put in my two cents if there’s nothing to put it in. So, I don’t see a lot of representation. Cause number one we are underrepresent-underrepresented-especially in this institution! Especially in this institution and especially in the environment we are in? And the region that we are? It’s a Hispanic-serving institution. So I, that’s why I think we’ve become a second thought.

So, I would just say like the lack of support in that [advising] and also just the lack of support just in just in everything? Really? Cause the way that they treat you sometimes on campus is not really nice in some areas. Like they just come up like you come up to them and they’re like, “Oh how are you today,” and then they’re just so nice to every other kid. And it’s like what am I doing to make you just mad at me?

5.7. “Blood Only Takes You So Far”

I mean, nothing’s really changed, if anything I’ve become more solid in the fact that I’m neither American nor Korean, you know. And for a while I tried to always to go towards the American side because you know that’s where all my friends were and that’s that’s where I wanted to be, but I’ve I’ve, I’ve, the older I get the more I realize how important it is to infuse the Korean side of me too, because there’s, if I could take a good from both sides, then… it’s better than just good from one side, right?

So growing up my parents always told me that, like if anybody asks if I’m Chinese or Taiwanese of whatever, I should always just respond and say I’m American? It was something that like my, my dad, especially was very adamant about?

I think he also gets the, impression that like even though we’re American, we’re not always seen as American? Because we’re Asian, people just assume we’re Asian and we’re not like actual, actually American. Right? Like real American.

My mother would tell me you were born to an Indian stomach, you’re Indian. Your blood coursing through your veins, and then I remember the first time I told my mother that her heart was broken and that’s what she said, she’s like, “My heart is broken.” And I said, “You know. It’s. Blood only takes you so far.”

6. Limitations

7. Discussion

Such a position is able to pay attention to spatial and contextual dimensions, treating the issues involved in terms of processes rather than possessive properties of individuals (as in ‘who are you?’ being replaced by ‘what and how have you?’) p. 494.

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Accapadi, Mamta M. 2012. Asian American identity consciousness: A polycultural model. In Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in Higher Education: Research and Perspectives on Identity, Leadership, and Success. Washington, DC: NASPA-Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education, pp. 57–94. [Google Scholar]

- Adichie, Chimamanda N. 2009. The Danger of a Single Story [Video]. TED Conferences. July. Available online: http://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story (accessed on 15 September 2016).

- Anthias, Floya. 2002. Where do I belong? Narrating collective identity and translocational positionality. Ethnicities 2: 491–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkin, Annabelle L., and Hyung Choi Yoo. 2021. Patterns of racial-ethnic socialization in Asian American families: Associations with racial-ethnic identity and social connectedness. Journal of Counseling Psychology 68: 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berzonsky, Michael D. 2011. A social-cognitive perspective on identity construction. In Handbook of Identity Theory and Research. New York: Springer, pp. 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bhopal, Raj. 2004. Glossary of terms relating to ethnicity and race: For reflection and debate. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 58: 441–45. [Google Scholar]

- Blumer, Herbert. 1986. Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo. 1994. Rethinking Racism: Toward a Structural Interpretation. (Center for Research on Social Organization, No. 526). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan. Available online: https://newuniversityinexileconsortium.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Eduardo-Bonilla-Silva-Rethinking-Racism-Toward-a-Structural-Interpretation.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2016).

- Bowen, Glenn A. 2009. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal 9: 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braveman, Paula, and Tyan Parker Dominguez. 2021. Abandon “race.” Focus on racism. Frontiers in Public Health 9: 689462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Mitchell J. 2008. Asian evasion: A recipe for flawed resolutions. Diverse Issues in Higher Education 25: 26. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Robert. 2000. Disoriented: Asian Americans, Law, and the Nation-State. New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Robert S. 1993. Toward an Asian American legal scholarship: Critical race theory, post-structuralism, and narrative space. California Law Review 81: 1241–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Robert S. 2013. The Invention of Asian Americans. UC Irvine Law Review 3: 947. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, Kathy. 1990. ‘Discovering’ chronic illness: Using grounded theory. Social Science & Medicine 30: 1161–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. Available online: http://www.sxf.uevora.pt/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Charmaz_2006.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2016).

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2025. Constructing Grounded Theory, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Chickering, Arthur W. 1969. Education and Identity. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, Yiting. 2024. Navigating double marginalization: Narratives of Asian (American) educators teaching and building solidarity. Race Ethnicity and Education, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, Juliette, and Anselm Strauss. 2015. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar, Marcella, and Robin Nicole Johnson-Ahorlu. 2016. Examining the complexity of the campus racial climate at a Hispanic serving community college. Community College Review 44: 135–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desert Basin State University. 2015. Fall 2015 Factbook. Available online: https://oia.nmsu.edu/nmsudata/index.html (accessed on 6 October 2016).

- Desert Basin State University. n.d.a. Department of Campus Activities. Available online: http://upc.nmsu.edu/charter/list.php (accessed on 6 October 2016).

- Desert Basin State University. n.d.b. Our Heritage. Available online: https://www.nmsu.edu/about/heritage.html (accessed on 6 October 2016).

- Feagin, Joe, and Sean Elias. 2013. Rethinking racial formation theory: A systemic racism critique. Ethnic and Racial Studies 36: 931–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearon, James D. 1999. What is Identity (As we Now Use the Word). Unpublished manuscript. Stanford: Department of Political Science, Stanford University. [Google Scholar]

- Gasman, Marybeth, Thai-Huy Nguyen, and Clifton F. Conrad. 2014. Lives intertwined: A primer on the history and emergence of minority serving institutions. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education 8: 120–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, James P. 2000. Identity as an analytical lens for research in education. Review of Research in Education 25: 99–125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Glaser, Barney G. 1978. Theoretical Sensitivity: Advances in the Methodology of Grounded Theory. Mill Valley: Sociology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, Barney G., and Anselm L. Strauss. 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New Brunswick: Aldine Transaction. Available online: http://www.sxf.uevora.pt/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Glaser_1967.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2016).

- Guba, Egon G., and Yvonna S. Lincoln. 1994. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In Handbook of Qualitative Research. Edited by Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, pp. 105–17. [Google Scholar]

- Guess, Theresa J. 2006. The social construction of Whiteness: Racism by intent, racism by consequence. Critical Sociology 32: 649–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammack, Phillip L. 2015. Theoretical foundations of identity. In The Oxford Handbook of Identity Development. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, Peter, and Brian Graham. 2016. The Routledge Research Companion to Heritage and Identity. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Huddy, Leoni. 2001. From social to political identity: A critical examination of social identity theory. Political Psychology 22: 127–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humes, Karen R., Nicholas A. Jones, and Roberto R. Ramirez. 2010. Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, Farah, Hifumi Ohnishi, and Daya S. Sandhu. 1997. Asian American Identity Development: A Culture Specific Model for South Asian Americans. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development 25: 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, Carolyn. 2025. Facts About Asians in the U.S. [Fact Sheet]. Pew Research Center. May 1. Available online: http://www.pewresearch.org/race-and-ethnicity/fact-sheet/asian-americans-in-the-u-s/ (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Jo, Ji-Yeon O. 2004. Neglected voices in the multicultural America: Asian American racial politics and its implication for multicultural education. Multicultural Perspectives 6: 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, Ginelle, and Frances K. Stage. 2014. Minority-Serving Institutions and the education of US underrepresented students. New Directions for Institutional Research 2013: 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Eunyoung, and Diane Shammas. 2019. Understanding transcultural identity: Ethnic identity development of Asian immigrant college students during their first two years at a predominantly White institution. Identity 19: 212–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jean. 1981. Development of Asian American Identity: An Exploratory Study of Japanese American Women. Ph.D. dissertation. Available online: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED216085.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2016).

- Lee, Erika. 2015. The Making of Asian American: A History. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Sharon. 2006. Over-represented and de-minoritized: The racialization of Asian Americans in higher education. InterActions: UCLA Journal of Education and Information 2: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Leshner, Alan I., and Layne A. Scherer. 2021. Mental Health, Substance Use, and Wellbeing in Higher Education: Supporting the Whole Student. Washington, DC: The National Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yao, and Harvey L. Nicholson, Jr. 2021. When “model minorities” become “yellow peril”—Othering and the racialization of Asian Americans in the COVID-19 pandemic. Sociology Compass 15: e12849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maekawa Kodama, Corinne, Marylu K. McEwen, Christopher T. H. Liang, and Sunny Lee. 2002. An Asian American perspective on psychosocial student development theory. New Directions for Student Services 2002: 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, Douglas S. 2007. Categorically Unequal: The American Stratification System. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- McLean, Kate C., and Moin Syed. 2015. Personal, master, and alternative narratives: An integrative framework for understanding identity development in context. Human Development 58: 318–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morning, Ann. 2011. The Nature of Race: How Scientists Think and Teach About Human Difference. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morning, Ann, and Marcello Maneri. 2022. An Ugly Word: Rethinking Race in Italy and the United States. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Museus, Samuel D. 2014. Asian American students in higher education. In Key Issues on Diverse College Students. Edited by M. Gasman and N. Bowman III. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Museus, Sameul D. 2022. Relative racialization and Asian American college student activism. Harvard Educational Review 92: 182–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Museus, Samuel, Dina C. Maramba, and Robert T. Teranishi, eds. 2013. The Misrepresented Minority: New Insights on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and the Implications for Higher Education. Sterling: Stylus Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Nadal, Kevin L. 2004. Pilipino American Identity Development Model. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development 32: 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of Management and Budget. 2024. Revisions to OMB’s Statistical Policy Directive No. 15: Standards for maintaining, collecting, and presenting federal data on race and ethnicity. Federal Register Notices 89: 22181–95. Available online: http://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2024-03-29/pdf/2024-06469.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Omi, Michael, and Howard Winant. 2015. Racial Formation in the United States. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development [OECD]. 2010. Higher Education in Regional and City Development: The Paso del Norte Region, Mexico, and the United States. Paris: OECD Publishing. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/mexico/45820961.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2017).

- Pak, Yoon K., Dina C. Maramba, and Xavier J. Hernandez. 2014. Asian Americans in Higher Education: Charting New Realities. ASHE Higher Education Report Series; San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, vol. 40, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, Lori D., Kristen A. Renn, Florence M. Guido, and Stephen J. Quaye. 2016. Student Development in College. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Pedraza, Chadrhyn A. A. 2023. “There’s Something There in That Hyphen”: The Lived Experiences of Asian and Asian American Higher Education Students in the Southwest Borderlands of the United States. Genealogy 7: 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, William. 1966. Success story, Japanese American style. New York Times Magazine, January 9. Available online: http://www.elegantbrain.com/edu4/classes/readings/depository/A_A_S_reads/petersen_modelminority.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2015).

- Pew Research Center. 2020. What the Census Calls Us [Chart]. Pew Research Center. Available online: http://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/feature/what-census-calls-us/ (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Pierce, Jennifer L. 2014. Why teaching about race as a social construct still matters. Sociological Forum 29: 259–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzolato, Jane E., Tu-Lien K. Nguyen, Marc P. Johnston, and Prema Chaudhari. 2013. Naming our identity: Diverse understandings of Asian Americanness and student development research. In The Misrepresented Minority: New Insights on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and the Implications for Higher Education. Edited by Samuel D. Museus, Dina C. Maramba, Marc P. Johnston and Robert T. Teranishi. Sterling: Stylus Publishing LLC., pp. 124–39. [Google Scholar]

- Poon, OiYan, Dian Squire, Corinne Kodama, Ajani Byrd, Jason Chan, Lester Manzano, Sara Furr, and Devita Bishundat. 2016. A critical review of the model minority myth in selected literature on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in higher education. Review of Educational Research 86: 469–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, John A. 1997. The racing of American society: Race functioning as a verb before signifying as a noun. Law & Inequality 15: 99–138. [Google Scholar]

- Ravitch, Sharon M., and Nichole M. Carl. 2016. Qualitative Research: Bridging the Conceptual, Theoretical, and Methodological. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, Victor. 2019. A theory of racialized organizations. American Sociological Review 84: 26–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renn, Kristen A., and Robert D. Reason. 2013. College Students in the United States: Characteristics, Experiences, and Outcomes. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Ryoo, Jean J., and Rob Ho. 2013. Living the legacy of ’68. In The Misrepresented Minority: New Insights on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and the Implications for Higher Education. Edited by Samuel D. Museus, Dina C. Maramba and Robert T. Teranishi. Sterling: Stylus Publishing LLC., pp. 213–26. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago, Deborah A. 2006. Inventing Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs): The Basics. Available online: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED506052.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2016).

- Smedley, A. 1999. “Race” and the construction of human identity. American Anthropologist 100: 690–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedley, Audrey, and Brian D. Smedley. 2005. Race as biology is fiction, racism as a social problem is real: Anthropological and historical perspectives on the social construction of race. American Psychologist 60: 16–26. Available online: http://rws200jspencer.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/104349117/Race%20as%20Biology%20Is%20Fiction.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2014). [CrossRef]

- Song, Miri. 2017. Why we still need to talk about race. In Why Do We Still Talk About Race? London: Routledge, pp. 135–49. [Google Scholar]

- Stryker, Sheldon, and Peter J. Burke. 2000. The past, present, and future of an identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly 63: 284–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suddaby, Roy. 2006. From the editors: What grounded theory is not. Academy of Management Journal 49: 633–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaki, Ronald. 1989. A History of Asian Americans: Strangers from a Different Shore. Boston: Back Bay Books. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Paul. 2013. The Rise of Asian Americans. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online: http://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2013/04/Asian-Americans-new-full-report-04-2013.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2016).

- The White House, Office of the Secretary Press Secretary. 2015. Fact Sheet: Asian American and Native American Pacific Islander Serving Institutions (AANAPISIs). May 12. Available online: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2015/05/12/fact-sheet-white-house-summit-asian-americans-and-pacific-islanders (accessed on 20 December 2016).

- University of the South, Veridian Mesa. 2015. The University of the South, Veridian Mesa 2014–2015 Fact Book. Available online: http://cierp2.utep.edu/pastfactbooks/UTEP%20Fact%20Book%202014-15.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2016).

- University of the South, Veridian Mesa. n.d.a. Asian Studies. Available online: http://academics.utep.edu/Default.aspx?alias=academics.utep.edu/asianstudies (accessed on 6 October 2016).

- University of the South, Veridian Mesa. n.d.b. Organizations Directory. Available online: http://minetracker.utep.edu/organizations (accessed on 6 October 2016).

- University of the South, Veridian Mesa. n.d.c. USVM History. Available online: http://libguides.utep.edu/utephistory (accessed on 6 October 2016).

- University of the South, Veridian Mesa. n.d.d. Vision, Mission, and Goals. Available online: https://www.utep.edu/about/utep-vision-mission-and-goals.html (accessed on 6 October 2016).

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2000. Factfinder for the Nation: History and Organization; Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. Available online: http://www.census.gov/prod/2000pubs/cff-4.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2017).

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2017. Quickfacts: Sun Valley County and Passage City County. Available online: http://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/elpasocountytexas,doaanacountynewmexico,elpasocitytexas,NM/PST045217 (accessed on 5 January 2017).

- U.S. Census Bureau. n.d.a. 1790. Overview. Available online: http://www.census.gov/history/www/through_the_decades/overview/1790.html (accessed on 5 January 2017).

- U.S. Census Bureau. n.d.b. 1800. Overview. Available online: http://www.census.gov/history/www/through_the_decades/overview/1800.html (accessed on 5 January 2017).

- U.S. Census Bureau. n.d.c. 1850. Overview. Available online: http://www.census.gov/history/www/through_the_decades/overview/1850.html (accessed on 5 January 2017).

- U.S. Census Bureau. n.d.d. 1870. Overview. Available online: http://www.census.gov/history/www/through_the_decades/overview/1870.html (accessed on 5 January 2017).

- U.S. Census Bureau. n.d.e. 1890. Overview. Available online: http://www.census.gov/history/www/through_the_decades/overview/1890.html (accessed on 5 January 2017).

- U.S. Department of Education. n.d. Developing Hispanic-Serving Institutions program—Title V: Definition of Hispanic-Serving Institution. Available online: https://www.ed.gov/grants-and-programs/grants-special-populations/grants-hispanic-students/developing-hispanic-serving-institutions-program-title-v#eligibility (accessed on 20 December 2016).

- U.S. News and World Report. 1966. Success Story of one Minority Group in U.S. December 2. Available online: https://teaach.education.illinois.edu/docs/teaachcollegeofeducationlibraries/default-document-library/george-takei.pdf?sfvrsn=f385a5e2_1 (accessed on 10 November 2015).

- Vignoles, Vivian L., Seth J. Schwartz, and Koen Luyckx. 2011. Introduction: Toward an integrative view of identity. In Handbook of Identity Theory and Research. Edited by Seth J. Schwartz, Koen Luyckx and Vivian L. Vignoles. New York: Springer, pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wallinger-Schorn, Brigitte. 2011. Cultural Hybridity. Cross/Cultures 143: 29. [Google Scholar]

- Wijeyesinghe, Charmaine L., and Bailey W. Jackson III, eds. 2012. New Perspectives on Racial Identity Development: Integrating Emerging Frameworks. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Alina. 2013. Racial identity construction among Chinese American and Filipino American undergraduates. In The Misrepresented Minority: New Insights on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and the Implications for Higher Education. Edited by Samuel D. Museus, Dina C. Maramba and Robert T. Teranishi. Sterling: Stylus Publishing LLC., Chapter 4. pp. 86–105. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Frank H. 2002. Yellow: Race in America Beyond Black and White. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Yip, Tiffany, Charissa S. Cheah, Lisa Kiang, and Gordon C. N. Hall. 2021. Rendered invisible: Are Asian Americans a model or a marginalized minority? American Psychologist 76: 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Yan, and Barbara Wildemuth. 2009. Unstructured interview. In Applications of Social Research Methods to Questions in Information and Library Science. Edited by Barbara Wildemuth. Westport: Libraries Unlimited, pp. 222–31. [Google Scholar]

| Pseudonym | Self-Reported Racial Identity | Class Status | Gender | Age Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brittany | Japanese | Masters | Female | 26–30 |

| Camille | Taiwanese | Doctoral | Female | 21–25 |

| Daniel | Korean/White mixed | Masters | Male | 21–25 |

| Dave | Filipino | Junior | Male | 18–20 |

| Davika | Thai | Junior | Female | 18–20 |

| Dustin | Vietnamese | Masters | Male | 26–30 |

| Erika | Japanese American * | Senior | Female | 36–40 |

| Geeta | Indian | Doctoral | Female | 36–40 |

| Grace | Korean American | Doctoral | Female | 31–35 |

| Jason | Chinese | Senior | Male | 21–25 |

| Jesse | Chinese * | Senior | Prefer not to respond | 21–25 |

| Ji-a | Korean | Doctoral | Female | 36–40 |

| Lana | Vietnamese | Junior | Female | 21–25 |

| Lea | Filipino | Masters | Female | 21–25 |

| Maggie | Chinese * | Masters | Female | 26–30 |

| Margaret | Korean | Senior | Female | 21–25 |

| Maya | Korean and Japanese American | Doctoral | Female | 46–50 |

| Michelle | Chinese | Senior | Female | 21–25 |

| Naomi | African American/Japanese | Senior | Female | 21–25 |

| Olivia | Korean * | Junior | Female | 21–25 |

| Participant 19 | Japanese | Doctoral | Male | 36–40 |

| Rosalind | Chinese | Doctoral | Female | 26–30 |

| Russell | Happa | Doctoral | Male | 36–40 |

| Seo-ah | Korean | Masters | Female | 21–25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pedraza, C.A.A. A Model of Spaces and Access in the Construction of Asian and Asian American Identities: “Blood Only Takes You So Far”. Genealogy 2025, 9, 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy9040141

Pedraza CAA. A Model of Spaces and Access in the Construction of Asian and Asian American Identities: “Blood Only Takes You So Far”. Genealogy. 2025; 9(4):141. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy9040141

Chicago/Turabian StylePedraza, Chadrhyn A. A. 2025. "A Model of Spaces and Access in the Construction of Asian and Asian American Identities: “Blood Only Takes You So Far”" Genealogy 9, no. 4: 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy9040141

APA StylePedraza, C. A. A. (2025). A Model of Spaces and Access in the Construction of Asian and Asian American Identities: “Blood Only Takes You So Far”. Genealogy, 9(4), 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy9040141