Abstract

This paper presents Greenopoli, an innovative framework for sustainability and waste management education that has engaged over 600 schools and 90,000 students since 2014. Greenopoli is founded on the idea that children and youth can grasp environmental issues as well as adults and act as agents of change within their families and communities. The Greenopoli approach combines scientific accuracy with playful, creative pedagogy to simplify complex topics and stimulate peer-to-peer learning. It includes storytelling, games, field visits, and “green raps” (original environmental songs co-created with students). The framework is adaptive, with content and activities tailored to education stages from kindergarten through university. Educators adopt the role of moderators or facilitators, encouraging students to discuss and discover concepts collaboratively. Greenopoli’s participatory method has been implemented across all age groups, yielding enthusiastic engagement and tangible outcomes in waste sorting and recycling behaviors. The program’s reach has extended beyond schools through collaborations with national recycling consortia, NGOs, municipalities, and media (TV programs, social media, TEDx talks). Numerous awards and recognitions (2017–2025) have highlighted its impact. A comparative analysis shows that Greenopoli’s use of peer-led learning, gamification, and creative communication aligns with global best practices while offering a unique blend of tools. Greenopoli is a novel best-practice model in environmental education, bridging theory and practice and contributing to the goals of Education for Sustainable Development and a circular economy. It demonstrates the effectiveness of engaging youth as change-makers through interactive and creative learning, and it can inspire similar initiatives globally.

1. Introduction

There is no age limit for adopting sustainable behaviors, yet childhood and adolescence are widely considered the most crucial periods for instilling values, habits, and skills that persist into adulthood. In the context of waste management, experience has shown that young people are fully capable of understanding environmental issues and can even influence the behavior of adults around them [1,2].

Educating children and youth on sustainability thus serves a dual purpose: empowering younger generations to build a sustainable future and indirectly transmitting pro-environmental messages to adults via intergenerational learning. For example, a school-based recycling initiative in Europe found that engaging children led to a 4.5% reduction in residual waste and significant increases in recycling of paper, glass, cans, and textiles, demonstrating the powerful ripple effect from students to families [3]. Children are not merely “future citizens”, as they are active contributors in the present, consuming, recycling, creating, and influencing society.

Education is widely recognized as a foundation for achieving sustainable development, starting from the earliest years. UNESCO emphasizes that early childhood education can significantly contribute to a sustainable society, and global monitoring reports stress the need for education systems to foster “education for people and the planet” [4]. However, a persistent gap remains between the acknowledged importance of sustainability education and its practical implementation in schools.

Policy research has noted that many school curricula worldwide still do not adequately include environmental and sustainability education, or do so in a fragmented way. Even in Europe, the integration of waste and recycling topics into formal education varies widely. A recent five-country survey found major disparities in the extent of waste education delivered, with time constraints, lack of teacher awareness, and scarce resources cited as the main barriers to including waste topics in the classroom [3].

These findings support calls in the literature for a paradigm shift from traditional, transmissive teaching methods toward active, learner-centered approaches in environmental education. Research has consistently highlighted the need for interactive, learner-centered methods that engage students in real-world problem-solving such as role-play, projects, and hands-on activities. Such active learning strategies have been shown to improve both understanding and motivation in sustainability contexts. Likewise, there is a recognized need for educators to develop the competencies, attitudes, and skills to effectively teach environmental topics, serving as role models in sustainability practice [5,6,7,8,9].

In response to these challenges, numerous innovative education models and communication strategies have emerged in recent years to promote recycling and circular economy values. International frameworks for Education for Sustainable Development encourage creative pedagogy and youth empowerment. For instance, UNESCO’s Trash Hack campaign (launched in 2021) mobilized schools worldwide to take simple “trash hacking” actions against waste, emphasizing hands-on learning, peer collaboration, and creative expression in waste reduction projects [10].

In Europe, the well-established Eco-Schools program (Foundation for Environmental Education), which now involves over 59,000 schools across 68 countries, similarly empowers students through a whole-school approach that includes forming eco-committees and action plans for themes like waste, water, and energy [3].

These approaches underscore the value of student participation, community involvement, and engaging communication in fostering a “waste-aware” culture from an early age. Within this context, Greenopoli was developed as an innovative environmental education framework that blends scientific rigor with playful, participatory learning tools. The Greenopoli method specifically focuses on waste management, circular economy, and sustainability across all educational stages, from kindergarten to university, through an integrated educational and communicative approach that places schools at the core of a broader community engagement strategy [11].

From a theoretical perspective, learner-centered and relationship-oriented pedagogies provide a particularly appropriate framework for sustainability and recycling education, where learning outcomes extend beyond knowledge acquisition to include values, attitudes, and behaviors. Educational research has consistently shown that supportive teacher–learner relationships, emotional engagement, and participatory learning environments enhance students’ motivation, engagement, and depth of learning [12,13]. Within this perspective, gamification can be understood not merely as a motivational add-on, but as a pedagogical strategy that facilitates experiential learning, peer interaction, and the internalization of complex concepts through play, narrative, and challenge. Such approaches are especially relevant for addressing the gap identified in the literature, namely the limited systematization of long-term, narrative-based, and relational educational practices in real-world and non-formal contexts. By integrating student-centered pedagogy with gamified and creative tools, educational models can more effectively bridge the divide between environmental education theory and everyday recycling practices.

This paper presents the Greenopoli framework in detail, discussing its contents, methods, and adaptation to different age groups. It examines Greenopoli long-term implementation in diverse educational settings and reflects on its educational outcomes and learning-related effects through qualitative observations and selected quantitative evidence. By highlighting Greenopoli distinctive features, such as peer-to-peer learning, gamified activities, and creative storytelling (including “green raps”), the current paper illustrates how this method contributes to recycling education and communication in support of a circular economy. The strengths of the Greenopoli experience and the lessons learned are discussed as potential inputs for future educational initiatives and policy-oriented actions aiming to bridge the gap between environmental education theory and practice.

Despite the growing body of literature on recycling technologies, waste management systems, and circular economy policies, comparatively less attention has been devoted to the educational and relational dimensions through which recycling practices are learned, internalized, and sustained by citizens. In particular, there is a limited number of contributions that systematically describe and critically reflect on long-term, narrative-based, and relationship-centered educational approaches, especially those implemented in real-world, non-formal contexts and involving diverse age groups. This gap is particularly relevant in light of educational research highlighting the central role of teacher–learner relationships, emotional engagement, and supportive learning environments in fostering motivation, engagement, and meaningful learning processes [12,13].

Within this gap, the present paper does not aim to test hypotheses or to statistically generalize results, but rather to document, systematize, and reflect on an educational methodology for recycling developed and implemented over nearly two decades. The proposed approach integrates environmental education, emotional engagement, storytelling, and community participation, with the objective of fostering awareness, responsibility, and pro-environmental behaviors related to recycling.

Accordingly, the aim of this study is to present and discuss a structured yet adaptable educational model for recycling education, grounded in experiential practice and supported by qualitative reflections and selected quantitative evidence derived from its application in different educational contexts.

The specific objectives of the paper are as follows: (i) to describe the conceptual foundations and pedagogical principles underlying the proposed educational approach; (ii) to illustrate its implementation through selected case studies conducted in formal and informal educational settings; (iii) to discuss its educational relevance, transferability, and potential contribution to sustainability education for recycling.

Within this conceptual and methodological framework, the guiding research question is formulated as follows: How can a narrative- and relationship-centered educational approach contribute to recycling education and sustainability awareness across different age groups and learning contexts?

2. The Greenopoli Educational Framework

2.1. General Aspects and Tools

Greenopoli is an innovative educational framework for sustainability launched in 2006 in Southern Italy. Since December 2014, it has reached approximately 600 schools and over 90,000 students (as of 2025), primarily in Italy, through workshops, projects, and public engagement events. The framework is centered on two core concepts: sharing and sustainability. Sharing refers to the pedagogical approach, namely an interactive, peer-to-peer learning ethos where knowledge is co-created and disseminated among students, educators, and the wider community. Sustainability refers to the content focus: the themes of environmental protection, waste reduction, recycling, and broader sustainable development goals that Greenopoli seeks to convey. Figure 1 illustrates these twin pillars of the Greenopoli philosophy, together with its official symbol (in Italian, “condivisione” and “sostenibilità”) [11].

Figure 1.

The symbol of the Greenopoli method and its two core concepts: sharing and sustainability.

In the Greenopoli method, the role of the educator shifts from a traditional instructor to a facilitator or “moderator” of learning. Rather than lecturing from a podium, the educator creates a friendly, inclusive atmosphere and guides students through discussions and activities. Sessions typically begin by eliciting students’ existing ideas and questions about a topic; the educator then intervenes at intervals with supportive prompts, clarifications, or new concepts to enrich the dialog. This moderated, discussion-driven style aligns with constructivist and mediated learning approaches, which suggest that students build deeper understanding when they actively process information and teach each other, with the teacher scaffolding the process. By positioning themselves “at the level of the students” even physically (e.g., sitting in a circle rather than standing apart), Greenopoli’s educators foster a sense of partnership and mutual respect in the classroom. The educator is encouraged to show enthusiasm, humor, and authenticity, becoming “a student among the students” in order to learn from them as well. This approach echoes findings that positive empathic teacher–student relationships can enhance student engagement and learning outcomes [12,13]. By breaking down hierarchies, Greenopoli practitioners create a safe space where students feel valued and eager to participate. Across all educational stages, the Greenopoli method consistently relies on active participation, peer learning, and emotional engagement as core pedagogical principles. These elements remain constant, while language, activities, and levels of responsibility are progressively adapted to the learners’ age and educational context.

A signature tool of Greenopoli is the use of rap music and rhythm to convey environmental messages, an approach dubbed “green rapping”. This idea was born spontaneously when middle-school students requested a rap song about recycling, prompting the Greenopoli educator to improvise one. Ever since, brief rap songs with environmental lyrics have become a staple of Greenopoli sessions. These green raps use simple rhymes and catchy beats to summarize key points (for example, a “Little Rap of Knowledge” uses verses to reinforce concepts of patience, planning, and learning from mistakes in sustainability). The rhymes work especially well in the native Italian, but even in translation they serve as mnemonic devices (e.g., “Time, patience, passion and skills, think and rethink always pay the bills!”). The novelty and fun of rap music help capture students’ attention, particularly among children who might find standard lectures dull. Moreover, this makes the learning experience memorable.

This use of music is not merely for entertainment. It reflects a core pedagogical strategy of Greenopoli: shifting the language of environmental discourse to make it more engaging, inclusive, and transformative. Greenopoli recognizes that every cultural revolution begins with a revolution in words, and many commonly used terms in the waste management field (e.g., waste, garbage, or trash) are linguistically outdated and psychologically disempowering. They reflect a linear, throwaway mentality inherited from a past era, inconsistent with circular economy principles. In response, Greenopoli encourages students to rethink and reshape their vocabulary as a step toward deeper behavioral and cultural change.

This philosophy is captured in the following original rap, “The Green Rap of Change”, which has been used in Greenopoli workshops to spark reflection and dialog on the power of words and the urgency of sustainable action:

Waste and garbage, trash and rubbish

Such bad words, they have to vanish!

Reduce and reuse, nothing to lose,

It’s not so strange, it’s time to change!

Buy and consume a lot? No way–it’s not!

Avoid such a shame, life is not a game!

Reduce and reuse, nothing to lose,

It’s not so strange, it’s time to change!

Collect and separate, fix and regenerate,

Collect and separate, lower the fee rate!

Through rhythm, rhyme, and repetition, the rap conveys key environmental messages while also challenging learners to adopt new perspectives. It exemplifies how Greenopoli’s method transcends traditional didactic models by making learning a participatory, linguistic, and emotional experience.

Greenopoli’s use of music and storytelling is in line with a broader trend of leveraging pop culture and the arts in environmental education. Studies have shown that integrating storytelling and narrative can significantly improve children’s environmental awareness and attitudes [14]. Likewise, educators who employed hip-hop music in science classes observed enhanced engagement and the development of a “critical ecological literacy” among students, as they created their own eco-themed rap lyrics [15]. By tapping into youth culture, Greenopoli communicates in a language that resonates with students.

In addition to raps, Greenopoli sessions incorporate storytelling, games, and hands-on activities. Complex environmental concepts are often introduced through stories or analogies that children can relate to. For instance, to convey the idea of challenging assumptions and seeing things from new perspectives, the Greenopoli instructor might tell the tale of the “Three Little Wolves of Greenopoli”, which is a twist on the classic fable of the “Three Little Pigs”, where the wolf is not evil but misunderstood. This story encourages children to question stereotypes (in this case, “the big bad wolf”) and learn that things in nature are not always what they seem, an idea inspired by De Bono’s work on teaching creative thinking to children [16].

Interactive games are another essential component; students may engage in sorting contests, recycling board games, or tactile activities with different materials. For example, one game uses various waste items (plastic, metal, paper, etc.) that students handle and listen to, because each material makes a distinct sound, helping even very young children deduce which recycling bin each item belongs to. Through playful competition and sensory engagement, students learn waste-sorting rules in a concrete way.

Greenopoli carefully tailors both the content and duration of its activities to suit the learners’ age group. Table 1 summarizes how the educational content, methods, and timing are adjusted from kindergarten up to higher education in the Greenopoli framework. Early education focuses on basic concepts (such as separating waste and recycling), conveyed through songs, simple stories, and games in sessions under one hour. As student age increases, additional topics (such as composting, waste treatment, life cycle of products, and the circular economy) are introduced, and methods evolve to include more sophisticated tools (like online quizzes, field trips to recycling plants, and student-led experiments) with longer session times allowed for deeper discussion.

Table 1.

Main aspects of Greenopoli educational activities on waste management, from kindergarten to higher education (each stage builds on the previous, adding more complex content and using age-appropriate methods and duration).

2.2. Kindergarten (Age 3–5)

In the kindergarten stage, the Greenopoli method focuses on the fundamentals of waste separation and recycling, avoiding any complex or abstract content that would be unsuitable for children under five. The educator uses very concrete and engaging techniques: rap songs, storytelling, and simple games are the primary vehicles for learning. A typical 45 min session might open with a friendly hello song or a short “green rap” to capture the children’s attention. Greenopoli raps have proven extremely popular with this age group, as the rhythm and rhymes make the experience feel like play rather than a formal lesson. For example, the educator might perform a lively Recycling Rap with actions (miming collecting a bottle in a bin, etc.), and the children enthusiastically sing along and dance together.

Storytelling is also key for kindergartners. The “Three Little Wolves of Greenopoli” story is often used at the start to introduce the idea that we should not automatically label things (or animals, or materials) as “good” or “bad”. By learning that a wolf can be good, children metaphorically learn that what we call “garbage” might be a useful material if treated correctly (i.e., recycled). This gentle moral is reinforced by Edward De Bono’s principle of teaching children to think creatively and “look at things differently” [16].

Kinesthetic and sensory games typically follow the storytelling. One such activity is a tactile exploration of various recyclable materials. The educator passes around items made of paper, plastic, metal, glass, etc., and encourages children to feel and even listen to the sounds they make when tapped or dropped. Each material has a distinctive sound (for instance, the crinkle of plastic, the ring of metal, the clink of glass). The children then play a game in which they place each item into the correct recycling bin, essentially practicing waste separation through a hands-on exercise. Figure 2a depicts a Greenopoli instructor and kindergarten children singing a green rap together, and Figure 2b shows the children eagerly sorting materials into colored bins as part of the game.

Figure 2.

Two moments of the teaching activities of Greenopoli in Kindergarten: (a) singing the green raps of Greenopoli; (b) showing the recycling materials from the separate collection.

Through these playful methods, even very young learners begin to grasp the idea that different waste materials need different handling. The session concludes with a short discussion (in simple terms) where the children share what they learned (e.g., shouting out which color bin is for paper, which for plastic), and why recycling is important. Although brief, this reflection helps to reinforce the lesson. By engaging multiple senses and allowing children to move, sing, and play, Greenopoli ensures that kindergarteners remain enthusiastic and retain the basic recycling concepts.

2.3. Primary School—First Two Years (Age 6–7)

For first- and second-grade students (approximately 6–7 years old), Greenopoli broadens its content to include topics such as composting and waste reduction, in addition to recycling and waste separation. The format remains highly interactive, incorporating rap songs, storytelling, and educational games, but the sessions are extended to approximately 60 min to align with the children’s longer attention span at this developmental stage.

Early primary students are keen to demonstrate what they know. Greenopoli sessions for this group often begin with a quick activity to gauge and reinforce their knowledge of recycling. For example, as shown in Figure 3a, each student might be handed a small bag of mixed waste items (clean and safe materials) and asked to sort them into the correct bins labeled “paper” (“carta”, in Italian), “plastic” (“plastica” in Italian), “glass” (“vetro”, in Italian), “metal” (“metallo”, in Italian), “organic” (“organico”, in Italian), “residue” (“residuo”, in Italian, i.e., unsorted residual waste), set up within the classroom. This sorting relay game turns learning into a fun competition and engages every child immediately. Greenopoli educators provide color-coded containers and let students physically practice separating a variety of items. During this activity, the educator talks with students about what each material is and why it should be placed in a particular bin, gently correcting any mistakes and praising successes.

Figure 3.

Two moments of the teaching activities of Greenopoli to students in the first two years of primary school: (a) the containers used during the separate collection training activity at school; (b) the Little Environmental Guards of Greenopoli during an educational meeting.

One key concept introduced at this stage is the idea that not everything can (or should) be recycled at home and that some waste will go to energy recovery (i.e., waste-to-energy plants). Greenopoli emphasizes systemic thinking even for young children: students learn that the goal is to maximize waste reduction, reuse, recycling, and composting, but the remaining residual waste is not “bad”: it can be used for energy if handled properly. By teaching that recycling and waste-to-energy are complementary parts of a waste management system, Greenopoli aims to prevent the development of misconceptions or prejudice against certain waste treatments. This nuanced understanding is simplified appropriately (e.g., explaining that unsorted residual waste can be burned in special plants to make electricity), ensuring children grasp that every part of the waste has a place in the cycle.

At this age, Greenopoli also introduces the idea of Greenopoli Little Environmental Guards (LEGs). This is a project where children become “environmental guards” in their homes and communities. Through dedicated Greenopoli raps and class activities, the young students learn four fundamental rules symbolized by four icons: a pedestrian crossing (follow rules and safety), a light bulb (save energy), a recycling bin (reduce, reuse, and then recycle and recover), and a water tap (save water). Under the guidance of their teachers (and with help from parents), the children create circular signs out of recycled cardboard (much like a stop/go paddle) for each of these themes (see Figure 3b). For example, they might draw a big faucet on one cardboard sign to remind everyone to turn off taps. The act of making these signs from waste cardboard itself teaches creative reuse (upcycling). Once the Little Environmental Guards have learned the “rules of the game,” they are encouraged to enforce them at home: reminding parents to recycle according to the local collection calendar, to turn off lights, and so forth. In practice, this transforms children into influencers of adult behavior. This is a clear embodiment of the peer-to-peer and intergenerational learning that Greenopoli champions. Many families report that their children, acting as Greenopoli guards, become diligent “monitors” of household recycling, often correcting the adults if they sort waste incorrectly.

The LEG project has been implemented in several cities in the Campania region of Southern Italy, and its presence can be verified by the numerous social media and local news reports highlighting these child-driven initiatives. By giving children both knowledge and a sense of responsibility, Greenopoli ensures the lessons do not end when the class is over. In fact, they continue at home, potentially leading to measurable improvements in community recycling rates (a desired outcome that some Greenopoli partner municipalities have observed anecdotally).

2.4. Primary School—Last Three Years (Age 8–10)

For students in the later primary grades (approximately 8–10 years old), Greenopoli further enriches the curriculum with the topic of waste disposal (e.g., what happens to non-recyclable waste) and deeper discussion of why recycling matters. By this age, students can handle more information and start to think more critically about processes. Sessions extend to about 90 min, including discussion.

Greenopoli continues to use raps and games but adds more advanced activities like Internet-based quizzes or competitions and field trips. For instance, an online quiz game (such as a Kahoot! quiz or a Greenopoli-developed quiz) might be introduced to test students’ knowledge on recycling facts in a fun, competitive format. Students at this stage are quite tech-savvy and enjoy digital interaction, so Greenopoli leverages that by including multimedia content and possibly showing short videos or even portions of its own TV program episodes (described later) to spark conversation (see Figure 4a).

Figure 4.

Activities involving upper primary school students: (a) a Greenopoli-led lesson in the city of Avellino, broadcast on local television; (b) students participating in the “I, Exemplary Citizen” project organized by Greenopoli in the streets of Salerno.

A standout activity for this group is the “Recycling Relay” or “Treasure Hunt” game: the class is divided into teams that must identify and collect items that can be recycled, or clues related to recycling, around the classroom or schoolyard. This gets them moving and collaborating, and each clue leads to a short educational message. For example, finding a clue might require answering a question about how to dispose of used batteries or the meaning of a recycling symbol. This kind of game builds teamwork and reinforces practical knowledge of waste management in an enjoyable way.

Greenopoli educators also start introducing the concept of the waste hierarchy and the idea of reducing and reusing before recycling. While the term “circular economy” might be introduced in simple language (e.g., “using things in a way that nothing goes to waste”), the main focus is to deepen understanding of why we separate waste and how landfills and incinerators work for what cannot be recycled. At this age, many students are concerned about pollution and are very receptive to understanding the consequences of not managing waste properly.

Field trips become feasible and very impactful in late primary school. Greenopoli often coordinates visits to local recycling plants or eco-centers. Seeing the journey of recyclables first-hand (the piles of paper, the conveyor belts sorting plastics, the composting facilities handling organic waste) leaves a strong impression on students. It also demystifies the waste management process: children realize that recycling is not just an abstract concept, but a real industry where their actions (such as sorting waste at home) have tangible results. Discussions after such trips are often very lively, with students sharing what surprised them (e.g., “I didn’t know aluminum could be melted and used again!”) and voicing commitments (“I will tell my parents never to throw glass in the wrong bin”). These reflections solidify their learning and motivation.

By the end of primary school, Greenopoli aims for students to not only know how to recycle but also why it is important and how it connects to bigger environmental issues. They learn that each of the main recyclable materials (i.e., paper and cardboard, glass, metal, plastic, and wood) has its own recycling story. For instance, a Greenopoli lesson or rap might personify these materials through characters (as done in the Pinocchio-themed rap described later) to make the learning more engaging. Through such creative means, students gain a narrative understanding of recycling (e.g., glass can live forever through endless recycling loops, plastic is useful, but single-use plastic items should be reduced, etc.). This narrative approach is known to boost retention and personal connection to the subject [14].

2.5. Lower Secondary School (Age 11–13)

In middle school (approximately ages 11–13), students are ready to tackle more systemic concepts in sustainability. Greenopoli expands the content to include the life cycle of products and a more explicit discussion of the circular economy principles. Sessions can run for about 2 h (120 min) including participatory discussions.

At this level, the educational approach still leverages music and games, but with greater complexity and student input. Greenopoli workshops for early teens often start by probing their prior knowledge and opinions. Students might be asked questions like, “What do you think happens to your old smartphone when you throw it away?” or “Why do you think it’s important to recycle paper?” These questions spark debate and peer-to-peer learning as students share their ideas. The educator then builds on their responses to introduce concepts like life cycle assessment (in simplified terms: every product has a story from raw material to disposal) and the environmental impacts of products over that life cycle.

Greenopoli uses interactive presentations and team challenges for this age. For example, a class might be divided into small groups, each tasked with mapping out the life cycle of a common item (such as a plastic bottle or a denim jacket), from resource extraction to manufacturing, use, and disposal, and identifying points where the cycle can be made more circular (e.g., refilling the bottle, recycling the fabric). This kind of exercise gets students thinking in systems, which is a crucial skill in sustainability education [15]. Each group can present their life-cycle diagram, effectively teaching each other under the facilitator’s guidance.

Greenopoli also emphasizes critical thinking and media awareness at this stage. Students might analyze recycling campaign posters or short adverts to discuss what messages are being communicated and how effective they are. This ties into communication for a circular economy, understanding not just the technical aspects, but how to influence behavior.

The use of digital tools is becoming increasingly prominent (see Figure 5a). Online competitions or quizzes can be more challenging, perhaps even involving research tasks, for example: “Find out the recycling rate of our city and propose ways to improve it”. Students can use the internet (with guidance) to discover local data, compare with other regions, and present their findings. Such activities nurture research and presentation skills alongside sustainability knowledge.

Figure 5.

Activities carried out using the Greenopoli method in lower secondary schools: (a) an internet-based quiz competition; (b) participation in a green-themed rap performance.

Field trips in lower secondary may include visits to more advanced facilities (like a waste-to-energy plant or a recycling sorting center with modern technology) or even participation in environmental events (e.g., a local clean-up day or a science fair where they present a recycling project). These experiences connect classroom learning with real-world action, which is especially motivating for adolescents who often have a burgeoning desire to “make a difference”.

Importantly, Greenopoli continues to use music to maintain engagement; the educator might present a more sophisticated green rap or even challenge the students to create their own (see Figure 5b). In fact, some Greenopoli sessions for this age have turned the tables: students form teams to write a short rap or poem about a sustainability issue and perform it. This creative exercise not only makes the session fun but also allows the educator to assess students’ understanding based on the content of their lyrics. Peer-led performances often carry peer influence; hearing classmates rap about saving the planet can be more impactful than hearing it from an adult. Such peer-to-peer elements are deliberately cultivated in Greenopoli, reflecting evidence that peer education can be highly effective in motivating behavior change [17].

By the end of lower secondary school activities, Greenopoli expects students to appreciate the interconnectedness of environmental issues. They should grasp that their actions (such as recycling or reducing waste) tie into global challenges and solutions (like resource conservation and climate change mitigation). Surveys and feedback from these students generally show increased environmental awareness and willingness to act, aligning with research that narrative and participatory education boosts environmental attitudes in youth [14].

2.6. Upper Secondary School (Age 14–18)

High school students (approximately 14–18 years old) can delve into advanced aspects of waste management and sustainability, including the technical and regulatory dimensions. Greenopoli sessions for upper secondary students introduce topics such as official definitions (e.g., what legally constitutes waste, hazardous waste, etc.), relevant laws and regulations, and an overview of waste management systems (municipal waste management planning, recycling market, etc.). The content now intersects strongly with economics, civic education, and science, reflecting the multidisciplinary nature of sustainability.

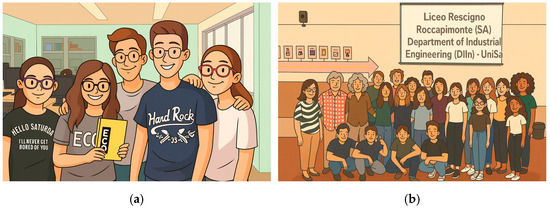

The pedagogical style for teens remains interactive and creative, but with a tone that respects their growing autonomy and critical thinking. Sessions (up to 2.5 h, including discussion) often run as workshops or seminars where students are encouraged to take the lead in certain activities. For instance, a Greenopoli educator might assign a small research project beforehand: students prepare short presentations on specific issues such as “the plastic pollution crisis”, “e-waste and its challenges”, or “the circular economy in fashion”. During the Greenopoli workshop, as shown in Figure 6, these students then share their findings, effectively teaching their peers. The educator facilitates by filling gaps and prompting deeper analysis, but the students are given a platform to act as knowledge contributors. This approach resonates with the sharing principle of Greenopoli: knowledge is a two-way street, and learning happens collaboratively.

Figure 6.

School-work alternation projects implemented using the Greenopoli method in two scientific high schools in the Campania region of Southern Italy: (a) Liceo “V. De Caprariis” in Atripalda (Province of Avellino); (b) Liceo “B. Rescigno” in Roccapiemonte (Province of Salerno).

Role-playing and debate are powerful tools at this level. Greenopoli might set up a mock town hall meeting scenario where students role-play as stakeholders (e.g., a mayor, an environmental NGO representative, a waste company manager, a resident) discussing a proposal to build a new recycling plant or to ban single-use plastics in their town. Each student receives a brief of their role’s perspective and must argue accordingly. This exercise builds empathy (seeing issues from multiple viewpoints) and hones communication skills. It also mirrors real-world environmental decision-making, preparing students as informed citizens. Role-play simulations have been cited as transformative methodologies in environmental education, fostering systems thinking and negotiation skills.

Greenopoli continues to incorporate gamification for high schoolers, but the games are more strategy oriented. For example, a simulation game might assign teams the task of managing a city’s waste with a limited budget. They must decide how much to invest in recycling facilities, landfills, public education, etc., and see the outcomes of their decisions. Such gamified learning has been shown to improve engagement and problem-solving skills in students [18]. Indeed, studies indicate that gamification can significantly enhance learning motivation and knowledge retention by immersing learners in realistic scenarios [18].

Greenopoli’s use of these techniques helps students internalize complex concepts by doing rather than just listening. At this stage, discussions are held at a seminar. Students are capable of debating the pros and cons of waste-to-energy, the effectiveness of recycling vs. reduction, and examining case studies of different countries’ waste management successes or failures. The educator, as moderator, encourages them to reference data and examples (some may come from the Greenopoli content, others from the students’ own research or media). It is not uncommon for a Greenopoli session to spark ongoing projects in the school. For example, students might start their own mini recycling campaign, awareness video, or social media page about sustainability after being inspired by the workshop.

Greenopoli also promotes media creation at this level. Students might be challenged to come up with a slogan or design a poster or short video clip that communicates a recycling message effectively. This not only reinforces their understanding (to communicate well, they must clarify the concept for themselves) but also gives them a product they can share, thus extending the reach of the education beyond the classroom. Some Greenopoli participants have created YouTube videos and school media campaigns following the workshops, effectively becoming peer educators to an even wider circle.

In essence, by the end of upper secondary Greenopoli activities, students should have a well-rounded understanding of waste management and sustainability, spanning scientific, technical, social, and ethical dimensions. They are treated as young adults and partners in learning, which often results in high levels of engagement. Notably, research in Iran has demonstrated that when students receive environmental training from peers (as happens when Greenopoli empowers teens to educate each other), their pro-environment behaviors (like proper waste separation) improve more significantly than if they were only taught by traditional instructors [17]. This evidence reinforces Greenopoli’s core strategy of fostering peer-to-peer education, particularly salient in this age group.

2.7. Higher Education

Greenopoli’s principles have even been applied at the university level (approximately 19 years old and above), although in a more limited capacity and often in the context of teacher training or specific sustainability courses. In higher education settings, the method shifts toward a seminar and project-based approach. The content includes advanced concepts such as detailed life cycle assessment, sustainability metrics, circular economy business models, and waste management policy analysis. Sessions can span three hours or more or be integrated as a module over several classes.

For university students, especially those studying engineering, environmental science, or education, Greenopoli serves as a model of innovative pedagogy and community outreach. When engaging undergraduates (for example, in an environmental engineering course), the Greenopoli method might involve collaborative development of educational materials or research on public awareness. Students could be tasked to design their own Greenopoli-style lesson for a younger audience, or to analyze the impact of Greenopoli in schools via surveys or field observation. This turns the university students into co-creators of the educational process, deepening their meta-cognitive understanding of how people learn about sustainability.

In one instance, Greenopoli was the subject of a Master’s thesis in Communication, where a graduate student analyzed Greenopoli’s approach and even developed a related podcast series titled “The vowels of the revolution: the Greenopoli podcast” [19]. This academic examination of the method in 2022 highlighted Greenopoli’s communication strategy, using appealing narratives (A, E, I, O, U as vowels symbolizing key themes) to attract public interest in environmental topics. It is an example of how Greenopoli not only educates directly but also inspires further educational content creation at the tertiary level.

At the university level, Greenopoli sessions (or guest lectures by the Greenopoli founder, for instance) tend to focus on reflecting on pedagogy and society at large. Discussions might revolve around questions like “Why do people still not recycle even when they know it’s right?” or “How can we measure the impact of environmental education?”. Students, being adults, can criticize and analyze Greenopoli itself, providing feedback, suggesting improvements, and potentially applying techniques in their own future careers as educators or managers.

Field trips remain relevant, and university students may visit integrated waste management facilities or even policy institutions (like a regional environmental agency) to see how decisions and large-scale systems operate (see Figure 7). The Greenopoli philosophy at this stage encourages a bridging of theory and practice: university participants connect academic knowledge with real-world applications and with the challenge of educating others. This aligns with national and international calls for universities to not only teach sustainability in theory but also practice it on campus and in their communities (e.g., via outreach) [3].

Figure 7.

Field trips with higher education students: (a) Mechanical and Biological Treatment (MBT) plant in Battipaglia (Province of Salerno); (b) Waste-to-Energy (WtE) plant in Acerra (Province of Naples).

Finally, the notable outcome of Greenopoli’s university engagement is the opportunity for research and publication on environmental education. After ten years of Greenopoli activities, the founder compiled experiences and tools into a new book (published in 2023) called “Tùttu-cià: Raps, Stories, Explanations and Videos by Mr. Greenopoli on Environment and Surroundings” [20]. This second volume, following the initial theoretical book “Il Metodo Greenopoli” [21], shifts from theory to practice, presenting the accumulated raps, stories, informal explanations, and QR-coded videos developed through Greenopoli’s journey. The innovative format of the book, which can be read in any order and includes interactive multimedia, reflects the Greenopoli ethos. It serves as both a practical handbook and a scholarly reflection on a decade of work. For university students and researchers, this is a rich case study in how creative communication can be systematically applied to achieve educational goals in sustainability.

3. Outreach, Collaborations, and Impact Beyond Schools

Beyond its direct implementation in classrooms, the Greenopoli method has substantially expanded its reach through collaborations with organizations, public institutions, and media, thus amplifying its impact on society at large. This expansion demonstrates how a school-based educational innovation can evolve into a broader environmental communication strategy.

One significant collaboration began in 2017, when the national consortium Comieco (Italy’s official Consortium for Recovery and Recycling of Paper and Cardboard Packaging) adopted the Greenopoli method for its community education programs. Comieco had launched a “Plan for the South” to boost paper and cardboard recycling in underperforming regions. As part of this effort, Greenopoli was enlisted to engage schools and families. A special rap song, the “Unwrap Unwrap Rap” (“Scarta scarta rap” in Italian), was written following Greenopoli’s approach to teach people how to correctly separate paper and cardboard waste. This rap cleverly enumerates common mistakes (e.g., greasy pizza boxes or plastic-coated paper should not go in paper recycling) and reminds listeners in a fun way to remove plastic wrappers and not use plastic bags for paper waste. By communicating recycling guidelines through music, the campaign aimed to reach students and, through them, their families. The Greenopoli team found that this approach significantly improved recall of the rules, children would sing the rap at home, effectively educating their parents. Comieco reported increases in the quantity and quality of paper collected in targeted areas, attributing part of this success to the engaging educational approach. The “Unwrap Unwrap Rap” became a template for developing similar Greenopoli raps for other recyclable materials, demonstrating the scalability of this communication tool.

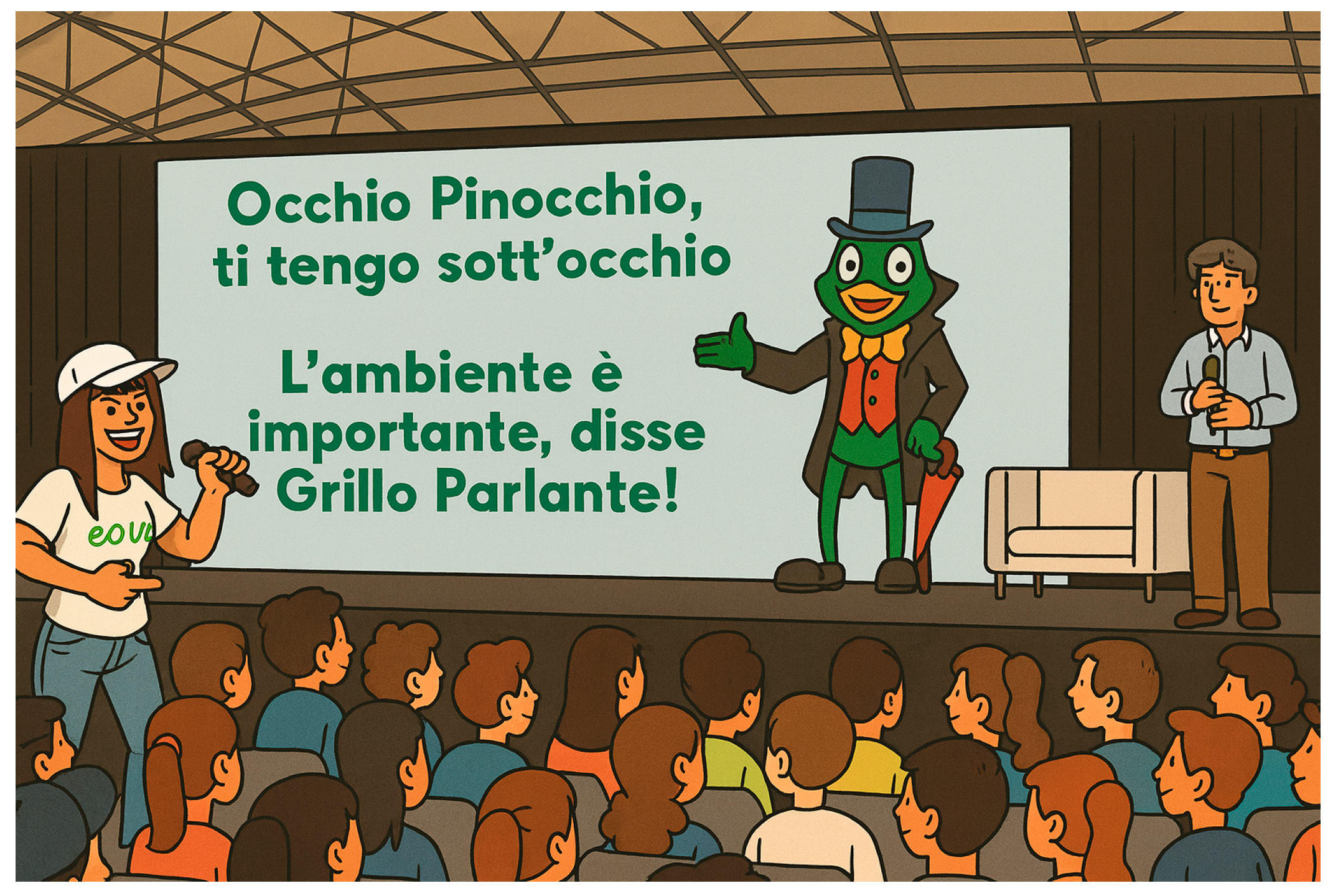

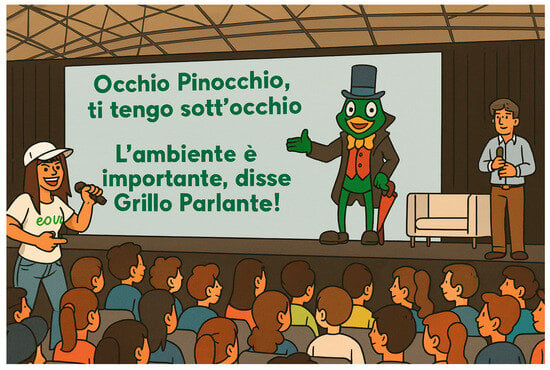

Greenopoli has also been active in national events and media campaigns. In 2018, for instance, the Greenopoli team created “The Green Rap of Pinocchio and the Talking Cricket”, which was showcased at the Sustainability Education Festival in Rome on Earth Day (see Figure 8). This performance artfully merged classic literature with recycling education: characters from the Pinocchio story were used to represent different recyclable materials (wood, paper, aluminum, steel, glass, plastic), each crafted as puppets from recycled materials. The rap and accompanying visuals captivated a broad audience of children and parents at the festival, reinforcing six key recycling streams in an imaginative way. By tying environmental education on cultural references and holidays (like Earth Day), Greenopoli increased its visibility and public appeal.

Figure 8.

Official presentation of “The Green Rap of Pinocchio and the Talking Cricket” during the Sustainability Education Festival on Earth Day 2018, held at Villa Borghese Park in Rome.

In 2019, Greenopoli broke into television. A full Greenopoli lesson conducted at a primary school in Avellino was recorded and broadcast on a regional TV channel. This televised lesson allowed thousands of viewers to witness the dynamic in-class approach (i.e., children singing, playing, and discussing waste management) as if they were participating. The positive reception led to further media projects: Later in 2019, Greenopoli partnered with a waste management company to produce a TV mini-series featuring a popular young YouTuber alongside the Greenopoli educator. Aimed at “digital natives”, this program translated Greenopoli content into an edutainment format suited for teens, blending internet humor with recycling tips. It illustrated Greenopoli’s adaptability to different media platforms and age targets, and it expanded the program’s reach beyond those schools that could be visited in person.

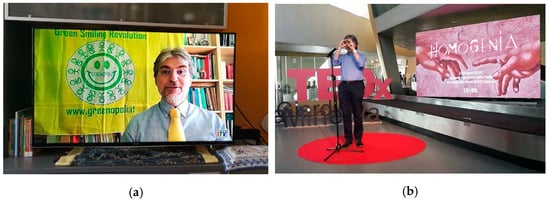

The year 2020 brought further innovation and recognition. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Greenopoli pivoted to create “Ambiente e Dintorni” (“Environment and Surroundings”), a television program consisting of fourteen episodes, which aired on a local TV network and was also made available on Greenopoli’s YouTube channel (Figure 9a).

Figure 9.

Examples of Greenopoli’s outreach and communication activities in 2020: (a) “Ambiente e Dintorni” television program-14 episodes also available on Greenopoli’s YouTube channel; (b) Greenopoli featured in a TEDx Salerno talk, presenting its environmental education method.

This series, essentially an educational show, covered various environmental topics through the Greenopoli lens, featuring raps, interviews, virtual field trips, and explanatory segments. The ability to produce a full-fledged TV program testified to the method’s maturity and the demand for engaging environmental content. Also in 2020, Greenopoli was invited to a TEDx talk stage in Salerno by the founder brought the Greenopoli story and philosophy to a wider intellectual audience (Figure 9b). The talk, focusing on innovative environmental education, further established Greenopoli as a thought-leading initiative in the field.

Greenopoli’s impact has been acknowledged through multiple awards and honors. Notably, the founder and driving force of Greenopoli, Giovanni De Feo, was named “Ambientalista dell’anno” (Environmentalist of the Year) in 2018, a prestigious recognition in Italy awarded by environmental organizations and media. This award lauded the Greenopoli project for its creative approach to grassroots environmental education and its measurable influence on community waste behaviors. Such accolades, along with awards at regional and national levels (including innovation prizes and civic merit awards between 2017 and 2025), have raised Greenopoli’s profile and validated its methodology as a best practice model.

By 2022–2023, Greenopoli transcended national boundaries. The program was invited to deliver environmental education lectures and workshops in Spain and Bangladesh, adapting the approach to different cultural contexts and languages. Additionally, Greenopoli contributed to a European project by co-producing an educational video on recycling and waste separation for schools in Vietnam. These international collaborations indicate that the core principles of Greenopoli, engaging youth with creativity and peer-led learning, have universal appeal and applicability. Although waste management systems and cultural attitudes differ globally, the enthusiasm of young people to learn through fun and share knowledge is a common thread that Greenopoli successfully taps into.

Greenopoli’s multi-platform presence (schools, community events, TV, online, international projects) illustrates how an educational method can evolve into a comprehensive communication strategy for a circular economy. By bridging formal education and public outreach, Greenopoli has created a feedback loop: the experiences in classrooms inform the content produced for media and vice versa. The expansion has also allowed for informal evaluation of effectiveness; for instance, television and online content reach parents and the general public, some of whom provide feedback or engage in challenges initiated on the shows (like home recycling challenges). While a rigorous scientific evaluation of Greenopoli’s long-term impact is yet to be published, the growing interest and replication of its techniques by others suggest it is making a meaningful difference.

In summary, over a decade, Greenopoli grew from a local school program into an influential movement in environmental education and communication. It achieved this by maintaining fidelity to its core method (interactive, fun, peer-involving) while flexibly collaborating with institutions and media to amplify its reach. Such a trajectory underscores the potential for school-based sustainability initiatives to catalyze wider societal change, an aspect we further discuss by comparing Greenopoli with other models in the next section.

4. Discussion

Greenopoli’s approach exemplifies several key trends in modern environmental education and offers some innovative twists that distinguish it from other established models in Europe and globally. In this section, we compare Greenopoli with other educational frameworks and communication strategies, highlighting both common principles and unique contributions.

4.1. Active, Learner-Centered Pedagogy

Across the board, contemporary environmental education emphasizes moving away from rote instruction toward active, student-centered learning. In this respect, Greenopoli shares philosophical ground with programs like Eco-Schools, Young Reporters for the Environment (YRE), and various UNESCO ESD initiatives. For example, the Eco-Schools program (coordinated by the Foundation for Environmental Education) engages students in forming committees, auditing their school’s environmental performance, and taking action on issues including waste [3].

Building on the learner-centered and participatory principles discussed earlier, both Greenopoli and Eco-Schools position students as active protagonists in the learning process rather than passive recipients. However, there are differences in execution. Eco-Schools typically operate as a whole-school framework led internally by teachers over a long term, culminating in awards (like the Green Flag) for schools that meet targets [3]. Greenopoli, by contrast, often functions as an external catalyst, namely a specialized intervention (be it a one-day workshop or a short series of sessions) delivered by an expert educator who brings a fresh, extra-curricular perspective. This external moderation allows Greenopoli to sometimes bypass curricular constraints that teachers face (such as lack of time or pressure to cover core subjects) [3]. Indeed, many teachers cite limited time and resources as barriers to covering sustainability topics [3] and Greenopoli’s visits can supplement the regular curriculum with rich content and activities that might otherwise not occur. In essence, Greenopoli complements existing structures like Eco-Schools by providing a burst of creativity and specialist knowledge, potentially invigorating a school’s ongoing sustainability efforts. Beyond shared learner-centered principles, Greenopoli differs from these models in its systematic use of narrative devices, performative tools (e.g., music and raps), and short, high-intensity educational interventions, which are rarely formalized within curriculum-based frameworks such as Eco-Schools or UNESCO ESD initiatives [3].

While the present contribution is intentionally framed as a descriptive and reflective best-practice study, the Greenopoli method has also been the subject of structured quantitative evaluations in previous academic research. In particular, two master’s theses developed at the University of Salerno applied pre- and post-intervention questionnaire designs, combined with statistical analyses, to assess learning outcomes associated with Greenopoli-based educational activities.

Iannone (2021) documented statistically significant improvements in students’ knowledge and awareness of environmental and waste-related issues by comparing innovative, emotion-centered communication approaches with more traditional instructional methods [22]. More recently, Napoli (2025) conducted a quantitative assessment of students’ knowledge, behaviors, and perceptions related to sustainability topics following Greenopoli-inspired educational interventions, confirming measurable learning gains across multiple dimensions [23].

Although these studies do not allow for a strict causal attribution of observed learning outcomes to individual pedagogical tools, both works consistently associate students’ gains in environmental knowledge, vocabulary acquisition, critical awareness, perceived responsibility, and willingness to engage in sustainable actions with the experiential and emotionally engaging nature of the educational activities. In particular, qualitative observations and student feedback reported in these studies highlight the role of narrative elements, music, and performative practices in supporting memorization, engagement, and meaning-making processes when compared with more traditional, lecture-based instructional approaches. These findings suggest that the creative and narrative components of Greenopoli function as enabling mechanisms within a broader, integrated educational design, rather than as isolated didactic techniques.

Although these studies do not aim at broad statistical generalization, their results provide quantitative support to the qualitative observations and long-term experiential insights discussed in this paper, reinforcing the educational effectiveness of the Greenopoli approach within real-world school contexts. These theses were developed directly within a Greenopoli-inspired university teaching and research framework, in which students actively participated in the design, implementation, and evaluation of educational interventions, thereby linking academic research, pedagogical analysis, and community-based practice.

Beyond academic outputs, the involvement of higher education students in the Greenopoli framework has generated practical outcomes, including the development of educational materials, school and community outreach activities, and, in some cases, the professional engagement of graduates as environmental educators applying the Greenopoli method in real-world contexts.

To further clarify the distinctive features of Greenopoli in relation to other established educational models, Table 2 provides a comparative analytical overview of selected approaches to sustainability education.

Table 2.

Comparative overview of selected educational models for sustainability and recycling.

4.2. Peer-to-Peer and Intergenerational Learning

A standout feature of Greenopoli is its deliberate promotion of peer learning and the idea that children can educate others (including adults). While student leadership is encouraged in various models (e.g., YRE involves students in producing journalistic pieces to inform their community), Greenopoli’s methodology, especially with the Little Environmental Guards and engaging children as teachers to their parents, is particularly direct in leveraging this effect.

Research supports Greenopoli’s premises. For example, a 2025 study in Iran found that environmental training delivered by peers led to significantly better waste separation behaviors among schoolchildren than training delivered by adult instructors [17]. Greenopoli builds such peer education organically into its sessions (students teaching each other through games, older students mentoring younger ones in some events, etc.) and its projects (kids reminding parents, as in the LEGs program). This approach not only reinforces the students’ own learning (the “learning by teaching” effect) but multiplies impact beyond the classroom.

Many environmental education programs aspire to this multiplier effect, but Greenopoli’s use of child-friendly media (rap songs, colorful signs, etc.) provides concrete tools that children naturally share outside school. In European waste education contexts, intergenerational influence is often an incidental benefit; in Greenopoli, it is a core strategy. The result is a bridging of gaps—between school and home, and between generations—a crucial aspect for true societal shifts toward sustainability [3].

4.3. Gamification and Engagement

Greenopoli’s extensive use of games, challenges, and competitions aligns with the global trend of gamifying sustainability education. Programs worldwide are increasingly employing game-based learning to boost engagement, from mobile apps that reward recycling actions to classroom board games on conservation. Meta-analyses indicate that gamification can improve learning outcomes, motivation, and participation in educational settings [18].

What Greenopoli adds is a thematic coherence: the games are not stand-alone but part of a narrative (be it becoming an “environmental guard” or solving the mystery of the waste cycle). In this way, Greenopoli combines gamification with storytelling, which amplifies its impact. An educational board game used in a sustainability context (for instance, the “Zöld járőr” or “Green Patrol” game in a recent Hungarian study) was found to significantly consolidate students’ environmental knowledge and pro-environment attitudes [24].

Greenopoli’s activities, such as the recycling relay or waste management simulation, serve a similar purpose since they turn abstract concepts into tangible challenges to be mastered. Compared to some traditional environmental educational activities that might rely on didactic methods or purely informational content (posters, lectures), Greenopoli’s gamified approach ensures a higher level of student attention and emotional involvement. This is particularly important for topics like waste management that can otherwise seem mundane or routine; games inject a sense of fun and urgency.

4.4. Creative Communication (Storytelling, Music, and Arts)

A highly distinctive aspect of Greenopoli is its embrace of creative communication channels as educational tools, especially music (rap) and storytelling. While many environmental programs include arts (for instance, students might do poster contests or eco-dramas), Greenopoli has made them central. The Greenopoli “green raps” are not common in most curricula; however, they resonate with initiatives like the “Eco Hip-Hop” movement in the United States, where educators and artists use hip-hop music to address environmental justice and climate change issues [13]. Cermak (2012) demonstrated that having students write and perform green hip-hop songs in a science class led to heightened engagement and allowed students to internalize ecological concepts in their own cultural voice [15].

Greenopoli anticipated and exemplified this approach in Italy, a context where rap might not have been an obvious educational medium. By doing so, it validated that music transcends language and cultural barriers in education. Italian children and teens responded to green rap similarly to how youth elsewhere might respond to eco-themed pop culture. Furthermore, Greenopoli’s storytelling (like the Green Little Wolves tale or the Pinocchio recycling fable) leverages characters and narratives to impart moral and practical lessons. Storytelling has long been a powerful means in indigenous and non-formal environmental education to convey values and connect learners emotionally to content [25].

Recent studies confirm that narrative-based environmental education can effectively enhance students’ environmental awareness and attitudes [14]. Greenopoli’s innovation lies in packaging these stories in a modern, playful way (overturning a familiar fairy tale, for instance) to capture imagination. Compared to standard curricula, which might seldom use fantasy or music to teach about recycling, Greenopoli’s method stands out as edutainment, educating through entertainment. This approach aligns with calls for more imaginative pedagogy in sustainability education to inspire hope and creativity rather than eco-anxiety or boredom [26].

4.5. Adaptability Across Ages and Contexts

Greenopoli’s structured differentiation by age group (Table 1) shows a level of detail in pedagogical design that not all programs articulate. Many environmental education initiatives focus on a particular age bracket or have a one-size-fits-all toolkit. Greenopoli, on the other hand, evolved a continuum from ages 3 to 23+, ensuring that messaging and methods grow with the learner. This is somewhat akin to formal education standards (like how math or science curricula scaffold content by grade), but in the realm of informal or non-formal environmental education, it is an innovative comprehensive framework.

The adaptability was evident when Greenopoli was applied internationally, a testament that its core methods (music, games, participation) are adaptable beyond the Italian context. For example, when Greenopoli-style lessons were conducted in Bangladesh and Spain, the educators could transplant the interactive techniques and simply adjust the language and examples. This flexibility suggests Greenopoli’s model could be replicated or integrated into other programs globally, serving as a module for engagement within larger schemes. It could, for instance, be woven into UNESCO’s Trash Hack campaign: schools could use Greenopoli raps or games as their “Trash Hack” action, fulfilling the campaign’s call for creative, student-driven waste reduction activities [10].

4.6. Emphasis on Measurable Outcomes and Real-World Impact

Many traditional environmental education efforts have been criticized for focusing only on knowledge gain without translating into action. Greenopoli consciously aims for tangible behavior change, like improving recycling rates or specific correct practices (e.g., no plastic bags in paper bins). By collaborating with entities like Comieco and municipalities, Greenopoli ties its success to real-world metrics (tons of paper recycled, contamination rates in recycling, etc.). This practical orientation is aligned with the communication aspect of circular economy promotion, where the ultimate goal is to change societal behavior, not just awareness. European waste directives and national waste prevention programs increasingly highlight education and awareness as key to meeting recycling targets [3].

Greenopoli’s experience provides a case study of how to do this on the ground. For instance, its method contributed to the recovery of part of the 700,000 tons of paper that was previously going to residual waste in southern Italy by educating citizens through their children. The discussion around Greenopoli, therefore, serves to illustrate how educational models can directly support policy goals (such as the EU’s 55% recycling target by 2025) [3].

Compared to some global programs that might operate at a more general level (e.g., promoting sustainability broadly without focusing on a specific waste stream), Greenopoli offers a more focused “waste literacy” approach with direct ties to local waste management outcomes.

4.7. Challenges and Areas for Improvement

While Greenopoli represents a creative and engaging model of environmental education, particularly effective in capturing learners’ interest, it is also important to examine its challenges and areas where further development is needed, especially when considering its broader application in formal education systems.

A first area of reflection is scalability. The Greenopoli method is highly interactive, energetic, and based on direct contact with learners. Its success to date has relied heavily on the personal charisma, communication skills, and enthusiasm of its founder, the so-called “Mr. Greenopoli”. Although the program offers a rich collection of materials, songs, and games that are freely available, replicating the same level of engagement in other contexts would require training educators not only in the tools but also in the pedagogical philosophy that underpins the method. As noted by Iannone (2021) [22] and Napoli (2025) [23], educators involved in Greenopoli initiatives express strong appreciation for the approach and also highlight the need for teacher training to ensure continuity and institutional anchoring of the method across schools. In this regard, the Greenopoli method has already begun to generate forms of internal replication through former students who have progressively assumed the role of environmental educators. Some of these practitioners combine scientific training with artistic and communicative skills, contributing to the transmission of the method beyond its original founder. For example, Iannone, who holds a degree in environmental sciences and is also an active singer and musician, currently applies the Greenopoli approach in educational and outreach activities, demonstrating how the method can be embodied and reinterpreted by new educators while preserving its core principles.

Compared to other models like Eco-Schools, which structurally empower teachers and student committees within each school, Greenopoli would benefit from a hybridization strategy, training teachers to become autonomous facilitators of the method. This could enhance its durability, embed it more deeply into school curricula, and allow the program to grow beyond the direct presence of its creator.

Another frequently cited challenge in environmental education is the evaluation of impact. In this regard, Greenopoli offers encouraging findings. While many communication-based initiatives rely on anecdotal feedback, both Iannone (2021) and Napoli (2025) carried out quantitative pre- and post-intervention studies that document the educational effectiveness of the method [22,23].

Iannone (2021) applied the Greenopoli approach in a lower secondary school setting, comparing baseline and final data collected via structured questionnaires [22]. The results demonstrated statistically significant increases in students’ environmental knowledge, vocabulary acquisition, and critical awareness of waste-related behaviors. Napoli (2025) focused on both cognitive and attitudinal outcomes [23]. His findings confirmed improvements not only in environmental knowledge but also in students’ perceived responsibility and willingness to engage in sustainable actions, thus validating the method’s ability to foster civic participation alongside conceptual learning [23].

These data position Greenopoli as an evidence-informed methodology and respond directly to academic calls for more empirical evaluation of environmental education programs. They also align with findings from recent peer-reviewed literature. For instance, Yang et al. (2022) showed that narrative-based and gamified environmental education significantly improved environmental awareness and attitudes in young learners aged 6–8, reinforcing the educational potential of approaches that combine storytelling, creativity, and experiential engagement [14].

Greenopoli aligns strongly with contemporary paradigms that promote learner-centered, participatory, and creative education for sustainability. What sets it apart is the integration of multiple communication tools, such as rap, theatrical storytelling, playful challenges, and community outreach, that together form a flexible and emotionally engaging toolkit. Furthermore, Greenopoli doubles as both a pedagogical method and a public awareness campaign, making it a hybrid model with the potential to affect change both in classrooms and in society at large.

As societies strive toward circular economy goals and climate resilience, models like Greenopoli that educate, entertain, and inspire action offer not only educational value but cultural relevance. Its core message is simple yet powerful: when learners laugh, sing, and play while learning, they internalize the message, retain it longer, and are more likely to live it out in their communities.

A key issue related to the broader adoption of the Greenopoli approach concerns its scalability and replicability across different educational and territorial contexts. While Greenopoli originated as a highly personalized, experience-based educational practice, its core components are inherently modular and transferable. These include a structured narrative framework, clearly defined thematic modules (e.g., waste separation, recycling, circular economy), gamified activities, and creative communication tools such as songs, raps, and storytelling.

Replication does not require strict standardization, but rather the availability of flexible training pathways for educators and communicators. In practice, scalability can be supported through the development of trainer-oriented materials, such as methodological guidelines, adaptable lesson plans, activity toolkits, and communication templates, which can be tailored to local needs and age groups. Experiences already conducted in collaboration with schools, municipalities, recycling consortia, and cultural organizations suggest that the Greenopoli approach can be effectively transferred when its underlying principles are preserved, even if specific contents and formats are locally adapted.

When implemented outside its original Italian and European context, the Greenopoli approach has required targeted contextual adaptations while maintaining its core pedagogical principles. In Asian educational settings, for example, adaptations mainly concerned language, cultural references, and alignment with local waste management systems and regulatory frameworks. Narrative elements, games, and musical activities were reformulated using locally meaningful symbols and examples, while preserving the emphasis on active participation, emotional engagement, and peer learning. Collaboration with local educators and institutions proved essential to ensure consistency with national curricula and culturally appropriate communication styles. These experiences indicate that Greenopoli’s international transferability depends on preserving its educational logic rather than replicating identical activities.

5. Conclusions

This paper has presented the Greenopoli method as a comprehensive and engaging framework for environmental education, with a particular focus on sustainable waste management. Through its use of storytelling, music, gamification, and moderated peer learning, Greenopoli makes sustainability concepts accessible and appealing to learners from the earliest ages through adulthood. The framework’s flexibility in adapting content and pedagogical techniques to different educational stages, from kindergarten sing-alongs about recycling to high school debates on waste policy, demonstrates a model of vertical integration in education for sustainable development. Greenopoli effectively bridges the gap between theory and practice, embodying the often-cited principle that education is the most powerful tool for achieving a sustainable future.

Several unique contributions of Greenopoli were highlighted in comparison to other environmental education initiatives. Greenopoli’s creative communication methods, especially the innovative use of “green raps” and interactive storytelling, set it apart as a pioneer in blending popular culture with sustainability learning. These methods have proven to not only captivate student interest but also to enhance retention of knowledge and to stimulate students’ own creativity in expressing environmental messages. Moreover, Greenopoli places a strong emphasis on peer-to-peer influence and intergenerational learning, leveraging children’s enthusiasm to act as catalysts for change within their families and communities. This approach aligns with recent research showing that peer-led education can outperform traditional instruction in fostering pro-environmental behaviors [17]. It also directly supports the goals of a circular economy by translating knowledge into action, as evidenced by partnerships where Greenopoli’s educational campaigns have led to measurable improvements in recycling practices.

Greenopoli’s evolution beyond the classroom into media and international collaborations illustrates the scalability and transferability of its core principles. By collaborating with consortia, appearing on television, and contributing to global projects, Greenopoli has shown that a school-based project can expand into a broad communication strategy for sustainability. This aligns with the objectives of initiatives like UNESCO’s ESD for 2030, which call for innovative educational approaches that engage all of society in learning about and implementing sustainability. The positive reception of Greenopoli’s methods in different cultural contexts (Europe and Asia) suggests that its approach taps into universal aspects of learning (i.e., curiosity, play, and the joy of shared experiences), which can be powerful across diverse settings.

For educators, policymakers, and organizations aiming to promote recycling education and circular economy awareness, the Greenopoli case offers several lessons. First, multi-sensory and playful learning experiences can significantly enhance student engagement in topics that might otherwise seem technical or mundane. Second, empowering students as educators (whether informally at home or formally through projects) creates a ripple effect that multiplies impact and fosters youth leadership. Third, integrating educational efforts with community and media outreach can reinforce messages and sustain momentum. In fact, a student who learns about recycling in class and then sees a related message on TV or online is more likely to internalize and act on it. This integrated approach is something that could be emulated in other regions: for instance, local governments might adopt Greenopoli-style programs to complement infrastructure improvements, ensuring that citizens are educated and motivated to use new recycling systems effectively [3].