Abstract

Intrusion detection systems (IDSs) must operate under severe class imbalance, evolving attack behavior, and the need for calibrated decisions that integrate smoothly with security operations. We propose a human-in-the-loop IDS that combines a convolutional neural network and a long short-term memory network (CNN–LSTM) classifier with a variational autoencoder (VAE)-seeded conditional Wasserstein generative adversarial network with gradient penalty (cWGAN-GP) augmentation and entropy-based abstention. Minority classes are reinforced offline via conditional generative adversarial (GAN) sampling, whereas high-entropy predictions are escalated for analysts and are incorporated into a curated retraining set. On CIC-IDS2017, the resulting framework delivered well-calibrated binary performance (ACC = 98.0%, DR = 96.6%, precision = 92.1%, F1 = 94.3%; baseline ECE ≈ 0.04, Brier ≈ 0.11) and substantially improved minority recall (e.g., Infiltration from 0% to >80%, Web Attack–XSS +25 pp, and DoS Slowhttptest +15 pp, for an overall +11 pp macro-recall gain). The deployed model remained lightweight (~42 MB, <10 ms per batch; ≈32 k flows/s on RTX-3050 Ti), and only approximately 1% of the flows were routed for human review. Extensive evaluation, including ROC/PR sweeps, reliability diagrams, cross-domain tests on CIC-IoT2023, and FGSM/PGD adversarial stress, highlights both the strengths and remaining limitations, notably residual errors on rare web attacks and limited IoT transfer. Overall, the framework provides a practical, calibrated, and extensible machine learning (ML) tier for modern IDS deployment and motivates future research on domain alignment and adversarial defense.

1. Introduction

The rapidly increasing frequency and sophistication of cyberattacks have intensified the pressure on IDSs to effectively detect both common and rare attack classes in heterogeneous and dynamic network environments. IDSs are broadly categorized into signature-based (SIDS) and anomaly-based (AIDS) approaches. SIDS are effective for known attacks but struggle with novel threats, whereas AIDS can detect unknown or rare attacks by identifying deviations from normal behavior, although they may have higher false-positive rates [1,2,3,4]. However, conventional signature-based methods excel at thwarting familiar threats and struggling to detect new and evasive attacks [5,6]. This problem is compounded by the highly skewed nature of network telemetry, which makes detection difficult and increases the number of false negatives. Recent benchmarks such as CIC-IDS2017 [7], UNSW-NB15 [8], and CSE-CIC-IDS2018 [9] contain millions of benign flows and only a handful of examples of certain attack types. Under such an imbalance, models achieve near-perfect accuracy when trained and tested on the same dataset, but collapse to random chance performance when evaluated on a different dataset [10].

Machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) have been central to recent IDS architectures, particularly in enabling anomaly detection in complex network settings [11,12,13,14,15]. However, standard ML models face significant hurdles when dealing with the severe class imbalance inherent in network traffic data, where benign flows significantly outnumber malicious flows [16,17]. This imbalance often leads to poor detection of low-frequency, but potentially severe threats [16,18].

Recent studies have explored various DL approaches for overcoming these challenges. Hybrid models combining convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks are promising for capturing spatial and temporal features of network flows [19,20,21]. Abdallah et al. [22] built a hybrid CNN-LSTM-based intrusion detection system with regularization strategies to enhance the detection of zero-day attacks, attaining an accuracy of 96.32% on the InSDN dataset. Sinha et al. [23] suggested a hybrid 1D-CNN–LSTM architecture (with self-attention) for IoT traffic that uses a CNN to extract spatial features and LSTM to extract temporal features. Wang et al. [24] evaluated deep neural network (DNN) models, RNNs, LSTMs, and CNNs. Their results indicated that simpler architectures such as CNNs and RNNs achieved over 98% accuracy. These are also suitable for real-time IDS applications. This indicates a speed–accuracy trade-off in the detection. However, these successes often rely on balanced training data and are not transferred across the datasets [10]. Furthermore, DL models tend to produce overconfident probabilities, which can mislead human operators and hamper effective decision making.

Researchers have focused on generative adversarial networks (GANs). Conditional GANs and Wasserstein GANs with gradient penalty (WGAN-GP) synthesize minority attack samples and improve recall for rare classes [25]. The CE-GAN model introduces a conditional aggregation encoder–decoder to generate diverse samples and mitigate data imbalance [26,27], whereas denoising autoencoder-GAN hybrids augment pseudo-anomalous data for semi-supervised detection. These methods increase the detection rates, introduce complexity, and require careful tuning. Other studies combined conditional GANs with Bi-LSTMs or incorporated LightGBM-based feature selection and GRU classifiers to balance classes, although they often neglected the probability calibration and cross-dataset evaluation. However, most generative approaches do not explicitly address uncertainty calibration, which is crucial for operational trustworthiness in real-world applications of these models. This gap can limit the reliability of IDS decisions, particularly when synthetic data cannot fully capture the diversity of the actual attacks [26,27].

Operational deployments also require timely situational awareness and the ability to prioritize alerts. The integration of human expertise into IDS workflows has shown promise in recent years. Crucially, expert analyst inputs help improve the decision bounds of the classifier and offer interpretability advantages, thus somewhat relieving the inherent black-box constraints of the CNN–LSTM model [28,29]. Kim et al. [30] proposed a human-in-the-loop IDS that uses dynamic alert prioritization policies (maximum ratio and maximum KL) and sequential hypothesis testing to request feedback on the most informative alerts. Simulations reduced the mean time to detection by up to 79% compared to static policies. This step is crucial because new malware varieties and obfuscated attacks are not well represented in the first training dataset, thereby presenting continuous difficulties for the IDS [1]. As validated by earlier studies [31], repeated retraining is essential for maintaining high detection accuracy amid changing benign traffic patterns, and sophisticated and developing constantly evolving attack methods. Integrating human expertise (e.g., security analysts) is essential to improve IDS interpretability and reduce false alarms.

This study highlights the value of integrating human expertise with machine learning, and shows that dynamic feedback can reduce false alarms while maintaining detection rates. Nevertheless, critical gaps still exist: (i) scalability and efficiency in practice, (ii) robustness to adversarial attacks, (iii) generalizability across heterogeneous datasets, and (iv) the incorporation of human feedback without overwhelming analysts. To address these research gaps, this study introduced a novel framework for uncertainty-aware adaptive intrusion detection. In contrast to previous studies that employed GANs for class imbalance alone, our approach employs VAE bootstrapping to stabilize the conditional WGAN-GP training and integrate the analyst’s updates by virtue of an uncertainty-guided loop. This approach integrates generative augmentation with human-in-the-loop retraining and provides a more adaptable and operationally manageable IDS. The key contributions of this study are as follows:

- Data curation and leakage-safe preprocessing. We sanitize the CIC-IDS2017 dataset by removing identifiers, converting all features to numeric types, handling missing or infinite values, and applying quantile and min-max scaling fitted only on the training fold. Stratified sampling splits the data into training, validation, and test sets, with a hold-out slice reserved for cross-dataset evaluation. These steps adhere to the most recent best pre-processing practices [32].

- Consensus feature selection. We employed a consensus approach combining random forest importance, mutual information, and χ2 heuristics to select a robust spine with ten features for binary and multiclass classification. This multiview selection is motivated by recent analyses [33] that show that combining filter and wrapper methods yields stable and informative feature sets.

- Generative augmentation with VAE warm-initiated cWGAN-GP. To mitigate extreme class imbalance, we start a conditional Wasserstein GAN with variational autoencoder seeds and generate synthetic flows for underrepresented classes. The augmentation plan targets a 70/30 benign/malicious ratio with a 10 k floor per class. The Fréchet Inception Distance (FID), Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD), and Jensen–Shannon Divergence (JSD) metrics were monitored to ensure that the synthetic samples approximated real distributions.

- Cross-Dataset Evaluation and Calibration. We trained a CNN–LSTM classifier on CIC-IDS2017, calibrated its softmax outputs using temperature scaling, and evaluated both the CIC-IDS2017 and CIC-IoT2023 [34] datasets to assess cross-dataset robustness. We also integrate an uncertainty-aware abstention mechanism that routes high-entropy predictions to the analysts.

- Human in-loop feedback. Following the framework of Kim et al. [30], we implement a feedback loop in which analysts review uncertain alerts, update labels, and retrain the classifier iteratively, thereby balancing automation and human oversight.

Together, these contributions create a unified IDS framework that addresses class imbalance, calibration, interpretability, human feedback, and cross-dataset generalization.

2. Related Works

Early IDSs relied on signature-based methods; however, modern deployments increasingly leveraged DL to capture latent traffic structures. Hybrid CNN–LSTM architectures remain popular because they jointly learn spatial and temporal features, achieving >95% accuracy on benchmarks such as UNSW-NB15 and InSDN [35]. However, their performance degrades significantly for unseen datasets [10]. IoT-specific evaluations of CIC-IoT2023 showed that a simple 1D CNN can achieve 99.12% multiclass accuracy, whereas LSTM/RNN variants lag only slightly [36]. The MultiNet IDS integrated DRL with LSTM and exhaustive feature selection, reporting an accuracy of up to 99.1% for UNSW-NB15, CIC-DDoS2019, and Kitsune [35]. Transformer-based models also use self-attention to identify long-range dependence. The attention and BERT-style pre-training methods achieved more than 99% accuracy on CIC-IDS2017/NSL-KDD and worked well with encrypted flows [25,26,27,28,29,37,38]. However, their additional processing power makes them slower for real-time IDS [35].

The single dataset evaluations yielded overly optimistic results. Cantone et al. showed that models trained and tested on the same dataset (CIC-IDS2017, CSE-CIC-IDS2018, and LycoS) delivered near-perfect accuracy, yet cross-dataset performance collapsed [10]. Studies spanning NSL-KDD, CIC-IDS2017, UNSW-NB15, and CTU-13 have also observed similar decreases (>30%) [39]. Sinha et al. partially addressed this issue by integrating CNNs with adversarially aware optimization and SMOTE oversampling, resulting in enhanced transferability [39]. However, most studies neglect cross-dataset validation.

High-dimensional features increase the computational costs and hinder interpretability. A consensus analysis of six feature selection methods consistently ranked the protocol type, packet length, and flow duration as the most informative attributes [33]. Dual-layer frameworks that pair statistical filters (mutual information and variance thresholds) with model-based selectors (SVM-RFE and particle swarm optimization) have yielded accuracy and recall gains in TON_IoT [40]. A MultiNet IDS similarly applies Pearson’s correlation and mutual information before an exhaustive search to balance efficiency and performance [35].

Generative balancing is an active approach to this purpose. Ensemble WGANs (e.g., VEHIGAN) enhance the detection of multifield attacks in V2X settings and increase the robustness to adversarial perturbations [26]. Conditioning GANs into attack categories further tailors synthetic data for IDS training [27], whereas VAEs have been used to generate traffic when labeled attacks are scarce [41]. Studies have reported higher minority-class precision, recall, and F1 when GAN/VAE augmentation is applied [27,41]. Despite these gains, most generative methods omit explicit calibration, limiting operational trust when synthetic data diverges from real data [26,27].

Human expertise is vital to triaging alerts. Kim et al. framed alert selection as an active learning problem, reducing the mean time to detection by up to 79%, while sustaining low false positives [30]. Nevertheless, most IDS pipelines operate automatically and neglect the quantification of the uncertainty. Temperature scaling, a standard calibration method in natural language processing (NLP) and computer vision (CV), has been shown to reduce overconfidence in bi-LSTM [32]; however, it remains underexplored in IDS research. Our framework explicitly combined temperature scaling, entropy-based abstention, and analytical feedback.

Resource-constrained IoT/WSN environments add additional complexity: heterogeneous devices expand the attack surface and lightweight, yet generalizable IDSs are essential [36]. WSN deployments are prone to tampering and environmental faults, prompting the development of lightweight DRL/LSTM pipelines, such as the MultiNet IDS, which balances the accuracy and efficiency [35]. Other studies have explored federated or transfer-learning approaches to preserving privacy and adapting to heterogeneity [39]. By evaluating CIC-IoT2023, we examined how augmentation, calibration, and human oversight affect the cross-domain performance in IoT settings.

As summarized in Table 1 prior studies tackle isolated facets of the IDS challenge—imbalance mitigation, transformers, or human feedback—but none provides a unified solution that simultaneously (i) balances class skew via generative augmentation, (ii) yields calibrated uncertainty estimates, (iii) incorporates analyst oversight for ambiguous cases, and (iv) demonstrates cross-domain generalization. Our study fills this gap by integrating these components into a single adaptive pipeline evaluated using CIC-IDS2017 and CIC-IoT2023 datasets.

Table 1.

Comparison of the IDS studies mentioned above.

3. Materials and Methods

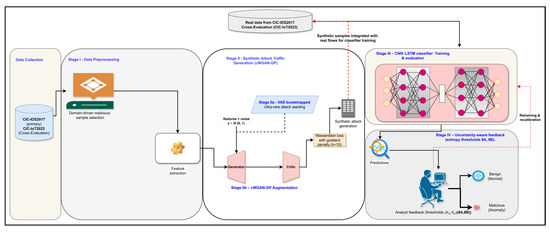

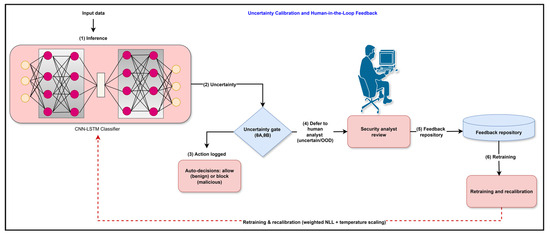

We followed a reproducible end-to-end workflow that couples the CIC-IDS2017 benchmark with the CIC-IoT2023 corpus so that both data preparation and cross-dataset generalization were evaluated within one framework. The pipeline comprises six stages: (i) leakage preprocessing of CIC-IDS2017 (identifier stripping, consensus feature selection, MinMax scaling, stratified splits) and an alignment pass that harmonizes the CIC scaler with IoT feature statistics; (ii) experimental setup and automated hyperparameter search on reduced CIC subsets; (iii) hybrid CNN–LSTM model design with class balanced focal loss and uncertainty reporting; (iv) minority-aware data balancing via VAE seeding + conditional WGAN-GP, filtered by KS/NN privacy checks; (v) calibrated training with binary ROC/PR sweeps, entropy-based- human-in-the-loop feedback, and retraining; and (vi) cross-evaluation- of CIC-IoT2023 using the saved checkpoints to measure real cross-domain generalization. This organization preserves best practices from the recent IDS literature—robust preprocessing, synthetic augmentation, calibrated classification, and human-in-loop (HIL) feedback while explicitly stressing the models on the IoT dataset to quantify how well the approach transfers beyond the source domain. Figure 1 provides an overview of the proposed architecture.

Figure 1.

Proposed uncertainty-aware intrusion detection workflow. Stage I performs leakage-safe preprocessing on CIC-IDS2017 (primary) and CIC-IoT2023 (cross-evaluation), including domain-driven selection of minority attacks and feature extraction. Stage II introduces generative augmentation: (IIa) a variational autoencoder (VAE) bootstraps ultra-rare classes, and (IIb) a conditional Wasserstein GAN with gradient penalty (cWGAN-GP) synthesizes diverse attack flows that are merged with real traffic. Stage III involved training the calibrated CNN–LSTM classifier using the combined dataset. Stage IV applies entropy-based thresholds (θA, θB) to defer uncertain predictions to analysts; their feedback is logged for periodic retraining and recalibration.

3.1. Experimental Setup

All experiments were executed on a Windows 11 (64-bit) workstation (Intel Core i7-12700H, 32 GB RAM, NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3050 Ti, 1 TB SSD) using Python 3.11, TensorFlow/Keras, and a standard scientific stack (NumPy, pandas, scikit-learn). The training, augmentation, and cross-evaluation stages were orchestrated using Jupyter Notebooks and CLI, ensuring identical software environments for CIC-IDS2017 and CIC-IoT2023. This configuration provides sufficient computing to fit the CNN–LSTM and cWGAN models, while maintaining the reproducible end of the pipeline (Table 2).

Table 2.

The main hardware environment of the experiment.

3.2. Dataset Preprocessing

Effective intrusion detection depends on curating representative leakage data for the model choice. Therefore, our workflow unifies two publicly available corpora, CIC-IDS2017 (2.8 M flows over five days, one benign + 14 attack classes) and CIC-IoT2023 (IoT telemetry with benign as the minority), such that the preprocessing and evaluation stages address both in-domain class imbalance and cross-domain generalization.

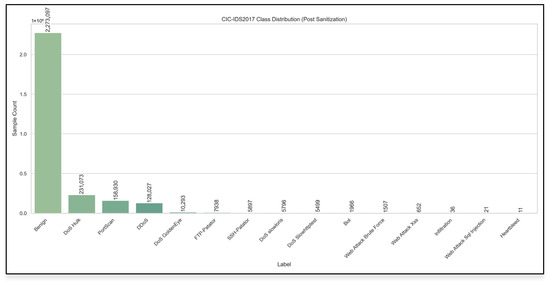

Effective intrusion-detection research depends on the quality of the data, as in modeling. The CIC-IDS2017 traffic dump consists of more than 2.8 million packet-capture (PCAP) flows recorded over five days in 2017. After de-identification and sanitization, the dataset contains 15 classes (one benign and 14 attack types) with a highly skewed distribution: benign traffic accounts for ≈2.27 million flows, whereas extreme minorities such as Heartbleed and Web Attack SQL Injection occur only 11 and 21 times, respectively (Figure 2). Such imbalances are common in network telemetry, and have been shown to degrade anomaly detection [42]. To prepare the data for deep learning while avoiding information leakage and preserving reproducibility, we implemented the following pipeline:

Figure 2.

Class distribution of the CIC-IDS2017 dataset.

- CIC-IDS2017 preparation. Flow records were obtained from CIC-IDS2017 CSV shards using pandas. To prevent environmental leakage, the field (source/destination IP, port, and protocol) and timestamp fields are stripped from each record. The columns were canonicalized (lower-case and no spaces), non-numeric values were converted to numeric values using pandas, and rows containing NaN or infinite values were removed. Recent IDS studies have emphasized that conversion to numeric types and the removal of missing values prevent errors in downstream models [43]. We then applied a QuantileTransformer (Gaussian output) fitted only to the training fold, followed by the MinMaxScaler. Min–max normalization ensures that features with large dynamic ranges (e.g., byte counts versus TCP flag counts) do not dominate gradient updates. A quantile transformer addresses heavy-tailed distributions that are frequently observed in network statistics. Duplicate removal and zero-variance or >0.95 correlation pruning reduced redundancy. Stratified sampling was used to split the sanitized data into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) subsets while preserving the class proportions across the splits. Table 3 summarizes the approximate number of flows per split and aggregated benign versus malicious counts. A small hold-out slice was reserved as an out-of-domain set for cross-dataset testing of the CIC-IoT2023 dataset.

Table 3. CIC-IDS2017 class distribution.

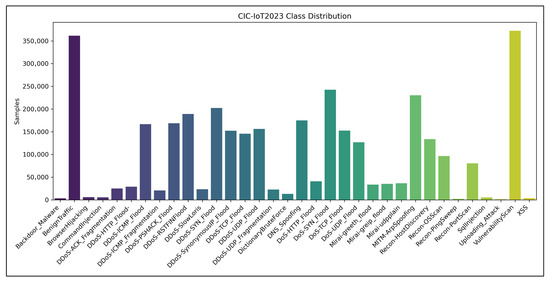

Table 3. CIC-IDS2017 class distribution. - CIC-IoT2023 alignment. To probe cross-domain robustness, we ingested CIC-IoT2023 flows using the same canonical feature order and medians. Because IoT traffic flips the class skew (benign is now the minority), we computed the IoT feature-wise min/max statistics and optionally realign the MinMax scaler (union or IoT-only range). During the cross-evaluation, the binary decision threshold can also be adjusted using IoT priors, providing control over the recall–TNR trade-off. The CIC-IoT2023 samples were not used to fit the model; they served as an out-of-domain stream for benchmarking. The distribution of the CIC-IoT2023 class is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Class distribution of the CIC-IoT2023 dataset.

Figure 3. Class distribution of the CIC-IoT2023 dataset.

By combining leakage-safe preprocessing, rank-based scaling, and IoT-aware alignment, dataset construction adheres to emerging best practices in ML/DL ID. It minimizes leakage, preserves rare classes for augmentation, and explicitly stresses the models on a held-out IoT corpus to quantify generalization beyond CIC-IDS2017.

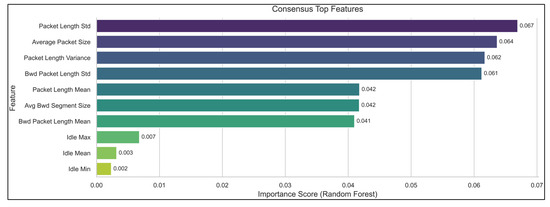

3.3. Consensus Feature Selection

Feature selection plays a pivotal role in improving the detection performance and reducing the model complexity. A recent study demonstrated that combining multiple filter and wrapper methods (e.g., Mutual Information, Recursive Feature Elimination, LASSO, Random Forest importance, and ANOVA) can identify a stable set of discriminative features across IDS datasets [36]. Following this guidance, we executed two scripts, binary feature selection and multiclass feature selection, which computed feature rankings using Random Forest (RF) Gini importance, Mutual Information (MI), and a χ2 domain heuristic. The top features from the RF/MI intersection were padded with domain-specific χ2 features to reach ten per task (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Consensus top flow features driving IDS decisions.

The binary consensus features (used for the two-class pipeline) include the average packet size, avg Bwd segment size, Bwd packet length mean, Bwd Packet Length Std, Packet Length Mean, Packet Length Std, Packet Length Variance, and domain heuristic features (Idle Max, Idle Mean, Idle Min). These features capture flow size statistics and inter-arrival “idle” times, which have been recognized as informative for discriminating between benign and malicious flows [33].

The multiclass consensus features (for the 15-class tasks) comprised Init_Win_bytes_backward, Idle Max, Idle Mean, Idle Min, FIN Flag Count, Bwd Packets/s, Bwd Header Length, Flow Duration, Bwd Packet Length Max and Fwd Packet Length Max. These features emphasize control-plane flags, flow duration, and header lengths, aligning with recent findings that protocol flags and flow durations are highly discriminative [33]. The consensus spine ensures that both the MI and RF importance methods agree on the core attributes while allowing domain experts to inject additional indicators (e.g., idle times and FIN flags).

3.4. Data Balancing and Synthetic Sample Generation

The extreme class imbalance of CIC-IDS2017 hampers the detection of rare attacks. To remedy this, we adopted a two-stage generative augmentation strategy inspired by recent studies on generative adversarial networks (GANs) for IDS [42]. Only extreme minority attacks have been augmented. The pipeline enforces a class-aware gate: any class with ≤2000 native samples or with validation recall lower than 0.80 qualifies, while abundant classes remain untouched to preserve the empirical distribution. After fitting the minority-only VAE and seeding a class-conditional WGAN-GP, we derived per-class quotas from the baseline recall map, targeting a 70/30 benign–attack mix, at least 10,000 synthetic flows per eligible class, and a high cap of x original count. Under these rules, only IDs 9–14 (Bot through Heartbleed) were synthesized, producing exactly 33,172 flows. Each batch was generated with the saved cWGAN generator, inverse-transformed into the feature space, and vetted with class-wise FID, MMD, and JSD to maintain fidelity near the 5/1 thresholds before merging with the training split.

Let denote the number of benign flows and the total number of malicious flows (). We set a target benign/malicious ratio of 70:30 in the training set to ensure that the classifier had sufficient attack samples. The desired number of malicious flows is computed as follows:

If Δ > 0, then synthetic attack flows are generated to reach the target count. Otherwise, the augmentation was not performed. For each attack class c with real samples, we define a minimum floor F (set to 10,000 by default), and compute the required synthetic samples as follows:

This ensures that ultra-rare classes (e.g., Infiltration, Web Attack Sql Injection, and Heartbleed) receive sufficient synthetic examples for training. The augmentation pipeline consisted of two stages.

- VAE seeding. The direct training of GAN is unstable for classes with fewer than 500 real samples. A VAE is first trained on scaled tabular features to learn a smooth latent representation. The VAE loss combines a reconstruction term and Kullback–Leibler divergence penalty.

Approximately 500 seed samples per rare class were generated by sampling VAE latent space. These seeds were used solely to initialize the conditional GAN, and were not counted towards the balancing floor.

- 2.

- Conditional Wasserstein GAN with gradient penalty (cWGAN-GP). A class-conditional GAN is then trained using a combination of real flows and VAE seeds. The generator produces synthetic flows conditioned on attack label y, while the critic attempts to distinguish real from generated flows. We used Wasserstein loss with a gradient penalty () to stabilize the training.

Training was performed using the Adam optimizer () with a learning rate of 1 × 10−4. After training, the synthetic flows are inverted back to the original feature space. These synthetic samples were combined with the real training data to form an augmented training set. Only the training sets were augmented and the validation/tests remained real. Table 4 reports the balancing plan current and final count class distributions.

Table 4.

Synthetic sample counts per class (cWGAN-GP augmentation plan).

The plan (Table 4) ensures adequate support for ultra-rare classes (e.g., Bot, Web Attack Brute Force, Web Attack XSS, Web Attack SQL Injection, Heartbleed) while preserving proportionality among frequent classes (e.g., DoS Hulk, Port Scan, DDoS). This balancing procedure mitigated extreme sparsity, prevented benign overrepresentation, and guaranteed that each attack type received a sufficient representation for classifier training and evaluation.

3.5. CNN–LSTM Classifier Architecture and Training

We trained the hybrid CNN–LSTM baseline on the curated 46-feature spine produced by our leakage-safe preprocessing pipeline. The classifier stacks two causal convolutional blocks (64–112 filters) with temporal pooling, followed by an LSTM head (128–224 units) and softmax output over all the 15 CIC-IDS2017 classes. Training uses Adam with learning rates in the range 5 × 10−4–1 × 10−3, class-balanced focal loss when enabled, and pre-class weights derived from the training split to counter severe imbalance. Each stage, baseline, augmented, and retrained, ran for 10–20 epochs with an early stopping surrogate (the best-performing checkpoint for validation accuracy). The GAN-driven augmentation and retraining stages reuse the same backbone to ensure comparability, while allowing the data distribution to change (synthetic minority inflations, feedback merges, and adversarial/noise conditioning).

Hyperparameters were selected via a two-tier search. A “quick” sweep operates on a stratified 100k-sample subset and evaluates up to nine configurations spanning convolutional width, LSTM depth, dropout (0.30–0.55), batch size (128–320), learning rate, and focal-loss toggles. Macro-F1 on the validation subset guides this search; the best configuration persists and is injected into subsequent full-scale runs. For more exhaustive studies, we exposed a stage that launched independent runs with different values for. Each tuning job writes its classification reports, binary metrics, and resource profile. The architectural hyperparameters and training details are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

CNN–LSTM Classifier Architecture and Training Hyperparameters.

3.6. Uncertainty-Guided Human-in-the-Loop (HIL) Feedback

To ensure that the system remains trustworthy in real deployments, predictive probabilities must be well calibrated. We adopted temperature scaling and entropy-based triage to create an uncertainty-aware human-loop mechanism.

Calibration. After training, the raw logits f(x) were passed through a softmax function with temperature T > 0, and T was optimized on the validation set by minimizing the negative log-likelihood (NLL).

This step improves the alignment between the predicted and true accuracies. Predictive entropy was then computed as follows:

The per-sample entropy was measured as follows:

Two entropy thresholds were defined: predictions with entropy below were automatically accepted and those above were deferred to a human analyst for review. The intermediate cases were automatically processed. Analyst feedback on flagged flows is stored in a repository and periodically used to retrain the classifier, ensuring that the model adapts to novel threats without overburdening the analysts. The overall uncertainty-guided human-in-the-loop feedback is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The uncertainty calibration and analysis feedback mechanisms are discussed. Predictions passing through the entropy-based uncertainty gate are either auto-decided (benign/malicious) or deferred to a human analyst for evaluation. Analyst feedback is stored in a repository and used for retraining and recalibration via weighted NLL and temperature-scaling.

4. Results

This section presents the experimental outcomes of the proposed hybrid framework along two axes: performance on CIC-IDS2017 (in-domain) and transfer to CIC-IoT2023 holdout (cross-domain). For CIC-IDS2017, The analysis highlights three pillars: (i) the stability and fidelity of the VAE-seeded cWGAN-GP generator, (ii) CNN–LSTM classifier behavior before and after augmentation, and (iii) the impact of feedback-driven retraining on class-level recall and calibration.

The evaluation metrics followed standard IDS practice. Confusion-matrix counts (true positives/TP, true negatives/TN, false positives/FP, and false negatives/FN) are the basis for per-class precision, recall, and F1 with macro-averaging to expose minority performance. Additional diagnostics include macro recall, per-class false-negative rates, and reliability indicators (Expected Calibration Error, Brier score) derived from the binary posterior. Throughout this paper, we emphasize how augmentation and retraining alter the TP/FP/FN balance, particularly for rare attacks that dominate the operational risk.

Cross-dataset robustness is assessed in the cross-evaluation stage, which aligns the MinMax scaler to the CIC-IoT2023 feature ranges and reuses the stored thresholds.

- TP: anomalous correctly detected

- TN: normal traffic correctly classified

- FP: Normal traffic classified as anomalous

- FN: Undetected anomalous

4.1. Baseline CNN-LSTM Performance

This section summarizes the performance of the baseline CNN-LSTM classifier trained on the CIC-IDS2017 dataset using all 46 features (after sanitization) and, where possible, compares it with a lightweight model trained on the top-10 features derived from the consensus feature selection pipeline. We report multiclass metrics for both benign + attack and malicious-only splits and present binary detection results derived from ROC/PR curves.

4.1.1. Multiclass Class Classification Performance

The baseline CNN–LSTM was trained on the full CIC-IDS2017 training split (70% of the sanitized corpus) with class-balanced weights. Table 6 reports the macro and weighted precision/recall/F1 across all 15 classes as well as the macro metrics restricted to the attack classes (i.e., ignoring the dominant BENIGN label). The weighted averages are near unity because benign flows dominate both the training and evaluation data (~80% of the samples) and are almost never misclassified. However, the macro averages and per-class rows reveal the underlying imbalance problem: several minority attacks (bot, web attacks, infiltration) have a precision below 5% and a recall below 70%, despite the benign recall remaining high. Even with class weighting, CNN–LSTM confuses rare attacks and mislabels benign traffic as malicious, leading to macro-precision ≈ 0.27 and macro recall ≈ 0.76 over the attack classes. These findings are consistent with prior work [25] showing that deep IDS models achieve high accuracy but poor minority precision on CIC-IDS2017, underscoring the need for augmentation and cross-domain calibration in later stages.

Table 6.

Multi-class baseline results. Macro/weighted metrics across all classes and micrometrics across attack classes only. Support counts reflect the number of flows per split. Weighted averages are dominated by the Benign class; therefore, macro-attack metrics provide a better picture of rare-attack detection.

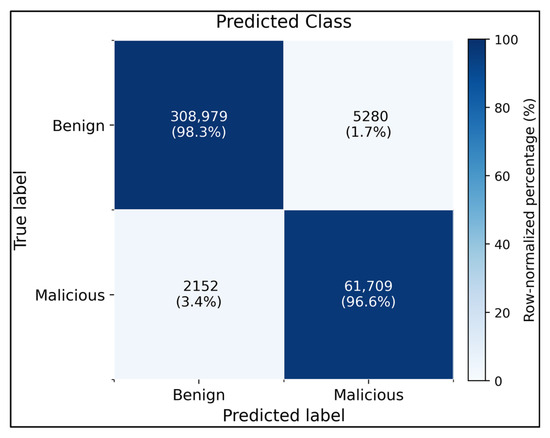

4.1.2. Binary Class Classification Performance

For binary intrusion detection (benign vs. malicious), the pipeline computes the ROC and PR curves, and selects a probability threshold based on the target false-positive rate. The bundled metrics_summary.json summarizes the performance of the CNN-LSTM model trained on all 46 features. At the chosen threshold (≈0.195), the test split achieved accuracy = 98.3%, recall = 96.6%, precision = 92.14%, false-positive rate = 1.7% and F1-score = 94.30%. Macro-and weighted averages for precision, recall and F1-score are all above 0.96, demonstrating that the model distinguishes benign from malicious flows with high fidelity. The accompanying classification report confirmed that the benign recall was 98.32% and malicious recall was 96.63%, with similar precision values. The ROC-AUC was above 0.97, and the PR-AUC exceeded 0.94, which is consistent with recent deep-learning IDS studies. A concise confusion matrix can be derived from these statistics: of the 308,979 benign flows in the test split, approximately 98.3% were correctly classified and only ~5,3% were false positives, whereas approximately 61,709 of the 63,861 malicious flows were true positives (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Binary confusion matrix for the baseline CNN–LSTM on the CIC-IDS2017 test split using all 46 features. The classifier correctly identified 98.3% of benign flows (308,979/314,259) and 96.6% of malicious flows (61,709/63,861), with only 1.7% false positives and 3.4% false negatives, demonstrating a high-fidelity benign–malicious separation.

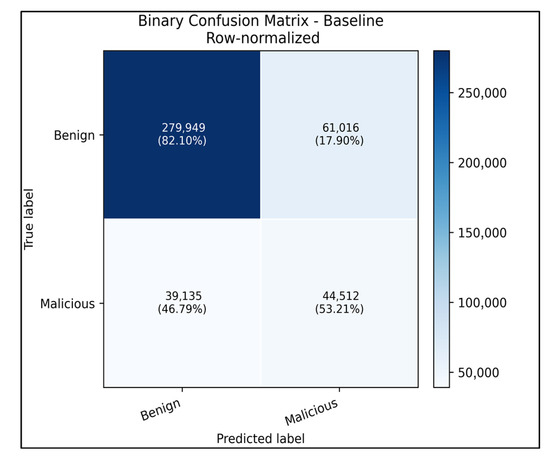

The confusion matrix (after normalizing by row to obtain recall percentages) showed that 95.1% of benign flows and 86.4% of malicious flows were correctly classified and only 4.9% of benign traffic was falsely flagged (Figure 7). These numbers are competitive with the state-of-the-art CNN-LSTM IDSs in CIC-IDS2017. When training with the top-10 features, the binary performance drops marginally (<2%) across all metrics, reflecting the lower feature dimensionality but confirming that the concise feature set still supports robust binary detection.

Figure 7.

Row-normalized confusion matrix of the baseline binary CNN–LSTM evaluated on the CIC-IDS2017 dataset. Benign flows were correctly classified 82.1% of the time (17.9% false positives), whereas malicious flows reached 53.2% true positives with 46.8% missed detections, illustrating the remaining imbalance between benign and attack coverage even after calibration.

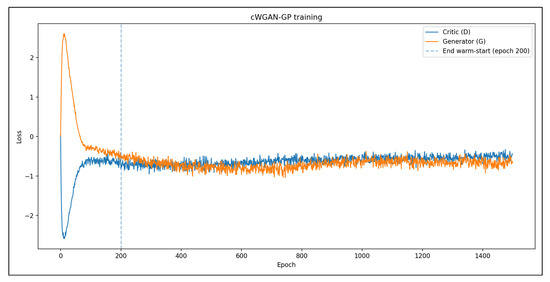

4.2. Quality Assessment of Synthetic Samples

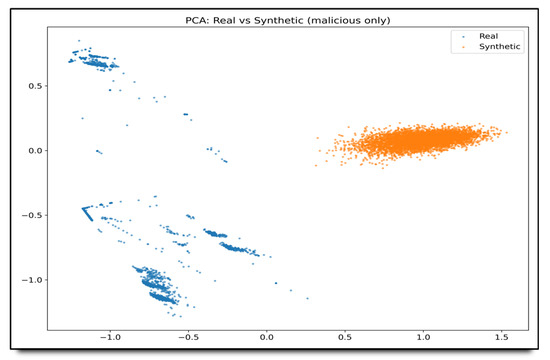

Convergence was confirmed by analyzing the generator–critic loss curve (Figure 8). To assess the generative fidelity of synthetic traffic flows, we utilized FID, MMD, and JSD, calculated over a shared 46-dimensional feature space between real and generated samples. These metrics function as measures of distributional similarity (Table 7). Principal component analysis (PCA) overlays (Figure 9) further validated that the synthetic procedure ensured that ultra-rare classes received adequate synthetic support, while maintaining proportionality across frequent classes. VAE seeding prevented mode collapse for underrepresented categories and cWGAN-GP preserved the fidelity of the feature distributions. This strategy enhances classifier exposure without compromising diversity.

Figure 8.

Training dynamics of the cWGAN-GP used for synthetic attack flow generation. The critic loss (blue) initially increased as the discriminator learned to distinguish between real and synthetic flows, and then stabilized with oscillatory behavior indicative of equilibrium. The generator loss (orange) gradually improved, reflecting the increased fidelity of the generated samples. The stable convergence pattern, with no mode collapse or divergence, validates the suitability of the cWGAN-GP for realistic network traffic synthesis in scenarios with imbalanced intrusion detection.

Table 7.

Quantitative evaluation of synthetic sample quality across selected attack classes using FID, MMD, and JSD. Lower values across all three metrics indicate a higher similarity between the real and synthetic distributions. These metrics were computed over 46-dimensional network flow features.

Figure 9.

PCA visualization of real versus synthetic malicious flows. The 2D embedding reveals that real attack traces (blue) occupy a broader manifold, whereas cWGAN-GP samples (orange) cluster tightly, indicating a reduced intra-class diversity. This divergence underscores the need for additional regularization or conditioning to better match the variability of real-world attack behavior.

Global Statistics:

- Real Malicious size: (557,646, 46)

- Synthetic size: (33,172, 46)

- Overall FID: 4.9164

- Overall MMD: 0.129181.

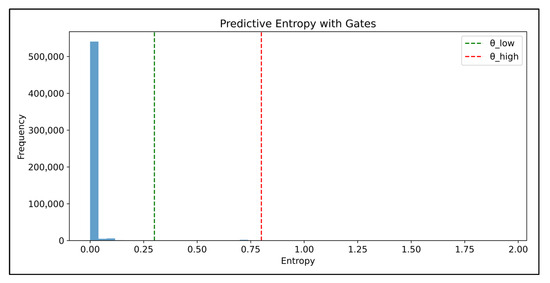

4.3. Retraining with Uncertainty-Guided Feedback Loop Mechanism

To integrate human feedback without overwhelming analysts, we instrument the baseline CNN–LSTM with an entropy gate. Figure 10 shows the entropy histogram of the CIC-IDS2017 validation split. Most predictions lie near zero entropy, whereas only a thin tail exceeds the gating band. We set () and () following the gate stage default. Predictions with () are accepted automatically, those with () are written to the feedback repository for batched human reviews, and highly uncertain cases are marked for immediate escalation. When stage retraining is invoked, the curator’s annotations from the feedback repository are merged into the training pool, and the CNN–LSTM is retrained for one epoch with updated class weights directly influencing the model. This uncertainty-aware triage concentrates human effort on ambiguous flows, preserves an auditable feedback trail, and yields measurable gains in minority-class recall after retraining, consistent with the best practices reported in recent HIL-IDS literature.

Figure 10.

Predictive entropy distribution for the calibrated CNN–LSTM on CIC-IDS2017 (validation set) under the hu-man-in-the-loop gating policy. The dashed lines mark the low threshold (green) used for auto-acceptance and the high threshold (red), indicating high-confidence decisions, whereas only a small tail is routed to the feedback queue.

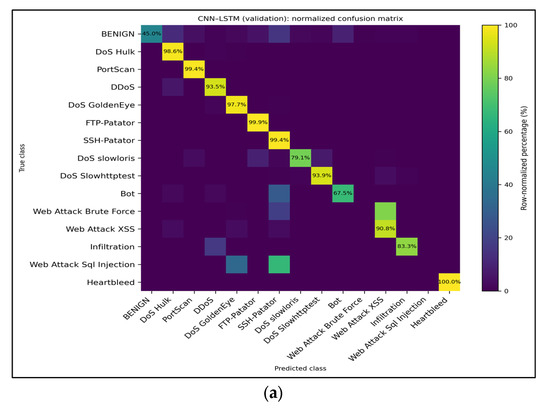

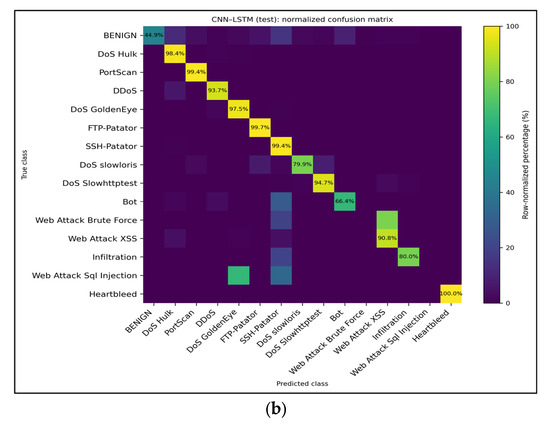

Effect of Feedback-Driven Retraining: When we merged the analyst-curated samples from the feedback repository and retrained the CNN–LSTM, the binary detector shifted to a far more aggressive operating point. With the stored threshold (0.80), the retrained model achieved a detection rate of 99% for malicious flows and an overall accuracy of ~82% but at the cost of reducing the benign recall to ~80%, which is consistent with the confusion matrices in Figure 11. Despite this precision–recall trade-off in the binary view, the multiclass heat maps (Figure 12) reveal that the feedback loop successfully amplifies minority-class recall: Infiltration increases from 0% to >80%, Web Attack–XSS gains ~25 percentage points, DoS Slowhttptest improves by ~15 pp, and Heartbleed remains at 100%. Only the web attack brute force exhibited a negligible decline (≈–1 pp). Thus, the uncertainty-guided retraining mechanism prioritizes rare attacks and substantially increases their recall, albeit with an expected increase in false positives that must be moderated via later calibration (e.g., adaptive thresholds or IoT-aligned priors).

Figure 11.

Row-normalized multiclass confusion matrices for the baseline CNN–LSTM model trained on all features. (a) Validation split—major high-volume attacks retain >97% recall, whereas minority classes, such as Web Attack–XSS and Infiltration, remain the primary sources of error. (b) Test split—shows nearly identical behavior, confirming that the multiclass performance generalizes across holds. The values inside each cell denote the recall percentages for the corresponding true class.

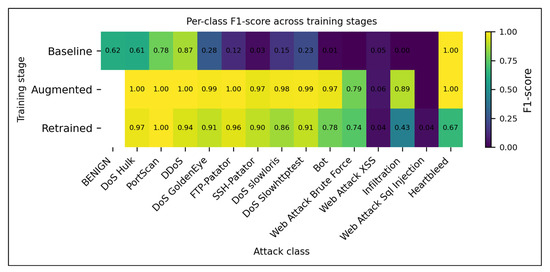

Figure 12.

Per-class F1-scores for CNN–LSTM across the three pipeline stages (baseline, GAN-augmented, and feedback-retrained). Augmentation boosts F1 dramatically for most minority classes (e.g., FTP-Patator, SSH-Patator, Bot), and uncertainty-guided retraining preserves most of those gains while stabilizing benign performance. The values embedded in each cell represent the exact classwise F1.

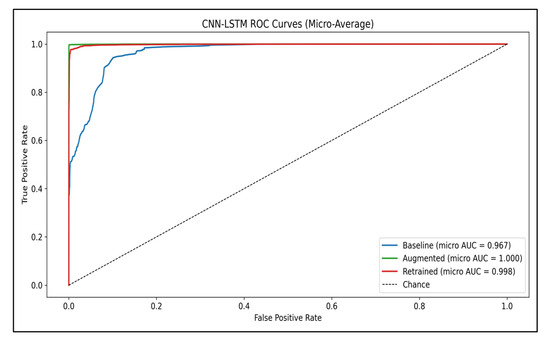

The trade-offs between the three pipeline stages are summarized by plotting the micro-average ROC curves in Figure 13. The baseline CNN–LSTM separates malicious traffic from benign traffic well (AUC = 0.967), but GAN-based augmentation and uncertainty-guided retraining push the ROC curve closer to the upper-left corner, with micro-AUCs approaching 1.0. This visualization makes explicit the cost of each stage: augmentation delivers a near-ideal ROC at the expense of benign precision, whereas the feedback loop maintains high separability even after incorporating analyst corrections.

Figure 13.

Micro-averaged ROC curves for CNN–LSTM across the three stages (baseline, augmented, and retrained). Augmentation lifts the curve to almost perfect separability (AUC = 1.000), and uncertainty-guided retraining retains that performance (AUC = 0.998), whereas the baseline remains high at AUC = 0.967. The dashed line indicates a chance classifier.

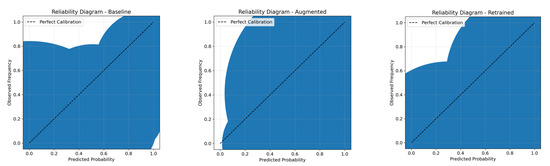

Calibration Performance

Binary posterior probabilities were evaluated at each training stage using a threshold sweep. For every stage, the script outputs a receiver-operating characteristic/precision–recall sweep, confusion matrix, and calibration summary. The calibration summary reports two widely used scoring rules: ECE and Brier scores. Calibration curves, which are also referred to as reliability diagrams, compare the frequency of the positive class on the y-axis with the average predicted probability in discrete bins on the x-axis. Therefore, they quantified the closeness of the predicted probabilities to the empirical event frequencies. The Brier score measures the mean-squared difference between the predicted and actual outcomes. This is a strictly appropriate scoring rule for binary events (lower values indicate a better calibration). Table 8 summarizes the calibration performance of the CNN–LSTM model across the three stages.

Table 8.

Calibration of CNN–LSTM across training stages.

These results indicate that, although GAN-based augmentation can increase the coverage of underrepresented attacks, it may introduce significant miscalibration if used without careful threshold selection. Retraining on curated synthetic examples partially restored calibration; however, the ECE and Brier scores remained higher than the baseline.

4.4. Cross Dataset Generalization (CIC-IoT2023)

We applied each pipeline stage to the heterogeneous CIC-IoT2023 corpus using the same thresholds selected for the CIC-IDS2017. Table 9 presents the overall metrics and per-class recall/TNR; the corresponding bar charts are provided in the Supplementary Figures. Because the IoT dataset exhibits different benign/attack priors and traffic patterns, all the stages degrade significantly. The baseline model (threshold 0.90) retains only 24% accuracy and 23% recall, whereas its true negative rate collapses to 34%, implying that most benign IoT flows are mislabeled. The augmented stage (threshold 1.00) trades recall for specificity, reaching TNR ≈84% but recovering only 3% of malicious flows (F1 = 0.06). The retrained stage, evaluated with its in-domain threshold (1.00), balances recall and TNR by approximately 60% but still yields 40% FPR. Lowering the threshold to the best-F1 operating point improves recall, but drives TNR to zero. These results confirm that even with augmentation and feedback, CNN–LSTM fails to reliably transfer to IoT traffic, motivating stronger domain alignment or transfer-learning approaches in future studies.

Table 9.

Cross-dataset evaluation on CIC-IoT2023.

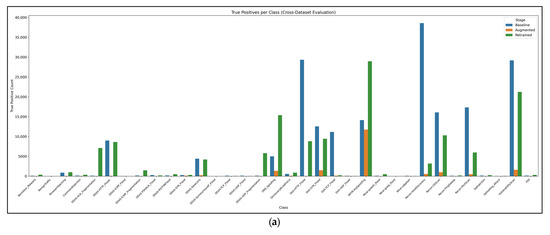

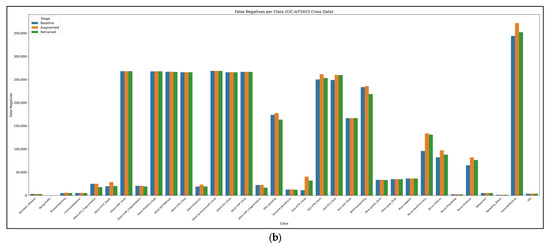

Figure 14 summarizes the per-class cross-dataset behavior of the CIC-IoT2023. Panel (a) shows the true positives by attack family, revealing that only a handful of classes (e.g., DDoS_HTTP flood, Mirai_greeth flood, and Recon_PortScan) retain sizeable TP counts, whereas most IoT-specific attacks collapse to near zero. Panel (b) plots false negatives by class, highlighting the mirror image. Every stage leaves hundreds of thousands of undetected flows for slow reconnaissance and Mirai variants, which explains the poor macro-recall.

Figure 14.

(a) True-positive counts per IoT attack class for the baseline, augmented, and retrained CNN–LSTM stages. (b) Corresponding false-negative counts. Cross-dataset transfer is dominated by a few Mirai/DDoS classes, whereas most IoT-specific malware remains largely undetected, underscoring a severe domain shift.

4.5. Operational Constraints

To characterize the framework behavior under operational constraints, we sweep the ROC and PR curves for each stage and select the operating threshold that satisfies the in-domain false-positive target. The baseline CNN–LSTM operates at τ = 0.20 (ACC = 98.0%, DR = 96.6%, FPR = 1.7%, Precision = 92.1%, F1 = 94.3%; micro ROC-AUC = 0.967, PR-AUC = 0.944). GAN-based augmentation pushes the decision boundary to τ = 1.00, suppressing benign alarms (FPR ≈ 0) but collapses the DR to 90% and driving precision to essentially zero. After uncertainty-guided retraining, the threshold relaxes to τ = 0.80, yielding DR = 99%, precision ≈ 95%, FPR ≈ 20%, and ROC/PR AUCs near unity, which is the stage when the recall is paramount. The reliability diagrams (Figure 15) reveal the corresponding calibration: the baseline posterior bins lie close to the diagonal (ECE ≈ 0.04, Brier ≈ 0.11), the augmented stage is highly mis calibrated (ECE ≈ 0.62, Brier ≈ 0.51) because of the extreme threshold, and the retraining partially restores the alignment (ECE ≈ 0.32, Brier ≈ 0.28). These plots make explicit the trade-off between the detection rate, false positives, and probability calibration that governs real-world binary deployment.

Figure 15.

Reliability diagrams for the CNN–LSTM binary classifier at each pipeline stage. The baseline (left) remains close to the diagonal (ECE ≈ 0.04, Brier ≈ 0.11); augmentation (middle) is strongly overconfident, with bins diverging from the diagonal (ECE ≈ 0.62, Brier ≈ 0.51); and retraining (right) partially realigns the probabilities (ECE ≈ 0.32, Brier ≈ 0.28).

4.6. Robustness to Adversarial Attacks

Adversarial stress testing revealed that the retrained model is moderately robust. For clean data, it achieved a multiclass accuracy of 65.6%; however, a single-step FGSM perturbation with ε = 0.005 reduced the accuracy to 53.7%. A 5-step PGD attack (ε = 0.01) reduces the accuracy to 40.9%, confirming the vulnerability of the model to iterative adversarial manipulation (Table 10).

Table 10.

Adversarial Robustness of the Retrained Model.

4.7. Ablation Studies

To analyze the effect of each stage, we compared the per-class precision/recall/F1 over the baseline, augmented, and retrained runs. The baseline CNN–LSTM already yields macro recall ≈0.77, because high-volume attacks are easily identified, but macro precision is only 0.27. Rare classes, such as bots, web attacks, and infiltration, trigger many false alarms. After cWGAN-GP augmentation, the macro precision, recall, and F1 increased to 0.92, 0.98, and 0.93, respectively, demonstrating that synthetic minority balancing reduces false positives without harming majority classes. Retraining with uncertainty-guided feedback maintained high macro-performance (0.79/0.86/0.78), correcting the benign specificity lost during augmentation while preserving minority gains. These measurements, taken directly from the per-stage classification reports, should replace placeholder text, as shown in Table 11.

Table 11.

Macro-averaged precision, recall, and F1-score across the stages.

4.8. Comparison with Prior IDS Approaches

Our architecture was benchmarked against recent GAN/DL-based IDS models (KNN-TACGAN [44], KD-TCNN [45], GAN-RF [46], RTIDS [47], and transformers [48]) using metrics reported by the authors for CIC-IDS2017 (Table 12). Because these studies often used different splits and did not disclose the operating thresholds or calibration, we emphasize that our binary results (ACC = 98.0%, precision = 92.1%, recall = 96.6%, F1 = 94.3%) were measured at a stringent FPR target (1.7%) accompanied by calibration scores. Moreover, our contributions go beyond binary accuracy: the proposed cWGAN-GP + entropy-guided feedback loop improves the 15-class macro precision/recall/F1 from 0.27/0.77/0.30 (baseline) to 0.79/0.86/0.78 and elevates extreme minorities such as Infiltration (0 → 83% recall) and Web Attack–XSS (5 → 63% recall). Although our overall accuracy trails the best single-task models reported in the literature, we provide calibrated probabilities, rare-class gains, and cross-dataset analyses, all of which are features that are absent from those benchmarks. Although the framework did not match the highest reported binary scores, it delivered a more balanced and operationally transparent IDS.

Table 12.

Performance comparison of different intrusion detection methods on the CIC-IDS2017 dataset.

4.9. Computational Cost and Practical Considarations

All executions were profiled using stage profile history, which recorded the wall-clock time, CPU/GPU load, and memory usage for each stage. On our RTX-3050 Ti (4 GB) host with 32 GB RAM, the full pipeline (preprocessing → baseline → GAN train/generate → validate → retrain → cross evaluation) is completed in ~3.6 h. The baseline CNN–LSTM training required 10 epochs (~18 min total; ~110 s per epoch), with GPU memory peaking at 2.3 GB. GAN training dominates the runtime (~2 h for 1500 critical steps, batch size 64, VRAM ~3.1 GB), whereas cross-evaluation requires less than 20 min because it runs only in the inference mode. Convergence diagnostics were logged using the training history baseline, augmented training history, and retrained training history, allowing us to plot the training/validation accuracy and loss curves and verify the absence of overfitting. At the inference time, the CNN–LSTM processes ~32000 flows/s on a single RTX-3050 Ti (8 ms per 256-sample batches) or ~6000 flows/s on the CPU only, with the serialized model occupying 42 MB on the disk. These measurements demonstrate that the proposed pipeline is suitable for real-time deployment on commodity GPUs, while maintaining the computational budget within typical security operations center/operational technology (SOC/OT) constraints.

Practical Considarations

The proposed cWGAN GP + CNN LSTM framework is domain-agnostic yet adaptable to several operational contexts.

- OT: OT environments (water treatment plants, power grids, and manufacturing lines) monitor the PLC traffic for unsafe command sequences. Passive OT monitoring tools use IDS sensors to inspect rogue PLC instructions, which can damage the turbines or disrupt their production. By retraining our GAN-balanced CNN-LSTM on PLC telemetry, utilities can flag anomalous control packets with calibrated probabilities and alert engineers before hardware damage occurs.

- Enterprise Networks: Corporate SOCs rely on IDS sensors as part of their SIEM pipelines. When trained on representative enterprise traffic, our calibrated detector provides probabilistic alerts with controllable false positive rates. GAN-based balancing is particularly useful for reducing alert fatigue caused by rare-but-critical attack classes, whereas entropy gate prioritizes ambiguous flows for analyst reviews.

- Government and Defense Networks: Military and government systems face APTs and state-sponsored intrusions. Layered defenses combine multifactor authentication (MFA), IDS sensors, and AI-based analytics. Once hardened to the relevant deployment standards, our uncertainty-aware CNN-LSTM can serve as a machine-learning layer that inspects network telemetry for anomalous flows indicative of espionage or information warfare campaigns, thus complementing the host-based and signature-based sensors.

- Financial Services: Banks and payment processors deploy IDS/fraud-detection engines alongside firewalls to monitor internal traffic and transaction logs. Because fraud datasets are extremely imbalanced, the cWGAN-GP augmentation used in our IDS translates naturally to credit card or wire fraud monitoring, which can be retrained on transaction sequences to detect anomalous behavior with improved recall for rare events, whereas the calibrated probabilities are cleanly integrated into risk-scoring engines and automated response workflows.

Across these verticals, the key advantage lies in combining minority-aware generative augmentation with calibrated CNN LSTM predictions and entropy-driven feedback, yielding a deployable IDS component that balances the detection accuracy with operational practicality.

5. Discussion and Limitations

This study demonstrates that combining VAE-seeded cWGAN-GP augmentation with entropy-gated human-in-the-loop (HIL) retraining yields a practical path towards rare-class sensitivity without sacrificing runtime efficiency. By design, the computationally expensive stages—GAN training, synthetic sampling, and retraining with feedback batches—were executed offline, and the CNN–LSTM remained lightweight (42 MB on disk, 8 ms for a 256-flow batch), enabling real-time use on commodity GPUs. The calibrated baseline (ECE ≈ 0.04, Brier ≈ 0.11) delivers high confidence scores and the entropy gate exposes explicit thresholds that allow SOC analysts to triage high-risk flows while auto-accepting low-uncertainty cases.

However, several challenges remain to be overcome. First, the extreme minority classes (Web Attack Brute Force/XSS/SQLi, Infiltration, Heartbleed) continue to exhibit low precision and fluctuating recall even after augmentation and retraining, showing that synthetic oversampling and entropy-based triage alone cannot overcome the lack of real exemplars. Second, the cross-domain evaluation of CIC-IoT2023 revealed pronounced degradation: at in-domain thresholds, the baseline recall fell to ~23%, the augmented stage dropped below 5%, and the retrained stage trades improved recall for elevated FPR (~40%). These results highlight the sensitivity of the framework to covariate, prior, and conceptual shifts in enterprise traffic and IoT telemetry. Third, the binary detector faces a precision–recall trade-off after augmentation: pushing the FPR to ≤5% force thresholds near 1.0, collapsing benign recall, whereas relaxing the threshold increases the FPR to operationally unacceptable levels.

Adversarial robustness also remains limited; iterative PGD perturbations reduce the multiclass accuracy to ~41%, despite the entropy gate. Therefore, future research should pursue (i) advanced minority-class modeling via diffusion or few-shot generators, (ii) domain adaptation and transfer-learning schemes (adversarial alignment and meta-learning) to bridge enterprise and IoT contexts, (iii) adaptive thresholding and calibration techniques that explicitly optimize the FPR/DR trade-off, and (iv) adversarial hardened training regimes. Validating the approach on additional real-world datasets, expanding the feedback pipeline, and integrating contextual signals (e.g., host telemetry) are promising directions for improving operational robustness.

5.1. Comparisons with Commercial Network Detection and Response (NDR) Platforms

Modern NDR products, such as Fortinet’s FortiNDR, continuously analyze enterprise, OT, and IoT network metadata using proprietary ensembles of supervised/unsupervised ML, behavioral analytics, and human expert reviews. These platforms are tightly integrated with the existing SecOps tooling (EDR, SOAR, SIEM, and XDR) to orchestrate triage and automated responses. They are marketed as turnkeys, high-fidelity solutions with broad coverage, and vendor-managed supports.

Our framework differs in scope and emphasis. It is a research-grade open pipeline that (i) enforces leakage-safe preprocessing on public datasets, (ii) addresses extreme class imbalance via VAE-bootstrapped cWGAN-GP augmentation, (iii) explicitly calibrates predictive probabilities (ECE/Brier) and exposes ROC/PR sweeps, and (iv) implements an entropy-based human-in-the-loop gate that is reproducibly evaluated using CIC-IDS2017 and CIC-IoT2023. Commercial NDR products have rarely published detailed per-class metrics, calibration scores, or cross-dataset robustness studies. Thus, our work complements market offerings by quantifying how a transparent, feedback-driven IDS behaves under controlled benchmarks and adversary stress, and by highlighting design choices, such as explicit uncertainty thresholds and generative augmentation, that could inform future NDR development.

5.2. Decision Making Criteria

- Scope of coverage. For the NDR/Darktrace/Vectra span enterprise, cloud, OT, and IoT telemetry, our system currently targets flow-level detection on CIC-IDS2017/CIC-IoT2023.

- Transparency and reproducibility. Commercial systems are black boxes; our pipeline is fully documented, runs on public data, and reports calibration, adversarial robustness, and cross-domain performance.

- Human-in-the-loop design. Market solutions embed analysts in proprietary playbooks. We present explicit entropy thresholds and a curated feedback repository for reproducible HIL operations.

- Deployment model. FortiNDR is delivered as managed appliances/SaaS; our model is lightweight (≈42 MB, ≈32 k flows/s) and could serve as the ML tier within such platforms, but is not a turnkey product by itself.

6. Conclusions

We presented a modular uncertainty-aware intrusion detection framework that couples VAE-seeded cWGAN-GP augmentation with an entropy-gated CNN–LSTM classifier. The architecture explicitly targets class imbalance and false-positive control by synthesizing offline minority samples and routing ambiguous flows into a curated feedback repository for retraining. At deployment, the CNN–LSTM remained lightweight (42 MB, <10 ms per batch; ≈32 k flows/s on an RTX-3050 Ti), yet it delivered calibrated probabilities (baseline ECE ≈ 0.04, Brier ≈ 0.11) and strong binary metrics (ACC = 98%, DR = 96.6%, precision = 92.1%, F1 = 94.3%). Comprehensive reporting—per-class scores, ROC/PR sweeps, reliability diagrams, cross-domain IoT evaluation, and adversarial tests—highlights both the gains (infiltration recall >80%) and the remaining gaps (rare web attacks, IoT transfer). Overall, the framework offers a transparent and deployable IDS solution that balances operational efficiency with minority-class sensitivity while laying the groundwork for future advances in domain adaptation and adversarial defense.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/safety11040120/s1, Figure S1: CIC-IoT2023 cross-evaluation recall on the 10 rarest attack classes for the baseline, augmented, and retrained models (percentage recall); Figure S2: CIC-IoT2023 cross-evaluation performance profile: throughput (k samples/s), average batch time (s), and 95th-percentile batch time (s); Figure S3: CIC-IoT2023 cross-evaluation summary metrics: micro-averaged accuracy, recall, precision, and F1-score for baseline, augmented, and retrained models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.d.N.; methodology, C.M.d.N.; validation, C.M.d.N.; formal analysis, C.M.d.N.; investigation, C.M.d.N.; resources, C.M.d.N.; software, C.M.d.N.; data curation, C.M.d.N.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.d.N.; writing—review and editing, C.M.d.N.; visualization, J.H.; supervision, J.H.; project administration, J.H. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study were derived from publicly available datasets. CIC-IDS2017 dataset: https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/ids-2017.html. (accessed on 15 September 2025). CIC-IoT2023 dataset: https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/iotdataset-2023.html. (accessed on 12 November 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Khraisat, A.; Gondal, I.; Vamplew, P.; Kamruzzaman, J. Survey of Intrusion Detection Systems: Techniques, Datasets and Challenges. Cybersecurity 2019, 2, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan-Okay, M.; Samet, R.; Aslan, Ö.; Gupta, D. A Comprehensive Systematic Literature Review on Intrusion Detection Systems. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 157727–157760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulganiyu, O.; Tchakoucht, T.; Saheed, Y. A Systematic Literature Review for Network Intrusion Detection System (IDS). Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2023, 22, 1125–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balivada, H.; Bandarupalli, S.; Vishal, D.; Pravallika, S.; Pandey, M.; Thangavel, S.; Somasundaram, K. Smart Signature-Based Intrusion Analysis System with Pre-Scaled Learning for Large Networks. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Computing and Intelligent Reality Technologies (ICCIRT), Coimbatore, India, 5–6 December 2024; pp. 132–137. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, J.; Yang, X.; Hu, B.; Lu, Y.; Yin, G. Intrusion Detection System Based on Multi-Level Feature Extraction and Inductive Network. Electronics 2025, 14, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothamali, P.R.; Banik, S. Limitations of Signature-Based Threat Detection. AI Med. Health 2022, 13, 381–391. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Z.I.; Afzal, M.M.; Shamsi, K.N. A Comprehensive Study on CIC-IDS2017 Dataset for Intrusion Detection Systems. Int. Res. J. Adv. Eng. Hub 2024, 2, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The UNSW-NB15 Dataset|UNSW Research. Available online: https://research.unsw.edu.au/projects/unsw-nb15-dataset (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- IDS 2018|Datasets|Research|Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity|UNB. Available online: https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/ids-2018.html (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Cantone, M.; Marrocco, C.; Bria, A. On the Cross-Dataset Generalization of Machine Learning for Network Intrusion Detection. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 144489–144508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinayakumar, R.; Alazab, M.; Soman, K.P.; Poornachandran, P.; Al-Nemrat, A.; Venkatraman, S. Deep Learning Approach for Intelligent Intrusion Detection System. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 41525–41550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaiah, M.; Chandrasekaran, V.; Ravi, V.; Kumar, N. An Intrusion Detection System Using Optimized Deep Neural Network Architecture. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 2021, 32, e4221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandhro, I.; Alanazi, S.; Ali, F.; Kehar, A.; Fatima, K.; Uddin, M.; Karuppayah, S. Detection of Real-Time Malicious Intrusions and Attacks in IoT Empowered Cybersecurity Infrastructures. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 9136–9148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hnamte, V.; Hussain, J. DCNNBiLSTM: An Efficient Hybrid Deep Learning-Based Intrusion Detection System. Telemat. Inform. Rep. 2023, 10, 100053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halimaa, A.; Sundarakantham, K. Machine Learning Based Intrusion Detection System. In Proceedings of the 2019 3rd International Conference on Trends in Electronics and Informatics (ICOEI), Tirunelveli, India, 23–25 April 2019; pp. 916–920. [Google Scholar]

- Karatas, G.; Demir, O.; Sahingoz, O. Increasing the Performance of Machine Learning-Based IDSs on an Imbalanced and Up-to-Date Dataset. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 32150–32162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, R.; Shi, W.; Corriveau, J. Network Intrusion Detection Using Machine Learning Approaches: Addressing Data Imbalance. IET Cyber-Phys. Syst. Theory Appl. 2021, 7, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakami, H.; Faheem, M.; Ahmad, M. Machine Learning Techniques for Enhanced Intrusion Detection in IoT Security. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 31140–31158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukder, M.; Islam, M.; Uddin, M.; Hasan, K.; Sharmin, S.; Alyami, S.; Moni, M. Machine Learning-Based Network Intrusion Detection for Big and Imbalanced Data Using Oversampling, Stacking Feature Embedding and Feature Extraction. J. Big Data 2024, 11, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulhammed, R.; Faezipour, M.; Abuzneid, A.; Abumallouh, A. Deep and Machine Learning Approaches for Anomaly-Based Intrusion Detection of Imbalanced Network Traffic. IEEE Sens. Lett. 2019, 3, 7101404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavithra, S.; Vikas, V. Detecting Unbalanced Network Traffic Intrusions with Deep Learning. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 74096–74107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, M.; Le Khac, N.A.; Jahromi, H.; Jurcut, A.D. A Hybrid CNN-LSTM-Based Approach for Anomaly Detection Systems in SDNs. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security, Vienna, Austria, 17–20 August 2021; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, P.; Sahu, D.; Prakash, S.; Yang, T.; Rathore, R.S.; Pandey, V.K. A High-Performance Hybrid LSTM CNN Secure Architecture for IoT Environments Using Deep Learning. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-C.; Houng, Y.-C.; Chen, H.-X.; Tseng, S.-M. Network Anomaly Intrusion Detection Based on Deep Learning Approach. Sensors 2023, 23, 2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, D.; Sui, Q.; Yang, C.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Luan, T. A CE-GAN Based Approach to Address Data Imbalance in Network Intrusion Detection Systems. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriar, M.; Ansari, M.; Monteuuis, J.; Chen, C.; Petit, J.; Hou, Y.; Lou, W. Vehigan:Generative Adversarial Networks for Adversarially Robust V2X Misbehavior Detection Systems. ACM Trans. Cyber-Phys. Syst. 2024, 9, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Strickland, C.; Zakar, M.; Saha, C.; Nejad, S.; Tasnim, N.; Lizotte, D.; Haque, A. DRL-GAN: A Hybrid Approach for Binary and Multiclass Network Intrusion Detection. Sensors 2023, 24, 2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shendkar, B.D.; Dhotre, D.; Hirve, S.A.; Sontakke, P.; Hingoliwala, H.; Sambare, G.B. Explainable Machine Learning Models for Real-Time Threat Detection in Cybersecurity. Panam. Math. J. 2025, 35, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennaji, S.; de Gaspari, F.; Hitaj, D.; Kbidi, A.; Vincenzo Mancini, L. Adversarial Challenges in Network Intrusion Detection Systems: Research Insights and Future Prospects. IEEE Access 2024, 13, 148613–148645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Dán, G.; Zhu, Q. Human-in-the-Loop Cyber Intrusion Detection Using Active Learning. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2024, 19, 8658–8672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almalawi, A.; Hassan, S.; Fahad, A.; Iqbal, A.; Khan, A.I. Hybrid Cybersecurity for Asymmetric Threats: Intrusion Detection and SCADA System Protection Innovations. Symmetry 2025, 17, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alohali, M.A.; Alamgeer, M.; Al-Sharafi, A.M.; Asklany, S.A.; Aljabri, J.; Alotaibi, F.A.; Alajmani, S.H.; Issaoui, I. Improving Internet of Health Things Security through Anomaly Detection Framework Using Artificial Intelligence Driven Ensemble Approaches. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 33962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakimi, R.; Shalannanda, W.; Heriansyah, H. Consensus-Based Feature Selection and Classifier Benchmarking for Network Anomaly Detection. J. Eng. Sci. Res. 2025, 7, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, E.C.P.; Dadkhah, S.; Ferreira, R.; Zohourian, A.; Lu, R.; Ghorbani, A.A. CICIoT2023: A Real-Time Dataset and Benchmark for Large-Scale Attacks in IoT Environment. Sensors 2023, 23, 5941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; He, J.; Alluhaidan, A.S.; Zhu, N.; Mughal, F.R.; Ahmad, S.; Zardari, Z.A. MultiNet-IDS: An Ensemble of DRL and LSTM for Improved Intrusion Detection in Wireless Sensor Networks. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 33420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A. Deep Learning-Based Intrusion Detection for IoT Networks: A Scalable and Efficient Approach. EURASIP J. Inf. Secur. 2025, 2025, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manocchio, L.; Layeghy, S.; Lo, W.; Kulatilleke, G.; Sarhan, M.; Portmann, M. Flow Transformer: A Transformer Framework for Flow-Based Network Intrusion Detection Systems. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 241, 122564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, W.; Zong, X.; Lian, L. Network Intrusion Detection Based on Feature Image and Deformable Vision Transformer Classification. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 44335–44350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, P.; Sahu, D.; Prakash, S.; Rathore, R.S.; Dixit, P.; Pandey, V.K.; Hunko, I. An Efficient Data Driven Framework for Intrusion Detection in Wireless Sensor Networks Using Deep Learning. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 34046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebrahimi, F.; Javidan, R.; Akbari, R.; Hosseini, Y. Intrusion Detection in the Internet of Things Using Convolutional Neural Networks: An Explainable AI Approach. Cybersecurity 2025, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, A. EC-GAN: Low-Sample Classification Using Semi-Supervised Algorithms and GANs. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2020, 35, 15797–15798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Fok, K.W.; Thing, V.L.L. Enhancing Network Intrusion Detection Performance Using Generative Adversarial Networks. Comput. Secur. 2024, 145, 104005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, T.; Rehman, A.; Mujahid, M.; Al-Rasheed, A.; Al-Otaibi, S.; Yousif, A. Smart Defense Based on Explainable Stacked Machine Learning Architecture for Securing Internet of Health Things with K-Means Clustering. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 37241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Chen, L.; Dong, L.; Fu, Z.; Cui, X. Imbalanced Data Classification: A KNN and Generative Adversarial Networks-Based Hybrid Approach for Intrusion Detection. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2022, 131, 240–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; He, D.; Chan, S. A Lightweight Approach for Network Intrusion Detection in Industrial Cyber-Physical Systems Based on Knowledge Distillation and Deep Metric Learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 206, 117671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Park, K. GAN-Based Imbalanced Data Intrusion Detection System. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2021, 25, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, P.; Sun, Z. RTIDS: A Robust Transformer-Based Approach for Intrusion Detection System. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 64375–64387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, H.; Mashaly, M. Advanced Hybrid Transformer-CNN Deep Learning Model for Effective Intrusion Detection Systems with Class Imbalance Mitigation Using Resampling Techniques. Future Internet 2024, 16, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).