Abstract

We aimed to investigate the type of bone changes in temporomandibular disorder patients with disc displacement. The subjects were 117 temporomandibular joints that were diagnosed with anterior disc displacement using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) pain and opening dysfunction were examined. Disc displacement with and without reduction, joint effusion, and bone changes in the mandibular condyle were assessed on MRI. The types of bone changes were classified into erosion, flattening, osteophyte, and atrophy on the MR images. Fisher’s exact test and χ2 test were performed for analyses. Bone changes were found on 30.8% of subjects with erosion, flattening, osteophyte, and atrophy types (p < 0.001). The occurrence of joint effusion appearance (p < 0.001), TMJ pain (p = 0.027), and opening dysfunction (p = 0.002) differed among the types of bone changes. Gender differences were also found among the types of bone changes (p < 0.001). The rate of disc displacement with reduction was significantly smaller than that of disc displacement without reduction on flattening and osteophyte (p < 0.001). The results made it clear that the symptoms, gender, and presence or absence of disc reduction differed among the types of bone changes.

1. Introduction

Temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) are common diseases in dentistry. The World Health Organization (WHO) indicated that TMDs are the third most common dental condition after dental caries and periodontal disease [1]. TMDs affect 34% of the global population [2], and the prevalence rates differ between each continent. Several epidemiologic studies have reported that 40 to 70% of the general population experiences some signs of TMDs [3,4], and about 4 to 7% of the population indicates symptoms of sufficient severity to need treatment [5]. TMDs are common in women compared to men [6], and the peak age of the prevalence of TMDs is from 45 to 64 [7,8].

TMDs show some clinical problems on the masticatory musculature, the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), and associated structures [9]. The three most common symptoms of TMD are pain, joint noises, and disturbance in jaw opening [10,11,12]. Sometimes, the symptom of headaches appears with TMDs [13,14]. Disease states are classified as myofascial pain, arthralgia, disc displacement with or without reduction, and osteoarthrosis [15,16]. Among these disease states, disc displacement is the most common state [17], and some studies have reported the prevalence of disc displacement as 77 to 89% [18], 48.9% [19], or 41% [17]. Disc displacement is the state in which the TMJ loses the normal disc–condyle relationship in the closed-mouth position, and the displacement of the disc to the anterior, posterior, inner, and outer sides of the condyle occurs [20]. Most disc displacements are to the anterior of the mandible condyle [15,16], which causes internal derangement [12]. Overload of the bilaminar zone of TMJ is caused by the direct contact of the condyle with disc displacement, and the load induces pain in the TMJ [21]. The load can be one of the risk factors for osteoarthrosis [22,23]. Osteoarthrosis involves cartilage destruction, osseous degenerative changes, and subchondral bone remodelling [24,25]. Some studies reported that the internal disorder of TMJ, mainly in the case of disc displacement without reduction (DDWOR), causes osteoarthrosis [23,26].

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been used for the detection of disc displacement. MRI is the gold standard for detecting disc displacement [27] and is necessary for TMD diagnosis [28,29]. Recently, 3D ultrasound has been shown to have acceptable diagnostic efficacy to detect disc displacement with a non-ionizing imaging method, and it is less expensive, transportable, and more comfortable to the patient [9]. It has potential utility in detecting both osteochondral and soft-tissue changes [30]. MRI is effective at characterizing not only the disc morphology or disc position but also the osseous joint morphology [31,32]. On MRI images, the intra-observer agreement for detecting the position of the disc is 95%, and that for osseous changes is 97% [33]. MRI is usually performed with 1.5 T or 3.0 T scanners with a head coil or TMJ surface coil to detect the disc morphology, disc position, and the osseous joint morphology [34]. MRI allows the visualization of hard tissues without exposing the patient to ionizing radiation [35,36], and this is one of the advantages of MRI. Disc displacement and osseous joint morphology can be confirmed at the proton density with high contrast, and the joint effusion is recognized on the T2-emphasized image of MRI. Joint effusion is observed as a hyperintense area on a T2 image, in which synovial fluid is accumulated at the superior and/or inferior articular cavity. Joint effusion reflects the condition of inflammation in TMJ [37].

Previous reports showed that DDWOR occurs as osteoarthrosis [23,26], and a nine-times-greater likelihood of osteoarthrosis occurrence was observed in DDWOR compared to the disc displacement with reduction (DDWR) [28]. Osteoarthrosis shows erosion, flattening, osteophytes, irregularities, or deformities on the surface of the mandibular condyle, as well as subchondral bone sclerosis [38]. However, few reports show the relation between the type of bone changes and the symptoms [39]. This study aimed to examine the type of bone changes in disc displacement and mentions the factors relating to bone changes.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was conducted by reviewing the MRI of TMD patients who came to the Temporomandibular Joint Disorders and Bruxism Clinic, The Nippon Dental University Niigata Hospital (Niigata, Japan). We subjected 117 TMJs of 65 TMD patients (24 male, 93 female, mean age 43.7 ± 18.4 years) who were diagnosed with TMD with anterior disc displacement (with or without reduction) using MRI. Clinical presentation for TMJ pain was interviewed. As a clinical examination, the distance of the mouth opening was measured to check the opening dysfunction. The opening dysfunction was decided when the distance of the mouth opening was smaller than 40 mm, because the opening dysfunction by the DDWOR is defined as smaller than 40 mm by the Japanese Society for Temporomandibular Joints. The distance of mouth opening was decided by measuring the distance between the incisal edge of the upper and lower right central incisors using a calliper and subtracting the overbite distance from the inter-incisal edge distance. After the clinical presentation and the clinical examination, image examination was conducted using MRI. This retrospective study was approved by the ethics committee of our institution.

MRI (1.5 Tesla MR unit; EXCELART VantageMRT-2003; Canon Medical Systems, Otawara, Japan) was used with a surface coil for the TMJ, including proton-density-weighted imaging on the positions of mouth closing and maximum opening of mouth (repetition time/echo time: 2000 ms/18 ms, field of view: 130 mm × 130 mm, matrix size: 256 × 224, 1 acquisition). Additionally, T2-weighted imaging on the mouth closing and maximum opening of the mouth (repetition time/echo time: 3500 ms/100 ms, field of view: 130 mm × 130 mm, matrix size: 256 × 192, 2 acquisition) was included [35,40,41]. MRI images were independently evaluated by two specialists in radiology, and any discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The positions of the disc were confirmed on the proton-density-weighted sagittal imaging, and the TMJs with anterior disc displacement were enrolled in this study. The anterior disc displacement was further classified into DDWR and DDWOR.

Joint effusion was detected on T2-weighted imaging of MRI with hyperintense areas in the articular cavities. Bone changes in the mandibular condyle were also assessed on proton-density-weighted sagittal imaging of MRI. The type of bone changes was classified into erosion, flattening, osteophytes, and atrophy, as stated in the Japanese Society for Temporomandibular Joints (Table 1). When the multiple co-existing bone changes were recognized, the classification was decided based on the one in which the characteristics were clearer by the two specialists of radiology.

Table 1.

Type of bone changes in the mandibular condyle.

Statistical analyses were performed using χ2 tests for analyzing the rate of the type of bone changes, the rate of joint effusion, the rate of TMJ pain, and the rate of opening dysfunction at each type of bone change. The proportion of the number of males and females with each type of bone change was analyzed by Fisher’s exact test, and the post hoc test was performed by residual analysis. Additionally, the proportion of the number of subjects on DDWR and DDWOR with each type of bone change was also analyzed by Fisher’s exact test, and the post hoc test was performed by residual analysis. Analyses were conducted using software (SPSS 17.0, SPSS JAPAN, Tokyo, Japan), and differences in α < 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

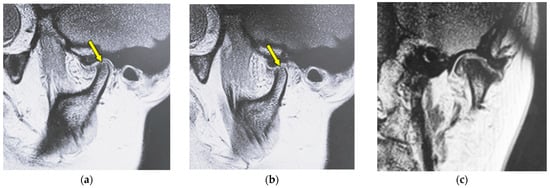

Figure 1 shows MR images of a 43-year-old woman with erosion (left TMJ). Sagittal oblique cross-section imaging (proton-density-weighted) shows anterior disc displacement at the mouth-closing position (Figure 1a) and at mouth-opening positions (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

MR image (proton-density-weighted) of a 43-year-old woman (disc displacement without reduction, left disc): (a) sagittal oblique cross-section imaging in the mouth-closing position; (b) sagittal oblique cross-section imaging in the mouth-opening position; (c) coronal oblique cross-section imaging in the mouth-closing position. The arrow shows the part with erosion.

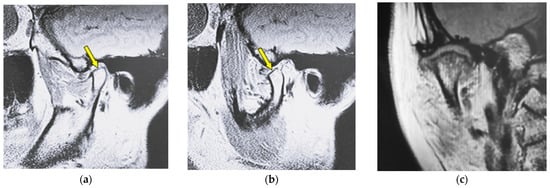

Figure 2 shows MR images of a 51-year-old woman with flattening (right TMJ). Sagittal oblique cross-section imaging (proton-density-weighted) shows anterior disc displacement in the mouth-closing position (Figure 2a) and in the mouth-opening position (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

MR image (proton-density-weighted) of a 51-year-old woman (disc displacement without reduction, right disc): (a) sagittal oblique cross-section imaging in the mouth-closing position; (b) sagittal oblique cross-section imaging in the mouth-opening position; (c) coronal oblique cross-section imaging in the mouth-closing position. The arrow shows the part with flattening.

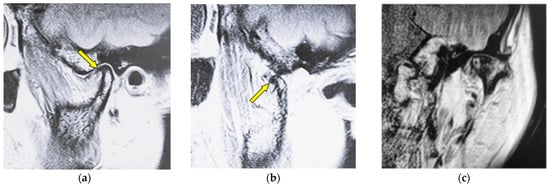

Figure 3 shows MR images of a 53-year-old woman with osteophyte (left TMJ). Sagittal oblique cross-section imaging (proton-density-weighted) shows anterior disc displacement in the mouth-closing position (Figure 3a) and in the mouth-opening position (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

MR image (proton-density-weighted) of a 53-year-old woman (disc displacement without reduction, left disc): (a) sagittal oblique cross-section imaging in the mouth-closing position; (b) sagittal oblique cross-section imaging in the mouth-opening position; (c) coronal oblique cross-section imaging in the mouth-closing position. The arrow shows the part with an osteophyte.

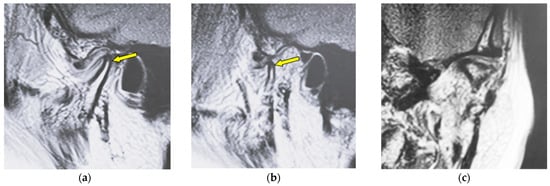

Figure 4 shows MR images of an 82-year-old woman with atrophy (left TMJ). Sagittal oblique cross-section imaging (proton-density-weighted) shows anterior disc displacement in the mouth-closing position (Figure 4a) and in the mouth-opening position (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

MR image (proton-density-weighted) of an 82-year-old woman (disc displacement without reduction, left disc): (a) sagittal oblique cross-section imaging in the mouth-closing position; (b) sagittal oblique cross-section imaging in the mouth-opening position; (c) coronal oblique cross-section imaging in the mouth-closing position. The arrow shows the part with atrophy.

Characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 2. Of the 117 TMJs, 69.2% showed no changes on the mandibular condyle and 30.8% showed changes in the bone such as erosion, flattening, osteophyte, and atrophy. The rates of TMJs with no changes, erosion, flattening, osteophyte, and atrophy were significantly different (χ2 (4) = 151.00, p < 0.001). There were nearly twice as many female subjects as males for each type of bone change. The mean ages of the subjects with erosion and flattening were higher than those with osteophytes, atrophy, and no changes.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the subjects in this study.

The rates of joint effusion, TMJ pain, and opening dysfunction for each type of bone change are shown in Table 3. The appearance of joint effusion differed by the type of bone changes (χ2 (4) = 34.45, p < 0.001). Joint effusion appeared in all cases of atrophy. In contrast, joint effusion was found in only 33.3% cases of erosion. The appearance of TMJ pain differed by the type of bone changes (χ2 (4) = 10.95, p = 0.027). TMJ pain appeared in 62.5% of osteophyte cases, and it appeared in only 33.3% of erosion cases. The appearance of opening dysfunction differed by the type of bone changes (χ2 (4) = 16.93, p = 0.002). Opening dysfunction was recognized in 87.5% of osteophyte cases and only 44.4% of atrophy cases.

Table 3.

The rate of joint effusion, TMJ pain, and opening dysfunction at each type of bone change.

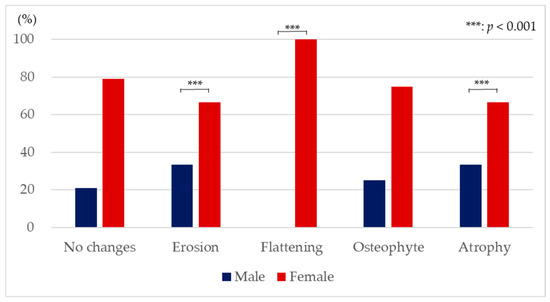

Figure 5 shows the proportion of the number of males and females for each type of bone change. Flattening was observed in only females, and erosion and atrophy were recognized more in females compared to males (χ2 (4) = 42.30, p < 0.001). Statistically significant gender differences were not found when a bone change did not occur and when there were osteophytes.

Figure 5.

Proportion of the number of males and females with each type of bone change (Fisher’s exact test and residual analysis).

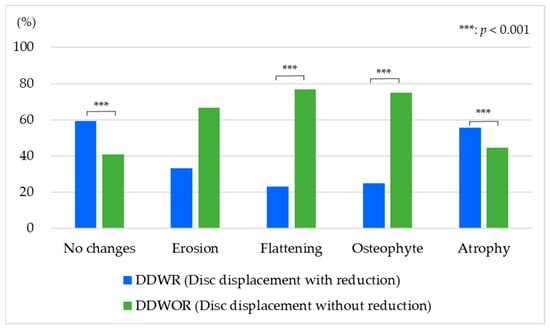

Figure 6 shows the proportion of the number of subjects with DDWR and those with DDWOR for each type of bone changes (χ2 (4) = 49.38, p < 0.001). The rate of DDWR was significantly larger than that of DDWOR on the condition that the bone change did not occur (DDWR: 59.3%, DDWOR: 40.7%). The rate of DDWR tended to be smaller than that of DDWOR on erosion (DDWR: 33.3%, DDWOR: 66.7%). The rate of DDWR was significantly lower than that of DDWOR on flattening (DDWR: 23.1%, DDWOR: 76.9%). The rate of DDWR was also significantly lower than that of DDWOR on osteophyte (DDWR: 25.0%, DDWOR: 75.0%). The rate of DDWR was significantly larger than that of DDWOR with atrophy (DDWR: 55.6%, DDWOR: 44.4%).

Figure 6.

Proportion of the number of subjects with disc displacement with reduction and that with disc displacement without reduction for each type of bone change (Fisher’s exact test and residual analysis).

4. Discussion

This study investigated the type of bone changes in TMD patients with disc displacement and examined the relation to the symptoms, gender, and presence or absence of reduction. Subjects over a wide range of ages were included in this study because a significant association between DDWOR and bone changes has been reported in children and adolescent patients with TMD [42]. DDWR is the condition in which the articular disc loses the normal disc–condyle relationship in the closed-mouth position and the disc is in the normal disc–condyle relationship in the opened-mouth position. On the other hand, DDWOR is the condition in which the articular disc loses the normal relationship between the disc and the condyle in both the mouth-closing position and the mouth-opening position. The articular disc plays an important role as a cushion for the condyle and fossa. Under the condition of disc displacement, the cushion cannot work to reduce the impact between the condyle and the fossa, so the internal derangement can easily occur [12]. Therefore, disc displacement leads to symptoms such as TMJ pain, noises, and disturbance of jaw opening and can progress to condylar degeneration [43]. These symptoms appear to worsen with function [44], and the disease state TMD causes the deterioration of quality of life (QOL).

The load imposed on the TMJ can be handled when the articular disc is in its normal physiological position between the mandibular bone surface and the temporal bone surface [45]. However, in the cases that the articular disc is displaced, the load imposed on the TMJ cannot be controlled, which would then lead to osteoarthrosis [37,46]. In this study, TMD patients with disc displacement were examined; 69.2% showed no changes on the mandibular condyle, and 30.8% showed bone changes (Table 2). It is expected that 30.8% of the TMD patients with bone changes will progress from the condition of disc displacement, and the other 69.2% of the TMD patients without bone changes could show bone changes in the years ahead. Some treatment would be needed for TMD with disc displacement to prevent or delay the progress to osteoarthrosis.

Joint effusion has been reported to indicate intra-articular inflammation or synovitis with internal derangement [47] and osteoarthrosis [43]. In this study, joint effusion was observed in 64.2% of TMJs without any bone changes. Joint effusion appearance differed by the type of bone changes, and joint effusion appeared in all cases of atrophy, 69.2% of flattening, 62.5% of osteophyte, and 33.3% of erosion (Table 3). Besides erosion, joint effusion appeared in more than half of the cases of TMJ with disc displacement. This result suggests that the appearance of joint effusion differs by the type of bone changes, and it can easily appear in cases of disc displacement.

The appearance of TMJ pain differed by the type of bone changes, and TMJ pain appeared in 62.5% of osteophytes, 46.2% of flattening, 44.4% of atrophy, and 33.3% of erosion. TMJ pain was also found in 39.5% of TMJ without any bone changes (Table 3). The load to the TMJ would be larger in the case of disc displacement, and then, the TMJ pain would easily appear in cases of disc displacement. It was suggested that TMJ pain can easily appear in the case of disc displacement, and the tendency would be stronger in the case of disc displacement with bone changes. There are several reports that showed a positive relationship between joint effusion and TMJ pain [48]. In this study, the TMJ pain was not recognized in as many TMJs as the appearance of joint effusion. In a future study, the relation between joint effusion and TMJ pain with an increased number of subjects should be investigated to analyze the causes of joint effusion and TMJ pain in osteoarthrosis.

The appearance of opening dysfunction differed by the type of bone changes and was found in 87.5% of osteophyte cases, 76.9% of flattening cases, 66.7% of erosion cases, and 44.4% of atrophy cases. Opening dysfunction was also found in 59.3% of TMJ cases without any bone changes (Table 3). This tendency was similar to that of TMJ pain, and TMJ pain and opening dysfunction easily appeared on osteophytes. In the limit of this study, it was suggested that osteophyte would be related to the appearance of symptoms such as TMJ pain and dysfunction in moving. Further investigation would be necessary to make the relationship between the symptom and bone changes clear.

Gender differences were found both in the condition where bone changes did not occur and in the condition with bone changes. The rate in females was more than twice that in males in all conditions. This result agreed the previous reports [6]. The reason for gender differences in the prevalence of TMD would be related to social factors, differences in pain sensitivity, and health-seeking behaviours [49,50]. Additionally, females are more susceptible because the influence of hormones and physiologic differences between genders would be related [51]. The result of this study indicated that the bone changes in TMJ also easily occurred in females.

The rate of DDWR was significantly lower than that of DDWOR on flattening and osteophyte. Four cases showed multiple co-existing bone changes (flattening and osteophytes, flattening and erosion, osteophytes and erosion, and osteophytes and atrophy), and the classification was shown to be the one in which the characteristics were clearer. The rate of DDWOR was significantly lower than that of DDWR with atrophy and the condition without any bone changes. The unexpected finding that atrophy occurred more frequently with DDWR than DDWOR deserves further investigation. This may reflect different biomechanical loading patterns or distinct pathophysiological pathways. Future studies with larger sample sizes and longitudinal designs are needed to clarify these relationships. It was suggested that changes in the mandibular condyle shape would easily occur with the progress from DDWOR. This result supports the previous reports that mentioned that DDWOR causes osteoarthrosis [23,26,27]. Additionally, the results of this study suggest the possibility that some types of osteoarthrosis, such as atrophy, could easily appear with DDWR.

A major limitation of this study was that MRI was used for the investigation of the type of bone changes in TMD patients. The main strength of MRI is the detailed illustration of soft tissue structures, and it also enables the visualization of bone [52,53]. Computed tomography (CT) and cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) enable a more precise analysis of the osseous components [54,55]. Concerning MRI, T1-weighted 3.0-T MRI can quantify the cortical bone cross-sectional area with a high resolution in comparison with quantitative CT [56], and the delineation of the cortical bone on TMJ is significantly better in images derived by a 3.0-T MRI rather than a 1.5-T MRI [57]. The MRI used in this study was a 1.5-T MRI, which is not enough to observe bone structure in detail, and the diagnostic accuracy might be lower compared to that using CT, CBCT, and 3.0-T MRI or 3D ultrasound. MRI images were independently evaluated by two specialists of radiology and lacked the inter- or intra-rater reliability. An additional limitation was the study design. This study was retrospective and investigated only anterior disc displacement joints at the single-centre clinic. This study was evaluated with small subgroup sizes and the inclusion of two joints from some patients; therefore, there is a possibility that the reproducibility would be low, and it appears difficult to perform sufficiently robust comparisons between individual types of condylar bone changes to draw meaningful conclusions or clinical relevance in this study. The asymptomatic population was not included in this study, so it cannot show a cause-and-effect relationship. TMJ pain was determined only by interviews in this study; therefore, there is a possibility that the assessment of the TMJ pain differed from that using standardized criteria. Thus, this study has limitations, including the retrospective design, the use of 1.5 T MRI rather than 3 T or CT, and relatively small subgroup sizes. These findings should be considered preliminary and warrant validation in larger prospective studies.

This study investigated the type of bone changes in TMD patients with disc displacement, and the relations to symptoms, gender, and the presence or absence of reduction were analyzed. The results suggested that symptoms, gender, and the presence or absence of reduction differed by the type of bone changes. It was considered that bone change appearances varied among the TMJs, and the diagnosis of osteoarthrosis using MRI is very important to grasp bone changes. In future research, the bone changes on mandibular condyles should be investigated with more subjects, and the mechanism of the occurrence of the difference between bone change types should be clarified.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the type of bone changes in TMD patients with disc displacement using MRI and found that 69.2% showed no changes in the mandibular condyle and 30.8% showed bone changes. Erosion, flattening, and atrophy were recognized more in females compared to males. Flattening and osteophyte easily occur on disc displacement without reduction. Joint effusion appeared in all cases of atrophy, and the symptoms of TMJ pain and opening dysfunction easily appeared in osteophytes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.M., I.O. and R.M.; methodology, F.M.; software, F.M.; validation, F.M., I.O., R.M., Y.W., T.S., M.K., K.N. and T.N.; formal analysis, F.M.; investigation, F.M. and R.M.; resources, M.K., K.N. and T.N.; data curation, F.M. and T.S.; writing—original draft preparation, F.M.; writing—review and editing, F.M., I.O. and M.O.; visualization, R.M. and Y.W.; supervision, F.M.; project administration, F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of The Nippon Dental University School of Life Dentistry at Niigata (ECNG-R-318, 12 June 2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ey-Chmielewska, H.; Teul, I.; Lorkowskl, J. Functional disorders of the temporomandibular joints as a factor responsible for sleep apnoea. Ann. Acad. Med. Stetin. 2014, 60, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, G.; Pająk-Zielińska, B.; Ginszt, M. A meta-analysis of the global prevalence of temporomandibular disorders. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Progiante, P.S.; Pattussi, M.P.; Lawrence, H.P.; Goya, S.; Grossi, P.K.; Grossu, M.L. Prevalence of temporomandibular disorders in an adult Brazilian community population using the research diag nostic criteria (axes I and II) for temporomandibular disorders (the Maringá study). Int. J. Prosthodont. 2015, 28, 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakkaphan, P.; Smith, J.G.; Chana, P.; Tan, H.L.; Ravindranath, P.T.; Lambru, G.; Renton, T. Temporomandibular disorders and fibromyalgia prevalence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Oral Facial Pain Headache 2023, 37, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouanounou, A.; Goldberg, M.; Haas, D.A. Pharmacotherapy in temporomandibular disorders: A review. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2017, 83, h7. [Google Scholar]

- Minervini, G.; Franco, R.; Marrapodi, M.M.; Fiorillo, L.; Cervino, G.; Cicciù, M. Prevalence of temporomandibular disorders in children and adolescents evaluated with diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Oral Rehabil. 2023, 50, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maixner, W.; Fillingim, R.B.; Williams, D.A.; Smith, S.B.; Slade, G.D. Overlapping chronic pain conditions: Implications for diagnosis and classification. J. Pain 2016, 17, T93–T107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lora, V.R.; Canales, G.L.; Goncalves, L.M.; Meloto, C.B.; Barbosa, C.M. Prevalence of temporomandibular disorders in postmenopausal women and relationship with pain and HRT. Braz. Oral Res. 2016, 30, e100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, F.T.; Pacheco-Pereira, C.; Flores-Mir, C.; Le, L.H.; Jaremko, J.L.; Major, P.W. Diagnostic ultrasound assessment of temporomandibular joints: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2019, 48, 20180144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamon, N.M.; Casselman, J.W. Temporomandibular joint disorders: A pictorial review. Semin. Musculoskelet. Radiol. 2020, 24, 591–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalladka, M.; Young, A.; Thomas, D.; Heir, G.M.; Quek, S.Y.P.; Khan, J. The relation of temporomandibular disorders and dental occlusion: A narrative review. Quintessence Int. 2022, 53, 450–459. [Google Scholar]

- Herb, K.; Cho, S.; Stiles, M.A. Temporomandibular joint pain and dysfunction. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2006, 10, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, P.E.; Stancampiano, F.F.; Rozen, T.D. Migraine headache: Updates and future developments. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2018, 93, 1648–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Reyes, M.; Bassiur, J.P. Temporomandibular disorders, bruxism and headaches. Neurol. Clin. 2024, 42, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, D.; Piccotti, F.; Ferronato, G.; Guarda-Nardini, L. Age peaks of different RDC/TMD diagnoses in a patient population. J. Dent. 2010, 38, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauer, R.L.; Semidey, M.J. Diagnosis and treatment of temporomandibular disorders. Am. Fam. Physician 2015, 91, 378–386. [Google Scholar]

- Miernik, M.; Więckiewicz, W. The basic conservative treatment of temporomandibular joint anterior disc displacement without reduction-Review. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 24, 731–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.; Huang, C.; Zhou, F.; Xia, F.; Xiong, G. Finite elements analysis of the temporomandibular joint disc in patients with intra-articular disorders. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osiewicz, M.A.; Lobbezoo, F.; Loster, B.W.; Loster, J.E.; Manfredini, D. Frequency of temporomandibular disorders diagnoses based on RDC/TMD in a Polish patient population. Cranio 2018, 36, 304–310. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D.; Liu, L.; Zhai, X.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Xu, X.; Li, H.; Jiang, H. Association between chewing side preference and MRI characteristics in patients with anterior disc displacement of the temporomandibular joint. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 124, 101484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, D.P.A.; Doblaré, M. An accurate simulation model of anteriorly displaced TMJ discs with and without reduction. Med. Eng. Phys. 2007, 29, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, I.M.; Coelho, P.R.; Picorelli Assis, N.M.; Pereira Leite, F.P.; Devito, K.L. Evaluation of the correlation between disc displacements and degenerative bone changes of the temporomandibular joint by means of magnetic resonance images. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 41, 1051–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, K.J.; List, T.; Petersson, A.; Rohlin, M. Relationship between clinical and magnetic resonance imaging diagnoses and findings in degenerative and inflammatory temporomandibular joint diseases: A systematic literature review. J. Orofac. Pain 2009, 23, 123–139. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.D.; Zhang, J.N.; Gan, Y.H.; Zhou, Y.H. Current understanding of pathogenesis and treatment of TMJ osteoarthritis. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yang, H.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, J.; Lu, L.; Yu, S.; Wu, Y.; Wang, M. Initiation and progression of dental-stimulated temporomandibular joints osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2021, 29, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, K.; Natsumi, Y.; Urade, M. Correlation between MRI evidence of degenerative condylar surface changes, induction of articular disc displacement and pathological joint sounds in the temporomandibular joint. Gerodontology 2008, 25, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomas, X.; Pomes, J.; Berenguer, J.; Quinto, L.; Nicolau, C.; Mercader, J.M.; Castro, V. MR imaging of temporomandibular joint dysfunction: A pictorial review. Radiographics 2006, 26, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styles, C.; Whyte, A. MRI in the assessment of internal derangement and pain within the temporomandibular joint: A pictorial essay. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2002, 40, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersson, A. What you can and cannot see in TMJ imaging -An overview related to the RDC/TMD diagnostic system. J. Oral Rehabil. 2010, 37, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotolo, R.P.; d’Apuzzo, F.; Femiano, F.; Nucci, L.; Minervini, G.; Grassia, V. Comparison between ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging of the temporomandibular joint in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: A systematic review. J. Oral Rehabil. 2023, 50, 1082–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willenbrock, D.; Lutz, R.; Wuest, W.; Heiss, R.; Uder, M.; Behrends, T.; Wurm, M.; Kesting, M.; Wiesmueller, M. Imaging temporomandibular disorders: Reliability of a novel MRI-based scoring system. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2022, 50, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toshima, H.; Ogura, I. Characteristics of patients with temporomandibular joint osteoarthrosis on magnetic resonance imaging. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 64, 615–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerele, C.; Avsenik, J.; Šurlan, P.K. MRI characteristics of the asymptomatic temporomandibular joint in patients with unilateral temporomandibular joint disorder. Oral Radiol. 2021, 37, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoliu, A.; Spinner, G.; Wyss, M.; Erni, S.; Ettlin, D.A.; Nanz, D.; Ulbrich, E.J.; Gallo, L.M.; Andreisek, G. Quantitative and qualitative comparison of MR imaging of the temporomandibular joint at 1.5 and 3.0 T using an optimized high-resolution protocol. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2016, 45, 20150240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertram, S.; Moriggl, A.; Rudisch, A.; Emshoff, R. Structural characteristics of bilateral temporomandibular joint disc displacement without reduction and osteoarthrosis are important determinants of horizontal mandibular and vertical ramus deficiency: A magnetic resonance imaging study. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 69, 1898–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badel, T.; Marotti, M.; Keros, J.; Kern, J.; Krolo, I. Magnetic resonance study on temporomandibular joint morphology. Coll. Antropol. 2009, 33, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kakimoto, N.; Wongratwanich, P.; Shimamoto, H.; Kitisubkanchana, J.; Tsujimoto, T.; Shimabukuro, K.; Verdonschot, R.G.; Hasegawa, Y.; Murakami, S. Comparison of T2 values of the displaced unilateral disc and retrodiscal tissue of temporomandibular joints and their implications. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertram, S.; Rudish, A.; Innerhofer, K.; Pümpel, E.; Grubwieser, G.; Emshoff, R. Diagnosing TMJ. internal derangement and osteoarthrosis with magnetic resonance imaging. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2001, 132, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, I.M.; Cordeiro, P.C.; Devito, K.L.; Tavares, M.L.; Leite, I.C.; Tesch, R.S. Evaluation of temporomandibular joint disc displacement as a risk factor for osteoarthrosis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 45, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuhashi, F.; Ogura, I.; Mizuhashi, R.; Watarai, Y.; Oohashi, M.; Suzuki, T.; Saegusa, H. Examination for the factors involving to joint effusion in patients with temporomandibular disorders using magnetic resonance imaging. J. Imaging 2023, 9, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuhashi, F.; Ogura, I.; Mizuhashi, R.; Watarai, Y.; Oohashi, M.; Suzuki, T.; Kawana, M.; Nagata, K. Examination of joint effusion magnetic resonance imaging of patients with temporomandibular disorders with disc displacement. J. Imaging 2024, 10, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moncada, G.; Cortés, D.; Millas, R.; Marholz, C. Relationship between disk position and degenerative bone changes in temporomandibular joints of young subjects with TMD. An MRI study. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2014, 38, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, Y.; Chen, L.; Tian, S.; Abdelrehem, A.; Feng, J.; Fu, G.; Chen, W.; Ding, C.; Luo, Y.; et al. Proteome analysis of temporomandibular joint with disc displacement. J. Dent. Res. 2022, 101, 1580–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalladka, M.; Quek, S.; Heir, G.; Eliav, E.; Mupparapu, M.; Viswanath, A. Temporomandibular joint osteoarthrosis: Diagnosis and long-term conservative management: A topic review. J. Indian Prosthodont. Soc. 2014, 14, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, A.; McNamara, D.; Rosenberg, I.; Whyte, A. Magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of temporomandibular joint disc displacement -A review of 144 cases. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2006, 35, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurita, H.; Uehara, S.; Yokochi, M.; Nakatsuka, A.; Kobayashi, H.; Kurashina, K. A long-term follow-up study of radiographically evident degenerative changes in the temporomandibular joint with different conditions of disk displacement. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2006, 35, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emshoff, R.; Brandlmaier, I.; Bertram, S.; Rudisch, A. Relative odds of temporomandibular joint pain as a function of magnetic resonance imaging findings of internal derangement, osteoarthrosis, effusion, and bone marrow edema. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2003, 95, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emshoff, R.; Brandlmaier, I.; Bertram, S.; Rudisch, A. Risk factors for temporomandibular joint pain in patients with disc displacement without reduction—A magnetic resonance imaging study. J. Oral Rehabil. 2003, 30, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilanova, L.; Goncalves, T.; Meirelles, L.; Garcia, R. Hormonal fluctuations intensify temporomandibular disorder pain without impairing masticatory function. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2015, 28, 72–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Harthy, M.; Ohrbach, R.; Michelotti, A.; List, T. The effect of culture on pain sensitivity. J. Oral Rehabil. 2016, 43, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bueno, C.H.; Pereira, D.D.; Pattussi, M.P.; Grossi, P.K.; Grossi, M.L. Gender differences in temporomandibular disorders in adult populational studies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Oral Rehabil. 2018, 45, 720–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlo, C.A.; Patcas, R.; Kau, T.; Watzal, H.; Signorelli, L.; Müller, L.; Ullrich, O.; Luder, H.U.; Kellenberger, C.J. MRI of the temporo-mandibular joint: Which sequence is best suited to assess the cortical bone of the mandibular condyle? A cadaveric study using micro-CT as the standard of reference. Eur. Radiol. 2012, 22, 1579–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larheim, T.A.; Abrahamsson, A.K.; Kristensen, M.; Arvidsson, L.Z. Temporomandibular joint diagnostics using CBCT. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2015, 44, 20140235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almashraqi, A.A.; Ahmed, E.A.; Mohamed, N.S.; Halboub, E.S. An MRI evaluation of the effects of qat chewing habit on the temporomandibular joint. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2018, 126, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilgenberg-Sydney, P.B.; Bonotto, D.V.; Stechman-Neto, J.; Zwir, L.F.; Pachêco-Pereira, C.; Canto, G.L.; Porporatti, A.L. Diagnostic validity of CT to assess degenerative temporomandibular joint disease: A systematic review. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2018, 47, 20170389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, O.; Cattrysse, E.; Scafoglieri, A.; Luypaert, R.; Clarys, J.P.; de Mey, J. Accuracy of peripheral quantitative computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in assessing cortical bone cross-sectional area: A cadaver study. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 2010, 34, 469–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehling, C.; Vieth, V.; Bachmann, R.; Nassenstein, I.; Kugel, H.; Kooijman, H.; Heindel, W.; Fischbach, R. High-resolution magnetic resonance imaging of the temporomandibular joint: Image quality at 1.5 and 3.0 Tesla in volunteers. Investig. Radiol. 2007, 42, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.